Abstract

Advanced driver-assistance and autonomous systems require perception that is both robust and affordable. Monocular cameras are promising due to their ubiquity and low cost, yet detecting abrupt road surface irregularities such as curbs and bumps remains challenging. These sudden road gradient changes are often only a few centimeters high, making them difficult to detect and resolve from a single moving camera. We hypothesize that stable image-based homography, derived from robust geometric correspondences, is a viable method for predicting sudden road surface gradient changes. To this end, we propose a monocular, geometry-driven pipeline that combines transformer-based feature matching, homography decomposition, temporal filtering, and late-stage IMU fusion. In addition, we introduce a dedicated dataset with synchronized camera and ground-truth measurements for reproducible evaluation under diverse urban conditions. We conduct a targeted feasibility study on six scenarios specifically recorded for small, safety-relevant discontinuities (four curb approaches, two speed bumps). Homography-based cues provide reliable early signatures for curbs (3/4 curb sequences detected at a 5 cm threshold). These results establish feasibility for monocular, geometric curb detection and motivate larger-scale validation. The code and the collected data will be made publicly available.

1. Introduction

Advanced driver-assistance and autonomous systems will only scale if perception is both robust and affordable. Monocular cameras offer that promise. They are ubiquitous, low-power, and already present in most vehicles. Yet safety-critical events like abrupt changes in the road surface such as curbs and road edges are notoriously hard to detect from a single moving camera. These events can be subtle in height but consequential for planning and free-space estimation, making their early and reliable detection a key capability in camera-centric stacks.

Despite advances in perception, detecting abrupt road surface irregularities from a single moving camera remains an open problem. Curbs, edges, and small bumps may only rise a few centimeters, producing minimal visual displacement that is easily lost amid noise, texture variation, or motion blur. Traditional, non-AI approaches often assume flat, well-marked roads, leading to degraded performance in realistic urban environments where slopes, homogeneous asphalt, and occlusions are common. The challenge, therefore, is to determine whether a monocular camera can resolve such subtle geometric cues reliably enough to support safety-critical decision-making, and if so, how to design a pipeline that maximizes robustness within the sensor’s inherent limits.

Research on urban curb and sudden road surface irregularity detection spans three main families of methods: active depth sensing (LiDAR) [1,2,3,4,5], stereo vision [6,7,8,9], and purely image-based monocular techniques, as surveyed in [10]. Our work falls into the third category and differs by emphasizing monocular geometry, specifically stable, correspondence-driven homography combined with late-stage IMU fusion. Within this geometry-first design, we investigate whether the same monocular framework can yield predictive signatures for curb-like discontinuities. We treat speed bumps as a contrasting case to test the limits of a single-plane model rather than as a benchmark target.

LiDAR and other depth-sensing approaches detect height steps or depressions directly in 3D by segmenting the ground plane via robust fitting and classifying outliers as curbs or obstacles [3,4,5]. These pipelines provide high geometric accuracy but require costly active sensors and careful calibration. In contrast, we avoid range sensing altogether and infer irregularities from a single monocular camera, relying on homography decomposition stabilized by inertial cues. This trades direct metric depth for ubiquity, low cost, and wider applicability in camera-centric systems.

Stereo vision represents an intermediate approach, recovering dense disparity maps or elevation profiles that allow curb lines and surface deviations to be detected as height discontinuities. Representative systems fit geometric models to curb profiles or estimate bump geometry in real time [11,12]. These methods are effective but require paired cameras and precise calibration. By comparison, our method maintains minimal hardware demands, relying on monocular geometric constraints supported by IMU alignment.

Monocular image-based methods have been explored both in classical [13] and learning-based forms [14]. Early systems [15,16,17,18] used edges, texture cues, or heuristic thresholds, but these were highly sensitive to illumination changes and surface homogeneity [10]. More recently, convolutional neural networks have been applied to detect curbs [19], potholes, and speed bumps [20,21] directly from appearance, with strong performance reported on curated datasets. A recent example is the altitude-difference approach of Ma et al. [22], which leverages LiDAR-derived Altitude Difference Images (ADI) and a lightweight encoder–decoder network to detect curbs without manual annotation, though it remains fundamentally multi-sensor and appearance-driven rather than geometry-based. Our approach departs from appearance-only detection by prioritizing geometric signals: robust inter-frame correspondences are used to compute homography, from which ground-plane orientation and offsets are derived, and temporal filtering with an Extended Kalman Filter ensures stability. This design allows us to unify positive irregularities such as curbs and bumps with negative irregularities such as potholes, all within a single monocular, geometry-first pipeline tailored to urban environments. Because our goal is to test whether homography carries predictive geometric signal for centimeter-scale plane changes, direct comparison to appearance-based object detectors is orthogonal to the feasibility question and intentionally out of scope for this study.

A recurring debate in the field is whether monocular vision alone can capture subtle surface relief without explicit depth estimation, or whether only learning-based appearance models can achieve robust performance. Proponents of LiDAR and stereo emphasize the metric guarantees of explicit depth, while vision-based approaches highlight scalability and cost efficiency. Our stance is geometry-forward monocular sensing: we explicitly analyze the sensor’s detectability limits for centimeter-scale events, then leverage robust correspondences, homography, and IMU integration to approach these limits. In this framework, learning serves primarily to strengthen correspondence quality rather than to replace geometric reasoning. Accordingly, our evaluation is not a broad benchmark but a targeted probe of detectability limits using a small, purpose-built set of curb and speed-bump approaches.

We hypothesize that stable image-based homography, derived from robust geometric correspondences, is a viable method for predicting sudden road surface gradient changes such as curbs and road edges. Our contributions are the following:

- Demonstrate that image-based homography can capture subtle plane changes and curb-height road gradients from monocular input, establishing feasibility for safety-critical detection.

