Abstract

In the financial sector, machine learning has become essential for credit risk assessment, often outperforming traditional statistical approaches, such as linear regression, discriminant analysis, or model-based expert judgment. Although machine learning technologies are increasingly being used, further research is needed to understand how they can be effectively combined and how different models interact during credit evaluation. This study proposes a technique that integrates hierarchical clustering, namely Agglomerative clustering and Balanced Iterative Reducing and Clustering using Hierarchies, along with individual supervised models and a self organizing map-based consensus model. This approach helps to better understand how different clustering algorithms influence model performance. To support this approach, we performed a detailed unsupervised component analysis using metrics such as the silhouette score and Adjusted Rand Index to assess cluster quality and its relationship with the classification results. The study was applied to multiple datasets, including a Taiwanese credit dataset. It was also extended to a multiclass classification scenario to evaluate its generalization ability. The results show that the quality metrics of the cluster correlate with the performance, highlighting the importance of combining unsupervised clustering and self organizing map consensus methods for improving credit evaluation.

1. Introduction

Machine learning develops algorithms to identify and learn data patterns and thus predict future outcomes or make complex decisions automatically [1]. In lending scenarios, Machine Learning can be used for two purposes: (1) to use supervised learning techniques to predict an applicant’s likelihood of defaulting on a loan, and (2) to employ unsupervised learning to find hidden patterns in the applicant database so that lenders can perform more thorough risk evaluation of applicants [2], for example, in predicting the probability of customer defaults, identifying fraudulent transactions, and facilitating other forms of decision-making [3]. Machine learning is increasingly being considered for integration into credit rating systems to identify the risk of customer default [4]. Credit risk models use characteristics such as the credit history of the customer, level of income, existing debts, and demographic characteristics such as age, sex, and number of dependents [5]. These models produce a score indicating the probability of default. Numerous examples show that machine learning models offer superior accuracy and adaptability to previously used credit risk scoring techniques based on traditional statistical methods such as linear regressions, discriminant analysis, or expert opinions [6].

Currently, financial institutions heavily rely on automated decision-making tools to process credit applications. Recent advances in supervised learning have enabled these systems to classify applicant risks more accurately than traditional methods [7]. Credit scoring models are essential tools for financial institutions, as they enable them to make more informed decisions when granting loans. Even slight improvements in model performance can generate substantial benefits [8], including reduced analysis costs, faster decision-making, better debt collection, and improved risk management [9].

To improve these models, researchers have tested several machine learning techniques, moving from single models to combinations of models using consensus models. Similarly, they are investigating how to combine supervised and unsupervised learning to achieve more robust performance. Among these approaches is the reference study by Bao et al. [10], which compared several combinations of models: individual supervised models, a Self-Organizing Map (SOM) [11] as a consensus model, and clustering using k-means.

Although promising, this methodology can be improved for a better analysis. For example, although SOM was used as a consensus model, the Area Under the Curve (AUC) metric was not calculated because of the difficulty in extracting the probability scores. However, it is possible to calculate the AUC using the probabilistic predictions of individual models as input to the SOM. This approach allows the SOM to organise these predictions in a lower-dimensional space for meaningful evaluation. Further exploration of the clustering component is necessary to better understand its influence on performance. Previous studies have often limited clustering to k-means, which may not represent more complex or non-linear data structures, thus motivating the exploration of alternative clustering methods. Clustering methods such as Agglomerative clustering [12] or Balanced Iterative Reducing and Clustering using Hierarchies (BIRCH) [13] can reveal alternative data structures that classifiers can exploit, potentially improving model performance. Therefore, it is useful to assess the clustering step more closely to learn more about the association between the nature of clustering, classifier learning, and performance.

The general objective of this study was to examine the implications of the clustering step on model performance. More specifically, it seeks to determine whether classifiers can learn better from clusters created using alternative methods to k-means clustering, such as Agglomerative and BIRCH clustering. Cluster quality was evaluated according to the silhouette score [14] and Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) [15]. This provides a better understanding of how different clustering structures affect supervised learning and the overall ensemble performance.

Before proceeding with the analysis, it was relevant to explain the methodology described by Bao et al. [10] using the same unbalanced datasets (Australian and German), and an additional dataset (Taiwanese), while also studying the case of multiclass classification to assess its generalizability. The methodology was implemented through a reproducible step-by-step pipeline, allowing future replication and offering meaningful contributions to the development of more robust credit scoring systems.

To summarize, first, we introduced a systematic integration of hierarchical clustering with SOM-based consensus. This integration offers a deeper understanding of the data structures relevant to predictive modeling, which may improve model accuracy. We further present a new robustness analysis that relates both unsupervised metrics (i.e., Silhouette and Adjusted Rand Index (ARI)) to classification performance. A third contribution is our multi-route comparative framework (Routes 1–5), which enables researchers to comparatively evaluate multiple, distinct approaches (Supervised, clustering-based, clustering-based consensus), thus providing a comprehensive understanding of the relative advantages and disadvantages of each approach. Last, we demonstrated how this technique can be extended to multiclass credit scoring, showing its generalizability beyond binary classification settings.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, a review of related studies explains the main methodologies and techniques relevant to this study. Section 3 and Section 4 describe the proposed framework and the motivation for its use in robust cluster analysis. Section 5 presents the evaluation metrics, datasets used, data preprocessing steps, feature selection, and hyperparameter tuning. Section 6 details the experimental process, including the choice of the number of clusters and the implementation of SOM consensus models based on hierarchical clustering. In Section 7, the results obtained from binary classification tasks on the German, Australian, and Taiwanese datasets are discussed. Section 8 presents a robust cluster analysis, including a comparison of clustering metrics and model performance in relation to these metrics. Section 9 addresses the case of multiclass classification, describes the dataset used, presents the experimental results, and compares them with the binary classification findings. Section 10 discusses the significance of the results and presents the limitations of this study. The practical contributions and implications and their significance to real-life applications are established in Section 11. Finally, Section 12 concludes the study, reviews the main findings and outlines possible ideas for future research.

2. Related Work

2.1. Consensus Models

Among machine learning techniques, consensus models are the most widely used and effective for improving prediction performance. Consensus models take advantage of the different strengths of multiple classifiers and improve predictions by combining classifiers to decrease bias and variance and enhance generalization ability. The fundamental concept is that aggregated predictions of multiple models generally outperform those of a single model. Common ensemble strategies include Bagging [16], Boosting [17], Stacking, and the Majority Voting (MV) models.

In MV, several independent models are trained independently, and their final prediction is made by voting: either a hard vote, where the class predicted by the majority is selected, or a soft vote, where predictions are made based on aggregated probabilities. This method is widely used for binary and multiclass classifications. Kuncheva and Whitaker [18] examined the role of classifying diversity using ensemble methods and demonstrated how diversity improves the effectiveness of MV strategies. In the context of credit scoring, the MV serves as a robust consensus strategy, effectively merging predictions from various models to achieve greater accuracy. Muniappan and Paruvachi Subramanian [19] studied the use of MV to improve the accuracy of credit scoring and demonstrated that combining model output through majority voting significantly reduced error rates and improved predictive results compared to individual classifiers. Thus, consensus models not only improve robustness and performance but also contribute to more stable and reliable decision-making systems in high-stakes applications such as credit evaluation.

In this work, we present Kohonen’s Self-Organizing Maps (SOM) as an alternative consensus mechanism that is beneficial compared to standard ensemble techniques. Kohonen [20] laid the theoretical principles of SOM, applying it to classification and data analysis. SOM is an unsupervised neural network, which converts high-dimensional data to a lower-dimensional grid regarding the topological structure of the input space. This property allows SOM to effectively group like predictions from ensemble classifiers, even when these classifiers have different error structures. This is important for the situation of credit scoring, in which a classifier is likely to make different types of errors. The property of SOM to cluster similar predictions is also an intuitive advantage for improving the credit score.

A significant advantage of SOM compared to conventional ensemble methods such as stacking or majority voting is its ability to smooth noise and errors [21]. Before engaging in majority voting on the resulting predictions, SOM will cluster the prediction vectors in a way that reduce the effect of any noisy or outlier predictions that would normally bias the results with a simple ensemble method.

SOM can accommodate the heterogeneity present in model predictions. SOM leads to a more stable and reliable consensus, particularly in high-variance environments such as credit rating. It is also beneficial in terms of interpretability, which is important in some contexts like credit scoring [22,23]. SOM offers a two-dimensional map that interprets how models agree or disagree, while also providing insight into the underlying relationships that exist among the classifiers. This explains why analysts can investigate the contribution each model had in ultimately coming up with the final decision. In this way, SOM acts as both a performance booster but is also growing in popularity as a means of making decisions more interpretable.

