Abstract

Control of reactive species generation lies at the core of atmospheric pressure plasma processing. In this work, we investigate the ability of a cold RF argon plasma jet source to produce reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) following the injection of a molecular gas (N2 or O2), either premixed with the main gas (Ar) or introduced separately into an already generated Ar discharge. We show that, when reactive gases are injected directly into the Ar discharge, the range of operating parameters—particularly the ratio of reactive gas to main gas—is considerably widened compared to conventional injections through the main argon flow. The plasma characteristics at the source exit were analyzed using optical emission spectroscopy (OES), including the determination of electron density, rotational temperature, and the emission intensities of plasma species such as Ar I, NO(A), OH(A), and N2(C) for both injection types. Overall, the results show that plasmas generated using in-discharge injection are more stable and capable of sustaining enhanced production of reactive radicals such as NO(A) and OH(A), whereas injection through the main gas can be tuned to selectively enhance NO generation. These findings highlight the potential of plasma sources employing premixed or in-discharge reactive gas injection for surface treatment and for the processing of gas and liquid phases.

1. Introduction

While many applications use the thermal effects of plasmas operating at atmospheric pressure (such as plasma welding [1], melting [2], cutting [3], and so on), cold plasma processing is based on chemical effects sustained by the interaction of reactive species existing in plasma (or generated by plasma) with materials [4]. Cold atmospheric pressure plasma sources remain at the forefront of research due to their advantages in processing various materials in solid, liquid, and gas phases [5].

The nature and quantity of reactive species are key elements in processing activities. There are numerous reactive species with remarkable roles in different applications; among them, the most well-known are OH [6], NH [7], NO [8,9,10], O [11,12], O3 [13], ions [14], and metastable species [15]. It is also important to mention that the identification and quantification of plasma-generated species rely on dedicated plasma diagnostics. Among these, optical emission spectroscopy (OES) is the most widely applied due to its non-invasive nature and the broad availability of the instrumentation used in this process. However, processing and interpreting spectral data require a high level of expertise. General information on the use of OES as a diagnostic tool for atmospheric pressure plasmas can be found in [16], while examples related to specific applications, such as food technology [17] or surface processing [18], illustrate its practical relevance across various plasma systems.

A major problem in modern high-power laser systems is the contamination of optics, with mirrors being particularly affected by carbonaceous deposits, which can lead to increased absorption, local heating, and degradation of their dielectric coating [19,20]. Therefore, the ability to remove the contaminated mirror surface without damaging the underlying coating is very important for maintaining optical performance for a long time. Traditional cleaning methods, such as mechanical polishing, may be too aggressive for sensitive optical coatings. In this context, the use of chemically reactive species, RONS, generated by cold atmospheric pressure plasmas jets represents an effective and controllable alternative for the removal of carbon contamination [9,10]. Atmospheric pressure plasma cleaning was also proposed as a support for the maintenance of walls and diagnostic mirrors in fusion technology [21]. These plasmas have also been investigated for liquid decontamination, demonstrating high efficiency, as reported in [22,23]. Also, plasma jets have been applied for the in-liquid functionalization of nanomaterials, like carbon nanowalls [24] and nanocellulose [25] dispersed in water, demonstrating their ability to introduce chemical modification through plasma–liquid interactions.

One of the technical problems in reactive species generation by atmospheric pressure plasma sources is related to gas injection procedures, where various constraints should be fulfilled simultaneously. Stationary atmospheric pressure cold plasmas are mostly generated in flowing atomic gases, such as He [26,27] and Ar [28]. These gases are suitable because they prevent the discharge from transitioning into a thermal arc regime. First, unlike molecular gases, discharges in atomic gases require less power, since rotational, vibrational, and dissociation processes are absent [29]. Second, they provide a cooling effect through efficient heat transfer from the electrodes, supported by fast gas flow and the high thermal conductivity of gases such as helium. Still, the creation of specific reactive species requires the presence of molecular gases such as oxygen, nitrogen, hydrocarbons, and fluorinated gases. Sometimes it is enough for gas molecules (O2, N2, H2O vapors) to be taken from the environment during plasma expansion [30]. In contrast, in those cases where such gases are undesirable, an inert gas curtain can be applied [30,31,32]. The injecting of molecular gas downstream of the discharge is also possible, but there are disadvantages: non-isotropic mixing and limited excitation transfer from the species carrying energy from the discharge (ions, metastable species, etc.).

The most desirable route would be the injection of the molecular gas in a controlled manner and into the discharge. The most common approach to this is admixing the reactive gas with the main inert gas that is sustaining the discharge. This approach is illustrated in Figure 1 (left). However, this may lead to plasma extinction, which can be prevented by increasing the applied power, thus raising the risk of a transition into an arc. The consequence of this is that only limited amounts of reactive gases can be added while keeping the discharge running and cool. For example, the ratio of reactive to main gas reported in the literature is generally quite low, depending on the plasma source and application. Typical values range between 1 and 2% O2 and/or N2 in sources using He as the main gas [12,33] and between 0.2 and 1.5% in sources using Ar as the main gas [34,35]. Increases in this ratio are in high demand for plasma processing technologies, especially in biomedical applications where RONS generation plays a significant role [36].

Figure 1.

Illustration of the I and Y plasma jet configurations, emphasizing the reactive gas injection peculiarities.

Herewith we present an atmospheric pressure DBD plasma jet source capable of operating in a cold regime with high concentrations of reactive molecular gases (N2 or O2), reaching as high as 50%. This is made possible by the injection of the reactive gas separately from the main inert gas, downstream of the active RF electrode and into the middle of the discharge channel. This approach is illustrated in Figure 1 (right). Accordingly, the discharge is sustained in the main atomic gas upstream of the injection point, allowing the discharge to be maintained even at high fractions of injected reactive gases. Based on the similarity of the injection geometries shown in Figure 1 to the capital letters “I” and “Y”, we hereafter refer to the respective plasma sources as I-DBD and Y-DBD. In contrast to previously reported plasma jet mixing configurations, the present Y-DBD configuration introduces the molecular gas through an oblique lateral channel, forming a Y-shaped junction. This geometry minimizes perturbations to the main flow and helps to maintain a stable, laminar gas flow. As a result, a progressive mixing region is established in which the molecular gas gradually diffuses toward the filamentary discharge. This gradual interaction significantly reduces collisional quenching of the plasma filament, allowing the discharge to remain stable over a substantially wider range of molecular gas fractions.