- Propose a monocular, geometry-driven pipeline that uses robust correspondences, homography decomposition, and temporal reasoning, complemented by late-stage IMU alignment.

- Release a small, purpose-built dataset (four curb, two speed-bump sequences) to test the binary detectability question under controlled conditions, laying groundwork for later large-scale studies.

- Report curb vs. speed-bump behavior, explaining why curbs exhibit a strong plane transition signature while speed bumps do not under a single-plane model.

Together, these contributions establish both the feasibility and the practical realization of monocular, geometry-driven detection of sudden road surface changes. By grounding the problem in sensor-level limits, and by combining robust image correspondences with inertial constraints, we provide a pathway toward camera-centric systems that remain cost-efficient while handling safety-critical events. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces the materials and methods, including the dataset, ground-truth generation, and the proposed architecture. Section 3 presents the experimental results. Section 4 discusses the implications, limitations, and potential directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

Our goal is to predict sudden road surface gradient changes, particularly curbs and road edges directly from visual input. Achieving this requires detecting subtle geometric variations in the image domain that correspond to meaningful physical changes in the road plane. Because these variations can be very small, the reliability of their detection is fundamentally constrained by the characteristics of the sensing system. Consequently, before introducing the details of our algorithm, we first investigate the limits of the imaging sensor itself, as these limits define the boundaries within which stable image-based algorithmic estimation can succeed. To make this goal concrete, we define a sudden change as a vertical displacement of approximately 5 cm. While this threshold is somewhat arbitrary, it is motivated by the fact that many speedbumps on roads are only about this height, and we therefore include them within our definition of sudden changes. With this definition in place, we can evaluate whether such changes are detectable within the accuracy limits of the sensing system.

When considering whether such small vertical displacements can be detected, it is important to first examine the accuracy of LiDAR sensors. Modern multi-channel LiDARs are capable of producing dense 3D point clouds with centimeter-level precision, making them well suited for reliable plane estimation. However, even with high-grade sensors, deviations greater than 5 cm can occur in practice, particularly when the LiDAR is mounted on top of a vehicle where longer ranges and steeper angles increase measurement uncertainty. This highlights the challenge of detecting subtle road surface variations. In our work, we aim to develop an image-based prediction system, therefore, the LiDAR is not used directly in the algorithm but instead serves to generate accurate ground truth for evaluation. By relying on LiDAR-derived ground truth, we ensure that our image-based method is benchmarked against actual physical measurements rather than indirect estimations, while also acknowledging that the task itself is difficult even for LiDAR.

This limitation of LiDAR can be partially mitigated by incorporating visual inspection. Since sudden changes such as curbs or speedbumps are clearly observable in the camera stream, we can verify when such events occur and annotate the corresponding frames manually. These annotations allow us to cross-check the LiDAR-derived ground truth and mark the precise moments when a sudden change should be detected. In this way, the combination of LiDAR measurements and human-supervised annotations provides a more reliable reference against which the performance of our image-based prediction system can be evaluated.

The core of our method is the homography-driven approach. In this framework, we derive a reliable ground plane normal by taking two consecutive frames and calculating the homography between them, restricted to a region of interest on the road plane. The resulting homography can be decomposed to obtain the normal vector component that corresponds to the change of road orientation in the observed scenario. The road surface plane is then defined as the plane perpendicular to this normal vector. Our central assumption is that when the vehicle approaches a curb or a sudden change in the road gradient, the offset parameter of the estimated plane will vary in a distinctive manner, serving as an indicator of these surface irregularities. We denote this offset as throughout the paper, which is explicitly visible in the decomposition of the homography

where is the signed distance of the plane from the camera origin.

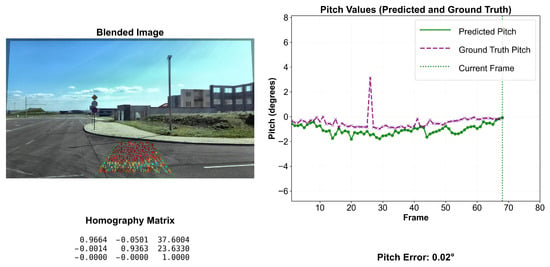

The homography-driven approach builds directly on the perception pipeline proposed in our earlier work [23] and forms a natural extension of it. The algorithm is visualized during runtime in Figure 1. In the present study, we retain the general structure of the pipeline while incorporating several modifications that adapt it to the specific requirements of road surface change detection. The details of these modifications are described in Section 2.3, where we outline the changes introduced to both the feature extraction stage and the region of interest selection. These refinements ensure that the homography decomposition remains robust to noise and more sensitive to small but safety-critical variations in the underlying road plane geometry.

Figure 1.

A snapshot of the algorithm during runtime is presented. On the left, the inter-frame homography visualization is shown together with the robust AI-based image matches within the region of interest, and the corresponding homography matrix solution is displayed below. The matched point pairs are color-coded by matching confidence (light: low confidence, dark: high confidence). On the right, the pitch derived from the road surface normal is plotted continuously as the sequence progresses.

2.1. Dataset

Testing our hypothesis required datasets that included the necessary sensor modalities along with accurate calibrations to support both our algorithm and ground truth generation. While we surveyed several publicly available datasets, many of which contain urban driving scenarios, none were found to provide scenarios that are highly relevant to the conditions identified in our study, namely, situations in which the vehicle approaches a curb or road edge directly.

To evaluate our approach in the scenarios mentioned previously, we collected and pre-processed our own dataset. Data acquisition was performed using a Lexus 350h vehicle customized for autonomous driving and data collection tasks and equipped with multiple sensors, including cameras, LiDARs, GPS, and a high-performance on-board x86 computer. For our experiments, we specifically used a front-facing ZED2i camera, a 64-channel Ouster OS2 LiDAR, and their corresponding calibrations. The dataset also includes IMU, GPS, and pose information, with pose data provided from two independent sources. The data was primarily recorded at the ZalaZONE proving ground, with additional sequences collected around Széchenyi István University. The complete dataset is publicly available at the link provided in Section 2.1.

