Deep-Radiomic Fusion for Early Detection of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Introduction of a hybrid stream design that combines explicit feature selection with attention-based CNNs.

- Presentation of an efficient training pipeline that separates backbone training from fusion fine-tuning.

- Robust evaluation process incorporating classical metrics along with calibration curves and voxel-level heatmaps to enhance clinical interpretability.

- Introduction of a cross-vendor validation approach by assessing generalizability on scans from different CT vendors.

- Comprehensive adherence to and demonstration of community-endorsed best practices, including the Checklist for Evaluation of Radiomics (CLEAR), AI-Ready Imaging Standards for Evaluation (ARISE), European Society of Radiology (ESR) Essentials, Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis—Artificial Intelligence extension (TRIPOD-AI), Findable-Accessible-Interoperable-Reusable principles (FAIR), the Checklist for Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging (CLAIM), the METhodological RadiomICs Score (METRICS) and the Radiomics Quality Score (RQS) guidelines, through transparent data sharing, open code, rigorous validation and full explainability.

Related Work and Contribution

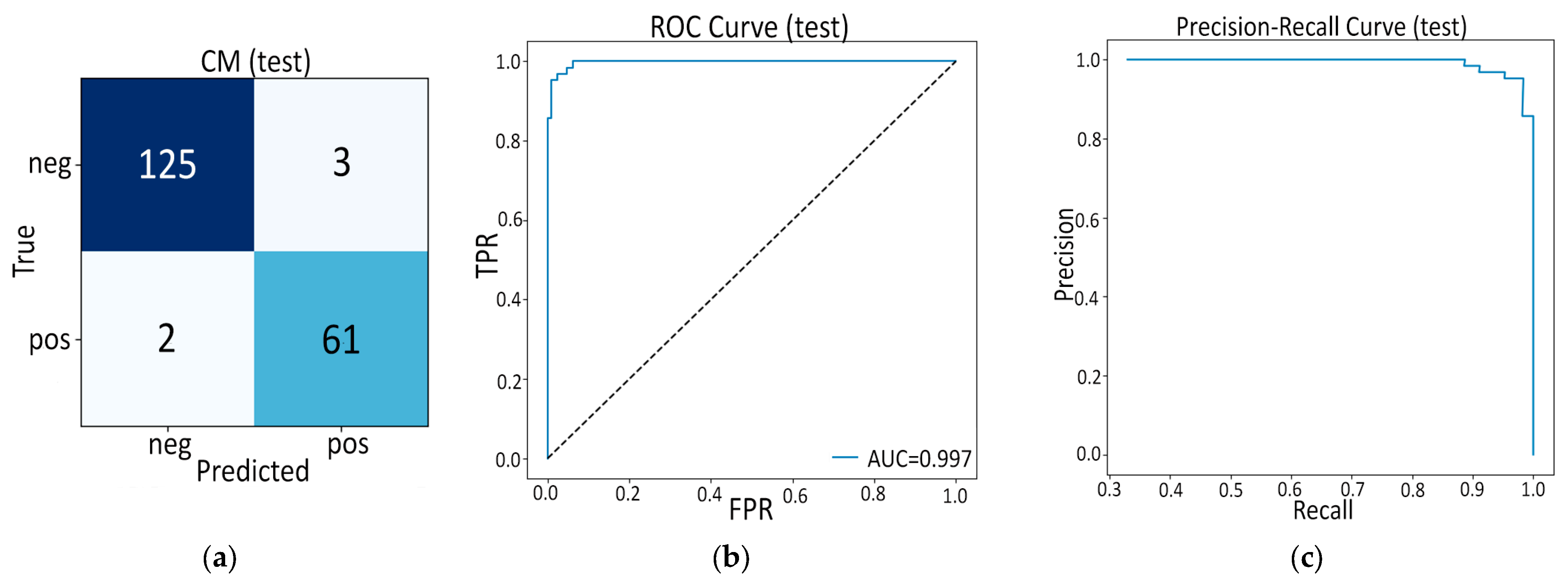

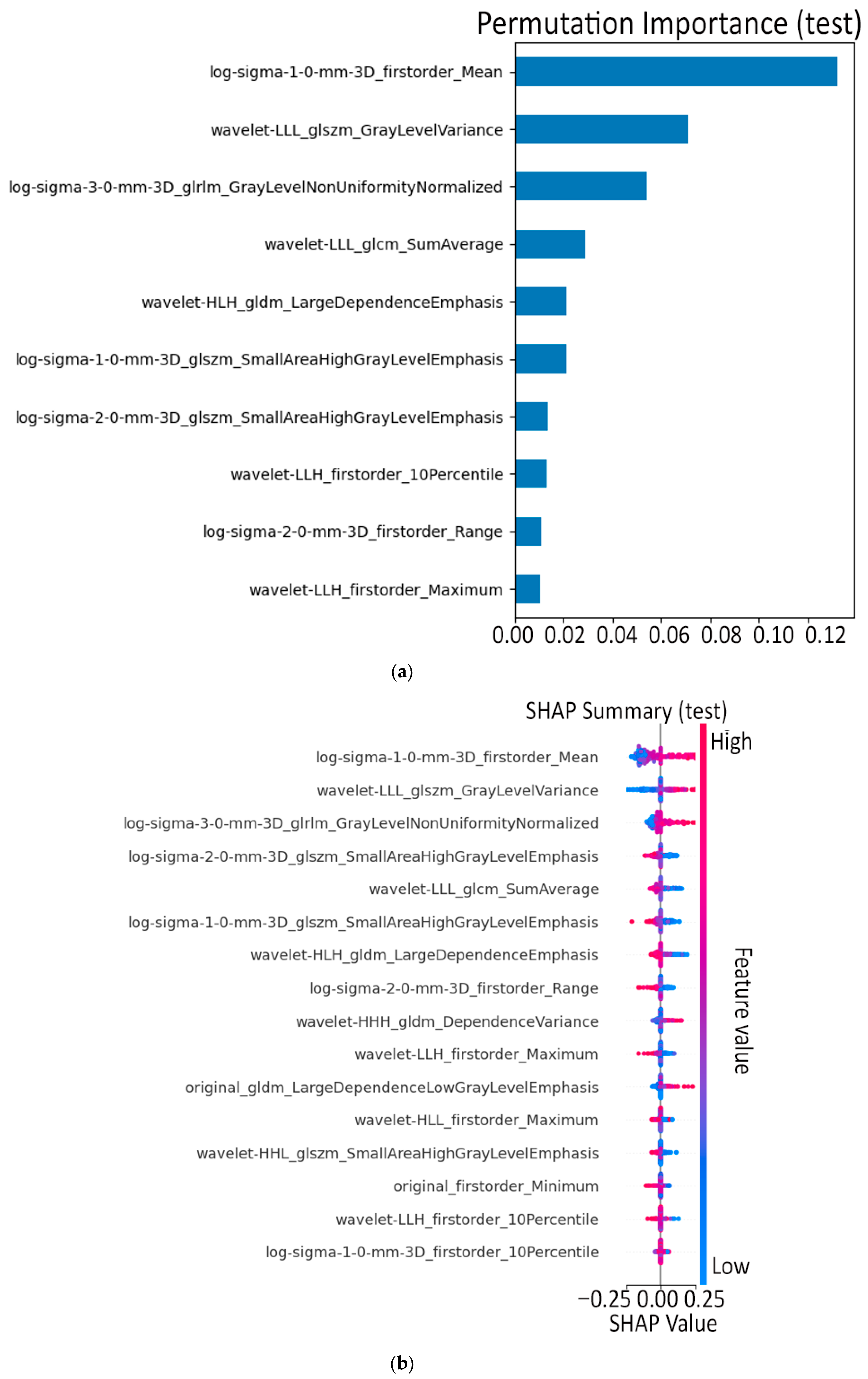

- First, the purely hand-crafted route (Model A, 16 PyRadiomics features + SVM) already sets a very high baseline: internal AUC = 0.997 and external AUC = 0.991 out-strip the 0.90–0.96 range common to earlier radiomics studies such as Ziegelmayer et al. (AUC 0.80) [12] or Dmitriev et al. (83% accuracy on cysts) [11] while retaining excellent calibration (Brier 0.02–0.05). The latter indicates that a carefully pruned, low-dimension radiomic signature, rather than the thousand-feature “kitchen sink” typical of prior work, can be both powerful and transparent.