The design details of the two sources are provided in the experimental section of this study. In the results section, their operating domains in terms of power and gas flow rate are compared, highlighting the superiority of Y-DBD with respect to the working parameter ranges. Additionally, the emission intensity of the reactive species (NO, OH, and N2) and the plasma characteristics (electron density, rotational and vibrational temperatures) were analyzed as a function of the amount of molecular gas injected. This analysis was performed using OES, considering the spectra acquired near the tube exit. The results show that the behavior of the species is consistent with the main mechanisms governing their formation and excitation in atomic plasmas mixed with molecular gases. Based on these findings, we recommend operating conditions that optimize the production of NO and OH radicals.

2. Experimental Details and Methods

The schematic view of the experimental setup used for the plasma investigations is shown in Figure 2a. Two main parts can be identified, with one part being dedicated to plasma operation and control, while the other is dedicated to plasma investigations.

Figure 2.

(a) Experimental setup. This consists of the plasma generation and control system and the spectral investigation system. The pictured plasma source is of the Y-DBD type. (b) Detailed view of the geometry used for spectral data collection.

2.1. Plasma Generation and Control

The system for plasma generation and control consists of the plasma source and gas feeding arrangements (Figure 2). The sources used in this work are based on a single-electrode RF discharge, as described in the previous work by Teodorescu et al. [28]. The discharge is ignited in a glass tube with an outer diameter of 6 mm and an inner diameter of 4 mm, in flowing Ar gas, with one annular electrode placed on the tube at a distance of 6.5 cm from the tube exit. The grounded electrode is physically missing; its role is substituted by external bodies distributed in the space around the plasma source. We have shown that this configuration produces a stable, single-filament discharge surrounded by a diffuse plasma region; the filament develops inside the tube starting from the electrode position and extends outside the tube as a long (up to 5 cm), thin plasma jet. This configuration (denoted here as I-DBD) was changed into the Y-DBD, as detailed in Figure 1. In this modified configuration, the lateral injection branch is a fully integrated part of the glass structure, produced by joining two glass tubes to form a single Y-shaped device. The branch has the same inner and outer diameters as the main tube and is positioned at a 45° angle relative to the main tube, ensuring identical flow conditions in both channels and enabling a gradual mixing of the injected molecular gas in the filamentary discharge. We found that this modification did not affect the stable single-filament mode operation of the source. For both source types, the plasma is sustained at atmospheric pressure by a 13.56 MHz RF power supply (CESAR, Advanced Energy, Denver, CO, USA), operated in power-control mode, and an adequate matching box (ADTEC Plasma Technology Co., Ltd., Fukuoka, Japan). The matching box continuously adjusts the impedance to ensure that the power delivered to the discharge remains constant. During all measurements, the reflected power was continuously monitored and remained at zero, indicating stable and efficient power coupling throughout the entire range of molecular gas injection. The operation of the sources was investigated in the 30–220 W range, with the applied power limited to a maximum of 220 W to prevent source damage through excessive heating. For gas delivery, mass flow controllers (Bronkhorst High-Tech B.V., Ruurlo, The Netherlands) were used. Argon was used as the main gas, at a mass flow rate of 3000 sccm. Oxygen or nitrogen was used as the reactive gas, injected either into the main gas (I-DBD) or directly in the Ar discharge (Y-DBD), at mass flow values in the range of 0–1500 sccm. Based on the 4 mm inner diameter of the tube and the 3000 sccm main flow rate, the gas velocity inside the discharge tube is estimated to be approximately 4 m/s, corresponding to a residence time of ~11 ms between the injection point and the tube exit.

2.2. Plasma Investigation

Optical emission spectroscopy (OES) was selected as the primary diagnostic method because it is non-intrusive and well suited for atmospheric pressure plasma jets, where invasive electrical probes such as Langmuir probes cannot be implemented. OES provides direct access to key excited species relevant for RONS generation, particularly OH(A) and NO(A), enabling consistent comparison between the two injection configurations. Moreover, it is widely accessible, cost-effective, and easy to operate, making it attractive for monitoring and process control. Therefore, OES represents an appropriate and reliable technique for evaluating the plasma jets investigated in this work.

The spectral information was acquired using a 1000 mm focal length Jobin–Yvon Horiba FHR1000 (Horiba, Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) spectrometer with a 2400 grooves/mm grating, equipped with a cooled Andor iDus 420 CCD camera (Andor Technology Ltd., Belfast, UK). The spectrograph and CCD camera were controlled using the Solis for Imaging software, version 4.3.0.0 (Andor Technology Ltd., Belfast, UK). The plasma jet emission was collected through two converging lenses to control the magnification of the plasma image formed on the entrance slit of the spectrograph. The spectral resolution of the measurements, corresponding to the used slit width of 20 μm, was calculated as 0.02 nm. It is important to note that ambient humidity and air diffusion were not actively controlled in this study. However, all measurements were performed under laboratory air-conditioning conditions at the same room temperature to ensure consistent operation.

The repeatability and long-term stability of the emission intensity were first evaluated in a dedicated test, in which 10 spectra were recorded at 2 min intervals under identical operating conditions. The resulting emission intensities showed a relative variation of only 1.5%, demonstrating excellent temporal stability of the optical signal.