2.2. Integration of Supervised and Unsupervised Models

Traditional credit scoring mainly relies on a supervised model, such as an Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Decision Tree (DT), or Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) trained on labeled datasets to predict the probability of default. However, there are opportunities to improve these approaches, notably through unsupervised learning strategies, for complex unlabeled or structured data. Integrating supervised and unsupervised models has proven to be a promising strategy for improving the predictive accuracy of credit scoring by exploiting both the explicit patterns found in labeled data and hidden structures detectable in unlabeled datasets. For example, Hsieh [24] proposed a hybrid approach combining clustering techniques (self-organizing map (SOM) and k-means) with neural networks, demonstrating improved model performance through the synergy of these methods. Similarly, Arutjothi and Senthamarai [25] presented an integrated model that merges Logistic Regression (LR) with k-means, effectively capturing structured credit history and unstructured financial behaviors for optimized default probability modeling. Yu et al. [26] further introduced a two-stage hybrid system (TSC-SVM) that combines spectral clustering and a semi-supervised SVM to address unbalanced data issues in credit risk modeling, showing clear improvements over standard supervised approaches. Although many studies have focused on hybrid models involving supervised and unsupervised methods, consensus models involving multiple unsupervised techniques, such as clustering combined with SOM, remain underexplored.

Despite the established role of clustering in customer segmentation, the impact of these clusters on classifier performance has rarely been quantified, and comparative analyses of different clustering algorithms are often absent. This study addresses this gap by exploring the potential of combining multiple unsupervised methods in a consensus framework and evaluating their influence on the stability and performance of classifiers. Through this integration, the research not only evaluates various machine learning strategies but also tests the robustness of the baseline methodology to improve the accuracy and interpretability of credit scoring models.

2.3. Comparison with Alternative Machine Learning Paradigms

Numerous studies use different machine learning techniques to build credit evaluation prediction models. The following section compares credit scoring with ensemble-based machine learning methods and other Machine Learning paradigms (including reinforcement learning, rule-based, neuro-symbolic AI and neuromorphic engineering).

2.3.1. Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement Learning (RL) refers to an approach whereby agents learn to maximize their cumulative reward based on interactions with the environment. Even though RL has potential for credit scoring, its application remains limited. This is because credit data is mainly historical and non-interactive, unlike the dynamic and interactive environments typical of RL applications. Some studies have used RL to evaluate portfolios and for credit recommendations, but it is unknown if RL is effective for the credit scoring process, since credit scoring uses historical data and is more reactive than interactive [27,28]. Dynamic decision-making environments such as portfolio optimization and trading systems are the ideal environment for using RL for developing a model due to the way agents will need to make sequential decisions and repeatedly interact with the environment over time [29]. In contrast, a static credit classification task does not allow for sequential decision making nor require an agent to continually interact with the environment. The use of RL in this case is not practical since credit scoring is performed in batch mode, with a fixed dataset and a predetermined outcome.

2.3.2. Rule-Based Learning

While traditional expert systems and rule-based learning methods provide strong model interpretability, they have limitations in terms of their capability to model complex nonlinear behaviors. For example, rule-based systems are typically used in situations where the importance of explainability takes precedence (such as credit scoring), so the models created by these systems are less able to identify and capture the complex nonlinear relationship of financial variables [30]. The hybrid method outlined in this article is to combine supervised learning and clustering together to identify nonlinear relationships, while still providing some level of interpretability because of the clustering structure.

2.3.3. Neuro-Symbolic AI

Neuro-symbolic AI aims to incorporate the statistical strengths of deep learning with the structured reasoning learned from symbolic techniques to enable complex tasks needing logic and the ability to analyze patterns. A problem thus far has been that most credit scoring databases are tabular and structured in nature, making it difficult to effectively utilize symbolic learning techniques. However, Neuro-symbolic AI could be a valuable avenue for future work since it could potentially utilize the model interpretability associated with symbolic AI, while providing the predictive capabilities of deep learning [31]. Currently, although there are several neuro-symbolic methodologies proven to allow companies to utilize its capabilities, these methodologies are not widely utilized in credit scoring systems at this time [32]. The methodology presented in this paper takes a different practical approach as it incorporates an ensemble of models to provide a robust performance.

2.3.4. Neuromorphic Engineering

Neuromorphic engineering techniques focus on creating hardware in a way similar to the brain and using this hardware to optimize the process of evaluating very complicated calculations. it remains fundamentally a hardware-oriented approach. As a result, there is little or no application of neuromorphic techniques in the analysis of credit reports using tabular, historical and static datasets. This is in large part because most of the applications of neuromorphic techniques are in the areas of online learning (requiring real-time processing of incoming information). In comparison to the potential of neuromorphic engineering with regards to the application of the Internet of Things (IoT) or autonomous systems, the focus of this article does not encompass the effects that neuromorphic techniques would have within this application area [33]. Neuromorphic systems are designed specifically for hardware optimization and energy-efficient computing. They achieve optimized architecture and performance by emulating the characteristics of biological neural networks [34]. While relevant for large-scale deployment scenarios, this approach addresses implementation, and efficiency concerns rather than offering algorithmic improvements for tabular data classification. Our case focuses on improving prediction capability.

3. Overview of Proposed Framework

This section explains the methodological approach and helps understand the logical connections between different sections of the paper.

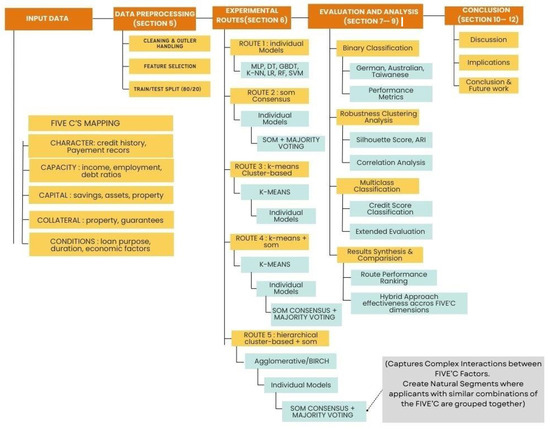

Figure 1 describes the framework process and the link between the C’s five credit evaluation (Character, Conditions, Capital, Capacity, and Collateral) [35]. The framework begins with data preparation (Section 5) where three datasets (German, Australian, Taiwan) are described. The next section (Section 6) describes five experimental routes from the clustered data to the final model. Each route is a different combination of clustering methods with supervised classifiers and the use of Self Organizing Map (SOM) method to generate a consensus model from the classifiers. Route 1 establishes baseline performance using individual classifiers, while Route 2 introduces SOM consensus. Routes 3–5 also tested different clustering methods (k-means, Agglomerative, BIRCH) using the same three datasets. Route 5 introduced hierarchical clustering approach. All routes converge into the evaluation phase (Section 7, Section 8 and Section 9). This phase provides a performance analysis of each route for binary classification, clustering robustness, and multiclass extension. The results are synthesized to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of integrating unsupervised and supervised learning for credit evaluation.

Figure 1.

Study framework.

Problem definition: The study addresses the improvement of credit scoring models by integrating unsupervised clustering with supervised classifiers. It investigated how clustering quality influences the ability of classifiers to accurately predict creditworthiness using clusters generated with different clustering techniques (i.e., Agglomerative, BIRCH, k-means). The clusters were combined with supervised classification methods (e.g., ANN, SVM, RF) as well as a consensus mechanism based on SOM.

Inputs: The inputs are three publicly available credit datasets:

- German: 1000 samples, 20 features, binary class (70% good, 30% bad).

- Australian: 690 samples, 14 features, binary class (44.5% good, 55.5% bad).

- Taiwanese: 30,000 samples, 23 features, binary class (77.88% good, 22.12% bad).

Outputs: The outputs are classification performance metrics (MCC, AUC, Accuracy, Recall, Precision, Type I/II errors) for all five experimental routes (R1–R5) and resumed in Tables 4–9 (for binary classification) and Tables 22 and 23 (for multiclass classification). The results show the impact of clustering and consensus method on model performance.

4. Methodology

This section is divided into two sections. It presents the framework proposed in the reference paper, adding a new approach as well as the clustering analysis performed to evaluate the consistency and impact of different clustering techniques.

