Abstract

Evaluating the quality of fine-grained 3D shape editing, such as adjusting a vehicle’s roof length or wheelbase, is essential for assessing generative models but remains challenging. Most existing metrics depend on auxiliary regressors or large-scale human evaluations, which may introduce bias, reduce reproducibility, and increase evaluation cost. To address these issues, a reference-free metric for evaluating fine-grained 3D shape editing is proposed. The method is based on the Rich-Attribute Sufficiency Assumption (RASA), which posits that when a geometric attribute set is sufficiently comprehensive, models with the same attribute vector should exhibit nearly identical shapes. Following this assumption, the dataset itself serves as a validation source: each source model is edited to match a small set of target attribute vectors, and the post-editing similarity to the targets reflects the editor’s accuracy and stability. Reproducible indicators are defined, including mean similarity, variation across targets, and calibration with respect to attribute distance. Empirical validation demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed metric, showing approximately 9% degradation under semantic perturbations and less than 2% variation across different target-sampling settings, confirming both its discriminative sensitivity and robustness. This framework provides a low-cost, regressor-free benchmark for fine-grained editing and establishes its applicability through an explicit assumption and evaluation protocol.

1. Introduction

Three-dimensional (3D) shape generation and editing have become central topics in computer vision, computer-aided design, and digital manufacturing [1]. Recent advances in deep generative modeling, including Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [2,3], Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [4], and implicit neural representations such as DeepSDF [5], have enabled the construction of compact latent spaces that capture both geometric and semantic information, thereby supporting controllable 3D synthesis.

Building upon these representations, recent studies on 3D model editing have primarily explored text- or image-guided modifications of existing shapes. Methods such as DreamEditor and FocalDreamer [6,7] achieve localized edits while preserving unedited regions, whereas 3DNS [8] and SKED [9] extend similar ideas to signed-distance and NeRF-based representations. Subsequent approaches, including Tip-Editor [10], NeRF-Insert [11], ViCA-NeRF [12], and LatentEditor [13], introduce multimodal control, multi-view consistency regularization, and latent diffusion-based manipulation. PrEditor3D [14] proposes a training-free pipeline for synchronized multi-view editing, and Chen and Lau [15] investigate reference-based deformation for aesthetic enhancement of 3D shapes. Collectively, these studies highlight the increasing diversity of controllable 3D editing frameworks guided by external modalities such as text, images, and reference shapes.

While such methods achieve semantically meaningful edits, they do not provide quantitative geometric control. Fine-grained 3D editing instead aims to adjust specific geometric attributes, such as vehicle wheelbase, cabin height, or roof curvature, without altering the overall appearance. However, global geometric metrics such as the Chamfer Distance or Earth Mover’s Distance primarily assess overall shape fidelity and do not indicate whether a particular attribute has been correctly modified. For example, extending a vehicle’s wheelbase by 10% while keeping other features unchanged requires precise attribute-level control, which existing distance metrics are unable to verify. This limitation highlights the need for attribute-specific editing methods and, more importantly, reliable evaluation protocols for assessing editing accuracy.

In the image domain, various evaluation methods have been introduced to assess edit quality without relying on fixed ground truths. Zhuang et al. [16] presented a framework for editing 2D images in the latent space of a GAN model and evaluated controllable latent editing using quantitative metrics for disentanglement and identity preservation, complemented by user studies on the controllability of natural scenes. CLIPScore [17] measures text–image alignment through vision–language models, while ReMOVE [18] assesses object removal quality based on perceptual similarity in unedited regions. VIEScore [19] further extends this paradigm to conditional image generation by aligning edits with visual–linguistic instructions.

In the 3D domain, evaluation methods remain comparatively less mature. LADIS [20] introduces the Part-wise Edit Precision (PEP) metric to verify whether edits are localized to the intended parts. However, it requires segmentation annotations and only measures where changes occur, without assessing whether the attributes reach their intended values. ShapeGlot [21] employs a reference game to evaluate shape–language alignment, whereas ShapeTalk [22] defines four complementary metrics: Linguistic Association Boost (LAB), Geometric Difference (GD), Localized Geometric Difference (localized-GD), and Class Distortion (CD), capturing semantic consistency, geometric fidelity, and category realism. Although these approaches provide valuable insights into language-guided editing, they rely on pretrained models and are not directly applicable to purely geometric or attribute-driven tasks.

