Abstract

Railway sites are characterized by the frequent occurrence of soil and groundwater pollution by oil. The primary reason for pollution is usually the handling of large volumes of fuels and lubricants and, to a lesser extent, other hazardous substances, which represent an increased likelihood of potential spills due to inattention and accidents. The second factor is spills due to inadequate (aged) process equipment. In the Slovak Republic, a network of locomotive depots, strategically located throughout the country, has been operated in the past. In 2008, a pilot project was implemented to survey groundwater quality at 45 sites, followed by monitoring of the quality status until 2014. The levels of petroleum hydrocarbons in groundwater were determined by spectrophotometric methods (NEC-IR and NEC-UV). The NEC-IR parameter documented very-high pollution at 14 sites, while the NEC-UV parameter documented the same very-high pollution degree at 23 sites. Statistical evaluation using Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test revealed a significant effect of the size of the site as well as activity status on the presence and intensity of pollution. The presence of light non-aqueous phase liquids (LNAPLs) was observed at almost half of the sites. Based on the evaluated data, railway sites represent a specific type of site with frequent occurrence of severe oil pollution, posing a significant environmental and health risk.

1. Introduction

In the past, railway transport was the preferred way of transporting important raw materials in Czechoslovakia. In the 1950s, raw materials such as coal, iron and oil were primarily imported from the Soviet Union. Transport volumes decreased only with the development of road transport in the 1970s. However, railway transport remained one of the important modes of transferring raw materials and products [1]. The Railways of the Slovak Republic (ŽSR) currently manage approximately 3600 km of lines, of which approximately 1500 km are electrified. The main lines, which handle the highest volume of transportation, are electrified (Bratislava—Žilina—Košice; Bratislava—Levice—Banská Bystrica) [2]. On non-electrified lines, transportation services are provided by independent traction (diesel locomotives), which is economically justified in this context. However, the use of diesel locomotives also entails certain risks. These arise from the need for service circuits to supply fuel (filling points with tanks and dispensing points), lubricants (oil storage) and other maintenance requirements in depots (for example, fire safety measures when handling flammable substances). The volumes of hazardous substances handled at railway sites have historically been and continue to be substantial. During the transition of independent traction from steam to diesel traction, which has been taking place since the 1960s, new facilities have been built in existing stations and depots (or entirely new depots have been built). These primarily included diesel and oil storage tanks, located either underground or aboveground, handling areas for filling and dispensing points, as well as the associated pipeline network. The design and construction of these facilities between 1960 and 1980 complied with the legislation and technical standards of the time. The technical installations were not sufficiently secured against unwanted leaks. The underground tanks were single-walled, pipeline systems lacked protective casings and other similar deficiencies were present. Due to the intensity of railway traffic in the past, a relatively dense network of petrol filling stations and maintenance centers for rolling stock had been built in Slovakia. Field experience indicates that significant petroleum product leaks have occurred in areas apart from the expected sources, for example, in the area of the railway track [3]. Therefore, rail transport does not only pose a risk of pollution of the soil surface layer with metals and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), but also with oil-based substances [4,5,6].

Detection and Regulatory Limits of Petroleum Hydrocarbons in Groundwater

Historically, spectrophotometric determination of non-polar extractable compounds in the infrared spectrum (NEC-IR) and non-polar extractable compounds in the ultraviolet spectrum (NEC-UV) was used in Czechoslovakia, and later in the Slovak Republic, for the detection of petroleum hydrocarbons. Both methods are non-selective; the resulting value provides an indication of the total quantity of pollution, but not its qualitative composition. The principle of non-polar extractable compound determination involves extraction from the sample using an organic non-polar solvent followed by the removal of co-extracted weakly polar organic substances through sorption on silica gel. The NEC-IR method (corresponding to the US EPA 418.1 method) captures mainly aliphatic hydrocarbons, whereas the NEC-UV method (Slovak Technical Norm 83 0540-4) is more sensitive to aromatic hydrocarbons [7].

The NEC-IR method has been applied more frequently in the past, particularly prior to the ban of the extraction reagent Freon 113 in the late 1990s. Currently, it is considered advantageous in terms of cost and time efficiency for field analysis of soil samples [8,9,10,11,12]. Its applicability for the detection of petroleum hydrocarbons in groundwater samples has been described, for example, by Almeida et al. and Simion et al. [13,14]. However, a review by Crompton showed that most of the literature documenting the method’s use originates from studies published in the 1970s [15]. Zemo et al. highlighted difficulties in identifying volatile compounds; Okparanma and Mouazen also pointed out the insensitivity of the technique to unsaturated compounds of weathered hydrocarbons [16,17].

Due to the technical limitations of the laboratory procedure, the NEC-UV method is not suitable for the detection of petroleum pollution. Although the shapes of the pollution spectra are similar, the intensity of the maximum absorption varies according to the type of pollution, and the result of the analysis is often neither accurate nor specific [15]. The potential application of the NEC-UV method for groundwater pollution detection has been reported but is based solely on differences in analytical results from a single site and without the ability to further characterize the pollutant [18]. Despite these limitations, a groundwater pollution assessment based on the NEC-UV parameter remains necessary. In this paper, an extensive dataset is presented, from which it is possible to obtain suggestive outputs for future work. Moreover, the evaluation of groundwater pollution using the NEC-UV parameter remains part of the current legislation of the Slovak Republic. Detailed analysis of the results and their inherent limitations will enable their more effective use in practice or replacement by methods with more reliable results.

An overview of the threshold limits for concentrations of petroleum substances in groundwater, expressed as NECs, valid from 1997 to the present, is provided in Table 1. The table includes limit concentrations, the exceedance of which requires a risk assessment to be conducted. For the Instruction of the Ministry for the Administration and Privatization of National Property of the Slovak Republic (MAPNP SR) and the Ministry of the Environment of the Slovak Republic (ME SR) from 1997, the relevant value corresponds to category C. In the case of the Methodological Instruction of the ME SR No. 1/2012-7 dated 27 January 2012 and Directive of the ME SR No. 1/2015-7 dated 28 January 2015; the relevant value corresponds to the intervention criterion (IT).

Table 1.

Overview of regulatory limits for the parameter NEC in groundwater.

The intervention criterion (IT) is a critical value of pollutant concentration established for soil, rock environment and groundwater. The criterion value for NEC (IR and UV) is 1.0 mg.L−1. Exceeding this threshold under the given land-use scenario assumes a high probability of risk to human health and the environment. In such cases, a detailed geological survey of the environment, including risk analysis of the polluted area, is required. The second limit value defined by current legislation is the indication criterion (ID). The criterion value for NEC (IR and UV) is 0.5 mg.L−1. It represents the limit value for the concentration of a pollutant established for soil, rock environment and groundwater, the exceedance of which may endanger human health and the environment. In such situations, monitoring of the polluted area is required.

2. Materials and Methods

In the years 2008–2014, a site survey project was conducted at 45 locations operated by ZSSK CARGO Slovakia, JSC, in response to the adoption of new European Union environmental legislation. ZSSK CARGO Slovakia, JSC, Tomášikova 28B, 821 01 Bratislava, Slovakia, is the Slovak state-owned company providing freight transport and rolling stock maintenance services. Most of the investigated sites (41) were locomotive depots, while the remaining 4 sites were of a different nature (railway station, railway terminal, transshipment yard and warehouse). The survey was divided into 3 stages. The geological work was carried out on the same methodological basis. Sampling followed the currently valid technical standards. Groundwater pollution by petroleum hydrocarbons was assessed based on NEC-UV and NEC-IR concentrations.