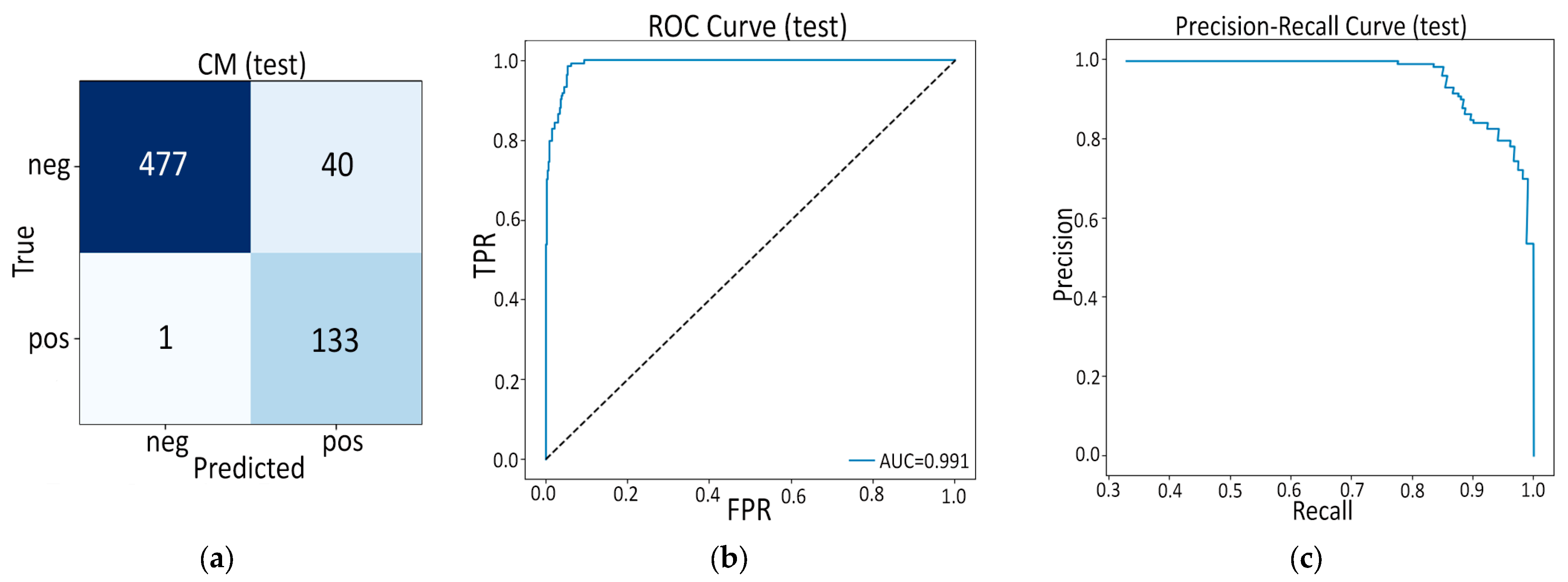

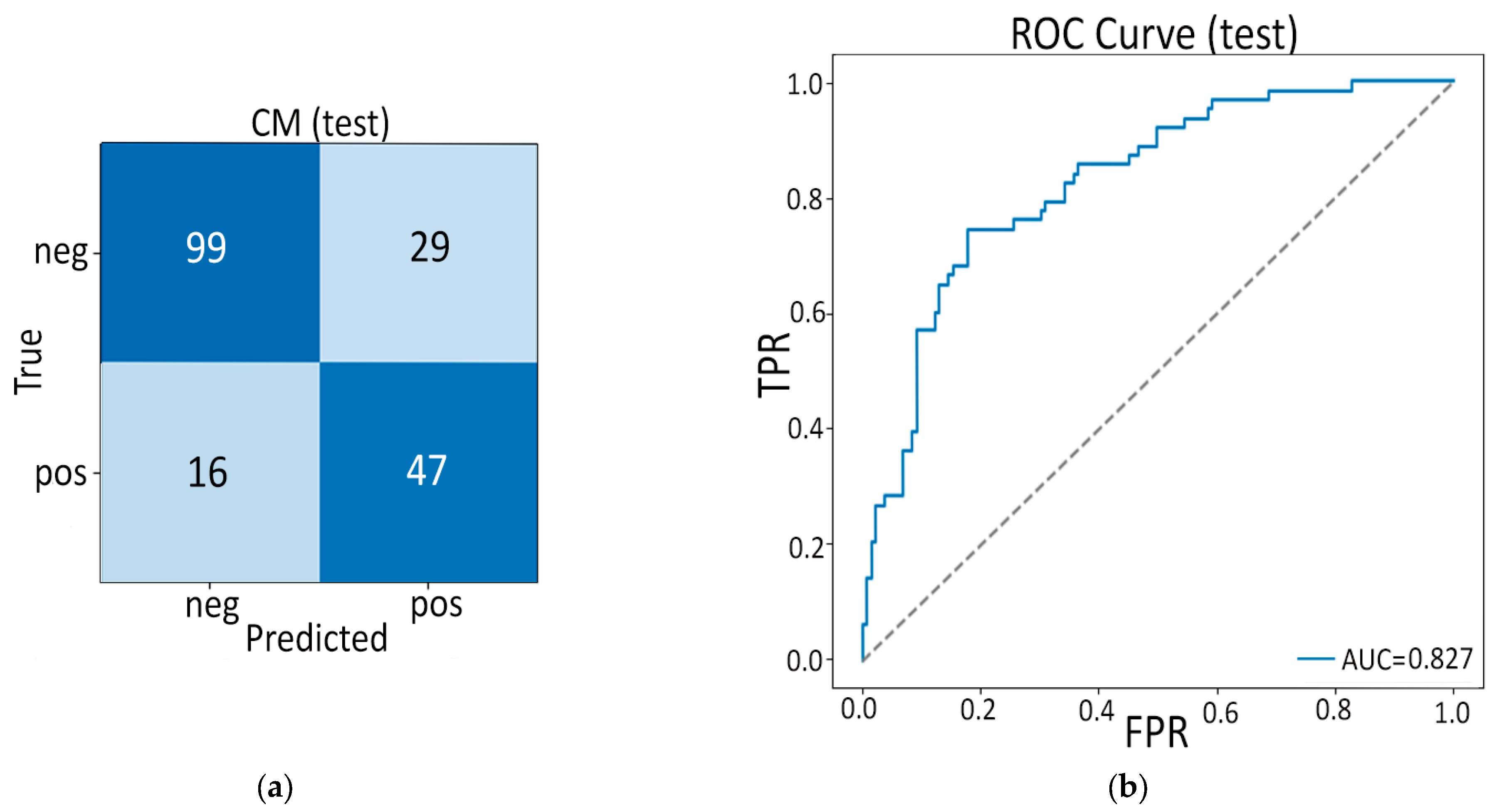

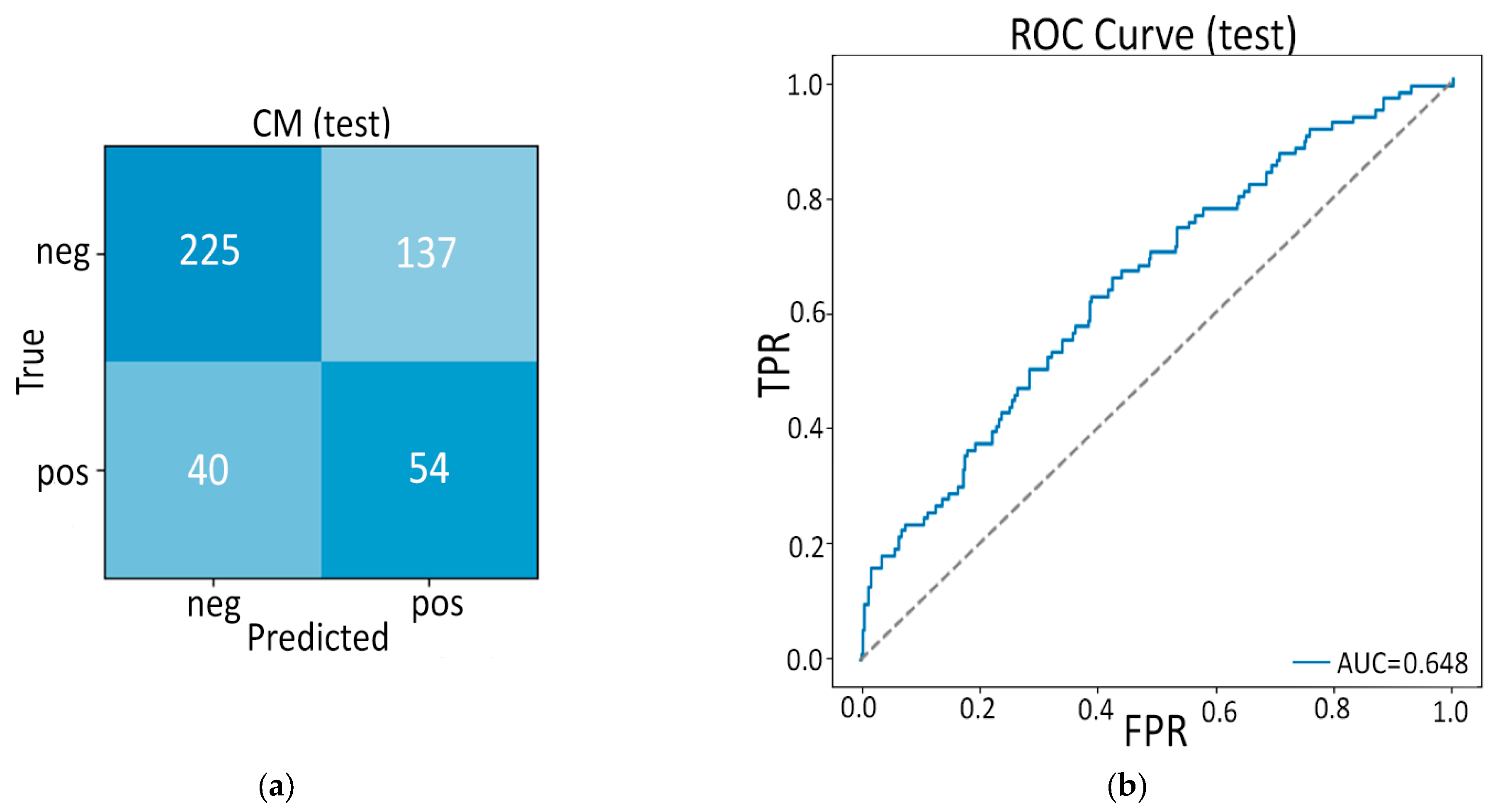

- Second, our end-to-end 3-D CBAM-ResNet-18 (Model B) illustrates the limits of a black-box, deep-only strategy: although it approaches “good” performance in-house (internal AUC ≈ 0.83), generalization falls sharply on the Toshiba cohort (AUC ≈ 0.65). Similar cross-vendor fragility was noted by Yao et al. (MRI, 61–72% accuracy per individual CNN) [15] and even by Wei et al. (PET/CT) [14] when each modality was used alone. These results confirm clinical skepticism surrounding single-stream CNNs for PDAC detection.

- The real advance arises in our fusion experiments (Model C). In the frozen variant (Model C1) we keep the deep and radiomic streams static and train only a 1 k-parameter gating block plus a 6 k-parameter classifier. Even this minimalist fusion lifts external AUC to 0.969—comfortably ahead of the 0.90 reported by Ziegelmayer et al. [12] and on par with the 0.96 achieved by Wei et al. [14] despite their dual-modality input. Crucially, calibration (Brier ≈ 0.07) and specificity (0.917) remain strong, suggesting the gating block successfully suppresses the noisy deep channels that hampered Model B.

