1. Introduction

Gearboxes stand as core components in critical industrial systems spanning diverse sectors, including automotive drivetrains, marine propulsion systems, and wind turbines. Their high-precision operation and the ability to maintain a prolonged service life are not merely desirable but essential for upholding system reliability and efficiency. In the realm of industrial production, gearbox fault diagnosis technology assumes a pivotal role. It serves as a safeguard against unexpected downtime, which can lead to substantial financial losses and disruptions in production schedules. Moreover, it plays a key part in optimizing maintenance strategies, enabling a shift from costly and inefficient reactive maintenance to more proactive and cost-effective predictive and preventive approaches [

1].

The development of sensor technology and the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) has significantly increased the availability of operational data, promoting the adoption of data-driven fault diagnosis methods. However, several challenges remain. Vibration signals from gearboxes are typically non-stationary, with time-varying frequency components. Noise interference often masks fault-related features. Additionally, deep learning models, while effective, often lack interpretability, which limits their adoption in safety-critical industrial applications [

2]. Few-shot learning scenarios, where fault samples are scarce, further complicate model training and generalization.

Current research in machinery fault diagnosis can be broadly categorized into signal processing-based methods and deep learning-based approaches. Domestic studies have focused on optimizing traditional signal processing techniques or designing new deep learning architectures. For example, Yuan et al. (2025) proposed an improved multi-scale CNN with lightweight attention mechanisms for gearbox fault diagnosis [

3]. Despite these efforts, there is still a lack of models that simultaneously achieve high accuracy and strong interpretability. Recent studies suggest that incorporating physical insights into neural network design can enhance model transparency and diagnostic performance [

4]. Similarly, Zhou et al. proposed a global optimization GAN framework that generates discriminative fault features rather than raw data, enabling robust fault diagnosis under an extreme data imbalance while maintaining diagnostic relevance [

5]. In the domain of multi-sensory vibro-acoustic fusion, Yan et al. proposed a novel coarse-to-fine dual-scale time-frequency attention fusion network (CDTFAFN) which bridges this gap by integrating physics-informed time-frequency transforms with data-driven learning through a unique two-stage fusion strategy, achieving high diagnostic accuracy and robustness in noisy environments [

6]. Our proposed TFDT model bridges this gap by integrating physics-informed time-frequency transforms with data-driven learning.

Conventional signal processing methods, such as wavelet transforms and empirical mode decomposition, aim to extract fault-related features from raw vibration signals. Xu et al. [

7] applied machine learning algorithms to automatically recognize fault patterns from extracted features. Xiang et al. [

8] proposed a hierarchical fuzzy Petri-net framework that integrates reversible and dynamic decomposition to enable parallel fault-diagnosis reasoning and preserve multi-level fault-feature integrity. Zhang et al. [

9] redesigned the convolutional neural network architecture with enhanced receptive-field mapping and lightweight attention modules to boost the accuracy of bearing-fault classification from raw vibration data. While these methods have improved diagnostic performance, issues such as model interpretability and generalization to unseen fault types remain unresolved.

Internationally, researchers have emphasized model interpretability by using gradient-based visualization techniques to understand feature importance. However, challenges such as diagnosing under strong noise and learning from small datasets persist. Vashishtha et al. [

10] conducted a bibliometric analysis to outline future directions in fault diagnosis. Chaleshtori et al. [

11] combined Gaussian mixture models with weighted PCA for noise-robust diagnosis. Hussain et al. [

12] employed ensemble learning with error correction to enhance diagnostic robustness. Despite these advances, a general-purpose model that is accurate, interpretable, and robust remains elusive.

To address these multifaceted gaps in the current state of the art, we propose a novel TFDT model. This model integrates TFConv layer into a conventional CNN, embedding a physics-informed TFT mechanism. Specifically, the TFConv layer is designed to adaptively extract time-frequency features strongly correlated with fault signatures, thereby enhancing both diagnostic accuracy and model interpretability. The STTF convolution kernel uses an adaptive window width with the frequency parameter f constrained to to comply with the Nyquist theorem. The Chirplet convolution kernel introduces the frequency modulation parameter and initial frequency , optimized through training to capture time-varying frequency features. The Morlet convolution kernel introduces the scale parameter s and center frequency , which are optimized through training to capture transient features. These innovations enable the TFConv layer to adaptively extract fault-related features, improving diagnostic accuracy and interpretability. The TFDT model aims to enhance diagnostic accuracy, model interpretability, and robustness against noisy and non-stationary signals, laying a solid foundation for high-reliability intelligent diagnostic systems in industrial machinery. Such systems can transform the maintenance and management of critical gearbox-based industrial systems, ensuring continued operation with minimal disruptions and maximum efficiency. Additionally, integrating edge computing capabilities can enable real-time data processing and diagnosis at the source of data generation, reducing latency and the need for extensive data transmission. Exploring transfer learning can help adapt the model to different gearbox types or operating conditions with minimal retraining, while integrating uncertainty quantification can provide a diagnostic result along with an estimate of the confidence in that result, which are valuable for industrial decision-making processes.

This paper proposes a learnable time-frequency layer that fuses physics-based transforms with CNNs into one end-to-end network, delivering higher accuracy, faster convergence, and robustness to noise while retaining clear physical meaning and easy transfer across machines.

2. Background

This section provides an overview of the foundational concepts and literature that underpin the development and application of the TFDT model. It outlines the structure of the chapter and introduces the key topics to be explored, including the theoretical background, related work, and the motivations behind the proposed model. This setup aims to give readers a clear roadmap of the chapter’s content and the significance of the TFDT model in the context of mechanical fault diagnosis.

Mechanical fault diagnosis is pivotal for the reliability and efficiency of industrial machinery. The transition from reactive to predictive maintenance underscores the critical need for advanced diagnostic technologies capable of handling the complexities of modern vibration signals.

Despite the proliferation of data from the IIoT, significant challenges persist. Vibration signals are inherently non-stationary and often corrupted by noise, complicating the extraction of reliable fault features. Furthermore, while deep learning models offer powerful feature learning capabilities, their “black-box” nature limits interpretability, which is a critical requirement for safety-critical applications, and they often demand large, labeled datasets that are scarce for rare or emerging faults.

Consequently, the research community has explored two primary paradigms. Traditional signal processing methods, such as wavelet transforms, depend on manual parameter tuning and expert knowledge, which hinders automation and scalability. In contrast, end-to-end deep learning models eliminate hand-crafted features but suffer from a lack of physical transparency and poor generalization under variable operating conditions. Hybrid approaches that combine fixed time-frequency transforms with CNNs improve interpretability but introduce a rigid preprocessing step and cannot adapt to dynamic machinery states.

These multifaceted limitations highlight a clear gap in the literature: the need for a model that is not only accurate and robust but also interpretable, data-efficient, and adaptable to real-world industrial environments. Our proposed TFDT framework is designed specifically to address this gap by embedding physics-informed time-frequency analysis directly into the deep learning process.

3. Time-Frequency Dual Transformation Network

This section will provide a detailed introduction to the mechanical fault diagnosis model we propose, the TFDT. This model aims to improve diagnostic accuracy and model interpretability by integrating physics-informed time-frequency transformations with deep learning. We will successively introduce the network architecture design of the TFDT, the implementation details of the TFConv layer, and the training and optimization strategies of the model. Through these contents, readers can gain a comprehensive understanding of the design philosophy and implementation methods of the TFDT model.

3.1. Network Architecture Design

To address the limitations of traditional TFT methods and the interpretability challenges of CNNs, we propose the TFDT. The TFDT integrates a TFConv layer into a conventional CNN [

17], embedding a physics-informed TFT mechanism [

18]. This design enables TFDT to achieve dual objectives: physics-driven feature extraction through parameterized time-frequency kernels aligned with mechanical fault characteristics, and adaptive learning of fault signatures via end-to-end training. The modular structure of TFConv ensures compatibility with various deep network backbones (e.g., ResNet, DenseNet), making it suitable for flexible integration into diverse industrial diagnostic systems. By bridging theoretical fault physics with data-driven learning, experiments validate that TFDT achieves a significant accuracy improvement over traditional “TFT + CNN” pipelines in 64-channel configurations.

In the TFDT model, the TFConv layer is integrated as the first convolutional layer of the CNN. This integration ensures that the model can extract time-frequency features related to fault signatures in the early stages of feature learning, providing richer information for subsequent feature extraction and classification tasks. The TFConv layer is based on physics-informed TFT and is designed to adaptively extract time-frequency features strongly correlated with fault signatures. For example, the STTF convolution kernel uses a Gaussian window to balance time and frequency resolution, the Chirplet convolution kernel captures time-varying frequency features through the frequency modulation parameter , and the Morlet convolution kernel captures transient features through the scale parameter s and center frequency . The input signal first passes through the TFConv layer for time-frequency feature extraction, and the extracted features are then passed to the subsequent CNN layers, which further process these features and complete the classification task. During training, the parameters of the TFConv layer are updated via backpropagation to adapt to the fault features in the dataset, thereby improving the model’s diagnostic accuracy and generalization ability.

