Featured Application

The “Double Circulation Double Diamond” design model that is the subject of this paper provides a systematic framework for the development of unmanned vehicles for the maintenance of highways. The model supports the identification of demand, the mapping of technology, and the optimisation of solutions to enhance both operational efficiency and safety.

Abstract

The objective of this study is to construct a “Double-Circulation Double-Diamond” model integrating AHP, QFD, and TRIZ. This will enable the resolution of contradictions between user requirements and technical solutions in the design of highway maintenance unmanned vehicles. The construction of an efficient, safe, and iterative systematic design framework will be achieved by following these steps. The model incorporates both internal and external feedback loops into the conventional Double-Diamond framework, thereby establishing a dynamic closed-loop process of “requirement identification—technical transformation—contradiction resolution—feedback optimization.” AHP is employed to conduct a hierarchical analysis of user requirements; QFD is utilized to map these requirements to technical characteristics; and TRIZ is integrated to facilitate innovative problem-solving and solution generation. The proposed model has been demonstrated to be an effective means of achieving requirement hierarchy decomposition, technical translation, and resolution of key contradictions. MATLAB R2025b (version 25.2.0) simulations were employed to verify the role of the external feedback loop in scheme iteration and optimization. This confirmed the A* algorithm as the optimal path planning approach, which achieves a balance between efficiency and safety. The fuzzy comprehensive evaluation yielded a score of 3.142, indicating performance between “well achieved” and “fully achieved”. In comparison with conventional linear development methodologies, the “Double-Circulation Double-Diamond” model has been shown to markedly enhance the systematicness and dynamic adaptability of complex equipment design through the utilization of cross-phase feedback and methodological coupling. This approach provides a transferable design framework applicable to highway maintenance, unmanned vehicles, and other complex engineering systems.

1. Introduction

With China’s expressway mileage now exceeding 160,000 km, the traditional maintenance mode that relies on manual inspection and mechanical operations has shown significant deficiencies in terms of efficiency, informatization, and safety [1,2]. The unmanned vehicle for highway maintenance, equipped with LiDAR, cameras and inertial navigation systems, represents a new type of intelligent equipment. It is capable of performing environmental perception, path planning, obstacle avoidance and remote monitoring. It offers significant advantages in terms of enhancing operational efficiency and safety [3].

In relation to the present state of research concerning the utilization of unmanned vehicles for the purpose of highway maintenance, scholars within the domestic and international research communities have achieved a certain degree of advancement. However, the majority of studies to date have been confined to specific technological advancements. For instance, Xu et al. proposed the concept of an automated maintenance system based on digital twins, while some domestic “intelligent inspection systems” have achieved automatic route planning and damage detection [4,5]. Nevertheless, in extreme conditions such as nocturnal periods, precipitation, or snowfall, challenges persist, including diminished recognition accuracy, unstable path planning, and delayed execution. It is evident that, at the system level, a mature architecture for multi-module collaboration and adaptability has yet to be established [6].

The design of highway maintenance unmanned vehicles involves multiple subsystems, including energy supply, driving mechanisms, transmission systems, control systems, and operational components, making it a highly complex process of system integration. According to the TRIZ Law of System Completeness, a technical system must include these elements to achieve functional integrity. However, existing studies have largely focused on individual modules, such as control or perception, and have paid insufficient attention to the holistic lifecycle perspective covering manufacturing, operation, maintenance, and decommissioning. This lifecycle perspective has been systematically elaborated in the context of autonomous buses; for example, Langner et al. proposed a comprehensive lifecycle model encompassing planning, development, operation, and retirement [7].

In recent years, lifecycle-oriented design frameworks have emphasized the integration of economic, environmental, and regulatory considerations throughout the product lifecycle. For instance, Ulrich et al. demonstrated how these factors can be incorporated into the early design stages of modular vehicle concepts [8]. Moreover, Malak et al. proposed a resource-efficiency–oriented lifecycle assessment approach in the commercial vehicle industry, further illustrating the applicability of this methodology to complex transportation equipment [9]. In the field of unmanned systems and robotics, Gupta et al. also demonstrated the feasibility of integrating lifecycle assessment into product–service system design [10].

Nevertheless, research on highway maintenance unmanned vehicles has primarily focused on algorithm optimization and user-centered design, with limited attention to system-level and lifecycle-oriented approaches. This research gap is particularly noteworthy, as a digitalized lifecycle framework has been proposed for highway infrastructure [11], providing guidance for extending lifecycle thinking to maintenance equipment.

Based on these insights, this study first uses the control and path-planning subsystems as representative research objects to validate the proposed methodological framework within a broader lifecycle context. These subsystems serve as effective testbeds for assessing the feasibility, adaptability, and iterative potential of the Double-Circulation Double-Diamond model, which will subsequently be extended to the full vehicle lifecycle design.

Methodologically, the Double Diamond Model was proposed by the British Design Council in 2005. The core logic of the process under discussion here follows a divergent–convergent process across the “problem space” and “solution space” [12]. This is a process which has been widely applied in the context of product innovation and service design, and which has gradually been extended to intelligent transportation and medical equipment design [13,14]. In the seminal paper by Nana Yaa Serwaah Sarpong et al., a pioneering approach was adopted by the introduction of an iterative feedback mechanism into the model [15]. This seminal innovation was undertaken with the objective of enhancing the model’s adaptability to complex systems. Researchers of Chinese origin have also endeavored to combine this model with user research and prototype iteration with a view to optimizing designs for kitchen appliances and campus unmanned vehicles [16,17]. Nevertheless, these explorations are generally confined to the single-product level. The absence of seamless stage transitions and feedback loops within the model gives rise to elevated costs associated with post hoc corrections, consequent to deviations in early-stage requirement definitions, thereby constraining its applicability in the domain of complex equipment system design.

The design of complex equipment is a multifaceted process that typically encompasses a multitude of objectives, constraints, and interdisciplinary interactions. This complexity necessitates the integration of diverse systematic methodologies to ensure optimal synergy and the effective management of the aforementioned challenges. The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), Quality Function Deployment (QFD), and the Theory of Inventive Problem Solving (TRIZ) are among the most commonly used methods [18]. Previous studies have applied the integration of AHP, QFD and TRIZ in the design of complex products, including rescue robots and snow vehicles. For instance, Li Xiaojie et al. effectively resolved conflicts between requirements and technology in the design of earthquake rescue robots [19], while Huang Shiwen et al. verified the feasibility of this approach in the development of dual-purpose snow vehicles [20]. However, the aforementioned studies predominantly adopted a one-way cascading logic paradigm, exhibiting a paucity of cross-phase iteration and feedback mechanisms. Consequently, the system’s adaptability and dynamic optimization capabilities remain constrained, impeding the facilitation of continuous improvement in intelligent equipment within complex environments.

