Abstract

Lactic acid is a compound that is consistently in high demand due to its wide range of applications. Aiming at the use of an alternative third-generation substrate for the microbial production of this organic acid, the fermentation of Porphyra umbilicalis with lactobacilli was studied. This seaweed revealed a total carbohydrate content of 51.6 ± 1.7 g/100 g biomass dry weight (DW), thus showing great potential for fermentation purposes. Thermal-acidic (at 121 °C for 30 min) hydrolysis of 100 g/L P. umbilicalis with sulfuric acid (H2SO4 5% w/v) led to the release of 37.9 ± 1.1% of the total sugars in the seaweed substrate, producing a hydrolysate with 14.7 ± 0.4, 1.1 ± 0.04 and 0.9 ± 0.04 g/L of galactose, glucose and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), respectively. After optimization of the oxygen supply conditions, fed-batch fermentation of the hydrolysate by a consortium (4LAB) of Levilactobacillus brevis, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus, and Lacticaseibacillus casei in a 2 L bioreactor produced up to 65 g/L of lactic acid with a yield of 0.58 g/g of consumed carbon sources. The 4LAB consortium was not inhibited by up to 1 g/L HMF in the medium and also showed the capacity to convert up to 88.5% of the initial HMF titer during fed-batch fermentation in the bioreactor.

1. Introduction

Lactic acid is one of the most widely used organic acids, with applications across varied manufacturing sectors. In the food industry, lactic acid plays an important role as a generally recognized as safe (GRAS) preservative and acidulant, added to processed foods to avoid spoilage by bacteria. Other common applications take advantage of its moisture-retaining properties, e.g., in the cosmetics sector, and biocompatibility, e.g., in the pharmaceuticals industry [1]. In recent times, additional focus has been given to this acid, as it is the precursor for polylactic acid (PLA) synthesis, a bioplastic recognized for its biodegradable and biocompatible character and considered among the most promising in the market of biobased polymers [2]. Due to its wide range of applications, the lactic acid market is predicted to keep growing, reaching circa 5 billion US dollars by 2028 [3].

While chemical synthesis is a possibility, microbiological production of lactic acid is the preferred method due to its mild conditions and associated lower process costs and, furthermore, the possibility of obtaining either the L or the D enantiomer with high purity. This last point is particularly important for applications such as PLA production, where the properties of the final product depend on the enantiomeric quality of the substrate [3]. However, industrial-scale microbial production of lactic acid faces issues with the reliable supply of inexpensive carbon sources. In general, established production processes utilize commercial monosaccharides and/or starch-based substrates, representing up to 70% of the total production costs [4,5]. Moreover, these carbon sources are obtained from feedstocks used mainly for food and feed; this competition is the reason why they should be avoided. Multiple studies have been performed with alternative feedstocks, such as lignocellulosic biomass and other agro-industrial wastes [4,6]. These aim at decreasing lactic acid production costs, as well as the pressure on food and feed markets. These alternative feedstocks are often associated with pre-processing issues, namely difficult pre-treatment steps that require harsh conditions, which result in the production of undesirable compounds inhibiting microbial growth [4,5].

Seaweeds or macroalgae are a group of aquatic organisms generally divided into three distinct phyla—Chlorophyta (green), Phaeophyta (brown), and Rhodophyta (red)—differing from each other in their main pigments, structural polysaccharides, and protein content [7,8]. Macroalgae production contributes to decreasing the high nitrogen and phosphorus levels in eutrophic waters and to carbon dioxide uptake and oxygen release. Seaweed cultivation neither requires arable land, freshwater resources, nor supplemental fertilization [9], thereby circumventing direct competition for terrestrial agricultural space and resources allocated to terrestrial crop production for food and feed. Due to their wide availability, high carbohydrate content, and the lesser risk they represent towards the food and feed markets, some seaweeds have been considered a potential alternative to the carbon sources currently in use for lactic acid production [10,11]. Algal biomass, despite being less recalcitrant than lignocellulosic materials, contains carbohydrates, which include fibers such as cellulose and seaweed hydrocolloids that require a pre-treatment for conversion to fermentable sugars. For this reason, several strategies have been studied for the hydrolysis of macroalgal polysaccharides, either by physicochemical or by biological methods [12,13].

Chemical treatments are widely used to hydrolyze polysaccharides, being faster and less expensive than biological and enzymatic options. Despite its cost-efficient nature, chemical treatment often leads to the formation of salts resulting from acid or base neutralization, and of compounds such as 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) and furfural, which are known microbial growth inhibitors [12,14]. Nonetheless, chemical methods have been studied extensively for the hydrolysis of seaweed polysaccharides of the red, green, and brown phyla. Some particularly successful studies include the hydrolysis of Gelidium amansii by Jang et al. [15], who reported an 80.7% saccharification yield using 3% v/v sulfuric acid (at 121 °C for 30 min). Another is the pre-treatment with 5% v/v sulfuric acid (at 121 °C for 15 min) performed by Greetham et al. [16], which attained saccharification yield values of 63%, 52.8%, and 69.1% for Porphyra umbilicalis, Laminaria digitata, and Ulva linza, respectively. Also, the saccharification of Ulva polysaccharides with 2% nitric acid (at 121 °C for 60 min), as reported by Jadhav and Sharma [17], reached a yield of 96.0%. A combination of such thermal-acidic hydrolysis treatments with enzymatic treatments is also commonly reported, e.g., with sugar recovery yields up to 84.2% for Gracilaria verrucosa treated with an enzymatic cocktail (Celluclast 1.5 L plus Viscozyme L) after hydrolysis with sulfuric acid (270 mM, corresponding to 2.6% w/v, at 121 °C for 60 min) [18].

The potential of seaweeds as a source of saccharides for lactic acid fermentation using lactobacilli was studied by Hwang et al. [19], who reported on the ability of seven species to metabolize sugars typically obtained from the hydrolysis of macroalgae and lignocellulosic biomass, namely glucose, galactose, mannose, mannitol, xylose, rhamnose, fucose, and gluconate. The authors found that although lactobacilli showed different ratios of lactic to acetic acid production depending on the carbon source, the utilization of monosaccharides typically derived from macroalgae did not present an issue when compared to sugars produced through the hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass. Results regarding lactic acid production from pre-treated seaweed biomass reported in the literature are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Outcomes from lactic acid (LA) fermentations based on pre-treated macroalgae substrates. Lactic acid titer (g/L), yield (g/g sugar), and productivity (g/(L·h)) obtained for fermentation of pre-treated macroalgae.

Porphyra umbilicalis is a red seaweed (Rhodophyta) that is also known as “laver” or “nori”. P. umbilicalis displays a high growth rate, requiring only 45 days from seeding of conchospores to harvesting, when cultivated with adequate substrates and conditions [8]. According to FAO reports, this macroalga is mostly produced in the Republic of Korea and in China, which in 2019 contributed to 20% and 71%, respectively, of the world’s production of this seaweed [29]. The most important application of P. umbilicalis is as food in Eastern cuisine, and the high price of this seaweed on the market (up to 350 EUR/kg, depending on the origin and supplier of the product) shows its high demand. For this reason, only residues of P. umbilicalis, such as kitchen leftover sushi trimmings or diseased blades from aquaculture industries, might be considered as a source of sugars for lactic acid production. P. umbilicalis has a high carbohydrate content (up to 76%) [30], consisting mainly of porphyran, an agar-like polysaccharide rich in galactose [31,32]. It is thus a potential substrate for the production of lactic acid by fermentation. This investigation examined pre-treatment and fermentation procedures applied to whole Porphyra umbilicalis biomass for lactic acid production using a mixed consortium of lactic acid bacteria, thereby evaluating its potential utility as a reliable third-generation feedstock for biobased chemical synthesis. Furthermore, this study assessed the viability of using non-detoxified polysaccharide hydrolysates as substrates for lactic acid fermentation, exploring the feasibility of circumventing conventional inhibitor-removal protocols by using inhibitor-tolerant microbial strains.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Algal Biomass

Porphyra umbilicalis biomass was obtained from ALGAS ATLÁNTICAS ALGAMAR, S.L., Pontevedra, Spain (1 kg bags, powdered with a granulometry of circa 1.0 mm). According to the information provided by the supplier, the macroalga was harvested manually along the coast of Galicia and dried at low temperatures.

