Abstract

Unsupervised learning methods significantly benefit various practical applications by effectively identifying intrinsic patterns within unlabelled data. However, inherent data noise and uncertainties often compromise model reliability, result interpretability, and the overall effectiveness of unsupervised learning strategies, particularly in complex fields such as biomedical, engineering, and physics research. To address these critical challenges, this study proposes SUN (Stochastic UNsupervised learning), a novel approach that integrates probabilistic unsupervised techniques—specifically Gaussian Mixture Models—into the RUN-ICON unsupervised learning algorithm to achieve optimal clustering, systematically reduce data noise, and quantify inherent uncertainties. The SUN methodology strategically leverages probabilistic modelling for robust classification and detection tasks, explicitly targeting particle dispersion scenarios related to environmental pollution and airborne viral transmission, with implications for minimising public health risks. By combining advanced uncertainty quantification methods and innovative unsupervised denoising techniques, the proposed study aims to provide more reliable and interpretable insights than conventional methods while alleviating issues such as computational complexity and reproducibility that limit traditional mathematical modelling. This research contributes to enhanced trustworthiness and interpretability of unsupervised learning systems, offering a robust methodological framework for handling significant uncertainty in complex real-world data environments.

1. Introduction

Unsupervised learning (UL) holds a central position within the broader field of machine learning due to several intrinsic advantages [1,2,3,4]. Chief among these is its independence from labelled data, a valuable characteristic given the significant resources and manual effort typically required to obtain high-quality annotated datasets [5]. By operating effectively without reliance on labels, UL enhances access to vast amounts of unlabelled, real-world data, thereby overcoming a prevalent bottleneck in supervised learning. Moreover, unsupervised methodologies aid in identifying intrinsic structures and hidden patterns within complex datasets, enabling researchers and practitioners to conduct insightful exploratory analyses and cultivate a deeper, data-driven understanding [6,7].

The practical implications of UL methodologies are extensive and span numerous areas, showcasing their versatility and relevance in contemporary artificial intelligence applications [8,9,10,11]. In clustering applications, techniques such as K-means and hierarchical clustering effectively facilitate market research, customer segmentation, anomaly detection, and the content-based organisation of documents and images [12,13,14,15,16,17]. Dimensionality reduction techniques—including principal component analysis (PCA), manifold learning methods, and autoencoder networks—are essential for simplifying data representations, optimising computational efficiency, visualising complex data relationships, and enhancing subsequent supervised modelling tasks [18,19,20,21]. Moreover, the role of UL is increasingly apparent in anomaly detection, particularly in fields that require the identification of fraudulent activities, security breaches, and quality control deviations [22,23,24]. Advancements in generative modelling, notably Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), diffusion models, and deep generative autoencoders, offer powerful tools for creative generation, data synthesis, and augmentation tasks, which increasingly form the foundation of modern machine-learning frameworks [25,26,27,28,29]. Finally, unsupervised association-based methods significantly impact recommendation and decision support systems, especially in e-commerce and digital service delivery contexts [30,31,32].

Concurrently, self-supervised and contrastive learning paradigms (such as SimCLR, MoCo, and BYOL) have emerged as leading directions, producing high-quality data representations and substantially increasing model accuracy and generalisation in downstream tasks [33,34,35,36]. Transformative developments in sequential and linguistic data representation rely on transformer-based frameworks, demonstrating the prominence of large-scale, unsupervised transformer models such as BERT, GPT, and masked language models [37,38,39]. Simultaneously, progress in graph-based neural architectures, including graph neural networks (GNNs) and graph autoencoders (GAEs), has enhanced unsupervised representation learning and pattern discovery in relational and networked data [40,41,42,43].

Reducing data noise and uncertainty is a focal area across the entire machine learning spectrum. Within generalised machine learning practices, effectively managing data noise enhances model accuracy, improves interpretability, and fosters model robustness and reliability [44,45]. Importantly, noise reduction improves the validity of resulting models and makes actionable insights more readily interpretable by practitioners, thereby supporting informed decisions with greater confidence. In the context of UL in particular, addressing data quality concerns becomes even more significant due to the absence of supporting labelled information; here, unsupervised algorithms depend primarily on intrinsic patterns in the data, which can easily become obscured by excess noise and uncertainty [46,47,48]. Consequently, effectively controlling and reducing data noise and uncertainty is integral to ensuring reliable identification of meaningful structures and thus maintaining confidence in subsequent conclusions.

The current literature identifies numerous state-of-the-art methods explicitly developed to mitigate data noise and manage uncertainty. For data noise reduction, advanced filtering techniques—including median and adaptive filters, wavelet transforms, and non-local means algorithms—remain standard and effective approaches [49,50]. Alongside these traditional techniques, modern deep denoising autoencoders and GAN-based denoising methods (such as Noise2Noise and Noise2Void) increasingly demonstrate superior performance [51,52,53]. Likewise, self-supervised denoising schemes enable adaptation to tasks lacking explicit ground truth, expanding effectiveness and applicability across diverse data types and domains [54]. Approaches specifically designed to quantify, reduce, and manage uncertainty notably include Bayesian methodologies—employing Bayesian neural networks, Gaussian processes, probabilistic graphical models, and approximate inference techniques—which explicitly model and quantify uncertainty in predictions [55,56,57]. Additionally, Monte Carlo dropout and deep ensemble techniques provide reliable estimates of model uncertainty, enabling efficient uncertainty quantification [58,59]. Calibration methods such as temperature scaling, Platt scaling, and label smoothing further refine model confidence estimates, significantly reducing uncertainty and facilitating safer, more robust decision-making in real-world artificial intelligence deployments [60,61,62]. Recent advances in uncertainty-aware clustering have further shaped the landscape. Bayesian Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs) extend traditional GMMs by placing priors on parameters, enabling robust uncertainty quantification [63]. Variational Deep Clustering methods, such as VaDE [64] and IDEC [65], combine deep learning with probabilistic frameworks to handle complex data distributions. In [66], a comprehensive framework for uncertainty estimation in deep clustering is proposed.

In light of the above, despite the success and potential of UL algorithms, fields such as biomedical engineering and physics applications face heightened uncertainty, primarily due to incomplete scientific understanding and inherent data complexities [67,68]. This challenge underscores the need to explicitly integrate probabilistic methods that quantify uncertainty, thereby improving the interpretability and robustness of results. Therefore, recognising the prominence and rapid advancement of UL, along with the crucial importance of optimising data quality, controlling noise, and reducing uncertainty, the present research aims to comprehensively and critically examine these vital aspects to enhance the current understanding of unsupervised methodologies and their robustness in challenging data environments.

This study addresses the challenges above by integrating UL and probabilistic methodologies, namely the “Reduce UNcertainty and Increase CONfidence” (RUN-ICON) algorithm and Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs), to mitigate data noise and reduce uncertainty. The resulting algorithm is called the “Stochastic UNsupervised learning” (SUN) algorithm. This topic is significant for detecting and classifying particle dispersion that may be associated with pollution or viral carriers, aiming to minimise public health risks (see, e.g., [69]). Historically, while beneficial, traditional mathematical models require computationally intensive simulations and face challenges regarding reproducibility and validation against experimentally observed data, exacerbating the intrinsic uncertainties in their outputs. The paper is organised as follows: Section 2 presents the two components and implementation of the SUN algorithm. In Section 3, results are presented from the application of the algorithm on four distinct datasets (three two-dimensional and one multimodal), where the optimal clustering is known a priori and its performance is evaluated. Finally, in Section 4, conclusions are drawn, and suggestions for further work are provided.

2. The SUN Algorithm

SUN is a two-stage procedure that combines stability-driven selection of cluster structure with probabilistic assignments. The first stage, RUN-ICON, searches over a range of K values and identifies centres that recur across many K-means++ runs. The second stage fits a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) with K components initialised at those centres and returns soft memberships. The full GMM specifications are provided in Appendix A.

2.1. Design Rationale

Cluster analysis often requires a choice of K and can be sensitive to initialisation. RUN-ICON addresses this by favouring settings that are reproducible under repeated random restarts. The GMM then models cluster shape and overlap, yielding assignment probabilities. This separation of roles leads to stable centre selection followed by uncertainty-aware labelling.

