Abstract

To meet the growing demand for higher storage capacities, bit-patterned magnetic recording (BPMR) has emerged as a leading solution for achieving ultra-high user densities (UDs). However, BPMR systems are significantly impacted by two-dimensional (2D) interferences, specifically inter-symbol interference (ISI) and inter-track interference (ITI), which can degrade the quality of the readback signal. This paper introduces a rate-4/5 constructive ITI (CITI) modulation scheme, combined with a Tabu search (TS)-based error correction algorithm, to address the limitations of conventional CITI modulation codes. In the original encoding scheme, some codewords still contain forbidden patterns within their borders. The TS algorithm enhances the performance of the outermost tracks by refining unreliable bits identified through a distance-based reliability metric, which differs from earlier TS-based detectors that were directly used for multi-track detection. A proposed soft-information adjuster is then used to correct the poor reliability of soft information, resulting in improved soft-information reliability and decoding performance. A modified TS detector is also proposed, where the single-bit criterion for selecting the number of input bits is adopted, to improve neighbor selection and better align with the signal characteristics of the inner tracks. Simulation results show that the proposed system can achieve up to 2.7 dB and 4.0 dB improvements in bit error rate (BER) at a user density (UD) of 2.4 Terabits per square inch, compared to conventional uncoded and coded systems, respectively, while also reducing computational complexity. Furthermore, the results also imply that when the recording systems must operate under fluctuations in the size and position of the bit-island, our proposed system can provide superior performance.

1. Introduction

As the demand for high-capacity data storage continues to rise, the hard disk drive (HDD) remains the primary storage device, using magnetic disks to record data. However, HDDs are approaching the limits of data storage density that can be achieved by reading and writing single tracks on traditional magnetic disks. Researchers around the world are continually proposing alternative magnetic recording technologies, which present new challenges in the field. For instance, two-dimensional magnetic recording (TDMR) [1,2,3], where the granular media is used in the same way as in current technology, but the corner writer is used to obtain narrower written tracks [4]. Therefore, with the narrower tracks, signal processing must be performed in two dimensions, along-track and across-track. Moreover, to achieve higher recording areal densities (ADs), a new granular media material has been developed to address the thermal instability of very small magnetic grains. This material is then used in heated-dot magnetic recording (HDMR) technology [5,6,7]. HAMR has been widely touted as a leading candidate for enabling the next generation of ultrahigh-density data storage [5], where the writer must operate in conjunction with a laser to rapidly change a material property during the writing process. However, the severity of transition noise reduces the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) [8,9], implying that, from a signal-processing perspective, increasing AD becomes more challenging. Note that the list of acronyms that are used in the paper is provided in Table A1.

Therefore, bit-patterned media recording (BPMR) has also emerged as a promising technology capable of achieving ultra-high ADs [10,11,12,13,14], where the severity of transition noise was effectively suppressed using patterned isolated magnetic islands, each island representing a single bit of data. This advancement allows it to surpass the limitations of conventional magnetic recording methods. However, BPMR systems encounter significant challenges due to two-dimensional (2D) interferences, specifically inter-symbol interference (ISI) and inter-track interference (ITI), which increase significantly as the distances between bit islands are reduced. These interferences can severely destroy the quality of the readback signal and degrade the overall performance of the systems, particularly in high-density recording environments.

To address the effect of interferences in BPMR systems, various techniques have been proposed, both describable and indescribable algorithms. Indescribable algorithms, such as deep learning-based detectors, are common schemes currently applied to handle interference effects in BPMR systems [15,16], revealing that they can provide higher performance than traditional detectors based on the partial response maximum likelihood (PRML) method. However, to assess the capabilities of describable algorithms, this work further develops signal processing capabilities based on the PRML method. For instance, Koonkarnkhai et al. introduced an ITI subtraction technique specifically for a coded dual-track dual-head BPMR system [17]. This method leverages soft information from adjacent tracks to estimate the ITI component, which is then subtracted from the corresponding readback signal. This approach results in improved performance compared to traditional methods. Warisarn et al. developed a soft-information decision decoding scheme based on the rate-4/5 constructive ITI (CITI) modulation code [18], specifically designed to mitigate ITI in BPMR systems. Their technique disallows harmful data patterns, such as [+1, −1, +1] and [−1, +1, −1], in the across-track direction. They iteratively decode log-likelihood information from a low-density parity-check (LDPC) decoder and feed it back into a 2D soft-output Viterbi algorithm (SOVA) detector [19], resulting in enhanced detection performance. However, previous proposed encoding methods have limitations, where the edges of the codewords still contain forbidden data patterns, which results in poor performance for the outermost tracks compared to the inner tracks. Addressing this issue is essential to achieving better overall BER performance.

Moreover, a simplified multi-track detection scheme that uses a priori information for BPMR has been proposed [20]. This detection approach utilizes a simplified trellis diagram and employs a priori information to detect the main track data in both along-track and cross-track directions. However, this simplified technique experiences significant performance degradation in high-density BPMR channels due to the low reliability of the side tracks. To address this issue, a Tabu search (TS) aided multi-track detection scheme has been introduced [21]. In this scheme, the TS detector was employed to enhance the reliability of the unreliable bits in the side tracks before supplying the improved soft information to the simplified multi-track detector. This approach can significantly improve BER performance, particularly in situations with severe ITI and media noise. However, to improve the BER performance of the desired track, the TS detector can be directly adopted to operate the readback signal of the desired track. Moreover, the computational complexity of finding the distance metric between all candidate solution vectors can also be reduced using single-bit criteria instead of the full-bit criteria.

The TS algorithm, which draws on concepts from artificial intelligence, is designed to find optimal or near-optimal solutions to complex problems involving multiple variables and constraints [22,23,24,25], making TS a vital tool for obtaining efficient solutions across various fields. The methodology of TS consists of exploring the solution space using strategies that progressively identify the best options, taking both past and future outcomes into account. This approach helps to avoid revisiting previously selected, suboptimal solutions. As a metaheuristic optimization algorithm, TS is developed to tackle complex combinatorial problems by intelligently navigating the solution space and avoiding local optima. The process starts with an initial solution, and the algorithm iteratively examines neighboring solutions to identify potential improvements [25]. A key aspect of TS is the use of a “Tabu list,” which functions as a short-term memory that keeps track of recent moves or solutions, which helps to prevent the algorithm from cycling back to them. TS is a flexible and adaptive method, often used in conjunction with other techniques to improve performance. It is particularly effective for problems with large, discrete solution spaces, where traditional local search methods frequently become stuck in local optima.

