Abstract

Background: Elevated heart rate (HR) reactivity to psychomotor challenge mirrors greater proneness to acute stress, which is a disadvantage in competitive sports. This study investigated whether temperament and adiposity predict HR reactivity during a reaction time (RT) task in adolescent athletes, with a focus on identifying their role in psychophysiological vulnerability. Participants and procedure: The participants were 20 adolescent canoe athletes (15 boys, 5 girls; mean age = 14.3 ± 1.88 years). They were volunteers recruited from a canoe club, with the permission of their coaches and parents. The study was conducted in a controlled laboratory setting, where participants underwent anthropometric tests, completed a questionnaire, had a HR monitor fitted, and rested in an armchair until a relatively stable HR (±5 beats per minute) was recorded. Subsequently, their HR was monitored across three 5 min phases: baseline, RT task, and recovery. Reactivity was calculated as the difference between task and recovery, because pre-task HR was influenced by anticipation. Data analyses were performed using AI-assisted and verified Bootstrapped Spearman correlations, Lasso regression with five-fold cross-validation, and stability analysis with 25 repeated cross-validations. Results: Shyness and body fat percentage were positively related to HR reactivity, whereas other temperament traits and RT performance showed no statistically significant associations. The Lasso regression results revealed shyness and adiposity as significant predictors, with their interaction consistently identified as the strongest effect (selected in 76% of models). The independent measures did not affect HR in the recovery phase. Conclusions: Shy adolescents with higher adiposity demonstrate heightened stress responses, as evidenced by HR reactivity, underscoring the importance of addressing stress vulnerability in young athletes and extending this line of inquiry to a broader spectrum of junior athletes.

1. Introduction

Heart rate (HR) reactivity, typically defined as the increase in HR during an acute challenge, serves as a non-invasive yet rough marker of sympathetic nervous system activation and the acute stress response [1]. Although high HR reactivity is often viewed as maladaptive, evidence shows it can also serve adaptive functions. For instance, higher HR reactivity has been associated with better overall intelligence, faster choice reaction times, and less decline in cognitive performance over time [2]. These findings suggest that increased cardiovascular responses may indicate motivated engagement with challenging tasks rather than solely pathological stress reactivity [2]. Nevertheless, individuals with heightened HR reactivity demonstrate a greater sympathetic arousal in response to laboratory stressors, underscoring their value as a physiological biomarker of stress [2].

Although HR reactivity can reflect both adaptive engagement (e.g., facilitated cognitive performance) and maladaptive stress sensitivity, in the present study, we adopt a stress-vulnerability perspective. Specifically, we conceptualize heightened HR reactivity primarily as an indicator of greater physiological sensitivity to acute stress, which may signal psychophysiological vulnerability in adolescent athletes. This framing aligns with our research aims, which focus on whether shyness and adiposity—two factors previously linked to increased stress responsivity—predict amplified cardiovascular responses during a psychomotor challenge. Thus, while HR reactivity can have adaptive correlates, in this study, it is interpreted chiefly as a marker of heightened stress responsivity rather than enhanced cognitive engagement [1].

Athletes frequently encounter psychomotor pressure and must respond swiftly and accurately in competitive situations. These reaction-time (RT) tasks not only require rapid decision-making but also elicit measurable autonomic responses. For example, the RT of college soccer players differs under varying task loads and positional demands, highlighting how athletic effort influences HR reactivity and performance [3]. However, young athletes appear to exhibit relative HR responses during mental stress anticipation and task performance that are similar to those of non-athletes, suggesting that, at a younger age, there may be no distinct stress-regulation profiles for regularly trained youth [4]. Nonetheless, whether the challenge is purely cognitive, like the Stroop color-word task or mental arithmetic used by Ábel et al. [4], or involves psychomotor elements, could affect how young athletes respond to psychomotor challenges.

Furthermore, youngsters’ temperament can influence HR reactivity to stress. Although shyness is often examined in social or evaluative contexts, research shows that shy or behaviorally inhibited youth also exhibit heightened autonomic and attentional reactivity during cognitively demanding or novel non-social tasks, indicating a broader sensitivity to challenging contexts beyond social evaluation [5,6]. For example, Evans et al. [7] found that HR reactivity was related to temperament in adolescents but not in children, with higher sociability linked to lower HR reactivity among adolescents. This finding suggests that certain temperament traits may shape how youth physiologically respond to stress. Converging evidence indicates that shyness is an important factor. Shy children show increased cardiovascular arousal during social stress, both in their own performance and when observing a peer under pressure. For example, shyness was associated with higher HR while children watched an unfamiliar peer prepare for a speech, with reactivity intensified when the peer displayed anxious behavior [8]. Related research also suggests that shyness is linked to altered autonomic arousal patterns during social interactions, including changes in respiratory sinus arrhythmia; however, findings vary across studies (e.g., [9]). Overall, these studies suggest that shyness is associated with heightened physiological sensitivity in stressful situations.

