Featured Application

Quercus acuta Thunb. fruit extract (QA) exhibits strong potential for development as both a therapeutic agent and a functional nutraceutical for the prevention of glucocorticoid-induced muscle atrophy and age-related sarcopenia. Through its dual regulation of catabolic and anabolic pathways, QA represents a safe, plant-derived candidate for pharmaceutical and health-functional applications targeting muscle preservation.

Abstract

Sarcopenia, characterized by the progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass and function, is exacerbated by glucocorticoid exposure. Although there is growing interest in natural therapies for muscle atrophy, the effects of Quercus acuta Thunb. fruit extract (QA) on sarcopenia or glucocorticoid-induced muscle loss had not been previously investigated. QA is an evergreen oak known for its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, with polyphenolic components reported to enhance oxidative and metabolic homeostasis in various tissues. Based on these properties, we hypothesized that QA could counteract muscle atrophy by modulating anabolic and catabolic signaling pathways. The research utilized both in vitro (C2C12 myotubes) and in vivo (ICR mice) models to assess QA’s effects. Daily oral administration of QA (100–200 mg/kg) was given to mice with dexamethasone (Dex)-induced muscle atrophy. Techniques included H&E staining to assess muscle mass and fiber cross-sectional area (CSA), Western blot, and ELISA analyses to investigate signaling pathways. Confocal imaging was also used to confirm cellular changes. In vitro QA treatment improved myotube integrity by increasing myogenic differentiation markers (MyoD, MyoG) and suppressing atrophy-related E3 ligases, specifically MuRF-1 and FBX32/Atrogin-1. Confocal imaging showed that QA inhibited the nuclear localization of FOXO1 and reduced FBX32 expression. In vivo, daily oral administration of QA significantly preserved gastrocnemius muscle mass and fiber cross-sectional area in Dex-treated mice. QA restored the IGF-1/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and attenuated FOXO1-dependent proteolytic activation. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that QA possesses potent anti-atrophic and myoprotective effects mediated through the modulation of the IGF-1/Akt-FOXO axis. QA has potential as a novel natural therapeutic for preventing glucocorticoid-induced sarcopenia.

1. Introduction

Sarcopenia, characterized by the progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength, and function, represents a significant clinical challenge in aging populations and patients receiving glucocorticoid therapy [1,2]. Dexamethasone (Dex), a synthetic glucocorticoid widely used for its anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties, paradoxically induces muscle atrophy through complex molecular mechanisms involving the suppression of anabolic pathways and activation of catabolic processes [3,4].

The pathophysiology of glucocorticoid-induced muscle atrophy involves the dysregulation of key signaling pathways, particularly the insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)/phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt) pathway [5,6]. Under normal physiological conditions, IGF-1 activates PI3K/Akt signaling, which promotes muscle protein synthesis through mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activation and simultaneously inhibits muscle protein degradation by phosphorylating and inactivating forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1) [7,8]. However, glucocorticoid exposure disrupts this anabolic signaling cascade, leading to FOXO1 nuclear translocation and subsequent transcriptional activation of atrophy-related genes, including the E3 ubiquitin ligases muscle RING finger 1 (MuRF-1) and F-box protein 32 (FBX32/Atrogin-1) [9,10].

Recent studies have demonstrated that natural compounds can effectively counteract glucocorticoid-induced muscle atrophy through modulation of these critical signaling pathways. For instance, monotropein has been shown to improve Dex-induced muscle atrophy via the AKT/mTOR/FOXO3a signaling pathways [11]. Similarly, β-sitosterol attenuates dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy by regulating FoxO1-dependent signaling in both C2C12 cells and mouse models [12]. Additionally, quercetin glycosides prevent dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy through Akt pathway activation and myostatin suppression [13].

Quercus acuta Thunb., commonly known as Japanese evergreen oak, is an evergreen tree native to Korea, Japan, and parts of China. The fruit of Q. acuta has been traditionally used in folk medicine and is rich in polyphenolic compounds such as tannins, flavonoids, and other bioactive molecules [14,15]. These polyphenolic constituents have been reported to exhibit potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and metabolic regulatory activities across various biological systems [16,17]. In our previous work, we characterized the chemical profile of Q. acuta fruit extract and identified gallotannic acid and ellagic acid as major polyphenolic constituents using HPLC analysis [18]. Although this extract was previously referred to as QAF, it is denoted as QA throughout the present study for consistency. These polyphenols are well known for their antioxidant and cytoprotective activities, providing a biochemical basis for the biological actions of QA. Furthermore, we previously demonstrated that QA exerts marked protective effects against UVB-induced photoaging in human keratinocytes by modulating ERK/AP-1 signaling, reducing MMP expression, suppressing inflammatory cytokine production, and preserving collagen integrity [18]. Together, the defined polyphenolic composition and established cytoprotective signaling effects of QA support the mechanistic plausibility of its biological efficacy in other stress-related conditions.

The C2C12 mouse myoblast cell line has been widely utilized as a robust in vitro model for studying muscle differentiation, atrophy, and therapeutic interventions [19]. These cells differentiate into multinucleated myotubes that express muscle-specific proteins, making them an ideal system for investigating molecular mechanisms underlying muscle wasting and potential protective strategies [20,21]. Numerous natural compounds have been shown to promote myogenic differentiation by upregulating key transcription factors such as MyoD and myogenin (MyoG), while concurrently suppressing atrophy-related gene expression [22,23].

Despite the promising therapeutic potential of plant-derived polyphenols in mitigating muscle atrophy, the specific effects of QA on glucocorticoid-induced muscle wasting have not been explored. Given the rich polyphenolic composition of QA, its established biological activities, and demonstrated cytoprotective properties in our previous work [18], we hypothesized that QA may exert myoprotective effects through modulation of the IGF-1/Akt-FOXO1 signaling axis. As oxidative stress and inflammatory responses represent shared pathological mechanisms between UVB-induced cellular damage and glucocorticoid-induced muscle atrophy, QA’s known protective actions provide a strong rationale for investigating its efficacy in muscle homeostasis.

Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to evaluate the myoprotective potential of QA in both in vitro C2C12 myotube models and in vivo Dex-induced muscle atrophy models in ICR mice. We examined the effects of QA on muscle fiber morphology, myogenic differentiation markers, atrophy-related protein expression, and key signaling pathways associated with muscle maintenance. To our knowledge, no previous study has examined the effects of QA on glucocorticoid-induced muscle atrophy, making this work the first to suggest a link between QA and modulation of the IGF-1, Akt, FOXO axis in sarcopenia-related models. Collectively, our findings provide novel insights into the therapeutic potential of QA as a natural intervention for preventing and managing glucocorticoid-induced skeletal muscle loss.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Quercus acuta Thunb. Fruit Extract

Q. acuta fruits were collected from the Wando Arboretum, Jeollanam-do, Korea, and the extract was prepared under the same extraction conditions as described in our previous study [18]. Briefly, dried fruits (1000 g) were extracted with 20 L of distilled water at 100 °C for 4 h using a reflux extractor(N-1000V-W, Tokyo Rikakikai Co., Ltd. (Eyela), Tokyo, Japan), filtered, concentrated under reduced pressure, and freeze-dried to yield a powdered extract, which was stored at 4 °C until use.