More recent studies have adopted diverse quantitative strategies. CustomNeRF [23] evaluates multimodal edits using CLIP directional similarity (CLIPdir), DINO feature similarity (DINOsim), and user preference scores. FreeEdit [24] introduces a geometric penetration-percentage metric to assess physical plausibility in object insertion. CNS-Edit [25] combines generative quality scores (FID and KID) with human-rated Quality Scores (QS) and Matching Scores (MS). Perturb-and-Revise [26] measures prompt fidelity and identity preservation using CLIP directional similarity and LPIPS perceptual distance.

Collectively, these studies highlight the ongoing efforts to evaluate 3D editing quality through semantic, perceptual, and geometric consistency. Nevertheless, most existing metrics remain tied to specific modalities or pretrained models, which limits their applicability to fine-grained geometric editing. To address this limitation, the present work introduces an evaluation framework that is conceptually model-independent and regressor-free, providing a way to quantify attribute-level consistency in 3D latent-space editing without relying on a particular generative representation.

In this paper, a distinct evaluation paradigm is proposed based on the Rich-Attribute Sufficiency Assumption (RASA): if a dataset provides a sufficiently rich and comprehensive set of geometric attributes, then two shapes with identical attribute vectors should be nearly identical in geometry. This assumption is plausible in domains with extensive attribute annotations, such as automotive design datasets containing dozens of dimensional specifications, and it holds empirically when the attribute set captures most geometric degrees of freedom.

Under RASA, the dataset itself serves as the validation source. Given a source shape and a target shape with attribute vectors and , an edited shape should satisfy . By the assumption, if , then should be geometrically similar to . Importantly, no external regressor is required for verification; geometric similarity between and can be directly measured using standard shape metrics such as Chamfer distance, surface sampling, or latent-space similarity in learned representations.

This approach offers several notable advantages:

- Regressor-free: The evaluation does not depend on an external attribute predictor, thereby eliminating regressor-induced bias.

- Scalable and interpretable: Once a dataset with rich attribute coverage is available, evaluation only requires geometric similarity computation, and the resulting scores directly reflect the performance of the attribute editor.

Building upon these advantages, the main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- We formalize the Rich-Attribute Sufficiency Assumption (RASA) and specify the conditions under which it enables reference-free and regressor-free evaluation.

- We establish a four-part validation protocol to assess the reliability and discriminative behavior of the proposed metric, covering structural weakening sensitivity, robustness to semantic corruption, attribute-difference difficulty patterns, and stability under different target-sampling densities.

- We empirically validate the framework on a dataset of 3D vehicle models annotated with 33 geometric attributes, demonstrating that the RASA-based metric clearly differentiates editing performance across multiple latent-code editors.

2. Materials and Methods

This section describes the task formulation, dataset, and the RASA-based evaluation protocol used to assess fine-grained 3D shape editing.

2.1. Task Definition and Dataset

This study is built upon the latent-space editing framework developed in our previous work on fine-grained 3D vehicle manipulation [27]. Essential technical background is provided here to keep the paper self-contained.

2.1.1. Latent-Space Editing Framework

Shape Representation. The DeepSDF [5] implicit representation is adopted, in which each 3D vehicle is encoded as a latent code in a continuous latent space . A pretrained decoder network reconstructs the vehicle surface from its latent code via signed distance fields. This latent space exhibits semantic structure, with neighboring codes corresponding to geometrically similar vehicle shapes.

Attribute-Driven Editing. Given a source vehicle with latent code and geometric attributes , the editing task aims to adjust so that the resulting shape exhibits target attributes . This is achieved through a learned editor function that takes the source latent code and desired attribute change as input:

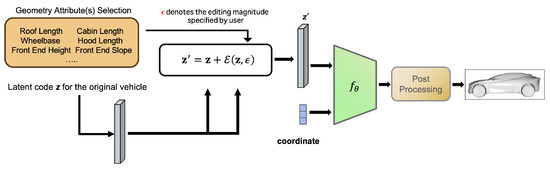

The edited latent code is then decoded via to obtain the modified 3D mesh using marching cubes. For visualization purposes in prior work, the edited latent code was converted into meshes via marching cubes (with DeepSDF of resolution). In the present study, all quantitative evaluation is performed at the latent level for computational efficiency, although the protocol itself is compatible with mesh-level similarity measures conceptually. An overview is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of the latent-space editing framework used for evaluation. A source model’s latent code is modified according to the target attribute change via Equation (1), producing an edited latent code . The edited code is decoded by a pretrained DeepSDF model into a signed distance field, which is then converted into a 3D mesh for evaluation.

