Microplastics in Sand: Green Protocol for Expert Citizen Science over Large Geographical Areas

Featured Application

Abstract

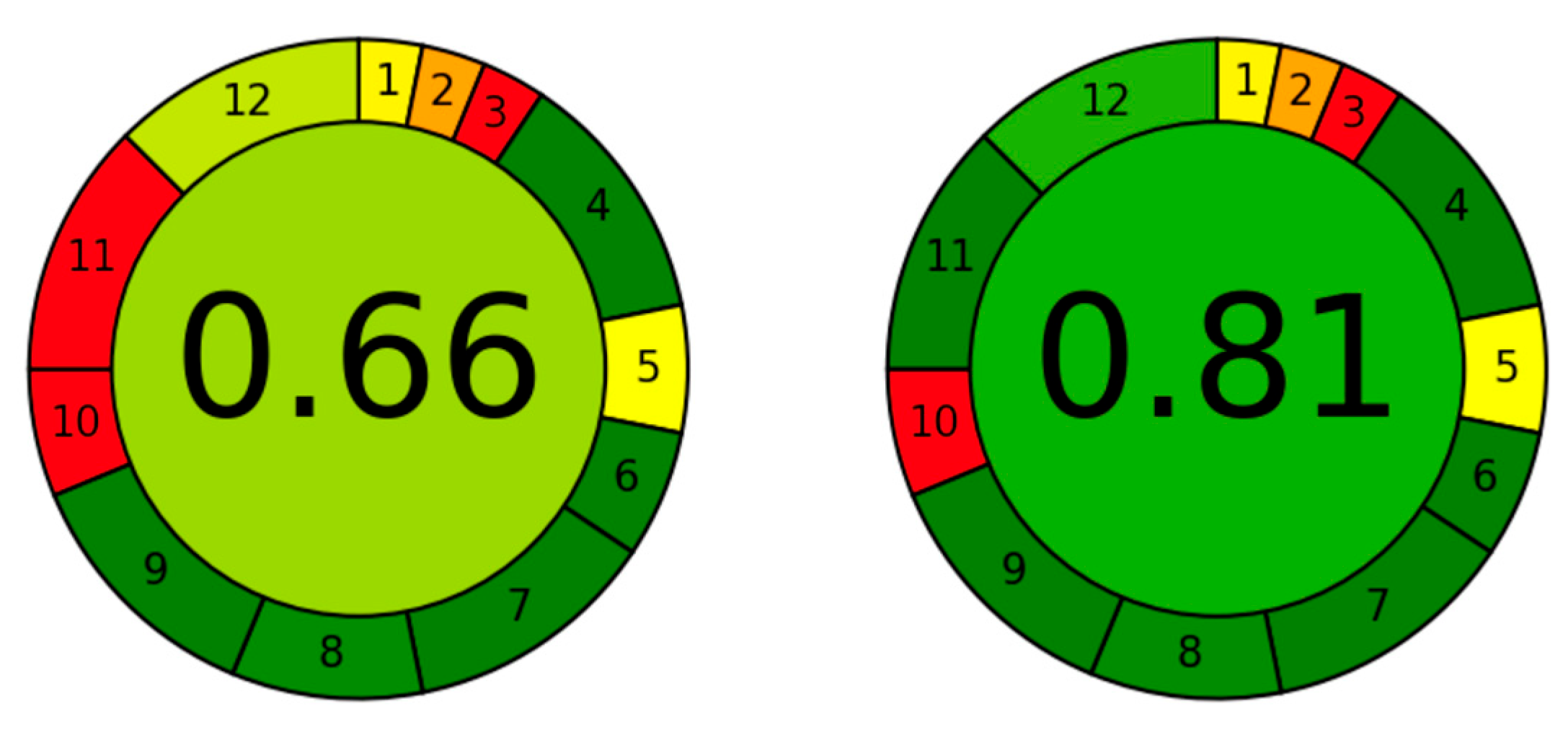

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

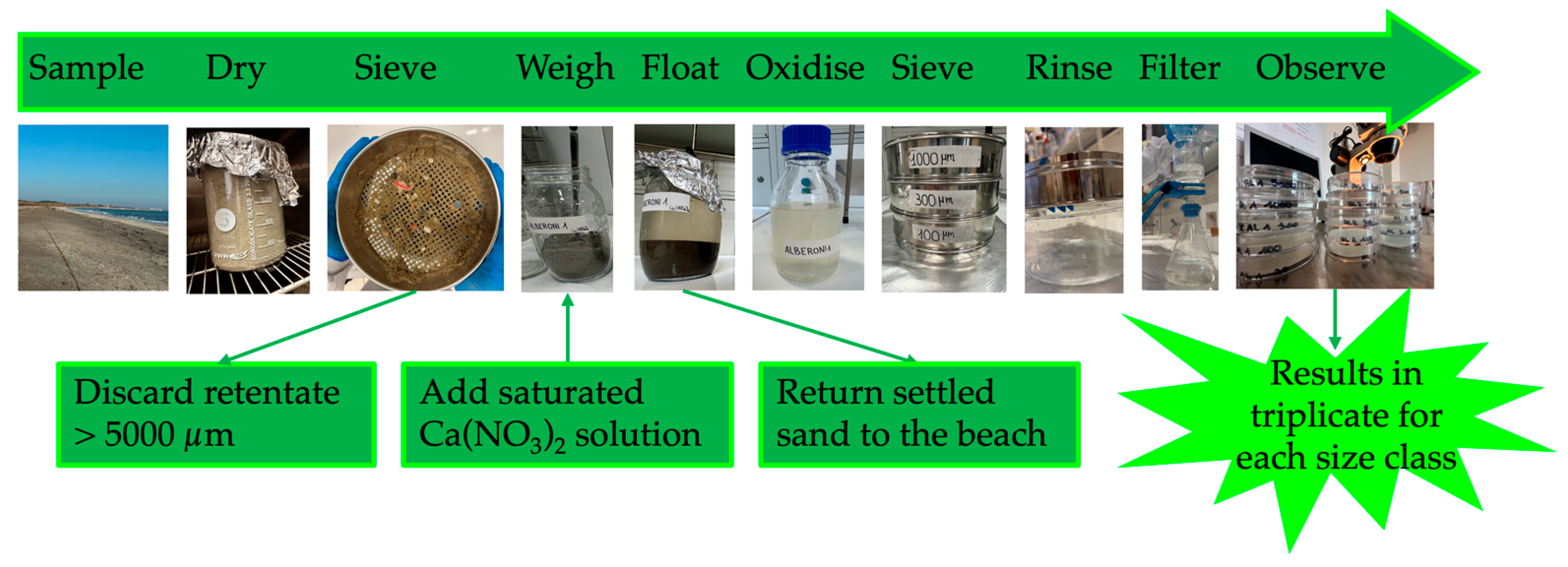

2.2. Sample Preparation, Density Separation, Organic Matter Oxidation

2.3. Identification and Classification of Microplastics

2.4. Granulometric Analysis

2.5. Cleanliness and Quality Control

3. Results and Discussion

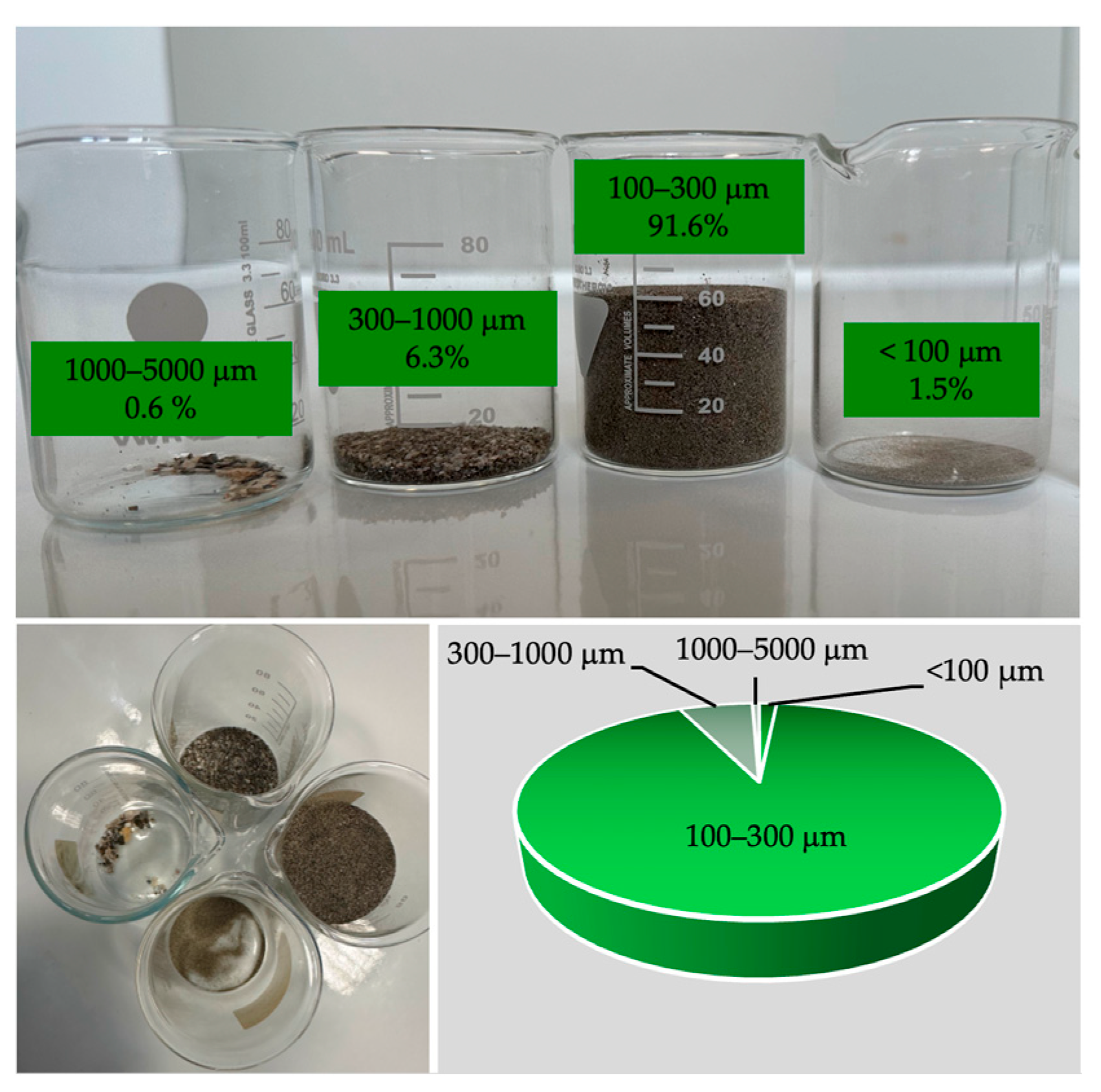

3.1. Drying and Granulometric Analysis

3.2. Critical Screening of Density Separation Media Used to Isolate MPs from the Sand

| Polymer Type | Density (g/mL) |

|---|---|

| Natural rubber | 0.92 |

| Polyethylene-low density (LDPE) a | 0.91–0.97 |

| Polyethylene-high density (HDPE) a | 0.94–0.97 |

| Polypropylene (PP) a | 0.85–0.94 |

| Polystyrene (PS) a | 0.96–1.05 |

| Polyamide (PA6 or PA66) a | 1.12–1.14 |

| Polyurethane (PU) a | 1.20 |

| Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) a | 1.20 |

| Polycarbonate (PC) a | 1.20 b |

| Polylactic acid (PLA) | 1.21–1.25 |

| Cellulose acetate (CA) | 1.28 |

| Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) a | 1.38 |

| Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) a | 1.34−1.39 |

| Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) a | 2.2 |

- Density of at least 1.45 g/mL

- No organ hazard for the sake of operator safety

- No damage to aquatic environment

- No reaction with H2O2 used to remove the organic matter

- No low pH (Polyamides at risk)

- No high pH (Polyesters at risk)

