Featured Application

This study presents a microextraction method for selected synthetic hallucinogenic compounds developed in accordance with the principles of green, sustainable, and white chemistry. The method minimizes the use of toxic organic solvents, reduces the overall environmental footprint, and enhances laboratory safety. By employing hydrophobic natural deep eutectic solvents (NADESs), the approach enables efficient extraction from polar biological matrices, including urine, making it suitable for both clinical and forensic toxicology. It is also applicable to wastewater analysis for monitoring population-level consumption of novel psychoactive substances (NPS), thereby supporting public health surveillance. The proposed extraction procedure is simple, rapid, and cost-effective, and is well-suited for routine implementation in analytical laboratories.

Abstract

The application of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles in method development aims to reduce waste and replace hazardous solvents with environmentally friendly alternatives. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADESs) have recently emerged as sustainable replacements for traditional organic solvents. In this study, hydrophobic NADESs were used in dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction (DLLME) to extract four synthetic hallucinogenic phenethylamines (2C-B, 25B-NBOMe, 25C-NBOMe, and 25I-NBOMe) in urine samples. Nine NADESs were formed using menthol and different organic acids, with menthol–decanoic acid (1:1 molar ratio) providing the best extraction efficiency. A fractional factorial design identified pH, vortex speed, and vortex time as key factors, which were then optimized using a Box–Behnken design. The statistical model showed strong validity and high predictive power, and the optimal conditions (pH 12, vortex time 20 s, vortex speed 30,000 rpm, centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 3 min) resulted in the highest recoveries. Greenness and operational sustainability, evaluated using ComplexGAPI, AGREEprep, BAGI, and SPRS tools, revealed clear advantages over existing extraction approaches. Overall, the proposed method represents a sustainable, white-chemistry–driven microextraction strategy suitable for clinical and forensic toxicological applications.

1. Introduction

Growing awareness of the environmental and occupational health hazards associated with conventional analytical methods has catalyzed a shift toward more sustainable practices in chemistry. Green Chemistry (GC), originally proposed by Anastas and Warner [1], emphasizes designing processes that minimize hazardous waste, reduce solvent use, and improve energy efficiency. Within this conceptual framework, Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) focuses on developing eco-friendly analytical methods that maintain and enhance performance while minimizing environmental burdens. Expanding upon these principles, the concept of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) incorporates ethical, economic, and social dimensions to promote practices that remain sustainable, safe, and responsible across the entire analytical lifecycle [2,3]. More recently, these principles have been adapted in toxicology through the emergence of Green Analytical Toxicology (GAT), which advocates the use of safer reagents, miniaturized extraction techniques, reduced solvent volumes, and energy-efficient workflows—without compromising sensitivity, selectivity, or reliability [4].

A key challenge in implementing GAC principles is replacing traditional organic solvents, such as acetonitrile, methanol, and dichloromethane, with safer and more sustainable alternatives [5,6]. Natural deep eutectic solvents (NADESs), formulated from naturally occurring components including organic acids, sugars, and terpenes, have emerged as promising candidates. They are biodegradable and exhibit low toxicity [7,8,9]. The high extraction efficiency of hydrophobic NADES arises from their highly structured hydrogen-bonding network, which generates a tunable microenvironment capable of simultaneously engaging in hydrophobic, van der Waals, and weak hydrogen-bonding interactions with target analytes. These synergistic interactions often provide superior solvation and partitioning behavior compared to conventional organic solvents. This tunability enables their application across diverse analytical tasks, including the extraction of pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and other emerging contaminants from biological and environmental samples. Importantly, the use of NADESs also reduces occupational exposure and risks and contributes to safer laboratory environments [10].

Alongside the development of green solvents, miniaturized sample preparation methods—especially dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction (DLLME)—have attracted significant interest. DLLME works by dispersing small volumes of extraction solvent into an aqueous sample, creating a fine, cloudy solution that facilitates rapid analyte transfer. The technique is straightforward, rapid, and uses minimal solvent, making it especially effective when combined with green solvents like NADESs [11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

Optimizing DLLME experimental parameters is essential for maximizing extraction efficiency and ensuring method robustness. Statistical approaches such as Response Surface Methodology (RSM) provide powerful tools for identifying significant factors, establishing predictive models, and refining extraction conditions while minimizing experimental effort [18,19]. These strategies are fully aligned with the principles of White Analytical Chemistry by promoting resource efficiency, data-driven decisions, and minimizing waste generation.

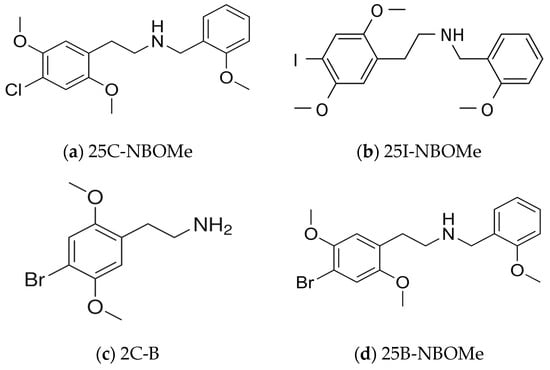

The toxicological relevance of this research lies in its application to the extraction of novel psychoactive substances (NPS), specifically phenethylamines of the 2C-X series, which are potent hallucinogens that act primarily as 5-HT2A receptor agonists (Figure 1). Owing to their exceptional potency, structural diversity, and the continuous emergence of new analogues, these compounds present a substantial analytical challenge and necessitate highly effective extraction methods [20,21].

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of selected phenethylamines: (a) 25C-NBOMe; (b) 25I-NBOMe; (c) 2-CB; (d) 25B-NBOMe.

Traditional analytical approaches for NPS determination typically rely on large volumes of toxic organic solvents and involve labor-intensive, time-consuming preparation steps, which conflict with GAC principles. To address this limitation, this study presents a novel NADES-based DLLME method as an innovative and sustainable alternative for extracting NPS from biological matrices. By integrating hydrophobic NADESs with miniaturized DLLME and systematic optimization through design of experiments (DoE), the present work aims to establish an extraction procedure that is efficient, environmentally responsible, and fully aligned with GAC, GAT, and White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) principles. This methodological framework advances ongoing efforts to replace hazardous laboratory procedures with effective, reliable, and sustainable solutions.

The developed NADES-based DLLME method for extracting hallucinogenic phenethylamines marks a significant step toward a truly GAT workflow. The method is simple, rapid, and cost-efficient, making it suitable for routine laboratory implementation. Additionally, its effectiveness with polar samples, especially urine, makes it a valuable tool for clinical and forensic toxicology. Beyond individual cases, this method can also be employed in wastewater-based epidemiology to monitor community-level use of NPS, thereby supporting broader public health efforts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Standard Solutions and Samples

Analytical standards of the selected hallucinogenic phenethylamines (2C-B, 25B-NBOMe, 25C-NBOMe, 25I-NBOMe) were obtained from Lipomed (purity >99%) through the Early Warning System on Novel Psychoactive Substances of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Stock solutions (1 mg mL−1) were prepared in methanol and stored at −20 °C. Working solutions were prepared by appropriate dilution before extraction. LC–MS-grade methanol was supplied by Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Menthol, decanoic, dodecanoic, formic, and acetic acids were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Ultrapure water was produced using a Pure Lab Ultra purification water system (ELGA, High Wycombe, UK). A blank urine sample was collected from a healthy volunteer who had not taken any prescription or illicit drugs for at least one month. The sample was stored at −20 °C until analysis.

2.2. Instrumentation and Apparatus

An ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatograph coupled to a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (UHPLC-MS/MS) (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) was used for the determination of phenethylamines. A pH meter (XS PH 50, XS Instruments, Capri, Italy), a vortex mixer (Classic Advance, Velp Scientifica, Usmate, Italy), a fixed-speed microcentrifuge (Model 5410, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), and an ultrasonic water bath (Sonic, Shenzen, China) were used for sample preparation and solution handling.