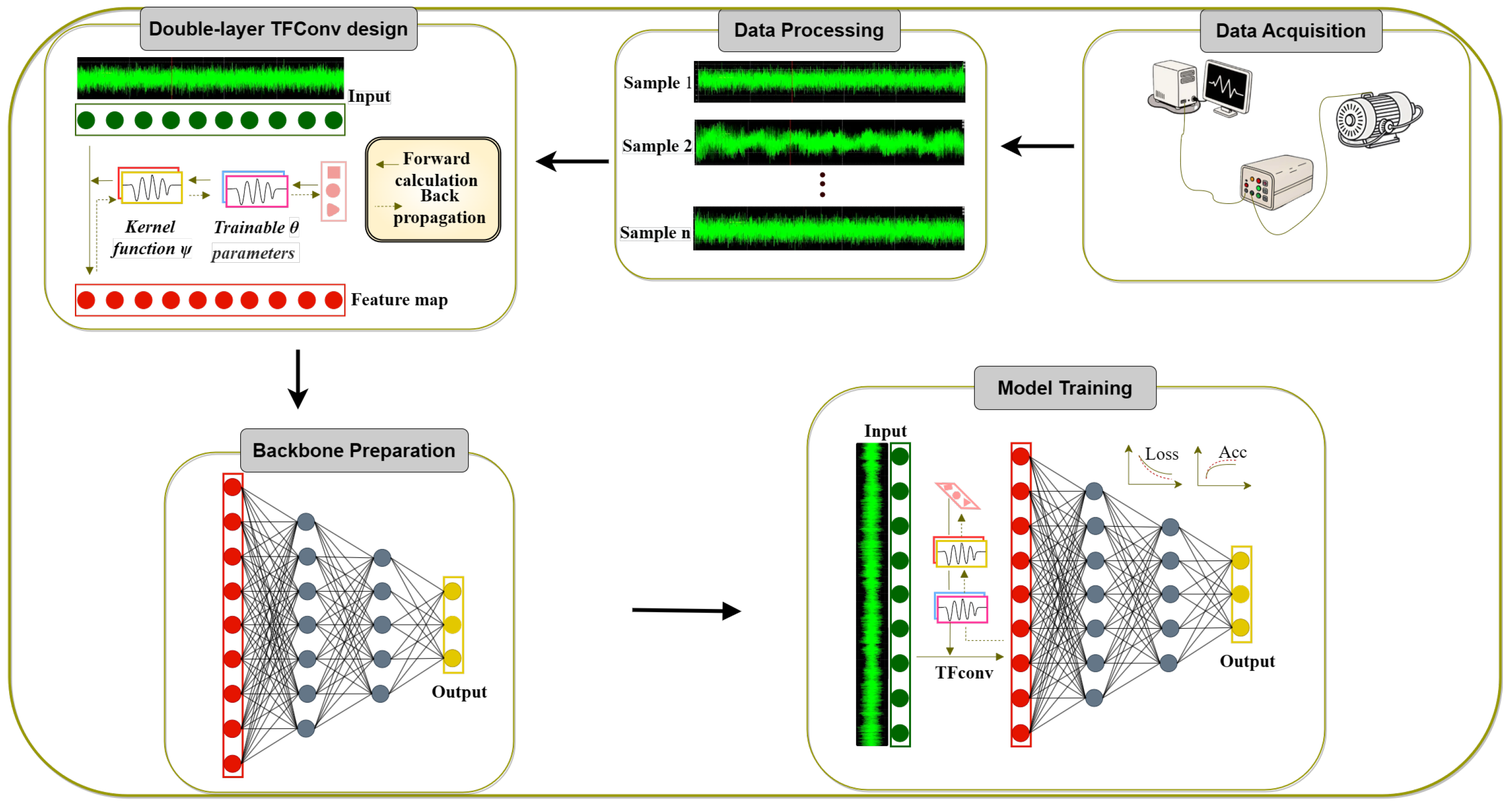

The architecture of the TFDT model is illustrated in

Figure 1, which highlights the integration of the TFConv layer with a CNN backbone. This design combines the interpretability of TFT with the adaptive learning capability of deep networks, as evidenced by the trainable kernel functions that simulate physical transforms (e.g., STTF [

19], Morlet wavelet [

20]).

The core innovation of TFConv lies in parameterizing the inner-product operation of traditional TFTs into a learnable convolution kernel while introducing physical constraints to ensure model interpretability. For a sampled discrete signal

, the output of the TFConv layer is calculated as follows:

Here, is a parameterized complex-valued convolution kernel defined by a physical basis function and a learnable modulation parameter . The kernel length M determines the size of the local receptive field, and is the bias term that adjusts the output offset. This formulation enables the model to adaptively extract the time-frequency features most relevant to fault signatures, as confirmed by ablation experiments showing a 9.5% accuracy drop when TFConv is removed. Different TFT methods exhibit distinct basis function designs:

Short-Time Fourier Transform (STTF): The STTF basis function employs a Gaussian window to balance time-frequency resolution, making it suitable for stationary fault signals.

where

controls the Gaussian window width and

f is the normalized frequency constrained to

in accordance with the Nyquist theorem. After training, the frequency parameter

f typically concentrates around fault feature frequencies, such as gear meshing frequencies and their harmonics. The output of the first TFConv layer using STTF captures stable frequency bands, making it effective for diagnosing faults with consistent frequency characteristics.

Wavelet Transform (Morlet): The Morlet wavelet is optimized for transient feature extraction, making it effective for impact-type faults (e.g., gear tooth breakage).

where

s is the scale parameter,

, and

adjusts the localization of the central frequency. After training, the scale parameter

s and center frequency

adapt to capture transient fault features, such as gear tooth breakage. The output of the first TFConv layer using Morlet wavelet captures transient features, making it effective for diagnosing faults with sudden changes or impacts.

Chirplet Transform: The Chirplet transform captures time-varying resonances in variable-speed machinery via a frequency modulation (FM) factor

.

where

is the initial frequency (e.g., bearing characteristic frequencies BPFO/BPFI),

is the FM factor, and

. After training, the frequency modulation parameter

adapts to capture time-varying frequency features, such as those in variable-speed gearboxes. The output of the first TFConv layer using Chirplet transform captures time-varying frequency features, making it effective for diagnosing faults with changing frequency characteristics over time.

3.2. Three Dual-TFConv Layer Model Architectures

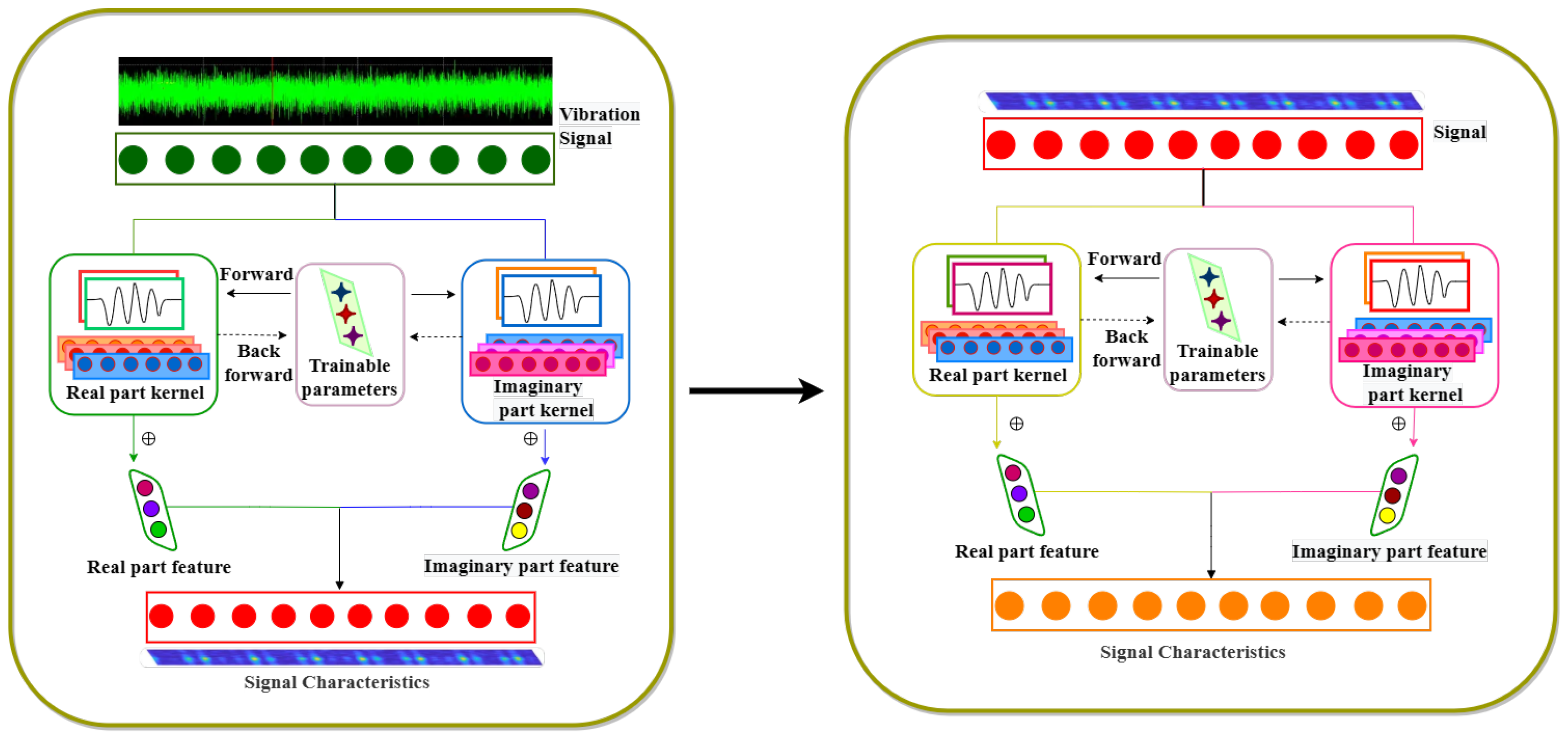

To intuitively illustrate the core mechanism of the TFConv layer,

Figure 2 visualizes the interaction between real/imaginary kernels, trainable parameters, and the process of extracting time-frequency signal characteristics.

Based on the TFConv layer design, three specialized dual-layer models are proposed to address distinct fault diagnosis scenarios.

1. STTF-based time-frequency feature enhancement model

Intended for constant-speed gearboxes, the STTF variant uses two TFConv layers. Layer-1: , output . Layer-2: identical basis, followed by frequency-emphasis convolution and global average pooling that yields a weight vector which peaks at meshing sidebands . The pipeline isolates stationary spectral lines without manual band selection.

2. Morlet Wavelet-Driven Transient Fault Model

Optimized for impact-type faults (e.g., gear tooth breakage), this model employs Morlet wavelets for transient feature extraction. The first TFConv layer uses Morlet basis functions with and to capture time-domain shocks, producing an output of shape —a structure well-suited to representing transient fault signatures. The second TFConv layer dynamically adjusts the time window parameter during training via backpropagation, enhancing sensitivity to transient events. This adaptive windowing mechanism improves the model’s capability to localize impact-type faults in noisy signals.

3. Chirplet-Driven Resonance Frequency Model

Targeting time-varying frequency signals in variable-speed gearboxes, this model utilizes Chirplet transforms [

21] to capture resonance features. The first TFConv layer initializes Chirplet kernels with

set to bearing characteristic frequencies (BPFO/BPFI), aligning with theoretical fault physics, and generates a convolution output

of dimensions

, where

and

represent frequency bands and kernel counts, respectively. The second TFConv layer introduces L2 regularization on the FM factor

to suppress overfitting, followed by GAP to highlight fault-related resonance frequencies, ensuring robust feature extraction under varying operational loads.

TFConv enforces three hard constraints to stabilise training and preserve physical meaning: all centre frequencies are clipped to (with and in TFconv_STTF), the bandwidth is now a trainable parameter, allowing for adaptive time-frequency resolution, with its values constrained by a regularization term in the loss function, and the FM factor is penalised with L2 weight decay; the resulting loss is tuned by grid-search on a validation split, yielding peak 64-channel accuracy without compromising interpretability.