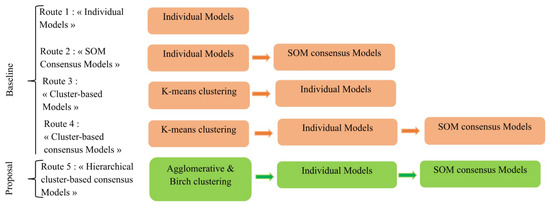

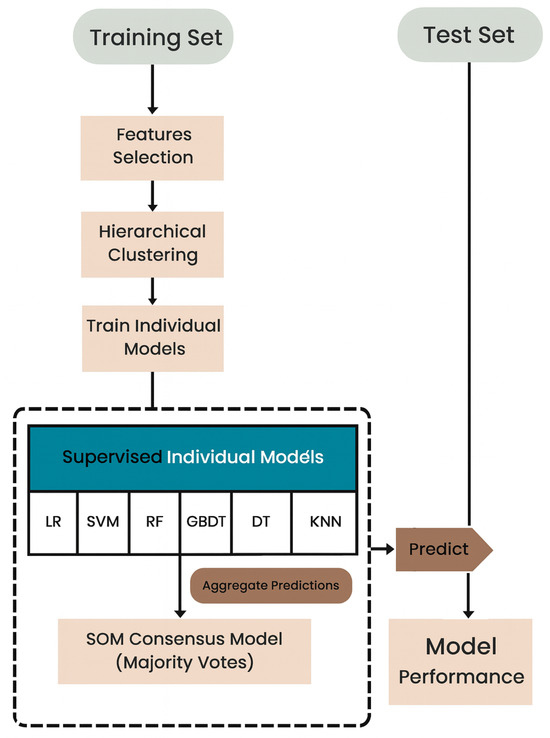

4.1. Proposed Framework

Figure 2 illustrates the methodological framework and presents five experimental Routes focused on quantifying the usefulness of integrating unsupervised learning into supervised credit scoring models. Route 1–4 were from Bao et al. [10]. The first experimental route establishes a baseline by evaluating each classifier (such as a multi-layer perceptron (MLP), DT, GBDT, LR, k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), Random Forest (RF), and SVM) before any integration is applied. Route 2 builds on the classifiers by applying a consensus model based on the SOM, where the predictions of each classifier are aggregated by majority voting, producing a more robust classification. Route 3 introduced k-means clustering as a preprocessing step, generating clusters and adding the clusters as a new variable to the dataset, and then individually training the classifiers to predict the corresponding label. Route 4 extends Route 3 by applying the SOM consensus to k-means-based models, following the same pattern as Route 2. Finally, Route 5 was added. It combines hierarchical clustering, individual classifiers, and consensus based on the SOM, allowing for a comparative examination of different clustering techniques.

Figure 2.

Baseline approach 1 and Proposal. 1 Source: [10].

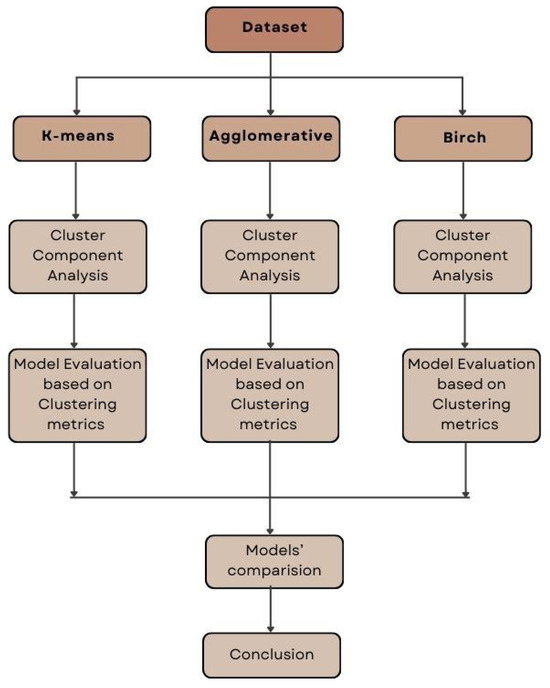

4.2. Robustness Clustering Analysis

Following the model development and evaluation through the five experimental pathways, the next part of the methodology focuses on examining the robustness and influence of clustering on model performance. This evaluation is necessary to determine the effectiveness of clustering in improving the classification performance.

To determine robustness, we systematically compare the three clustering strategies in this study (k-means, Agglomerative, and BIRCH) in terms of their impact on subsequent classification. The quality and stability of the clustering results were assessed using common metrics such as the silhouette score and Adjusted Rand Index (ARI). These metrics will help evaluate the stability of the clusters produced in terms of cohesion and separation. They also provide insights into the qualitative depth and stability of clusters, which are necessary for the formation of meaningful clusters. We then compared the performance of the classifiers for each method to identify the cluster with the best synergy. Finally, we analyze the performance metrics of each route to draw conclusions regarding the effectiveness of the clustering methods in a hybrid credit scoring system. Overall, this two-dimensional analysis allows us to go beyond simple clustering directly to information about clusters or their stability, which allows us to better understand the conditions under which unsupervised learning can be most effective. This analysis focuses only on routes 4 and 5. The clustering analysis methodology is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Proposed clustering analysis methodology.

4.3. Integration of the Five C’s into the Proposed Approach

This section presents the link between our approach and the five C’s of credit evaluation: Character, Capacity, Capital, Collateral, and Conditions. We explain how these concepts are integrated into our methodology (Figure 1).

The explanatory variables in the three datasets used in this study (German, Australian, Taiwanese) include the five C’s, though their representation varies across datasets. Below, we explain how each ’C’ is represented in the dataset characteristics [36]:

- Character (Credit History): This factor includes variables related to payment history, past defaults, and credit behavior. This information helps assess a borrower’s reliability by capturing indicators such as late payments and the consistency of past repayments.

- Capacity (Repayment capacity): The ability to repay a loan is shown through characteristics like income, employment status, and debt-to-income ratios. These variables help determine if a borrower can handle new debt based on their income and current financial obligations.

- Capital (Financial reserves): Savings, assets held, and financial reserves are examples of financial indicators that represent this C. This data reveals a borrower’s financial stability, which may have an impact on their capacity to repay in the event of problems.

- Collateral: Our datasets contain variables that indicate the existence of collateral, such as real estate or other property. When evaluating a loan’s security in the event of borrower default, this information is essential.

- Conditions (Economic context): Factors pertaining to the loan’s purpose, interest rates, and, if available, macroeconomic indicators are considered. These factors can have an impact on a borrower’s capacity to repay. For instance, the borrower’s financial stability and, consequently, their capacity to repay may be impacted by overall economic conditions.

Our method combines clustering and supervised classification techniques with features taken from the datasets to address these five dimensions. We use a SOM (Self-Organizing Map) consensus mechanism and clustering algorithms (like k-means, Agglomerative, and BIRCH) to find groups of borrowers with comparable profiles based on these five criteria. By incorporating these variables into our model, we can investigate the intricate relationships between these various elements as well as more precisely evaluate credit risk.

Based on similarity across all features, our clustering techniques (k-means, Agglomerative, and BIRCH) automatically group candidates. Classifiers can learn cluster-specific decision patterns because this effectively creates natural segments where applicants with similar combinations of the five C’s are grouped together. While maintaining the topological connections between various credit profiles, the Self-Organizing Map consensus mechanism functions as an ensemble credit committee that synthesizes several specialized opinions (individual classifiers). This is like how human credit analysts combine data from all five C’s to make a final decision. For instance, there are a total of twenty explanatory variables in the German dataset. The most pertinent ones for the five C’s framework are covered in the Table 1 below. Because credit evaluation factors are interconnected, some variables (such as property and other_parties) contribute to more than one category. Since they don’t directly fit into the conventional five C’s categories, variables like “telephone” and “number_people_liable” were left out of this mapping.

Table 1.

Mapping of German credit dataset variables to the five C’s of credit evaluation.

Although our methodology is based on machine learning, it remains closely linked to the fundamental principles of credit evaluation (Figure 1 above), where the five “C’s” are naturally integrated into the data analysis process. This reinforces the relevance and interpretability of our approach, while allowing us to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of integrating supervised and unsupervised learning techniques for credit assessment.

5. Evaluation Metrics, Data Sources and Preprocessing

5.1. Evaluation Metrics

The test sets were evaluated for predictive performance using seven metrics: the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), Area Under the Curve (AUC), accuracy (ACC), Recall, Precision, Type I error, and Type II error (Table A1 in the Appendix B). MCC is particularly relevant when studying unbalanced datasets because it integrates four different classifications (i.e., true positive, false positive, true negative, and false negative). It is more reliable and balanced assessment of classification performance than accuracy when the class distribution is unbalanced. MCC measures the consistency between the predicted and actual results with a range from −1 (perfect disagreement) to 1 (perfect prediction); zero indicates random classification.