2.3. Preparation of NADESs

The NADESs were prepared from natural compounds by combining a hydrogen bond donor (HBD) with a hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA). Menthol was selected as the HBA terpenoid, while the following organic acids were used as HBDs: formic acid [22,23], acetic acid [24,25], decanoic acid [26], and dodecanoic acid [27,28]. The components were mixed in predefined molar ratios (1:1, 1:2, and 2:1) and heated at 50 °C in an ultrasonic water bath until a clear and homogeneous liquid was obtained [27]. All prepared NADESs were transferred into 10 mL airtight glass vials and stored at room temperature until use. Table 1 shows the composition of each NADES, including the selected components, their molar ratios, and the abbreviations used throughout the manuscript.

Table 1.

NADESs components and molar ratios.

2.4. Extraction Procedure

To evaluate the extraction performance of the different NADESs, blank urine samples were spiked with selected phenethylamines at a concentration of 100 ng mL−1. An aliquot of 1 mL of the spiked urine was transferred into a 1.5 mL polypropylene centrifuge tube. Subsequently, 200 μL of NADES was added, and the mixture was vortex-mixed at 24,000 rpm for 30 s until a cloudy solution was formed, including proper dispersion. Phase separation was achieved by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 5 min. The upper layer (100 μL) was carefully collected using a syringe, diluted with 100 μL of methanol, vortex-mixed, and filtered through a 0.2 μm PTFE syringe filter (Restek, Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, USA). A 1 μL aliquot of the final solution was injected into the UHPLC-MS/MS for analysis (Figure 2). Each extract was injected three times, and the mean peak area was used for calculation.

Figure 2.

Schematic workflow of the NADES-based DLLME extraction procedure.

2.5. Extraction Efficiency Calculations

Extraction efficiency was evaluated in terms of extraction recovery (R%). The recovery was calculated using the following equation.

- Cnades—final concentration of analyte in extract

- Vnades—volume of collected NADES phase

- Csample—initial concentration of analyte in the sample

- Vsample—sample volume

2.6. Optimization Strategy

The extraction of phenethylamines from urine was optimized following the principles of WAC [29,30]. Traditionally, optimizing extraction procedures has been laborious and resource-consuming because it relied on the one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approach. To address these issues, a DoE methodology was adopted [31]. Factorial designs allowed the simultaneous study of multiple variables and their interactions on process outcomes. However, as the number of factors increases, full factorial design quickly becomes impractical and expensive. Therefore, a fractional factorial design (FFD) was used as an initial screening tool [6]. A 25−1 (Resolution V) FFD assessed the effect of five Thank you. It is minus.DLLME-related factors, requiring only 16 experiments instead of 32, for a full factorial design, thus saving time and resources. Factors identified as statistically significant in the screening phase were further optimized using a Box–Behnken Design (BBD) within the RSM. BBD is more efficient than full-factorial or central composite designs when three levels per factor are needed, offering reliable, predictive models with fewer experiments. To find the global optimum, desirability functions were integrated into the RSM process, enabling multiple-response optimization and the selection of optimal experimental conditions [32].

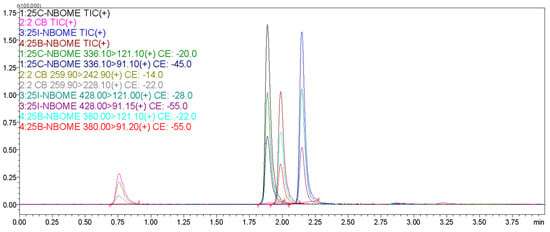

2.7. Chromatographic Conditions

Chromatographic analysis was performed using a Nexera 8030 UHPLC (Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with a dual-gradient pump, a thermostated autosampler, a column oven, and a tandem mass spectrometer. Separation was achieved on a Raptor Biphenyl (2.7 µm, 50 × 3.0 mm) HPLC Column (Restek, Bellefonte, PA, USA) with a C18 guard column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). The column temperature was maintained at 40 °C, and the flow rate was set to 0.3 mL min−1. The mobile phase consisted of (A) water containing 0.1% formic acid and (B) methanol containing 0.05% formic acid. Gradient elution was performed as follows: 0–2 min, 20–90% B; 2–3 min, 90% B (isocratic); 3–3.5 min, 90–20% B; followed by a 0.5 min re-equilibration step at 20% B. A representative chromatogram is presented in Figure A1.

2.8. Mass Spectrometer Parameters

Mass spectrometry was performed using electrospray ionization (ESI) in positive mode. Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions were optimized for each analyte. Instrumental parameters, including Nebulising Gas Flow, Desolvation Line Temperature, Heat block temperature, Drying Gas Flow, Dwell and Pause Time, are presented in Table A1. The optimized mass spectrometric conditions are shown in Table A2.

2.9. Software and Analytical Chemistry Metrics

Several software tools were employed throughout this study. Minitab 22.1.3 (Minitab LLC, USA) was used for the DoE, including the statistical analysis of the FFD and the BBD. LabSolutions 5.90 (Shimadzu, Japan) software was utilized for instrument control, data acquisition, and quantitative analysis of the UHPLC–MS/MS data. To assess the sustainability of the developed analytical procedure, four complementary tools were employed: ComplexGAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) [33], AGREEprep [34], BAGI (Blue Applicability Grade Index) [35], and SPRS (Sample Preparation Metric of Sustainability) [36]. Together, these tools provide a holistic assessment of the greenness, applicability, and sustainability of the method, in accordance with the principles of the WAC and GAT.

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Optimal NADES

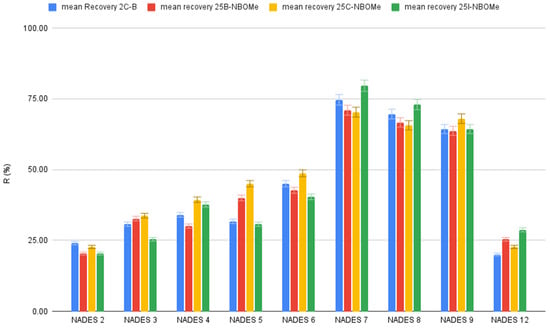

Twelve NADESs were prepared by combining menthol with four organic acids (formic, acetic, decanoic, and dodecanoic acid) at different molar ratios (1:1, 1:2, and 2:1). An efficient NADES extraction solvent must be liquid at room temperature, exhibit low density, be immiscible with water, and allow efficient dispersion during the DLLME process. All NADESs except menthol–formic acid (1:1) and menthol–dodecanoic acid (1:1 and 1:2) remained colorless liquids after cooling, indicating successful formation of the eutectic mixture. This behavior reflects appropriate component ratios as well as suitable heating conditions that promote hydrogen bond formation and a pronounced reduction in melting point. If the amount of HBD exceeded the HBA amount, even after prolonged shaking at high temperature, no NADES would form, and the mixture would remain heterogeneous [37]. Extraction Recovery values (Figure 3) demonstrated that the menthol–decanoic acid (NADES 7) achieved the highest extraction efficiency among all tested formulations. Error bars represent mean ± SD (n = 3).

Figure 3.

Extraction recovery (%) obtained for different tested NADES formulations.

3.2. Screening of Significant Parameters

An FFD with 16 experiments (25−1 Resolution V) was used to identify parameters that significantly affect extraction efficiency. All experiments were conducted randomly to reduce the influence of uncontrolled or systematic variability. Based on literature and preliminary trials, five factors were chosen for evaluation at two levels: NADES volume, salt amount, sample pH, dispersion method, and centrifugation time. The experimental factors and their low and high levels for the FFD are summarized in Table 2, while the full experimental matrix appears in Table A3.

Table 2.

Experimental parameters and levels for FFD.