- No high viscosity

- Not expensive

3.3. Recovery of the Floating Mixture

3.4. Removal of the Organic Matter

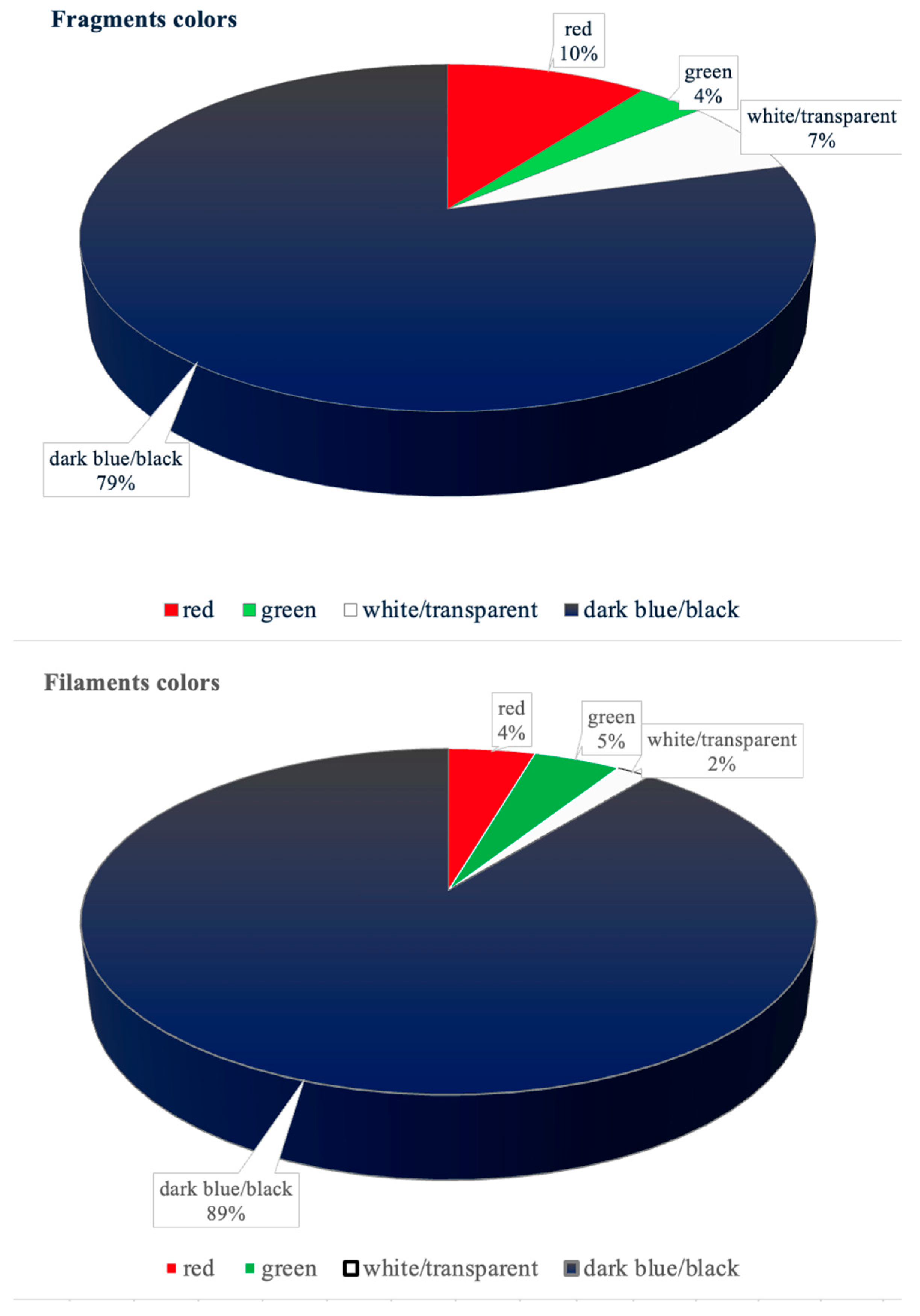

3.5. MPs Physical Classification

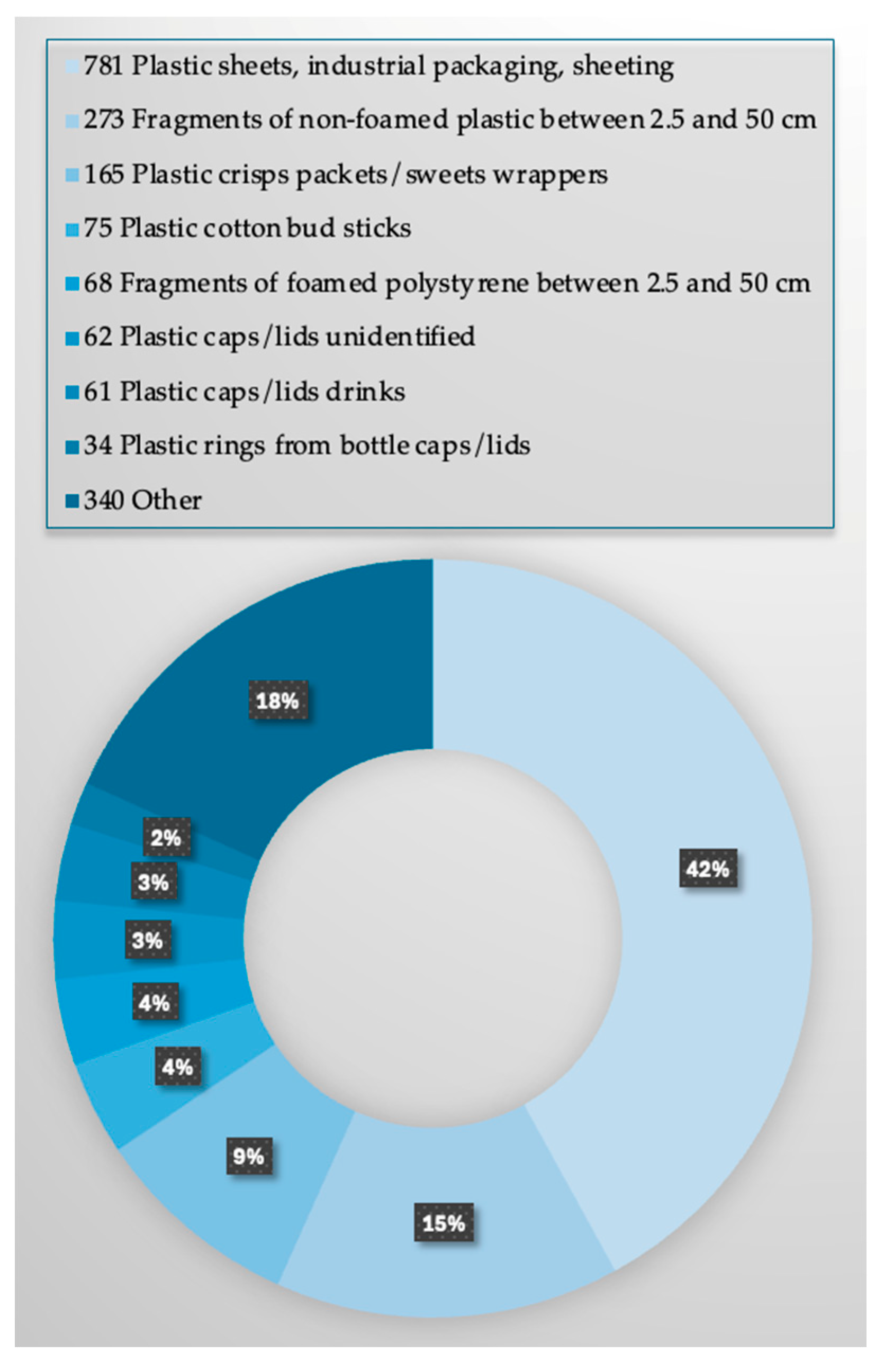

3.6. Understanding the Causes of MPs Pollution and Civic Education

3.7. A Green Protocol for Expert Citizen Science and Future Directions

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MP | Microplastic |

| VLPF | Venice Lagoon Plastic Free |

References

- UNI EN ISO 24187:2023; UNI Ente Italiano di Normazione. UNI: Milan, Italy, 2023. Available online: https://store.uni.com/uni-en-iso-24187-2023 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Ansari, I.; Arora, C.; Verma, A.; Mahmoud, A.E.D.; El-Kady, M.M.; Rajarathinam, R.; Verma, D.K.; Mahish, P.K. A Critical Review on Biological Impacts, Ecotoxicity, and Health Risks Associated with Microplastics. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GESAP. Guidelines for the Monitoring and Assessment of Plastic Litter in the Ocean: GESAMP Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection. Rep. Stud. GESAMP 2019, 99, 138. [Google Scholar]

- Cecchi, T.; De Carolis, C. Biobased Products from Food Sector Waste: Bioplastics, Biocomposites, and Biocascading; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-63435-3. [Google Scholar]