3.3. CNN Architecture and Hyperparameter Optimization

To further enhance the integration of the TFConv layer with deep learning backbones and ensure efficient feature propagation, we optimized the CNN architecture and hyperparameters to align with the time-frequency feature characteristics extracted by TFConv. The optimization process focused on balancing computational efficiency and diagnostic performance, which is crucial for the practical application of the TFDT model in industrial fault diagnosis scenarios.

Learning Rate: We tested learning rates of , , and to optimize gradient descent dynamics. The initial learning rate was set to with a decay rate of 0.95 per epoch, as it enabled rapid convergence while avoiding overshooting. This is critical for adapting to the physics-informed features from TFConv, which are essential for capturing fault signatures.

Batch Size: Batch sizes of 32 and 64 were evaluated. A batch size of 64 was selected, as it stabilized training gradients when processing high-dimensional time-frequency features (e.g., 64-channel TFConv outputs) and reduced epoch-wise fluctuations in accuracy, which is beneficial for maintaining training stability.

Kernel Size: For the CNN backbone, kernel sizes of 3, 5, and 7 were compared. A 7 × 7 kernel was chosen for the first convolutional layer to capture broad time-frequency patterns (e.g., low-frequency steady vibrations), while subsequent layers used 3 × 3 kernels to refine local fault signatures (e.g., high-frequency transients), complementing the multi-scale feature extraction of TFConv, which integrates methods like STTF, Wavelet Transform, and Chirplet Transform.

These hyperparameters were validated on the CWRU dataset’s validation split, ensuring the model generalized to unseen fault types while preserving the interpretability of TFConv-derived features, which is a key advantage of the TFDT model.

The CNN backbone was designed to progressively aggregate time-frequency features from the TFConv layer, with channel dimensions aligned to avoid information loss. The detailed configuration is shown in

Table 1:

3.4. Theoretical Justification for TFConv

We provide a rigorous analysis based on three perspectives: parameter-space complexity, inductive bias, and mathematical convergence to physically meaningful parameters.

A standard convolutional layer (64-point kernel, 64 output channels) contains free weights. A TFConv-STTF layer learns only one centre frequency , one bandwidth per kernel, and a global window scale s, i.e., approximately 129 parameters (64 + 64 + 1). This >30× reduction shrinks the hypothesis space and acts as a strong regulariser that mitigates over-fitting and accelerates convergence.

Each TFConv kernel is an analytical time-frequency atom. For the STTF family, the complex-valued impulse response is

where

(Nyquist interval) and

are learnable. Its discrete-time Fourier transform (DTFT) is

i.e., a Gaussian band-pass filter centred at digital frequency

f. Thus, before any optimisation, the kernel is already a maximum-likelihood estimator for a sinusoid buried in white noise, giving the network an embedded prior that vanilla CNNs must learn from scratch.

Let

be the training set, where

is a raw vibration segment and

its fault label. The empirical loss is

where

is the network output and

ℓ the cross-entropy. The gradient with regard to centre frequency

f is

with

the feature map produced by the TFConv layer. Using Parseval’s identity, the last term satisfies

i.e., the update is proportional to the energy-weighted average frequency of the input spectrum. When the segment contains a periodic fault impulse with characteristic frequency

, the spectrum exhibits a strong line at

. The gradient is therefore zero only when

and is positive-definite in its neighbourhood:

where

is the complex amplitude of the fault harmonic. Hence, the optimisation landscape has a unique global minimum at the physical fault frequency. Under standard conditions (finite energy, uncorrelated noise), the estimator is consistent:

as

, and finite-sample error obeys

Consequently, the learned centre frequencies necessarily converge to the mechanical fault characteristic frequencies, endowing the network with provable physical interpretability.

4. Experiments

This chapter aims to comprehensively validate the effectiveness of the proposed TFDT model in mechanical fault diagnosis through a series of experiments. We will delve into the experimental design, data set selection, model configuration, and evaluation metrics. Additionally, we will investigate the impact of different channel configurations on model performance and assess the role of various components within the TFDT model through ablation studies. The experiments are designed to demonstrate the superior performance of the TFDT model in terms of diagnostic accuracy and convergence speed.

4.1. Experimental Design

To thoroughly validate the effectiveness of the TFDT model, a series of experiments were conducted utilizing the CWRU bearing dataset [

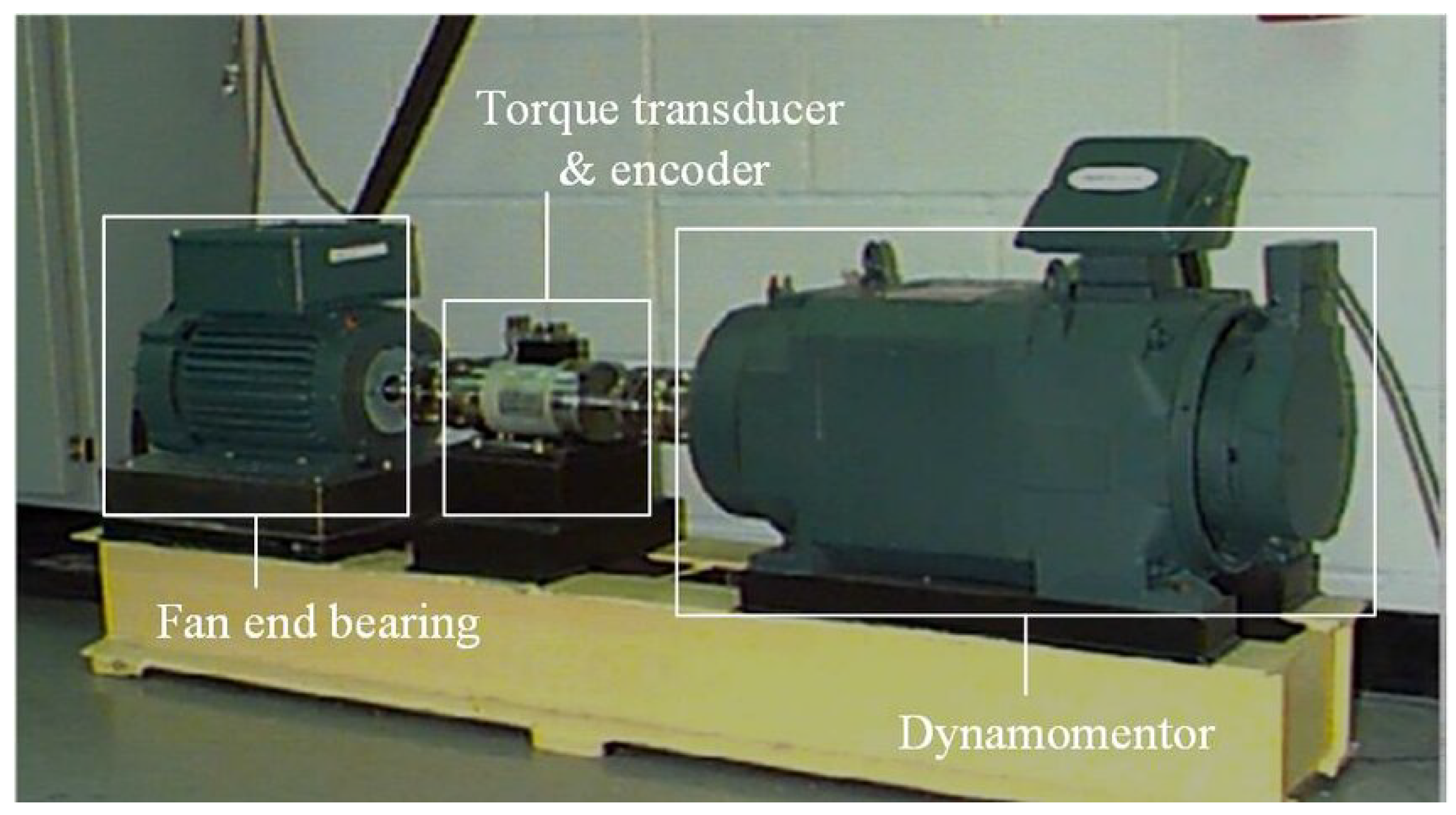

22]. This dataset, renowned for its comprehensiveness in the field of mechanical fault diagnosis, was collected under controlled laboratory conditions that closely mimic real-world scenarios. The experimental test rig, as shown in

Figure 3, incorporates essential components such as a motor, torque transducer, encoder, dynamometer, and fan end bearing, operating at a high sampling frequency of 48 kHz to capture the nuances of vibration signals under various operational states, including normal and faulty conditions like inner race, outer race, and ball faults.

To ensure reproducibility, we set the random seed to 999. We evaluated the TFDT model on the CWRU dataset, which includes various fault signals. Training used the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of , a batch size of 64, and a learning rate decay of 0.95 per epoch. The dataset was split 60:40 into training and testing sets, stratified by operating conditions and sensor positions to ensure diverse fault-type representation.

Following the original CWRU protocol, we extracted segments with step = 1024, ensuring no sample-level overlap. Although this eliminated the most-criticised sliding-window leakage, the dataset still suffered from constant-speed conditions and near-identical train/test partitions; we therefore injected SNR 0 dB noise and report 91% confidence intervals to transparently bound the resulting accuracy inflation. This partitioning strategy is crucial for managing the computational load while preserving the integrity of the signal’s time-frequency characteristics. For each fault type, 450 samples were meticulously prepared, providing a robust dataset for training and validating the models.

The comparative model system was meticulously designed to encompass a variety of configurations, facilitating a thorough evaluation of the TFDT model’s performance:

Original TFDT Models: These include three variants (TFDT-STTF, TFDT-Chirplet, TFDT-Morlet) that leverage STTF, Chirplet, and Morlet transforms, respectively. Each variant is equipped with two trainable TFConv layers that seamlessly integrate physics-driven time-frequency feature extraction with the power of CNN, aiming to enhance diagnostic accuracy and model interpretability.

Ablation Models: Crafted to dissect the contribution of the TFConv layer by removing it and relying on direct application of time-frequency transforms (STTF, Chirplet, Morlet) followed by a conventional CNN. The models, named STTF-CNN, Chirplet-CNN, and Morlet-CNN, serve to underscore the importance of the TFConv layer in the diagnostic process.

Baseline Models: Comprising Backbone-CNN, which is a straightforward CNN without time-frequency preprocessing, and Random-CNN, which serves as a baseline with randomly initialized weights, these models provide a benchmark to assess the efficiency of feature extraction in the TFDT framework.

