Abstract

In the face of the urgent need for sustainable practices in the coal industry, we propose a novel green cut-and-fill mining method aimed at achieving material self-sufficiency and mitigating overburden subsidence. This method leverages the goaf roof as an in situ filling material, integrating long-wall caving mining efficiency with partial filling techniques. Through laboratory analog material modeling, numerical simulations, and structural mechanics modeling, we compare the performance of cut-and-fill mining and traditional caving mining methods. The results show that the cut-and-fill method offers more uniform and controlled deformation behavior. Specifically, vertical and horizontal displacements along 40 m survey lines are significantly reduced, with a maximum reduction on the order of millimeters, compared to caving mining. Furthermore, the floor stress concentration coefficient is lower, and the total number of fractures decreases, with shear fractures reduced by 8.8% and tensile fractures reduced by 66.9%. The gangue column in the cut-and-fill method effectively supports the goaf roof, preventing fracture formation and extending the deformation time. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the cut-and-fill method for subsidence control, suggesting its potential for achieving green and sustainable coal mining practices.

1. Introduction

Coal is one of the most important energy sources of industrial production, especially in China. However, the process of coal mining inevitably causes mining subsidence, causing serious environmental and social problems. At present, the traditional ways to control surface subsidence in coal mining mainly include partial mining, paste filling, overburden separation grouting, and fully mechanized gangue filling mining technology [1,2]. Partial mining can be divided into room-and-pillar mining and strip mining in general. The former belongs to the column mining system, which has been widely implemented in the United States, Australia, India, and South Africa for its applicability in flat-lying seams [3]. The latter, a form of short-wall mining system, is commonly practiced in European countries and has been extensively adopted in China, particularly for subsidence control under surface structures [4]. Paste filling by pumping is mainly composed of aggregate and cementitious materials. In order to reduce costs and protect the ecological environment, cementitious materials are mainly cement and fly ash, and the aggregate is generally coal gangue [3,4], according to Shaposhnik et al. [5]. Justification of Extraction of Ore Reserves under Bottom and in Pitwall Rock Mass Using Cut-and-Fill Method in Transition from Open Pit to Underground Mining in the Artemevsky Mine. Overburden bed separation grouting controls surface deformation by bed separation grouting 15~20 m behind the working face [6]. To enhance recovery while protecting the surface environment, researcher Ashok Jaiswal proposed a hybrid mining method involving partial extraction from underground coal mines. The concept of panel stability, rather than pillar stability, has been suggested for stability analysis of the proposed method of partial extraction [7]. On the basis of summarizing the technology of direct filling coal mining with gangue solid materials, Chinese scholars put forward the principle and method of fully mechanized solid filling mining which can adapt to the traditional fully mechanized coal mining technology, and systematically introduced the systematic layout, key equipment, and filling technology [8,9]. Backfill mining methods have been extensively researched and applied globally to mitigate mining-induced subsidence. For instance, room-and-pillar mining, widely used in the United States, Australia, and South Africa, and strip mining, commonly practiced in China and European countries, both support the overburden by leaving coal pillars [3,4]. Against this backdrop, the fully mechanized solid filling technology developed by Chinese scholars represents a significant advancement in this field [8,9]. The method proposed in this study aims to integrate the high efficiency of long-wall mining with the subsidence control benefits of backfilling, while simultaneously addressing the common international challenge of filling material sourcing.

Sometimes, two or more technologies are used in combination for the specific situation of the site. Guo et al. [10] analyzed the advantages and disadvantages of filling mining, strip mining, and overburden separation grouting strata control technology. According to the principle of load replacement, a new idea of three-step mining subsidence control of “strip mining-grouting filling consolidation goaf-remaining strip mining” was proposed. Ilie Onica [11] analyzed the ground surface subsidence phenomenon using the CESAR-LCPC finite element code of version 4. The modeling is made in the elasticity and the elasto-plasticity behavior hypothesis. Also, the time dependent analysis of the ground surface deformation was achieved with the aid of an especial profile function. Dai et al. [12] proposed a coordinated mining method of “mining-filling-retaining” combination of partial mining, partial filling and partial coal pillar, the layout of coal pillar, filling mining face and caving mining face and the principle of determining the size of mining, filling and retaining were given. Xu et al. [13,14] put forward the concept of partial filling mining and three partial filling mining technologies, the technical principle, design method, applicable conditions and application are introduced, respectively. Liu et al. [15] combined the advantages of room and pillar mining and paste filling mining, put forward the point pillar paste filling mining method, and introduced the implementation process of this method in detail, discussed the feasibility of this method. Ning et al. [16] mainly investigated the mechanical mechanism of overlying strata breaking and the development of fractured zones during close-distance coal seam group mining in the Gaojialiang coal mine. Furthermore, recent studies on room-and-pillar mining have addressed complementary phases of the mining lifecycle [17,18]. One study focused on primary mining, optimizing the chamber span to prevent local roof collapses for operational safety [17], while the other dealt with pillar recovery, modeling large-scale caving to predict and manage surface subsidence [18]. Together, they provided a complete ground control strategy, ensuring safety during excavation and controlling the consequences of final pillar extraction.

In summary, in order to effectively mitigate surface subsidence induced by coal mining, two primary methods are commonly employed. The first involves the utilization of external filling materials to backfill the mined-out area, while the second method entails leaving coal pillars to support the mined-out area [19,20,21]. Both approaches, however, exhibit inherent limitations. The former necessitates the procurement of additional filling materials, thereby often leading to escalated material costs and associated transportation expenses. Conversely, the latter results in the inefficient utilization of coal resources and is not conducive to the sustainable, long-term development of coal mines. Given these considerations, this paper predominantly centers on the current practice of filling mining, specifically addressing the challenge of inadequate filling materials encountered in the fully mechanized solid filling method. It proposes the concept of cut-and-fill mining within the goaf, offering a perspective aimed at effectively mitigating surface subsidence [22]. This paper expounds upon the fundamental principles and implementation procedures of cut-and-fill mining, placing a particular emphasis on the mining outcomes achieved through this method. This paper aims to evaluate the deformation and stress behavior of this approach in reducing surface subsidence and ensuring overall stability.