The electron number density was determined by analyzing the Stark broadening profile of lines within the Balmer series. Plasma being located in the immediate vicinity of an atom or ion can significantly modify its effective internal electric field. The electric microfields from the electrons and ions in the plasma alter the energy states of the emitter (the source of electromagnetic radiation) through the Stark effect. This effect leads to the broadening of spectral lines, as well as asymmetries and shifts in the line position. The analysis of spectral line profiles broadened by the Stark effect is a widely used method for plasma diagnostics [37]. The line profile strongly depends on the density of charged particles surrounding the radiation source. This dependency is particularly significant for hydrogen-like ions, where the Stark effect is linear [38]. The utilization of Stark broadening for determining electron density in plasma offers several advantages, including the simplicity of the method and its independence from local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE) conditions. Before estimating the electron density, it is necessary to separate the experimental line profile from the effects of instrumental and Doppler broadening. The resulting line profile is then compared to a theoretical Stark profile. Generally, the analysis involving the Stark broadening profile focuses on the maximum broadening of the spectral line at half of its height, often referred to as “full width at half maximum” (FWHM) in the specialized literature [39].

The instrumental contribution was subtracted from the measured FWHM using the standard deconvolution formula for a rectangular slit function. The spectral resolution of 0.02 nm was obtained using an entrance slit of 20 μm, using the standard dispersion relation:

where d is the groove spacing, m is the dispersion order (m = 1), f is the focal length of the spectrograph, and w is the effective slit width, given by the larger of the entrance and exit slits.

After subtracting the instrumental contribution, the remaining Lorentzian width was used to determine the electron density. The uncertainty associated with this deconvolution (accounting for both the repeatability of the spectral acquisition and the precision of the 0.02 nm instrumental width) is estimated to be ±10%.

As demonstrated in [40], the OH rotational temperature provides a reliable estimation of the gas temperature in plasma jets. In this work, the rotational temperature of the OH radical was evaluated by fitting the experimental spectrum of the OH(A–X) band with a synthetic spectrum generated based on the Boltzmann distribution of rotational levels, Honl–London factors, and a Gaussian function accounting for instrumental broadening [41]. This method takes into consideration the overlapping of N2 (SPS) emission with the OH bands and excludes their contribution. An example of such a simulated spectrum fitted to the experimental data is illustrated in Figure 3. This simulation was created for a spectrum recorded from a plasma generated using the I-DBD configuration, operated without any molecular gas injection.

Figure 3.

OH(A-X) spectrum overlapping with an experimental spectrum acquired for an Ar flow of 3000 sccm, using a power of 100 W. The rotational temperature computed in this case was Trot = 630 ± 15 K.

3. Results

3.1. Determination of the I- and Y-DBD Plasma Jets’ Operating Domains

The first objective of this work was to gather information regarding the working domains of the plasma jets with injected molecular gases in both geometries. This study was performed to facilitate a comparison of the operating conditions for each plasma jet geometry. The reactive gases were introduced up to the highest reactive-to-main-gas ratios compatible with the sources’ operation.

Figure 4 shows that each geometry is characterized by two main operational domains: a stable plasma region and a region where instabilities occur. Beyond these regions, the plasma is either extinguished or cannot be operated under safe conditions due to the risk of source damage due to tube heating in the proximity of the power electrode. A stable plasma jet refers to the regime in which the generated plasma jet remains anchored to a fixed point on the dielectric surface (glass/quartz tube), maintaining its position over time. In contrast, instabilities are associated with the continuous lateral or axial displacement of the anchoring point within the tube. Additionally, at a high power, thermal energy is transferred from the plasma to the dielectric tube, potentially leading to source degradation. For both geometries, the lower boundary of the stable region corresponds to the minimum power required to ignite the discharge. In contrast, the upper boundary of the unstable region indicates the maximum power that can be safely applied to the discharge while preserving the physical integrity of the plasma source. Also, for both geometries, within the power range of 40–60 W, the plasma jet does not extend outside the tube.

Figure 4.

Comparative view of the working domains of the I- and Y-DBD in (a) Ar/O2 admixtures and (b) Ar/N2 admixtures.

The analysis reveals that in the case of the I-DBD geometry, where both the main gas and the molecular gases are injected prior to the discharge, the plasma remains stable at very low concentrations of O2/N2 (ranging from 0 to 0.033%). In terms of power variation, the plasma jet can be generated in a stable way with powers varying from 43 to 145 W for O2 injection and from 45 to 130 W for N2 addition.

Regarding the Y-DBD source, it can be clearly observed that the operating range can be considerably widened. Also, this geometry can operate with high molecular gas concentrations (up to 50%) and ensures stable operation from low powers (40 W) to high powers (~140 W) for both O2 and N2 injection. Additionally, for plasma generated using this geometry, when the concentration of the injected molecular gas exceeds 30%, the filamentary jet is no longer observed outside the tube. Instead, a diffuse regime can be seen, known as the post-discharge or afterglow [42]. This zone is dominated by the presence of long-living species.

3.2. Behavior of the Emitting Species at the Tube Exit

Figure 5 presents a general spectrum of the plasma jet obtained at the exit of the tube for a Y-DBD operated at 100 W RF power with 3000 sccm of Ar in the absence of any reactive gas. The spectrum is similar to that obtained from the I-DBD under the same conditions. The predominant emission lines are those occurring due to the de-excitation of Ar atoms. The most intense are those associated with Ar I (695.65 nm, 706.72 nm, 739.39 nm, 763.51 nm, 772.42 nm, and 794.81 nm). Additionally, in the small-wavelength region of the spectrum, emissions from radical species such as γNO (A 2Σ+−X 2Π), OH (A 2Σ+, ν′ = 0−X 2Π, ν″ = 0), and N2 (C3Πu−B 3Πg) nm are observed, resulting from the uptake of N2, O2, and H2O vapor from the atmospheric air.

Figure 5.

General OES spectra for the plasma jet (near the tube edge): (a) extended view of the 200–800 nm spectral range; (b) detailed view of the 200–450 nm spectral range.