2.1. Stage I 2008 [19]

The first stage of the project focused on the initial identification of the presence of pollution in soil and groundwater, followed by the classification of sites based on the degree of pollution and the need for remediation. At 9 sites, light non-aqueous phase liquid (LNAPL) was present at the groundwater table. The thickness of the LNAPL layer ranged from 2 to 30 cm. Groundwater pollution by dissolved petroleum hydrocarbons was confirmed at 27 sites through NEC-UV and NEC-IR parameters, with both parameters exceeding concentrations of 1 mg.L−1. Based on the results, the sites were categorized into four groups: category A (low pollution, no remediation required), category BI (moderate pollution, high probability of remediation), category BII (moderate pollution, low probability of remediation) and category C (high pollution, remediation required).

2.2. Stage II 2008 [20]

The second phase aimed to verify the classification of sites into pollution categories established during the first phase. At 12 sites, LNAPL was observed with thicknesses ranging from 0.5 to over 30 cm. At 16 sites, dissolved petroleum hydrocarbon concentrations in groundwater exceeded the IT for both parameters. At 4 sites, the ID for NEC-IR and the IT for NEC-UV were simultaneously exceeded, while at 3 sites only the IT for NEC-UV was exceeded. A risk assessment was performed for 23 sites.

2.3. Stage III 2009–2014 [21,22,23,24,25,26]

The results of site monitoring conducted between 2009 and 2014 confirmed the levels of pollution detected during the first and second stages. In 2009, LNAPL was identified at 18 sites and in 42 wells, in 2010 at 17 sites and in 61 wells, and in 2011 at 18 sites and in 57 wells. In 2012, 10 sites were transferred to Železničná spoločnosť Slovensko, JSC, Rožňavská 1, 832 72, Bratislava, Slovakia (ZSSK, Slovak state-owned company providing personal transport services). At these sites, only the spring sampling cycle was carried out at the request of ZSSK CARGO Slovakia a.s., whereas two sampling campaigns were conducted at the remaining sites. In 2012, the presence of LNAPL was observed at 19 sites and in 44 wells. In 2012, category A and BII sites were assessed separately as part of the completion of groundwater quality monitoring. In 2013 and 2014, groundwater quality monitoring continued at 14 category C sites. At 11 sites, LNAPL was observed in 26 wells in 2013 and in 27 wells in 2014.

Following the completion of Stage III, monitoring of selected sites continued as separate geological tasks, with monitoring activities still ongoing at some locations in 2024. Geological surveys and remediations were carried out at 16 railway sites between 2009 and 2020. Between 2018 and 2023, 14 sites where the presence of environmental and/or health risks had been identified, were remediated. The authors of the article have been involved in the monitoring, surveys and remediation of selected railway sites. The presented work represents a starting point for assessing the development of pollution at individual sites. Since 2015, only selected sites, the number of which has changed continuously, have been monitored. For example, in the fall of 2015, there were 14 sites, in the winter of 2020 there were 6 sites and in the spring of 2024, there were 11 sites. Until 2022, pollution levels were monitored exclusively using the NEC-IR and NEC-UV parameters. From 2023, the NEC-UV parameter was replaced by the TPH parameter (total petroleum hydrocarbon, US EPA 8015 method). At a small number of sites (usually 1–2 sites from the set), BTEX and chlorinated aliphatic hydrocarbons concentrations (CAHs) were occasionally also monitored.

The main objective of this work was to assess the presence of groundwater contamination at a specific type of railway site (locomotive depot). The final concentrations obtained from the laboratory analyses of collected groundwater samples enabled the categorization of the sites into several groups and allowed for their mutual comparison. The first evaluation criterion was the identified degree of pollution (dissolved concentration of the pollutant), the second was the size of the site and the third was its activity status. Additionally, the presence of LNAPL was evaluated as a supplementary parameter, which cannot be ignored in this type of study. Light non-aqueous phase liquids in the rock environment act as a long-term source of pollution from which individual substances are gradually released and migrate further into the environment.

The results of geological surveys carried out in the period 2008–2014 were evaluated. Due to the extent of the processed documents, it was not possible to address the pollution at individual sites in detail. Pollution is evaluated only in terms of presence, but not its spatial extent. If NEC-IR or NEC-UV pollutants were detected at a site at concentrations exceeding the legislative criteria (ID and IT) in even a single sampling point, the site was classified as polluted. Nearly all samples were subjected to dual analysis, with both NEC-IR and NEC-UV measurements performed on the same sample. The total number of NEC-IR analyses (3400) was higher than the number of NEC-UV analyses (3250) due to variations in subproject methodologies. A limited subset of samples was analyzed solely using the NEC-IR method. Depending on the site, the number of samples evaluated ranged from 14 to 674. The highest number of groundwater samples collected over the reporting period originated from the following sites: Čierna nad Tisou (ČNT)–Transshipment Yard (674), Leopoldov (283), Košice (199) and Trenčianska Teplá (162). Two sites were excluded from the assessment due to the absence of groundwater samples, as the drilling did not reach the aquifer. A total of 42 sites were assessed. An important aspect was the exclusion of wells with a measurable LNAPL layer. In such cases, no groundwater sample was collected, and the well was not included in the assessment. If no LNAPL was detected and the concentrations of the monitored contaminants were low, the site was classified as free of LNAPL occurrence. The contamination of the sites was assessed according to the currently applicable Slovak legislation—Directive No. 1/2015-7 of the ME SR dated the 28 January 2015.

In this paper, the evaluation of site pollution is assessed based on three criteria, listed in Table 2. To examine differences between sites based on NEC-IR and NEC-UV concentrations in groundwater, the following statistical methods were used: the Mann–Whitney test and the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test. These non-parametric tests were chosen because the data did not follow a normal distribution, as determined by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, and consisted of independent samples.

Table 2.

Criteria for assessing the degree of pollution.

3. Results

3.1. Pollution in the Form of Measurable LNAPL Layer in Wells

The results of the work are particularly noteworthy due to the extensive dataset documenting groundwater pollution and the applicability of two different laboratory methods. The evaluated data represent analyses of groundwater samples, but they do not include wells in which a measurable layer of LNAPL was present. These wells were not sampled; however, the presence of LNAPL, as defined by the ME SR Directive No. 1/2015-7, poses an environmental risk and a reason for remedial action. Table 3 shows the changes in the number of wells containing LNAPL at each site over the reporting period. Data from sites that were transferred to the administration of ZSSK in the second half of 2012 are not available (Brezno, Humenné, Kraľovany, Nové Zámky, Prievidza and Vrútky). Similarly, data from sites where monitoring was terminated in 2012 (Nitra, Trnava and Zvolen) are also unavailable.

Table 3.

Evolution of the number of wells with LNAPL at individual sites.