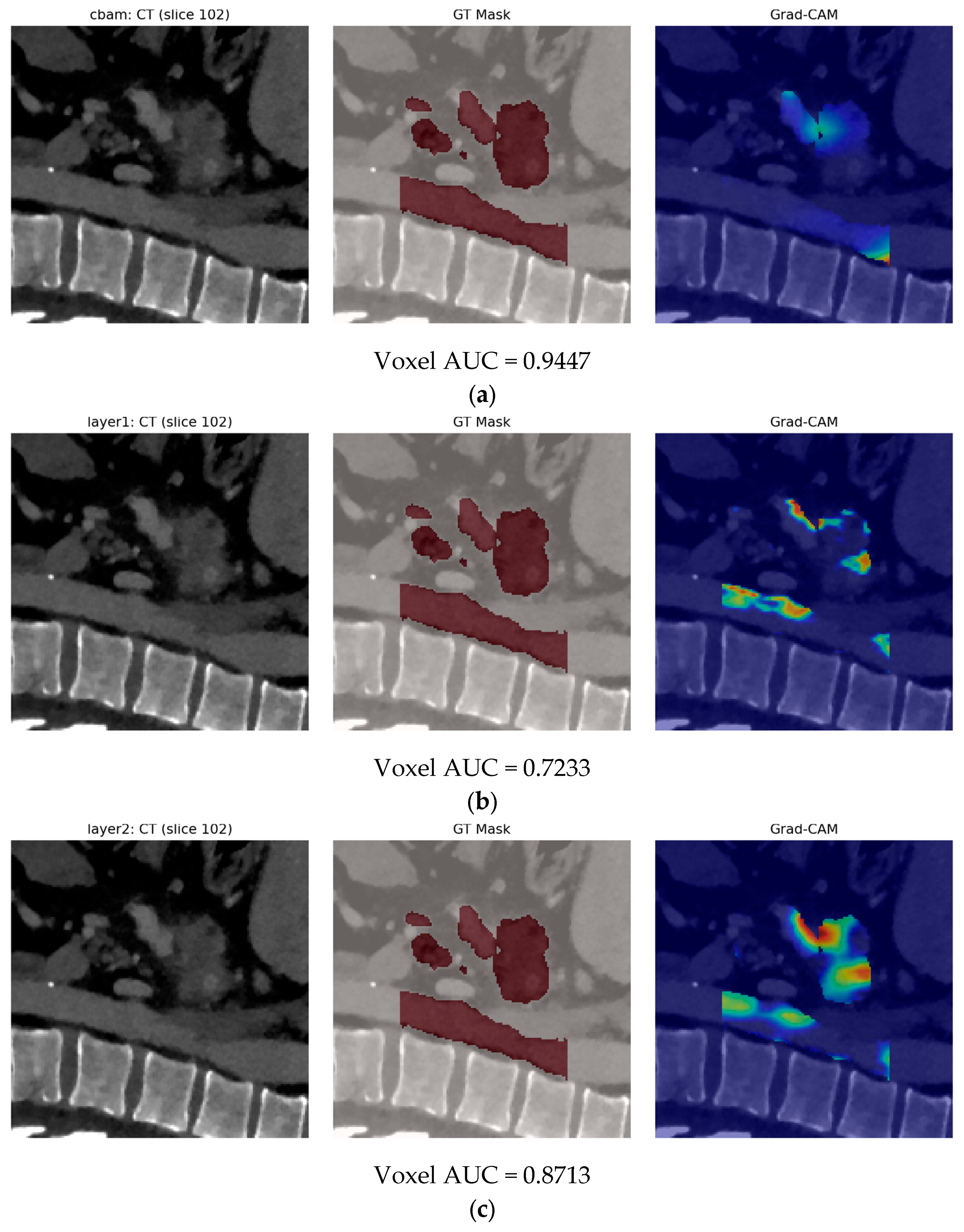

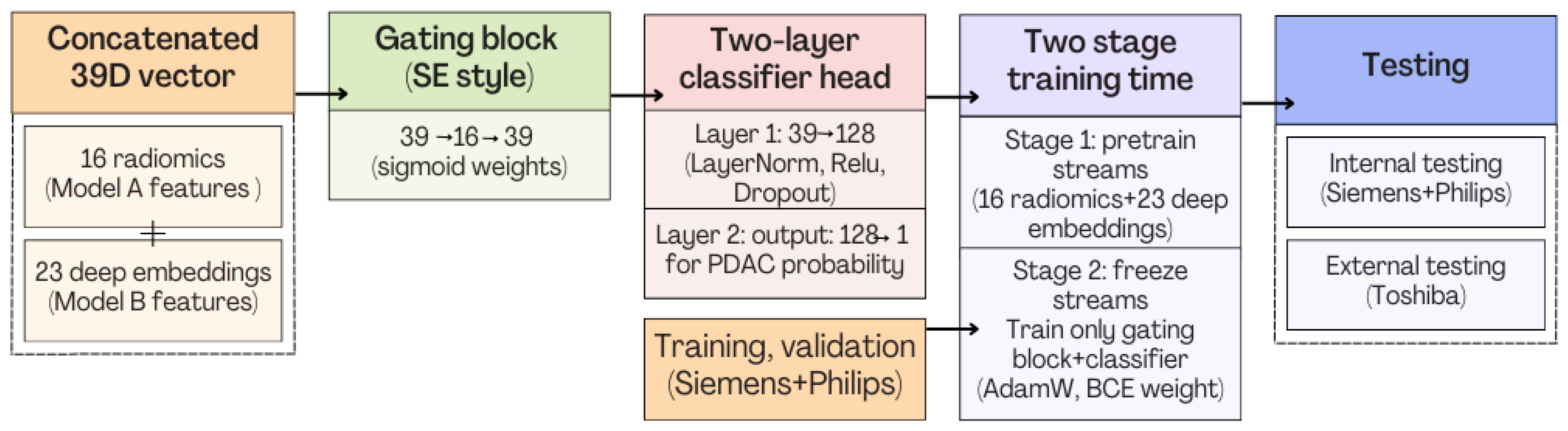

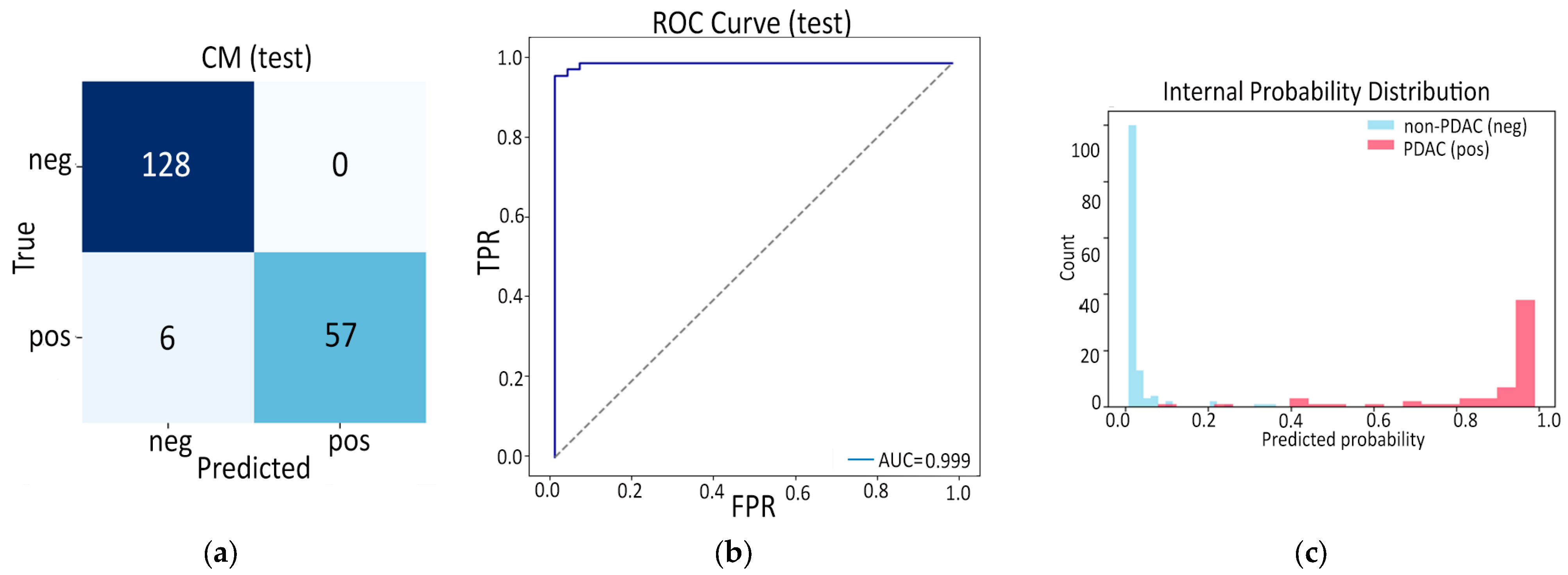

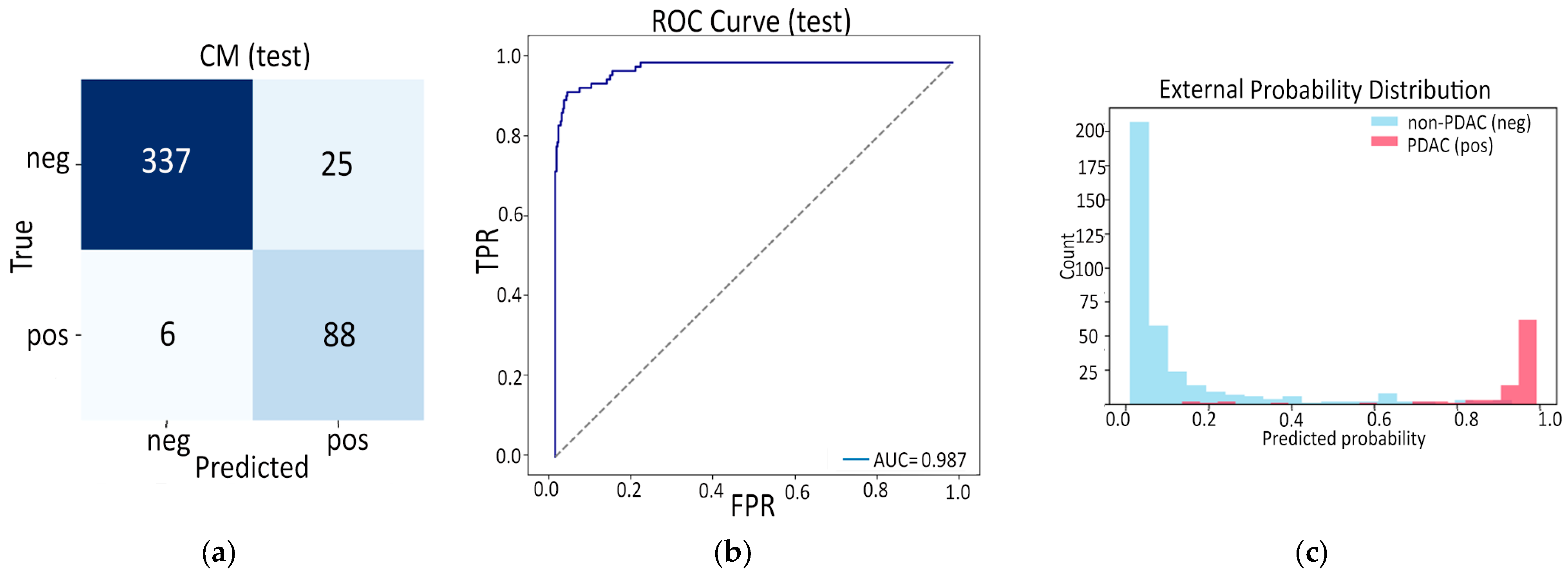

- Finally, Model C2, in which the 23-dim CNN adapter is unfrozen and co-trained with the gate and classifier, pushes performance still further: internal AUC = 0.999, external AUC = 0.987, and perfect specificity (1.000) on Siemens/Philips cases. Grad-CAM overlays confirm that the fine-tuned CNN now zeroes in on the pancreatic head and body—behavior that was far less consistent in the fixed-weight setting and is rarely demonstrated so clearly in earlier fusion papers. By letting the deep stream “listen” to radiomic cues, we appear to alleviate the vendor-shift problem while extracting truly complementary information, accomplishing what Vétil et al. [16] attempted through mutual-information penalties but with a leaner architecture and a 10× smaller training set.

