Abstract

To address the challenge of bird species detection on transmission lines, this paper proposes a detection method based on dual data enhancement and an improved YOLOv8s model. The method aims to improve the accuracy of identifying small- and medium-sized targets in bird detection scenes on transmission lines, while also accounting for the impact of changing weather conditions. To address these issues, a dual data enhancement strategy is introduced. The model’s generalization ability in outdoor environments is enhanced by simulating various weather conditions, including sunny, cloudy, and foggy days, as well as halo effects. Additionally, an improved Mosaic augmentation technique is proposed, which incorporates target density calculation and adaptive scale stitching. Within the improved YOLOv8s architecture, the CBAM attention mechanism is embedded in the Backbone network, and BiFPN replaces the original Neck module to facilitate bidirectional feature extraction and fusion. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves high detection accuracy for all bird species, with an average precision rate of 94.2%, a recall rate of 89.7%, and an mAP@50 of 94.2%. The model also maintains high inference speed, demonstrating potential for real-time detection requirements. Ablation and comparative experiments validate the effectiveness of the proposed model, confirming its suitability for edge deployment and its potential as an effective solution for bird species detection and identification on transmission lines.

1. Introduction

Power transmission lines and tower equipment span across cities, rivers, forests, and various other regions worldwide, which often serve as perching and nesting sites for birds. Bird activities such as nesting, roosting, and defecation can lead to power outages, short circuits, and other faults, severely affecting the safe and stable operation of power systems. In recent years, bird-related incidents have become more prominent, with damage to transmission lines caused by birds emerging as a leading cause of power system failures. Research indicates that such faults account for up to 43% of transmission line faults in a certain province [1]. According to statistical data from 2010 to 2020, bird-related tripping faults on transmission lines of 110(66) kV and above voltage levels operated by the State Grid Corporation of China reached 2374 incidents, accounting for 10.4% of the total number of tripping faults. As global electricity consumption continues to rise and the scale of power systems expands, preventing bird-related faults has become an increasingly urgent and complex task.

These incidents are typically caused by different species of birds, each triggering distinct types of faults. For example, faults caused by bird droppings leading to flashovers and bird nests causing short circuits are common in power systems. These faults often occur rapidly, posing sudden and significant threats to the power system. However, traditional fault inspection methods predominantly rely on manual post-fault analysis, which not only fails to accurately identify the bird species responsible for the fault but also leads to prevention measures that lack specificity and timeliness. Therefore, efficient and accurate bird species detection and identification is crucial for ensuring the safe operation of power systems and for ecological conservation [2].

Existing solutions to bird-related hazards in transmission equipment, such as bird guards and spikes, have partially mitigated the issue, but they remain limited. Many protective devices cannot fully eliminate the risks associated with these hazards, and their high costs, along with the complexity of installation and maintenance, present significant challenges. Additionally, the complex backgrounds and subtle inter-species differences in power inspection images further complicate bird hazard identification, hindering prompt intervention and effective long-term prevention. As a result, bird species identification methods based on artificial intelligence and deep learning, particularly the use of object detection technology, offer promising new possibilities for addressing this issue.

Existing studies on bird species identification on transmission lines primarily use drone aerial photography or surveillance video for automatic detection of bird nests or birds through image recognition. Advances in image processing technology have made notable progress in preventing and controlling bird-related faults on power lines. Internationally, YOLO is also widely adopted for ecological monitoring; for instance, Gayá-Vilar et al. utilized YOLOv8l-seg for cold water coral characterization, while Leong et al. applied it to seabird detection in fisheries, both validating its effectiveness in complex environments [3,4]. However, while these methods have alleviated some challenges, they continue to face limitations in detection accuracy, robustness, and real-time performance, particularly in complex environments. For image data under different weather conditions, existing augmentation strategies remain relatively limited and struggle to fully enhance the model’s generalization ability. Moreover, traditional YOLO models often experience a reduction in detection accuracy when confronted with complex backgrounds or uneven target densities, particularly in the detection of small targets, where false negatives may occur.

To address the aforementioned challenges, this paper proposes a bird species detection method for transmission lines based on weather scene data augmentation and an improved YOLOv8 model. In terms of data processing, a dual data enhancement strategy is introduced. Firstly, a weather scene enhancement technique is proposed to improve the model’s adaptability across various weather conditions by simulating the effects of different weather scenarios on the images. Secondly, the Mosaic augmentation algorithm is enhanced to strengthen the detection of small targets and improve the model’s generalization ability by optimizing image stitching and bounding box processing strategies. Furthermore, the YOLOv8 network structure is improved by incorporating channel and spatial attention mechanisms to enhance feature extraction. A feature enhancement module is designed to improve feature representation, and a small target enhancement module is added to boost the detection performance for small-sized targets. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method improves detection accuracy while maintaining superior real-time performance, offering a more effective approach for bird species identification on transmission lines. In summary, the main contributions of this work are as follows:

- A dual data augmentation strategy, including weather scene simulation and adaptive Mosaic stitching, is designed to enhance the model’s adaptability in complex weather environments and improve its generalization ability.

- The CBAM attention mechanism is embedded in the YOLOv8s architecture to enhance feature extraction, and the BiFPN is used to replace the original Neck module, enabling bidirectional feature extraction and fusion, thus strengthening the model’s feature extraction capability.

- The proposed method achieves high detection accuracy while maintaining fast inference speed, making it suitable for deployment on edge devices.

