Abstract

The performance of infrared small target detection is often hindered by spurious correlations learned between features and labels. To address this feature bias at its root, this paper proposes a debiased detection framework grounded in causal reasoning. Built upon the YOLOv7-tiny architecture, the framework introduces a three-stage debiasing mechanism. First, a Structural Causal Model (SCM) is adopted to disentangle causal features from non-causal image cues. Second, a Causal Attention Mechanism (CAM) is embedded into the backbone, where a causality-guided feature weighting strategy enhances the model’s focus on semantically critical target characteristics. Finally, a Causal Intervention (CI) module is incorporated into the neck, leveraging backdoor adjustments to suppress spurious causal links induced by contextual confounders. Extensive experiments on the public FLIR_ADASv2 dataset demonstrate notable gains in feature discriminability, with improvements of 2.9% in mAP@50 and 2.7% in mAP@50:95 compared to the baseline. These results verify that the proposed framework effectively mitigates feature bias and enhances generalization capability, outperforming the baseline by a substantial margin.

1. Introduction

Infrared imaging technology is a powerful means of capturing thermal radiation, offering robust perception capabilities even under low-light or adverse weather conditions. These advantages make it indispensable for applications such as autonomous driving, intelligent transportation, and military reconnaissance. Nevertheless, infrared imagery suffers from inherent limitations, including low contrast, low signal-to-noise ratios, and limited texture information, which create severe challenges for small target detection. Small targets typically occupy only a few pixels and lack distinct structural cues, leading to weak and unstable feature representations. In addition, heavy thermal noise further reduces the discriminability of targets from the background, often resulting in false alarms and missed detections.

Existing infrared small target detection methods can be broadly divided into traditional handcrafted feature-based approaches and modern deep learning-based models. Traditional approaches rely heavily on prior knowledge to design features, limiting their adaptability and generalization in complex, dynamic real-world environments. Deep learning methods, particularly those of the YOLO family, have improved detection performance through data-driven, end-to-end representation learning. However, their effectiveness remains constrained by two fundamental challenges: (1) a dependence on large-scale, high-quality annotated datasets and (2) a tendency to learn spurious statistical correlations in the data rather than capturing the true causal factors underlying target presence.

Causal reasoning theory [1,2,3,4] provides a new paradigm for fundamentally addressing feature bias. By explicitly distinguishing true causal mechanisms from non-causal, spurious correlations, it offers a principled framework for correcting false dependencies introduced by biased datasets. In recent years, causal reasoning has shown strong potential in computer vision. For example, Huang et al. [5] introduced a structural causal model into object detection to improve generalization by intervening on contextual confounders. Guo et al. [6] proposed a causal attention mechanism that effectively suppresses background interference in cell detection. Likewise, Zhang et al. [7] and Kim et al. [8] enhanced robustness in ship detection and multispectral pedestrian detection through causal enhancement strategies. Shao et al. [9] further designed a multidimensional causal intervention mechanism that significantly reduces inter-class co-occurrence bias.

Despite these advances, most existing causal research has concentrated on visible-light or specific-modality detection tasks. Due to the distinctive characteristics of feature bias in infrared imagery, constructing a unified, end-to-end causal learning framework that accurately captures and debiases the essential causal features of small targets remains a key unresolved challenge. To this end, the major contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- We construct a structural causal model specifically designed for infrared scenarios, formally distinguishing causal features from non-causal ones. This provides the theoretical foundation for analyzing the root sources of feature deviation.

- (2)

- We develop YOLOv7-tiny-CR, an enhanced architecture that incorporates a CAM into the backbone to emphasize causally relevant target features. In addition, a CI module is introduced into the neck to inhibit the propagation of contextual bias, thereby achieving debiasing at the model level.

- (3)

- Extensive experiments on the public FLIR_ADASv2 dataset demonstrate that the proposed framework significantly improves feature discriminability. It achieves notable gains over the baseline in both mAP@50 and mAP@50:95, validating its effectiveness in mitigating feature bias and enhancing generalization.

This study is designed to verify the central hypothesis that the proposed causal reasoning modules (CAM and CI) can effectively mitigate feature bias and enhance model generalization. In this context, the architectural components (CAM and CI) are treated as independent variables, whereas detection performance metrics (mAP@50 and mAP@50:95) serve as dependent variables. The hypothesis is rigorously evaluated through comparative experiments against well-established baselines and comprehensive ablation studies conducted on the FLIR_ADASv2 dataset.

2. Methods

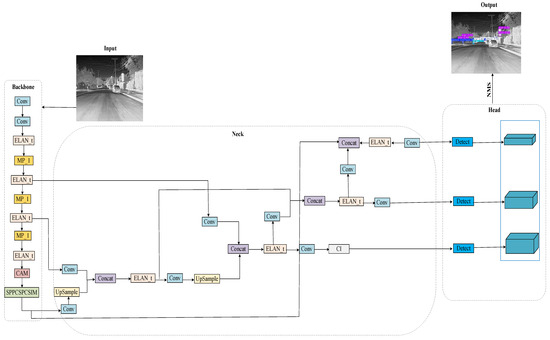

2.1. YOLOv7-tiny-CR Model

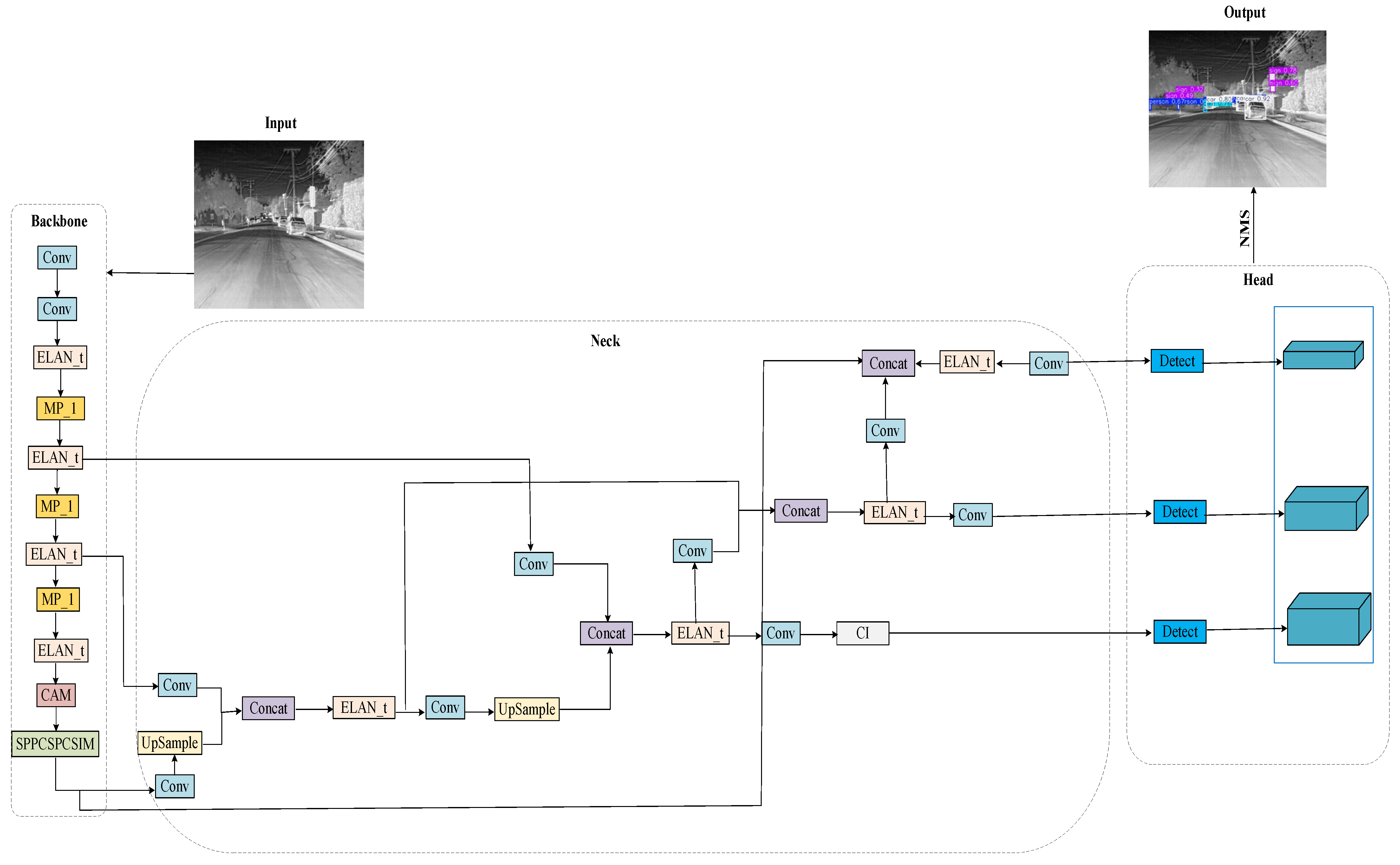

As shown in Figure 1, this paper introduces the YOLOv7-tiny-CR detection model, a specific implementation of a feature-depolarization-oriented causal intervention framework designed for infrared small target detection. The model is composed of five components: Input, Backbone, Neck, Head, and Output. Based on the YOLOv7-tiny baseline, the framework systematically mitigates feature bias by integrating two causal modules into the main pathways of feature extraction and fusion. Specifically, the input image first passes through the Input stage. Following collaborative processing by the Conv, ELAN_t, and MP_1 modules, preliminary feature extraction is completed. Next, a CAM module is added to the Backbone network, which helps the model focus more on semantically essential features by dynamically amplifying feature responses that have strong causal links to the target. The model then utilizes a PAN-FPN [10] structure for bidirectional feature fusion, effectively integrating feature representations across multiple scales. This fusion process is further enhanced by the addition of a CI module in the small-object detection layer of the Neck network. The CI module applies a backdoor adjustment strategy to block spurious correlations introduced by contextual confounders during feature aggregation, thereby suppressing the sources of feature bias. Working together, the CAM and CI modules ensure that the features passed to the detection head possess strong causal discriminability. Finally, the individual outputs from each layer are merged using the Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) algorithm to produce precise bounding boxes, enabling accurate and reliable detection of infrared small targets.

Figure 1.

Structure diagram of YOLOv7-tiny-CR model.