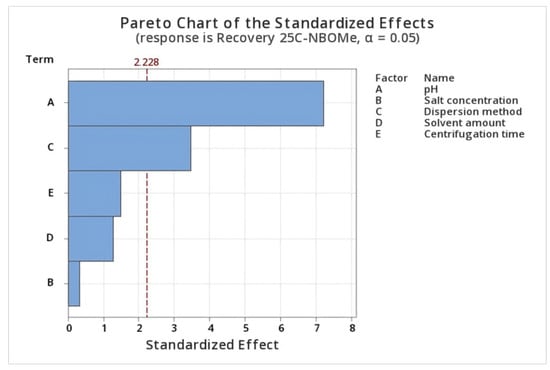

The half-normal, normal, and Pareto plots (Supplementary Materials, Figures S1 and S3) were used to identify and visualize the most influential factors affecting the extraction recovery in the factorial screening phase. The effects of the evaluated parameters on the recovery of 25C-NBOMe in the FFD are shown in Figure 4 as a Pareto chart. The bar length corresponds to the magnitude of each factor’s effect on extraction recovery, and bars extending beyond the reference line indicate statistically significant effects at the 95% confidence level. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed that sample pH was the most significant factor affecting extraction efficiency, followed by dispersion type (Supplementary Materials Table S1). Vortex-assisted dispersion resulted in noticeably higher recoveries, confirming its positive impact on NADES-based DLLME performance. As a result, these two factors (pH and dispersion method) were selected for further optimization using the BBD. In contrast, the amount of salt, centrifugation speed, and centrifugation time did not significantly influence extraction efficiency within the studied ranges. Therefore, these parameters were fixed at their low levels in subsequent experiments. The statistical insignificance of these variables suggests that the extraction method is robust regarding salt addition and centrifugation conditions. Additionally, setting centrifugation time to a low level helps reduce overall extraction time and improves method throughput.

Figure 4.

Standardized (p = 0.05) Pareto chart, representing the estimated effects of parameters on the Recovery value of 25C-NBOMe.

3.3. Optimization by the Box–Behnken Design

Based on the previous FFD results, the selected parameters were further investigated using RSM with a BBD to determine the optimal extraction conditions and evaluate factor interactions. A total of 15 experimental runs were performed in randomized order, with three factors at three levels and three replicates at the center point to estimate pure error and assess model adequacy. The selected factors and their ranges were as follows: sample pH (7–12), vortex time (20–60 s), and vortex speed (16,000–30,000 rpm). The BBD experimental matrix, along with the corresponding experimental responses, is presented in Table A4, while the coded and actual factor levels used in the BBD are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Experimental factors and coded levels used in the BBD.

By applying multiple regression analysis to the experimental data, a second-order polynomial model was obtained for the prediction of extraction recovery. The experimental results were fitted to the quadratic model, and ANOVA confirmed its statistical significance (Supplementary Materials Table S2). The overall model p-value was < 0.0001, indicating that the regression model was highly significant. The obtained models exhibited high determination coefficients (R2 > 0.90 for all responses), demonstrating excellent agreement between the predicted and experimental values. The coefficients R2, adjusted R2, and predicted R2 for each response are summarized in Table 4. These results confirm that the model reliably predicts the system behavior within the studied factor space. Furthermore, the lack-of-fit values were not significant (p > 0.05), indicating that the model was adequate and that no substantial variation remained unexplained by the regression. The coded regression coefficients obtained from the Box–Behnken model are presented in Table S3, indicating the magnitude and direction (positive or negative) of each factor’s effect on the extraction recovery. The residual plots (Figure S4) confirmed the validity of the Box–Behnken model. Collectively, these statistical indicators demonstrate that the fitted quadratic models appropriately describe the experimental data and are suitable for optimizing the NADES-based DLLME conditions.

Table 4.

Coefficients of determination (R2, adjusted R2, predicted R2) and lack-of-fit values for the quadratic models.

Regression equations for responses:

Recovery= = 64.00 + 11.63 pH + 3.63 VortexSpeed + 1.00 VortexTime + 1.38 pH2 + 4.87 VortexSpeed2 + 2.13 VortexTime2 − 2.25 (pH VortexSpeed) + 1.00 (pH VortexTime) + 3.00 (VortexSpeed VortexTime)

Recovery25B-NBOMe = 68.67 + 13.25 pH + 3.13 VortexSpeed − 0.88 VortexTime − 0.08 pH2 − 0.33 VortexSpeed2 + 0.17 VortexTime2 − 0.75 (pH VortexSpeed) − 2.25 (pH VortexTime) − 1.50 (VortexSpeed · VortexTime)

Recovery25C-NBOMe = 65.00 + 15.500 pH + 4.125 VortexSpeed − 0.375 VortexTime+ 2.00 pH2 + 1.75 VortexSpeed2 + 3.75 VortexTime2 − 1.25 (pH · VortexSpeed) − 1.75 (pH VortexTime) + 0.50 (VortexSpeed VortexTime)

Recovery25I-NBOMe=64.67 + 14.375 pH + 4.000 VortexSpeed + 1.125 VortexTime + 0.42 pH2 + 3.67 VortexSpeed2 + 3.42 VortexTime2 − 0.75 (pH · VortexSpeed) − 2.00 (pH VortexTime) + 3.75 (VortexSpeed VortexTime)

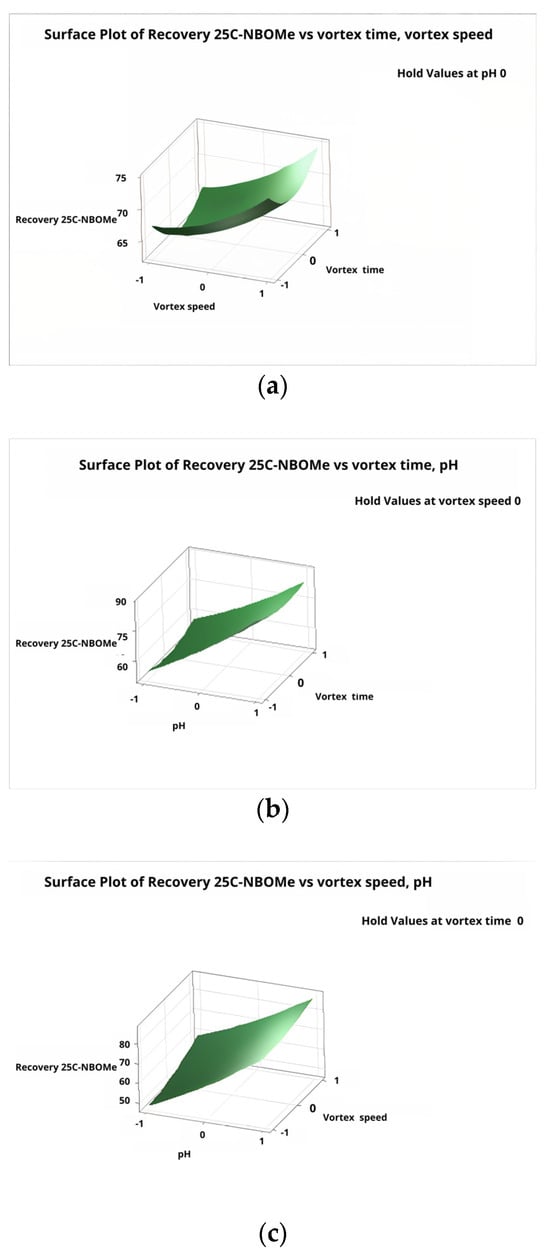

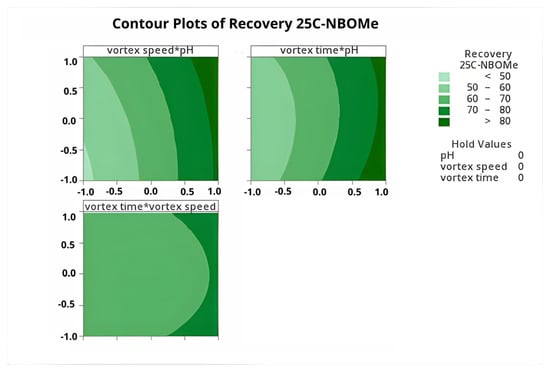

Figure 5 and Figure 6 illustrate the response surface and contour plots derived from the regression model for the recovery of 25C-NBOMe (corresponding plots for the remaining analytes are provided in the Supplementary Material Figures S5–S8). The results clearly show that higher pH values favor improved extraction efficiency, with the optimal response observed at pH 12. Vortex speed also exhibited a strong positive effect on recovery, confirming its role in enhancing dispersion and mass transfer during the DLLME process.

Figure 5.

Response surface plots obtained from the Box–Behnken design (BBD) showing the combined effects of: (a) vortex time and vortex speed; (b) vortex time and sample pH; and (c) vortex speed and sample pH on the extraction recovery of 25C-NBOMe.

Figure 6.

Contour plots generated from the BBD showing the combined effects of vortex speed, vortex time, and sample pH on the extraction recovery of 25C-NBOMe.