- Beyond the algorithmic and experimental advances, an important component of our work is its uncompromising alignment with the very latest community-endorsed standards for radiomics and AI in healthcare. From the outset we designed and documented every step, data harmonization, automatic segmentation, feature engineering, model training, evaluation and explainability, to satisfy not only the ESR Essentials, CLEAR, and ARISE checklists but also the TRIPOD-AI reporting guidelines, the FAIR data principles, the CLAIM framework and the emerging METRICS and Radiomics Quality Score (RQS) tools. All available material reported in this work is openly archived in a GitHub repository (https://github.com/GeoLek/Deep-Radiomic-Fusion-for-Early-Detection-of-Pancreatic-Ductal-Adenocarcinoma) (accessed on 8 December 2025) in order to encourage transparency, reproducibility and clinical readiness in AI-driven pancreatic cancer detection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset Description

- Siemens + Philips cohort (1257 cases): Used for model development, validation and internal evaluation.

- Training: 70% (880 scans; 592 non-PDAC-Auto, 1 non-PDAC-Manual, 91 PDAC-Auto, 196 PDAC-Manual).

- Validation: 15% (186 scans; class and mask ratios preserved).

- Internal test: 15% (191 scans; 128 non-PDAC, 63 PDAC).

- Toshiba cohort (651 scans): Reserved for true out-of-vendor evaluation.

- Calibration subset: 30% (195 scans; 124 non-PDAC-Auto, 9 PDAC-Auto, 23 PDAC-Manual, 39 non-PDAC-Auto/PDAC balance maintained). These images never updated weights; they served only to set a Toshiba-specific decision threshold.

- External test set: remaining 70% (456 scans; 362 non-PDAC, 94 PDAC) used exactly once for final performance reporting.

2.2. Pre-Processing and Workflow

3. Results

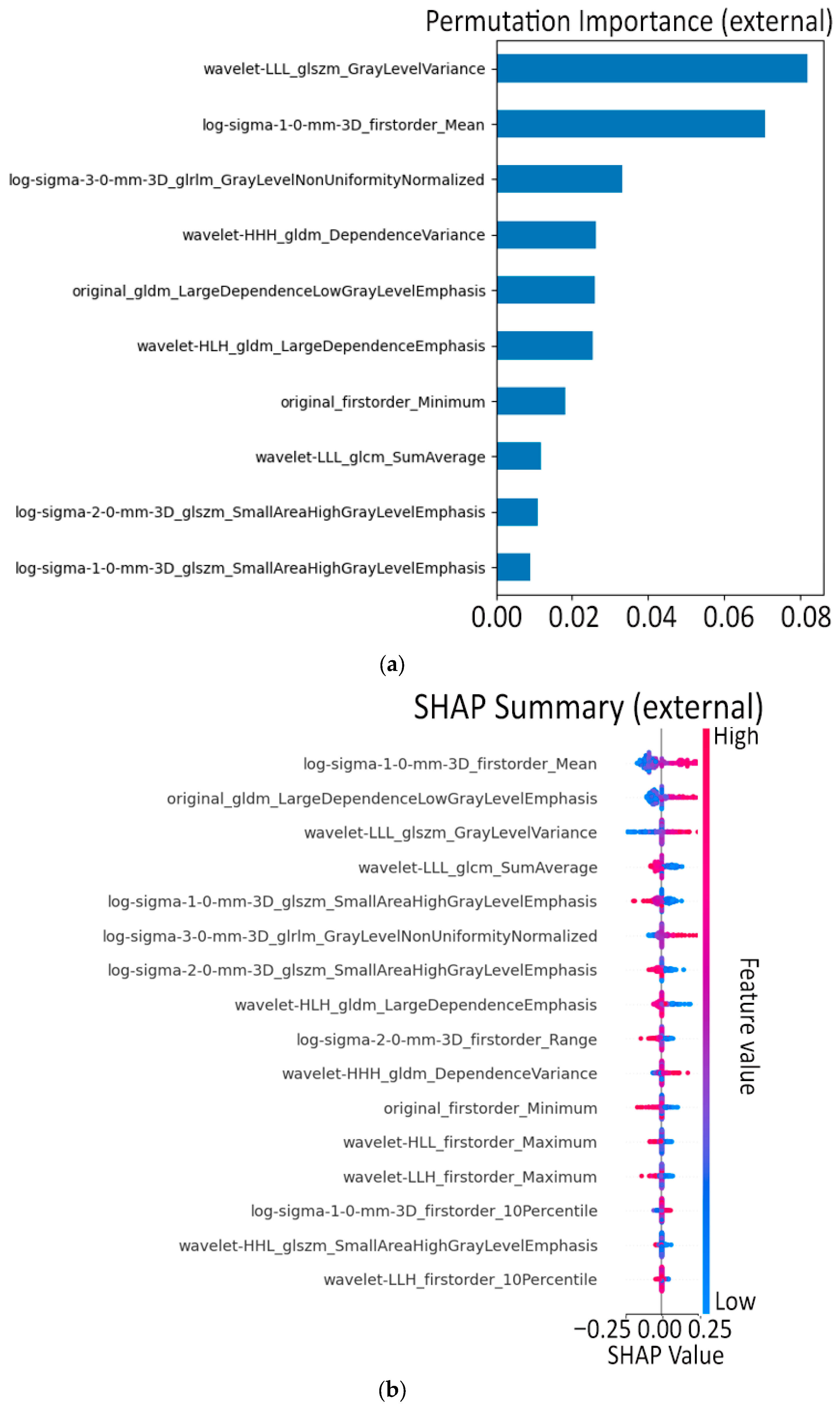

3.1. Model A: Radiomics and Machine Learning

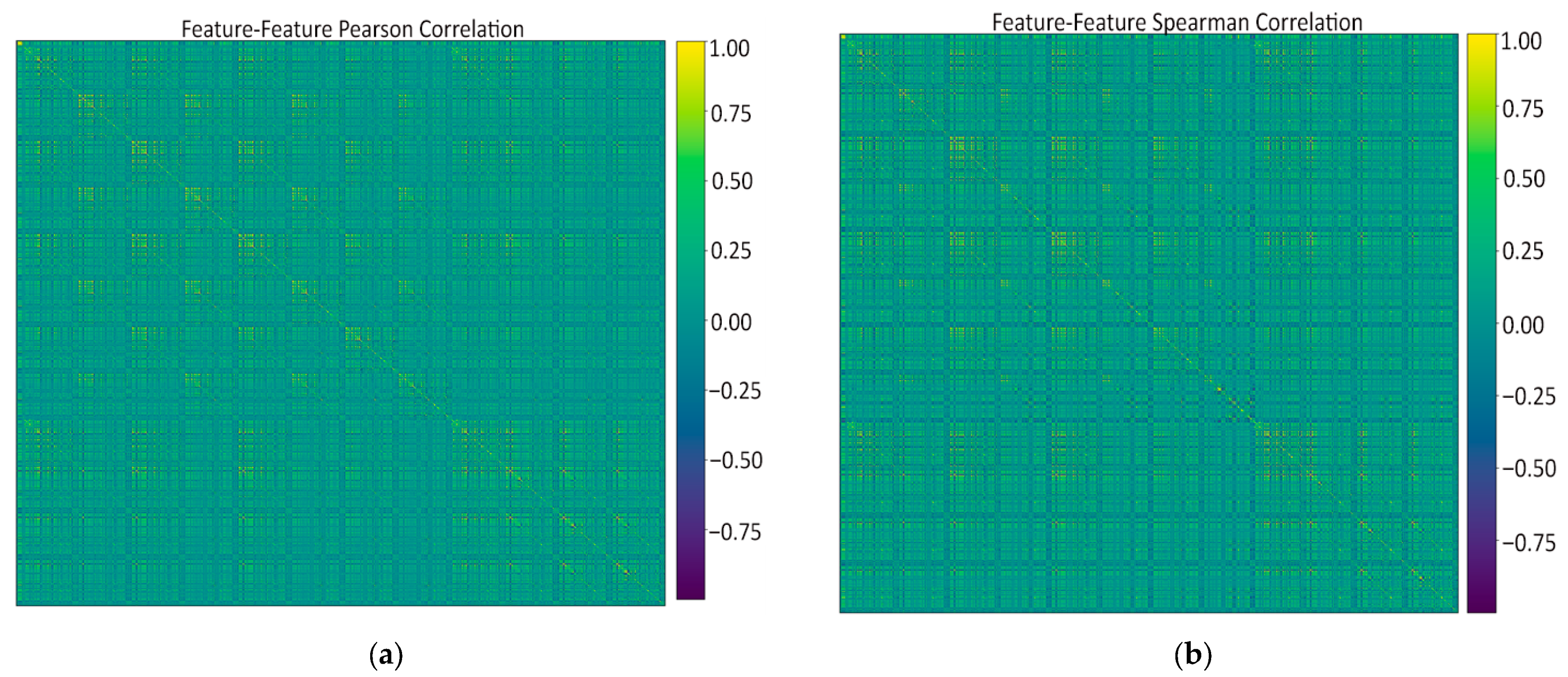

- Feature–feature Pearson heatmap (linear redundancy). A handful of bright off-diagonal blocks revealed groups of first-order and wavelet-based texture features that rise and fall almost in lock-step (|r| > 0.9), while the majority of pairs sat in the mild 0.2–0.5 range. These blocks signaled clear redundancy: it was safe to keep just one representative per block when we later pruned at ρ ≈ 0.9 without losing information.

- Feature–feature Spearman heatmap (monotonic redundancy). The Spearman map looked virtually identical to the Pearson one, confirming that the strong linear ties are also monotonic. Because no “new” high-ρ patterns appeared, a single Pearson-based threshold is enough to catch both linear and non-linear redundancies; no extra non-parametric filtering is needed.

- Feature–class Pearson plot (linear predictive power). Only a small subset of radiomics reached r ≈ 0.6–0.8 with the PDAC label, while most hovered near zero. Those high-r features became prime candidates for univariate selection, but the plot also underlined the need for further pruning as two top-ranked features can still duplicate each other’s signal.

- Feature–class Spearman plot (monotonic predictive power). Ranking the data produced the same short list of standout predictors, indicating that their association with PDAC is robust, not just linear. No feature showed a high Spearman yet low Pearson, so non-linear monotonic effects are minimal; the same top features drive both metrics.

- (a)

- Low-variance cull—attributes that barely varied across patients were dropped.

- (b)

- Univariate ANOVA—the 500 radiomics with the strongest classwise F statistic were retained.

- (c)

- Correlation pruning—within that pool, for every pair whose Pearson |r| exceeded 0.90, the feature with the lower individual F ranking was discarded.