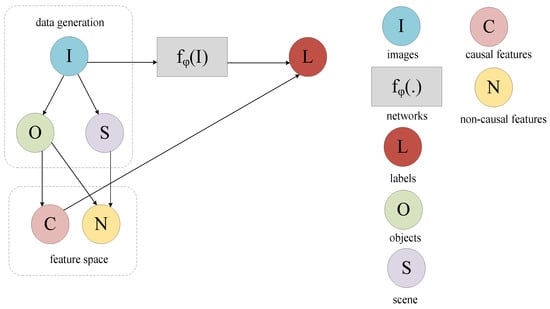

2.2. Structural Causal Model

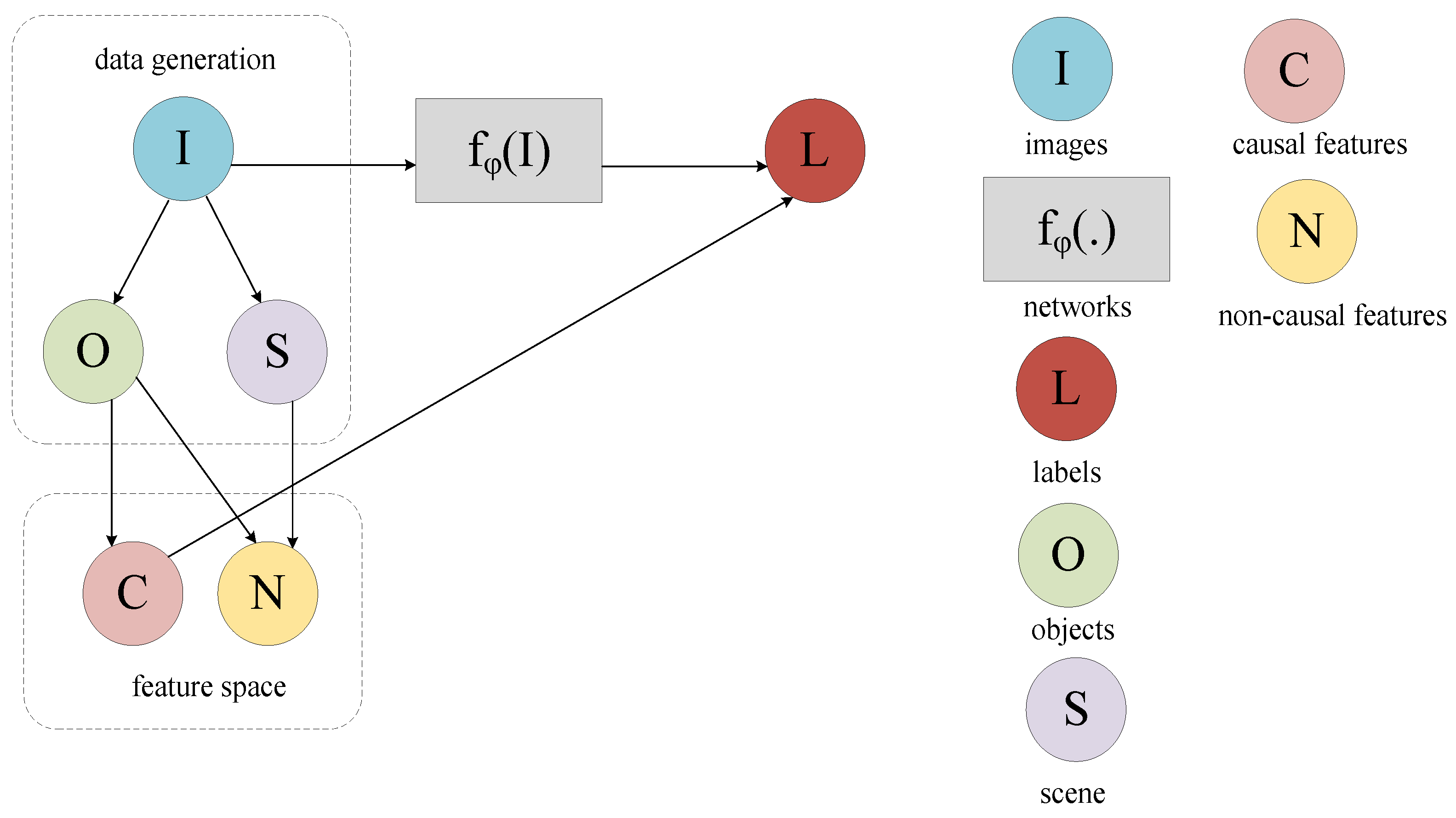

As shown in Figure 2, this paper introduces a conceptual Structural Causal Model (SCM) [11] to formally represent the assumed causal relationships among key variables in the infrared small target detection task. Depicted as a directed acyclic graph, the SCM provides a theoretical framework for analyzing the relationships between input images, extracted features, and final classification labels. Following the principle of causal invariance, the core variables are defined as follows: causal features are those attributes that maintain inherent and stable causal relationships with target existence, whereas non-causal features represent characteristics that lack necessary causal links to the target but may form spurious statistical correlations in the data. In this study, causal and non-causal features are not pre-specified with explicit thresholds in the input space. Rather, the SCM provides a conceptual framework that delineates their roles and relationships. This formalization establishes the direct causal influence of features on detection outcomes and highlights the potential of non-causal features to act as confounders. Consequently, the SCM serves as a theoretical foundation for future feature debiasing strategies and enhances the interpretability of the model’s decision-making process.

Figure 2.

SCM structure diagram.

In the context of infrared small target detection, the variables in the SCM are defined as follows: I denotes the observed infrared image pixel array, representing a two-dimensional measurement of the thermal radiation distribution within the scene. O corresponds to the physical existence and intrinsic properties of the target of interest in the real world. C represents the feature representations directly and stably caused by the target O, including the target’s intrinsic thermal radiation distribution and geometric shape features that remain invariant under changes in the background S. N denotes feature representations that exhibit spurious correlations with the target O due to confounding effects of the background S; these typically correspond to local background thermal noise patterns or specific contextual information that coincidentally co-occurs with the target. Finally, L represents the output of the object detector, including the predicted category and bounding box coordinates.

The inherent causal relationships within the proposed SCM are formally described by the following structural equations: (1) O ← I → S: The images I is jointly determined by the objects O and the scene S. (2) O → N ← S: The non-causal features N is a confounder-affected variable, influenced by both the objects O and the scene S, making it a primary source of spurious statistical associations, the CAM and CI modules proposed in this work are precisely designed to block this path. (3) O → C → L: The intrinsic attributes of the objects O determine its causal features C, which constitutes the genuine and direct cause for the prediction of the class labels L. (4) O → C, O → N: The objects O acts as a common cause that simultaneously generates both the causal features C and the non-causal features N, which together form the feature space for the model. (5) I → fφ(I) → L: The images I is processed by the deep learning-based detection mapping fφ(⋅), which ultimately outputs the prediction for the class labels L.

2.3. Causal Attention Mechanism Module

In convolutional neural networks, attention-based models effectively enhance local feature representation by adaptively weighting channels and spatial dimensions. This allows the network to focus on more discriminative regions, thereby significantly improving classification and detection performance. Their simplicity and computational efficiency make attention mechanisms an integral component of modern deep learning architectures.

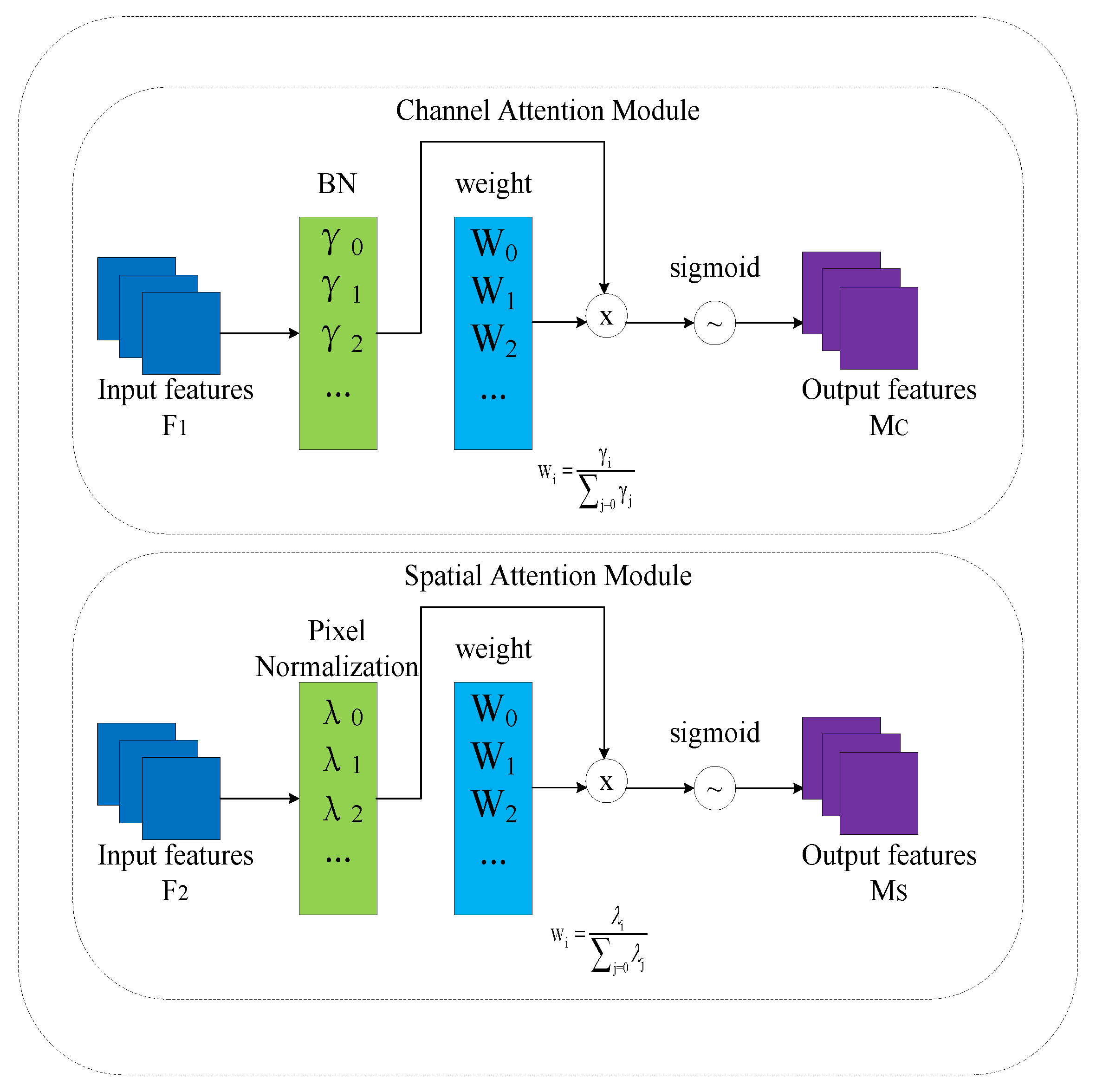

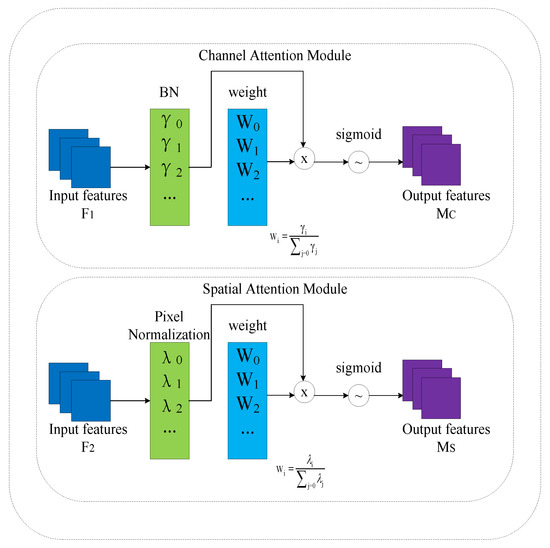

As illustrated in Figure 3, the NAM [12] attention mechanism employs a lightweight normalization operation to adaptively calibrate feature importance, enhancing discriminative power while maintaining high computational efficiency. However, a key limitation of such methods is their strong reliance on the assumption that training and test datasets are independent and identically distributed. When this assumption is violated due to distribution shifts, model performance typically degrades substantially. From a causal perspective, this fragility arises from the nature of the associations that conventional attention mechanisms learn: they primarily depend on statistical correlations between features and labels. Confounding factors in the data may induce correlations that are spurious rather than reflecting true causal relationships between features and target categories. Consequently, the model’s ability to capture robust causal relationships for reliable generalization is weakened.