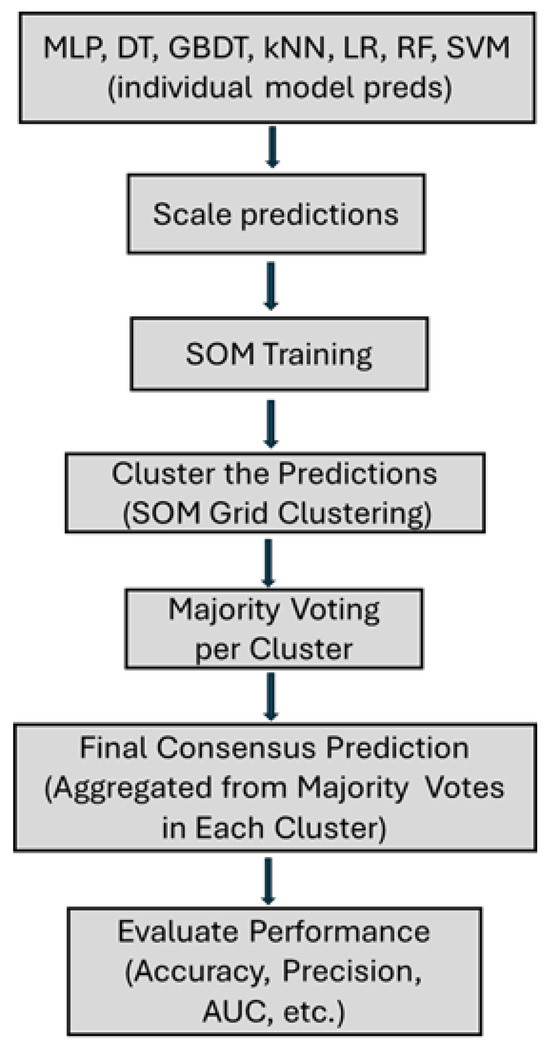

The AUC quantifies the area under the ROC curve and evaluates a classifier’s ability to produce a ranking. However, the SOM, which is an unsupervised neural network, organizes data topologically without providing probabilities of class membership. Therefore, the AUC cannot be calculated directly from the SOM results. SOM is an unsupervised neural network that organizes instance data topologically, grouping similar instances close together on a two-dimensional grid. Therefore, SOM does not provide results in terms of probabilities; the AUC cannot therefore be calculated solely from these results. This limitation has also been noted in a previous study. That said, the AUC can be estimated indirectly using SOM in a hybrid or post-processing framework.

For example, in clustering approaches followed by supervised classification, the SOM is first trained to group similar data. After clustering, classifiers, such as LR or k-NN, predict class probabilities. Another technique, presented by Halkidi et al. [37], involves combining SOM with k-means clustering, in which the clusters formed by neurons are further processed to estimate the probability distributions per sample. This enabled the calculation of AUC based on the probabilities of the derived class.

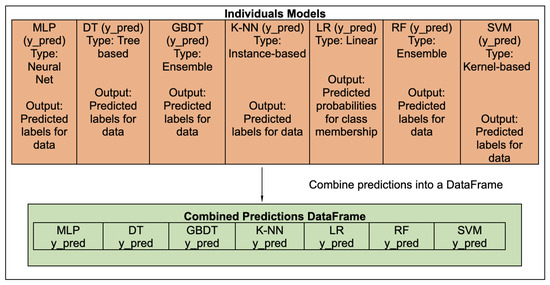

In this study, the supervised models generated class probability outputs that were organized and clustered using SOM. The consensus model uses the predictions of individual classifiers to accumulate them by majority vote to evaluate the results of the aggregated predictions. This means that we can calculate the AUC scores, including the probabilistic output of the base classifiers, even with SOM. Although AUC is computed by feeding supervised model probabilities into SOM, the SOM itself does not generate probability distributions or necessarily preserve ranking properties needed for ROC metrics. Thus, the AUC values attributed to ’SOM consensus’ reflect the underlying supervised models, not the SOM. Figure 4 illustrates the complete process of aggregating predictions using the SOM consensus model, the steps involved in implementing majority voting, and the process of evaluating the performance of the outputs.

Figure 4.

Majority Voting process.

5.2. Datasets

Here are descriptions of the datasets used:

- German dataset

The German bank dataset is available in the UCI repository [38] and contains 1000 observations and 21 variables, including 20 explanatory variables. The target variable is the credit score, with two classes: good (70%) and bad (30%). The set is unbalanced between classes with no missing values.

- Australian dataset

The Australian dataset, also available on the UCI repository [39], is linked to credit card applications and is also referenced as the “Credit Screening Database” and uses a binary variable to indicate whether a candidate is good or bad. Of the 690 samples containing 307 were good candidates (44.5%) and 383 were bad candidates (55.5%).

- Taiwan dataset

The Taiwanese dataset comes from the UCI repository and concerns credit card customer payment defaults in Taiwan, collected in October 2005 by a major credit card and cash credit issuing bank [40]; it includes a binary variable as a target, representing payment default (1 for “Yes”, 0 for “No”), and contains 30,000 samples, including 6636 defaults (bad candidates) and 23,364 non-defaults (good candidates), with defaulting candidates representing 22.12% of samples and non-defaulters accounting for 77.88%.

The datasets used were class-imbalanced, which affects performance on minority classes. To overcome this issue, we chose majority voting (MV) as the consensus mechanism. This method has several advantages in an imbalanced data context, including reduced risk of overfitting on the majority class and improved robustness. Majority voting has the potential to increase model robustness while reducing the risk of overfitting to the majority class and improving the overall accuracy by combining predictions from multiple models. Several studies have shown that this method, considered for imbalanced datasets, can help manage the impact of the minority class on the model performance [41,42]. Table 2 presents a summary of the dataset information in terms of the sample size and feature dimension.

Table 2.

Datasets description.

5.3. Data Pre-Processing

Data cleaning involves removing some cases and imputing missing values to improve the quality. This process aims to eliminate errors and correct the inaccuracies that can affect the results. However, the data used in this study did not contain missing values or duplicates, making data cleaning unnecessary. We visualized the feature distributions using box plots to observe the distribution of the variables across different classes. Outliers are identified during this step. To handle outliers, we applied the interquartile range (IQR) and then modified the outliers by taking the mean or mode, depending on the type of variable. However, in the datasets, outliers did not appear to affect model performance.

5.4. Features Selection

Feature selection is an important step in building a machine learning model. This is the process of selecting the most appropriate and relevant features from a dataset that are likely to influence the predictive power of the model. To identify the most important features and eliminate irrelevant features, we applied a selection process based on the RF model using scikit-learn. We visualized the importance of the features, selected the most significant features, and analyzed the performance of the model before and after adding the feature selection to each dataset. The data were split into training (80%) and testing (20%) sets and saved as .csv files.

The training dataset was first loaded, and the RF model was trained on all features. The performance of the model was assessed, and the features were ranked according to their importance. Significant features were selected, and a new model was trained on this reduced set of features. The performance was re-evaluated and recorded.

- -

- German dataset features selection:

The accuracy before feature selection was 0.7350. After selecting 15 features, it was increased to 0.7550. The model based on the 15 features outperformed the original dataset model. Thus, 15 features were selected for the final prediction.

- -

- Australian dataset features selection:

The accuracy before feature selection was 0.8768, whereas after selecting 10 features, it decreased to 0.8551. A reduced feature set is not used. We used the original dataset for the final prediction.

- -

- Taiwan dataset features selection:

The accuracy before feature selection was 0.8160. After selecting 15 features, it dropped to 0.7550, and only after selecting 18 or 20 features did the accuracy return to 0.8148. This slight variation suggests that most of the features contributed. Hence, we used the original dataset for the predictions. Table 3 summarizes the feature selection process.

Table 3.

Feature selection summary.

5.5. Hyperparameter Tuning

To optimize the efficiency of each model, we tuned the hyperparameters using the GridSearchCV method combined with cross-validation (CV = 5). We used a large grid of hyperparameters, allowing the model to reach a wide range of possible configurations and then to find the optimal parameters for optimum performance. In addition, we increased the number of iterations to provide the models with more time to converge, thereby increasing the chances of reaching the most efficient solution. Once the best parameters were identified through a grid search, we re-tuned the final model on the entire training dataset using these optimal hyperparameters. This final step ensures that the model is retrained with the most suitable parameters, making the final version as accurate and robust as possible (see Table A2 in the Appendix B).

For Agglomerative, we chose to set n_clusters = 2 and linkage = ‘average’. This configuration is commonly used for its ability to produce stable and interpretable results in hierarchical clustering contexts. The choice of linkage = ‘average’ allows us to consider the average distance between the points in each cluster, which yielded good results in our tests. For BIRCH, we used n_clusters = 2. For the other parameters, we used the default parameters threshold = 0.5, branching_factor = 50, max_iter = 100, compute_labels = True, copy = True, affinity = ‘euclidean’, random_state = None.