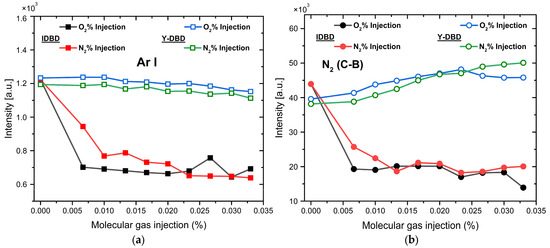

A comparative spectral analysis was performed between the two discharge geometries, I-DBD and Y-DBD, focusing on the emission of the key species observed (as illustrated in Figure 6), namely the Ar(4p–4s) transitions, the band heads of the molecular nitrogen SPS system N2(C–B), the nitric oxide NO(A–X) band, and the hydroxyl radical OH(A–X) emission. Since the injection of high levels of molecular gas leads to the extinction of the I-DBD plasma, only nitrogen and oxygen injection ratios up to 0.033% can be considered for a consistent comparison purposes.

Figure 6.

Spectral comparison between I and Y- DBD sources: (a) Ar I, (b) N2(C-B), (c) OH(A-X), and (d) NO(A-X) emissions (full symbols are used for I-DBD, while empty ones are used for the Y-DBD configuration).

Concerning the Ar and N2 (SPS) emissions (Figure 6a,b), a very clear distinction between the two configurations is noticeable for both O2 and N2 injections. Thus, while in the case of I-DBD, the emission of the investigated species drastically decreases with an increasing molecular gas ratio, in contrast, for the Y-DBD configuration, the plasma emission remains high and even slightly increases in the case of N2 (SPS). Similar trends are observed for the OH radical emission (Figure 6c): for the I-DBD configuration, increasing the molecular gas injection ratio results in a decrease in the emission intensity by approximately a factor of two, while for the Y-DBD source, the OH signal remains nearly constant, with only a slight increase observed for a nitrogen injection ratio of around 0.015%.

With respect to the NO radical (Figure 6d) generated by the I-DBD source, both molecular gas injections lead to a sharp increase in emission intensity (by a factor of approximately five), with a maximum at a reactive gas injection ratio of around 0.02%, followed by a pronounced decrease. The plasma generated with the Y-DBD source exhibits a lower NO emission intensity and a smoother evolution with the injection ratio. In this case, the emission intensities evolve to a less pronounced maximum, occurring at lower flows for nitrogen (around 0.015%) and higher ones for oxygen (0.033%). In both cases, the intensity increases by about a factor of two compared to the situation without molecular gas injection. Overall, as a general observation, the NO emission behavior is different compared to the other investigated species.

4. Discussion

The main difference between the two plasma sources lies in the gas injection geometry. This has a significant impact on the plasma behavior, effectively extending the range of stable operation of the Y-DBD source from injections of only small amounts of molecular gas (0.033% in case of I-DBD) up to concentrations as high as 50% (Figure 4). Also, the emission behavior is significantly modified (Figure 6). In the following, we show, using the schematic representation in Figure 7, which illustrates the nitrogen injection case, how the observed characteristics relate to the discharge phenomena and plasma processes in the two sources.

Figure 7.

Most important species and processes occurring in (a) the I-DBD source with Ar injection, (b) the I-DBD source with Ar + N2 injection, and (c) the Y-DBD source with Ar + N2 injection.

Figure 7a schematically presents the plasma jet in the I-DBD configuration when operated solely in Ar. As shown previously [28], the discharge consists of a filamentary plasma jet with a diameter of about 600 μm, surrounded by a diffuse plasma region. The dominant reactions in the tube are the electron-impact excitation and ionization of Ar atoms inside and along the entire length of the plasma filament, leading to the formation of Ar+ ions and of excited and metastable Arm (1s5, 1s3) states. The radial diffusion of peripheral electrons and of long-lived species (Ar+, Arm) feeds energy into the discharge processes in the diffuse region which surrounds the filament. Despite the use of argon without molecular gas injection, the emission recorded near the tube exit still shows spectral signatures of the excited states of reactive species such as N2(C), OH(A), NO(A), and N2+(B). These arise from the interaction of energetic electrons and Ar metastables with residual impurities (H2O vapors) in the gas line, as well as from the diffusion of ambient N2, O2, and H2O vapor into the plasma jet.

The observed behavior can be explained by considering the general effects produced on atomic plasmas when molecular gases are injected. When a molecular gas is injected premixed with Ar in the I-DBD (Figure 7b), the plasma is generated within the molecular mixture Ar–N2 (or Ar–O2). Because molecular gases efficiently absorb energy from electrons through multiple channels such as vibrational and rotational excitation modes, dissociation processes (leading to the formation of N or O atoms), and metastable species (like N2(A)) formation, the electron energy distribution in the discharge is expected to be modified compared to the operation with argon as the sole feeding gas. This situation is well documented in the literature [43,44]. As a result, less energy is available for ionization. Fewer new charges capable of compensating for charge losses are created, thus leading to discharge extinction with the increase in the molecular gas ratio in the admixture. In conclusion, the premixed injection of the molecular gas induces additional energy-consuming processes that limit the operating range of the I-DBD at a given power, even at low injection ratios.

In comparison, in the Y-DBD configuration presented in Figure 7c, the molecular gas is introduced through the lateral inlet positioned downstream of the powered electrode. This geometry can be divided into two distinct regions, labeled A and B. From the extinction perspective, region A corresponds to a plasma formation zone similar to that in the I-DBD configuration operating with argon as the only feeding gas (Figure 7a). When the molecular gas is injected laterally into region B, it interacts with the Ar plasma sustained by the upstream discharge. Consequently, the impact of molecular gas injection on the discharge extinction is diminished, and higher amounts of molecular gas can be introduced. From an energy-transfer perspective, region A is characterized by the intense production of Ar ions and metastable species through collisions with electrons, similar to the I-DBD operated without molecular gas injection, while region B involves electron-driven processes together with an additional energy transfer from upstream Ar ions and metastables. It is also worth noting that the injected molecules predominantly enter the diffuse part of the jet. Here, the energy transfer mechanism is dominated by collisions between electrons and argon metastables and ions diffusing from the filamentary region, as well as with the molecular species present in the surrounding plasma.