2. Methodological Overview

2.1. Basic Principles of Cut-and-Fill Mining

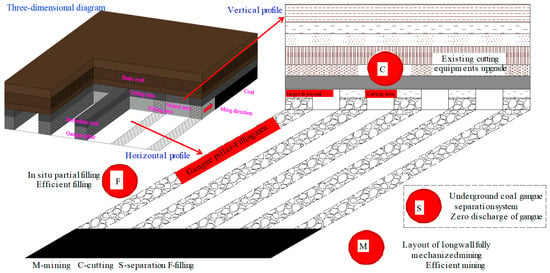

In order to realize the self-sufficiency of filling material, cut-and-fill mining processes the part (cutting area) of the goaf roof as in-situ (filling area) filling material, according to the distribution of the coal seam, the characteristics of the surrounding rock, etc. The scientific layout of the cutting area; the location and size of the filling area, relying on a complete set of integrated mining equipment which includes specially modified hydraulic supports; a roof cutting device; and a conveying system are all required to realize the partial filling of the goaf and to achieve the purpose of controlling surface subsidence.

Figure 1 shows the three-dimensional schematic diagram of the cut-and-fill mining working face. The cut-and-fill mining working face includes the coal mining face ahead of the hydraulic support, and the roof cutting and filling face behind the hydraulic support. The back roof cutting filling working face is divided into the roof cutting area and filling area, and the roof cutting area and filling area are arranged in sequence. The cutting device in the roof cutting area cuts the partial immediate roof and transports it to the adjacent filling area for concentrated and dense filling. With lateral restraint of the anchor bolt and metal mesh, the bearing structure of the gangue pillar and immediate roof is formed in the filling area, which plays the role of partial filling and achieves the effect of reducing subsidence.

Figure 1.

Integrated schematic diagram of cut-and-fill mining.

As shown in Figure 1, the cut-and-fill mining process includes the coal mining process, roof cutting process, and filling process, forming the process flow of mining, cutting, and filling. If considering underground coal gangue separation, filling can form another mode of the coal mining–cutting–separation–filling process. Cut-and-fill mining can integrate the high efficiency characteristic of long-wall caving mining with the operational simplicity of partial filling methods.

2.2. Existing Technical Basis Analysis

The origin of the idea based on the current advanced coal mining technology, including the “mining, separation, filling + X” coal mining and structural backfilling mining, as well as the higher requirements of filling mining, includes solving the source of materials, reducing the cost of filling, and so on.

2.2.1. “Mining, Separation, Filling + X” Coal Mining

After nearly 20 years of development, through the evolution of four generations of technology, the fully mechanized solid filling method has formed a new pattern of “mining, separation, filling + X”. The process of “mining, separation, filling + X” is shown in Figure 1. As for the goal that “X” represents what is hoped to be achieved, it can be specifically expressed as follows: mining, separation, filling + control settlement; mining, separation, filling + water-retaining mining; mining, separation, filling + fire prevention and impact prevention; and mining, separation, filling + gob-side entry retaining, etc. [9,10,23,24,25]. At present, “mining, separation, filling + X” coal mining has realized the parallelization of a mining and filling operation and the integration of mining and filling equipment. The main difficulties are the shortage of gangue materials and the limitation of filling scales.

The starting point of cut-and-fill mining is to realize the self-reliance of the filling materials and underground filling in situ, and to achieve the goal of reducing and controlling subsidence. It can provide a feasible solution to the current problems faced by “mining, separation, filling + X”. The coal mining technology, filling technology, and possible underground coal gangue separation in cut-and-fill mining are basically consistent with the current fully mechanized solid filling method, which can be used as the basis of cut-and-fill mining. Based on its development history and the current strong manufacturing industry as a support, it is possible to further transform the existing filling support to meet the needs of cut-and-fill mining.

2.2.2. Structural Backfilling Mining

Structural backfilling entails the concurrent construction of a “backfill body-direct roof” composite load-bearing structure during the coal mining process, as shown in Figure 2 [26]. This approach aims to minimize the demand for backfilling materials and enhance the efficiency of backfilling operations, while facilitating the further development and utilization of underground coal mining spaces. Structural backfilling mining is also currently in the stage of indoor research, and it involves partial backfilling operations before the direct roof breakage in the goaf area.

Figure 2.

Underground integrated structural backfill system [25].

The main difference is that cut-and-fill mining adopts the cutting broken gangue dense filling (with a target uniaxial compressive strength typically in the range of 0.5~1.5 MPa) to achieve the effect of controlling subsidence rate and reducing subsidence. In contrast, structural backfilling has higher requirements on the strength of the material (often requiring a strength of 5~15 MPa or more, usually achieved by adding cementitious materials) to ensure the stability of the composite structure for future underground space utilization. and it is necessary to ensure the stability of the immediate roof to provide available underground space for the future. While cut-and-fill mining and structural backfilling share certain similarities, the direct roof especially mandates that no breakage occurs prior to treatment. The research methods and findings associated with structural backfilling mining can serve as a theoretical and conceptual foundation for advancing cut-and-fill mining research, expediting its progress in the field.

In summary, by relying on the current advanced related coal mining technology level and strong manufacturing capacity, it is possible to complete the research and development of related equipment and technology for cut-and-fill mining and achieve the goal of cut-and-fill mining.