2.2. Bacterial Strains

Four species of lactobacilli were included in the 4LAB consortium, namely Levilactobacillus brevis DSM 20054, Lacticaseibacillus casei ATCC393, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum ATCC 8014, and Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus ATCC 7469. This consortium of four lactic acid bacterial strains was selected based on their ability to metabolize the whole spectrum of monosaccharides released after the hydrolysis of different types of seaweed polysaccharides.

2.3. Culture Media

2.3.1. Inocula

The lactobacilli inocula were revived from cryopreservation and grown in De Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) broth (PanReac AppliChem, Barcelona, Spain).

2.3.2. Shake Flask Assays

The basal medium for all lactobacilli cultivation and fermentation experiments contained (per liter) 2 g di-ammonium hydrogen citrate (Chem-Lab, Zedelgem, Belgium), 0.05 g manganese (II) sulfate (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), and 0.4 g magnesium sulfate heptahydrate (LabChem Inc., Zelienople, PA, USA). For cultures in shake flasks, buffering salts were added to final contents of 4.5 g di-sodium hydrogen phosphate dihydrate (PanReac AppliChem, Barcelona, Spain) and 1.5 g potassium di-hydrogen phosphate (PanReac AppliChem, Barcelona, Spain). These phosphates were omitted from the basal medium in bioreactor experiments. Salts were added to the medium from concentrated solutions, namely, a solution containing di-ammonium hydrogen citrate and manganese (II) sulfate concentrated 100-fold, a magnesium sulfate heptahydrate solution concentrated 4-fold, and a Na/K buffer solution containing di-sodium hydrogen phosphate dihydrate and potassium di-hydrogen phosphate concentrated 15-fold.

To determine the LAB tolerance towards HMF, growth assays were carried out in 50 mL flasks containing 40 mL of the basal medium supplemented with (per liter) 50 mL of corn steep liquor (CSL; COPAM, Loures, Portugal) and 15 g galactose (Carl Roth GmbH + Co. KG, Karlsruhe, Germany) from a concentrated solution (100 g/L). HMF (Carbosynth, Compton, Berkshire, UK) was added to the flasks to a concentration of 1 g/L from a 21.2 g/L stock solution.

Batch fermentation assays in shake flasks with algal hydrolysate were carried out in 250 mL flasks with 200 mL working volume. The medium was based on algal hydrolysate, to which were added the remaining components from concentrated solutions. This fermentation medium contained (per liter) 838 mL algal hydrolysate, 50 mL CSL, 31.8 mL of a concentrated galactose solution (100 g/L), and the basal medium described above.

Fed-batch assays were performed in 500 mL flasks with 300 mL of the same base medium used for batch assays.

2.3.3. Bioreactor Assays

The medium used in bioreactor cultivations had a composition similar to that used in shake flask assays, except that the CSL supplement was decreased to a 40 mL/L culture medium. Also, due to automatic pH control, the buffering salts were omitted from the basal medium. During the fed-batch experiment, the pulses of galactose were given in the form of powdered D-galactose added to the bioreactor with a funnel. The powder was UV-sterilized (15 min) prior to addition to the reactor, and the addition was performed under a flame to minimize the risk of contamination.

2.4. Characterization of Porphyra umbilicalis

Moisture, total solids, ash, and total carbohydrate contents of Porphyra umbilicalis were determined using the protocols provided by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (Golden, CO, USA) [33,34].

2.5. Hydrolysis of P. umbilicalis Polysaccharides

Thermal-acidic hydrolysis of P. umbilicalis was carried out at 121 °C in 100 mL flasks with 50 mL working volume containing the suspended dry seaweed powder (100 g/L) in dilute acid solutions. The tested concentrations of sulfuric acid (Honeywell Riedel-de-Haën, GmbH, Seelze, Germany) were 0, 1, 3 and 5% (w/v) in distilled deionized water or in a sodium chloride (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) solution (3.5% w/v). Reaction times were 15 or 30 min. The hydrolysates were neutralized from an initial pH ca. 0.2–0.3 to a final pH ca. 6.2 with NaOH (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) (15 M solution) prior to any use for quantification of sugars and inhibitors of fermentation. For assays where large volumes of hydrolysate were required (bioreactor fermentations), neutralization was carried out directly with NaOH pellets (approx. 60–65 g), followed by 15 M NaOH solution to attain a final pH ca. 6.2.

A subsequent enzyme treatment was performed with Viscozyme L (Novozymes A/S, Bagsværd, Denmark) (2.2 FBGU/mL, corresponding to 0.83 mL of the enzymatic cocktail and to 0.2 g enzyme/g biomass) for 30 h (magnetic stirring at 600 rpm, 50 °C, initial pH adjusted to 4.5–5.0), on the seaweed slurry obtained from acid hydrolysis with 5% w/v H2SO4 at 121 °C for 30 min.

2.6. LAB Cultivation

2.6.1. Inocula Preparation

Bacterial strains were revived from cryopreservation by addition of the whole contents of the cryovial to 19 mL of MRS medium, followed by overnight incubation at 37 °C.

After each species revival, cells were further grown in 40 mL MRS medium at 37 °C and 100 rpm (Agitorb200, Aralab, Sintra, Portugal) overnight, to a cell culture optical density, at a wavelength of 600 nm (OD600), at approximately 10 for L. brevis, L. rhamnosus, and L. plantarum, and at approximately 5 for L. casei as this species grows slower. Aliquots were harvested in the amounts required to attain an OD600 of 0.5 of each species at the start of shake flask assays (overall starting OD600 of 1) and of 0.2 for bioreactor assays (overall starting OD600 of 0.8). These aliquots were centrifuged at 5500× g for 10 min at 4 °C (5810R centrifuge, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), the supernatants discarded, and the cell pellets kept on ice until use. Cell pellets were resuspended in 4 mL of the medium to be used in the subsequent fermentation assay and then added to the remaining culture medium (inoculation). When the 4LAB consortium was used, this procedure was carried out for all lactobacilli species, and the resuspended cell pellets were mixed together in the same tube before inoculation.

For shake flask cultivations with algal hydrolysate and the 4LAB consortium, the four cell pellets were resuspended and mixed together in 5 mL of the culture medium prepared in advance. For bioreactor assays, cell pellets of the 4LAB consortium were resuspended and mixed together in 36 mL of a 0.85% w/v NaCl solution, which was then added to the reactor with a sterile 50 mL syringe.

2.6.2. Shake Flask Fermentations

Test of Lactobacilli Tolerance Towards HMF

The study of lactobacilli tolerance towards HMF was performed by comparing growth curves obtained in media with and without the inhibitor, using the medium described in Section 2.3.2. Inoculation of the culture medium was carried out as described in Section 2.6.1. Cultivation was performed at 37 °C under orbital agitation at 100 rpm (Agitorb200, Aralab, Sintra, Portugal) until the stationary phase was reached in the HMF-supplemented cultures. Samples were taken hourly for OD600 measurements (UH5300, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) in glass cuvettes with 1 cm optical path length against blanks of culture medium diluted in the same proportion as the samples. The samples were also used for quantification of galactose, HMF, lactic acid, and acetic acid concentrations by HPLC (Section 2.7). Growth assays were carried out in duplicate.