2.2. Cell Culture and In Vitro Experiments

C2C12 mouse myoblast cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured according to standard protocols. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco) at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere using a CO2 incubator (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

For differentiation experiments, C2C12 myoblasts were seeded in 6-well plates and allowed to reach 80–90% confluence. Differentiation was induced by replacing the growth medium with DMEM containing 2% horse serum (Gibco). After 5–7 days of differentiation, myotubes were treated with various concentrations of QA (0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, and 10 µg/mL) for 24 h, with or without dexamethasone (10 µM; D4902, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to induce muscle atrophy.

The 24 h co-treatment duration was chosen based on preliminary time course observations indicating that 48 h and 72 h exposures produced similar qualitative trends but resulted in reduced myotube stability and increased culture variability. Therefore, 24 h was selected as the optimal and reproducible window for evaluating QA mediated effects.

2.3. Cell Viability Assay

Cell viability was assessed using the MTS (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium) assay (MTS; Promega, Madison, WI, USA). C2C12 myoblasts were treated with various concentrations of QA for 24 h, and cell viability was measured according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Results were expressed as a percentage of control.

2.4. Animal Experiments

Male ICR mice (8–10 weeks old, 25–30 g) were obtained from a certified supplier and housed under standard laboratory conditions (12 h light/dark cycle, 22 ± 2 °C, 50–60% humidity). All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chosun University (Approval No. CIACUC2025-A0023) and conducted in accordance with its ethical guideline.

Mice were randomly divided into four groups (n = 4–6 per group): (1) Control group (vehicle treatment), (2) Dexamethasone group (Dex, 10 mg/kg/day, i.p.), (3) Dex + QA 100 mg/kg group, and (4) Dex + QA 200 mg/kg group. Dexamethasone was administered intraperitoneally for 14 days, while QA was administered orally via gavage. Body weight and food intake were monitored daily throughout the experimental period.

The doses of QA (100 and 200 mg/kg) were selected based on previous reports showing effective and non-toxic oral administration of Quercus species extracts in rodent models [14,16], as well as our prior chemical characterization studies demonstrating high polyphenolic safety profiles. These doses were therefore considered appropriate to evaluate physiological efficacy without inducing adverse effects [17].

2.5. Histological Analysis

At the end of the experimental period, gastrocnemius muscles were harvested, weighed, and processed for histological analysis. Muscle tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5 µm thickness. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for morphological assessment.

Muscle fiber cross-sectional area (CSA) was measured using ImageJ software (Version 1.54r; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). At least 300 muscle fibers per sample were analyzed, and CSA frequency distribution was calculated to assess changes in fiber size distribution.

2.6. Western Blot Analysis

Protein lysates were prepared from gastrocnemius muscle tissues and C2C12 cells using RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Equal amounts of protein (30–50 µg) were separated by SDS–PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA).

Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: phospho-Akt (Ser473, #4060; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), total Akt (#9272; Cell Signaling Technology), Phospho-FoxO1 (Thr24)/FoxO3a (THR32, #9464; Cell Signaling Technology), total FOXO3α (#12829; Cell Signaling Technology), FBX32 (#ab168372; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), MuRF-1 (C-2; sc-398608, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), and GAPDH (#2118; Cell Signaling Technology).

After washing, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology) for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (SuperSignal™ West Pico PLUS, #34580; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and quantified by densitometry using ImageJ software (Version 1.54r; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.7. Immunofluorescence Microscopy

C2C12 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and blocked with 5% goat serum. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies against FOXO1 and FBX32 overnight at 4 °C, followed by fluorescent secondary antibodies. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Images were captured using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Nexcope NIB610FL, Ningbo Yongxin Optics Co., Ltd., Ningbo, Zhejiang, China) at 20× and 40× magnification.

2.8. ELISA Analysis

Serum samples were collected from mice after overnight fasting. Serum concentrations of IGF-1 and myostatin (GDF-8) were measured using commercially available ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All samples were analyzed in triplicate, and results were adjusted for dilution factors.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using JASP software (version 0.19.3; University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

3. Results

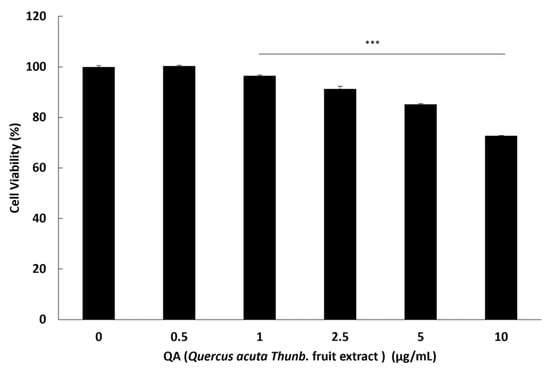

3.1. QA Maintains C2C12 Myoblast Viability and Does Not Exhibit Cytotoxicity

To establish a non-toxic concentration range for use in subsequent in vitro experiments, we first assessed the effects of QA on C2C12 myoblast viability using the MTS assay. QA treatment maintained >80–90% viability up to 5 µg/mL, with no statistically significant reduction compared with the control group (Figure 1). However, a marked reduction in viability was observed at 10 µg/mL, where viability dropped below the threshold for non-cytotoxicity. Based on these findings, QA concentrations ≤ 5 µg/mL were selected for all subsequent experiments. In addition, treatment with dexamethasone (10 µM), which was used for in vitro atrophy induction, did not induce cytotoxicity or impair myotube formation, as confirmed by morphological assessment (Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Protective effect of QA on C2C12 myoblast viability. C2C12 myoblasts were incubated with various concentrations of QA: 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, and 10 μg/mL for 24 h. Cell viability was assessed using the MTS assay, and results were expressed as the percentage of control (mean ± SEM; n = 3). Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test *** p < 0.001.