Training Supervision. The editor is trained using a pretrained attribute regressor (a lightweight four-layer MLP) that provides training-time supervision. The training objective balances attribute alignment and latent preservation:

where controls the strength of identity preservation. During training, latent codes are sampled from a uniform distribution, and is drawn from and clamped to ensure valid attribute ranges.

This training framework is inherited directly from our previously published work [27], where full architectural details and ablation studies are documented. The implementations are available in our public code repository (https://github.com/JiangDong-miao/Vehicle_LatentEdit, accessed on 30 November 2025). In the present work, these editors are included only as evaluation subjects; the design and training of the editors are not contributions of this paper.

Note on Training Supervision

The regression-based loss in Equation (2) is used only during training and follows our previous work. It does not participate in the evaluation protocol, which is fully regressor-free.

2.1.2. Dataset and Geometric Attributes

The dataset consists of 180 industrial-grade 3D vehicle meshes provided by an automotive partner. Each model is annotated with 33 geometric attributes including roof length, cabin length, wheelbase, front and rear overhangs, and various height and width measurements (Table 1), which were derived and verified by professional designers. All attributes are min-max normalized to [0, 1].

Table 1.

List of 33 geometric specifications of a vehicle.

2.1.3. Evaluation Task Formulation

In contrast to our previous work, which focused on the design and training of latent editors, this paper concentrates on evaluating editing performance under the proposed Rich-Attribute Sufficiency Assumption (RASA).

The proposed evaluation protocol (described in Section 2.2) is applied to several representative latent-code editors implemented using MLP, KAN [28], and Transformer architectures. These editors are treated solely as evaluation subjects rather than as methodological contributions. All follow the same input–output formulation (Equation (1)) to ensure comparability across models. The purpose of these experiments is not to establish performance rankings among editors, but to verify that the proposed evaluation metric provides meaningful and reliable distinctions across different editing behaviors.

2.2. Evaluation Protocol

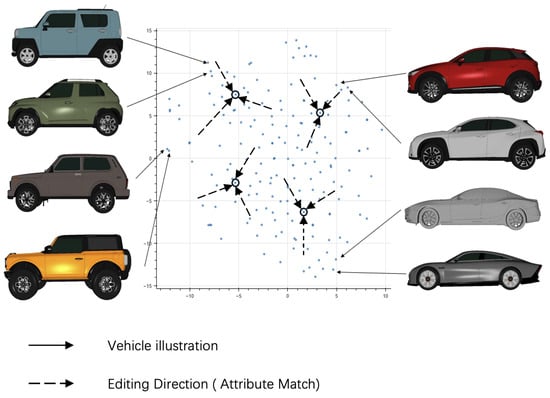

This subsection outlines the complete evaluation procedure used to quantify editing performance under the RASA assumption. This paper introduces an evaluation method based on the Rich-Attribute Sufficiency Assumption (RASA). An overview of the RASA-based evaluation pipeline is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Overview of the proposed RASA-based evaluation pipeline. Blue dots represent 3D vehicle models projected into a 2D embedding space (via t-SNE [29]) for visualization. Circled samples denote targets that are selected uniformly at random from the test set without replacement, following the same sampling rule used throughout the evaluation protocol. Dashed arrows illustrate the editing direction, where each source is modified to match the attributes of its corresponding target via the learned editor . Solid arrows connect highlighted points with their rendered meshes to illustrate representative vehicle shapes (this figure is based on Figure 6 from our previous work [27]).

2.2.1. Protocol Description

This subsection details the step-by-step procedure used to evaluate each source–target editing pair. Given a source model x and a target model r from the test set, the evaluation proceeds as follows:

- The geometric attributes and are obtained from the dataset annotations.

- The attribute difference is computed as .

- The editor is applied using Equation (1) to obtain the edited shape .

- The similarity between and the target r is measured.

This formulation ensures that each editing task is clearly defined by an attribute alignment objective, where the goal is to transform x so that its geometric attributes match those of r.

For each source–target pair , similarity is computed as:

where Sim quantifies geometric similarity between two shapes. It can be implemented at the latent level (e.g., cosine similarity between latent codes) or at the mesh level (e.g., Chamfer distance). This paper adopts latent-level cosine similarity for computational efficiency, while the evaluation protocol itself is conceptually independent of the underlying representation and does not rely on properties specific to DeepSDF. Larger similarity values indicate closer geometric correspondence.