Adiposity may also increase the physiological stress responses. A higher body fat percentage has been associated with increased cortisol response and reduced cognitive resilience during stress [10], as well as exaggerated cardiovascular responses [11]. Importantly, adiposity’s effect on HR reactivity might indicate a broader dysregulation of the sympathoadrenal and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axes in response to stress.

In summary, evidence indicates that shyness and adiposity may increase HR responses to stress. Although athletic training often improves cardiovascular resilience, the potential interaction between temperament and body fat composition in adolescent athletes remains unexplored. Since heightened HR reactivity to acute stress has been associated with poorer cognitive performance and disengagement during challenging tasks [12,13], exaggerated cardiovascular responses could hinder performance and serve as a meaningful target for intervention. Understanding how shyness and adiposity affect HR reactivity could provide a new framework for identifying interaction patterns in performance-linked stress psychophysiology, especially during RT tasks in young athletes.

The present study aimed to investigate how temperament (e.g., shyness) and adiposity influence HR reactivity to stress in adolescent athletes. Specifically, it addresses the research question of whether shyness and adiposity interact to produce heightened cardiovascular responses during psychomotor challenges. This relationship has not yet been explored in this population and thus represents a novel contribution. Based on prior evidence linking shyness and adiposity to heightened physiological stress responses, we hypothesize that higher levels of shyness will be associated with greater HR reactivity among adolescents with greater body fat, reflecting an interaction pattern of exaggerated stress reactivity.

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Education and Psychology at ELTE Eötvös Loránd University (approval no. 2023/299, issued on 9 May 2023; valid until 30 June 2026). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [14] and national regulations governing research involving human participants. The study also conformed to the Code of Human Research Ethics of the British Psychological Society [15]. Before data collection, both adolescents and their parents or legal guardians received detailed written and verbal information about the study. Additionally, written informed consent was obtained from the parents and the adolescents. Both parties agreed to the anonymous use and publication of the recorded data for scientific purposes. All data handling and storage complied with the provisions of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, EU 2016/679; [16]) to ensure confidentiality and data security.

2.2. Participants

Adolescents were recruited from a small-town canoeing sports academy. This setting was chosen because (a) the academy provided access to adolescents within the targeted age group who were familiar with sports and structured physical activity, ensuring they could safely complete the psychomotor stress task; (b) the consistent training background minimized variability caused by differences in physical conditioning, making the cardiovascular reactivity data easier to interpret; and (c) the academy environment facilitated contacting parents and obtaining informed consent, as parents were regularly involved in their children’s training and school activities.

The study sample consisted of 20 school-aged adolescents (15 boys and 5 girls) with an average age of 14.3 years (SD = 1.88, range = 11.1–17.5 years). Their average height was 167.98 cm (SD = 14.67), and average body weight was 59.94 kg (SD = 16.57), resulting in a mean body mass index (BMI) of 20.83 kg/m2 (SD = 2.92). Body composition analysis showed an average percent body fat (PBF) of 15.48% (SD = 6.88). Regarding prior sports experience, participants reported an average of 3.04 years (SD = 2.03). They engaged in sports or structured exercise 9.5 times per week (SD = 2.76), with typical training sessions lasting about 3.45 h per day (SD = 0.89). The final sample size of 20 reflects the total number of eligible athletes enrolled in the club who consented to participate, as no additional members were available or willing during data collection. Recruiting athletes from other clubs or different sports was deemed impractical due to differences in training load, schedules, and accessibility, which would have added unwanted heterogeneity to the data. Likewise, involving non-athletes was not considered appropriate, as their lower fitness levels and slower reaction times compared to athletes (e.g., [17]) would have biased reaction time measurements and physiological reactivity comparisons. Therefore, relying on only 20 elite canoe athletes is a limitation of this study, which naturally affects the emerging results and their generalizability.

Since all participants were competitive canoe athletes, they were required to obtain annual medical clearance to compete, which included screening for cardiovascular, metabolic, and neuropsychiatric conditions. According to team medical records and parent reports, none of the adolescents had chronic illnesses, used medications that could affect autonomic or mood responses, or smoked. To minimize behavioral confounders, participants (and their guardians) were instructed to refrain from vigorous exercise, eating large meals, and consuming caffeine or energy drinks from the early evening on the day before testing. They were also instructed to have their usual breakfast two hours prior to testing. All tests were conducted in the morning hours under standardized research conditions.