To address the limitations of the rate 4/5 CITI modulation code caused by the border effect, this paper presents a technique for adjusting soft information based on the TS detector. The outermost tracks in the coded system can effectively enhance their performances by using the unreliable bit correction provided by the TS detector. Initially, we applied the TS detector to the first and fifth tracks, where forbidden patterns still exist. Next, we conducted a reliability testing process to identify unreliable bits with precision, which were then corrected using the TS detector. The enhanced reliable bits are subsequently used to adjust the soft information generated by the 2D-SOVA detectors. Simulation results indicate that the proposed system can achieve a BER of approximately 10−5 with a gain of about 4 dB at an UD of 2.4 Terabits per square inch (Tb/in2) compared to conventional uncoded and coded systems, while also reducing computational complexity.

Below, we summarize the main contributions of this paper:

- -

- We first introduce an improved rate-4/5 CITI modulation scheme that eliminates forbidden data patterns in conventional CITI codewords, strengthening ITI suppression in high-density BPMR systems, and point out the outer tracks’ weakness between each codeword of CITI modulation code.

- -

- We develop a distance-based reliability technique that identifies the unreliable bits along outer tracks, enabling selective refinement rather than full-vector processing.

- -

- We then propose a TS-based refinement algorithm that corrects unreliable bits using a modified single-bit criterion, thereby reducing computational complexity while improving solution consistency. In addition, we also present a soft-information adjuster that further enhances soft-information reliability, resulting in improved detection accuracy.

- -

- We present simulation results showing that the proposed system achieves improvements of up to 2.7 dB and 4.0 dB in BER compared to conventional uncoded and coded systems, respectively. This is accomplished while maintaining robustness against media noise and reducing computational load.

2. Channel Model

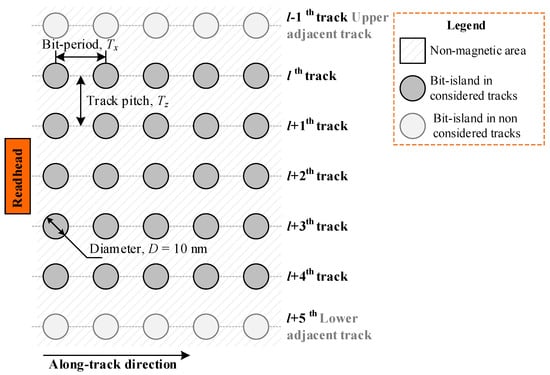

Figure 1 illustrates a graphical representation of the bit-patterned media, which comprises a magneto-resistive readhead and five primary data tracks, where rate-4/5 encoded data sequences are recorded. The readback signals can be retrieved from the data tracks using five readers, or a single reader reading each track in turn. The diameter of each bit island is D = 10 nm. The parameters Tx and Tz denote the bit-period and track pitch, respectively, with Tx = Tz = 16.5 nm and Tx = Tz = 14.5 nm corresponding to AD of 2.4 and 3.0 Tb/in2, respectively.

Figure 1.

The representation diagram of a BPMR medium.

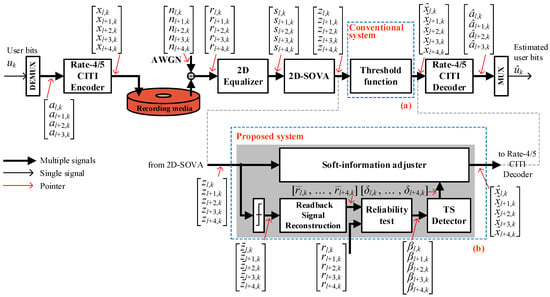

Figure 2 presents the block diagram of the BPMR channel model incorporating the proposed TS-based error correction scheme. The binary user bit sequence uk ∈ {±1} of size 1 × 4096 is divided into four sequences of size 4 × 1024, denoted as [al,k, al+1,k, …, al+3,k]. These sequences are encoded by the rate-4/5 CITI encoder, producing [xl,k, xl+1,k, …, xl+4,k] of size 5 × 1024, which are then recorded onto the medium, where l denotes the data track and k denotes the index of data. Note that we have defined l = 0 for all cases throughout this study.

Figure 2.

Block diagram of (a) the conventional BPMR system and (b) the additional TS detector that operates together with the soft-information adjuster.

The modulation code, as proposed in [18], is primarily designed to reduce ITI between adjacent encoded tracks, e.g., the lth to l+4th tracks, as shown in Figure 1, by eliminating the destructive data pattern in the across-track direction, e.g., [−1, +1, −1] and [+1, −1, +1]; however, interference from upper and lower adjacent tracks, e.g., l−1th and l+5th tracks, still remains. Note that the writing process in this research is assumed to be perfect writing, implying that the magnetization state of each bit-island always corresponds exactly to the bit being written.

The read/write channel is modeled using a micro-pixel magnetic framework, in which the recording medium is represented as a 2D matrix with magnetization values m(x,y) ∈ {0, ±1} at a spatial resolution of 0.25 × 0.25 nm2 per pixel. Here, +1 and −1 indicate upward and downward magnetic orientations, respectively, while 0 denotes a non-magnetic region. The readhead is characterized by a 2D reader sensitivity function [26], denoted by h(x,y), of size 257 × 257 pixels (64.25 × 64.25 nm2), spanning nearly five tracks when aligned with the currently read track centerline.

In the read process, the readback signal r(x,y), represented as a 2D matrix for each data track, is obtained through the 2D convolution of the medium magnetization and the reader sensitivity function, expressed as follows:

where m(x,y) is the medium magnetization and h(x,y) is the reader sensitivity function. Since we have to transform the readback signal into a 1D matrix form, the parameter y can then be defined as the lth track, while the parameter x can be defined as the time axis, t. Therefore, the continuous readback signal in the time domain, r(t), is then extracted from the following:

where l denotes the row of r(x,y) corresponding to the center of the reader sensitivity function, the continuous readback signals from the lth to l+4th tracks are sampled at the bit period Tx and corrupted by electronic noise [nl,k, nl+1,k, …, nl+4,k], modeled as additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN), to yield the discrete-time readback signals [rl,k, rl+1,k, …, rl+4,k]. It is important to note that we assume the readback signals can be retrieved using only one reader, reading five times from the first considered track to the last considered track.