In summary, extant research is subject to three main limitations:

(1) The conventional Double Diamond Model is deficient in terms of stage coupling and feedback mechanisms, which impedes dynamic iteration in complex systems.

(2) It is evident that methodologies such as AHP, QFD and TRIZ are predominantly implemented in a linear sequence, exhibiting a lack of cross-phase linkage and information feedback.

(3) The extant research on unmanned vehicles for highway maintenance has primarily focused on single-module optimisation, with a paucity of attention being given to the development of a systematic, closed-loop design framework.

In order to address the aforementioned issues, this study proposes a “Double-Circulation Double-Diamond” model. This model integrates multiple methodologies and feedback mechanisms in order to establish a dynamic closed-loop process from requirement identification to solution verification. The integration of AHP, QFD and TRIZ within the model facilitates effective requirement transformation and contradiction resolution, thereby providing a systematic design pathway for complex engineering equipment systems.

2. Methodology

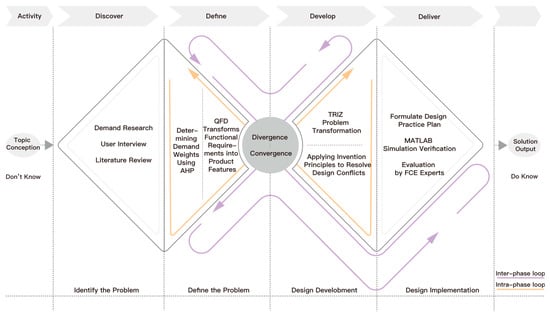

The “Double-Circulation Double-Diamond” model is a systematic approach to the design process, which is divided into four stages: Discovery, Definition, Development, and Delivery. This model incorporates feedback loops from both internal and external sources at each stage of the process. The internal loop facilitates real-time correction within a single phase, with this correction being based on data or validation results. In contrast, the external loop enables cross-phase retrospection and redefinition, thereby forming a dynamic and adaptive closed-loop system. The structure under discussion has been demonstrated to endow the design process with continuous optimization and self-correction capabilities. This renders it suitable for use in multi-constraint complex equipment systems, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Design process of highway maintenance unmanned vehicles based on the Double-Circulation Double-Diamond model.

This study specifically focuses on the control and path-planning subsystem of highway maintenance unmanned vehicles within the broader lifecycle design process. The proposed model is therefore applied to the design and optimization of key functional subsystems rather than the entire vehicle system.

(1) Discovery phase: The identification of core issues in maintenance operations is achieved through the utilization of questionnaires, interviews, and field research. This approach serves to elucidate the design requirements and functional boundaries of the unmanned vehicle. A comprehensive requirement list is established through the integration of literature and industry standards.

(2) Define phase: A mind-mapping approach is adopted to organize user needs and maintenance tasks, constructing a hierarchical structure of requirements. The AHP is a methodological framework employed to ascertain the relative importance of each requirement, while QFD facilitates the translation of high-priority needs into specific technical characteristics. The internal loop has been demonstrated to optimize weight distribution and indicator relationships, thereby achieving quantitative mapping from user needs to technical metrics.

(3) Develop phase: The results of the QFD analysis have enabled the identification of key conflicts. TRIZ is a method that is applied to establish contradiction function groups and generate innovative solutions. The external loop facilitates retrospection of the definition phase, enabling the refinement of requirements or technical indices. This process enables dynamic adjustment of innovative schemes.

(4) Delivery phase: The outcomes of preceding stages are integrated to complete the design of core modules. The external loop employs MATLAB R2025b (version 25.2.0) simulations to verify path planning and obstacle avoidance performance, while a fuzzy comprehensive evaluation is conducted to assess the overall design effectiveness. Should the results deviate from the target, scheme adjustments are made to ensure the feasibility and reliability of the design.

A comparison of the “Double-Circulation Double-Diamond” model with traditional linear processes and the standard Double Diamond model demonstrates significant advantages in iteration depth, requirement responsiveness, multi-method integration, and conflict resolution, as summarized in Table 1. The system’s internal and external loops facilitate intra-phase optimization and cross-phase retrospection, thereby circumventing design rigidity. Moreover, it facilitates extensive integration with AHP, QFD, TRIZ, and other methodologies, thereby providing systematic support for the design of complex systems. In scenarios involving multiple tasks and multiple conditions, such as the maintenance of highways by unmanned vehicles, the model achieves a balance between flexibility and overall coherence.

Table 1.

Comparative Analysis of Different Design Models.

3. Exploration Phase of the “Double-Circulation Double-Diamond” Model

The identification of the key issues in highway maintenance was the objective of the present study. To this end, contextual research was conducted, in addition to the administration of questionnaires and the analysis of accident data. The findings of the study indicate that manual inspection carries with it a number of significant safety risks and inefficiencies when undertaken in conditions of heavy traffic, during night-time operations, and in the presence of adverse weather conditions. Existing maintenance equipment is predominantly single-functional, with limited capacity to support multi-task operations or adapt to complex working environments.

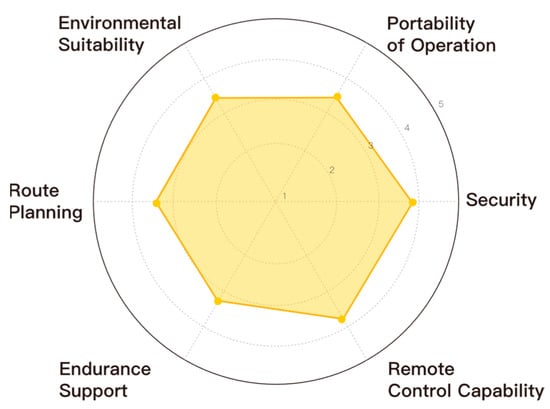

The findings from the interviews and questionnaires indicate that users primarily prioritize safety and remote control, while also anticipating that the unmanned vehicle should possess functions such as automatic obstacle avoidance, path planning, task switching, and status reporting. In the analysis of the 34 valid responses to the questionnaire, it was found that safety and remote control received the highest scores. However, it was also determined that there was still room for improvement with regard to operational convenience, endurance capability and path planning, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Attention to user demand for unmanned vehicles for highway maintenance.

The validity of these findings is further supported by accident statistics. Rear-end collisions caused by road debris account for 16% of total incidents. Furthermore, the accident rate during rain, snow, and nighttime is 2.3 times higher than during daytime, and the average emergency handling time exceeds 35 min. The findings of this study demonstrate the inherent limitations of manual maintenance when conducted in extreme environments or during emergency scenarios.

