Abstract

Osteoarthritis is a common joint disease mainly characterized by inflammation and pain. Some promising approaches are aimed at combating the general mechanisms of osteoarthritis development and progression by targeting specific molecules. Although scientific and clinical communities remain skeptical regarding the efficacy of nutrition in managing human diseases, several products have been recognized as capable of improving health conditions and counteracting specific chronic and inflammatory musculoskeletal disorders such as osteoarthritis. The aim of this narrative review is to present the results obtained by a search through electronic databases on the effect of glucosinolates and their breakdown products, in particular isothiocyanates, in both the prevention and complementary therapy for osteoarthritis. Even if we found a few studies on this topic, some preclinical studies demonstrated an active role of these compounds in reducing inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis. A beneficial effect of a diet rich in glucoraphanin, a glucosinolate derivative, has been associated with a lower risk of developing osteoarthritis in a proof-of-principle trial. To further advance this topic, it is essential to conduct additional preclinical studies to address existing research gaps, alongside more rigorous clinical investigations, especially long-term randomized controlled trials. These efforts should focus on determining the most effective type of glucosinolate and relative metabolites in counteracting osteoarthritis progression and identifying their dose–response behavior to assess both benefits and side effects associated with their oral intake.

1. Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a chronic, progressive, debilitating, and painful joint disease of unknown etiology characterized by gradual degradation of articular cartilage, subchondral bone damage, synovial inflammation and pain, resulting in significant disability in the elderly population. A combination of several risk factors contributes to its onset, with the most prominent being age, female gender, and obesity [1]. From a pathogenetic perspective, the degenerative process involves all joint tissues, particularly cartilage. This translates clinically into pain, functional impairment, stiffness, and even disability, explaining the significant socioeconomic impact of this condition [2].

An increased understanding of human-relevant OA biomolecular mechanisms has been observed in recent years. This progress has led to the recognition of OA as a whole joint disorder involving molecular and mechanical crosstalk among multiple joint tissues and supports a growing recognition of the “systemic” aspect of this pathology [3].

The diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical history and radiological examinations, which enable an accurate assessment of disease severity based on the presence of characteristic lesions and joint deformities [4]. Therapeutic approaches can be implemented to slow down OA progression, control pain and disability, and postpone joint replacement surgery. However, complete joint restoration is unlikely in the absence of an effective disease-modifying therapy aimed at targeting specific mechanisms of OA development and progression [4].

Orthobiologics therapies are a promising modality to be included in the treatment selection for OA. Several products are presently utilized in clinical practice as injectable treatments, ranging from blood derivatives to cellular therapies [5]. These treatments seem safe and present encouraging outcomes, with success inversely proportional to OA severity [6]. Nevertheless, as of today, orthobiologics have not yet been integrated into the established standard treatment guidelines for OA. This method is not intended to replace existing therapy but rather to serve as an intermediate intervention [7].

Although scientific and clinical communities remain skeptical regarding the efficacy of nutrition in managing human diseases, several products have been recognized as capable of improving health conditions and counteracting specific chronic and inflammatory musculoskeletal disorders such as OA.

Indeed, recent studies increasingly examined the role of nutrition as an accessible reservoir of antioxidant compounds, relevant to both maintaining human wellness and mitigating the risk of illness [8].

Functional foods provide health advantages that extend beyond basic nutrition, thanks to the ability of some molecules to influence cartilage metabolism, target inflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and tissue homeostasis, thereby enabling symptom management, outcomes improvement, and overall quality of life enhancement [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

Among all dietary options, vegetables include components such as fibers, vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients such as glucosinolates (GSLs), which have been shown to have beneficial effects in the management of a range of diseases [18].

These bioactive compounds have the potential to reduce inflammation and oxidative stress by acting at various and complementary levels, such as promoting detoxification by enzymes, neutralizing free radicals, and enhancing immune function. Considering that many of these molecular mechanisms are common within chronic degenerative/inflammatory diseases such as OA, an in-depth evaluation of the roles of GSLs and their metabolic products may suggest their use in this rheumatic disease [1].

Unlike vitamins and traditional antioxidants, phytonutrients like isothiocyanates (ITCs), the metabolic products of GSLs, act systematically on transcriptional and enzymatic pathways modulating inflammation and exerting cytoprotective effects. This mode of action positions GLS-rich foods as “cellular signaling modulators”, offering multi-layered protection for OA.

The objective of this narrative review is to provide an overview of the benefits of GSLs, and especially their metabolite ITCs, in both the prevention and therapeutic management of OA.

2. Methods

We run the search through the electronic databases PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar from 1 to 25 November 2025. Since this is an emerging area of research, we included all study designs (in vitro cell models, in vivo animal models, and clinical trials involving humans), study types (scientific articles, books, abstracts with no full-text availability), study languages, publication dates, and peer-reviewed status. Search terms included the keywords “glucosinolates”, “isothiocyanates”, “cruciferous”, osteoarthritis, “cartilage, bone”, “synovium”, “prevention”, and “risk factors”. We also combined the keywords with Boolean operators, for examples “glucosinolates” AND cruciferous”; “glucosinolates” AND Osteoarthritis”; “cruciferous” AND Osteoarthritis;” “glucosinolates” AND “breakdown products”; “cruciferous” AND “glucosinolates” AND “osteoarthritis”; “glucosinolates” AND “cartilage” AND osteoarthritis; “glucosinolates” AND “bone” AND osteoarthritis; “glucosinolates” AND “synovium” AND osteoarthritis; “glucosinolates” AND “osteoarthritis” AND “prevention”. We used synonym, especially for the term “cruciferous”, like “cruciferous plants” cruciferous vegetable”, “Cruciferae”, Brassicaceae, Brassica vegetables, etc. To build the Tables, we combined the name of each Cruciferous vegetable with “glucosinolates and their breakdown products”. Further, we checked the bibliographies of some key papers for additional relevant studies.

This narrative review, which details the potential molecular mechanisms underlying GLSs and their breakdown products, may help clinicians in giving indications regarding the inclusion of these compounds in dietary regimens for OA patients.