In contrast, vortex time did not significantly affect extraction efficiency, suggesting that phase equilibrium is reached quickly. Increasing mixing time beyond this point does not improve analyte recovery. Similar findings have been noted in previous DLLME studies, where the extent of dispersion—rather than how long it lasts—was the key factor influencing extraction performance.

3.4. Model Validation and Predicted Recoveries

The predicted recoveries obtained from the fitted Box–Behnken model are summarized in Table S5. The model predicted recoveries of 86.9%, 92.5%, 88.7%, and 80.4% for 25I-, 25C-, 25B-NBOMe, and 2C-B, respectively. The low standard errors (2.7–3.5) and narrow confidence intervals confirm the model’s precision and predictive reliability. The experimental recoveries were within the 95% prediction intervals, validating the adequacy of the proposed quadratic model.

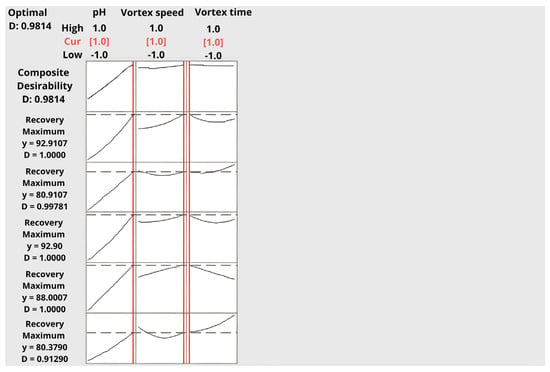

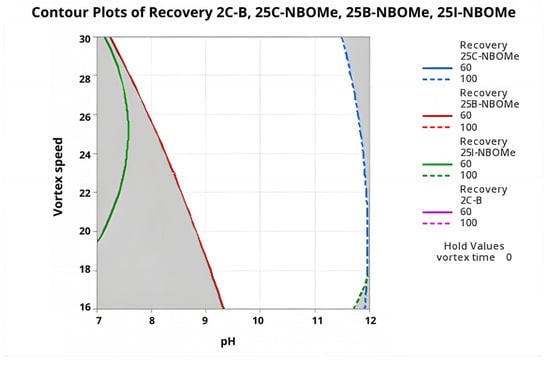

3.5. Optimization of Experimental Parameters Using Desirability Function

The desirability function was applied to identify the combination of factor levels that simultaneously maximized extraction recovery for all analytes. The optimization revealed that the most desirable conditions were achieved at a sample pH of 12, a vortex time of 20 s, and a vortex speed of 30,000 rpm, yielding a high composite desirability value of 0.9848 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Optimal DLLME extraction conditions and predicted recovery values for analytes.

As presented in Figure 7 and Figure 8, the individual desirability curves for 2C-B, 25B-NBOMe, 25C-NBOMe, and 25I-NBOMe all reached their maxima within the same region of factor space, confirming a consistent and robust optimization outcome. The steep increase in desirability with increasing pH highlights its dominant influence on extraction performance. Vortex speed showed a moderate positive effect, whereas vortex time exhibited only a minor stabilizing role, consistent with the rapid attainment of phase equilibrium observed in DLLME systems.

Figure 7.

Desirability function plots for multi-response optimization showing the influence of sample pH, vortex speed, and vortex time on the individual and composite desirability values for all analytes.

Figure 8.

Multi-response contour plot illustrating the combined effects of sample pH and vortex speed on the extraction recovery of the four phenethylamines (vortex time held constant).

The high composite desirability value confirms that the optimized conditions provide near-optimal extraction efficiency for all four analytes. The agreement between predicted and experimentally obtained recovery values further validates the accuracy and predictive strength of the fitted response surface model. To verify the optimization, three additional experiments were conducted under the identified optimal conditions. The experimentally obtained average recoveries differed from predicted values by only 3.50%, demonstrating excellent model validity and confirming that the optimized NADES-based DLLME procedure is both statistically reliable and experimentally reproducible.

From the perspective of GAT, these findings are particularly important. Efficient extraction with short vortexing time directly reduces energy consumption and shortens the analytical cycle, fully aligning with the principles of green, sustainable sample preparation. Furthermore, identifying pH and vortex speed as the key influential parameters strengthens the method’s robustness while minimizing unnecessary reagent and resource use. Together, these aspects further enhance the greenness and overall sustainability of the developed hydrophobic NADES-based DLLME procedure, supporting its suitability for environmentally responsible analytical toxicology workflows.

3.6. Green and Blue Chemistry Metric-Based Evaluation

Key parameters of developed sample preparation techniques for hallucinogenic phenethylamines, demonstrating markedly reduced solvent, sample, and plastic waste use, as well as energy and time consumption, compared to five previously published methods, are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Comparison of the developed extraction procedures and reference extraction procedures.

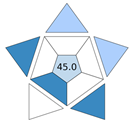

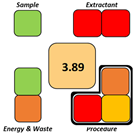

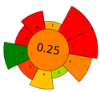

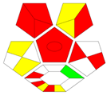

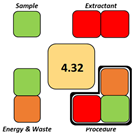

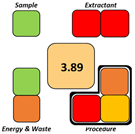

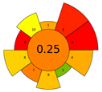

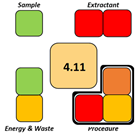

Nevertheless, the developed NADES-based DLLME method was comprehensively assessed using four complementary tools—AGREEprep, SPRS, ComplexGAPI, and BAGI—to evaluate its greenness, sustainability, and practical applicability. AGREEprep and SPRS quantify the environmental and sustainability aspects of the sample-preparation step, whereas BAGI evaluates operational feasibility, simplicity, and routine applicability. ComplexGAPI, an expanded version of the Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI), provides a holistic assessment by incorporating pre-analytical processes that are often excluded from conventional greenness evaluations.

The obtained results consistently demonstrated that the proposed method outperformed all compared extraction procedures reported in the literature, including solid phase extraction (SPE) [38,39], liquid–liquid extraction (LLE) with conventional solvents [40], DLLME with conventional solvents [41], and microextraction by packed sorbent (MEPS) [42]. Table 7 presents the scale outcomes for our developed extraction method and for five previously published methods.

Table 7.

Pictogram-based comparison of sustainability metrics for the developed DLLME–NADES method and reference extraction procedures.

Across all three numerical metrics, the NADES-based DLLME method demonstrated the highest greenness (AGREEprep), sustainability (SPRS), and operational applicability (BAGI) among the evaluated extraction techniques. According to AGREEprep, the developed method achieved the highest score (0.83), clearly outperforming SPE methods reported by Poklis et al. [38] and Johnson et al. [38], LLE with conventional solvents by Caspar et al. [40], DLLME with conventional solvents by Pasin et al. [41], and MEPS by Lesne et al. [42].

The SPRS evaluation further confirmed the superior sustainability of the NADES-based DLLME procedure, which obtained a score of 8.11—substantially higher than the corresponding values for all reference methods. From an operational feasibility perspective, the BAGI score of 75 indicates that the method is not only environmentally preferable but also simple, rapid, and suitable for routine laboratory workflows, even exceeding MEPS, which has a comparatively favorable performance.

These conclusions were reinforced by the ComplexGAPI pictogram, which exhibited minimal red and orange zones, indicating significantly lower environmental burden relative to all conventional extraction procedures.

Overall, all greenness and sustainability assessment tools—AGREEprep, SPRS, BAGI, and ComplexGAPI—consistently demonstrated that the hydrophobic NADES-based DLLME method is greener, more sustainable, and more practically applicable than traditional extraction approaches. These findings confirm the method’s strong alignment with the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry, Green Sample Preparation, and the broader framework of White Analytical Chemistry.

4. Discussion

4.1. Strategy for Extraction Optimization According to White Chemistry Principles (Red, Green, Blue Principles)

In response to the rising demand for sustainable analytical methods, this study was designed following the principles of GAC and further developed within the Red–Green–Blue (RGB) model of WAC proposed by Nowak et al. [2]. According to this model, the green dimension assesses environmental impact, reagent toxicity, and waste reduction; the red dimension reflects analytical performance—including sensitivity, selectivity, precision, and robustness; while the blue dimension focuses on practicality, productivity, energy efficiency, operator safety, and overall feasibility in routine laboratory settings.

