Featured Application

This study shows that an AI-based system for pollen grain classification in honey can serve as a high-throughput decision-support tool in routine melissopalynological analysis. By automating pollen identification from microscopic images, the system reduces effective analysis time per sample and improves reproducibility, which is particularly relevant for official control laboratories, certification bodies and honey producers. Integration via APIs with LIMS and traceability tools enables direct use of classification results in digital documentation of honey authenticity and food fraud vulnerability assessments. The prediction confidence threshold of 0.90 was determined empirically, based on a joint review of model predictions and associated confidence scores by palynology experts. This threshold balances automation efficiency and classification accuracy by enabling automatic acceptance of high-confidence predictions and flagging low-confidence cases for expert review.

Abstract

Honey authenticity, including its botanical origin, is traditionally assessed by melissopalynology, a labour-intensive and expert-dependent method. This study reports the final validation of a deep learning model for pollen grain classification in honey, developed within the NUTRITECH.I-004A/22 project, by comparing its performance with that of an independent palynology expert. A dataset of 5194 pollen images was acquired from five unifloral honeys, rapeseed (Brassica napus), sunflower (Helianthus annuus), buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum), phacelia (Phacelia tanacetifolia) and linden (Tilia cordata), under a standardized microscopy protocol and manually annotated using an extended set of morphological descriptors (shape, size, apertures, exine ornamentation and wall thickness). The evaluation involved training and assessing a deep learning model based solely on the ResNet152 architecture with pretrained ImageNet weights. This model was enhanced by adding additional layers: a global average pooling layer, a dense hidden layer with ReLU activation, and a final softmax output layer for multi-class classification. Model performance was assessed using multiclass metrics and agreement with the expert, including Cohen’s kappa. The AI classifier achieved almost perfect agreement with the expert (κ ≈ 0.94), with the highest accuracy for pollen grains exhibiting spiny ornamentation and clearly thin or thick walls, and lower performance for reticulate exine and intermediate wall thickness. Misclassifications were associated with suboptimal image quality and intermediate confidence scores. Compared with traditional melissopalynological assessment (approx. 1–2 h of microscopic analysis per sample), the AI system reduced the effective classification time to less than 2 min per prepared sample under routine laboratory conditions, demonstrating a clear gain in analytical throughput. The results demonstrate that, under routine laboratory conditions, AI-based digital palynology can reliably support expert assessment, provided that imaging is standardized and prediction confidence is incorporated into decision rules for ambiguous cases.

1. Introduction

Honey authenticity, including its botanical and geographical origin, is a key determinant of food quality, food safety and consumer trust [1,2,3,4,5]. Over recent decades, the apiculture sector has been facing increasing challenges related to honey adulteration, including the blending of honeys from different sources, quality degradation and misdeclaration of origin [6,7,8,9]. Numerous reports and databases documenting fraudulent practices in the food chain identify honey as a product particularly vulnerable to economically motivated adulteration [10,11,12,13,14]. In an economy often characterised as BANI (brittle, anxious, non-linear and incomprehensible), issues of authenticity and supply chain transparency have become an important component of both perceived quality and consumer purchasing decisions [15].

Melissopalynology, recognised as the reference method for determining the botanical origin of honey, provides strong evidential value, but its routine use is limited by several practical constraints: it is time-consuming, requires advanced specialist training and depends on access to high-quality microscopy infrastructure [16,17,18,19]. Consequently, there is a growing demand for higher-throughput tools that would enable rapid and reliable assessments of the origin of bee products in large-scale quality control systems, both in official controls and in commercial applications [15,20,21,22,23]. Although advances in spectroscopy, rapid chromatographic techniques and DNA-based methods have substantially broadened the toolbox for honey authentication [8,21,24], they only partially address the need for automatic, high-throughput pollen analysis of honey samples.

In recent years, there has been growing interest in the use of artificial intelligence (AI), deep learning and computer vision for pollen analysis and honey authentication [25,26,27]. Mahmood et al. [28] developed an attention-guided deep convolutional model for microscopic pollen grain classification, achieving very high accuracy on benchmark datasets. Le et al. [29] evaluated advanced deep learning models (YOLOv11, Vision Transformer and MobileNetV3) for pollen grain classification and proposed a hybrid fusion strategy combining YOLOv11 and Vision Transformer to identify the botanical origin of honey, while Valiente González et al. [30] evaluated a representative panel of standard CNN architectures and lightweight custom networks (PolleNetV2 and PolleNetV2.mobile) for automated pollen identification in honeys. In parallel, specialised systems for pollen classification have been developed, such as PollenNet [31] and AIpollen [32], along with review papers summarising pattern-recognition methods for pollen image analysis [33,34].

These applications are aligned with the broader paradigms of “Food Quality 4.0” and Industry 4.0, in which image data become an integral part of the digital food value chain and AI systems support the management of product quality and authenticity [35,36,37,38,39,40]. Contemporary concepts of intelligent quality assurance systems emphasise the need to integrate deep learning, big data analytics and traceability solutions, including near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), radio frequency identification (RFID), blockchain and the Internet of Things (IoT), into a coherent architecture supporting decision-making along the supply chain [41,42,43]. One of the key challenges in this context is the integration of digital pollen analysis of honey into such systems in line with the requirements of ISO 22000 [44] and ISO/IEC 17025 [45].

The effectiveness of AI models in biological image analysis, however, depends on a range of operational factors and requires robust validation, not only under laboratory conditions but also in the context of real production and control processes, accounting for variation in materials, image preparation procedures and operational conditions [36,37,46]. The literature points to the risk of distribution shift when training images are acquired under ideal conditions (e.g., reference pollen samples), whereas test data comprise pollen imaged within the honey matrix, with variable quality and contaminants [1,29,31,47]. Most existing studies on automatic pollen classification rely on images of isolated grains or reference slides, while applications in honey analysis require models to be robust to matrix artefacts, variability in slide quality and the constraints of routine laboratory work.

An aspect that remains insufficiently explored is validation based on a direct comparison between AI-generated classifications and the assessment of an expert palynologist, particularly when an extended set of pollen grain morphological features is considered, including shape, size, number and type of apertures, surface ornamentation and wall thickness. Existing melissopalynological studies have focused mainly on the classification of varietal (monofloral) honeys and on the problem of over-representation of certain pollen types [16,48,49], and only rarely formalise morphological traits as input variables for AI models. As highlighted by Tkacz et al. [1], even small differences in imaging parameters, such as depth of field, may substantially affect feature extraction and classification performance. Similar conclusions arise from research on automatic plant species identification in natural environments, where image quality and the visibility of diagnostic traits largely determine the performance of deep learning systems [50,51].

Despite the dynamic development of AI-based tools for pollen identification and honey authentication, there is still a lack of publications providing comprehensive comparative validation between AI models and palynological experts, based on pollen grain morphology and images prepared under conditions close to those of routine production and laboratory practice. Available studies often report very high classification performance on carefully curated datasets [28,29,31,32,52], but they rarely include a formal assessment of agreement with expert judgement in the context of routine laboratory workflows and the requirements of food quality and food safety management systems. This gap is particularly relevant for the implementation of AI-based solutions within Vulnerability Assessment and Critical Control Points (VACCP) systems and food fraud prevention plans [15,53,54,55].

The present study constitutes the final stage of the NUTRITECH.I-004A/22 research and development project, co-funded by the National Centre for Research and Development under the NUTRITECH programme. In earlier phases of the project, a process-oriented architecture for a digital honey authentication system was developed, covering the acquisition and processing of pollen images, integration with food safety management systems and embedding of the solution in a broader framework for honey quality management in a BANI world [15,56]. This article focuses on the experimental validation of a key component of that system, an AI model that classifies pollen grains in varietal (monofloral) honeys, in direct comparison with the assessment of an expert palynologist.