2. Related Work

Bird species detection on transmission lines is a multifaceted challenge involving object detection in power systems, small target feature optimization, and environmental robustness. This section synthesizes existing research in these three specific areas and identifies the gaps that this study aims to address.

2.1. Object Detection in Power Systems

Traditional methods for preventing bird-related faults relied on manual inspection or physical barriers, which are inefficient for large-scale grids. With the advent of deep learning, automated detection has become the mainstream approach. Early studies utilized two-stage detectors; for instance, Li et al. [5] employed Faster R-CNN to detect bird nests on transmission towers, achieving high accuracy but with limited inference speed. To meet real-time requirements, researchers shifted to one-stage detectors like the YOLO series. Ge et al. [6] and Zhang et al. [7] applied YOLOv5 to identify bird nests and birds on transmission equipment, demonstrating improved speed. Similarly, Yu et al. [8] proposed a foreign object identification model based on YOLOv7 using genetic algorithm optimization. Other lightweight models, such as PicoDet [9] and YOLOv4-tiny [10], have also been explored to reduce computational load.

While these methods have improved detection efficiency, most focus on static targets like “bird nests” [5,7,11] or general “foreign objects” [8]. They often lack the fine-grained classification capability to accurately distinguish between specific bird species (e.g., distinguishing Ciconia boyciana from Ardea cinerea), which is crucial for assessing specific threat levels. Furthermore, the trade-off between model weight and recognition accuracy remains a bottleneck for edge deployment.

2.2. Architectural Enhancements for Small Targets

Birds in transmission line inspection images typically appear as small targets with few pixels, making feature extraction difficult. To address this, recent works have focused on attention mechanisms and feature fusion.

Integrating attention modules helps the model focus on relevant features. Pei et al. [12] improved YOLOv5s by embedding the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) to detect bird intrusions. Similarly, Zhao et al. [13] proposed an Attention-Based Multi-Scale Feature Fusion (AMFF) module, and Hu et al. [14] introduced a Dynamic Attention Transformer (DATrans) to capture global context.

To minimize information loss for small targets, advanced fusion architectures have been developed. Wang et al. [15] proposed DAFPN-YOLOv8, incorporating an adaptive feature pyramid network, while Liu et al. [16] utilized a Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network (BiFPN) in a lightweight YOLO model to optimize feature flow.

Although attention mechanisms and transformers [14] improve accuracy, they often introduce significant computational overhead, making them less suitable for resource-constrained edge devices compared to pure CNNs. Additionally, standard feature fusion methods may still fail to capture the subtle features of small birds when they are camouflaged against complex backgrounds (e.g., towers or forests) [17]. This paper addresses this by combining a lightweight BiFPN with CBAM to balance feature saliency and computational efficiency [18].

2.3. Data Augmentation and Environmental Robustness

The robustness of detection models in outdoor environments relies heavily on the diversity of training data. Transmission lines are exposed to varying weather conditions, yet standard datasets often lack this variability. Existing studies [19,20] have built datasets from patrol images, and some [10] utilize standard data augmentation techniques like geometric transformations and Mosaic augmentation to expand sample size.

Current research lacks specific augmentation strategies for complex weather scenarios (e.g., fog, varying light intensities) encountered in transmission line environments, leading to poor generalization in adverse weather. Moreover, the traditional Mosaic augmentation used in [10] randomly crops images, which can truncating extremely small targets (birds), thereby hindering the training process. This study introduces a weather scenario simulation and an improved adaptive Mosaic strategy to specifically resolve these issues.

3. Methods

Bird species identification on transmission lines faces challenges related to data quality and weather environment adaptation. To address these issues, this paper proposes a dual data enhancement strategy, incorporating weather scenario simulation and an improved Mosaic enhancement method, to enhance the model’s detection performance and improve its ability to identify small targets under complex weather conditions.

3.1. Weather Scenario Data Augmentation

To enhance the model’s robustness against varying environmental conditions, we implement a comprehensive weather simulation framework. Let I(x, y) denote the RGB pixel value of the original image at position (x, y), and O(x, y) denote the output image.

- (1)

- Sunny and Cloudy Simulation

Lighting variations are simulated by transforming the image into the HSV color space and modulating the Value (V) channel. The output is converted back to RGB:

where α represents the contrast gain and β represents the brightness bias.

To ensure data diversity, these parameters are randomly sampled from uniform distributions (U) specific to each weather type:

(a) Sunny: α~U(1.1, 1.2), β~U(10, 20).

(b) Cloudy: α~U(1.1, 1.3), β~U(10, 30).

- (2)

- Fog Simulation

We simulate fog using the atmospheric scattering model combined with depth estimation based on the Dark Channel Prior (DCP). The formulation is:

where A is the atmospheric light and t(x, y) is the transmission map.

First, we compute the dark channel Dc(x, y), A is estimated by taking the max pixel value from the top 0.1% brightest pixels in Dc.

where Ω is a 15 * 15 local patch.

To ensure realism, the transmission map t(x, y) combines a depth-based component and a prior-based component:

Normalized depth is approximated as d(x, y) = Dc(x, y)/255. We set the scattering coefficient β1 = 0.6 and the preservation factor w = 0.98. The final t(x, y) is clipped to [0.1, 1.0].