3. Simulation Analysis

Through similar material simulation and numerical simulations, a comparative analysis was conducted on the overlying rock failure patterns, displacement stress characteristics, and mining-induced fracture distribution patterns between cut-and-fill mining and caving mining.

3.1. Similar Simulation Experimental Plan

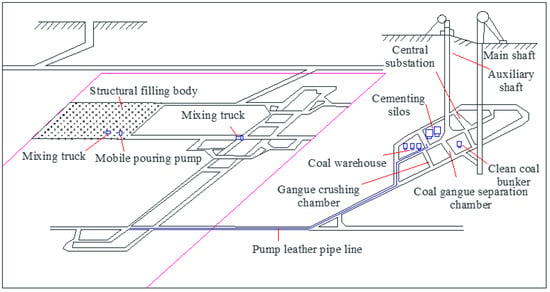

In the studied coal mine of China, the strike length of the 22 mining area was approximately 1629.5 m, and the dip length was around 4132.3 m with an average thickness of about 4 m. The coal seam was situated at an average depth of around 100 m, with a dip angle ranging from 1° to 5°. The coal seam has a simple structure, as shown in Figure 3, and the roof and floor of the coal seam mostly consist of fine-grained sandstone and sandy mudstone. Through the calculation of the load-bearing capacity of each rock layer in the coal mine, it was determined that the main critical layer is R6, composed mainly of medium-grained sandstone. The mechanical properties of this layer, including an elastic modulus of 15.8 GPa and a cohesion of 4.5 MPa, were used in the calibration of the numerical model.

Figure 3.

Coal-rock occurrence and similar simulation scheme.

Similar materials such as sand, calcium carbonate, gypsum, and water were used to create a model following the principles of similar materials and similarity criteria. The size similarity ratio was 1:100. The laying length was 190 cm (representing 190 m in the field), width was 22 cm (representing 22 m in the field), and the laying height was 134 cm (representing 134 m in the field). The mix ratio was determined based on the compressive strength of the rock layers to be simulated.

As shown in Figure 3, to facilitate the cutting of the roof, a cutting-top board was embedded at the bottom of the R1 sandy mudstone as the cutting-top layer. The dimensions of the cutting-top board were 22 cm × 10 cm × 4 cm, with a cutting-top width of 10 cm and a cutting-top thickness of 4 cm. The experimental plan designed a mining range of 150 cm, with eight pre-embedded wooden boards, which means eight cutting areas which were 80 cm, and seven filling areas which were 70 cm.

As shown in Figure 3, grid lines are drawn on the front of the model using a plumb line, with a grid size of 10 cm × 10 cm. Give displacement observation lines of 10 m, 20 m, 40 m, 70 m, and 110 m (corresponding to 0.1 m, 0.2 m, 0.4 m, 0.7 m, and 1.1 m in the 1:100 scale model) above the coal seam were set up. Forty-two stress sensors were installed and divided into three series: L1 (1-11~1-15), L2 (2-1~2-15), and L3 (3-1~3-15). The sensors inside the coal column were spaced at intervals of 10 cm, while those in the goaf were spaced at intervals of 15 cm.

3.2. Similar Simulation Analysis of Caving and Cut-and-Fill Mining

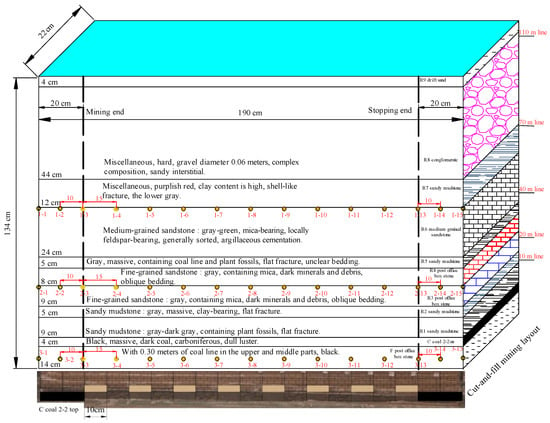

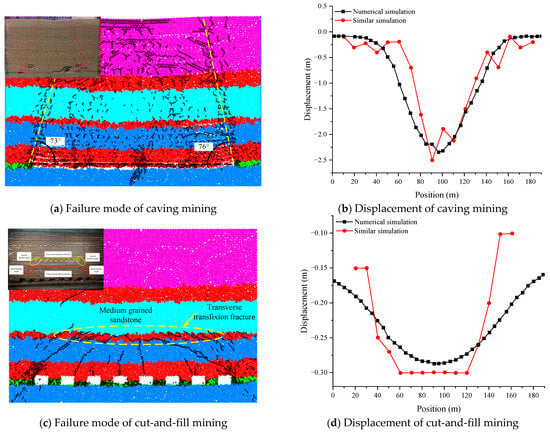

The similar simulation failure physical map of caving mining and cut-and-fill mining are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Failure characteristics of overlying rock after mining. Compares the failure patterns of the overburden. Caving mining (a) causes step-type damage reaching the surface, whereas in cut-and-fill mining (b), the gangue pillars support the goaf roof, confining the failure beneath the key stratum and resulting only in limited, layered fractures.

After the caving mining is completed, the overburden rock falls to the surface and forms a step-type damage. At both ends of the working face, two fracture cracks directly to the surface are developed, and the fracture angle is about 70°. In the process of caving mining, mining-induced fractures are fully developed. After the end of mining, the overlying rock fissures of the whole stope roof are fully developed, and even local excessive caving occurs.

Upon completion of cut-and-fill mining, with the compaction and deformation of the gangue column, the rock layer within the basic roof decreases rapidly, and the initial fracture line of about 45° is generated at both ends of the stope. The ends of the two initial fracture lines are connected by a horizontal through fracture. With the further compaction of the gangue column, the rock layer under the medium-grained sandstone of R6 shows obvious deformation, and two roughly symmetrical secondary fracture lines are generated from the terminal position of the initial fracture line. The terminal of the secondary fracture line is connected by a horizontal through fracture. Due to the role of the R6 key stratum, the fracture no longer extends to a higher level.