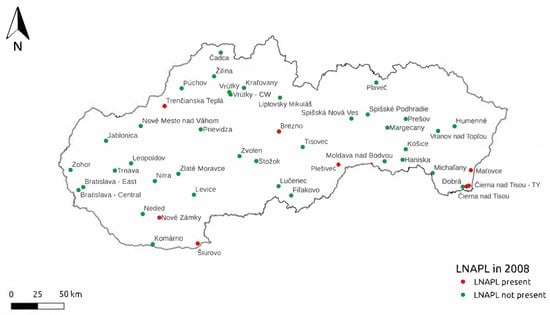

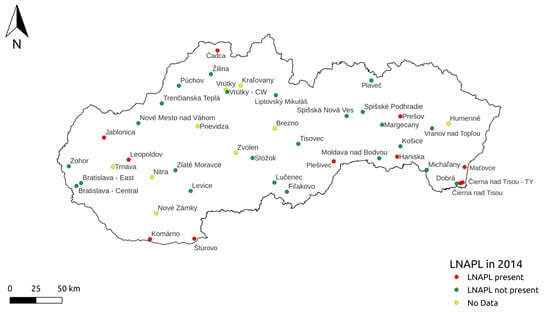

The presence of LNAPL at each site at the beginning and end of the assessment period is interpreted in Figure 1 and Figure 2. The presence of LNAPL in the monitored wells indicates a pollution over the residual saturation volume [27]. In addition to accidental releases, seasonal effects of groundwater level fluctuations on the presence/absence of LNAPL in the well can also be observed. An increase in the unconfined groundwater level will cause a decrease in the thickness of the LNAPL. Conversely, in a confined aquifer, the trend is reversed [28]. Light non-aqueous phase liquids may even completely recede from the observation well, although this does not necessarily mean the substances are absent from the pore environment of the surrounding area.

Figure 1.

Light non-aqueous phase liquids presence at the sites in 2008.

Figure 2.

Light non-aqueous phase liquids presence at the sites in 2014.

3.2. Pollution in the Form of Dissolved Petroleum Hydrocarbons

The values of the basic statistical parameters for the individual sites for the period 2008–2014 are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Basic statistical parameters for individual sites.

The site-specific averages were strongly influenced by rare extreme concentrations. For the NEC-IR parameter, 24 average values were below 0.5 mg.L−1, 6 values were in the range 0.5–0.99 mg.L−1 and 12 values exceeded 0.99 mg.L−1. For the NEC-UV parameter, the abundances in each interval were reversed. Only 7 mean values were below 0.5 mg.L−1, 8 values were in the interval 0.5–1 mg.L−1 and 27 values were above 1 mg.L−1. Median values, which were unaffected by outliers, provided a more reliable indication of the actual conditions. For the NEC-IR parameter, the maximum median value was 0.3 mg.L−1. For the NEC-UV parameter, 33 values were lower than 0.5 mg.L−1, 7 values were in the interval 0.5–0.99 mg.L−1 and 2 values were higher than 0.99 mg.L−1, with a maximum value of 1.69 mg.L−1. The maximum median values for both parameters were found in Lučenec. This was attributed to both the low number of wells (2) and samples (17), as well as the exceptionally high levels of pollution. Maximum mean concentrations for both parameters were found in Kraľovany.

Low pollution levels were detected at sites where all four parameters (means and medians for NEC-IR and NEC-UV) were below 0.5 mg.L−1 (seven sites). We consider the median NEC-IR to be the most reliable pollution indicator. Out of 17 sites where its value was 1 mg.L−1 or higher, 14 were classified as heavily polluted, which was also confirmed by the results of further geological works. An average NEC-IR value above 1 mg.L−1 was identified at 12 sites, 9 of which were remediated between the period 2014 and 2023.

Based on the criterion that the presence of pollution at concentrations higher than 25 mg.L−1 essentially indicated the presence of LNAPL, the sites were divided into two groups that were separately evaluated for NEC-IR and NEC-UV, resulting in a total of four datasets (Table 5).

Table 5.

Number of sites classified into individual categories based on pollution concentrations.

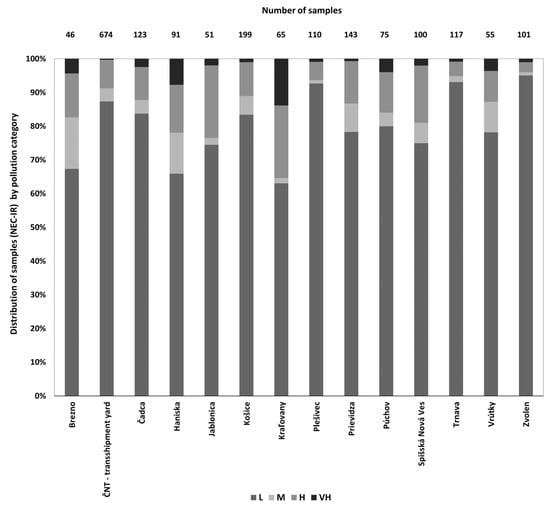

3.2.1. Sites with NEC-UV or NEC-IR Concentrations > 25 mg.L−1

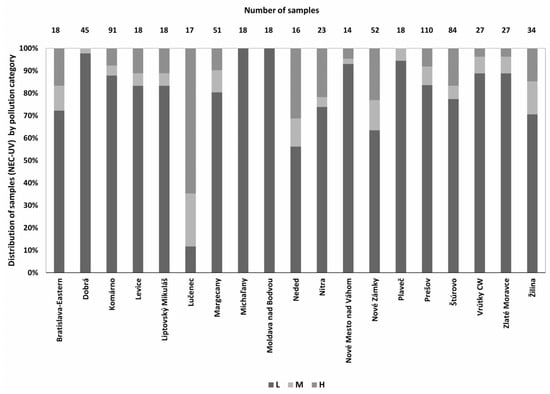

Figure 3 and Figure 4 show the results from sites that, based on groundwater sample analysis, were classified in the category indicating the presence of LNAPL (NEC-UV or NEC-IR > 25 mg.L−1). The number of sites with high and very-high levels of pollution for both monitored parameters is shown in Table 6. For the NEC-IR parameter, the highest degree of pollution was recorded in Kraľovany (36% of samples in the H and VH categories), while for the NEC-UV parameter, the highest pollution was observed in Kraľovany and Brezno (49% of samples in the H and VH categories). At the Kraľovany site, the smallest difference within a single site between the ratio of NEC-UV- and NEC-IR-polluted samples was observed. Pollution at the site is thus very serious, indicated by both the large number of polluted samples and the relatively small difference between the numbers of exceedances for the two parameters.

Figure 3.

Frequency of polluted samples (NEC-IR) at sites with LNAPL.

Figure 4.

Frequency of polluted samples (NEC-UV) at sites with LNAPL.

Table 6.

Number of sites with high and very-high levels of pollution.

The ČNT—Transshipment Yard site shows the highest number of evaluated groundwater samples (674 NEC-IR and 650 NEC-UV). The very-high pollution level at the site has been long-term (documented since the 1980s), and among all evaluated sites, was also the most spatially extensive (the area with the occurrence of LNAPL covers more than 5 ha). For the NEC-IR parameter, approximately 8% of samples were classified as heavily polluted (H and VH categories), while for the NEC-UV parameter, about 24% of the samples were in this category.

It is evident that, in terms of the NEC-UV parameter, the sites appear to be highly polluted, with 30.6% of the samples showing concentrations higher than the IT value, compared to 14.7% for the NEC-IR parameter.

The differences are also clearly visible in Figure 3 and Figure 4 for individual sites (sites that appear in both figures). On average, the number of highly contaminated samples (H and VH categories) based on the NEC-UV parameter was approximately two times higher than number of highly contaminated samples based on NEC-IR. At the Zvolen and Trnava sites, the number of highly contaminated samples for the NEC-UV parameter was more than five times higher than for NEC-IR. Therefore, based on the presented results, pollution at the Zvolen and Trnava sites appeared to be significantly overestimated when assessed using the NEC-UV parameter.