During data detection, the discrete-time readback signals are first processed by 2D equalizers, producing the equalized sequences [sl,k, sl+1,k, …, sl+4,k], which are then passed to the 2D-SOVA detectors [19]. The 2D-SOVA generates the log-likelihood ratio (LLR) sequences [zl,k, zl+1,k, …, zl+4,k], here we call the soft-information, while excluding invalid data patterns that are not part of the rate-4/5 CITI modulation codewords, which consist of both [−1, +1, −1] and [+1, −1, +1] in the across-track direction, thereby preventing non-codeword detections. The 2D generalized partial-response target and the equalizer coefficients are designed using the minimum mean square error criterion [19,27].

Subsequently, the soft-information sequences are processed by a thresholding function to generate hard-detected sequences []. These sequences are then passed through the readback reconstruction process, which performs a 2D convolution between the hard-detected sequences and the read/write channel coefficients. A reliability test is applied to identify the unreliable bits index, denoted by [βl,k, βl+1,k, …, βl+4,k]. The TS detector refines the identified unreliable bits, and a soft-information adjustor uses the TS outputs to modify the original soft-information sequences. Finally, the refined soft-information sequences are decoded by the rate-4/5 CITI decoder, yielding the estimated user bits []. The integration of the TS algorithm with the reliability test process significantly improves the accuracy of bit detection. Further details of the soft-information adjustment process are presented in Section 3.

3. Proposed Methods

To address the limitations of the rate 4/5 CITI modulation code due to the border effect, this paper presents a technique for soft-information adjustment based on the TS detector. Two edges of the outermost tracks in the coded system can be corrected through the following processes, which are described as follows:

3.1. 4/5 Modulation Code

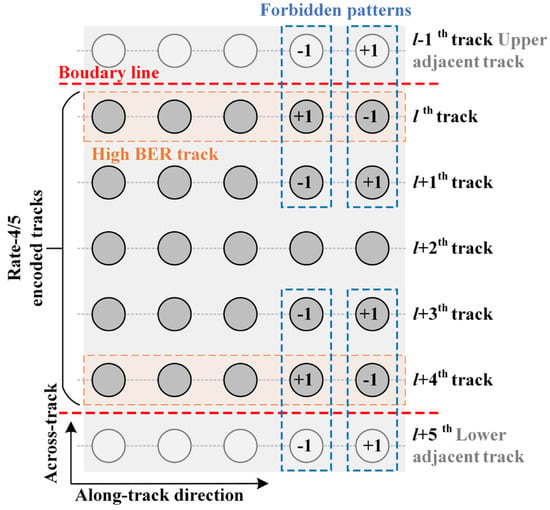

The rate-4/5 CITI modulation was proposed to address the severe ITI effects [18]. In this approach, two specific data patterns, namely [+1, −1, +1] and [−1, +1, −1] in the across-track direction, are prohibited from being recorded onto the medium because they result in significant ITI effects in ultra-high magnetic recording systems. During the encoding process, four user bits are mapped to five coded bits using a lookup table, resulting in each codeword consisting of five bits. For decoding, the Euclidean distance method or logic circuits are utilized. An example of the recorded bits on the medium is illustrated in Figure 3, where the three inner tracks do not encounter the forbidden patterns, so they can be processed using the modified 2D-SOVA detectors [28] that can offer significant improvements compared to the uncoded system. However, the boundaries of each codeword, such as the lth and l+4th tracks, still encounter these forbidden patterns. This situation impacts the decoder’s effectiveness and reduces the overall performance of the recording system. Therefore, signal processing techniques that can identify unreliable bits should be utilized in this coded system. Here, we propose using a TS detector to process the readback signals from both the first and fifth readers, so that they have to encounter both forbidden data patterns at border codewords.

Figure 3.

An example of the forbidden patterns occurring between the borders of the rate-4/5 CITI modulation code.

3.2. Tabu Search (TS) Detector

Tabu search (TS) is a metaheuristic optimization method designed to find approximate solutions for combinatorial problems. Both binary and real-valued versions of TS have been successfully applied in signal processing, including magnetic recording [20,21] and multi-user detection systems [25,29,30]. In this study, the TS algorithm is employed to identify and correct unreliable bits located near the borders of the rate-4/5 modulation codewords.

The approach applies a local neighborhood search strategy, supported by a Tabu list that records previously visited solution matrices to prevent cycling. Unreliable bits, denoted as , are identified according to their positions βl,k. Due to the wide read head footprint, approximately 15 surrounding bits, e.g., l ∈ {l − 1, l, l + 1} and k ∈ {k − 2, k − 1, k, k + 1, k + 2}, are affected. Consequently, an exhaustive search would require evaluating 215 = 32,768 candidate solutions, which is computationally prohibitive. To mitigate this complexity while preserving reliability, TS is employed to efficiently explore the solution space.

The reliability test plays a critical role in limiting the number of bits to be processed, thereby reducing computational overhead. The TS detector’s complexity is directly proportional to the number of unreliable bits. While increasing this number enhances correction capability, it also raises computational cost. Hence, the threshold parameter, ξ, must be carefully selected to strike a balance between performance and complexity. The distance metric defines the unreliable bits, which can be calculated from the following equation:

where is the actual readback signal, and is the reconstructed readback signal given by the following:

where h(m,n) denotes the 2D channel coefficients derived from a Gaussian pulse response [27], and representing the detected bits from the 2D-SOVA detector, a bit is classified as unreliable if its distance-based reliability metric exceeds a predefined threshold, ξ. Reducing ξ increases the number of bits labeled as untrustworthy, thereby enhancing reliability but also increasing computational complexity. Thus, an optimal balance between reliability and complexity must be established. In this study, the distance-based reliability metric can be obtained by selecting the appropriate distance difference between the readback signal and the reconstructed readback signal, while the predefined threshold can be determined by optimizing, as explained in the following section.