Algal Hydrolysate Fermentations in Shake Flasks

Batch fermentations were carried out in 250 mL flasks with 200 mL culture medium (Section 2.3.2), while fed-batch fermentations were carried out in 500 mL flasks with 300 mL of medium. The assays in both modes were performed at 37 °C under orbital agitation at 100 rpm (Agitorb200, Aralab, Sintra, Portugal) and with initial pH adjusted to 6.2. Inoculation was performed with a mixture of the four species of lactobacilli (4LAB), prepared as described in Section 2.6.1. In fed-batch mode, a single pulse (17 mL) of D-galactose stock solution (100 g/L) was added when the galactose concentration in the medium reached low values, bringing the total monosaccharide concentration in the broth to 10 g/L, to prolong growth and to evaluate the effect of the fed-batch mode on the metabolism of the lactobacilli.

In all assays samples were collected from the hydrolysate, from the prepared medium prior to inoculation, and from the whole culture broth at hourly intervals for measurements of pH and of substrate and metabolite concentrations. Due to the presence of particulate matter in suspension in the medium, coming from the algal hydrolysate and CSL, quantification of bacterial growth via OD600 or cell dry weight measurements was not possible.

2.6.3. Bioreactor Fermentations

Bioreactor fermentation assays were performed using a Biostat MD 2 L fermenter (B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany) and its associated control system (dissolved oxygen, pH, temperature), at the working volume of 1.8 L. Data acquisition and conversion were performed via a MICRO MFCS (IFB RS-422) (B.Braun, Melsungen, Germany) and the respective software.

In both the batch and fed-batch fermentations, after stabilization of pH and temperature values at 6.2 and 37 °C, respectively, and calibration of the dissolved oxygen (DO) probe, the medium (see composition in Section 2.3.3) was inoculated to an initial OD600 of 0.2 for each lactobacillus, as described in Section 2.6.1. The aeration conditions were 1 v.v.m. and a minimum stirring speed of 100 rpm for the batch fermentation. For fed-batch culture, to reduce the lag-phase induced by the highly aerated environment at the beginning of the culture, aeration conditions were changed to 0.5 v.v.m. and a minimum stirring speed of 50 rpm. In both assays, there was a cascade-type control of the DO value, with a setpoint at 5% saturation. Cultivations were considered completed when galactose consumption ceased.

In the fed-batch fermentation, galactose powder was fed to the reactor at 28.2 and 50.0 h of cultivation, to bring the galactose concentration in the medium to 30 and 60 g/L, respectively, and to avoid exhaustion of the carbon source over set periods of time (16 and 48 h), based on the observed galactose consumption rate.

In all assays, samples were collected every 2 h for the measurement of glucose, galactose, HMF, lactic acid, and acetic acid concentrations.

2.7. Sample Analysis via HPLC

Quantification of glucose, galactose, lactic acid, acetic acid, and HMF and detection of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furancarboxylic acid (HMFCA) and 2,5-furan dicarboxylic acid (FDCA) were performed using HPLC (LaChrom Elite, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) with a RezexTM (Torrance, CA, USA) ROA-Organic acid H+ 8% (30 × 7.8 mm) column, using a L-2130 pump (0.5 mL/min) and a L-2200 autosampler (injection volume of 20 µL), a L-2490 refraction index (RI) detector, and a L-2420 UV-Vis detector. Sugars were detected with the RI detector, while organic acids and HMF were detected with the UV detector, all at 210 nm. The column was kept at 65 °C with a Croco-CIL 100-040-220P external heater (40 × 8 × 8 cm, 30–99 °C, Amchro GmbH, Hattersheim am Main, Germany). Elution of injected samples was performed with 5 mM H2SO4 in isocratic mode at 0.5 mL/min. Samples were prepared by diluting the supernatant of the harvested samples 20-fold with 50 mM H2SO4 and analyzed in duplicates.

Calibration curves for quantification of the HPLC-analyzed substrates and metabolites were established using standard solutions at 10 different concentration points prepared with analytical-grade chemicals and undergoing the same protocol used for samples (1:20 dilution with 50 mM H2SO4). The following ranges were used: glucose, 0.05–3.64 g/L; galactose, 0.3–30 g/L for low concentrations and 5–100 g/L for high concentrations; HMF, 0.01–2.56 g/L; lactic acid, 0.5–50 g/L; acetic acid, 0.1–10 g/L.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Porphyra umbilicalis

The proximate composition of Porphyra umbilicalis biomass (Table 2) was determined to evaluate its potential as a source of fermentable sugars, as well as of protein, lipids, and minerals.

Table 2.

Partial proximate composition of dry Porphyra umbilicalis. Results are expressed as average ± standard deviation (n = 3).

The total carbohydrate content determined by the NREL 60967 protocol showed results (51.6 ± 1.7 g/100 gDW) within the range reported by Morrissey et al. [30] (50–76%DW), and close to the values obtained by Dawczynski et al. [35] and Murata and Nakazoe [36], at 48.6 ± 5.9 and 46.5%DW, respectively. These results substantiate the potential of Porphyra umbilicalis as a source of fermentable monosaccharides, namely galactose and glucose, and the use of this alga as a sugar source for the development of biotechnological processes.

The determined ash and lipid contents, 10.8 ± 0.3 g/100 gDW and 1.4 ± 0.1 g/100 gDW, respectively, were also consistent with those found by other authors in the Porphyra genus, which typically range from 7 to 21%DW [37] and up to 2.5%DW, respectively [35,36].

3.2. Hydrolysis of Algal Biomass

Thermal-acidic hydrolysis of the P. umbilicalis biomass was tested under twelve different conditions, which included the combinations of four different concentrations of sulfuric acid (0, 1, 3 and 5% w/v), two different reaction times (15 and 30 min) and the presence or absence of NaCl (3.5% w/v).

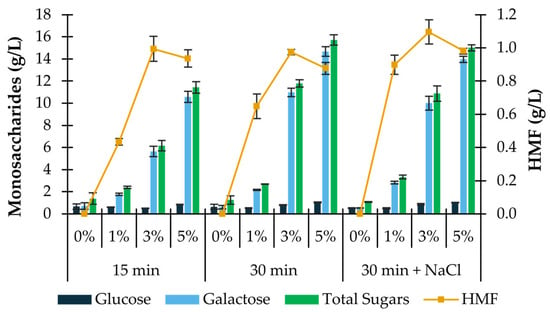

As seen in Figure 1, the final concentration of total released sugars in the hydrolysate is consistently higher for a reaction time of 30 min and increases with the concentration of sulfuric acid used. The utilization of NaCl solution instead of deionized water during the process of hydrolysis was previously shown to increase the saccharification yield of P. umbilicalis carbohydrates from 48.6% to 63.0% [16] under similar hydrolysis conditions (5% H2SO4, 121 °C, 30 min). However, in the present study, the replacement of deionized water with a sodium chloride solution (3.5% w/v) resulted in lower total monosaccharides (15.0 ± 0.3 g/L) and higher HMF (1.0 ± 0.02 g/L) concentrations when compared with those obtained under the same conditions without the addition of salt. Therefore, the best thermal-acidic pre-treatment was established as 5% H2SO4 (% w/v) and 121 °C for 30 min in deionized water. The 37.9 ± 1.1% saccharification yield attained in these conditions was lower than that reported by Greetham et al. [16] (48.6%). This might be explained by fluctuations in the composition of the algae caused by seasonal variation and geographical distribution, as well as by the different range of monosaccharides identified by these authors in their algal biomass, which, besides glucose and galactose, included xylose, arabinose, fucose, rhamnose and mannitol. These sugars were not found in the present study.