Unless otherwise specified, each source shape is evaluated against target shapes. The K targets are sampled without replacement from the original dataset, and the same fixed target set is used for all editors within each experiment. This global sampling rule ensures strict comparability across architectures in all subsequent analyses.

2.2.2. Aggregation Metrics

To summarize performance across all evaluation pairs, the following aggregated quantities are computed:

where N denotes the total number of source–target pairs. Mean similarity (MS) provides an overall measure of editing quality, while standard deviation (STD) characterizes the consistency of editing behavior across different evaluation scenarios. Together, these indicators provide a concise and reproducible benchmark for fine-grained 3D shape editing.

Note on implementation and assumptions: While the proposed evaluation protocol is designed to be conceptually independent of the underlying representation, the empirical validation in this paper is conducted using DeepSDF latent codes. Figure 2 illustrates a 2D t-SNE projection of these latent codes, in which nearby points generally correspond to vehicles with similar geometric shapes. This visualization highlights that the DeepSDF latent space provides a semantically meaningful structure for the present experiments, enabling similarity-based evaluation in this specific instantiation. The extension of the protocol to alternative representations is left for future work.

3. Results

3.1. Implementation Details

All experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with an A6000-ADA GPU and 128 GB RAM. The software environment included Ubuntu 22.04, Python 3.9, PyTorch 1.9, and CUDA 11.6. All editors share a unified computational framework, and receive the same input ( latent codes and target attribute deltas) as mentioned in Section 2.1.1.

where is the original latent code, denotes the target attribute change, and represents the editing network.

Editor architectures: In our experiments, is instantiated as one of the following:

- MLP: A two-stage multilayer perceptron with ReLU activations.

- KAN: A Kolmogorov–Arnold Network (KAN) [28] employing learnable activation functions.

- Transformer: A lightweight transformer encoder that enables context-dependent editing.

All editors take both and as input, and output the residual to be added to .

3.2. Validation of the Proposed Metric

3.2.1. Conceptual Rationale

The proposed metric is designed to directly measure the geometric fidelity of fine-grained 3D editing without relying on auxiliary regressors or subjective human ratings. Under the Rich-Attribute Sufficiency Assumption (RASA), two models with identical attribute vectors are expected to exhibit nearly identical geometry. By aligning a source model’s attribute vector with that of a target model and then measuring geometric similarity between the edited and target shapes, the metric quantifies how accurately and consistently an editor realizes attribute-specified modifications.

In contrast, existing approaches often assess an editor by how well a regressor predicts the intended attribute values after editing, which inherently introduces the regressor’s bias and noise. The proposed method eliminates this dependency and directly measures the geometric effect of editing.

To quantitatively evaluate the reliability and discriminative capacity of the RASA-based protocol, four validation experiments were conducted using latent cosine similarity as a computational proxy: Discriminative Capacity via Architecture Ablation, Semantic Robustness via Random Perturbation, Difficulty Sensitivity via Attribute-Difference Binning, and Statistical Robustness via K-Target Sensitivity. Unless otherwise specified, all experiments were performed with target pairs.

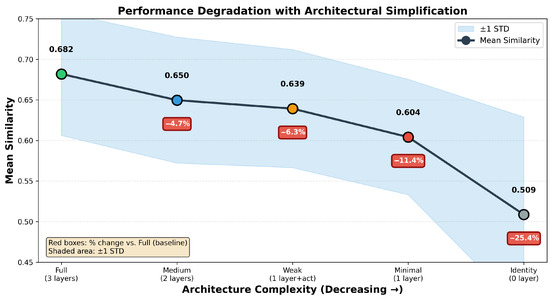

3.2.2. Discriminative Capacity via Architecture Ablation

A fundamental requirement for any evaluation metric is the ability to distinguish high-performing editors from weak ones across a broad performance spectrum. To examine this discriminative capacity, an ablation study is performed by progressively degrading the MLP editor architecture. Beginning with the full 3-layer model, architectural complexity is reduced in a controlled manner by removing layers and non-linearity, culminating in an identity mapping that performs no editing.

Figure 3 shows that the metric correctly reflects monotonic performance degradation: Full (MS = 0.682) → Medium (0.650, −4.7%) → Weak (0.639, −6.3%) → Minimal (0.604, −11.4%) → Identity (0.509, −25.4%). This 25% performance gap between the best and worst architectures confirms the metric’s strong discriminative capacity across the entire performance spectrum. The consistent monotonic decline demonstrates that RASA-based evaluation reliably captures quality differences induced by architectural constraints, validating its effectiveness as a general-purpose assessment tool for shape editing methods.

