Featured Application

The findings of this article may be utilized within the automotive industry to systematically validate existing User Interface (UI)/User Experience (UX) concepts based on the derived implications from user-reported challenges, and to inform the development of novel UI/UX concepts guided by the proposed framework and design recommendations.

Abstract

With the ongoing integration of advanced technologies into modern vehicle systems, understanding user interaction becomes a critical factor for safe and intuitive operation—especially in the transition towards autonomous driving. This article uncovers user-reported challenges of UX and in-vehicle UIs. The analysis is based on quantitative and qualitative evaluations of user-generated content (UGC) from automotive-focused online forums. The quantitative analysis is conducted by Natural Language Processing (NLP), while qualitative evaluation is performed through Mayring, applying a deductive–inductive category formation approach. The study investigates challenges related to interface complexity, driver distraction, and missing user diversity in the context of increasing digitalization. Based on the analysis, a set of practical design implications is presented, emphasizing context-sensitive function reduction, multimodal interface concepts, and UX strategies for reducing complexity. It has become evident that UX concepts in the automotive context can only succeed if they are adaptive, safety-oriented, and tailored to the needs of heterogeneous user groups. This leads to the development of an interaction strategy model, serving as a transitional framework for guiding the shift from manual to fully automated driving scenarios. The paper concludes with an outlook on further research to validate and refine the implications and UX framework.

1. Introduction

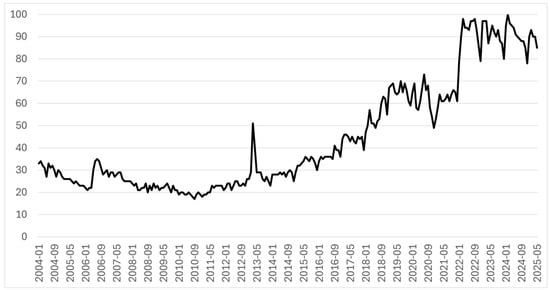

UX refers to the overall perception and response that a person has when interacting with a product or system [1]. The importance of high usability and positive UX has gained increasing recognition across industries, including the automotive sector [2]. A comprehensive UX encompasses all user interactions across the entire customer journey [2]. This also includes all user emotions, beliefs, preferences, perceptions and behaviors that arise before, during, and after interacting with a product or system [1]. The growing relevance of UX in the automotive sector is reflected not only in industry studies—such as KPMG’s Customer Experience Excellence report, where the automotive industry ranks highest in Germany [3]—but also relevant for the general public, as illustrated by rising search trends for UX worldwide [4]. Figure 1 shows the relative search volume over time, with 100 representing the peak interest in the observed period [4].

Figure 1.

Search trends for UX [4].

Despite this growing attention, the design of in-vehicle UX and UI faces challenges—especially in the context of advancing digitalization. A recent survey of 1428 drivers indicated that 89 percent preferred physical controls to touchscreen-based interactions. Drivers also express frustration with digitalized vehicle functions that require long navigating through touchscreen menus [5]. These challenges underline an initial usability tension between technological advancement and user-centered design—a conflict that this paper aims to prove and further expands through empirical analysis.

The study’s primary objective is to identify additional challenges and to convert these insights into actionable implications. Based on an analysis of UGC from automotive-focused online forums, this study develops a conceptual framework to guide user-centered interaction strategies. The proposed framework is intended to provide a strategic basis for creating intuitive in-vehicle experiences. The central research questions addressed are: What key challenges in automotive UX emerge from user feedback in online forums? What implications can be derived to support the transition from active driver to passive passenger in the context of increasing driving automation?

Given the diversity of user expectations and the growing heterogeneity of user groups—from traditional drivers to digitally experienced generations—a deep understanding of real-world user needs is becoming essential for manufacturers. Online forums provide a valuable source of unfiltered user perspectives, allowing researchers to identify pain points. This motivates the systematic analysis of user-generated content to identify recurring usability barriers and derive implications for future interaction strategies.

The study reveals recurring challenges related to interface complexity, driver distraction, and a lack of user diversity. Based on the findings, a set of practical implications and a conceptual framework are proposed to guide the transition from manual to automated driving.

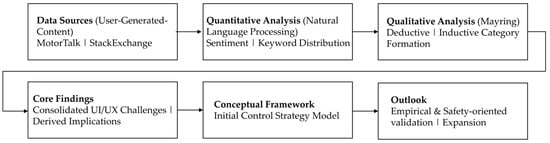

To enhance the analytical procedure, a summary diagram can be found in Figure 2. It provides an overview of the research workflow, illustrating the data sources, the applied mixed-methods approach, and the derivation of the resulting implications and conceptual framework.

Figure 2.

Overview of the research process.

2. Literature Review

The integration of digital technologies into the automotive sector has reshaped user expectations. To establish a comprehensive foundation for the present study, this section reviews three key domains: UGC in research, digital transformation in the automotive context and NLP for analyzing large-scale textual data. This review highlights existing challenges of in-vehicle interaction and outlines the methodological foundations for the subsequent analysis.

2.1. User-Generated-Content (UGC) in Research

UGC refers to information created and shared by users available on a system, reflecting their individual experiences and opinions on a given topic, irrespective of their level of expertise. Owing to the large numbers of contributors, UGC provides substantial volumes of experience-based information and data across diverse domains [6]. Prior research highlights UGC as a promising data source for various applications, including analytical research, when the data is publicly available [7]. Therefore, UGC captures experience-driven perspectives from heterogenous user groups, providing authentic insights into reals world issues, including usability challenges and interaction needs. Given these advantages, UGC is employed in the present study to efficiently obtain extensive user feedback that can be systematically processed and analyzed.

2.2. Digital Transformation in the Automotive Sector

KPMG identifies artificial intelligence (AI) as an opportunity for enhancing future customer experiences [3]. According to Bitkom, the growing adoption of AI across the German economy highlights its strategic relevance and confirms AI as a key future-oriented technology [8]. The European AI Continent Action Plan further highlights the importance of AI [9].

Studies conducted by the digital association Bitkom reveal a remarkable shift in the automotive context: while digital technologies and services are gaining importance, traditional factors such as brand and design are losing relevance [10]. Bitkom Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Dr. Bernhard Rohleder emphasizes that customers increasingly expect smart vehicles, and that future cars must by default be conceived as digital devices [10]. This technological transformation toward digitalized vehicles is accompanied by changing user expectations and emerging priorities. According to Christina Schehl, Executive Vice President at Capgemini Invent, a shift can be observed among Generation Z, Millennials, and Generation X—from private vehicle ownership towards an on-demand usage [11]. In an increasingly dynamic and competitive market, delivering an optimal customer and mobility experience across the entire customer journey may serve as a key differentiator for automotive manufacturers and unlock new revenue opportunities [11].

Personalization is essential for a positive UX, as it enables closer alignment with the individual needs of different drivers [12]. In the context of shared mobility, complexity increases as customers expect personal preferences to be rapidly applied in highly connected vehicles—similar to the seamless experience of using a smartphone [12]. Consequently, time to market has become a critical metric in UX design [12].