Figure 1.

Outcomes of acid hydrolysis of Porphyra umbilicalis. Concentration of glucose, galactose, total sugars, and HMF obtained after acid hydrolysis of Porphyra umbilicalis (10% w/v) with sulfuric acid (0, 1, 3, 5% w/v) for a period of 15 or 30 min at 121 °C, in the presence or absence of salt (NaCl 3.5% w/v). Results are expressed as average ± standard deviation (n = 2).

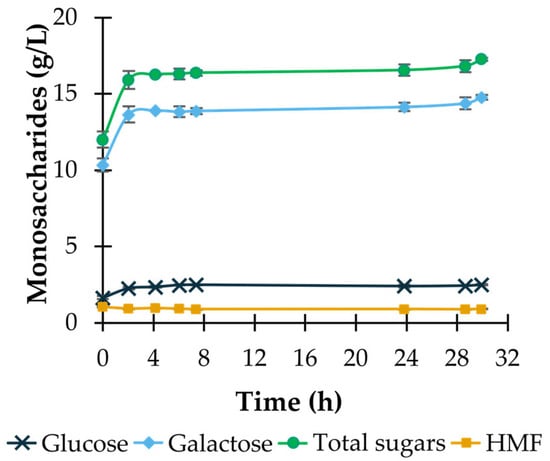

An additional step of enzymatic treatment with Viscozyme L, a carbohydrase complex composed of cellulase, hemicellulase, β-glucanase, arabanase, and xylanase, was applied after acid hydrolysis under the optimized conditions (5% sulfuric acid, 30 min, 121 °C) in an attempt to increase the concentration of monosaccharides, namely glucose and galactose, in the hydrolysate. This additional procedure increased the saccharification yield for total sugars by 10.3% after 4.7 h of incubation and by up to 12.7% after an incubation time of 30 h. Although the combined yield value of 41.7 ± 0.2% (corresponding to 17.3 ± 0.1 g/L total sugars; see Figure 2) is consistent with other results found in the literature for red macroalgae [26,38,39], this treatment cannot be considered sufficiently effective, since the majority of the galactose present in P. umbilicalis was not released; approximately 61.5% of the theoretical galactose content of the algal biomass used remained unhydrolyzed (Table 2). The limited galactose yield is most likely related to the molecular structure of porphyran, the main structural polysaccharide in P. umbilicalis, which cannot be completely hydrolyzed by the enzymes present in Viscozyme L. Despite its similarity to agarose, the hydrolysis of porphyran requires specific enzymes, known as porphyranases, to attain a high saccharification yield [40,41,42]. These enzymes were not considered as an alternative for the present study, as they are not widely available in the market and would not be an economically viable option for the future of this work. For this reason, an extension of the hydrolysis process with adequate hydrolytic enzymes should be considered in future work, resorting to microorganisms that are able to synthesize these enzymes as a means for the obtention of an enzymatic extract that could be applied to Porphyra umbilicalis in this process.

Figure 2.

Outcome of enzymatic treatment of Porphyra umbilicalis hydrolysate. Time course of the concentrations of glucose, galactose, total sugars, and HMF obtained after the sequential combination of acid hydrolysis (5% w/v sulfuric acid, 121 °C, 30 min) with enzymatic hydrolysis with Viscozyme L (2.16 FBGU/mL medium, 50 °C, 600 rpm). Concentrations in t = 0 h correspond to those obtained at the end of thermal-acidic treatment. Results are expressed as average ± standard deviation (n = 2).

3.3. Tolerance of Lactic Acid Bacteria Towards HMF

The tolerance of the four Lactobacillus species to HMF at a concentration of 1 g/L was studied to assess whether the presence of this compound in algal hydrolysates, at the obtained concentration ranges (see Figure 1), could affect the subsequent fermentations. The specific maximum growth rates (µmax) for the lactobacilli determined for the cultivations in the presence and absence of HMF are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of lactobacilli growth assays in the presence and absence of HMF. Maximum specific growth rate (µmax, h−1), D-galactose initial concentration (Gali, g/L) and consumption (Galc, %), produced lactic acid (LAp, g/L), LA yield on consumed D-galactose (YP/S, glactic acid/ggalactose), and HMF consumption (HMFc, %). Results are expressed as average ± standard deviation (n = 2).

Despite inducing a lag-phase of up to two hours in L. rhamnosus, L. casei, and L. plantarum, the presence of HMF did not affect the growth rate of the separate bacteria or the consortium, as the µmax value remained practically unchanged. At the studied concentration, HMF was not expected to cause a decrease in specific growth rate, since 1 g/L is a value 5- to 8-fold lower than those reported to impact the growth of these bacteria, according to studies by Boguta et al. [43] and Gubelt et al. [44], who reported a significant impact of HMF on lactobacilli growth starting from 5.9 and 8.0 g/L, respectively.

In all assays, the concentration of HMF decreased, which is likely a result of the conversion of the inhibitor into a less harmful compound. For example, Van Niel et al. [45] reported the ability of Lactobacillus reuteri to use HMF and furfural as electron acceptors, with furfural being reduced to furfuryl alcohol. In another study, although in a different taxonomical order, bacteria belonging to the Bacillus genus were reported to convert furfural to 2-furoic acid and HMF to 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furancarboxylic acid, 2,5-formyl-furancarboxylic acid, and 2,5-furan dicarboxylic acid [46]. The presence of two potential compounds resulting from the degradation of HMF, namely HMFCA and FDCA, was tested via HPLC. However, these compounds were not found in these cultures, due either to their actual absence or to their concentrations not reaching the limit of detection of the analytic method (3.1 mg/L for both compounds). Thus, further studies on the biological or chemical degradation of the inhibitor are needed to elucidate the fate of HMF in this process.

Finally, some of the lactobacilli tested exhibited decreased lactic acid yield (YP/S) in the presence of HMF. This phenomenon, particularly with L. rhamnosus, had already been reported in the literature by Jang et al. [15], who showed that the presence of HMF, furfural, and phenol in the hydrolysate of the macroalga Gelidium amansii, used as carbon source for fermentation, led to the decrease in the lactic acid yield from 66.0 to 53.8% despite the total consumption of the available sugars. According to data obtained (Table 3), it seems that HMF present in the culture medium at 1 g/L does not significantly impact the LA yield on substrates, with a slight reduction being observed only for L. brevis and L. rhamnosus. With the 4LAB consortium, a slight increase was even detected. The ability of the consortium to withstand the presence of HMF highlights its potential to produce lactic acid from the galactose present in P. umbilicalis hydrolysates.