6. Experimental Process

In this section, we focus only on the proposed Route 5. For reference, we referred to the study by Bao et al. [10] and maintained the same experimental setup to ensure comparability. All experiments were performed in Python 3.10 in a server environment equipped with a core memory size of 130 GiB and a CPU AMD Ryzen 9 5950X 16-Core Processor. The consensus models analyzed followed the approaches detailed in Section 4.1 and a summary of Routes 1–4 is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of Experimental Routes (1–4).

Appendix C presents a general example illustrating the experimental process of Route 5 from a simple dataset, in order to provide a clear overview of the entire experimental process.

6.1. Choice of the Number of Clusters k

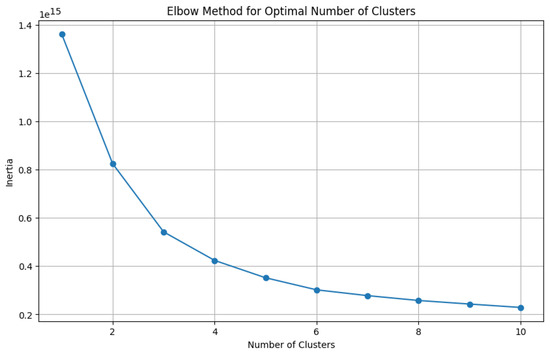

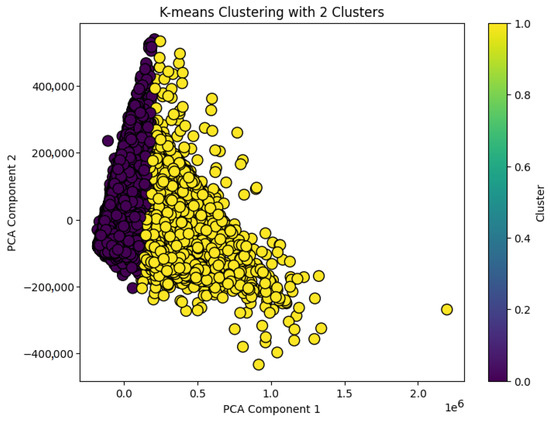

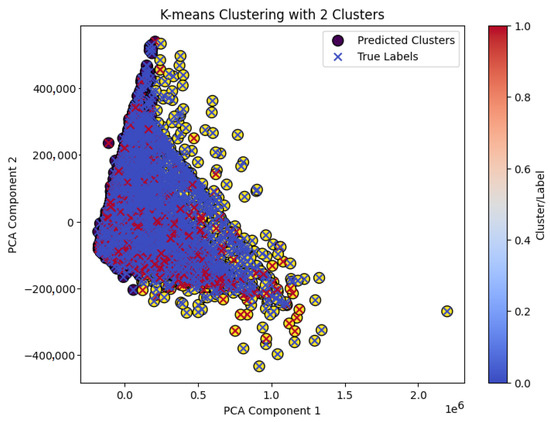

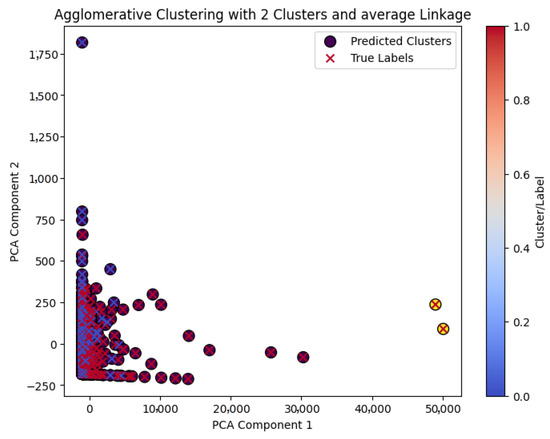

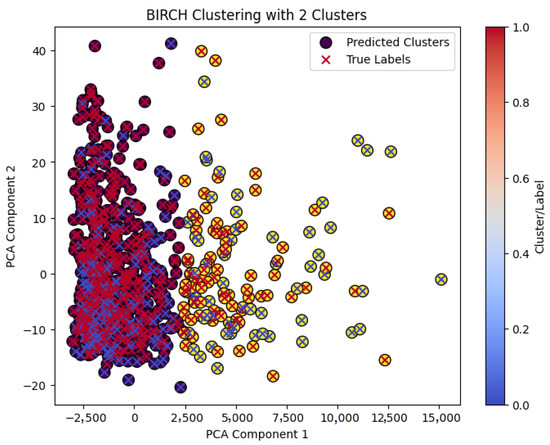

The k-means method requires the value k to be pre-specified. k is the number of clusters into which data can be grouped. The elbow method was used to determine the optimal number of clusters. Visualization of the elbow method for the three datasets showed that or 3 are good values for k (where the graph becomes more linear (Figure 5)). To select a suitable value for k, we computed the silhouette score [14] for each value of the k number. The silhouette score indicates separation between clusters. A low silhouette score (0 or negative) indicates some overlap between clusters, suggesting confusion in classification due to the lack of distinctiveness in the data points being classified. provided the best possible scores for all the datasets. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) from the sklearn decomposition library was used to reduce the original dimensionality of the datasets to two dimensions (2D) for visualization (Figure 6). Visualizations based on the first two principal components (PCA) are used to illustrate the clusters. It is important to note that these 2D visualizations, produced by an PCA, are only illustrative and qualitative. They do not accurately represent the separations between clusters in the original high-dimensional space. In fact, all clustering decisions were made using the complete set of features in their original dimension. They allow us to observe general trends and apparent groupings in the data, but they should not be interpreted as accurate representations of the separation of clusters in the full feature space.

Figure 5.

Elbow method for optimal number of clusters of Taiwan dataset.

Figure 6.

Clusters of Taiwan dataset.

6.2. ROUTE 5: SOM Consensus Model Based on Hierarchical Clustering

Figure 7 illustrates the experimental process for Route 5. This route utilizes a combination of hierarchical clustering techniques, supervised models, and a consensus model based on SOM to improve the prediction and generalization.

Figure 7.

Route 5: SOM consensus model based on hierarchical clustering + individual models’ experimental process.

First, hierarchical clustering was performed on the data to cluster similar points before supervision. In this study, we evaluated two hierarchical clustering algorithms: Agglomerative clustering (with linkage average) and BIRCH clustering. These methods were selected because they import structures into the data without actively controlling the shapes and sizes of clusters.

The SOM uses the prediction probabilities from each of the clusters and base models as inputs and organizes them topologically. The predictions from all individual models were combined using DataFrame (Figure 8). Each model (e.g., MLP and DT) has separate columns that represent their predictions. This combination, along with the final DataFrame, contains a column for each model, allowing for the collective analysis of predictions and the better application of ensemble methodologies. Consensus predictions are based on the predictions of individual classifiers. These predictions were scaled and integrated into the SOM model, which grouped the similar predictions.

Figure 8.

Combine predictions dataframe.

The final decision was made by a majority vote on the SOM grid. This additional SOM model assists in reconciling differences between cluster-based models and provides a global view of the dataset’s patterns. This route retains the benefits of unsupervised learning for data structure (by hierarchical clustering), whereas supervised learning is used for prediction with SOM serving as a consensus mechanism to improve generalization and overall robustness of the final model.

7. Experimental Results (Binary Classification)

This section presents the detailed results for each dataset and compares the performance of this study with that of the reference study.

7.1. German Dataset

The results for the German test set are presented in Table 5 and Table 6. A comparative analysis of the different classification routes (Routes 1 to 5) applied to the German dataset revealed a clear improvement in the hybrid approaches that integrated unsupervised and SOM techniques. The individual models (Route 1) showed the weakest performance for all metrics. In contrast, Route 2 to Route 5 showed significant improvement, particularly in terms of MCC, AUC, ACC, recall, and precision. Among these, Route 5, which combines hierarchical clustering (Agglomerative or BIRCH) with SOM, stands out with the best values for Agglomerative (MCC (0.5708), ACC (0.825), precision (0.8322)) and BIRCH (AUC (0.7859), recall (0.9420), and the lowest Type II error (0.0579)), illustrating the excellent ability to detect positive classes without generating too many false negatives. Compared with the reference study (MCC (0.490), ACC (0.792)), this model showed a significant improvement. Aggregating SOM model predictions improved robustness and accuracy. Although Route 3 (DT) exhibited the best performance in terms of Type I error (0.3548), Route 5 maintained a good balance between all metrics. These results confirm that the integration of clustering techniques with SOM enables a more relevant structure of the data and leads to a general improvement in classification performance. Consequently, Route 5 appeared to be the most robust and effective for processing this type of data. The consensus models (Routes 2, 4, and 5) outperformed the individual and cluster-based models, confirming the advantage of SOM in improving the classification performance.