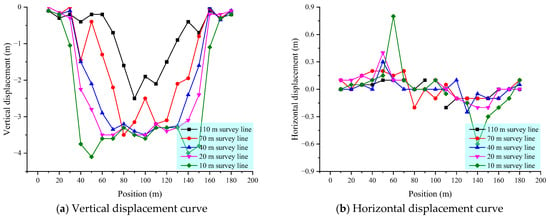

3.2.1. Analysis of Bedrock Displacement Evolution Law

As shown in Figure 5, after caving mining, the subsidence values of each measurement point on the 10 m and 20 m survey lines closer to the coal seam are relatively large. The maximum vertical displacement near the surface on the survey line is 2.51 m. Due to the transitional and random nature of the collapse, there are many singular points of horizontal deformation, with the maximum horizontal displacement at the surface being approximately 0.19 m. The origin of the coordinates is on the left side of the model, and the displacement data is obtained from model monitoring data after conversion using a size similarity ratio. Since the size similarity ratio is 1:100, when the unit is m, it represents the actual dimension, and when the unit is cm, it represents the model dimension.

Figure 5.

Subsidence curve after caving mining. Displacement along different survey lines after caving mining. (a) The vertical displacement curve shows a maximum subsidence of 2.51 m near the surface. (b) The horizontal displacement curve indicates non-uniform deformation with a maximum subsidence of 0.19 m, suggesting intense and uncoordinated strata movement.

As illustrated in Figure 6a, after the completion of cut-and-fill mining, a noticeable separation is observed at the top of the R3 rock layer. The deformation of the overlying strata was significantly controlled due to the support from the gangue pillars. On the 110 m, 70 m, and 40 m survey lines, the recorded vertical and horizontal displacements were all less than 1.0 mm, as measured by our displacement monitoring system with an accuracy of ±0.1 mm, falling within the noise level of the instrumentation and thus considered negligible. In contrast, the 10 m survey line exhibited fluctuating behavior, and the 20 m survey line showed almost no fluctuation. The frictional resistance effect of the gob pillars against horizontal movement of the overlying strata, along with their uniform support function, resulted in minimal horizontal displacement that alternated between positive and negative values. This distribution pattern is also influenced by edge effects, which lead to greater horizontal displacements near the coal pillar.

Figure 6.

Subsidence curve after cut-and-fill mining.

Figure 6b demonstrates that under the influence of the filled gangue pillars and the critical R6 layer, the extent and degree of damage to the roof are significantly mitigated. Since the primary form of overburden movement is vertical compression, changes in horizontal displacement remained limited. At the 40 m survey line, the maximum vertical displacement decreased to 0.29 m, with the maximum horizontal displacement being only 0.02 m. As the distance from the mined area increased (i.e., as we move further away from the mining region), there is a clear trend of decreasing maximum vertical and horizontal displacements at the end of mining activities.

Under caving mining, the maximum vertical displacement at the 10 m survey line is 2.51 m (located at x = 85 m), and the maximum horizontal displacement is 0.19 m (located at x = 95 m). In sharp contrast, the maximum vertical and horizontal displacement of the filling mining at the 10 m survey line is only 0.29 m (x = 65 m) and 0.02 m (x = 75 m), respectively. More importantly, in the 40 m and above survey lines (40 m, 70 m, 110 m), the displacement of filling mining is less than the sensitivity threshold of the monitoring system (±0.1 mm), indicating that the displacement can be ignored. This quantitatively proves the excellent effectiveness of filling mining in controlling rock movement.

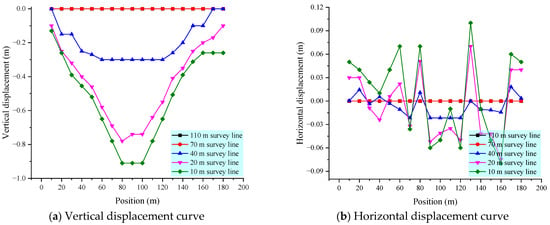

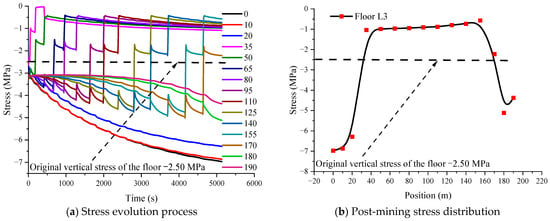

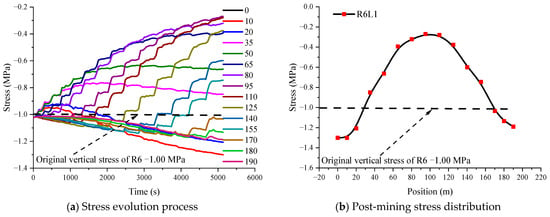

3.2.2. Analysis of the Law of Bedrock Stress Evolution

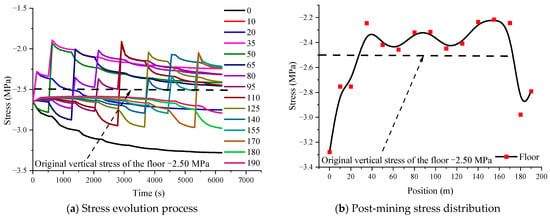

Figure 7a is the stress evolution process of measuring points at different positions of the floor during the mining process of the caving method, and the original vertical stress of the floor is 2.50 MPa. During the mining process, the stress of the measuring point in the goaf experienced a process of increasing–decreasing–stabilizing, and the stress of the measuring point in the coal pillar was in a monotonically increasing process.