In summary, the exploration phase reveals the core design contradiction of highway maintenance unmanned vehicles: the system must ensure high reliability across all weather and road conditions, while simultaneously achieving multi-task collaboration and operational efficiency. These insights provide critical guidance for constructing the subsequent design framework.

4. Definition Phase of the “Double-Circulation Double-Diamond” Model

The objective of the definition phase is to translate user requirements into actionable design criteria that serve as the foundation for subsequent technical solutions. This is a process that builds on the key issues identified during the exploration phase. The present study proposes a novel integrated model that combines mind mapping, AHP, and QFD to establish a closed-loop pathway for systematic requirement structuring and technical mapping. Specifically, the Mind Mapping method is employed to categorize and hierarchize user needs; the AHP quantifies and ranks these needs to clarify priorities; and QFD maps the requirements to technical characteristics while revealing potential conflicts. In instances where discrepancies arise in weight calculation or mapping relationships, the internal feedback loop facilitates the correction of expert judgments and parameter settings, thereby achieving dynamic iteration between requirement structuring and technical translation.

4.1. Functional Requirement Analysis Based on the Mind Mapping Method

During the user research phase, this study first constructed a questionnaire based on six primary dimensions—safety, operational convenience, environmental adaptability, path planning, range assurance, and remote control—to gather intuitive feedback from frontline operators. Concurrently, through literature review and industry standard analysis, key constraints for unmanned high-speed maintenance vehicles were supplemented regarding regulations, safety requirements, and typical usage scenarios (e.g., Highway Maintenance Safety Procedures, FHWA Maintenance Guidelines), forming an initial pool of requirements.

Building on this foundation, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 10 experts possessing experience in road operation and maintenance and equipment manufacturing to supplement and refine the preliminary requirements set. Subsequently, mind mapping techniques were employed to categorize and structure the multi-source requirements, systematically organizing generic requirements from literature sources, compliance requirements from standards, and authentic operational needs derived from questionnaires and interviews [21].

Ultimately, through multiple rounds of expert consensus discussions, a hierarchical structure comprising four principal layers and 17 functional requirement indicators was established, as shown in Table 2. To enhance research reproducibility, Appendix A provides supplementary explanations on the source categories and rationale for each requirement.

Table 2.

Design Requirements List for Unmanned Vehicles for Expressway Maintenance.

4.2. Functional Requirement Weight Analysis Based on AHP

Based on the functional hierarchy established through the mind mapping method, the AHP was applied in this phase to quantitatively rank the design requirements [22]. The nine-level scale method was adopted in order to perform pairwise comparisons among the requirements and their sub-items, as illustrated in Table 3 [23]. The relative priority of each requirement within the overall design framework was determined by constructing the judgment matrix and calculating the corresponding weight coefficients. In order to guarantee the scientific validity and consistency of the results, a consistency ratio (CR) test was conducted. In this context, a CR of less than 0.1 was deemed to be acceptable. In instances where the CR exceeded the designated threshold or where substantial discrepancies were observed among the expert assessments, the process underwent iterative refinement through the inner feedback loop until stable and consistent results were attained. The resulting weights functioned as pivotal input parameters for the subsequent QFD-based requirement–technology mapping.

Table 3.

9-Level Scale Method [23].

Step 1: Construct the judgment matrix A, where the set of factors is defined as and the matrix represents the relative importance between factor and factor , satisfying , , and , as shown in Equation (1).

Step 2: Calculate the sum of each column of the judgment matrix A, as shown in Equation (2), where represents the matrix dimension and denotes the element in the row and column.

Step 3: Compute the normalized weights of the requirement indices, as shown in Equation (3).

Step 4: Perform the consistency check by calculating the maximum eigenvalue of the matrix, as shown in Equations (4) and (5).

The product of the judgment matrix A and the weight vector w is calculated to obtain , where denotes the i-th element of the resulting vector , and represents the i-th element of the weight vector w, as shown in equation.

Step 5: Conduct the consistency verification by evaluating the calculation results, as presented in Equation (6).

Refer to the average random consistency index RI shown in Table 4. For a judgment matrix of order , obtain the corresponding RI value from the table.

Table 4.

1–9 Consistency indicators of the judgment matrix [23].

The consistency ratio (CR) was calculated according to Equation (7).

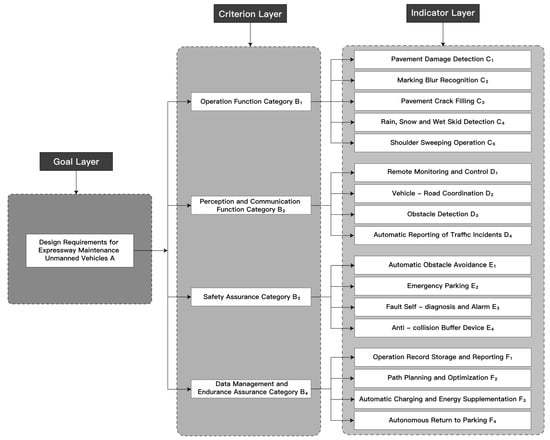

As illustrated in Figure 3, the requirements are arranged into a three-tier hierarchical structure. The goal layer signifies the overarching design objective, whilst the criteria layer is divided into four categories: operational functions, perception and communication, safety assurance, and data management. The indicator layer further refines these into 17 specific requirements. This hierarchical structure provides the foundation for subsequent AHP weight calculations.

Figure 3.

Hierarchy chart of target user needs for highway maintenance unmanned vehicles.

4.3. Iterative Application of the Internal Loop

During the weight elicitation process, a total of ten domain experts were invited to provide ratings. In the initial round of calculation, the consistency ratio (CR) of the criterion “Perception and Communication Functions” was determined to be 0.13, which exceeded the acceptable threshold of 0.1. Consequently, a requirement for revision through the internal loop was identified. The disagreement primarily stemmed from differing perceptions regarding the importance of “Remote Monitoring and Coordination.” Management emphasized its critical role in safety assurance. Conversely, some engineers considered the technology to be sufficiently mature and argued that it should not be assigned an excessively high weight.

In order to resolve the discrepancy, further illustration was provided to the expert panel of representative emergency takeover scenarios, thereby facilitating a shared understanding. Subsequent to this clarification, a consensus was reached, and the second-round calculation yielded a CR of 0.091 (<0.1), thereby successfully meeting the consistency criterion. The CR values of the remaining judgment matrices were all below 0.1, indicating satisfactory overall consistency (Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9).

Table 5.

Overall target layer A judgment matrix.

Table 6.