An interesting fact is that some sites where the presence of LNAPL was identified did not appear on the list of highly contaminated localities based on the more representative parameter, NEC-IR. This includes not only smaller sites (Komárno and Maťovce), but also larger ones (Čierna nad Tisou, Humenné, Leopoldov, Nitra, Prešov, Štúrovo and Trenčianska Teplá) as well as the largest one (Nové Zámky). At the same time, some sites without LNAPL occurrence were also identified as heavily polluted (Košice, Púchov and Spišská Nová Ves). The first finding indicates that, despite several wells where LNAPL was present (Štúrovo and Čierna nad Tisou), dissolved petroleum hydrocarbons did not spread significantly or their concentrations were low. Naturally, the results were affected by several uncertainties, the most important being the number and location of monitoring wells. The wells were situated to identify the presumed pollution sources; however, due to their limited number, the entire contaminated area might not have been fully covered by groundwater samples, or the samples might not accurately reflect the true extent of contamination at the site. In the case of the Prievidza site, the overestimation of the total pollution rate was caused by an accident in 2009, during which approximately 14,000 L of diesel were released. One of the consequences of the accident was the high number of wells with LNAPL occurrence (up to 20 wells in 2010).

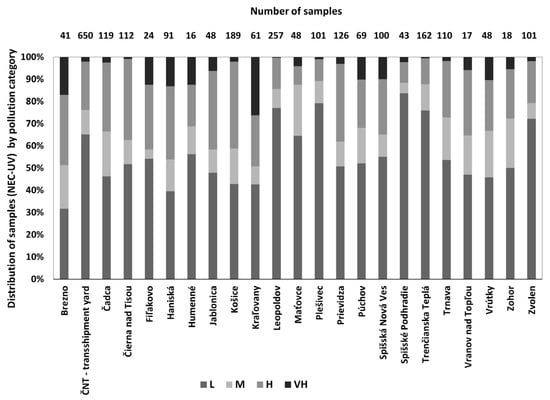

3.2.2. Sites with NEC-UV or NEC-IR Concentrations < 25 mg.L−1

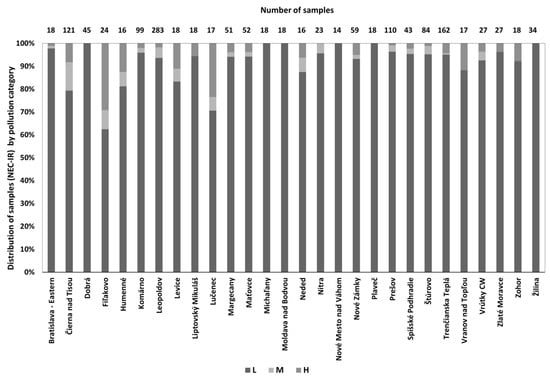

The number of sites with different pollution levels for both monitored parameters is presented in Table 7. For the NEC-IR parameter (Figure 5) the highest pollution degree was observed in Fiľakovo (high pollution in 29% of samples); for the NEC-UV parameter (Figure 6), it was Lučenec (high pollution in 65% of samples).

Table 7.

Number of sites by selected pollution levels.

Figure 5.

Frequency of polluted samples (NEC-IR) at sites without LNAPL.

Figure 6.

Frequency of polluted samples (NEC-UV) at sites without LNAPL.

Also, in this group of sites, the number of above-limit concentrations for the NEC-UV parameter significantly surpasses that for the NEC-IR parameter, by almost 2.5 times. High concentrations of NEC-UV were identified at several sites, which were classified as category A in the first stage of the project, and at which the pollution with the NEC-IR parameter was found to be very low (all detected concentrations were lower than the ID value), or only a few concentrations were found to exceed the ID (0.5 mg.L−1) but remained below the IT value (1 mg.L−1). The degree of pollution was higher at all these sites for the NEC-UV parameter (as also observed in the group of sites with NEC concentrations higher than 25 mg.L−1). The assessment of pollution based on the NEC-UV parameter is therefore questionable. The number of samples with high pollution (NEC-UV ≥ 1 mg.L−1) greatly exceeded the number of samples with high pollution for the NEC-IR parameter (790 vs. 291 samples).

As noted above, the groundwater samples evaluated did not include wells where LNAPL was present during monitoring. This was most evident at the Štúrovo site. None of the groundwater samples (36 samples collected) showed pollution concentrations exceeding 25 mg.L−1; for the NEC-IR parameter only 1% of the samples had concentration higher than 1 mg.L−1 and for the NEC-UV parameter, this was 17%). The mean values were also low (NEC-IR 0.11 mg.L−1; NEC-UV 0.71 mg.L−1), as were the medians (NEC-IR 0.06 mg.L−1; NEC-UV 0.21 mg.L−1), which may give the impression of low levels of pollution. However, during the evaluation period, the wells where LNAPL was present were not sampled, representing a total of 29 omitted groundwater samples. The site was remediated in 2018–2021 due to the high level of pollution [29]. The success of the remediation was confirmed by post-remediation monitoring [30]. Štúrovo was the site where the largest volume of LNAPL was removed (6.5 m3) among 14 sites remediated in that period.

3.2.3. Effect of Site Size (A, B, C, and D) on Groundwater Pollution (NEC-IR/NEC-UV)

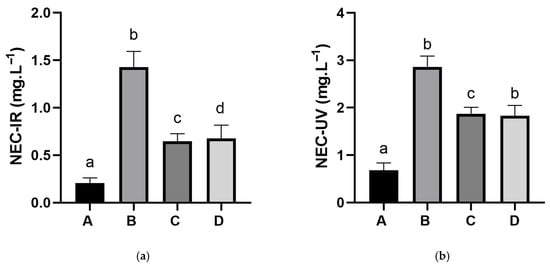

The effect of site size on groundwater pollution is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The mean NEC-IR (a) and NEC-UV (b) values; the error bars represent the standard error of the mean, and statistically significant differences at p < 0.05 or lower between site categories are shown by different lowercase letters.

For the NEC-IR parameter, the most statistically significant differences at p < 0.0001 were found between sites A and B, A and C, A and D, and C and D. For the NEC-UV parameter, the most statistically significant differences at p < 0.0001 were found between sites A and B, A and C, A and D.

The lowest mean concentrations of both NEC-IR and NEC-UV were found in samples from the smallest sites. In category A, NEC-IR concentrations were below 0.5 mg.L−1, indicating that no remediation is required at these sites. Sites classified in categories C and D, representing large and very large sites, respectively, exhibited moderate levels of contamination (ranging from 0.5 to 1 mg.L−1), requiring groundwater quality monitoring. The highest concentrations (more than 1 mg.L−1) were identified at category B sites, indicating the need for further geological work (survey and remediation).

The highest average concentrations observed in category B might be related to the fact that this category included the largest number of sites and also the highest number of samples with concentrations exceeding 25 mg.L−1 for both NEC-IR (23 samples) and NEC-UV (50 samples). In addition, at category B sites, underground storage tanks with a capacity of up to 100 m3 were mainly installed for diesel storage. At larger sites, above-ground storage tanks with a capacity of thousands of m3 were used for storage. Maintenance and leak detection from underground storage tanks was more complex than from above-ground storage tanks in the past. Given their limited lifespan, it is highly likely that they were the main reason for frequent pollution in category B sites. For the NEC-UV parameter, the concentrations in category A were higher than 0.5 mg.L−1, indicating that these sites need to be monitored. The need for further activities (geological surveys, for example) to refine the nature of pollution was identified in the remaining three categories, B, C and D.