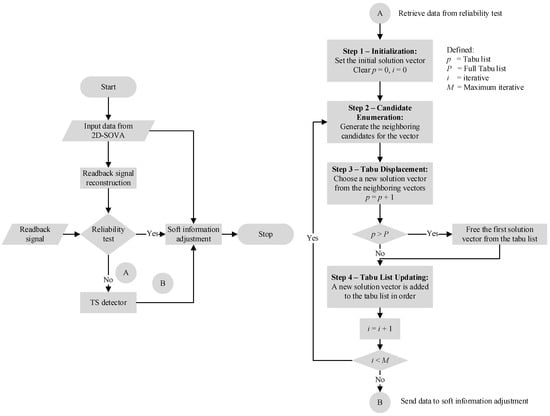

The operation of the TS detector can be summarized in four steps:

Step 1—Initialization: An initial solution matrix, , is constructed from the unreliable detected bits, . The Tabu list (TL) is initialized, and the maximum number of iterations M, Tabu list length P, and number of candidate solutions, J, are set. In this study, M = 20, P = 10, and J = 15. The iteration index, i, is initialized to zero. Since our main focus is on simplifying the TS detector rather than re-optimizing the parameters, we follow the TS parameters set by Kong and Jung [21]. Note that increasing the number of iterations beyond 20 does not significantly improve the TS detector’s performance.

Step 2—Candidate Enumeration: A neighborhood, , is generated by flipping one bit of at a time. For example, consider the initial 3 × 5 solution matrix = [1 1 1 1 1; 1 1 1 1 1; 1 1 1 1 1]. Based on the definition of the neighborhood, the fifteen candidate solution matrices consist of: = [−1 1 1 1 1; 1 1 1 1 1; 1 1 1 1 1], = [1 −1 1 1 1; 1 1 1 1 1; 1 1 1 1 1], …, and = [1 1 1 1 1; 1 1 1 1 1; 1 1 1 1 −1].

Step 3—Tabu Displacement: From the candidate solutions, the next solution matrix,, is selected as the one with the lowest distance metric, excluding those present in the Tabu list (unless aspiration criteria are met). The metric for each candidate, j, is calculated as:

where j = 1, 2, …, J, and the candidate solution matrices can be generated from:

The candidate with the minimum distance, min (), is chosen for the next iteration.

Furthermore, this work focuses specifically on correcting data with a single-bit alteration. Therefore, using the above full-bit criteria introduces unnecessary complexity. Since the objective is to fix only one bit of data, we propose a new method that is implemented within the Tabu displacement process. This approach considers only the middle bit and emphasizes the evaluation of its proximity. The distance metric calculation becomes:

This single-bit criterion not only improves the accuracy of the data correction process but also simplifies the procedure, thereby enhancing efficiency in correcting a single bit of data. As a result, we have utilized the proposed distance metric calculation in this study.

Step 4—Tabu List Updating: Once the candidate solution with the lowest distance metric is identified, it is then selected as the new current solution matrix and inserted into the Tabu list if it is not already present. This new solution then becomes the guide for the next iteration of the search process. The update ensures that previously visited suboptimal solutions are avoided by referring to the Tabu list. The iterative nature of this process ensures that the algorithm continually refines the solution space towards an optimal or near-optimal solution. When the Tabu list reaches its full capacity, P, the first solution matrix is removed to accommodate the new solution matrix, which is then added to the list. The order of operation for the TS detector is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The TS algorithm, where lines 11–12 are an additional unreliable bit selection step beyond the traditional TS detector.

3.3. Soft Information Adjustment

After processing the selected unreliable bits and enhancing them through reliability tests and TS detection, it is used in a subsequent procedure known as soft-information adjustment. This additional step is essential for improving the overall effectiveness of our proposed system. The data sequence generated from the TS detector, δl,k, which has the same position as the selected unreliable bits, . The proposed soft-information adjuster can operate by flipping the symbols of the output data sequence from the SOVA detector, zl,k, at the positions of selected unreliable bits according to the symbols of the data bits produced from the TS detector. The TS detector determines the most likely symbol for each unreliable bit based solely on bit decisions, rather than making direct modifications to the soft information. After the TS detector provides its estimated symbol, this symbol replaces the original unreliable symbol in the soft information. This replacement ensures that the unreliable bits are corrected using a more reliable symbol obtained through the TS process, while all other bits remain unchanged, which implies that there is only a symbol indicating an unreliable bit that was inverted, while its soft-information value remains unchanged from the original.

Therefore, the updated soft-information data sequence, , can be generated from:

where is the absolute operator, and is the symbol selection operator. This operation can ensure that the updated soft-information data sequence in the decoding process is highly reliable, as it has already been enhanced through reliability testing and TS detection. The improvement of soft-information data in the soft-information adjustment process is, therefore, a critical component in developing systems that provide more accurate results. To illustrate the research steps of our proposed systems, we can summarize them using a research flowchart, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

A research flowchart that consists of a reliability test, a TS detector, and soft information adjustment.

3.4. Computational Complexity

Since the improvement in BER performance of our proposed system increases computational complexity, in this section, we outline the additional complexity compared to conventional recording systems and those that utilize the traditional TS detector [21]. As we mentioned, the primary challenge with the TS algorithm is its high computational complexity, which has prompted the implementation of reliability tests to reduce the input size provided to the TS detector. However, the proposed single-bit criterion offers an additional reduction in its complexity.

A computational complexity analysis in terms of theoretical count for each iteration of the full-bit criteria [21] and single-bit criteria for selecting the input bit number of the TS detector is then considered. Here, the complexity is assessed through the use of subtraction, multiplication, addition, absolute value, and square root operators, as presented in Table 1. It is important to note that, to provide an implementation-independent assessment of algorithmic efficiency, experimental runtime performance is not considered due to its strong dependence on hardware and software platforms.

Table 1.

Computational complexity comparison between the full-bit criteria [21] and single-bit criteria for selecting the input bit number of the TS detector.

We also investigate the additional computational complexity incurred when our proposed system is employed and compare it to that of the conventional system. The extra blocks, which consist of readback signal reconstruction, reliability test, TS detector with full- and single-bit criteria, and soft information adjuster, are considered to have their computational complexities. In this work, the computational complexity is measured in terms of the total number of elementary arithmetic and logical operations required for processing one data sequence. These operations include subtraction, multiplication, addition, absolute value, square root, and sign operators, which are counted explicitly for each functional block, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Additional computational complexity comparison between the systems with and without our proposed forbidden data patterns correcting scheme.

For example, in the readback signal reconstruction block, each bit of the reconstructed sequence is obtained by a 2D convolution between the 3 × 3 channel coefficients and the corresponding 3 × 3 hard-detected bits, which requires 9 multiplications and 8 additions per bit. For a data sequence of 1024 bits, this results in 9216 multiplications and 8192 additions. In the reliability test block, each bit is evaluated using Equation (3), which consists of one subtraction, one multiplication, one absolute operation, and one square root operation per bit, leading to 1024 operations for each corresponding operator.

