Abstract

This study presents an open and replicable methodology for multi-lead ECG signal quality assessment (SQA), implemented on a 12-lead embedded acquisition platform. Signal quality is a critical software component for diagnostic reliability and compliance with international standards such as IEC 60601-2-27 (clinical ECG monitors), IEC 60601-2-47 (ambulatory ECG systems), and IEC 62304 (software life cycle for medical devices) which define the essential engineering requirements and functional performance for medical devices. Unlike proprietary SQA algorithms embedded in closed commercial systems such as Philips DXL™, the proposed method provides a transparent and auditable framework that enables independent validation and supports adaptation for research and clinical prototyping. Our approach combines convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with FFT-derived spectrograms to perform four-level signal quality classification (High, Medium, Low, and Unidentifiable), achieving up to 95.67% accuracy on the test set, confirming the robustness of the CNN-based spectrogram classification model. The algorithm has been validated on a custom controlled dataset generated using the Fluke PS420™ hardware simulator, enabling controlled replication of signal artifacts for software-level evaluation. Designed for execution on resource-constrained embedded platforms, the system integrates real-time preprocessing and wireless transmission, demonstrating its feasibility for deployment in mobile or decentralized ECG monitoring solutions. These results establish a software validation proof-of-concept that goes beyond algorithmic performance, addressing regulatory expectations such as those outlined in FDA’s Good Machine Learning Practice (GMLP). While clinical validation remains pending, this work contributes a standards-aligned methodology to democratize advanced SQA functionality and support future regulatory-compliant development of embedded ECG system.

1. Introduction

The development of intelligent biomedical devices increasingly requires an integrated approach that combines hardware design, embedded software, artificial intelligence (AI), and regulatory governance within a unified validation pipeline. Although AI models have achieved impressive diagnostic accuracy in biomedical signal processing, most research remains focused on isolated algorithmic performance metrics such as accuracy or F1-score without addressing the regulatory, safety, and engineering requirements necessary for clinical translation [1,2,3]. This misalignment between algorithmic innovation and compliance engineering contributes to the gap that still exists between academic prototypes and deployable medical devices [4,5,6]. To bridge this divide, it is essential to establish end-to-end development frameworks that ensure traceability from hardware acquisition and signal quality assurance to software verification, AI interpretability, and regulatory compliance [7,8].

Within electrocardiography (ECG), signal quality assessment (SQA) represents a key functional layer for diagnostic reliability and device performance [9]. Commercial electrocardiographic analysis systems such as Philips DXL™ and GE Marquette 12SL™ represent clinically validated, FDA-cleared algorithms widely deployed in hospital-grade ECG equipment (e.g., MUSE™ v10, MAC VU360). However, these architectures operate as proprietary “black-box” solutions, which restrict external validation, reproducibility, and open benchmarking in the scientific community [9,10,11]. As a result, most academic efforts have concentrated on improving algorithmic performance through deep learning approaches such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrent networks, and hybrid attention models trained on publicly available datasets including CinC11, CinC17, and MIT-BIH [12,13,14]. Yet, these models are rarely accompanied by standardized pipelines for software validation or compliance documentation, preventing their translation into regulated medical devices.

In contrast, we introduce an open and reproducible development pipeline that harmonizes hardware (HW), software (SW), and edge AI components within a regulatory-aligned process. The proposed platform unifies acquisition, processing, and validation stages in accordance with international standards, including IEC 60601-2-27 (safety and essential performance of clinical ECG monitors), IEC 60601-2-47 (ambulatory ECG systems), and IEC 62304 (software life cycle for medical devices) [15,16,17]. Complementary standards such as ISO 14971 for risk management and the FDA’s Good Machine Learning Practice (GMLP) guidelines [18,19] are incorporated to ensure continuous monitoring, transparency, and control over algorithmic updates. Together, these standards provide the foundation for traceability across the product life cycle, including hardware verification, signal integrity validation, and AI model governance. It should be noted that these standards are invoked strictly for their engineering design requirements and performance definitions in medical device development and are not related to editorial guidelines or terminology standards.

The platform developed in this study includes a 12-lead embedded ECG acquisition module with Wi-Fi communication and low-latency preprocessing designed to support modular integration of intelligent algorithms. To generate a reproducible and controlled benchmark, ECG signals were acquired using the Fluke PS420™ medical simulator, which reproduces physiological and noise artifacts under standardized, repeatable conditions [20]. This approach allows for precise quantification of signal degradation scenarios such as baseline drift, power line interference, and electrode disconnection, providing a ground truth for evaluating SQA algorithms. The controlled dataset was then used to train and validate a CNN-based model operating on FFT-derived spectrograms, which reproduces the four-level SQA classification scheme (High, Medium, Low, and Unidentifiable) used in clinical-grade devices [10,11]. Additionally, the methodology was benchmarked using real ECG datasets from PhysioNet (CinC11, CinC17, MIT-BIH) to assess cross-domain generalization and validate interoperability between synthetic hardware-simulated and real-world signals [21,22,23].

More broadly, this pipeline embodies the concept of governance-oriented engineering, in which hardware, software, and AI components are co-developed under shared traceability and quality management requirements. Recent literature emphasizes that medical AI systems must embed regulatory compliance and explainability mechanisms by design rather than addressing them as post-development tasks [24,25]. The FDA’s GMLP principles and the European Union’s AI Act further highlight the necessity of transparent documentation, risk management, and continuous learning oversight in AI-enabled medical devices [19,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Similarly, emerging works on edge AI and embedded ML advocate for architectures that guarantee signal quality validation and computational determinism at the hardware level [32,33].

By adhering to these frameworks, the proposed system not only demonstrates technical feasibility but also establishes a replicable pathway for developing certifiable, embedded medical AI devices aligned with global standards. To contribute to the generation of databases with reduced class imbalance between high- and low-quality labeled signals, this study proposes the development of an acquisition platform and a protocol to collect samples across different quality categories. Once the samples are obtained, and to support the adoption of Non-Feature-Based (NFB) methodologies, spectrogram generation is implemented to relate the frequency spectrum and waveform morphology, providing a comprehensive representation of noise in the ECG signal. These quality levels are pre-defined and labeled into four categories: High Quality, Medium Quality, Low Quality, and Unidentifiable. The collected samples are processed to identify the QRS complex and segmented into fixed-duration time windows.