Despite the differences among the evaluated datasets, it can be concluded that the size of the railway site has a significant impact on groundwater quality. All sites that included a maintenance and repair hall showed moderate to high levels of pollution for both parameters.

3.2.4. Impact of Site Activity Status on Groundwater Pollution (NEC-IR/NEC-UV)

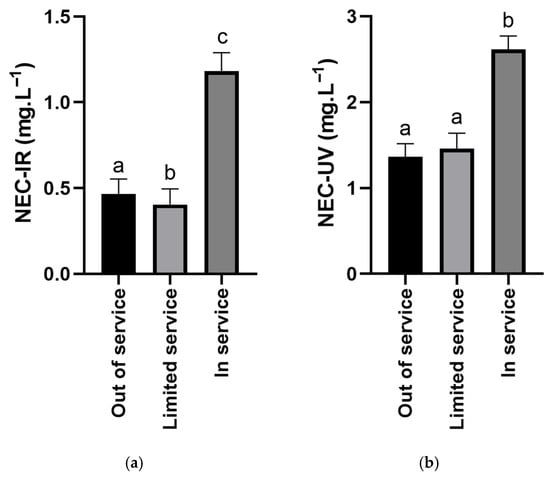

The effect of activity at the site on groundwater pollution is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

The mean NEC-IR (a) and NEC-UV (b) values; the error bars represent the standard error of the mean, and statistically significant differences at p < 0.05 or below between site categories are shown by different lowercase letters.

For the NEC-IR parameter, statistically, the most significant differences at p < 0.0001 were found between sites out of service and sites in service, and between limited-service (fuel station only) sites and sites in service. For the NEC-UV parameter, the most statistically significant differences at p < 0.0001 were found between sites out of service and sites in service and between limited-service sites and sites in service.

For both parameters, it was evident that sites in service exhibited significantly higher levels of pollution compared to sites out of service or limited-service sites. For the NEC-IR parameter, this difference was more pronounced than for NEC-UV. The NEC-IR concentrations at the sites out of service and those used only for fueling purposes were below 0.5 mg.L−1 and did not require remediation. The results also indicated that fuel stations do not contribute to increased NEC concentrations in groundwater. In fact, for the NEC-IR parameter, the concentrations of petroleum hydrocarbons at the limited-service sites were statistically significantly lower (p < 0.01) than at sites out of service. Sites in service showed pollution concentrations higher than 1 mg.L−1, indicating a high level of pollution and the need for further investigation and remediation. For the NEC-UV parameter, concentrations in all three categories exceeded 1 mg.L−1, representing high pollution levels that require appropriate follow-up measures.

4. Discussion

A comprehensive evaluation of railway sites based on the above-defined parameters (pollution concentration and size of site) is currently not addressed in the available scientific literature. Several papers focus on large-scale spills of hazardous substances in locomotive depots and transshipment stations, as well as proposals for remediation measures, but most of them are site-specific. Pennington et al. reported severe contamination of the rock environment and groundwater and subsequent removal of nearly 45 m3 of LNAPL by various types of remediation methods [31]. Mitton and Pimblett described a high degree of pollution at a former locomotive depot and the removal of over 98 m3 of LNAPL [32]. Groundwater monitoring on a long-term abandoned railway site revealed elevated concentrations of naphthalene and low concentrations of benzene and 1,2-diboromethane [33]. Lee and Lee identified a high degree of petroleum hydrocarbon pollution in the rock environment (mainly at a depth of 0.0–3.0 m below the ground surface) around a railroad station with a 100-year history, while no petroleum hydrocarbon pollution was detected in the groundwater [34]. Several railway sites are included in US EPA monitoring, such as the post-remediation monitoring of chlorinated hydrocarbons at a large, 2000 ha rail terminal [35]. While individual cases pose major environmental protection challenges, a comprehensive comparison and assessment of existing pollution across multiple railway sites is lacking. Theoretical analysis of the risks of soil and groundwater pollution from railway transport has been addressed by Anand and Barkan [36]. Monitoring of railway sites is a standard component of national environmental programs [37,38,39].

The assessment of the degree of pollution was carried out on the basis of pollutant concentrations. More accurate data on the condition of the site can be obtained by quantifying the intensity of the source—by calculating the amount of pollutant in flowing groundwater per unit of time [27,40,41]. The literature provides several examples of mass flux determination to assess the degree of pollution and its development at individual sites. Mass fluxes were evaluated to assess monitored natural attenuation on a petroleum-polluted site. Laboratory bench-scale experiments and field data were used to identify soil-to-groundwater pollution transfer. Results demonstrated decreasing TPH concentrations and reducing contaminant plumes [42]. The use of mass flow rates obtained through integral pumping tests to assess natural attenuation seems to be appropriate in cases where the monitoring of the well network is insufficient. The method was shown to be more accurate for contaminant plumes than for data obtained from point-scale measurements [43]. Another paper evaluated differences in organic contamination in five sewage treatment plants based on mass flux [44].

For the evaluated sites, the spatial extent to which pollution spread outside the site and its relative intensity were not processed for several reasons. The first is the significant differences between individual sites (characteristics of the geological environment—porosity, hydraulic conductivity, number and location of monitoring wells and unknown number and volume of leaks) and the limited availability of necessary data. The nature of the LNAPL (weathered diesel oil with dominant constituents in the range of C9–C20) corresponds to contamination plumes of a limited extent. The solubility of even fresh diesel is low compared to gasoline (8 mg.L−1 compared to 150 mg.L−1) [45]. The influx of fresh pollution into the rock environment on sites in full/limited service is significantly lower for the current state of technological equipment than before 1990, and pollution plumes in the form of LNAPLs are likely to be stable given their age [46]. The presence of highly soluble monoaromatic hydrocarbons (BTEX), which pose the greatest problem in terms of risk and spread through groundwater, is unlikely [45,47,48]. In diesel fuel, BTEX are present only in small quantities [49].

