Featured Application

The results obtained in the study indicate the possibility of using cellulases produced by basidiomycetes in industry. These enzymes may be an attractive alternative to preparations obtained from Trichoderma reesei due to the possibility of combining the utilisation of agricultural waste (cheap substrate) to obtain two streams of profits, namely fruiting bodies and efficient cellulolytic enzymes.

Abstract

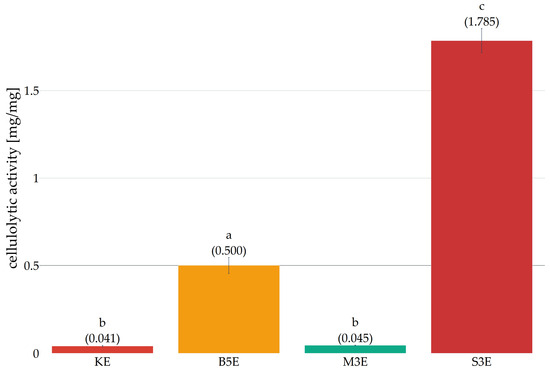

The objective of the present study was to ascertain the potential of cellulolytic enzymes produced by selected species of basidiomycetes: Pleurotus ostreatus, Pleurotus eryngii, and Lentinula edodes. In the experimental phase, a selection of basidiomycetes were cultivated on waste substrates containing coffee grounds and wood. During the culture, weekly samples of the substrate were taken, from which enzymes were extracted using citrate buffer (BCA) and purified to obtain cellulolytic preparations. The activity of the obtained preparations was then compared with that of commercial cellulase in a hydrolysis reaction of carboxymethylcellulose (CMC). Statistical analysis demonstrated that the preparations obtained from L. edodes (1.785 mg/mg) and P. ostreatus (0.500 mg/mg) cultures exhibited higher activity compared to commercial cellulase (0.041 mg/mg), while preparations from P. eryngii (0.045 mg/mg) demonstrated comparable activity. The findings of this study demonstrate the viability of utilising a waste substrate comprising coffee grounds and wood for the cultivation of basidiomycetes and the production of enzymes.

1. Introduction

The production and processing of agricultural crops contribute to the creation of approximately 200 billion tons of plant biomass on an annual basis, 85% of which is lignocellulosic waste. The majority of this waste is generated in food processing plants and the wood industry; however, there are exceptions to this, in which cases it is collected exclusively by the end consumer. A perfect example of this phenomenon is brewed tea or coffee grounds. The production of coffee beans invariably results in the generation of waste materials, including husks. The management of this waste is the responsibility of the producing countries, with the calculation being that 1 kg of roasted coffee beans produces 1 kg of husks. In contrast, coffee grounds are produced in all parts of the world. The amount of coffee waste is contingent on geographical location, coffee consumption habits, and population density. According to the Agronomist portal, 120,000 tons of coffee grounds are produced in Poland on an annual basis. Meanwhile, Europe as a whole produces 3.5 million tons of grounds, of which only 1% is managed. In view of the substantial volume of this waste and the presence of fats, polysaccharides and proteins within it, a significant number of companies are endeavouring to utilise this raw material in the manufacture of new products. This type of waste is notoriously challenging to dispose of due to its susceptibility to microbial contamination and prolonged decomposition [1,2].

In the context of the mounting imperative for sustainable organic waste management and the pursuit of efficacious methodologies for its utilisation, saprotrophic fungi are eliciting a growing interest. A salient feature of the metabolism of these fungi pertains to their capacity to synthesize cellulolytic enzymes, encompassing cellulases and hemicellulases. These enzymes facilitate the decomposition of cellulose and hemicellulose into more elementary sugars, a process that underpins their ecological significance. The resulting compounds are then absorbed by the fungi through nutritional absorption. The three primary groups of enzymes implicated in the hydrolysis of lignin and cellulose agricultural waste are cellulases, xylanases, and ligninases. It has been demonstrated that species such as Pleurotus ostreatus, Pleurotus eryngii, and Lentinula edodes exhibit high levels of enzymatic activity, thus enabling them to effectively utilise a variety of waste materials as a source of carbon and energy. The capacity of basidiomycetes to thrive on agricultural and food waste enables their utilisation for the cultivation of fungal biomass (fruiting bodies). This has the effect of reducing the cost of producing fruiting bodies and other derivatives (including polysaccharides) with less exploitation of the natural environment. The objective of waste management is to reduce the amount of new waste and, in the case of existing waste, to manage it skilfully as a material for the production of other goods. This is in line with the idea of the circular economy, which aims to minimise the use of natural resources and reduce greenhouse gas emissions throughout the production chain. The utilisation of substrates derived from coffee grounds has been demonstrated to serve a dual purpose; it has been shown to reduce greenhouse gas emissions while concomitantly exerting a favourable influence on the development of mycelium and primordium in Pleurotus eryngii [3,4,5].

Fungal enzymes are of particular interest due to the ability of fungi to grow on inexpensive materials (including waste) and secrete large quantities of enzymes into the culture medium. This facilitates further extraction and processing of the final preparations. A wide range of fungal enzymes are available in the commercial sector, including amylases, cellulases, lipases, phytases, proteases and xylanases [6].