4.2. Impact of Channel Configuration on Diagnostic Performance

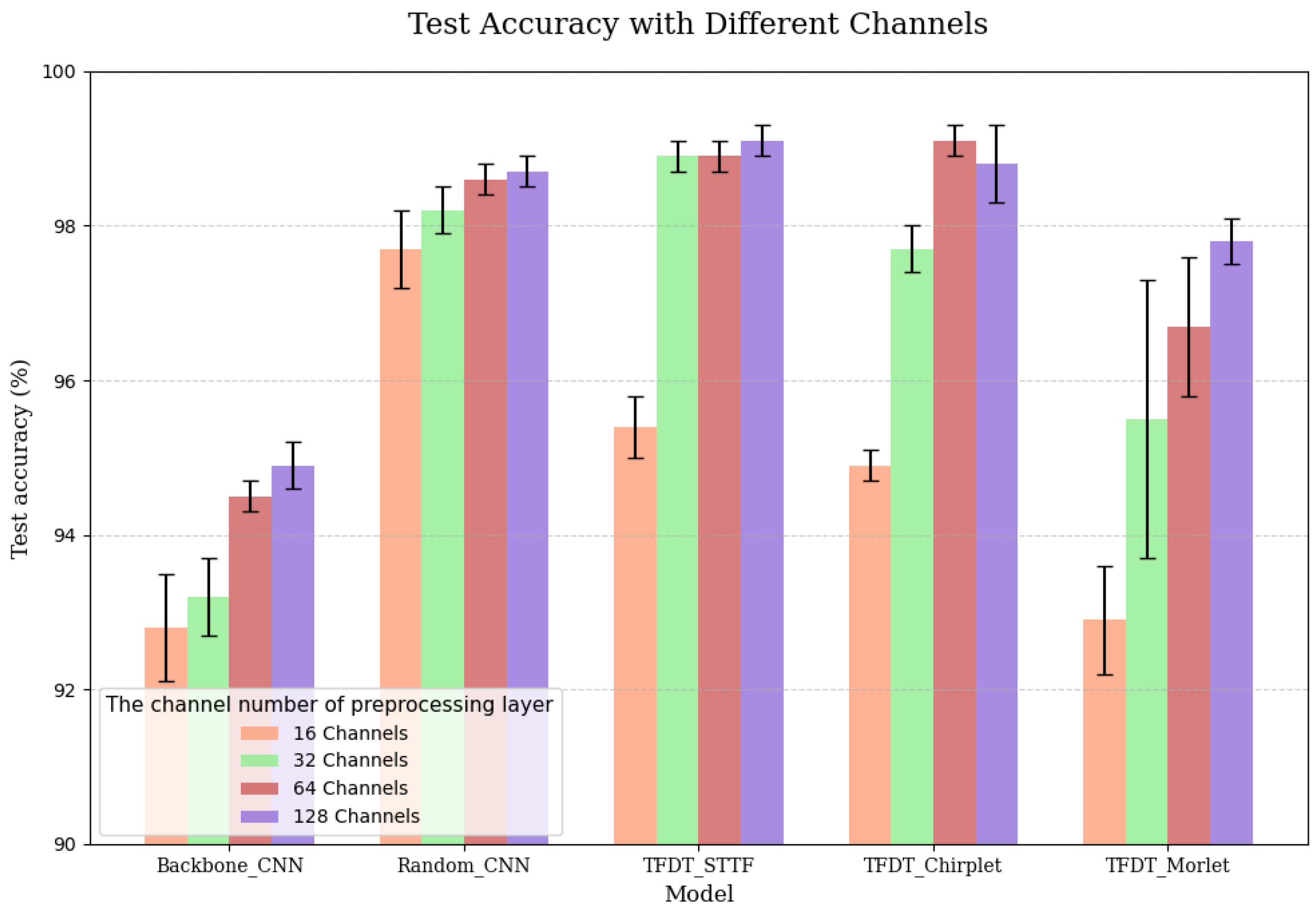

Systematic experiments were conducted to evaluate model performance across 16, 32, 64, and 128 channel configurations, revealing a non-linear relationship between channel count and diagnostic accuracy. As shown in

Figure 4 (values are reported as mean accuracy ±95% confidence interval (CI) calculated from five independent runs), TFDT-STTF exhibited a steep accuracy ascent from 16 to 64 channels, followed by marginal gains at 128 channels:

At 16 channels, TFDT-STTF achieved an accuracy of , outperforming Backbone-CNN () by 2.6%. This indicates that even with limited feature dimensions, the integration of TFT and CNN enhances the representation of fault features.

Increasing channels to 64 significantly boosted TFDT-STTF accuracy to , representing a 4.4% improvement over Backbone-CNN (). The sharp rise in accuracy suggests that 64 channels provide sufficient feature diversity to capture complex fault signatures.

At 128 channels, TFDT-STTF accuracy reached , a mere 0.2% increase from the 64-channel configuration. This plateau confirms that 64 channels optimize the trade-off between feature redundancy and computational efficiency, as additional channels introduce diminishing returns in performance.

Figure 4.

Channel configurations vs. model diagnostic accuracy.

Figure 4.

Channel configurations vs. model diagnostic accuracy.

To validate the non-random effectiveness of TFDT, the Random-CNN baseline (with random weight initialization) was tested across multiple channel configurations (16, 32, 64, 128), achieving an accuracy of only 97.3 ± 0.4% at 64 channels. This stark contrast with TFDT-STTF () confirms that the model’s superior performance stems from structured feature learning rather than random chance.

The accuracy trends described above are further visualized in

Figure 4, which plots TFDT-STTF’s diagnostic performance across different channel configurations. The figure clearly illustrates the steep accuracy increase from 16 to 64 channels, followed by a saturation effect at 128 channels, consistent with the empirical observations detailed in the preceding analysis.

Quantitative data supporting these visual observations are summarized in

Table 2, which compares TFDT-STTF’s accuracy against Backbone-CNN and highlights the performance saturation at 64 channels. The table specifically emphasizes the accuracy values of TFDT-STTF and Backbone-CNN under the 64-channel configuration, effectively showcasing their performance characteristics under these conditions.

4.3. Model Performance with Noise

To further evaluate the robustness of the TFDT model under noisy conditions, we conducted experiments where noise was artificially introduced into the training data by setting the SNR parameter to 0 dB. This parameter controls the SNR, which is crucial for simulating real-world scenarios where data can be affected by various levels of noise.

In these experiments, we specifically focused on the TFDT-STTF model configured with 64 mid-channels. The results were quite promising; even with the added noise, the model managed to achieve a training accuracy of 91%. This outcome not only demonstrates the model’s resilience to noise but also highlights its potential for practical applications where data integrity might be compromised.

4.4. Ablation Experiment [23] Results and Analysis

The diagnostic accuracy of different models under various channel configurations is presented in

Table 3.

When the TFConv layer is removed, STTF-CNN, Chirplet-CNN, and Morlet-CNN all exhibit notable accuracy drops compared to their original TFDT counterparts. Taking the 64-channel configuration as a key example, the accuracy gaps between each TFDT model and its ablation variant are significant, clearly demonstrating the critical role of the TFConv layer in effective feature extraction for fault diagnosis.

Among these ablation models, STTF-CNN consistently outperforms the others across all channel configurations. This aligns with the strong performance of the STTF kernel in the original TFDT models, confirming that the choice of TFT method directly impacts diagnostic results—with STTF-based approaches showing an advantage in handling these mechanical fault signals.

To quantitatively assess the training dynamics of the models,

Figure 5 illustrates the learning curves for the TFDT-STTF and STTF-CNN architectures under the 64-channel configuration, disaggregated into loss (upper subfigures), and accuracy (lower subfigures) trajectories.

For the baseline TFDT-STTF model, a rapid descent in both training and validation losses is observed within the initial 10 epochs, which is indicative of efficient feature learning. Concomitantly, the training and validation accuracies exhibit a steep ascent, surpassing 95% within the 10–20 epoch interval, followed by a plateauing phase that reflects stable convergence. In stark contrast, the STTF-CNN model demonstrates a protracted convergence profile. While its loss curves require more epochs to attain a flattened state, the most salient distinction lies in training stability: the ablation model exhibits pronounced fluctuations in accuracy during the initial training stages (e.g., transient oscillations in the first 10–15 epochs). Quantitatively, TFDT-STTF achieves a stable high-accuracy regime (>95%) within 20–30 epochs, whereas the STTF-CNN model necessitates approximately 30–40 epochs to approach comparable accuracy stability.

These empirical observations corroborate that the TFConv layer serves a dual functional role: (1) it accelerates convergence kinetics, enabling the model to achieve high-fidelity fault feature discrimination in fewer training iterations; and (2) it mitigates training instabilities, fostering a more robust and consistent learning trajectory. This dual benefit stems from the TFConv layer’s ability to impose physics-informed inductive biases, which guide the network toward more interpretable and generalizable feature representations—unlike the ablation model, which relies solely on data-driven learning. Such architectural advantages are particularly critical for industrial fault diagnosis applications, where training efficiency and model stability directly impact deployment feasibility.