To provide a better understanding of the relationship between the spectral behavior and the processes in the plasma jet, the data presented in Figure 6 were normalized to their respective maximum values and are shown, together with the rotational temperatures and electron densities, in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Normalized emission intensities of the investigated species: (a) I-DBD with O2 injection, (b) I-DBD with N2 injection, (c) Y-DBD with O2 injection, and (d) Y-DBD with N2 injection (each scaled to its maximum value), shown together with the rotational temperature obtained from OH(A−X) simulations and the electron densities determined from Stark lines broadening.

It is worth mentioning that the recorded emission contains the integrated signal from both the diffuse and the bright filament regions of the discharge. However, the filament emission strongly exceeds the diffuse emission, and therefore the observed spectral behavior can be primarily attributed to the excitation processes in the filament. The excitation in this region is dominated by electron-impact processes, as indicated by the strong Ar emission lines. Such excitation depends on the total number of electrons and on their energy distribution. Since the electron density remains nearly constant (~5 × 1014 cm−3) over the investigated injection-ratio range (see Figure 8), it follows that the observed trends are likely related to changes in the electron energy distribution. Therefore, despite the lack of a direct measurement of the electron distribution, it is reasonable to assume, supported by the extinction behavior, that the spectral variations originate predominantly from modifications in the electron energy distribution function.

In particular, in the I-DBD injection type, the molecular gas (O2 or N2) premixed with Ar enters the discharge, and even when small molecular fractions (~0–0.033%) are present, the electron energy distribution function (EEDF) is likely shifted toward lower electron energies, as suggested by the extinction behavior discussed above. Therefore, besides the tendency towards discharge extinction, a sharp decrease in the Ar line intensity is observed. The similar behavior of the N2(C) and OH(A) band intensities indicates that these emissions are also driven by electronic excitation, and their reduced intensities suggest that the excitation processes become less efficient as the average electron energy decreases.

However, the electronic excitation mechanisms differ for each of the species discussed above. A single-step excitation process (1) is sufficient for species already present in the gas phase, such as Ar and O2 (or N2). In contrast, the OH radical emission requires a two-step mechanism: first its formation (via electronic collisions (2) or dissociative energy transfer (3)), followed by excitation (4).

In reactions 1–4, denotes the electrons entering the collision with energies higher than the excitation (1) and (4) or dissociation (2) thresholds, while denotes those electrons which lost their energy upon excitation or dissociation of the collided species.

In the Y-DBD configuration, where the molecular gas is injected separately into the already existing Ar plasma, it is noteworthy that the Ar(5p–4s), N2(C–B), and OH(A–X) emissions remain nearly constant as the molecular gas concentration increases. This behavior suggests that the EEDF in the filamentary zone is not strongly affected, which may be explained by the limited diffusion of the injected gas into the filament. Therefore, in the Y-DBD case, the excitation processes may be driven by electron collisions (similarly to the I-DBD operated in Ar) only at the periphery of the Ar plasma filament, leading to electrons that likely exhibit lower energies in this zone. Additionally, since the reactive gas no longer enters directly into the high-electron-energy plasma zone, it interacts mainly with lower-energy electrons and with long-lived argon metastables Arm, transported from upstream or diffusing radially from the filamentary part of the jet. These metastables transfer excitation energy to the injected molecules through Penning excitation processes, as illustrated in reaction (5). Under these conditions, the N2(C) emission exhibits a slight increase, reflecting this additional excitation channel provided by collisions with Ar metastables:

The NO radical emission requires a separate discussion, which must include, besides excitation, the NO formation mechanism. Unlike the O2 (or N2) and Ar, which are injected as stable species into the plasma, or OH, which is formed by the dissociation of water traces (2) and (3) existing in the gas or diffusing from the ambient atmosphere, the NO radical must be synthesized before its excitation. The most likely NO formation mechanisms rely on the presence of atomic N and O, as well as N2 and O2 molecules originating either from the molecular gas injection or from ambient diffusion. These reactions are presented below:

As an additional argument in favor of the mechanism based on (6) in the case of N2 injection, it is observed in Figure 8 that the increase in NO emission correlates with a slight drop in the gas temperature (estimated as the OH rotational temperature). This cooling effect may be associated with the endothermic nature of (6) [45], leading to NO formation.

The most efficient channel for atom formation is electron-impact collisions, which is additionally favored by the vibrational–rotational excitation of parent molecules, as this reduces the energy needed for electrons to dissociate them (9).

Furthermore, NO excitation (energy threshold 6.17 eV) is based on the electronic collisions (10) or the energy transfer from metastable species such as Arm and N2(A).

In the I-DBD configuration, with a small amount of premixed molecular gas, the number of produced atoms initially increases with the injected molecular fraction due to the larger number of molecular partners participating in reaction (9). However, this also tends to deplete the high-energy tail of the EEDF, and once the injected-gas ratio exceeds a certain threshold, atom production begins to decrease because the number of electrons with energies above the dissociation threshold becomes insufficient. According to this behavior of the dissociation process, there is an optimal value of the injected-gas ratio that leads to a maximum production of O (or N) atoms. Since NO molecules are easily excited (10) and (11), their emission reaches a maximum at that injected-gas ratio which optimizes the production of atomic precursors. This behavior is clearly illustrated in Figure 8a,b for both O2 and N2 injection in the I-DBD, where the emission intensity exhibits well-defined maxima at specific injected-gas ratios.