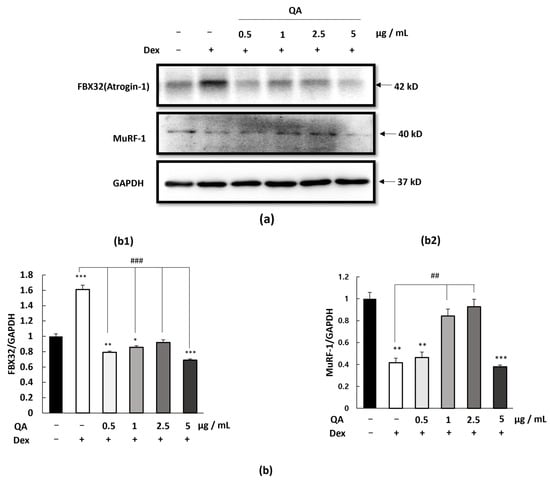

3.2. QA Suppresses Dexamethasone-Induced Expression of Atrophy-Related E3 Ubiquitin Ligases

The ubiquitin-proteasome system plays a crucial role in muscle protein degradation during atrophy, with FBX32 (Atrogin-1) and MuRF-1 serving as key E3 ubiquitin ligases [24,25].

To investigate QA’s effects on muscle protein degradation pathways, we examined the expression of these atrophy-related proteins in C2C12 myotubes. Western blot analysis revealed that dexamethasone treatment significantly increased both FBX32 and MuRF-1 protein expression compared to control cells (Figure 2a,b). However, co-treatment with QA dose-dependently suppressed the dexamethasone-induced up-regulation of both E3 ligases. Specifically, QA at concentrations of 5 µg/mL significantly reduced FBX32 expression. Similarly, MuRF-1 expression was reduced at the same QA concentrations. These findings suggest that QA can effectively counteract glucocorticoid-induced activation of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, thereby potentially preserving muscle protein content.

Figure 2.

Effect of QA on atrophy-related protein expression in C2C12 myotubes. C2C12 myotubes were treated with QA at concentrations of 0.5, 1, 2.5, and 5 μg/mL for 24 h. (a) Protein expression levels of FBX32 (Atrogin-1) and MuRF-1 were determined by Western blotting. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping protein. (b) The intensity of the protein level was normalized against the internal control GAPDH, (b1) FBX32, and (b2) MuRF-1. Data are presented as (mean ± SEM; n = 3). Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. control group ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 vs. DEX-treated group.

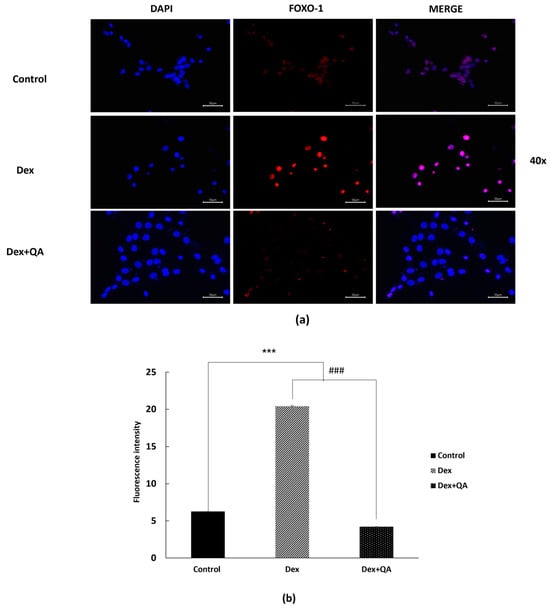

3.3. QA Attenuates FOXO1 Nuclear Enrichment and Reduces Catabolic Gene Expression

FOXO1 acts as a key transcription factor regulating atrophy-related genes such as FBX32 when enriched within the nucleus [26,27]. To explore whether QA-mediated suppression of E3 ligases may involve modulation of FOXO1 distribution, we performed immunofluorescence imaging to visualize FOXO1 localization patterns in C2C12 cells. Dexamethasone treatment produced an apparent increase in FOXO1 signal within the nuclear region, as suggested by greater overlap with DAPI-stained nuclei (Figure 3a). Lower-magnification images are provided in (Figure S3a).

Figure 3.

Qualitative visualization of FOXO1 distribution in Dex-treated C2C12 myotubes and the modulatory effects of QA. Differentiated C2C12 myotubes were treated with Dex (10 μM, 24 h) with or without QA (5 μg/mL). Cells were fixed and immunostained with an anti-FOXO1 antibody (Alexa Fluor 594, red) and counterstained with DAPI (blue). (a) Representative high-magnification fluorescence images (40×) are shown. Dex treatment produced an apparent increase in FOXO1 signal within the nuclear region, whereas QA co-treatment visibly reduced this Dex-associated nuclear enrichment. (b) Quantitative fluorescence analysis of FOXO1 signal within the nuclear area is shown on the right and supports the qualitative trend observed in panel (a). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3). Scale bars = 50 μm. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. *** p < 0.001 vs. control; ### p < 0.001 vs. Dex.

In contrast, QA co-treatment yielded a visibly reduced nuclear FOXO1 signal with comparatively stronger cytoplasmic distribution. This qualitative observation was supported by the accompanying fluorescence intensity analysis showing decreased FOXO1 signal within the nuclear area (Figure 3b). While ICC imaging provides supportive visualization rather than definitive mechanistic evidence, these findings collectively indicate that QA diminishes dexamethasone-associated FOXO1 nuclear enrichment, thereby reducing downstream activation of catabolic genes such as FBX32.

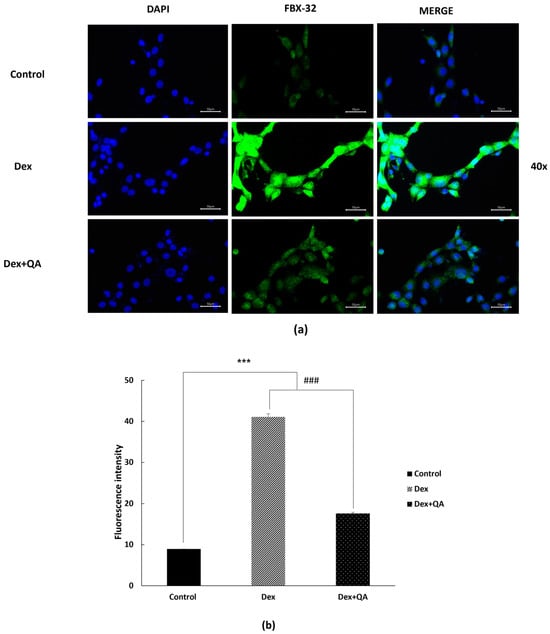

3.4. QA Enhances Myogenic Differentiation Markers in C2C12 Myotubes

In addition to suppressing catabolic pathways, effective myoprotective agents should also promote anabolic processes, including myogenic differentiation and muscle protein synthesis [28,29].

To evaluate the effects of QA on catabolic signaling, we assessed the expression levels of the atrophy-related protein FBX32 (Atrogin-1) in differentiated C2C12 myotubes using immunofluorescence microscopy. As shown in (Figure 4a,b), dexamethasone treatment markedly increased FBX32 fluorescence intensity. Representative 20× images are provided in (Figure S3b).