Most applications of enzymes in the food industry focus on hydrolytic reactions. Cellulase, pectinase, and xylanase enzymes are frequently employed in the clarification of juices and wines [6,7,8,9]. In addition, hydrolases are used in recycling waste paper, because they facilitate the removal of ink from paper pulp (used waste paper). Lipase catalyses the hydrolysis of fat-based ink carriers, while cellulase, pectinase and xylanase facilitate the release of ink from the fiber surface through partial hydrolysis of the polysaccharides that constitute paper fibers. The primary benefit of enzymatic deinking is the elimination of the use of alkalis. The utilisation of enzymes in an acidic pH environment has been shown to prevent alkaline yellowing, while concurrently simplifying the decolorisation process and reducing environmental pollution, enhance the brightness of the fibres, the strength characteristics and the purity of the paper pulp. Enzymes are also employed in the production of primary paper pulp from trees, where xylanase and ligninase are utilised to enhance the quality of the pulp by removing lignin and hemicellulose impurities. Enzymatic decolorization has been identified as a process with considerable potential from both a commercial and environmental perspective. A significant body of research is currently underway on the use this process for the bioremediation of water contaminated with dyes from the textile and dyeing industries [10,11].

Enzymes such as cellulases, xylases, and β-galactanases are utilised as additives in cereal feed for monogastric animals (e.g., poultry and pigs). The consequence of the action of such enzyme mixtures is an enhancement of the digestibility of feed and the efficiency of its energy and nutrient utilisation by animals [12,13].

It is evident that fungi, due to their abundance of cellulolytic enzymes, offer considerable ecological potential for the treatment of numerous problematic types of persistent organic pollutants. However, the practical application of basidiomycetes is limited by the requirement to use significant amounts of enzymes in industrial processes. The economics of enzyme production by these fungi are not yet well understood. This is partly due to the fact that most research in this area is at an early stage and focuses on scientific aspects, such as the influence of the substrate profile on the secreted secretome or the characteristics of the molecular substrates of enzyme production [14,15].

The prevailing market standard is represented by preparations derived from Trichoderma reesei (Ascomycota), whose optimised strains in submerged fermentation have been shown to produce up to 100 g/L of cellulolytic enzyme mixtures. Conversely, the yield of basidiomycetes (e.g., Pleurotus ostreatus/eryngii) remains at a significantly lower level: approximately 10 mg/L of extracellular proteins in liquid cultures and 1–3 mg/g in solid cultures [16,17]. This finding underscores the imperative for enhancing the synthesis efficiency of Basidiomycota fungi to a magnitude that is manyfold greater than its current state, thereby rendering them a competitive alternative.

Research on the activity, synthesis mechanism, and extraction method of extracellular enzymes focuses mainly on the most popular fungal species in terms of production. The following genera are included: Lentinula (22% of mushrooms cultivated worldwide), Pleurotus (19%), Auricularia (17%), Agaricus (15%), and Flammulina (11%) [18]. For instance, a study by [19] demonstrated the potential for the isolation of enzymes, including amylase, cellulase, xylase, and laccase, from the substrate following the cultivation of the fungi Pleurotus ostreatus, P. eryngii, and P. cornucopiae. Consequently, the focal point of this study is the production of fruiting bodies, in conjunction with the extraction of enzymes from the post-cultivation substrate or bioactive compounds. This approach appears to be both financially lucrative and promising.

The present study aims to evaluate the cellulolytic activity of selected cultivated fungi species (Pleurotus ostreatus, Pleurotus eryngii, and Lentinula edodes) under cultivation conditions using non-standard substrates, namely coffee grounds and waste wood. The materials under consideration are both readily available, inexpensive, and rich in organic compounds that can provide a good basis for mycelium growth and enzyme production. The objective of this study is to ascertain the extent to which individual mushroom species possess the capacity to produce cellulolytic enzymes under such conditions, and to evaluate the potential for utilising these substrates in mushroom cultivation from the perspective of the circular economy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The biological material used in this study was commercial mycelium of three species of basidiomycetes: Pleurotus ostreatus, Pleurotus eryngii, and Lentinula edodes inoculated on wooden pegs, purchased from the supplier “Lucky Forest” Daniel Wieczorek in Warsaw, Poland. The study utilised air-dried (at ambient temperature) coffee grounds, which were obtained by brewing coffee (a blend of Arabica and Robusta) in a De’Longhi Magnifica S coffee machine (De’Longhi S.p.A., Treviso, Italy) with the grinder set to position 2 and the extraction temperature set to the lowest level, and Cat’s Best Original wood gravel (JRS Petcare GmbH & Co. KG, Rosenberg, Germany). The initial moisture content of the coffee grounds was 9.2% ± 0.2%, and the nitrogen content was 2.22% ± 0.06% (by mass).

The commercial enzyme (KE) used to compare cellulolytic activity with the obtained preparations is a food-grade fungal cellulase derived from Trichoderma reesei. The manufacturer recommends its use for the hydrolysis of non-starch polysaccharides in the fermentation industry.