Table 5.

Model performance for All Routes—German Dataset (Part 1).

Table 6.

Model performance for All Routes—German Dataset (Part 2).

7.2. Australian Dataset

Table 7.

Model performance for All Routes—Australian Dataset (Part 1).

Table 8.

Model performance for All Routes—Australian Dataset (Part 2).

An analysis of the results obtained using the Australian dataset revealed significant differences in the performance between the different approaches. The individual models (Route 1) performed fairly well, with an MCC of 0.7395 (SVM) and an AUC of 0.8739 (SVM). The SOM consensus model (Route 2) significantly improved all indicators, achieving an MCC of 0.8598, an AUC of 0.9042, an ACC of 0.9347, a precision of 0.9565, and a Type I error rate of 0.0229. Compared to the baseline, this model improved the MCC (0.725), ACC (0.862), and precision (0.806) values. The models resulting from k-means segmentation (Route 3) obtained performances comparable to or slightly inferior to those of individual models. In contrast, the combination of k-means and SOM (Route 4) showed substantial improvement, particularly for MCC (0.8138) and AUC (0.9118). Finally, the models based on clustering followed by SOM consensus (Route 5) clearly dominated all routes; in particular, the variant using the Agglomerative clustering achieved the best scores for almost all metrics: MCC (0.8765), AUC (0.9107), ACC (0.9420), precision (0.9777), and Type I error rate reduced to 0.0114. In conclusion, the integration of clustering and SOM provides a particularly powerful classification framework that offers the best compromise between performance indicators, clearly outperforming traditional or simple cluster-based approaches.

7.3. Taiwan Dataset

The results of the Taiwan test set are presented in Table 9 and Table 10, where the performance analysis on the Taiwanese dataset shows a more modest improvement than in the German and Australian cases but still highlights interesting differences between the different approaches. The individual models (Route 1) obtained relatively homogeneous results, with MCCs of approximately 0.39 for the best (RF and GBDT) and a precision of approximately 0.80. However, their recall remained high (approximately 0.81), suggesting a good ability to detect positive cases, but at the cost of a high Type II error rate (often >0.64). The SOM consensus approach (Route 2) improved the MCC (0.4014) and AUC (0.7710) while maintaining good precision (0.6807). However, this method had a significantly lower recall (0.3556), indicating a reduction in the sensitivity in detecting positive cases. The models derived from k-means (Route 3) did not offer any clear advantage, with MCC and AUC comparable to the individual models and slightly lower performance in terms of recall and precision. The combined k-means and SOM model (Route 4) offered a slight gain, with an MCC of 0.4038, an AUC of 0.7606, and an ACC of 0.823. Finally, in Route 5, the consensus methods based on Agglomerative or BIRCH clustering yielded consistent results: the BIRCH version had the best overall MCC (0.4057), an ACC of 0.8231, and the lowest Type II error rate (0.6359).

Table 9.

Model performance for All Routes—Taiwan Dataset (Part 1).

Table 10.

Model performance for All Routes—Taiwan Dataset (Part 2).

Although the improvements are subtler than those for the German and Australian datasets, the approaches based on consensus and Route 5 once again proved to be the most robust. They optimized the balance between the key metrics while maintaining better error rates. Overall, for the Taiwan dataset, all models were closely matched; however, Route 5 with BIRCH performed slightly better.

Analysis of the three datasets allowed us to draw several conclusions. Although the results differed from those presented in the reference study, they showed a similar overall trend, leading to a conclusion closely aligned with that of the reference study.

The adoption of the consensus model clearly improves the performance of individual models. Furthermore, applying dataset clustering not only improves the performance of each individual model but also enables additional performance gains when combined with the consensus strategy. In addition, the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) values of the individual supervised models increased significantly when the consensus model and dataset clustering were used together.

8. Robustness Clustering Analysis (Binary Classification)

This analysis focuses on binary classification and, as such, does not extend to multiclass data. However, for multiclass classification, the results were mainly analyzed in terms of overall performance and qualitative comparison.

Clustering plays an essential role in representing and grouping data. Analyzing the quality of clustering and its ability to accurately represent data is crucial because this step can have a direct impact on how classifiers interact with data and, consequently, on their performance. This part of the study examines the clustering process in the model. The central question addressed was whether the performance of cluster-based models depends on the quality of the clustering.

Furthermore, this study examines whether there is a correlation between the cluster quality and the observed performance of the model. To assess this correlation, we compared the clusters obtained with the original class labels, thus analyzing the distribution of class instances among the clusters. The silhouette score [14] is used as a measure of cluster quality, reflecting the degree of separation between clusters. The Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) [15] was used to measure the similarity between the clustering results and the true class labels, thus providing information on the alignment of clusters with the classes.

8.1. Clustering Metrics Comparison

We calculated the metrics and performed a comparison between the obtained clusters and the original class labels after determining the number k of optimal clusters for each dataset. The results for the Australian training set are presented in Table 11.

Table 11.

Australian training set clustering methods comparison.

The following are comments on the results obtained for the German and Taiwanese training sets.

German training set:

The results of the clustering methods for the German training set are listed in Table 12.

Table 12.

German training set clustering methods comparison.

For k-means, the silhouette score obtained was 0.7119, indicating a good separation between the clusters. However, the ARI was only 0.0450, indicating a very weak correspondence between the clusters and the true classes. Table 13 shows that the majority of observations in the two classes are unbalanced within the clusters.

Table 13.

Correspondence matrix of German training set for k-means.

For the Agglomerative (linkage = “average”), the silhouette score was even higher, at 0.7461, showing a very clear separation between clusters. However, the ARI was only 0.0192, reflecting a very low fidelity to real classes. Table 14 shows that almost all observations were grouped together in a single cluster, reducing the usefulness of this method to reflect the real structure of the classes.

Table 14.

Correspondence matrix of German training set for Agglomerative.

For BIRCH, the silhouette score reached 0.7139, again indicating good separation between clusters. However, the ARI remains low, at 0.0480, again reflecting poor correspondence with the original classes. Table 15 shows that, although the observations are distributed slightly more evenly between the clusters than in the previous case, they do not perfectly map to their actual classes.

Table 15.

Correspondence matrix of German training set for BIRCH.

Although all three showed high silhouette scores, indicating good separation between clusters, the very low ARI values revealed a poor match with actual classes. This suggests that the structures identified by the algorithms do not faithfully reflect the original classification.

In summary, although all three methods produced well-separated clusters according to the silhouette score, they failed to capture the true structure of the classes (low ARI). This reveals the limitations of unsupervised clustering in this particular case.

Taiwan training set:

The results of the clustering methods for the Taiwanese dataset are presented in Table 16. Although each of these clustering methods showed relatively good separation between clusters, none of them convincingly matched the actual classes, as revealed by the low ARI scores. The results suggest that the cluster structure does not fully capture the distribution of classes.

Table 16.

Taiwan training set clustering methods comparison.

For k-means:

The silhouette score obtained was 0.5539, indicating moderate separation between the clusters. This means that overall, the points are closer to their assigned cluster than to neighboring clusters. However, the ARI, which was −0.0177, indicated that the clusters generated by k-means did not align with the original classes (Table 17).

Table 17.

Correspondence matrix of Taiwan training set for k-means.

For the Agglomerative (linkage = “average”), the silhouette score was 0.8968, indicating a very clear separation between the clusters. However, the ARI was −0.0003, indicating once again that there was no real correspondence with the actual classes. As shown in Table 18, Cluster 0 contained the majority of Class 0 observations (18,677), and only one observation of Class 1, whereas Cluster 1 contained 5323 observations of Class 0 and no observation of Class 1.

Table 18.

Correspondence matrix of Taiwan training set for Agglomerative.

For BIRCH, the silhouette score was 0.5059, indicating lower separation compared to the other methods. The ARI, which is −0.0089, also shows poor alignment with the real classes. The obtained clusters contained 18,677 and 5323 observations. As shown in Table 19, Cluster 0 mainly contained Class 0 observations (15,949) and Class 1 (4619). Cluster 1 also contains a mixture of the two classes (2728 from Class 0 and 704 from Class 1), although the separation is less marked than that with k-means and Agglomerative.

Table 19.

Correspondence matrix of Taiwan training set for BIRCH.

Although the three clustering methods applied to the three datasets provided reasonable cluster separations, all of them showed shortcomings in their correspondence with actual classes.