Figure 4.

QA attenuates Dex-induced FBX32 expression in differentiated C2C12 myotubes. Differentiated C2C12 myotubes were treated with Dex (10 μM, 24 h) with or without QA (5 μg/mL). Cells were fixed and immunostained with an anti-FBX32 antibody (Alexa Fluor 488, green) and counterstained with DAPI (blue). (a) Representative high-magnification fluorescence images (40×) are shown. Dex treatment produced a noticeable increase in FBX32 fluorescence intensity, whereas QA co-treatment visibly reduced this Dex-associated elevation. (b) Quantitative fluorescence intensity analysis supports the qualitative trend observed in panel (a) and shows that QA reduced Dex-induced FBX32 expression. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3). Scale bars = 50 μm. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. *** p < 0.001 vs. control; ### p < 0.001 vs. Dex.

In contrast, QA co-treatment (5 µg/mL) visibly reduced overall FBX32 fluorescence within the cells. Consistently, quantitative fluorescence analysis confirmed that FBX32 intensity was significantly lower in the QA-treated group than in the dexamethasone group (Figure 4b). Because FBX32 is a cytoplasmic E3 ubiquitin ligase, these ICC results reflect changes in relative expression levels rather than subcellular redistribution.

Together, these findings indicate that QA suppresses the glucocorticoid-induced elevation of FBX32 and mitigates the catabolic response, thereby contributing to the preservation of cellular integrity.

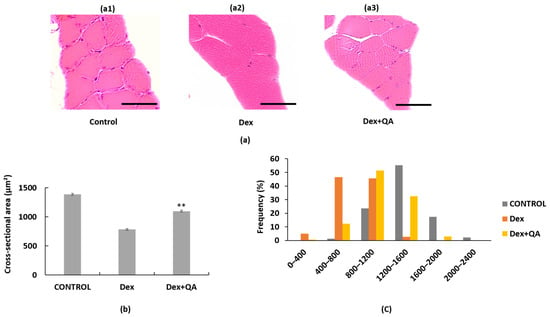

3.5. QA Preserves Muscle Mass and Fiber Cross-Sectional Area in Dexamethasone-Treated Mice

To validate the in vitro findings and assess the therapeutic potential of QA in vivo, we employed a well-established mouse model of dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy [30,31].

Before assessing muscle morphology, general physiological status was evaluated through daily monitoring of body weight and food intake. Dexamethasone-treated mice showed a progressive reduction in body weight, whereas QA co-treatment partially attenuated this decline. No significant differences in food intake were observed among groups throughout the 14-day period. As shown in Figure S2, these physiological patterns confirm that the muscle-specific effects observed in the present study were not attributable to nutritional or systemic behavioral changes.

ICR mice received daily intraperitoneal injections of Dex (10 mg/kg) for 14 days, with or without concurrent oral QA administration (200 mg/kg). Histological analysis of gastrocnemius muscle sections revealed that Dex treatment caused significant muscle atrophy, as evidenced by reduced muscle fiber size and altered fiber size distribution (Figure 5a–c). Control mice displayed a normal distribution of muscle fiber cross-sectional areas (CSA), with most fibers ranging from 1200 to 1600 µm2. In contrast, Dex-treated mice exhibited a marked shift toward smaller fiber sizes, showing an increased frequency of fibers in the 400–800 µm2 range and a reduced proportion of larger fibers. Co-treatment with QA significantly ameliorated Dex-induced muscle atrophy, restoring the frequency distribution of muscle fiber sizes toward that of the control pattern, with a higher representation of larger fibers (1200–1600 µm2) and fewer small fibers. Quantitative analysis showed that QA treatment increased the mean muscle fiber CSA by approximately 30% compared with the dexamethasone-only group, indicating a substantial recovery of muscle morphology.

Figure 5.

Effects of Quercus acuta fruit extract on gastrocnemius muscle morphology and fiber size distribution in Dex-treated mice. (a) Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained gastrocnemius muscle sections from (a1) Control, (a2) Dex (15 mg/kg/day, 14 days), and (a3) Dex + QA (200 mg/kg/day) groups. Dex treatment induced noticeable reductions in fiber cross-sectional area (CSA), whereas QA co-treatment partially preserved overall fiber size. Scale bar = 50 μm (40×). (b) Quantification of mean CSA values (μm2). For each mouse, approximately 300 individual fibers were analyzed, and the mean CSA per mouse was treated as one biological replicate (n = 5 mice per group). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. (c) CSA frequency distribution (%) showing the proportion of small (<800 μm2) and large (>1200 μm2) fibers across groups. Dex administration shifted the distribution toward smaller fibers, while QA co-treatment restored the relative frequency of mid to large fibers. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test ** p < 0.01 was considered statistically significant compared with the Dex group.

3.6. QA Modulates Serum Biomarkers of Muscle Homeostasis

To further characterize QA’s effects on muscle homeostasis, we measured serum concentrations of key regulatory factors involved in muscle growth and atrophy. Myostatin (GDF-8) is a negative regulator of muscle growth, while IGF-1 promotes muscle anabolism [32,33].

ELISA analysis revealed that dexamethasone treatment significantly increased serum myostatin concentrations by 242% compared to control mice (Table 1). This elevation in myostatin levels is consistent with the catabolic state induced by glucocorticoid exposure. However, co-treatment with QA at both 100 and 200 mg/kg doses significantly reduced serum myostatin levels by approximately 28% compared to the Dex only group, indicating suppression of this catabolic factor.

Table 1.

Serum GDF-8 (Myostatin) concentrations in dexamethasone-treated mice and the effects of QA.

Conversely, dexamethasone treatment caused a modest, non-significant reduction in serum IGF-1 levels compared with control mice (Table 2). QA co-treatment partially restored this decrease, with the 100 mg/kg and 200 mg/kg doses increasing IGF-1 by approximately 13% and 19% relative to the Dex group, respectively. Although IGF-1 levels in the QA 200 mg/kg group appeared slightly higher than those of the control group, this difference was not statistically significant and remained within the expected range of normal physiological variability. These observations suggest that QA shifts the anabolic catabolic balance toward a more favorable state without inducing aberrant hormonal elevation.

Table 2.

Serum IGF-1 concentrations in DEX-treated mice and the effect of QA.