3.4. Fermentation of Porphyra umbilicalis Hydrolysates

3.4.1. Shake Flask Fermentations

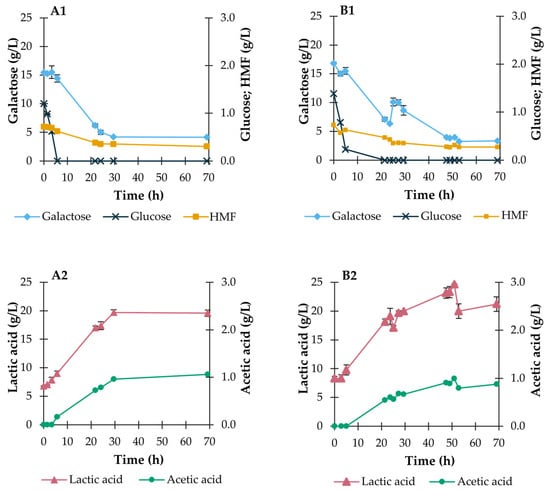

To test the ability of using P. umbilicalis hydrolysates to serve as substrates for lactic acid production, batch and fed-batch fermentations were first carried out in shake flasks in pH-buffered media, as described in Section “Algal Hydrolysate Fermentations in Shake Flasks”. The selected hydrolysate was the one obtained after the thermal acidic treatment with 5% (w/v) H2SO4 containing ca. 14 g/L galactose, ca. 1 g/L glucose, and ca. 0.9 g/L HMF. A galactose supplement was included in the initial medium up to an initial concentration of approximately 15 g/L galactose. Since concentrated Porphyra hydrolysates were not available to be used as feed later in the fed-batch assay, a concentrated galactose solution (100 g/L) was used instead. From the results presented in Section 3.3, the 4LAB consortium was chosen as the best inoculum. The evolution of the concentrations of monosaccharides, organic acids, and HMF was assessed in these shake flask fermentation runs (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Outcome of batch and fed-batch fermentations of P. umbilicalis thermal-acidic hydrolysates during shake flask fermentation with the 4LAB consortium. A—Batch mode; B—Fed-batch mode. Evolution of the concentrations (g/L) of glucose, galactose, and HMF (A1,B1), and of lactic and acetic acids (A2,B2). Culture conditions: (A) 200 mL working volume, 37 °C, 100 rpm orbital agitation; (B) 300 mL working volume, 37 °C, 100 rpm orbital agitation. Results are expressed as average ± standard deviation (n = 2).

In accordance with what was observed during the growth assays in defined medium (see Section 3.2), the 4LAB consortium did not undergo a latency period after inoculation in the hydrolysate-based medium, in both operational modes, despite lactic acid and HMF being already present in the medium (Figure 3). The concentration of HMF was below that previously tested (Section 3.2), and the pH value at the beginning of the fermentation was approximately 6.2, well above the pKa value of lactic acid (3.86), so inhibition effects, particularly by undissociated lactic acid, were not likely to occur. Moreover, the presence of glucose also ensured the absence of a culture lag phase. Also, the preference of the consortium for glucose over galactose with a catabolite repression effect [47] is clear in Figure 3A1,B1.

In terms of metabolite synthesis, both lactic and acetic acid were produced (Figure 3A2), reaching final concentrations of 19.6 ± 0.6 and 1.06 ± 0.01 g/L, respectively, in the batch operational mode, giving a lactic acid yield of 0.88 g/g consumed sugars, corresponding to an overall lactic acid productivity of 0.19 g/(L·h). A maximum lactic acid productivity of 0.47 g/(L·h) was reached at 21.8 h of cultivation. These values are higher than those obtained by Jang et al. [15] and Mwiti et al. [22] in batch mode fermentations using Gelidium amansii and agar acid hydrolysates as substrates (Table 1), respectively. Although the growth and metabolic activity of the four species of lactobacilli cannot be individually quantified, the presence of acetic acid is evidence of the metabolism of Levilactibacillus brevis, the only heterofermentative bacterium in the consortium [48]. This bacterium was added to the consortium for its ability to metabolize pentoses, which are part of the composition of algal polysaccharides, eventually leading to the full consumption of all monosaccharides in the medium [22]. Moreover, this bacterium has shown high tolerance towards inhibitors generated during acid hydrolysis of lignocellulosic substrates [44].

Regarding the fed-batch experiment with 4LAB, due to the galactose pulse introduced in the culture when glucose had been depleted (see Figure 3B1), the attained lactic acid titer was slightly higher than that obtained in the batch run (see Figure 3A2,B2). The LA titer reached 24.64 ± 0.05 g/L corresponding to a yield of 0.50 g/g consumed sugars and a productivity of 0.32 g/(L·h). The maximum productivity of 0.42 g/(L·h) was reached at 27.3 h of cultivation, measured two hours after the galactose pulse, and is higher than that attained by Mwiti et al. [22] using agar acid hydrolysate supplemented with glucose pulses in fed-batch mode (Table 1). It should be noted that at the time of the galactose pulse, the pH of the broth had decreased to around 4.3, below the pKa of acetic acid (4.76), already present though at low concentrations (see Figure 3B2) and close to the pKa of lactic acid. For this reason, the metabolic activity of the lactobacilli was expected to be reduced due to the inhibitory effects of the organic acids in their unprotonated forms [49]. However, a fast consumption of galactose was still observed (see Figure 3B1).

In view of the overall good performance of the 4LAB consortium in the shake flask assays, the scaling up of the fermentation of Porphyra umbilicalis hydrolysate in a benchtop bioreactor using this consortium was carried out.

3.4.2. Bioreactor Fermentations

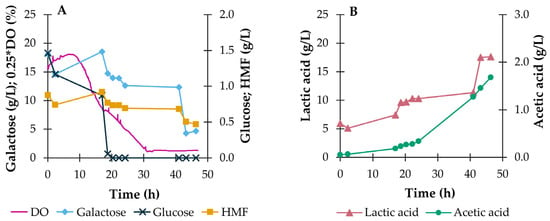

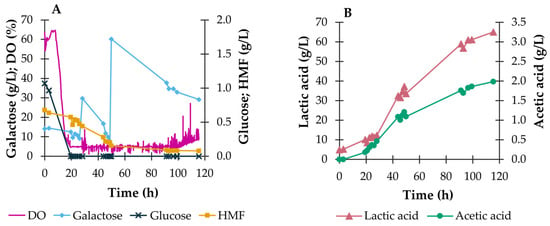

Fermentations in a 2 L benchtop reactor were performed both in the batch and fed-batch mode using the 4LAB consortium as inoculum and an initial medium composition similar to that used in shake flasks (Section 3.4.1), except the buffering phosphates, since the pH value was controlled at 6.2 with the addition of an alkaline solution (NaOH 4 M). The concentrations of monosaccharides, metabolites and HMF were measured during the cultivation time and are represented in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Outcome of bioreactor batch fermentation of P. umbilicalis thermal-acidic hydrolysate during the batch-operated bioreactor fermentation with the 4LAB consortium. Evolution of DO (%) and of the concentrations (g/L) of glucose, galactose, HMF (A), and lactic and acetic acids (B). Cultivation conditions: 1.8 L working volume, 37 °C, pH 6.2, aeration at 1 v.v.m., DO set point at 5% of saturation.

Figure 5.

Outcome of bioreactor fed-batch fermentation of P. umbilicalis thermal-acidic hydrolysate during the fed-batch bioreactor fermentation with the 4LAB consortium. Evolution of DO (%) and of the concentrations (g/L) of glucose, galactose, and HMF (A), and lactic and acetic acids (B) Cultivation conditions: 1.8 L working volume, 37 °C, pH 6.2, aeration at 0.5 v.v.m. DO set point at 5% of saturation.