2.2. Substrate and Growing Conditions

The substrate for culturing basidiomycetes consists of 70% coffee grounds and 30% wood gravel with water added in a ratio of 1.5 to 1 by dry weight. The substrate composition was selected on the basis of [3], which demonstrated optimal growth conditions for P. eryngii. The substrate was then mixed, and 500 g of it was packed into each culture bag. The bags were subsequently sterilised in an autoclave at 121 °C for 15 min. The study used bags produced in-house, made in the same way as those used on commercial farms [20], from BPA- and phthalate-free pressed foil. The bags were equipped with a 15 cm × 10 cm filter made of F9 filter fabric.

Fifteen bags were inoculated for the study, with five bags allocated to each species. Following the inoculation process, the bags were sealed in a manner that allowed air to remain above the substrate, ensuring uninterrupted exchange from the inside through the filter. The culture was sustained for a duration of six weeks within a cultivation tent (Highpro Network SL., Madrid, Spain). This tent was equipped with systems that regulated ventilation, humidity, and lighting, and it also recorded air temperature and humidity at one-minute intervals. During the cultivation process, the use of humidification was employed to ensure the maintenance of air humidity at approximately 90%. In such conditions, the loss of water from the bags due to evaporation was reduced, and subsequently, the mycelium was stimulated to fruit. In addition to adequate humidity, light has been identified as a critical factor in the formation of primordia in Pleurotus spp. and L. edodes. Based on [21], the cultivation was conducted at an ambient temperature of 20–25 °C, with an 8-h exposure to full-spectrum LED light at an intensity of 250 lx.

2.3. Extraction of Extracellular Enzymes from the Culture Medium

The process of extracellular enzyme synthesis was monitored using the methodology described by [22]. From the second week onwards, samples of the culture medium were collected from evenly spaced locations across its entire cross-section, from the top to the bottom, on a weekly basis. Samples were collected until a total mass of 80 g was obtained. Subsequently, the samples were meticulously amalgamated and manually ground, with the objective of mitigating damage to the mycelium and preventing the leakage of the intracellular fraction of hyphae. From the general sample thus created, 20 g were weighed into conical flasks with 100 mL of citrate buffer (BCA, 50 mM, pH = 4.8) and then shaken for one hour at a temperature of 25 °C at 3× g. In the subsequent stage of the experiment, the contents of the flasks were filtered through cotton wool using a funnel. The filtrate obtained was subjected to centrifugation (MPW–260R, MPW MED. INSTRUMENTS, Warsaw, Poland) for 10 min at 1712× g. The supernatant (i.e., the laboratory sample) was collected in Falcon tubes and stored in a freezer set at −20 °C until the relevant tests were performed.

In order to precipitate the target proteins (enzymes), 100 mL of the crude extract was subjected to salting out by adding 60 g of anhydrous ammonium sulfate. This specific addition of 60 g was determined to be the amount required to fully saturate the solution and consequently achieve a state of equilibrium (where no further substance would dissolve) at 4 °C and atmospheric pressure. Following the addition of the salt, the solution was incubated for 12 h at 4 °C to ensure protein precipitation. In the subsequent stage, following the addition of salt, the solution was subjected to a centrifugal process in a centrifuge (MPW–260R, MPW MED. INSTRUMENTS, Warsaw, Poland) for a duration of 10 min at 2236× g. The pellet was suspended in a buffer volume that was 10 times smaller than the initial extract volume, with the objective of increasing the protein concentration (including cellulases) relative to the original sample.

2.4. Determination of Protein Content

The protein content in the enzyme preparations was determined according to the methodology described in [23]. The test sample was subjected to dilution with deionised water, resulting in a volume of 1 mL, and then incubated at room temperature for 10 min with 5 mL of copper reagent. Following this, 0.5 mL Folin–Ciocalteu reagent was added, and the mixture was left to incubate for a further 30 min. Thereafter, the absorptivity of the specimen was measured at a wavelength of 750 nm. The protein concentration was determined by reading the difference in absorbance between the test sample and the blank sample (which contained 1 mL of water instead of the preparation solution). The protein concentration was then converted to milligrams of protein in 1 mL of extract, taking into account the initial dilution of the sample. The calibration curve with the formula y = 1.9218x + 0.1067 (R2 = 0.9901) was used to determine the protein concentration.

2.5. Determination of Sugar Content

The sugar content in the enzyme extracts was determined by reaction with 1% DNS (3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid) reagent according to the method outlined in [24]. For the purpose of this experiment, 1 mL of the test sample was transferred into a test tube. Then, 1 mL of 1% DNS reagent was added, the contents of the tube were vortexed, and the tube was placed in a boiling water bath for 12 min. Subsequent to this period, the tubes were subjected to cooling under running water, after which 5 mL of deionized water was added. Following the addition of water, the contents of the test tube were vortexed once more, and the degree of light absorption was measured spectrophotometrically (V-1200 Spectrophotometer, VWR, Radnor, PA, USA) at a wavelength of 550 nm. The sugar concentration was determined by reading the calibration curve y = 0.6852x (R2 = 0.9992), which was derived from the difference between the sample’s and the blank sample’s (which contained 1 mL BCA buffer instead of the preparation solution) absorbances. The sugar concentration was then converted to milligrams of glucose in 1 mL of extract, with the initial dilution of the sample being taken into account.