2.2. RUN-ICON, Stability Score, and Selection Rule

Despite its broad utility across application areas [70,71,72,73], unsupervised clustering for particle data faces recurring pain points: sensitivity to initialisation and hyperparameter settings, dependence on feature choice and scaling, susceptibility to high dimensionality, and computational burdens at scale [74]. RUN-ICON tackles these issues by casting model selection and centre identification as a stability problem [48]. For each candidate K, we perform many K-means++ fits, pool the resulting centres, and locate dominant centres through the Generalised Cluster Coordinate (GCC) as recurring modes in this centre set under a small matching tolerance . We then compute a Clustering Dominance Index , defined as the proportion of runs that recover the same dominant configuration, and repeat this outer procedure several times to obtain a distribution of values. An accompanying uncertainty score summarises the spread of these values. The selected K maximises the mean subject to a bound on , with ties broken in favour of lower uncertainty. In practice, this replaces ad hoc elbow rules or single-run SSE heuristics with a reproducibility criterion, prioritises cluster structures that recur under random restarts, and reduces the influence of outliers and background noise. The resulting dominant centres serve as a stable representation of the data structure and as initialisation for the probabilistic stage of SUN. The capabilities of the algorithm have been demonstrated in several previous studies [75,76,77]. The steps of the algorithm for each candidate K are as follows:

- Draw R K-means++ initialisations and fit K-means for each.

- Aggregate the R sets of centres and identify dominant centres by mode seeking under a small distance threshold in the centre space.

- Compute a stability score, , as the fraction of runs whose fitted centres match the same set of dominant centres within .

- Repeat the previous steps M times to obtain a sample of values and summarise their spread by an uncertainty measure , i.e., the difference between upper and lower CDI bounds across outer repeats.

Select that maximises the mean subject to a cap on , then break ties by the smallest . The associated dominant centres are used as the representative solution for .

2.3. Gaussian Mixture Models

2.3.1. Stochastic Modelling—Mathematical Theory

The GMM is a widely used probabilistic clustering method that can refine and enhance the output of preliminary clustering algorithms [78,79,80,81]. Its integration within UL pipelines often leads to more accurate predictions and clearer insights into complex data. The GMM offers several advantages that make it well-suited in this context. By modelling data as a mixture of Gaussian components, it can represent underlying sub-populations more accurately than simpler approaches [82]. Its ability to accommodate clusters of varying shapes, scales, and orientations enhances performance on heterogeneous real-world data [83]. The GMM also provides probabilistic membership estimates for each data point [84], allowing explicit quantification of uncertainty. Furthermore, its formulation as a weighted sum of Gaussian distributions yields an interpretable representation of latent structure [85]. The GMM can be integrated into hybrid or domain-specific machine learning frameworks [86,87], thereby strengthening predictive accuracy by combining complementary techniques. Finally, because many datasets are inherently multimodal, the GMM is especially effective in modelling multiple modes through distinct Gaussian components [88]. These properties make the GMM a powerful tool for improving UL results, particularly in high-complexity or high-stakes settings.

In the present work, the GMM is employed to refine the cluster centres produced by a preceding clustering stage. While K-means inherently favours spherical, similarly sized clusters [89], the proposed SUN algorithm overcomes this limitation by using GMM to represent each cluster with its own mean and covariance structure. The mathematical formulation is provided in the following section. Importantly, the dominant number of clusters remains stable across iterations, as predicted by RUN-ICON.

2.3.2. Setting up the GMM Framework

The GMM assumes data points are sampled from multiple Gaussian distributions [90]. For a dataset of N points separated into K clusters, we define cluster means (Equation (A1)), covariance matrices (Equation (A2)), and weights . The Gaussian distribution for cluster k follows the standard formulation [91], with membership probabilities given by Equation (A5). For the complete set of equations, see Appendix A.

2.3.3. Expectation–Maximisation (EM) Algorithm

We now fix and initialise the K mixture means at the dominant centres from RUN-ICON and covariances and weights from empirical moments. We now proceed to present the EM algorithm, which computes maximum-likelihood estimates for Gaussian distributions in the GMM-based clustering framework. This algorithm iterates between two key steps: the Expectation (E) step and the Maximisation (M) step.

- E-step. In this step, we compute the probability that a given data point belongs to cluster k. We evaluate K probabilities for each point corresponding to its membership in any of the K clusters. The highest probability determines the assignment of the point to a cluster. Consequently, a point may be reassigned to a different cluster than it was originally associated with.

- M-step. This step involves reassigning points to clusters and updating cluster parameters. The means, covariance matrices, and weights are recalculated based on the newly assigned points, using Equations (A1), (A2) and (A4), respectively. While the number of clusters K remains unchanged, their centres are adjusted to reflect the updated means.

2.4. Default Settings and Diagnostics

Unless stated otherwise, we use , K-means++ runs per K and outer repeats, a matching tolerance , and an uncertainty cap . For the EM procedure, we adopt standard convergence criteria unless otherwise stated. Specifically, the covariance matrices are regularised by adding a diagonal term of magnitude to ensure numerical stability, and iterations are terminated when the relative change in the log-likelihood falls below , with a maximum of 100 iterations. In cases where the estimated covariance matrices become poorly conditioned, the diagonal regularisation is increased up to ; if convergence slows, the log-likelihood tolerance is tightened to and the iteration limit is raised to 200. We report with uncertainty bars, along with GMM responsibilities in the near-boundary and central regions.

2.5. Implementation Steps of the SUN Algorithm

Now, we will outline the implementation steps of the SUN algorithm, which integrates the RUN-ICON method to determine the optimal number of clusters and their corresponding centres. Once the optimal clustering configuration is identified, we apply the GMM to estimate the cluster boundaries. The following steps summarise the process:

- Initialisation with RUN-ICON

- EM algorithmExecute the EM algorithm to refine the GMM parameters:

- E-step: Calculate the probabilities for all points to belong to any of the k clusters.

- M-step: Redistribute points in K clusters based on highest probability scores and recalculate , , and .

- Check for convergenceTo check for convergence, the previously and newly calculated means are compared. If they are below the user-set tolerance, the algorithm terminates. Otherwise, we return to Step 2 and repeat.

Table 1 summarises how SUN differs from existing hybrid clustering methods.

Table 1.

Comparison with existing hybrid clustering methods.

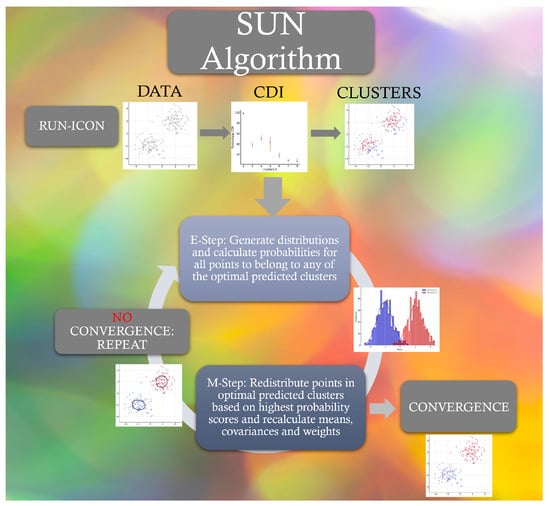

The key innovations of SUN include (i) systematic optimal cluster number determination via RUN-ICON, (ii) explicit uncertainty quantification through CDI metrics, and (iii) dual-phase noise reduction combining statistical filtering and probabilistic smoothing. We thus obtain a robust clustering algorithm that leverages RUN-ICON’s ability to identify dominant clusters and the GMM’s flexibility for modelling complex data distributions. The EM algorithm iteratively refines the parameters, resulting in more precise and reliable clustering outcomes. Figure 1 schematically presents the steps of the SUN algorithm. The pseudocode for the algorithm is given in Appendix B. Its capabilities will be demonstrated in the following section, where four different datasets will be tested.

Figure 1.

The SUN algorithm.

2.6. Theoretical Convergence Properties and Noise Suppression

2.6.1. Convergence Analysis

The SUN algorithm’s convergence is guaranteed through the following properties:

- RUN-ICON Convergence: The algorithm converges to dominant cluster centres through statistical mode-seeking. Let denote the cluster centres from the i-th iteration. The dominance frequency converges to a maximum as :where represents the true cluster centres.

- GMM-EM Convergence: The EM algorithm guarantees a monotonic increase in log-likelihood:where represents the GMM parameters.

- Combined Convergence: The SUN algorithm converges when

2.6.2. Noise Suppression Mechanism

SUN reduces noise through two complementary mechanisms:

- Statistical Filtering (RUN-ICON): By aggregating multiple K-means++ runs, random initialisation effects are averaged out:

- Probabilistic Smoothing (GMM): The soft assignment probabilities act as a low-pass filter:where is a threshold determined by the cluster covariance structure.

3. Results and Discussion

To ensure a comprehensive evaluation of the algorithm, we utilised three two-dimensional and one multimodal datasets, each emphasising specific characteristics relevant to real-world data scenarios:

- The “noisy” dataset (dataset “zelnik2” in [93]) contains randomly generated background noise and was chosen to test the efficiency of the algorithm in situations where noise is present.

- The“Mickey Mouse” dataset was generated by the authors to test the ability of the algorithm to identify objects with distinct shapes.

- The “particles” dataset was generated by the authors to test the algorithm’s ability to identify regions with distinct flow characteristics during particle dispersion.