3. Glucosinolates

3.1. Chemical Structure and Classification

GSLs (S-β-thioglucoside N-hydroxysulfate) are glycosides characterized by a low molecular weight, water-solubility and sulfur-content, and are synthesized as secondary metabolites in herbaceous plants belonging to the Capparales and Brassicales orders and to a lesser extent, in the Moringaceae family [19,20].

Based on the side chain of the amino acids (R group), there are three primary categories of GSLs: (i) aliphatic, derived from methionine, alanine, leucine, isoleucine, and valine; (ii) aromatic, originating from phenylalanine or tyrosine; and (iii) indole, which comes from tryptophan [21].

3.2. Biosynthesis, Storage, and Degradation

GLSs are constitutive components whose biosynthesis occurs mainly in the leaves, flowers, seeds, and roots of plants. The content of GSLs differ not only among various plant species but also between different regions of the same plant [22,23]. GSLs are typically stored in the vacuoles, functioning as a storage site for sulfur, an essential element. After damage, myrosinases, which are thioglucosidases (thioglucoside glucohydrolases, EC 3.2.1.147), come into play through the hydrolysis of the thioglucosidic bond of GSLs from which they had been endogenously separated by compartmentalization or chemical inactivation. Specialized cell types, S-cells for GSLs and myrosin cells for myrosinases [24], spatially separate those enzymes from their substrates, allowing them to only come into contact when the plant is stressed or damaged, at which point they can interact. As a result, a variety of products like ITCs, nitriles or epithionitriles (ETNs), indole-3-carbinol (I3C), and 3,3′-diindolylmethane (DIM) are released, which possess specific bioactivities [25].

ITCs are part of the plant’s immune system, protecting against pathogens and pests [26]. The types of hydrolysis products depend on various factors such as pH, ferrous ion availability, the chemical nature of the side chain, and epithiospecifier proteins, which are iron-dependent cofactors of myrosinase [25].

3.3. Natural Occurrence

The Brassicaceae family is globally distributed and includes numerous economically important and widely consumed vegetables. It comprises more than 300 genera and approximately 4000 species [26,27].

Type (side chain) and amount of GSLs in those plants depend on different factors: (i) genetics (families and species), (ii) plant development (age), (iii) plant part (leaves, roots, seeds, sprouts, or flowers having different physiological mechanisms), (iv) environmental factors (weather conditions, light, water availability, infections, wounding, and insects or pests damage), (v) crop management (soil type and nutrients) [28]. Table 1 summarizes the common names and botanical classification of Brassicaceae consumed for their GSL content.

Table 1.

Common names and botanical classification vegetables consumed for the glucosinolate content.

3.4. Breakdown Products of Glucosinolates

The specific side chain of the GSL molecules dictates the final breakdown products formed when the plant is damaged, such as ITCs, nitriles, and thiocyanates (Table 2).

Table 2.

Glucosinolates breakdown products formed when the plant is damaged.

3.5. Bioavailability and Absorption

Dietary intake of Brassicaceae increases the body’s availability of GSLs. Chewing fresh cruciferous vegetables activates myrosinase, which breaks down GSLs into products in the proximal small intestine, which are then absorbed in the colon. Salivary enzymes have no impact on GSL metabolism in the mouth, and there are no enzymatic hydrolysis reactions in the stomach. While a small amount of GSLs is absorbed intact, the majority are released into the intestinal lumen [56].

Human consumption of Brassica vegetables predominantly occurs after cooking. Myrosinase inactivation occurs in cooked plants, particularly at high temperatures. The colon is where intact GSLs are broken down by various bacterial enzymes in the gut microbiota, including those of Enterococcus, Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Bacteroides species. Many of the metabolites produced by this process are still unidentified [56,57]. Otherwise, intact GSLs enter the bloodstream, possibly via passive diffusion or facilitated transport through enterocytes [20].

The bioavailability pathways of ICTs have been evaluated in different studies. The liver conjugates ITCs to glutathione and excretes them as mercapturic acid (N-acetyl-S-(N-alkylthiocarbamoyl)-l-cysteine) as part of 12–80% of the dose taken. In humans, mercapturic acid formation is the most common metabolic pathway and is used as a biomarker of food intake and/or ITC formation in the body. ITCs can also follow minor excretion routes. The mechanism by which the body assimilates other GSL breakdown products remain unclear [20].

The metabolism and excretion of nitriles and epithionitriles in urine are like those of ITCs, and they can be excreted as mercapturic acids. Oxazolidine-2-thione and thiolate ion are excreted directly. The contributions of myrosinase and the intestinal microbiota to the hydrolysis of GSLs affect the bioavailability of ITCs [58].

GSL levels can be significantly influenced by industrial or domestic food processing. It is necessary to consider multiple factors, such as post-harvest storage, preparation, and processing. The main influencing parameters are post-harvest storage time, temperature, and the packaging atmosphere [59]. Finding a balance between steaming and generating breakdown products to enhance the flavors of commercialized foods is necessary, while also avoiding myrosinase inactivation. Culinary processing can affect the absorption of GSLs and their breakdown products, depending on temperature and the heating method used, such as cooking, steaming, microwave cooking, or radiofrequency cooking. The most efficient heat treatment is steaming, which preserves high GSL content (depending on prior culinary preparations, like cutting) and inactivates myrosinase [40].

4. Results from Literature Search

Our search revealed 45 scientific articles, 3 book chapters, 20 review/systematic reviews). Of the 45 scientific articles, 23 reported the composition of each Cruciferous plant listed in Table 1, allowing the setup of Table 2. One of these articles was written in Chinese, except for the abstract, which was in both English and Chinese; the English version was sufficient to obtain the information we needed. Of the other 22 articles, 2 were in vitro studies, 4 in vivo investigations and 3 clinical studies (both proof-of-principle). One clinical study was posted as a preprint on 21 June 2024. The remaining 13 articles were utilized to write the other parts of the review. The 10 reviews found helped in checking for more research papers.

Data collected showed that most of the scientific evidence is related to ITCs showing their active role in OA [60,61].