In the Y-DBD case, the injection process affects the peripheral zone of the filament, while the properties of the filament core remain similar to those of an I-DBD fed with Ar only. In this peripheral zone, dissociation acts on the molecules that diffuse from the injection point toward the filament edge, and N (or O) atoms are produced along the filament through collisions with high-energy electrons diffusing from the core towards the periphery (like described by (9)). In this region, the depletion of the high-energy tail of the EEDF is continuously compensated by the influx of energetic electrons from the core region. Accordingly, the production of N (or O) atoms inside the tube increases as the injected molecular gas ratio rises. At the tube exit, these atoms interact with the gases diffusing into the plasma from the surrounding air, which enhances NO formation, depending on the local availability of O or N atoms. At higher injection ratios, however, collisional quenching of NO* states, together with the formation of secondary species such as NO2, N2O, and O3, becomes dominant and leads to a decrease in NO emission [46]. The observed increase followed by a decrease in NO emission intensity for the Y-DBD configuration is consistent with this interpretation (Figure 8c,d).

It is worth noting that, in the case of N2 injection, the NO emission maximum appears at lower injected-gas ratios compared to O2 injection. Considering the dissociation thresholds, the opposite trend would be expected, since the dissociation energy of N2 (9.76 eV) is significantly higher than that of O2 (5.12 eV). This suggests that an additional dissociation pathway may be active, or that NO is generated directly through alternative channels.

A plausible explanation is that N2(A) metastable molecules are present at high concentrations in this region, given their long radiative lifetime (~2 s) and their efficient production through both electron impact (12) and energy transfer from Arm (13).

Therefore, when N2 is injected, two additional routes can enhance NO production: a channel that enables easier N2 dissociation (14) and (15) (the electron-impact dissociation mechanism is more effective for the metastable state N2(A), whose dissociation threshold is only 3.53 eV), and a channel that leads directly to NO (16).

The main difference between the two configurations is that, in the mixed-gas configuration (I-DBD), the NO evolution is controlled by the kinetics governed by electron-impact processes inside the discharge filament, while in the Y-DBD, it becomes controlled by the formation, diffusion, and spatial overlap of reactive species outside the filament. In conclusion, with respect to NO production, the present results show that the I-DBD source with upstream mixed-gas injection is superior to the Y-DBD, as dissociation is more active in the filament core, where higher amounts of N or O species are produced at the same injection ratios, despite the presumed reduction in the high-energy electron population. The complementary reactants (i.e., O2 or N2) are supplied by the diffusion of ambient air into the plasma. This leads to the production of more NO molecules and to a higher NO emission in the I-DBD configuration.

As a final remark, the present work demonstrates the utility of spectral discharge diagnostics in elucidating the mechanisms of species formation in cold atmospheric pressure plasma jets. The results provide valuable guidance for selecting conditions that optimize the production of reactive species at the tube exit, such as NO radicals. These findings should be regarded as a starting point for further studies aimed at determining the nature and concentration of reactive species at various distances from the tube exit, which is particularly relevant for surface-processing applications (e.g., wettability control, activation, cleaning, decontamination, and sterilization). They are also important for quantifying the total amount of reactive species released into the surroundings of the plasma jet.

In the latter case, the large contact interface between the jet and the reactive molecular gas, combined with the more energetic and spatially extended filament of the Y-DBD configuration, may make this configuration particularly suitable for volume applications such as air purification and liquid treatment. The validation of the usefulness of the described I-DBD or Y-DBD plasma sources in the application field is provided by several reported experiments, including the modification of biobased poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) polymer surfaces [47], the decomposition of the methylene blue dye or the degradation of organophosphorus toxic compounds in aqueous solutions [22,23], and the modification of cellulose nanomaterials through plasma-in-liquid treatments [48]. From an application perspective, it is also worth mentioning that these sources are scalable, as demonstrated, for example, in [47], where a planar source with an extended processing area is presented, or by assembling multiple tubular sources in linear arrays.

5. Conclusions

Knowledge of the properties of atmospheric pressure plasma sources and their ability to produce reactive species is of paramount importance for their application.

The results presented here show that the gas-injection configuration has a significant influence on plasma stability and reactive species production. In the premixed-gas configuration (I-DBD), where the processes are driven by electronic collisions, the injection of molecular gases induces substantial modification of the electron energy distribution, leading to plasma extinction and reduced emission of reactive species. In contrast, downstream introduction of the molecular gas into the discharge (Y-DBD) leads to a more controlled plasma, thereby extending the stable operating range up to higher molecular gas concentrations. Moreover, the separation between the argon discharge region and the molecular injection zone allows the plasma chemistry to evolve more gradually, favoring processes involving heavy species rather than being dominated by electron-impact mechanisms. As a result, the plasma remains stable over a significantly broader range of molecular gas concentrations, from small amounts up to 50%, and, consequently, a different behavior of the species emission is observed at the tube exit.

From a practical point of view, the results show that plasmas generated using the Y-DBD configuration are more stable and capable of sustaining the balanced production of reactive species such as NO(A), OH(A), and N2(C), whereas the I-DBD configuration can be tuned to selectively enhance NO generation.