- (1)

- an L1-regularized logistic regression (linear, sparse),

- (2)

- a 200-tree Random Forest (non-linear, bagging), and

- (3)

- an XGBoost ensemble (non-linear, boosting).

- Features jointly selected by Random Forest ∩ XGBoost (17 features) were kept as robust non-linear predictors, and

- Features unique to LASSO but not present in the tree intersection (7 features) were added to preserve complementary linear effects.

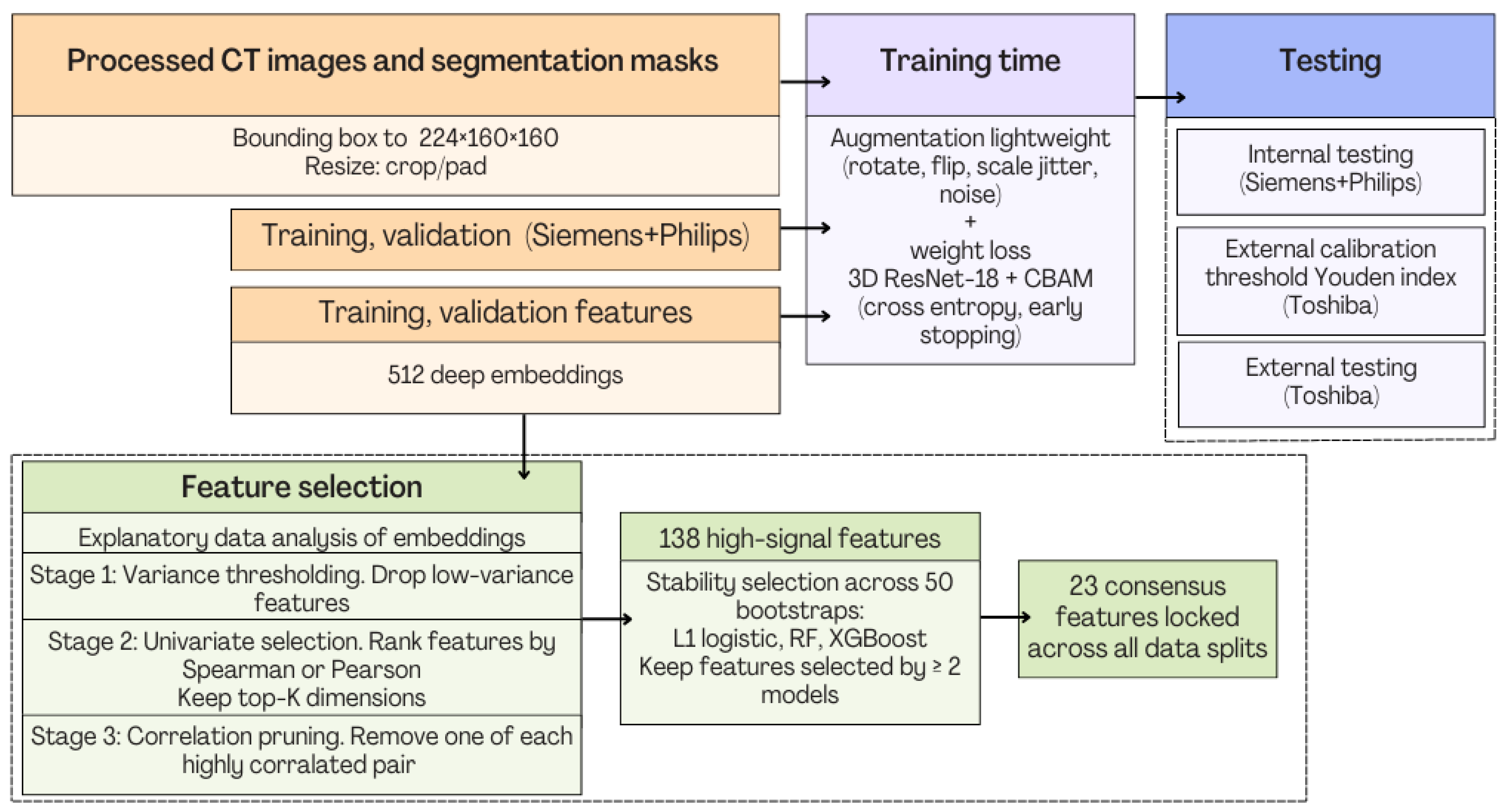

- Pipeline coordination and execution order. All stages in Figure 8 operate in a strictly sequential manner. The workflow therefore executes as follows: image harmonization, feature extraction, feature selection, model benchmarking and internal testing of four models, internal and external testing.

- Computational load. The most computationally expensive stage is the initial PyRadiomics feature extraction, which generates >1000 descriptors per case from original, wavelet, and LoG volumes. This step is GPU-free and parallel, allowing multi-core execution with near-linear speedup. In contrast, the downstream feature selection and pruning operations (variance filtering, univariate ANOVA, and correlation-based pruning) are lightweight.

- No bottleneck in the feature-selection pipeline. Although Figure 8 shows multiple sub-blocks, each operates on a progressively smaller subset of features and therefore executes very quickly. The only resampling and heavy part is the 50-bootstrap model-based stability test which uses simple linear/logistic models and shallow tree ensembles, requiring only minutes on a standard workstation.

- Coordination between blocks. Each block passes a fixed-size output table (CSV/NumPy array) to the next stage. No stage depends on dynamic control flow. The pipeline is therefore robust, modular, and easy to reproduce and as a result, the exact implementation will publicly be released to ensure full transparency.

3.2. Model B: Pure Deep Learning

- Feature–Feature Pearson Correlation. The 512 × 512 Pearson heatmap shows clear, bright blocks along the diagonal—each block (20–60 channels) with r > 0.9 indicates groups of nearly identical deep features. Outside these blocks, correlations drop to 0.3–0.7, and negative correlations are virtually absent. This confirms heavy redundancy and justifies collapsing each block before selection.

- Feature–Feature Spearman Correlation. The Spearman map nearly mirrors the Pearson blocks, showing that those same channel groups also rank-order together, not just vary linearly. A few moderate inter-block ties soften slightly, but no new inverse relationships appear. In short, rank-based redundancy aligns with raw-value redundancy.

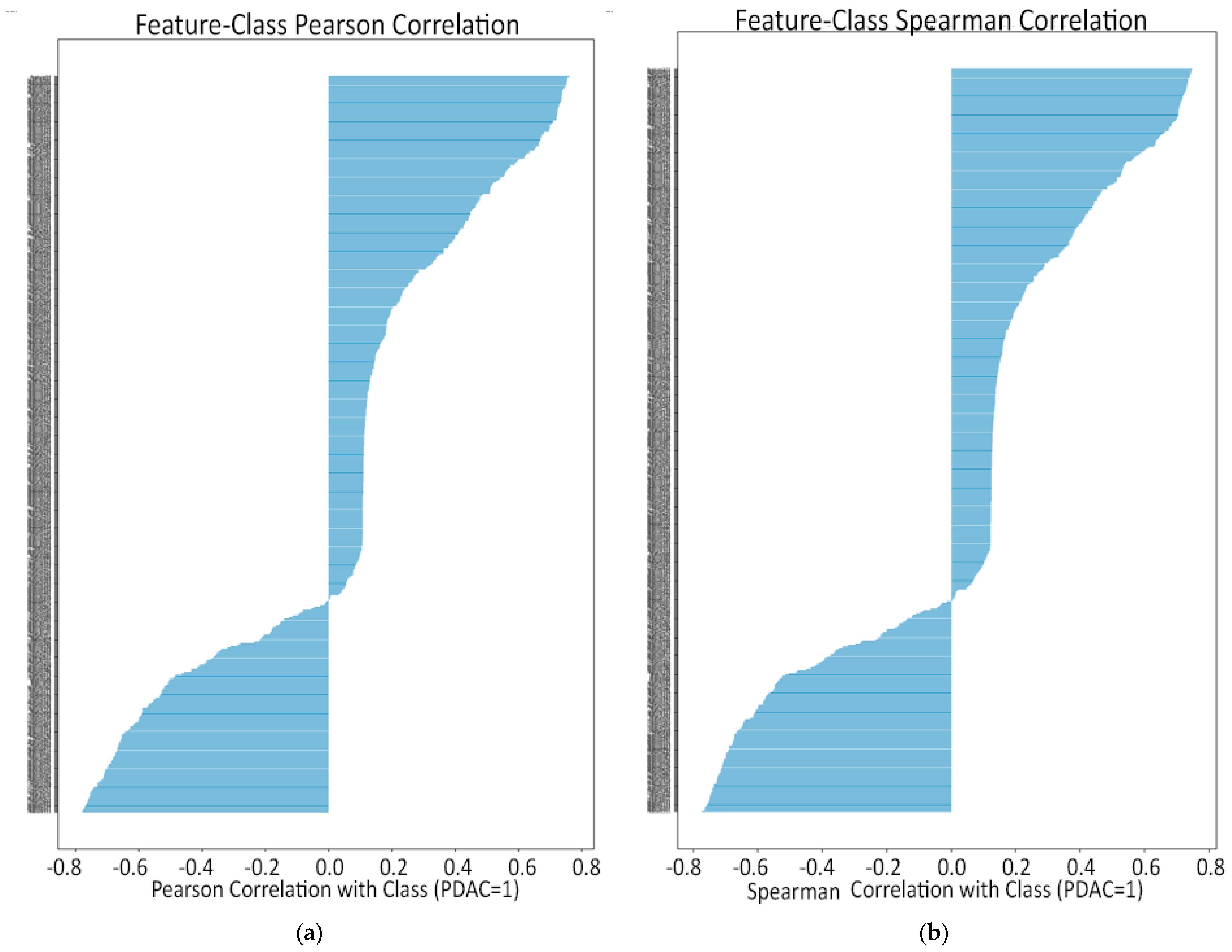

- Feature–Class Pearson Correlation. Ranking channels by Pearson r reveals only a handful with |r| > 0.5 that strongly rise in PDAC or non-PDAC, while most features lie between −0.2 and +0.2. The extreme positive bars pinpoint tumor-sensitive probes; the extreme negative bars flag healthy-tissue detectors. These top correlates guide our univariate filtering.

- Feature–Class Spearman Correlation. The Spearman ranking yields almost the same small set of top channels (ρ ≈ ±0.7–0.8) but shows a sharper drop-off beyond the strongest monotonic features. This tighter “elbow” confirms that only a few embeddings reliably order PDAC above non-PDAC. Those top monotonic channels form a conservative shortlist for selection.

3.3. Model C

3.3.1. Model C1: Two-Stage Frozen Fusion

3.3.2. Model C2: Full End-to-End Fusion Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Evaluation

4.1.1. Guidelines and Good Practices Compatibility

4.1.2. Radiomics Quality Score (RQS)

- Imaging-protocol transparency (+3). All CTs were portal-venous–phase examinations; we report scanner vendor, convolution kernel, section thickness, kVp, and contrast-to-scan delay for the Siemens, Philips, and Toshiba cohorts, and we apply identical preprocessing (LPS re-orientation, 1 mm resampling, −100 to 600 HU clipping, Z-normalization) across every experiment. The protocol description is therefore sufficient for replication and earns full credit.