5. Mechanisms of Action and Role of GLS-Derived ITC Intake in OA

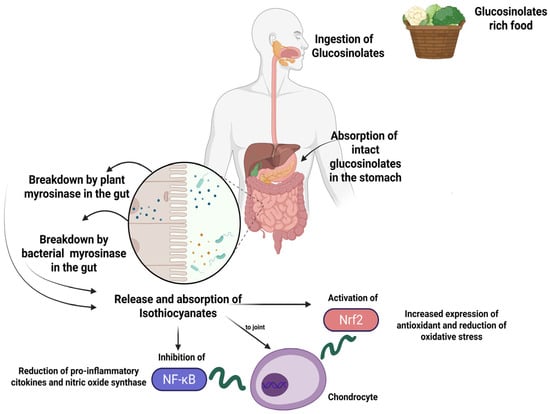

As reported above, slicing, dicing, or blending plants containing GSLs activates the enzyme myrosinase both of plant and bacterial origin [24], mainly responsible of the production of metabolite products [56]. GSLs’ profile in a Cruciferous plant dictates the biological effects when consumed by humans. Of these, SFN, found mainly in broccoli, has been demonstrated to have a broad biological activity, and its role in joint health was recently reviewed [62]. SFN has been studied for its potential benefits in OA due to its reported antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the mechanism of GSL intake and one of the main and most studied mechanisms of action of their breakdown products, namely SFN. After ingestion, intact GSLs may be partially absorbed in the stomach, while the rest moves through the gastrointestinal tract to the small intestine, where plant-derived myrosinase can hydrolyze them into isothiocyanates which are then absorbed. The GSL s that remain non-hydrolyzed reach the colon, where they can be broken down by bacterial myrosinase, with the resulting breakdown products either absorbed or excreted. Isothiocyanates act on joint compartment inhibiting NF-kB or activating Nrf2 pathways, thus modulating key inflammatory and antioxidant activities. Created in BioRender. Roseti, L. (2025) https://BioRender.com/n1buj9u.

The initial well-structured investigation examining the possible advantages of SFN in OA was released in 2013. In this study, it has been demonstrated that SFN can repress the expression of key metalloproteinases implicated in OA, regulate NF-κB and Nrf2 signaling, inhibit production of prostaglandin E2 and nitric oxide in chondrocytes, prevent cytokine-induced cartilage destruction, and finally is responsible for joint degeneration both in vitro and in vivo [62,63].

5.1. In Vitro Studies

Most in vitro studies focused on the OA setting, have primarily examined SFN, one of the most studied ITC compounds. The first evidence of SFN’s potential protective effects on joints emerged in 2009 from Kim’s research group, which demonstrated that SFN increased the activity of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 in chondrocytes and decreased the synthesis of matrix metalloproteinase-1, -3, and -13 in chondrocytes stimulated by proinflammatory cytokines. These findings provided evidence of SFN’s ability to counteract the degradative enzymes that contribute to cartilage destruction [64].

Interestingly, Chen M. et al. explored two key aspects: (i) the viability of chondrocytes exposed to various amounts of SFN (12.5–200 μM) using the Cell Counting Kit-8 assay; and (ii) its impact on H2O2-induced apoptosis in mouse chondrocytes, evaluated through the TUNEL assay along with sirtuin 1 (SIRT-1) silencing studies using small interfering RNA [65]. SIRT-1 exerts a relevant role in managing oxidative stress within the articular environment by activating oxidative responses and enhancing mitochondrial functions, thus contributing to maintaining articular joint health [66]. This study offered valuable insights, revealing that (i) concentration of SFN above 100 μM is cytotoxic, and (ii) SFN exhibits anti-apoptotic effects by down-regulating typical apoptotic markers, such as Bax, Cleaved caspase-3, while also activating SIRT-1. Indeed, this study provides important insights into the cytotoxic threshold of this compound on chondrocytes, laying the basis for further in-depth studies.

Further evidence of SFN’s benefits comes from Davidson’s group, which conducted a more in-depth analysis on the synovial membrane, a major anatomical site with an active role in the OA setting. By using various culture systems that included both articular chondrocytes and cell populations from the synovial membrane, they demonstrated anti-inflammatory and chondroprotective effects of SFN. SFN treatment inhibited the IL-1/NFκB and Wnt3a/TCF/Lef pathways while enhancing TGFβ/Smad2/3 and BMP6/Smad1/5/8 signalling. This indicated that SFN acts as a modulator of cartilage homeostasis. Moreover, a concentration of 10 μM of this compound was effective in blocking cytokine-induced proteoglycan and collagen breakdown in a bovine nasal cartilage explant model [62].

Along this vein, Ko JY et al. introduced an innovative system that encapsulates SFN within microspheres made of polylactic acid (PLGA), proposing it as a potential intra-articular delivery system for OA treatment. This study demonstrated the anti-inflammatory effects of the system, which resulted in the downregulation of specific metalloproteinases and aggrecanases involved in cartilage degradation, as evidenced by both gene and protein expression analyses [67].

5.2. In Vivo Studies

Chondrocyte apoptosis is one of the pathogenic mechanisms of OA and is viewed as a potential therapeutic target. In an experimental OA model induced by destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM), the intra-peritoneal administration of SFN (20 mg/kg; every 2 days for 8 weeks) effectively inhibited OA progression by reducing cartilage degradation and synovitis, as evidenced by lower Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) and synovitis score compared to the DMM group. Moreover, immunohistochemical analyses revealed SIRT-1 positive cells in cartilage samples, indicating the protective role of SFN on chondrocytes [65].

Davidson et al. used a DMM model of OA in C57BL/6 mice which demonstrated that a SFN-rich diet (3 μmoles/day) led to a significant reduction in cartilage destruction, as evidenced by histological analyses at 12-week follow-up [62]. While these findings are noteworthy, they raise several critical aspects that require further investigation. The specific mechanisms by which SFN exerts its protective effects on cartilage remain poorly understood, necessitating a deeper exploration of the underlying biological pathways involved. Additionally, the study’s reliance on a single dietary dosage may overlook potential dose–response relationships and the effects of long-term SFN intake.