The single-filament RF plasma jet, characterized by its long spatial extension beyond the source exit and its large interaction surface with the surrounding medium along its length, is particularly well suited to applications that require the treatment of large volumes of matter compared with other atmospheric pressure plasma jets. Examples include air decontamination, the decomposition of volatile organic compounds, gas-phase chemical processing, pollutant degradation, and nanomaterial synthesis in liquids. Furthermore, the present work demonstrates the usefulness of electrical and spectroscopic discharge diagnostics in elucidating the mechanisms of species formation in cold atmospheric pressure plasma jets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C. and G.D.; methodology, C.C., B.M., M.B. and G.D.; validation, C.C., M.B. and B.M.; investigation, C.C., M.B. and C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C. and GD; writing—review and editing, B.M. and G.D.; visualization, C.C.; supervision, G.D.; funding acquisition: G.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Romanian Ministry of Education and Research under PNCDI IV (Program 5/5.9/ELI-RO, project ELI-RO/RDI/2024_015; Nucleus Program, ctr 30N/2023 (LAPLAS VII) and by the European Union through the EUROfusion Consortium (workpackage WPTRED).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Part of this work has been carried out within the framework of the EUROfusion Consortium, funded by the European Union via the Euratom Research and Training Programme (Grant Agreement No 101052200—EUROfusion). The views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Commission. Neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be held responsible for them.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Z. Correlation of Reflected Plasma Angle and Weld Pool Thermal State in Plasma Arc Welding Process. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 75, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, M.J.; Malley, D.R. Plasma Arc Melting of Titanium Alloys. Mater. Des. 1993, 14, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-I.; Kim, M.-H. Evaluation of Cutting Characterization in Plasma Cutting of Thick Steel Ship Plates. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2013, 14, 1571–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tendero, C.; Tixier, C.; Tristant, P.; Desmaison, J.; Leprince, P. Atmospheric Pressure Plasmas: A Review. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2006, 61, 2–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamovich, I.; Agarwal, S.; Ahedo, E.; Alves, L.L.; Baalrud, S.; Babaeva, N.; Bogaerts, A.; Bourdon, A.; Bruggeman, P.J.; Canal, C.; et al. The 2022 Plasma Roadmap: Low Temperature Plasma Science and Technology. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2022, 55, 373001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroussi, M.; Tendero, C.; Lu, X.; Alla, S.; Hynes, W.L. Inactivation of Bacteria by the Plasma Pencil. Plasma Process. Polym. 2006, 3, 470–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, K.; Ichiki, R.; Kanbara, Y.; Kojima, K.; Tachibana, K.; Furuki, T.; Kanazawa, S. Bright Nitriding Using Atmospheric-Pressure Pulsed-Arc Plasma Jet Based on NH Emission Characteristics. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 59, SHHE01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; van de Wege, R.; Sobota, A. Nitric Oxide (NO) Production in a KHz Pulsed Ar Plasma Jet Operated in Ambient Air. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2025, 34, 045013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.; Hayhurst, A.N. The Chemical Reactions of Nitric Oxide with Solid Carbon and Catalytically with Gaseous Carbon Monoxide. Fuel 2015, 142, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanmore, B.R.; Tschamber, V.; Brilhac, J.F. Oxidation of Carbon by NOx, with Particular Reference to NO2 and N2O. Fuel 2008, 87, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.S.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, S.O. Reactive Oxygen Species Controllable Nonthermal Atmospheric Pressure Plasmas Using Coaxial Geometry for Biomedical Applications. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2014, 42, 2490–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedrick, J.; Schröter, S.; Niemi, K.; Wijaikhum, A.; Wagenaars, E.; De Oliveira, N.; Nahon, L.; Booth, J.P.; O’Connell, D.; Gans, T. Controlled Production of Atomic Oxygen and Nitrogen in a Pulsed Radio-Frequency Atmospheric-Pressure Plasma. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2017, 50, 455204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagatomo, T.; Abiru, T.; Mitsugi, F.; Ebihara, K.; Nagahama, K. Study on ozone treatment of soil for agricultural application of surface dielectric barrier discharge. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 55, 01AB06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyucharev, A.N.; Pechatnikov, P.A. Plasma Ion Source Based on the Barrier Discharge for Earth Atmosphere Pollution Monitoring Systems. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 8, 783–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirafuji, T.; Oh, J.-S. Reaction Kinetics of Active Species from an Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet Irradiated on the Flowing Water Surface-Effect of Gas-Drag by the Sliding Water Surface. J. Photopolym. Sci. Technol. 2019, 32, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmonte, T.; Noël, C.; Gries, T.; Martin, J.; Henrion, G. Theoretical Background of Optical Emission Spectroscopy for Analysis of Atmospheric Pressure Plasmas. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2015, 24, 064003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleslić, S.; Katalenić, F. Monitoring and Diagnostics of Non-Thermal Plasmas in the Food Sector Using Optical Emission Spectroscopy. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaplotnik, R.; Primc, G.; Vesel, A. Optical Emission Spectroscopy as a Diagnostic Tool for Characterization of Atmospheric Plasma Jets. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubka, Z.; Novák, J.; Majerová, I.; Green, J.T.; Velpula, P.K.; Boge, R.; Antipenkov, R.; Šobr, V.; Kramer, D.; Majer, K.; et al. Mitigation of Laser-Induced Contamination in Vacuum in High-Repetition-Rate High-Peak-Power Laser Systems. Appl. Opt. 2021, 60, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolenis, T.; Vazquez, S.; Ramalis, L.; Havlík, M.; Chauvin, A.; Těreščenko, A.; Espinoza, S.; Fučíkova, A.; Andreasson, J.; Havlickova, I.; et al. Complex Analysis of Laser Induced Contamination in High Reflectivity Mirrors. High Power Laser Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu, C.; Alegre, D.; Ionita, E.R.; Mitu, B.; Grisolia, C.; Tabares, F.L.; Dinescu, G. Cleaning of Carbon Materials from Flat Surfaces and Castellation Gaps by an Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet. Fusion Eng. Des. 2016, 103, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehia, S.A.; Zarif, M.E.; Bita, B.I.; Teodorescu, M.; Carpen, L.G.; Vizireanu, S.; Petrea, N.; Dinescu, G. Development and Optimization of Single Filament Plasma Jets for Wastewater Decontamination. