Abstract

Pulsed electric field (PEF) technology represents a promising non-thermal method for enhancing the extraction of bioactive compounds from plant matrices. This study investigated the influence of PEF treatment on the bioactive compounds composition of aqueous extracts obtained after processing blackcurrant, redcurrant, chokeberry, raspberry, and blackberry seeds. The seeds were treated at 8 kV or 10 kV electrode voltage, and 50 kJ/kg energy input, and the resulting extracts were analyzed for total polyphenol content (TPC), antioxidant capacity (ABTS and DPPH assays), anthocyanin composition (HPLC-DAD), and color parameters (L*, a*, b*). The PEF treatment significantly enhanced the release of polyphenols, anthocyanins, and antioxidant compounds, particularly in chokeberry, raspberry, and blackberry seed extracts. Extracts obtained after PEF treatment exhibited higher TPC, in a range between 0.57 and 3.00 mg GAE/g, and higher radical scavenging activity in a range 2.33–35.07 µmol TE/g in ABTS assay and 1.07–12.27 µmol TE/g in DPPH assay. Also, more intense red coloration was determined, confirming that electroporation facilitated pigment and phenolic migration into the aqueous phase. These findings demonstrate that PEF is an efficient and solvent-free intensification technique for the valorization of berry by-products, generating aqueous fractions rich in natural antioxidants and colorants that support circular and sustainable fruit-processing practices.

1. Introduction

Pulsed electric field (PEF) pretreatment is widely applied as a method to improve the extraction rate of compounds from plant material. PEF utilizes short electric pulses that lead to the disintegration of a plant’s cell membranes, called electroporation. Also, PEF can cause the leak of a cell’s fluids. These phenomena contribute to improving the extraction efficiency of biocompounds present in plant cells [1]. Applications of PEF may reduce the time needed to extract compounds and also allow for replacing the organic solvents with environmentally safe extractants, for instance, water [2]. Using water as a solvent and shortening the extraction time have advantages for the reduction of financial outlays [3].

The Revised Waste Framework Directive of the European Union requires the Member States to reduce by-products of the food industry by 10% by 2030. In order to fulfill those requirements, new perspectives on waste management are being sought [4]. Berry fruit pomaces, the main by-product of the fruit industry (25–30%), contain mostly seeds, stems or skins [5]. Berry fruit seeds, as fruit industry by-products, can be used to obtain oil. However, the oil content in those seeds is relatively low. To enhance the extractability of oil, PEF treatment can be conducted. The application of PEF occurs in a special chamber, while the material must be put in water in order to achieve the required conductivity. The seeds can then be used to extract or press the oil. However, in the water used in the PEF pretreatment process, there are dissolved compounds extracted during the aforementioned procedure. PEF was previously used as a method to improve the extractability of oils from the seeds in some studies. Guderjan et al. [6] used PEF treatment to improve the oil extraction yield and oil pressing yield of rapeseed. PEF also led to higher content of tocopherols, polyphenols, total antioxidants, and phytosterols in rapeseed oils. Bakhshabadi et al. [7] used PEF before the cold pressing of black cumin oil. Microscope images proved that PEF facilitated the oil extraction process through cell damage in the seeds. Applied pretreatment also resulted in improved oxidative stability of black cumin oil. PEF was also used as a pretreatment in the extraction of phenolic compounds. It was observed that PEF application caused increased total anthocyanin content and total polyphenolic content in wines [8], extracts obtained from mango peels [9], and blueberry by-products [10]. In our previous findings, PEF treatment improved the oxidative stability of raspberry seed oil extracted in a solid/liquid extraction procedure, which could be attributed to the enhanced bioactive compound extraction during PEF application [11]. However, there is limited data concerning the influence of PEF pretreatment conditions on the occurrence and composition of bioactive compounds present in the water used in the PEF chamber to treat seeds used in the oil extraction process.

The aim of the following study was to assess the composition of water left after PEF treatment of blackcurrant, redcurrant, chokeberry, raspberry and blackberry seeds which were subjected to oil extraction. In order to investigate the polyphenolic fraction, total polyphenol content (TPC) and antioxidant capacity against DPPH and ABTS were measured in spectrophotometric assessments. Anthocyanin content and phenolic acids content were determined using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Also, colorimetric analysis of aqueous extracts was carried out in order to provide an additional indicator of pigment content.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

The seeds of blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum var. Ruben), redcurrant (Ribes rubrum var. Jonkheer van Tets), raspberry (Rubus idaeus var. Polana), chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa var. Nero) and blackberry (Rubus fruticosus var. Brzezina) were separated from the dried pomace left after juice pressing.