Figure 3.

NAM attention mechanism structure diagram.

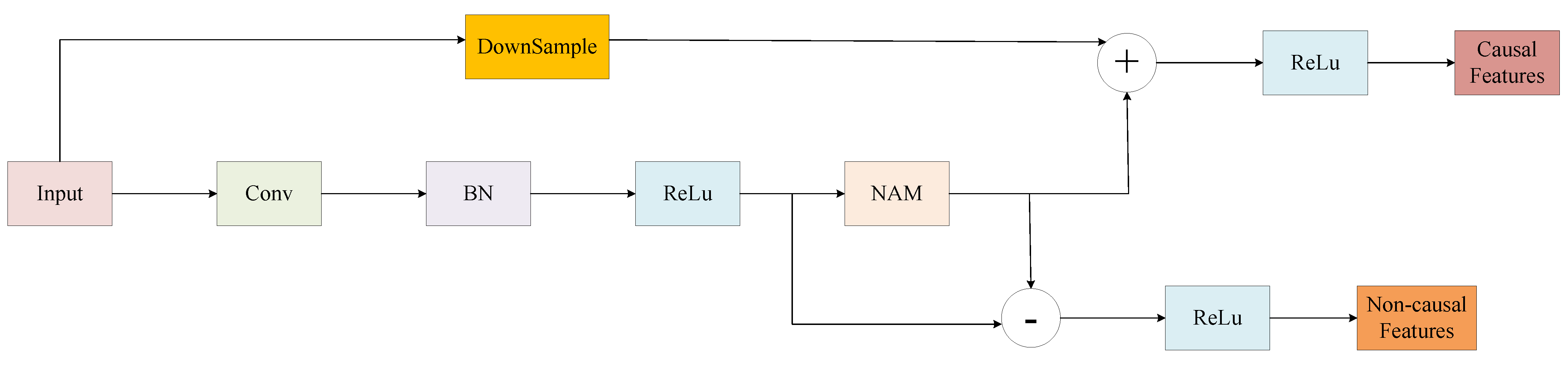

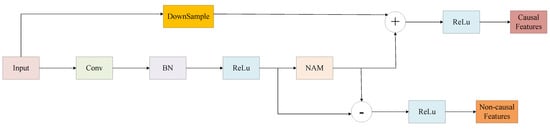

As illustrated in Figure 4, the proposed Causal Attention Mechanism (CAM) is designed to disentangle causal and non-causal components within network-level features. Its primary purpose is to generate structured feature representations that facilitate downstream causal intervention, achieved through a dedicated attention-weighting and residual computation pathway. The computational procedure of the CAM module is formally defined as follows:

where x represents the input features; z represents the features calibrated by the NAM attention mechanism; causal_features and non-causal_features represent the decoupled causal and non-causal features, respectively; residual represents the residual connection; and ReLU represents the activation function.

Figure 4.

CAM module structure diagram.

As illustrated in Figure 4, the processing flow of the proposed CAM module proceeds as follows. Given the input feature x, the module first computes a weighted causal feature representation, denoted as causal_features, using the NAM attention mechanism. This step enhances feature responses that are directly associated with the presence of the target. A key aspect of our design is the explicit construction of a non-causal pathway. This is realized by computing non_causal_features = x − causal_features via a residual connection. The rationale is that features suppressed by the NAM attention may contain spurious information related to contextual confounders. By explicitly separating these components, the causal_features are guided to provide more robust and discriminative information regarding the target, while the non_causal_features encapsulate contextual interference and confounding signals. Finally, the CAM module combines the enhanced causal features with the original input through a residual connection and applies a ReLU activation, forming the output of the backbone network. The non_causal_features are treated as explicit confounding variables and are subsequently passed to the CI module for further processing.

In summary, conventional attention mechanisms primarily rely on statistical correlations within the data, emphasizing shallow feature co-occurrence patterns and assigning weights to maximize the likelihood on the training set. This approach often overlooks the underlying causal relationships, rendering the model vulnerable to spurious correlations and limiting its capacity for generalization and interpretability in complex, real-world scenarios. In contrast, the proposed CAM module introduces a feature weighting strategy grounded in causal associations. Our method explicitly separates features into causal and non-causal components, processing them differently to reduce the model’s dependence on spurious correlations. This design effectively addresses the structural limitation that “correlation does not necessarily imply causation”. Consequently, this work provides a concrete example and a practical technical framework for advancing object detection models from a “statistical fitting” paradigm toward a “causal reasoning” paradigm.

2.4. Causal Intervention Module

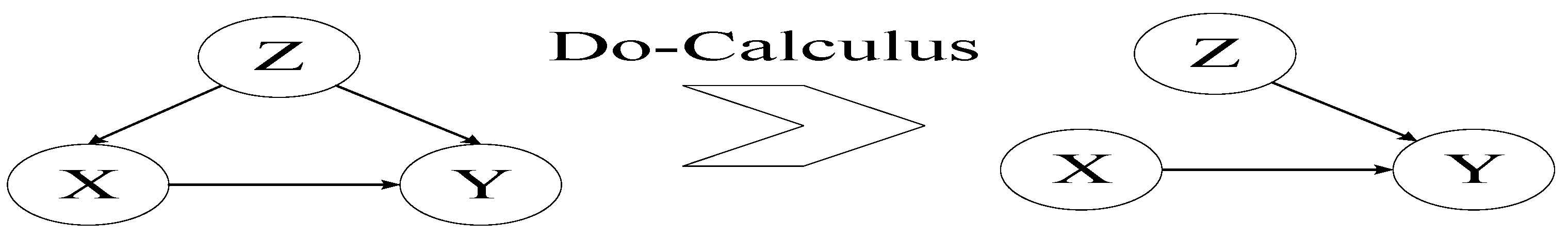

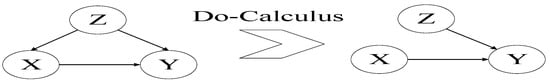

Do-Calculus, proposed by Judea Pearl, provides a rigorous formal framework for causal intervention. This framework allows researchers to mathematically identify and quantify causal effects under interventions on specific variables. At its core, the method operates on structural causal models represented as graphs, simulating the relationships among variables after intervention. This approach enables the accurate identification of true causal relationships from observed data and systematically eliminates estimation bias introduced by confounding factors.

A major challenge in causal reasoning is the presence of confounding variables factors that simultaneously influence both the treatment variable X and the outcome variable Y (as illustrated in Figure 5, left). This X ← Z → Y structure constitutes a confounder, generating a non-causal relationship and rendering the observed statistical association between X and Y an unreliable estimator of the true causal effect. Crucially, if the confounder Z is not properly controlled, the direct causal effect of X on Y cannot be accurately determined. Do-Calculus provides a principled solution to this problem: by simulating an intervention that sets X to a specific value, the influence of Z is theoretically blocked (as shown in Figure 5, right). This operation isolates the net causal effect of X on Y from any spurious associations.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of causal intervention.

In the context of infrared small target detection, the causal intervention framework is instantiated as follows (Figure 5, top). Here, X represents the visual features of the target to be predicted, and Y denotes its corresponding class label. In principle, the confounder Z should encompass all possible contextual factors that may influence both X and Y. However, enumerating all such confounders in an unsupervised setting is infeasible. To construct a tractable intervention model, this study introduces a key approximation: we assume that the diverse contextual backgrounds co-occurring with the targets constitute the primary source of confounding within the dataset. Accordingly, a unified confounding dictionary Z = is defined, where n is the number of distinct class labels and each confounder is represented by the average Region of Interest (ROI) feature of the i-th target sample in the dataset, extracted using a pre-trained Mask R-CNN model [13]. This design leverages the inherent co-occurrence patterns within the data to approximate and subsequently block the confounding effects introduced by complex real-world environments.

As illustrated on the left side of Figure 5, conventional target detectors (e.g., Mask R-CNN) are typically trained to maximize the likelihood P(Y|X). However, this standard approach is vulnerable to confounding from the dictionary Z, which can lead the model to learn spurious correlations present in the data. To formally address this issue, this paper first reformulates the traditional objective P(Y|X) using Bayes’ rule, resulting in the following formulation:

where the confounder Z generally brings about the observational bias via P(z|X).

Inspired by the integration of deep learning with causal reasoning [14], this paper innovatively introduces the interventional probability P(Y|do(X)) into the target detection task to mitigate the confounding effect of the backdoor path X ← Z → Y. To achieve this, we apply Do-Calculus, whose core principle is to theoretically sever the influence of the confounding dictionary Z on the feature X, as illustrated on the right side of Figure 5. Within this intervention framework, the backdoor adjustment method is employed to estimate P(Y|do(X)) as follows:

In Equation (3), the interventional probability P(Y|do(X)) forces the feature X to incorporate information from all factors z in the confounding dictionary Z in a balanced manner, using this integrated representation to predict Y. This mechanism effectively removes confounding bias, allowing the classifier to learn more discriminative visual representations by capturing the true causal relationship between X and Y. However, directly computing Equation (3) within a deep learning model requires a large number of costly samples, resulting in substantial training inefficiency. To overcome this challenge, the NWGM [15] is employed as an effective approximation method.