Section 2 provides a detailed description of the development of the signal acquisition platform, the generation of the 12-lead ECG database, and the validation of signal quality using spectrograms and a convolutional neural network. Section 3 presents the experimental results and metric values used to assess classification accuracy for each quality category. Section 4 discusses the advantages and limitations of the proposed method through a comparative analysis of different algorithms in ECG quality classification accuracy. Additionally, a graphical user interface (GUI) is introduced, demonstrating the functionality of the artificial intelligence model for multi-level ECG waveform quality classification, with potential applications in hospital environments. Finally, Section 5 provides conclusions, outlining the study’s limitations and contributions to the clinical validation of ECG signal quality.

2. Materials and Methods: A Methodological Pipeline for ECG Signal Quality Assessment (SQA)

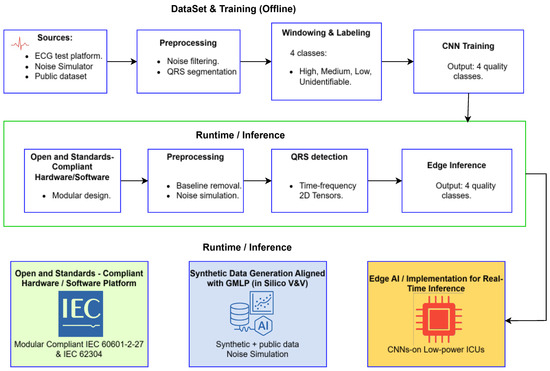

This section presents the methodological components of the proposed pipeline for the development of an intelligent medical device, encompassing the complete process from the hardware platform to the implementation of the artificial intelligence model. The framework emphasizes reproducibility, data provenance, and feasibility for embedded systems. The entire development process is organized within a unified, governance-oriented framework that integrates hardware design, software development, and artificial intelligence implementation. As illustrated in Figure 1, the proposed pipeline is organized into two main phases referred to as Dataset and Training and Runtime and Inference. These phases are interconnected through three methodological pillars that collectively ensure regulatory alignment and technical consistency throughout the entire process.

Figure 1.

Regulation-aligned development pipeline integrating hardware and software acquisition, in silico validation, and embedded AI deployment. The upper section depicts the Dataset and Training phase, while the lower section illustrates the Runtime and Inference phase for real-time ECG quality classification.

Pillar 1 establishes open and standards-compliant hardware and software foundation for ECG acquisition. The design follows international regulations, including IEC 60601-2-27, which specifies essential safety and performance requirements for electrocardiographic monitoring equipment, and IEC 62304, which defines the software life cycle processes for medical devices. This first pillar ensures that both data acquisition and preprocessing are traceable, reproducible, and consistent with recognized regulatory frameworks for clinical safety and performance. This underscores that our references to standards (IEC 60601, IEC 62304, FDA, etc.) pertain strictly to regulatory design and performance criteria for the device, rather than any guidelines for editorial style or terminology.

Pillar 2 introduces a software-centered in silico verification and validation methodology that uses hardware-simulated data generation explicitly aligned with the principles of Good Machine Learning Practice (GMLP). This methodological stage corresponds to the upper part of Figure 1, which represents the Dataset and Training phase. In this phase, controlled ECG signals obtained from simulators, open databases, and test platforms are preprocessed, segmented, labeled, and used to train a convolutional neural network capable of classifying ECG signal quality into four categories: high, medium, low, and unidentifiable. This approach ensures rigorous data provenance, controlled variability, and reproducibility in model development.

Pillar 3 focuses on the implementation and optimization of the artificial intelligence model for embedded systems, representing the transition from offline training to the Runtime and Inference phase shown in the lower part of Figure 1. In this phase, the trained model is deployed on a modular hardware platform that performs real-time preprocessing, QRS detection, and edge inference. The model achieves accurate signal quality classification with low latency and high computational efficiency, supporting its applicability in portable or clinical monitoring environments. Together, these three pillars establish an integrated and regulation-oriented framework that connects compliant data acquisition, software validation aligned with GMLP, and efficient edge artificial intelligence deployment. This structure is designed to bridge the existing gap between academic prototypes and certifiable, deployable medical devices.

2.1. Pillar 1: Open and Standards-Compliant Hardware/Software Acquisition Platform

The foundation of the proposed pipeline is an open and reproducible twelve-lead ECG acquisition platform designed to meet international regulatory standards. The analog front-end is implemented using the ADS1298 integrated circuit from Texas Instruments, a device that combines high-precision analog-to-digital converters (ADCs) with low-noise programmable gain amplifiers (PGAs). The ADS1298 includes eight simultaneous-sampling ADCs and a programmable multiplexer that allows channel selection and adjustable gain configurations. The internal PGA supports gains of 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 12, providing flexibility for signal conditioning across diverse patient conditions and electrode configurations. The chip operates with a sampling rate configurable from 250 samples per second (sps) up to 32 kilosamples per second (ksps). It incorporates an integrated test signal generator, a right-leg drive circuit for common-mode noise reduction, and an embedded SPI communication interface. Upon initialization, the internal crystal oscillator stabilizes as the reference clock through the activation of the CLKSEL and RESET pins, after which the START signal enables acquisition mode. Data communication with the host microcontroller follows a standard SPI protocol, utilizing four control lines (CS, SCLK, DIN, and DOUT) along with a DRDY (Data Ready) indicator that flags the availability of new samples. The digital control and communication tasks are managed by a 32-bit Tiva™ TM4C129XNCZAD microcontroller, which performs initial preprocessing and data transmission to the host computer. The ECG data are transmitted through a virtual COM interface using open-source software developed in Python (version 3.13.5), allowing acquisition from eight physical analog channels. The remaining four leads are algebraically derived according to Einthoven’s and Goldberger’s equations, resulting in a complete twelve-lead dataset suitable for clinical analysis.