Criterion layer B1 judgment matrix.

Table 7.

Criterion layer B2 judgment matrix.

Table 8.

Criterion layer B3 judgment matrix.

Table 9.

Criterion layer B4 judgment matrix.

Finally, the weights of the criterion and indicator layers were multiplied and ranked to identify high-priority indicators, with the results summarized in Table 10.

Table 10.

Comprehensive weight and ranking of highway maintenance unmanned vehicle design demand indicators.

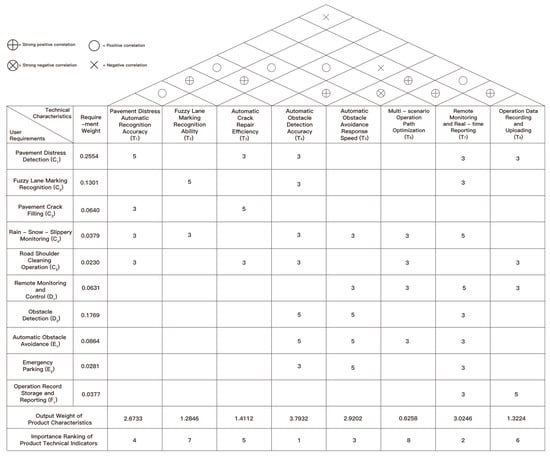

4.4. Transformation of Technical Requirements Based on QFD

The QFD method is employed to translate user requirements into technical characteristics [24]. This is achieved by systematically mapping user needs to technical features, on the basis of the AHP weighting results. In the QFD House of Quality, the function of the ‘left wall’ is to select the top 10 core requirements; the ‘ceiling’ lists 8 representative technical features; and the ‘roof’ indicates positive, negative or no correlation between features using symbols. The matrix cells are assigned values (1, 3, 5) according to the strength of the requirement–feature relationship, and are combined with requirement weights to calculate the importance of each technical feature [25].

Step 1: Let denote the weight of the -th requirement, and represent the correlation strength between the -th requirement and the -th technical feature. The weighted value of the -th feature is then calculated as shown in Equation (8).

Step 2: Normalize the weighted values to obtain the final importance weights.

4.5. Second Iteration of the Inner Loop: Application Example

In the initial QFD analysis, noticeable discrepancies were found in the weighting of technical characteristics, and the “roof” correlation matrix revealed distinct negative correlations, leading to expert disagreement over their interpretation and the corresponding weight allocation. To address this issue, a second internal iteration was conducted during the technical requirement transformation stage. Typical conflict scenarios were introduced, and expert re-evaluation was carried out to revise key parameters and ensure consistency.

The results indicate the presence of functional conflicts and resource competition among several technical characteristics. Automatic Obstacle Avoidance Response Speed (T5) and Multi-Scenario Path Optimization (T6) exhibited a strong negative correlation (−0.64) between real-time responsiveness and global optimization. Obstacle Detection Accuracy (T4) and Remote Monitoring and Reporting (T7) showed a moderate negative correlation (−0.52), reflecting the trade-off between accuracy and communication load, while Pavement Damage Recognition Accuracy (T1) and Data Recording and Upload (T8) presented a slight negative correlation (−0.47), implying a balance between system latency and data completeness. The strong negative correlation primarily represents a structural contradiction between real-time decision-making and global optimization, whereas the moderate and slight negative correlations stem from trade-offs in resource allocation and data transmission capacity. These relationships uncover the inherent interdependencies among multiple performance objectives and provide a logical basis for subsequent TRIZ-based contradiction resolution.

As shown in Figure 4, after adjustment, the importance levels of Obstacle Detection Accuracy (T4), Remote Monitoring and Reporting (T7), and Automatic Obstacle Avoidance Response Speed (T5) increased significantly, highlighting the dominant roles of safety monitoring and communication performance. The overall weight distribution became more balanced, and the model input was refined through iteration, offering more targeted data support for constructing the contradiction matrix in the TRIZ phase.

Figure 4.

Highway maintenance unmanned vehicle design quality house.

5. Development Stage of the Double-Circulation Double-Diamond Model

During the definition phase, AHP and QFD had already translated user requirements into technical features and revealed three critical conflict pairs (T5–T6, T4–T7, T1–T8) that, if unresolved, could constrain overall system performance. In order to address these conflicts, the development phase integrates the TRIZ. Specifically, the identified conflicts are mapped to 39 engineering parameters, and the corresponding inventive principles are selected using the TRIZ contradiction matrix. The results of this process are summarized in Table 11 [26,27].

Table 11.

TRIZ Problem Transformation and Solution Acquisition.

Despite specific environmental constraints and operational characteristics of unmanned high-speed maintenance equipment, this study confirms that all key functional requirements can be reasonably mapped within the traditional framework of 39 engineering parameters through a systematic comparison with TRIZ engineering parameters. Consequently, no expansion or adjustment to the original parameter set or contradiction matrix structure is required. This mapping outcome not only demonstrates the applicability of the classic TRIZ contradiction matrix in the field of road maintenance equipment but also provides a reference path for applying TRIZ methods across scenarios in other engineering systems.

5.1. Resolving Design Conflicts Through the Application of Inventive Principles

The findings suggest that the discordance between Autonomous Obstacle Avoidance and Path Optimization (T5–T6) can be mitigated by a harmonization of immediacy and global path planning through the implementation of the Preliminary Action (No. 10) and Dynamization (No. 15) principles. In the context of the Obstacle Detection and Remote Reporting (T4–T7) pair, the coordination of detection accuracy and communication bandwidth is facilitated by the Periodic Action (No. 19) and Discarding and Recovering (No. 34) principles. In the case of Pavement Damage Recognition and Data Upload (T1–T8), the Segmentation (No. 1) and Recovering (No. 34) principles serve to reduce redundancy and enhance data utilization. Overall, TRIZ provides a systematic approach for resolving design conflicts; however, further validation at the system level is required to ensure feasibility.

5.2. Solution Refinement and Validation Driven by the Outer Loop

The outer loop focuses on embedding TRIZ principles within the system context for iterative optimization, facilitating the transformation from theoretical solutions to engineering-feasible implementations. In the T5–T6 conflict, the Dynamization and Preliminary Action principles effectively balance real-time responsiveness with global path planning. However, this results in increased energy consumption, necessitating integration with smooth control strategies and redundancy design to enhance system stability. In the context of the T4–T7 conflict, the Periodic Action and Recovering strategies have been shown to alleviate bandwidth pressure. However, these strategies have also been observed to introduce potential delays under high-risk scenarios. Consequently, layered communication channels have been implemented to ensure the real-time reporting of critical information. In the T1–T8 conflict, Segmentation and Recovering reduce data volume, but over time, this may lead to congestion; this can be mitigated by adopting edge computing, transmitting only feature vectors to reduce communication load effectively.