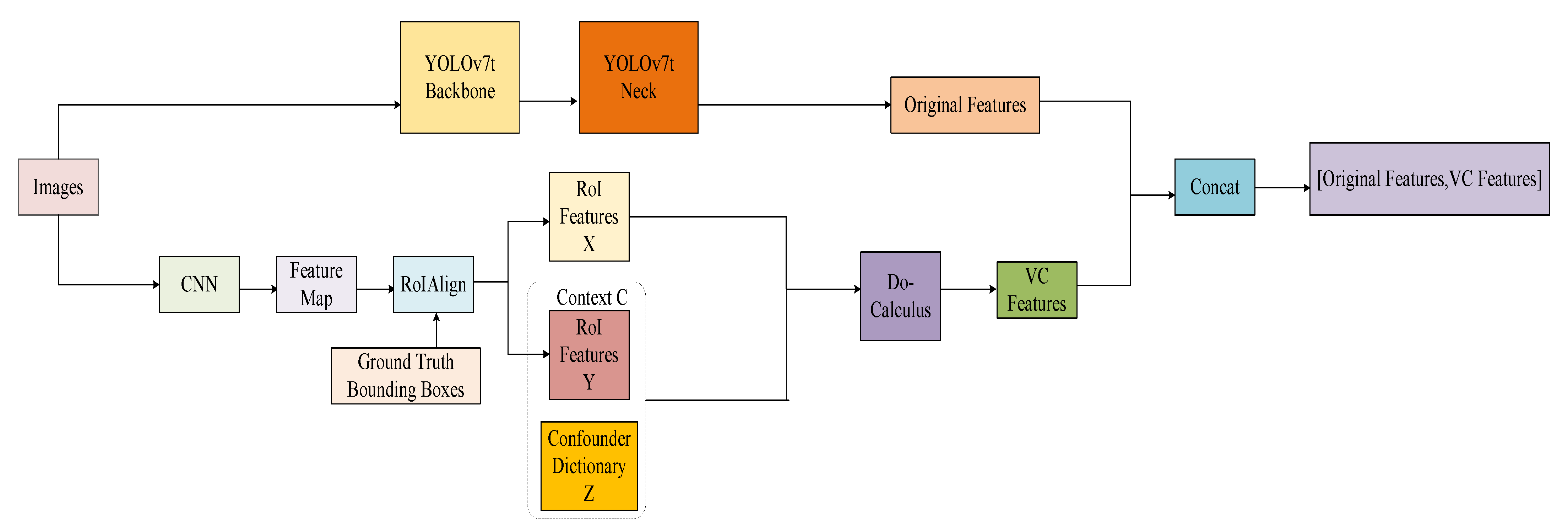

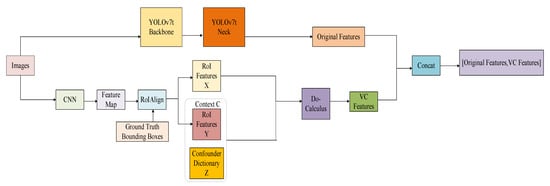

As depicted in Figure 6, the processing flow of the proposed Causal Intervention (CI) module proceeds as follows. First, a base feature map is extracted from the input image using a CNN backbone. Subsequently, leveraging the RoIAlign operation from Mask R-CNN and the ground-truth bounding boxes, the target RoI feature X and the context RoI feature Y are extracted separately. The context feature Y, together with the pre-constructed confounding dictionary Z, forms a comprehensive context feature set C. By integrating features X and C into the Do-Calculus framework and applying the backdoor adjustment method, the interventional probability P(Y|do(X)) is estimated. This process effectively removes interference from non-causal features introduced by contextual confounders, yielding a purified causal feature representation for the target. Finally, this causal feature is channel-wise concatenated with the original features output by the YOLOv7-tiny backbone and neck networks to form an enhanced composite feature representation, denoted as [Original Features, VC Features], for the final detection task. Based on the aforementioned intervention and fusion pipeline, Equation (3) is concretely implemented in our model as follows:

where concat(.) represents the vector stitching operation, represents the i-th class label, represents the probability that x belongs to class, represents the average ROI feature of the i-th class sample when the Mask R-CNN model is pre-trained, and n represents the total number of classes in the dataset.

Figure 6.

CI module structure diagram.

Object detectors operating in challenging scenarios have long been constrained by confounding factors present in contextual backgrounds. Most existing methods primarily focus on feature extraction and recognition of the target itself, often overlooking potential biases introduced by contextual interference. In this study, we innovatively incorporate the backdoor adjustment method from causal intervention to address this fundamental limitation. This approach enables the systematic removal of confounding effects arising from contextual co-occurrences at the feature level, thereby mitigating the challenges faced by traditional detectors in complex environmental conditions. Our work demonstrates that the deep integration of causal reasoning with target detection provides a robust technical framework for enhancing model reliability and establishes a methodological foundation for advancing the field toward more robust and interpretable detection systems.

3. Experiments

3.1. Dataset

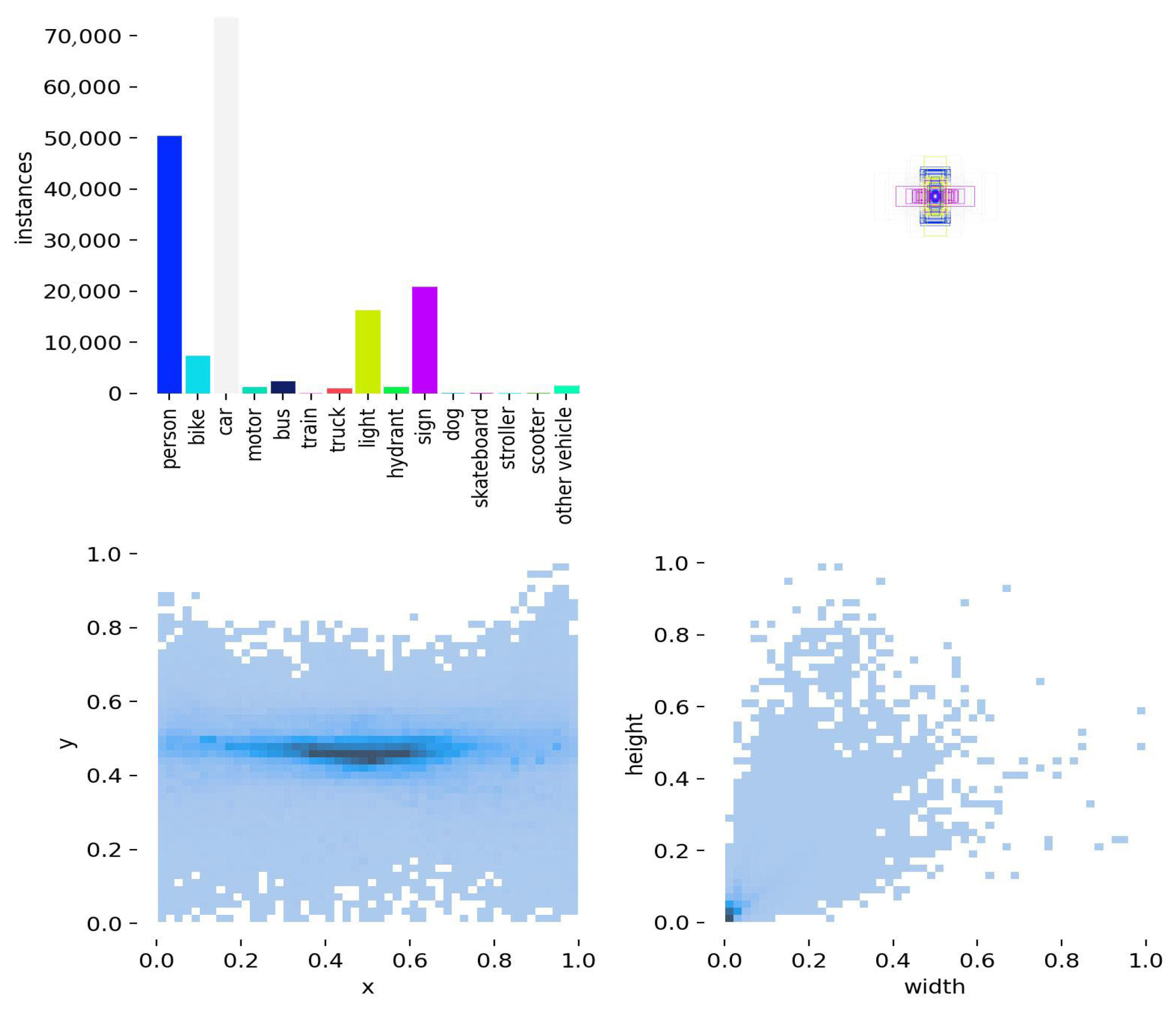

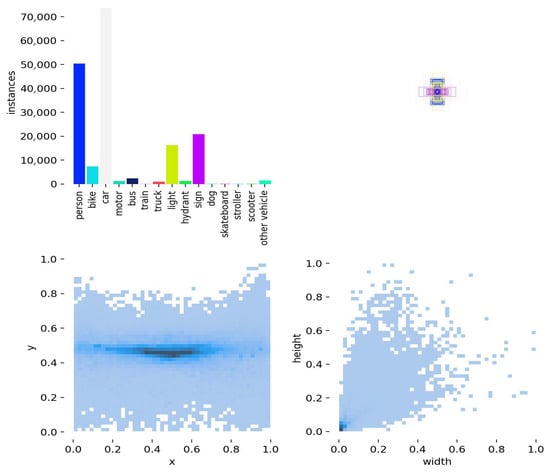

This study uses the FLIR_ADASv2 dataset, which is a publicly available infrared road small target detection benchmark released in January 2022. The dataset comprises 26,442 finely annotated images, with approximately 520,000 bounding boxes spanning 15 object categories, making it a valuable resource for infrared small target detection. Following the original split, 10,742 images are allocated for training, and 1144 images are designated for validation. To ensure data quality and annotation consistency, we performed a cleaning operation on the original dataset, removing images that did not conform to the MS COCO format. After this process, the training and validation sets contained 10,478 and 1128 images, respectively, corresponding to a retention rate of over 97%, thus providing a reliable data foundation for subsequent experiments. The detailed category distribution is presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

FLIR_ADASv2 dataset category distribution diagram.

As shown in Figure 7, the upper bar chart illustrates the distribution of instances by category within the dataset. Notably, the “person” category contains a significantly higher number of instances compared to other categories, indicating the presence of class imbalances. The thermal map on the lower left depicts the spatial distribution of targets along the x and y coordinates, revealing that targets are primarily concentrated in the central region of the images. The scatter plot on the lower right represents the relationship between target width and height, demonstrating that small targets exhibit a degree of clustering in size. Overall, the dataset exhibits three key characteristics: class imbalance, spatial concentration, and aggregation of small target sizes. These features provide an important data foundation for the design and optimization of subsequent small target detection algorithms.