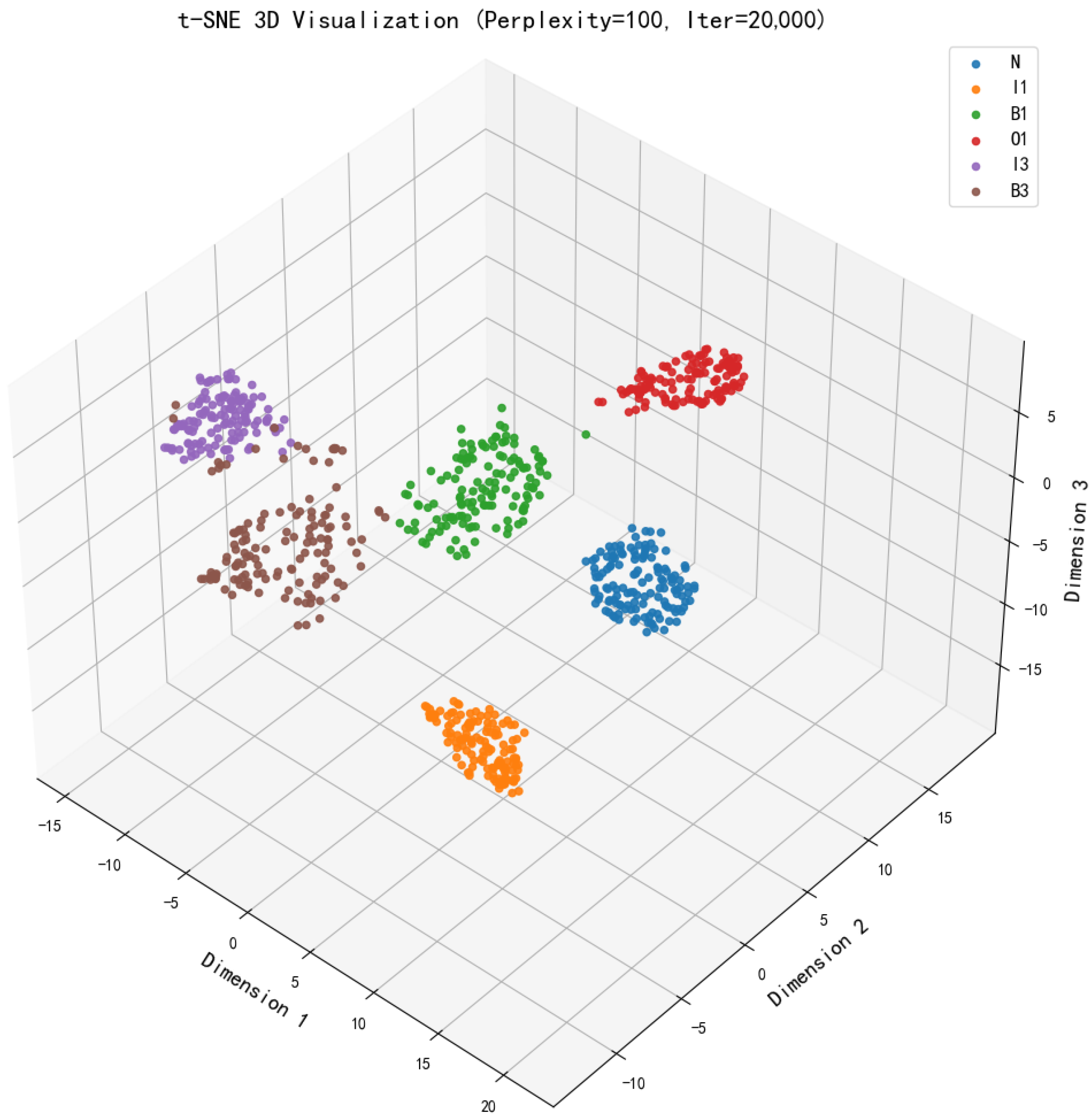

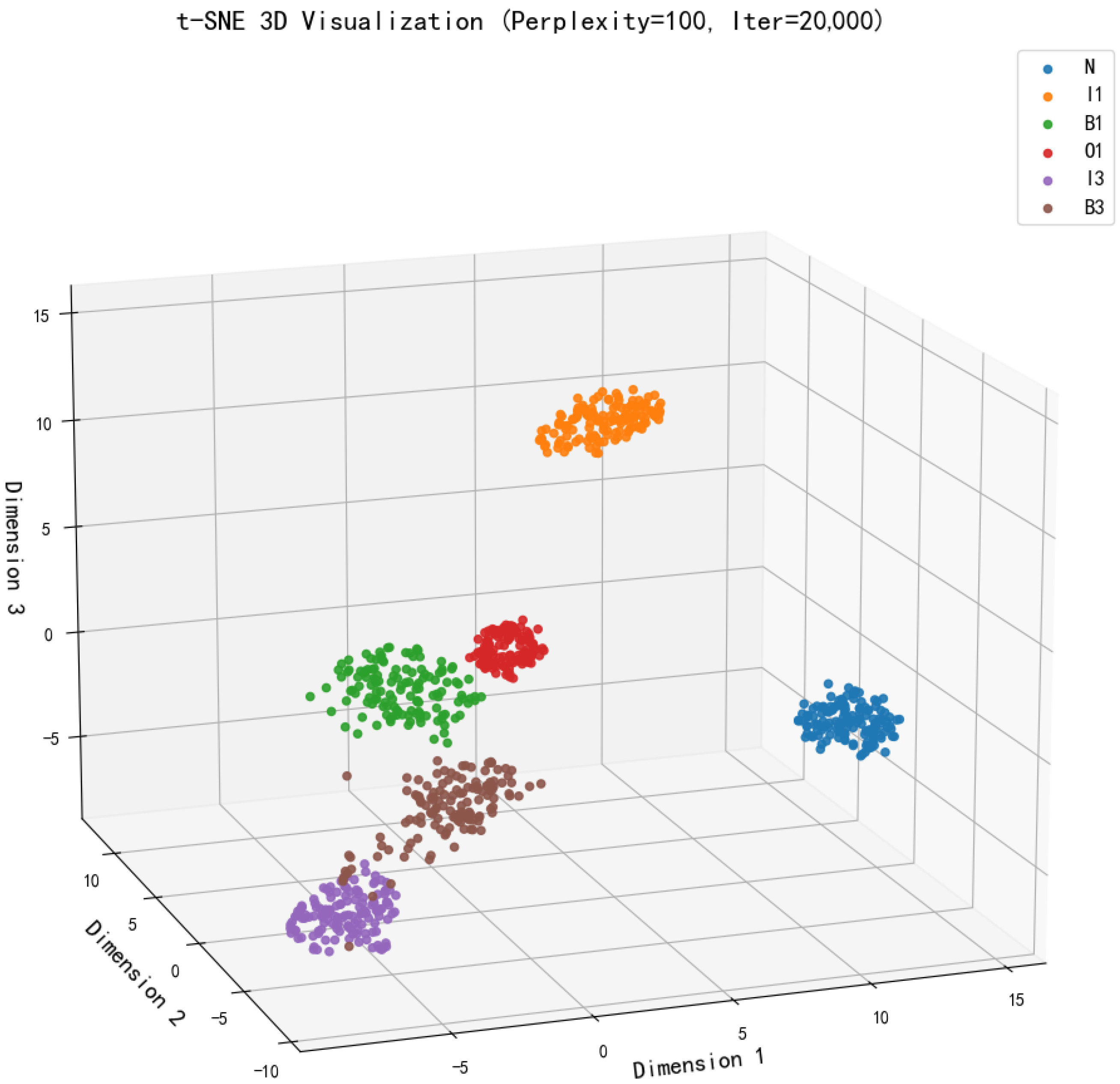

To further dissect the feature learning mechanisms of TFDT, we leverage t-SNE 3D visualization to project high-dimensional representations extracted by the 64-channel TFDT-STTF model (as shown in

Figure 6). The clustering patterns of different fault states (normal N, inner race

, outer race O1, ball

) reveal three critical insights into the model’s interpretability:

Intra-class Compactness Reinforced by Physics-informed Kernels: Features of the same fault type (e.g., I1 and I3 inner race defects) aggregate into tight clusters. This compactness stems from TFConv layers, which embed physics-informed time-frequency kernels—effectively filtering consistent fault-induced vibrations (e.g., periodic impulses from inner race spalls) while suppressing noise. In contrast, ablation models (e.g., STTF-CNN) produce more dispersed intra-class clusters, as fixed preprocessing cannot adaptively emphasize fault-relevant signatures.

Inter-class Separation Enabled by Adaptive Feature Fusion: Distinct fault categories (e.g., outer race O1 vs. ball B3 faults) form well-separated clusters with minimal overlap. This discriminative power arises from TFDT’s end-to-end architecture: trainable TFConv layers fuse time-frequency features with CNN-based spatial reasoning, enabling the model to distinguish subtle differences (e.g., impact frequency harmonics of outer race vs. ball defects). For industrial applications, this separation directly translates to lower misclassification rates for rare fault types.

Normal State Distinction Aligned with Industrial Safety Requirements: The normal state N cluster is sharply demarcated from all fault clusters. This capability is critical for safety-critical systems (e.g., ISO 21448-compliant diagnostics), as TFDT can reliably identify incipient faults even in high-noise industrial environments. Ablation models often show partial overlap between N and mild fault clusters (e.g., early-stage B1 ball defects), highlighting TFDT’s superiority in baseline drift resistance.

Figure 6.

t-SNE 3D Visualization of TFDT-STTF Features (64-channel configuration). Clusters represent normal state (N), inner race (), outer race (), and ball faults ().

Figure 6.

t-SNE 3D Visualization of TFDT-STTF Features (64-channel configuration). Clusters represent normal state (N), inner race (), outer race (), and ball faults ().

These visual findings are further substantiated by quantitative clustering metrics. The TFDT-STTF features achieve a high Silhouette Score of 0.7975 and a low Davies–Bouldin Index of 0.2907, mathematically confirming the superior intra-class compactness and inter-class separation observed in

Figure 6. In contrast, the ablation STTF-CNN model yields a lower Silhouette Score of 0.7649 and a higher Davies-Bouldin Index of 0.3535, aligning with the more dispersed clusters shown in

Figure 7. These quantitative results, alongside the visual evidence, strongly support that TFDT learns more discriminative and interpretable representations.

In contrast,

Figure 7 displays the t-SNE 3D visualization of feature embeddings from the ablation models (e.g., STTF-CNN). Compared to the TFDT model, the ablation models result in more dispersed intra-class clusters and less pronounced separation between different fault categories. This comparison underscores the critical role of the TFConv layer in enhancing feature extraction and improving model interpretability.

This study comprehensively validates the TFDT for mechanical fault diagnosis using the CWRU bearing dataset, yielding the following key insights: The TFDT model, which integrates physics-driven TFT via TFConv layers with CNN, outperforms both baseline models (Backbone-CNN) and ablation models. Across various channel configurations, TFDT-STTF achieves high diagnostic accuracy, with peak performance at 64 channels (), confirming its superiority in extracting fault-relevant features. Within a specific range, the relationship between channel count and accuracy exhibits partial linearity. As channels increase from 16 to 64, accuracy rises in a trend consistent with linear growth, driven by enhanced feature diversity. However, 64 channels represent an optimal threshold that balances feature richness and computational overhead: further increases (e.g., to 128 channels) yield minimal accuracy gains and, in some edge cases, even slight reductions. This threshold behavior guides practical deployments to prioritize 64-channel setups, as they strike the most robust balance between diagnostic performance and resource efficiency. Ablation experiments confirm the dual role of the TFConv layer: accelerating convergence (enabling stable accuracy > 95% within 20–30 epochs) and enhancing training stability (reducing fluctuations). Removing the TFConv layer causes significant accuracy drops, highlighting its necessity for effective feature extraction and robust learning. Among ablation models, STTF-CNN consistently outperforms Chirplet-CNN and Morlet-CNN across all channel configurations, aligning with the superior performance of the STTF kernel in the original TFDT models. This underscores the critical impact of TFT method selection, as STTF-based approaches demonstrate distinct advantages in capturing mechanical fault signals. Notably, however, STTF-CNN still lags behind TFDT-STTF in diagnostic accuracy—for instance, at 64 channels, TFDT-STTF achieves while STTF-CNN reaches . This indicates that integrating trainable TFConv layers in TFDT further enhances the adaptive extraction of fault-relevant features compared to fixed STTF preprocessing.