Our dataset also provides the extrinsic calibration matrix between the LiDAR and the camera, together with the camera intrinsic matrix. The LiDAR coordinate system follows a right-handed convention with the positive x-axis oriented forward, while the camera coordinate system is also right-handed but adopts the computer vision convention, where the positive z-axis points forward.

The front-facing ZED2i camera operated at a resolution of 2208 × 1242 pixels (2K mode) with a polarized 4 mm lens, capturing images at 10 Hz. The 64-channel Ouster OS2 LiDAR was configured in a below-horizon setup and mounted on the same roof rack, to the right of the camera to minimize occlusion. Both sensors ran at 10 Hz during data acquisition, and all frames were processed for each recording. Although the sensors were not synchronized with a hardware trigger, the recordings were largely synchronized. On top of that, a software synchronization module aligned data streams by selecting the closest timestamps between the camera and LiDAR measurements, ensuring a maximum temporal offset below 80 ms. During the recordings, the vehicle maintained an average speed of approximately 20 km/h under human control, and the perception algorithms predicted terrain geometry up to about 9 m ahead.

The inertial measurement unit used in the experiments is a MicroStrain 3DM-GX5 IMU, which is mounted on top of our 128-channel Ouster OS2 LiDAR. The IMU is operating at 100 Hz and it is a direct input for the LIO-SAM [24] inertial odometry algorithm alongside with the 128-channel LiDAR. We also used a NovAtel PW7720E1-DDD-RZN-TBE-P1 dual-antenna RTK-capable GPS sensor to verify the validity of the inertial odometry algorithm.

2.2. Ground Truth Generation

To generate ground truth image-based curbs, edges and sudden road gradients, we required a method capable of providing the road plane of the selected region and its surface normal ahead of the vehicle with high accuracy and stability. To achieve this, we employed a 64-channel Ouster OS2 LiDAR sensor, which delivers precise 3D measurements of the environment. This choice was motivated by our aim to establish a ground truth based on direct physical measurements rather than estimations, thereby enabling a more reliable comparison with our algorithm.

Since the LiDAR measurements are highly reliable, a straightforward approach is sufficient for estimating the road plane. For this purpose, we employ the RANSAC algorithm [25] to extract the road surface from the LiDAR point cloud. Prior to plane fitting, outliers are removed using a Local Outlier Factor approach, which identifies sparse or inconsistent points based on local neighborhood density and Euclidean distance. To ensure temporal stability, a spike-suppression filter is employed that maintains a running history of estimated normals and rejects sudden deviations in the normal direction. In our experiments, we have used a maximum of 1000 iterations. The distance threshold was 0.02 m and the spike supression was intialized with a window size of 5.

To ensure that only points corresponding to the road surface ahead of the vehicle are used, the point cloud is filtered by selecting a predefined region of interest. The selected region corresponds exactly to the physical area used by our image-based algorithm, ensuring that the ground truth remains valid for this exact image region. The conditions for region selection are detailed in Section 2.

The two sensors are aligned through extrinsic calibration to obtain the transformation matrix between them. This matrix is then used to transform the point cloud into the image frame, after which the camera model projects the points onto the image plane. The projected points correspond directly to the pixels on which they lie.

2.3. Architecture

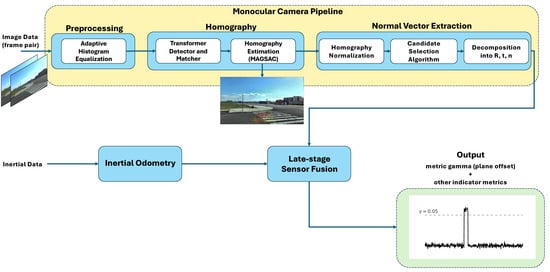

The proposed architecture (Figure 2) builds upon an algorithm we previously developed and presented at its core, which forms the foundation of the current work. It provides a stable framework while allowing us to investigate how small but critical modifications affect road surface geometry prediction performance, which is an important challenge when dealing with sudden changes at such a small scale (e.g., road curbs and edges). The architecture takes as input consecutive image pairs together with IMU-derived pose data that corresponds to the timestamp of the latest frame. From these inputs, it produces two main outputs: the road surface normal estimated through image-based homography and the corresponding pitch angle derived from this normal. Both outputs serve as the basis for calculating indicators of sudden gradient changes, such as the plane offset, which are essential for detecting features like curbs and road edges.

Figure 2.

Our architecture for detecting curbs and sudden road surface gradient changes. The architecture is a slightly modified version of the architecture we proposed earlier in [23].

The architecture is fundamentally image-based, with its core components dedicated to extracting and processing visual features in order to capture changes in the road surface. These image-based estimates are then complemented by a late-stage sensor fusion step with odometry, ensuring that the results are consistent with the physical world. This step is crucial because it guarantees that an incline is interpreted as an incline relative to the vehicle’s initial frame, rather than being treated as a flat surface in a purely local reference frame. At the heart of the system lies the matcher, which detects even weak geometric features in a highly robust manner. This robustness is essential, as missing small yet critical changes in the road profile, such as the onset of a curb would undermine the purpose of the algorithm. By building on this reliable matcher, subsequent calculations can be performed with greater confidence, a property that could also be illustrated through confidence plots. Our earlier algorithm for road surface orientation incorporated constrained interpolation via SLERP (Spherical Linear Interpolation) [26], which improved temporal stability by smoothing the normal estimates. However, while this smoothing helps mitigate noise, it also suppresses smaller but meaningful variations, making the detection of curbs and sharp edges considerably more difficult.