For the TS detector, the computational complexity depends on the number of candidate solutions J, the size of the solution matrix (m × n), the length of the Tabu list P, and the maximum number of iterations M. In this study, J = 15, m × n = 3 × 5, P = 10, and M = 20; therefore, the distance metric is evaluated M × J = 300 times per detection process.

For the full-bit distance metric in Equation (5), each evaluation requires 15 subtractions, 14 additions, 15 multiplications, 15 absolute-value operations, and one square root operation, together with 14 additional comparison operations in the min(−) function, which are counted as subtraction operations. For the proposed single-bit criterion in Equation (7), each metric evaluation requires only one subtraction, one addition, one multiplication, one absolute-value operation, and one square root operation, together with the same min(−) comparison. Note that, in Table 2, the computational complexity reported in the TS detector column already includes the operation counts associated with the generation of the solution matrices, and the candidate solution matrices, , which contribute additional multiplication and addition operations. By accumulating all these operation counts over i iterations (refer to Figure 4) and scaling by the number of unreliable bits b, the total computational complexity of the TS detector reported in Table 2 is obtained.

4. Simulation Results

In this section, we evaluate the BER performances of (a) the conventional BPMR system without coding scheme—represented with “Conv-BPMR,” (b) the coded BPMR system that employed the rate-4/5 CITI modulation code—represented with “Code-BPMR,” and (c) the coded BPMR system that employed the rate-4/5 CITI modulation code together with the TS detector for enhancing the performance of both its outer tracks—represented with “Code-BPMR-TS.” Additionally, we evaluate the performance of coded BPMR systems when the full- and single-bit criteria are applied to find the distance metric in reliability testing of the TS detector, which are represented as “Code-BPMR-TS w full-bit” and “Code-BPMR-TS w sing-bit,” respectively. To make a fair comparison, it is essential to note that these considered systems must be evaluated for their performance under the same UD or different ADs. In this study, we have considered the UD at 2.4 Tb/in2, which means that the uncoded system has an AD of 2.4 Tb/in2. In contrast, the coded system should be recorded at an AD of 3 Tb/in2, where UD = R × AD, and R = 0.8 is the code rate.

Since we have focused on using the TS detector to enhance the performance of the two outer tracks of the rate 4/5 CITI modulation-coded system, the computational complexity increases with the number of input bits to the TS detector. Therefore, it is essential to investigate the optimal number of input bits to maximize the TS detector’s efficiency while minimizing computational complexity. To achieve this, we first examine a specific value, ξ, that measures the distance between the readback signal and the reconstructed readback signal. We conducted this analysis with an SNR of 8 dB, using 1024 considered samples. Here, we defined the SNR as follows in decibels (dB):

where σ is the standard deviation of AWGN.

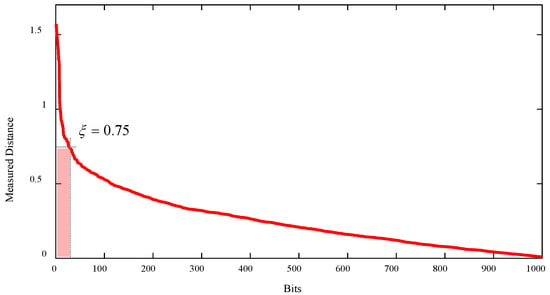

The distances are then arranged from highest to lowest. Our findings indicate that the distance decreases exponentially until it reaches approximately 0.75, after which the trend becomes more linear, as illustrated in Figure 6. This trend provides guidance for selecting the appropriate number of input bits for the TS detector. Specifically, we recommend considering any input bits that produce a distance of 0.75 or higher as unreliable and subjecting them to further refinement by the TS detector. This strategy focuses on correcting only the most unreliable bits, effectively balancing performance improvements with computational efficiency. For the TS detector in this study, the number of input bits should be fewer than 50 bits, as illustrated in Figure 6. Therefore, we will set the specific value ξ equal to 0.75 throughout our study.

Figure 6.

The distance between the readback signal and the reconstructed readback signal, which can be used for selecting the specific value, ξ, to specify the number of input bits of the TS detector.

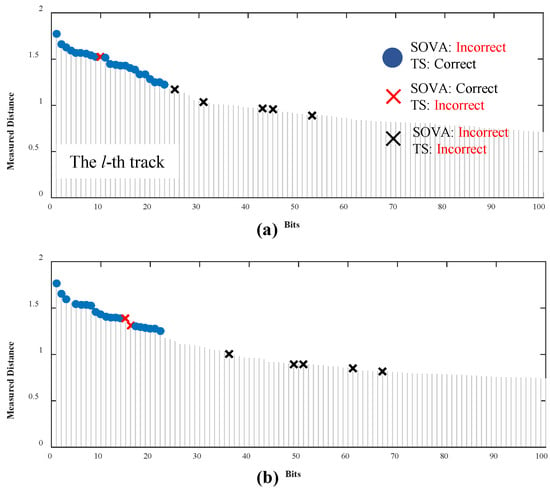

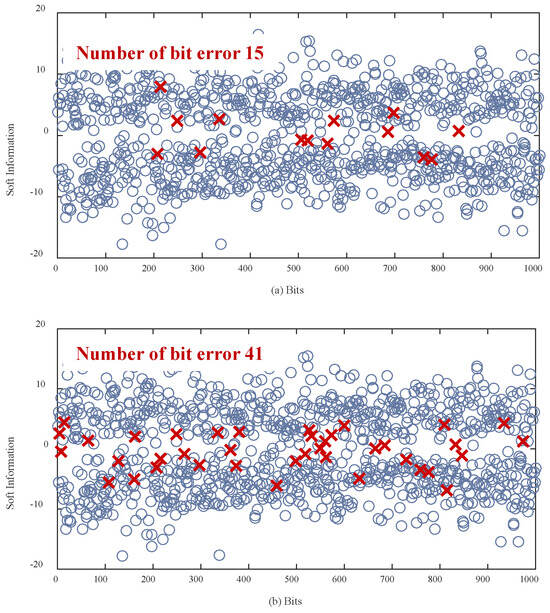

To validate our proposed hypothesis, we also conducted experiments that categorized the erroneous bits into three distinct cases: 1. Cases where the TS detector successfully corrected the erroneous bits compared with the SOVA detector’s output (represented by blue dots). 2. Cases where the TS detector failed to correct the erroneous bits (represented by black crosses). 3. Cases where the TS detector changed originally correct bits into incorrect ones (represented by red crosses). As illustrated in Figure 7, at an SNR of 5 dB, the TS detector significantly improves the accuracy of bits located in the lth and l+4th tracks, especially in areas with high distance values, even in the presence of high electronic noise, as shown in Figure 7a and Figure 7b, respectively. Although the TS detector made an incorrect decision, where the correct bits were changed to incorrect bits, many incorrect bits can be corrected with the TS detector. This result confirms that the defined threshold range for bit selection not only yields an appropriate selection but also enhances performance with the TS detector.