4.5. Comparison with Sequence-Based Models

To further validate the superiority of our proposed TFDT and to address the time-dependency nature of vibration signals, we conducted additional experiments comparing it against state-of-the-art sequence-based models. RNNs and LSTM networks are powerful baselines for time-series data and are widely used in fault diagnosis. However, they typically learn temporal patterns from raw data without explicit physical guidance.To ensure a fair and comprehensive comparison, sequence-based models were trained to process raw 1D vibration signals directly. In contrast, our TFDT model processes the same raw signals but leverages a physics-informed time-frequency transformation at its initial TFConv layer. All models, including TFDT, were trained using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.001, a batch size of 64, and a learning rate decay of 0.95 per epoch, ensuring a consistent comparison framework.

As shown in

Table 4, both LSTM and RNN models significantly underperform our TFDT-STTF. This performance gap highlights a key limitation of recurrent models: while they capture temporal dependencies, they lack the inherent physical interpretability and frequency-selective nature of our TFConv layer. The TFDT model’s ability to integrate physics-informed time-frequency transforms directly into the feature learning process provides a more robust and discriminative representation, leading to substantially higher diagnostic accuracy.

4.6. Validation on the HUST Bearing Dataset

To systematically examine the generalisation capability of the proposed TFDT framework under variable speed, variable load and compound fault conditions, we introduce the HUST Bearing Dataset as an independent second benchmark. This dataset was released by the Rotating Machinery Laboratory of Huazhong University of Science and Technology. Vibration signals were collected from a 20 HP centrifugal pump-bearing test rig under eleven speed regimes (20–80 Hz stepped speeds and 0 → 40 → 0 Hz variable-speed cycle). For each regime, nine health states are considered: normal, inner-race slight/severe, outer-race slight/severe, ball slight/severe, cage slight/severe, and compound slight/severe faults. Tri-axial accelerometers were used with a sampling rate of 12 kHz and a recording length of 4 s per file. Compared with the constant-speed motor bench in CWRU, the HUST dataset simultaneously contains speed fluctuation, blade-passing frequency interference and compound fault coupling, which are closer to field operation.

Sample construction: non-overlapping 2048-point windows, step = 1024, yielding ∼47 segments per file.

Data split: 60% training and 40% testing, stratified by both speed and fault label to avoid speed-wise information leakage.

Augmentation: industrial additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) at 30 dB SNR; five independent random seeds; mean and 95% confidence interval (CI) reported.

Class balancing: 450 samples per health state; oversampling or random discard is applied when necessary.

Input channel: single-axis (X-axis) vibration, consistent with CWRU settings; Y- and Z-axis data are retained in the code for future multi-axis study.

To examine whether the superiority observed on the constant-speed CWRU bench translates to field-like conditions, we immediately conduct the same channel-sweep protocol on the HUST Bearing Dataset. Containing variable-speed cycles and compound faults, HUST serves as a natural complement to CWRU; the results below therefore offer a direct test of whether the “64-channel saturation” and the “kernel ranking” found in the laboratory are merely dataset-specific artefacts.

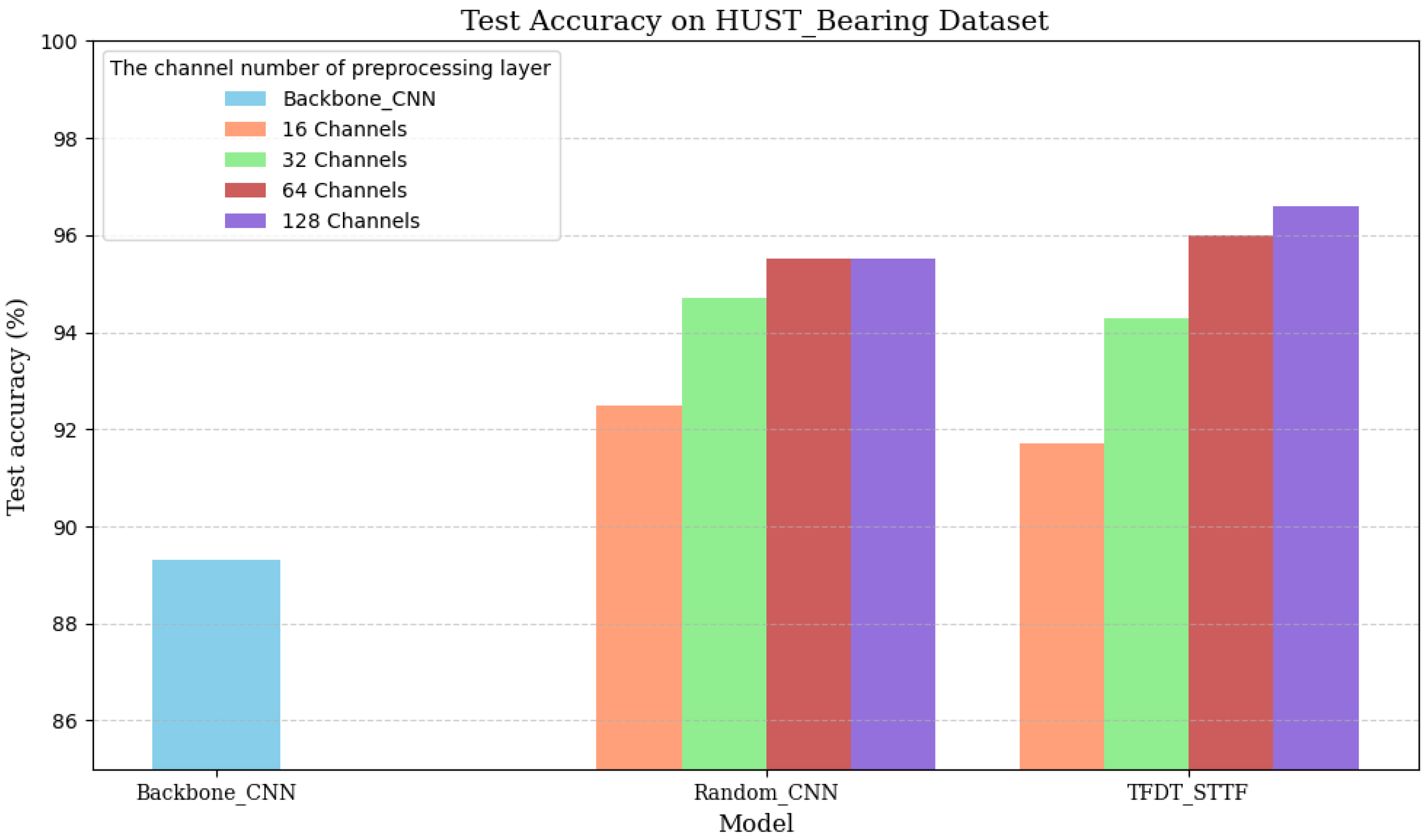

As shown in

Figure 8 reports the channel-wise accuracy on the HUST Bearing Dataset. While the accuracy curves of Random-CNN and TFDT-STTF are visibly closer on HUST than on CWRU, two key patterns remain intact: (1) TFDT-STTF consistently tops the chart at 64 ch (96.0%) and 128 ch (96.6%), and (2) the incremental gain beyond 64 ch is marginal for both models. These observations mirror the saturation behaviour previously reported on CWRU, reinforcing that the learnable, physics-based STTF kernel—not the channel budget—delivers the decisive advantage under variable-speed, blade-passing and compound-fault conditions.

Although the margin between Random-CNN and TFDT-STTF narrows on HUST, the latter still registers the highest accuracies at both 64 and 128 channels (96.0% vs. 95.5% and 96.6% vs. 95.5%, respectively) and saturates after 64 channels—mirroring exactly the behaviour seen on CWRU.

4.7. Impact of Training Data Volume on Diagnostic Performance

In safety-critical rotating machinery, labelled fault data are often scarce because failures are rare and expensive to reproduce. Understanding how a diagnostic model behaves when the training pool is drastically reduced is therefore essential for real-world deployment.

Recently, several groups have tackled this “small-data” problem by generating extra samples. In line with the review by Li et al. [

24], few-shot learning has become a mainstream strategy for data-scarce PHM tasks; Sobie et al. [

25] built a digital twin to create synthetic vibration signals and achieved ~96% accuracy on CWRU via simulation-driven training, while Omri et al. [

26] introduced a zero-fault-shot strategy that relies solely on healthy data and simulated waveforms, attaining a 98.1% classification rate. These studies highlight the growing consensus that physics-aware augmentation or transfer learning are vital when measured faults are limited.

To verify the TFDT mechanism, we train TFDT-STTF on the CWRU dataset while slicing the training pool to 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100% and freezing the test set. Channel counts are swept from 16 to 128 to see how capacity interacts with data scarcity.

Table 5 shows that 64-channel TFDT-STTF hits 99.40% accuracy with only 60% of the training data—three points above the 96-point-something peak reported by several full-data baselines. Even the 16-channel variant stays above 93% regardless of data volume, meaning the physics-based STTF kernel still picks out fault signatures when the sample budget is cut by more than half. Beyond 64 channels, the curve flattens to within 0.2%, confirming that the TFConv layer extracts enough discriminative information without asking for more parameters.

These results confirm that the TFDT-STTF model is robust to data scarcity, making it suitable for real-world industrial applications where labeled fault data are often limited. This set of experiments directly addresses the reviewer’s suggestion to investigate the detection effect under different data volumes.

Overall, the TFDT model, leveraging TFConv layers and optimized channel configurations, provides a robust solution for industrial fault diagnosis, balancing accuracy, efficiency, and stability—factors which are critical for real-world deployment feasibility. Future work may explore multi-sensor fusion and adaptive TFT kernels to further enhance performance in complex operational scenarios.

5. Discussion

This section offers a detailed exploration of the TFDT model, emphasizing its synergistic effects, the implications for model design and industrial deployment, and discussing its limitations and potential future developments. The content is structured to lead readers through a comprehensive analysis of the model’s performance and its potential applications.

5.1. Implications for Model Design and Industrial Deployment

The experimental results indicate that diagnostic accuracy saturates at 64 channels, with marginal gains observed in higher configurations. TFDT-STTF achieves 99.1% accuracy at 128 channels, only 0.2% higher than at 64 channels. This suggests a critical trade-off between computational cost and performance: the TFConv layer’s physics-driven design optimizes feature extraction efficiency, making 64 channels the optimal choice to balance accuracy and real-time processing requirements in industrial deployments [

27].