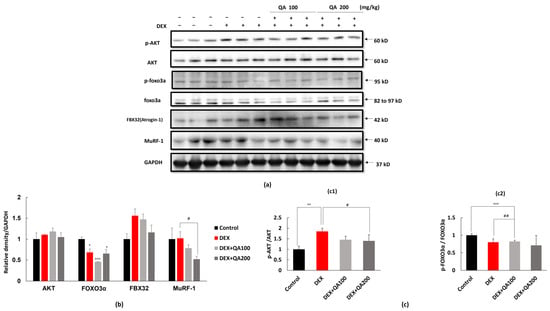

3.7. QA Restores IGF-1/Akt-FOXO3α Signaling in Dexamethasone-Treated Mice

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying QA’s myoprotective effects, we examined key proteins in the IGF-1/Akt-FOXO signaling pathway in gastrocnemius muscle tissues from treated mice [34,35]. This pathway is critical for maintaining the balance between muscle protein synthesis and degradation.

Western blot analysis revealed that dexamethasone treatment significantly suppressed Akt phosphorylation (Ser473), as indicated by a reduced p-Akt/total Akt ratio (Figure 6a–c). This reduction in Akt activity was accompanied by decreased FOXO3α phosphorylation (Ser253), leading to FOXO3α activation and nuclear translocation. Consequently, the expression of downstream atrophy-related proteins FBX32 and MuRF-1 was significantly increased in Dex-treated mice.

Figure 6.

Effects of QA on Akt–FOXO3α signaling and atrophy-related proteins in DEX-treated ICR mice. (a) Representative Western blot images of phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt), total Akt, phosphorylated FOXO3α (p-FOXO3α), total FOXO3α, FBX32 (atrogin-1), and MuRF-1 in gastrocnemius muscle lysates from ICR mice. Mice were administered DEX (10 mg/kg/day, i.p. for 14 days), with or without oral QA treatment (100 or 200 mg/kg/day). GAPDH served as the internal loading control. (b) Densitometric quantification of total Akt, FOXO3α, FBX32, and MuRF-1 protein levels normalized to GAPDH. DEX treatment increased FBX32 and MuRF-1 expression, whereas QA co-treatment dose dependently reduced the levels of these atrogenes. (c) Quantification of phosphorylation ratios (c1) p-Akt/Akt and (c2) p-FOXO3α/FOXO3α. QA significantly restored DEX-suppressed Akt phosphorylation and prevented the DEX-induced decline in p-FOXO3α/FOXO3α, indicating attenuated FOXO3α nuclear activity and reduced transcriptional activation of atrophy-related genes. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3 mice per group). Statistical comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. Control; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01 vs. DEX.

QA co-treatment effectively restored the IGF-1/Akt-FOXO3α signaling pathway in a dose-dependent manner. Both QA doses (100 and 200 mg/kg) significantly increased the p-Akt/Akt ratio compared to the Dex only group, with the higher dose showing greater efficacy. Correspondingly, QA treatment increased FOXO3α phosphorylation, indicating enhanced inactivation of this pro-atrophic transcription factor.

The restoration of Akt-FOXO3α signaling was associated with significant suppression of atrophy-related protein expression. QA treatment dose-dependently reduced FBX32 expression in 100 mg/kg and 200 mg/kg compared to the Dex only group. Similarly, MuRF-1 expression at the respective QA doses.

These findings demonstrate that QA’s myoprotective effects are mediated through the restoration of IGF- 1/Akt signaling and subsequent inhibition of FOXO-dependent catabolic gene expression, providing a mechanistic basis for its therapeutic potential in glucocorticoid-induced muscle atrophy.

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrates for the first time that QA possesses significant myoprotective properties against dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy through modulation of the IGF-1/Akt-FOXO1 signaling axis. Our comprehensive in vitro and in vivo investigations reveal that QA effectively counteracts glucocorticoid-induced muscle wasting by simultaneously suppressing catabolic pathways and enhancing anabolic processes.

The IGF-1/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway serves as a critical regulator of muscle mass homeostasis, promoting protein synthesis while inhibiting protein degradation [36,37]. Our findings demonstrate that QA treatment effectively restores Akt phosphorylation in dexamethasone-treated mice, consistent with recent studies showing that SIRT6 inhibition protects against glucocorticoid-induced skeletal muscle atrophy by regulating IGF/PI3K/AKT signaling [38]. This restoration of Akt activity is crucial for maintaining muscle mass, as activated Akt promotes mTOR-mediated protein synthesis and simultaneously phosphorylates FOXO transcription factors, leading to their nuclear exclusion and inactivation [36,39].

The suppression of FOXO1 nuclear translocation by QA treatment represents a key mechanism underlying its myoprotective effects. FOXO1 serves as a master regulator of muscle atrophy, controlling the transcription of atrophy-related genes, including the E3 ubiquitin ligases FBX32/Atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 [40,41]. Although our ICC imaging provides clear qualitative evidence of Dex-induced FOXO1 nuclear enrichment and its attenuation by QA, we acknowledge that definitive confirmation of nuclear translocation typically requires confocal imaging or nuclear/cytosolic fraction Western blotting. These experiments were beyond the scope of the present study, and we have clarified this as a methodological limitation.

Our ICC results nonetheless demonstrate a consistent pattern in which QA prevents Dex-induced FOXO1 nuclear accumulation, thereby suppressing transcriptional activation of catabolic genes. This mechanism aligns with previous reports, such as β-sitosterol, which attenuates dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy by regulating FOXO1-dependent signaling in both C2C12 cells and mouse models [12].

The myoprotective effects of QA align with those observed for other natural compounds that target similar signaling pathways. For instance, monotropein has been shown to improve dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy via the AKT/mTOR/FOXO3a signaling pathways, with effects on both C2C12 myotubes and mouse models [11]. Similarly, quercetin glycosides prevent dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy in mice by suppressing myostatin expression and reducing atrogene mRNA levels while increasing Akt phosphorylation [13]. The consistency of these findings across different natural compounds suggests that the IGF-1/Akt-FOXO axis represents a common and effective target for natural product-based interventions in muscle atrophy. Our study extends these findings by demonstrating that QA not only suppresses catabolic pathways but also enhances myogenic differentiation markers MyoD and MyoG. This dual action is particularly important for comprehensive muscle protection, as effective therapeutic interventions should address both protein degradation and protein synthesis pathways [42,43]. The enhancement of myogenic markers by QA is consistent with studies on Yuja peel extract, which upregulated MyoD, MyoG, and myosin heavy chain expression via PI3K-Akt-mTOR/FoxO3α pathway modulation in C2C12 cells [23,44].