2.3. Sample Size Calculation

Sample size planning was based on correlations between temperament and body composition variables and HR reactivity. We used Fisher’s z transformation [18,19] with α = 0.05 (two-tailed) and a desired power of 0.80. Effect sizes like those seen in this study (ρ ≈ 0.55–0.60) indicated that about 20–24 participants were needed, while more minor effects (ρ = 0.40–0.50) would require larger samples of 30–47. With our N = 20, the estimated power was 0.82 for ρ = 0.60 and 0.72 for ρ = 0.55, but only 0.42 for ρ = 0.40. Therefore, the study had enough power to detect moderate to significant correlations, but was underpowered for more minor effects, acknowledging the need for larger samples in future research. Nonetheless, to compensate for the modest sample size, we employed bootstrapping, which enhances the robustness of parameter estimates and confidence intervals by repeatedly resampling the data.

Because formal sample-size formulas are not available for Lasso regression and given the small sample size (N = 20), we treated the Lasso analyses as exploratory. To address potential instability, we complemented the cross-validated Lasso with repeated resampling, which confirmed that the Shyness × Body Fat interaction was the most consistently selected predictor.

2.4. Measures and Instruments

2.4.1. Demographic Measures

We asked the adolescents their age and biological sex. Additionally, they were required to indicate their athletic history (since when they have been training regularly), weekly frequency of training, and an approximate number of hours of training each day (excluding rest days).

2.4.2. Temperament Assessment

We assessed adolescents’ temperament using the Emotionality, Activity, and Sociability (EAS) Temperament Survey for Children [20], a widely used tool for parent and teacher evaluations as well as a self-report designed to measure temperament traits during childhood and adolescence. In this study, we used the self-report version. The EAS includes four subscales: Emotionality, Activity, Sociability, and Shyness, each consisting of 5 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, where higher scores indicate a stronger expression of the trait. Sample items from each subscale include: “I am shy” (Shyness), “I cry easily” (Emotionality), “I like being with others” (Sociability), and “I am always active, doing something” (Activity). The questionnaire has demonstrated good psychometric properties across various populations, with Cronbach’s α coefficients typically ranging from 0.70 to 0.84 [20].

2.4.3. Body Composition

Body fat percentage (PBF) was measured using the InBody 720 bioelectrical impedance analyzer (Biospace Co., Seoul, Republic of Korea). The device estimates body composition by passing a safe, low-level electrical current through the body and analyzing impedance across multiple frequencies. Participants were measured barefoot and in light clothing, following standard manufacturer protocols. The InBody system has been shown to provide reliable and valid estimates of body composition in youth populations when compared with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) [21,22].

2.4.4. Mental Challenge—The Reflex Trainer Application and Heart Rate Measure

Mental challenge was induced using the ‘Reflex Trainer’ app (v. 3.0.4), a mobile reaction-time (RT) application designed for RT training. This application uses adaptive algorithms akin to basic artificial intelligence to adjust task difficulty, providing a standardized yet dynamically responsive psychomotor challenge. This app offers both classic and gamer modes that display visual stimuli in unpredictable patterns, prompting participants to tap or respond as quickly as possible. This task creates cognitive load, a sense of time pressure, and motor urgency, serving as an intense mental challenge. In research settings, reaction-time tasks with rapid visual–motor demands have been used effectively as stressors to induce significant cardiovascular arousal [23], resulting in increased heart rate and decreased HRV. Using this app in our study was justified because it is fast-paced, unpredictable, and closely simulates acute stress scenarios while remaining safe and engaging for physically fit adolescents. For young, trained athletes, such as adolescent canoeists, who often perform under pressure, the Reflex Trainer RT task provides a realistic, challenging, yet non-threatening stressor that elicits cardiovascular reactivity without risk of harm.

Heart rate was continuously recorded using a Polar H10 chest strap monitor (Polar Electro Oy, Kempele, Finland), which provides validated beat-to-beat R–R interval data with millisecond precision. Signals were transmitted via Bluetooth to the Polar monitoring application and exported for offline analysis. Because the pre-task baseline period showed clear anticipatory arousal and therefore did not represent a true resting baseline, we used HR(Task)–HR(Recovery) as an exploratory index of reactivity. Although this differs from standard HR(Task)–HR(Baseline) scoring, using recovery as the comparator minimized distortion from anticipatory activation. We acknowledge that this is a non-standard approach and interpret the resulting HR-reactivity measure cautiously, noting it requires replication with a true resting baseline and additional adjustment methods used in psychophysiology.