The highest levels of groundwater contamination were identified at the Brezno, Kraľovany and ČNT—Transshipment Yard sites. These sites differ not only in terms of size, but also in terms of their hydrogeological properties. Brezno is located directly on the Hron River (approx. 50 m); Kraľovany is approx. 500 m from the Váh river, while there is no significant stream near ČNT—Transshipment Yard. The aquifer at the ČNT site consists of Quaternary sands with varying degrees of silting and fine gravel content. The average thickness of the aquifer is 7.0 m, and the groundwater level does not have a clearly defined slope and therefore no clear direction of groundwater flow. Hydraulic conductivity is approximately 4.8 × 10−4 m.s−1. The main groundwater aquifer at the Brezno site consists of Quaternary fluvial gravel deposits with a thickness of 2.5–3.5 m. The groundwater is in direct hydraulic connection with the Hron River (approx. 50 m from the site). Hydraulic conductivity ranges from 1.13 × 10−5 to 4.08 × 10−5 m.s−1. At the Kraľovany site, the aquifer consists of Quaternary sediments—clayey gravels or gravels mixed with redeposited deluvial sediments. The thickness of the gravel layer is approx. 5–6 m, and the hydraulic conductivity is approximately 8.74 × 10−6 m.s−1. Identifying the main direction of pollution spread is problematic at the above-mentioned sites. The direction of groundwater flow changes significantly over time—when the water level rises, groundwater flows away from the river; when the water level in the Hron River falls, groundwater is drained towards the river. This means that the dispersed pollution spreads in different directions. The leakage of contamination from primary sources created secondary sources of pollution, which released dissolved petroleum hydrocarbons even after the primary sources were removed. Monitoring wells are located mainly near the original sources of pollution and were used to identify leaks. The primary sources of pollution in Brezno and Kraľovany were underground oil tanks with related technological equipment (handling areas for filling and dispensing and product pipelines). There were several workplaces at the ČNT—Transshipment Yard site that were sources of pollution—transshipment and pumping stations for mineral oils, benzene, xylene, ethylbenzene, ethyl acetate, vinyl acetate and methanol. Massive leaks of hazardous substances occurred mainly in the past (the primary sources of pollution at the sites have been removed or were no longer in intensive use during the period under review), with the contaminated pore environment acting as a secondary source of pollution. Given the previous contamination of the rock environment and groundwater, it is now difficult to determine whether the currently operated facilities are active sources of contamination. High concentrations of pollution were observed mainly in wells located near the primary sources of pollution.

High percentage of polluted railway sites can be attributed to the fact that these are historic sites where underground single-walled storage tanks were used in the past, and where containment measures during handling and in the event of spills or accidents were generally of low effectiveness. The spread of pollution from the source is influenced by several factors, the most important of which are the properties of the rock environment (permeability and depth of the water table) and the properties of the pollutant (solubility and viscosity). The migration of hazardous substances in dissolved form to greater distances from the source is influenced by the direction and velocity of groundwater flow, the sorption capacity and the rate of degradation processes. These factors, along with others that cannot be precisely determined across the entire study area, introduce a degree of uncertainty into the obtained results.

The pollution load at numerous investigated sites remained high despite ongoing natural attenuation [50,51]. In 2018, remediation work began at 14 sites. The first step was a pre-remediation survey to confirm the presence of environmental or health hazards. The presence of LNAPL was verified at 12 sites, and concentrations of petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH and NEC-IR) higher than the regulatory criteria were found at two sites. The risk assessment of the contaminated site confirmed the need for remediation work at all sites, which took place between 2019 and 2023. The main remediation method was pump and treat, with additional in situ methods (biodegradation, washing and air sparging, etc.) used to increase efficiency. The volume of extracted LNAPL ranged from 0.1 to 6.5 m3. The effectiveness of the remediation work was subsequently verified by post-remediation monitoring of the sites, which is still ongoing.

The following text provides a brief description of the results of remediation work at two railway sites. Both sites were part of a set of 14 remediated sites. Large volumes of free product were removed from both sites, but there was no evidence of contamination spreading in dissolved form through groundwater to the surrounding areas. Dissolved hydrocarbon and LNAPL plumes were stable at both sites.

Large-scale contamination was identified at the abandoned Štúrovo railway site. LNAPL was identified in 31 wells on an area of approximately 3400 m2 and was removed by dual-phase pumping. The hydraulic conductivity was low, on average 9.45 × 10−4 m.s−1. Only trace concentrations of dissolved contamination (NEC-IR and TPH) were identified in groundwater samples from wells located approximately 15 m from the LNAPL plume. During remediation, the stability of not only the LNAPL plume but also of dissolved contamination was confirmed. In addition to TPH, concentrations of BTEX, CAHs and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) were also monitored. The concentrations of individual pollutants from the above-mentioned groups were below the detection limit of the analytical method in the vast majority of samples; no exceedances of legislative criteria were recorded. LNAPL was identified not only in the vicinity of hotspots (underground tanks, service pits and fuel-dispensing points), but also in the area of the railway track in front of the former roundhouse. An interesting sample of free product was also found, which, despite being at least 10 years old, showed no signs of weathering, with an n-alkane content comparable to that of fresh diesel fuel. More than 6.5 m3 of LNAPL was removed [29].

Two sources of contamination were identified at the Leopoldov site—an oil storage facility and above-ground fuel tanks. Remediation work focused on removing contamination around the above-ground tanks, where LNAPL was identified in seven wells over an area of approximately 1000 m2. It was removed by dual-phase pumping from wells and skimming from an excavation. Laboratory analyses determined the LNAPL as weathered diesel. Longer-chain hydrocarbons (C16–C35) dominated, accounting for up to 75% of the sample content. In addition to petroleum substances, concentrations of BTEX, CAHs, polychlorinated biphenyls and PAHs were also monitored. The concentrations of individual pollutants from the above groups were below the detection limit of the analytical method in the vast majority of samples and no exceedances of legislative criteria were recorded. The hydraulic conductivity was high, ranging from 1.4 × 10−3 to 2.5 × 10−2 m.s−1. Despite the high conductivity, the concentrations of contamination in the groundwater samples taken were low. More than 5.8 m3 of free product was removed [52].

The presented results document the significant impact of railway sites on groundwater quality in technical infrastructure areas in settlements. In most of the evaluated sites, free product was present as a dominant risk factor for groundwater quality, in others, pollution with petroleum hydrocarbons was identified in dissolved form. The presence of pollution is in most cases of a historical nature, but leaks of hazardous substances sporadically occur at this type of site even today.

The intensity of pollution naturally decreases over time, as proven by several publications evaluating natural attenuation processes. However, its positive impact will only be relevant if there is no new pollution input into the environment. The primary prerequisite for achieving this state is regular training of site workers, which will lead to a change in work habits. Many railway employees have been in their positions for decades, with their approach to work and particularly to handling hazardous substances being shaped back in the 1980s and 1990s. The second measure is to build a high-quality monitoring network that will enable the rapid identification of leaks of hazardous substances. The wells should be located mainly in the vicinity of potential sources of pollution (UST, warehouses, handling areas and dispensing points) and to a lesser extent, outside them. In large active operations, only a small number of wells are often used for monitoring, which is insufficient in terms of identifying pollution.

5. Conclusions

The outcome of the pilot project for the comprehensive survey of railway sites in the Slovak Republic, followed by monitoring of groundwater quality, was an assessment of the presence and extent of groundwater pollution. In total, the presence of pollution was assessed at 42 sites. Due to the high number of samples in which contamination was identified, the results of the groundwater quality monitoring are considered reliable—at least with respect to the NEC-IR parameter.

The results show that railway sites are characterized by a high degree of pollution. Based on the NEC-IR parameter, 14 sites were very heavily polluted, while NEC-UV indicated severe pollution at 23 sites. NEC-IR concentrations were significantly (up to an order of magnitude) lower than NEC-UV concentrations. Statistical analysis of site groups, classified on the basis of their size and activity, confirmed that both the size of the site itself and the maintenance and repair activities positively correlated with the occurrence and concentration of pollution. In a significant number of samples, exceedances of the regulatory limits were recorded only for the parameter NEC-UV. NEC-UV concentrations identified in groundwater samples are often not consistent with the results of NEC-IR analyses. This is confirmed by hundreds of parallel analyses performed during remediation at the Štúrovo and Leopoldov sites [29,43].