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2020, 40, 1485–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehia, S.A.; Petrea, N.; Grigoriu, N.; Vizireanu, S.; Zarif, M.E.; Carpen, L.G.; Ginghina, R.E.; Dinescu, G. Organophosphorus Toxic Compounds Degradation in Aqueous Solutions Using Single Filament Dielectric Barrier Discharge Plasma Jet Source. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 46, 102637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionita, M.D.; Vizireanu, S.; Stoica, S.D.; Pandele, A.M.; Cucu, A.; Stamatin, I.; Nistor, L.C.; Dinescu, G. Functionalization of Carbon Nanowalls by Plasma Jet in Liquid Treatment. Eur. Phys. J. D 2016, 70, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizireanu, S.; Panaitescu, D.M.; Nicolae, C.A.; Frone, A.N.; Chiulan, I.; Ionita, M.D.; Satulu, V.; Carpen, L.G.; Petrescu, S.; Birjega, R.; et al. Cellulose Defibrillation and Functionalization by Plasma in Liquid Treatment. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolouki, N.; Hsieh, J.H.; Li, C.; Yang, Y.Z. Emission Spectroscopic Characterization of a Helium Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet with Various Mixtures of Argon Gas in the Presence and the Absence of De-Ionized Water as a Target. Plasma 2019, 2, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.C.; Li, Q.; Zhu, X.M.; Pu, Y.K. Characteristics of Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jets Emerging into Ambient Air and Helium. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2009, 42, 202002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodorescu, M.; Bazavan, M.; Ionita, E.R.; Dinescu, G. Characteristics of a Long and Stable Filamentary Argon Plasma Jet Generated in Ambient Atmosphere. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2015, 24, 025033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, M.A.; Lichtenberg, A.J. (Eds.) Index. In Principles of Plasma Discharges and Materials Processing; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 749–757. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, P.; Zhang, J.; Nguyen, T.; Donnelly, V.M.; Economou, D.J. Numerical Simulation of an Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet with Coaxial Shielding Gas. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2021, 54, 075205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, S.; Tresp, H.; Wende, K.; Hammer, M.U.; Winter, J.; Masur, K.; Schmidt-Bleker, A.; Weltmann, K.D. From RONS to ROS: Tailoring Plasma Jet Treatment of Skin Cells. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2012, 40, 2986–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, S.; Winter, J.; Schmidt-Bleker, A.; Tresp, H.; Hammer, M.U.; Weltmann, K.D. Controlling the Ambient Air Affected Reactive Species Composition in the Effluent of an Argon Plasma Jet. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2012, 40, 2788–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüttler, S.; Kaufmann, J.; Golda, J. Nitrogen Fixation and H2O2 Production by an Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet Operated in He–H2O–N2–O2 Gas Mixtures. Plasma Process. Polym. 2024, 21, e2300233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.A.H.; Basher, A.H.; Almarashi, J.Q.M.; Ouf, S.A. Susceptibility of Staphylococcus Epidermidis to Argon Cold Plasma Jet by Oxygen Admixture. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, A.H.; Galaly, A.R. The Effect of Oxygen Admixture with Argon Discharges on the Impact Parameters of Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet Characteristics. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Naidis, G.V.; Laroussi, M.; Reuter, S.; Graves, D.B.; Ostrikov, K. Reactive Species in Non-Equilibrium Atmospheric-Pressure Plasmas: Generation, Transport, and Biological Effects. Phys. Rep. 2016, 630, 1–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griem, H.R.; Kolb, A.C.; Shen, K.Y. Stark Broadening of Hydrogen Lines in a Plasma. Phys. Rev. 1959, 116, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigosos, M.A.; Gonzalez, M.A.; Cardenoso, V. Spectrochimica Acta Electronica Computer Simulated Balmer-Alpha,-Beta and-Gamma Stark Line Profiles for Non-Equilibrium Plasmas Diagnostics. Spectrochim. Acta Part B 2003, 58, 1489–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.-K.; Montaser, A. Determination of Electron Number Density via Stark Broadening with an Improved Algorithm. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 1989, 44, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazavan, M.; Teodorescu, M.; Dinescu, G. Confirmation of OH as Good Thermometric Species for Gas Temperature Determination in an Atmospheric Pressure Argon Plasma Jet. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2017, 26, 075001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Fattah, E.; Bazavan, M.; Shindo, H. Temperature Measurements in Microwave Argon Plasma Source by Using Overlapped Molecular Emission Spectra. Phys. Plasmas 2015, 22, 093509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Li, S.Z. Investigation of a Nitrogen Post-Discharge of an Atmospheric-Pressure Microwave Plasma Torch by Optical Emission Spectroscopy. Phys. Plasmas 2017, 24, 033512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Gangwar, R.K.; Srivastava, R. Diagnostics of Ar/N2 Mixture Plasma with Detailed Electron-Impact Argon Fine-Structure Excitation Cross Sections. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2018, 149, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boris, D.R.; Petrov, G.M.; Lock, E.H.; Petrova, T.B.; Fernsler, R.F.; Walton, S.G. Controlling the Electron Energy Distribution Function of Electron Beam Generated Plasmas with Molecular Gas Concentration: I. Experimental Results. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2013, 22, 065004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouwenhorst, K.H.R.; Jardali, F.; Bogaerts, A.; Lefferts, L. From the Birkeland–Eyde Process towards Energy-Efficient Plasma-Based NOX Synthesis: A Techno-Economic Analysis. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 2520–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaens, W.V.; Iseni, S.; Schmidt-Bleker, A.; Weltmann, K.D.; Reuter, S.; Bogaerts, A. Numerical Analysis of the Effect of Nitrogen and Oxygen Admixtures on the Chemistry of an Argon Plasma Jet Operating at Atmospheric Pressure. New J. Phys. 2015, 17, 033003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaitescu, D.M.; Vizireanu, S.; Raduly, M.F.; Sătulu, V.; Stancu, C.; Marascu, V.; Nicolae, C.-A.; Gabor, A.R.; Oprică, G.M.; Uşurelu, C.D.; et al. Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) Modified with Toughening Agents and Surface Treated by Atmospheric Cold Plasma for Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 333, 148780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaitescu, D.M.; Vizireanu, S.; Stoian, S.A.; Nicolae, C.-A.; Gabor, A.R.; Damian, C.M.; Trusca, R.; Carpen, L.G.; Dinescu, G. Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) Modified by Plasma and TEMPO-Oxidized Celluloses. Polymers 2020, 12, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).