2.5. Procedure

All tests were conducted in a temperature- and humidity-controlled laboratory to minimize the impact of environmental factors on the measurements. Data collection took place on the weekly rest day (Saturday) mornings to reduce variability caused by training and school activities and to ensure participants were well-rested. The experiment spanned from June 2023 to the end of June 2024. The young athletes were tested individually in a quiet environment to prevent distractions and potential peer influence.

Upon arrival, the young athletes were informed about the test protocol and confirmed their understanding. They then signed a written informed consent form. Subsequently, they completed the EAS Temperament Survey and underwent anthropometric assessments, including height, weight, and body composition measurements using the InBody analyzer. After these assessments, participants were fitted with the HR monitor and seated comfortably. A stabilization period was needed to establish a baseline, during which HR had to remain stable (within ±5 beats per minute) before starting the protocol. Once stabilization was achieved, the session included a 5 min resting baseline, a 5 min Reflex Trainer reaction-time task (an acute mental challenge), and a 5 min post-task recovery period. HR was recorded continuously throughout all phases, and average values were calculated for baseline, task, and recovery for subsequent statistical analyses.

Mental Challenge Task

The stress task consisted of a 5 min session in the classic square nine-dots mode of the Reflex Trainer application. The button speed was set to 500 ms and button active time to 2000 ms, with a slow start and progressively increasing difficulty (speed). In this mode, participants were required to respond as quickly and accurately as possible to stimuli appearing at unpredictable intervals and locations. Errors did not terminate the task; instead, missed or incorrect responses triggered an immediate restart of the trial, and the session continued until the full 5 min were completed. The software automatically recorded both the number of trials completed and the total points scored within a five-minute period. This standardized setup ensured continuous engagement, consistent task pressure, and a progressively challenging cognitive–motor load, while also providing objective performance metrics.

2.6. Data Analyses

Anticipation effects were examined using a paired t-test. Additionally, we conducted bootstrapped Spearman correlation analyses to investigate the relationship between HR reactivity and the dependent measures, employing bootstrapped correlations (1000 samples, BCa CIs) and applying Bonferroni correction. Predictor analyses were performed with Lasso regression (five-fold cross-validation), including main effects and two-way interactions, followed by a stability check through repeated cross-validation. To improve analytic robustness, AI-assisted modeling was employed. “AI-assisted” does not refer to the statistical algorithm itself—which is standard cross-validated Lasso—but to the use of AI tools to automate resampling loops, generate reproducible analysis scripts, and verify parameter settings during repeated cross-validation. Specifically, the Lasso regression and stability analyses were implemented using an AI-guided cross-validation approach that optimized parameter tuning and model interpretability. The integration of AI-supported analysis facilitated the detection of subtle interactive patterns, such as the Shyness × Body Fat effect.

All analyses were conducted in R (version 4.x). Bootstrapped Spearman correlations were computed using the boot package (1000 BCa resamples). Lasso regression was performed with the glmnet package, with all predictors z-standardized prior to modeling and interaction terms calculated from standardized variables. Repeated five-fold cross-validation and model-tuning procedures were implemented using the caret package. In this context, the term ‘AI-assisted’ refers to the automated hyperparameter optimization and resampling routines of these machine-learning libraries, which were used to enhance model stability and interpretability.

3. Results

3.1. Anticipation Effects

To test whether the pre-task baseline HR was affected by anticipatory arousal, we compared the mean HR before and after the task. Pre-task HR was on average 3.09 bpm higher than post-task HR (SD = 5.12; t(19) = 2.71, p = 0.014; Hedges’ g bias-corrected effect size = ≈ 0.59), suggesting that the baseline was elevated due to anticipation. Spearman correlations with 1000-sample bias-corrected bootstrapping indicated that, after Bonferroni correction, anticipatory HR was not significantly linked to any measures of temperament, body composition, or task performance. Therefore, changes in anticipatory HR seemed independent of individual psychological or physical traits in this sample.

3.2. Correlations Between Dependent Measures and Heart Rate Reactivity

Bootstrapped Spearman rho correlations indicated that both shyness and the percentage of body fat were positively associated with HR reactivity during mental challenge (Table 1), and these associations remained statistically significant after Bonferroni correction (new ρ = 0.00714). All bootstrap bias values were minimal (close to zero), which indicates that the bootstrap estimates were stable and not meaningfully biased relative to the sample estimates. None of the other traits (emotionality, activity, sociability) or performance measures (RT trials and points) showed a significant relationship with HR reactivity. To explore the combined and potential interactive effects of the significant predictors, we then employed a Lasso regression.

Table 1.

Bootstrapped Spearman Correlations.