The influence of UX on economic performance indicators—such as purchase decisions, brand loyalty, or revenue in the automotive sector—necessitates a critical review of existing metrics, which often rely on established but outdated evaluation approaches [2]. Considering ongoing digitalization, increasing vehicle connectivity, and emerging mobility concepts, traditional evaluation models require expansion. This need is underscored by the 2024 Gartner Digital Automaker Index, which evaluates the digital maturity of automotive manufacturers and their competence in key future-oriented domains, particularly software development. According to the index, Tesla leads with a score of 76.9%, followed by Nio with 71.2% and Xpeng with 66.8%. These manufacturers prioritize software-centric development, while traditional hardware engineering plays a less important role. Established players such as Volkswagen and Toyota, by contrast, show a significant decline in the index [13]. Against this backdrop, it becomes essential to investigate new approaches for systematically and sustainably capturing the value of user-centered design [2].

According to the Capgemini Research Institute, automotive executives and users assess the relevance of brand reputation, usability, and emotional connection in purchasing decisions quite differently [11]. Furthermore, the Bain Customer-led Growth Diagnostic Questionnaire (Bain & Company) highlights a striking discrepancy between corporate self-perception and actual customer experience: while 80% of surveyed companies believe delivering an exceptional customer experience, only 8% of their customers agree. This gap—commonly referred as delivery gap—underscores the need for data-driven, customer-centered validation [2].

To fulfill the data-based, user-centered validation approach advocated by Fischer [2], customer feedback and user experiences are subjected to comprehensive analysis. The large volume of subjective data enables a differentiated assessment of in-vehicle UX across a wide range of brands and models. A systematic evaluation supports the identification of recurring patterns that reflect central challenges and opportunities for improvement. In order to handle the extensive data generated in online communities, a systematic approach for analyzing textual data is applied using Natural Language Processing (NLP) [14].

2.3. Methodological Foundations of Natural Language Processing (NLP)

NLP comprises the subfields Natural Language Understanding (NLU) and Natural Language Generation (NLG) [15]. While NLU focuses on the comprehension of natural language, NLG is concerned with its generation [14]. NLP is a subdiscipline of artificial intelligence (AI) and enables computer systems to interpret and generate both, text and speech [16]. This is achieved through the integration of computational linguistics, which models human language using rule-based systems, with statistical methods, machine learning (ML), and deep learning approaches [17]. Deep learning, a subset of ML, relies on algorithms based on artificial neural networks. Prominent applications of deep learning are large language models (LLMs), which are capable of autonomously generating new content [18]. According to Dr. Sonja Grigoleit, simplifying interpersonal communication and enabling machine-based text analysis are central goals of NLP [19]. NLP offers advantages across a wide range of applications, particularly data analysis and insight generation [17]. In this context, unstructured text data—such as customer reviews or social media posts—can be extracted [17] and transformed into a structured data format [14].

Application scenarios of NLU include sentiment analysis, which extracts subjective features such as moods and emotions from text, and text summarization of large datasets, which enables analysts to efficiently identify relevant information and support data-driven decisions-making [17]. In addition, another well-known application scenario is topic modeling, which is used to identify the underlying topics within a dataset [17].

Classical NLP can be divided into four main processing steps: text preprocessing, feature extraction, text analysis, and model training [17], with text analysis representing the application of traditional NLP language models. In contrast, deep learning algorithms and LLM omit the manual feature extraction step, as this process is implicitly learned within the model [20,21].

Instead of model training, pretrained NLP language models are employed during the text analysis stage, as this study focuses on the content-based evaluation of textual data.

The aim of text preprocessing is to transform raw text into a format suitable for machine analysis. A key step for both NLP methods and LLMs is tokenization, the process of segmenting text into individual words or sentences [17,21]. In classical NLP methods, tokenization is followed by normalization, which involves removing case distinctions [22]. The objective of this step is to achieve standardization while reducing computational demand [22]. Further preprocessing includes the removal of stop words—frequently occurring but semantically uninformative filler words such as the or is—as well punctuation marks. Stemming and lemmatization reduce words to their base form, thereby decreasing complexity and increasing the efficiency of analysis, albeit with potential losses in precision [22].

Feature extraction refers to the process of converting raw text into numerical representations suitable for ML algorithms. Classical approaches, such as Bag-of-Words (BoW) and Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF), capture the frequency of terms, with TF-IDF additionally weighting terms according to their significance [17]. Words are accessed via index numbers, enabling the entire corpus to be represented as a document-term matrix, which serves as the basis for further analyses [23]. Advanced word embeddings, such as Word2Vec or GloVe, convert words into dense vector representations [17], where semantically similar terms are mapped to proximate positions within the vector space [22]. These methods facilitate the representation of semantic relationships between words [17]. Contextual embeddings extend this principle by capturing not only the meaning of words but also their usage in specific contexts [17]—a prerequisite for precise semantic interpretation, as word meanings can vary depending on context [23]. A prominent approach is Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT), which is based on transfer learning and leverages previously acquired knowledge [23].

Text analysis involves the interpretation and extraction of relevant information from textual data using predefined NLP models. This includes, among other techniques, part-of-speech (POS) tagging to identify the grammatical structure of words, as well as sentiment analysis, which is applied in the context of this study [17].

3. Materials and Methods

The present methodology follows a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative and qualitative analysis techniques to achieve a comprehensive understanding of challenges in the field of UX and UI [24]. This dual-method combination enables a detailed examination by considering both objective, measurable data and subjective, content-related insights. In advance, desk research was conducted to systematically identify potential data sources and asses their suitability. As the data basis, the German-language forum MotorTalk [25] and the international platform StackExchange [26] focusing on UX-related car topics, were selected. The choice was guided by their high thematic relevance, active and diverse user communities, and public availability of their content. The two forums provide a solid foundation for the first analysis phase of this study. The forum quotations are processed in anonymized form, with orthographic errors corrected for readability without altering the original meaning. All German quotations were translated into English by the author to ensure consistency and accessibility. Moreover, all analytical procedures—including preprocessing, TF-IDF computation, and sentiment classification—were documented within a Jupyter Notebook version 7.3.3 [27] to guarantee transparency, traceability, and reproducibility of the results.

The quantitative analysis is based on the evaluation of UGC using specific NLP techniques. To ensure methodological transparency, the preprocessing pipeline follows these principles:

(1) extraction and structuring of raw text: The forum data was initially extracted in Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) format and subsequently converted into JavaScript Object Notation (JSON). During this step, all non-textual elements such as images, scripts, or hyperlinks were removed to ensure a clean and analyzable text corpus. Additionally, metadata such as timestamps and user identifiers were stripped to comply with ethical and privacy considerations.

(2) Text segmentation: Using a Jupyter Notebook [27], the dataset was segmented into sentences and compiled into an ordered list in form of a text file. The extracted MotorTalk dataset comprises 26,789 sentences, whereas the StackExchange dataset contains 2413 sentences. Both datasets consist of contributions from diverse users, thereby reflecting a high content-related heterogeneity.