Figure 9 shows the conflicting clusters after the k-means clustering. The clusters are colored purple and yellow (circles), respectively. Correctly formed clusters correspond to those groups that have good alignment with the true labels (shown with blue crosses). By contrast, conflicting clusters contain data points belonging to different true labels (represented by red crosses within the same cluster), indicating separation errors or conflicts in the cluster assignment. Conflicting clusters after Agglomerative and BIRCH clustering of German and Australian datasets are shown in Figure A1 and Figure A2 in the Appendix A.

Figure 9.

Conflicting clusters of Taiwan dataset after k-means.

8.2. Model Performance Regarding Clustering Metrics

The objective was to analyze the evolution of the metrics as a function of the silhouette scores and ARI for each dataset. We would like to determine whether better clustering corresponds to better model performance.

The analysis in Table 20 reveals a clear relationship between clustering quality and performance on other evaluation metrics, such as MCC, AUC, precision, and overall ACC. The clustering quality improved; noticeable improvements were observed in these performance metrics for all models across the datasets. The Australian dataset showed an exceptionally high silhouette score of 0.9598, corresponding to an ARI of 0.0024, indicating the best overall performance for the evaluation metrics in this study. The Australian dataset provided the best improvements in MCC, AUC, and ACC. This improvement demonstrates that the good quality of the clustering is ultimately beneficial for the model’s performance.

Table 20.

k-means performance regarding silhouette score and ARI.

As shown in Table 21, a higher clustering quality of the Agglomerative is associated with better performance on several different evaluation metrics, including MCC, AUC, precision, and overall ACC.

Table 21.

Agglomerative performance regarding silhouette score and ARI.

The same trend was observed for the BIRCH clustering, as shown in Table 22, which indicates that better clustering quality is linked to better predictive performance, as shown by the results of the k-means and Agglomerative clustering approaches.

Table 22.

BIRCH performance regarding silhouette score and ARI.

Thus, although the silhouette scores provide an indication of the quality of cluster separation, they are not sufficient to guarantee that the clustering corresponds to the structure of the real classes. The improved performance we observe arises not from accurate class replication (as measured by ARI), but from the ability of clustering to highlight local data patterns that individual classifiers learn differently.

9. Case of Multiclass Classification

9.1. Description of Credit Score Multiclass Dataset

The Credit Score Classification dataset [43] used contains 100,000 instances divided into three classes: poor (0) 28,998 (29%), standard (1) 53,174 (53%), and good (2) 17,828 (18%). It comprises 28 variables (27 explanatory + 1 target). After selecting the characteristics, 20 variables were retained, with a slight improvement in accuracy (from 0.7872 to 0.7892). Missing values and outliers are also considered. The dataset was unbalanced, with less representation of the “good” class. This dataset was used to extend the proposed approach to multiclass classifications. For the number k of clusters we chose the length of the class (3).

9.2. Experimental Results

The results obtained using the multiclass credit score dataset are presented in Table 23 and Table 24. A comparative analysis of the different classification approaches (Routes 1 to 5) revealed the superiority of hybrid approaches that integrate unsupervised techniques and SOM. The individual models (Route 1) performed the worst overall on all indicators (MCC, AUC, ACC, recall, precision, and Type I and II errors), with MCC values below 0.66 for all models except RF and k-NN. Conversely, Routes 2 to 5 show a significant improvement, particularly Routes 4 and 5, which incorporate both SOM consensus models and clustering techniques. Route 2 (SOM consensus) stands out for its excellent overall performance (MCC, 0.6674; AUC, 0.9084; ACC, 0.7979), which is often close to or equal to that obtained with Routes 4 and 5. However, Routes 4 and 5 refine the classification slightly, particularly for certain sensitive classes (reduction in Type I and II errors). This improvement remains modest but significant in contexts where class accuracy and robustness against false negatives are critical. Therefore, although Route 2 is already very powerful, Route 5, particularly in combination with BIRCH, offers the most complete solution for multiclass processing of complex data. Route 5 (BIRCH and SOM) achieved the best values for MCC (0.6702), AUC (0.9067), and ACC (0.7970), while maintaining a good balance between recall (0.7958) and accuracy (0.7875). In terms of errors, this configuration showed the best results for Type I errors for Class 2 (0.0534), as well as low Type II errors, particularly for Classes 1 and 2. These results confirm that integrating clustering techniques with SOM enables more relevant structuring of data, leading to an overall improvement in classification performance, particularly in the complex context of multiclassing. Although some isolated models (e.g., GBDT, RF, or k-NN in Route 1 or 3) show good results over time, they struggle to maintain the overall stability across all classes. Conversely, the SOM-based consensus models (Routes 2, 4, and 5) delivered robust and balanced performance, confirming the value of these hybrid approaches for processing complex multiclass data.

Table 23.

Model performance for All Routes—Credit Score Multiclass Dataset (Part 1).

Table 24.

Model performance for All Routes—Credit Score Multiclass Dataset (Part 2).

9.3. Comparison with Binary Classification

Hybrid approaches that integrate clustering techniques with SOM, particularly Route 5, offer the best performance for binary and multiclass classifications. Although the gains are more pronounced in binary classification (particularly on the German and Australian datasets), multiclass classification also benefits from a notable improvement, with better stability and a good balance between metrics.

10. Discussion and Limitations

The results obtained herein confirm the effectiveness of the proposed method and extend and improve the reference work [10]. Reference restricted the feasible search space through early classifier restrictions, which reduces the ability of the model to explore potential solutions. By contrast, our method broadens the search space, providing more flexibility for the model to identify optimal outcomes (see Table A2 in the Appendix B). Through iterative improvements, the algorithm has sufficient time to optimize the weights and converge to the best possible values. In addition, a grid search before re-fitting ensures that the model is retrained on a diverse dataset with the best hyperparameters to maximize accuracy.

We also grouped all datasets into (binary class) clusters based on the elbow method and confirmed this choice using the silhouette score, a metric that quantifies how well each data point fits into its assigned cluster. It is worth noting that both the elbow method and silhouette tend to favor low k, especially in imbalanced datasets. This preference for a low k can lead to an oversimplification of the data, where important underlying patterns may be missed, particularly in more complex datasets. Consequently, the generalization ability of the model may be compromised, as the clustering process might fail to capture the full variability in the data, potentially limiting the robustness of the consensus model. By contrast, the reference study chose for the German and Australian datasets. However, using a higher number of clusters can result in fragmented and less meaningful clusters, reducing the overall clustering quality and complicating the analysis. For , our model offers a simpler, more interpretable, and more robust structure.

Analysis of the results across different models and configurations for Routes 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 reveals key insights into the strengths and weaknesses of the classical and cluster-based approaches. Although each dataset has its own particularities, Route 2, 4 and 5 have demonstrated the ability to deliver the best performance. This confirmed that the integration of clustering techniques with SOM represents a particularly robust and effective approach for processing complex data. SOM provides insights that go beyond noise reduction. SOM does not simply create arbitrary partitions, but groups prediction vectors according to their joint structure, thus enabling majority voting informed by classifier agreement rather than independent votes. This confirmed that the integration of clustering techniques with SOM represents a particularly robust and effective approach for processing complex data.

This study also analyses the relationship between clustering quality (measured by silhouette score and ARI) and classification model performance, in order to determine whether better clustering correspond to better predictive performance. The results obtained from the datasets highlight the crucial role of integrating clustering techniques, especially hybrid approaches with self-organizing maps (SOMs). The integration of the SOM model with clustering techniques notably enhances the classification performance compared with individual models, thereby emphasizing the importance of consensus in improving precision, recall, ACC, and AUC. Hybrid approaches, such as those combining k-means, BIRCH, or Agglomerative clustering with SOM, have yielded promising results, confirming that the integration of clustering techniques contributes to improved data structuring and more effective detection of positive classes. Among the various configurations tested, Route 5 was the most effective, particularly when employing Agglomerative or BIRCH clustering, offering the best balance between precision, recall, and error rates. Furthermore, the aggregation of SOM model predictions provides greater stability and robustness in the results, leading to an overall performance improvement compared with clustering models alone. A high silhouette score and a poor ARI (close to zero) indicate that the clustering algorithm has found well-separated clusters that do not correspond to the target classes. Therefore, the benefit of clustering may come from discovering alternative data structures, not from alignment with true class boundaries.

The hyperparameters of hierarchical clustering methods have a significant influence on the results. Although we used default values for our tests, we recognize that adjusting these hyperparameters, such as the distance threshold, branching factor, or number of clusters, could improve the quality and robustness of the clustering, depending on the specific characteristics of the data. We suggest that further hyperparameter testing be carried out to assess the impact of different settings on overall performance.