The modulation of serum myostatin and IGF-1 levels by QA treatment provides additional evidence for its systemic effects on muscle homeostasis. Myostatin (GDF-8) is a potent negative regulator of muscle growth that is typically upregulated during muscle atrophy [23,45]. Our finding that QA significantly reduces serum myostatin levels is consistent with studies on quercetin glycosides, which also suppressed myostatin expression in dexamethasone-treated mice [13]. The concurrent increase in serum IGF-1 levels further supports QA’s ability to promote a favorable anabolic environment for muscle preservation. Serum biomarker analyses were performed in a subset of three animals per group due to sample availability, which should be considered when interpreting these data. Importantly, although IGF-1 levels in the QA 200 mg/kg group exceeded those of control animals, the magnitude of this increase remained within physiological limits. This pattern is consistent with the metabolic-regulatory actions of polyphenol-rich extracts, suggesting that QA enhances anabolic signaling without inducing excessive or pathological IGF-1 overproduction.

The demonstrated efficacy of QA in preventing glucocorticoid-induced muscle atrophy has important clinical implications. Glucocorticoids are widely prescribed for various inflammatory and autoimmune conditions, but their long-term use is often limited by adverse effects, including muscle wasting and sarcopenia [46,47]. The development of effective interventions to prevent or mitigate these side effects would significantly improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

The use of natural compounds like QA offers several potential advantages over synthetic pharmaceuticals, including better safety profiles, reduced risk of drug interactions, and potential additional health benefits from their polyphenolic constituents [48,49]. The rich polyphenolic content of QA likely contributes to its myoprotective effects through multiple mechanisms, including antioxidant activity, anti-inflammatory effects, and direct modulation of signaling pathways involved in muscle homeostasis [16,17]. Our previous research demonstrated that Quercus acuta fruit extract effectively modulates key cellular signaling pathways, including ERK and AP-1, while providing potent cytoprotective effects against oxidative stress [50]. These established properties support the plausibility of QA’s myoprotective mechanisms observed in the current study, as both photoaging and muscle atrophy involve common pathophysiological processes, including oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, and dysregulated protein homeostasis.

While our study provides compelling evidence for QA’s myoprotective effects, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the specific bioactive compounds responsible for QA’s effects have not been fully characterized. Future studies should focus on identifying and isolating the key active constituents to enable standardization and optimization of therapeutic formulations. Second, this study used only male ICR mice, which limits the generalizability of our findings. Male mice were selected because glucocorticoid-induced muscle atrophy develops more rapidly and consistently in males, allowing clearer detection of treatment effects within a restricted experimental window. However, we fully recognize that sex specific differences in hormonal milieu, glucocorticoid responsiveness, and muscle metabolism may influence QA’s efficacy. Future studies will therefore include female mice, particularly hormone-related models such as ovariectomy-induced estrogen deficiency and menopausal hot-flush-associated muscle alterations, to determine whether QA exerts comparable protective effects under different hormonal conditions. Additionally, although dexamethasone and QA co-treatments were evaluated for up to 72 h in preliminary observations, extended incubation resulted in diminished myotube integrity and increased culture variability. Therefore, a 24 h co-treatment window was selected as the most reliable and reproducible condition for mechanistic evaluation. Future studies employing stabilized long-term culture systems may further clarify the temporal dynamics of QA-mediated protection. Third, the long-term safety and efficacy of QA treatment require further investigation through extended studies and clinical trials. Additionally, the mechanisms underlying QA’s effects on IGF-1 production and myostatin regulation warrant further investigation. Although Akt-inhibition assays (such as MK-2206) would provide more direct evidence for pathway specificity, these mechanistic blockade experiments were not included in the present study due to feasibility constraints. Nonetheless, we fully agree that defining Akt dependency is an important next step, and Akt-inhibitor–based mechanistic studies are planned in our future work to more definitively validate the IGF-1/Akt–Akt-FOXO axis underlying QA’s myoprotective effects. While our study demonstrates that QA modulates serum levels of these factors, the specific tissues and cellular pathways involved in this regulation remain to be elucidated. Future research should also explore the potential synergistic effects of QA with other therapeutic interventions, such as exercise training or nutritional supplementation, which are commonly used in the management of sarcopenia.

Based on our findings, we propose a mechanistic model for QA’s myoprotective effects. In this model, dexamethasone treatment suppresses IGF-1/PI3K/Akt signaling, leading to FOXO1 activation and nuclear translocation. Nuclear FOXO1 then promotes the transcription of atrophy-related genes, including FBX32 and MuRF-1, resulting in enhanced protein degradation and muscle atrophy. QA intervention restores IGF-1 signaling and Akt phosphorylation, leading to FOXO1 phosphorylation and cytoplasmic retention. This prevents the transcriptional activation of catabolic genes while promoting the expression of myogenic differentiation factors, ultimately preserving muscle mass and function.

Taken together, these findings suggest that QA mitigates Dex-induced muscle atrophy through coordinated regulation of the IGF-1/Akt/FOXO axis and suppression of GDF-8–mediated catabolic signaling. A schematic summary of the proposed mechanism is provided in (Figure S4).

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that Quercus acuta Thunb. fruit extract (QA) possesses potent myoprotective effects against dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy through modulation of the IGF-1/Akt-FOXO1 signaling axis. The extract effectively suppresses the expression of atrophy-related E3 ubiquitin ligases, prevents FOXO1 nuclear translocation, enhances myogenic differentiation markers, and preserves muscle fiber morphology in both in vitro and in vivo models. These findings provide strong evidence for the therapeutic potential of QA as a natural intervention for preventing and managing glucocorticoid-induced sarcopenia.