In summary, the outer-loop feedback has been demonstrated to serve two primary functions. Firstly, it has been shown to address the limitations of TRIZ principles in practical implementation. Secondly, it has been demonstrated to effect a shift from single-conflict resolution towards system-level adaptability optimization. These functions provide a solid foundation for subsequent simulation and empirical studies.

5.3. Applicability and Comparative Analysis of Models

Compared to the V-model, spiral model, and systems engineering processes commonly used in autonomous vehicles, the “dual-loop double-diamond” model demonstrates greater efficiency in handling multi-demand coupling and technical conflicts. By introducing dual loops between demand convergence and technical resolution, this model exposes critical conflicts earlier and enables rapid iteration, making it particularly suitable for high-complexity projects such as multi-vehicle coordination, cross-scenario operations, and high-safety requirements. For maintenance fleets with stable requirements, limited budgets, or highly standardized tasks, the model’s full workflow may appear overly comprehensive. It can be simplified by trimming certain modules. Overall, this model demonstrates distinct advantages in complex system design scenarios while maintaining broad applicability and flexibility.

6. Delivery Phase of the Double-Circulation Double-Diamond Model

In the course of the delivery phase, the outcomes of the preceding stages—namely, requirement analysis, technical transformation, and conflict resolution—are integrated into a systematic design scheme. The implementation of high-priority functions is initiated through a weighting analysis, with subsequent refinement of conflict-resolution strategies through outer-loop feedback, resulting in the formulation of executable engineering measures. It is imperative to note that the inner loop persists in its operation during the validation of the prototype, thereby ensuring the feasibility and reliability of the design.

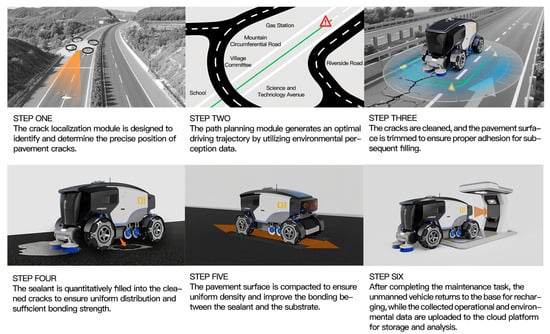

The development of an unmanned vehicle system for highway maintenance has been achieved. The system incorporates core capabilities, including autonomous navigation, environmental perception, and remote control. The vehicle is capable of performing diverse maintenance tasks, including crack sealing, shoulder cleaning, and rain–snow condition monitoring. As demonstrated in Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7, the overall system performance and operational workflow validate the practical applicability and effectiveness of the Double-Circulation Double-Diamond model in the design of complex engineering equipment.

Figure 5.

Design renderings of unmanned vehicles for highway maintenance.

Figure 6.

Highway maintenance unmanned vehicle workflow diagram.

Figure 7.

Interface diagram of the intelligent monitoring and management platform for highway maintenance unmanned vehicles.

6.1. Design Optimization and System Integration

In the delivery phase, the engineering solutions for various functional conflicts are integrated into a holistic design scheme. The system’s dynamic hierarchical obstacle avoidance is achieved through multi-sensor fusion, and it employs a dual-mode operation of cruise and fine-scan to balance task precision and efficiency. Core data are transmitted in real time, while auxiliary data are processed via edge computing and transmitted through layered channels to optimize bandwidth utilization.

In addition, the incorporation of outer-loop feedback has been demonstrated to introduce redundancy mechanisms and health-diagnosis functions, thereby enhancing system reliability. It is evident that the proposed framework has been shown to successfully transform theoretical design concepts into an engineering-feasible solution through multiple iterative verifications under the Double-Circulation Double-Diamond model. This highlights both methodological innovation and practical applicability.

6.2. Outer-Loop Verification Through MATLAB Simulation

After completing the requirements analysis, technology mapping, and conflict identification, this chapter constructs static and dynamic scenarios using MATLAB R2025b (version 25.2.0) to validate the effectiveness of the “Dual-Circulation Dual-Diamond Model” in optimizing path planning solutions. Multiple algorithms are compared through simulation to verify whether the key technology weights and conflict pairs derived from the model align with actual performance. Through a combined static and dynamic validation process, a closed-loop demonstration is achieved, bridging theoretical analysis and engineering simulation.

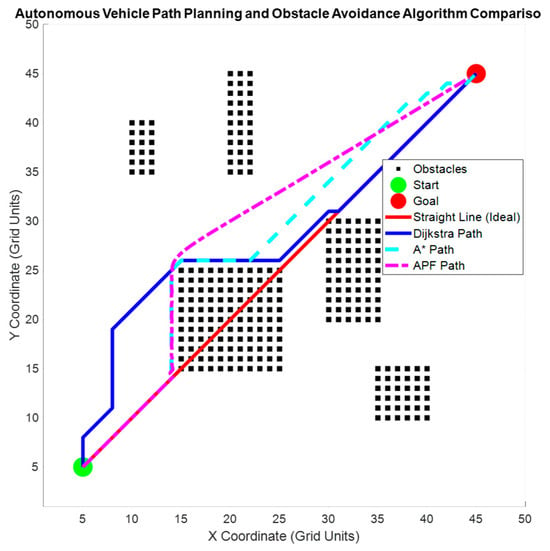

6.3. Static Scenario Simulation Construction

To evaluate the fundamental performance of different path planning algorithms under conditions without traffic flow interference, this study constructed a 50 × 50 static two-dimensional grid environment and completed simulations on the MATLAB R2025b (version 25.2.0) platform. Several fixed obstacles were placed on the map, with vehicles simplified as uniform-speed point mass models. The starting point and destination were located at the bottom-left and top-right corners, respectively. To objectively measure algorithm performance, this section evaluates four aspects: path length, smoothness, computational efficiency, and feasibility. Figure 8 displays the planning results of Dijkstra, A*, and the Artificial Potential Field (APF) method in this static environment. An ideal straight path is plotted for comparison, highlighting differences in deviation characteristics and smoothness during obstacle avoidance among the algorithms.

Figure 8.

Path Comparison of Three Path Planning Algorithms in Static Scenarios.