A method is considered “white” when all three dimensions are balanced simultaneously, achieving a scientifically justified compromise among sustainability, analytical reliability, and operational practicality. This work aimed not only to develop a greener sample preparation technique but also to create a fully “white” method suited for modern forensic and clinical toxicology—fields that require high analytical performance without sacrificing environmental and occupational safety. The NADES-based DLLME method developed here finds a balance: it uses benign solvents and produces minimal waste (green), delivers high recoveries and robustness through DoE-optimized parameters (red), and ensures speed, cost-effectiveness, and ease of routine use (blue). The following sections provide a detailed explanation of the method through each element of the RGB model.

This multidimensional balance positions the method within the domain of white chemistry, supporting its suitability for modern analytical toxicology workflows.

Within the RGB model of WAC, the performance of the developed DLLME–NADES method can be interpreted through three complementary dimensions—green (environmental aspects), red (analytical performance), and blue (operational feasibility). Their integration highlights the method’s balanced profile and its suitability for modern forensic and clinical toxicology.

4.1.1. Blue Dimension (Operational Simplicity, Productivity, Cost-Effectiveness)

- The analytical standards required for this study were already available through the UNODC Early Warning System, contributing to the overall cost-effectiveness of the method.

- The UHPLC–MS/MS platform is widely available and substantially less expensive than high-resolution mass spectrometry instruments, improving global applicability and meeting the “requirements” principle of the blue dimension.

- UHPLC provides very rapid chromatographic separation (≈3.5 min), which is essential for toxicological analyses requiring a short turnaround time.

- DLLME ensures excellent time-efficiency; both vortex-assisted and air-assisted dispersion techniques are extremely fast while consuming significantly less energy than ultrasound- or shaker-based procedures.

- Dispersion requires only simple, inexpensive, and universally available equipment (vortex mixer and syringe), avoiding the need for high-cost devices such as microwave- or ultrasound-assisted extraction systems.

- The method uses minimal quantities of low-cost solvents, positively influencing affordability and operational sustainability.

- Methanol was selected as the organic component of the mobile phase because LC–MS-grade methanol is approximately five times cheaper than ethanol (market analysis, May 2025).

- DLLME eliminates the need for consumables (SPE cartridges, SPME fibers, MEPS syringes), reducing both operational costs and solid waste.

- The procedure also does not require a dispersive solvent, improving both operator safety and economic efficiency.

- The DoE strategy (FFD followed by BBD) enabled efficient optimization with a minimized number of experiments, reducing time, solvents, and energy use.

- The overall simplicity of the DLLME protocol allows routine implementation without specialized training, fulfilling the operational simplicity requirement of the blue dimension.

4.1.2. Red Dimension (Analytical Performance and Robustness)

- The extraction and analytical procedures were designed to enable simultaneous multi-analyte detection of structurally related hallucinogenic phenethylamines.

- Because these compounds appear at trace levels in biological matrices, UHPLC–MS/MS is required to achieve adequate sensitivity and selectivity, unlike PDA or UV detectors.

- DLLME provided efficient preconcentration and enrichment, resulting in approximately a five-fold increase in analyte concentration and improved detection capability.

4.1.3. Green Dimension (Environmental Sustainability and Safety)

- UHPLC contributes to improved environmental performance due to low mobile-phase consumption (0.3 mL/min) and short run time (3.5 min).

- DLLME inherently uses minimal quantities of both sample and solvent (1 mL and 200 μL), resulting in exceptionally low waste generation.

- Hydrophobic NADES were used as extraction solvents; these biodegradable, low-toxicity mixtures are fully aligned with the principles of GAC.

- DLLME generates no consumable waste in contrast to SPE cartridges, MEPS syringes, or SPME fibers, further reducing environmental burden.

- The method avoids the use of toxic dispersive solvents (e.g., acetonitrile, isopropanol), improving operator safety.

- The application of a DoE-based optimization strategy reduced unnecessary experimentation and minimized resource use.

4.2. Extraction Optimization Process

The superior extraction ability of the menthol–decanoic acid NADES, compared to other hydrophobic systems (menthol–acetic, menthol–formic, and menthol–dodecanoic acid), can be attributed to the optimal balance of hydrophobicity, viscosity, and intermolecular interactions within this eutectic mixture. Short-chain acids like formic and acetic produce more polar and partially water-miscible NADES formulations, which reduce the partitioning efficiency of hydrophobic analytes into the extraction phase. Conversely, the long-chain dodecanoic acid creates a significantly more viscous eutectic liquid, hindering droplet dispersion and limiting mass transfer during DLLME. Decanoic acid, as a medium-chain fatty acid, offers the best compromise—enough hydrophobicity to promote analyte partitioning, along with sufficient fluidity to ensure effective dispersion. This facilitates enhanced analyte–solvent interactions driven by hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces, leading to the highest extraction efficiencies among the tested NADES formulations.

An additional practical advantage of menthol–decanoic acid NADES is its ease of preparation. A homogeneous liquid phase was achieved at a lower temperature and in a shorter time using an ultrasonic water bath, in contrast to previously published protocols. For instance, Adeoye et al. [43] used a magnetic stirrer hot plate at 80 °C, while Elgharbawy et al. [37] reported heating at 70 °C for up to 4 h without stirring. The reduced energy demand and shorter preparation time observed in this study are further in line with the blue principles of WAC, particularly those relating to time-efficiency and energy conservation.

A comparison of the organic acids used for NADES preparation highlights key differences in their health and ecotoxicological profiles. Although numerous studies have reported mixtures containing formic and acetic acids as NADES [44,45,46], their natural origin does not ensure low toxicity. Both acids remain corrosive, volatile, and potentially hazardous despite often being classified as “natural” components. In contrast, decanoic acid is commonly found in dietary sources such as coconut oil, palm oil, dairy products, and certain fish (eel and salmon), and it is linked to several proven health benefits [47,48]. Its lower volatility, reduced corrosiveness, and favorable toxicological profile make it a safer, more biocompatible, and environmentally responsible option for developing sustainable extraction systems.

The significant influence of pH in the FFD can be explained by changes in the ionization state of both the target analytes and the hydrophobic NADES components. At higher pH levels, a larger proportion of phenethylamines exists in their neutral, non-ionized form, which enhances their transfer into the hydrophobic extraction phase. This behavior aligns with previous reports indicating that pH is one of the primary factors affecting the efficiency of liquid–liquid microextraction systems [49,50,51].

Vortex-assisted and air-assisted dispersion techniques were chosen because they align well with both the green and blue principles of white chemistry. Both methods have been successfully used in many extraction procedures due to their simplicity and low energy needs. Vortex-assisted dispersion is widely recognized for its high extraction efficiency and low time and energy use [52,53,54]. Air-assisted dispersion, on the other hand, is completely energy-free, although its extraction efficiency may be limited by reduced mass transfer.

Increasing vortex speed enhances the dispersion of the NADES phase in the aqueous sample, producing smaller droplets and increasing the interfacial surface area between the phases. This greatly improves analyte transfer into the extraction solvent and boosts overall extraction yield. However, extending the mixing time beyond the optimal point does not further boost recovery; prolonged vortexing may even cause some analytes to partially back-extract into the aqueous phase. Similar findings have been observed in other DLLME studies, where dispersion intensity—rather than dispersion duration—was identified as the key factor affecting extraction efficiency [52,53].

From the perspective of GAT, these findings are especially significant. Achieving high extraction efficiency with brief vortexing times directly indicates reduced energy use and a quicker analytical cycle, fully aligning with the principles of green and sustainable sample preparation. Additionally, pinpointing pH and vortex speed as the main influential parameters boosts the method’s robustness while minimizing unnecessary resource consumption, further supporting the eco-friendliness of the developed NADES-based DLLME procedure.

The values obtained for MEPS [42] and the developed NADES-based DLLME method by analytical chemistry metrics were comparable, but several advantages of the proposed approach became evident. Unlike MEPS, which requires specialized syringes and is limited in sample volume, DLLME allows straightforward handling of larger sample amounts and enables efficient preconcentration, resulting in higher enrichment factors [16,55]. When combined with the use of green NADES, these qualities make DLLME not only more sustainable but also a more practical, scalable, and versatile option for routine sample preparation in clinical and forensic laboratories.