- The Wine Recognition dataset [94] is a well-established multimodal dataset that enables us to test the robustness of the method under heterogeneous feature spaces, which is essential for applications where the underlying phenomena arise from multiple interacting modes of behaviour.

For the three datasets (i.e., “noisy”, “Mickey Mouse”, Wine Recognition), the optimal number of clusters and optimal configuration were known a priori, whereas for the “particles” dataset, the number of points per cluster and the optimal separation between clusters were not known in advance; nevertheless, its global behaviour conforms to theoretical predictions [95]. The SUN algorithm was utilised to identify optimal clustering configurations and their corresponding centres, and to predict the shapes and positions of clusters. The predicted centres were also used by K-means to estimate cluster shapes and were compared with the SUN-predicted clusters.

All simulations were run on a personal computer with an Intel Core i5 processor and 8 GB RAM. All runs were executed on the CPU using Python (version 3.12.9) with scikit-learn. End-to-end wall-clock times for the SUN pipeline ranged from 6 s to 705 s, depending on the dataset size, the K search range, and the number of RUN-ICON repetitions and EM iterations.

3.1. “Noisy” Dataset

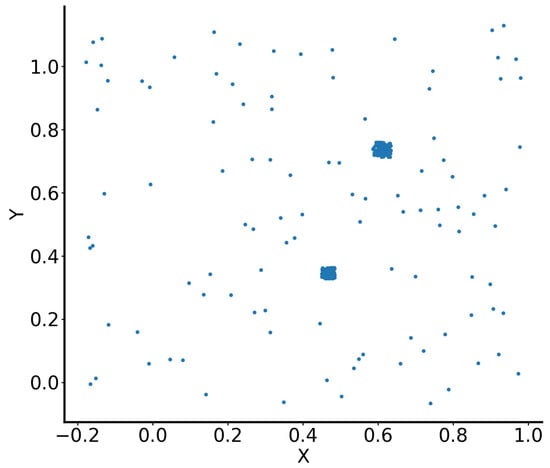

This section presents an analysis of synthetic two-dimensional data consisting of 303 points. The dataset forms two clusters (blobs), with the remaining points scattered and classified as noise. This dataset was created by Zelnik-Manor and Perona [96], who applied self-tuning spectral clustering to segment the data into three clusters: two representing the dense blobs and a third capturing the scattered noise points (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Illustration of the dataset by Zelnik-Manor and Perona [96].

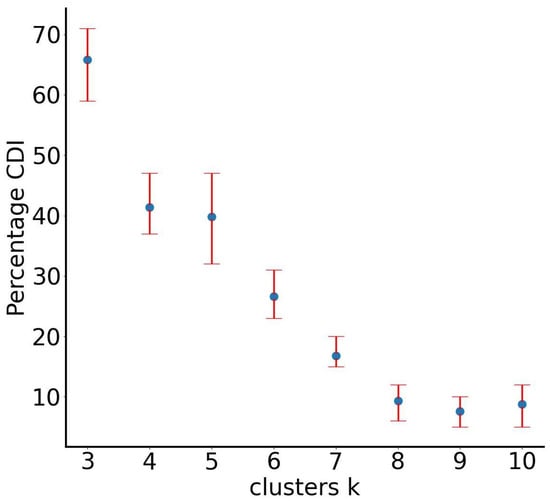

To evaluate the performance of our proposed SUN algorithm, we initially applied the first component, RUN-ICON, to ascertain the optimal number of clusters. The RUN-ICON method identified three clusters as the most suitable partitioning, achieving 66% confidence and 12% uncertainty, which aligns with the ground-truth classification of the dataset. This result is corroborated by the Clustering Dominance Index (CDI) analysis, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

RUN-ICON predictions for the optimal number of clusters for the “noisy” dataset. Different numbers of clusters have been considered, and their CDIs are plotted along with their corresponding uncertainties.

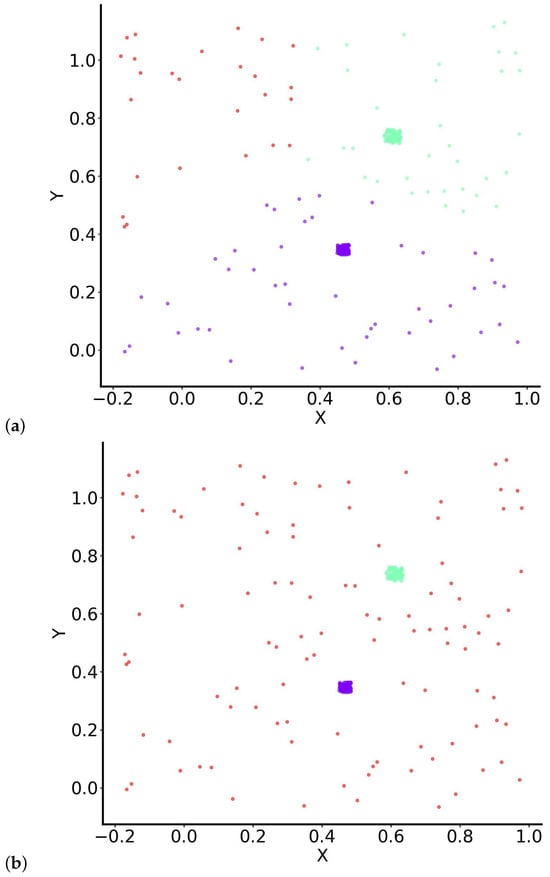

Subsequently, we examined the clustering results using various methods. When only the centroids were utilised and K-means clustering was applied, the noise points adjacent to each blob were grouped with the nearest blob, while the third cluster comprised the remaining noise points situated further from the blob centres (Figure 4a). This outcome indicates that K-means, which relies on centroid-based partitioning, struggles to effectively distinguish between dense clusters and scattered noise when no additional statistical modelling is available.

Figure 4.

Clustering results for the “noisy” dataset using (a) K-means initialised with RUN-ICON centres and (b) SUN (RUN-ICON + GMM). Colours are kept consistent across panels and correspond to the three clusters: Cluster 1 (purple)—first dense blob; Cluster 2 (green)—second dense blob; Cluster 3 (red)—scattered noise points. Panel (a) shows the hard assignments produced by K-means, while panel (b) presents the probabilistic memberships obtained by SUN, yielding soft boundaries and quantifiable uncertainty.

However, when the second component of the SUN algorithm, the Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM), was utilised, the clustering outcome improved significantly. In this instance, the three clusters comprised the two blobs and the noise as a separate category. The GMM component enabled the algorithm to better capture the data’s underlying distribution, resulting in clearer separation between the structured clusters and the noise points. The corresponding clustering results are illustrated in Figure 4b.

RUN-ICON produced initial cluster membership estimates of 148, 129, and 26 samples. These values showed a significant imbalance compared to the true class distribution of 102, 106, and 95 samples. After applying the GMM algorithm with the RUN-ICON labels as initialisation, the cluster sizes were refined to 102, 106, and 95 samples, matching the true cluster counts exactly (see Table 2). This indicated a 66.3% reduction in error after GMM refinement, demonstrating that the probabilistic second stage fully corrected the initial misallocations in this dataset.

Table 2.

True and predicted cluster assignments for RUN-ICON and SUN for the “noisy” dataset.

The stochastic nature of the SUN results in Figure 4b is captured through the GMM membership probabilities. For each point , instead of a deterministic assignment as in (a), we have the following:

Points near cluster centres typically have , while boundary points may have from 0.5 to less than 1.0, reflecting classification uncertainty.

These findings demonstrate the effectiveness of the SUN algorithm in identifying and segmenting structured clusters from noise. While conventional K-means fails to properly distinguish noise points from dense clusters, integrating the GMM into the SUN framework enhances clustering accuracy by leveraging probabilistic modelling. This highlights the advantage of employing such clustering approaches when dealing with complex data distributions.

3.2. “Mickey Mouse” Dataset

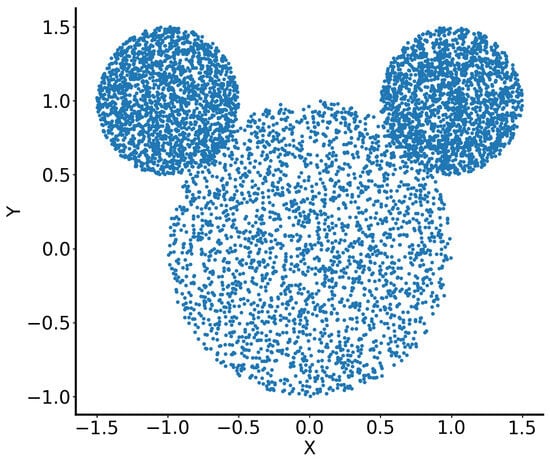

The dataset consists of 6648 points in (x, y) space, which represented the head of Mickey Mouse, i.e, one central circle representing the “face” (3805 points) and two smaller circles, symmetrically attached to the bigger one, representing the “ears” (left “ear”: 1468 points, right “ear”: 1375 points). All data points within the three circles were generated randomly (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Illustration of the “Mickey Mouse” dataset.