(3) Filtering via keyword-based selection: The MotorTalk dataset is further filtered using self-defined UX and UI keywords to exclude off-topic sentences from subsequent analysis.

(4) Application of NLP models: The core instrument of the quantitative investigation is sentiment analysis, conducted with the pre-trained and publicly available models german-sentiment-bert for German-language content [28] and cardiffnlp/twitter-roberta-base-sentiment for English-language content [29]. The german-sentiment-bert model is based on Googles Bert architecture and was trained on a corpus of 1834 million German-language samples, covering specific domains such as social media posts and user reviews [28]. German-sentiment-bert demonstrates high classification accuracy of up to 99.67% on specific benchmark domains and is well suited for efficiently processing large-scale datasets. Compared to other approaches, Bert-based architectures achieves slightly better classification accuracy [30]. The model twitter-roberta-base-sentiment is specifically designed to capture the linguistic nuances of social media communication and represents a strong approach analyzing public opinion expressed in online platforms [31]. Although domain adaption was considered, general models are ultimately selected for the analysis. Domain-adapted models were not implemented for two methodological reasons. First, effective domain adaptation requires a large and domain-specific training dataset. Such data is not available for the automotive UX context, and creating an annotated corpus would exceed the scope of this study. Second, existing domain-adapted sentiment models that could be reused are typically optimized for narrowly defined domains—such as specific technical documentations—and therefore do not align well with the conversational and heterogenous language found in user forum discussions. The examined forums do not rely on specialized technical terminology but instead reflect users’ general impressions and everyday experiences. Consequently, broad and well-established sentiment detection models were deemed more suitable for capturing the overall sentiment. Both sentiment models are applied sentence-wise. Each model outputs a distribution across the sentiment categories. Sentiment classification is performed into the categories positive, neutral, and negative. In addition, keyword distribution based on TF-IDF is applied to identify thematic structures and frequently occurring words to facilitate the thematic orientation within the datasets [17]. TF-IDF serves as a numerical weighting that highlights word characteristics for specific topics, thereby supporting early-stage topic exploration and complementing the sentiment-based categorization [17]. To increase precision, stop words are defined to remove semantically irrelevant and frequently recurring filler words. These analyses provide the basis for an initial thematic classification based on sentiment polarity and characteristic keywords, which is further refined in the qualitative analysis.

The qualitative investigation follows a structuring content analysis procedure according to Mayring, applying a deductive–inductive category formation approach with a particular emphasis on the inductive approach. The deductive approach follows a strongly simplified adaption [32]. The deductive categories are based on the two challenges identified in the literature and outlined in the survey results presented in the introduction: the preference for physical controls over touch-based operation (goal conflict: touch versus physical control) and frustration with complex menu structures (complexity and overload) [5]. The development of deductive subcategories and detailed coding guidelines was deliberately omitted, as the paper aims to analyze the UGC data [32]. The two deductive categories are sufficient for this purpose, serving as a basis to be verified through the detailed inductive approach. The scope of the inductive approach includes the whole UX/UI-filtered forum datasets, which were examined line by line. Text segments without substantive relevance are excluded from further consideration. Relevant sentences that cannot be assigned to either of the two deductive categories are allocated to newly defined inductive categories. The category system is reviewed throughout the analysis to ensure a consistent level of abstraction and is refined through iterative adjustments. This inductive approach forms the methodological core of the present study [32]. To strengthen analytical rigor, the inductive categorization emphasizes subjective interpretations of mentioned user needs, implicit criticism and suggestions for improvement. This enables the derivation of fine-gained insights that may not be captured through automated NLP methods. Mayring’s Intra-/Intercoder check was not applied but is planned for a later stage, because the aim of the current study was explorative and centered on identifying substantive challenges rather than establishing a final, stabilized category system [32]. At this early analytical stage, the inductive categories were still evolving and served primarily as heuristic constructs to structure a complex and heterogenous dataset. Future work will verify the identified categories and challenges through interviews thereby reducing subjectivity and strengthening the validity of the findings.

Generative AI (GenAI) was employed for text editing—using OpenAI’s ChatGPT 5.1 [33]—for grammar correction, spelling adjustments, punctuation refinement, and translation—without influencing the analytical outcome of the study. GenAI was additionally employed to optimize the self-developed framework for control strategy, which is presented in Section 5. Despite linguistic revision, the possibility of translation-related bias arising from the German source text cannot be fully excluded.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

4. Results

This chapter presents the results of the study, focusing on user-reported challenges in the context of in-vehicle UX and UI. For clarity and systematic presentation, the results are structured into two parts: a quantitative analysis for insights from sentiment analysis and topic distribution, and a qualitative analysis that highlights specific recurring challenges based on user statements.

4.1. Quantitative Results

The quantitative findings of the sentiment analysis, presented in Table 1 and Table 2, provide an initial overview. The column Sentiment displays the categories positive, neutral, and negative, while the column Frequency indicates the absolute number of sentences and the column Percentage illustrates their relative distribution.

Table 1.

Results of the Sentiment Analysis of StackExchange on UX.

Table 2.

Results of the Sentiment Analysis of MotorTalk with filtering of UX.

Across all analyzed datasets, a predominantly neutral to negative overall sentiment is observed, confirming the so-called selection bias, as users trend to articulate negative rather than positive experiences [34]. The concentration on negative user experiences facilitates the targeted identification of relevant challenges while simultaneously highlighting the necessity for the systematic development of improvement strategies. Furthermore, it must be acknowledged that the results may be influenced by cultural differences.

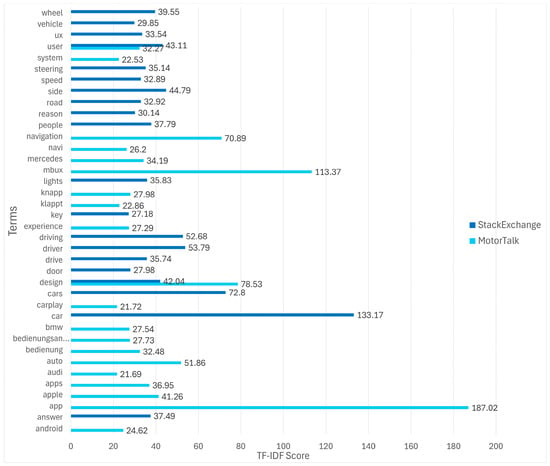

A keyword distribution of salient terms based on TF-IDF weighting is conducted as part of the quantitative analysis. After removing common and often used stop words, the top 20 terms of the MotorTalk and StackExchange datasets are presented in Figure 3. The MotorTalk dataset is characterized by brand-specific terms such as BMW, MBUX, Mercedes, Audi, Apple, Carplay, and Android, suggesting that the discussion is thematically focused on specific UI systems and the usability of their associated digital features. By contrast, the StackExchange dataset exhibits a stronger functional orientation, with salient terms such as car, driving, driver, steering, wheel, user, design, and UX. This indicates that the discussion is less brand-centered and instead oriented toward general automotive UX systems.