The batch fermentation performed in the bioreactor with controlled pH and aeration (1 v.v.m.) led to final concentrations of all the analyzed compounds similar to those obtained in the shake flask, namely 18.0 g/L of lactic acid (corresponding to a yield of 0.69 g/g consumed sugars), 1.7 g/L of acetic acid and 0.5 g/L of HMF (corresponding to a conversion yield of 32.0%), indicating an adequate scaling up of the culture. However, two latency periods were observed, specifically at 0–17 and 24–41 h of cultivation, during which the consumption of glucose and galactose and production of lactic acid occurred at very slow rates (Figure 4). This led to an overall lactic acid productivity of 0.28 g/(L·h), well below some of the values reported in the literature in this study’s context (see Table 1), with a maximum productivity of 0.30 g/(L·h) reached at 41 h of cultivation. Moreover, although the scale-up was considered adequate, the lactic acid yield decreased from 0.88 to 0.69 g/g consumed sugars, which indicates the diversion of carbon from the synthesis of the organic acid to other metabolites or towards cell growth. This deviation could be explained by the excess of dissolved oxygen at the beginning of the cultivation, which took 30 h to decrease to the established set point of 5% (microaerophilic environment). The presence of oxygen could have contributed to the concomitant production of lactic acid and carbon dioxide, diverting part of the supplied carbon to the production of CO2 and decreasing the yield of the organic acid. Although the CO2 content of the exit gas stream of the reactor was not monitored in these experiments, this event seems a likely cause of the lower yield observed.

The first lag period was expected, since lactobacilli are mostly facultative or strictly anaerobic bacteria, thus sensitive to the DO level. Plus, the inoculum for this assay was prepared under microaerophilic conditions. Upon transfer to a medium aerated at 1 v.v.m. and with an initial DO value at 64% of saturation (see Figure 4), the inoculum would require an adaptation period to the aerated environment inside the reactor [50]. The second latency period coincided with the total consumption of the glucose available in the medium, which implied a new period of adaptation of the bacteria to galactose, in a typical diauxic growth pattern.

To avoid the initial 17 h lag-phase observed in the batch fermentation run, the aeration rate in the fed-batch assay was decreased to 0.5 v.v.m., with a minimum stirring speed of 50 rpm in the cascade DO control setting. These changes allowed a quicker adaptation of the lactobacilli to the DO conditions in the reactor, resulting in the immediate consumption of glucose and galactose by the consortium upon inoculation (Figure 5A). These improved aeration conditions led to a faster approach to the established DO set point (5% of saturation), which was reached at 11 h of cultivation.

Fed-batch fermentation in the bioreactor used pulse additions of solid galactose instead of a concentrated sugar solution, to avoid diluting the other components of the medium. This is especially relevant in fed-batch cultivations with galactose due to its low solubility in water (circa 100 g/L). Over the 115.5 h of cultivation, two feeds of solid galactose were given (at 28.2 and 50.0 h), to take advantage of its rapid consumption, which occurred as soon as glucose was depleted from the broth. However, the last feed pulse, which increased the concentration of galactose from 7.8 to 60.2 g/L, was apparently excessive, particularly when coupled to the scarcity of other nutrients and growth factors that likely occurred towards the end of the cultivation. Moreover, the prolonged fed batch under high galactose concentrations might have imposed osmotic stress on the cells, with consequent lower cell performance. Therefore, a marked decrease in the rate at which the 4LAB consortium metabolized the added carbon source was observed, and 29.1 g/L of galactose was left over at the endpoint of the fermentation (see Figure 5A). Overall lactic acid productivity, at 0.52 g/(L·h), was higher compared with the batch fermentation but also suffered from the poorly productive period following the last galactose pulse (a maximum value of 0.66 g/(L·h) had been reached just before this pulse).

The optimized DO control and the increased galactose supply in the fed-batch fermentation also led to a more effective HMF conversion of 88.5%. Prior to the first galactose feed, in the first 30 h of cultivation, the conversion of HMF had reached a value (30.3%) similar to that attained in batch mode (32.0%) after 50 h. Further, a higher HMF conversion (70.4%) was attained before the second galactose feed. It can thus be inferred that HMF conversion is related to cell metabolism, since larger conversions were observed when growth is promoted in adequate conditions, i.e., a DO of 5% sat and wider availability of carbon as a result of the galactose feed.

It should also be mentioned that the adaptation of the aeration settings to attain the 5% saturation setpoint might have also contributed to the increase in the lactic acid yield, from 0.50 g/g consumed sugars in shake flasks to 0.58 g/g consumed sugars in bench-scale bioreactors. This increase was not verified when the scaling up the cultures in batch mode, and this might be related to the excess oxygen, as mentioned before. A further decrease in the aeration rate and stirring speed should be tested in future assays to increase the yield and productivity of lactic acid.

During both fermentation runs in the bioreactor, as had happened in shake flasks, lactic acid was the main product of bacterial metabolic activity, together with much smaller concentrations of acetic acid. Both acids reached higher concentrations in the fed-batch bioreactor fermentation due to the higher amount of supplied carbon source and the controlled pH values, which maintained the organic acids in their dissociated forms (lactate and acetate), therefore not compromising lactobacilli viability. The 65.0 g/L of lactic acid produced in fed-batch mode is a high titer when compared to reported values in the literature, such as 31.9 g/L reported by Mwiti et al. [22] and 57.6 g/L reported by Tabacof et al. [20], using commercial glucose and galactose as carbon sources. When considering the yield of lactic acid production on consumed sugars, a value of 0.58 g/g is attained, which is lower than that obtained by Tabacof et al. [20] (0.8 g/g consumed sugars), despite the lower lactic acid titer. This yield is also close to that obtained by Mwiti et al. [22] (0.5 g/g consumed sugars), although the attained lactic acid concentration is over 2-fold higher. In contrast, in the batch fermentation, a lactic acid yield of 0.88 g/g consumed sugars was attained.

Studies on the production of lactic acid by lactobacilli using red algae hydrolysates in bioreactor fermentations are scarce, but the yield values attained in the present study are between those reported by Jang et al. [15] using Gelidium amansii (0.42 g/g consumed sugars in batch mode) and by Tabacof et al. [21] using Kappaphycus alvarezii (1.2 and 1.0 g/g consumed sugars in pulse and extended fed-batch modes, respectively). Nonetheless, the conditions applied in these studies differed in feeding strategy, aeration and stirring speed, and inoculum size, all factors contributing to the differences found between the results. Further improvement of the cultivation conditions and of the operational modes used in this work will thus be worthwhile.

The recovery and purification of the lactic acid produced by the fermentation of Porphyra hydrolysates is outside the scope of this work. Nevertheless, it was thought important to investigate if the residual fermented culture broth would still be a valuable byproduct for food and feed applications once lactic acid had been recovered. With this purpose, upon completion of the bioreactor fermentation, the whole broth was sampled, lyophilized and analyzed for protein content and amino acid profile [51,52], the results of which were compared with those obtained for crude seaweed (the raw material). The results are disclosed in Figures S1 and S2 (Supplementary Material). One may observe that the amino acid profiles are very similar between fermented broth and crude seaweed, although the total protein and amino acid contents are lower in the broth. However, one must consider that, after lactic acid extraction, the amino acid contents (in g/100 g dry residual broth) will increase. Thus, there is an undeniable nutritional value in the culture broth after lactic acid recovery, a byproduct that should not be disregarded.

4. Conclusions

Aiming at lactic acid production, the carbohydrate fraction of P. umbilicalis was hydrolyzed to monosaccharides by thermal-acidic treatment with a sulfuric acid solution (100 g biomass/L; 5% w/v H2SO4, 121 °C, 30 min). This treatment was shown to release 0.38 g sugars/g total sugars in the algal biomass and thus was the most adequate among the tested variants. Under these conditions, the attained titer of the produced HMF inhibitor (circa 1 g/L) was shown not to be toxic for the lactobacilli consortium used in fermentation assays on the obtained hydrolysate.