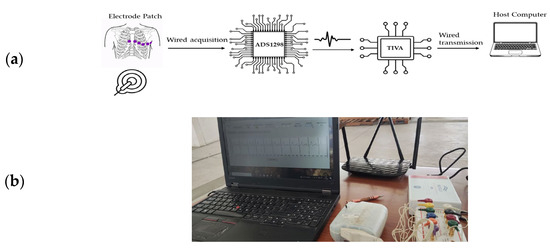

Figure 2a illustrates the overall architecture and electronic components integrated into the ECG acquisition platform, while Figure 2b shows the implemented prototype used for dataset generation and signal quality classification across four categories (high, medium, low, and unidentifiable). The system’s modular design enables straightforward integration with preprocessing, noise filtering, and QRS detection stages that form part of the broader intelligent analysis pipeline depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 2.

(a) Architecture and electronic components implemented in the acquisition of the ECG signal, (b) ECG Signal Acquisition Platform for Database Generation with Four-Category Quality Classification.

This acquisition platform was designed with regulatory compliance as a primary requirement. The hardware and communication architecture conform to the requirements of IEC 60601-2-27 for clinical electrocardiographic monitoring equipment and IEC 60601-2-47 for ambulatory ECG systems. Additionally, the software workflow aligns with IEC 62304, ensuring adherence to medical software life cycle processes. During development, electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) and signal integrity (SI) considerations were incorporated from the early design stages. These include the implementation of ground plane segmentation, differential signal routing, decoupling strategies for analog and digital domains, and shielding configurations to minimize noise coupling. The experience gained from previous laboratory validations in EMC testing and SI analysis guided the PCB layout, power distribution, and component placement to ensure low noise performance and regulatory readiness for future certification.

By embedding these regulatory and design considerations into the foundation of the system, the proposed platform ensures both electrical safety and essential performance while maintaining the precision required for AI-driven ECG quality assessment. Beyond the hardware layer, this platform serves as the physical interface within a unified architecture that integrates acquisition, preprocessing, and intelligent inference. The offline stage encompasses dataset construction, spectrogram generation, and convolutional neural network (CNN) training, whereas the runtime stage executes real-time acquisition, baseline correction, QRS detection, and model inference. The CNN inference module produces four quality levels of ECG signals, which can be displayed through a graphical interface resembling clinical systems such as PHILIPS DXL and can be extended to telemedicine applications.

2.2. Pillar 2: GMLP-Aligned Hardware-Simulated Data Generation Methodology (In Silico V&V)

The development and evaluation of artificial intelligence systems for medical devices require access to datasets that are both representative and traceable. However, during the early stages of research, particularly for embedded or low-power platforms, the use of real patient data often poses ethical, logistical, and regulatory constraints. To address these limitations, the proposed work adopted an in silico hardware-simulated data generation methodology aligned with the Good Machine Learning Practice (GMLP) principles established by the International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF, 2024). This approach ensures that model verification and validation (V&V) are conducted under conditions that prioritize data integrity, reproducibility, and patient safety before any clinical testing. It is important to clarify that these signals are generated by a precision electronic instrument (Fluke PS420, Fluke Biomedical, Everett, WA, USA), and not by generative artificial intelligence models.

According to GMLP Principle 5, the reference standards used for model training and evaluation must be fit-for-purpose and scientifically justified. In this study, the Fluke PS420™ ECG simulator was employed as a validated, industry-recognized reference source for controlled waveform generation. The simulator provides twelve independent ECG leads referenced to the right leg and allows precise control of amplitude and frequency parameters. It also enables the deliberate introduction of realistic artifacts such as power-line interference (50/60 Hz), muscle artifacts, baseline drift, and respiratory motion noise. These capabilities make it an ideal and fully traceable tool for constructing hardware-simulated datasets that replicate real-world variability while maintaining a documented ground truth. The database generation protocol followed a structured procedure consistent with GMLP Principles 2, 3, and 8, which emphasize robust engineering and quality practices, representativeness of data relative to the intended use environment, and validation of model performance under clinically relevant conditions. The simulator-generated signals were acquired using the same hardware platform described in Section 2.1 (ADS1298 + Tiva™ TM4C129XNCZAD), ensuring hardware–software traceability and confirming that the embedded acquisition path faithfully reproduces physiological signal behavior under both standard and perturbed conditions. To guarantee clinical relevance and traceability, the simulator output was validated using an Edan IM50™ patient monitor, which served as an independent reference for diagnostic signal quality assessment. The monitor’s internal algorithm classified the simulated signals according to diagnostic usability and triggered alarms when artifact thresholds compromised interpretability. This dual validation—instrumental and algorithmic—ensured that every recorded sample was correctly categorized and reproducible, aligning with GMLP Principle 4, which requires the independence of training and testing sources, and Principle 8, which demands performance evaluation under realistic clinical conditions.

After validation, the hardware-simulated dataset was organized into four diagnostic quality levels reflecting a continuum of signal degradation. High-quality signals represented normal sinus rhythm at 1 mV amplitude and 80 bpm, medium-quality signals corresponded to rhythms with superimposed noise such as 60 Hz interference or motion artifacts that still allowed diagnostic interpretation, low-quality signals were characterized by strong baseline drift or broadband noise that hindered interpretation, and unidentifiable signals simulated electrode disconnection or the absence of measurable electrical activity. The artifact generation codes and operational parameters used in the simulator are summarized in Table 1, providing complete documentation of the controlled conditions under which each waveform was produced. This traceability ensures that all simulated data can be replicated and audited in compliance with GMLP documentation requirements.

Table 1.

Fluke PS420™ Simulator Codes Implemented for Database Generation.

To standardize the input for the artificial intelligence model and guarantee methodological reproducibility, the continuous ECG signals were processed through a unified detection and segmentation protocol. The Hamilton–Tompkins [34] algorithm was implemented to identify QRS complexes, using the R-wave as the fiducial point. Based on this detection, each signal was segmented into 0.8 s time windows, centered on the R-peak (±0.4 s), ensuring that each high-quality segment contained at least one diagnostically relevant waveform. This procedure standardized the sample length and facilitated batch processing for the convolutional neural network (CNN). Nevertheless, a methodological limitation is acknowledged: in the low-quality and unidentifiable categories, the Hamilton–Tompkins algorithm frequently fails to detect reliable R-peaks, making the 0.8 s segmentation partially arbitrary. Although this constraint was a technical necessity to maintain uniform input dimensions for the CNN, it introduces a potential methodological bias, as it does not fully represent a continuous real-world acquisition scenario for degraded signals. The impact of this arbitrary segmentation on model generalization should therefore be evaluated in future studies using real clinical datasets.