- Repeat-scan robustness (0). No test, retest or longitudinal duplicate scans were available, so this item scores zero.

- Inter-scanner/phantom assessment (+1). Although we did not image a physical phantom, the model was trained on Siemens + Philips data and tested unchanged on Toshiba volumes, explicitly demonstrating scanner-to-scanner reproducibility; this satisfies the single point allocated for inter-scanner validation.

- Multiple segmentations (+2). Each pancreas was contoured twice: an automatic nnUNet mask (quality-weighted at 0.8) and, when available, a manual mask (weight 1.0). Feature robustness to those alternative ROIs was quantified during feature-selection, fulfilling the full two points for segmentation variability analysis.

- Feature reduction and multiplicity control (+3). From ~1100 handcrafted radiomics and 512 deep features, we applied variance filtering, ANOVA/mutual-information ranking, ρ > 0.9 pruning, bootstrapped L1-logistic + RF + XGBoost stability-selection and, finally, an independent gating mechanism. This rigorous pipeline receives a maximum of three points.

- Biological correlates (0). No histopathology, genomic or laboratory correlation was attempted, so this criterion is not met.

- Pre-specification of cut-offs (+1). Decision thresholds were fixed a priori on the validation split (internal) and a held-out calibration subset (external Toshiba) before any test inference, avoiding data-driven optimization; hence, one point is awarded.

- Multivariable integration with non-imaging data (0). While the framework can readily ingest CA19-9 or demographics, the present work focuses purely on imaging, so no credit here.

- Discrimination statistics with confidence intervals (+2). ROC-AUC, average precision, sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, F1-score, and 95% bootstrap CIs are reported for cross-validation, internal and external tests for every model (A, B, C-frozen, C-E2E). Full marks.

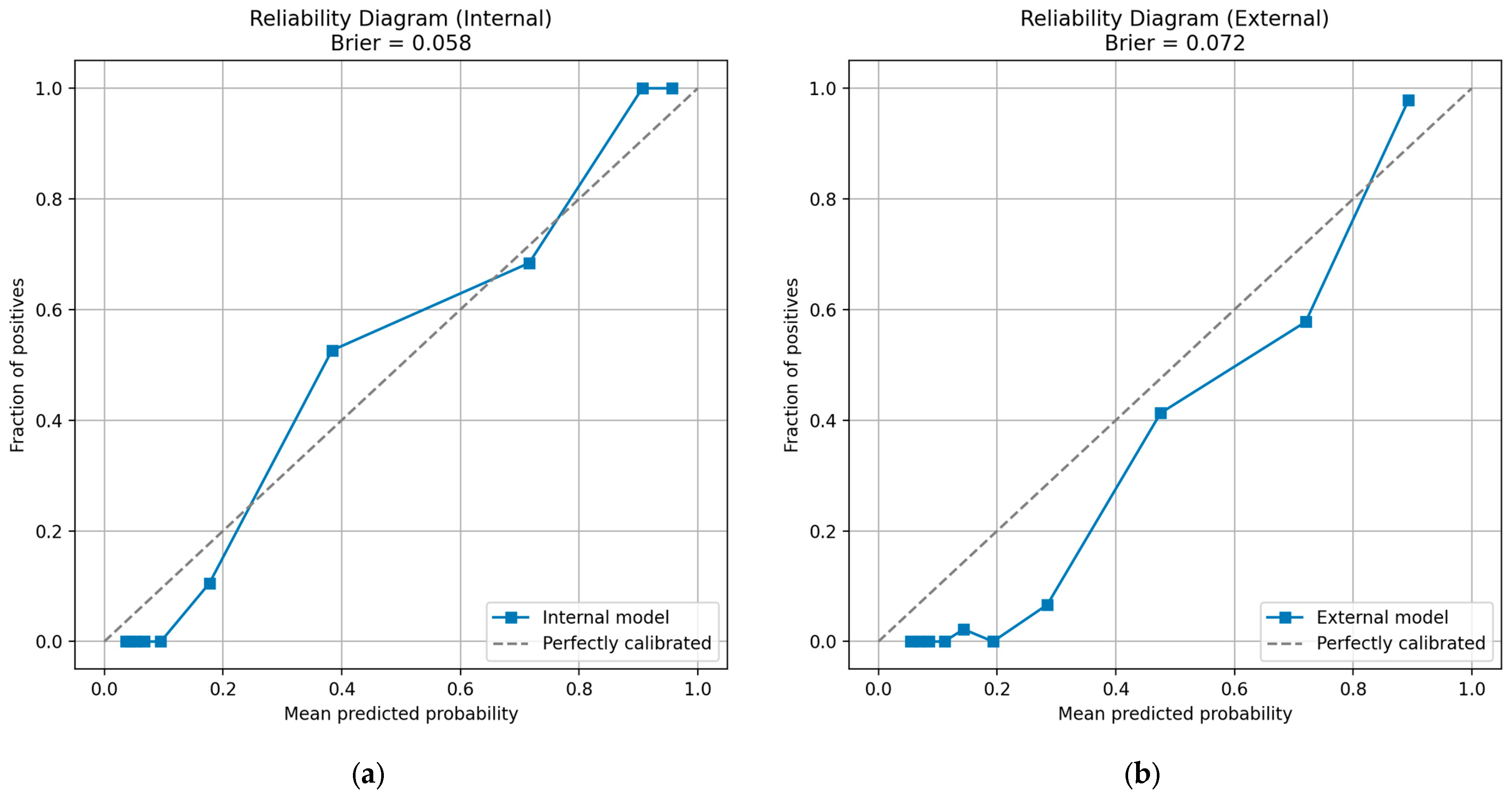

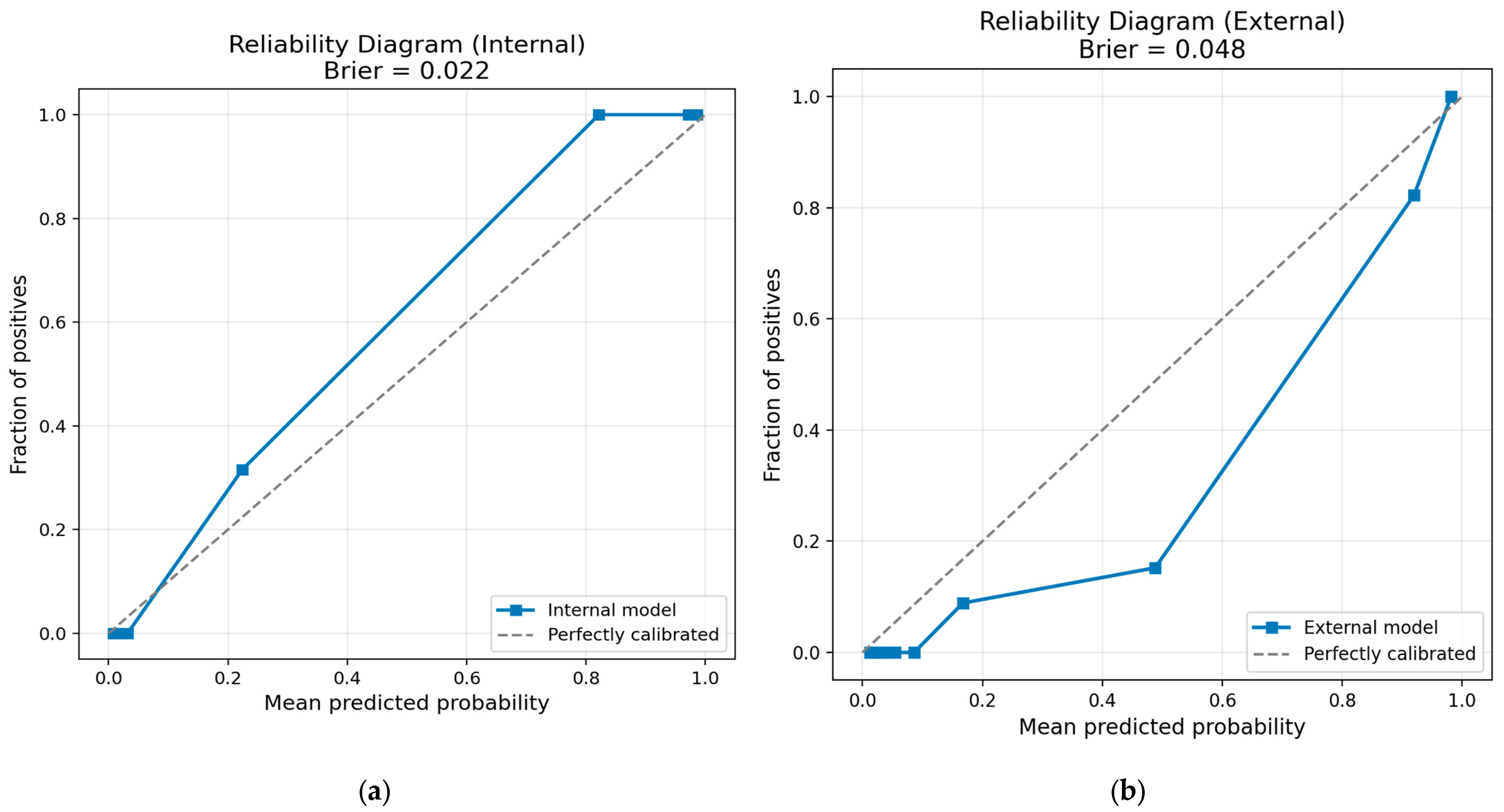

- Calibration statistics (+1). Reliability diagrams and Brier scores (internal 0.022; external 0.048) accompany each fusion model, satisfying the calibration item.

- Internal validation (+1). A stratified 5 × 3 cross-validation scheme on 1257 Siemens/Philips scans, followed by an untouched internal test split (n = 191), secures one point.

- External validation (+4). Blind evaluation on 456 Toshiba scans from a different vendor (AUC 0.987, accuracy 0.932) confers the maximum four-point bonus.

- Prospective design (0). Retrospective analysis only.

- Cost-effectiveness (0). No economic modeling included.

- Open science and data sharing (+2). PANORAMA is an openly accessible, license-free dataset, and we have placed all preprocessing, training, evaluation scripts, model code, trained weights, results, and all available material on a public GitHub repository.

- Potential clinical use (+1). We document run-time (<40 s per case), Docker packaging and PACS integration plans, earning a single point for clinical implementation potential.