- (3)

- Halo Simulation

The halo effect, representing lens flare or strong reflection on power lines, is modeled using a Point Spread Function (PSF) approach. It is defined as the addition of a radially masked Gaussian convolution:

where gσ is a Gaussian blur kernel with standard deviation, σ = 15; λ = 0.5 represents the glare intensity. M(x, y) is a radial decay mask centered at the image center (xc, yc).

where σmask is spread radius, σmask = 60.

3.2. Improved Mosaic Enhancement Method

For the bird recognition problem, given that birds are typically small in size and have low distribution coefficients in images, this paper improves the traditional Mosaic data augmentation method and proposes an adaptive scale Mosaic enhancement approach to improve training performance.

The traditional Mosaic enhancement method stitches images of fixed scales, which often overlooks the information of smaller targets in the dataset. To ensure balanced feature representation within a stitched sample, we introduce a density-based selection mechanism. First, the target density index Di for each image in the dataset is pre-calculated offline to avoid computational overhead during training:

where N is the number of targets, and wj, hj are the width and height of the j-th target bounding box.

The dataset is then sorted based on Di. During training, we select a pivot image I1 and randomly sample three adjacent images {I2, I3, I4} from the sorted list. This strategy minimizes the density variance among the four sub-images, preventing the model from biasing towards simpler sub-regions and ensuring consistent complexity.

To handle variations in target sizes, particularly outliers, we define the characteristic scale Si of image i using the median of target diagonals

where median(·) represents the operation of taking the median.

The scaling factor λi for the i-th sub-image is dynamically adjusted but clipped to a safe range to preserve small targets:

where ST is the standard input size. The stitching center (xc, yc) is then determined based on the scaled dimensions to maximize target retention.

The complete workflow, combining the weather simulation and adaptive Mosaic, is detailed in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Dual Data Enhancement Strategy |

| Input: Dataset D (Images I, Labels L), Target Size: ST Output: Augmented Batch B # --- Stage 1: Offline Preparation (Solves Scalability) --- For each image Ik in D: Calculate Density Dk. #Equation (7) Calculate Characteristic Scale Sk. #Equation (8) Sort D based on Dk # --- Stage 2: Online Training Loop --- Function GetAugmentedBatch(BatchSize N): Initialize Batch B = [] While size(B) < N: # Step A: Adaptive Mosaic Selection Select random index i Select indices {j, k, m} from neighborhood [i − 5, i + 5] in Sorted D Images_4 = [D[i], D[j], D[k], D[m]] Mosaic_Img = EmptyCanvas(2 ∗ ST, 2 ∗ ST) # Step B: Stitching & Resizing For each img in Images_4: λi = clip(ST/img.Scale, 0.5, 1.5) #Equation (9) Resize img by λi Place img into Mosaic_Img quadrant Final_Img = RandomCrop(Mosaic_Img, ST) # Step C: Weather Simulation If random() > 0.5: Weather_Type = RandomChoice([‘Fog’, ‘Sunny’, ‘Cloudy’, ‘Halo’]) If Weather_Type == ‘Fog’: Calculate A t(x, y) and O(x, y) #Equations (2)–(4) Else If Weather_Type == ‘Sunny’: Calculate O(x, y) #Equation (1) Else If Weather_Type == ‘Cloudy’: Calculate O(x, y) #Equation (1) Else If Weather_Type == ‘Halo’: Calculate M(x, y) and O(x, y) #Equations (5) and (6) Add O(x, y) to B Return B |

3.3. YOLOv8s Object Detection Model

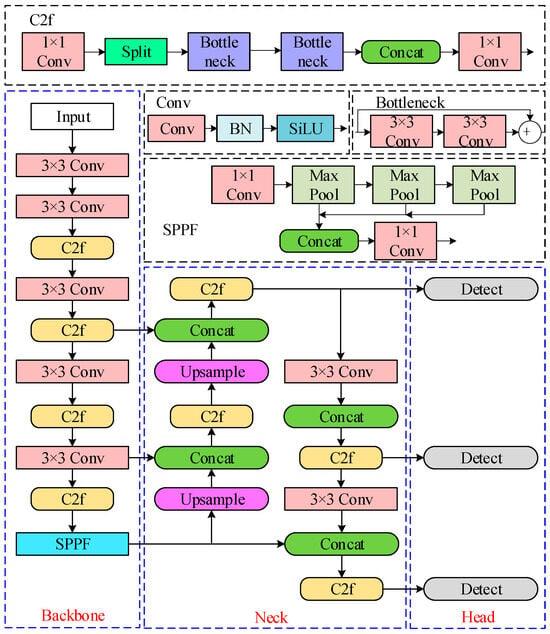

The YOLOv8 model is a widely used algorithm in the field of object detection, with YOLOv8s being a smaller version that better balances model size and computational complexity, while achieving high processing speed on edge devices. Given that bird faults occur rapidly on transmission lines, the YOLOv8s model offers a significant advantage in this context. The structure of the YOLOv8s model, as shown in Figure 1, follows the typical encoder–decoder architecture and consists of Backbone, Neck, and Head components. The Backbone primarily utilizes the CSPDarknet structure to extract multi-scale features from images, the Neck employs PANet to process targets of different sizes and perform feature fusion, and the Head is responsible for target classification and bounding box regression. However, when using the traditional YOLOv8s model for bird species detection on transmission lines, issues such as insufficient feature extraction arise, impacting the detection of small targets, and the model also struggles with processing complex backgrounds [18].

Figure 1.

Model structure of yolov8s.