In line with the above, the main aim of this study was the experimental validation of the effectiveness of an artificial intelligence (AI) model in classifying pollen grains originating from five unifloral (monofloral) honey varieties, in comparison with the assessment of a palynology expert. The validation was based on a full set of morphological features and on images acquired under a standardised microscopy protocol reflecting routine practice in an accredited honey-testing laboratory.

To achieve this main aim, four specific objectives were formulated:

- To perform a comparative assessment of pollen grain classification in unifloral honeys by the AI model and by the palynology expert, using a set of morphological features including shape, size, type and number of apertures, surface ornamentation and pollen wall thickness.

- To evaluate the accuracy of the AI multi-class classification model in relation to expert classification under conditions of standard sample preparation for honey analysis.

- To identify which morphological features have a significant impact on the agreement between the AI model and the expert, and to determine the influence of image quality (e.g., depth of field) on classification outcomes.

- To formulate recommendations for implementing the AI model in honey quality control and food fraud prevention systems (Vulnerability Assessment and Critical Control Points, VACCP, and vulnerability assessment plans), as well as to indicate limitations that require further improvement.

To structure the validation procedures and enhance the transparency of the study, the following research hypotheses were also proposed:

H1:

The classification performance of the AI model for pollen grains shows statistically significant agreement with the classification provided by the palynology expert.

H2:

Variation in morphological features affects the classification performance of the AI model to different extents.

H3:

Image quality has a significant impact on the agreement between AI-based classification and expert assessment.

H4:

The AI model can be effectively implemented in honey quality and authenticity control systems, provided that the image acquisition procedure is standardised and predefined minimum criteria for image quality and classification confidence are met.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Characteristics of the Research Material

The research material was obtained from the validation stage of an innovative digital honey pollen analysis system developed as part of a project funded by the National Centre for Research and Development (NCBR, Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland), entitled “Development and implementation of a globally innovative digital pollen analysis service for honey using automation and artificial intelligence technologies for application in the functional food production sector” (NCBR, Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland, project no. NUTRITECH.I-004A/22).

A total of 5194 pollen grains were collected from five varieties of monofloral honeys: Brassica napus (n = 1967), Helianthus annuus (n = 603), Fagopyrum esculentum (n = 193), Phacelia tanacetifolia (n = 1458), and Tilia cordata (n = 973). The honeys were produced in 2025 by a commercial honey producer cooperating with multiple apiaries across Poland, and each sample represented a commercial monofloral batch (blend within a production season) typical for the Central European retail market and regarded as representative of monofloral honeys produced under Central European conditions. Monoflorality was confirmed by routine melissopalynological analysis at the Honey Laboratories in Toruń, Poland, in accordance with PN-88/A-77626 and the standard criteria for monofloral honeys (dominant pollen type exceeding the thresholds recommended for the respective botanical origin).

Microscopic preparations of pollen grains were made in accordance with the methodology described by Banach et al. [15] and the PN-88/A-77626 standard [17]. In addition to qualitative identification, a quantitative melissopalynological assessment of each honey sample was performed in accordance with PN-88/A-77626. For every sample, at least 300 pollen grains were counted in randomly selected microscopic fields, and the percentage share of each pollen type in the total pollen spectrum was calculated. In all honeys included in this study, the pollen of the plant species declared as botanically dominant exceeded the minimum percentage required for monofloral honeys in PN-88/A-77626, thereby confirming their monofloral status. These quantitative results were used solely to confirm the monofloral status of the honeys and to select samples for AI validation and were not analysed further in this study, which focused on single-grain classification performance. The procedure included: centrifuging the honey, rinsing the sediment three times with distilled water, drying at room temperature, and embedding the sediment in a mounting medium (glycerin/gelatin/phenol; 1:1:1) on microscope slides.

Microscopic images were taken using a Delta Optical ProteOne (Delta Optical, Mińsk Mazowiecki, Poland) optical microscope equipped with a Delta Optical DLT-Cam Pro 12 MP digital camera. Observations were conducted in transmitted light mode, at 400× magnification, using LED illumination and a fixed white balance. Camera settings and depth of field parameters were kept constant for all samples to limit the influence of imaging variables on the extraction of morphological features.

Each sample was photographed and saved in JPEG format with a resolution of 2592 × 1944 pixels, in 24-bit color mode (RGB). Individual pollen images were then extracted and saved individually in JPEG format. The process of segmenting pollen grain images from source images follows the pipeline described by Banach et al. [15], in which individual grains are detected on the microscopic field and cropped into separate image patches for further analysis. The images were not filtered or brightness/contrast corrected prior to analysis. To ensure standardization of visual data, the image background was kept neutral by using a white reference card.

High-quality microscopic images were recognized as a key condition for effective classification. Particular attention was paid to depth of field, which, according to microscope manufacturers’ recommendations, depends on the focal length of the lens, the aperture value (F), the focusing distance, and the distance between the object and the background. Optimal settings were determined that allowed the entire structure of pollen grains to be captured in a single focal plane, eliminating the risk of losing details crucial for classification.

All pollen grains were assigned to reference classes by an independent palynology expert with over ten years of experience in honey pollen analysis. This expert, employed at the Honey Laboratory, also conducts comprehensive assessments of honey authenticity in laboratory practice, from pollen analysis to detection of chemical residues. The expert’s pollen identification was based on comparing morphological structure details with reference material, using a proprietary image labeling tool.

The labeling process was conducted manually, without knowledge of the AI model’s classification results, ensuring the independence of the reference assessment in the context of model validation. Additionally, a dedicated tool for labeling pollen images was developed, accessible via a web browser, which allowed experts to view the AI classification along with the probability value, as well as select and assign their own expert label. An example of this tool’s interface is shown in Figure 1. Although this tool did not influence the reference labeling process in the present study, its application enables further development of a hybrid environment that combines expert knowledge with AI automation.

Figure 1.

Interface of the labeling tool, example of an image classified by AI with the option for an expert to assign a label.

2.2. Artificial Intelligence Model and Training Pipeline

Within the NUTRITECH.I-004A/22 project, a general deep learning model for pollen grain classification was developed, based on the ResNet152 architecture and using transfer learning from the ImageNet database. For the purposes of the project, the model was fine-tuned to recognise 26 pollen classes on the basis of a total of 62,896 microscopic images, with a global average pooling layer, a fully connected layer with ReLU activation, and a final softmax layer for multi-class classification. A detailed list of all pollen classes and their sample sizes used to train the 26-class model is provided in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1). A dataset of 62,896 pollen images was randomly split in an 80/20 ratio into training and internal validation subsets: approximately 50,317 images were used for training the 26-class model, while approximately 12,579 images were designated exclusively for validation during the training process. Independently of this dataset, an external validation set was prepared for comparison with expert assessment. It consists of 5194 images of pollen grains from monofloral honeys covering five selected pollen types. This set was built completely independently from the data used for training and was not used at any point during model learning or tuning. This three-stage approach (training, internal validation, external validation) allows for a reliable assessment of the model’s ability to generalize and helps reduce the risk of overfitting and potential data leakage.

In the present study, we validated the performance of this model under conditions of routine melissopalynological analysis, focusing on five pollen types corresponding to the monofloral honeys described in Section 2.1.

Before training, all images were converted to grayscale and contrast was enhanced using the CLAHE (Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization) algorithm. To increase the representation of classes with fewer samples, data augmentation was performed (rotations, contrast changes, brightness and sharpness adjustments, mirror reflections).

The dataset was divided into two subsets: a training subset (80%) and a validation subset (20%). To increase the model’s generalization, a series of augmentation transformations were applied, including rotation by ±30°, scaling between 90–110%, vertical and horizontal mirroring, brightness and contrast adjustments within ±15%, and Gaussian noise (σ = 0.01). These procedures aimed to counteract the distribution shift phenomenon, i.e., the mismatch between training and testing data distributions, as discussed by Le et al. [29].