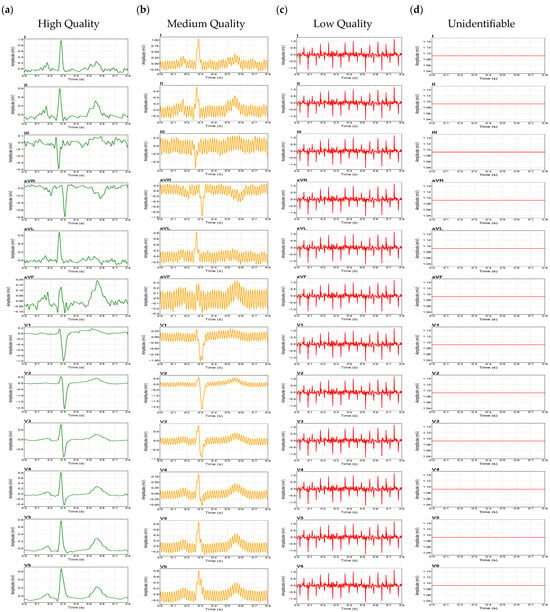

Following segmentation, a total of 6242-time windows of 0.8 s were generated from the simulator signals. The dataset was deliberately organized to mitigate the strong class imbalance typically observed in public ECG repositories, yielding 1121 high-quality segments, 1121 medium-quality segments, 2000 low-quality segments, and 2000 unidentifiable segments. To provide a clear visual summary of the dataset composition, Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of the generated ECG segments across the four signal quality levels, highlighting representative examples of each category. This graphic overview supports the interpretability of the classification task and underscores the progressive degradation of waveform morphology between quality classes. The entire dataset was then partitioned according to the gold-standard 80/10/10 stratified protocol to prevent optimistic bias, resulting in 4993 windows for training, 625 for validation, and 624 for testing. Importantly, this division was performed before any significant preprocessing, such as normalization or spectrogram generation, to avoid data leakage among subsets. All data-derived parameters, including means and standard deviations used for normalization, were computed exclusively from the training set and subsequently applied identically to the validation and test sets, ensuring that no information from the evaluation subsets influenced the learning process.

Figure 3.

Representative ECG waveforms for the four quality classes: (a) High Quality, (b) Medium Quality, (c) Low Quality, (d) Unidentifiable.

Overall, this integrated segmentation and dataset construction methodology establishes a reproducible experimental foundation aligned with GMLP principles, guaranteeing data traceability, standardized input representation, and rigorous separation between training and evaluation stages. These practices collectively enable a transparent, regulation-ready framework for the development of AI-based ECG signal quality assessment systems.

2.3. Pillar 3: Edge AI Implementation—Preprocessing and Model

This pillar focuses on the design and implementation of the artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm optimized for computational efficiency in embedded systems (Edge AI). The objective of this stage is to ensure that the model performs complex classification tasks under strict constraints of latency and power consumption, making it feasible for real-time deployment in portable or low-resource biomedical devices. Within this framework, the methodological process integrates the generation of spectrograms through the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and the subsequent classification using a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) specifically optimized for embedded execution.

To extract time–frequency characteristics from the segmented ECG signals, spectrograms were generated from 0.8 s windows. Each segment was processed using the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), implemented efficiently via the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). As theoretical foundation, the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) converts a discrete signal into its frequency components, as expressed in Equation (1):

While more advanced time–frequency methods such as Wavelet or Stockwell transforms offer higher resolution, they are computationally intensive and impractical for embedded deployment. The FFT provides a practical compromise, reducing the computational burden from to , which is essential in low-power inference environments. Its use in this study enabled real-time spectrogram generation with inference latencies below 50 ms, as demonstrated in Section 3.

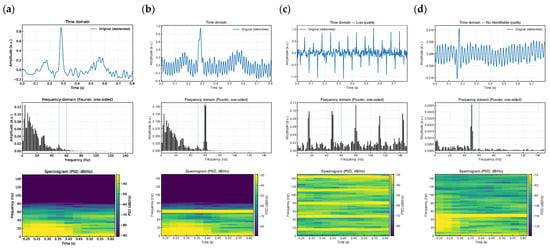

The resulting spectrograms depict the energy distribution across time and frequency, highlighting quality differences in ECG signals. Figure 4a shows a spectrogram from a High-Quality segment; Figure 4b–d illustrate samples from Medium, Low, and Unidentifiable classes, respectively.

Figure 4.

Graphical Representation of the Spectrogram for Each ECG Class. The figure illustrates the time-domain waveform segmented into 0,8 s windows, alongside the frequency spectrum computed using FFT to quantify noise levels for each quality category: (a) High Quality, (b) Medium Quality, (c) Low Quality, and (d) Unidentifiable.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) were implemented to classify the spectrograms generated from the FFT process. CNNs, inspired by the organization of the biological visual cortex, learn spatial and temporal features through convolutional operations, enabling efficient abstraction without the need for manual feature engineering. The implemented model consists of three convolutional blocks followed by fully connected dense layers. Each block contains a 1D convolution with decreasing kernel sizes (7, 5, and 3), followed by batch normalization, LeakyReLU activation (α = 0.1), and max-pooling. The convolution operation for each layer is mathematically expressed in Equation (2):

where and are the learnable weights and bias of layer , and is the output from the previous layer. After the final convolutional block, the output is flattened and passed through two fully connected layers (128 and 64 neurons, respectively) with dropout regularization (rate = 0.5). A softmax layer is used for the final classification across the four ECG quality classes: High, Medium, Low, and Unidentifiable.