3.3. Heart Rate Recovery After the Psychomotor Challenge

We also examined whether individual differences predicted HR during the recovery phase. Neither shyness (ρ = 0.10, p = 0.67, 95% BCa CI [−0.42, 0.58], bias = −0.01) nor body fat percentage (ρ = −0.07, p = 0.76, 95% BCa CI [−0.51, 0.36], bias = 0.00) was significantly related to the absolute HR during recovery.

3.4. Predictor Analysis with Lasso Regression

To identify the key predictor of HR reactivity, we used Lasso regression with five-fold cross-validation. Lasso is a penalized regression method that reduces the impact of less relevant predictors toward zero, helping to prevent overfitting and enhance model interpretability, particularly in small samples with correlated predictors. Given the limited sample size, interaction terms were included only for exploratory variable selection rather than confirmatory hypothesis testing. In the initial model, which included only main effects (shyness, body fat, emotionality, activity, sociability), Lasso kept shyness (β = 1.48) and body fat (β = 1.56) as non-zero predictors. At the same time, all other temperament dimensions were set to zero. This confirms that shyness and adiposity are the main factors influencing increased HR reactivity to psychomotor challenge in adolescent athletes. AI-assisted cross-validation ensured the stability of the predictive model, and in an exploratory interaction model, confirmed the consistency of the shyness × body fat interaction across repeated trials; however, this interaction should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating rather than statistically confirmatory.

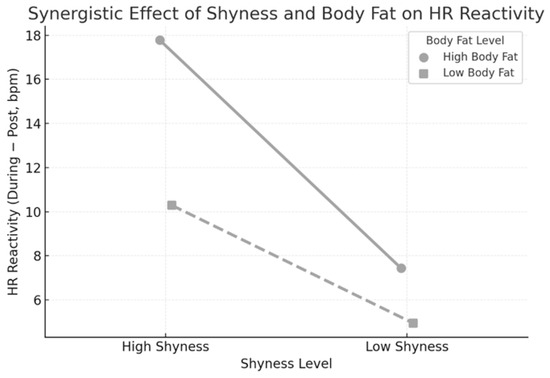

When all two-way interaction terms were added, the model yielded a more straightforward solution: only the shyness × body fat interaction was retained (β = 1.11). These results show a combined effect: reactivity increased sharply with shyness only among adolescents with higher body fat percentage. In contrast, reactivity remained low and stable across shyness levels in leaner peers. Figure 1 illustrates this interaction: HR reactivity was most significant in the High Shyness + High Body Fat group, indicating an interaction pattern for increased cardiovascular stress responses.

Figure 1.

Interaction between shyness and body fat in predicting heart rate (HR) reactivity in beats per minute (bpm). The HR reactivity was calculated as the difference between the mean HR during the reaction-time task and the mean HR in the recovery phase. Adolescents with both great shyness and high body fat showed the greatest HR reactivity, reflecting a shyness × body fat interaction in cardiovascular responding during the task.

To test the stability of the findings, we conducted an AI-assisted stability check via repeated cross-validation across 25 trials. The shyness × body fat interaction appeared in 76% of the models, whereas shyness and body fat as main effects were selected far less often (28% and 8%, respectively). Other temperament predictors and their interactions were rarely included. This stability analysis suggests that the interaction between shyness and adiposity, rather than either trait alone, is the most reliable predictor of exaggerated cardiovascular reactivity in this sample.

4. Discussion

The current findings contribute to an emerging understanding of how individual differences among youngsters, particularly shyness and adiposity, may relate to HR reactivity during psychomotor challenges in adolescent athletes. Consistent with our hypothesis, both shyness and higher body fat percentage were positively linked to greater HR reactivity during the RT task. Notably, their interaction (High Shyness × High Body Fat) resulted in the highest HR reactivity. This reactivity reflects performance anxiety associated with the RT task, as, unlike the findings of Ginty et al. [2], HR reactivity was unrelated to the number of trials completed or the points obtained, that is, to better task performance. These results expand previous research, which has primarily examined temperament or adiposity separately, and suggest that they may interact to predict greater cardiovascular reactivity.

Heightened HR reactivity could also be a possible indicator of a maladaptive stress response, particularly in relation to future risk of cardiovascular disease (Trotman et al., 2018 [24]) or poorer recovery [25]. In our sample of adolescent athletes, who likely have better baseline cardiovascular fitness, the fact that shyness and adiposity still predict higher HR reactivity could indicate that even among “resilient” populations, psychological and metabolic traits influence stress physiology. This is practically significant: during competition or high-pressure training, exaggerated HR responses could increase wear and tear on the cardiovascular system, impact concentration, or cause fatigue, particularly with repeated or chronic stressful exposures.