2.2. Pulsed Electric Field Treatment

Whole seeds (2 g) were mixed with tap water (8 g) and processed using a PEFPilot™ Dual System (Elea Technology GmbH, Quakenbrück, Germany). The PEF treatments were applied at electrode voltages of 8 kV (PEF1) or 10 kV (PEF2), with a pulse width of 7 µs and a frequency of 20 Hz, delivering a total specific energy input of 50 kJ/kg. Following PEF exposure, the seed–water mixtures were transferred to screw-cap plastic tubes and left to stand for 2 h. The seeds were then filtered and subsequently used for oil extraction, as described in a previous publication [11]. Control samples were prepared according to the methodology presented above, but without the use of PEF.

2.3. Total Polyphenol Content

The Folin–Ciocalteu method described by Gao et al. [12] was performed to determine the total phenolic content (TPC). Diluted extract (0.2 mL), after mixing with 0.4 mL of the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, 4 mL of distilled water, and 2 mL of a 15% sodium carbonate solution, was vortexed. The mixture was then kept in the dark for 60 min. A UV-VIS Jenway 6305 spectrophotometer (Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL, USA) was applied to measure the absorbance at 765 nm. Gallic acid solutions ranging from 50 to 250 mg/L were used to prepare a standard curve. Obtained results (TPC) were presented as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per gram of dried sample.

2.4. Antioxidant Capacity—ABTS Method

ABTS•+ radical cation method described by Re et al. [13] was applied to evaluate the antioxidant capacity. Namely, 40 μL of the diluted extract was vortexed briefly with 4 mL of the ABTS working solution. The mixture was kept in the dark for 8 min to react. The absorbance at 765 nm was measured by a UV—VIS Jenway 6305 spectrophotometer (Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL, USA). Trolox solutions ranging from 0 to 1125 μmol/L were used to obtain a calibration curve. Antioxidant capacity was presented as μmol Trolox equivalents (TE) per gram of dried sample.

2.5. Antioxidant Capacity—DPPH Method

According to the modified method described by Brand-Williams et al. [14], a solution of DPPH (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) (0.6 mM) was left in the dark at 4 °C for approximately 16 h. In order to achieve an absorbance in the range of 0.680–0.720 at a wavelength of 515 nm, the solution was appropriately diluted. Test tubes containing 100 μL of the sample and 4 mL of the DPPH radical solution were vortexed. The absorbance was measured against methanol as a blank at a wavelength of 515 nm after a 30 min incubation of samples in the dark. Calibration curve obtained using Trolox standard solutions in the concentration range from 0 to 1125 μmol/L was the basis to present the results as mmol Trolox equivalent (TE) per gram of dried sample.

2.6. Color Characteristics

The L*, a*, and b* values representing the color characteristics were measured by a colorimeter (Konica Minolta, Osaka, Japan) operating in transmittance mode. Samples were placed in a glass cuvette with a path length of 10 mm. Measurements were performed under a D65 standard illuminant with a 10° observer angle and a port diameter of 25.4 mm.

2.7. Anthocyanin Profile

Anthocyanin levels were determined using an HPLC system (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a DAD detector and a Luna 5 μm C18 (2) analytical column (250 mm × 4.6 mm) with a matching precolumn (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). The analysis was performed according to the method previously reported in [15]. Separation was achieved under isocratic conditions at a flow rate of 1 mL/min, employing a mobile phase composed of water, acetonitrile, and formic acid in a ratio of 830:70:100 (v/v/v). Detection was carried out at 520 nm. Quantification was performed using external calibration with cyanidin-3-glucoside. Total anthocyanin content (TAC) was expressed as the sum of the individual anthocyanins, calculated using LabSolutions software (v. 5.106, Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The assays were analyzed in statistical analysis using Statistica software (v. 13.3, TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). The ANOVA and post hoc Tukey’s tests were applied in order to determine significant differences among the samples with p < 0.05. Also, principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) were performed.