Model weight optimization was performed using the Adam optimizer, with an initial learning rate of 0.0001 and a plateau-based LR reduction schedule (factor 0.5, patience 5). The model was trained for 50 epochs with a batch size of 64. To prevent overfitting, an early stopping mechanism was implemented, triggered if the validation loss showed no improvement over 7 consecutive epochs.

To perform model training, the TensorFlow 2.14 and Keras 3.3.3 environment was utilized on a PC platform equipped with 32 GB RAM and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 Ti GPU (CUDA 12.4, GPU driver: 550.144.03), running under the Ubuntu 22.04 LTS operating system. The entire process was built in Python 3.10.12, leveraging Pillow for data augmentation and OpenCV (version 4.9.0.80) for filtering and CLAHE implementation. TensorFlow 2.14 and Keras 3.3.3 were employed to create and train the models, providing advanced APIs for building and optimizing deep neural networks. The base ResNet152 model (pre-trained on ImageNet) was fine-tuned on the training data after initially freezing the deeper layers, followed by partial unfreezing during the fine-tuning process.

A classification confidence threshold of 90% was set; samples with a predicted probability below this threshold are treated as “unrecognised”. This approach serves to reduce the number of false positives and improve the reliability of classification in the model. The classification confidence method is commonly used in machine learning systems, where it is important to balance prediction confidence with the risk of misclassification.

In previous stages of the NUTRITECH project, the 26-class model was evaluated on the full dataset of 62,896 images, using an 80/20 split into training and internal validation subsets. This evaluation showed high effectiveness, with an overall accuracy of 98.4%, sensitivity of 99.0% and an F1-score of 98.3%, confirming the robustness of the approach in the multi-class pollen classification task.

2.3. Expert Classification and Labeling

The process of labeling pollen grain images was carried out by an independent expert palynologist with over ten years of professional experience in melissopalynology and microscopic analysis of honey samples, conducted in accordance with, among others, the PN-88/A-77626 standard [17]. The expert, acting independently of the team responsible for the AI model, did not have access to the results of the automatic classification, which ensured objectivity and a blind reference assessment [15].

Each microscopic image of pollen grains was evaluated for the following key morphological characteristics: shape, size, type and number of apertures, surface ornamentation (exine), and pollen wall thickness. Based on these characteristics, the expert assigned labels to the images corresponding to the five classified plant species (Brassica napus, Helianthus annuus, Fagopyrum esculentum, Phacelia tanacetifolia, Tilia cordata), in accordance with the identification keys described in the specialist literature [57,58] and the practice of national honey laboratories. Table 1 presents a summary of the morphological characteristics and their operational definitions used in the expert classification process. This labeling approach aligns with advanced validation methods described in the literature on the application of artificial intelligence techniques in biological imaging [59,60,61].

Table 1.

Characteristics of morphological features of pollen grains evaluated by the palynology expert.

2.4. Validation Procedure and Evaluation Metrics

To validate the classification effectiveness, the artificial intelligence (AI) model’s results were compared against the reference classification performed by the palynology expert. The analysis included both overall classification performance and detailed comparisons for each of the five pollen classes. Table 2 presents the applied validation metrics and their significance.

Table 2.

Applied metrics for evaluating AI classifier effectiveness and their interpretation.

A standard set of multiclass classifier evaluation metrics was used, including accuracy (overall correctness); precision for each class; recall (sensitivity); F1-score (the harmonic mean of precision and recall); and the confusion matrix, which visualizes misclassifications between classes. Additionally, measures of agreement between AI and expert assessments were employed: the Kappa coefficient (κ), which measures true agreement adjusted for chance, and percent agreement.

According to current validation standards in AI systems for the food sector, authors such as Cofre et al. [62] and Zhang et al. [6] emphasize the necessity of benchmarking classification algorithms against expert assessments and using test data representative of real-world application conditions. The works of Mahmood et al. [28] and Le et al. [29] indicate that the effectiveness of classifiers depends significantly on the quality of training data labels and the resilience of models to distribution shift.

In order to identify sources of inconsistency, an analysis of the impact of pollen grain morphological features (Table 1) on classification accuracy was performed. For each feature type, the frequency of classification errors was assessed, which allowed the identification of features that significantly reduced the effectiveness of the model (e.g., reticulate ornamentation of the exine and atypical aperture forms).

At the same time, the impact of image quality on classification results was evaluated by comparing subsets of photographs with varying depth of field, contrast, and background noise levels. The outcomes of this analysis allowed for the identification of minimum image quality parameters essential for successful AI segmentation and classification.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using tools available in the Python 3.10 environment (libraries: pandas 2.2.2, scikit-learn 1.5), employing descriptive statistics, confidence interval estimation, and exploratory methods. The objective was to quantitatively determine the classification accuracy of the AI model and assess factors potentially influencing prediction correctness.

Input data for statistical analysis were defined at the level of individual pollen grain images. Metadata for each observation included: the class label assigned by the AI model, the probability value of this class assignment within the range [0,1] (AI probability), the expert palynologist’s reference label (ground truth class), and morphological features of exine ornamentation (echinate, reticulate) and exine border thickness (light, medium, bold).

The analysis took into account variables related to classification accuracy, namely the confusion-matrix components TP, TN, FP and FN, where TP (true positive) means that the model correctly identifies a positive case, TN (true negative) means that the model correctly identifies a negative case, FP (false positive) means that the model incorrectly identifies a negative case as positive, and FN (false negative) means that the model incorrectly identifies a positive case as negative, as well as prediction confidence (confidence score, identified with AI probability), characteristics of pollen grain morphological features, image quality, understood here as technical imaging parameters (contrast, sharpness, depth of field).

Standard metrics for multi-class classification tasks were used to evaluate the effectiveness of the AI classifier: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. The metrics were calculated both globally (for the entire set) and per class (macro average), which made it possible to take into account the uneven distribution of class frequencies. Standard deviation was also used to measure the dispersion of probability values relative to their mean, thus allowing for the assessment of prediction stability and confidence.

Classification agreement between the AI model and the expert was assessed using a confusion matrix, where diagonal elements represented correct classifications and off-diagonal elements indicated errors. Additionally, Cohen’s kappa coefficient was calculated as a measure independent of the frequency of individual classes, and its statistical uncertainty was quantified by estimating the standard error and the corresponding 95% confidence interval. Comparisons between morphological groups (e.g., exine ornamentation, wall thickness, aperture type) were based on effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals rather than formal null-hypothesis significance tests, which we consider more informative in this validation context.

Additional evaluation of model stability was conducted through analysis of the distribution of probability values assigned by the model (confidence histograms) and analysis of result variability in subgroups differing in image quality.

In this study, raw softmax probabilities were used as prediction confidence scores. The operational threshold of 0.90 was selected empirically, based on the relationship between prediction probability and error rate jointly reviewed with the palynology expert; no additional post hoc probability scaling (such as temperature scaling or Platt scaling) was applied.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics and Morphological Features

As described in Section 2.1, a total of 5194 pollen grains originating from five unifloral honey varieties (Brassica napus, Helianthus annuus, Fagopyrum esculentum, Phacelia tanacetifolia and Tilia cordata) were analysed. These grains exhibited a diversified set of morphological features, which formed the basis both for the expert classification and for the operation of the AI model. Five major diagnostic features were considered: shape, size, type and number of apertures, exine surface ornamentation and pollen wall thickness. The feature classes reflect species-specific characteristics described in classical palynological keys and were used by the palynology expert during the labelling process.

The distribution of individual feature categories in the entire sample is presented in Table 3. In most cases, the grains were spherical or sphero-ellipsoidal (96.3%), with a diameter in the range of 20–40 µm (88.4%) and tricolpate apertures (60.3%). Approximately 40% of the grains displayed a spiny exine ornamentation (echinate), whereas 60.3% showed a reticulate pattern (reticulate). Pollen wall thickness was most often classified as medium (41.5%) or thick (30.4%); for 10 grains (0.2% of the sample) this parameter could not be assigned unambiguously. In the subsequent analyses, this feature was represented by three ordinal categories (light, medium, bold), corresponding respectively to thin, intermediate and thick pollen walls.