Employing a post-traumatic model of OA (anterior cruciate ligament transection (ACL) in Sprague-Dawley rats), Ko JY et al. highlighted the potential of utilizing SFN as an intra-articular (IA) delivery method, either through its combination with fibrin glue or encapsulation in PLGA microspheres (SFN-PLGA) [67]. This study demonstrated that the IA delivery of SFN-PLGA effectively reduced cartilage destruction, proteoglycan loss, and synovial inflammation. This presents opportunities for future research to explore not only the long-term impacts of intra-articular SFN delivery but also its potential synergistic effects with other therapeutic agents. Another interesting preclinical study explored the effects of a synthetic form of SFN, SFX-01 (100 mg/Kg; administered orally for 3 months), on bone architecture, cartilage destruction and gait in a spontaneous model of OA using STR/Ort mice. Gait analysis results indicated asymmetries typical of OA in vehicle-treated STR/Ort mice, but not in those treated with SFN. No significant effects were, however, observed on cartilage lesions [68]. These findings suggest the potential osteotrophic benefits of this synthetic compound, indicating promising avenues for further exploration in clinical scenarios involving the bone compartment. Opportunities for future research include examining the mechanisms underlying SFX-01′s effects on bone, and gait improvement, as well as exploring different dosing regimens or combinations with other therapeutic strategies to enhance cartilage protection.

Besides its effects on the articular microenvironment, SFN has been shown to alleviate OA-related pain, primarily by modulating the inflammatory response [62]. Additionally, research studies indicate that administering SFN (5 and 10 mg/kg of SFN via intra-peritoneal administration for 11 consecutive days) can interact with opioid receptors, enhancing the analgesic effects of opioids, like morphine, in a mouse model of inflammatory pain induced by Freund’s adjuvant [69]. However, the variability of pain responses in different OA models could limit the generalizability of these results. This gap presents opportunities for future research, including investigating the precise molecular mechanisms by which SFN influences pain modulation and its potential to enhance analgesia across various pain conditions. Exploring different routes and dosing regimens of SFN, as well as its effects when combined with other pain control strategies, could provide valuable insights for more effective treatments for pain management in OA and related disorders.

5.3. Clinical Studies

Some epidemiological studies have examined the possible advantages of consuming broccoli and other cruciferous vegetables, given their GSL content. However, many of these investigations concentrated on cancer.

In a proof-of-principle study, titled “The Broccoli in Osteoarthritis” (BRIO Study), which is documented in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.06.20.24309233), the Authors observed clear patterns of improved pain across a range of pain measures in a two-center, double-blind, two-arm parallel, randomized placebo-controlled study. Both glucoraphanin and SFN have been shown to influence pain by activating the Nrf2 pathway, inhibiting the NF-κB signaling (a key factor in OA pathogenesis), thereby downregulating the expression of proinflammatory cytokines [70].

A proof-of-principle trial enrolled 40 patients with knee OA undergoing total knee replacement. Patients were randomized to either a low or a high GSLs diet for 14 days before surgery. ITCs were detected in the synovial fluid of the high GSLs group, but not in the low GSLs group. This was mirrored by an increase in ITCs, specifically SFN, in plasma [71]. To date, this study by Davidson et al. is one of the most explanatory studies in the field, demonstrating changes in gene expression in the joint upon high broccoli intake, which correlated to increased SFN levels in the joint. However, limitations in the study design prevented ruling out the contribution of other broccoli’s phytonutrients (such as vitamin C) and an indirect action consequent to SFN increase.

6. Challenges and Prospects

The nutritional and preventive/therapeutic value of food components is an emerging field of research. The present review stems from the increasing awareness of the link between regular consumption of GLS-rich vegetables with reduced risks of chronic diseases [60,61,72]. Despite promising results regarding oral intake of GLS and especially its metabolite, SFN, in the context of OA [62], no clinical studies specifically addressed the potential direct protective role of SFN on OA. This study intended to highlight research gaps and identify potential challenges and opportunities for effective translation applications of GLS in OA, focusing on in vitro, in vivo, and clinical research. First, in vitro preclinical models will offer interesting clues to the clinical relevance of these diet-derived compounds. It is crucial to select preclinical in vitro models that can accurately mimic the OA microenvironment, influencing tissue responses. Interestingly, the dual action of antioxidative and anti-inflammatory from in vitro models mimicking chronic pathologies, makes GLS a promising molecule for OA [73,74,75]. However, there are no studies on GLS effects on primary cell cultures derived from knee OA. Moreover, most of the studies on SFN mainly focused on articular chondrocytes and synovial fibroblasts, without considering OA pathology as a systemic joint disorder. More sophisticated in vitro co-cultures or 3D in vitro models would provide more reliable results. Another critical challenge is assessing whether the observed positive outcomes from GLS-rich foods in clinical trials or preclinical in vivo models are directly due to GLS. Therefore, myrosinase-thyoglucosidase-free in vitro models are essential to demonstrate GLSs’ direct effects without interference from metabolite conversion. This is a critical aspect as the biological activity of GLS is only recently be understood [76,77,78]. To gain more insight into the role of GLSs, another key aspect which could reveal variations in bioactivity is the comparison between GLSs from different groups (aliphatic, indolic, and aromatic).

Ruiz-Alcaraz conducted a direct comparison among GLS (glucoraphanin, glucoerucin, and glucobrassicin) and their derivatives ITC and indoles in an in vitro mirosinase-free model, demonstrating that GLS compounds have inherent anti-inflammatory potential [73]. This study found that glucobrassicin is the most effective GLS with anti-inflammatory properties in this system. Similarly, our group evidenced a direct effect of glucoraphanin, glucoerucin, and glucotropaeolin on mineralization in an in vitro mirosinase-free model [78,79], with glucotropaolin showing a superior effect than glucoerucin. Notably, in vitro models can also serve as screening platforms to select the most effective compounds or formulations, along with the best doses, thus minimizing the number of animals in research studies, one of the key principles of the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) [80].