3. Results

3.1. Total Polyphenol Content

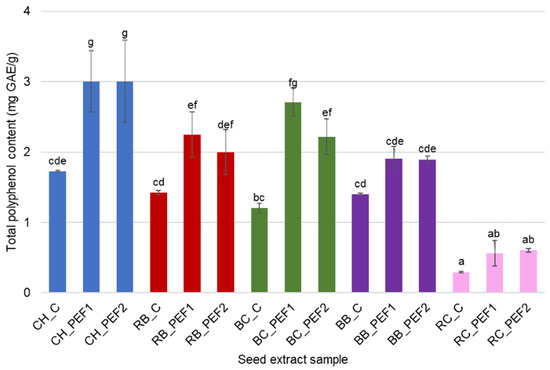

The total polyphenol content (TPC) of aqueous extracts obtained after PEF treatment of berry seeds is presented in Figure 1. In all tested species, the application of pulsed electric field significantly (p < 0.05) enhanced the TPC compared with untreated controls. The highest polyphenol levels were recorded for chokeberry (CH) seed extracts, where TPC increased from 1.73 mg GAE/g in the control to 3.00 ± 0.43 mg GAE/g and 3.00 ± 0.59 mg GAE/g after both PEF1 and PEF2 treatments, respectively. A similar trend, though less pronounced, was observed for raspberry (RB) and blackberry (BB) seed extracts. In contrast, redcurrant (RC) seed extracts exhibited the lowest TPC values, with only moderate increases following PEF application: 0.29 ± 0.01 mg GAE/g, 0.57 ± 0.18 mg GAE/g and 0.61 ± 0.03 mg GAE/g for control, PEF1 and PEF2 treatments, respectively.

Figure 1.

Total polyphenol content (mg GAE/g) of berry seed aqueous extract obtained during PEF treatment and in control (C) conditions. Different letters in the superscript indicate significant differences in results measured in triplicate at p < 0.05.

These differences reflect the natural variability in phenolic composition among berry species and the efficiency of PEF-induced cell disruption. The results show that PEF pretreatment enhances the release of water-soluble phenolic compounds from seed matrices, consistent with previous studies reporting improved extraction yields in electroporated plant tissues [16,17].

3.2. Antioxidant Capacity

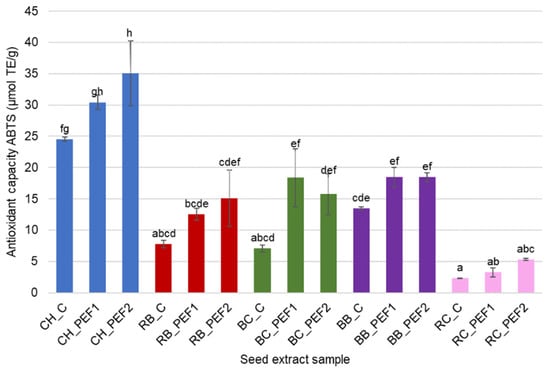

The antioxidant capacity of aqueous extracts obtained from berry seeds subjected to PEF treatment was evaluated using the ABTS and DPPH radical scavenging assays (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Both tests revealed that pulsed electric field treatment significantly (p < 0.05) enhanced the antioxidant capacity of most samples compared to their untreated controls, although the extent of improvement varied among berry species. In general, the ABTS assay indicated higher radical scavenging activity in extracts from CH, RB and BB seeds after PEF application. The strongest effect was observed in chokeberry extracts, where antioxidant capacity nearly doubled compared with the control, reflecting the high release of hydrophilic phenolic compounds. RB and BB extracts obtained from PEF treatment also exhibited increases in antioxidant capacity. RC and BC extracts, however, displayed relatively low ABTS values overall, and the influence of PEF treatment was less noticeable, which may be attributed to their lower inherent phenolic content or less efficient cell disruption under the applied electric field strength.

Figure 2.

Antioxidant capacity of berry seed aqueous extracts against ABTS. Different letters in the superscript indicate significant differences in results measured in triplicate at p < 0.05.

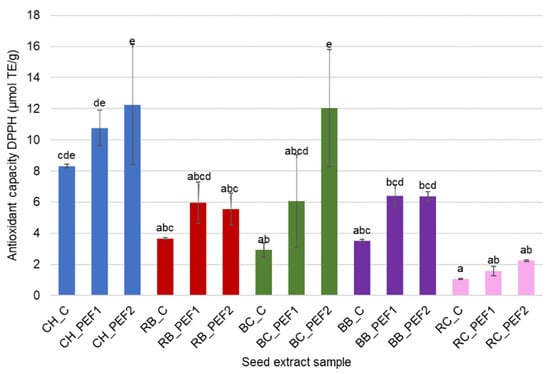

Figure 3.

Antioxidant capacity of berry seed aqueous extracts against DPPH. Different letters in the superscript indicate significant differences in results measured in triplicate at p < 0.05.