Table 3.

Distribution of morphological features of pollen grains in the analysed sample (n = 5194), as characterized by the palynology expert based on microscopic images and reference descriptions of the five plant species.

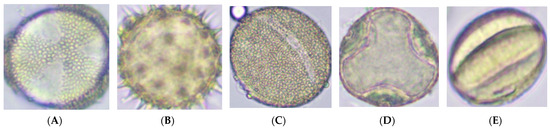

Representative images of pollen grains from the five analysed plant species are shown in Figure 2. The images illustrate the variation in shape, exine surface ornamentation, aperture type and pollen wall thickness, which form the basis both for the expert classification and for the operation of the AI model in subsequent analyses.

Figure 2.

Representative images of pollen grains from the five analysed plant species: (A) Brassica napus—spherical grain, reticulate exine, medium wall thickness; (B) Helianthus annuus—spherical grain with pronounced echinate ornamentation; (C) Fagopyrum esculentum—triangular grain in polar view, reticulate exine; (D) Tilia cordata—spherical tricolpate grain, echinate exine, thick wall; (E) Phacelia tanacetifolia—sphero-ellipsoidal, triporate grain with thin wall.

The above sample characteristics provided the starting point for further analyses comparing the classification performance of the AI model with that of the palynology expert (Section 3.2) and assessing the impact of morphological features and image quality on classification agreement (Section 3.3).

3.2. Classification Performance of the AI Model Relative to the Expert

3.2.1. Overall Performance

In the analysed dataset (n = 5194; see Section 3.1), the labels assigned by the AI model were compared with the classification provided by the palynology expert. In 4977 cases, the model and the expert assigned identical labels, which corresponds to 95.8% concordant classifications in the entire sample. The mean values of the key classification performance metrics, calculated on a per-class basis, were as follows: accuracy 0.96, precision 0.97, recall 0.99 and F1-score 0.98. This high level of performance, given that five plant species were distinguished, indicates very good agreement between AI decisions and the expert’s assessment and confirms hypothesis H1 regarding substantial classification concordance (Table 4). The overall Cohen’s kappa coefficient for agreement between the AI model and the expert was 0.9436, with a standard error of 0.0037 and a 95% confidence interval of 0.9362–0.9509, which corresponds to “almost perfect” agreement according to commonly used interpretation scales.

Table 4.

Agreement between AI model classification and palynological expert assessment.

The results are consistent with the earlier stage of system validation, in which an accuracy of 98.4% and an F1-score of 98.3% were obtained for a broader test set. This confirms the stability of the adopted network architecture across subsequent phases of the NUTRITECH project and the high repeatability of the model’s performance under different data configurations.

3.2.2. Class-Wise Classification Performance

Table 5 summarises the validation results separately for the five pollen types present in the analysed monofloral honeys. For each class, the table reports the sample size, the number and percentage of cases in which the AI label was identical to the expert’s label, as well as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score and the standard deviation (SD) of the prediction probabilities.

Table 5.

Classification performance of the AI model for individual pollen grain classes.

All classes were characterised by very high recall (0.97–1.00), indicating that the model almost never “missed” true instances of a given plant species as identified by the expert. The highest classification accuracy was obtained for Helianthus annuus pollen (accuracy 0.99; F1-score 0.99), followed by Phacelia tanacetifolia (accuracy 0.97; F1-score 0.99). Slightly lower, though still very high, accuracy values were observed for Brassica napus (0.94) and Fagopyrum esculentum (0.95), Table 5. In these classes, a higher proportion of false-positive assignments (FP) was recorded, suggesting that the model tended to over-assign morphologically similar pollen grains from other plant species to these classes.

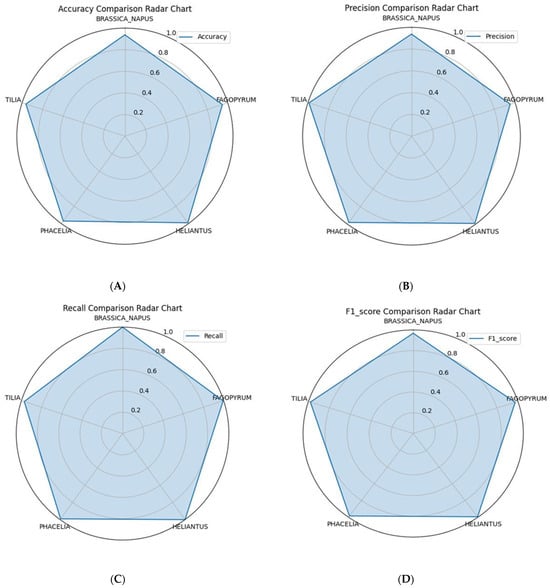

From the perspective of practical applications in honey quality control, it is particularly important that precision and F1-score exceeded 0.95 for all five species. This meets typical deployment criteria for systems designed to support expert decision-making in biological image analysis. The resulting accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score values for all five classes are shown in Figure 3A–D, where each metric is presented separately for all plant species.

Figure 3.

Comparison of AI model performance relative to the palynological expert for five pollen grain classes: (A) accuracy, (B) precision, (C) recall, and (D) F1-score.

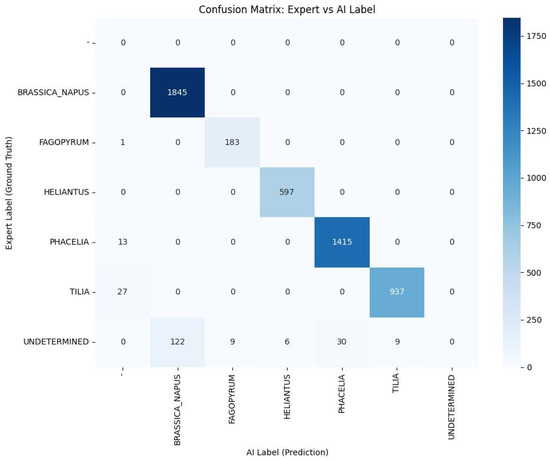

3.2.3. Structure of Classification Errors and Prediction Confidence

Analysis of the confusion matrix showed that the vast majority of observations were correctly classified, whereas the relatively few errors mainly concerned morphologically challenging cases or those labelled by the expert as “undetermined”. In such situations, the model most frequently assigned labels corresponding to plant species with similar morphological features, which is consistent with palynological intuition. The confusion matrix, presented as a heatmap, is shown in Figure 4 (diagonal elements represent correct classifications, while off-diagonal cells indicate the main directions of misclassification).

Figure 4.

Confusion matrix of the AI classifier relative to the expert for five pollen classes. Cell values represent the number of observations, while colour intensity (see colour scale, 0–100%) corresponds to the proportion of samples in each cell.

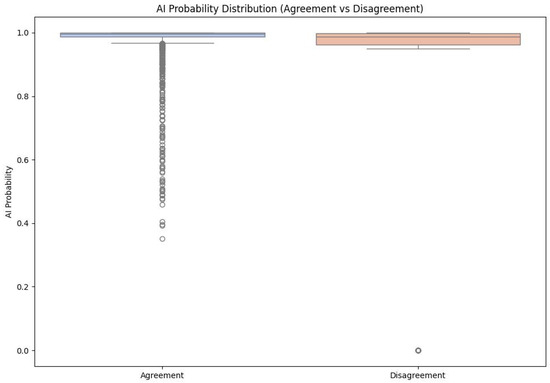

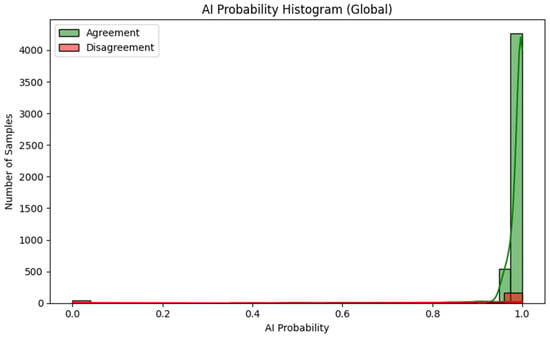

The distribution of prediction probabilities assigned by the model (prediction probability) is shown in Figure 5. A clear difference between the two groups is visible: for classifications concordant with the expert, most values are concentrated close to 1.0, whereas for misclassified cases the distribution of prediction probability is markedly broader with a lower median and a higher proportion of intermediate values. This suggests that the model to a considerable extent reflects the “difficulty” of a given case in its declared confidence level.