Figure 3.

Comparison of keyword distribution: MotorTalk and StackExchange.

4.2. Qualitative Results

The qualitative analysis reveals a set of recurring challenges that strongly affect the UX and the usability of contemporary in-vehicle interfaces. The consolidated challenges, illustrated with representative quotes, emphasize key points of tension that substantially shape the overall driving experience.

4.2.1. Consolidated Challenges StackExchange

Complexity and Cognitive Overload. A central challenge arises from feature overload, particularly the integration of numerous functions within the limited space of central touchscreens. This results in cognitive overload, leading to uncertainty and distraction of drivers. Consequently, intuitive accessibility and functional clarity are significantly impaired, especially in dynamic driving contexts.

- “Putting so many fingers in so small of a space seems like a pain in the neck, and more importantly, the UI is in no way whatsoever self-explanatory” [26].

- “The problem is car manufacturers cram too many features in too little of a space and you can’t possibly control them without endangering yourself by taking your eyes of the road for a certain amount of time” [26].

- “[…] Don’t let your design be the cause of an accident” [26].

Voice Control as an Incomplete Solution. Voice control is currently not perceived as a fully adequate alternative to manual operation. In the automotive context, shortcomings in speech recognition and system feedback are particularly evident. These limitations may cause misunderstandings and disrupt the interaction flow. Users further note that voice control is especially unreliable when handling complex or multi-step commands.

- “Give me voice controls for lesser used tasks or tasks which require more configuration” [26].

- “Better voice recognition” [26].

Visual Distraction Caused by Touch Operation. The shift from haptic controls to visually oriented, touch-based interfaces introduces substantial challenges. The qualitative analysis indicates that touch interaction requires increased visual attention, forcing drivers to temporarily divert their focus from the driving task. This mode of operation generates uncertainty, reduces usability while driving, and is perceived by users as a safety-relevant concern.

- “It’s very risky to check changes on the tablet’s screen because you have to move your eyes of the road” [26].

- “Car users are not tablet users” [26].

- “Touchscreens are great for computing devices or a thermostat or even for passengers in a vehicle, but not for a driver’s in-car interface. In a car, the driver’s eyes need to be on the road” [26].

- “[…] I would still prefer tactile feedback so I could ‘look’ for buttons with my fingertips” [26].

Changing User Roles. Another key finding concerns the transformation of user roles. Traditional driver profiles, centered on individual ownership, are increasingly replaced by situational, shared, or fluctuating usage patterns, as seen in the context of car-sharing. This shift challenges conventional UX designs, which are primarily oriented toward personalized settings and stable user-vehicle relationships. As a result, individually tailored interfaces may become less practical, creating the need for context-adaptive and flexibly configurable UX solutions.

- “People won’t own a car but be members in a [shared mobility] program” [26].

- “With a self-driving car everybody in it will behave like a passenger” [26].

- “The cars of today stand still most of their lives. That’s not efficient” [26].

Neglect of Target Group Needs. Current UX developments tend to focus technology-experienced user groups, often neglecting older or less technologically experienced users. This limitation is particularly evident in the restricted accessibility of modern UIs. A one-size-fits-all approach proves insufficient in the automotive context, highlighting the need for interfaces that are more differentiated and adaptively tailored to diverse user requirements.

- “People only opt-in to those, so whilst some (you or I) might find them easier to use and a better user experience others (our Grandparents) might find them more complex” [26].

- “They’re older (average), have a higher chance of being “technophobes” and are also more keen on getting the job done easily compared to a tablet which is often a leisure device” [26].

- “I have driven a number of cars with the touch screen feature and they are a distraction. What really gripes me is that most manufacturers are making them standard equipment and not giving the buyer a choice” [26].

Trade-Off: Flexible Digital UI versus the Desire for Physical Controls. A recurring area of tension is the trade-off between the flexibility of digital interfaces and users’ preference for tactile feedback through physical controls. While digital UIs enable context-dependent adaptability, physical controls provide a stronger sense of safety, orientation, and intuitive operability—especially in dynamic driving conditions. The qualitative findings suggest that hybrid UI concepts, which combine touchscreens with physical controls, are widely perceived as a promising compromise.

- “Touchscreens offer almost infinite possibilities for variable user interfaces, but tactile buttons offer accuracy, speed, motor memory and safer operation in a moving vehicle” [26].

- “You can buy a car and it would be space to configure or set to your liking” [26].

- “There seems to be a an almost stalemate between the desire to offer a flexible UI and the need for physical buttons in a moving vehicle” [26].

4.2.2. Consolidated Challenges MotorTalk

Complexity and Overload. A recurring theme of criticism concerns the overcomplexity of modern vehicle interfaces. Users frequently report confusing menu structures, inconsistent terminology, and an oversupply of functions, many of which are perceived as irrelevant. This concentration of features complicates intuitive orientation and constitutes a major barrier to a positive UX. The resulting frustration affects not only user satisfaction but also brand perception. In addition, economic inefficiencies may arise, as the perceived utility of many functions is disproportionate to the effort required for their development.

- “Limited logic, partly confusing menus, cumbersome operation” [25] [translated from German].

- “The entire menu did not make sense to me” [25] [translated from German].

- “Intuitive looks different” [25] [translated from German].

Voice Control as an Incomplete Solution. Voice control is perceived in the driving context as an unreliable alternative to manual operation. Users highlight shortcomings in both speech recognition and system feedback, which disrupt the flow of interaction and negatively affect the overall UX.

- “Sometimes you get stuck in a loop and can’t get out. There is really an urgent need for improvement” [25] [translated from German].

- “The speech recognition is OK, but the special destinations just would not work for me at all […]” [25] [translated from German].

Smartphone Mentality versus Vehicle Reality. Transferring interaction logics from the smartphone domain to the vehicle context elicits critical user reactions. While users expect interfaces to be as intuitive, fast, and customizable as on mobile devices, the driving context imposes fundamentally different requirements. The dynamic and often stress-laden conditions of driving make a direct adoption of mobile interaction paradigms problematic. A one-to-one transfer neglects these situational requirements and may pose considerable risks to both safety and usability.

- “Input lag and screen updates are ok, but only ok—not on the iOS level” [25] [translated from German].

- “The user experience will remain limited because CarPlay is conceptually designed for use with touchscreens” [25] [translated from German].

- “I also don’t see any added value from touch input […]. Instead, I always have to visually check whether the input has been registered—and in a product like a car, that should not be the focus” [25] [translated from German].

Neglect of Diverse User Needs. The analysis reveals a divergence in UX requirements across different user groups. While younger, tech-savvy users demand smart, emotional, and adaptive interaction concepts, older or less technologically experienced drivers are increasingly overwhelmed. Whereas vehicles in the past could largely be operated independently of user group, today the lack of differentiation in UX strategies not only excludes potential user segments but also poses risks to customer retention and market diversification.