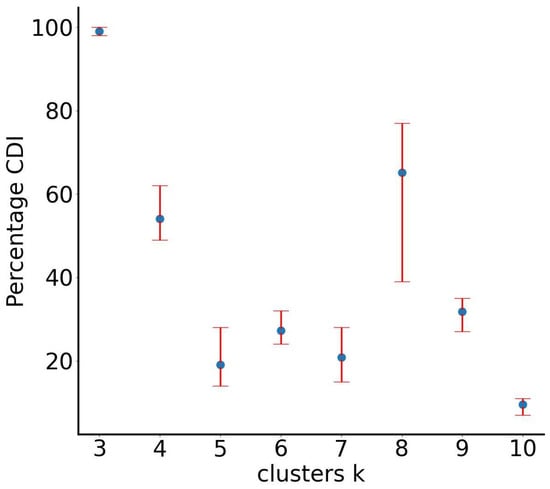

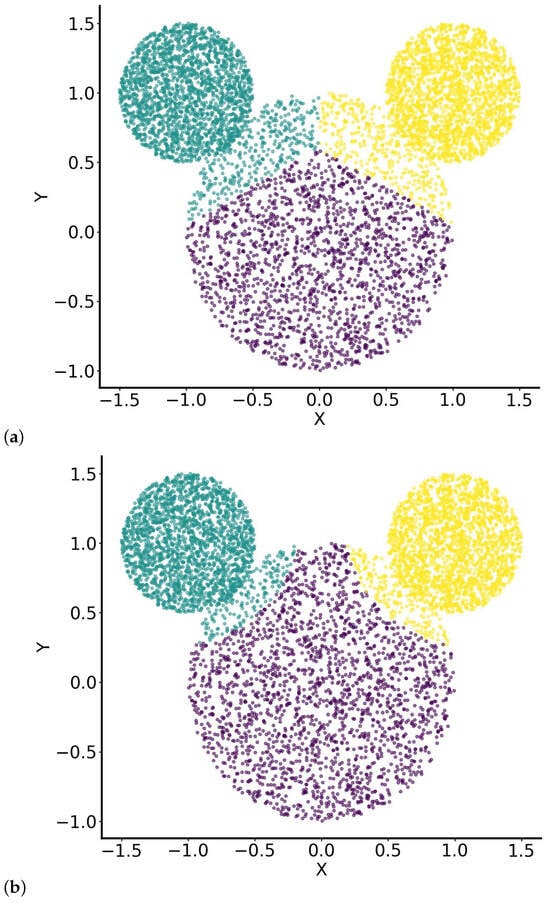

It is anticipated that SUN (through RUN-ICON) will be able to predict three dominant clusters, thereby separating the “face” from the “ears”. Indeed, the algorithm predicted the separation into three clusters with very high confidence (99%) and very low uncertainty (2%), as shown in Figure 6. However, when employing the K-means algorithm with the optimal cluster centres provided by RUN-ICON, a portion of the “head” is erroneously assigned to the “ears” clusters (Figure 7a). This misclassification occurs because K-means depends on Euclidean distance to ascertain cluster membership, and certain regions of the “head” may be closer in distance to the centres of the “ears” clusters than to the “head’s” centre.

Figure 6.

RUN-ICON predictions for the optimal number of clusters for the “Mickey Mouse” dataset. Different numbers of clusters have been considered, and their CDIs are plotted along with their corresponding uncertainties.

Figure 7.

Clustering results for the “Mickey Mouse” dataset using (a) K-means initialised with RUN-ICON centres and (b) SUN (RUN-ICON + GMM). Colours are consistent across panels and correspond to the three anatomical clusters: the “face” (purple), the left “ear” (green), and the right “ear” (yellow). Panel (a) illustrates the hard partitions produced by K-means, which introduce artificial boundaries and misclassifications near the “face”–“ear” intersections. In contrast, panel (b) shows the SUN results, where probabilistic assignments better preserve the natural circular structure and capture the uncertainty in boundary regions.

In contrast, when the GMM component of the SUN algorithm is applied, the majority of the “head” region is correctly assigned to the “head” cluster, with only small areas being misclassified as part of the “ears” (Figure 7b). This improved clustering performance is due to the probabilistic nature of GMMs, which model the data as a mixture of Gaussian distributions, each defined by a mean and a covariance structure. Unlike K-means, which assigns points to the nearest cluster centre based solely on distance, the GMM assigns probabilities to each point belonging to different clusters, considering both the spatial distribution and the shape of the data. In this way, it accounts for the distributional properties of the clusters rather than relying solely on strict proximity. The “head” cluster, which is significantly larger than the “ears” clusters, likely has a broader covariance structure, increasing the likelihood that points in the overlapping region are assigned to the “head” rather than the “ears”. This allows the GMM to better capture the data’s underlying structure while preserving the integrity of natural groupings.

RUN-ICON produced initial cluster membership estimates of 1729, 2462, and 2457 samples for the “head” and left and right “ears”, respectively. These values exhibited noticeable deviations from the true distributions of 3805, 1468, and 1375 samples, particularly underestimating the head region and overestimating the ear regions. After applying the GMM algorithm with the RUN-ICON labels as initialisation, the cluster sizes were refined to 2095, 2279, and 2274 samples, respectively (see Table 3). This corresponds to a 20% improvement in prediction, indicating that the probabilistic second stage improved the points-to-cluster assignments, although the dataset’s complex, non-Gaussian structure limited perfect recovery.

Table 3.

True and predicted cluster assignments for RUN-ICON and SUN for the “Mickey Mouse” dataset.

The stochastic nature of the SUN results in Figure 7b is captured through the GMM membership probabilities. For each point , instead of a deterministic assignment as in (a), we have the following:

Points in the interior of each circular region (face and ears) exhibit high confidence with . However, at the intersection regions where the ears connect to the face, membership probabilities range from 0.50 to less than 1.0, appropriately reflecting the geometric ambiguity where clusters overlap. This probabilistic framework allows SUN to handle the inherent uncertainty in boundary classification that deterministic methods cannot capture.

3.3. “Particles” Dataset

The dataset comprises 146,400 particles simulated using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to model particle dispersion from a coughing event in an enclosed room [97]. This setup reflects realistic turbulent flow conditions, relevant to understanding airborne disease transmission [98,99,100]. Figure 8 schematically illustrates the cough, showing particles expelled mainly along a straight trajectory, with some lateral spread.

Figure 8.

Visualisation of a coughing person and the resultant spread of particles in multiple directions. The image was generated through Microsoft Bing Image Creator for illustration purposes [101].

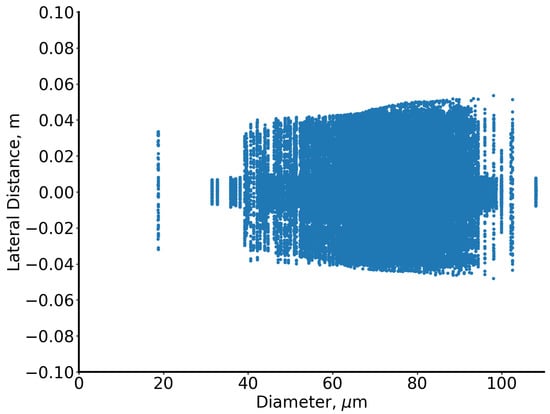

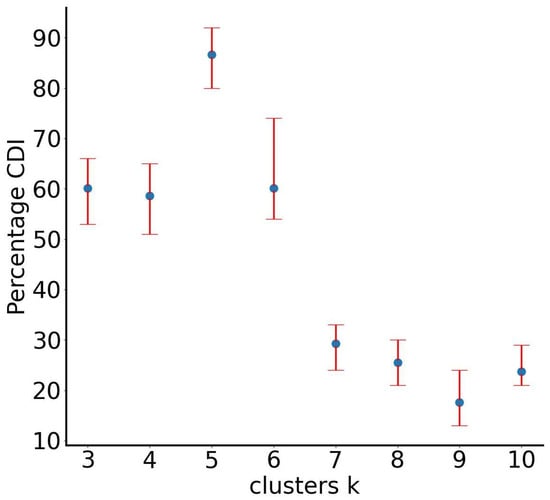

Particle diameters range from 19 to 110 µm, and analysis focuses on the early dispersion phase (0.12 s after cough onset). Figure 9 depicts lateral dispersion: the x-axis represents particle diameter, and the y-axis the lateral distance from the mouth (0). The RUN-ICON algorithm within the SUN framework predicts optimal clustering into five groups with 87% confidence and 12% uncertainty (Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Illustration of the “particles” dataset.