- Faussone, G.C.; Cecchi, T. Chemical Recycling of Plastic Marine Litter: First Analytical Characterization of The Pyrolysis Oil and of Its Fractions and Comparison with a Commercial Marine Gasoil. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plastic Europe 2024. Available online: https://plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/the-circular-economy-for-plastics-a-european-analysis-2024/ (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Anderson, R.J.; Turner, A. Microplastic Transport and Deposition in a Beach-Dune System (Saunton Sands-Braunton Burrows, southwest England). Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 909, 168535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchi, T. Analysis of Volatiles Organic Compounds in Venice Lagoon Water Reveals COVID 19 Lockdown Impact on Microplastics and Mass Tourism Related Pollutants. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 783, 146951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.; Lindeque, P.; Halsband, C.; Galloway, T.S. Microplastics as Contaminants in the Marine Environment: A Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 2588–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochman, C.M.; Kross, S.M.; Armstrong, J.B.; Bogan, M.T.; Darling, E.S.; Green, S.J.; Smyth, A.R.; Veríssimo, D. Scientific Evidence Supports a Ban on Microbeads. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 10759–10761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turra, A.; Manzano, A.B.; Dias, R.J.S.; Mahiques, M.M.; Barbosa, L.; Balthazar-Silva, D.; Moreira, F.T. Three-Dimensional Distribution of Plastic Pellets in Sandy Beaches: Shifting Paradigms. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nafea, T.H.; Chan, F.K.S.; Xu, H.; Wang, C.; Xiao, H.; He, J. Status of Management and Mitigation of Microplastic Pollution. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 54, 1734–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/2055—Restriction of Microplastics Intentionally Added to Products—Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs. Available online: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/sectors/chemicals/reach/restrictions/commission-regulation-eu-20232055-restriction-microplastics-intentionally-added-products_en (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- EU Directive (EU) 2019/904 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 on the Reduction of the Impact of Certain Plastic Products on the Environment. Www.Plasticseurope.De 2019, 2019, 1–19. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019L0904 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Hayes, A.; Kirkbride, P.; Leterme, S.C. Variation in Polymer Types and Abundance of Microplastics from Two Rivers and Beaches in Adelaide, South Australia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 172, 112842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khuyen, V.T.K.; Le, D.V.; Fischer, A.R.; Dornack, C. Comparison of Microplastic Pollution in Beach Sediment and Seawater at UNESCO Can Gio Mangrove Biosphere Reserve. Glob. Chall. 2021, 5, 2100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. National Park Service Microplastics on National Park Beaches. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/articles/microplastics-on-national-park-beaches.htm?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- Tran Nguyen, Q.A.; Nguyen, H.N.Y.; Strady, E.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Trinh-Dang, M.; Vo, V.M. Characteristics of Microplastics in Shoreline Sediments from a Tropical and Urbanized Beach (Da Nang, Vietnam). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 161, 111768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, M.; Sahu, S.K.; Rathod, T.; Bhangare, R.C.; Ajmal, P.Y.; Pulhani, V.; Vinod Kumar, A. Comprehensive Review on Sampling, Characterization and Distribution of Microplastics in Beach Sand and Sediments. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 2023, 40, e00221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soursou, V.; Campo, J.; Picó, Y. A Critical Review of the Novel Analytical Methods for the Determination of Microplastics in Sand and Sediment Samples. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 166, 117190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, B.A.; Pasolini, F.; Korez Lupše, Š.; Bergmann, M. Microplastic Detectives: A Citizen-Science Project Reveals Large Variation in Meso- and Microplastic Pollution along German Coastlines. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1458565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masura, J.; Baker, J.; Foster, G.; Arthur, C.; Herring, C. Laboratory Methods for the Analysis of Microplastics in the Marine Environment: Recommendations for Quantifying Synthetic Particles in Waters and Sediments; NOAA: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- EU Reports|European Marine Observation and Data Network (EMODnet). Available online: https://emodnet.ec.europa.eu/en/reports?field_report_type_new_value[]=technical (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Ruiz-Orejón, L.; Martini, E.; Hanke, G. TG ML Annual Meeting 2023. 2023. Available online: https://mcc.jrc.ec.europa.eu/documents/TG_ML_Meeting/TG_ML_meeting_summary_Brussels-21-22.06.2023.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Ronda, A.C.; Menéndez, M.C.; Tombesi, N.; Álvarez, M.; Tomba, J.P.; Silva, L.I.; Arias, A.H. Microplastic Levels on Sandy Beaches: Are the Effects of Tourism and Coastal Recreation Really Important? Chemosphere 2023, 316, 137842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, P.; Hossain, M.B.; Nur, A.A.U.; Choudhury, T.R.; Liba, S.I.; Yu, J.; Noman, M.A.; Sun, J. Microplastics in Sediment of Kuakata Beach, Bangladesh: Occurrence, Spatial Distribution, and Risk Assessment. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 860989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.R.; de Jersey, A.M.; Lavers, J.L.; Rodemann, T.; Rivers-Auty, J. Identifying Laboratory Sources of Microplastic and Nanoplastic Contamination from the Air, Water, and Consumables. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 133276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chubarenko, I.; Esiukova, E.; Khatmullina, L.; Lobchuk, O.; Grave, A.; Kileso, A.; Haseler, M. From Macro to Micro, from Patchy to Uniform: Analyzing Plastic Contamination along and across a Sandy Tide-Less Coast. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 156, 111198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Béraud, E.; Bednarz, V.; Otto, I.; Golbuu, Y.; Ferrier-Pagès, C. Plastics Are a New Threat to Palau’s Coral Reefs. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grishanov, S. Structure and Properties of Textile Materials. Handb. Text. Ind. Dye. Princ. Process. Types Dye. 2011, 1, 28–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, S.; Srinivas, S.; Santhosh, G.; Basavarajaiah, S. Mechanical and Tribological Performance Evaluation of Maleic Anhydride Grafted Ethylene Octene Copolymer Toughened Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene/Polyamide 6 Composites Strengthened with Glass Fibres. J. Text. Inst. 2021, 112, 1240–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Wontor, K.; Cizdziel, J.V.; Lu, H. Distribution and Characteristics of Microplastics in Beach Sand near the Outlet of a Major Reservoir in North Mississippi, USA. Microplast. Nanoplast. 2022, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanpeyma, P.; Baranya, S. A Review of Microplastic Identification and Characterization Methods in Aquatic Environments. Period. Polytech. Civ. Eng. 2024, 68, 684–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Ruz, V.; Gutow, L.; Thompson, R.C.; Thiel, M. Microplastics in the Marine Environment: A Review of the Methods Used for Identification and Quantification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 3060–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellón-Mena, N.D.C.; Sarmiento-Devia, R.; Romero-Murillo, P. Temporal Variability of Plastic Litter in Two Sand Beaches of San Andres Island, Colombian Caribbean. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2024, 52, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Lambert, S. Freshwater Microplastics—The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry 58; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; ISBN 9783319616148. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby, M.F. Material Profiles. In Materials and the Environment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 459–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU Commission Delegated Decision (EU) 2024/1441 of 11 March 2024 Supplementing Directive (EU) 2020/2184 of the European Parliament and of the Council by Laying down a Methodology to Measure Microplastics in Water Intended for Human Consumption (Notified Unde). Off. J. Eur. Union 2024, 1–7. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L_202401441 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Sigma Aldrich Poly(Methyl Methacrylate)|9011-14-7. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/IT/it/product/aldrich/182265?srsltid=AfmBOoon1vW1vUcpmKR9Kp0NKDtuFV81LjF8hh_OHHyLu8iWWpoVV8Vr (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Schütze, B.; Thomas, D.; Kraft, M.; Brunotte, J.; Kreuzig, R. Comparison of Different Salt Solutions for Density Separation of Conventional and Biodegradable Microplastic from Solid Sample Matrices. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 81452–81467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.; Schütze, B.; Heinze, W.M.; Steinmetz, Z. Sample Preparation Techniques for the Analysis of Microplastics in Soil—A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesium Formate|Energy Glossary. Available online: https://glossary.slb.com/terms/c/cesium_formate (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Haynes, W.M. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 97th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781498754293. [Google Scholar]