The DPPH assay results followed a similar trend, showing that PEF treatment enhanced the free radical scavenging properties of the aqueous extracts. As in the ABTS test, the highest DPPH values were observed for CH and RB seed extracts, while only minor differences were recorded for RC and BC. The observed enhancement of antioxidant capacity in PEF-treated samples supports the hypothesis that electroporation facilitates cell membrane disruption, enabling the migration of phenolic antioxidants into the surrounding water [18]. Thus, the application of PEF pretreatment to berry seeds generates aqueous by-product extracts rich in bioactive, antioxidant compounds.

3.3. Color Measurement

Color parameters (L*, a*, b*) of aqueous extracts obtained after PEF treatment of berry fruit seeds are presented in Table 1. The color characteristics varied significantly (p < 0.05) depending on both the berry species and the treatment applied. Generally, the PEF treatment led to a noticeable decrease in lightness (L*) and an increase in chromatic coordinates (a*, b*), indicating a darker and more intensely colored extract compared to the control samples.

Table 1.

The results of color measurements (L*, a*, b*) of aqueous berry seed extracts.

Among all tested materials, RC extracts exhibited the highest lightness values, exceeding 94 L*, which corresponded to a pale, nearly colorless solution. PEF treatment of RC seeds caused only a slight reduction in L* and minor increases in a* and b*, suggesting limited pigment release from this seed type. In contrast, CH and BB samples showed a substantial decrease in L* after PEF treatment. For CH extracts, lightness was reduced from 84.52 (control) to 60.05 after PEF1, accompanied by a rise in a* from 31.29 to 45.31, reflecting an intensification of red hue. Similarly, BB samples treated with PEF displayed markedly lower L* and significantly higher a* values compared to the control, showing that PEF promoted the extraction of colored compounds into the aqueous medium. A comparable pattern was observed for RB extracts, where PEF treatment reduced L* from 77.48 to approximately 54 and increased both a* and b* values, producing a more vivid red-orange tone. BC extracts exhibited intermediate changes- L* decreased from 87.43 to 75.29 (PEF1), while a* values increased, indicating enhanced color saturation consistent with the release of anthocyanins and other phenolics from the seed tissues.

The observed color modifications correlate with the anthocyanin data, where PEF-treated samples, particularly from CH, RB and BB seeds, showed higher total anthocyanin content. More intense red coloration (higher a*) and lower lightness (L*) of those extracts present that PEF treatment facilitated pigment diffusion into water during the electroporation process.

3.4. Anthocyanin Profile

The composition and total content of anthocyanins (TAC) identified in aqueous extracts obtained after PEF treatment of berry seeds are presented in Table 2. The anthocyanin profiles varied markedly among the studied species, reflecting their characteristic pigment patterns. In general, the application of pulsed electric field significantly (p < 0.05) enhanced the total anthocyanin concentration in the aqueous phase, although the magnitude of this effect depended on the type of berry seed. Among the tested materials, RB extracts exhibited the highest total anthocyanin content, reaching approximately 370 mg/100 g across all treatments. The dominant pigments in RB extracts were cyanidin-3-sophoroside, cyanidin-3-glucosylrutinoside, and cyanidin-3-rutinoside, which are typical anthocyanins of Rubus species [19,20]. The PEF treatment did not significantly alter the qualitative composition of these compounds but maintained high quantitative recovery, suggesting that the extraction process was efficient even under control conditions. RC extracts also contained substantial amounts of cyanidin-3-glucosylrutinoside and cyanidin-3-rutinoside, with total anthocyanin contents around 372–373 mg/100 g. Similarly to RB, PEF treatment of RC seeds caused only minor variations in anthocyanin yield, indicating that RC seed pigments are water-extractable even without pulsed electric field pretreatment. In contrast, CH, BC and BB extracts exhibited a pronounced increase in TAC following PEF treatment. In CH, TAC increased from 33.4 mg/100 g in the control to approximately 70 mg/100 g after both PEF1 and PEF2 treatments. The dominant anthocyanins were cyanidin-3-galactoside and cyanidin-3-arabinoside, whose concentrations more than doubled under PEF conditions. This suggests that electroporation effectively disrupted the seed tissues, facilitating anthocyanin diffusion into the aqueous medium. BC extracts contained mainly delphinidin-3-glucoside, delphinidin-3-rutinoside, and cyanidin-3-rutinoside, typical for Ribes nigrum [21].

Table 2.

The anthocyanin content in tested berry seed extracts (mg/100 g); TAC-total anthocyanin content.