Figure 7.

Stress evolution and distribution of L3 stress observation lines of caving mining.

Figure 7b shows the post-mining stress distribution of the measuring points at different positions of the floor during the caving mining process. This shows the zoning characteristics of the stress relief of the measuring points in the goaf and the stress concentration of the measuring points in the coal pillar. The measuring point stress of the coal pillar at the initial mining end is obviously greater than that of the coal pillar at the final mining end.

It can be seen in Figure 8 that the original vertical stress of the R6 rock stratum is 1.00 MPa, and the stress evolution process of the R6 rock stratum is similar to that of post-mining stress distribution, which is not repeated here. The negative value of stress monitoring data is expressed as compressive stress, which is converted by a strength similarity ratio.

Figure 8.

Stress evolution and distribution of R6L1 stress observation lines of caving mining.

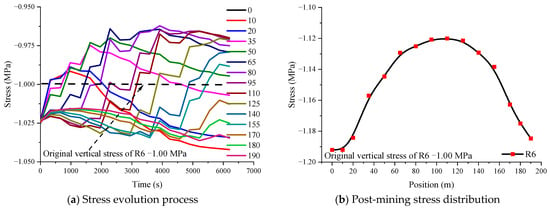

As illustrated in Figure 9, after the completion of cut-and-fill mining, the stress evolution process of floor strata at the measurement points remains unchanged with the implementation of cut-and-fill mining. However, this method alters the post-mining stress distribution pattern in the floor strata. Due to the alternating arrangement of roof cutting and backfill operations, the floor stress exhibits a wave-like pattern, characterized by stress relief in the cutting area and stress recovery in the filling area. Partial backfill effects result in the stress within the filling areas essentially reverting to the original rock stress levels.

Figure 9.

Stress evolution and distribution of L3 stress observation lines of cut-and-fill mining.

Figure 10 reveals that the stress at the measurement point of R6 strata underwent an evolution process similar to that observed in the floor measurement points. However, the post-mining stress distribution at R6 differs from that of the floor, lacking a wave-like appearance. After the completion of cut-and-fill mining, the medium-grained sandstone layer (R6) experiences concentrated stress. This is because the fine-grained sandstone layer (R3) has lost its load-bearing capacity, leaving the medium-grained sandstone layer (R6) as the critical layer responsible for bearing the load.

Figure 10.

Stress evolution and distribution of R6L1 stress observation lines of cut-and-fill mining.

3.3. Numerical Simulation Analysis of Caving and Cut-and-Fill Mining

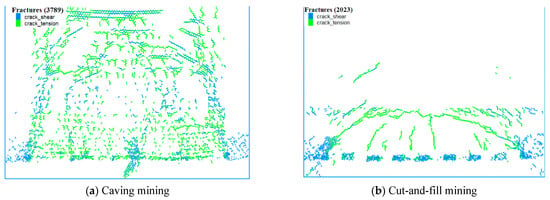

Through similar material simulation experiments, it was observed that there exists a significant disparity in the quantity of mining-induced fractures between the cut-and-fill mining and caving mining processes. Notably, PFC demonstrates distinct advantages in simulating these fractures [27,28]. Therefore, this section employs PFC 2D 5.00 to simulate the distribution patterns of fractures in both cut-and-fill mining and caving mining.

The flat-joint contact is closer to reality in field applications, so the flat-joint contact model was selected for the contact between particles in numerical simulation [29]. In the process of uniaxial compression, when the loading rate is below 5 mm/s, the yield limit of the two tests is basically the same. Therefore, a 5 mm/s loading rate was selected for simulation analysis in the subsequent parameter calibration [27]. It is pointed out that when the height L and the particle radius R of the standard specimen satisfy L/R > 60, the particle size has little effect on the calculation results [30,31]. Python 3.0 was used to carry out automatic parameter calibration. Python automatically calculated the error of uniaxial compressive strength, uniaxial tensile strength, and elastic modulus parameters, and gave the weight of 1/3 of the three parameter errors. When the single error was within 0.010 and the total error was within 0.010, it was considered that the parameters were reasonable and the check was stopped.

The stope model was established by using the calibrated rock parameters to carry out the mining of caving method and cut-and-fill mining method, respectively. Following the coal seam caving mining process, numerical simulation generated the fracture morphology of the rock layer as depicted in Figure 11a, accompanied by the subsidence curve illustrated in Figure 11b. Subsequently, the fracture morphology of the bedrock resulting from numerical simulation after cut-and-fill mining is presented in Figure 11c, and the corresponding bedrock subsidence curve is depicted in Figure 11d. Notably, the fracture morphology of the rock strata in both the numerical simulation and the analogous simulation test exhibited a high degree of congruence, with the displacement error along the same monitoring line falling within an acceptable range. This consistency suggests that the modeling method and parameter selection for the numerical model are reasonable and can be reliably employed for subsequent analyses.

Figure 11.

Failure mode and comparison of numerical simulation and similar simulation.

3.4. Comparative Analysis of Caving and Cut-and-Fill Mining

3.4.1. Comparison of Displacement Deformation and Stress State

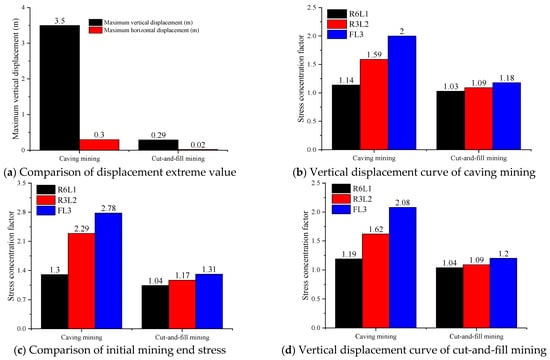

Due to an excessive collapse of the strata within the 10 m and 20 m survey lines (monitoring the floor and lower overburden) in caving mining, displacements are not suitable for reasonable comparison. The significant movement of overlying strata in the cut-and-fill mining is observed within the 40 m survey line. Therefore, the displacement of the 40 m survey lines for both the caving and cut-and-fill mining methods are statistically analyzed, as shown in Figure 12a.