On the image-based side of the architecture, the core operation is the calculation of the inter-frame homography, from which our key indicator metrics are derived detailed in Section 3.1. The algorithm processes consecutive image frames from the camera data stream, each of which is first passed through a pre-processing module designed to rectify the images and enhance local contrast, for example, using Adaptive Histogram Equalization [27] to facilitate more reliable matching. Feature correspondences are then established using a recently published transformer-based matcher called EfficientLoFTR [28], which is particularly effective at handling weak matches. In all experiments, the publicly released pretrained model provided by the authors is employed. A comprehensive description of the network architecture, training procedure, and implementation details is presented in the original publication. This capability is essential for road environments that lack strong, easily detectable features such as lane markings. The resulting matches, filtered by a predefined region of interest, are subsequently used by a MAGSAC-based [29] plane-estimation module to compute the homography between the two frames. MAGSAC replaces the fixed inlier-threshold of RANSAC with a noise-marginalized scoring scheme, yielding more reliable model estimates in low-texture regions and reducing the sensitivity to threshold tuning. The estimated homography is then normalized to remove the influence of the camera intrinsic matrix and to prepare it for our custom candidate selection algorithm. Candidate selection is a necessary step because a homography does not correspond to a unique rigid motion. Ambiguities arise from sign indeterminacies and the quadratic nature of the decomposition equations. Since not all mathematical solutions are physically plausible, the algorithm constrains the possible solutions (typically four) and selects the valid one. The ambiguities introduced by the homography decomposition are resolved by enforcing a set of physically grounded constraints that eliminate solutions incompatible with plausible road geometry. Candidate solutions whose forward translation is non-positive are discarded, since they imply motion behind the camera. The surface normal is then constrained component-wise: lateral deviations are limited by requiring ( < 0.1), vertical deviations must satisfy ( < −0.9), and the normal’s depth component is restricted to the interval (−0.3 0.3), which excludes vectors that become nearly parallel to the road surface or flip direction under steep inclination or declination. After these geometric filters, the remaining normals are compared against a reference deviation vector using an angular threshold of (). Candidates exceeding this deviation are rejected. This procedure ensures that only physically meaningful, orientation-consistent normals are retained. All constraints and outputs follow standard computer-vision conventions, with a right-handed coordinate system in which the Z-axis points forward along the optical axis, the X-axis to the right, and the Y-axis downward. After this step, the homography is decomposed, and the road surface normal vector is extracted, implicitly defining the best-fitting local plane for the current road region.

We obtain vehicle pose independently of vision using inertial odometry. A LIO-SAM–based module [24] fuses MicroStrain IMU and LiDAR data through IMU pre-integration and a factor-graph optimizer to produce a timestamped pose stream containing position and orientation. In parallel, a dual-antenna NovAtel RTK GNSS receiver provides a second, independent pose stream. The odometry source is modular and swappable without changes to the vision module (see Section 2.1). For each camera frame, we select the closest odometry orientation at that timestamp and apply a late-stage, deterministic coordinate transformation to the homography-derived road normal. This late fusion is deliberately loose-coupled, since the vision system never feeds back into the odometry, and no filtering is performed over the normals in this curb detection version of our algorithm. The fusion acts purely as a frame transformation that aligns the visual estimate to a physically meaningful reference tied to the vehicle (or world), ensuring temporal consistency while keeping the roles disjoint. Namely, odometry provides orientation, and vision provides the road-plane normal.

This fusion step is crucial because the homography decomposition yields a road-plane normal in the camera frame. Left in that frame, the vector is dominated by the camera’s mounting and the gravity relative to the camera, so its absolute direction appears upward and carries little terrain information. As a result, only relative changes are noticeable, for example, true slope variations and ego-motion (pitch or roll) of the vehicle between frames. By re-expressing the normal in a physically meaningful frame (vehicle or world) using the calibrated extrinsics and current odometry, we remove the camera-mount bias and disentangle ego-motion from terrain. The outcome is an absolute, comparable normal that reflects the true road grade rather than just an upward-facing default.

3. Results

In this section, we present the experimental results of our approach to detecting curbs, road edges, and sudden steep gradient changes using homography derived from AI-based geometric matching. The results are organized into two subsections. The first subsection explains the evaluation metrics, while the second subsection provides both qualitative and quantitative evaluations, distinguishing between success and failure cases and describing their characteristics in detail.

As discussed in Section 2.1, no publicly available datasets capture the specific scenarios required to evaluate our hypothesis. To address this gap, we collected our own dataset under controlled conditions. The dataset comprises six targeted scenarios. Two involving speedbumps and four involving the vehicle approaching a road curb directly from different angles. The objective of these recordings was not to achieve broad coverage of urban driving situations, but rather to isolate and reproduce the sudden road surface gradient changes, such as curbs and road edges that are central to our investigation. By designing and recording these six scenarios under ideal conditions, we ensured that the dataset was sufficiently representative to rigorously test the viability of our method for predicting abrupt surface gradient transitions.

3.1. Metrics

In order to thoroughly assess the feasibility of detecting curbs and sudden gradients, we systematically examined the data and identified features that could exhibit significant measurable variations. Based on these observations, we formulated and established a set of evaluation metrics designed to rigorously validate our hypothesis. The metric gamma

represents the camera’s translation along the ground plane normal in metric scale, obtained by scaling the scale-free with the known camera height. Here, and denote the camera’s perpendicular distances to the ground plane in two consecutive frames, is the translation vector between the camera centers, and is the unit normal of the ground plane in the second frame. It serves as the primary cue for detecting vertical discontinuities, with a fixed threshold indicating potential curb or step events. We use 0.05 m as the detection threshold throughout. This is complemented by the pitch change (), derived from consecutive frame rotations, which captures changes in camera inclination. The pitch angle is derived from the ground-plane normal as

computed separately for both frames, after which their difference yields the change. The pitch change together with , it can help distinguish between vertical offsets and gradual slope transitions. The signed change in ground plane normal () provides an additional orientation-based cue by measuring the signed angular deviation between successive unit normals with respect to the camera’s lateral axis. The scale-free gamma ()

is the unitless version of the measure, computed alongside it to provide a scale-independent translation measure, which is useful for comparing scenes without requiring metric calibration. Finally, the mean reprojection error

is calculated to assess the geometric consistency of the estimated homography, ensuring that detected changes originate from a valid and stable homography estimation rather than from mismatches or poor feature tracking. Here, denotes the set of inlier correspondences, are the homogeneous source points in the first frame, are their corresponding image points in the second frame, is the estimated homography, and represents the dehomogenization operator that converts homogeneous coordinates to pixel coordinates.