The current findings may also be related to cognitive load, as increasing cognitive load leads to higher HR responses, while task performance tends to decline or become less efficient [26]. Although Alshanskaia et al.’s [26] sample was not adolescent athletes, the principle that greater reactivity accompanies greater cognitive demand supports the idea that athletes who are shy and carry more body fat may experience greater psychophysiological strain during psychomotor challenges, potentially at the expense of optimal performance (which was not the case in the current work). Despite no connection between HR reactivity and task performance (see Table 1), our findings may reflect a stress adaptation response rather thanblunted HR reactivity linked to disengagement, deficient performance, or health risks [5,13].

In contrast to our results, Park et al. [27] showed that in a large community sample of adolescents (14–16 years), higher BMI and greater negative affect independently predicted blunted HR reactivity to laboratory stressors (mental arithmetic and speech), with no parallel changes in galvanic skin conductance reactivity. This suggests a cardiac/noradrenergic-specific dampening rather than a global sympathetic effect. Resting HR was negatively associated with reactivity, whereas BMI was unrelated to resting HR. In relation to young canoe athletes in the current study, who exhibited heightened HR reactivity associated with shyness and body fat, especially during interactions, these findings offer a contrasting benchmark for non-athlete youth under psychosocial stressors. The divergence likely reflects key moderators in the two research designs: (i) athlete status/fitness, (ii) stressor type (psychomotor RT task vs. cognitive math/speech), (iii) reactivity measurement (task–recovery vs. task–rest), and (iv) affect construct (shyness vs. broad internalizing).

Like Park et al. [27], several researchers use pre-task HR measures as a baseline for calculating HR reactivity [4,28,29]. However, as shown in the current study, pre-task HR is influenced by anticipation effects, with a notable medium effect size. Therefore, calculating HR reactivity from post-task or recovery HR is more accurate, especially considering the meta-analytic findings suggesting that athletes recover quickly from mental stress [30,31].

The importance of recognizing HR as a response to upcoming challenge during the pre-task anticipation phase is demonstrated by Ábel et al. [4]. This study compared athlete and non-athlete children (11–15 years old) on HR responses to music-distracted psychosocial stressors (Stroop, mental arithmetic), analyzing both absolute HR and relative HR reactivity. Athletes showed lower absolute HR during anticipation and stress compared to non-athletes. However, no differences appeared when responses were expressed relative to a baseline recorded before the anticipation period, emphasizing the importance of considering baseline values. The participants in Ábel et al.’s study also showed no difference in perceived stress, arousal, feelings, or task performance. While their results suggest that athletic status may not influence psychosocial stress reactivity, differences could exist in psychomotor tasks like RT, as shown by our results, because athletic training is closely linked with RT practice. These findings also highlight the potential of combining psychological profiling with AI-based physiological monitoring tools to predict stress vulnerability in young athletes, allowing for individualized coaching and prevention strategies.

Considering HR recovery after a challenge, the results indicated that shyness and adiposity predicted reactivity but not HR recovery. This finding aligns with other studies (e.g., [4,32], which found no difference in HR between athlete and non-athlete children during stress recovery. It remains unclear whether this interaction pattern would relate to recovery dynamics during more extended or repeated real-life challenges.

4.1. Limitations

Limitations of this study include the small sample size, which reduces the statistical power to detect smaller effect sizes, and limited generalizability beyond canoeing or similar sports. The sample size (N = 20) and recruitment from a single canoe club also preclude confirmatory inference about interaction effects; accordingly, the Shyness × Body Fat interaction identified through LASSO should be viewed as a hypothesis-generating result that requires replication in larger, more diverse samples. Moreover, the duration of the psychomotor challenge may be considered brief; more ecologically valid tasks (e.g., game-like fatigue, repeated stress, combined cognitive-motor load plus social evaluation) might reveal larger or different interaction effects. Furthermore, because the pre-task baseline showed clear anticipatory activation and we lacked additional resting baseline measures, our use of HR(Task)–HR(Recovery) as the reactivity index should be considered exploratory and tentative. Therefore, the work requires replication using standard psychophysiological baseline-adjustment procedures. Future research should also strive to replicate these findings with larger, more diverse athlete samples, including non-athlete controls, and to explore long-term outcomes (e.g., whether heightened HR reactivity predicts declines in performance or increased injury risk).