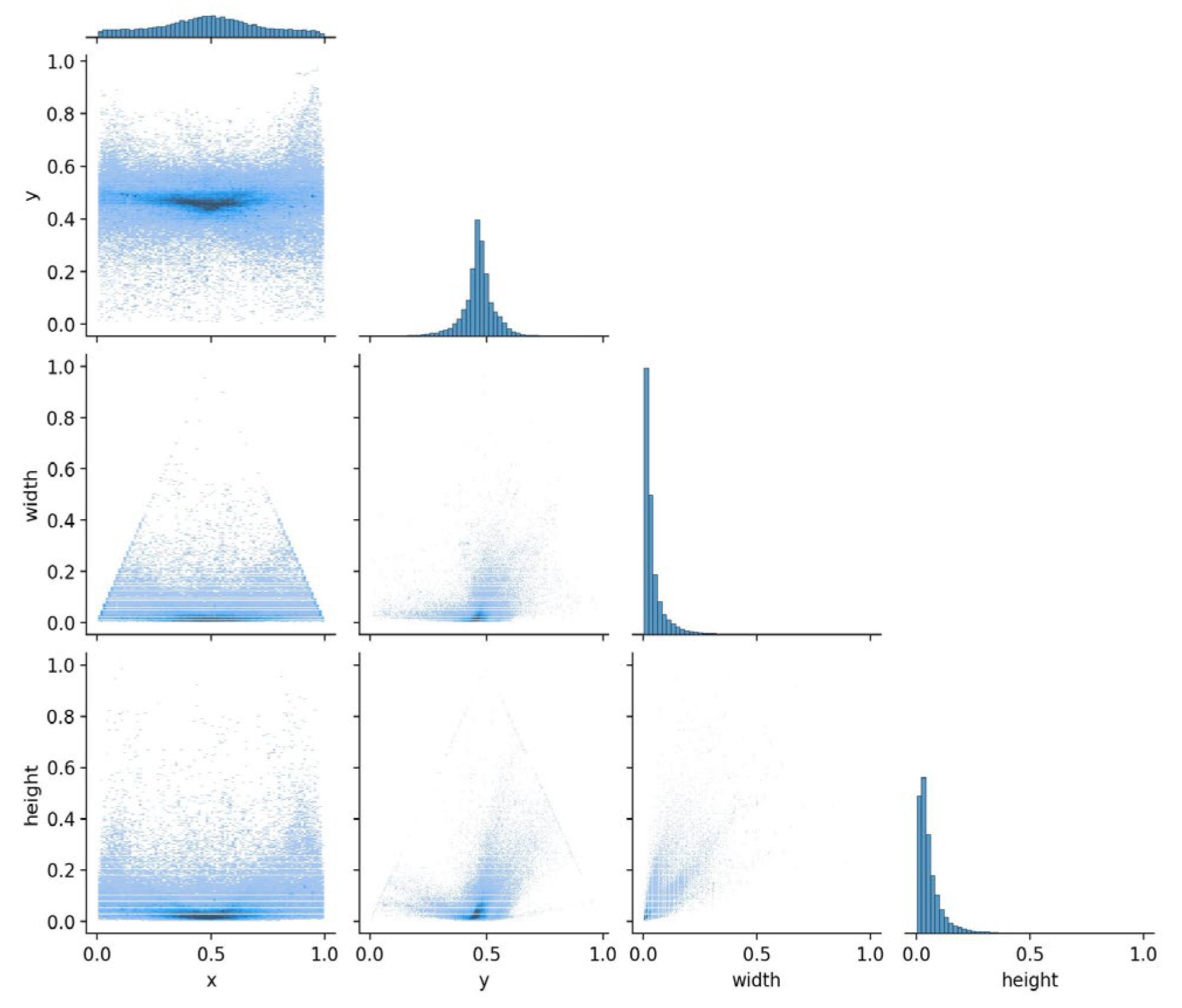

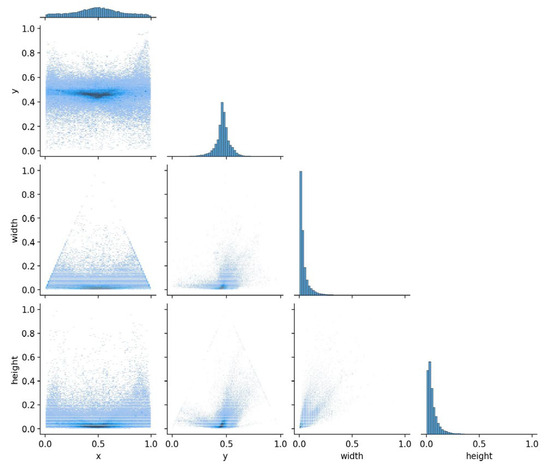

The joint visualization presented in Figure 8 further illustrates the four-dimensional distribution characteristics of targets in the FLIR_ADASv2 dataset, encompassing target center coordinates (x,y), width, and height. The histograms along the diagonal depict the marginal distribution of each variable: the x and y coordinates are approximately uniformly distributed, indicating that targets exhibit broad spatial coverage across the image plane, whereas the width and height distributions are clearly right-skewed, confirming the predominance of small-sized targets in the dataset. Scatter plots at the off-diagonal positions reveal patterns of correlation between variables. The scatter of x and y coordinates is concentrated in the central region of the images, consistent with observations from Figure 7. In contrast, the relationships between width and x, y as well as between height and x, y do not exhibit any obvious patterns, indicating no significant dependence between target size and spatial location. Notably, width and height display a positive correlation, consistent with the inherent aspect ratio characteristics of targets in real-world scenes.

Figure 8.

Joint visualization diagram of target dimension distribution of FLIR_ADASv2 dataset.

3.2. Evaluation Metric

Model performance is evaluated using the mean Average Precision (mAP) metrics, specifically mAP@50 and mAP@50:95. mAP@50 serves as a fundamental metric in object detection, representing detection accuracy at an Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5. Its value directly reflects the model’s performance under conventional matching criteria. mAP@50:95 is computed as the average of mAP values across IoU thresholds ranging from 0.5 to 0.95 with a step size of 0.05. This metric provides a comprehensive assessment of the model’s overall performance under varying localization accuracy requirements and serves as a key indicator of detection robustness.

mAP is calculated as:

where is the number of samples the model correctly predicts as positive; is the number of samples the model incorrectly predicts as positive; is the number of samples the model incorrectly predicts as negative; is the accuracy rate; is the recall rate; is the average precision value calculated for a single class in the dataset at a particular IoU threshold; C is the total number of classes in the dataset; is the arithmetic mean of the average precision values for all classes in the dataset at the same particular IoU threshold.

3.3. Experimental Environment and Parameter Setting

The experiments are conducted using the PyTorch 2.3 deep learning framework and Python 3.11 environment, with CUDA 12.1 and cuDNN 8.9.7 for accelerated computation. All code is executed on a Windows 11 server equipped with an Intel Core i9-13900K processor and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 graphics card. The YOLO target detection Ultralytics architecture is employed as the benchmark in the experiments. All models are trained for 300 epochs under identical training configurations to ensure fairness in comparison. The specific configuration is as follows: batch size is set to 32, and input images are uniformly scaled to 640 × 640 pixels. The optimizer is stochastic gradient descent (SGD) with key parameters set as: initial learning rate of 0.01, momentum coefficient of 0.937, and weight decay coefficient of 0.0005.

During training, a causal data augmentation strategy, SCG [16], is adopted to enhance the model’s robustness against feature bias. The core idea of this strategy is to introduce random fluctuations of non-causal features into the training data, simulating their variations in real-world scenarios. This encourages the model to reduce reliance on such unstable associations while strengthening its learning of the inherent causal features of the target. As part of the causal debiasing framework, this strategy contributes to robust detection in complex environments.

The overall loss function of the model consists of four components: bounding box regression loss, classification loss, target confidence loss, and distribution focus loss, with weight coefficients set to 7.5, 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5, respectively. The consistent training configuration described above provides a reliable foundation for performance comparisons across different models.