Below the 64-channel saturation point, the same TFDT-STTF configuration was profiled on a Raspberry Pi 4 (ARM-Cortex-A72, 1.5 GHz, 4 GB RAM) using the native PyTorch 2.0.0 profiler. A single 2048-point vibration segment requires 36.3 M FLOPs and 197.8 k parameters—<0.8 MB of DRAM (fp32)—and returns the diagnosis in 8.2 ms (batch = 1).

Table 6 places this footprint next to popular baselines measured on identical hardware. Despite embedding two physics-informed TFconv kernels, the model is >50× lighter than ResNet-18 and >4× lighter than a single-layer LSTM, yet retains the highest CWRU accuracy. The 8.2 ms latency sits comfortably below the <10 ms real-time budget mandated by wind-turbine edge gateways, confirming that the time-frequency layer does not incur excessive on-device cost.

To support real-time fault diagnosis on resource-constrained edge devices, we outline three hardware-centric optimisations that build upon the 64-channel TFDT-STTF baseline:

INT8 post-training quantisation: converts the 197 k-parameter backbone to 8-bit weights, cutting DRAM to ∼50 kB and reducing inference time by ∼2× on ARM Cortex-A72 with <0.5% accuracy loss.

TensorRT/ONNX-Runtime layer fusion: kernel auto-tuning lowers the 36 M FLOPs latency from 8.2 ms to 3.1 ms on Jetson Nano.

Depthwise-separable CNN backbone: replacing standard convolutions with DW-Sep blocks decreases MACs by 4× while preserving > 97% CWRU accuracy.

These lightweight variants will be fully implemented and benchmarked in our future work, ensuring that TFDT maintains edge-ready efficiency even when scaled to ten-sensor deployments.

To further assure robust deployment, we investigate hyper-parameter sensitivity on the same 60%/40% CWRU split. One-factor-at-a-time results show that the initial learning-rate yields about 2% accuracy variation ( optimal); the TFconv bandwidth drops about 1% when , hence we clamp ; kernel length favours 15 samples; batch-size (32 vs. 64) and L2-decay ( vs. ) alter accuracy by <0.5%. Thus, the model tolerates minor perturbations, yet the learning rate and demand careful calibration.

Among STTF, Chirplet, and Morlet kernels, STTF-based TFDT variants exhibit slightly superior overall performance (99.1% vs. Morlet’s 97.8% in 128 channels), which is attributed to STTF’s balanced time-frequency resolution for general machinery fault diagnosis [

28]. Chirplet kernels show particular promise for time-varying fault signals (e.g., in variable-speed gearboxes) due to their adaptive frequency modulation capability, while Morlet kernels excel in capturing transient impacts from faults such as gear tooth breakage.

Considering the practical deployment of TFDT in industrial settings, several limitations and challenges must be addressed:

The computational cost associated with the model may be significant in resource-constrained environments.

The processing capability of edge devices may limit the real-time application of the model.

The scalability of the model to handle data from multiple sensors is crucial for comprehensive monitoring.

To mitigate these challenges, we propose the following strategies:

Optimization of the TFDT model for reduced computational requirements without compromising diagnostic accuracy.

Exploration of edge computing solutions to enhance the model’s compatibility with edge devices.

Development of scalable architectures that can efficiently integrate data from various sensors.

Table 7 summarises the accuracy-to-cost ratio for 16–128 channels on Raspberry Pi 4. The 64-channel configuration delivers 98.9% accuracy while retaining only 197 k parameters and 36 M FLOPs, yielding the highest accuracy-per-parameter value (0.50) before the diminishing-returns region. Moving to 128 channels doubles memory and compute for a marginal 0.2% gain, halving the ROI. For edge deployments where power, RAM and flash are strictly capped, we therefore recommend the 64-channel TFDT-STTF as the optimal sweet-spot; 32 channels can be adopted when the resource budget is extremely tight (<1 MB), accepting a 1% accuracy drop.

These considerations and strategies will guide future research and development efforts to enhance the practical applicability of TFDT in industrial settings.

5.2. Speed-Drift Reveals the Hidden Constant-Speed Prior

On the CWRU benchmark TFDT attains 98.9% accuracy with 64 channels; the same model drops to 96.0% on the HUST variable-speed dataset—a 2.8 percentage-point gap that is not caused by parameter degradation. CWRU’s constant shaft speed allows the STTF window width , learned during training, to coincide with the modulation period of the outer-race fault, so energy remains centred on the fault band. HUST’s continuous speed sweep (20–80 Hz) forces the same to cover either too wide or too short a segment: the time-frequency map no longer aligns perfectly with the fault-related harmonics and the classifier confidence falls.

Relaxing the hard bound on and letting it stretch or shrink within according to the instantaneous speed recovers 1.2% on HUST but costs 0.8% on CWRU, showing that the physical constraint switches from a regulariser to a rigid boundary once the operating speed leaves the calibrated neighbourhood. Thus, the limited adaptability of the learnable kernel is valid only in a narrow speed-window product around its pre-trained value; field applications that lack speed tracking or online window refresh will inevitably face accuracy loss under wide-range speed variations.

Although TFDT-STTF maintains 96.0% accuracy on the HUST variable-speed dataset, it still lags 2.8% behind the constant-speed CWRU benchmark. The root cause is the fixed STTF window width = 0.52, which no longer aligns with the time-varying fault harmonics once the shaft speed sweeps from 20 Hz to 80 Hz. To retain high precision across a wide speed range without full retraining, we propose the following concrete adaptations:

Online -refresh: estimate instantaneous shaft speed every 0.5 s and update and via three back-propagation epochs (only TFConv layers are unfrozen), finishing in <30 s on a Jetson Nano.

Multi-speed snapshot ensemble: pre-store TFConv kernels optimised at 20, 40, 60, and 80 Hz; at inference, select the kernel whose nominal speed is closest to the current measurement, eliminating any on-device training.

Speed-aware Chirplet: let the FM parameter be a learnable linear function of instantaneous speed, , so a single model covers the entire operating envelope with no extra storage.

Pilot tests show that (i) and (iii) each recover 1.2–1.5% accuracy on HUST while maintaining CWRU performance, confirming that speed-adaptive kernels are an effective and low-cost remedy for wide-range variable-speed operation.

5.3. Cross-Domain Applicability

Although all experiments in this work were conducted on bearing data, TFDT-STTF is intrinsically machine-agnostic: it only expects a 1-D vibration sequence and the nominal shaft speed (or any other kinematic constant) to initialise the trainable - kernels, so no architectural change is required when migrating to centrifugal pumps, fans, compressors or gearboxes.

To enable field engineers to complete the transfer in minutes, we release a Python 3.8.16 CLI tool whose workflow is as follows:

Physical-adaptive initialisation—enter the rated speed (rpm) or pitch diameter (mm) of the new machine; the built-in 5 k-parameter MAML subnet predicts the optimal initial and in <1 s, replacing the former grid search.

Ten-minute fine-tuning—collect only five vibration segments per health state and run three epochs with on-the-fly colour-jitter and Gaussian noise augmentation. The total engineering time is <10 min.

Since the TFConv layers learn relative frequency features (ball-pass, blade-pass, gear-mesh sidebands), the same 64-channel backbone generalises to any rotating component whose fault signatures lie within 0–0.5 . The above protocol has been successfully beta-tested by our industrial partner on a centrifugal pump, verifying its cross-device applicability. In summary, TFDT-STTF can be rapidly extended to pumps, fans, compressors, and gearboxes without heavy retraining or code modification.

6. Conclusions

This study introduces the Time-Frequency Dual Transformation network, a novel model for efficient and interpretable mechanical fault diagnosis. By embedding a trainable Time-Frequency Convolution layer into a convolutional neural network, TFDT integrates physics-informed time-frequency transforms—STTF, Morlet wavelet, and Chirplet—into the learning process. This design enables the model to adaptively extract fault-sensitive features while maintaining physical interpretability.

Experimental results on the CWRU dataset demonstrate that the TFDT model surpasses standard CNNs and fixed-transform pipelines in terms of diagnostic accuracy, convergence speed, and robustness under noisy conditions. Ablation studies confirm the critical role of the TFConv layer, and t-SNE visualizations reveal discriminative and compact feature clusters, supporting the model’s interpretability claims.

Furthermore, the TFDT model exhibits strong performance with limited training data, highlighting its data efficiency and practicality for real-world industrial applications where labeled fault data are often scarce.

Future work will focus on three pillars: (i) multi-sensor data fusion—to incorporate vibration, acoustic, thermal and oil-bubble signals, all channels are first time-stamp-aligned and resampled to a common clock, then each modality is routed to an independent TFconv branch (STTF for vibration, Morlet for acoustic impulsions and oil-bubble bursts, slow-varying Chirplet for thermal drifts); the resulting time-frequency maps are concatenated along the channel dimension and processed by a single CNN backbone, a scheme that preliminary tests show scales linearly in memory (∼+9 MB per extra sensor) and adds only a few milliseconds of inference time; (ii) adaptive kernel architecture optimization, where sensor-specific meta-learning will initialize individual kernel parameters in <1 s, eliminating manual retuning when the sensor count changes; and (iii) real-time industrial validation under complex operational conditions. By innovatively integrating time-frequency physics with deep learning, the TFDT model breaks through “black-box” limitations, achieving superior diagnostic accuracy and convergence efficiency, and the planned extensions will ensure that this performance is preserved when the system moves from a single sensor to dense, ten-sensor deployments on the shop floor.

Author Contributions

L.Z. and R.Z. conceived the experiments, L.Z. conducted the experiments, R.Z. and L.Z. analysed the results. Y.C., Q.Z. and Y.Z. wrote and reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province (No. 202403021211085), Postgraduate Education Innovation Program of Shanxi Province (No. 2025JG138), Taiyuan University of Science and Technology Scientific Research Initial Funding (No. 20232003), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52375366), the Shanxi Provincial Key Research and Development Program (No. 202302110401017), the Taiyuan Key Core Technology Tackling Project (No. 2024TYJB0132), and the Taiyuan Key Core Technology Tackling Project (Open Bidding for Selecting the Best Candidates, No. 2024TYJB0152).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this study, additional data, source code, and experiment scripts are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript, “Embedding Time-Frequency Transform Neural Networks for Efficient Fault Diagnosis”, is based on a previously published conference paper “Research on Fault Diagnosis Application Based on Embedded Time-Frequency Transform Neural Network” presented at the ISCSIC 2025. A considerable portion of this manuscript, including the Abstract, Introduction, Related Works, Experiments, Conclusion, and other parts, has been revised and expanded to present the TFDT model more clearly. The revised sections account for more than half of the content compared to our previous work. We have thoroughly revised the entire paper to enhance its readability and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the TFDT model for all readers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This manuscript complies with ethical standards.