- Saliwanchik, D. Heavy Caesium Salt Containing Liquids for Use in Separation Processes. 1999. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2000036165A2/en (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Sigma-Aldrich. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/IT/it/specification-sheet/SIGMA/71913 (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Zhang, X.; Yu, K.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; He, J.; Liu, X.; Jiang, J. A Novel Heating-Assisted Density Separation Method for Extracting Microplastics from Sediments. Chemosphere 2020, 256, 127039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, B.; Murphy, F.; Ewins, C. Validation of Density Separation for the Rapid Recovery of Microplastics from Sediment. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 1491–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Meng, L.; Wang, X.; Qu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Song, X. Nitrate Sensing and Response in Plants: From Calcium Signaling to Phytohormone Regulation. J. Plant Physiol. 2025, 312, 154572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; Zhao, H.; Kobayashi, S.; Mi, Q.; Hao, A.; Iseri, Y. Effect of Remediation Reagents on Bacterial Composition and Ecological Function in Black-Odorous Water Sediments. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Song, Y.; Lu, S.; Qiu, R.; Hu, J.; Li, X.; Bigalke, M.; Shi, H.; He, D. A Method for Extracting Soil Microplastics through Circulation of Sodium Bromide Solutions. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 691, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maynard, I.F.N.; Bortoluzzi, P.C.; Nascimento, L.M.; Madi, R.R.; Cavalcanti, E.B.; Lima, Á.S.; de Lourdes Sierpe Jeraldo, V.; Marques, M.N. Analysis of the Occurrence of Microplastics in Beach Sand on the Brazilian Coast. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 771, 144777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, M.; Van Cauwenberghe, L.; Vandegehuchte, M.B.; Janssen, C.R. New Techniques for the Detection of Microplastics in Sediments and Field Collected Organisms. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 70, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, L.M.B.; Knutsen, H.; Mahat, S.; Jane, E.; Arp, P.H. Facilitating Microplastic Quantification through the Introduction of a Cellulose Dissolution Step Prior to Oxidation: Proof-of-Concept and Demonstration Using Diverse Samples from the Inner Oslofjord, Norway. Mar. Environ. Res. 2020, 161, 105080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Sun, C.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Li, Y.; Kong, F.; Zheng, H.; Luo, X.; Chen, L.; et al. Spatial Patterns of Microplastics in Surface Seawater, Sediment, and Sand Along Qingdao Coastal Environment. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 916859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, D.; Munoz, M.; Nieto-Sandoval, J.; Romera-Castillo, C.; de Pedro, Z.M.; Casas, J.A. Insights into the Degradation of Microplastics by Fenton Oxidation: From Surface Modification to Mineralization. Chemosphere 2022, 309, 136809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, M.A.; Ho, K.T.; Boving, T.B.; Russo, S.; Robinson, S.; Burgess, R.M. Comparison of Microplastic Isolation and Extraction Procedures from Marine Sediments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 159, 111507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekiff, J.H.; Remy, D.; Klasmeier, J.; Fries, E. Occurrence and Spatial Distribution of Microplastics in Sediments from Norderney. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 186, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban-Malinga, B.; Zalewski, M.; Jakubowska, A.; Wodzinowski, T.; Malinga, M.; Pałys, B.; Dąbrowska, A. Microplastics on Sandy Beaches of the Southern Baltic Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 155, 111170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.A.; Abd Razak, N.I.; Anuar, S.T.; Ibrahim, Y.S.; Rusli, M.U.; Jaafar, M. Microplastics Contamination in Natural Sea Turtle Nests at Redang Island, Malaysia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 211, 117412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basurto Alcívar, D.J.; Chavarría Peñarrieta, M.A.; Pincay Cantos, M.F.; Calderón Pincay, J.M. Microplastics on the Coasts of San Cristobal, Galapagos: A Threat to the Archipelago. Vis. Sustain. 2024, 22, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga, I.; Pinos-Vélez, V.; Capparelli, M.; Moulatlet, G.M.; Cipriani-Avila, I.; Cabrera, M.; Rebolledo, E.; Arnés-Urgellés, C.; Cazar, M.E. Microplastic Occurrence and Distribution in the Gulf of Guayaquil, Ecuador. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 209, 117288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esiukova, E.; Lobchuk, O.; Haseler, M.; Chubarenko, I. Microplastic Contamination of Sandy Beaches of National Parks, Protected and Recreational Areas in Southern Parts of the Baltic Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 173, 113002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, C.; Saliu, F.; Bosman, A.; Sammartino, I.; Raguso, C.; Mercorella, A.; Galvez, D.S.; Petrizzo, A.; Madricardo, F.; Lasagni, M.; et al. Hotspots of Microplastic Accumulation at the Land-Sea Transition and Their Spatial Heterogeneity: The Po River Prodelta (Adriatic Sea). Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 895, 164908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunitha, T.G.; Monisha, V.; Sivanesan, S.; Vasanthy, M.; Prabhakaran, M.; Omine, K.; Sivasankar, V.; Darchen, A. Micro-Plastic Pollution along the Bay of Bengal Coastal Stretch of Tamil Nadu, South India. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 756, 144073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eo, S.; Hong, S.H.; Song, Y.K.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Shim, W.J. Abundance, Composition, and Distribution of Microplastics Larger than 20 Μm in Sand Beaches of South Korea. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 238, 894–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecchi, T.; Poletto, D.; Berbecaru, A.C.; Cârstea, E.M.; Râpă, M. Assessing Microplastics and Nanoparticles in the Surface Seawater of Venice Lagoon—Part I: Methodology of Research. Materials 2024, 17, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanhai, L.D.K.; Gårdfeldt, K.; Lyashevska, O.; Hassellöv, M.; Thompson, R.C.; O’Connor, I. Microplastics in Sub-Surface Waters of the Arctic Central Basin. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 130, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graca, B.; Szewc, K.; Zakrzewska, D.; Dołęga, A.; Szczerbowska-Boruchowska, M. Sources and Fate of Microplastics in Marine and Beach Sediments of the Southern Baltic Sea—A Preliminary Study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 7650–7661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwood, E.C.; Falcieri, F.M.; Piehl, S.; Bochow, M.; Matthies, M.; Franke, J.; Carniel, S.; Sclavo, M.; Laforsch, C.; Siegert, F. Coastal Accumulation of Microplastic Particles Emitted from the Po River, Northern Italy: Comparing Remote Sensing and Hydrodynamic Modelling with in Situ Sample Collections. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 138, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Shi, L.; Huang, H.; Ye, K.; Yang, L.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Li, D.; Shi, Y.; Xiao, L.; et al. Analysis of Aged Microplastics: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 1861–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena-Pereira, F.; Wojnowski, W.; Tobiszewski, M. AGREE—Analytical GREEnness Metric Approach and Software. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 10076–10082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonney, R.; Cooper, C.B.; Dickinson, J.; Kelling, S.; Phillips, T.; Rosenberg, K.V.; Shirk, J. Citizen Science: A Developing Tool for Expanding Science Knowledge and Scientific Literacy. Bioscience 2009, 59, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbau, C.; Lazarou, A.; Bajt, O.; Filipović Marijić, V.; Simčič, T.; Coltorti, M.; Pignoni, E.; Simeoni, U. Citizen Science for Monitoring Plastic Pollution from Source to Sea: A Systematic Review of Methodologies, Best Practices, and Challenges. Water 2025, 17, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Solute, Hazard Classifications | Pictogram(s) | Saturated Solution Density at Room Temperature (g/mL) | Reference | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium Chloride Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 | 1.2 | [3] | Unsuitable for high-density polymers | |