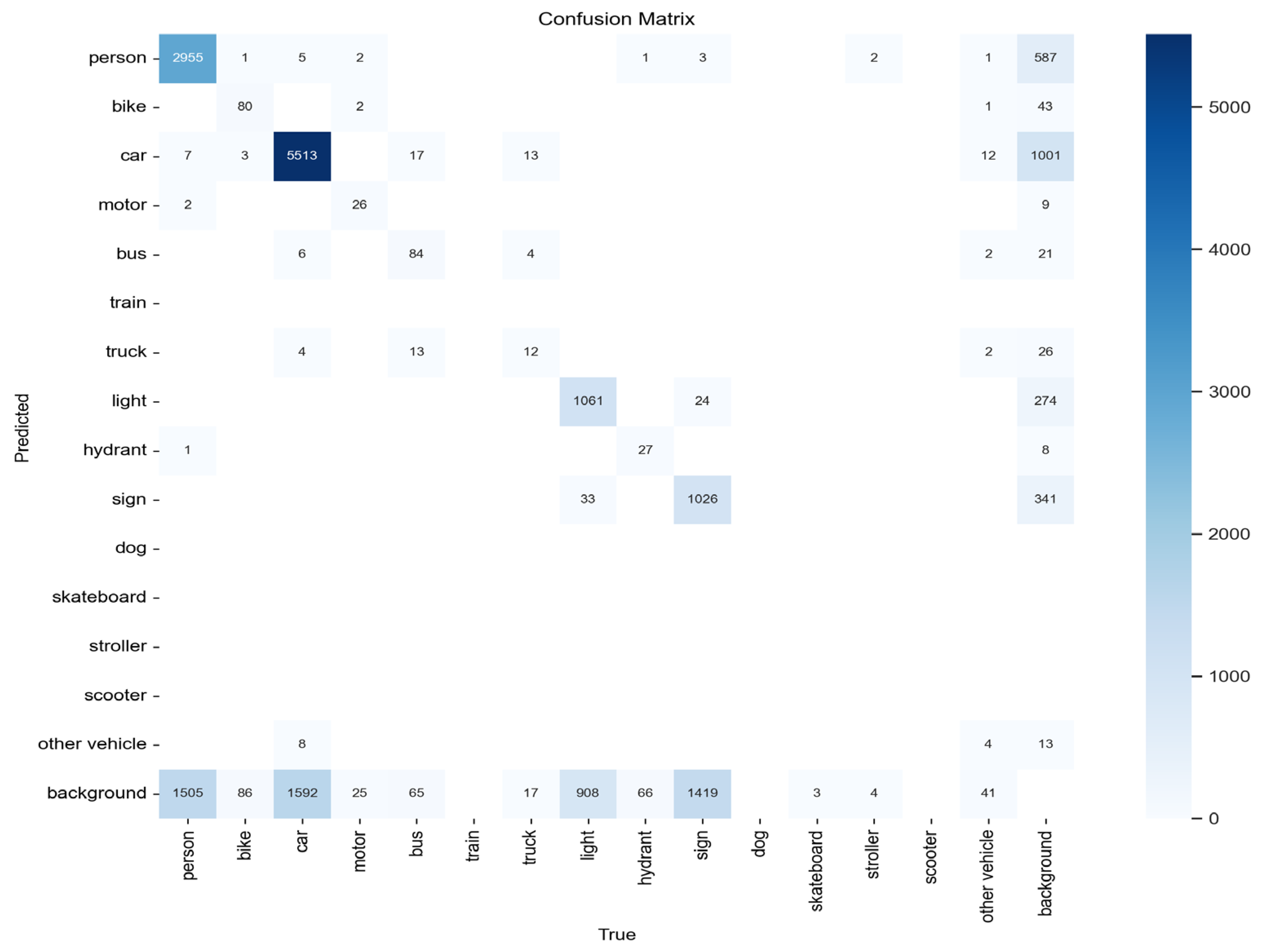

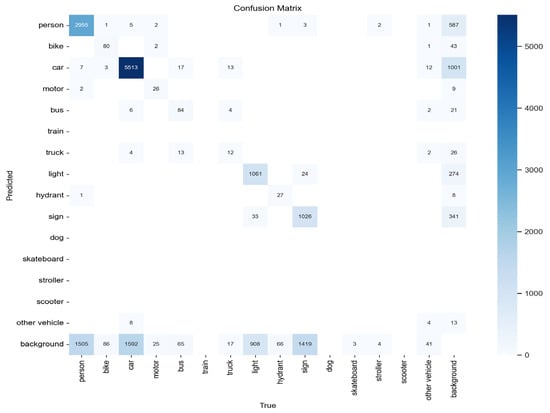

3.4. Confusion Matrix Plot Results Analysis

The confusion matrix presented in Figure 9 provides an intuitive overview of the model’s classification performance during the training phase. Overall, the model demonstrates strong recognition capability for common categories such as “person,” “bike,” and “car,” but exhibits poorer detection performance for small targets, including “light” and “hydrant,” as well as for low-frequency categories. Additionally, the matrix highlights two prominent issues: first, there is substantial false detection in background regions (corresponding to off-diagonal elements), indicating confusion between background and foreground objects; second, there is evident mutual misclassification among categories with similar appearance or semantics, such as “car” and “bike”.

Figure 9.

Confusion Matrix Plot.

In summary, the model’s classification performance is primarily constrained by three factors: the long-tail distribution of the data, significant foreground/background confusion, and insufficient representation learning among visually similar categories. Future optimization efforts can be pursued along three directions: reducing class imbalance through targeted data resampling or synthesis; mitigating the influence of background noise by improving label quality or designing anti-interference loss functions; and enhancing the model’s discriminative capability for easily confused classes by incorporating metric learning or more advanced feature representation mechanisms. Such improvements aim to comprehensively enhance the robustness and accuracy of the model.

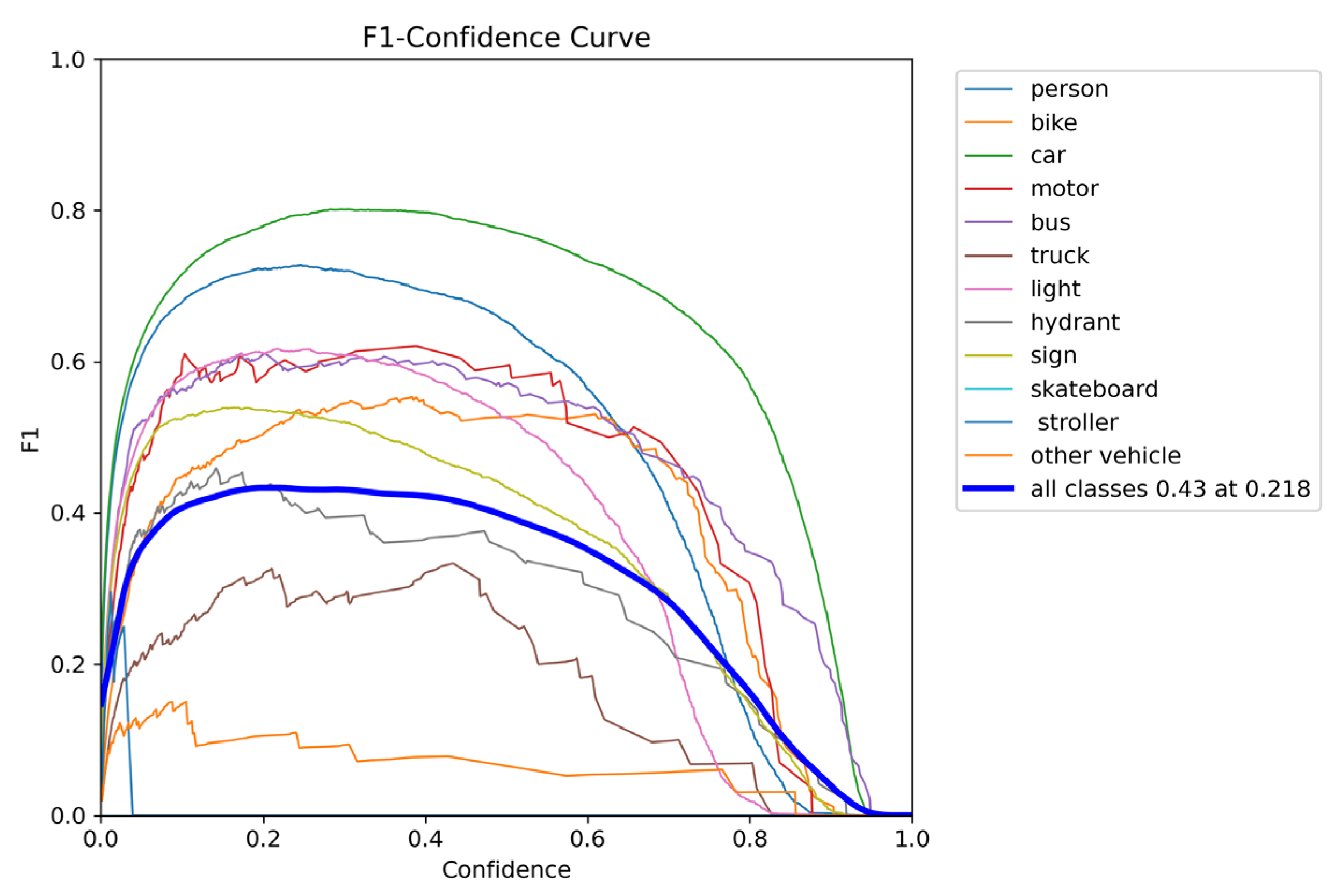

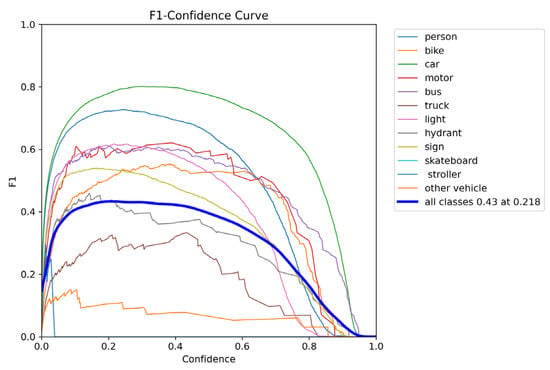

3.5. F1-Confidence Plot Results Analysis

Figure 10 illustrates the variation in F1 scores across different target categories at varying confidence thresholds during the training phase. The model maintains high F1 scores for common categories such as “person,” “bike,” and “car” over a wide range of confidence thresholds, indicating a good balance between precision and recall. In contrast, detection performance for small targets, including “light” and “hydrant,” as well as for low-frequency categories, remains weak. From an overall performance perspective, the average F1 score across all categories peaks at 0.43, corresponding to a confidence threshold of 0.218. This moderate performance is primarily due to the reduced accuracy on small-sample categories. Moreover, F1 scores decline sharply when the confidence threshold exceeds 0.6, reflecting limited reliability of the model’s high-confidence predictions.

Figure 10.

F1-Confidence Plot.

In summary, the model’s reliability is primarily constrained by three major issues: significant inter-class performance disparities, weak recognition ability for small-sample categories, and limited reliability of high-confidence predictions. To improve overall system performance, future work can focus on three directions: first, data augmentation for small-sample categories to mitigate class imbalance; second, confidence calibration to ensure that predicted probabilities more accurately reflect actual accuracy; and third, the introduction of a category-weight balancing mechanism into the loss function. These measures are expected to enhance the robustness and reliability of the model across different confidence levels.