Second, preclinical in vivo studies on GLS intake suggest potential chondroprotective benefits, primarily in post-traumatic OA models. However, this overlooks other important OA endotypes, such as inflammatory and metabolic phenotypes (i.e., collagenase model, obesity-diabetes models, etc.). This research gap emphasizes the need for more studies utilizing diverse models to better understand GLS and related compounds in the context of OA’s complexities. Interestingly, a few studies demonstrated the impact of GLS intake on pain. This aspect should be further deepened, as pain is a characteristic hallmark of OA and one of the main therapeutic targets. By examining varied approaches, researchers can identify nuanced responses and develop targeted therapies to address both the structural and symptomatic facets of OA, ultimately leading to improved patient outcomes. Despite in vivo studies being effective for validating the efficacy, the oral intake of GLS presents limitations related to their metabolic conversion into metabolites, making it hard to attribute direct effects to either the precursor or its metabolites. In this vein, it is crucial to increase approaches focused on clarifying how the GLSs are metabolized during the digestion process, specifically quantifying the amounts of intact GLS and all its metabolites at the systemic and local levels. Additionally, exploring alternative administration routes, such as intra-articular injections, could help bypass metabolic conversion and allow testing the direct effects of either GLS or its metabolites, while increasing their bioavailability in joint tissue.

Third, rigorous clinical studies are mandatory to clearly establish the efficacy of dietary administration of GLS-rich foods, GLS, or GLS-metabolites for OA prevention. Key aspects of clinical design should include a large sample size, well-controlled methodologies, studies of the metabolism of GLS and their metabolites upon oral administration, research into patient-specific factors, and safety concerns.

When looking forward to a preventive-therapeutic use of GLS, current issues are regarded to low GLS adsorption, and their high rate of metabolic conversion in the gut microbiota. However, considering that dysbiosis is a major issue in OA [81], the bioavailability and bioactivity of ITCs can be reduced [82]. In this context, developing new delivery systems to improve GLS and ITC levels into the articular joint could offer significant advantage, ensuring higher concentrations directly at the site of action and overcoming limitations associated with oral intake.

Regarding safety concerns, the high concentration of GLS in mustard and canola proteins has been described as an antinutritional factor, reducing bioavailability and absorption of essential nutrients (i.e., minerals and proteins) [83]. Another reported adverse effect of GSLs is the goitrogenicity [84]. However, a recent review cast doubt on previous assumptions and indicated that brassica vegetables are safe for thyroid function when consumed in reasonable amounts as part of a daily diet; conversely, eating raw vegetables, especially in high amounts, may increase the risk of a negative impact on the thyroid [85]. Similarly, high concentrations of ITC can be detrimental due to their high reactivity to thiols, in turn leading to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [86] with negative effects in the articular joint. Thus, it is imperative to assess the benefit–risk balance of GLS and ITC administration, establish a safe dose range and administration intervals to avoid potential toxic effects, and consider potential interactions with medications.

Altogether, in vitro, in vivo, and clinical studies have provided new valuable preliminary insights into the potential benefits of GLS-rich vegetables or their derivatives in the context of OA. By addressing current gaps and exploiting future perspectives, this review can fuel preclinical and clinical studies on the efficacy of GLS and breakdown products as non-pharmacological tools for the management of this chronic condition, paving the way for innovative therapeutic approaches in this area.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.D. and L.R.; resources: B.G.; writing—original draft preparation, G.D., L.G., E.A., G.B., S.C., F.G. and L.R.; writing—review and editing, G.D., B.G. and L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and APC were funded by the Italian Ministry of Health—5 × 1000 Anno 2022, Redditi 2021 “Ottimizzazione dei trattamenti attraverso l’integrazione di approcci innovativi e studio delle interazioni tissutali”. 5M-2022-23685320; CUP D33C23001460001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Martel-Pelletier, J.; Barr, A.J.; Cicuttini, F.M.; Conaghan, P.G.; Cooper, C.; Goldring, M.B.; Goldring, S.R.; Jones, G.; Teichtahl, A.J.; Pelletier, J.P. Osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glyn-Jones, S.; Palmer, A.J.R.; Agricola, R.; Price, A.J.; Vincent, T.L.; Weinans, H.; Carr, A.J. Osteoarthritis. Lancet 2015, 386, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Beaumont, G.; Castro-Dominguez, F.; Migliore, A.; Naredo, E.; Largo, R.; Reginster, J.Y. Systemic Osteoarthritis: The Difficulty of Categorically Naming a Continuous Condition. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2024, 36, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinusas, K. Osteoarthritis: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am. Fam. Physician 2012, 85, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, S.W.; Aladesuru, O.M.; Ranawat, A.S.; Nwachukwu, B.U. The Use of Biologics to Improve Patient-Reported Outcomes in Hip Preservation. J. Hip Preserv. Surg. 2021, 8, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaffagnini, M.; Boffa, A.; Andriolo, L.; Raggi, F.; Zaffagnini, S.; Filardo, G. Orthobiologic Injections for the Treatment of Hip Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhiparama, N.C.; Putramega, D.; Lumban-Gaol, I. Orthobiologics in Knee Osteoarthritis, Dream or Reality? Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2024, 144, 3937–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdan, M.; Bobrowska-Korczak, B. Active Compounds in Fruits and Inflammation in the Body. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameye, L.G.; Chee, W.S.S. Osteoarthritis and Nutrition. From Nutraceuticals to Functional Foods: A Systematic Review of the Scientific Evidence. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2006, 8, R127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapane, K.L.; Sands, M.R.; Yang, S.; McAlindon, T.E.; Eaton, C.B. Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine among Patients with Radiographic-Confirmed Knee Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2012, 20, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, A.N.; Shultz, S.P.; Huffman, K.F.; Vincent, H.K.; Batsis, J.A.; Newman, C.B.; Beresic, N.; Abbate, L.M.; Callahan, L.F. Mind the Gap: Exploring Nutritional Health Compared With Weight Management Interests of Individuals with Osteoarthritis. Nutr. Health Interests People OA 2022, 6, nzac084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loeser, R.F.; Beavers, D.P.; Bay-Jensen, A.C.; Karsdal, M.A.; Nicklas, B.J.; Guermazi, A.; Hunter, D.J.; Messier, S.P. Effects of Dietary Weight Loss with and without Exercise on Interstitial Matrix Turnover and Tissue Inflammation Biomarkers in Adults with Knee Osteoarthritis: The Intensive Diet and Exercise for Arthritis Trial (IDEA). Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2017, 25, 1822–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Schell, J.; Scofield, R.H. Dietary Fruits and Arthritis. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, N.; Stubbs, B.; Noale, M.; Solmi, M.; Luchini, C.; Maggi, S. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Is Associated with Better Quality of Life: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidinejad, A. The Road Ahead for Functional Foods: Promising Opportunities amidst Industry Challenges. Future Postharvest Food 2024, 1, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirodkar, S.; Khanchey, F.; Babre, N. Role of Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals in Nutrition and Health. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2025, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Ivorra, I.; Romera-Baures, M.; Roman-Viñas, B.; Serra-Majem, L. Osteoarthritis and the Mediterranean Diet: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapusta-Duch, J.; Kopeć, A.; Piątkowska, E.; Borczak, B. The Beneficial Effects of Brassica Vegetables on Human Health. Rocz. Państwowego Zakładu Hig. 2012, 63, 389–395. [Google Scholar]