Shake flask fermentation in batch mode led to the highest lactic acid yield from the available carbon sources (0.88 g/g consumed sugars) in comparison to those obtained in bioreactors under batch (0.69 g/g consumed sugars) and fed-batch (0.58 g/g consumed sugars) operation modes. This opens the scope to further investigation, namely, on the impact of the dissolved oxygen concentration on productivity. In the fed-batch mode, for instance, a strategy consisting of an initial aerobic period to promote growth, followed by a microaerophilic, fine-tuned phase to foster production, is worth testing.

The utilization of the carbohydrate fraction of whole macroalgae, or their industrial residues, as a source of sugars to develop biotechnological processes is still very much dependent on the supply of commercial enzymes able to degrade the complex, unique polysaccharides found in these algae. While these enzymes remain unavailable, thermo-acidic methods or broad scope enzymes, such as the Viscozyme L cocktail here tested, have been used, with limited results in terms of sugar yield (based on the algal total carbohydrate content). When compared with published research data, the bioreactor fermentations carried out in this work with whole P. umbilicalis hydrolysates attained high lactic acid titers (65 g/L in fed-batch mode). Although further optimization of culture conditions and operational modes is needed, Porphyra umbilicalis is herein shown to be a promising feedstock for microbial production of lactic acid. Moreover, the possibility of the cultivated Porphyra biomass being replaced by its residues, such as trimmings from the laver processing industry [53] or laver-based food products that have reached their expiry date, should be considered in view of contributing to a circular economy and towards the carbon neutrality of the production of lactic acid and its derivatives [54].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152412946/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M., H.M.P. and M.T.C.; methodology, A.S.F., M.M. and M.T.C.; validation, M.M. and M.T.C.; formal analysis, M.M. and M.T.C.; investigation, A.S.F.; resources, M.T.C.; data curation, M.M., H.M.P. and M.T.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.F.; writing—review and editing, M.M., H.M.P., M.M.R.d.F. and M.T.C.; supervision, M.M. and M.T.C.; project administration, H.M.P. and M.T.C.; funding acquisition, M.M.R.d.F. and M.T.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded with national funds from Fundo Azul—DGPM, project FA_05_2017_033. Financial support was also received by national funds from FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e da Tecnologia, I.P., in the scope of the project UIDB/04565/2020 and UIDP/04565/2020, and of the project LA/P/0140/2020 of the Associate Laboratory Institute for Health and Bioeconomy—i4HB.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank the colleague Gabriel Monteiro (iBB-IST) for kindly supplying the lactobacilli strains used in this study; the colleagues Isa Marmelo and António Marques from the Portuguese Institute for Sea and Atmosphere, I. P. (IPMA, IP), partner of the Fundo Azul—DGPM project; for determination of the lipids and protein content of the alga P. umbilicalis; Carla Motta from the Portuguese National Institute of Health Doutor Ricardo Jorge (INSA) for determination of amino acids profiles; and COPAM, São João da Talha, Portugal, for the supply of CSL.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 4LAB | Consortium of lactobacilli composed of L. brevis, L. casei, L. plantarum, and L. rhamnosus |

| CSL | Corn steep liquor |

| DO | Dissolved oxygen |

| DW | Dry weight |

| FDCA | 2,5-furan dicarboxylic acid |

| HMF | 5-hydroxymethylfurfural |

| HMFCA | 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furancarboxylic acid |

| LA | Lactic acid |

| OD600 | Optical density measured at the wavelength of 600 nm |

| RI | Refraction index |

| v.v.m. | Volume of air, per volume of liquid medium and per minute |

References

- Kim, J.; Kim, Y.M.; Lebaka, V.R.; Wee, Y.J. Lactic Acid for Green Chemical Industry: Recent Advances in and Future Prospects for Production Technology, Recovery, and Applications. Fermentation 2022, 8, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, N.; Mondal, A. Synthesis, Properties, Environmental Degradation, Processing, and Applications of Polylactic Acid (PLA): An Overview. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 11421–11457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Hu, Z.; Pu, Y.; Wang, X.C.; Abomohra, A. Bioprocesses for Lactic Acid Production from Organic Wastes toward Industrialization—A Critical Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 369, 122372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shang, N.; Li, P. Microbial Fermentation Processes of Lactic Acid: Challenges, Solutions, and Future Prospects. Foods 2023, 12, 2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Yang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Xin, F. Advances and Prospects for Lactic Acid Production from Lignocellulose. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2025, 182, 110542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandri, M.; Schneider, R.; Mehlmann, K.; Venus, J. Recent Advances in D-Lactic Acid Production from Renewable Resources: Case Studies on Agro-Industrial Waste Streams. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2019, 57, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, M.; Miyoshi, T. Algal Fermentation—The Seed for a New Fermentation Industry of Foods and Related Products. Jpn. Agric. Res. Q. JARQ 2013, 47, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baweja, P.; Kumar, S.; Sahoo, D.; Levine, I. Biology of Seaweeds. In Seaweed in Health Disease Prevention; Fleurence, J., Levine, I., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 41–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Jin, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Q.; Wu, J. The Considerable Environmental Benefits of Seaweed Aquaculture in China. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2019, 33, 1203–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.R.W.Y.; Tan, I.S.; Foo, H.C.Y.; Lam, M.K.; Lim, S. Potential of Macroalgae-Based Biorefinery for Lactic Acid Production from Exergy Aspect. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 13, 2623–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, S.L.; Tan, I.S.; Foo, H.C.Y.; Lam, M.K.; Lee, K.T. Third-Generation L-Lactic Acid Biorefinery Approaches: Exploring the Viability of Macroalgae Detritus. BioEnergy Res. 2024, 17, 2100–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneein, S.; Milledge, J.J.; Nielsen, B.V.; Harvey, P.J. A Review of Seaweed Pre-Treatment Methods for Enhanced Biofuel Production by Anaerobic Digestion or Fermentation. Fermentation 2018, 4, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babich, O.; Ivanova, S.; Michaud, P.; Budenkova, E.; Kashirskikh, E.; Anokhova, V.; Sukhikh, S. Fermentation of Micro- and Macroalgae as a Way to Produce Value-Added Products. Biotechnol. Rep. 2024, 41, e00827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meinita, M.D.N.; Hong, Y.K.; Jeong, G.T. Comparison of Sulfuric and Hydrochloric Acids as Catalysts in Hydrolysis of Kappaphycus alvarezii (Cottonii). Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2012, 35, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, S.; Shirai, Y.; Uchida, M.; Wakisaka, M. Potential Use of Gelidium amansii Acid Hydrolysate for Lactic Acid Production by Lactobacillus rhamnosus. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2013, 51, 131–136. [Google Scholar]