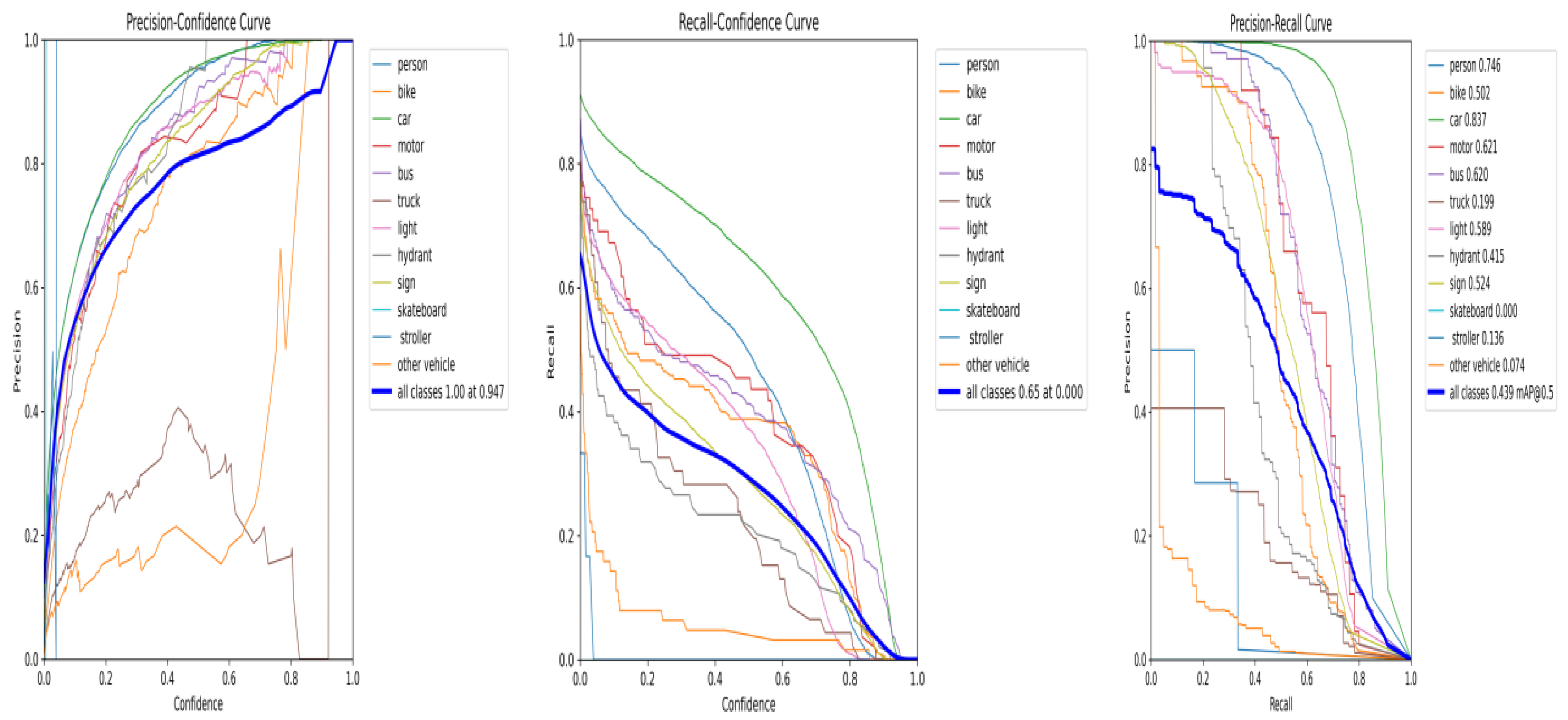

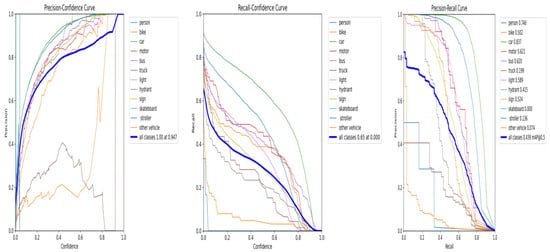

3.6. P, R and PR Curve Results Analysis

Figure 11 presents a multi-dimensional evaluation of the target detection model’s performance during the training phase, highlighting key categories (“person,” “bike,” “car”) and overall metrics through three performance curves: Precision-Confidence, Recall-Confidence, and Precision-Recall.

Figure 11.

P, R, PR Curves Plot.

- (1)

- Precision–Confidence Curve: For most categories (e.g., “car”), precision increases monotonically with confidence, consistent with expectations for a well-performing model. However, fluctuations observed in categories such as “bus” indicate inconsistencies in prediction reliability across different classes.

- (2)

- Recall–Confidence Curve: Recall generally decreases as the confidence threshold increases, in line with theoretical expectations. Notably, the recall for the “person” category declines sharply once the confidence threshold exceeds 0.6, highlighting a significant risk of missed detections for this category under high-confidence settings.

- (3)

- Precision–Recall Curve: This curve illustrates the trade-off between precise identification and comprehensive coverage. The larger area under the curve for the “car” category indicates a better balance between precision and recall. In contrast, the steep decline of the curve for the “bus” category underscores the greater difficulty the model encounters in reliably detecting this class.

Comprehensive analysis indicates substantial differences in detection performance across classes, with some categories (such as “bus”) experiencing a trade-off between precision and recall at high confidence levels, which reduces practical utility. To address this, future work can proceed along two directions: first, targeted optimization for weaker categories, such as adjusting data sampling strategies or modifying loss function weights; second, in practical deployment, confidence thresholds for individual categories can be dynamically adjusted based on task requirements emphasizing either precision or recall to optimize model performance in specific scenarios.

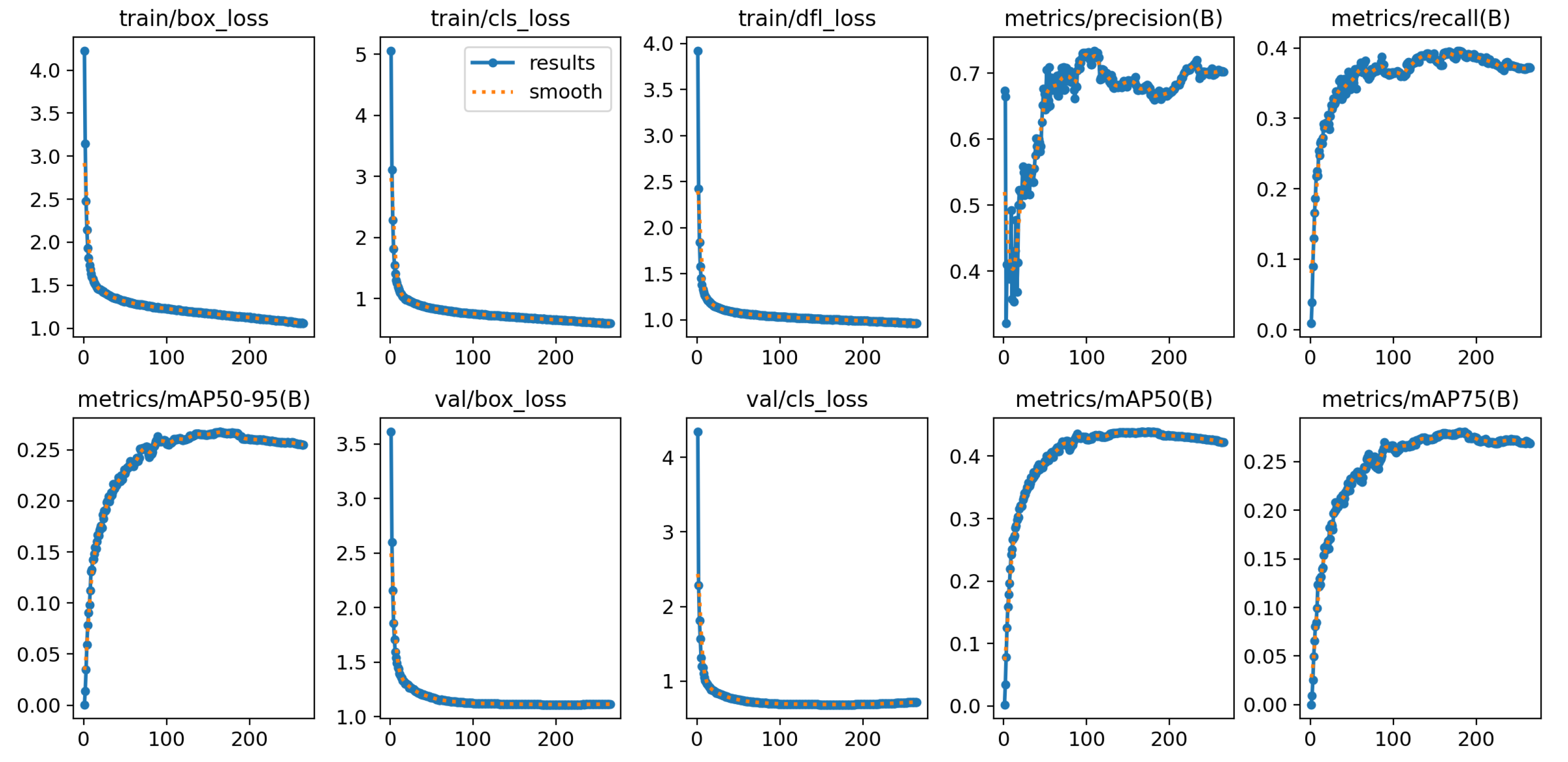

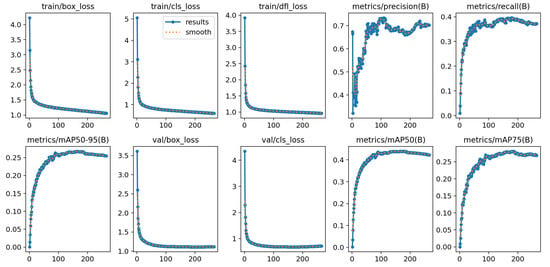

3.7. Loss Function and Evaluation Metric Curve Plot Results Analysis

As shown in Figure 12, the loss function and evaluation metric curves during training exhibit strong convergence characteristics. All loss values, including bounding box loss and classification loss, decrease rapidly during the initial iterations and subsequently plateau, indicating effective model optimization. Simultaneously, key evaluation metrics, such as accuracy, recall, mAP@50, and mAP@50:95, steadily increase over the training rounds and eventually stabilize. This demonstrates both the progressive improvement and the final stability of the model in terms of detection accuracy, recall capability, and overall localization performance. All curves converge smoothly without obvious signs of overfitting, thereby validating the effectiveness of the training process and the reliability of the model’s performance.

Figure 12.

Loss Function and Evaluation Metric Curve Plot.

3.8. Comparative Experimental Results Analysis

As summarized in Table 1, this study systematically compares 12 mainstream detection models from YOLOv3-tiny to YOLOv13n against the proposed YOLOv7-tiny-CR on the FLIR_ADASv2 dataset. The results clearly highlight the inherent trade-off among model scale, computational cost, and detection accuracy. Among all evaluated models, YOLOv7-tiny-CR exhibits the highest parameter count (13.8 M) and computational complexity (31.2 GFLOPs), while achieving the best detection performance, with mAP@50 and mAP@50:95 reaching 47.0% and 29.1%, respectively, significantly surpassing the baseline model. This outcome reflects a deliberate design choice that prioritizes high accuracy for performance-critical applications, while acknowledging the associated computational cost. In terms of inference speed, YOLOv7-tiny-CR processes an image in 1.5 ms, which, although not the fastest among the compared models, still meets real-time detection requirements.

Table 1.

Comparative experimental results of different target detection models. Parameters, FLOPs, and Inference-time are reported in Million (M), Giga (G), and milliseconds (ms), respectively.

Based on a comprehensive evaluation, YOLOv7-tiny was selected as the baseline for further enhancement in this work. The resulting YOLOv7-tiny-CR model achieves notable performance gains of 2.9% in mAP@50 and 2.7% in mAP@50:95, at the expense of a 5.4 M increase in parameters, 9.3 GFLOPs additional computational cost, and a 0.3 ms increase in inference time. These results demonstrate that the proposed framework effectively enhances detection accuracy within a performance-complexity trade-off, maintaining a balance suitable for its target applications.

3.9. Ablation Experimental Results Analysis

To evaluate the individual contributions of the proposed modules within the YOLOv7-tiny-CR model, a systematic ablation study was conducted, with configurations and results summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of ablation experiments in YOLOv7-tiny-CR model. Parameters, FLOPs, and Inference-time are reported in Million (M), Giga (G), and milliseconds (ms), respectively.