Figure 12.

Comparison of effect of different mining methods.

From Figure 12a and the clear process of damage in the similar simulation experiment, it is evident that the displacement in cut-and-fill mining is significantly smaller than that in caving mining. Through calculations, it is found that the vertical displacement in cut-and-fill mining is only 8.29% of that in caving mining, and the horizontal displacement is only 6.67% of that in caving mining. This indicates that cut-and-fill mining can effectively control surface subsidence without the need for external filling materials.

The comparison analysis of stress concentration factors are illustrated in Figure 12b–d. During the mining process, the stress concentration factor in caving mining is significantly higher than that in cut-and-fill mining. Taking the mining floor as an example, the stress concentration factor in cut-and-fill mining is approximately 56% of that in caving mining. This value, which pertains specifically to the stress state and is independent of the previously mentioned fracture ratio (59.7%), falls within a range of 56% to 59% when considering the spatial averaging of stress sensors and model calibration uncertainty (with a confidence interval of approximately ±1.5%). This indicates that cut-and-fill mining can obviously reduce mining-induced stress, which is beneficial for the stability of the working face.

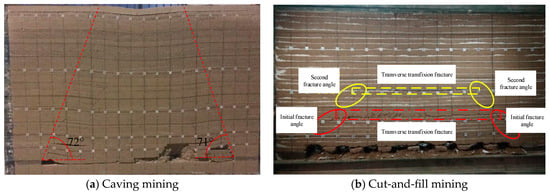

3.4.2. Quantitative Comparative Analysis of the Mining-Induced Fractures

Statistics of fracture types and quantities for caving and cut-and-fill mining are shown in Figure 13 and Table 1. In the case of caving mining, a total of 3789 fractures were generated, with shear fractures comprising 34.9% (1325 fractures) of the total, predominantly localized on both sides of the fracture angles. Tension fractures, numbering 2464, accounted for 65.1% of the total fractures and were primarily situated in the adjacent rock layers above the goaf and on both sides of the fracture angles. This indicates a prevalence of tensile failure in the adjacent rock layers above the goaf, with both shear and tensile failures occurring on both sides of the fracture angles.

Figure 13.

Fracture propagation law of model.

Table 1.

Fracture generation of caving and cut-and-fill mining model.

In contrast, after the completion of cut-and-fill mining, a total of 2023 fractures were generated. Shear fractures constituted 59.7% (1208 fractures) of the total and were primarily distributed on both sides of the fracture angles and within the designated filling area. It is important to note that this percentage describes the proportion of fracture types and is distinct from the stress-related comparisons discussed subsequently. Notably, similar to caving mining, the adjacent rock layers above the goaf primarily experienced tensile failure, while the rock layers on both sides of the fracture angles concurrently underwent both shear and tensile failures.

This comparative analysis underscores the distinct fracture distributions resulting from the two mining methods. While caving mining exhibits a higher total fracture count, cut-and-fill mining demonstrates a higher proportion of shear fractures. Additionally, both methods yield similar patterns of failure in the adjacent rock layers above the goaf and on both sides of the fracture angles. The total number of fractures in cut-and-fill mining reduced by 46.6%, with shear fractures decreasing by 8.8% and tensile fractures decreasing by 66.9%.

Mining-induced fractures are the root cause of such damage. Roof filling can significantly reduce the number of mining-induced fractures, especially those in the roof strata. This has a positive, even decisive, impact on rock layer control, water level management, and gas suppression during coal mining. It is beneficial for the protection of subsequent surface structures, water resources, and clean utilization of gas.

The significant reduction in tensile fractures (66.9%) compared to shear fractures (8.8%) is particularly beneficial for long-term stability and fluid flow control. Tensile fractures tend to form continuous pathways, increasing permeability and the potential for water or gas migration. The higher proportion of shear fractures in cut-and-fill mining indicates a more interlocked, less permeable fracture network, which enhances the long-term integrity of the overburden and reduces risks of aquifer drainage or gas leakage.

4. Discussion

4.1. Damage Control Effect of Cut-and-Fill Mining

The wave-like stress distribution observed in this study aligns well with the stress release/transfer model derived from rock damage mechanics. This pattern is consistent with the stress evolution law in shallow coal seams based on damage theory, as proposed by researchers like Liu et al. [15]. The roof cutting action causes local damage to the roof rock in the cutting areas, leading to a transfer of stress to the intact filling areas. The supporting effect of gangue columns stabilizes the stress in filling areas at the original rock level, forming a wave-like characteristic of alternating “pressure relief-bearing”, which is consistent with the stress evolution law of shallow coal seams based on damage theory proposed by Liu et al. [15]. In addition, the delayed overburden deformation conforms to the viscoelastic creep model: the elastic deformation of the R6 key stratum and the viscoplastic deformation of gangue columns act synergistically to delay the stress redistribution rate, verifying the creep characteristics of the “elastic matrix-viscoplastic filling body” composite structure, which is consistent with the viscoelastic deformation law of on-site shallow coal seams.

Based on the stress-displacement monitoring results of similar and numerical simulation tests, the stress distribution of the floor in cut-and-fill mining exhibits a wave-like pattern, while the stress distribution of the roof is similar to the conventional distribution in caving mining. The displacement of the roof near the working face shows a multi-peak shape, but in the area far from the working face, the displacement gradually returns to a symmetric single-peak curve. Due to the time-dependent deformation of the gangue column, the deformation of the overlying strata is delayed, and the overall coordination and integrity of the deformation are significantly enhanced.