6.4. Analysis of Static Scenario Simulation Results

As shown in Figure 8, all three algorithms can generate feasible paths in static obstacle environments, but their performance differs significantly. Dijkstra’s algorithm achieves globally optimal paths but involves extensive search coverage, high computational cost, and paths with numerous abrupt turns, resulting in poor smoothness. A* significantly enhances search efficiency through heuristic functions, produces smoother paths, and offers the most balanced trade-off between path length and computational efficiency. APF exhibits the fastest computation speed but tends to oscillate or get stuck in local minima in densely obstructed areas, resulting in insufficient path stability. The path length results in Figure 9 further indicate that A* and Dijkstra produce similar path lengths, while APF yields slightly shorter paths. However, its instability limits its reliability for global path planning tasks.

Figure 9.

Comparison of Path Lengths Among Three Path Planning Algorithms.

In summary, A* achieves the optimal balance between path quality and computational efficiency, making it the most effective algorithm in static scenarios. Consequently, subsequent dynamic scenario simulations adopt A* as the primary reference to evaluate its adaptability under complex conditions such as multi-vehicle interactions and speed variations.

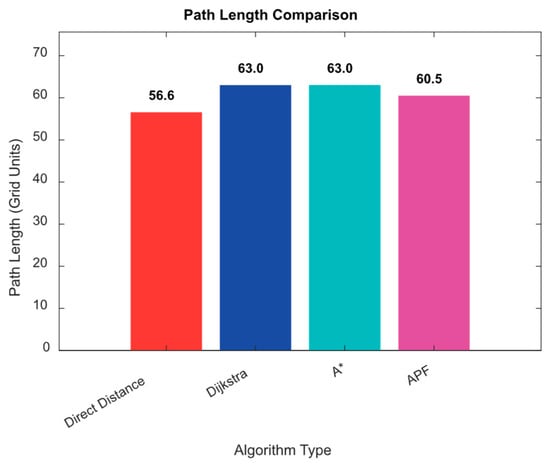

6.5. Dynamic Multi-Vehicle Interaction Simulation

To validate the adaptability of path planning solutions in real-world highway maintenance scenarios, this section constructs a dynamic traffic environment featuring multi-vehicle interactions, speed variations, and static obstacles. The focus is on evaluating the safety, stability, and trajectory convergence capabilities of different algorithms under complex conditions. Compared to static scenarios, dynamic traffic flows better demonstrate the role of external loops in solution optimization and feedback-driven processes. This also provides a foundation for engineering validation of TRIZ invention principles such as “pre-action” and “dynamicization”.

6.6. Dynamic Simulation Construction

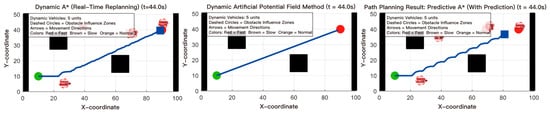

To validate the adaptability of path planning algorithms under multi-vehicle interaction conditions, this study constructed a two-dimensional dynamic traffic simulation environment in MATLAB R2025b (version 25.2.0), comprising a lead vehicle, dynamic obstacle vehicles, and static obstacles (as shown in Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12). The simulation area measures 100 m × 50 m. The lead vehicle travels from the left starting point toward the target point in the upper right, employing a point-mass model with limited acceleration.

Figure 10.

Comparison of Local Path Planning in the Early Stage of Dynamic Scenes (t = 10.5 s).

Figure 11.

Comparison of Local Path Planning in the Late Stage of Dynamic Scenes (t = 44.0 s).

Figure 12.

Comparison of Full-Path Planning Performance.

Three dynamic obstacle vehicles are positioned at their initial locations as shown in the figure, moving uniformly at different speeds along the longitudinal direction to simulate random traffic flow in high-speed maintenance scenarios. Two rectangular static obstacles, representing roadside facilities or work zone protective structures, are also placed to form impassable zones.

6.7. Analysis of Dynamic Scenario Simulation Results

Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12 illustrate the planning results of the three algorithms at different stages within the dynamic scene, while Table 12 provides a structured comparison of their performance.

Table 12.

Comparative Analysis of Dynamic Performance of Three Path Planning Algorithms at Three Critical Moments.

Results indicate that Dynamic A* exhibits path oscillation during complex interactions, while Dynamic APF demonstrates deviation and oscillation under potential field interference. Predictive A*, however, maintains a more stable and smoother trajectory throughout the entire journey, including both early and late stages. Overall, Predictive A* demonstrates higher robustness and consistency in handling multi-vehicle dynamic interference.

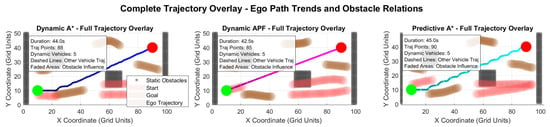

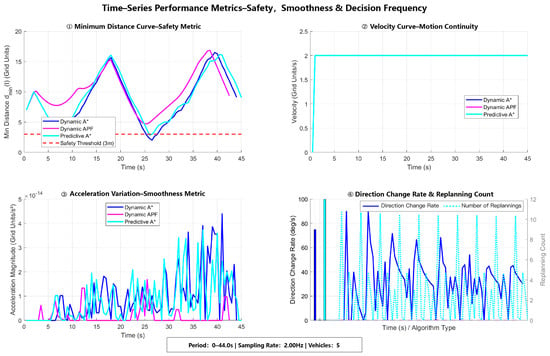

6.8. Dynamic Closed-Loop Performance Metrics Analysis

Figure 13 presents key timing metrics for the three algorithms in closed-loop simulation, including minimum safe distance, velocity and acceleration changes, rate of direction change, and number of replanings. These metrics quantify their safety, smoothness, and real-time performance in dynamic scenarios.

Figure 13.

Dynamic Closed–Loop Performance Metrics Analysis.

Results indicate that Predictive A* achieves optimal performance across metrics, including safety distance, velocity/acceleration fluctuations, and rate of direction change. In contrast, Dynamic A* and Dynamic APF exhibit instability during multi-vehicle interactions, manifesting as reduced safety distances and abrupt acceleration changes. Additionally, Predictive A* requires the fewest replanings, demonstrating superior trajectory consistency and computational efficiency.

In summary, the closed-loop metrics align with the trajectory comparison analysis, further validating that Predictive A* simultaneously achieves safety (T5), smoothness (T6), and real-time performance advantages in dynamic traffic scenarios.

6.9. Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation of the Design Method

After multiple iterations of internal and external cycles, the path planning scheme ultimately converged on a design strategy centered around Predictive A*. To further quantitatively assess the achievement level of this scheme, this paper employs the Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation (FCE) method, combined with indicator weights derived from the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the overall design scheme [28].

This study invited six domain experts to score 17 secondary indicators using a four-point scale (4 indicates full achievement, 3 indicates good achievement, 2 indicates basic achievement, 1 indicates no achievement). A fuzzy evaluation matrix was constructed, and fuzzy operations were performed in conjunction with the weight vector to obtain the comprehensive membership degree and overall evaluation results for the scheme. The evaluation results are shown in Table 13.