- “[…] I can imagine that an 80-year-old grandfather […] would have some problems with this operating concept “ [25] [translated from German].

- “It’s about time that car manufacturers […] recognize that software is playing an increasingly important role—especially for the touch generation” [25] [translated from German].

Visual Distraction from Touch Operation. Touch-based interaction is particularly perceived as distracting and unsafe in dynamic driving contexts. Users report the need for continuous visual control and the absence of tactile feedback, which prolong interaction time and increase cognitive load. These factors not only impair the overall usability but may also contribute to safety-relevant risks in road traffic.

- “Using buttons is distracting—yes, but only for the blink of an eye [.] Using touchscreens is distracting—yes, […] also when navigating submenus, and for longer than just the blink of an eye” [25] [translated from German].

- “I’m always glad when I can use my iDrive again […]” [25] [translated from German].

- “If the touchscreen is right in the middle, not angled, and menu items are scattered all over, then there is no orientation “ [25] [translated from German].

Trend-Driven Decisions Instead of Validated User Needs. The introduction of new technical features often takes place without a clearly discernible added value from the user’s perspective. Many of these so-called gadgets are perceived as marketing-driven show effects, whose practical utility remains questionable and appears to serve primarily for entertainment purposes. The resulting disappointment can undermine trust in both brand and product while reinforcing skepticism toward future UX innovations.

- “Of course, there should be such gimmick cars for the respective target group. But this should not become a general trend” [25] [translated from German].

- “Manufacturers simply HAVE TO keep up with time, otherwise they will be overtaken by the competition” [25] [translated from German].

- “[…] As soon as a car in a test by one of the big auto magazines or TV formats is not able to use every possible IT and smartphone feature or eventuality, it immediately receives wore test results” [25] [translated from German].

Cost Optimization over UX Quality. The prioritization of cost and time efficiency (time to market) frequently leads to the replacement of physical controls with touchscreens [5]. While this approach enables resource savings and a more streamlined design, it simultaneously creates a trade-off between aesthetic ambition and functional usability in everyday contexts—with potentially negative consequences for the long-term UX.

- “Ideally, there should be a sensible combination of touchscreen and buttons […]” [25] [translated from German].

- “Electronic displays and controls are cheaper than electromechanical ones. To make the customer accept them, funny gimmicks are added that create a buying incentive” [25] [translated from German].

5. Discussion

The qualitative analysis of both forums reveals clear thematic overlaps. Users particularly criticize the overcomplexity of modern interfaces, the lack of haptic feedback in touch-based interaction, and the insufficient consideration of diverse user needs. Both sources confirm that current in-vehicle UI designs are frequently perceived as overwhelming and distracting. These designs are also described as poorly suited to everyday use. While StackExchange places greater emphasis on changing user roles and hybrid interaction solutions, MotorTalk additionally highlights economic aspects such as cost optimization and marketing-driven feature decisions. Summarized, these findings underscore the necessity of a more user-centered, adaptive, and safety-oriented UX design in the automotive context.

Recent empirical findings corroborate these results. In particular, 1428 drivers—89 percent of respondents—prefer physical interaction modalities over touchscreen-based operation, thereby identifying touch interfaces as a critical concern in current vehicle control [5]. The same empirical findings further report complexity and cognitive overload, with particular criticism directed at deeply nested touchscreen menu structures [5]. In contrast, Bitkom CEO Dr. Bernhard Rohleder emphasizes that customers increasingly expect smart vehicles and argues that future cars must be conceived as digital devices [10]. This expectation is challenged by Matthew Avery, Director of Strategic Development at EuroNCAP. He explicitly frames the presence of physical, intuitive controls as an important requirement for vehicles to achieve the highest possible safety ratings in future assessments [5].

Contrasting user perspectives across MotorTalk and StackExchange further highlight the heterogeneity and underlying tension in user expectations regarding in-vehicle UX. Some users prefer touch-based interaction, while others express relief when interacting with traditional control elements: “A touchscreen is far more intuitive than anything involving those annoying rotary knobs and controllers” [25] [translated from German] and “I’m always glad when I can use my iDrive again” [25] [translated from German].

A similar divergence emerges with physical buttons. Certain users appreciate additional controls whereas others perceive them as unnecessary: “[…] Additional buttons are nice enhancement” [25] [translated from German] and “[…] additional buttons are unnecessary and represent a small (also visual) step backwards” [25] [translated from German].

Moreover, certain users emphasize the increasing relevance of software and digitalization in modern automotive UX and others reject the shift: “It is time for car manufacturers in Germany to recognize that the importance of software is becoming increasingly significant […]” [25] [translated from German] and “[…] Just because it is trend—everything is being operated with gestures, touch, or voice” [25] [translated from German].

These contrasting point of views highlight the necessity for adaptive interaction strategies rather than a one-size-fits-all solution.

5.1. Practical Implications

Based on the qualitative analysis of user contribution, central strategic and design implications can be derived for the development of in-vehicle UX and UI. These implications address not only technological aspects but also integrate safety-relevant and social requirements associated with modern mobility concepts. Some of the implications emerge directly form the qualitative analysis, which revealed not only recurring challenges but also explicit user needs and solution ideas.

Target Group-Oriented Differentiation. An important implication of the findings is the need for UX concepts to more explicitly address the heterogeneity of user groups. This is particularly relevant given the considerable variation in age, technical experience, and cognitive abilities. An illustrative example can be found in the distinction between conventional smartphones and so-called senior smartphones. These employ larger buttons, simplified menus, and clearer navigation tailored specifically to the needs of older, less tech-savvy users [35]. Transferred to the automotive context, the introduction of differentiated operating profiles—such as a reduced standard mode and an extended expert mode—can represent a viable solution. In addition, adaptive interface depths that dynamically adjust to user competence or situational context may enhance usability while simultaneously broadening market reach. Recent advances in AI and LLMs further reinforce this potential: natural-language optimization of voice assistance systems can reduce reliance on menu-based touch control and thereby improve accessibility. A current example is the integration of ChatGPT into the voice control system of Mercedes-Benz vehicles [5].

Context-Sensitive Function Reduction. Context-based reduction strategies are essential to minimize visual and functional complexity in critical driving scenarios. One promising approach is the principle of feature fading—the situational reduction in visible functions while driving. Functions are not permanently removed but temporarily hidden. This reduces operating errors, fostering concentration on the driving task, and improves overall usability. At the same time, the full range of functions remains accessible within the passenger entertainment environment, ensuring that comfort and entertainment are not restricted. A complementary strategy involves a temporally staged information logic, following the principle of “Now/In-a-while/Whenever”. This concept considers not only the spatial arrangement of information but also its temporal relevance. Essential information, such as speed, is displayed immediately in the “Now” status, ideally positioned directly within the drivers field of view. Information that soon become relevant, such as navigation prompts or fuel level, appears in the “In-a-while” status, placed contextually but less prominently within the instrument cluster. Non-urgent functions, such as media settings, are deferred to the “Whenever” status and made accessible via secondary interfaces such as the center stack [25]. By prioritizing information according to temporal urgency, this approach can effectively reduce information overload and support more efficient management of the driver’s cognitive workload. This implication requires further detailed validation through interviews with both drivers and domain experts to assess these potential effects and to determine whether context-sensitive function reduction may also elicit anxiety or distrust.