Figure 5.

Distribution of prediction probability (AI probability) for correct and incorrect AI classifications relative to the expert labels.

Such behaviour of the model is of practical importance: it makes it possible to define confidence thresholds above which classification results may be accepted automatically (e.g., in high-throughput honey analysis workflows), while cases with reduced confidence can be directed to additional expert verification or re-imaging.

In summary, the results presented in this subsection show that the developed AI model exhibits very high agreement with the palynological expert across all analysed pollen classes. This confirms hypothesis H1, which assumed substantial concordance between AI classification and expert assessment and provides the basis for the subsequent analysis of how morphological features and image quality affect classification performance presented in Section 3.3.

3.3. Analysis of the Impact of Morphological Features and Image Quality

In this part of the study, we analysed to what extent the agreement between the AI model and the palynological expert depends on the morphological characteristics of pollen grains and on the quality of microscopic images. Particular attention was paid to two features that were well-structured in the metadata, exine ornamentation (exine ornament) and pollen wall thickness, and to the distribution of prediction probability values (AI probability), treated as an indirect indicator of image quality and classification difficulty.

3.3.1. Morphological Features and Classification Agreement

Table 6 presents the classification results as a function of exine ornamentation type. The analysis covered two categories: echinate (spiny surface, typical for Helianthus and Phacelia) and reticulate (reticulate ornamentation, characteristic of Brassica, Fagopyrum and Tilia). Pollen grains with spiny ornamentation (echinate) were somewhat easier to classify correctly, AI–expert agreement exceeded 97%, with very high mean prediction probability. For reticulate ornamentation (reticulate), performance remained high (94.6%) but was lower by approximately 3 percentage points. It may be assumed that the more complex and fine-grained exine pattern in the reticulate category increases the risk of confusing plant species with similar surface textures, especially at borderline values of depth of field and contrast.

Table 6.

Agreement between AI model and expert as a function of exine ornamentation.

Table 7 shows the results for pollen wall thickness, assessed in three categories: light, medium and bold. The highest agreement was obtained for grains with thick walls (bold) and thin walls (light), above 97% correct classifications. Pollen grains with medium wall thickness proved clearly more difficult: agreement dropped to 93.8%, despite the fact that the mean prediction probability was among the highest (0.986). This may indicate a certain “overconfidence” of the model in morphologically intermediate cases, where class boundaries are less sharp and structural features resemble those of more than one plant species.

Table 7.

Agreement between AI model and expert as a function of pollen wall thickness.

The model achieved very high classification accuracy for all three aperture types: the highest proportion of correct classifications was recorded for tricolporate pollen (99%), followed by triporate (~97%) and tricolpate (~95%). The mean prediction probability was very high (>0.97) for tricolporate and tricolpate, and around 0.98 for triporate, indicating a high level of confidence in the model’s decisions. The largest number of training samples came from the tricolpate class (3133 images), which may have influenced the model’s performance for this aperture type (Table 8).

Table 8.

Agreement between AI model and expert as a function of aperture type.

The results presented in Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 indicate that the highest agreement between AI model and expert was obtained for pollen grains with clearly defined diagnostic features, in particular spiny exine ornamentation (echinate) and extreme (thin or thick) wall thickness. For each subgroup, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 also report the standard error and 95% confidence interval for AI–expert agreement (accuracy), which quantify the uncertainty around these estimates. Lower performance was observed mainly for grains with reticulate ornamentation and medium exine thickness, which is consistent with the expert’s observations pointing to greater difficulty in distinguishing plant species with similar reticulate patterns and comparable wall thickness. These findings underline that morphologically “intermediate” cases require greater interpretative caution and are more prone to discrepancies between automatic and expert classification.

3.3.2. Image Quality—Model Confidence and Classification Errors

The second area of analysis was the relationship between microscopic image quality, the level of model confidence (prediction probability—AI probability) and the frequency of classification errors. Figure 6 shows the overall distribution of prediction probability values separately for decisions in agreement and disagreement with the palynological expert (n = 5194). This distribution indicates that the vast majority of model predictions fall within the 0.95–1.00 range, which reflects high stability and consistency of the classifier under the analysed conditions. At the level of the entire dataset, the model only rarely produces decisions with very low probability.

Figure 6.

Overall distribution of prediction probability (AI probability) for AI decisions in agreement (green) and disagreement (red) with the palynological expert (n = 5194).

Taking classification correctness into account (Figure 5 and Figure 6) makes it possible to describe several characteristic features of the model’s behaviour:

- For observations classified correctly by the AI model, in agreement with the expert, the distribution is dominated by a very narrow range of high prediction probability values, the vast majority of decisions have a probability close to 1.0.

- For misclassified observations, the distribution of prediction probability is clearly wider: the average confidence level is lower, intermediate values (approx. 0.80–0.95) occur more frequently and there are individual cases with very low probability, although some incorrect classifications are still associated with high declared confidence.

- This shape of the distributions indicates that information on prediction probability (AI probability) can serve as a useful warning indicator: low or intermediate values signal an increased risk of error, even though they do not completely eliminate the possibility of “confident but wrong” model decisions.

In the course of a qualitative review carried out jointly with the palynological expert, it was additionally found that misclassifications more often concern images of reduced quality, in particular

- With suboptimal depth of field (part of the grain remains outside the focal plane or strong contamination of the slide is visible in the frame);

- With reduced contrast between the grain and the background;

- With the presence of background artefacts (air bubbles, crystals, wax fragments) that hinder automatic segmentation.

In such cases, prediction probability values tend to deviate more strongly from 1.0 and show greater variability between individual samples, which further confirms the usefulness of this measure as a signal requiring increased expert vigilance. The combined use of two complementary visualisations of the model’s prediction probability (Figure 5 and Figure 6), supplemented by representative examples of lower-quality images, makes it possible to clearly link imaging parameters to AI behaviour and to identify situations in which the classification result should be treated as requiring additional expert verification.

4. Discussion

4.1. System Limitations and Directions for Further Research

The validation results confirmed very high agreement between the AI model and the palynological expert; however, a more detailed analysis revealed several limitations that need to be taken into account in further system development and when planning its implementation. As in other applications of artificial intelligence in pollen analysis and honey authentication, the effectiveness of the solution remains closely linked to data quality, imaging conditions and the way the model is integrated with laboratory practice and food safety management systems [15,25,29,33,35,36,37].

An important limitation concerns, first and foremost, the representativeness of the training dataset. The current image database was built using honey samples originating from countries most common on the Polish retail market: in addition to domestic Polish honeys and honeys from the EU, it includes a wide range of Chinese and Ukrainian honey profiles, which is consistent with the approach of many honey authenticity systems that initially focus on a specific geographical region [3,5,8,15]. This, however, means that the generalisation capacity of the model may be limited for honeys outside this area, both from other climatic zones and with different forage structures, as well as for rare or exotic pollen types. In particular, honeys from MERCOSUR countries and from Central and North America are only weakly represented in the database. Palinological literature and studies on computer-based pollen recognition emphasise that global classification systems require the gradual expansion of databases to include new plant species and regions, while maintaining high quality of expert annotations [27,32,33,34,63,64].