Figure 3.

Architecture ablation results showing performance degradation with reduced model complexity. The metric correctly reflects monotonic decline from Full (3-layer) to Identity (no editing), with a 25% performance gap confirming strong discriminative capacity. Red boxes indicate cumulative performance change relative to the baseline. Shaded area represents ±1 standard deviation.

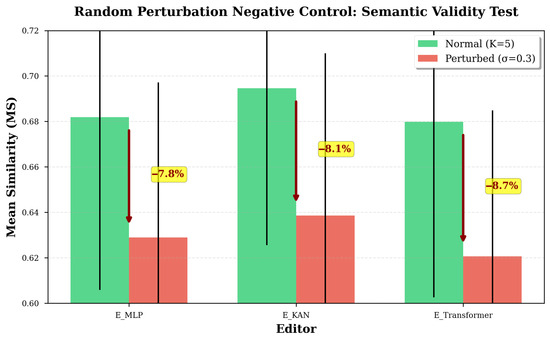

3.2.3. Random Perturbation Negative Control

The random perturbation test examines whether the metric distinguishes semantically coherent edits from those that deviate from intended attribute changes. To create mismatched editing targets, Gaussian noise (, normalized to the attribute scale) is added to the attribute delta vectors , while keeping the overall distance approximately unchanged. If the metric were influenced only by the magnitude of change, similarity values for perturbed edits would remain comparable to those for valid edits with similar distances. If it also reflects semantic coherence in the representation space, similarity should decrease accordingly.

The results confirm the latter behavior consistently across all evaluated editors (Figure 4, Table 2). Relative to normal editing with comparable attribute distances, similarity decreases by approximately 8–9% for the MLP-based editor (), the KAN-based editor (), and the Transformer-based editor (). The consistency of this effect despite architectural differences indicates that the observed behavior reflects the metric’s sensitivity to semantic alignment, rather than model-specific properties.

Figure 4.

Results for the random perturbation negative control test. Comparison between normal attribute-aligned editing (green) and perturbed editing with Gaussian noise () added to while maintaining similar magnitudes (red). All editors show significant similarity degradation (∼8–9%) under perturbation, confirming the metric’s sensitivity to semantic coherence rather than mere change magnitude.

Table 2.

Random perturbation results. All editors show significant degradation under noise.

This test addresses a key confounding possibility: that similarity might only reflect how much the representation changes, ignoring whether the change aligns with the intended semantic direction. The metric reliably assigns lower similarity to perturbed edits under comparable change magnitudes, demonstrating that it identifies whether attribute-driven modifications produce coherent representation transformations. This reinforces the effectiveness of the RASA-based evaluation protocol in assessing the semantic validity of latent or geometric editing behaviors.

3.2.4. Attribute-Difference Binning

Building on the previous analyses, the extent to which the metric reflects differences in the amount of representation change required during editing is examined. To this end, source–target pairs are grouped into three bins based on their L1 attribute differences: Near (smallest 33%), Mid (middle 33%), and Far (largest 33%). Larger attribute differences indicate stronger editing requirements in the representation space. If an editor’s behavior meaningfully depends on edit magnitude, the resulting similarity scores should reflect this relationship; if not, the scores may remain relatively stable across bins. The goal of this experiment is to assess whether the metric can characterize such variation when it exists.

Table 3 shows the results across the evaluated editors. For the Transformer-based editor, similarity decreases steadily as attribute differences increase (0.709 → 0.683 → 0.650), with statistically significant Near–Far differences. The MLP-based editor shows a similar but more moderate trend (0.702 → 0.688 → 0.678). In these cases, the metric clearly reflects a relationship between edit magnitude and representation change.

Table 3.

Attribute-difference binning results across three editors.

The KAN-based editor, in contrast, exhibits only minimal variation across bins (0.702 → 0.701 → 0.694), with differences that are not statistically significant (). This indicates a distinct behavioral regime where the editor produces relatively consistent representation changes regardless of attribute distance. This pattern suggests that changes induced by editing are subtle compared to other factors affecting the representation. Importantly, the metric successfully differentiates such stable behavior from magnitude-sensitive patterns without imposing assumptions about expected trends.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that the proposed metric can characterize multiple valid forms of editing behavior—from architectures whose similarity depends strongly on attribute change to those exhibiting more uniform transformation characteristics. This supports the metric’s role as a general diagnostic tool for analyzing shape editing behavior across different latent or geometric representations.