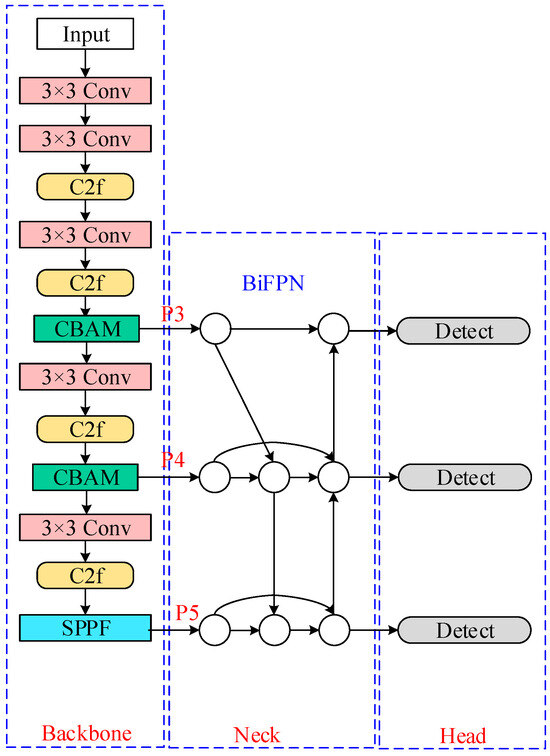

The proposed improved model primarily aims to enhance the feature extraction capability in the complex context of the model. The structure of the improved YOLOv8s model is shown in Figure 2. To enhance the fusion of multi-scale features, this paper introduces the BiFPN (Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network) structure in the Neck component, enabling bidirectional flow of features. At the same time, it adaptively adjusts the importance of different features through learnable weights. The BiFPN structure is capable of fusing more features without significantly increasing computational cost, in contrast to the PANet, which employs a single-directional path. Unlike PANet, the bidirectional path in BiFPN allows for a higher level of feature fusion, as denoted by:

where and are the input features, output features, and weight parameters of layer l, respectively; is the feature transformation function; and is a very small constant, preventing the denominator from being zero.

Figure 2.

Model structure of improved yolov8s. P3, P4, and P5 denote feature maps with down sampling strides of 8, 16, and 32, respectively.

BiFPN consists of two paths, top-down and bottom-up, with their feature update formulas given in [21]:

where is the intermediate feature of the top-down path, Conv represents the convolution operation, and fR is the up-sampling operation.

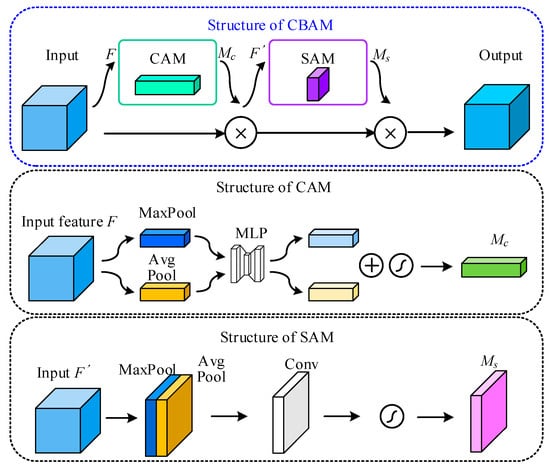

To enhance the model’s sensitivity to small targets in complex backgrounds, we integrated the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) into the Backbone. While lightweight mechanisms like Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) focus solely on channel relationships, bird detection on transmission lines requires suppressing complex spatial backgrounds (e.g., towers, forests). CBAM effectively addresses this by inferring attention maps along two separate dimensions: channel and spatial, making it superior for locating small targets. The CBAM process consists of two sequential sub-modules: the Channel Attention Module (CAM) and the Spatial Attention Module (SAM).

CAM focuses on “what” represents a bird by aggregating spatial information. The input feature map F passes through both global max-pooling and average-pooling layers, followed by a shared Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP). As shown in Figure 3, The outputs are summed and passed through a sigmoid function to generate the channel attention map Mc:

Figure 3.

Module structure of CBAM.

The feature map is then refined as F’.

SAM focuses on “where” the bird is located. It takes the output F’ from CAM and applies average-pooling and max-pooling along the channel axis. These are concatenated and convolved by a standard 7 ∗ 7 convolution layer, followed by a sigmoid function:

The final refined output is .

3.4. Transmission Line Bird Species Detection Model

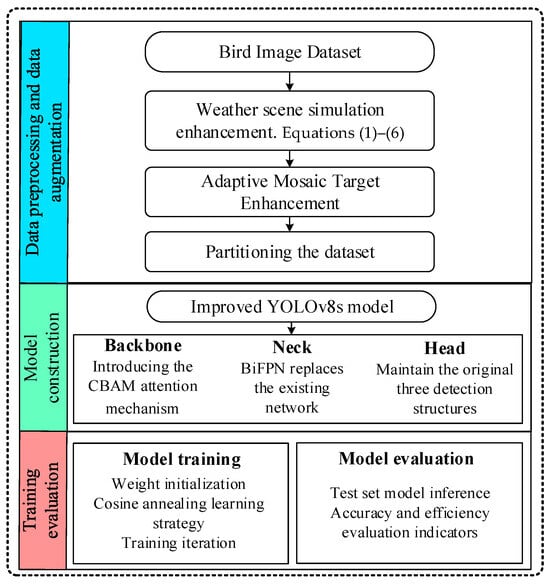

The bird species detection and identification method for transmission lines proposed in this paper is based on dual data enhancement and an improved YOLOv8s model, with the overall process shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Flow chart of proposed method.