Figure 10.

RUN-ICON predictions for the optimal number of clusters for the “particles” dataset. Different numbers of clusters have been considered, and their CDIs are plotted along with their corresponding uncertainties.

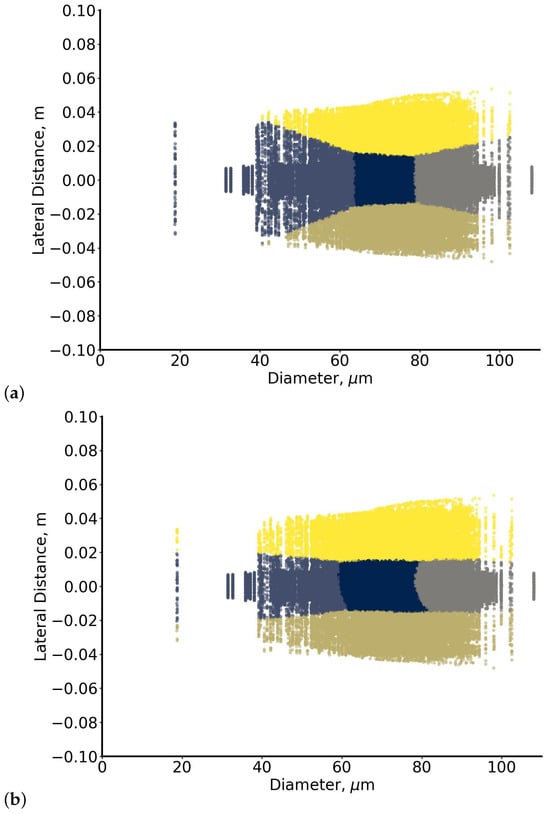

Predicted clusters show that particles near the high-velocity core are separated from those displaced upward or downward by inertial effects, forming three clusters along the main streamline and two above and below it [102]. When K-means is used, small particles are overaggregated across lateral sides (Figure 11a). In contrast, the GMM approach better redistributes particles around the predicted centres, capturing flow-induced segregation and providing a clearer distinction between particles near the core and those displaced laterally consistent with inertial effects and the spatial velocity gradient in the flow [95]. The stochastic nature of the SUN results in Figure 11b is captured through the GMM membership probabilities. For each point , instead of a deterministic assignment as in (a), we have the following:

Figure 11.

Clustering of the “particles” dataset using (a) K-means initialised with RUN-ICON centres and (b) SUN (RUN-ICON + GMM). Colours are kept consistent across panels and correspond to the five flow-based clusters: three along the main trajectory (separated by particle size) and two representing upward and downward lateral displacement due to inertial effects. Panel (a) shows the rigid partitions produced by K-means, while panel (b) demonstrates how SUN’s probabilistic assignments better capture the continuous transition between flow regimes and highlight uncertainty near boundary regions.

For particles clearly within a single flow regime, typically. However, particles at the transitions between flow regions exhibit lower certainties with from 0.3 to less than 1.0, reflecting the physical reality that particles near regime boundaries experience competing influences. This soft assignment capability is particularly valuable for understanding the continuous nature of particle dispersion, where hard boundaries imposed by deterministic clustering may not accurately represent the underlying physics.

3.4. Multimodal Wine Recognition Dataset

To evaluate the performance of the SUN algorithm on multimodal and chemically complex data, we applied it to the well-established Wine Recognition dataset [94]. This dataset originates from chemical analyses of wines produced in the same region of Italy, but derived from three distinct cultivars. Each sample is described by thirteen continuous physicochemical measurements, including alcohol content, phenolic compositions, colour intensity, and proline concentration. A total of 178 instances are available, grouped into three classes comprising 59, 48, and 71 samples, respectively. The dataset has been widely used in benchmark studies of chemometric and statistical learning methods, in which RDA, QDA, LDA, and nearest-neighbour classifiers have been assessed. Its well-behaved class structure and moderate dimensionality make it an appropriate and historically validated dataset for testing new algorithms in unsupervised learning and classification [103,104].

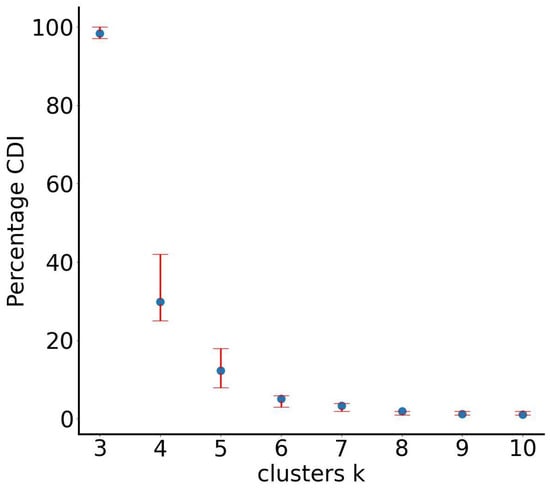

The first stage of the SUN algorithm, RUN-ICON, was applied to determine the correct number of clusters and to generate the optimal clustering assignment. The CDI results for the Wine Recognition dataset revealed a strong, unambiguous preference for three clusters. The three-cluster solution achieved a CDI of 98% with an uncertainty of only 3%, whereas all alternative cluster numbers yielded CDI scores below 30%. This finding aligns perfectly with the known class structure of the dataset and is further illustrated in Figure 12, where the three-cluster configuration emerges as overwhelmingly dominant relative to alternatives. RUN-ICON also produced initial cluster membership estimates of 60, 55, and 63 samples for Clusters 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

Figure 12.

RUN-ICON predictions for the optimal number of clusters for the Wine Recognition dataset. Different numbers of clusters have been considered, and their CDIs are plotted along with their corresponding uncertainties.

To further refine the distribution of samples across clusters, the GMM algorithm was applied, using the RUN-ICON output as initialisation. After the application of the GMM, the cluster sizes were updated to 63, 50, and 65 samples. To evaluate the quality of the two stages, we compared the predicted cluster sizes with the true class counts. RUN-ICON alone yielded an average absolute relative deviation of 9.18% across the three clusters. After GMM refinement, this error decreased to 6.46%, indicating an improvement of approximately 29.6%. Thus, while RUN-ICON provided an accurate initial estimate of the number of clusters and a reasonable first allocation of points, the addition of the GMM further improved the assignment consistency by redistributing points more faithfully according to the true underlying class distribution.

The overall results are summarised in Table 4, which presents the true cluster sizes alongside those predicted by RUN-ICON alone and those obtained after the full SUN procedure. These findings confirm that the SUN algorithm not only identifies the correct cluster count with high confidence but also benefits from the GMM refinement step, which enhances the internal consistency and accuracy of the final cluster assignments. Given the multimodal composition of the wine chemical attributes and the intrinsic variability among cultivars, this experiment demonstrates that SUN provides a reliable and effective methodology for unsupervised structure identification in real-world high-dimensional datasets.

Table 4.

True and predicted cluster assignments for RUN-ICON and SUN for the Wine Recognition dataset.

The stochastic nature of the SUN results is captured through the GMM membership probabilities. For each point , instead of a deterministic assignment, we have the following:

Points near cluster centres have , while boundary points may have ranging from 0.5 to less than 1.0, reflecting classification uncertainty.

3.5. Comparisons with Other Clustering Methods/Schemes

The results presented for all four cases demonstrate the strengths of the proposed algorithm. While comprehensive benchmarking against alternative clustering schemes (e.g., K-means variants, stand-alone GMM) using standard external validity metrics (Adjusted Rand Index, NMI, Silhouette) can be informative, it is not strictly necessary here because the RUN-ICON methodology has already been systematically evaluated and reported by Christakis and Drikakis [48,74]. In two recent studies the authors introduced RUN-ICON, demonstrated its ability to identify the optimal number of clusters by using the Clustering Dominance Index–CDI and an explicit uncertainty score across repeated K-means++ runs, and validated the method on multiple synthetic and real datasets (including multimodal and particle-dispersion examples), reporting high CDI values, low uncertainty, and practical runtimes for correct cluster recovery. Notably, Silhouette Coefficient (SC) benchmarking has already been reported for related RUN-ICON applications in [74], where SC was used to compare baseline clustering methods, further supporting the use of standard validity metrics in prior evaluations. Furthermore, where probabilistic refinement was appropriate, they showed that RUN-ICON’s dominant centres can be used to initialise a GMM and that EM-based GMM redistribution produces refined, consistent cluster assignments—i.e., RUN-ICON both robustly locates stable centres and integrates effectively with model-based clustering refinements [76]. Taken together, these results (high CDI/low uncertainty on benchmark sets, consistent behaviour across repetitions, and demonstrated integration with GMM refinement) provide direct evidence that RUN-ICON produces reliable clusterings in the kinds of datasets studied here; we therefore adopt RUN-ICON as our primary clustering/initialisation strategy and focus this work on the SUN uncertainty-aware contributions.