2.6. Determination of Cellulolytic Activity

The cellulolytic activity of the extracts was determined using the carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) method proposed by UIPAC and described by [25]. A volume of 0.5 mL of the enzyme preparations and a volume of 0.5 mL of a 1% carboxymethylcellulose solution were measured into a test tube. The test tube was then placed into a water bath at 50 °C for 30 min. The tube was subsequently subjected to cooling and manipulated in accordance with the methodology outlined in Section 2.5, with the objective of ascertaining the quantity of sugar present. The ultimate outcome is the net sugar yield, which is derived by calculating the difference between the sugar content of the sample post-reaction with CMC and the original sugar quantity present in the preparation.

2.7. Statistical Analysis and Visualization of Results

Statistical analysis was performed in the R program 4.5.2 (using the R Commander package). The collected data were then subjected to analysis in terms of standard deviation, normality of distribution (Shapiro–Wilk test), and equality of variance in groups (Leven’s test). After that, the data were subjected to a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). In order to ascertain the differences between the groups, Tukey’s post hoc test was performed. All measurements in the research were performed in three repetitions. Statistical analysis was performed at a significance level of 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Macroscopic Observation of Mycelium Growth

The appearance of Pleurotus ostreatus mycelium after two weeks of cultivation is shown in Figure 1a,b. A well-developed hyphal structure was observed (Figure 1a), penetrating deep into the substrate. The formation of a hard crust on the surface had also begun (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

View of Pleurotus ostreatus culture after two weeks: (a) side view; (b) view from above.

In the case of Pleurotus eryngii (Figure 2a) and Lentinula edodes (Figure 2b), intense mycelium growth was also observed in the second week, with visible penetration of the substrate.

Figure 2.

View after two weeks of incubations: (a) view from above of Pleurotus eryngii culture; (b) view from above of Lentinula edodes culture.

A full cycle of mycelium development with fruiting bodies was achieved for Pleurotus ostreatus, which began forming its first fruiting bodies in the third week of cultivation (Figure 3a) and continued producing them until the end of the cultivation period. By the fifth and sixth weeks, the fruiting bodies had fully grown (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Pleurotus ostreatus culture: (a) view from above after 3 weeks of incubation; (b) view from behind after 6 weeks of incubation.

3.2. Physicochemical Properties of Extracts

3.2.1. Reducing Sugars Content

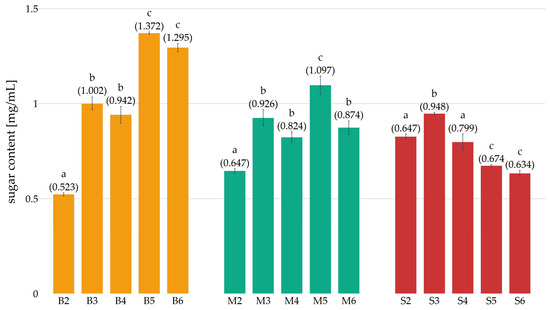

In consideration of the properties of isolated enzymes, it was determined that these enzymes, as a consequence of decomposition reactions in the cellulose substrate, resulted in the production of glucose, amongst other products. Consequently, the concentration of glucose in the obtained native preparations was analysed in subsequent weeks of cultivation. This enabled us to mitigate the impact of sugars present in the preparation on the result of the cellulolytic activity determination, which is directly related to the amount of glucose produced in the reaction with CMC (carboxymethylcellulose). Consequently, cellulolytic activity was determined based on the net amount of glucose. The results of the sugar content determinations are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Glucose content in preparations obtained in subsequent weeks of cultivation (B—Pleurotus ostreatus, M—Pleurotus eryngii, S—Lentinula edodes, the numbers next to the letters indicate the week of cultivation from which the preparation was obtained). Error bars represent standard deviation. a–c—differences between the mean values (given in parentheses) marked with letters are statistically significant.

It was observed that in preparations obtained from Pleurotus ostreatus cultures (Figure 4), the glucose concentration increased during the substrate colonization process in weeks 2 and 3 (preparations B2 and B3), and then decreased slightly in week 4 of cultivation (B4). This decline is likely attributable to the onset of fruiting. In weeks 5 and 6 (B5 and B6), there was an additional increase in glucose concentration, accompanied by intense fruiting. The increase in reducing sugar content in the substrate during primordium development in Pleurotus ostreatus has been confirmed by studies [26]. However, in contrast to the findings of these studies, no decline in sugar content was observed during fruiting body growth weeks 5 and 6 (B5 and B6). This discrepancy may be attributable to variations in fruiting intensity and substrate composition. In the course of the subsequent weeks of Lentinula edodes culture (Figure 4), a downward trend was observed from the 4th to the 6th week (S4–S6). Conversely, in preparations from Pleurotus eryngii cultures (Figure 4), no decline in glucose concentration was observed, which may suggest poor assimilation by the mycelium from week 4 (S4) onwards. A comparison of the glucose concentration produced in the culture medium as a result of enzymatic hydrolysis and still present in the obtained preparations reveals a limitation of the process after a certain concentration has been reached. This phenomenon can be attributed to the saturation of the medium with a factor, namely glucose, which, as demonstrated in the study of [27], affects the metabolic activity of the mycelium by inhibiting the synthesis of cellulolytic enzymes.