The CNN was implemented in Python using TensorFlow and Keras. All spectrograms were normalized to zero mean and unit variance using training set statistics. The dataset consisted of 6242 labeled spectrograms and was split into training (80%), validation (10%), and testing (10%) subsets using stratified sampling. The full training and evaluation workflow is summarized in Algorithm 1. The implemented model consists of three convolutional blocks with decreasing kernel sizes (7, 5, and 3). This design follows a common practice in 1D signal processing for hierarchical feature extraction: the initial larger kernel (7 × 1) captures low-level, broad temporal features (e.g., general wave morphology), while subsequent layers with smaller kernels (5 × 1, 3 × 1) refine the feature maps to identify fine-grained, high-frequency patterns (e.g., sharp QRS peaks).

| Algorithm 1. Algorithm implemented for ECG spectrogram classification |

|

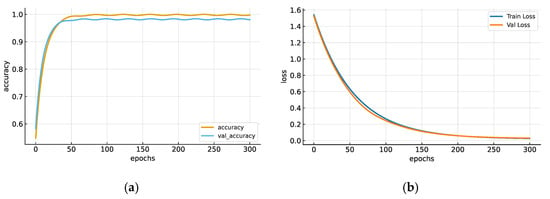

Accuracy refers to the proportion of correctly classified samples relative to the total number of classifications, whereas training accuracy indicates the model’s performance on the training dataset. Figure 5a presents the accuracy trends for both training and validation sets, achieving final accuracies of 0.9968 and 0.9784, respectively. The blue curve denotes training accuracy, while the orange curve represents the validation accuracy. Figure 5b illustrates the loss evolution over 300 epochs, showing convergence between training (Train_loss, blue) and validation (Val_loss, orange) losses, both approaching zero.

Figure 5.

(a) Accuracy trend with training data (accuracy) and validation data (val_accuracy). (b) Graph of the CNN accuracy trend with new data (training loss) and the loss function trend after 300 epochs.

These results validate the stability, convergence, and generalization capacity of the CNN architecture under controlled computational conditions. This section establishes the methodological foundation of the proposed Edge AI framework, combining efficient time–frequency feature extraction through FFT with an optimized CNN model capable of high-precision ECG quality classification. The approach ensures low-latency performance suitable for embedded medical systems compliant with international standards for safety and signal integrity.

3. Results

Model evaluation metrics were calculated, including the confusion matrix, F1-score, and recall. In this context, TP represents true positives, TN true negatives, FN false negatives, and FP false positives. These metrics are defined by the following equations:

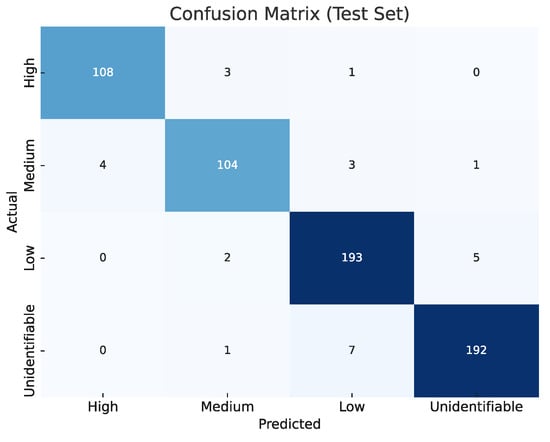

Figure 6 presents the confusion matrix summarizing the CNN model’s performance in the final evaluation. This matrix was calculated using the test set, which consists of 624 spectrograms that the model did not see during the training or validation phases. The matrix axes represent the four signal quality classes: ‘High’, ‘Medium’, ‘Low’, and ‘Unidentifiable’. The vertical axis (‘Actual’) indicates the true label for each sample, while the horizontal axis (‘Predicted’) shows the class predicted by the model. The values on the main diagonal (108, 104, 193, 192) represent the number of correct classifications for each class. The off-diagonal values represent misclassifications. A strong diagonal dominance is observed, indicating high accuracy across all classes. Misclassifications are minimal and primarily occur between adjacent classes (e.g., 7 ‘Unidentifiable’ samples were misclassified as ‘Low’, and 4 ‘Medium’ samples were misclassified as ‘High’). This distribution confirms the model’s robust generalization capability.

Figure 6.

Confusion matrix for the test set, showing raw counts per ECG quality class. Diagonal dominance across all classes (High, Medium, Low, and Unidentifiable) demonstrates the robustness and generalization of the proposed CNN classifier.

The model’s quantitative performance is summarized in Table 2, which reports the classification metrics for each ECG quality class in the test subset. The CNN model achieved consistently high performance across all categories, confirming its strong discriminative capability and balanced behavior between sensitivity and specificity.

Table 2.

Metrics obtained from evaluating the spectrogram validation subset in the implemented CNN.

As shown in Table 2, the High-Quality class achieved an accuracy of 98.72%, precision of 96.43%, and recall of 96.43%, confirming the model’s strong ability to identify high-quality signals with minimal misclassification. The Medium-Quality class reached an accuracy of 97.76% and an F1-score of 93.70%, indicating a balanced but slightly more challenging classification scenario. The Low-Quality class obtained an accuracy of 96.31%, precision of 94.61%, and recall of 96.50%, reflecting reliable detection of signals with degraded characteristics. Finally, the Unidentifiable class achieved an accuracy of 96.31%, the highest precision at 96.97%, and a recall of 96.00%, confirming the model’s robustness in identifying signals unsuitable for clinical interpretation. These updated metrics support the effectiveness of the CNN architecture across all four ECG quality levels in the independent test set, reflecting the network’s stable performance across categories with similar noise patterns. These results demonstrate that the CNN architecture effectively distinguishes between varying levels of ECG signal quality, maintaining both high sensitivity and specificity. The metric distribution supports the quantitative evidence observed in the confusion matrices (Figure 6), confirming that the proposed approach achieved strong generalization and balanced classification behavior across all categories. An analysis of misclassified cases revealed that most errors occurred between adjacent quality levels (for example, Medium signals occasionally misclassified as Low). Such errors are less critical from a diagnostic standpoint since they would typically prompt a repeat acquisition rather than result in misinterpretation. Only a few instances of Low-quality signals classified as Medium suggest minor boundary ambiguities due to synthetic hardware-simulated noise artifacts used in dataset generation.

As illustrated in Figure 5, both the accuracy and loss curves exhibit stable convergence, with minimal divergence between training and validation trends, indicating that CNN achieved high accuracy without overfitting. Overall, the results validate the methodological soundness of the proposed approach and confirm that the CNN effectively quantifies ECG signal quality using simulated spectrogram data. Nevertheless, these results constitute a proof of concept; future work will focus on clinical validation and real-time implementation of embedded systems to evaluate algorithm performance under actual ECG acquisition conditions. The quantification of signal quality at the embedded level is crucial, as high noise levels can significantly impair diagnostic reliability in medical practice.