| Sodium hexametaphosphate Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 | 1.30 | [40] | Unsuitable for high-density polymers | |

| Calcium Chloride H319 Causes serious eye irritation. |  | 1.4 | [41] | Unsuitable for high-density polymers |

| Sucrose Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008. | 1.45 | This study | Too viscous | |

| Iron (III) Chloride H290 May be corrosive to metals H302 Harmful if swallowed H315 Causes skin irritation H318 Causes serious eye damage |   | 1.45 | This study | Acidic pH endangers polyamides |

| Calcium Nitrate H302: Harmful if swallowed. H318: Causes serious eye damage. |   | 1.5 | This study | |

| Xylitol Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008. | 1.5 | This study | Too viscous | |

| Potassium Formate Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008. | 1.57 | [41] | Vigorous reaction with H2O2 | |

| Sodium Silicate H290: May be corrosive to metals H314: Causes severe skin burns and eye damage H318: Causes serious eye damage H335: May cause respiratory irritation |   | - | Too viscous, Alkaline pH endangers polyesters | |

| Zinc Chloride H302: Harmful if swallowed. H314: Causes severe skin burns and eye damage. H318: Causes serious eye damage H335: May cause respiratory irritation. H400: Very toxic to aquatic life H410: Very toxic to aquatic life with long lasting effects. |    | 1.6–1.7 | [3] | Very toxic to aquatic life with long lasting effects. |

| Sodium Iodide H303: May be harmful if swallowed H315 + H319 Causes skin and serious eye irritation H372 Causes damage to organs (thyroid gland) through prolonged or repeated exposure (if swallowed) H400 Very toxic to aquatic life |    | 1.6 | [3] | Causes damage to organs Very toxic to aquatic life with long lasting effects. |

| Potassium Iodide H372 Causes damage to organs (Thyroid) through prolonged or repeated exposure if swallowed. |  | 1.7 | [41] | Causes damage to organs Vigorous reaction with H2O2 |

| Calcium Bromide H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |  | 1.71 | This study | Vigorous reaction with H2O2 |