The higher anthocyanin levels in PEF-treated samples correspond well with the observed color changes (decrease in L*, increase in a*), as both phenomena are linked to the migration of colored compounds into the aqueous phase. The improvement in anthocyanin extraction is attributable to membrane electroporation and local cell wall disruption caused by electric pulses, which increase mass transfer and pigment solubilization [22]. Overall, the results indicate that PEF treatment promotes the release of water-soluble anthocyanins from berry seeds, particularly in CH, BC and BB, thereby enhancing the functional value of the aqueous fraction obtained from berry seeds.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

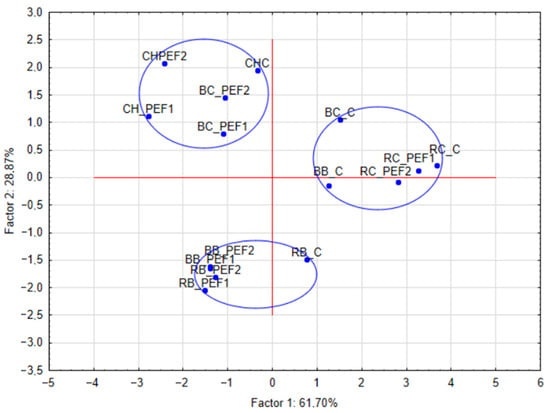

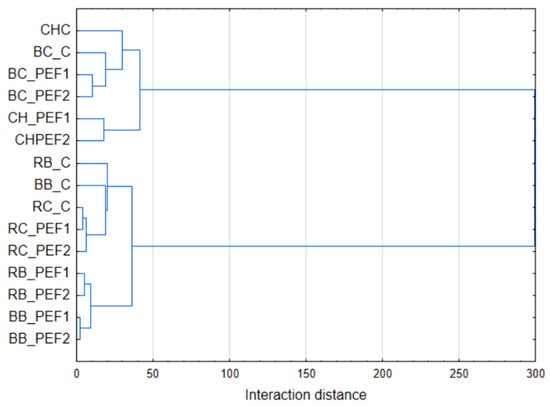

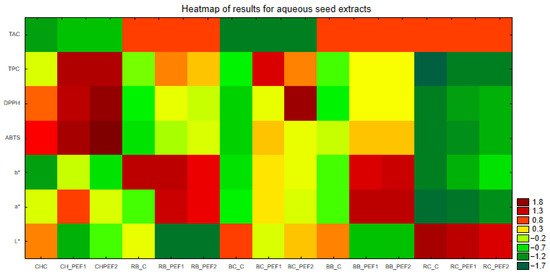

The results were subjected to a principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA). The obtained graphs are shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5. The results of TPC, antioxidant capacity against ABTS and DPPH, color measurements L*, a*, b* and TAC were analyzed. Based on that, PCA shows three groups of results. In the case of BB and BC, control samples were not close to the PEF-treated ones, in other tested seed extract samples, controls were still within a short distance to the extracts obtained in the PEF procedure. Also, a heatmap of standardized results was created in order to provide a comparison of the obtained results (Figure 6).

Figure 4.

Principal component analysis results of aqueous extracts from berry seeds (factors: TPC, ABTS, DPPH, L*, a*, b*, TAC).

Figure 5.

Hierarchical cluster analysis of results for factors: TPC, ABTS, DPPH, L*, a*, b*, TAC of berry seed aqueous extracts.

Figure 6.

Heatmap of standardized results (TPC, ABTS, DPPH, L*, a*, b*, TAC) of berry seed aqueous extracts.

4. Discussion

The present results show that pulsed electric field treatment is an effective non-thermal intensification technique that enhances the recovery of bioactive compounds from berry seed matrices. The significant increases in TPC, antioxidant capacity, and anthocyanin concentration observed in seed extracts from PEF-pretreated samples across most species demonstrate that the electroporation of cell membranes facilitates rapid mass transfer of intracellular phenolics into the aqueous medium. This mechanism is consistent with the well-established principles of PEF-assisted extraction, where transient pore formation in cell membranes reduces diffusion resistance and enables solvent penetration into plant tissues [23].