First, a dual data enhancement strategy is introduced for the transmission line application scenario, consisting of weather scene data enhancement and adaptive Mosaic data enhancement. Weather scene simulation is applied to the dataset to replace the original images, with different weather scenes randomly generated to enhance the model’s adaptability under complex weather conditions. Then, adaptive Mosaic target enhancement is carried out, where the target density index D and stitching regions are calculated, and the optimal combination is selected for splicing. The dataset is divided into training and testing sets, and image annotations are created.

Then, the improved YOLOv8s model is used for network construction. The original structure of the Backbone is retained, with the CBAM attention module introduced after the C2f module. The intra-module features are computed through Equations (13) and (14), and BiFPN is used in the Neck part, replacing the original structure to improve small target detection capability.

Next, the model enters the training phase, where a cosine annealing learning strategy is used to set the loss function. During the model’s iteration, the loss is computed through forward propagation, and the weights and learning rate are updated via backpropagation, with the best model being saved.

Finally, the model’s performance is evaluated based on the detection results from the test set, with evaluation metrics including precision and efficiency indexes. In this paper, mAP (mean Average Precision), Precision (P), and Recall (R) are used to assess the model’s precision. Here, mAP@0.5 refers to the mean value of the average precision (AP) across all categories, where AP represents the area under the precision-recall (P-R) curve. The calculation formula is as follows:

where TP is the number of correct detections by the model; FP is the number of backgrounds incorrectly classified as targets; FN is the number of targets incorrectly predicted as backgrounds; is the precision rate when the threshold of the intersection and concatenation ratio is t; and N is the number of target categories.

Meanwhile, the computational complexity is measured by Frames Per Second (FPS), with Mpara representing the parameter sizes and (FLOPs) denoting the number of floating-point operations.

4. Experimental Analysis

To evaluate bird detection models on transmission lines, we constructed a comprehensive dataset containing 3978 high-resolution images. The dataset was constructed through two channels: field surveys within a specific province and online collection, primarily covering sunny and cloudy weather conditions. The field data were collected using surveillance equipment and mobile phone cameras during transmission line inspections in Heilongjiang Province. The image resolutions range from 152 × 160 to 4290 × 3200 pixels, stored in JPEG format with RGB color space. There are certain differences between the two data sources: field images typically have higher resolutions and, due to the shooting distance from the ground to the tower, primarily contain small and medium-sized targets. In contrast, online images vary in quality and scale. We utilized these differences to construct a dataset containing comprehensive target scales. Regarding the discrepancy in image resolution, we adopted a unified processing strategy during the training phase, where all images were resized to the standard input resolution to ensure model compatibility.

The annotation protocol strictly required tight bounding boxes around bird bodies, excluding targets with more than 50% occlusion or less than 30% visibility due to truncation. The dataset comprises 5906 annotated instances across 10 species. Among them, Anser cygnoides appears most frequently (22.6%), while Oriolus appears least frequently (6.9%). To address the challenge of scale variation, we analyzed the object scale distribution following COCO standards. Although large objects dominate, the dataset includes a critical subset of small and medium objects (approximately 11.4%). These non-large-scale objects typically represent scenes captured from a distance. The dataset was partitioned into training, validation, and test sets in a 6:2:2 ratio.

The experiments are conducted using the PyTorch 2.6.0 framework on the following hardware and software platform: CPU: Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-12400F 2.50 GHz, GPU: NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3070ti.

The model was trained using the AdamW optimizer, utilizing an input image resolution of 640 * 640 pixels and a batch size of 8. The training process spanned 200 epochs. We employed a cosine annealing learning rate schedule initialized with a 5-epoch warmup phase; the learning rate started at an initial value of 0.005 and decayed to a final value of 0.0005. The optimizer momentum was set to 0.9 with a weight decay of 0.001. To balance the training objectives, the loss function weights were configured as 7.5 for box regression, 1.5 for classification, and 1.5 for distribution focal loss (DFL), accompanied by a dropout rate of 0.1 for regularization.

4.1. Validation of the Effectiveness of Data Enhancement Strategies

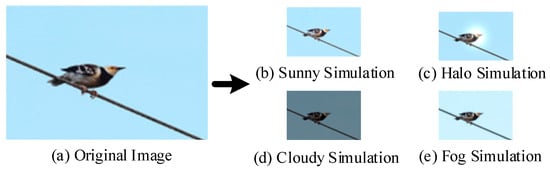

In the practical application of bird species detection on transmission lines, the images captured by monitoring systems are often affected by changes in weather and lighting conditions. The data enhancement effect of weather scenario simulation is shown in Figure 5, including sunny, cloudy, foggy, and halo effects, respectively. By introducing different weather scenarios into the original images, the model is able to extract key features of bird species under various conditions, thereby improving the robustness and generalization ability of the model in real-world applications.

Figure 5.

Weather scene result enhancement.

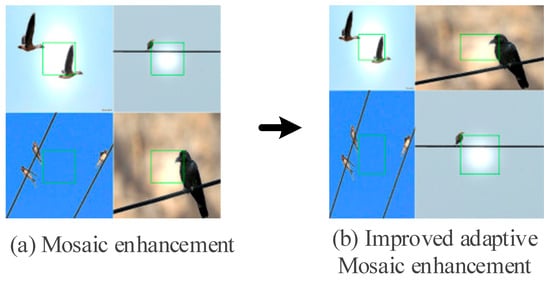

Figure 6 compares the data processing results before and after applying the improved Mosaic enhancement strategy. The improved adaptive Mosaic data enhancement method utilizes dynamically calculated centroids to achieve adaptive segmentation of the target box positions. This method better preserves the integrity of the target and enhances the adaptability to varying target sizes compared to the pre-processing approach.