Table 13.

Summary of Indicator Item Evaluation.

Based on the aforementioned results, a weighted matrix of indicators and evaluation linguistic terms was constructed, and the membership degrees of each indicator were computed using a weighted averaging operator, as defined in Equation (10).

Consequently, the weights of the four evaluation linguistic terms were obtained, as presented in Table 14, and the comprehensive scores of the evaluations were subsequently calculated, as shown in Table 15.

Table 14.

Weight calculation results.

Table 15.

Comprehensive score calculation.

The findings suggest that the maximum membership level of the scheme has been fully achieved, with a comprehensive score of 3.142, indicating a high level of accomplishment. The majority of high-weight requirements, such as pavement damage monitoring, obstacle detection and autonomous obstacle avoidance, have been successfully met. However, certain low-weight indicators, including automatic energy replenishment and autonomous return, still offer potential for enhancement. The scheme under review achieves a balance between core requirements and engineering feasibility. It also serves to validate the methodological value of the “Double Circulation Double Diamond” model in feedback-driven iteration and solution optimization.

7. Conclusions

In the context of the growing intricacy of highway maintenance tasks and mounting demands for safety and efficiency, conventional design methodologies encounter notable limitations when it comes to the design of complex equipment such as unmanned vehicles for highway maintenance. These challenges include the management of multi-source requirements, the resolution of technical conflicts, and the achievement of system integration. In order to address this issue, the present paper puts forward a “Double-Circulation Double-Diamond” design model that integrates AHP, QFD, and TRIZ. This approach provides a systematic and dynamic framework for addressing the design challenges associated with the use of unmanned vehicles in highway maintenance.

The model establishes a dynamic closed-loop design process—“demand identification—technology transformation—conflict resolution—solution validation”—by introducing dual internal and external feedback loops within the traditional double-diamond framework. Specifically, the AHP is employed to hierarchically analyze user demands and determine their weights; QFD maps high-priority demands to technical features, identifying key conflicting pairs; TRIZ systematically resolves technical contradictions to generate innovative solutions; MATLAB R2025b (version 25.2.0) simulation and fuzzy comprehensive evaluation further validate the feasibility and superiority of the solution in path planning and system performance. The simulation and evaluation results demonstrate that this design model exhibits significant advantages in terms of demand response, conflict coordination, and system integration.

The theoretical contributions of this study are primarily reflected in the following four aspects:

(1) Innovative Model Architecture: The proposed “Dual-Cycle Dual-Diamond” design framework integrates structured phase segmentation with dynamic feedback loops, enhancing the systematic approach and iterative capability in complex equipment design.

(2) Method Integration Mechanism: The integration of AHP, QFD, and TRIZ methodologies into distinct design phases systematically bridges the transformation pathways from requirement analysis to technical considerations and solution implementation.

(3) Feedback Loop Design: The model’s adaptability and feasibility in complex scenarios are enhanced by achieving intra-phase refinement and inter-phase optimization through internal and external cycles.

(4) System Validation Framework: The integration of simulation experiments with fuzzy comprehensive evaluation is a key aspect of the methodology, with the objective being to achieve practical verification from theoretical design to engineering feasibility.

From a methodological perspective, this integrated model exhibits a clear hierarchical structure: the internal cycle ensures information consistency within each stage, while the external cycle enables cross-stage requirement tracing and solution iteration. This configuration not only enhances the interpretability of the model but also provides a foundation for its extension to other complex system designs.

Although this study established a comprehensive design framework and validated its effectiveness, several limitations remain that warrant further investigation. First, AHP, QFD, and FCE rely on expert judgments, which inevitably introduce subjectivity. While the internal loop improves the consistency ratio (CR) of AHP, this primarily enhances agreement among experts rather than the objectivity of the evaluation. Future research could address this by: (1) integrating digital twin technology or high-fidelity vehicle dynamics models to construct engineering simulations that better reflect real-world conditions, and (2) incorporating data-driven approaches, such as accident statistics, sensor data, or machine learning-based dynamic weight adjustment, to reduce dependence on expert experience.

Furthermore, although the simulation environment reflects typical operational conditions, it simplifies dynamic traffic flow, vehicle interactions, and complex scenarios, limiting its representation of actual highway environments. Future work could leverage real traffic data or more sophisticated scenario modeling to improve the generalizability and reliability of the results. Finally, the current framework does not yet consider life-cycle indicators such as cost, energy consumption, and long-term operation and maintenance. Incorporating these factors would support a more comprehensive decision-making system for practical applications.

In summary, the “Double-Circulation Double-Diamond” design model proposed in this paper provides systematic, iterative, and integrated verification methodological support for the development of complex intelligent equipment such as unmanned highway maintenance vehicles. The product under discussion combines theoretical innovation with practical engineering value.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W.; Methodology, Y.C.; Writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; Writing—review and editing, H.W., S.S. and Y.C.; Investigation, S.S. and Y.T.; Formal analysis, S.S.; Supervision, Y.C.; Project administration, H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Education of Hubei Province (grant numbers Q20231401) and Hubei University of Technology (grant number XJ2023002401).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| No. | Functional Requirement | Source Category | Justification/Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | Pavement damage detection | Literature + Industry Standards | Road condition assessment is a core task in maintenance; the Highway Technical Condition Evaluation Standard requires timely detection of surface defects. |

| C2 | Fuzzy lane marking recognition | Literature + Expert Feedback | Autonomous driving relies on lane markings; experts emphasized that lane fading is common in real maintenance scenarios. |

| C3 | Pavement crack filling | Industry Standards + Experts | Crack filling is a routine maintenance activity; experts identified it as one of the most frequent tasks. |

| C4 | Wet/slippery surface detection | Literature + Standards | Wet and slippery surfaces affect vehicle dynamics; maintenance guidelines require post-rain/snow surface condition assessment. |

| C5 | Shoulder cleaning operation | Standards + Expert Feedback | Shoulder cleaning is an essential task in highway maintenance; experts noted the necessity of unmanned execution. |

| D1 | Realize remote video monitoring and management | Standards + Experts | Maintenance safety regulations require remote monitoring; experts highlighted the need for centralized fleet supervision. |

| D2 | Vehicle-road coordination | Literature | V2X communication improves safety and event-response time, widely studied in ITS and autonomous driving research. |

| D3 | Obstacle detection | Literature + Experts | Obstacle detection is a baseline safety requirement; experts emphasized frequent random obstacles in actual highway environments. |