3.2.2. Cellulolytic Activity

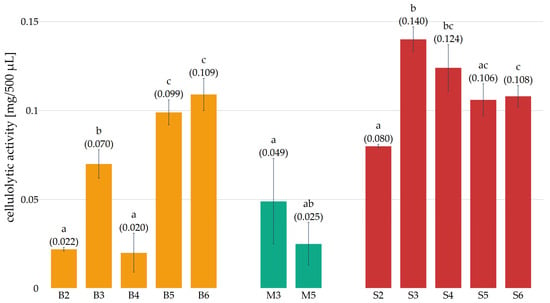

The measurement of cellulolytic activity (Endo-β-1,4-glucanase) was determined by the amount of glucose (in milligrams) produced in the reaction with CMC for 500 microlitres of each of the analysed preparations. The results are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Cellulolytic activity (mg net glucose/500 µL) of preparations obtained in subsequent weeks of cultivation (B—Pleurotus ostreatus, M—Pleurotus eryngii, S—Lentinula edodes, the numbers next to the letters indicate the week of cultivation from which the preparation was obtained). Error bars represent standard deviation. a–c—differences between the mean values (given in parentheses) marked with letters are statistically significant.

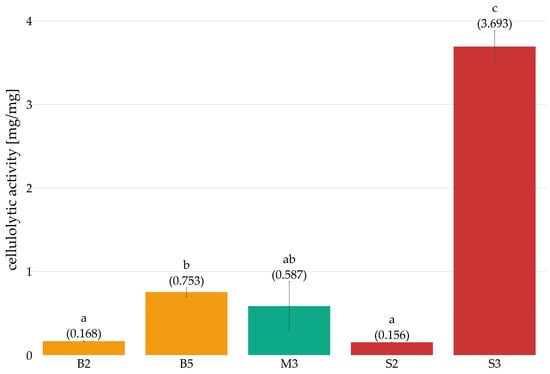

Cellulolytic activity was observed in the cultures of Pleurotus ostreatus and Lentinula edodes at each measurement point. In contrast, Pleurotus eryngii only exhibited such activity in preparations obtained in the second and fifth weeks. For all preparations, it was concluded that cellulolytic activity increased between the second and third weeks of cultivation. Over the subsequent 4–6 weeks of Pleurotus eryngii and Lentinula edodes cultivation, the activity of the preparations remained similar or decreased, potentially due to a metabolic slowdown resulting from the complete colonization of the substrate and the absence of fruiting bodies. In the case of P. ostreatus, cellulolytic activity decreased in the fourth week compared to the third, while a marked increase was observed in the fifth and sixth weeks, which may be related to the start of fruiting body formation. These observations are consistent with the results presented by [28], who demonstrated an increase in the cellulolytic activity of enzyme preparations during the fruiting phase of the mycelium. For the purpose of further analysis, the first preparation obtained with cellulolytic activity and the preparation with the highest cellulolytic activity, as indicated by statistical analysis, were selected from the Pleurotus ostreatus and Lentinula edodes cultures. In the case of Pleurotus eryngii, however, the preparation exhibiting the highest activity was selected. Following the conversion of cellulolytic activity to protein content in the preparations (Figure 6), it was determined that the preparation obtained in the third week of Lentinula edodes cultivation exhibited the highest activity, reaching a value of 3.693 ± 0.193 mg glucose/mg protein. Significantly lower activity values were observed in preparations derived from the cultures of Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus eryngii. For P. ostreatus, the maximum activity was 0.753 ± 0.053 mg glucose/mg protein in the fifth week of cultivation, and for P. eryngii, it was 0.587 ± 0.290 mg glucose/mg protein in the third week. In light of those results, the preparations exhibiting the highest activity were selected for further analysis and subjected to a salting-out process for precipitation.

Figure 6.

Cellulolytic activity (mg net glucose/mg protein) of preparations obtained in subsequent weeks of cultivation (B—Pleurotus ostreatus, M—Pleurotus eryngii, S—Lentinula edodes, the numbers next to the letters indicate the week of cultivation from which the preparation was obtained). Error bars represent standard deviation. a–c—differences between the mean values (given in parentheses) marked with letters are statistically significant.