As shown in Figure 14, in terms of the form of mining-induced damage, the cut-and-fill mining gangue column can directly support the roof, effectively eliminating the gradient differences in horizontal and vertical deformation, markedly suppressing the generation of mining-induced fractures, greatly reducing the displacement difference in the roof above immediate roof, and preventing the roof from breaking and collapsing, thereby stopping the downward movement of overlying strata from higher levels. This slows down the surface deformation in terms of both magnitude and rate, effectively mitigating uneven subsidence, and significantly reducing the impact on surface structures.

Figure 14.

Damage control effect of cut-and-fill mining.

In terms of the temporal aspect of mining-induced damage, based on the granular mechanics characteristics of the gangue column, the overlying strata disturbed by the cooperative mining process of the gangue column undergo a continuous and stable unloading process for the entire mining area. Compared to caving mining, under the joint action of controlled density and continuous distribution of the gangue columns, the deformation of the overlying strata in the mining area is linked together, and the overall deformation time is extended.

In summary, cut-and-fill mining achieves damage control of surrounding rock through relatively uniform, slow, and continuous lateral deformation, as well as vertically coordinated deformation of the overlying strata.

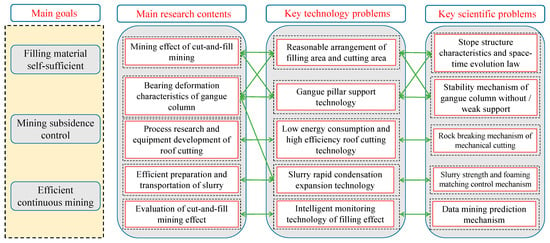

4.2. Feasibility of Cut-and-Fill Mining

As shown in Figure 15, the main goal of cut-and-fill mining is to achieve self-sufficiency and in situ filling of filling materials, thereby significantly reducing material costs, improving filling efficiency, and increasing environmental benefits. However, the effectiveness and applicability of cut-and-fill mining require comprehensive and systematic examination through various means. The design of the cut-and-fill mining process system, as well as the development of essential equipment, forms the foundation for implementing this mining method. The establishment of a stable gangue column bearing structure after cut-and-fill mining is pivotal to the success of the entire process. Additionally, the development of new grouting materials is essential to enhance the stability of the cut-and-fill mining stope. The monitoring and control of the whole process of cut-and-fill mining is also a necessary research focus to evaluate the roof cutting and filling mining.

Figure 15.

Logical diagram of cut-and-fill mining technology system.

The present study provides preliminary verification for the cut-and-fill mining method; further experimental validation is required. It serves as a starting point in the systematic exploration of cut-and-fill mining techniques in the future. The remaining critical aspects will require further in-depth investigation.

4.3. Limitations and Future Work Regarding Gangue Column Behavior

It is important to note that the time-dependent deformation of the gangue column, identified as a key factor in extending overburden deformation time, is treated as a beneficial stabilizing effect in this preliminary study. However, the long-term mechanical behavior of the gangue column, including its porosity evolution, creep characteristics, and response to cyclic loading from adjacent mining activities, was not experimentally verified or explicitly parameterized in the numerical models. The potential viscoelastic or plastic evolution of the gangue column under sustained and cyclic loads could influence stress redistribution in the surrounding strata over time. Future work should therefore include the experimental characterization of the compacted gangue’s rheological properties coupled with numerical simulations to rigorously assess the long-term stability and potential time-dependent effects of the proposed self-sufficient cut-and-fill system.

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The proposed cut-and-fill mining method demonstrates significant potential as a green mining technology by achieving material self-sufficiency through the utilization of the goaf roof as in situ filling material. This approach substantially reduces the reliance on external filling materials and associated transportation costs, while the observed reductions in surface subsidence and mining-induced fractures contribute to improved environmental protection.

- (2)

- Through a similar simulation, the maximum surface vertical and horizontal displacement reached 2.51 m and 0.19 m of caving mining, resulting in a stepped subsidence pattern. The maximum vertical and horizontal displacement along the 40 m survey line was 0.29 m and 0.02 m of cut-and-fill mining, offering a more uniform and controlled deformation pattern. The stress concentration coefficient of the floor in cut-and-fill mining was 56.00% of that in caving mining.

- (3)

- Numerical simulation reveals a substantial reduction in the total number of fractures with cut-and-fill mining, with shear fractures decreasing by 8.8% and tensile fractures decreasing by 66.9%. The gangue column effectively supports the roof, significantly reducing the displacement differences and suppressing the generation of fractures. Cut-and-fill mining leads to a linked deformation pattern across the mining area, effectively extending the overall deformation time compared to caving mining.

Author Contributions

All the authors contributed to publishing this paper. C.W. conceived the main idea of the paper; L.W. designed the research framework; Q.G. contributed to theoretical analysis; X.S. analyzed the data; N.Z. prepared the experimental resources; X.L. and W.G. wrote the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.52304198), National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC3009100, 2023YFC3009102).

Data Availability Statement

All the data in this paper are available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no potential conflicts of interest with the research, authorship, and/or publication of this paper. The authors acknowledge that the affiliation of one co-author with China Energy Group Shanxi Dongpo Coal Industry Co., Ltd. may be perceived as a potential conflict of interest due to the subject of the research. However, the authors affirm that the research was conducted independently, without any influence from the company on the study design, results, or conclusions.