4.1.3. METhodological RadiomICs Score (METRICS)

4.2. Insights and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PDAC | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| AI | artificial intelligence |

| IPMNs | Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms |

| MCNs | Mucinous Cystic Neoplasms |

| RF | Random Forest |

| SCAs | Serous Cystadenomas |

| SPNs | Solid Pseudopapillary Neoplasms |

| AIP | autoimmune pancreatitis |

| AJCC | American Joint Committee on Cancer |

| CA | Cancer Antigen |

| LoG | Laplacian-of-Gaussian |

| RQS | Radiomics Quality Score |

| METRICS | METhodological RadiomICs Score |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M. Pancreatic Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1605–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMagno, E.P. Pancreatic Cancer: Clinical Presentation, Pitfalls and Early Clues. Ann. Oncol. 1999, 10, S140–S142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayerhoefer, M.E.; Materka, A.; Langs, G.; Häggström, I.; Szczypiński, P.; Gibbs, P.; Cook, G. Introduction to Radiomics. J. Nucl. Med. 2020, 61, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moumgiakmas, S.S.; Vrochidou, E.; Papakostas, G.A. Mapping the Brain: AI-Driven Radiomic Approaches to Mental Disorders. Artif. Intell. Med. 2025, 168, 103219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nougaret, S.; Tibermacine, H.; Tardieu, M.; Sala, E. Radiomics: An Introductory Guide to What It May Foretell. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 21, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wernick, M.; Yang, Y.; Brankov, J.; Yourganov, G.; Strother, S. Machine Learning in Medical Imaging. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2010, 27, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocak, B.; Durmaz, E.S.; Ates, E.; Kilickesmez, O. Radiomics with Artificial Intelligence: A Practical Guide for Beginners. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2019, 25, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzego, A.; Bussola, N.; Salvalai, D.; Chierici, M.; Maggio, V.; Jurman, G.; Furlanello, C. Integrating Deep and Radiomics Features in Cancer Bioimaging. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Conference on Computational Intelligence in Bioinformatics and Computational Biology (CIBCB), Siena, Italy, 9–11 July 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lekkas, G.; Vrochidou, E.; Papakostas, G.A. Advancements in Radiomics-Based AI for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitriev, K.; Kaufman, A.E.; Javed, A.A.; Hruban, R.H.; Fishman, E.K.; Lennon, A.M.; Saltz, J.H. Classification of Pancreatic Cysts in Computed Tomography Images Using a Random Forest and Convolutional Neural Network Ensemble. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2017; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegelmayer, S.; Kaissis, G.; Harder, F.; Jungmann, F.; Müller, T.; Makowski, M.; Braren, R. Deep Convolutional Neural Network-Assisted Feature Extraction for Diagnostic Discrimination and Feature Visualization in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC) versus Autoimmune Pancreatitis (AIP). J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lobo-Mueller, E.M.; Karanicolas, P.; Gallinger, S.; Haider, M.A.; Khalvati, F. Improving Prognostic Performance in Resectable Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Using Radiomics and Deep Learning Features Fusion in CT Images. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.; Jia, G.; Wu, Z.; Wang, T.; Wang, H.; Wei, K.; Cheng, C.; Liu, Z.; Zuo, C. A Multidomain Fusion Model of Radiomics and Deep Learning to Discriminate between PDAC and AIP Based on 18F-FDG PET/CT Images. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2023, 41, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Demir, U.; Keles, E.; Vendrami, C.; Agarunov, E.; Bolan, C.; Schoots, I.; Bruno, M.; Keswani, R.; et al. Radiomics Boosts Deep Learning Model for IPMN Classification. In International Workshop on Machine Learning in Medical Imaging; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- Vétil, R.; Abi-Nader, C.; Bône, A.; Vullierme, M.-P.; Rohé, M.-M.; Gori, P.; Bloch, I. Non-Redundant Combination of Hand-Crafted and Deep Learning Radiomics: Application to the Early Detection of Pancreatic Cancer. In MICCAI Workshop on Cancer Prevention Through Early Detection; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 68–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Q.; Sun, H.; Liu, P.; Hu, X.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Xing, Y. Multiscale Deep Learning Radiomics for Predicting Recurrence-Free Survival in Pancreatic Cancer: A Multicenter Study. Radiother. Oncol. 2025, 205, 110770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, N.; Schuurmans, M.; Rutkowski, D.; Yakar, D.; Haldorsen, I.; Liedenbaum, M.; Molven, A.; Vendittelli, P.; Litjens, G.; Hermans, J.; et al. The PANORAMA Study Protocol: Pancreatic Cancer Diagnosis—Radiologists Meet AI. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/10599559 (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Altmann, A.; Toloşi, L.; Sander, O.; Lengauer, T. Permutation Importance: A Corrected Feature Importance Measure. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2017/file/8a20a8621978632d76c43dfd28b67767-Paper.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Pinciroli Vago, N.O.; Milani, F.; Fraternali, P.; da Silva Torres, R. Comparing CAM Algorithms for the Identification of Salient Image Features in Iconography Artwork Analysis. J. Imaging 2021, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocak, B.; Baessler, B.; Bakas, S.; Cuocolo, R.; Fedorov, A.; Maier-Hein, L.; Mercaldo, N.; Müller, H.; Orlhac, F.; Pinto dos Santos, D.; et al. CheckList for EvaluAtion of Radiomics Research (CLEAR): A Step-by-Step Reporting Guideline for Authors and Reviewers Endorsed by ESR and EuSoMII. Insights Imaging 2023, 14, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocak, B.; Ponsiglione, A.; Stanzione, A.; Ugga, L.; Klontzas, M.E.; Cannella, R.; Cuocolo, R. CLEAR Guideline for Radiomics: Early Insights into Current Reporting Practices Endorsed by EuSoMII. Eur. J. Radiol. 2024, 181, 111788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocak, B.; Chepelev, L.L.; Chu, L.C.; Cuocolo, R.; Kelly, B.S.; Seeböck, P.; Thian, Y.L.; van Hamersvelt, R.W.; Wang, A.; Williams, S.; et al. Assessment of RadiomIcS REsearch (ARISE): A Brief Guide for Authors, Reviewers, and Readers from the Scientific Editorial Board of European Radiology. Eur. Radiol. 2023, 33, 7556–7560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santinha, J.; Pinto dos Santos, D.; Laqua, F.; Visser, J.J.; Groot Lipman, K.B.W.; Dietzel, M.; Klontzas, M.E.; Cuocolo, R.; Gitto, S.; Akinci D’Antonoli, T. ESR Essentials: Radiomics—Practice Recommendations by the European Society of Medical Imaging Informatics. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 35, 1122–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.S.; Moons, K.G.; Dhiman, P.; Riley, R.D.; Beam, A.L.; Van Calster, B.; Ghassemi, M.; Liu, X.; Reitsma, J.B.; Van Smeden, M.; et al. TRIPOD + AI Statement: Updated Guidance for Reporting Clinical Prediction Models That Use Regression or Machine Learning Methods. BMJ 2024, 385, q902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.-W.; da Silva Santos, L.B.; Bourne, P.E.; et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejani, A.S.; Klontzas, M.E.; Gatti, A.A.; Mongan, J.T.; Moy, L.; Park, S.H.; Kahn, C.E.; Abbara, S.; Afat, S.; Anazodo, U.C.; et al. Checklist for Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging (CLAIM): 2024 Update. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2024, 6, e240300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, P.; Leijenaar, R.T.H.; Deist, T.M.; Peerlings, J.; de Jong, E.E.C.; van Timmeren, J.; Sanduleanu, S.; Larue, R.T.H.M.; Even, A.J.G.; Jochems, A.; et al. Radiomics: The Bridge between Medical Imaging and Personalized Medicine. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocak, B.; Akinci D’Antonoli, T.; Mercaldo, N.; Alberich-Bayarri, A.; Baessler, B.; Ambrosini, I.; Andreychenko, A.E.; Bakas, S.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Bressem, K.; et al. METhodological RadiomICs Score (METRICS): A Quality Scoring Tool for Radiomics Research Endorsed by EuSoMII. Insights Imaging 2024, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study/Model | Imaging Modality | Feature Streams Fused | Cohort Size (Train + Test) | Fusion Strategy | Best Metric * | External/Cross-Vendor | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dmitriev et al. (2017) [11] | CECT (2D) | 14 handcrafted + 2D CNN | 134 cystic–lesion pts | Bayesian RF + CNN ensemble | Acc 0.836 | ✗ | Simple ensemble combining CNN and radiomics | Two-dimensional inputs; small cohort; no external test |

| Ziegelmayer et al. (2020) [12] | CECT (3D) | 1411 PyRadiomics + 256 VGG19 activations | 86 PDAC vs. AIP | Parallel training, no joint tuner | AUC 0.900 | ✗ | Strong radiomics baseline | No true fusion; very small dataset |

| Zhang et al. (2021) [13] | CECT (3D) | 1428 radiomics + 35 TL-CNN | 98 resection pts | Random-forest risk score | AUC 0.840 | ✗ | Straightforward radiomics + TL features | No calibration; no cross-vendor validation |

| Wei et al. (2023) [14] | 18F-FDG PET/CT | PET + CT radiomics + VGG11 | 112 (64 PDAC/48 AIP) | Multidomain weighted fusion | AUC 0.964 | ✗ (single center) | Multi-modal PET/CT input | No multi-vendor, small dataset |

| Yao et al. (2023) [15] | MRI (T1/T2) | 107 radiomics + 5 CNN backbones + clinical | 246 IPMN, 5 centers | Weighted-averaged ensemble | Acc 0.819 | ✓ (multi-site) | Multi-site data; multi-stream | Non-PDAC; limited interpretability |

| Vétil et al. (2023) [16] | CECT (portal) | PyRadiomics + VAE deep-radiomics | 2319 + 1094 | MI-minimizing VAE + LR | AUC ≈ 0.930 | ✗ | VAE-based harmonization | Fusion limited to logistic regression |

| Gu et al. (2025) [17] | CECT (2D crops) | 1688 rad. (intra + peri) + 2048 ResNet-50 | 469 (4 centers) | Cox nomogram | C-index 0.70–0.78 | ✓ | Multi-center prognostic setup | Two-dimensional crops; not diagnostic focus |

| Model A (ours) | CECT (3D) | 16 PyRadiomics (SVM) | 1257 + 456 | No fusion—radiomics only | Internal AUC 0.997/External 0.991 | ✓ | Very strong baseline; interpretable; stable | Limited expressiveness (no deep features) |

| Model B (ours) | CECT (3D) | Three-dimensional CBAM-ResNet-18 | 1257 + 456 | Deep only | Internal AUC 0.827/External 0.648 | ✓ | Produces volumetric Grad-CAM maps | Poor external performance; vendor-sensitive |

| Model C1 (ours) | CECT (3D) | 16 rad. + 23 deep (frozen) | 1257 + 456 | Two-stage frozen gate | Internal AUC 0.981/External 0.969 | ✓ | Parameter-efficient; stable fusion | Deep features fixed; suboptimal adaptation |