The comprehensive nature of QA’s effects, including the suppression of catabolic pathways, enhancement of anabolic processes, and favorable modulation of serum biomarkers, positions it as a promising candidate for further development as a nutraceutical or pharmaceutical intervention. These results, combined with our previous demonstration of QA’s cytoprotective properties against UVB-induced photoaging [18], establish QA as a versatile bioactive natural product with broad therapeutic potential across multiple pathological conditions involving oxidative stress and cellular dysfunction. Future clinical studies are warranted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of QA in human subjects and to establish optimal dosing regimens for therapeutic applications in both muscle-related disorders and other age-related degenerative conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152412978/s1, Figure S1: Effects of Dex (10 µM) on C2C12 Myotube Viability and Morphology. (a) Phase-contrast image of C2C12 myotubes treated with Dex (10 μM) for 24–48 h, showing preserved myotube structure without overt cytotoxicity. (b) Representative image showing that Dex-treated myotubes maintain multinucleated morphology and alignment comparable to vehicle-treated cells. Scale bar = 50 μm (20×); Figure S2: Body weight changes in DEX- and QA-treated mice during the 14-day experimental period.; Figure S3: Lower-magnification (20×) fluorescence images corresponding to FOXO1 (Figure 3) and FBX32 (Figure 4) immunostaining in differentiated C2C12. (a) Representative 20× fluorescence images for FOXO1 staining (Control, Dex, Dex QA), shown as DAPI, FOXO1, and merged channels. (b) Representative 20× fluorescence images for FBX32 staining under the same experimental conditions; Figure S4: Proposed mechanisms of Dex-induced atrophy and QA-mediated protection. (a) Dex reduces IGF-1 and p-Akt while increasing GDF-8, activating FOXO and inducing FBX32/MuRF1 to promote muscle atrophy. (b) QA increases IGF-1 and decreases GDF-8, enhancing Akt activity, suppressing FOXO, lowering FBX32/MuRF1, and protecting myotubes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-Y.C.; data curation, D.-I.C.; formal analysis, H.L. and D.B.; investigation, D.-I.C. and S.H.; resources, D.-I.C. and C.-Y.C.; methodology, D.-I.C. and H.L.; software, H.L. and D.B.; writing—original draft preparation, D.-I.C.; supervision, C.-Y.C., S.H. and J.-A.H.; writing—review and editing, J.-A.H. and C.-Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was conducted with the support of the R&D program for Forest Science Technology project no. RS-2023-KF002467 provided by Korea Forest Service (Korea Forestry Promotion Institute).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chosun University (approval no. CIACUC2025-A0023, approved on 18 June 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to institutional policy and ongoing related research.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the R&D Program for Forest Science Technology (Project No. RS-2023-KF002467) provided by the Korea Forestry Promotion Institute and by the Global-Learning & Academic Research Institution for Master’s·PhD students, and Postdocs (LAMP) Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (No. RS-2023-00285353). The authors also thank the members of the Well-Aging Medicare Research Institute for their valuable technical and administrative support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudart, C.; Zaaria, M.; Pasleau, F.; Reginster, J.Y.; Bruyère, O. Health outcomes of sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, K.; Genma, R.; Gotou, Y.; Nagasaka, S.; Fukada, S.I. Three-Dimensional Culture Model of Skeletal Muscle Tissue with Atrophy Induced by Dexamethasone. Bioengineering 2017, 4, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umeki, D.; Ohnuki, Y.; Mototani, Y.; Shiozawa, K.; Suita, K.; Fujita, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Saeki, Y.; Okumura, S.; Ishikawa, Y. Protective Effects of Clenbuterol against Dexamethasone-Induced Masseter Muscle Atrophy and Myosin Heavy Chain Transition. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodine, S.C.; Stitt, T.N.; Gonzalez, M.; Kline, W.O.; Stover, G.L.; Bauerlein, R.; Zlotchenko, E.; Scrimgeour, A.; Lawrence, J.C.; Glass, D.J.; et al. Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle atrophy in vivo. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001, 3, 1014–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandri, M.; Sandri, C.; Gilbert, A.; Skurk, C.; Calabria, E.; Picard, A.; Walsh, K.; Schiaffino, S.; Lecker, S.H.; Goldberg, A.L. Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy. Cell 2004, 117, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stitt, T.N.; Drujan, D.; Clarke, B.A.; Panaro, F.; Timofeyva, Y.; Kline, W.O.; Gonzalez, M.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; Glass, D.J. The IGF-1/PI3K/Akt pathway prevents expression of muscle atrophy-induced ubiquitin ligases by inhibiting FOXO transcription factors. Mol. Cell 2004, 14, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, D.J. Signaling pathways perturbing muscle mass. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2010, 13, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.D.; Lecker, S.H.; Jagoe, R.T.; Navon, A.; Goldberg, A.L. Atrogin-1, a muscle-specific F-box protein highly expressed during muscle atrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 14440–14445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodine, S.C.; Latres, E.; Baumhueter, S.; Lai, V.K.; Nunez, L.; Clarke, B.A.; Poueymirou, W.T.; Panaro, F.J.; Na, E.; Dharmarajan, K.; et al. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science 2001, 294, 1704–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Kang, S.Y.; Kim, S.J.; Huynh, D.T.N.; Park, S.K.; Noh, K.; Kang, C.; Suh, J.W.; Park, S. Monotropein Improves Dexamethasone-Induced Muscle Atrophy via the AKT/mTOR/FOXO3a Signaling Pathways. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hah, Y.S.; Lee, W.K.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.H.; Hwang, D.H.; Kang, H.G.; Lee, D.H.; Han, J.H.; Lim, Y.C.; Kim, Y.M. β-Sitosterol Attenuates Dexamethasone-Induced Muscle Atrophy via Regulating FoxO1-Dependent Signaling in C2C12 Cell and Mice Model. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuka, Y.; Egawa, K.; Kanzaki, N.; Izumo, T.; Rogi, T.; Shibata, H. Quercetin glycosides prevent dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2019, 18, 100618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.H.; Park, D.H.; Bae, M.S.; Song, S.H.; Seo, H.J.; Han, D.G.; Oh, D.S.; Jung, S.T.; Cho, Y.C.; Park, K.M.; et al. Analysis of the Active Constituents and Evaluation of the Biological Effects of Quercus acuta Thunb. (Fagaceae) Extracts. Molecules 2018, 23, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, M.H.; Park, K.H.; Kim, M.; Kim, H.H.; Kim, S.R.; Park, K.J.; Heo, J.H.; Lee, M.W. Anti-Oxidative and Anti- Inflammatory Effects of Phenolic Compounds from the Stems of Quercus acuta Thunberg. Asian J. Chem. 2014, 26, 3803–3808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, I.S.; Park, D.H.; Bae, M.S.; Oh, D.S.; Kwon, N.H.; Kim, J.E.; Choi, C.; Cho, S.S. In Vitro and In Vivo Studies on Quercus acuta Thunb. (Fagaceae) Extract: Active Constituents, Serum Uric Acid Suppression, and Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitory Activity. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2017, 2017, 4097195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Yang, H.J.; Go, Y. Quercus acuta Thunb. suppresses LPS-induced neuroinflammation in BV2 microglial cells via regulating MAPK/NF-κB and Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.A.; Bae, D.; Oh, K.N.; Oh, D.R.; Kim, Y.; Kim, Y.; Jeong, I.S.; Choi, E.J.; Lee, S.G.; Kim, M.; et al. Protective effects of Quercus acuta Thunb. fruit extract against UVB-induced photoaging through ERK/AP-1 signaling modulation in human keratinocytes. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2022, 22, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaffe, D.; Saxel, O. Serial passaging and differentiation of myogenic cells isolated from dystrophic mouse muscle. Nature 1977, 270, 725–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, H.M.; Pavlath, G.K.; Hardeman, E.C.; Chiu, C.P.; Silberstein, L.; Webster, S.G.; Miller, S.C.; Webster, C. Plasticity of the differentiated state. Science 1985, 230, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burattini, S.; Ferri, P.; Battistelli, M.; Curci, R.; Luchetti, F.; Falcieri, E. C2C12 murine myoblasts as a model of skeletal muscle development: Morpho-functional characterization. Eur. J. Histochem. 2004, 48, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Charge, S.B.; Rudnicki, M.A. Cellular and molecular regulation of muscle regeneration. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 209–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Choi, S.Y.; Lee, H.I.; Choi, J.H.; Kim, K.W.; Lee, M.K. Yuja peel hot water extract protects against dexamethasone-induced skeletal muscle atrophy through the PI3K-Akt-mTOR/FoxO3α signaling pathway. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2025, 19, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheon, Y.H.; Kim, H.S.; Yeo, J.H.; Shin, D.W.; Kim, N.; Park, S.C.; Lim, S.T.; Kwon, T.K.; Kim, Y.M. Vigeo (Fermented Cordyceps militaris and Lentinula edodes) Alleviates Dexamethasone-Induced Muscle Atrophy through the Akt/mTOR/FoxO3a Signaling Pathway. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1169. [Google Scholar]