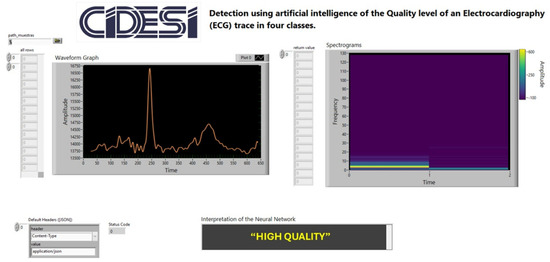

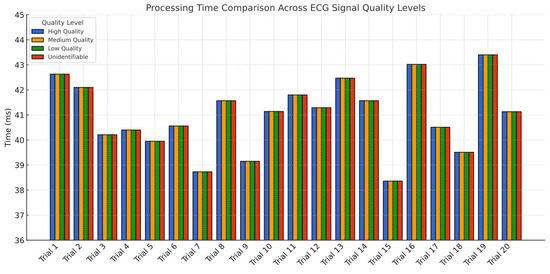

To validate the feasibility of implementing the classification model in clinical environments, a graphical user interface (GUI) was developed using LabVIEW® 2022 Q3 (Figure 7). This interface demonstrates the model’s functionality by communicating with a Python® application via the HTTP protocol, transmitting data from the database to the interface. The results display the desired ECG waveform for spectrogram analysis and real-time interpretation. The experiment, consisting of 20 trials (Table 3), measured the total processing time from the selection of a 12-lead ECG window until the response time was displayed on the interface, achieving an average latency of 40.98 ms with a variability of 5.04 ms (Figure 8). These findings confirm that the proposed methodology is suitable for near real-time applications. After comparing the proposed CNN-based spectrogram approach with traditional SQI and NFB-based methods, the results demonstrate that the model achieves superior sensitivity and specificity, while extending quality assessment from binary to four levels, consistent with clinical practice as implemented in Philips DXL™ systems. In addition, the average latency of ~41 ms confirms the feasibility of near real-time classification across all 12 leads, which is a critical factor for integration into hospital and ambulatory monitoring systems.

Figure 7.

Graphical User Interface Developed in LabVIEW® for Measuring Model Response Latency in ECG Signal Quality Interpretation.

Table 3.

Latency Times Reported by the CNN Model in Interpreting ECG Quality Levels Across Four Classes.

Figure 8.

Bar chart of average model response latency by ECG quality class. All classes exhibited similar latency distributions across 20 trials, with an overall average of 40.98 ms.

To demonstrate the model’s portability, the trained CNN (h5 format) was successfully deployed on an STM32N657x0H microcontroller (STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland). This chip features an Arm® Cortex®-M55 core running at 800 MHz and the proprietary ST Neural-ART™ accelerator (STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland), enabling efficient edge AI execution. Inference times remained consistent with PC-based testing, validating the feasibility of real-time classification under embedded constraints. The deployment used STM32Cube (STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland). AI and CMSIS-NN for quantization and optimization. This confirms that the spectrogram-based CNN model can be integrated directly into biomedical-grade, low-power devices for continuous ECG quality assessment.

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Related Work

Several techniques have been proposed for ECG signal quality classification, including traditional Signal Quality Index (SQI)-based algorithms and more recent spectrogram-driven deep learning models. For example, Ref. [4] introduced four SQI flags to detect issues such as electrode misplacement and high-frequency noise, achieving 90.67% sensitivity and 89.78% specificity. In another study, Ref. [35] applied a vector-cardiogram transformation approach to detect disconnected leads and waveform irregularities, obtaining 97% sensitivity but only 75.1% specificity. More recently, Refs. [21,36] implemented the Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM) to compare standard SQIs with an Image Quality Index (IQI), reaching 93.1% accuracy—surpassing baseSQI (85.7%), kSQI (63.7%), and sSQI (73.8%).

While these methods provide valuable benchmarks, most operate as offline algorithms requiring pre-recorded ECG data, which limits their applicability in real-time monitoring. Spectrogram-based deep learning alternatives, such as the Stockwell Transform approach proposed in [37], achieved notable performance with 97.67% sensitivity using deep-learned features and probabilistic heuristics, though without real-time validation.

The method proposed in this study employs FFT-based spectrograms and a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), demonstrating high average sensitivity (98.08%) and specificity (97.33%) on simulated ECG signals. A distinctive feature of the proposed approach is its ability to perform four-level classification (High, Medium, Low, and Unidentifiable) across all 12 leads—representing an advancement over previous binary classification schemes. Table 4 presents a comparative summary showing that the proposed model achieves performance metrics comparable or superior to other Non-Feature-Based (NFB) methods while also offering near real-time compatibility.

Table 4.

Comparison of reported NFB-based ECG quality assessment methods (results obtained on heterogeneous datasets, not directly comparable).

4.2. Overfitting and Generalization

Avoiding overfitting is critical in medical AI applications. Figure 4 presents the learning curves, where training and validation losses converge consistently with minimal divergence, indicating strong generalization capabilities. The model also performed similarly across the validation and test datasets, confirming robustness even when exposed to unseen samples. Misclassifications were primarily observed between adjacent classes (e.g., Medium vs. Low), suggesting potential overlap in spectral characteristics or labeling ambiguities, particularly for synthetically generated hardware-simulated artifacts. Nevertheless, these errors pose minimal clinical risk as they would likely lead to a repeated acquisition rather than a diagnostic error.

4.3. Embedded Inference Performance

Latency testing across 20 trials (Figure 8, Table 3) revealed a consistent average inference time of ~41 ms, which meets real-time requirements for ECG monitoring applications. The model was successfully deployed on an STM32N657x0H microcontroller, equipped with an Arm® Cortex®-M55 core and ST’s Neural-ART™ accelerator. Inference on embedded hardware produced results equivalent to PC-based predictions, validating the practical feasibility of deploying the model in clinical devices.

The ability to operate with low latency while performing multi-level classification across 12 leads represents a significant advance for real-world applicability. Furthermore, the system supports filtering operations (e.g., baseline wander correction, notch filtering), which are essential for compliance with standards like IEC 60601-2-27 and IEC 60601-2-47. With frameworks such as CMSIS-DSP and LabVIEW® toolchains enabling direct deployment, this approach can be adapted for use in hospital monitors and wearable health systems.