Figure 7.

The capability for correcting the unreliable bits of the TS detector depended on the input bit number over the conventional 2D-SOVA detectors for (a) the lth and (b) l+4th tracks at an SNR of 5 dB.

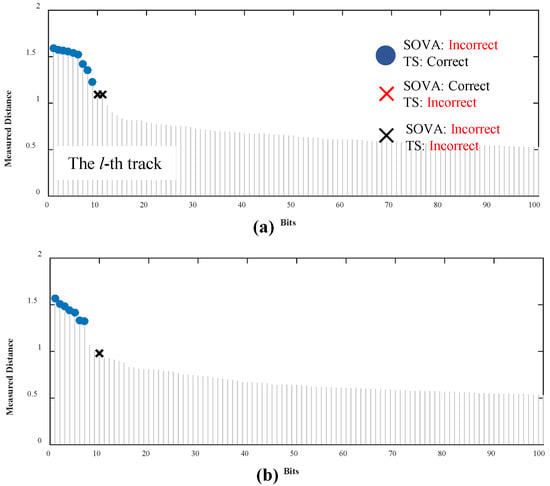

A similar trend was observed at an SNR of 8 dB, as illustrated in Figure 8. The conventional 2D-SOVA detector provided incorrect bits; however, using the TS detector together with our proposed soft-information adjuster can correct nearly all unreliable bits that the 2D-SOVA detector cannot handle for the lth and l+4th tracks, as shown in Figure 8a and Figure 8b, respectively. The results also indicate that the number of input bits should be fewer than 20. Both the 2D-SOVA detector and the TS detector struggle to operate correctly when the measured distance is below approximately 1.2, as indicated by the black cross symbol.

Figure 8.

The capability for correcting the unreliable bits of the TS detector depended on the input bit number over the conventional 2D-SOVA detectors for (a) the lth and (b) l+4th tracks at an SNR of 8 dB.

We realize that media noise is a significant factor that impacts the efficiency of BPMR systems. To address this, therefore, we evaluated the performance of our proposed system under the influence of media noise, which included fluctuations in both position and size, at a 5% level. The percentage of position fluctuation is determined based on the maximum possible distance between the center of the bit island and the center of the ideal target island, following a Gaussian distribution, while the percentage of size fluctuation is determined based on the maximum possible width of the island size compared to the ideal island size, which also follows a Gaussian distribution.

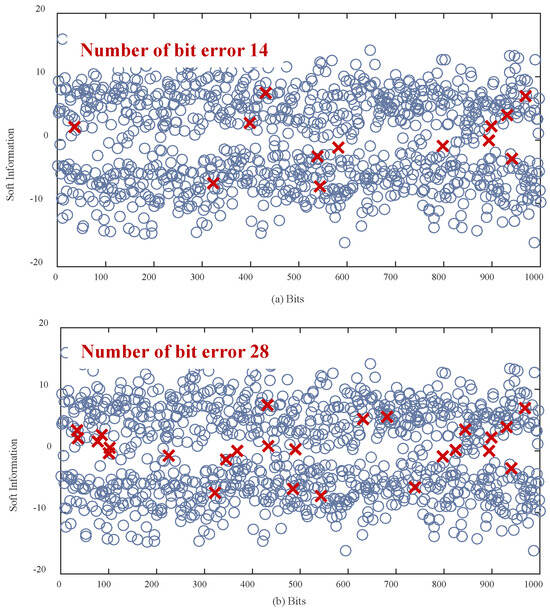

We assessed the system’s ability to correct erroneous bits, as demonstrated by the distributions of soft information. As shown in Figure 9, our proposed technique results in fewer erroneous bits compared to conventional recording methods. Specifically, when media noise is disregarded, our system produces only 14 erroneous bits, whereas the conventional system generates 28 erroneous bits, as depicted in Figure 9a,b, respectively.

Figure 9.

Soft-information distributions (a) with and (b) without using the soft-information adjuster, together with the TS detector under 0% media noise.

Moreover, when media noise is taken into account, as shown in Figure 10, the number of erroneous bits increases to 15 for our proposed system and 41 for the conventional system, as shown in Figure 10a and Figure 10b, respectively. These results confirm that our soft-information adjuster, in conjunction with the TS detector, effectively minimizes the number of incorrect bits. The results also imply that our proposed system is resilient to noise in the media. Furthermore, the enhanced soft information provided by the soft-information adjuster leads to more accurate decisions during the decoding process, which will be further discussed in terms of BER performance.

Figure 10.

Soft-information distributions (a) with and (b) without using the soft-information adjuster, together with the TS detector under 5% media noise.