3.6. Potential Applications

Beyond particle dispersion analysis and wine recognition, we believe that the SUN framework has broad applicability across diverse domains, such as the following:

- Medical Imaging: Tumour segmentation in MRI/CT scans with uncertainty quantification for surgical planning.

- Financial Markets: Anomaly detection in trading patterns with confidence intervals for risk assessment.

- Climate Science: Classification of weather patterns with probabilistic boundaries for improved forecasting.

- Manufacturing: Quality control clustering with confidence metrics for defect detection.

- Social Networks: Community detection with probabilistic boundaries for influence analysis.

- Genomics: Cell type identification in single-cell RNA sequencing with uncertainty estimates.

- Cybersecurity: Network traffic clustering for intrusion detection with false positive probability estimates.

4. Conclusions

In this work, we have presented a comprehensive study of the “Stochastic UNsupervised learning” (SUN) methodology, which integrates the “Reduce UNcertainty and Increase CONfidence” (RUN-ICON) algorithm for initial cluster identification with Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs) for refined probabilistic clustering. Our approach has been specifically designed to handle the challenges posed by multimodal and noisy datasets, a scenario commonly encountered in natural processes and real-world applications. The results obtained from extensive experiments on benchmark datasets, including the well-established Wine Recognition dataset, demonstrate that our methodology consistently identifies the true underlying cluster structure with a high degree of accuracy, overcoming limitations observed in traditional clustering approaches.

The primary contribution of this study lies in the synergistic combination of RUN-ICON and the GMM. RUN-ICON efficiently detects initial cluster centroids, providing a robust starting point that significantly reduces the risk of convergence to suboptimal local minima in the subsequent GMM phase. By leveraging these high-quality initial estimates, the GMM is able to iteratively refine the cluster assignments, ensuring that the resulting clusters closely align with the actual data distribution. This two-step procedure not only improves the accuracy of cluster identification but also enhances the interpretability of the results, allowing for more meaningful insights into the underlying structure of complex datasets.

A particularly noteworthy aspect of the SUN methodology is its ability to handle datasets characterised by uneven or imbalanced cluster sizes. Traditional clustering algorithms, such as K-means or a standard GMM with random initialisation, often struggle in these situations, leading to overaggregation or misclassification of minority clusters. Our experiments demonstrate that by initialising the GMM with RUN-ICON centroids, the SUN approach successfully mitigates these biases, producing cluster distributions that match the true class proportions even in challenging scenarios. This property is of critical importance in applications where the accurate identification of small or subtle clusters can significantly impact downstream analysis or decision-making processes.

Furthermore, the SUN methodology exhibits strong performance in the context of multimodal datasets. Real-world data frequently contain complex distributions that cannot be adequately captured by single-mode assumptions, and our results show that the combination of RUN-ICON and the GMM is particularly effective in uncovering these structures. By first identifying approximate cluster centres and then allowing the GMM to model the continuous probabilistic boundaries, the SUN approach captures the intrinsic variability within each cluster, reflecting the true multimodal nature of the data. This capability highlights the method’s generalisability and its potential for application across diverse domains, ranging from chemical analysis to biomedical datasets, where the recognition of subtle multimodal patterns is essential.

In addition to accuracy improvements, our methodology provides practical advantages in terms of computational efficiency and robustness. RUN-ICON’s deterministic nature ensures consistent initialisation, reducing the variability and unpredictability often observed in stochastic clustering methods. This determinism, combined with the probabilistic refinement offered by the GMM, creates a balanced framework that is both reliable and scalable. Consequently, the SUN methodology can be applied to large datasets without significant computational overhead, while maintaining robustness against noise and outliers. These properties render the method particularly suitable for high-dimensional data scenarios, where traditional clustering approaches often fail to provide reliable results.

Another important contribution of this study is the benchmarking and comparison of SUN against established methods. By evaluating cluster quality using metrics such as cluster size distribution alignment, we have provided strong empirical evidence of the superiority of our approach in both balanced and imbalanced datasets. The consistent performance across multiple test cases reinforces the utility of the methodology and validates its design principles. Moreover, the flexibility of the SUN framework allows for the incorporation of alternative clustering algorithms in place of the GMM, potentially extending its applicability to a wider range of data characteristics and problem domains.

From a methodological standpoint, the SUN approach bridges the gap between deterministic and probabilistic clustering paradigms. The initial deterministic clustering ensures a strong foundation by capturing the primary modes of the data, while the subsequent probabilistic modelling accounts for finer nuances and overlapping structures. This dual perspective not only improves clustering fidelity but also provides richer information about the uncertainty and confidence associated with each data point’s cluster assignment. Such information is invaluable in applications where risk assessment or probabilistic reasoning is required, including predictive modelling, quality control, and exploratory data analysis.

Looking forward, the results of this study suggest several promising avenues for further research and development. Integrating feature selection or dimensionality reduction techniques within the SUN framework could enhance its performance on extremely high-dimensional datasets, while exploring adaptive or data-driven mechanisms for determining the optimal number of clusters could reduce reliance on prior knowledge and increase the method’s autonomy. Extending SUN to dynamic or streaming datasets presents an exciting opportunity, allowing the algorithm to continuously update cluster structures in real time and maintain high accuracy in evolving data environments. Investigating scalability on high-performance computing architectures could facilitate its application to large-scale simulations, and hybrid models that incorporate graph-based clustering or deep feature extraction could broaden its applicability across diverse scientific and industrial domains. Further refinement of the probabilistic modelling components may improve interpretability, particularly in scenarios requiring careful assessment of complex uncertainty structures for decision-making. By pursuing these directions, the SUN framework has the potential to advance robust, uncertainty-aware unsupervised learning methodologies, ensuring that AI-driven clustering remains reliable, scalable, and adaptable to the growing demands of real-world data analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.C. and D.D.; methodology, N.C. and D.D.; formal analysis, N.C. and D.D.; investigation, N.C. and D.D.; software, N.C.; funding acquisition, D.D.; writing, N.C. and D.D.; contribution to the discussion, N.C. and D.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is supported by the European Union’s Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Actions programme under grant agreement No. 101069937, project name: HS4U (HEALTHY SHIP 4U). Views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Climate, Infrastructure, and Environment Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The non-public data supporting this study’s findings can be found at https://github.com/nchrkis/SUN_datasets and the Python codes for the SUN algorithm can be found at https://github.com/nchrkis/SUN_codes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. The GMM Framework

Suppose we have a dataset of N data points, , that has already been separated into K clusters. For each cluster, a mean (a matrix) is defined, each element of which is given by

where

- .

- is the j-th element of matrix ().

- is the number of points in cluster k.

- is the j-th coordinate of a point that belongs to cluster k.

We also define for every cluster k an covariance matrix :

where

- is the matrix of all cluster-k points minus the corresponding to each row component.

Then, we may define the Gaussian distribution for points belonging to cluster k as

where

- and are the determinant and inverse of the covariance matrix, respectively.

- is an vector, corresponding to the difference between point and its respective component of .

We may also define a weight for each cluster, which indicates the proportion of points belonging to that cluster:

It becomes obvious . Then, based on the GMM, the probability of a point from the dataset belonging to cluster k is given by

For a complete derivation of this formula, please see [90].