Figure 6.

Improve the enhancement effect of Mosaic.

4.2. Training Results and Evaluation of the Proposed Model

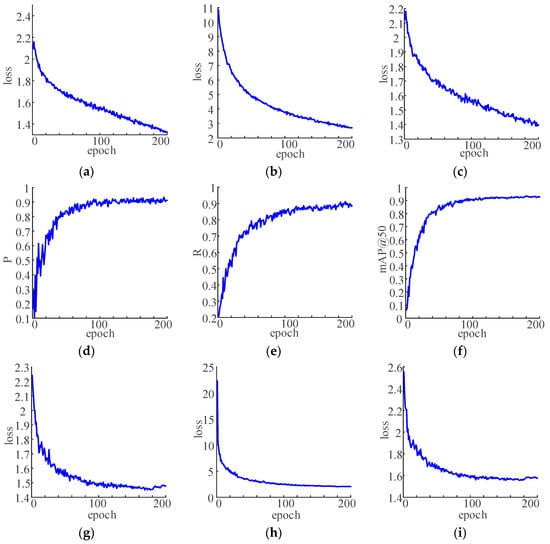

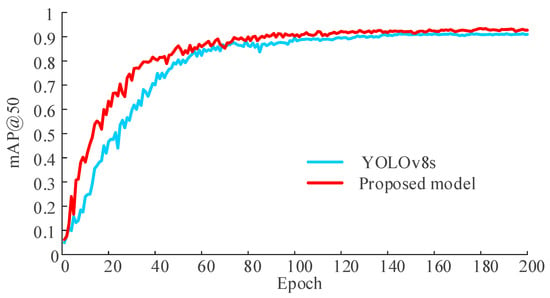

The iterative training process of the proposed improved YOLOv8s object detection model is shown in Figure 7. In the first 100 iterations, the loss curves for both the training and validation sets decrease rapidly, while the mAP@50, Precision (P), and Recall (R) curves are unstable. As the number of iterations increases, these curves flatten, indicating that the model is approaching convergence. Throughout the training process, there is no noticeable overfitting or underfitting. To verify the performance of the improved model, the original YOLOv8s model is also trained for the same number of iterations. The mAP@50 iteration curves for both models are shown in Figure 8, which demonstrate that the improved model achieves higher accuracy on the validation set and converges more quickly compared to the traditional model. When a small target bird image is input into both models, the output results, displayed in Figure 9, show that the improved model has a clear advantage in detecting small targets, with fewer missed detections compared to the YOLOv8s model, thus validating the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Figure 7.

Training curves of improved yolov8s model: (a) Training set bounding box regression loss; (b) Training set classification loss; (c) Training set freeform deformation loss; (d) Validation set accuracy curve; (e) Validation set recall curve; (f) Validation set mAP@50 curve (g) Validation set border regression loss (h) Validation set classification loss; (i) Validation set freeform deformation loss.

Figure 8.

mAP@50 curve comparison before and after improvement.

Figure 9.

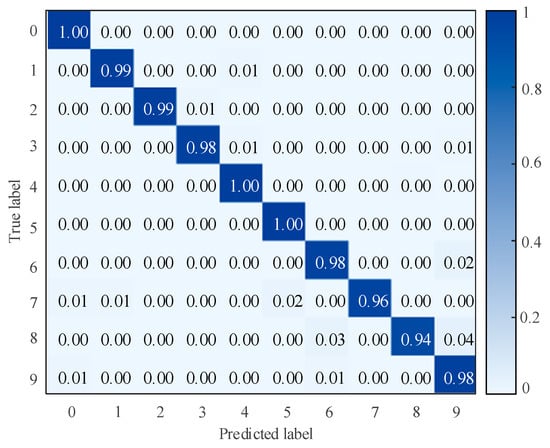

Confusion matrix for the 10 bird categories.

To further analyze the classification performance of the model on successfully detected targets, we generated a normalized confusion matrix, as shown in Figure 9. The confusion matrix measures the classification accuracy of detection results with IoU ≥ 0.5. The graph indicates that the classification accuracy of most categories is above 95%, indicating that the model has strong ability in category discrimination. However, specific misclassifications reveal the challenges posed by visual similarities and environmental factors. As shown in Figure 9, there is a significant misclassification phenomenon among the Big billed Crow (label 8), Magpie (label 6), and Swallow (label 9), with a maximum value of 4%, likely attributed to their shared black plumage and similar body contours.

The precision and efficiency evaluation metrics for the test set of the improved YOLOv8s model are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. These results demonstrate that the model exhibits high detection performance across different categories, with an average precision (P) of 94.2% and an average recall (R) of 89.7% for all categories. The mAP@50 is 94.2%. Among all categories, the highest precision and recall are achieved for the Oriolus and the Ardeola bacchus, respectively. However, due to the uneven distribution of image data quality across different categories in the dataset, variations in evaluation metrics are observed across categories. Despite this, the model demonstrates robust overall performance, enabling timely and effective bird species identification on transmission lines.

Table 1.

Accuracy evaluation of the proposed model.

Table 2.