Despite the many benefits shown by the developed method, slightly lower scores were seen in several evaluation tools. These outcomes can be linked to methodological and instrumental factors that are common in high-performance toxicological analyses. Although overall solvent use remains minimal, the use of organic modifiers in the mobile phase (methanol and formic acid) negatively affects certain green metrics. Additionally, the need for a tandem mass spectrometer—which is crucial for achieving the selectivity and sensitivity needed to detect trace levels of synthetic hallucinogens—is associated with relatively high energy consumption and operational costs, impacting sustainability indicators. Furthermore, even though the centrifugation and vortexing steps are brief, they still contribute to moderate energy use, and including minor sample pretreatment steps involving small amounts of hazardous reagents slightly reduces the greenness scores.

However, these limitations are justified in the context of toxicological testing, where analytical selectivity, sensitivity, and method reliability must take precedence over the complete removal of all non-green elements. The NADES-based DLLME method developed here thus offers a scientifically valid and environmentally conscious balance between sustainability and the demanding analytical standards of forensic and clinical toxicology.

5. Conclusions

A green, sustainable, and analytically robust method was successfully developed for detecting selected hallucinogenic phenethylamines in urine. By combining dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction based on hydrophobic natural deep eutectic solvents with UHPLC–MS/MS detection, the proposed approach offers a sensitive, selective, and eco-friendly solution ideally suited for routine clinical and forensic toxicology.

The extraction process was thoroughly optimized using a design of experiments approach, allowing for the identification of optimal conditions (pH 12, vortex time 20 s, vortex speed 30,000 rpm, centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 3 min). These conditions produced high extraction efficiencies for all analytes. The statistical model showed excellent fit, predictive accuracy, and robustness, confirming its reliability for guiding method optimization.

Using hydrophobic NADES as extraction solvents replaced traditional volatile and hazardous organic solvents, greatly enhancing the environmental profile, safety, and operator acceptability of the method. Comprehensive evaluation with AGREEprep, ComplexGAPI, SPRS, and BAGI verified strong adherence to the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry and the broader White Analytical Chemistry concept, integrating environmental sustainability, analytical performance, and operational feasibility.

Overall, the NADES-based DLLME method offers a practical, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly analytical solution. It shows that high analytical performance can be achieved without sacrificing sustainability and highlights the potential of NADES-based microextraction as a valuable platform for future applications in Green Analytical Toxicology, including routine monitoring of novel psychoactive substances in clinical and forensic settings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152412927/s1. Figure S1: Normal plot of standardized effects for the factorial design (a) Recovery (%) 2C-B (b) Recovery (%) 25B–NBOME (c) Recovery (%) 25I-NBOMe, Figure S2: Half-normal plot of Standardized Effects for the FFD (a) Recovery (%) 2C-B (b) Recovery (%) 25B–NBOME (c) Recovery (%) 25I-NBOMe, Figure S3: Pareto chart of standardized effects for the factorial design (a) Recovery (%) 2C-B (b) Recovery (%) 25B–NBOME (c) Recovery (%) 25I-NBOMe, Figure S4: Residual diagnostic plots for the Box–Behnken model (a) Recovery (%) 2C-B (b) Recovery (%) 25B–NBOME (c) Recovery (%) 25C-NBOMe (d) Recovery (%) 25I-NBOMe, Figure S5: Contour plots of extraction recovery for analytes obtained from the Box–Behnken design (a) Recovery (%) 2C-B (b) Recovery (%) 25B–NBOME (c) Recovery (%) 25I-NBOMe, Figure S6: Response surface plots of extraction recovery for analytes (a) Recovery 2C-B vs vortex time, vortex speed (b) Recovery 2C-B vs vortex speed, pH (c) Recovery 2C-B vs vortex time, pH, Figure S7: Response surface plots of extraction recovery for analytes (a) Recovery 25B-NBOMe vs vortex time, vortex speed (b) Recovery 25B-NBOMe vs vortex speed, pH (c) Recovery 25B-NBOMe vs vortex time, pH, Figure S8: Response surface plots of extraction recovery for analytes (a) Recovery 25I-NBOMe vs vortex time, vortex speed (b) Recovery 25I-NBOMe vs vortex speed, pH (c) Recovery 25I-NBOMe vs vortex time, pH; Table S1: ANOVA results for the fractional factorial design, Table S2: ANOVA results for the Box–Behnken design, Table S3: Coded regression coefficients obtained from the Box–Behnken model, Table S4: Mean response values for each factor level for FFD. Table S5: Predicted recovery values and 95% confidence/prediction intervals obtained from the Box–Behnken design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.K. and M.V.; methodology, M.V. and I.N.; software, E.K.; formal analysis, E.K.; investigation, E.K.; resources, A.C.-Đ. and A.A.; data curation, A.A. and M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, E.K. and A.A.; writing—review and editing, E.K., M.Đ. and I.N.; visualization, E.K.; supervision, M.V. and S.Đ.; project administration, M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the article and its Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Goran Ilić, Biljana Milosavljević, and Jovana Simić, and the entire staff of the Institute of Forensic Medicine in Niš, for their valuable support, collaboration, and assistance throughout this study. Their professional expertise and commitment significantly contributed to the successful completion of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NPS | Novel Psychoactive Substances |

| GC | Green Chemistry |

| GAC | Green Analytical Chemistry |

| GAT | Green Analytical Toxicology |

| WAC | White Analytical Chemistry |

| NADES | Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent |

| NADESs | Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents |

| DoE | Design of Experiments |

| RSM | Response Surface Methodology |

| FFD | Fractional Factorial Design |

| BBD | Box–Behnken Design |

| UHPLC-MS/MS | Ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography coupled to tan-dem mass spectrometry |

| GAPI | Green Analytical Procedure Index |

| BAGI | Blue Applicability Grade Index |

| SPRS | Sample Preparation Metric of Sustainability |

| LLE | Liquid–Liquid Extraction |

| DLLME | Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction |

| SPE | Solid Phase Extraction |

| MEPS | Microextraction by Packed Sorbent |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Mass spectrometer parameters.

Table A1.

Mass spectrometer parameters.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Nebulizing Gas Flow | 1.8 L min−1 |

| Desolvation Line Temperature | 300 °C |

| Heat Block temperature | 300 °C |

| Drying Gas Flow | 10 L min−1 |

| Dwell Time | 20 ms |

| Pause Time | 1 ms |

Table A2.

Optimized MRM transitions and mass spectrometric parameters for the selected phenethylamines.

Table A2.

Optimized MRM transitions and mass spectrometric parameters for the selected phenethylamines.

| Analyte | Precursor m/z | Production | Collision Energy (V) | Q1 Pre Bias (V) | Q3 Pre Bias (V) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | m/z | |||||

| 2C-B | 259.90 | Reference | 242.90 | −14 | −13 | −11 |

| Target | 228.10 | −22 | −18 | −24 | ||

| 25B-NBOMe | 380.00 | Reference | 121.10 | −22 | −11 | −23 |

| Target | 91.20 | −55 | −26 | −17 | ||

| 25C-NBOMe | 336.10 | Reference | 121.10 | −20 | −13 | −22 |

| Target | 91.10 | −45 | −23 | −16 | ||

| 25I-NBOMe | 428.00 | Reference | 121.00 | −28 | −16 | −12 |

| Target | 91.15 | −55 | −12 | −18 | ||

Table A3.

Experimental matrix of the 25-1 FFD used to identify significant dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction DLLME parameters.

Table A3.