Another limitation is the reduced classification accuracy for rare and morphologically similar classes. In the present system (cf. Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8), this concerned in particular grains with reticulate exine ornamentation and medium wall thickness, for which the proportion of misclassifications was higher than for grains with distinct echinate ornamentation and extreme wall thickness (very thin or very thick). This phenomenon is consistent with observations made for other AI models used in pollen and biological image classification: uneven class frequencies and similarity of morphological features promote the occurrence of distribution shift and deterioration of performance in the area of rare, borderline or atypical examples [29,31,33,35,36,37,63]. In laboratory practice, this implies the need for deliberate rebalancing of datasets with respect to under-represented classes, the use of methods dedicated to imbalanced data (e.g., balanced data augmentation, cost-sensitive learning) and consideration of more advanced modelling strategies, such as model ensembles or active learning involving expert feedback.

From a technical perspective, image quality remains a particularly important limitation for implementation in honey laboratories. Despite the use of a standardised procedure for slide preparation, variation in depth of field, contrast and the level of background noise proved to be a significant factor differentiating classification performance. The AI model’s erroneous decisions more frequently involved images with suboptimal depth of field, oversharpening, reduced contrast or numerous artefacts (air bubbles, crystals, wax fragments), which is consistent with observations from other studies on automatic pollen identification and biological image analysis systems [1,25,46,47]. In the context of ISO/IEC 17025 [45] accreditation requirements, it therefore becomes necessary not only to describe but also to formally document the minimum quality criteria for images (microscope and camera parameters, acceptance/rejection criteria for images) and, ultimately, to develop automated image quality control modules that would assess, among others, sharpness, contrast and noise levels before an image is passed to the classifier.

From the perspective of end users and regulatory compliance, the limited transparency of the deep learning models employed is also of considerable importance. In the present study, a deep convolutional neural network (ResNet152) was used, which—similarly to other deep learning architectures, including the hybrid ViT + CNN variant developed in earlier stages of the NUTRITECH project [15], operates as a “black box”. This makes it difficult to explain which regions of the image and which morphological features were decisive for assigning a given label. In the literature on AI applications in food analysis and bee products, increasing emphasis is placed on explainable artificial intelligence (XAI), including attention maps, visualisation of decision regions and methods for assessing feature importance [6,25,31,36,37]. The use of such solutions in the present system, for example, in the form of heat maps highlighting pollen grain regions most relevant for classification, could increase user trust, facilitate auditing and better embed the system within food fraud risk management practice [15,53,54,55].

These limitations are further complemented by system-level and implementation challenges. The study presented here was designed as a validation conducted under controlled laboratory conditions with a strictly standardised sample preparation and imaging protocol. To fully assess the usefulness and reliability of the system, further work is required, including operational testing under real working conditions in honey laboratories, inter-laboratory studies (different optical equipment, different operator teams), integration with laboratory information management systems (LIMS), a structured assessment of the cost-effectiveness of implementation—including the balance between initial investment costs (hardware, IT infrastructure, software licensing) and long-term operational savings (reduced labour input, higher throughput and lower logistics costs) in laboratories of different scales, from small in-house honey testing units to large official control laboratories—and analysis of end-user experience [15,41,65]. These aspects fit into the broader context of building intelligent systems for assuring food quality and authenticity, in which AI modules are integrated with a company’s digital infrastructure and with the requirements of ISO 22000 and private standards (IFS, BRCGS) related to food fraud risk management [54,55,66].

In summary, further development of the system should include broadening and diversifying the database (new plant species, different regions, rare classes), applying methods to address distribution shift and class imbalance, introducing automated image quality control modules and integrating XAI solutions that enable better interpretation of model decisions. Only by incorporating these elements will it be possible to fully exploit the potential of the developed system in honey laboratories and within the broader ecosystem of digital food authenticity assurance.

4.2. Implementation Potential and Interoperability of the AI System

The developed AI-based pollen grain classification system is the final outcome of the NUTRITECH.I-004A/22 project and can be regarded as a mature prototype with clearly defined implementation potential. It fits within the broader concepts of “Food Quality 4.0” and Industry 4.0, in which image data and AI algorithms become an integral part of the digital food value chain supporting quality management, authenticity assurance and product traceability [15,41,65,67].

The system architecture was designed with a high degree of interoperability in mind, both at the hardware and IT infrastructure levels. The AI classification module can interface with different types of optical microscopes and digital cameras, provided that predefined image quality parameters are maintained. From an IT perspective, the use of application programming interfaces (APIs) and standard data exchange formats (JSON, XML) enables integration with Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS), food quality monitoring platforms and other honey authentication modules, such as spectroscopic, chromatographic and DNA-based solutions [5,8,21,22,23]. In this way, the system can act as a specialised component within larger, integrated architectures for intelligent food quality and authenticity assurance [36,37,65].

An important feature of the proposed solution is its alignment with the FAIR data principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable). This not only facilitates data re-use in subsequent research and innovation projects, but also supports their integration into broader digital ecosystems—from databases used in VACCP (Vulnerability Assessment and Critical Control Points) systems to registries maintained by competent authorities and certification bodies [15,41,54,66]. The ability to export results in standardised formats and to generate reports automatically supports audit processes and regulatory reporting, in line with current trends in the development of intelligent food safety and authenticity assurance systems at EU level [68,69,70].

From the perspective of routine operations in honey laboratories and along the honey supply chain, tangible benefits relate in particular to analysis time, reproducibility of results and process scalability. Table 9 provides a synthetic comparison of the traditional expert-based melissopalynological method and the developed AI system.

Table 9.

Comparison of pollen grain classification methods: traditional expert-based analysis vs. AI system.

This comparison indicates that the AI system can serve as a high-throughput tool to support expert work, especially in screening analyses and routine control of large numbers of samples. In inspection practice and within food fraud prevention plans (VACCP), the automatic pollen classification module can complement other analytical techniques, from spectroscopic methods to chemometric tools and big data systems, thereby supporting rapid detection of warning signals [11,15,54,66,71]. Importantly, the analysis times and operational costs reported for the AI-based system in Table 9 refer to the stage after sample preparation and image acquisition; sample preparation (approximately 20–40 min per honey sample, according to PN-88/A-77626) is required in both workflows and was therefore included as a separate, identical criterion for both methods.

At the same time, fully realising the implementation potential of the system requires appropriate organisational and technical preparedness. It is necessary to ensure stable IT infrastructure, define procedures for integration with LIMS and with food safety and quality management systems (ISO 22000, IFS, BRCGS), and develop guidelines on staff qualifications for system operators [54,55,66]. Training programmes combining palynological and digital perspectives should form an essential part of implementation, so that users understand both the limitations of AI models and how to interpret their uncertainty indicators and XAI outputs.

Against the backdrop of current concepts of digital transformation in the food supply chain, the developed system can be viewed as a component of an integrated infrastructure for honey authenticity assurance. It is capable of interoperating with other technologies (NIRS, RFID, blockchain, IoT, fraud databases), supporting both operational decisions in the laboratory and strategic activities in the areas of food fraud risk management and consumer trust building [41,42,43,65,71]. In this context, the validation results presented in this study represent an important step on the path from research prototype to a tool ready for deployment in industrial and institutional settings.

5. Summary and Conclusions

This study confirmed that the developed artificial intelligence system can effectively support the classification of pollen grains present in five monofloral honey types, achieving very high agreement with the assessment of a palynological expert. The overall classification performance (more than 95% matching labels in the entire dataset) indicates that the AI model meets the requirements for tools intended to support melissopalynological analysis under routine laboratory conditions.

All four research hypotheses (H1–H4) were supported. The AI-based classification showed substantial agreement with expert assessment, was strongly influenced by morphological traits and image quality, and demonstrated implementation potential in honey quality and authenticity control, although full confirmation of H4 will require further operational testing under real laboratory conditions.

Based on the obtained results, the following concise conclusions were drawn:

- The AI system achieves classification performance comparable to that of a palynology expert, particularly for dominant pollen classes, which confirms its usefulness as a decision-support tool in melissopalynological analysis (H1).