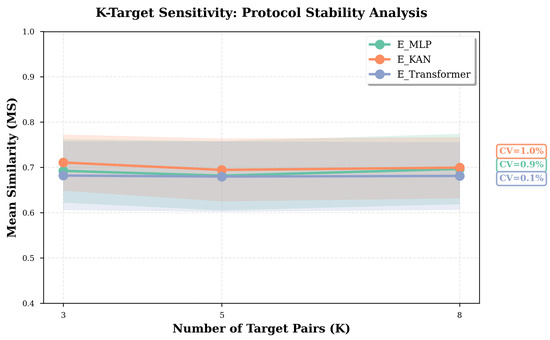

3.2.5. K-Target Sensitivity

To assess the robustness of the evaluation protocol to sampling variation, the number of target shapes associated with each source is varied across . This analysis examines whether the resulting similarity values remain consistent when the sampling density of attribute targets is changed. For each value of K, targets are sampled without replacement from the test set for every source shape, ensuring no overlap between source and target. Importantly, the same set of K targets is used for all editors in each trial to eliminate sampling bias when comparing methods.

As shown in Figure 5, the metric remains highly stable across all editors and K settings. Fluctuations in mean similarity remain below 2%, with coefficients of variation ranging from 0.1% to 1.0%. For example, the Transformer-based editor reports MS values of 0.682, 0.680, and 0.681 for (CV: 0.1%), while the MLP-based editor reports 0.693, 0.682, and 0.697 (CV: 0.9%). Similar consistency is observed for the KAN-based editor. These results indicate that the evaluation outcomes reflect stable editing behavior rather than being tied to specific sampling conditions.

Figure 5.

Results for K-target sensitivity analysis. Mean similarity (MS) remains highly stable across different numbers of evaluation targets per source (), with coefficients of variation for all editors. This demonstrates the evaluation protocol’s robustness to sampling density. For each K, targets are randomly sampled without replacement from the test set for each source shape, and all editors shared the same targets during test.

These findings demonstrate that the proposed evaluation protocol captures intrinsic editor capabilities rather than artifacts of specific shape pairings. The stability across varying K values confirms that the RASA-based metric exhibits strong reproducibility and statistical robustness. Consequently, using as the default configuration provides a well-balanced trade-off between computational efficiency and evaluation reliability, ensuring consistent performance assessment across experiments.

3.2.6. Summary

Across the four validation studies, the proposed metric consistently demonstrates the following properties:

- Discriminative capacity: correctly distinguishes editing quality, from high-quality editors to non-functional baselines;

- Semantic robustness: corrupted edits with comparable magnitude receive significantly lower similarity;

- Difficulty sensitivity: similarity reflects edit magnitude when architectural behavior depends on attribute changes;

- Sampling robustness: evaluation outcomes remain stable under different target selection densities ().

These properties collectively indicate that the RASA-based evaluation protocol provides reliable and reproducible measurements of editing behavior, and functions as a general diagnostic tool for latent- or geometry-based shape editing methods. While the present experiments use DeepSDF as a concrete instantiation, the protocol itself is conceptually applicable to other representations.

4. Discussion

The proposed evaluation framework based on the Rich-Attribute Sufficiency Assumption (RASA) provides a systematic protocol for analyzing representation-editing behavior across multiple editor architectures. Rather than assuming a specific performance trend, the experiments verify whether the metric correctly reflects meaningful variations in editing behavior as they arise.

The architecture ablation experiment validated the metric’s discriminative capacity across a broad performance spectrum: similarity decreases smoothly from high-quality editors (MS = 0.682) to the identity mapping (MS = 0.509), establishing a substantial performance gap. The random perturbation experiment further confirmed semantic sensitivity, with corrupted edits showing a consistent 8–9% reduction in similarity relative to valid edits. Together, these results indicate that the proposed indicators—mean similarity (MS) and stability (STD)—provide coherent and architecture-independent insight into edit fidelity.

Building on this foundation, the attribute-difference binning experiment assessed whether edit magnitude influences representation change. For the MLP- and Transformer-based editors, Near–Mid–Far stratification revealed clear magnitude-sensitive behavior, whereas the KAN-based editor remained largely invariant across bins. This diversity demonstrates that the evaluation protocol does not impose assumptions regarding how similarity should vary, but instead captures architecture-specific editing regimes. The K-target sensitivity experiment further confirmed that evaluation outcomes remain stable across different sampling densities, supporting the statistical robustness of the protocol.