- German, D.A.; Hendriks, K.P.; Koch, M.A.; Lens, F.; Lysak, M.A.; Bailey, C.D.; Mummenhoff, K.; Al-Shehbaz, I.A. An Updated Classification of the Brassicaceae (Cruciferae). PhytoKeys 2023, 220, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldelli, S.; Lombardo, M.; D’Amato, A.; Karav, S.; Tripodi, G.; Aiello, G. Glucosinolates in Human Health: Metabolic Pathways, Bioavailability, and Potential in Chronic Disease Prevention. Foods 2025, 14, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota, H.P. Analysis of Glucosinolates. In Recent Advances in Natural Products Analysis; Elsevier BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Ma, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Hou, L.; Li, M. Analysis of Glucosinolate Content and Metabolism Related Genes in Different Parts of Chinese Flowering Cabbage. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 767898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thinh Nguyen, V.P.; Stewart, J.; Lopez, M.; Ioannou, I.; Allais, F. Glucosinolates: Natural Occurrence, Biosynthesis, Accessibility, Isolation, Structures, and Biological Activities. Molecules 2020, 25, 4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitreiter, S.; Gigolashvili, T. Regulation of Glucosinolate Biosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 70–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Massih, R.M.; Debs, E.; Othman, L.; Attieh, J.; Cabrerizo, F.M. Glucosinolates, a Natural Chemical Arsenal: More to Tell than the Myrosinase Story. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1130208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blažević, I.; Montaut, S.; Burčul, F.; Olsen, C.E.; Burow, M.; Rollin, P.; Agerbirk, N. Glucosinolate Structural Diversity, Identification, Chemical Synthesis and Metabolism in Plants. Phytochemistry 2020, 169, 112100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aǧagündüz, D.; Şahin, T.Ö.; Yilmaz, B.; Ekenci, K.D.; Duyar Özer, Ş.; Capasso, R. Cruciferous Vegetables and Their Bioactive Metabolites: From Prevention to Novel Therapies of Colorectal Cancer. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 1534083. [Google Scholar]