Based on our experiments, the most effective indicators of significant plane changes were the metric in combination with the pitch angle. In addition, the mean reprojection error provided a valuable measure of confidence in the correctness of the estimated plane, ensuring that the detected changes arose from a valid homography decomposition rather than from spurious matches.

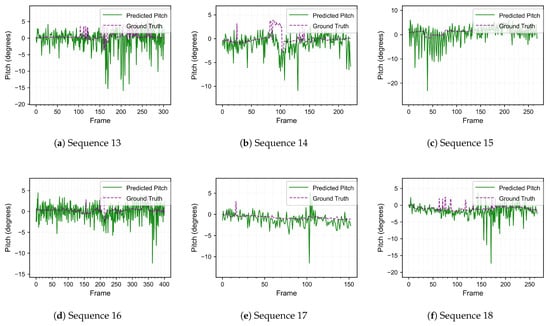

3.2. Performance Evaluation

We analyze six targeted sequences (four curbs, two speed bumps) to answer a yes/no feasibility question: do homography-derived cues exhibit anticipatory signatures before the vehicle reaches a small step? Success is defined as an excursion of the -metric beyond 0.05 m aligned with the approach to the discontinuity, corroborated by low reprojection error and synchronized visual inspection. Before discussing the detailed results, it is useful to first examine the general characteristics of the resulting signals, as this provides the context for interpreting individual cases. Based on the pitch plot of sequence 13 (Figure 3), two distinct forms of response can be observed. The first occurs when large values appear in advance of a curb, where the rapid change detected through the homography serves as an early marker of the upcoming curb jump. The second corresponds to large excursions that arise after the curb has been crossed, which are not linked to the road geometry itself but rather to the suspension system’s dynamic response to the impact. These phenomena appear in several sequences, and distinguishing between the two cases is essential, as we are interested in predicting sudden road gradient changes rather than detecting them retrospectively.

Figure 3.

Pitch results for the six test sequences (13–18). The pitch values are derived from the estimated road surface normal obtained through homography computation. For curb-detection purposes, the filtering normally applied in the pitch-estimation pipeline was disabled, which improves sensitivity to curb geometry but reduces the accuracy of the pitch itself. This adjustment rendered the ground-truth pitch unsuitable for direct comparison in this context, but the unfiltered pitch estimates remain effective for detecting curb geometry.

We began from the hypothesis that small curb jumps and sudden changes in road gradient can be identified from monocular images, building on the assumption introduced in the beginning of this paper that stable image-based homography, when derived from robust geometric correspondences, provides a viable means for predicting road surface discontinuities such as curbs and edges. The central aim of this work is therefore to verify this hypothesis through quantitative analysis. To achieve this, we employed the set of evaluation metrics defined in Section 3.1. For each recorded sequence, particular emphasis was placed on the gamma metric and on the pitch values obtained from the homography-derived road surface normal. These two measures form the basis of our investigation into whether the observed signal excursions carry statistical significance that could confirm the predictive power of the method. Alongside this analysis, we examined the mean reprojection error on a frame-by-frame basis to ensure that the underlying homographies were sufficiently accurate to serve as a foundation for our calculations. In addition to these primary metrics, we extended our investigation to the homography matrix itself. By analysing each of its nine individual components, we sought to determine whether any of them exhibited systematic behaviour that could further support the prediction of curb jumps or sudden gradient changes ahead.

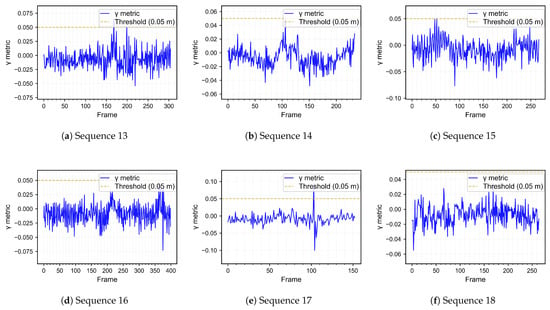

As previously mentioned, we collected our own dataset and recorded six distinct sequences to evaluate the performance of the proposed algorithm. In the following section, each sequence is examined individually in order to provide a detailed account of the results and highlight the differences between specific cases. Figure 4 presents the gamma metric for all sequences, which serves as one of the primary indicators of sudden changes in the road surface. Complementing this, Figure 3 shows the pitch plots derived from the homography-based road surface normal, providing additional insight into the geometric characteristics of the encountered curb jumps and gradient changes. Taken together, these figures provide the general context for interpreting the signals, while the following subsections examine each of the six recorded sequences in detail, discussing how the proposed metrics behave in practice and how they support or challenge our hypothesis.

Figure 4.

The metric gamma (plane offset) figures for each of the six test sequences (Sequences 13–18). The threshold is specified in centimeters. Please note that the actual curb height might differ, this can be solved with more strict calibration.