4.4. Limitations and Future Work

We acknowledge certain limitations in our study. While the synthetic ECG data generated via the Fluke PS420 hardware simulator is controlled and reproducible, it naturally cannot fully capture the chaotic variability found in clinical recordings from real patients. Additionally, a formal ablation study to isolate the contribution of each CNN component was not performed, which will be addressed in future work. Although the model was benchmarked on public datasets such as PhysioNet’s CinC11, CinC17, and MIT-BIH, this validation should be regarded as preliminary. These databases, composed of open-access, de-identified data, are standard for methodological validation in AI research and typically exempt from IRB approval. They offer diversity in lead configuration and noise profiles, making them ideal for evaluating model generalization.

However, results from these databases do not replace the need for prospective validation on real patient data. In accordance with TRIPOD and CLAIM guidelines, we intend to develop a prospective, ethically approved protocol involving at least 100 patients. The present work demonstrates technical feasibility and model architecture as a foundation for future clinical studies.

5. Conclusions

The results obtained using the proposed CNN-based spectrogram classification methodology demonstrate performance metrics, particularly sensitivity and specificity, that are comparable to or exceed those of Non-Feature-Based (NFB) algorithms reported in the literature. These findings confirm that mitigating class imbalance and applying multi-level categorization significantly enhance model performance. A major limitation identified in existing research, including this study, is the lack of validation in clinical environments. According to our review, only a few algorithms have been evaluated on real patients, and even in those cases, critical demographic or contextual information is often omitted, making it difficult to generalize the outcomes.

Despite this limitation, the present work offers two distinctive contributions. First, it expands ECG signal quality classification from traditional binary schemes to a four-level framework (High, Medium, Low, Unidentifiable), which is consistent with established clinical devices such as the Philips DXL system. This classification was implemented across all 12 leads using time–frequency spectrograms and a compact CNN architecture, making the approach both scalable and interpretable. Second, the average inference latency of approximately 41 milliseconds demonstrates the feasibility of near real-time operation, which is essential for deployment in hospital and ambulatory monitoring systems. To support future clinical applications, the trained model was successfully deployed on an STM32N657x0H microcontroller equipped with an Arm Cortex-M55 core and the ST Neural-ART accelerator. Inference results obtained from the embedded system were equivalent to those on desktop platforms, confirming the model’s computational efficiency and suitability for low-power, real-time environments. Integration with software ecosystems such as CMSIS-DSP, ANSI C SDKs, and Matlab/Octave code generation tools facilitate implementation on hardware platforms including STM32, ESP32, and RISC-V.

For methodological validation, public ECG datasets such as CinC11, CinC17, and MIT-BIH were employed. These datasets are de-identified, ethically acceptable for secondary use, and provide diverse noise and signal conditions, making them ideal for benchmarking generalization. However, it is important to recognize that these validations are preliminary. In line with TRIPOD and CLAIM recommendations, future work will include the design of a prospective clinical study involving at least 100 patients under approved ethical protocols.

Additionally, hardware-level enhancements such as integrating analog front-end components like the ADS1298, which complies with IEC 60601-2-27 and IEC 60601-2-47 standards, will be explored to ensure signal acquisition reliability and clinical safety. Tools like the Fluke PS420 simulator, in combination with open-access databases, can further improve reproducibility and foster collaborative development.

In conclusion, this study lays a solid foundation for advancing multi-level ECG signal quality classification through embedded artificial intelligence. The proposed methodology demonstrates competitive performance, real-time compatibility, and regulatory potential, contributing meaningfully to the development of robust and accessible cardiovascular monitoring solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: F.D.P.R. and J.A.S.C.; Methodology: F.D.P.R. and L.A.G.R.; Software: F.D.P.R. and L.A.G.R.; Validation: F.D.P.R. and P.A.N.S.; Formal Analysis: F.D.P.R. and P.A.N.S.; Investigation: J.A.S.C.; Data Curation: F.D.P.R.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: F.D.P.R.; Writing—Review and Editing: P.A.N.S.; Visualization: F.D.P.R. and P.A.N.S.; Supervision: J.A.S.C.; Project Administration: P.A.N.S.; Funding Acquisition: P.A.N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by CONAHCYT under project F003- 322623 (LANITEM).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The database used for validating the ECG model for quality level quantification is available at the following link: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1f_8HpKMTml2CkWDEkR97Os7UcWVrFq7c?usp=sharing, (accessed on 25 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Laboratorio Nacional SECIHTI de Investigación y Tecnologías Médicas (LANITEM) for institutional support. Special thanks are extended to Renata F. M. for the technical review and professional human English editing of the manuscript, ensuring high-quality communication of the technical findings, Diego G. E. for the organization and processing of the data, Armando C. for his contribution to the development of the graphical interface, and Lester F. G. for his recommendation of the integrated circuit employed in the embedded AI implementation. The authors declare that no generative AI or AI-assisted technologies were used in the writing, analysis, or interpretation of the scientific content presented in this manuscript. While Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) were developed and utilized as the core methodological approach for signal quality assessment as detailed in the Methods section, the textual composition, literature review, and scientific argumentation of this paper were executed exclusively by the human authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Clifford, G.D.; Azuaje, F.; McSharry, P. Advanced Methods and Tools for ECG Data Analysis; Artech House: London, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-1-58053-966-1. [Google Scholar]