- Cartea, M.E.; Velasco, P. Glucosinolates in Brassica Foods: Bioavailability in Food and Significance for Human Health. Phytochem. Rev. 2008, 7, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sones, K.; Heaney, R.K.; Fenwick, G.R. Glucosinolates in Brassica Vegetables. Analysis of Twenty-Seven Cauliflower Cultivars (Brassica oleracea L. Var. botrytis Subvar. Cauliflora DC). J. Sci. Food Agric. 1984, 35, 762–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.; Fenwick, G.R. Glucosinolate Content of Brassica Vegetables: Analysis of Twenty-Four Cultivars of Calabrese (Green Sprouting Broccoli, Brassica oleracea L. Var. botrytis Subvar. cymosa Lam.). Food Chem. 1987, 25, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.J.; Critchley, C.; Pun, S.; Chaliha, M.; O’Hare, T.J. Differing Mechanisms of Simple Nitrile Formation on Glucosinolate Degradation in Lepidium Sativum and Nasturtium Officinale Seeds. Phytochemistry 2009, 70, 1401–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, L.; Oruna-Concha, M.J.; Wagstaff, C. Identification and Quantification of Glucosinolate and Flavonol Compounds in Rocket Salad (Eruca sativa, Eruca vesicaria and Diplotaxis tenuifolia) by LC-MS: Highlighting the Potential for Improving Nutritional Value of Rocket Crops. Food Chem. 2015, 172, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brindisi, L.J.; Lyu, W.; Juliani, H.R.; Wu, Q.; Tepper, B.J.; Simon, J.E. Determination of Glucosinolates and Breakdown Products in Brassicaceae Baby Leafy Greens Using UHPLC-QTOF/MS and GC/MS. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 3, 100389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Ochar, K.; Hwang, A.; Lee, Y.J.; Kang, H.J. Variability of Glucosinolates in Pak Choy (Brassica rapa Subsp. chinensis) Germplasm. Plants 2024, 13, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uda, Y.; Ozawa, Y.; Maeda, Y. Volatile Isothiocyanates of Cruciferous vegetables introduced from China. J. Agric. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1982, 56, 1057–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Gudiño, I.; Casquete, R.; Martín, A.; Wu, Y.; Benito, M.J. Comprehensive Analysis of Bioactive Compounds, Functional Properties, and Applications of Broccoli By-Products. Foods 2024, 13, 3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciska, E.; Drabińska, N.; Honke, J.; Narwojsz, A. Boiled Brussels Sprouts: A Rich Source of Glucosinolates and the Corresponding Nitriles. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 19, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wermter, N.S.; Rohn, S.; Hanschen, F.S. Seasonal Variation of Glucosinolate Hydrolysis Products in Commercial White and Red Cabbages (Brassica oleracea Var. capitata). Foods 2020, 9, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abellán, Á.; Domínguez-Perles, R.; García-Viguera, C.; Moreno, D.A. Evidence on the Bioaccessibility of Glucosinolates and Breakdown Products of Cruciferous Sprouts by Simulated in Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oloyede, O.O.; Wagstaff, C.; Methven, L. Influence of Cabbage (Brassica Oleracea) Accession and Growing Conditions on Myrosinase Activity, Glucosinolates and Their Hydrolysis Products. Foods 2021, 10, 2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Kim, I.H.; Woyengo, T.A. Toxicity of Canola-Derived Glucosinolate Degradation Products in Pigs—A Review. Animals 2020, 10, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, E.; Abedi, M.; Aghajanzadeh, T.A.; Moreno, D.A. Caper Bush (Capparis spinosa L.) Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity as Affected by Adaptation to Harsh Soils. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đulović, A.; Burčul, F.; Čikeš Čulić, V.; Rollin, P.; Blažević, I. Glucosinolates and Cytotoxic Activity of Collard Volatiles Obtained Using Microwave-Assisted Extraction. Molecules 2023, 28, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qinghang, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Xin, X.; Li, T.; He, C.; Zhao, S.; Liu, D. Variation in Glucosinolates and the Formation of Functional Degradation Products in Two Brassica Species during Spontaneous Fermentation. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 6, 100493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Ochar, K.; Iwar, K.; Lee, Y.J.; Kang, H.J.; Na, Y.W. Variations of Major Glucosinolates in Diverse Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa Ssp. pekinensis) Germplasm as Analyzed by UPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, M.; Maravić, A.; Čulić, V.Č.; Đulović, A.; Burčul, F.; Blažević, I. Biological Effects of Glucosinolate Degradation Products from Horseradish: A Horse That Wins the Race. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbudu, K.G.; Witzel, K.; Börnke, F.; Hanschen, F.S. Glucosinolate Profile and Specifier Protein Activity Determine the Glucosinolate Hydrolysis Product Formation in Kohlrabi (Brassica oleracea Var. gongylodes) in a Tissue-Specific Way. Food Chem. 2025, 465, 142032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lietzow, J. Biologically Active Compounds in Mustard Seeds: A Toxicological Perspective. Foods 2021, 10, 2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Kim, R.H.; Hwang, K.T.; Kim, J. Chemical Compounds and Bioactivities of the Extracts from Radish (Raphanus sativus) Sprouts Exposed to Red and Blue Light-Emitting Diodes during Cultivation. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 1551–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, G.; Pernice, R.; Maggio, A.; De Pascale, S.; Fogliano, V. Glucosinolates Profile of Brassica rapa L. subsp. Sylvestris L. Janch. var. esculenta Hort. Food Chem. 2008, 107, 1687–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, C.; Ju, H.-Y.; Bible Bernard, B. Glucosinolate Composition of Turnip and Rutabaga Cultivars. Can. J. Plant Sci. 1981, 62, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, M.A. Isolation from Rutabaga Seed of Progoitrin, the Precursor of the Naturally Occurring Antithyroid Compound, Goitrin (L-5-Vinyl-2-Thiooxazolidone). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956, 78, 1260–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, R.A. Epithiospecifier Protein in Turnip and Changes in Products of Autolysis during Ontogeny. Phytochemistry 1978, 17, 1563–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Ishida, M.; Matsuo, T.; Watanabe, M.; Watanabe, Y. Separation and Identification of Glucosinolates of Vegetable Turnip Rape by LC/APCI-MS and Comparison of Their Contents in Ten Cultivars of Vegetable Turnip Rape (Brassica rapa L.). Soil. Sci. Plant Nutr. 2001, 47, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockhart, J. Methionine-Derived Glucosinolates: The Compounds That Give Brassicas Their Bite. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, F.J.; Nikmaram, N.; Roohinejad, S.; Khelfa, A.; Zhu, Z.; Koubaa, M. Bioavailability of Glucosinolates and Their Breakdown Products: Impact of Processing. Front. Nutr. 2016, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorska-Zimny, K.; Beneduce, L. The Metabolism of Glucosinolates by Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Pérez, A.; Núñez-Gómez, V.; Baenas, N.; Di Pede, G.; Achour, M.; Manach, C.; Mena, P.; Del Rio, D.; García-Viguera, C.; Moreno, D.A.; et al. Systematic Review on the Metabolic Interest of Glucosinolates and Their Bioactive Derivatives for Human Health. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casajùs, V.; Howe, K.; Fish, T.; Civello, P.; Thannhauser, T.; Li, L.; Lobato, M.G.; Martinez, G. Modified Atmosphere Affects Glucosinolate Metabolism during Postharvest Storage of Broccoli. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 44, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blekkenhorst, L.C.; Hodgson, J.M.; Lewis, J.R.; Devine, A.; Woodman, R.J.; Lim, W.H.; Wong, G.; Zhu, K.; Bondonno, C.P.; Ward, N.C.; et al. Vegetable and Fruit Intake and Fracture-Related Hospitalisations: A Prospective Study of Olderwomen. Nutrients 2017, 9, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, M.; Blekkenhorst, L.C.; Lewis, J.R.; Bondonno, C.P.; Devine, A.; Zhu, K.; Woodman, R.J.; Prince, R.L.; Hodgson, J.M. Vegetable and Fruit Intake and Injurious Falls Risk in Older Women: A Prospective Cohort Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 120, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, R.K.; Jupp, O.; De Ferrars, R.; Kay, C.D.; Culley, K.L.; Norton, R.; Driscoll, C.; Vincent, T.L.; Donell, S.T.; Bao, Y.; et al. Sulforaphane Represses Matrix-Degrading Proteases and Protects Cartilage from Destruction in Vitro and in Vivo. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 65, 3130–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapposelli, S.; Gambari, L.; Digiacomo, M.; Citi, V.; Lisignoli, G.; Manferdini, C.; Calderone, V.; Grassi, F. A Novel H2S-Releasing Amino-Bisphosphonate Which Combines Bone Anti-Catabolic and Anabolic Functions. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.A.; Yeo, Y.; Kim, W.U.; Kim, S. Phase 2 Enzyme Inducer Sulphoraphane Blocks Matrix Metalloproteinase Production in Articular Chondrocytes. Rheumatology 2009, 48, 932–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, M.; Huang, L.; Lv, Y.; Li, L.; Dong, Q. Sulforaphane Protects against Oxidative Stress-Induced Apoptosis via Activating SIRT1 in Mouse Osteoarthritis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 24, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, B.J. Seven Sirtuins for Seven Deadly Diseases Ofaging. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 56, 133–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.Y.; Choi, Y.J.; Jeong, G.J.; Im, G. Il Sulforaphane-PLGA Microspheres for the Intra-Articular Treatment of Osteoarthritis. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 5359–5368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaheri, B.; Poulet, B.; Aljazzar, A.; de Souza, R.; Piles, M.; Hopkinson, M.; Shervill, E.; Pollard, A.; Chan, B.; Chang, Y.M.; et al. Stable Sulforaphane Protects against Gait Anomalies and Modifies Bone Microarchitecture in the Spontaneous STR/Ort Model of Osteoarthritis. Bone 2017, 103, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redondo, A.; Chamorro, P.A.F.; Riego, G.; Leánez, S.; Pol, O. Treatment with Sulforaphane Produces Antinociception and Improves Morphine Effects during Inflammatory Pain in Mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2017, 363, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, R.K.; Watts, L.; Beasy, G.; Saha, S.; Kroon, P.; Cassidy, A.; Clark, A.; Fraser, W.; Mcnamara, I.; Kingsbury, S.R.; et al. The BRoccoli In Osteoarthritis (BRIO Study)—A Randomised Controlled Feasibility Trial to Examine the Potential Protective Effect of Broccoli Bioactives, (Specifically Sulforaphane), on Osteoarthritis. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, R.; Gardner, S.; Jupp, O.; Bullough, A.; Butters, S.; Watts, L.; Donell, S.; Traka, M.; Saha, S.; Mithen, R.; et al. Isothiocyanates Are Detected in Human Synovial Fluid Following Broccoli Consumption and Can Affect the Tissues of the Knee Joint. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, E.L.; Sim, M.; Travica, N.; Marx, W.; Beasy, G.; Lynch, G.S.; Bondonno, C.P.; Lewis, J.R.; Hodgson, J.M.; Blekkenhorst, L.C. Glucosinolates From Cruciferous Vegetables and Their Potential Role in Chronic Disease: Investigating the Preclinical and Clinical Evidence. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 767975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Alcaraz, A.J.; Martínez-Sánchez, M.A.; García-Peñarrubia, P.; Martinez-Esparza, M.; Ramos-Molina, B.; Moreno, D.A. Analysis of the Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Brassica Bioactive Compounds in a Human Macrophage-like Cell Model Derived from HL-60 Cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 149, 112804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Cremonini, E.; Mastaloudis, A.; Oteiza, P.I. Glucoraphanin and Sulforaphane Mitigate TNFα-Induced Caco-2 Monolayers Permeabilization and Inflammation. Redox Biol. 2024, 76, 103359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Lee, C.G.; Rhee, D.K.; Um, S.H.; Pyo, S. Sinigrin Inhibits Production of Inflammatory Mediators by Suppressing NF-ΚB/MAPK Pathways or NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Macrophages. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 45, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdull Razis, A.F.; Bagatta, M.; De Nicola, G.R.; Iori, R.; Ioannides, C. Up-Regulation of Cytochrome P450 and Phase II Enzyme Systems in Rat Precision-Cut Rat Lung Slices by the Intact Glucosinolates, Glucoraphanin and Glucoerucin. Lung Cancer 2011, 71, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlotz, N.; Odongo, G.A.; Herz, C.; Waßmer, H.; Kühn, C.; Hanschen, F.S.; Neugart, S.; Binder, N.; Ngwene, B.; Schreiner, M.; et al. Are Raw Brassica Vegetables Healthier than Cooked Ones? A Randomized, Controlled Crossover Intervention Trial on the Health-Promoting Potential of Ethiopian Kale. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambari, L.; Barone, M.; Amore, E.; Grigolo, B.; Filardo, G.; Iori, R.; Citi, V.; Calderone, V.; Grassi, F. Glucoraphanin Increases Intracellular Hydrogen Sulfide (H2 S) Levels and Stimulates Osteogenic Differentiation in Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cell. Nutrients 2022, 14, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambari, L.; Pagnotta, E.; Ugolini, L.; Righetti, L.; Amore, E.; Grigolo, B.; Filardo, G.; Grassi, F. Insights into Osteogenesis Induced by Crude Brassicaceae Seeds Extracts: A Role for Glucosinolates. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur Clark, J. The 3Rs in Research: A Contemporary Approach to Replacement, Reduction and Refinement. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 120, S1–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, J.; Hao, L.; Huang, G. Exploring the Interconnection between Metabolic Dysfunction and Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis in Osteoarthritis: A Narrative Review. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmytriv, T.R.; Lushchak, O.; Lushchak, V.I. Glucoraphanin Conversion into Sulforaphane and Related Compounds by Gut Microbiota. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1497566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilani, G.S.; Xiao, C.W.; Cockell, K.A. Impact of Antinutritional Factors in Food Proteins on the Digestibility of Protein and the Bioavailability of Amino Acids and on Protein Quality. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, S315–S332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavecchia, T.; Rea, G.; Antonacci, A.; Giardi, M.T. Healthy and Adverse Effects of Plant-Derived Functional Metabolites: The Need of Revealing Their Content and Bioactivity in a Complex Food Matrix. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanty, A.; Grudzińska, M.; Paździora, W.; Służały, P.; Paśko, P. Do Brassica Vegetables Affect Thyroid Function?—A Comprehensive Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, C.C.; Shoykhet, M.; Weiser, T.; Griesbaum, L.; Petry, J.; Hachani, K.; Multhoff, G.; Bashiri Dezfouli, A.; Wollenberg, B. Isothiocyanates in Medicine: A Comprehensive Review on Phenylethyl-, Allyl-, and Benzyl-Isothiocyanates. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 201, 107107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).