For clarity, two things should be noted. First, that the sequences are numbered from 13 to 18, as they were recorded together with other sequences in our dataset. This numbering is used consistently throughout the paper. Second thing, the algorithm was evaluated without filtering, which naturally introduced stronger oscillations and inaccuracies in the resulting signals. However, this decision was intentional, as leaving the signals unfiltered allowed us to preserve fine-grained variations that proved informative for identifying curb events. Although LiDAR-based ground truth calculations were employed, their contribution turned out to be limited. In practice, examining the image sequences together with the plotted metrics provided clearer insight into the occurrence of curb jumps and gradient changes. This is an acceptable outcome in a scientific setting, since the value of ground truth ultimately lies in how effectively it supports interpretation and validation of the proposed method. In our case, the visual alignment of metric excursions with curb events in the image data offered a more direct and reliable basis for analysis than the LiDAR-derived reference alone.

If we take a closer look at the gamma metric plots in Figure 4, it becomes clear that several of the six recorded sequences exceed the threshold defined in Section 2. When examining Sequences 13, 14, and 15, it can be observed that all three cross the defined threshold at their first significant spikes, which can be interpreted as an indication of the upcoming curb or sudden gradient change. A notable characteristic of these events is that the excursions appear as a single spike, or at most two closely aligned spikes, occurring almost precisely when the region of interest reaches the midpoint of the plane change. This temporal alignment strengthens the interpretation that these spikes correspond to the shift in plane height as the vehicle approaches the curb. Across these sequences, the overall mean reprojection error remained around 0.07 pixels, with the highest value reaching 0.10 pixels, which indicates that the homography estimation remained stable throughout the runtime of the algorithm. The moment of the curb-induced jump is further illustrated by the image pair on which the homography was computed, as shown in Figure 5, providing a visual confirmation of the detected event. Sequence 16 also involved a curb event, but in this case the algorithm did not produce a clear detection. The most likely explanation is that the curb height was too small to generate a strong enough signal in the selected metrics. Nonetheless, this case highlights an opportunity for refinement, as with further development the method may be extended to provide reliable detections even for lower curbs, complementing the successful results demonstrated in Sequences 13, 14, and 15.

Figure 5.

Inter-frame visualization of the homography transformation at the moment the -metric exceeds the 0.05 m threshold, shown together with the region of interest containing the feature matches. The red and green particles visualize the confidence levels of the AI-based image feature matches (light: low confidence, dark: high confidence).

Turning to Sequences 17 and 18, which both involve speedbumps, the gamma metric plots reveal that these events are not detectable with the current version of our algorithm. This limitation, however, may be addressed through further improvements. The most plausible explanation for the lack of detection lies in the geometric nature of the obstacle. In the case of curbs, two distinct planes are present, and as the majority of feature correspondences shift from the lower to the higher plane, the homography reflects a pronounced change at the inflection point. By contrast, speedbumps are relatively short along the longitudinal axis of the vehicle and do not produce a comparable plane shift. As a result, the algorithm is unable to register a distinct signature, which explains the absence of detection in these sequences.

A closer examination of the pitch plots reveals a signal characteristic that mirrors the behaviour observed in the gamma metrics. Although no explicit threshold was applied here, since thresholding is specific to the gamma metric, the pitch values nevertheless exhibit significant spikes at the exact same points where the gamma plots spike and cross their defined threshold. Because the homography estimation underlying both metrics is identical, the mean reprojection error remains unchanged between the two cases. Taken together, these observations demonstrate that curb detection is not only viable but also predictive when the road surface presents a longer plane change, as in the case of curbs and road edges.

Our findings on the behaviour of the gamma metric are summarized in Table 1. The first row reports the highest gamma value detected for each sequence, while the second row indicates whether this value exceeded the predefined detection threshold. This tabular overview provides a concise comparison across sequences and complements the detailed per-sequence analysis presented above.

Table 1.

This table summarizes the peak values of the -metric (plane offset) together with the sequence types and highlights whether they exceeded the 0.05 m threshold. Aggregating across classes, curbs are detected in 3/4 sequences, while both speed-bump sequences remain below threshold under the single-plane model.

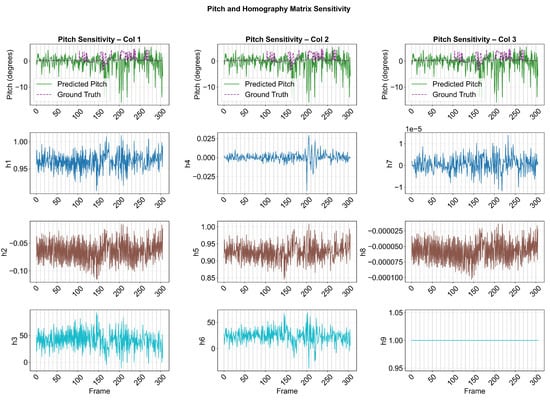

Beyond evaluating the gamma and pitch metrics together with the reprojection error, we also investigated the homography matrix itself to better understand the underlying behaviour of the transformation. As an illustrative example of this sensitivity analysis, we plotted each parameter of the homography matrix in a grid-like structure, where the arrangement of the plots mirrors the layout of the matrix itself. This visualization makes it easier to assess how individual components behave over time. The elements in the upper-left 2 × 2 block correspond to the affine part of the transformation, which primarily captures rotation, scaling, and shear. The entries in the rightmost column represent translation along the image axes, while the bottom row encodes the projective terms that account for perspective effects. By presenting the parameters in this structured form, we can directly observe whether specific components exhibit systematic variations that may correlate with the presence of curb jumps or sudden gradient changes.

In this analysis, several parameters of the homography matrix, such as and , exhibited correlations of approximately 0.3 with the pitch plots and, consequently, with the curb jumps. While these initial findings do not yet establish a definitive link, they highlight promising directions that merit deeper investigation, and we intend to explore these relationships more thoroughly in future work (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Homography sensitivity analysis for Sequence 13. Each subplot shows the parameter values for consecutive frame pairs, arranged in the grid according to the corresponding position in the homography matrix.