| Strontium Bromide H315 Causes skin irritation H319 Causes serious eye irritation H335 May cause respiratory irritation |  | - | Vigorous reaction with H2O2 | |

| Cesium Chloride H361fd Suspected of damaging fertility. Suspected of damaging the unborn child |  | 1.9 | This study | Causes damage to organs |

| Zinc Bromide H302 Harmful if swallowed H314 Causes severe skin burns and eye damage H318: Causes serious eye damage. H317 May cause an allergic skin reaction H411 Toxic to aquatic life with long lasting effects. |    | 1.99 | This study | Vigorous reaction with H2O2 Toxic to aquatic life with long lasting effects. |

| Cesium Iodide H361fd Suspected of damaging fertility Suspected of damaging the unborn child H400 Very toxic to aquatic life |   | 2.4 (estimated) | Causes damage to organs Very toxic to aquatic life | |

| Cesium Formate H302 Harmful if swallowed H319 Causes serious eye irritation. H371 May cause damage to organs (Nervous system) if swallowed H373 May cause damage to organs (Nervous system, Blood) through prolonged or repeated exposure if swallowed |   | 2.4 | [42] | Causes damage to organs |

| Potassium carbonate H315 Skin irritation H319 Eye irritation H335 May cause respiratory irritation |  | 2.43 (14 °C) | [43] | Alkaline pH endangers polyesters |

| Cesium tungstate H302 Harmful if swallowed H315 Causes skin irritation H319 Causes serious eye irritation H335 May cause respiratory irritation |  | 3.0133 | [44] | Too expensive |

| Sodium Polytungstate H302 Harmful if swallowed. H318 Causes serious eye damage. H412 Harmful to aquatic life with long lasting effects |   | 3.1 (20 °C) | [45] | Too expensive Harmful to aquatic life with long lasting effects |

| Size Class | Filament/Fiber | Fragment | Film | Beads/Pellet | Sponge | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000–5000 μm | 29 ± 8 | 29 ± 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 59 |

| 300–1000 μm | 39 ± 10 | 26 ± 8 | 1 ± 1 | 6 ± 2 | 0 | 72 |

| 100–300 μm | 42 ± 11 | 31 ± 9 | 4 ± 1 | 11 ± 4 | 0 | 88 |

| Total | 110 | 87 | 5 | 17 | 0 |

| Location | Study Design | MPs/kg | Prevalent Shape | Size Range (μm) | Prevalent Polymer | Prevalent Color | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baltic Sea shore, Poland | Drying (60 °C) SV (cascade, 5000, 2000, 1000, 500 μm) DS (ZnCl2 only for the 2000–500 μm fractions) FL (174 μm) DG (H2O2 30%, 75 °C) Calcite removal (HCl) DS (ZnCl2) FL (174 μm) Drying | 68 ± 117 | Mostly fibers | 500–5000 | - | Transparent/White | [62] |

| Curonian Spit National Park, Russia | Drying SV (cascade, 5000, 2000, 1000, 500 μm) DS (ZnCl2 only for the 2000–500 μm fractions) FL (174 μm) DG (FR 75 °C) Calcite removal (HCl) DS (ZnCl2) FL(174 μm) Drying | 115 ± 61 | Mostly fibers (74.3%) | 500–5000 | PE | - | [28] |

| The Po River, prodelta Adriatic Sea, Northern Italy | DR (50 °C) a-Large MPs (500–5000 μm) scrutinized via a stereomicroscope b-Small MPs (5–500 μm) DG (H2O2 30%) FL (5 μm stainless steel) DS (ZnCl2) FL (Whatman® GF/C 1.2 μm) | 139.7 ± 80 | Mostly Fibers and Fragments | 5–5000 | PA | Gray/blue | [63] |

| Kuakata Beach, Bangladesh | DR (90 °C) DS (ZnCl2) SV (300 μm) DR (90 °C) DG (FR, 75 °C for 30 min on the dried retentate) FL (5.0 μm cellulose nitrate) | 232 ± 52 | Mostly fibers | 300–5000 | PET | Transparent | [26] |

| Marina Beach, India | DR (60 °C) SV (300 μm) DG (30% H2O2 on sand) DR (60 °C) DS (NaI) FL (Whatman® grade GF/C filter 1.2 μm) | 330.8 ± 364.6 | Mostly Fibers | 300–5000 | - | Blue/Pink | [64] |

| Inner Oslofjord, Norway | Debris Removal SV (stainless-steel 45 μm) Two-step digestion (NaOH/urea/thiourea −20 °C and 30% H2O2/1%NaOH) | 750 ± 477 | n.a. | 45–5000 | PE | - | [53] |

| Qingdao coast, China | DR (RT) DS (ZnCl2) FL (5 μm nitrocellulose) DG (FR 65 °C for 72 h on the scraped particles) FL (0.45 μm nitrocellulose) | 3602 ± 1708 | Mostly Fibers and Fragments | 50–5000 | Chlorinated Polyethylene | White | [54] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cecchi, T. Microplastics in Sand: Green Protocol for Expert Citizen Science over Large Geographical Areas. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13007. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413007

Cecchi T. Microplastics in Sand: Green Protocol for Expert Citizen Science over Large Geographical Areas. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13007. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413007

Chicago/Turabian StyleCecchi, Teresa. 2025. "Microplastics in Sand: Green Protocol for Expert Citizen Science over Large Geographical Areas" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13007. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413007

APA StyleCecchi, T. (2025). Microplastics in Sand: Green Protocol for Expert Citizen Science over Large Geographical Areas. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13007. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413007