The long-term handling of petroleum products at the sites, coupled with the low level of technical equipment used in the past, has resulted in persistent and severe groundwater contamination. Technical measures to prevent unwanted leakages are currently at a sufficient level (for example, the use of double-walled storage tanks). To date, most of these sites are out of service, but this does not mean that they do not represent sites at risk. High levels of pollution, confirmed by the presence of LNAPLs, were identified at 21 of the 45 sites examined during the initial investigation conducted between 2008 and 2014.

The results of the statistical tests can be summarized as follows. The selected datasets showed similar trends for both parameters: pollution concentrations are lower at sites out of service compared to active ones, and likewise lower at small sites compared to large ones. However, concentrations measured using the NEC-UV parameter were significantly higher overall. From a regulatory point of view, six of the seven sets of sites would require further work to be carried out to obtain more information on the nature of the pollution. All except the small sites without a maintenance hall achieved pollution concentrations higher than 1 mg.L−1. For the NEC-IR parameter, the highest average concentrations were observed in site size category B, reaching nearly 1.5 mg.L−1. The same category also exhibited the highest concentrations in the NEC-UV parameter, with values approaching 3.0 mg.L−1.

Groundwater sample analyses have raised concerns regarding reliability of the NEC-UV parameter. The values of the parameter exceeded the regulatory limits even at sites where no pollution was recorded by the NEC-IR parameter. However, from a legal standpoint, such sites must still be subject to monitoring due to the detected concentrations. The use of the NEC-UV parameter for the detection of dissolved petroleum products (diesel and engine oils) appears to be inappropriate. The elevated NEC-UV concentrations are not only unreliable but also serve as the basis for remediation measures, raising questions about the cost-effectiveness of expenditures related to such activities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.; validation, Ľ.J.; formal analysis, V.Š.; resources, J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.; writing—review and editing, V.Š. and Ľ.J.; visualization, V.Š. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Access to the data is subject to approval and a data sharing agreement due to the commercial reasons of The Centre of Environmental Services, Ltd.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Juraj Macek was employed by the company The Centre of Environmental Services, Ltd., Kutlíkova 17, 852 50 Bratislava, Slovak Republic. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Kubáček, J.; Doubek, M.; Školník, M.; Klubal, M.; Kattoš, M.; Szojka, L.; Pravda, P.; Kinček, J.; Farkaš, G.; Menger, J.; et al. Dejiny Železníc na Území Slovenska; Železnice SR: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1999; ISBN 80-968140-4-4. [Google Scholar]

- Šefčík, M. História, súčasnosť a budúcnosť elektrifikácie železničných tratí na Slovensku. VTS News 2016, 4, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Macek, J.; Milička, J. Light Non-Aqueous Phase Liquids Distribution and Weathering in Former Railyard; SE Danube Basin, Slovakia. Acta Geol. Slovaca 2021, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wiłkomirski, B.; Sudnik-Wójcikowska, B.; Galera, H.; Wierzbicka, M.; Malawska, M. Railway Transportation as a Serious Source of Organic and Inorganic Pollution. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2011, 218, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiłkomirski, B.; Galera, H.; Sudnik-Wójcikowska, B.; Staszewski, T.; Suska-Malawska, M. Railway Tracks-Habitat Conditions, Contamination, Floristic Settlement—A Review. Environ. Nat. Resour. Res. 2012, 2, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, L.; Aleksic, G.; Radosavljevic, M.; Onjia, A. Soil Pollution in the Railway Junction Niš (Serbia) and Possibility of Bioremediation of Hydrocarbon-Contaminated Soil; European Geosciences Union: Vienna, Austria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Samešová, D.; Ladomerský, J. Výskyt a Stanovenie Ropných Látok v Povrchových Vodách. Životné Prostr. 2006, 40, 84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester, S.; Janik, L.; McLaughlin, M. An Infrared Spectroscopic Test for Total Petroleum Hydrocarbon (TPH) Contamination in Soils. In Proceedings of the 19th World Congress of Soil Science: Soil Solutions for a Changing World, Brisbane, Australia, 1–6 August 2010; pp. 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, W.; Malone, B.P.; Minasny, B. Rapid Assessment of Petroleum-Contaminated Soils with Infrared Spectroscopy. Geoderma 2017, 289, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Lamb, D.; Naidu, R. The Application of Rapid Handheld FTIR Petroleum Hydrocarbon-Contaminant Measurement with Transport Models for Site Assessment: A Case Study. Geoderma 2020, 361, 114017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Naidu, R.; Bowman, M. The Key Factors for the Fate and Transport of Petroleum Hydrocarbons in Soil With Related In/Ex Situ Measurement Methods: An Overview. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 756404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramoğlu Karşı, M. Investigation of Oil and Grease in Surface Soils of Gas Station, Automobile Repair Workshop, Urban, Recreational Area, and Rural Sites Using FT-IR. Accredit. Qual. Assur. 2024, 30, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, C.; Silvério, S.; Silva, C.; Paulino, A.; Nascimento, S.; Revez, C. Optimization and Validation of FTIR Method with Tetrachloroethylene for Determination of Oils and Grease in Water Matrices. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2013, 24, 1403–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simion, A.F.; Găman, A.N.; Lăutaru, V.A. Analysis of Total Content of Petroleum Products in Water by Using FTIR Spectroscopy. MATEC Web Conf. 2022, 373, 00063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, T.R. Chapter 1—Hydrocarbons in Nonsaline Waters. In Determination of Toxic Organic Chemicals in Natural Waters, Sediments and Soils; Crompton, T.R., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 1–34. ISBN 978-0-12-815856-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zemo, D.A. White Paper: Analytical Methods for Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons (TPH); Zemo & Associates, Inc.: Incline Village, NV, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Okparanma, R.N.; Mouazen, A.M. Determination of Total Petroleum Hydrocarbon (TPH) and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon (PAH) in Soils: A Review of Spectroscopic and Nonspectroscopic Techniques. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2013, 48, 458–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, O.; Thomas, M.-F. Chapter 12—Industrial Wastewater. In UV-Visible Spectrophotometry of Waters and Soils, 3rd ed.; Thomas, O., Burgess, C., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 385–416. ISBN 978-0-323-90994-5. [Google Scholar]

- Vrana, K.; Fatulová, E.; Naštický, J. Vypracovanie Programov Opatrení v Rámci Prípravy Plánov Manažmentu Oblastí Povodí v Súlade s Požiadavkami Vodného Zákona a Rámcovej Smernice o Vode Pre Prevádzky ZSSK CARGO a.s.–I. Etapa Prác a Lokalitu Čierna nad Tisou–Prekladisko; Life and Waste, s.r.o., HYDEKO-KV: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2008; p. 135. [Google Scholar]

- Vrana, K.; Fatulová, E.; Naštický, J.; Kovács, T. Vypracovanie Programov Opatrení v Rámci Prípravy Plánov Manažmentu Oblastí Povodí v Súlade s Požiadavkami Vodného Zákona a Rámcovej Smernice o Vode Pre Prevádzky ZSSK CARGO a.s.-II. Etapa Prác a Lokalitu Čierna nad Tisou-Prekladisko; Centrum environmentálnych služieb, s.r.o.: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2008; p. 95. [Google Scholar]