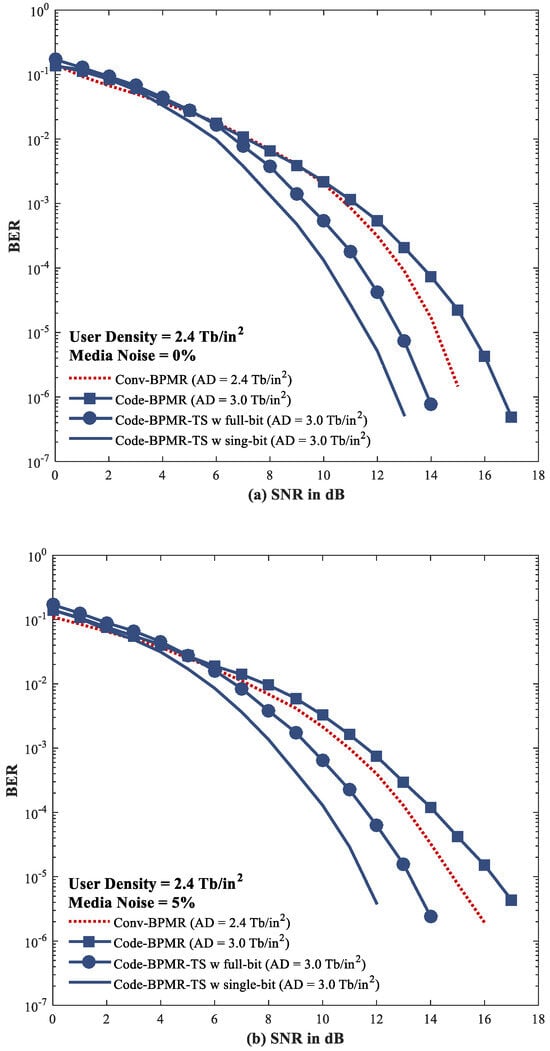

We then compared the BER performance in various recording systems at a UD of 2.4 Tb/in2, which were conducted without media noise and with 5% media noise interruptions, as shown in Figure 11. Here, BER performance is evaluated by comparing actual user bits to estimated user bits. The conventional coded system struggles to achieve good BER performance due to the presence of forbidden patterns at its borders, as shown in Figure 11a. The outermost tracks perform significantly worse compared to the three inner tracks. This poor performance directly affects the decoding process, which is why it is recommended to use this modulation code in conjunction with various ITI suppression or logic circuit decoding schemes [31].

Figure 11.

BER performance comparisons of various recording systems at a UD of 2.4 Tb/in2, which were conducted (a) without media noise and (b) with 5% media noise interruptions.

Furthermore, the conventional recording system demonstrates better BER performance than the coded system because it was evaluated at a lower UD, which resulted in lower ITI and ISI impacts. Nevertheless, the conventional system still underperformed compared to our proposed systems. Our proposed system, which employs the full-bit criterion for detecting unreliable bits, provides an estimated improvement of approximately 1.4 dB over the conventional uncoded system at a BER of 10−5. Additionally, when using the single-bit criterion instead of the full-bit criterion, we observed that the SNR could increase by more than 2.7 dB and 4.0 dB compared to the conventional uncoded and coded systems, respectively. It is essential to note that the full-bit criterion represents the system proposed by Kong and Jung [21], which was also adopted to overcome the limitations of conventional CITI modulation codes.

As mentioned earlier, media noise, along with fluctuations in position and size, significantly impacts the efficiency of BPMR systems. Therefore, we have assessed the recording systems under the influence of 5% media noise. As illustrated in Figure 11b, the simulation results clearly demonstrate that our proposed system delivers the best BER performance compared to both conventional coded and uncoded recording systems at the same UD of 2.4 Tb/in2. The proposed TS detector, utilizing one-bit and full-bit criteria for selecting unreliable bits, can achieve SNRs of approximately 1.7 dB and 3.2 dB over the conventional uncoded recording system, respectively. Moreover, our proposed systems, designed to address the edge effects of the 4/5 CITI modulation code, also exhibit better BER performance than conventional coded systems. Specifically, they can achieve SNRs of more than 3.3 dB and 4.8 dB using the single-bit and full-bit criteria for selecting unreliable bits, respectively.

Furthermore, we observe that SNR gains can be achieved when analyzing the recording system under media noise, compared to cases where media noise was neglected in prior investigations. This indicates that our proposed systems are robust against the effects of media noise. For instance, our proposed system shows a slight difference in BER performance when the media noise is set to 0% and 5%. There is only a 0.1 dB difference at a BER of 10−5. In a conventional uncoded system, there is approximately a 0.6 dB difference at a BER = 10−5. These findings suggest that our proposed systems offer promising solutions for future high-density magnetic recording technologies.

5. Conclusions

This paper examines the application of the Tabu search (TS) algorithm to enhance the bit-error rate (BER) performance of coded bit-patterned media recording systems, particularly in high-density environments affected by two-dimensional interference that includes intersymbol interference, intertrack interference (ITI), and media noise. Additionally, we identify the border of constructive ITI (CITI) 4/5 modulation code, which still contains forbidden patterns, as unreliable bits. Our proposed reliability-based input number selection techniques allow for the identification of these unreliable bits, which are then corrected using the TS detector. We establish a specific distance between the readback and reconstructed readback signals to balance error correction performance with computational complexity. We subsequently enhance the soft information generated by a two-dimensional soft-output Viterbi detector using our proposed soft-information adjustment method. This improvement replaces the symbol of a new reliable bit with the old soft information, resulting in enhanced soft information. Simulation results demonstrate that the incorporation of TS-based detectors and the soft-information adjuster significantly corrects errors caused by forbidden patterns and improves the BER performance. The proposed system achieves a signal-to-noise ratio improvement of up to 4 dB compared to the conventional coded system at a BER of 10−5, which implies that our proposed system not only protects the ITI effect but also corrects it effectively. Our single-bit criteria for selecting the number of input bits for the TS detector provide a favorable trade-off between performance and complexity. Furthermore, the results also indicate that our proposed systems are robust against the effects of media noise. These findings suggest that our proposed method is a promising solution for future high-density magnetic recording systems. We want to point out that, in future work, the TS detector may be modified to be integrated with the decoding process, enabling it to operate as an iterative system and thereby increasing overall recording performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M., C.W. and K.K.; methodology, M.M., K.K. and C.W.; software, M.M., K.K. and C.W.; validation, C.W., J.L. and K.K.; formal analysis, C.W. and K.K.; investigation, J.L. and C.W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M., C.W., J.L. and K.K.; writing—review and editing, M.M., C.W. and K.K.; supervision, J.L. and C.W.; project administration, C.W.; funding acquisition, M.M. and C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the School of Integrated Innovation Technology (SIITec) and King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology, Ladkrabang (KMITL) under grant number KREF026705.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of acronyms that are used in the paper.

Table A1.