- Lecker, S.H.; Jagoe, R.T.; Gilbert, A.; Gomes, M.; Baracos, V.; Bailey, J.; Price, S.R.; Mitch, W.E.; Goldberg, A.L. Multiple types of skeletal muscle atrophy involve a common program of changes in gene expression. FASEB J. 2004, 18, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacheck, J.M.; Hyatt, J.P.; Raffaello, A.; Jagoe, R.T.; Roy, R.R.; Edgerton, V.R.; Lecker, S.H.; Goldberg, A.L. Rapid disuse and denervation atrophy involve transcriptional changes similar to those of muscle wasting during systemic diseases. FASEB J. 2007, 21, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamei, Y.; Miura, S.; Suzuki, M.; Kai, Y.; Mizukami, J.; Taniguchi, T.; Mochida, K.; Hata, T.; Matsuda, J.; Aburatani, H.; et al. Skeletal muscle FOXO1 (FKHR) transgenic mice have less skeletal muscle mass, down- regulated Type I (slow twitch/red muscle) fiber genes, and impaired glycemic control. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 41114–41123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.A.; Sandesara, P.B.; Senf, S.M.; Judge, A.R. Inhibition of FoxO transcriptional activity prevents muscle fiber atrophy during cachexia and induces hypertrophy. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 987–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, T.; Gautel, M. Transcriptional mechanisms regulating skeletal muscle differentiation, growth and homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, M.; Rigby, P.W. Gene regulatory networks and transcriptional mechanisms that control myogenesis. Dev. Cell 2014, 28, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, R.; Yamamoto, S.; Yasumoto, Y.; Kadota, K.; Oishi, K. Dosing schedule-dependent attenuation of dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy in mice. Chronobiol. Int. 2014, 31, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schakman, O.; Kalista, S.; Bertrand, L.; Lause, P.; Verniers, J.; Ketelslegers, J.M.; Thissen, J.P. Role of Akt/GSK-3β/β-catenin transduction pathway in the muscle anti-atrophy action of insulin-like growth factor-I in glucocorticoid-treated rats. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 3900–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPherron, A.C.; Lawler, A.M.; Lee, S.J. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-beta superfamily member. Nature 1997, 387, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiaffino, S.; Mammucari, C. Regulation of skeletal muscle growth by the IGF1-Akt/PKB pathway: Insights from genetic models. Skelet Muscle 2011, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rommel, C.; Bodine, S.C.; Clarke, B.A.; Rossman, R.; Nunez, L.; Stitt, T.N.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; Glass, D.J. Mediation of IGF-1-induced skeletal myotube hypertrophy by PI(3)K/Akt/mTOR and PI(3)K/Akt/GSK3 pathways. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001, 3, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Cosentino, C.; Tamta, A.K.; Khan, D.; Srinivasan, S.; Gavin, M.; Tian, R.; Willette, A.A.; Kapoor, A.; Kumar, A.; et al. Sirtuin 6 inhibition protects against glucocorticoid-induced skeletal muscle atrophy by regulating IGF/PI3K/AKT signaling. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiaffino, S.; Dyar, K.A.; Ciciliot, S.; Blaauw, B.; Sandri, M. Mechanisms regulating skeletal muscle growth and atrophy. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 4294–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egerman, M.A.; Glass, D.J. Signaling pathways controlling skeletal muscle mass. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 49, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, B.D.; Toker, A. AKT/PKB Signaling: Navigating the Network. Cell 2017, 169, 381–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, A.; Bonni, A.; Zigmond, M.J.; Lin, M.Z.; Juo, P.; Hu, L.S.; Anderson, M.J.; Arden, K.C.; Blenis, J.; Greenberg, M.E. Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell 1999, 96, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Brault, J.J.; Schild, A.; Cao, P.; Sandri, M.; Schiaffino, S.; Lecker, S.H.; Goldberg, A.L. FoxO3 coordinately activates protein degradation by the autophagic/lysosomal and proteasomal pathways in atrophying muscle cells. Cell Metab. 2007, 6, 472–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milan, G.; Romanello, V.; Pescatore, F.; Armani, A.; Paik, J.H.; Frasson, L.; Seydel, A.; Zhao, J.; Abraham, R.; Goldberg, A.L.; et al. Regulation of autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system by the FoxO transcriptional network during muscle atrophy. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laplante, M.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 2012, 149, 274–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxton, R.A.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 2017, 168, 960–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J. Regulation of muscle mass by myostatin. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004, 20, 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmers, T.A.; Davies, M.V.; Koniaris, L.G.; Haynes, P.; Esquela, A.F.; Tomkinson, K.N.; McPherron, A.C.; Wolfman, N.M.; Lee, S.J. Induction of cachexia in mice by systemically administered myostatin. Science 2002, 296, 1486–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schakman, O.; Dehoux, M.; Dogné, S.; Kalista, S.; Bertrand, L.; Lause, P.; Verniers, J.; Underwood, L.E.; Ketelslegers, J.M.; Thissen, J.P. Role of IGF-I and the TNFα/NF-κB pathway in the induction of muscle atrogenes by acute inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 303, E729–E739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.M.; Freire de Carvalho, J. Glucocorticoid-induced myopathy. Jt. Bone Spine 2011, 78, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.W.; Oh, S.W.; Chung, D.M.; Park, W.S.; Min, T.S.; Park, C.H.; Kim, H.R. Ishophloroglucin A, Isolated from Ishige okamurae, Alleviates Dexamethasone-Induced Muscle Atrophy through Muscle Protein Metabolism In Vivo. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, C.E.; So, H.K.; Vuong, T.A.; Clarke, E.; Huh, Y.; Kim, J.; Choi, H.; Kim, J.H.; Park, S.K.; Shin, J.; et al. Aronia Upregulates Myogenic Differentiation and Augments Muscle Mass and Function Through Muscle Metabolism. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 753643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).