- Auxt, A.; Hronec, B. Monitoring Podzemných vôd v Prevádzkach ZSSK Cargo Slovakia a.s. za rok 2009; Centrum Environmentálnych Služieb, s.r.o.: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2010; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Auxt, A.; Hronec, B. Monitoring Podzemných vôd v Prevádzkach ZSSK Cargo Slovakia a.s. za rok 2010; Centrum Environmentálnych Služieb, s.r.o.: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2011; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Auxt, A.; Hronec, B. Monitoring Podzemných vôd v Prevádzkach ZSSK Cargo Slovakia a.s. za rok 2011; Centrum Environmentálnych Služieb, s.r.o.: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2012; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Auxt, A.; Hronec, B.; Fecková, B. Monitoring Podzemných vôd v Prevádzkach ZSSK Cargo Slovakia a.s. za rok 2012; Centrum Environmentálnych Služieb, s.r.o.: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2013; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Auxt, A.; Hronec, B.; Polčan, I. Monitoring Podzemných vôd v Prevádzkach ZSSK Cargo Slovakia a.s. za rok 2013; Centrum Environmentálnych Služieb, s.r.o.: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2014; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Polčan, I. Hodnotiaca Správa z Priebehu Vývoja Znečistenia Za Obdobie Jún 2009–Marec 2014. In Rušňové Depo Čadca, Čierna Nad Tisou, Haniska, Jablonica, Komárno, Leopoldov, Maťovce, Plešivec, Prešov, Púchov, Spišská Nová Ves, Štúrovo, Trenšianska Teplá a Čierna Nad Tisou–VSP; Centrum Environmentálnych Služieb, s.r.o.: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- ITRC. Use and Measurement of Mass Flux and Mass Discharge; ITRC: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli, F.; Durnford, D.S. LNAPL Thickness in Monitoring Wells Considering Hysteresis and Entrapment. Groundwater 1996, 34, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, O.; Chovanec, J.; Keklák, V.; Gregor, T.; Kolářová, J.; Vybíral, V.; Škarvan, A.; Čopan, J.; Drábik, A.; Macek, J.; et al. Sanácia Environmentálnej Záťaže NZ (029)/Štúrovo-Rušňové Depo, Cargo a.s. (SK/EZ/NZ/601); DEKONTA Slovensko, spol. s r. o., DEKONTA, a. s.: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2021; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, O.; Chovanec, J.; Keklák, V.; Gregor, T.; Kolářová, J.; Vybíral, V.; Škarvan, A.; Čopan, J.; Drábik, A.; Macek, J.; et al. Sanácia Environmentálnej Záťaže NZ (029)/Štúrovo-Rušňové Depo, Cargo a.s. (SK/EZ/NZ/601); DEKONTA Slovensko, spol. s r. o., DEKONTA, a. s.: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2023; p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, A.; Coughlin, J.; Thomas, L.; Gabardi, D. LNAPL Recovery and Remedy Transitions: A Case Study at a Railyard Fueling Facility. In Proceedings of the Chlorinated Conference Proceedings, Palm Springs, CA, USA, 8 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mitton, M.J.; Pimblett, B. In-Situ Biological Percolating System for the Treatment of Hydrocarbon Impacted Groundwater; Environmental Services Association of Alberta: Banff, AB, Canada, 2005; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- INTERA. Additional Groundwater Characterization Report. City of Albuquerque Rail Yards; INTERA: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2017; p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Lee, Y. Investigation of Soil and Groundwater Contaminated by Gasoline and Lubricants Around a Railroad Station in S City, Korea. Korea Sci. 2012, 38, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US EPA. Sixth Five-Year Review Report for Conrail Rail Yard (Elkhart) Superfund Site; US EPA: Chicago, IL, USA, 2024; p. 74. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, P.; Barkan, C. Exposure of Soil and Groundwater to Spills of Hazardous Materials Transported by Rail: A Geographic Information System Analysis. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2006, 1943, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordík, J.; Slaninka, I.; Bačová, N.; Bahnová, N.; Benková, K.; Bodiš, D.; Bottlik, F.; Dananaj, I.; Demko, R.; Dénes, D.; et al. Udržateľnosť Projektu “Monitorovanie Environmentálnych Záťaží Na Vybraných Lokalitách Slovenskej Republiky”; Štátny Geologický Ústav Dionýza Štúra: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2020; p. 112. [Google Scholar]

- WVDEP. West Virginia Voluntary Remediation Program; West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection: Charleston, WV, USA, 2023; p. 383. [Google Scholar]

- TGCP. Joint Groundwater Monitoring and Contamination Report-2023; Texas Groundwater Protection Committee: Austin, TX, USA, 2024; p. 298. [Google Scholar]

- Goltz, M.N.; Kim, S.-J.; Yoon, H.; Park, J.-B. Review of Groundwater Contaminant Mass Flux Measurement. Environ. Eng. Res. 2007, 12, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CRC CARE. Flux-Based Groundwater Assessment and Management; Technical Report series; CRC for Contamination Assessment and Remediation of the Environment: Adelaide, Australia, 2016; p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y.; Wang, B.; Yang, Y.; Du, X.; Yang, M. Quantitative Assessment of Organic Mass Fluxes and Natural Attenuation Processes in a Petroleum-Contaminated Subsurface Environment. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietze, M.; Dietrich, P. A Field Comparison of BTEX Mass Flow Rates Based on Integral Pumping Tests and Point Scale Measurements. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2011, 122, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, K.M.; Haglund, P.; Gao, Q.; Ahrens, L.; Gros, M.; Wiberg, K.; Andersson, P.L. Mass Fluxes per Capita of Organic Contaminants from On-Site Sewage Treatment Facilities. Chemosphere 2018, 201, 864–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, E.R. Applications of Environmental Aquatic Chemistry: A Practical Guide, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-429-10687-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, D.W.; Grose, R.D.; Michaelsen, J.C.; MacQueen, D.H.; Cullen, S.J.; Kastenberg, W.E.; Everett, L.G.; Marino, M.A. California Leaking Underground Fuel Tank (LUFT) Historical Case Analyses; Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Environmental Protection Department, Environmental Restoration Division: Livermore, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, S.; Roy, P. BTEX: A Serious Ground-Water Contaminant. Res. J. Environ. Sci. 2011, 5, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, C.; Connor, J. Characteristics of Dissolved Petroleum Hydrocarbon Plumes; American Petroleum Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mariano, A.P.; Bonotto, D.M.; de Franceschi de Angelis, D.; Pirôllo, M.P.S.; Contiero, J. Biodegradability of Commercial and Weathered Diesel Oils. Braz. J. Microbiol. Publ. Braz. Soc. Microbiol. 2008, 39, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Newell, C.J.; Kulkarni, P.R.; King, D.C.; Adamson, D.T.; Renno, M.I.; Sale, T. Overview of Natural Source Zone Depletion: Processes, Controlling Factors, and Composition Change. Groundw. Monit. Remediat. 2017, 37, 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sookhak Lari, K.; Davis, G.B.; Rayner, J.L.; Bastow, T.P.; Puzon, G.J. Natural Source Zone Depletion of LNAPL: A Critical Review Supporting Modelling Approaches. Water Res. 2019, 157, 630–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tupý, P.; Schwarz, J.; Antal, J.; Masiar, R.; Filo, J.; Jasovský, Z.; Moravčík, D.; Fickuliaková, M.; Drábik, A.; Macek, J.; et al. Sanácia Environmentálnej Záťaže HC (1844)/Leopoldov-Rušňové Depo, Cargo a.s. (SK/EZ/HC/1844); EBA, s.r.o., ODOS, s.r.o., ENVIGEO, a.s.: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2022; p. 134. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).