- Morphological traits of pollen grains (especially exine ornamentation and exine thickness), together with image quality parameters (depth of field, contrast, level of background noise), are key determinants of classification performance. The prediction probability (confidence score) assigned by the model can be used as a practical indicator of classification uncertainty and as a criterion for flagging samples for repeated expert review (H2–H3).

- Extending and diversifying the training dataset, in particular by adding rare classes, morphologically similar plant taxa and material from other geographic regions, is essential for further improving the model’s generalisation capability and its usefulness in international applications.

- The system has substantial implementation potential in honey laboratories and in food authenticity control systems, provided that standardised imaging procedures are maintained, minimum image quality criteria are defined and integration with existing IT infrastructure (LIMS, quality systems) is ensured. This justifies further work on operational testing, integration with other analytical tools and the development of explainable AI modules, including embedding the system within VACCP plans and honey fraud prevention procedures (H4).

In summary, the validation stage of the AI model completed within the NUTRITECH.I-004A/22 project indicates that AI-based digital pollen analysis can become an important component of modern systems for honey quality and authenticity assurance, provided that the image database and imaging protocols are further expanded and standardised, sources of uncertainty are monitored, and integration with routine laboratory practice and food safety management systems is systematically developed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152413009/s1, Table S1: Pollen classes and number of microscopic images used to train the general ResNet152 model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K.B. and P.R.; methodology, J.K.B. and B.L.; formal analysis, J.K.B., P.R. and B.L.; investigation, P.R. and B.L.; data curation, J.K.B., P.R. and B.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K.B., P.R. and B.L.; writing—review and editing, J.K.B. and P.R.; visualization, J.K.B. and B.L., supervision, J.K.B., B.L. and P.R.; project administration J.K.B., B.L. and P.R.; funding acquisition, P.R. and J.K.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article was prepared as part of the project NUTRITECH.I-004A/22, titled “Development and implementation of a globally innovative digital pollen analysis service for honey using automation and artificial intelligence technologies for application in the functional food production sector”, implemented by AI Technika sp. z o.o. The project is co-financed by the National Centre for Research and Development (NCBR, Poland) under the 1st call of the government programme NUTRITECH—Nutrition in light of challenges to improve the well-being of society and climate change, within thematic area T3: Technological and economic aspects of proper nutrition.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author Przemysław Rujna przemyslaw.rujna@aitechnika.com.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Przemysław Rujna was employed by the AI Technika Sp. z o.o. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Tkacz, E.; Rujna, P.; Więcławek, W.; Lewandowski, B.; Mika, B.; Sieciński, S. Application of 2D extension of Hjorth’s descriptors to distinguish defined groups of bee pollen images. Foods 2024, 13, 3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilczyńska, A.; Banach, J.K.; Żak, N.; Grzywińska-Rąpca, M. Preliminary studies on the use of an electrical method to assess the quality of honey and distinguish its botanical origin. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 12060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-H.; Gu, H.-W.; Liu, R.-J.; Qing, X.-D.; Nie, J.-F. A comprehensive review of the current trends and recent advancements on the authenticity of honey. Food Chem. X 2023, 19, 100850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhlaei, R.; Selamat, J.; Khatib, A.; Razis, A.F.A.; Sukor, R.; Ahmad, S.; Babadi, A.A. The toxic impact of honey adulteration: A review. Foods 2020, 9, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, S.; Amaral, J.S.; Beatriz, M.; Oliveira, P.P.; Mafra, I. A comprehensive review on the main honey authentication issues: Production and origin. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 1072–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Abdulla, W. Explainable AI-driven wavelength selection for hyperspectral imaging of honey products. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 3, 100491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.K.; Barbour, E.; Locher, C. Authentication of Jarrah (Eucalyptus marginata) honey through its nectar signature and assessment of its typical physicochemical characteristics. Peer. J. Anal. Chem. 2024, 6, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsagkaris, A.; Koulis, G.A.; Danezis, G.P.; Martakos, I.; Dasenaki, M.; Georgiou, C.A.; Thomaidis, N.S. Honey authenticity: Analytical techniques, state of the art and challenges. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 11273–11294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurica, K.; Brčić Karačonji, I.; Lasić, D.; Bursać Kovačević, D.; Putnik, P. Unauthorized Food Manipulation as a Criminal Offense: Food Authenticity, Legal Frameworks, Analytical Tools and Cases. Foods 2021, 10, 2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.C.; Spink, J.; Lipp, M. Development and application of a database of food ingredient fraud and economically motivated adulteration from 1980 to 2010. J. Food Sci. 2012, 77, R118–R126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everstine, K.D.; Chin, H.B.; Lopes, F.A.; Moore, J.C. Database of Food Fraud Records: Summary of Data from 1980 to 2022. J. Food Prot. 2024, 87, 100227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. EU Coordinated Action “From the Hives” (Honey 2021–2022). Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/food-safety/eu-agri-food-fraud-network/eu-coordinated-actions/honey-2021-2022_en (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- European Commission. The EU Agri-Food Fraud Network. 2022. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/food-safety/eu-agri-food-fraud-network_en (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- FEEDM. Statement on the Need of Harmonisation of Analytical Methods for Honey Authenticity. 2023. Available online: https://www.feedm.com/publications/f-e-e-d-m-statements/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Banach, J.K.; Rujna, P.; Lewandowski, B. Integrated Process Oriented Approach for Digital Authentication of Honey in Food Quality and Safety Systems A Case Study from a Research and Development Project. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escriche, I.; Juan-Borrás, M.; Visquert, M.; Valiente, J.M. An overview of the challenges when analysing pollen for monofloral honey classification. Food Control 2023, 143, 109305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-88/A-77626; Miod Pszczeli. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny: Warsaw, Poland, 1988. (In Polish)

- The Council of the European Union. Council Directive 2001/110/EC of 20 December 2001 Relating to Honey; Council of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2001.