- Greetham, D.; Adams, J.M.; Du, C. The Utilization of Seawater for the Hydrolysis of Macroalgae and Subsequent Bioethanol Fermentation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, A.; Sharma, M. Dilute Nitric Acid Pretreatment of Ulva Biomass for Production of Fermentable Sugars and Its Validation Using Design of Experiments (DoE). Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024, 15, 24853–24867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ra, C.H.; Choi, J.G.; Kang, C.H.; Sunwoo, I.Y.; Jeong, G.T.; Kim, S.K. Thermal Acid Hydrolysis Pretreatment, Enzymatic Saccharification and Ethanol Fermentation from Red Seaweed, Gracilaria verrucosa. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Lett. 2015, 43, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, S.M.; Lee, S.B. Fermentation of Seaweed Sugars by Lactobacillus Species and the Potential of Seaweed as a Biomass Feedstock. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2011, 16, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabacof, A.; Calado, V.; Pereira, N. Third Generation Lactic Acid Production by Lactobacillus pentosus from the Macroalgae Kappaphycus alvarezii Hydrolysates. Fermentation 2023, 9, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabacof, A.; Calado, V.; Pereira, N. Lactic Acid Fermentation of Carrageenan Hydrolysates from the Macroalga Kappaphycus alvarezii: Evaluating Different Bioreactor Operation Modes. Polysaccharides 2023, 4, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwiti, G.; Yeo, I.S.; Jeong, K.H.; Choi, H.S.; Kim, J. Activation of Galactose Utilization by the Addition of Glucose for the Fermentation of Agar Hydrolysate Using Lactobacillus brevis ATCC 14869. Biotechnol. Lett. 2022, 44, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagarajan, D.; Oktarina, N.; Chen, P.T.; Chen, C.Y.; Lee, D.J.; Chang, J.S. Fermentative Lactic Acid Production from Seaweed Hydrolysate Using Lactobacillus sp. and Weissella sp. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, D.; Nandini, A.; Dong, C.D.; Lee, D.J.; Chang, J.S. Lactic Acid Production from Renewable Feedstocks Using Poly(vinyl alcohol)-Immobilized Lactobacillus plantarum 23. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 17156–17164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, C.Y.; Tan, I.S.; Foo, H.C.Y.; Lam, M.K.; Tong, K.T.X.; Lee, K.T. Sustainable and Green Pretreatment Strategy of Eucheuma denticulatum Residues for Third-Generation l-Lactic Acid Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 330, 124930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.T.V.; Huang, M.Y.; Kao, T.Y.; Lu, W.J.; Lin, H.J.; Pan, C.L. Production of Lactic Acid from Seaweed Hydrolysates via Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermentation. Fermentation 2020, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Bae, J.; Shin, H.; Kim, M.; Yang, E.; Lee, K.H.; Yoo, H.Y.; Park, C. Improved Recovery of Mannitol from Saccharina japonica under Optimal Hot Water Extraction and Application to Lactic Acid Production by Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus. GCB Bioenergy 2024, 16, e13166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Lan, C.C.; Pan, C.L.; Huang, M.Y.; Chew, C.H.; Hung, C.C.; Chen, P.H.; Lin, H.T.V. Repeated-Batch Lactic Acid Fermentation Using a Novel Bacterial Immobilization Technique Based on a Microtube Array Membrane. Process Biochem. 2019, 87, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020; Sustainability in Action; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2020; ISBN 978-92-5-132692-3. [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey, J.; Kraan, S.; Guiry, M.D. A Guide to Commercially Important Seaweeds on the Irish Coast; Bord Iascaigh Mhara/Irish Sea Fisheries Board: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Peat, S.; Turvey, J.R.; Rees, D.A. 311. Carbohydrates of the Red Alga, Porphyra umbilicalis. J. Chem. Soc. (Resumed) 1961, 1590–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaudo, M. Seaweed Polysaccharides. Compr. Glycosci. Chem. Syst. Biol. 2007, 2–4, 691–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wychen, S.; Laurens, L.M.L. Determination of Total Carbohydrates in Algal Biomass: Laboratory Analytical Procedure (LAP); No. NREL/TP-2700-87500; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wychen, S.; Laurens, L.M.L. Determination of Total Solids and Ash in Algal Biomass: Laboratory Analytical Procedure (LAP), Revised ed.; No. NREL/TP-2700-87520; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dawczynski, C.; Schubert, R.; Jahreis, G. Amino Acids, Fatty Acids, and Dietary Fibre in Edible Seaweed Products. Food Chem. 2007, 103, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, M.; Nakazoe, J.I. Production and Use of Marine Algae in Japan. Jpn. Agric. Res. Q. JARQ 2001, 35, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdt, S.L.; Kraan, S. Bioactive Compounds in Seaweed: Functional Food Applications and Legislation. J. Appl. Phycol. 2011, 23, 543–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Sunwoo, I.Y.; Jeong, G.T.; Kim, S.K. Detoxification of Hydrolysates of the Red Seaweed Gelidium amansii for Improved Bioethanol Production. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2019, 188, 977–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.W.; Hong, C.H.; Jeon, S.W.; Shin, H.J. High-Yield Production of Biosugars from Gracilaria verrucosa by Acid and Enzymatic Hydrolysis Processes. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 196, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turvey, J.R.; Christison, J. The Enzymic Degradation of Porphyran. Biochem. J. 1967, 105, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correc, G.; Hehemann, J.H.; Czjzek, M.; Helbert, W. Structural Analysis of the Degradation Products of Porphyran Digested by Zobellia galactanivorans β-Porphyranase A. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 83, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, B. Directed Preparation of Algal Oligosaccharides with Specific Structures by Algal Polysaccharide Degrading Enzymes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boguta, A.M.; Bringel, F.; Martinussen, J.; Jensen, P.R. Screening of Lactic Acid Bacteria for Their Potential as Microbial Cell Factories for Bioconversion of Lignocellulosic Feedstocks. Microb. Cell Factories 2014, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubelt, A.; Blaschke, L.; Hahn, T.; Rupp, S.; Hirth, T.; Zibek, S. Comparison of Different Lactobacilli Regarding Substrate Utilization and Their Tolerance Towards Lignocellulose Degradation Products. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 3136–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Niel, E.W.J.; Larsson, C.U.; Lohmeier-Vogel, E.M.; Rådström, P. The Potential of Biodetoxification Activity as a Probiotic Property of Lactobacillus reuteri. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 152, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, M.L.; Lizarazo, L.M.; Rojas, H.A.; Prieto, G.A.; Martinez, J.J. Biotransformation of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural and Furfural with Bacteria of Bacillus Genus. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2022, 39, 102281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutscher, J. The Mechanisms of Carbon Catabolite Repression in Bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2008, 11, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Wittouck, S.; Salvetti, E.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Harris, H.M.B.; Mattarelli, P.; O’toole, P.W.; Pot, B.; Vandamme, P.; Walter, J.; et al. A Taxonomic Note on the Genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 Novel Genera, Emended Description of the Genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and Union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 2782–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passos, F.V.; Fleming, H.P.; Ollis, D.F.; Hassan, H.M.; Felder, R.M. Modeling the Specific Growth Rate of Lactobacillus plantarum in Cucumber Extract. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1993, 40, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotta, T.; Guidone, A.; Ianniello, R.G.; Parente, E.; Ricciardi, A. Temperature and Respiration Affect the Growth and Stress Resistance of Lactobacillus plantarum C17. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 115, 848–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, C.; So, A.; Soares, A.; Gonzales, G.B.; Cabral, I.; Tavares, N.; Nicolai, M. Amino acid profile of foods from the Portuguese Total Diet Pilot Study. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2020, 92, 103545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, C.; Santos, M.; Mauro, R.; Samman, N.; Sofia, A.; Torres, D.; Castanheira, I. Protein content and amino acids profile of pseudocereals. Food Chem. 2016, 193, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Gao, T.; Ge, F.; Sun, H.; Cui, Z.; Wei, Z.; Wang, S.; Show, P.L.; Tao, Y.; Wang, W. Porphyra yezoensis Sauces Fermented with Lactic Acid Bacteria: Fermentation Properties, Flavor Profile, and Evaluation of Antioxidant Capacity in Vitro. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 810460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, R.A. Waste Valorization in a Sustainable Bio-Based Economy: The Road to Carbon Neutrality. Chem. Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202402207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).