Appendix B. Pseudocode for the SUN Algorithm

| Algorithm A1 SUN: Stability-driven clustering with probabilistic assignments |

|

References

- Jin, X.; Han, J. K-Means Clustering. In Encyclopedia of Machine Learning; Sammut, C., Webb, G.I., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 563–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloghani, M.; Al-Jumeily, D.; Mustafina, J.; Hussain, A.; Aljaaf, A.J. A Systematic Review on Supervised and Unsupervised Machine Learning Algorithms for Data Science. In Supervised and Unsupervised Learning for Data Science; Berry, M.W., Mohamed, A., Yap, B.W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glielmo, A.; Husic, B.E.; Rodriguez, A.; Clementi, C.; Noé, F.; Laio, A. Unsupervised Learning Methods for Molecular Simulation Data. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 9722–9758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuer, M.J. Unsupervised Learning. In Machine Learning for Engineers: Introduction to Physics-Informed, Explainable Learning Methods for AI in Engineering Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 141–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, J.; Davis, J. Learning from positive and unlabeled data: A survey. Mach. Learn. 2020, 109, 719–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Cheng, F.; Zhang, X.; Cui, C.; Cai, W. A novel semi-supervised data-driven method for chiller fault diagnosis with unlabeled data. Appl. Energy 2021, 285, 116459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wang, L.; Ranjan, R.; He, G.; Zhao, L. A Survey on Active Deep Learning: From Model Driven to Data Driven. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshi, R.; Ranjan, R.; Kumar Vishwakarma, A.; Yang, T.; Singh Rathore, R. Exploring the Frontiers of Unsupervised Learning Techniques for Diagnosis of Cardiovascular Disorder: A Systematic Review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 139253–139272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulou, S. A review of unsupervised learning in astronomy. Astron. Comput. 2024, 48, 100851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T. Credit Risk Assessment Using a Combined Approach of Supervised and Unsupervised Learning. J. Comput. Methods Eng. Appl. 2024, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tautan, A.M.; Andrei, A.G.; Smeralda, C.L.; Vatti, G.; Rossi, S.; Ionescu, B. Unsupervised learning from EEG data for epilepsy: A systematic literature review. Artif. Intell. Med. 2025, 162, 103095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansal, T.; Bahuguna, S.; Singh, V.; Choudhury, T. Customer Segmentation using K-means Clustering. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Computational Techniques, Electronics and Mechanical Systems (CTEMS), Belgaum, India, 21–22 December 2018; pp. 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, A.; Khan, L.; Hussain, M.Z.; Hasan, M.Z.; Mustafa, M.; Khalid, A.; Awan, R.; Ashraf, F.; Khan, Z.A.; Javaid, A. Customer Segmentation Using Hierarchical Clustering. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 9th International Conference for Convergence in Technology (I2CT), Pune, India, 5–7 August 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriarca, R.; Simone, F.; Di Gravio, G. Supporting weather forecasting performance management at aerodromes through anomaly detection and hierarchical clustering. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 213, 119210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.; Kaur, G.; Saxena, V. A K-Means clustering and SVM based hybrid concept drift detection technique for network anomaly detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 193, 116510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karczmarek, P.; Kiersztyn, A.; Pedrycz, W.; Al, E. K-Means-based isolation forest. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 195, 105659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, P.; Garg, N.K.; Kumar, M. Content-based image retrieval system using ORB and SIFT features. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 32, 2725–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Ding, S.; Jia, H. Study on density peaks clustering based on k-nearest neighbors and principal component analysis. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2016, 99, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilashi, M.; Ibrahim, O.; Bagherifard, K. A recommender system based on collaborative filtering using ontology and dimensionality reduction techniques. Expert Syst. Appl. 2018, 92, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, Z.; Long, W.; Chen, Z. Multi-Dimensional Manifolds Consistency Regularization for semi-supervised remote sensing semantic segmentation. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 299, 112032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, L.; Liang, C.; Liu, H.; Li, A. Unsupervised dimension-contribution-aware embeddings transformation for anomaly detection. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 262, 110209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilal, W.; Gadsden, S.A.; Yawney, J. Financial Fraud: A Review of Anomaly Detection Techniques and Recent Advances. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 193, 116429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, K.K.; Singh, B.M.; Dixit, A. A review of supervised and unsupervised machine learning techniques for suspicious behavior recognition in intelligent surveillance system. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 2022, 14, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiser, A.; Özcan, B.; van Stein, B.; Bäck, T. Evaluation of deep unsupervised anomaly detection methods with a data-centric approach for on-line inspection. Comput. Ind. 2023, 146, 103852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. An introduction to variational autoencoders. Found. Trends® Mach. Learn. 2019, 12, 307–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Du, Y.; Lin, S.; Cui, P.; Shen, Y.; Yang, Y. adVAE: A self-adversarial variational autoencoder with Gaussian anomaly prior knowledge for anomaly detection. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 190, 105187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yang, S.; Fujita, H.; Chen, D.; Wen, C. Deep learning fault diagnosis method based on global optimization GAN for unbalanced data. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 187, 104837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbey, M.; Dalmaz, O.; Dar, S.U.H.; Bedel, H.A.; Ozturk, Ş.; Güngör, A.; Çukur, T. Unsupervised Medical Image Translation With Adversarial Diffusion Models. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2023, 42, 3524–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadebec, C.; Vincent, L.; Allassonniere, S. Pythae: Unifying Generative Autoencoders in Python—A Benchmarking Use Case. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Koyejo, S., Mohamed, S., Agarwal, A., Belgrave, D., Cho, K., Oh, A., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: San Jose, CA, USA, 2022; Volume 35, pp. 21575–21589. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.K.; Goswami, S.; Chakrabarti, A.; Chakraborty, B. A new hybrid feature selection approach using feature association map for supervised and unsupervised classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 88, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B. E-commerce Customer Segmentation via Unsupervised Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computing and Data Science, Stanford, CA, USA, 28–30 January 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, S.; Ali, A.; Anam, S.; Ahmed, M.M. An unsupervised machine learning algorithms: Comprehensive review. Int. J. Comput. Digit. Syst. 2023, 13, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, J.; Chen, T.; Zhang, J.; Cao, Q.; Sun, Z.; Luo, H.; Tao, D. A Survey on Self-Supervised Learning: Algorithms, Applications, and Future Trends. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 9052–9071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Kornblith, S.; Swersky, K.; Norouzi, M.; Hinton, G.E. Big Self-Supervised Models are Strong Semi-Supervised Learners. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Larochelle, H., Ranzato, M., Hadsell, R., Balcan, M., Lin, H., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: San Jose, CA, USA, 2020; Volume 33, pp. 22243–22255. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, R.; Shen, C.; Kong, T.; Li, L. Dense Contrastive Learning for Self-Supervised Visual Pre-Training. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; p. 11, Oral paper. [Google Scholar]

- Grill, J.B.; Strub, F.; Altché, F.; Tallec, C.; Richemond, P.; Buchatskaya, E.; Doersch, C.; Avila Pires, B.; Guo, Z.; Gheshlaghi Azar, M.; et al. Bootstrap Your Own Latent—A New Approach to Self-Supervised Learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Larochelle, H., Ranzato, M., Hadsell, R., Balcan, M., Lin, H., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: San Jose, CA, USA, 2020; Volume 33, pp. 21271–21284. [Google Scholar]

- Koroteev, M.V. BERT: A review of applications in natural language processing and understanding. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.11943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Bishop, J.A.; Tiwari, P.; Ananiadou, S. Pre-trained language models with domain knowledge for biomedical extractive summarization. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 252, 109460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Li, K.; Zhang, G.; Lu, J. A deeper graph neural network for recommender systems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2019, 185, 105020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, S.; Chen, F.; Long, G.; Zhang, C.; Yu, P.S. A Comprehensive Survey on Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 32, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Q.; Liu, N.; Huang, X.; Choi, S.H.; Li, L.; Chen, R.; Hu, X. S2GAE: Self-Supervised Graph Autoencoders are Generalizable Learners with Graph Masking. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Singapore, 27 February–3 March 2023; pp. 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Lin, Y.; Peng, Q.; Zhao, J.; Pei, Z.; Sun, Y. Learning graph deep autoencoder for anomaly detection in multi-attributed networks. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 260, 110084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, V.S.; Provost, F.; Ipeirotis, P.G. Get another label? Improving data quality and data mining using multiple, noisy labelers. In Proceedings of the 14th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24–27August 2008; pp. 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldoseri, A.; Al-Khalifa, K.N.; Hamouda, A.M. Re-Thinking Data Strategy and Integration for Artificial Intelligence: Concepts, Opportunities, and Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Zhu, X.; Chen, K.; Jia, K.; Chen, C.L.P. Towards Uncovering the Intrinsic Data Structures for Unsupervised Domain Adaptation Using Structurally Regularized Deep Clustering. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 44, 6517–6533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Biljecki, F. Unsupervised machine learning in urban studies: A systematic review of applications. Cities 2022, 129, 103925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakis, N.; Drikakis, D. Reducing Uncertainty and Increasing Confidence in Unsupervised Learning. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Gupta, A. Dealing with Noise Problem in Machine Learning Data-sets: A Systematic Review. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 161, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Hao, H.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Shi, J.; Yu, J.; Cui, X.; Li, J.; Zhou, S.; Yu, B. Optimized adaptive Savitzky-Golay filtering algorithm based on deep learning network for absorption spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 263, 120187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kascenas, A.; Pugeault, N.; O’Neil, A.Q. Denoising Autoencoders for Unsupervised Anomaly Detection in Brain MRI. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Medical Imaging with Deep Learning; Konukoglu, E., Menze, B., Venkataraman, A., Baumgartner, C., Dou, Q., Albarqouni, S., Eds.; PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; Volume 172, pp. 653–664. [Google Scholar]

- Mansour, Y.; Heckel, R. Zero-Shot Noise2Noise: Efficient Image Denoising Without Any Data. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 14018–14027. [Google Scholar]