4.2. Practical Implications

Given the likelihood of shyness and adiposity together increasing stress reactivity, targeted interventions can be implemented. For example, psychological approaches (e.g., social skills training, anxiety reduction) and physical or metabolic health improvements (body composition, conditioning) can work together to reduce cardiovascular stress during periods of pressure. Coaches and sports psychologists can monitor HR reactivity during training or competition to identify athletes at risk of overarousal and to develop training programs that gradually expose athletes to psychomotor stress while enhancing their regulatory skills. Finally, the integration of AI-supported data analysis in this study underscores the growing role of machine intelligence in psychophysiological research. Automated model selection and stability testing enhanced objectivity and reproducibility, which are particularly important in small-sample psychophysiological studies. Future research could expand on these applications by incorporating AI-driven pattern recognition of multimodal signals such as HRV and electrodermal activity.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that adolescent canoe athletes with higher levels of shyness and body fat show increased HR reactivity during an acute RT challenge. These traits interact: HR reactivity significantly increases with shyness only among youths with greater adiposity, indicating an exploratory interaction pattern. The findings were statistically robust and confirmed through bootstrapped correlations, penalized (Lasso) modeling, and stability checks, with the Shyness × Body-fat interaction remaining consistent across most re-samples. In contrast, other temperament traits and task performance measures (trials, points) showed no association with HR reactivity. Significantly, neither shyness nor adiposity predicted post-stress or recovery HR, indicating that these factors are explicitly linked to reactivity during the challenge rather than to the post-challenge return toward baseline.

Methodologically, two aspects strengthen the interpretation. First, we documented a moderate anticipatory increase in HR before the task, highlighting that pre-task baseline levels can be influenced by arousal; calculating reactivity relative to post-task recovery thus provides a more reliable HR reactivity estimate in athlete samples known for quick recovery. Second, using a standardized, fast-paced RT stressor offered an ecologically relevant proxy for competition-like demands in trained youth, without confounds from physical exertion.

Taken together, the findings support the idea that psychological (shyness), and physiological/metabolic (adiposity) factors interact to influence cardiovascular stress responses, at least within this specific athletic sample. At this stage, these results should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating, and any applied implications remain speculative until replicated in larger samples and linked to behavioral or performance outcomes.

The small, single-sport sample and the brief laboratory test limit the conclusions that can be drawn from these results. Future research should verify the interaction pattern in larger, multi-sport groups, assess whether it predicts real-world outcomes (such as errors under pressure, injury risk, and training tolerance), and expand physiological measures beyond HR (e.g., HRV and electrodermal activity) to better understand the underlying mechanisms. However, the current findings provide preliminary evidence that temperament and adiposity are not only related but also jointly influence cardiovascular reactivity in young athletes, offering a valuable framework for future research but not yet for applied practice.

Author Contributions

A.R.-S. contributed to data collection, statistical analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. V.V. was responsible for the literature review, methodology design, and editing. P.B. assisted with participant recruitment, data handling, and manuscript preparation. B.F. contributed to data interpretation, critical revisions, and formatting. A.S. provided conceptualization, supervision, and final approval of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Research Ethics Board of the Faculty of Education and Psychology at ELTE Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest has approved this study (Certificate no. 2023/299, issued on 9 May 20213).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available at the Mendeley data repository (DOI: 10.17632/bhmycr9v75.1).