Our experiments have demonstrated significant improvements in model performance across multiple datasets and classifiers. However, a major limitation of our study is the absence of statistical significance tests and uncertainty quantification to validate these improvements. Indeed, the absence of such analyses prevents us from rigorously confirming whether the observed differences are statistically significant or whether they may be due to random fluctuations. Although the use of performance improvements across different datasets and classifiers has been adopted as an indicator of robustness, we recognize that this approach is not a substitute for formal significance tests.

Also the choice of 80/20 ratio for dividing the data into training and test sets was adopted to prioritize model training and for simplicity, it is possible that a relatively small test set (20%) may not sufficiently reflect the diversity of the data, which could undermine the robustness of the model evaluations. Distributions such as 70/30 or 60/40 would likely offer a better compromise, allowing for both more representative training and a more reliable evaluation of the model’s performance on unseen data. To overcome this limitation, we used 5-fold cross-validation, which strengthens the robustness of the model selection process. However, it remains relevant to explore different data splitting strategies and validate their impact on the overall performance of the model.

11. Implications and Contributions

This research demonstrated the general strengths of Self-Organizing Maps to model complex data, particularly in consensus configurations (Route 2) and approaches based on clustering techniques (Routes 4 and 5). These methodologies contribute to a significant improvement in classification performance, particularly when the data present complex internal structures that are difficult to obtain with conventional supervised learning algorithms.

By organizing data through SOM, the models benefit from improved structure recognition, which translates into better classification metrics such as MCC, AUC, and ACC. The consensus strategy increases the model stability and robustness, whereas the integration of clustering techniques enables a more meaningful segmentation of the data before classification. These findings support the hypothesis that clustering quality reflected by high silhouette scores and appropriate ARI can directly influence model effectiveness.

The use of SOM to organize data before classification proves to be especially relevant in real-world scenarios, such as credit scoring or fraud detection, where balancing multiple performance indicators is critical. In these domains, high recall is essential to effectively detect positive cases. However, minimizing Type I and Type II errors is equally important to avoid false alarms or missed detections.

In addition, this study emphasizes the importance of cost-sensitive evaluation in areas such as credit scoring, where classification errors have significant financial consequences. Although we did not include metrics such as the F1-score, which combines both precision and recall, we chose to use the MCC (Matthews Correlation Coefficient), a metric that, like the F1-score, is sensitive to false positives and false negatives. The MCC proves particularly robust in situations of class imbalance, as it considers all values in the confusion matrix (including true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives). However, specific cost-sensitive metrics such as expected loss, misclassification cost, and profit-based criteria are essential for a more accurate and cost-sensitive evaluation of models. Although these aspects are outside the scope of this replication and extension study, we emphasize that they are of great importance for the practical implementation of models in credit scoring systems.

This research also demonstrated the importance of cluster structure in model performance, from a practical point of view. Datasets with better-defined clusters tend to produce better classification outcomes when used in hybrid models. This implies that the quality of the clustering has a direct impact on the model’s ability to classify data correctly; therefore, clustering should not be treated only as a preprocessing step but as a strategic component of the modeling pipeline.

Compared to other paradigms such as reinforcement learning, rule-based learning, neuro-symbolic AI, and neuromorphic engineering, our approach stands out for its ability to efficiently process static tabular data and capture complex non-linear relationships between borrower characteristics. Although each paradigm has its own advantages and limitations, the hybrid approach we propose is suited to credit scoring data and the needs of financial institutions. Furthermore, our methodology offers a significant economic advantage over alternative paradigms. It delivers improved performance with low development, implementation and execution costs. Our method uses algorithms (k-means clustering, hierarchical clustering, SOM, standard classifiers) that are well understood, stable and widely available in open-source libraries such as Scikit-learn. It can be run on standard hardware (CPU) without the need for specialised infrastructure. It requires expertise in ‘classical’ data science, a more common and less expensive resource than expertise in RL or neuromorphic engineering.

Once trained, the model is very fast to execute. The prediction for a new applicant consists of assigning them to a cluster, calculating the classifiers’ prediction on the enriched data, and then aggregating the results via SOM consensus. This computationally inexpensive process can easily be scaled to process thousands of credit applications on standard infrastructure. This could facilitate its adoption by institutions without excessive investment. Even a marginal improvement in scoring accuracy (reduction in false positives and false negatives) translates into direct and substantial savings in terms of reduced payment defaults and financial losses. The development and execution costs are low compared to these potential benefits. The proposed framework can be extended to other structured datasets for credit scoring. Nonetheless, the performance outcomes may vary due to differences in dataset characteristics such as feature heterogeneity, class imbalance, or sample size.

12. Conclusions and Future Directions

Recent literature has reached a consensus on the fact that hybrid methods are consistently superior to standalone methods in assessing credit risk. this work extends this paradigm by examining how the use of various clustering techniques affects ultimate classification effectiveness. The benefits of applying clustering and consensus techniques to classification were verified. Integrating a clustering method and a classifier is critical because it determines how the performance of the model will be better or worse. The effectiveness of clustering affects the performance of the classifier in terms of making correct predictions. A good clustering process can support the classifier, whereas poor clustering can seriously harm the classifier when making predictions. Thus, careful consideration should be given to the clustering phase because it ensures that the integrated model achieves the best results. This implies that attention should be given in practice to (i) the quality of cluster separations in preprocessing phases, (ii) the choice of the clustering algorithm in such a way that it matches the structure of the data, and (iii) using consensus models in complex and unbalanced contexts as robust solutions.

While this study provides a thorough understanding of the various clustering algorithms, it remains limited to the theoretical aspects of the knowledge without fully consider the practical experience or skills needed to apply them effectively in real-world contexts. The impact of these algorithms in complex situations remains to be explored.

Future research will include statistical tests significance (e.g., McNemar and bootstrap confidence intervals), uncertainty quantification to determine more reliably whether the observed performance improvements are truly significant. These analyses will validate the conclusions of this study and provide a more rigorous assessment of the impact of different approaches on model performance. Also treating cases where there is a high separation between clusters (high silhouette score) and strong alignment with real classes (high Adjusted Rand Index) could lead to a better performance. Another study integrated other clustering algorithms, such as DBSCAN combined with SOM models, to obtain better clustering results. In addition, it would be interesting to use other complex data types, such as time series, to improve the existing knowledge on the behavior of clustering and the SOM model in different environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G.A.; methodology, R.G.A.; software, R.G.A.; validation, R.G.A.; formal analysis, R.G.A., T.S., I.M. and M.A.; investigation, R.G.A.; resources, R.G.A.; data curation, R.G.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.G.A.; writing—review and editing, T.S., I.M. and M.A.; visualization, R.G.A. and M.A.; supervision, T.S., I.M. and M.A.; project administration, R.G.A., T.S., I.M. and M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results of this study can be found in the publicly available datasets referenced in the references section.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACC | Accuracy |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| ARI | Adjusted Rand Index |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BIRCH | Balanced Iterative Reducing and Clustering using Hierarchies |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| GBDT | Gradient Boosting Decision Tree |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| k-NN | k-Nearest Neighbors |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| MCC | Matthews Correlation Coefficient |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| MV | Majority Voting |

| RF | Random Forest |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SOM | Self-Organizing Map |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Conflicting clusters of the Australian dataset after Agglomerative clustering.

Figure A2.

Conflicting clusters of the German dataset after BIRCH clustering.

Appendix B

Table A1.

Metrics used in this study.

Table A1.

Metrics used in this study.

| Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|

| MCC | Balance measure that considers true and false positives and negatives. |

| AUC | Measures the model’s ability to distinguish between classes. |

| ACC | Measures the proportion of correct predictions made by the model. |

| Recall | Measures the proportion of actual positives that were correctly identified. |

| Precision | Indicates the proportion of positive cases that were correct. |

| Type I error | False positive rate: some negative cases are incorrectly predicted as positive. |

| Type II error | False negative rate: the model misses some positive cases. |

Table A2.

Hyperparameter tuning.

Table A2.

Hyperparameter tuning.

| Model | Baseline Paper | Research | Best Parameters Found in GridSearchCV |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANN (MLP) | ann_params = {‘hidden_layer_sizes’: [(i,) for i in range (10, 51)], # hidden_nodes from 10 to 50‘alpha’: [0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1] } | mlp = MLPClassifier(max_iter=2300)param_grid_mlp = {‘hidden_layer_sizes’: [(50,), (100,), (50, 50)],‘activation’: [‘relu’, ‘tanh’],‘solver’: [‘adam’],‘alpha’: [0.0001, 0.001, 0.01],‘learning_rate_init’: [0.001, 0.01, 0.1] } | {‘activation’: ‘relu’, ‘alpha’: 0.0001,‘hidden_layer_sizes’: (50,), ‘learning_rate_init’: 0.1, ‘solver’: ‘adam’} |