Experimental matrix of the 25-1 FFD used to identify significant dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction DLLME parameters.

| Std Order | Run Order | Center Pt | Blocks | pH (Coded) | Salt Concentration (Coded) | Dispersion Method (Coded) | Solvent Amount (Coded) | Centrifugation Time (Coded) | Recovery (%) | |||

| 25C-NBOMe | 2C-B | 25I-NBOMe | 25B-NBOMe | |||||||||

| 13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 56 | 55 | 45 | 47 |

| 15 | 2 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 65 | 50 | 61 | 53 |

| 6 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 95 | 91 | 77 | 85 |

| 9 | 4 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 45 | 42 | 46 | 36 |

| 7 | 5 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 60 | 52 | 59 | 52 |

| 16 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 71 | 82 | 67 | 85 |

| 5 | 7 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 65 | 55 | 52 | 50 |

| 4 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 72 | 70 | 66 | 65 |

| 10 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 70 | 62 | 58 | 63 |

| 8 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 91 | 79 | 77 | 80 |

| 1 | 11 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 57 | 50 | 45 | 47 |

| 2 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 72 | 68 | 65 | 50 |

| 11 | 13 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 48 | 43 | 44 | 45 |

| 12 | 14 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 83 | 74 | 60 | 52 |

| 3 | 15 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 55 | 49 | 43 | 51 |

| 14 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 94 | 90 | 74 | 75 |

Table A4.

Box–Behnken Design matrix for optimization of significant dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction variables.

Table A4.

Box–Behnken Design matrix for optimization of significant dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction variables.

| Std Order | Run Order | Pt Type | Blocks | pH (Coded) | Vortex Speed (Coded) | Vortex Time (Coded) | Recovery (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2C-B | 25I-NBOMe | 25B-NBOMe | 25C-NBOMe | |||||||

| 11 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | −1 | 1 | 63 | 66 | 65 | 65 |

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 83 | 87 | 82 | 85 |

| 7 | 3 | 2 | 1 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 58 | 57 | 56 | 55 |

| 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 0 | 63 | 61 | 59 | 60 |

| 9 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 70 | 72 | 64 | 67 |

| 8 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 82 | 83 | 80 | 86 |

| 6 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | −1 | 75 | 84 | 86 | 90 |

| 2 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 0 | 82 | 78 | 79 | 80 |

| 10 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | −1 | 73 | 70 | 75 | 75 |

| 13 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 61 | 63 | 66 | 65 |

| 14 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 64 | 68 | 73 | 66 |

| 15 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 67 | 63 | 67 | 64 |

| 1 | 13 | 2 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 53 | 49 | 53 | 50 |

| 12 | 14 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 78 | 79 | 70 | 75 |

| 5 | 15 | 2 | 1 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 55 | 50 | 53 | 52 |

Figure A1.

Representative UHPLC chromatogram of the selected hallucinogenic phenethylamines (2C-B, 25B-NBOMe, 25C-NBOMe, 25I-NBOME) obtained under the optimized chromatographic conditions.

References

- Anastas, P.T.; Warner, J. Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 9780198506980. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, P.M.; Kościelniak, P. What Color Is Your Method? Adaptation of the RGB Additive Color Model to Analytical Method Evaluation. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 10343–10352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastas, P.T. Green Chemistry and the Role of Analytical Methodology Development. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 1999, 29, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula Meirelles, G.; Fabris, A.L.; Ferreira Dos Santos, K.; Costa, J.L.; Yonamine, M. Green Analytical Toxicology for the Determination of Cocaine Metabolites. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2023, 46, 965–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Ameer, K.; Ramachandraiah, K.; Yu, X.; Qian, X.; Zhou, Z.; Jiang, G. Structural and Functional Characterization of Kiwi Berry Dietary Fiber Extracted Using Water, Wet Ball Milling, and Water-Homogenization Methods. Food Qual. Saf. 2025, 9, fyaf032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Cao, H.; Li, Y. Simultaneous Determination of Trace Matrine and Oxymatrine Pesticide Residues in Tea by Magnetic Solid-Phase Extraction Coupled with Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Anal. Test. 2024, 8, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Cheng, S.; Boonyubol, S.; Cross, J.S. Evaluating Green Solvents for Bio-Oil Extraction: Advancements, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Energies 2023, 16, 5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, M.M.; Müller, S.; González de Castilla, A.; Gurikov, P.; Matias, A.A.; Bronze, M.d.R.; Fernández, N. Physicochemical Characterization and Simulation of the Solid-Liquid Equilibrium Phase Diagram of Terpene-Based Eutectic Solvent Systems. Molecules 2021, 26, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.A.R.; Pinho, S.P.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Insights into the Nature of Eutectic and Deep Eutectic Mixtures. J. Solut. Chem. 2019, 48, 962–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florindo, C.; Lima, F.; Ribeiro, B.D.; Marrucho, I.M. Deepeutectic Solvents: Overcoming 21st Century Challenges. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2019, 18, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereshti, H.; Seraj, M.; Soltani, S.; Rashidi Nodeh, H.; Hossein Shojaee Aliabadi, M.; Taghizadeh, M. Development of a Sustainable Dispersive Liquid−liquid Microextraction Based on Novel Hydrophobic and Hydrophilic Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Analysis of Multiclass Pesticides in Water. Microchem. J. 2022, 175, 107226. [Google Scholar]