| D4 | Automatic traffic Incident reporting | Industry Standards | Highway management regulations require automatic reporting of detected incidents to improve coordination efficiency. |

| E1 | Automatic obstacle avoidance | Literature | Core capability in autonomous driving; essential for safe operation of unmanned maintenance vehicles. |

| E2 | Emergency stop | Standards + Experts | Maintenance vehicles must include emergency braking mechanisms; experts confirmed this as a critical safety requirement. |

| E3 | Fault self-diagnosis and alarm | Literature + Experts | Diagnostics and fault reporting are widely emphasized in robotics; experts noted that downtime causes high operational losses. |

| E4 | Collision buffer device | Industry Standards | Highway maintenance vehicles are required to be equipped with impact attenuators; same safety requirement applies to unmanned scenarios. |

| F1 | Operation recording And reporting | Standards + Experts | Regulatory bodies require maintenance records; experts noted frequent omissions in manual logging. |

| F2 | Path planning and optimization | Literature | Fundamental capability of autonomous robots and unmanned vehicles; directly affects efficiency and safety. |

| F3 | Automatic charging | Literature + Experts | Long-duration tasks require unmanned energy replenishment; experts stated that manual battery swapping is impractical. |

| F4 | Autonomous return and parking | Literature + Standards | Common feature in autonomous vehicle systems; maintenance regulations require vehicles to return safely to designated parking areas after operation. |

References

- China Artificial Intelligence Industry Technology Maturity White Paper (2022 Revised Edition). Available online: https://szai.sjtu.edu.cn/upload/down/zhongguorengongzhinengchanyejishuchengshudubaipishu2022jingbianban.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Highways Become a Fantastic Window on China’s Development, Vitality. Available online: https://en.people.cn/n3/2021/0608/c90000-9858725.html (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Yang, X.; Wu, F.; Li, R.; Yao, D.; Meng, L.; He, A. Real-Time Path Planning for Obstacle Avoidance in Intelligent Driving Sightseeing Cars Using Spatial Perception. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Anvo, N.; Taha-Abdalgadir, H.; D’Avigneau, A.; Palin, D.; Wei, R.; Hadjidemetriou, G.; Schaefer, S.; De Silva, L.; Al-Tabbaa, A.; et al. Highway digital twin-enabled Autonomous Maintenance Plant: A perspective. Data-Centric Eng. 2024, 5, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Application of Intelligent Inspection System in Highway Maintenance. Mod. Traffic Bridge Constr. 2025, 4, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathee, M.; Bacic, B.; Doborjeh, M. Automated Road Defect and Anomaly Detection for Traffic Safety: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 5656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langner, C.; Rehberg, M.; Roth, D.; Kreimeyer, M. A Lifecycle Model for Autonomous Buses in Public Transport. In Proceedings of the 26th International Dependency and Structure Modeling Conference (DSM 2024), Stuttgart, Germany, 24–26 September 2024; pp. 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, C.; Feinauer, M.; Bieber, K.; Schmid, S.A.; Friedrich, H.E. Life Cycle Analysis of an On-the-Road Modular Vehicle Concept. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malak, R.C.; Adam, M.; Waltemöde, S.; Aurich, J.C. Lifecycle Oriented Assessment of Resource Efficiency in the Commercial Vehicle Industry. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 907, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Syré, A.; Okhovat, R.; Göhlich, D. Integrating Life Cycle Assessment in Product Service System Design: Use Case for Robots in Waste Management. Proc. Des. Soc. 2025, 5, 2111–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Gao, J.; Wang, L.; Zhu, J.; Li, W. A Framework of Life-Cycle Infrastructure Digitalization for Highway Asset Management. Sustainability 2025, 17, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyykkö, H.; Suoheimo, M.; Walter, S. Approaching Sustainability Transition in Supply Chains as a Wicked Problem: Systematic Literature Review in Light of the Evolved Double Diamond Design Process Model. Processes 2021, 9, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banbury, A.; Pedell, S.; Parkinson, L.; Byrne, L. Using the Double Diamond model to co-design a dementia caregivers telehealth peer support program. J. Telemed. Telecare 2021, 27, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viviani, S.; Gulino, M.-S.; Rinaldi, A.; Vangi, D. An Interdisciplinary Double-Diamond Design Thinking Model for Urban Transport Product Innovation: A Design Framework for Innovation Combining Mixed Methods for Developing the Electric Microvehicle “Leonardo Project”. Energies 2024, 17, 5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpong, N.Y.S.; Akowuah, J.O.; Amoah, E.A.; Darko, J.O. Enhancing cassava grater design: A customer-driven approach using AHP, QFD, and TRIZ integration. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Zhou, L. Innovative Design of Kitchen Appliances Based on the Double Diamond Model. Packag. Eng. 2025, 46, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G. Research on the Design of Campus Unmanned Delivery Vehicles Based on the Double Diamond Model. Master’s Thesis, Beijing University of Chemical Technology, Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Apichonbancha, P.; Lin, R.-H.; Chuang, C.-L. Integration of Principal Component Analysis with AHP-QFD for Improved Product Design Decision-Making. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.L.; Liang, J.; Li, H.Q. Design of an Earthquake Rescue Robot Based on AHP/QFD and TRIZ. J. Mech. Des. 2021, 38, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.W.; Zhu, Z.X.; Guo, Y. Research on the Styling Design of a Dual-Purpose Snowmobile Based on AHP/QFD/TRIZ. Packag. Eng. 2023, 44 (Suppl. S1), 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzan, T.; Buzan, B. The Mind Map Book: Unlock Your Creativity, Boost Your Memory, Change Your Life; BBC Active: London, UK, 2006; pp. 1–352. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Z. Development of a Rehabilitation Chair Design Based on a Functional Technology Matrix and Multilevel Evaluation Methods. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhu, X.; Chen, Y.; Kong, Q. Evaluation and design of dining room chair based on analytic hierarchy process (AHP) and fuzzy AHP. BioResources 2023, 18, 2574–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yu, Z.; Li, M.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, H. An entropy-based fuzzy QFD model on used product remanufacturing design. Green Manuf. Open 2024, 2, 103101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Tao, X.; Gong, J.; Wang, F. Quality function deployment approach to urban ecological public art design centred on resident needs. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.M.; Tsang, Y.P.; Chong, W.W.; Au, Y.S.; Liang, J.Y. Achieving eco-innovative smart glass design with the integration of opinion mining, QFD and TRIZ. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sala, A.J.; Felez, J.; Cano-Moreno, J.D. Efficient Railway Turnout Design: Leveraging TRIZ-Based Approaches. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 79531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W. Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation and Its Application in Engineering Management; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).