- Krull, A.; Buchholz, T.O.; Jug, F. Noise2Void - Learning Denoising From Single Noisy Images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, Y.; Chen, M.; Pang, T.; Ji, H. Self2Self With Dropout: Learning Self-Supervised Denoising From Single Image. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, A.; Gal, Y. What Uncertainties Do We Need in Bayesian Deep Learning for Computer Vision? In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Guyon, I., Luxburg, U.V., Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Fergus, R., Vishwanathan, S., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: San Jose, CA, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Sucar, L.E. Probabilistic Graphical Models; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, A.G.; Izmailov, P.; Hoffman, M.D.; Gal, Y.; Li, Y.; Pradier, M.F.; Vikram, S.; Foong, A.; Lotfi, S.; Farquhar, S. Evaluating Approximate Inference in Bayesian Deep Learning. In NeurIPS 2021 Competitions and Demonstrations Track; Kiela, D., Ciccone, M., Caputo, B., Eds.; PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; Volume 176, pp. 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Modern Monte Carlo methods for efficient uncertainty quantification and propagation: A survey. WIREs Comput. Stat. 2021, 13, e1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdar, M.; Pourpanah, F.; Hussain, S.; Rezazadegan, D.; Liu, L.; Ghavamzadeh, M.; Fieguth, P.; Cao, X.; Khosravi, A.; Acharya, U.R.; et al. A review of uncertainty quantification in deep learning: Techniques, applications and challenges. Inf. Fusion 2021, 76, 243–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomani, C.; Cremers, D.; Buettner, F. Parameterized Temperature Scaling for Boosting the Expressive Power in Post-Hoc Uncertainty Calibration. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2022; Avidan, S., Brostow, G., Cissé, M., Farinella, G.M., Hassner, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sur, P. Optimal and Provable Calibration in High-Dimensional Binary Classification: Angular Calibration and Platt Scaling. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.15131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.B.; Jiang, P.T.; Hou, Q.; Wei, Y.; Han, Q.; Li, Z.; Cheng, M.M. Delving Deep Into Label Smoothing. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 5984–5996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, J.; Li, Q.; Zhu, C.; Li, J. A hierarchical naive abas network classifier embedded GMM for textural image. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2012, 14, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Tan, H.; Tang, B.; Zhou, H. Variational Deep Embedding: An Unsupervised and Generative Approach to Clustering. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1611.05148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Gao, L.; Liu, X.; Yin, J. Improved deep embedded clustering with local structure preservation. In Proceedings of the 26th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Melbourne, Australia, 19–25 August 2017; Volume 17, pp. 1753–1759. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Ding, C.; Tan, W.; Gong, M.; Jia, K.; Tao, D. Uncertainty-Aware Clustering for Unsupervised Domain Adaptive Object Re-Identification. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 25, 2624–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontolati, K.; Loukrezis, D.; Giovanis, D.G.; Vandanapu, L.; Shields, M.D. A survey of unsupervised learning methods for high-dimensional uncertainty quantification in black-box-type problems. J. Comput. Phys. 2022, 464, 111313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthik, E.N.; Cheriet, F.; Laporte, C. Uncertainty Estimation in Unsupervised MR-CT Synthesis of Scoliotic Spines. IEEE Open J. Eng. Med. Biol. 2024, 5, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dbouk, T.; Drikakis, D. On coughing and airborne droplet transmission to humans. Phys. Fluids 2020, 32, 053310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, Z.; Yousefi Rezaii, T.; Sheykhivand, S.; Farzamnia, A.; Razavi, S. Deep convolutional neural network for classification of sleep stages from single-channel EEG signals. J. Neurosci. Methods 2019, 324, 108312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, G. Feature Alignment by Uncertainty and Self-Training for Source-Free Unsupervised Domain Adaptation. Neural Netw. 2023, 161, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, G. Unsupervised domain adaptation based on the predictive uncertainty of models. Neurocomputing 2023, 520, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltouny, K.; Gomaa, M.; Liang, X. Unsupervised learning methods for data-driven vibration-based structural health monitoring: A review. Sensors 2023, 23, 3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christakis, N.; Drikakis, D. Unsupervised Learning of Particles Dispersion. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakis, N.; Drikakis, D.; Ritos, K.; Kokkinakis, I.W. Unsupervised machine learning of virus dispersion indoors. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 013320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakis, N.; Drikakis, D. On particle dispersion statistics using unsupervised learning and Gaussian mixture models. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 093317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakis, N.; Drikakis, D.; Kokkinakis, I.W. Advancing understanding of indoor conditions using artificial intelligence methods. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 015160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panić, B.; Klemenc, J.; Nagode, M. Gaussian Mixture Model Based Classification Revisited: Application to the Bearing Fault Classification. J. Mech. Eng. Vestn. 2020, 66, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebarani, P.E.; Umadevi, N.; Dang, H.; Pomplun, M. A novel hybrid K-means and GMM machine learning model for breast cancer detection. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 146153–146162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajihosseinlou, M.; Maghsoudi, A.; Ghezelbash, R. A comprehensive evaluation of OPTICS, GMM and K-means clustering methodologies for geochemical anomaly detection connected with sample catchment basins. Geochemistry 2024, 84, 126094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo-Gabín, A.; Tlales, K.; Valero, E.; Ferrer, E.; Rubio, G. An unsupervised machine-learning-based shock sensor: Application to high-order supersonic flow solvers. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 270, 126352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.; Feng, F.; Ottinger, J.; Foster, D.; West, M.; Kepler, T.B. Statistical mixture modeling for cell subtype identification in flow cytometry. Cytom. Part J. Int. Soc. Anal. Cytol. 2008, 73, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khansari-Zadeh, S.M.; Billard, A. Learning stable nonlinear dynamical systems with gaussian mixture models. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2011, 27, 943–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiest, J.; Höffken, M.; Kreßel, U.; Dietmayer, K. Probabilistic trajectory prediction with Gaussian mixture models. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium, Alcala de Henares, Spain, 3–7 June 2012; pp. 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Varolgüneş, Y.B.; Bereau, T.; Rudzinski, J.F. Interpretable embeddings from molecular simulations using Gaussian mixture variational autoencoders. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2020, 1, 015012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitaab, M.; Hashemi, S. Hybrid intrusion detection: Combining decision tree and gaussian mixture model. In Proceedings of the 2017 14th International ISC (Iranian Society of Cryptology) Conference on Information Security and Cryptology (ISCISC), Shiraz, Iran, 6–7 September 2017; pp. 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, H.; Wang, H.; Scotney, B.; Liu, J. A novel Gaussian mixture model for classification. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics (SMC), Bari, Italy, 6–9 October 2019; pp. 3298–3303. [Google Scholar]

- Scrucca, L.; Fop, M.; Murphy, T.B.; Raftery, A.E. mclust 5: Clustering, classification and density estimation using Gaussian finite mixture models. R J. 2016, 8, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikotun, A.M.; Ezugwu, A.E.; Abualigah, L.; Abuhaija, B.; Heming, J. K-means clustering algorithms: A comprehensive review, variants analysis, and advances in the era of big data. Inf. Sci. 2023, 622, 178–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, D.A. A Gaussian Mixture Modeling Approach to Text-Independent Speaker Identification; Georgia Institute of Technology: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Morris, J.; Martin, E. Probability density estimation via an infinite Gaussian mixture model: Application to statistical process monitoring. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. Appl. Stat. 2006, 55, 699–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, A.; Özkan, H.C.; Maier, A.; Riess, C. Fast and Efficient Limited Data Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Image Classification via GMM-Based Synthetic Samples. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2019, 12, 2107–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton Tomas. Clustering Benhmarks. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/deric/clustering-benchmark (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Aeberhard, S. Wine Data Set. UCI Machine Learning Repository. 1991. Available online: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/109/wine (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Amini, H.; Lee, W.; Di Carlo, D. Inertial microfluidic physics. Lab Chip 2014, 14, 2739–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelnik-manor, L.; Perona, P. Self-Tuning Spectral Clustering. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Saul, L., Weiss, Y., Bottou, L., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Ritos, K.; Drikakis, D.; Kokkinakis, I.W. Virus spreading in cruiser cabin. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 103329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatem, A.J. Mapping population and pathogen movements. Int. Health 2014, 6, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.L.; Turnham, P.; Griffin, J.R.; Clarke, C.C. Consideration of the aerosol transmission for COVID-19 and public health. Risk Anal. 2020, 40, 902–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, M.C. Aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2: Physical principles and implications. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 590041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microsoft. Bing Image Creator. 2025. Available online: https://www.bing.com/create (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Loth, E. Numerical approaches for motion of dispersed particles, droplets and bubbles. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2000, 26, 161–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forma, M.; Leardi, R.; Armanino, C.; Lanteri, S.; Conti, P.; Princi, P. PARVUS—An Extendible Package for Data Exploration, Classification and Correlation; Elsevier Scientific Software: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Aeberhard, S.; Coomans, D.; Vel, O.D. Improvements to the classification performance of RDA. J. Chemom. 1993, 7, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).