- An, Y.; Row, K.H. Evaluation of Menthol-Based Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Extraction of Bisphenol A from Environment Water. Anal. Lett. 2021, 54, 1533–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Křížek, T.; Bursová, M.; Horsley, R.; Kuchař, M.; Tůma, P.; Čabala, R.; Hložek, T. Menthol-Based Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvents: Towards Greener and Efficient Extraction of Phytocannabinoids. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 193, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, M.; Ghassab, N.; Hemmati, M.; Asghari, A. Emulsification Microextraction of Amphetamine and Methamphetamine in Complex Matrices Using an up-to-Date Generation of Eco-Friendly and Relatively Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvent. J. Chromatogr. A 2018, 1576, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Hu, L.; Liu, X.; Yin, S.; Lu, R.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, W.; Gao, H. Deep Eutectic Solvent-Based Ultrasound-Assisted Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction Coupled with High-Performance Liquid Chromatography for the Determination of Ultraviolet Filters in Water Samples. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1516, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Yahaya, N.; Mohamed, A.H.; Kabir, A.; Chandrawanshi, L.P.; AbdElrahman, M.; Ghoneim, M.M.; Bakkannavar, S.M. The Role of Emerging Sample Preparation Methods in Postmortem Toxicology: Green and Sustainable Approaches. Trends Analyt. Chem. 2023, 168, 117354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokosa, J.M. Selecting an Extraction Solvent for a Greener Liquid Phase Microextraction (LPME) Mode-Based Analytical Method. Trends Analyt. Chem. 2019, 118, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callao, M.P. Multivariate Experimental Design in Environmental Analysis. Trends Analyt. Chem. 2014, 62, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiz Caleffo Piva Bigão, V.; Ruiz Brandão da Costa, B.; Joaquim Mangabeira da Silva, J.; Spinosa De Martinis, B.; Tapia-Blácido, D.R. Use of Statistical Design of Experiments (DoE) in Forensic Analysis: A Tailored Review. Forensic Chem. 2024, 37, 100554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMCDDA. European Drug Report 2021: Trends and Developments. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; EUDA: Lisbon, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, M.; Phonekeo, K.; Paine, J.S.; Leth-Petersen, S.; Begtrup, M.; Bräuner-Osborne, H.; Kristensen, J.L. Synthesis and Structure-Activity Relationships of N-Benzyl Phenethylamines as 5-HT2A/2C Agonists. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2014, 5, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Álvarez, M.; Turiel, E.; Martín-Esteban, A. Hydrophobic Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents Based on L-Menthol as Supported Liquid Membrane for Hollow Fiber Liquid-Phase Microextraction of Triazines from Water and Urine Samples. Microchem. J. 2023, 194, 109347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqarni, A.M.; Mostafa, A.; Shaaban, H.; Gomaa, M.S.; Albashrayi, D.; Hasheeshi, B.; Bakhashwain, N.; Aseeri, A.; Alqarni, A.; Alamri, A.A.; et al. Development and Optimization of Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent-Based Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction Coupled with UPLC-UV for Simultaneous Determination of Parabens in Personal Care Products: Evaluation of the Eco-Friendliness Level of the Developed Method. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 13183–13194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Zamora, C.; González-Sálamo, J.; Hernández-Sánchez, C.; Hernández-Borges, J. Menthol-Based Deep Eutectic Solvent Dispersive Liquid–liquid Microextraction: A Simple and Quick Approach for the Analysis of Phthalic Acid Esters from Water and Beverage Samples. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 8783–8794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento, M.T.; da Silva, E.L.; Fraga, G.N.; Dragunski, D.C.; Tarley, C.R.T. Development of an Eco-Friendly Liquid-Liquid Preconcentration Method for the Direct Determination of Herbicides in Sugarcane-Derived Foods Using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent (NADES). Food Chem. 2025, 496, 146563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kongpol, K.; Chaihao, P.; Shuapan, P.; Kongduk, P.; Chunglok, W.; Yusakul, G. Therapeutic Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvents of Menthol and Fatty Acid for Enhancing Anti-Inflammation Effects of Curcuminoids and Curcumin on RAW264.7 Murine Macrophage Cells. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 17443–17453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, P.K.; Kundu, D.; Bairagya, P.; Banerjee, T. Phase Behavior of Water-Menthol Based Deep Eutectic Solvent-Dodecane System. Chem. Thermodyn. Therm. Anal. 2021, 3–4, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.; Silva, E.; Matias, A.; Silva, J.M.; Reis, R.L.; Duarte, A.R.C. Menthol-Based Deep Eutectic Systems as Antimicrobial and Anti-Inflammatory Agents for Wound Healing. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 182, 106368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, P.M.; Wietecha-Posłuszny, R.; Pawliszyn, J. White Analytical Chemistry: An Approach to Reconcile the Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry and Functionality. Trends Analyt. Chem. 2021, 138, 116223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, P.M.; Kościelniak, P.; Tobiszewski, M.; Ballester-Caudet, A.; Campíns-Falcó, P. Overview of the Three Multicriteria Approaches Applied to a Global Assessment of Analytical Methods. Trends Analyt. Chem. 2020, 133, 116065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, L.; Tamiji, Z.; Khoshayand, M.R. Applications and Opportunities of Experimental Design for the Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction Method—A Review. Talanta 2018, 190, 335–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.L.C.; Bruns, R.E.; Ferreira, H.S.; Matos, G.D.; David, J.M.; Brandão, G.C.; da Silva, E.G.P.; Portugal, L.A.; dos Reis, P.S.; Souza, A.S.; et al. Box-Behnken Design: An Alternative for the Optimization of Analytical Methods. Anal. Chim. Acta 2007, 597, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płotka-Wasylka, J.; Wojnowski, W. Complementary Green Analytical Procedure Index (ComplexGAPI) and Software. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 8657–8665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnowski, W.; Tobiszewski, M.; Pena-Pereira, F.; Psillakis, E. AGREEprep—Analytical Greenness Metric for Sample Preparation. Trends Analyt. Chem. 2022, 149, 116553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manousi, N.; Wojnowski, W.; Płotka-Wasylka, J. Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI) and Software: A New Tool for the Evaluation of Method Practicality. Green Chem 2023, 25, 7598–e7604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Martín, R.; Gutiérrez-Serpa, A.; Pino, V.; Sajid, M. A Tool to Assess Analytical Sample Preparation Procedures: Sample Preparation Metric of Sustainability. J. Chromatogr. A 2023, 1707, 464291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgharbawy, A.; Syed Putra, S.; Khan, H.; Azmi, N.; Sani, M.; Ab Llah, N.; Hayyan, A.; Jewaratnam, J.; Basirun, W. Menthol and Fatty Acid-Based Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvents as Media for Enzyme Activation. Processes 2023, 11, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poklis, J.L.; Devers, K.G.; Arbefeville, E.F.; Pearson, J.M.; Houston, E.; Poklis, A. Postmortem Detection of 25I-NBOMe [2-(4-Iodo-2,5-Dimethoxyphenyl)-N-[(2-Methoxyphenyl)methyl]ethanamine] in Fluids and Tissues Determined by High Performance Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry from a Traumatic Death. Forensic Sci. Int. 2014, 234, e14–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.D.; Botch-Jones, S.R.; Flowers, T.; Lewis, C.A. An Evaluation of 25B-, 25C-, 25D-, 25H-, 25I- and 25T2-NBOMe via LC–MS-MS: Method Validation and Analyte Stability. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2014, 38, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspar, A.T.; Kollas, A.B.; Maurer, H.H.; Meyer, M.R. Development of a Quantitative Approach in Blood Plasma for Low-Dosed Hallucinogens and Opioids Using LC-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Talanta 2018, 176, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasin, D.; Bidny, S.; Fu, S. Analysis of New Designer Drugs in Post-Mortem Blood Using High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2015, 39, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesne, E.; Muñoz-Bartual, M.; Esteve-Turrillas, F.A. Determination of Synthetic Hallucinogens in Oral Fluids by Microextraction by Packed Sorbent and Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2023, 415, 3607–3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoye, D.O.; Gano, Z.S.; Ahmed, O.U.; Shuwa, S.M.; Atta, A.Y.; Iwarere, S.A.; Jubril, B.Y.; Daramola, M.O. Synthesis and Characterisation of Menthol-Based Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvents. In Proceedings of the ECSOC 2023, Online, 15–30 November 2023; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2023; p. 98. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Zamora, C.; Jiménez-Skrzypek, G.; González-Sálamo, J.; Hernández-Borges, J. Extraction of Phthalic Acid Esters from Soft Drinks and Infusions by Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction Based on the Solidification of the Floating Organic Drop Using a Menthol-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1646, 462132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Álvarez, M.; Martín-Esteban, A. Preparation and Further Evaluation of L-Menthol-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents as Supported Liquid Membrane for the Hollow Fiber Liquid-Phase Microextraction of Sulfonamides from Environmental Waters. Adv. Sample Prep. 2022, 4, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, H. Sustainable Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction Method Utilizing a Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent for Determination of Chloramphenicol in Honey: Assessment of the Environmental Impact of the Developed Method. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 5058–5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Yang, W.; Li, M.; Li, F.; Gong, R.; Wu, Y. Relationship between Dietary Decanoic Acid and Coronary Artery Disease: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoji, H.; Kunugi, H.; Miyakawa, T. Acute and Chronic Effects of Oral Administration of a Medium-Chain Fatty Acid, Capric Acid, on Locomotor Activity and Anxiety-like and Depression-Related Behaviors in Adult Male C57BL/6J Mice. Neuropsychopharmacol. Rep. 2022, 42, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, S.; Sellitepe, H.E. Vortex Assisted Liquid-Liquid Microextraction Based on in Situ Formation of a Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent by Microwave Irradiation for the Determination of Beta-Blockers in Water Samples. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1642, 462007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosiljkov, T.; Dujmić, F.; Cvjetko Bubalo, M.; Hribar, J.; Vidrih, R.; Brnčić, M.; Zlatic, E.; Radojčić Redovniković, I.; Jokić, S. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents and Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction: Green Approaches for Extraction of Wine Lees Anthocyanins. Food Bioprod. Process. 2017, 102, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ramos, R.; Herrera-Herrera, A.V.; Díaz-Romero, C.; Socas-Rodríguez, B.; Rodríguez-Delgado, M.Á. Eco-Friendly Approach Developed for the Microextraction of Xenobiotic Contaminants from Tropical Beverages Using a Camphor-Based Natural Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvent. Talanta 2024, 266, 124932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakalejčíková, S.; Bazeľ, Y.; Le Thi, V.A.; Fizer, M. An Innovative Vortex-Assisted Liquid-Liquid Microextraction Approach Using Deep Eutectic Solvent: Application for the Spectrofluorometric Determination of Rhodamine B in Water, Food and Cosmetic Samples. Molecules 2024, 29, 3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farajzadeh, M.A.; Ebrahimi, S.; Mehri, S.M.; Afshar Mogaddam, M.R. Vortex-Assisted Liquid-Liquid Microextraction for the Simultaneous Derivatization and Extraction of Five Primary Aliphatic Amines in Water Sample. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Mayor, Á.; Herrera-Herrera, A.V.; Rodríguez-Ramos, R.; Socas-Rodríguez, B.; Rodríguez-Delgado, M.Á. Development of a Green Alternative Vortex-Assisted Dispersive Liquid–liquid Microextraction Based on Natural Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Analysis of Phthalate Esters in Soft Drinks. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 2161–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, M.; Mehta, D.; Mashru, R. Recent Application of Green Analytical Chemistry: Eco-Friendly Approaches for Pharmaceutical Analysis. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 10, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).