Additional considerations. The evaluation currently relies on cosine similarity in the DeepSDF latent space, which has been shown to correlate well with global geometric structure, though it may be less sensitive to very fine local variations. The identity-mapping baseline (MS ) reflects the typical proximity among distinct vehicle shapes in this latent space and therefore provides a meaningful lower reference point when interpreting editing quality.

Because all editors operate within the same pretrained representation and are evaluated on identical source–target pairs, any irregularity of the latent space would affect them uniformly. The consistent and architecture-specific patterns observed across experiments—such as perturbation degradation, magnitude-sensitive versus magnitude-invariant trends, and smooth ablation curves—therefore reflect differences in editor behavior, rather than artifacts arising from the representation space.

More fine-grained analyses, such as attribute-wise difficulty or cluster-dependent variation, fall outside the scope of validating the proposed metric but remain valuable complementary directions. Extending the protocol to mesh-level similarity measures or alternative 3D representations also represents an important avenue for future work.

Overall, the validation studies confirm that the proposed RASA-based framework provides reliable, interpretable, and architecture-consistent measurements of editing behavior across diverse editing conditions.

5. Conclusions

This work proposes a RASA-based evaluation protocol for fine-grained 3D shape editing that eliminates dependency on auxiliary regressors. The protocol is validated through four complementary experiments: (1) discriminative capacity; (2) semantic robustness; (3) difficulty sensitivity; and (4) sampling robustness.

The experiments demonstrate that the proposed evaluation indicators—mean similarity (MS) and standard deviation (STD)—provide reliable and interpretable measurements across diverse editing conditions and editor architectures. Unlike regressor-based approaches that introduce prediction bias, RASA-based evaluation metric directly measures whether editing achieves the intended geometric transformations by comparing edited shapes with attribute-matched targets from the dataset. This makes our evaluation metric applicable to any shape editing framework with rich attribute annotations, establishing a methodological foundation for regressor-independent evaluation in fine-grained 3D editing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M. and B.R.; methodology, J.M.; software, J.M.; validation, J.M.; formal analysis, J.M.; investigation, J.M.; resources, K.S.; data curation, J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.; writing—review and editing, J.M., B.R., T.N., T.H. (Takenori Hiraoka), Y.G. and T.H. (Toru Higaki); visualization, J.M.; supervision, Bisser Raytchev, Y.G. and T.H. (Toru Higaki); project administration, B.R.; funding acquisition, B.R., T.N. and K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Revised This research was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI, grant number JP23K11170; and by Mazda Motor Corporation (industry collaboration funding, no grant number). The APC was funded by the authors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to corporate confidentiality and licensing restrictions.