List of acronyms that are used in the paper.

| Acronyms | Full Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AD | Areal Density | Total bits per unit area, referred to as Terabits per square inch. |

| BER | Bit-Error Rate | The number of error bits per total number of considered bits. |

| BPMR | Bit-Patterned Magnetic Recording | One promising future hard disk drive technology involves data recording on magnetic islands instead of the current granular media. The media noise can be effectively reduced using this pre-pattern bit island, resulting in ultra-high areal density. |

| HDD | Hard Disk Drive | An electromechanical data storage device that stores and retrieves digital data using magnetic storage with one or more rigid, rapidly rotating platters coated with magnetic material. |

| ISI | Inter-Symbol Interference | The interference effect on a desired bit caused by adjacent bits is known as a symbol. This is one of the main problems in communication systems. |

| ITI | Inter-Track Interference | The interference effect on a desired recording track, which is caused by adjacent tracks in a magnetic recording system. The effect intensifies as the areal density increases. |

| AWGN | Additive White Gaussian Noise | A basic noise model used in communication and signal-processing systems. |

| SOVA | Soft-output Viterbi Algorithm | A detector that was developed from a Viterbi algorithm (VA), which can not only take in soft quantized samples but also provide soft outputs by estimating the reliability of the individual symbol decisions. |

| TS | Tabu Search | A metaheuristic optimization algorithm designed to find the best solution in complex problems. It works by exploring different possible solutions and uses a tabu list (a short-term memory) to avoid going back to recently visited solutions. |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio | A scientific and engineering measure comparing a desired signal’s level to background noise, expressed in decibels (dB). |

References

- Wood, R. The feasible of magnetic recording at 1 terabit per square inch. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2000, 36, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R.; Williams, M.; Kavcic, A.; Miles, J. The feasibility of magnetic recording at 10 terabits per square inch on conventional media. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2009, 45, 917–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiroishi, Y.; Fukuda, K.; Tagawa, I.; Iwasaki, H.; Takenoiri, S.; Tanaka, H. Future options for HDD storage. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2009, 45, 3816–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, S.; Kanai, Y.; Muraoka, H. Shingled recording for 2–3 Tbit/in2. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2009, 45, 3823–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roddick, E.; Kief, M.; Takeo, A. A new Advanced Storage Research Consortium HDD Technology Roadmap. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 33rd Magnetic Recording Conference (TMRC), Milpitas, CA, USA, 29–31 August 2022; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryder, M.H.; Gage, E.C.; McDaniel, T.W.; Challener, W.A.; Rottmayer, R.E.; Ju, G. Heat assisted magnetic recording. Proc. IEEE 2008, 96, 1810–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natekar, N.A.; Jubert, P.-O.; Olson, T.; Goncharov, A.; Brockie, R.; Tanahashi, K. HAMR performance impact from in-plane grains variation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 35th Magnetic Recording Conference (TMRC), Berkeley, CA, USA, 5–7 August 2024; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J. Signal-to-noise ratio definition for magnetic recording channels with transition noise. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2000, 36, 3881–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-G.; Li, H. SNR impact of noise by different origins in FePt-L10 HAMR media. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2015, 51, 3200407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.L.; Newt, R.M.H.; Pease, R.F.W. Patterned media: A viable route to 50 Gbit/in2 and up for magnetic recording? IEEE Trans. Magn. 1997, 33, 990–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C. Patterned magnetic recording media. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2001, 31, 203–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, T.R.; Bedau, D.; Dobisz, E.; Gao, H.; Grobis, M.; Hellwig, O. Bit patterned media at 1 Tdot/in2 and beyond. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2013, 49, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikitsu, A.; Maeda, T.; Hieda, H.; Yamamoto, R.; Kihara, N.; Kamata, Y. 5 Tdots/in2 bit patterned media fabricated by a directed self-assembly mask. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2013, 49, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, T.R.; Arora, H.; Ayanoor-Vitikkate, V.; Beaujour, J.-M.; Bedau, D.; Berman, D. Bit-patterned magnetic recording: Theory, media fabrication, and recording performance. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2015, 51, 0800342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Lee, J. Soft-output detector using multi-layer perceptron for bit-patterned media recording. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueangnetr, N.; Koonkarnkhai, S.; Kovintavewat, P.; Greaves, S.J.; Warisarn, C. Enhancing log-likelihood ratios with mutual information on three-reader one-track detection in staggered BPMR systems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonkarnkhai, S.; Warisarn, C.; Kovintavewat, P. A novel ITI suppression technique for coded dual-track dual-head bit-patterned magnetic recording systems. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 153077–153086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrayangkool, A.; Warisarn, C.; Kovintavewat, P. A constructive inter-track interference coding scheme for bit-patterned media recording system. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 115, 17B703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakulak, S.; Siegel, P.H.; Wolf, J.K.; Bertram, H.N. Joint-track equalization and detection for bit patterned media recording. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2010, 46, 3639–3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, G.; Choi, S. Simplified multi-track detection schemes using a priori information for bit patterned media recording. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 111, 07B920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, G.; Jung, M. Tabu search aided multi-track detection scheme for bit-patterned media recording. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, F. Tabu Search—Part I. ORSA J. Comput. 1989, 1, 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, F. Tabu Search—Part II. ORSA J. Comput. 1990, 2, 4–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, F. Artificial intelligence, heuristic frameworks and Tabu search. Manag. Decis. Econ. 1990, 11, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Long, H.; Wang, W. Tabu search detection for MIMO systems. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE 18th International Symposium on Personal, Indoor and Mobile Radio Communications, Athens, Greece, 3–7 September 2007; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, M.; Osawa, H.; Okamoto, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Miura, K. Read/write channel modeling and two-dimensional neural network equalization for two-dimensional magnetic recording. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2011, 47, 3558–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabavi, S.; Kumar, B.V.K.V. Two-dimensional generalized partial response equalizer for bit-patterned media. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Professional Communication Conference, Glasgow, UK, 1–3 October 2007; pp. 6249–6254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokjabok, S.; Koonkarnkhai, S.; Lee, J.; Warisarn, C. An improvement of BER using two-dimensional constrained code for array-reader-based magnetic recording. Int. J. Electron. Commun. (AEÜ) 2021, 134, 153678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinidhi, N.; Datta, T.; Chockalingam, A.; Rajan, B.S. Layered Tabu search algorithm for large-MIMO detection and a lower bound on ML performance. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2011, 59, 2955–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ming, D. Multi-user detection based on tabu simulated annealing genetic algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2012 Second International Conference on Instrumentation, Measurement, Computer, Communication and Control, Harbin, China, 8–10 December 2012; pp. 948–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pituso, K.; Warisarn, C.; Tongsomporn, D.; Kovintavewat, P. An intertrack interference subtraction scheme for a rate-4/5 modulation code for two-dimensional magnetic recording. IEEE Magn. Lett. 2016, 7, 4504705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).