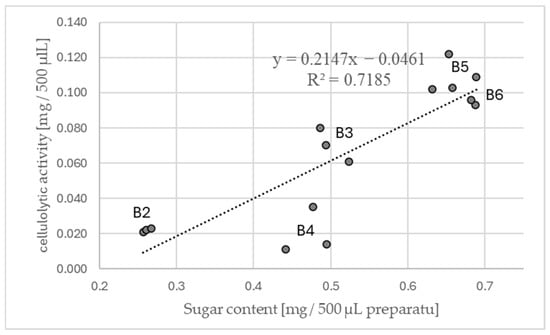

In view of the observed correlation between the fruiting phase and increased cellulolytic activity, an attempt was made to assess the existence of a linear relationship between cellulolytic activity and the concentration of glucose released into the culture medium. The hypothesis that such a relationship is justified is substantiated by the close correlation between metabolic intensity, including enzymatic activity, and the dynamics of mycelium growth, which is particularly evident during the fruiting body formation period. It is notable that the studied cellulolytic enzymes catalyse the hydrolysis of polysaccharides, resulting in the release of glucose. Consequently, the concentration of glucose in the medium may serve as an indicator of the level of enzymatic activity, provided that no factors limit the organism’s growth. The employment of this methodology has the potential to facilitate a rapid determination of the most opportune moment for enzyme extraction sampling, at which point the cellulolytic activity of the enzymes reaches its zenith, obviating the necessity for extended periods of incubation (as is the case in the CMC reaction).

Among all the preparations, a promising relationship was identified (Figure 7). The coefficient of determination of cellulolytic activity from glucose concentration was obtained for the preparations obtained from Pleurotus ostreatus cultures. This phenomenon is likely attributable to the pronounced growth dynamics observed throughout the entire cultivation period. As demonstrated in Figure 7, there was an increase in the cellulolytic activity of preparations B2 and B3, concomitant with the colonization of the substrate by fungi and during intense fruiting (preparations B5 and B6). The only cultivation period that deviates from this trend is the preparation obtained in the fourth week of cultivation (the beginning of fruiting).

Figure 7.

Linear model of the change in cellulolytic activity depending on glucose concentration in the obtained preparations of Pleurotus ostreatus—B, numbers next to the letters indicate the week of cultivation (from which the preparation was obtained).

A comparison of the protein concentration in native preparations obtained directly from the culture medium, salted preparations (B5W—2.639 ± 0.584 mg/mL, M3W—3.358 ± 0.403, S3W—0.756 ± 0.055) and commercially available cellulase (KE—113.22 ± 2.307 mg/mL) reveals that the protein concentration in commercial cellulase is several dozen times higher (Table 1). This result may be indicative of a high protein concentration in the commercial preparation, or the presence of proteins other than those of an enzymatic nature.

Table 1.

Protein concentration in the obtained preparations and commercial preparation.

Different kinetics were observed in the extracted protein concentration: over the course of subsequent weeks of cultivation, the amount decreased for Lentinula edodes (S2, S3) and Pleurotus eryngii (M2, M3), while for Pleurotus ostreatus (B2, B5), it fluctuated around a constant value. This relationship can be interpreted in light of the rate of substrate colonisation. P. ostreatus, which is characterised by the fastest growth rate and is the only species to produce fruiting bodies, exhibited the lowest initial protein content. This suggests that the rapid consumption of proteins from the substrate balances their secretion. The lower protein content of P. eryngii (the second fastest grower) in the second week compared to the slower-growing L. edodes further supports the conclusion that the higher protein content observed in P. eryngii and L. edodes in the early phase (week 2) may be derived from the substrate rather than being secreted by the fungi.

The protein content of the native preparations was converted to milligrams per gram of the substrate from which they were extracted. A comparison with the work [16], in which P. ostreatus and P. eryngii were cultivated on a complex substrate consisting of 4.1% wheat straw, 4.1% corn chips, 4.1% thistle chips, 4.1% spelt chaff, 15% beet pulp and 3.6% CaCO3 at a substrate moisture level of 65%, showed that the protein content of the extract (P. ostreatus—B5) after 30 days of cultivation (1.32 ± 0.29 mg/g) is similar to the value of 1.79 ± 0.14 mg/g obtained in the aforementioned study after 34 days. However, for the M3 preparation (P. eryngii), our value of 0.840 ± 0.100 mg/g after 21 days was lower than the value of 1.33 ± 0.11 mg/g obtained after 23 days in publication [16]. We attribute the difference in results for P. eryngii to different substrate compositions resulting in different growth rates and mycelium metabolism.

The present study investigates the applicability of enzymes obtained from basidiomycota cultures with a particular focus on the activity of salted preparations in comparison with commercial cellulase. In order to evaluate the cellulolytic activity of all enzyme preparations obtained. It was planned to determine activity curves in accordance with the methodology described by [26]. The activity was hypothesised to be determined as the volume of the enzyme preparation at which 0.5 mg of glucose is released. However, due to the non-linear nature of the enzyme reaction curves obtained, it was not possible to determine this parameter in accordance with the assumptions. Therefore, for the purpose of comparing preparations obtained by the salting-out method with a commercial enzyme, the unit of activity was taken as the amount of glucose (in milligrams) released from the reaction with CMC per 100 microlitres of preparation then converted to the protein content (in milligrams) in a given extract. The activity determined in this manner (Figure 8) revealed that two preparations exhibited higher cellulolytic activity in comparison to the commercial enzyme (KE). The most intense activity was observed in preparation derived from the culture of Lentinula edodes (designation S3W) and Pleurotus ostreatus (B5W).