To contextualize the computational feasibility of the proposed pipeline, we report the average per-frame runtime of its main components together with the hardware configuration used for evaluation. This measurement supports the claim that the method remains cost-efficient and suitable for camera-centric systems. The breakdown in Table 2 summarizes the processing time for feature matching, homography estimation, and IMU fusion.

Table 2.

Average per-frame runtime and module-wise breakdown. The method was evaluated at on an Intel i9-11900 CPU (Intel, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU (NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

4. Discussion

Before discussing the results in detail, it is important to note that this work is a feasibility study rather than a performance benchmark. We test whether monocular homography contains predictive geometric signal for small curb-height plane changes on a focused set of recordings. Because our objective is detectability via geometry rather than appearance classification, comparisons to object-detector baselines are orthogonal and were not feasible in this study.These results warrant broader, statistically powered validation and motivate model extensions (e.g., piecewise/multi-plane algorithms).

The results collectively indicate that image-based curb detection is feasible even when the geometric discontinuity is small. Across Sequences 13–15, the -metric crosses the predefined 0.05 m threshold at the first significant spike, and the pitch plots exhibit coincident excursions, while the mean reprojection error remains low throughout. Together, these observations support the claim that a stable homography estimated from robust geometric correspondences carries predictive signal for sudden road surface gradient changes such as curbs and road edges, and that the recovered transformation is geometrically faithful enough to be actionable.

A careful distinction between anticipatory excursions that precede the curb and post-event excursions driven by suspension dynamics is essential for interpretation. We deliberately retained unfiltered signals to preserve these fine-grained behaviors, accepting higher oscillation as the cost of temporal specificity. Although LiDAR-based reference data was employed, frame-accurate alignment of events benefitted from synchronized visual inspection of the image sequences and metric plots. In this context, the reference provides a reliable scaffold for interpreting method behavior rather than a substitute for sequence-level event localization.

For speedbumps in Sequences 17 and 18, detection was not achieved with the current pipeline. The most plausible explanation is geometric. Curbs create a transition between two planes and induce a strong inflection as features migrate to the higher plane, whereas speed bumps are short along the vehicle’s longitudinal axis and do not produce a comparable plane change in the homography. As a result, both and pitch signatures are weaker. The homography-level sensitivity analysis offers additional insight into these mechanisms: several matrix elements, including and , exhibit moderate correlations of about 0.3 with the pitch signal and with curb events. While not definitive, these relationships point to specific components of the transform that may carry predictive information and justify deeper study.

The evidence shows overall, that a monocular, geometry-driven approach can reliably capture subtle plane changes and road gradients and is therefore a viable basis for safety-critical detection tasks. Building on this, the forward path is to consolidate the predictive behavior already evident in curb sequences and extend it to shorter structures through targeted refinements. Temporal filtering of homography-derived normals to enhance anticipatory signatures without suppressing informative excursions, multi-plane decomposition or piecewise homographies to capture local transitions over small longitudinal extents, adaptive regions of interest that track the approach to likely discontinuities and confidence weighting that integrates mean reprojection error into the decision logic. Finally, the dedicated dataset we assembled for small road surface discontinuities in diverse urban scenes enables principled evaluation of these refinements and provides a foundation for broader statistical assessment of generalization once augmented with additional low-curb and speedbump scenarios.

5. Conclusions

This study examined whether homography-derived geometric cues from a single, higher-mounted monocular camera can anticipate small, curb-height discontinuities. A targeted evaluation on six recordings (four curbs, two speed bumps) indicates that the proposed geometry-first pipeline provides reliable anticipatory signatures for curbs. Three of four curb approaches exceeded the 0.05 m detection threshold with low reprojection error, while speed bumps, which violate the single-plane assumption along the approach, were not detected. These results constitute feasibility evidence that monocular homography can encode centimeter-scale plane changes relevant to curb detection, without relying on appearance cues or object-detector heuristics. The present findings instead delineate where a single-plane geometric model works (curbs) and where it breaks down (short, longitudinal structures such as speed bumps), providing a clear target for model refinement.