Acknowledgments

Revised The authors would like to thank Mazda Motor Corporation for providing access to the 3D vehicle data used in this study and for their technical support during the collaboration. The authors also thank the members of the Visual Information Science Laboratory, at Hiroshima University for their helpful discussions and feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Keigo Shimizu was employed by the company Mazda Motor Corporation. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Elrefaie, M.; Qian, J.; Wu, R.; Chen, Q.; Dai, A.; Ahmed, F. AI Agents in Engineering Design: A Multi-Agent Framework for Aesthetic and Aerodynamic Car Design. In Proceedings of the 51st Design Automation Conference (DAC), Boston, MA, USA, 17–20 August 2025; American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME): New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achlioptas, P.; Diamanti, O.; Mitliagkas, I.; Guibas, L. Learning Representations and Generative Models for 3D Point Clouds. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1707.02392. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, C.; Xue, T.; Freeman, W.T.; Tenenbaum, J.B. Learning a Probabilistic Latent Space of Object Shapes via 3D Generative-Adversarial Modeling. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1610.07584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, S.; Koo, B.; Stoyanov, D.; Clarkson, M.J. 3D Shape Variational Autoencoder Latent Disentanglement via Mini-Batch Feature Swapping for Bodies and Faces. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2111.12448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.J.; Florence, P.; Straub, J.; Newcombe, R.; Lovegrove, S. DeepSDF: Learning Continuous Signed Distance Functions for Shape Representation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, L.; Lin, L.; Li, G. DreamEditor: Text-Driven 3D Scene Editing with Neural Fields. In Proceedings of the SIGGRAPH Asia 2023 Conference Papers, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 12–15 December 2023; Association for Computing Machinery (ACM): New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dou, Y.; Shi, Y.; Lei, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, P.; Ni, B. FocalDreamer: Text-driven 3D Editing via Focal-fusion Assembly. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Eighth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-24), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024; AAAI Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2024; pp. 3279–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzathas, P.; Maragos, P.; Roussos, A. 3D Neural Sculpting (3DNS): Editing Neural Signed Distance Functions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–7 January 2023; pp. 4510–4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikaeili, A.; Perel, O.; Safaee, M.; Cohen-Or, D.; Mahdavi-Amiri, A. SKED: Sketch-guided Text-based 3D Editing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 14561–14573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Kang, D.; Cao, Y.P.; Li, G.; Lin, L.; Shan, Y. TIP-Editor: An Accurate 3D Editor Following Both Text-Prompts And Image-Prompts. ACM Trans. Graph. 2024, 43, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabat, B.O.; Achille, A.; Trager, M.; Soatto, S. NeRF-Insert: 3D Local Editing with Multimodal Control Signals. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.19204. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J.; Wang, Y.X. ViCA-NeRF: View-Consistency-Aware 3D Editing of Neural Radiance Fields. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2023), New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023; pp. 61466–61477. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid, U.; Iqbal, H.; Karim, N.; Hua, J.; Chen, C. LatentEditor: Text Driven Local Editing of 3D Scenes. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision – ECCV 2024: 18th European Conference, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. Part LXIV. pp. 364–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkoç, Z.; Gümeli, C.; Wang, C.; Nießner, M.; Dai, A.; Wonka, P.; Lee, H.Y.; Zhuang, P. PrEditor3D: Fast and Precise 3D Shape Editing. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.06592. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Lau, M. Enhancing the Aesthetics of 3D Shapes via Reference-based Editing. ACM Trans. Graph. 2024, 43, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, P.; Koyejo, O.; Schwing, A.G. Enjoy Your Editing: Controllable GANs for Image Editing via Latent Space Navigation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.01187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessel, J.; Holtzman, A.; Forbes, M.; Bras, R.L.; Choi, Y. CLIPScore: A Reference-free Evaluation Metric for Image Captioning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2104.08718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, A.; Chakrabarty, G.; Bardhan, J.; Hebbalaguppe, R.; AP, P. ReMOVE: A Reference-free Metric for Object Erasure. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.00707. [Google Scholar]

- Ku, M.; Jiang, D.; Wei, C.; Yue, X.; Chen, W. VIEScore: Towards Explainable Metrics for Conditional Image Synthesis Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Bangkok, Thailand, 11–16 August 2024; Ku, L.W., Martins, A., Srikumar, V., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 12268–12290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, I.; Achlioptas, P.; Zhang, T.; Tulyakov, S.; Sung, M.; Guibas, L. LADIS: Language Disentanglement for 3D Shape Editing. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.05011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achlioptas, P.; Fan, J.; Hawkins, R.; Goodman, N.; Guibas, L. ShapeGlot: Learning Language for Shape Differentiation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 8937–8946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achlioptas, P.; Huang, I.; Sung, M.; Tulyakov, S.; Guibas, L. ShapeTalk: A Language Dataset and Framework for 3D Shape Edits and Deformations. In Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 12685–12694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Huang, S.; Nie, X.; Hui, T.; Liu, L.; Dai, J.; Han, J.; Li, G.; Liu, S. Customize your NeRF: Adaptive Source Driven 3D Scene Editing via Local-Global Iterative Training. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.01663. [Google Scholar]

- Madhavaram, V.; Rawat, S.; Devaguptapu, C.; Sharma, C.; Kaul, M. Towards a Training Free Approach for 3D Scene Editing. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.12766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Hui, K.H.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Fu, C.W. CNS-Edit: 3D Shape Editing via Coupled Neural Shape Optimization. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGGRAPH 2024 Conference Papers (SIGGRAPH ’24), Denver, CO, USA, 28 July–1 August 2024; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Karras, J.; Martin-Brualla, R.; Kemelmacher-Shlizerman, I. Perturb-and-Revise: Flexible 3D Editing with Generative Trajectories. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2412.05279. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, J.; Ikeda, T.; Raytchev, B.; Mizoguchi, R.; Hiraoka, T.; Nakashima, T.; Shimizu, K.; Higaki, T.; Kaneda, K. Fine-grained 3D vehicle shape manipulation via latent space editing. Mach. Vision Appl. 2025, 36, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Vaidya, S.; Ruehle, F.; Halverson, J.; Soljačić, M.; Hou, T.Y.; Tegmark, M. KAN: Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2404.19756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Maaten, L.; Hinton, G. Visualizing Data using t-SNE. JMLR 2008, 9, 2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).