Figure 8.

Comparison of the cellulolytic activity of salted extracts with commercial cellulase (KE—commercial enzyme. B5E—salted out preparation obtained from five-week culture of Pleurotus ostreatus. M3E—salted out preparation obtained from three-week culture of Pleurotus eryngii. S3E—salted out preparation obtained from three-week culture of Lentinula edodes). Error bars represent standard deviation. a–c—differences between the mean values (given in parentheses) marked with letters are statistically significant.

Conversely, the preparation obtained from the culture of Pleurotus eryngii (M3W) exhibited activity that was statistically analogous to that of commercial cellulase. The observed discrepancies in activity among the tested preparations may be attributable to varying concentrations of cellulolytic enzymes, varying substrate specificity (CMC), and the presence of other proteins with non-cellulolytic activity. The results obtained are promising and indicate the potential of selected basidiomycete species as a source of cellulolytic enzymes for biotechnological applications. In addition, they point to the possibility of effectively using organic waste as a cheap, sustainable source of substrate for the production of valuable enzymes.

However, it is crucial to develop efficient and inexpensive production by optimizing the components of the culture medium (inducers), process parameters, and process control.

It is also advisable to conduct research aimed at optimizing the extraction process (selection of more effective solvents, modification of physicochemical parameters, improvement of separation, and purification procedures).

Increasing the extraction efficiency would not only allow for fuller utilization of the potential of the developed substrate but also increase the competitiveness of the obtained enzyme preparations against commercial products.

4. Conclusions

A waste substrate consisting of coffee grounds (70%) and wood chips (30%) can be used to obtain cellulolytic enzyme preparations during the cultivation of basidiomycetes. The species under consideration are Pleurotus ostreatus, Pleurotus eryngii, and Lentinula edodes. These results open up new perspectives for the utilization of coffee grounds, a waste product obtained after brewing coffee. Macroscopic observation of Pleurotus ostreatus cultures and evaluation of the cellulolytic activity of these preparations indicate that the fruiting period is the moment of increased enzymatic activity. The study demonstrated a correlation between the cellulolytic activity of Pleurotus ostreatus and the glucose concentration in the substrate. This finding suggests a promising methodology for identifying the optimal cultivation time of Pleurotus ostreatus to maximize the yield of high-cellulolytic-activity extract based on monitoring substrate sugar levels. However, this preliminary suggestion requires further research and verification to confirm its reliability and applicability as a predictive model. Enzyme preparations obtained from Pleurotus ostreatus and Lentinula edodes cultures, precipitated by salting, exhibited higher cellulolytic activity per protein content than commercial cellulase (obtained from Trichoderma reesei). Consequently, the preparations obtained may serve as a promising alternative to commercial cellulase. In view of the research findings. efforts must be made to enhance the efficiency of enzyme extraction from the substrate developed in the study. For complete success, it is advisable to take further steps aimed at optimizing the extraction process (selection of more effective solvents, modification of physicochemical parameters, improvement of separation and purification procedures).

Increasing the extraction yield would not only enable the fuller utilization of the developed substrate’s potential but also enhance the competitiveness of the obtained enzyme preparations against commercial products.

By using less conventional fungi, a unique set of enzymes can be obtained. It is therefore necessary to conduct research aimed at characterizing their enzymatic profiles.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N. and E.L.; Methodology, M.N. and E.L.; Formal analysis, E.L.; Investigation, M.N.; Writing—original draft, M.N.; Writing—review & editing, E.L.; Supervision, E.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BCA | Citric acid buffer |