Evaluation of the efficiency of the proposed model.

As the model is based on the YOLOv8s architecture, it has a small number of parameters. The efficiency evaluation metrics show that the model’s inference speed is high, with an average FPS greater than 24, meeting the requirements for real-time detection. The model operates at a much higher inference speed than the standard, while maintaining a small number of parameters and a low computational load. This enables the deployment of the bird species detection model for transmission lines on edge devices.

4.3. Ablation Experiments

Ablation experiments are commonly used to verify the contribution of each module to the overall model performance. In these experiments, modules are removed or replaced one by one while controlling other variables, and the model’s test results are observed. For the proposed bird species detection model for transmission lines, based on dual data enhancement and the improved YOLOv8 architecture, three types of ablation experiments are conducted: model structure ablation, data enhancement strategy ablation, and training strategy ablation. To ensure the validity of the model comparison, all experiments are carried out in the same hardware and software environment, with consistent data splits and model hyperparameter settings.

For the model structure ablation experiment, the baseline model is the original YOLOv8s, and the other two comparison models are the baseline model with the CBAM attention mechanism (CBA) and the improved model proposed in this paper. In this experiment, the same training parameters and strategy are applied, and the comparison results are shown in Table 3. It can be observed that there is almost no difference in the parameter size and computational volume among the three models. The model proposed in this paper has a slight decrease in inference speed compared to the baseline model, but it still meets the practical requirements for detection applications.

Table 3.

Results of model structure ablation comparison.

In terms of accuracy metrics, the models proposed in this paper outperform the baseline model, demonstrating higher recognition accuracy and fewer missed detections. The baseline model with the CBAM attention mechanism shows a slight improvement over the original model. Compared to the baseline model, the P, R, and mAP@50 metrics of the model in this paper improved by 2.39%, 4.42%, and 1.84%, respectively.

4.4. Comparative Experiment

To validate the detection accuracy and efficiency of the proposed method, we selected three widely used detection models for comparison. Case 1 corresponds to the CenterNet model, Case 2 to YOLOv5s, Case 3 to the RT-DETR-L (Real-Time DEtection TRansformer-Large), and Case 4 to the model proposed in this paper.

As shown in Table 4, the proposed detection model demonstrates superior performance in both detection accuracy and inference speed. Specifically, compared to the Transformer-based RT-DETR-L (Case 3), the proposed model achieves a 1.73% improvement in mAP@50 while significantly reducing the computational load by 73.6%.

Table 4.

Evaluation results of multiple comparison models.

While the model’s parameters are slightly larger than those of Case 2, they represent a reduction of 69.5% and 66.1% compared to Case 1 and Case 3, respectively. This balance makes the proposed method exceptionally suitable for deployment on edge devices. The high frame rate and superior accuracy fully meet the requirements for real-time, precise monitoring of bird species on transmission lines, validating the effectiveness of the proposed model improvements.

5. Conclusions

This paper addresses the challenge of bird species detection and identification on transmission lines by proposing a method based on dual data augmentation and an improved YOLOv8s model. The paper proposed a dual data augmentation strategy, which includes weather scene augmentation and enhanced Mosaic augmentation. Weather scene augmentation simulates real-world weather variations to improve the model’s adaptability across different environmental conditions. The improved Mosaic augmentation utilizes target density calculation and adaptive splicing to effectively enhance the model’s ability to detect small objects. The YOLOv8s structure is further improved by incorporating the CBAM attention mechanism and BiFPN network, boosting the model’s feature extraction capabilities. The effectiveness of the proposed method is validated through ablation experiments, with the proposed model achieving improvements of 2.39%, 4.42%, and 1.84% in precision, recall, and intersection over union (IoU) compared to the baseline model. Comparative experiments also demonstrate the model’s high accuracy and efficiency. The model maintains excellent detection performance while ensuring computational efficiency, making it well-suited for deployment on edge devices to meet the real-time bird species detection requirements for power transmission lines.

6. Discussion

Compared with previous studies that primarily focus on static bird nest detection or lack a balance between speed and accuracy, the proposed method achieves more accurate identification of specific bird species while maintaining relatively high efficiency suitable for edge deployment. This capability significantly enhances power grid maintenance by enabling targeted prevention measures based on the specific threats posed by different bird species, shifting the industry approach from passive defense to active, data-driven management.

Although the proposed method performs well in detecting birds on transmission lines, there are still some limitations and challenges that require critical reflection. While our mathematical weather simulation improves robustness, it remains an approximation. Real-world extreme weather involves complex physical dynamics that are not fully captured by our current model, potentially leading to performance degradation in severe conditions. The current system relies solely on RGB images, rendering it ineffective for nighttime monitoring or low-light scenarios. This lack of infrared or thermal imaging data limits the system’s applicability for continuous 24 h fault prevention.