The enhancement of extraction efficiency observed here, while comparing to the control samples, particularly in CH, RB and BB seeds, shows trends reported for grape by-products [24]. Application of PEF enabled the improvement of TPC and antioxidant capacity against ABTS (4-fold higher TE/g value). Mango peel residues subjected to similar electric field strengths were also characterized by higher TPC than those extracted conventionally [9]. The correlation between the increased TPC and antioxidant capacity indicates that phenolic compounds are the dominant contributors to the improved radical scavenging activity of PEF-treated extracts. Moreover, the more intense color (higher a* values) and reduced lightness (L*) in these extracts are in line with the elevated anthocyanin levels, reinforcing that pigment migration is directly coupled with cell membrane permeabilization and solute diffusion. Because anthocyanin pigments are known to change coloration depending on the pH of the solution, possible variations in pH among different seed extracts may contribute to the observed differences in color parameters after PEF treatment [25]. The findings are also consistent with previous studies demonstrating that PEF pretreatment enhances the recovery of anthocyanins and pigments from grapes in the winemaking process [26,27]. PEF also improved anthocyanin content in blueberry by-product extracts [10,28] and other bioactive compounds’ extractability, like lycopene and carotenoids from tomato by-products [29].

When compared with conventional extraction methods, PEF offers several advantages. Solvent-assisted and thermally driven extractions typically require extended times or elevated temperatures, which can cause oxidation or degradation of thermolabile compounds [30,31]. In contrast, PEF operates under mild thermal conditions, preserving the integrity of phenolics and anthocyanins while achieving comparable or superior yields [32].

For instance, grape seed extractions performed in hydroethanolic media under PEF conditions achieved an increase in polyphenol yield relative to diffusion-only controls [33]. Such enhancement arises from the synergistic interaction between solvent and electrical effects–ethanol dissolves bioactive compounds while PEF induces pore formation, resulting in extensive cellular disruption and efficient compound release. In the study by Carpentieri et al. [34], it was described that with the lower ethanol concentration, the recovery of bioactive compounds was higher for the oregano and wild thyme extracts obtained from herbs pretreated with PEF. The present results obtained with water as the extraction medium indicate that even without organic solvents, PEF sufficiently disrupts berry seed structures to mobilize phenolics, demonstrating its potential for solvent-free, sustainable applications.

Species-specific differences in extraction behavior highlight the importance of structural and compositional variability among seeds, which have to be considered while planning the experiment. CH seeds exhibited the strongest response to PEF, whereas RC and BC seeds showed only moderate increases in TPC or TAC, compared to the control samples, likely due to thicker outer layers and lower initial biocompound concentrations [35]. A study by Razola-Díaz et al. [36] highlighted that applying PEF treatment enhanced procyanidin recovery from avocado seed by over 9%. Those results prove that even though the tissue of seeds is thick, PEF can penetrate through the cells.

From a technological viewpoint, the findings underscore the potential of integrating PEF into existing processing lines for berry seed oil extraction, allowing simultaneous valorization of the aqueous by-product as a rich source of natural antioxidants, which could then be applied in nutritional in vitro and in vivo studies [37,38]. The mild operating conditions, minimal solvent requirement, and scalability of continuous-flow PEF systems make this approach particularly attractive for industrial applications.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that PEF pretreatment substantially enhances the recovery of bioactive compounds from berry fruit seeds into the aqueous fraction obtained after treatment. The application of PEF significantly increased the total polyphenol content and antioxidant capacity (ABTS and DPPH assays) across most investigated species. The most efficient results were observed for chokeberry, raspberry, and blackberry seeds, where PEF treatment improved the total polyphenol content, markedly elevated radical scavenging activity, anthocyanin concentration, and release of pigments. The combined enhancement in phenolic, anthocyanin, and antioxidant profiles demonstrates the strong potential of PEF as a green intensification technology for valorizing berry seed by-products.