Acknowledgments

OpenAI’s ChatGPT 5 was used for grammar and writing cohesiveness checks, statistical workflow, and verification.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chida, Y.; Steptoe, A. Greater Cardiovascular Responses to Laboratory Mental Stress Are Associated With Poor Subsequent Cardiovascular Risk Status. Hypertension 2010, 55, 1026–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginty, A.T.; Phillips, A.C.; Der, G.; Deary, I.J.; Carroll, D. Heart rate reactivity is associated with future cognitive ability and cognitive change in a large community sample. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2011, 82, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentz, L.E.; Palmer, E.; Davis, A.S.; Minton, T.A. Reactive task performance under varying loads in collegiate soccer athletes. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 707910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ábel, K.; Szabó, A.R.; Szabó, A. Heart rate reactivity to mental stress in athlete and non-athlete children. Balt. J. Sport Health Sci. 2020, 3, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, N.A.; Henderson, H.A.; Rubin, K.H.; Calkins, S.D.; Schmidt, L.A. Continuity and discontinuity of behavioral inhibition and exuberance: Psychophysiological and behavioral influences across the first four years of life. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, H.A. Electrophysiological correlates of cognitive control and the regulation of shyness in children. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2010, 35, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, B.E.; Greaves-Lord, K.; Euser, A.S.; Tulen, J.H.M.; Franken, I.H.A.; Huizink, A.C. Determinants of Physiological and Perceived Physiological Stress Reactivity in Children and Adolescents. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, K.L.; Sosa-Hernandez, L.; Green, E.S.; Wilson, M.; Labahn, C.; Henderson, H.A. Children’s shyness and physiological arousal to a peer’s social stress. Dev. Psychobiol. 2023, 65, e22388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole, K.L.; Schmidt, L.A. Vigilant or avoidant? Children’s temperamental shyness, patterns of gaze, and physiology during social threat. Dev. Sci. 2021, 24, e13118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mujica-Parodi, L.R.; Renelique, R.; Taylor, M.K. Higher body fat percentage is associated with increased cortisol reactivity and impaired cognitive resilience in response to acute emotional stress. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formolo, N.P.S.; Filipini, R.E.; Macedo, E.F.O.; Corrêa, C.R.; Nunes, E.A.; Lima, L.R.A.; Speretta, G.F. Heart rate reactivity to acute mental stress is associated with adiposity, carotid distensibility, sleep efficiency, and autonomic modulation in young men. Physiol. Behav. 2022, 254, 113908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behnke, M.; Hase, A.; Kaczmarek, L.D.; Freeman, P. Blunted cardiovascular reactivity may serve as an index of psychological task disengagement in motivated performance situations. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnúsdóttir, B.B.; Savage, R.; Frodi, M.; Gylfason, H.F.; Jóhannsdóttir, K.R. Blunted Cardiovascular Reactivity Predicts Worse Cognitive Performance. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Psychological Society. Code of Human Research Ethics; The British Psychological Society: Leicester, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-85433-792-4. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons about the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC General Data Protection Regulation). Off. J. Eur. Union 2016, L119, 1–88. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Wang, C.-H.; Chang, C.-C.; Liang, Y.-M.; Shih, C.-M.; Muggleton, N.G.; Juan, C.-H. Temporal preparation in athletes: A comparison of tennis players and swimmers with sedentary controls. J. Mot. Behav. 2013, 45, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hulley, S.B.; Cummings, S.R.; Browner, W.S.; Grady, D.G.; Newman, T.B. Designing Clinical Research, 4th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Buss, A.H.; Plomin, R. Temperament: Early Developing Personality Traits; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, C.H.Y.; de Craen, A.J.M.; Slagboom, P.E.; Gunn, D.A.; Stokkel, M.P.M.; Westendorp, R.G.J.; Maier, A.B. Accuracy of direct segmental multi-frequency bioimpedance analysis in the assessment of total body and segmental body composition in middle-aged adult population. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 30, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLester, C.N.; Nickerson, B.S.; Kliszczewicz, B.M.; McLester, J.R. Reliability and Agreement of Various InBody Body Composition Analyzers as Compared to Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry in Healthy Men and Women. J. Clin. Densitom. 2020, 23, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Jung, T.-P. A virtual reality game as a tool to assess physiological correlations of stress. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.14421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotman, G.P.; Elstad, M.; Furberg, R.; Njølstad, I. Increased stressor-evoked cardiovascular reactivity is associated with cardiovascular risk. Psychosom. Med. 2018, 80, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiweck, C.; Gholamrezaei, A.; Maxim, H.; Vaessen, T.; Vrieze, E.; Claes, S. Exhausted heart rate responses to repeated psychological stress in women with major depressive disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 869608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshanskaia, E.I.; Zhozhikashvili, N.A.; Polikanova, I.S.; Martynova, O.V. Heart rate response to cognitive load as a marker of depression and increased anxiety. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1355846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, A.E.; Huynh, P.; Schell, A.M.; Baker, L.A. Relationship between obesity, negative affect and basal heart rate in predicting heart rate reactivity to psychological stress among adolescents. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2015, 97, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriev, D.A.; Saperova, E.V.; Indeykina, O.S.; Dimitriev, A.D. Heart rate variability in mental stress: The data reveal regression to the mean. Data Brief 2019, 22, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupper, N.; Denollet, J.; Widdershoven, J.; Kop, W.J. Cardiovascular reactivity to mental stress and mortality in patients with heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2015, 3, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcier, K.; Stroud, L.R.; Papandonatos, G.D.; Hitsman, B.; Reiches, M.; Krishnamoorthy, J.; Niaura, R. Links between physical fitness and cardiovascular reactivity and recovery to psychological stressors: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2006, 25, 723–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, E.M.; Dishman, R.K. Cardiorespiratory fitness and laboratory stress: A meta-regression analysis. Psychophysiology 2006, 43, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurak, N.; Sauer, H.; Weimer, K.; Dammann, D.; Zipfel, S.; Horing, B.; Muth, E.R.; Teufel, M.; Enck, P.; Mack, I. Effect of a weight reduction program on baseline and stress-induced heart rate variability in children with obesity. Obesity 2015, 24, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).