References

- Ercikdi, B.; Baki, H.; İzki, M. Effect of desliming of sulphide-rich mill tailings on the long-term strength of cemented paste backfill. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 115, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercikdi, B.; Yılmaz, T.; Külekci, G. Strength and ultrasonic properties of cemented paste backfill. Ultrasonics 2014, 54, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.G.; Xu, J.H.; Miao, X.X. Shortwall Mining Technology and Its Application; Coal Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Munjeri, D. Prevention of subsidence using stowing methods. Colliery Guardian 1987, 235, 245–246. [Google Scholar]

- Shaposhnik, Y.N.; Neverov, A.A.; Kudrya, A.O.; Neverov, S.A.; Nikol’sky, A.M. Justification of Extraction of Ore Reserves under Bottom and in Pitwall Rock Mass Using Cut-and-Fill Method in Transition from Open Pit to Underground Mining in the Artemevsky Mine. J. Min. Sci. 2024, 60, 966–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, D.X.; Hu, G.L.; Zhu, W.B.; Wang, L. Field test on dynamic disaster control by grouting below extremely thick igneous rock. J. China Coal Soc. 2012, 37, 1967–1974. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal, A.; Shrivastva, B.K. Stability analysis of the proposed hybrid method of partial extraction for underground coal mining. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2012, 52, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.X.; Miao, X.X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.G.; Yan, H. Integrated coal and gas simultaneous mining technology: Mining-dressinggas draining-backfilling. J. China Coal Soc. 2016, 41, 1683–1693. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.X.; Zhang, Q.; Ju, F.; Zhou, N.; Li, M.; Sun, Q. Theory and technique of greening mining integrating mining, separating and backfilling in deep coal resources. J. China Coal Soc. 2018, 43, 377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, G.L.; Wang, Y.H.; Ma, Z.G. A New method for ground subsidence control in coal mining. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2004, 33, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Onica, I.; Marian, D. Ground surface subsidence as effect of underground mining of the thick coal seams in the Jiu valley basin. Arch. Min. Sci. 2012, 57, 547–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.Y.; Guo, J.T.; Yan, Y.G.; Li, P.X.; Liu, Y.S. Principle and application of subsidence control technology of mining coordinately mixed with backfilling and keeping. J. China Coal Soc. 2014, 39, 1602–1610. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; You, Q.; Zhu, W.; Li, X.S.; Lai, W. Theoretical study of strip-filling to control mining subsidence. J. China Coal Soc. 2007, 32, 119–122. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Xu, J.; Zhu, W.; Wang, X. Theoretical study on the backfill grouting in caving area with stripmining. J. China Coal Soc. 2008, 33, 1205–1210. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.X.; Guo, G.L.; Zha, J.F.; Li, Y. A new method of point-pillar paste filling in coal mining. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2009, 26, 490–493. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, J.; Wang, J.; Tan, Y.; Xu, Q. Mechanical mechanism of overlying strata breaking and development of fractured zone during close-distance coal seam group mining. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2020, 30, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhienbayev, A.; Balpanova, M.; Asanova, Z.; Zharaspaev, M.; Nurkasyn, R.; Zhakupov, B. Analysis of the roof span stability in terms of room-and-pillar system of ore deposit mining. Min. Miner. Depos. 2023, 17, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takhanov, D.; Zhienbayev, A.; Zharaspaev, M. Determining the parameters for the overlying stratum caving zones during re-peated mining of pillars. Min. Miner. Depos. 2024, 18, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Silva, M.C.E.; Costa Pereira, M.F.; Bras, H.; Paneiro, G. Strength behavior and deformability characteristics of paste backfill with the addition of recycled rubber. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2023, 37, 713–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.J.; Li, Z.H.; Du, F.; Xu, L.; Zhu, C. Experimental investigation of the mechanical properties and large-volume laboratory test of a novel filling material in mining engineering. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2023, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Luo, C.; Jia, Y.; Wang, Z. Study on roof movement law of local filling mining under peak cluster landform. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZHAO, Y.; YANG, Y.; WANG, Z.; GU, Q.; WEI, S.; LI, X.; WANG, C. Innovative cut-and-fill mining method for controlled surface subsidence and resourceful utilization of coal gangue. Minerals 2025, 15, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.X.; Zhang, Q.; Ju, F.; Zhou, N.; Li, M.; Zhang, W. Practice and technique of green mining with integration of mining, dressing, backfilling and X in coal resources. J. China Coal Soc. 2019, 44, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Ju, F.; Li, M.; Zhou, N.; Zhang, Q. Method of coal gangue separation and coordinated in-situ backfill mining. J. China Coal Soc. 2020, 45, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.X.; Tu, S.H.; Cao, Y.J.; Tan, Y.L.; Xin, H.Q.; Pang, J.L. Research progress of technologies for intelligent separation and in-situ backfill in deep coal mines in China. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2020, 37, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, G.; Du, X.; Guo, Y.; Qi, T.; Wang, Z.; Li, Q.; Li, H.; Kang, L. Basic theory of constructional backfill mining and the underground space utilization concept. J. China Coal Soc. 2019, 44, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, S.; Karlovsek, J. Calibration and uniqueness analysis of microparameters for DEM cohesive granular material. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2022, 32, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Wang, Z.; Karlovsek, J. Analytical study of subcritical crack growth under modeI loading to estimate the roof durability in underground excavation. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2022, 32, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itasca Consulting Group, Inc. PFC-Particle Flow Code in 2 and 3 Dimensions, Version 5.0; Itasca Consulting Group, Inc.: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2018.

- Hofmann, H.; Babadagli, T.; Yoon, J.S.; Zang, A.; Zimmermann, G. A grain based modeling study of mineralogical factors affecting strength, elastic behavior and micro fracture development during compression tests in granites. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2015, 147, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrani, N.; Kaiser, P.K.; Valley, B. Distinct element method simulation of an analogue for a highly interlocked, non-persistently jointed rockmass. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2014, 71, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).