Multimodal Interaction Concepts. The findings imply that an exclusive reliance on touch interfaces is problematic in dynamic driving contexts. Safety-critical core functions should remain accessible through physical controls with tactile feedback. This requirement is also emphasized by Jake Nelson, Director of Traffic Safety Research at AAA [5]. One promising solution that combines haptic operability with individual customization is the implementation of physically reconfigurable buttons. These buttons enable reliable tactile interaction while allowing for personalized functionality. In parallel, touch and voice control can be reserved for secondary functions, complemented by the “Now/In-a-while/Whenever” approach to manage temporal relevance. In the current transitional phase between manual and highly automated driving, the deliberate reintroduction or retention of haptic interaction elements for core functions must be considered essential. Reflecting this development, Volkswagen’s Head of Design, Andreas Mindt, has already confirmed the reimplementation of physical controls for volume, seat heating, climate control, and hazard lights in all upcoming models [5]. While in long term—once fully autonomous driving systems are widespread—a stronger focus on touch-based and visually oriented interfaces may be justified, current vehicle interaction remains in a hybrid stage. Driver attention is still required and the driving task cannot yet be permanently delegated. Interfaces must therefore remain clear, intuitive, and operable even under stressful conditions. Only with the full deployment of autonomous driving systems it will become feasible to progressively shift interface design towards visually reduced and entertainment-oriented models. Until then, a balanced, multimodal UX concept is necessary to reconcile present safety requirements with future usage scenarios. Matthew Avery, Director of Strategic Development at EuroNCAP, further emphasizes this by demanding the integration of physical, intuitive controls as a safety requirement for achieving the highest possible ratings in future vehicle assessments [5].

Functional Discipline in Feature Integration. The introduction of new functions must be guided by validated usage scenario rather than technological feasibility or marketing incentives. Features that do not provide recognizable user value not only increase system complexity but may also erode trust in both the brand and the product. By contrast, UX concepts characterized by clarity, purposefulness, and transparent functionality can fosters long-term user loyalty and establishes sustainable competitive differentiation.

Simplicity First Along the Customer Journey. The results highlight that UX design should not begin within the vehicle itself. Instead, it must extend to the entire customer journey, starting with the very first digital touchpoint, such as the online configurator. To enhance both usability and purchase intention, the principle of Simplicity First should be applied consistently across all interaction phases. Reducing complexity through clear structures, intuitive navigation, and streamlined choice architectures—combined with differentiation across user groups—can reduce cognitive load. It can also reduce purchase barriers and increase conversion rates.

Overall, the implications highlight that a future-oriented vehicle UX can only be effective and widely accepted if it is conceived holistically and implemented consistently in a user-centered manner. This requires the development of an integrative UX framework that aligns technological innovation with safety-critical and contextual requirements. At the same time, it must accommodate user-specific preferences. In the context of an anticipated shift from ownership-based to shared mobility, as well as the increasing prevalence of autonomous driving scenarios, the ability to adapt to situational context will become a key competence of future in-vehicle interfaces. A structured transition strategy for the progression from manual to autonomous driving is therefore indispensable. During this transitional phase, manufacturers bear a particular responsibility to ensure safe, intuitive, and contextually adapted user guidance. This is necessary to prevent operation errors and minimize driver distraction. In this regard, Volkswagen’s Head of Design, Andreas Mindt, has explicitly characterized the full digitalization strategy of previous Volkswagen generations—particularly the operating concept of the Golf Mk8—as a manufacturer’s mistake. He emphasizes: “we will never, ever make this mistake anymore … It’s not a phone, it’s a car” [5]. Furthermore, UX systems must increasingly be capable of recognizing different user roles and contexts—from the active driver to the situationally passive passenger—and prioritizing information accordingly. Only through such adaptability can a sustainable and future-proof UX in everyday mobility be ensured. Manufacturers that proactively embrace these requirements will be able to secure significant competitive advantages.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

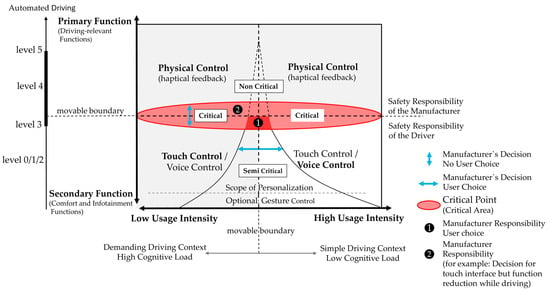

Based on the qualitative findings and practical implications, a theoretical framework is developed to conceptualize the dynamic interplay between safety, context, and personalization. Figure 4 illustrates the central contribution which this article draws from the extensive analysis: a developed model for categorizing interaction types in the automotive context along two dimensions—usage intensity (x-axis) and functional relevance (y-axis)—further differentiated into primary and secondary functions. On the y-axis, the SAE levels of driving automation are shown, ranging from Level 0 (no driving automation) to Level 5 (full driving automation) [36]. The framework integrates physical, voice, touch, and gesture-based control modalities.

Figure 4.

Conceptual framework for control strategy towards autonomous driving.

In the lower section of the framework, which is assigned to secondary functions, a semi-critical zone is illustrated by a horizontal blue double arrow. As functional criticality decreases, this zone expands and creates space for user-specific interaction choices. This space is defined here as the scope of personalization. Within this area, users may select their preferred interaction modes, such as touch or voice control, depending on individual preferences, technical affinity, or age group. UX systems should therefore provide appropriate personalization options while ensuring a clear separation from critical primary functions. The scope of personalization is deliberately modeled as asymmetrically extended toward higher usage intensity. This reflects the increasing importance of user-centered adaptions for frequently used but less safety-critical secondary functions. Such differentiation not only enhances the overall UX but may also contributes to reducing individual cognitive load.

At the core of the model is the area surrounding the critical point, illustrated by a red-highlighted ellipse. This point represents the intersection of high usage frequency and safety-critical functionality. Within this zone, the requirements for human–machine interface (HMI) are particularly high: the design must be robust, intuitive, and unambiguous. User personalization is not recommended, as an inappropriate choice of interaction mode for essential driving functions—such as relying exclusively on touch input—can create significant risks of distraction or even endangerment. In this domain, responsibility lies primarily with the manufacturer and system design.

The elliptical shape of the critical point illustrates that it does not represent a sharply defined spot. Instead, it marks a gradual transition zone (critical area) within which risks dynamically shift depending on the usage context. This highlights the need for adaptive design approaches and assigns clear responsibility on the manufacturer, particularly regarding safety-critical functions.