| CMC | Carboxymethylocellulose |

| DNS | 3.5-Dinitrosalicylic acid |

References

- Brzeska, M. Drugie Życie Kawy–Fusy Surowcem, a Nie Odpadem?–Agronomist. Available online: https://agronomist.pl/artykuly/drugie-zycie-kawy-fusy-surowcem-a-nie-odpadem (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Żygo, M.; Prochoń, M. Enzymatyczne metody otrzymywania nanowłókien celulozowych. Eliksir 2017, 1, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.M.; Ranamukhaarachchi, S.L. Study on the Mycelium Growth and Primordial Formation of King Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus eryngii) on Cardboard and Spent Coffee Ground. Res. Crops 2019, 20, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcina, A.; Petrillo, A.; Travaglioni, M.; di Chiara, S.; De Felice, F. A Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Different Spent Coffee Ground Reuse Strategies and a Sensitivity Analysis for Verifying the Environmental Convenience Based on the Location of Sites. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 385, 135727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, D.; Wösten, H.A.B. Mushroom Cultivation in the Circular Economy. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 7795–7803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhevagi, P.; Ramya, A.; Priyatharshini, S.; Geetha Thanuja, K.; Ambreetha, S.; Nivetha, A. Industrially Important Fungal Enzymes: Productions and Applications. In Recent Trends in Mycological Research: Volume 2: Environmental and Industrial Perspective; Yadav, A.N., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 263–309. ISBN 978-3-030-68260-6. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.-M.; Han, S.-S.; Kim, H.-S. Industrial Applications of Enzyme Biocatalysis: Current Status and Future Aspects. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 1443–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.; Guo, G.S.; Ren, G.H.; Liu, Y.H. Production, Characterization and Applications of Tannase. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2014, 101, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezudo, I.; Galetto, C.S.; Romanini, D.; Furlán, R.L.E.; Meini, M.R. Production of Gallic Acid and Relevant Enzymes by Aspergillus Niger and Aspergillus Oryzae in Solid-State Fermentation of Soybean Hull and Grape Pomace. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2023, 13, 14939–14947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Deng, W.; Wang, Z.; Weng, C.; Yang, Y. Effective Decolorization and Detoxification of Single and Mixed Dyes with Crude Laccase Preparation from a White-Rot Fungus Strain Pleurotus Eryngii. Molecules 2024, 29, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, P. Microbial Biotechnology: An Interdisciplinary Approach; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4987-5677-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sureshkumar, S.; Song, J.; Sampath, V.; Kim, I. Exogenous Enzymes as Zootechnical Additives in Monogastric Animal Feed: A Review. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayum, A.; Ahmad, M.T.; Anjum, M.G.; Sulamani, M. Probiotics and Innovative Feed Additives for Optimal Gut Health. In Gut Heath, Microbiota and Animal Diseases; Unique Scientific Publishers: Faisalabad, Pakistan, 2024; pp. 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metreveli, E.; Khardziani, T.; Elisashvili, V. The Carbon Source Controls the Secretion and Yield of Polysaccharide-Hydrolyzing Enzymes of Basidiomycetes. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Yan, P.; Leng, D.; Shang, L.; Zhang, C.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Z. Functional Roles of LaeA-like Genes in Fungal Growth, Cellulase Activity, and Secondary Metabolism in Pleurotus Ostreatus. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petraglia, T.; Latronico, T.; Liuzzi, G.M.; Fanigliulo, A.; Crescenzi, A.; Rossano, R. Hydrolytic Enzymes in the Secretome of the Mushrooms P. Eryngii and P. Ostreatus: A Comparison Between the Two Species. Molecules 2025, 30, 2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okereke, O.E.; Akanya, H.O.; Egwim, E.C. Purification and Characterization of an Acidophilic Cellulase from Pleurotus Ostreatus and Its Potential for Agrowastes Valorization. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2017, 12, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royse, D.J.; Baars, J.; Tan, Q. Current Overview of Mushroom Production in the World. In Edible and Medicinal Mushrooms; Diego, C.Z., Pardo-Giménez, A., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 5–13. ISBN 978-1-119-14941-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.-H.; Lee, Y.-H.; Kang, H.-W. Efficient Recovery of Lignocellulolytic Enzymes of Spent Mushroom Compost from Oyster Mushrooms, Pleurotus Spp., and Potential Use in Dye Decolorization. Mycobiology 2013, 41, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanaka, K. Cultivation of Mushrooms in Plastic Bottles and Small Bags. In Edible and Medicinal Mushrooms; Diego, C.Z., Pardo-Giménez, A., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 309–338. ISBN 978-1-119-14941-5. [Google Scholar]

- Nakano, Y.; Fujii, H.; Kojima, M. Identification of Blue-Light Photoresponse Genes in Oyster Mushroom Mycelia. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2010, 10, 2160–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luz, J.M.R.D.; Nunes, M.D.; Paes, S.A.; Torres, D.P.; Silva, M.D.C.S.D.; Kasuya, M.C.M. Lignocellulolytic Enzyme Production of Pleurotus Ostreatus Growth in Agroindustrial Wastes. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2012, 43, 1508–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toczko, M.; Grzelińska, A.; Andrzejczuk-Hybel, J. Materiały Do Ćwiczeń z Biochemii; Wydawnictwo SGGW: Warsaw, Poland, 1997; ISBN 83-00-02775-0. [Google Scholar]

- Piecyk, M.; Wołosiak, R.; Cienkusz, A. (Eds.) Analiza i Ocena Jakości Żywności, 1st ed.; Wydawnictwo SGGW: Warsaw, Poland, 2022; ISBN 978-83-8237-137-6. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, T.; Bhat, M. Methods for Measuring Cellulase Activities. Methods Enzymol. 1988, 160, 87–112. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Ma, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J. Carbohydrate Changes during Growth and Fruiting in Pleurotus Ostreatus. Fungal Biol. 2016, 120, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfaro, M.; Majcherczyk, A.; Kües, U.; Ramírez, L.; Pisabarro, A.G. Glucose Counteracts Wood-Dependent Induction of Lignocellulolytic Enzyme Secretion in Monokaryon and Dikaryon Submerged Cultures of the White-Rot Basidiomycete Pleurotus Ostreatus. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elisashvili, V.; Chichua, D.; Kachlishvili, E.; Tsiklauri, N.; Khardziani, T. Lignocellulolytic Enzyme Activity During Growth and Fruiting of the Edible and Medicinal Mushroom Pleurotus Ostreatus (Jacq.:Fr.) Kumm. (Agaricomycetideae). Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2003, 5, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).