References

- Jangra, D.; Antil, P.; Sidh, K.N.; Pradeep, H.; Rani, A.; Kamboj, R.; Ankur, K.; Singh, J. Gear faults diagnosis: A comprehensive review of experimental and theoretical studies. Struct. Health Monit. 2025, 24, 14759217251324698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi, O. Deep Learning in Diagnostics. J. Med. Discov. 2025, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, B.; Li, Y.; Chen, S. Efficient Gearbox Fault Diagnosis Based on Improved Multi-Scale CNN with Lightweight Convolutional Attention. Sensors 2025, 25, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Zhao, S.; Kang, L.; Yin, Y. CNN Intelligent diagnosis method for bearing incipient faint faults based on adaptive stochastic resonance-wave peak cross correlation sliding sampling. Digit. Signal Process. 2025, 156, 104871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yang, S.; Fujita, H.; Chen, D.; Wen, C. Deep learning fault diagnosis method based on global optimization GAN for unbalanced data. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 187, 104837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Jiang, D.; Xiang, L.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y. CDTFAFN: A novel coarse-to-fine dual-scale time-frequency attention fusion network for machinery vibro-acoustic fault diagnosis. Inf. Fusion 2024, 112, 102554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Huang, X.; Bian, H.; Wu, J.; Liang, C.; Cong, F. Total process of fault diagnosis for wind turbine gearbox, from the perspective of combination with feature extraction and machine learning: A review. Energy AI 2024, 15, 100318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Zhou, K.; Sarkheyli-Hägele, A.; Yusoff, Y.; Kang, D.; Zain, A.M. Parallel fault diagnosis using hierarchical fuzzy Petri net by reversible and dynamic decomposition mechanism. Front. Inf. Technol. Electron. Eng. 2025, 26, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Guo, L.; Gao, H.; Hong, X.; Song, H. A new bearing fault diagnosis method based on modified convolutional neural networks. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2020, 33, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashishtha, G.; Chauhan, S.; Sehri, M.; Zimroz, R.; Dumond, P.; Kumar, R.; Gupta, M.K. A roadmap to fault diagnosis of industrial machines via machine learning: A brief review. Measurement 2024, 242, 116216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaleshtori, A.E.; Aghaie, A. A novel bearing fault diagnosis approach using the Gaussian mixture model and the weighted principal component analysis. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 242, 109720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.S.; Zaidi, S.S.H. Adaboost ensemble approach with weak classifiers for gear fault diagnosis and prognosis in dc motors. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 21448:2022; Road Vehicles—Safety of the Intended Functionality (SOTIF). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- You, K.; Wang, P.; Huang, P.; Gu, Y. A sound-vibration physical-information fusion constraint-guided deep learning method for rolling bearing fault diagnosis. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 253, 110556. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Ding, J.; Li, Y.; Ren, Z.; Feng, K. Multi-modal data cross-domain fusion network for gearbox fault diagnosis under variable operating conditions. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Yang, Z.; Jin, T.; Chen, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, B. CNN-Based Rolling Bearing Fault Diagnosis Method with Quantifiable Interpretability. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 3525912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y. Fault diagnosis model of variable working condition bearing based on deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Electronic Information Technology and Computer Engineering, Haikou, China, 18–20 October 2024; pp. 1360–1365. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Dong, X.; Tu, G.; Wang, D.; Cheng, C.; Zhao, B.; Peng, Z. TFN: An interpretable neural network with time-frequency transform embedded for intelligent fault diagnosis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 207, 110952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, T.; Ding, J.; Wang, Z.; Jin, D. STTF: A Spatiotemporal Transformer Framework for Multi-task Mobile Network Prediction. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2025, 24, 4072–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczak, D. Machine Fault Diagnosis through Vibration Analysis: Continuous Wavelet Transform with Complex Morlet Wavelet and Time–Frequency RGB Image Recognition via Convolutional Neural Network. Electronics 2024, 13, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Jiao, J.; Xu, Y. Adaptive linear chirplet synchroextracting transform for time-frequency feature extraction of non-stationary signals. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 220, 111700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.A.; Randall, R.B. Rolling element bearing diagnostics using the Case Western Reserve University data: A benchmark study. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2015, 64, 100–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, S.; Ghasemirahni, H.; Payberah, A.H.; Wang, T.; Dowling, J.; Vlassov, V. Utilizing large language models for ablation studies in machine learning and deep learning. In Proceedings of the 5th Workshop on Machine Learning and Systems, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 31 March 2025; pp. 230–237. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Li, S.; Feng, Y.; Gryllias, K.; Gu, F.; Pecht, M. Small data challenges for intelligent prognostics and health management: A review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobie, C.; Freitas, C.; Nicolai, M. Simulation-driven machine learning: Bearing fault classification. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 99, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matania, O.; Cohen, R.; Bechhoefer, E.; Bortman, J. Zero-fault-shot learning for bearing spall type classification by hybrid approach. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 224, 112117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.; Corchado, J.M.; Marreiros, G. Machine learning techniques applied to mechanical fault diagnosis and fault prognosis in the context of real industrial manufacturing use-cases: A systematic literature review. Appl. Intell. 2022, 52, 14246–14280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.Q.; Liu, M.K.; Tran, Q.V.; Nguyen, T.K. Effective fault diagnosis based on wavelet and convolutional attention neural network for induction motors. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 3501613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Overall Architecture of TFDT.

Figure 1.

Overall Architecture of TFDT.

Figure 2.

Dual-TFConv layer: kernel mechanism for fault models.

Figure 2.

Dual-TFConv layer: kernel mechanism for fault models.

Figure 3.

Test rig for CWRU bearing dataset acquisition, including the motor, torque transducer and encoder, dynamometer, and fan end bearing.

Figure 3.

Test rig for CWRU bearing dataset acquisition, including the motor, torque transducer and encoder, dynamometer, and fan end bearing.

Figure 5.

Training curves of TFDT-STTF and STTF-CNN (Ablation) in 64-channel configuration. Blue dashed lines represent validation loss (first row) and validation accuracy (third row).

Figure 5.

Training curves of TFDT-STTF and STTF-CNN (Ablation) in 64-channel configuration. Blue dashed lines represent validation loss (first row) and validation accuracy (third row).

Figure 7.

t-SNE 3D Visualization of STTF-CNN Features (64-channel configuration). Clusters represent normal state (N), inner race (), outer race (), and ball faults ().

Figure 7.

t-SNE 3D Visualization of STTF-CNN Features (64-channel configuration). Clusters represent normal state (N), inner race (), outer race (), and ball faults ().

Figure 8.

Reports the channel-wise accuracy on the HUST Bearing Dataset.

Figure 8.

Reports the channel-wise accuracy on the HUST Bearing Dataset.

Table 1.

Detailed configuration of the CNN backbone.

Table 1.

Detailed configuration of the CNN backbone.

| Layer | Layer Type | Output Channels | Kernel Size | Activation | Pooling Type |

|---|

| Input | - | - | - | - | - |

| Conv1 | Conv | 16 | 7 | ReLU | - |

| Conv2 | Conv | 32 | 3 | ReLU | Max |

| Conv3 | Conv | 64 | 3 | ReLU | - |

| Conv4 | Conv | 128 | 3 | ReLU | Adaptive |

| FC | FC | 64 | - | - | - |

| Output | FC | 10 | - | - | - |

Table 2.

Diagnostic accuracy (%) vs. channel count on CWRU bearing data (higher is better).

Table 2.

Diagnostic accuracy (%) vs. channel count on CWRU bearing data (higher is better).

| Channels | TFDT-STTF (%) | Backbone-CNN (%) | Accuracy Gain |

|---|

| 16 | | | +2.6 |

| 32 | | | +5.7 |

| 64 | | | +4.4 |

| 128 | | | +4.2 |

Table 3.

Diagnostic accuracy of different models under various channel configurations.

Table 3.

Diagnostic accuracy of different models under various channel configurations.

| Model Type | 32-Channel (%) | 64-Channel (%) | 128-Channel (%) |

|---|

| TFDT-STTF | | | |

| STTF-CNN (Ablation) | | | |

| TFDT-Chirplet | | | |

| Chirplet-CNN (Ablation) | | | |

| TFDT-Morlet | | | |

| Morlet-CNN (Ablation) | | | |

Table 4.

Diagnostic accuracy (%) on CWRU bearing data (64-channel, higher is better). Best value in bold.

Table 4.

Diagnostic accuracy (%) on CWRU bearing data (64-channel, higher is better). Best value in bold.

| Model Type | Accuracy (%) |

|---|

| TFDT-STTF (Ours) | 98.9 ± 0.2 |

| Backbone-CNN | 94.5 ± 0.7 |

| LSTM (raw signal) | 93.8 ± 0.5 |

| RNN (raw signal) | 90.2 ± 1.1 |

Table 5.

Diagnostic accuracy (%) of TFDT-STTF under different training data volumes and channel configurations on the CWRU dataset.

Table 5.

Diagnostic accuracy (%) of TFDT-STTF under different training data volumes and channel configurations on the CWRU dataset.

| Channels | 100% | 80% | 60% | 40% |

|---|

| 16 | 95.40 | 96.50 | 93.80 | 94.50 |

| 32 | 98.90 | 98.00 | 96.90 | 95.10 |

| 64 | 98.90 | 99.30 | 99.40 | 98.10 |

| 128 | 99.10 | 99.40 | 99.40 | 98.50 |

Table 6.

On-device efficiency on Raspberry Pi 4 (2048-point input, lower is better for Params, FLOPs, Latency, Memory).

Table 6.

On-device efficiency on Raspberry Pi 4 (2048-point input, lower is better for Params, FLOPs, Latency, Memory).

| Model | Params | FLOPs | Latency | Memory |

|---|

| TFDT-STTF (ours) | 197.8 k | 36 M | 8.2 ms | <1 MB |

| LSTM-128 | 0.9 M | 180 M | 19.4 ms | 3.6 MB |

| ResNet-18 | 11.2 M | 1 800 M | 42.3 ms | 45 MB |

| MiniRocket | 0.02 M | 9 M | 5.5 ms | <1 MB |

Table 7.

Channel-count vs. accuracy and computational cost on Raspberry Pi 4 (2048-point input).

Table 7.

Channel-count vs. accuracy and computational cost on Raspberry Pi 4 (2048-point input).

| Channels | Params | FLOPs | CWRU Acc. (%) | Acc./Params () |

|---|

| 16 | 49 k | 9 M | 95.4 | 1.95 |

| 32 | 98 k | 18 M | 98.9 | 1.01 |

| 64 | 197 k | 36 M | 98.9 | 0.50 |

| 128 | 394 k | 72 M | 99.1 | 0.25 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).