From an industrial and sustainability standpoint, the findings suggest that the aqueous phase obtained after PEF pretreatment—regarded as waste—represents a valuable secondary product rich in natural antioxidants and colorants. Such extracts could be further processed into natural additives for functional foods, beverages, or cosmetics, supporting the principles of circular economy and full resource utilization in fruit processing chains. Moreover, PEF technology offers the advantage of minimal thermal degradation and the possibility of integrating directly into continuous production lines, making it attractive for large-scale, solvent-free extraction applications. Future work should focus on optimizing electric field parameters for specific berry species to balance energy efficiency with compound recovery and assessing the stability and bioavailability of the recovered phenolics and anthocyanins. This study shows the technological relevance of PEF as an environmentally sustainable approach for upgrading berry seed residues into high-value sources of bioactive compounds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.P.-L.; methodology, I.P.-L., S.K. and A.W.; software, I.P.-L. and S.K.; validation, I.P.-L. and S.K.; formal analysis, I.P.-L. and S.K.; investigation, I.P.-L.; resources, I.P.-L.; data curation, I.P.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, I.P.-L.; writing—review and editing, A.G.; visualization, I.P.-L.; supervision, A.W.; project administration, A.G.; funding acquisition, A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Some research equipment was purchased as part of the “Food and Nutrition Centre—modernization of the WULS campus to create a Food and Nutrition Research and Development Centre (CŻiŻ)” co-financed by the European Union from the European Regional Development Fund under the Regional Operational Programme of the Mazowieckie Voivodeship for 2014–2020 (Project No. RPMA.01.01.00-14-8276/17).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in the following study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The Authors acknowledge Justyna Wójcik-Seliga from Cultivar Testing, Nursery and Gene Bank Resources Department, Institute of Horticulture, National Research Institute in Skierniewice, Poland, for providing Rubus var. Brzezina fruits cultivated from the gene bank collection in Dabrowice, Poland.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xi, J.; Li, Z.; Fan, Y. Recent advances in continuous extraction of bioactive ingredients from food-processing wastes by pulsed electric fields. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 1738–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naliyadhara, N.; Kumar, A.; Girisa, S.; Daimary, U.D.; Hegde, M.; Kunnumakkara, A.B. Pulsed electric field (PEF): Avant-garde extraction escalation technology in food industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 122, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjha, M.M.A.N.; Kanwal, R.; Shafique, B.; Arshad, R.N.; Irfan, S.; Kieliszek, M.; Kowalczewski, P.Ł.; Irfan, M.; Khalid, M.Z.; Roobab, U.; et al. A Critical Review on Pulsed Electric Field: A Novel Technology for the Extraction of Phytoconstituents. Molecules 2021, 26, 4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive (EU) 2025/1892 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 September 2025 Amending Directive 2008/98/EC on Waste (Text with EEA Relevance). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2025/1892/oj (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Meremäe, K.; Raudsepp, P.; Rusalepp, L.; Anton, D.; Bleive, U.; Roasto, M. In Vitro Antibacterial and Antioxidative Activity and Polyphenolic Profile of the Extracts of Chokeberry, Blackcurrant, and Rowan Berries and Their Pomaces. Foods 2024, 13, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guderjan, M.; Elez-Martínez, P.; Knorr, D. Application of pulsed electric fields at oil yield and content of functional food ingredients at the production of rapeseed oil. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2007, 8, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshabadi, H.; Mirzaei, H.; Ghodsvali, A.; Jafari, S.M.; Ziaiifar, A.M. The influence of pulsed electric fields and microwave pretreatments on some selected physicochemical properties of oil extracted from black cumin seed. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maza, M.A.; Pereira, C.; Martínez, J.M.; Camargo, A.; Álvarez, I.; Raso, J. PEF treatments of high specific energy permit the reduction of maceration time during vinification of Caladoc and Grenache grapes. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 63, 102375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parniakov, O.; Barba, F.J.; Grimi, N.; Lebovka, N.; Vorobiev, E. Extraction assisted by pulsed electric energy as a potential tool for green and sustainable recovery of nutritionally valuable compounds from mango peels. Food Chem. 2016, 192, 842–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, X.; Huang, H. Effects of pulsed electric fields on anthocyanin extraction yield of blueberry processing by-products. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2015, 39, 1898–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasecka, I.; Ostrowska-Ligęza, E.; Wiktor, A.; Górska, A. Ultrasound and pulsed electric field treatment effect on the thermal properties, oxidative stability and fatty acid profile of oils extracted from berry seeds. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2025, 150, 1311–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Ohlander, M.; Jeppsson, N.; Björk, L.; Trajkovski, V. Changes in antioxidant effects and their relationship to phytonutrients in fruits of sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) during maturation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 1485–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goiffon, J.P.; Mouly, P.P.; Gaydou, E.M. Anthocyanic pigment determination in red fruit juices, concentrated juices and syrups using liquid chromatography. Anal. Chim. Acta 1999, 382, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.W.; Zeng, X.A.; Ngadi, M. Enhanced extraction of phenolic compounds from onion by pulsed electric field (PEF). J. Food Process. Preserv. 