- Adamchuk, L.; Sukhenko, V.; Akulonok, O.; Bilotserkivets, T.; Vyshniak, V.; Lisohurska, D.; Lisohurska, O.; Slobodyanyuk, N.; Shanina, O.; Galyasnyj, I. Methods for determining the botanical origin of honey. Slovak J. Food Sci. 2020, 14, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotiropoulou, N.S.; Xagoraris, M.; Revelou, P.-K.; Kaparakou, E.H.; Kanakis, C.; Pappas, C.; Tarantilis, P.A. The use of SPME-GC-MS, IR and Raman techniques for botanical and geographical authentication and detection of adulteration of honey. Foods 2021, 10, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, J.C.; da Costa, P.M. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Use in Honey Characterization and Authentication: A systematic review. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 1817–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, D. Advances in spectrometric techniques in food analysis and authentication. Foods 2023, 12, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifković, J.; Andrić, F.; Ristivojević, P.; Guzelmeric, E.; Yesilada, E. Analytical methods in tracing honey authenticity. J. AOAC Int. 2023, 100, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, S.; Rodrigues, F.; Delerue-Matos, C. Towards DNA-Based Methods Analysis for Honey: An Update. Molecules 2023, 28, 2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenchouni, H.; Laallam, H. Revolutionizing food quality assessment: Unleashing the potential of artificial intelligence for enhancing honey physicochemical, biochemical, and melissopalynological insights. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2024, 23, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teye, E.; Amuah, C.L.; Lamptey, F.P.; Obeng, F.; Nyorkeh, R. Artificial intelligence for honey integrity in Ghana: A feasibility study on the use of smartphone images coupled with multivariate algorithms. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 8, 100453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chippa, P.; Hu, S.; Pound, M.; Yawar, S.A.; Baniulis, D. Honey authentication using AI-based pollen analysis: A UK review. Br. Food J. 2025, 127, 4512–4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, T.; Choi, J.; Park, K.R. Artificial intelligence-based classification of pollen grains using attention-guided pollen features aggregation network. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2023, 35, 740–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.N.; Nguyen, D.M.; Giang, A.C.; Pham, H.T.; Le, T.L.; Vu, H. Identification of Botanical Origin from Pollen Grains in Honey Using Computer Vision-Based Techniques. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiente González, J.M.; Martín-Osuna, J.J.; Peral, A.M.; Escriche, I. Assisting monofloral honey classification by automated pollen identification based on convolutional neural networks. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 90, 103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamrat, F.M.J.M.; Idris, M.Y.I.; Zhou, X.; Khalid, M.; Sharmin, S.; Sharmin, Z.; Ahmed, K.; Moni, M.A. PollenNet: A novel architecture for high precision pollen grain classification through deep learning and explainable AI. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Zhao, J.; Xu, Z.; Wei, J.; Wang, Q.; Shen, F.; Yang, X.; Guo, Z. AIpollen: An Analytic Website for Pollen Identification Through Convolutional Neural Networks. Plants 2024, 13, 3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viertel, P.; König, M. Pattern recognition methodologies for pollen grain image classification: A survey. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2022, 33, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.B.; Souza, J.S.; Silva, G.G.D.; Cereda, M.P.; Pott, A.; Naka, M.H.; Pistori, H. Feature extraction and machine learning for the classification of brazilian savannah pollen grains. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhu, H. Artificial intelligence in food safety: A decade review and bibliometric analysis. Foods 2023, 12, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gu, H.-W.; Yin, X.-L.; Geng, T. Deep learning in food safety and authenticity detection: An integrative review and future prospects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 146, 104396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Wang, T.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yun, Y.-H. Deep learning in food authenticity: Recent advances and future trends. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 144, 104344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropodi, A.I.; Panagou, E.Z.; Nychas, G.J.E. Data Mining Derived from Food Analyses Using Non-Invasive/Non-Destructive Analytical Techniques; Determination of Food Authenticity, Quality & Safety in Tandem with Computer Science Disciplines. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidyalakshmi, T.; Jyoti, B.; Mansuri, S.M.; Srivastava, A.; Mohapatra, D.; Kalnar, Y.B.; Narsaiah, K.; Indore, N. Application of artificial intelligence in food processing: Current status and future prospects. Food Eng. Rev. 2025, 17, 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, P.; Leema, A.A.; Jothiaruna, N.; Assudani, P.J.; Sankar, K.; Kulkarni, M.B.; Bhaiyya, M. Artificial Intelligence for Food Safety: From Predictive Models to Real-World Safeguards. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 163, 105153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukacs, M.; Toth, F.; Horvath, R.; Solymos, G.; Alpár, B.; Varga, P.; Kertesz, I.; Gillay, Z.; Baranyai, L.; Felfoldi, J.; et al. Advanced Digital Solutions for Food Traceability: Enhancing Origin, Quality, and Safety Through NIRS, RFID, Blockchain, and IoT. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2025, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbene, F.; Gay, P.; Tortia, C. Traceability issues in food supply chain management: A review. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 120, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, P.; Borit, M. How to define traceability. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 29, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 22000:2018; Food Safety Management Systems—Requirements for Any Organization in the Food Chain. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- ISO/IEC 17025:2017; General Requirements for the Competence of Testing and Calibration Laboratories. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Jia, W.; Georgouli, K.; Martinez-Del Rincon, J.; Koidis, A. Challenges in the Use of AI-Driven Non-Destructive Spectroscopic Tools for Rapid Food Analysis. Foods 2024, 13, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, R.; García-Orellana, C.J.; González-Velasco, H.M.; Garcia-Manso, A.; Tormo-Molina, R.; Macías-Macías, M.; Abengózar, E. Automated multifocus pollen detection using deep learning. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 72097–72112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodopoulou, M.A.; Tananaki, C.; Dimou, M.; Liolios, V.; Kanelis, D.; Goras, G.; Thrasyvoulou, A. The determination of the botanical origin in honeys with over-represented pollen: Combination of melissopalynological, sensory and physicochemical analysis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 2705–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakoori, Z.; Mehrabian, A.; Minai, D.; Salmanpour, F.; Khajoei Nasab, F. Assessing the quality of bee honey on the basis of melissopalynology as well as chemical analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wäldchen, J.; Mäder, P. Plant Species Identification Using Computer Vision Techniques: A Systematic Literature Review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2018, 25, 507–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhang, H. Deep learning for plant identification in natural environment. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2017, 1, 7361042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brar, D.S.; Aggarwal, A.K.; Nanda, V.; Saxenac, S.; Gautamc, S. AI and CV based 2D-CNN algorithm: Botanical authentication of Indian honey. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, L.; Soon, J.M. Food fraud vulnerability assessment: Reliable data sources and effective assessment approaches. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popping, B.; Buck, N.; Bánáti, D.; Brereton, P.; Gendel, S.; Hristozova, N.; Chaves, S.M.; Saner, S.; Spink, J.; Wunderlin, D. Food inauthenticity: Authority activities, guidance for food operators, and mitigation tools. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 4776–4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, L.; MacLeod, A.; James Ch Thompson, M.; Oyeyinka, S.; Cowen, N.; Skoczylis, J.; Onarinde, B.A. Food fraud prevention strategies: Building an effective verification ecosystem. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e70036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banach, J.K.; Rujna, P.; Pietrzak-Fiećko, R. Quality management of honey in the bani world: Consumer perceptions and market responses. Scientific Papers of Silesian University of Technology. Organization and Management. 2026; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, R. Pollen Identification for Beekeepers; University College Cardiff Press: Cardiff, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Louveaux, J.; Maurizio, A.; Vorwohl, G. Methods of melissopalynology. Bee World 1978, 59, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou, G.; Arcos, J.L.; Cerquides, J. Enhancing medical image segmentation: Ground truth optimization through evaluating uncertainty in expert annotations. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylolypavan, A.; Sleeman, D.; Wu, H.; Sim, M. The impact of inconsistent human annotations on AI driven clinical decision making. NPJ Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, I.R.; Cardoen, B.; Khater, I.M.; Gao, G.; Wong, T.H.; Hamarneh, G. AI analysis of super-resolution microscopy: Biological discovery in the absence of ground truth. J. Cell Biol. 2024, 223, e202311073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofre, S.; Sanchez, C.; Quezada-Figueroa, G.; López-Cortés, X.A. Validity and accuracy of artificial intelligence-based dietary intake assessment methods: A systematic review. Br. J. Nutr. 2025, 133, 1241–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourel, B.; Marchant, R.; de Garidel-Thoron, T.; Tetard, M.; Barboni, D.; Gally, Y.; Beaufort, L. Automated recognition by multiple convolutional neural networks of modern, fossil, intact and damaged pollen grains. Comput. Geosci. 2020, 140, 104498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Brereton, P.; Campbell, K. Progress towards achieving intelligent food assurance systems. Food Control 2024, 164, 110548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punyasena, S.W.; Haselhorst, D.S.; Kong, S.; Fowlkes, C.C.; Moreno, J.E. Automated identification of diverse Neotropical pollen samples using convolutional neural networks. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2022, 13, 2049–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, A.; Iqbal, S.Z.; Bhatti, I.A.; Alim, M.B.; Waseem, M.; Iqbal, M.; Khaneghah, A.M. Food authentication, current issues, analytical techniques, and future challenges: A comprehensive review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treiblmaier, H.; Garaus, M. Using blockchain to signal quality in the food supply chain: The impact on consumer purchase intentions and the moderating effect of brand familiarity. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 68, 102514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO. International and National Regulatory Strategies to Counter Food Fraud; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/ca5299en (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Consolidated Annual Activity Report 2021; EFSA: Parma, Italy, 2022; Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2022-03/ar2021.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- FoodDrinkEurope. Guidance on Food Fraud Vulnerability Assessment and Mitigation. 2020. Available online: https://www.fooddrinkeurope.eu/policy-area/food-fraud/ (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Hall, D.C. Managing Fraud in Food Supply Chains: The Case of Honey Laundering. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]