Future work will expand recordings to parking-style scenarios under varied illumination, materials, and motion profiles, with sensor remounting to match typical parking geometry. The data protocol will be adapted to enable fair, quantitative comparisons to appearance-based and stereo baselines, including frame-level labels and operating-point sweeps for threshold-free metrics. On the modeling side, piecewise/multi-plane reasoning and improved temporal fusion will be explored to capture short, non-planar obstacles while preserving the anticipatory advantages observed for curbs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M., A.B. and T.S.; methodology, N.M. and Z.R.; software, N.M.; validation, N.M.; formal analysis, N.M.; investigation, N.M.; resources, N.M.; data curation, N.M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M.; writing—review and editing, N.M., A.B., Z.R. and T.S.; visualization, N.M.; supervision, T.S. and A.B.; project administration, N.M.; funding acquisition, N.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The publication was prepared within the framework of the Széchenyi István University project VHFO/416/2023-EM_SZERZ, entitled “Preparation of digital and self-driving environmental infrastructure developments and related research to reduce carbon emissions and environmental impact (Green Traffic Cloud)”, which provided support for N.M. This research was also supported by the European Union within the framework of the National Laboratory for Autonomous Systems (RRF-2.3.1-21-2022-00002) and by through NKFIH STARTING 149552 and K139485 NKFIH grants, which supported Z.R. In addition, Z.R. acknowledges the support of the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (MTA). This research was further supported by the Hungarian National Science Foundation (NKFIH OTKA) No. K139485, which provided support for T. Szirányi.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The collected research data can be found at https://norbertmarko.github.io/curb_detection/ (accessed on 30 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gallo, O.; Manduchi, R.; Rafii, A. Robust Curb and Ramp Detection for Safe Parking Using the Canesta TOF Camera. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Anchorage, AK, USA, 23–28 June 2008; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Y.; Jia, W.; Sun, M.; Tang, Y. Obstacle Classification and 3D Measurement in Unstructured Environments Based on ToF Cameras. Sensors 2014, 14, 10753–10782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.; Park, J.; Byun, J.; Yu, W. Robust Ground Plane Detection from 3D Point Clouds. In Proceedings of the 2014 14th International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems (ICCAS), Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea, 22–25 October 2014; pp. 1076–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. LIDAR-based Road and Road-edge Detection. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium, San Diego, CA, USA, 21–24 June 2010; pp. 845–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, M.W.; Nishihata, T.; Brooks, C.A.; Iagnemma, K. Ground Plane Identification Using LIDAR in Forested Environments. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Anchorage, AK, USA, 3–7 May 2010; pp. 3831–3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Leung, T.; Medioni, G.G. Real-time Staircase Detection from a Wearable Stereo System. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR 2012), Tsukuba, Japan, 11–15 November 2012; IEEE Computer Society: Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 3770–3773. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarze, T.; Lauer, M. Robust Ground Plane Tracking in Cluttered Environments from Egocentric Stereo Vision. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Seattle, WA, USA, 26–30 May 2015; pp. 2442–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusupati, U.; Cheng, S.; Chen, R.; Su, H. Normal Assisted Stereo Depth Estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Se, S.; Brady, M. Ground Plane Estimation, Error Analysis and Applications. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2002, 39, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, L.M.; Guerrero, J.A.; Romero, G. Road Curb Detection: A Historical Survey. Sensors 2021, 21, 6952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oniga, F.; Nedevschi, S. Polynomial Curb Detection Based on Dense Stereovision for Driving Assistance. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC), Madeira Island, Portugal, 19–22 September 2010; pp. 1110–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, V.S.K.P.; Adarsh, S.; Ramachandran, K.I.; Nair, B.B. Real Time Detection of Speed Hump/Bump and Distance Estimation with Deep Learning using GPU and ZED Stereo Camera. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Advances in Computing and Communications (ICACC), Procedia Computer Science, Kochi, India, 13–15 September 2018; Volume 143, pp. 988–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragon, R.; Van Gool, L. Ground Plane Estimation Using a Hidden Markov Model. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 4026–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, Y.; Weng, X.; Li, X.; Kitani, K. GroundNet: Monocular Ground Plane Normal Estimation with Geometric Consistency. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, New York, NY, USA, 21–25 October 2019; pp. 2170–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, B. Homography-based Ground Detection for a Mobile Robot Platform Using a Single Camera. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Orlando, FL, USA, 15–19 May 2006; pp. 4100–4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klappstein, J.; Stein, F.; Franke, U. Applying Kalman Filtering to Road Homography Estimation. In Proceedings of the ICRA 2007 Workshop: Planning, Perception and Navigation for Intelligent Vehicles, Atlanta, GA, USA, 14 April 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Arróspide, J.; Salgado, L.; Nieto, M.; Mohedano, R. Homography-based Ground Plane Detection Using a Single On-board Camera. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2010, 4, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorr, M.; Niehsen, W.; Stiller, C. Robust Ground Plane Induced Homography Estimation for Wide Angle Fisheye Cameras. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Dearborn, MI, USA, 8–11 June 2014; pp. 1288–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.; Kageyama, Y.; Akashi, T. Curb Detection Using a Novel Deep Learning Framework Based on YOLO-v2. IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2022, 17, 1321–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta-López, J.E.; Morales-Viscaya, J.A.; Lázaro-Mata, D.; Villaseñor Aguilar, M.J.; Prado-Olivarez, J.; Pérez-Pinal, F.J.; Padilla-Medina, J.A.; Martínez-Nolasco, J.J.; Barranco-Gutiérrez, A.I. Speed Bump and Pothole Detection Using Deep Neural Network with Images Captured through ZED Camera. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruseruka, C.; Mwakalonge, J.; Comert, G.; Siuhi, S.; Ngeni, F.; Anderson, Q. Augmenting Roadway Safety with Machine Learning and Deep Learning: Pothole Detection and Dimension Estimation Using In-Vehicle Technologies. Mach. Learn. Appl. 2024, 16, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, L. Annotation-Free Curb Detection Leveraging Altitude Difference Images. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2409.20171. [Google Scholar]

- Marko, N.; Rozsa, Z.; Ballagi, A.; Sziranyi, T. Monocular Ground Normal Prediction for the Road Ahead. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2025, in press.

- Shan, T.; Englot, B.; Meyers, D.; Wang, W.; Ratti, C.; Daniela, R. LIO-SAM: Tightly-coupled Lidar Inertial Odometry via Smoothing and Mapping. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24 October 2020; pp. 5135–5142. [Google Scholar]

- Fischler, M.A.; Bolles, R.C. Random Sample Consensus: A Paradigm for Model Fitting with Applications to Image Analysis and Automated Cartography. Commun. ACM 1981, 24, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemake, K. Animating Rotation with Quaternion Curves. Comput. Graph. 1985, 19, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizer, S.M.; Amburn, E.P.; Austin, J.D.; Cromartie, R.; Geselowitz, A.; Greer, T.; ter Haar Romeny, B.; Zimmerman, J.; Zuiderveld, K. Adaptive Histogram Equalization and Its Variations. Comput. Vision Graph. Image Process. 1987, 39, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, X.; Peng, S.; Tan, D.; Zhou, X. Efficient LoFTR: Semi-Dense Local Feature Matching with Sparse-Like Speed. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 21666–21675. [Google Scholar]

- Barath, D.; Matas, J.; Noskova, J. MAGSAC: Marginalizing Sample Consensus. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 10189–10197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).