- Campero Jurado, I.; Lorato, I.; Morales, J.; Fruytier, L.; Stuart, S.; Panditha, P.; Janssen, D.M.; Rossetti, N.; Uzunbajakava, N.; Serban, I.B. Signal Quality Analysis for Long-Term ECG Monitoring Using a Health Patch in Cardiac Patients. Sensors 2023, 23, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Liu, D.; Chen, X. Wearable Exercise Electrocardiograph Signal Quality Assessment Based on Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Algorithm. Comput. Commun. 2020, 151, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, L.; Liu, F.; Chen, X.; Yao, Y.; Li, J. Signal Quality Assessment and Lightweight QRS Detection for Wearable ECG SmartVest System. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Xiang, W.; An, Y. Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms for the Quality Assessment of Wearable ECG Signals via Lenovo H3 Devices. J. Med. Biol. Eng. 2021, 41, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, S.; Zhang, L.; Liu, C. Comparing the Performance of Random Forest, SVM and Their Variants for ECG Quality Assessment Combined with Nonlinear Features. J. Med. Biol. Eng. 2019, 39, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, A.; Manikandan, M.S.; Pachori, R.B. Automatic ECG Signal Quality Determination Using CNN with Optimal Hyperparameters for Quality-Aware Deep ECG Analysis Systems. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 17825–17833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, K.; Liu, H.; Long, F.; Chen, L.; Yang, Y. An Automatic ECG Signal Quality Assessment Method Based on ResNet and Self-Attention. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GE Healthcare. Marquette 12SL ECG Analysis Program: Physician’s Guide; GE Healthcare: Waukesha, WI, USA, 2012. Available online: https://landing1.gehealthcare.com/rs/005-SHS-767/images/45351-MUSE-17Nov2022-6-1-Quick-Reference-Guide-LP-Diagnostic-Cardiology.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Philips Medical Systems. Philips PageWriter Trim ECG–Physician Guide; Philips Medical Systems: Andover, MA, USA, 2009. Available online: https://www.documents.philips.com/assets/Instruction%20for%20Use/20250404/4dce4266a3d64303985db2b500dfb2dc.pdf?feed=ifu_docs_feed (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Koninklijke Philips N.V. DXL 16-Lead ECG Algorithm: Technical Overview; Philips: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rajpurkar, P.; Hannun, A.Y.; Haghpanahi, M.; Bourn, C.; Ng, A.Y. Cardiologist-Level Arrhythmia Detection with Convolutional Neural Networks. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, O.; Talo, M.; Ciaccio, E.J.; Tan, R.S.; Acharya, U.R. Accurate Deep Neural Network Model to Detect Cardiac Arrhythmia on More Than 10,000 Individual Subject ECG Records. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020, 197, 105740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Zhou, Y.; Shang, J.; Xiao, C.; Sun, J. Opportunities and Challenges of Deep Learning Methods for Electrocardiogram Data: A Systematic Review. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020, 122, 103801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 60601-2-27; Medical Electrical Equipment—Particular Requirements for Basic Safety and Essential Performance of Electrocardiographic Monitoring Equipment. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- IEC 60601-2-47; Medical Electrical Equipment—Particular Requirements for the Basic Safety and Essential Performance of Ambulatory Electrocardiographic Systems. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- IEC 62304; Medical Device Software—Software Life Cycle Processes. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14971; Medical Devices—Application of Risk Management to Medical Devices. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Good Machine Learning Practice for Medical Device Development: Guiding Principles; FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fluke Biomedical. PS420 Cardiac Rhythm Simulator: Operator’s Manual; Fluke Biomedical: Everett, WA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; Yao, J. A Signal Quality Assessment Method for Electrocardiography Acquired by Mobile Device. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Madrid, Spain, 3–6 December 2018; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, Á.; Martínez-Rodrigo, A.; Puchol, A.; Pachón, M.I.; Rieta, J.J.; Alcaraz, R. Comparison of Pre-Trained Deep Learning Algorithms for Quality Assessment of Electrocardiographic Recordings. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on e-Health and Bioengineering (EHB), Iasi, Romania, 29–30 October 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taji, B.; Chan, A.D.C.; Shirmohammadi, S. Classifying Measured Electrocardiogram Signal Quality Using Deep Belief Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC), Turin, Italy, 22–25 May 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, J.; Blasimme, A.; Vayena, E.; Frey, D.; Madai, V.I. Explainability for Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: A Multidisciplinary Perspective. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2020, 20, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehbani, A.; Sahuguede, S.; Julien-Vergonjanne, A.; Bernard, O. Quality Indexes of the ECG Signal Transmitted Using Optical Wireless Links. Sensors 2023, 23, 4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) Action Plan; FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council. Artificial Intelligence Act; Regulation (EU) 2024/1689; European Parliament and Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yaghmaie, N.; Maddah-Ali, M.A.; Jelinek, H.F.; Mazrbanrad, F. Dynamic Signal Quality Index for Electrocardiogram Signals. Physiol. Meas. 2018, 39, 105008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maji, S.; Burke, M.J. Establishing the Input Impedance Requirements of ECG Recording Amplifiers. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2019, 68, 3370–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arney, D.; Plourde, J.; Goldman, J.M. OpenICE Medical Device Interoperability Platform Overview and Requirement Analysis. Biomed. Tech. 2018, 63, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.; Kadian, T.; Shetty, M.K.; Gupta, A. Explainable AI Decision Model for ECG Data of Cardiac Disorders. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2022, 75, 103584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, L.; Oberdier, M.T.; van Abeelen, K.C.J.; Menghini, L.; Tumarkin, E.; Tripathi, H.; Jaipalli, S.; Orro, A.; Paolocci, N.; Gallelli, I.; et al. Electrocardiogram Monitoring Wearable Devices and Artificial Intelligence: A Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhu, X.; Nakamura, K.; Noro, M. Electrocardiogram Quality Assessment with a Generalized Deep Learning Model Assisted by Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks. Life 2021, 11, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Imtiaz, M.N. Pan-Tompkins++: A Robust Approach to Detect R-Peaks in ECG Signals. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.03171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, Á.; Martínez-Rodrigo, A.; Rieta, J.J.; Alcaraz, R. ECG Quality Assessment via Deep Learning and Data Augmentation. In Proceedings of the 2021 Computing in Cardiology Conference (CinC), Brno, Czech Republic, 13–15 September 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriari, Y.; Fidler, R.; Pelter, M.M.; Bai, Y.; Villaroman, A.; Hu, X. Electrocardiogram Signal Quality Assessment Based on Structural Image Similarity Metric. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 65, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannesen, L.; Galeotti, L. Automatic ECG Quality Scoring Methodology: Mimicking Human Annotators. Physiol. Meas. 2012, 33, 1479–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Han, X.; Tian, L.; Zhou, W.; Liu, H. ECG Quality Assessment Based on Hand-Crafted Statistics and Deep-Learned S-Transform Spectrogram Features. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 208, 106269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).