To address these challenges, future research will focus on: (1) collecting real-world extreme weather data to fine-tune the simulation algorithms; (2) incorporating multi-modal data, such as infrared or thermal imaging, to extend detection capabilities to all-weather, 24 h monitoring.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.X. and T.C.; methodology, D.C.; software, C.W.; validation, Z.W., D.C. and C.W.; formal analysis, T.X.; investigation, T.C.; resources, R.Z.; data curation, R.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, C.W.; writing—review and editing, D.C.; visualization, C.W.; supervision, T.X.; project administration, Z.W.; funding acquisition, T.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project “Research on Bird Damage Diagnosis and Active Bird Repelling Device Methods for Transmission Lines” (grant number: SGHLHROOKJJS2400814), and the APC was funded by the same project “Research on Bird Damage Diagnosis and Active Bird Repelling Device Methods for Transmission Lines”.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available on request from the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the administrative and technical teams of State Grid Heilongjiang Electric Power Co., Ltd. Harbin Power Supply Company for their strong support during the data collection and field investigation stages of this research. Additionally, we would like to thank all individuals and institutions who have contributed to the completion of this manuscript, including those who provided relevant reference materials and constructive suggestions during the research process.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Dingyue Cheng, Zhenhao Wang, and Chong Wang were employed by State Grid Heilongjiang Electric Power Co., Ltd. Harbin Power Supply Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| CSPDarknet | Cross Stage Partial Darknet |

| PANet | Path Aggregation Network |

| BiFPN | Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network |

| CBAM | Convolutional Block Attention Module |

| CAM | Channel Attention Module |

| SAM | Spatial Attention Module |

| FPS | Frames Per Second |

| Mpara | Parameters |

| FLOPs | Floating-Point Operations |

| AP | Average Precision |

| mAP | mean Average Precision |

| P | Precision |

| R | Recall |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| DETR | Detection Transformer |

| SPD | Space-to-Depth |

| C2f_AK | Custom module in the paper, no official full name |

| FFC3 | Feature Fusion C3 |

| CSPPF | CBAM-Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast |

| AMFF | Attention-Based Multi-Scale Feature Fusion |

| DATrans | Dynamic Attention Transformer |

| GFEM | Global Feature Extraction Module |

References

- Tang, Z.; Liao, Z.; Yuan, X.; Zhu, H. Research on the Automatic Drawing System of Shaoguan Bird Damage Risk Distribution Map. Electr. Autom. 2019, 41, 86–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; Shang, J.; Yang, K.; Qi, J.; Wei, X.; Cai, Y. Insulator Image Detection Model Based on Improved YOLOv4. Guangdong Electr. Power 2023, 36, 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Gayá-Vilar, A.; Abad-Uribarren, A.; Rodríguez-Basalo, A.; Ríos, P.; Cristobo, J.; Prado, E. Deep Learning Based Characterization of Cold-Water Coral Habitat at Central Cantabrian Natura 2000 Sites Using YOLOv8. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, J.; Zhao, J.; Xue, B.; Gibson, W.; Zhang, M. Deep learning-based seabird detection in fisheries for seabird protection. J. R. Soc. N. Z. 2025, 55, 2082–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Xin, J.; Chen, T.; Xin, L.; Wei, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, H.; Tu, Y.; Zhou, X.; et al. An Automatic Detection Method of Bird’s Nest on Transmission Line Tower Based on Faster_RCNN. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 164214–164221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Li, H.; Yang, R.; Liu, H.; Pei, S.; Jia, Z.; Ma, Z. Bird’s Nest Detection Algorithm for Transmission Lines Based on Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 3rd International Conference on Computer Vision, Image and Deep Learning & International Conference on Computer Engineering and Applications (CVIDL & ICCEA), Changchun, China, 20–22 May 2022; pp. 417–420. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Gong, Y.; Wang, A.; Xu, H.; Jiang, Y. Research on Bird Identification in Power Transmission and Transformation Equipment by Using Optimized YOLOv5. J. Nanjing Inst. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 22, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, X. Foreign Objects Identification of Transmission Line Based on Improved YOLOv7. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 51997–52008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zong, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J. Lightweight bird target detection method for bird infestation prevention and control in substation. Hebei Electr. Power 2024, 43, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Z.; Zhu, X.; Liao, C.; Shi, D.; Kuang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Detection of bird species related to transmission line faults based on lightweight convolutional neural network. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2022, 16, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Chen, Y.; Fang, G.; Chen, K.; Zhang, H. Comprehensive identification method of bird’s nest on transmission line. Energy Rep. 2022, 8 (Suppl. 6), 742–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, S.; Zhang, S. Bird Invasion Detection Method for Overhead Transmission Lines Based on Improved YOLOv5s. Power Transm. Transform. Technol. 2023, 51, 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Su, H.; Zhang, J.; Ma, H.; Zou, W.; Liu, S. Attention-Based Multiscale Feature Fusion for Efficient Surface Defect Detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Huang, Y.; Li, K.; Zhang, L.; Long, C.; Zhu, Y.; Pu, T.; Peng, Z. DATransNet: Dynamic Attention Transformer Network for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2025, 22, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, C. DAFPN-YOLO: An Improved UAV-Based Object Detection Algorithm Based on YOLOv8s. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2025, 83, 1929–1949. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Wei, S.; Zhong, S.; Yu, F. YOLO-PowerLite: A Lightweight YOLO Model for Transmission Line Abnormal Target Detection. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 105004–105015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Bi, J.; Li, K.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, P. SMN-YOLO: Lightweight YOLOv8-Based Model for Small Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2025, 22, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Liang, H. Real Time Object Detection Method for Airport Flying Birds Based on Improved YOLOv8. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2024, 24, 13944–13952. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, X. Recognition of bird nests on transmission lines based on YOLOv5 and DETR using small samples. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 6219–6226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Zhu, X.; Liao, C.; Kuang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, D. Intelligent Recognition of Bird Species Related to Power Grid Faults Based on Object Detection. Power Syst. Technol. 2022, 46, 369–377. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. EfficientDet: Scalable and Efficient Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).