With increasing levels of automation, the preferred mode of interaction shifts vertically along the Y-axis toward multimodal and more invasive interaction concepts such as touch control. This shift, however, depends on the specific usage context and the driver’s cognitive load. The movable boundaries depicted in the model reflect this dynamic: while flexible interaction via touch may be appropriate in low-stress, simple driving situations, it becomes considerably less suitable in more demanding scenarios. At present, gesture control should be regarded as an supplementary option for simple secondary functions.

Within the highlighted section of the automated driving axis, corresponding to automation levels 3 to 5, a gradual shift in responsibility and role occurs—from the active driver to the passive passenger [36]. The HMI must facilitate this transition through robust, feedback-capable interaction modes and adaptive interface design. This transitional zone requires the establishment of clear UI standards to ensure safety. Reduction strategies, such as the „Now/In-a-while/Whenever” principle or the deliberate limitation of touch functionality during active driving, offer viable approaches to managing this shift effectively.

In conclusion, the model demonstrates that the choice of interaction mode cannot be considered independently of the usage context, functionality, and cognitive load. Particularly within the critical area, a standardized, safe, and manufacturer-defined interaction solution is essential to minimize risks and ensure a consistent and reliable UX.

5.3. Limitations

This section outlines the limitations that must be considered when interpreting the results of the study. A key limitation lies in the restricted scope of the data sources, which are confined to two online forums and can therefore inevitably narrow the breadth of user feedback. With a larger corpus of forum data, it is conceivable that additional or more nuanced results may emerge, potentially influencing the findings presented. Additionally, the use of (only) two online forums introduces a selection bias, as user perspectives form other platforms or cultural contexts are not represented in the findings. This limited diversity of input restricts the broader generalizability of the findings and will be addressed in future research of the study. Furthermore, while MotorTalk focuses primarily on German-language content and StackExchange provides an international perspective, the inclusion of additional forums to validate and triangulate the findings is deemed as not relevant, as the available datasets are considered sufficient in size for the initial phase of the analysis. Despite different national contexts, the analysis shows that the two forums reveal notable overlaps in certain user perspectives.

The quantitative analysis confirms a selection bias inherent in forum-based data, as discussions predominantly reflects neutral to negative experiences. While this bias facilitates the identification of challenges, positive feedback is comparatively underrepresented. A greater volume of positive accounts may reduce the relative weight of negative aspects and enable a more detailed examination of exemplary positive UX.

In addition, within the qualitative content analysis following Mayring’s approach, no intercoder validation of categories is conducted. This increases the degree of subjectivity in the results, as no external validation is applied. Future research should therefore include interview-based studies to verify the findings of this paper, which may either reinforce the current subjective tendencies or bring alternative perspectives into greater focus. Moreover, a large-scale survey can further strengthen the validity of the findings.

The proposed framework for control strategy is inherently preliminary, as it emerges from subjective user feedback. While this early conceptualization offers valuable insights into perceived interaction, it has not yet undergone systematic validation. However, due to limitations in time and resources, such an approach is beyond the scope of this first study.

6. Conclusions

The primary objective of this study was to identify additional challenges in current in-vehicle interaction and to translate these insights into actionable implications for future automotive UX. This objective was achieved through a systematic analysis of two active user-generated online forums—MotorTalk and StackExchange—using a mixed-methods approach that combined Mayring’s qualitative content analysis with NLP-based techniques. This mixed-method approach enabled the identification of recurring usability challenges and interaction barriers. The resulting insights were consolidated into a set of actionable implications and an resulting conceptual framework for control strategy. While these findings represent an initial foundation, validation through experts is planned for the next stage of the research. It has become evident that UX concepts in the automotive context can only succeed if they are adaptive, safety-oriented, and adapted to the diversity of users. Particular emphasis lies in the area of the critical point, where manufacturers bear a high degree of responsibility to ensure clarity, robustness, and intuitive operability. In contrast to the growing trend of delegating configuration decisions to users, a conscious and carefully curated selection of personalization options is required.

While the proposed methodology provides a structured foundation for deriving implications from user-generated content, its applicability is limited by the reliance on only two online forums, the subjective character of the conceptual framework, and the absence of expert validation. These constraints must be considered when interpreting the findings and will be addressed in subsequent stages of the research. Additional data sources, including further international forums, will be examined and evaluated to verify the initial first-stage findings and to identify potential cross-cultural differences. For further development of the findings, the next step involves validation through interviews and surveys with both drivers and domain experts to align and substantiate the derived implications, and to systematically explore and evaluate potential safety impacts. To ensure the robustness and practical applicability of the conceptual framework, subsequent research will involve targeted evaluations to refine the framework and thereby strengthen its empirical foundation. Future work may also integrate simulation-based approaches to assess interaction strategies under dynamic and safety-critical conditions. Incorporating such simulation methodologies will provide a scalable and empirically robust pathway for validating and refining the proposed framework [37]. Furthermore, it is important to examine how far the impact of UX on economic indicators ca be measured, particularly regarding the adequacy of existing metrics. This will help establish a well-founded, empirically supported UX framework that systematically connects the requirements of future mobility systems with the realities of users.

The proposed approach is intended to support early-phase development by providing a structured understanding of user needs, interaction challenges, and function relevance during the transition toward higher levels of automated driving. The framework can serve as a basis for classifying and prioritizing in-vehicle functions, thereby fostering a more systematic mindset for designing context-sensitive interaction strategies. The findings provide initial guidance for shaping future UX concepts and supporting early design decisions toward safer and more user-aligned interaction solutions in cars. These implications represent a preliminary foundation and will require systematic validation in the subsequent phases of the study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M. and C.W.; methodology, T.M. and C.W.; software, T.M. and C.W.; validation, T.M.; formal analysis, T.M.; data curation, T.M.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M.; writing—review and editing, T.M. and C.W.; visualization, T.M.; supervision, C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the exclusive use of publicly available user-generated content from online forums, which was processed in anonymized form without the collection or storage of personally identifiable information.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the exclusive use of publicly available and anonymized user-generated content from online forums, without the collection of personally identifiable information.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request. Please send your inquiries on christian.winkler@th-nuernberg.de and tobias.mohr@th-nuernberg.de.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ChatGPT v5 for the purposes of grammar correction, spelling adjustments, punctuation refinement, and translation. GenAI was additionally employed to optimize the self-developed framework for control strategy, which is presented in Section 5. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author Tobias Mohr is employed by BMW. This employment did not influence the design of the study; the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UI | User Interface |

| UX | User Experience |

| UGC | User Generated Content |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CEO | Chief Executive Officer |

| NLU | Natural Language Understanding |

| NLG | Natural Language Generation |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| BOW | Bag Of Words |

| TF-IDF | Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| POS | Part Of Speech |

| HTML | Hypertext Markup Language |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