| Model C2 (ours) | CECT (3D) | 16 rad. + 23 deep (fine-tuned) | 1257 + 456 | Full end-to-end gate | Internal AUC 0.999/External 0.987 | ✓ | Best performance; calibrated; interpretable | Higher training complexity |

| Metric | Internal Test (Siemens + Philips, n = 191) | External Test (Toshiba, n = 651) |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.974 | 0.937 |

| Sensitivity (Recall PDAC) | 0.968 | 0.993 |

| Specificity | 0.977 | 0.923 |

| Precision (PPV) | 0.953 | 0.769 |

| F1-score | 0.961 | 0.866 |

| ROC-AUC | 0.997 | 0.991 |

| Brier score | 0.021 | 0.053 |

| Metric | Internal Test (n = 191) | External Test (n = 456) |

|---|---|---|

| ROC-AUC | 0.8268 (thr ≈ 0.2913) | 0.6485 (thr ≈ 0.1416) |

| Threshold | 0.2913 | 0.1416 |

| Accuracy | 0.7644 | 0.6118 |

| Sensitivity (PDAC recall) | 0.7460 | 0.5745 |

| Specificity (non-PDAC recall) | 0.7734 | 0.6215 |

| Macro-avg Precision | 0.7396 | 0.5659 |

| Macro-avg Recall | 0.7597 | 0.5980 |

| Macro-avg F1-score | 0.7455 | 0.5483 |

| Weighted-avg Precision | 0.7809 | 0.7323 |

| Weighted-avg Recall | 0.7644 | 0.6118 |

| Weighted-avg F1-score | 0.7691 | 0.6479 |

| non-PDAC Precision/Recall/F1 | 0.8609/0.7734/0.8148 | 0.8491/0.6215/0.7177 |

| PDAC Precision/Recall/F1 | 0.6184/0.7460/0.6763 | 0.2827/0.5745/0.3789 |

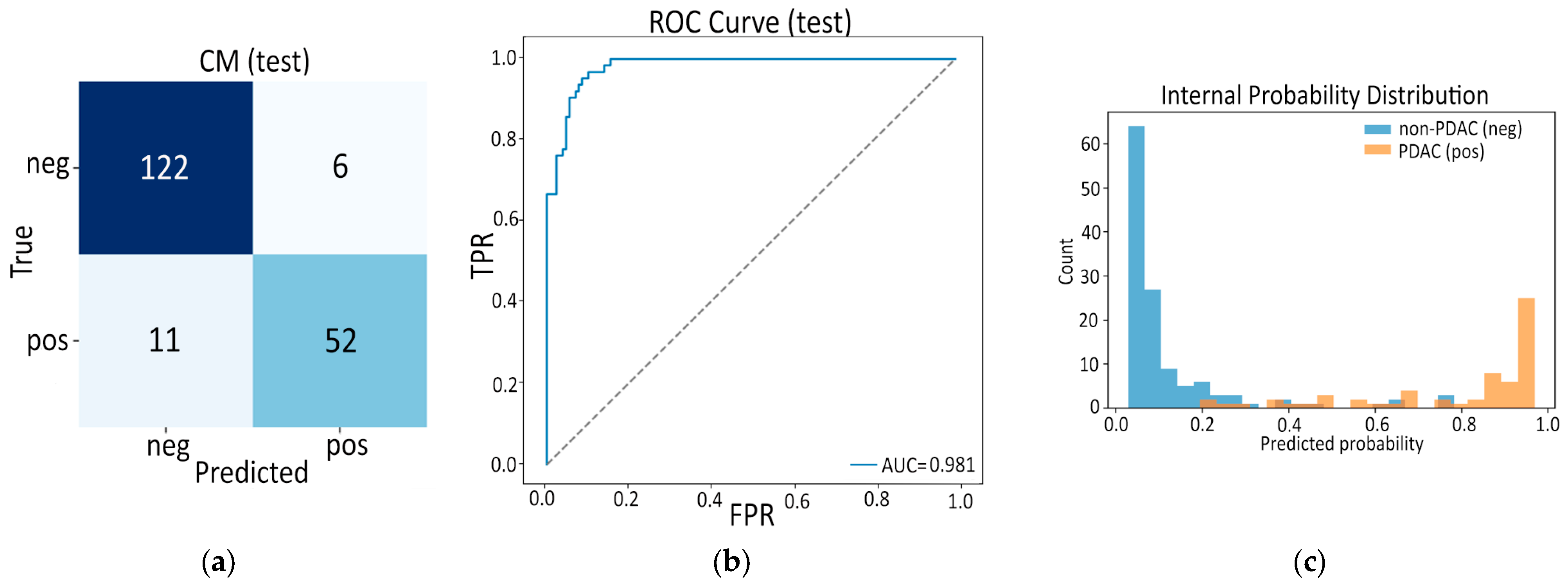

| Metric | Internal Test (n = 191) | External Test (n = 456) |

|---|---|---|

| ROC AUC | 0.981 | 0.969 |

| AP | 0.962 | 0.900 |

| Accuracy | 0.911 | 0.901 |

| Sensitivity | 0.825 | 0.840 |

| Specificity | 0.953 | 0.917 |

| F1-score | 0.860 | 0.778 |

| Test | Metric | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Internal | Samples (n) | 191 |

| Brier score | 0.0581 | |

| External | Samples (n) | 456 |

| Brier score | 0.0716 |

| Metric | Internal Test (n = 191) | External Test (n = 456) |

|---|---|---|

| ROC AUC | 0.999 | 0.987 |

| Average Precision | 0.997 | 0.964 |

| Accuracy | 0.969 | 0.932 |

| Sensitivity | 0.905 | 0.936 |

| Specificity | 1.000 | 0.931 |

| F1 Score | 0.950 | 0.850 |

| Test | Metric | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Internal | Samples (n) | 191 |

| Brier score | 0.0221 | |

| External | Samples (n) | 456 |

| Brier score | 0.0475 |

| No. | Item | Score |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Imaging-protocol transparency | +3 |

| 2 | Repeat-scan robustness | 0 |

| 3 | Inter-scanner assessment | +1 |

| 4 | Multiple segmentations | +2 |

| 5 | Feature reduction and multiplicity control | +3 |

| 6 | Biological correlates | 0 |

| 7 | Pre-specification of cut-offs | +1 |

| 8 | Multivariable clinical factors | 0 |

| 9 | Discrimination statistics (+CIs) | +2 |

| 10 | Calibration statistics | +1 |

| 11 | Internal validation | +1 |

| 12 | External validation | +4 |

| 13 | Prospective design | 0 |

| 14 | Cost-effectiveness analysis | 0 |

| 15 | Open science and data sharing | +2 |

| 16 | Potential clinical utility planning | +1 |

| Subtotal | +21 | |

| Negative penalties | 0 | |

| TOTAL RQS | 36 | |

| Item (Conditional) * | Answer | Key Evidence from Our Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Adheres to guidelines | Yes | CLEAR, ARISE, ESR essentials, TRIPOD-AI principles explicitly cited and followed |

| 2 Representative eligibility criteria | Yes | PANORAMA cohort includes all consecutive contrast-enhanced CTs with and without PDAC; exclusion list reported |

| 3 High-quality reference standard | Yes | Histopathology or ≥2 expert radiologists’ consensus used as ground-truth label |

| 4 Multi-center data | Yes | Five European hospitals (NL × 3, SE × 1, NO × 1) |

| 5 Clinically translatable imaging source | Yes | Routine portal-venous CT only |

| 6 Acquisition protocol reported | Yes | Vendor, kVp, mAs, kernel and slice thickness provided in Methods |

| 7 Imaging–reference interval stated | Yes | Surgery/biopsy within 4 weeks for PDAC; index CT used for non-PDAC |

| Segmentation present? | Yes | |

| Fully automatic segmentation? | Yes (auto masks supplied) | |

| 8 Transparent segmentation description | Yes | Manual vs. nnUNet auto masks, quality scores, bbox routine explained |

| 9 Formal evaluation of auto segmentation | No | Auto masks accepted from PANORAMA without re-scoring |

| 10 Single reader masks on test set | No | Mix of single-reader and auto masks |

| Hand-crafted features extracted? | Yes | |

| 11 Sound image pre-processing | Yes | LPS reorientation, isotropic resample, HU-clipping, Z-score, crop/pad |

| 12 Standardized extraction software | Yes | PyRadiomics 3.0, YAML params shared |

| 13 Extraction parameters reported | Yes | BinWidth, wavelet, LoG sigmas listed |

| Tabular data present? | Yes | (radiomics features) |

| End-to-end deep learning present? | Yes | (Model B and Fusion E2E) |

| 14 Removal of non-robust features | Yes | Variance-filter and low-MI drop |

| 15 Removal of redundant features | Yes | Pearson/Spearman > 0.90 pruning |

| 16 Dimensionality vs. sample size appropriate | Yes | 16 (radiomics) + 23 (deep) features for >1200 patients |

| 17 Robustness tests for DL pipelines | Yes | 3 × 5 fold CV, three random seeds, internal and external test |

| 18 Proper data partitioning | Yes | Vendor-stratified Train/Val/Internal-test/External-test |

| 19 Handling confounders | No | Age/sex not explicitly modeled |

| 20 Task-appropriate metrics | Yes | ROC-AUC, AP, Acc, Sens, Spec, F1 |

| 21 Uncertainty considered | Yes | 1000-sample bootstrap CIs |

| 22 Calibration assessed | Yes | Reliability diagrams, Brier scores |

| 23 Uni-parametric imaging or proof of inferiority | Yes | Radiomics-only vs. Deep-only baselines published |

| 24 Added clinical value over non-radiomic approach | Yes | Fusion surpasses deep CNN and SVM radiomics |

| 25 Comparison with classical stats | Yes | L1-logistic baseline included |

| 26 Internal testing | Yes | Hold-out Siemens/Philips split |

| 27 External testing | Yes | Independent Toshiba vendor |

| 28 Data availability | Yes | PANORAMA dataset is public under license |

| 29 Code availability | Yes | All scripts + YAML on GitHub |

| 30 Model availability | Yes | Trained checkpoints released |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lekkas, G.; Vrochidou, E.; Papakostas, G.A. Deep-Radiomic Fusion for Early Detection of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13024. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413024

Lekkas G, Vrochidou E, Papakostas GA. Deep-Radiomic Fusion for Early Detection of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13024. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413024

Chicago/Turabian StyleLekkas, Georgios, Eleni Vrochidou, and George A. Papakostas. 2025. "Deep-Radiomic Fusion for Early Detection of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13024. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413024

APA StyleLekkas, G., Vrochidou, E., & Papakostas, G. A. (2025). Deep-Radiomic Fusion for Early Detection of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13024. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413024