2018, 42, e13755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia, F.J.; Luengo, E.; Corral-Pérez, J.J.; Raso, J.; Almajano, M.P. Improvements in the aqueous extraction of polyphenols from borage (Borago officinalis L.) leaves by pulsed electric fields: Pulsed electric fields (PEF) applications. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2015, 65, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Yang, R.; Zhao, W. Recent developments in the preservation of raw fresh food by pulsed electric field. Food Rev. Int. 2022, 38 (Suppl. S1), 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, H.; Fang, T.; Lin, Q.; Song, H.; Liu, B.; Chen, L. Red raspberry and its anthocyanins: Bioactivity beyond antioxidant capacity. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 66, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ancos, B.; Gonzalez, E.; Cano, M.P. Differentiation of raspberry varieties according to anthocyanin composition. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 1999, 208, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinskiene, M.; Viskelis, P.; Jasutiene, I.; Viskeliene, R.; Bobinas, C. Impact of various factors on the composition and stability of black currant anthocyanins. Food Res. Int. 2005, 38, 867–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.H.; Wang, L.H.; Zeng, X.A.; Han, Z.; Wang, M.S. Effect of pulsed electric fields (PEFs) on the pigments extracted from spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.). Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2017, 43, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puértolas, E.; Barba, F.J. Electrotechnologies applied to valorization of by-products from food industry: Main findings, energy and economic cost of their industrialization. Food Bioprod. Process. 2016, 100, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales, M.; Toepfl, S.; Butz, P.; Knorr, D.; Tauscher, B. Extraction of anthocyanins from grape by-products assisted by ultrasonics, high hydrostatic pressure or pulsed electric fields: A comparison. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2008, 9, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Yang, L.; Yang, F.; Wang, W.; Zhao, C.; Zu, Y. Content and Color Stability of Anthocyanins Isolated from Schisandra chinensis Fruit. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 14294–14310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, S.Y.; Burritt, D.J.; Oey, I. Evaluation of the anthocyanin release and health-promoting properties of Pinot Noir grape juices after pulsed electric fields. Food Chem. 2016, 196, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A.; Parpinello, G.P.; Versari, A. Recent advances and applications of pulsed electric fields (PEF) to improve polyphenol extraction and color release during red winemaking. Beverages 2018, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataro, G.; Bobinaitė, R.; Bobinas, Č.; Šatkauskas, S.; Raudonis, R.; Visockis, M.; Ferrari, G.; Viškelis, P. Improving the extraction of juice and anthocyanins from blueberry fruits and their by-products by application of pulsed electric fields. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2017, 10, 1595–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, V.; Dimopoulos, G.; Dermesonlouoglou, E.; Taoukis, P. Application of pulsed electric fields to improve product yield and waste valorization in industrial tomato processing. J. Food Eng. 2020, 270, 109778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velusamy, M.; Rajan, A.; Radhakrishnan, M. Valorisation of food processing wastes using PEF and its economic advances–recent update. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 2021–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Vian, M.A.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.S.; Nutrizio, M.; Jambrak, A.R.; Munekata, P.E.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Binello, A.; Cravotto, G. A review of sustainable and intensified techniques for extraction of food and natural products. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 2325–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzimitakos, T.; Athanasiadis, V.; Kalompatsios, D.; Mantiniotou, M.; Bozinou, E.; Lalas, S.I. Pulsed electric field applications for the extraction of bioactive compounds from food waste and by-products: A critical review. Biomass 2023, 3, 367–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussetta, N.; Vorobiev, E.; Le, L.H.; Cordin-Falcimaigne, A.; Lanoisellé, J.L. Application of electrical treatments in alcoholic solvent for polyphenols extraction from grape seeds. LWT 2012, 46, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentieri, S.; Mazza, L.; Nutrizio, M.; Jambrak, A.R.; Ferrari, G.; Pataro, G. Pulsed electric fields- and ultrasound-assisted green extraction of valuable compounds from Origanum vulgare L. and Thymus serpyllum L. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 4834–4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, S.; Pellati, F.; Melegari, M.A.; Bertelli, D. Polyphenols, anthocyanins, ascorbic acid, and radical scavenging activity of Rubus, Ribes, and Aronia. J. Food Sci. 2004, 69, FCT164–FCT169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razola-Díaz, M.d.C.; Genovese, J.; Tylewicz, U.; Guerra-Hernández, E.J.; Rocculi, P.; Verardo, V. Enhanced extraction of procyanidins from avocado processing residues by pulsed electric fields pre-treatment. LWT 2024, 212, 116952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sławińska, N.; Prochoń, K.; Olas, B. A review on berry seeds—A special Emphasis on their chemical content and health-promoting properties. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajha, H.N.; Abi-Khattar, A.M.; El Kantar, S.; Boussetta, N.; Lebovka, N.; Maroun, R.G.; Louka, N.; Vorobiev, E. Comparison of aqueous extraction efficiency and biological activities of polyphenols from pomegranate peels assisted by infrared, ultrasound, pulsed electric fields and high-voltage electrical discharges. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2019, 58, 102212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).