| GenAI | Generative Artificial Intelligence |

| HMI | Human Machine Interface |

References

- ISO 9241-210:2019; Ergonomics of Human-System Interaction. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Fischer, H. Der Business Value von Usability und (User) Experience. 2021. Available online: https://www.eresult.de/whitepapers/business-value-ux/ (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- KPMG AG. Kundenerlebnis Verbessert Sich: Zufriedenheit von Kund:Innen Mit Customer Experience Stabilisiert Sich Nach Tiefwert Im Vorjahr. Available online: https://kpmg.com/de/de/home/media/press-releases/2024/12/ergebnisse-der-customer-experience-excellence-studie-2024.html (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Google. Available online: https://trends.google.com/trends/ (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Reid, C. Rejoice! Carmakers Are Embracing Physical Buttons Again. Available online: https://www.wired.com/story/why-car-brands-are-finally-switching-back-to-buttons/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Gao, S.; Lui, Y.; Kang, Y.; Zhang, F. User-Generated Content: A Promising Data Source for Urban Informatics. In Urban Informatics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneghello, J.; Thompson, N.; Lee, K.; Wong, K.W.; Abu-Salih, B. Unlocking Social Media and User Generated Content as a Data Source for Knowledge Management. 2020. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1907.11934 (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Bitkom e.V. Deutsche Wirtschaft Drückt Bei Künstlicher Intelligenz Aufs Tempo. Available online: https://www.bitkom.org/Presse/Presseinformation/Deutsche-Wirtschaft-drueckt-bei-Kuenstlicher-Intelligenz-aufs-Tempo (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- European Commission. The AI Continent Action Plan. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ai-continent-action-plan (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Bitkom e.V. Autokauf: Digitale Technologien Schlagen Marke Und Design. Available online: https://www.bitkom.org/Presse/Presseinformation/Autokauf-Digitale-Technologien-schlagen-Marke-und-Design (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Capgemini Research Institute. Besseres Kundenerlebnis Bietet Automobilherstellern Und Mobilitätsanbietern Weitere Möglichkeiten Zur Umsatzsteigerung. Available online: https://www.capgemini.com/de-de/news/pressemitteilung/studie-customer-experience-automobilindustrie/ (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Holzer, S. User Experience Im Auto. Available online: https://liechtenecker.at/blog/user-experience-im-auto (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Raasch, P. Gartner Digital Automaker Index 2024—So Digital Sind Automobilhersteller. Available online: https://www.autopreneur.de/p/gartner-digital-automaker-index-2024 (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Wuttke, L. NLP vs. NLU vs. NLG: Unterschiede, Funktionen Und Beispiele. Available online: https://datasolut.com/natural-language-processing-vs-nlu-vs-nlg-unterschiede-funktionen-und-beispiele/ (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Tseng, B.-H.; Cheng, J.; Fang, Y.; Vandyke, D. A Generative Model for Joint Natural Language Understanding and Generation. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5 July 2020; pp. 1795–1807. [Google Scholar]

- Vaish, R.; Kavlakoglu, E. NLP vs. NLU vs. NLG: The Differences Between Three Natural Language Processing Concepts. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/nlp-vs-nlu-vs-nlg (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Stryker, C.; Holdsworth, J. What Is NLP (Natural Language Processing)? Available online: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/natural-language-processing (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Schneider, D.; Jedlitschka, A. Deep Learning (DL) Und Große Sprachmodelle (LLM). Available online: https://www.iese.fraunhofer.de/de/trend/kuenstliche-intelligenz/deep-learning.html (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Grigoleit, S. Natural Language Processing; Europäische Sicherheit & Technik; Fraunhofer INT: Munich, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- The CEO Views. Comparing Deep Learning and Traditional Machine Learning. Available online: https://theceoviews.com/comparing-deep-learning-and-traditional-machine-learning/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Siebert, J.; Kelbert, P. Wie Funktionieren LLMs? Ein Blick Ins Innere Großer Sprachmodelle. Available online: https://www.iese.fraunhofer.de/blog/wie-funktionieren-llms/ (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Klofat, A. Wie Funktioniert Natural Language Processing in Der Praxis? Ein Überblick. Available online: https://www.bigdata-insider.de/wie-funktioniert-natural-language-processing-a-99498939918b0a9187000fb0a6bb433e/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Winkler, C. Wer, Wie, Was: Textanalyse Über Natural Language Processing Mit BERT. Available online: https://www.heise.de/hintergrund/Wer-wie-was-Textanalyse-mit-BERT-4864558.html (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Roch, S. Der Mixed-Methods-Ansatz. In Forschendes Lernen an der Europa-Universität Flensburg—Erhebungsmethoden; Zentrum für Lehrerinnen—und Lehrerbildung, Europa-Universität Flensburg: Flensburg, Germany, 2017; pp. 95–110. ISSN 2198-9516. [Google Scholar]

- MotorTalk. Community MotorTalk. Available online: https://www.motor-talk.de/suche.html?se=User+experience&ssa=posts&sob=relevance&search=Suchen&arf=true&arf=false&sfb0=-1&arn=false&snb0=-1&arb=false&arm=false&smb0=-1&sd=0&sdo=new&sdf=&sdt=&stk=&stf=1&suk=&suf=1&ssp=titleAndPosts&sep=20 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- UX.Stackexchange Community UX.Stackexchange. Available online: https://ux.stackexchange.com/questions/tagged/cars (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Jupyter Notebook. 2025. Available online: https://jupyter.org/ (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Guhr, O. German-Sentiment-Bert. 2020. Available online: https://huggingface.co/oliverguhr/german-sentiment-bert (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Cardiff NLP. Twitter-Roberta-Base-Sentiment. 2020. Available online: https://huggingface.co/cardiffnlp/twitter-roberta-base-sentiment (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- dataloop. German-Sentiment-Bert. Available online: https://dataloop.ai/library/model/oliverguhr_german-sentiment-bert/ (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- dataloop. Twitter Roberta Base Sentiment. Available online: https://dataloop.ai/library/model/cardiffnlp_twitter-roberta-base-sentiment/ (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution; GESIS: Klagenfurt, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI. ChatGPT. 2025. Available online: https://chatgpt.com/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Fox, M.P.; MacLehose, R.F.; Lash, T.L. Selection Bias. In Applying Quantitative Bias Analysis to Epidemiologic Data; Statistics for Biology and Health; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 75–103. ISBN 978-3-030-82673-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S. How To Use a Smartphone For Seniors—A Complete Guide. Available online: https://www.techandsenior.com/how-to-use-a-smartphone-for-seniors/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- SAE International. SAE Levels of Driving Automation Refined for Clarity and International Audience. Available online: https://www.sae.org/news/blog/sae-levels-driving-automation-clarity-refinements (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Zacharewicz, G.; Pirayesh-Neghab, A.; Seregni, M.; Ducq, Y.; Doumeingts, G. Simulation-Based Enterprise Management. Model Driven from Business Process to Simulation. In Guide to Simulation-Based Disciplines; Simulation Foundations, Methods and Applications; Springer Nature Link: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 261–289. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).