- (1)

- Baseline (YOLOv7-tiny): Serves as the reference for all comparative metrics.

- (2)

- CAM Module (YOLOv7-tiny+CAM): Incorporating the CAM module results in a noticeable increase in both parameter count and computational cost, while yielding only marginal improvements in the two mAP metrics. This outcome is expected, as the primary purpose of the CAM module is not to independently enhance performance, but to perform essential feature preprocessing that supports subsequent causal intervention.

- (3)

- CI Module (YOLOv7-tiny+CI): With a minimal parameter increase of only 0.4 M, this configuration achieves substantial performance gains mAP@50 and mAP@50:95 each improve by 2.5%. This strongly validates that the CI module effectively mitigates bias introduced by contextual confounders through backdoor adjustment, representing the most significant contributor to detection improvement.

- (4)

- Full Model (YOLOv7-tiny-CR): The integration of both CAM and CI modules achieves the highest scores for mAP@50 and mAP@50:95, demonstrating a clear synergistic advantage. This indicates that the feature decoupling enabled by the CAM module, combined with the causal intervention performed by the CI module, forms a complete debiasing pipeline, wherein their combined action results in an optimal overall bias-removal effect.

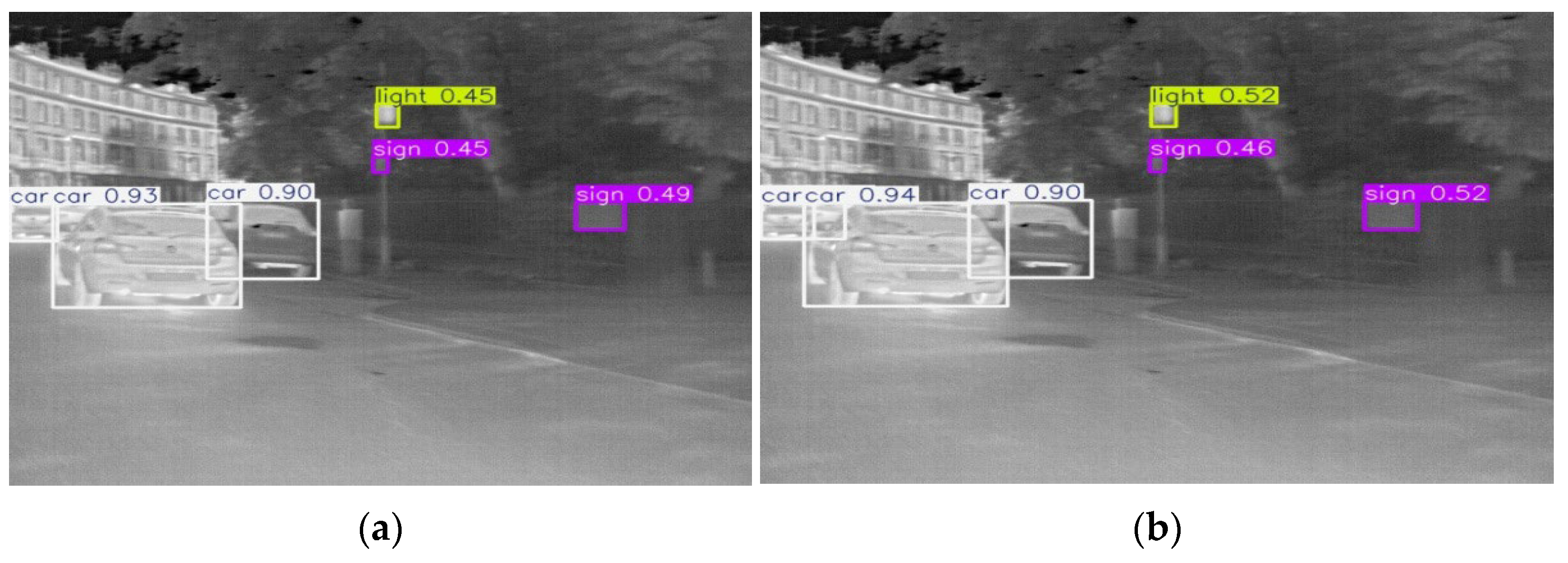

3.10. Visualization Results Analysis

A comparison of detection results between the baseline YOLOv7-tiny model and the proposed YOLOv7-tiny-CR model in an infrared road scene reveals notable differences in target recognition confidence (Figure 13). Quantitatively, YOLOv7-tiny-CR achieves confidence scores of 0.94 for the “car” category, 0.52 for “light,” and 0.46 and 0.52 for two instances of “sign.” Comparing the confidence scores from the YOLOv7-tiny model with those of the “car”, “light”, and “signs” categories, we find that the YOLOv7-tiny model consistently produces lower confidence scores. Specifically, the “car” model achieves a confidence score of 0.93, while the “light” model reaches 0.45, and the “signs” model demonstrates a higher confidence score of 0.45 and 0.49. The systematic higher confidence scores across all categories suggest that YOLOv7-tiny-CR outperforms infrared scenarios, thereby enhancing the reliability and robustness of its detection results.

Figure 13.

Visualization Plot of YOLOv7-tiny and YOLOv7-tiny-CR model detection results. (a) YOLOv7-tiny; (b) YOLOv7-tiny-CR.

4. Conclusions

Based on causal reasoning, this study proposes the YOLOv7-tiny-CR model to address the problem of feature bias caused by contextual confounders in infrared small target detection. Specifically, the structural causal model constructed in this work explicitly distinguishes between causal and non-causal features that influence detection performance. Building on this foundation, the CAM module and the CI module collaboratively debias features at two levels: feature refocusing and bias suppression. This design ensures that model decisions are primarily guided by robust, causally relevant features, fundamentally enhancing both robustness and detection accuracy in complex and variable infrared scenarios. Experimental results on the FLIR_ADASv2 dataset demonstrate that the proposed model improves mAP@50 and mAP@50:95 by 2.9% and 2.7%, respectively, significantly outperforming the baseline. These findings confirm the model’s effectiveness in reducing feature bias and improving detection performance for small infrared targets.

At the same time, this study acknowledges certain limitations and outlines directions for future research. First, although the current framework enhances performance, the addition of computational modules increases both model parameters and computational overhead. A priority for future work is therefore the development of lightweight designs, such as model pruning or knowledge distillation, to substantially improve inference speed while maintaining performance advantages, thereby enhancing deployment feasibility on embedded systems. Second, more extensive generalization tests across diverse infrared datasets will be conducted to further validate the framework’s universality and robustness.

While further optimization remains possible, this study provides a reliable and causally discriminative solution for infrared target detection in applications such as military reconnaissance and intelligent driving. Moreover, it offers a methodological framework for effectively integrating causal reasoning into low-level vision tasks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W.; methodology, H.W.; software, H.W.; validation, H.W.; formal analysis, H.W.; investigation, H.W.; resources, L.S.; data curation, H.W.; writing—original draft preparation, H.W.; writing—review and editing, L.S.; visualization, H.W.; supervision, L.S.; project administration, L.S.; funding acquisition, L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pearl, J. Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; ISBN 978-1-139-64936-0. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, W.; Feng, F.; He, X.; Li, Y. Causal Inference in Recommender Systems: A Survey and Future Directions. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2024, 42, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebane, G.; Pearl, J. The Recovery of Causal Poly-Trees from Statistical Data. In Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence, Seattle, WA, USA, 10–12 July 1987; AUAI Press: Arlington, VA, USA, 1987; pp. 222–228. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, D.C.; Walker, I.; Glocker, B. Causality Matters in Medical Imaging. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Jiang, M.; Li, M.; Meng, B.; Ren, J.; Zhao, S.; Bai, R.; Yang, Y. Causal Intervention for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 33rd International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 1–3 November 2021; pp. 770–774. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Chen, D.; Bao, C.; Luo, Y. Causal Attention-Based Lightweight and Efficient Cervical Cancer Cell Detection Model. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine, Istanbul, Turkiye, 5–8 December 2023; pp. 1104–1111. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, R.; Du, Z.; Ye, Q. A Ship Detection Method in Infrared Remote Sensing Images Based on Image Generation and Causal Inference. Electronics 2024, 13, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Shin, S.; Yu, Y.; Kim, H.G.; Ro, Y.M. Causal Mode Multiplexer: A Novel Framework for Unbiased Mul tispectral Pedestrian Detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 26774–26783. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, F.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ye, L.; Tang, S.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, J. Improving Weakly Supervised Object Localization via Causal Intervention. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Virtual Event, 20–24 October 2021; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 3321–3329. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.; Guo, Y.; Ding, G.; Han, J. ACNet: Strengthening the Kernel Skeletons for Powerful CNN via Asymmet ric Convolution Blocks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1911–1920. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Liu, X.; Hao, C.; Fan, B.; Tian, J. Unbiased Faster R-CNN for Single-Source Domain Generalized Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 28838–28847. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Shao, Z.; Teng, Y.; Hoffmann, N. NAM: Normalization-Based Attention Module. In Proceedings of the 35th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023; OpenReview: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gkioxari, G.; Johnson, J.; Malik, J. Mesh R-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 9784–9794. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Paz, D.; Nishihara, R.; Chintala, S.; Scholkopf, B.; Bottou, L. Discovering Causal Signals in Images. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Huang, J.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Q. Visual Commonsense R-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10757–10767. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Qin, L.; Chen, W.; Pu, S.; Zhang, L. Multi-View Adversarial Discriminator: Mine the Non-Causal Factors for Object Detection in Unseen Domains. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 8103–8112. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLOv3: An Incremental Improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.-Y.; Liao, H.-Y. YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, B.; Li, L.; Li, L.; Geng, Y.; Cheng, M.; Xiaoming, X.; Chu, X.; Wei, X. YOLOv6: A Single-Stage Object Detection Framework for Industrial Applications. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024; OpenReview: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable Bag-of-Freebies Sets New State-of-the-Art for Real-Time Object Detectors. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Yeh, I.-H.; Mark Liao, H.-Y. YOLOv9: Learning What You Want to Learn Using Programmable Gradient Information. In Proceedings of the 18th European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. YOLOv10: Real-Time End-to-End Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–15 December 2024; Curran Associates: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 107984–108011. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, D.; Lu, R.; Hu, B.; Yin, J.; Shen, S.; Xu, T.; Lang, X. YOLO-MIF: Improved YOLOv8 with Multi-Information Fusion for Object Detection in Gray-Scale Images. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 62, 102709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Ye, Q.; Doermann, D. YOLOv12: Attention-Centric Real-Time Object Detectors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502:12524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Li, S.; Wu, Y.; Hu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, X.; Ding, G.; Du, S.; Wu, Z.; Gao, Y. YOLOv13: Real-Time Object Detection with Hypergraph-Enhanced Adaptive Visual Perception. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.17733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).