Abstract

To broaden the operating bandwidth of the vibration energy harvester at low frequencies, this paper presents a cantilever beam piezoelectric energy harvester (PEH) based on the sloshing of a liquid-filled container. The harvester is designed to recover energy from the multi-order sloshing modes of the liquid in the container. A mathematical model of the coupled system comprising the liquid within the container and the PEH was established. Based on the fluid–structure interaction (FSI) theory, the coupling mechanism between the liquid natural sloshing frequency and the immersed natural frequency of the beam was revealed. Experimental validation shows that the resonance characteristics of the PEH are mainly dominated by the liquid antisymmetric sloshing mode. Through comparative experiments, the effect of liquid-filled container and cantilever beam parameters on the PEH’s peak output voltage and operating bandwidth was systematically analysed. The performance of the PEH was significantly improved when the first-order natural frequency of the partially immersed beam approached the liquid natural sloshing frequency, with the bandwidth coefficient increasing by nearly fourfold under this condition. This research provides new ideas for the design and optimisation of piezoelectric energy harvesters in liquid sloshing environments.

1. Introduction

With the continuous development of new energy vehicles and intelligent driving technologies, sensor systems are increasingly deployed in vehicles, leading to a corresponding rise in energy demand. This has significantly propelled the application of energy harvesting technologies. Identifying suitable power sources for intelligent devices in vehicle systems has become an interesting topic. Among various energy sources, vibration energy has attracted extensive attention due to its abundance and accessibility [1,2]. By harnessing the low-frequency vibration energy generated during vehicle operation to drive sensors and combining with wireless Bluetooth data transmission, self-powered wireless monitoring can be achieved simultaneously. This system not only solves the traditional power supply issues but also helps address the pain points of redundant power supply wiring and frequent battery replacement for on-board electronic devices [3,4,5]. Therefore, the development of efficient vibration energy harvesting technology for vehicles has significant engineering significance.

Piezoelectric materials, owing to their efficient electromechanical coupling characteristics, have become a key material system in the field of vibration energy harvesting. Vibration energy harvesting devices based on the direct piezoelectric effect, with their advantages of high power density, low manufacturing cost and miniaturised structure, have become a research focus in the academic community [6,7,8]. Current research on vehicle-based piezoelectric energy harvesters shows a growing trend towards diversification. Al-Yafeai et al. [9] systematically reviewed progress in harvesting energy from vehicle suspension systems using piezoelectric technology, revealing substantial performance differences among approaches, with output power ranging from 0.001 mW to 3.9 W. The authors emphasise that overcoming technical bottlenecks hinges on optimising piezoelectric materials: designing customised piezoelectric components to convert automotive mechanical vibrations into electrical energy is therefore a viable approach. Elfrink et al. [10] measured the characteristics of vibration energy harvesters of varying sizes under sinusoidal vibration and shock excitation, achieving an output power of 489 μW, and simulated and validated the potential of PEHs in automotive tyre applications. Yoo et al. [11] developed an end-cap tyre-strain piezoelectric energy harvester (PEH), which was innovatively implanted into the inner wall of the tyre to capture strain energy. Through optimisation of the model, it can ultimately generate 138 mW of output power, which is sufficient to drive multiple sensors inside the automotive tyre. Tuo et al. [12] proposed a quasi-zero stiffness high-performance vibration isolation and energy harvesting integrated system based on a piezoelectric buckling beam structure, which can simultaneously meet the vibration isolation and power supply requirements of automotive seat suspensions. Yang et al. [13] designed a parameter-optimised T-beam PEH and experimentally explored its potential for harvesting energy from automotive drive motor vibrations. Tian et al. [14] proposed a PEH based on a coupled oscillator model. In this system, the two oscillators are distributed in an upper and lower structure, and each oscillator is composed of a mass plate, a spring plate, a bracket and piezoelectric materials. Under the coupling effect of the oscillators, the amplitude–frequency characteristic curve of each oscillator has two peak points, thereby broadening the frequency bandwidth. This enables energy harvesting within the frequency range of 5–25 Hz.

One of the key challenges in vibration energy harvesting devices lies in their narrow operating frequency bandwidth, which severely constrains their practical applicability. Notably, liquid-filled containers within vehicles can generate multi-order liquid sloshing modes when subjected to motion excitation, each of which possesses significant wave energy. Harnessing the abundant kinetic energy contained within the fluid to broaden the energy harvester’s operating bandwidth offers considerable development potential.

At present, the piezoelectric energy harvesting technology using liquid as the working medium has formed a systematic research framework. Hamlehdar et al. [15] comprehensively reviewed the piezoelectric energy harvesting devices based on different fluid motions and discussed various modelling approaches and optimisation methods for improving their efficiency. Taylor et al. [16] developed an eel-like piezoelectric energy harvesting device, which utilises the regular trajectory of the vortices behind the blunt body to induce strain in the piezoelectric polymer to generate electricity. This device can be scaled to produce outputs ranging from milliwatts to several watts. Song et al. [17] designed a vertical vortex-induced vibration piezoelectric energy harvester (VIVPEH) composed of a PZT cantilever beam and a cylindrical extension, and conducted theoretical and experimental investigations on the energy harvesting capability of the VIVPEH. Mutsuda et al. [18] pioneered a flexible piezoelectric coating device composed of elastic materials and piezoelectric coatings. They designed and characterised the piezoelectric device based on varying specifications, such as piezoelectric ceramic thickness, to enhance the PEH’s reliability and durability in water. Yang et al. [19] designed a piezoelectric energy harvesting device with liquid as the working medium. Connecting an array of floating rods to piezoelectric cantilever beams enables ultra-low-frequency, low-intensity, multi-directional vibration energy harvesting on water surfaces. Nabavi et al. [20] developed a piezoelectric energy harvesting system that simultaneously accounts for wave frequency and wave height. Operating under low-frequency waves, it provides the required energy for electrical equipment within small navigation buoys. Kazemi et al. [21] designed a waterproof piezoelectric energy harvester that can collect energy from the longitudinal and lateral movements of ocean waves. Experimental tests were performed on cantilever beam piezoelectric energy harvesters positioned at three distinct orientations, fully submerged in water. It was determined that the optimal orientation occurs when the vibration direction of the cantilever beam aligns with the wave propagation direction and is perpendicular to the water surface, thereby generating harmonic oscillations with the maximum voltage output. Sahoo et al. [22] investigated a piezoelectric vibration energy harvester integrating a cantilever bimorph beam and a partially water-filled cylindrical container. By coupling the liquid sloshing modes within the container with the beam’s lateral motion, the effective energy harvesting bandwidth increased by 58%. Kim et al. [23] proposed a PEH based on liquid sloshing, and by varying the excitation amplitude, frequency, water level, and the thickness of the cantilever beam, analysed the dynamic and energy output characteristics of the harvester, and demonstrated the feasibility of practical power generation using such PEHs in large liquid containers.

However, although significant achievements have been made in piezoelectric energy harvesting based on liquid-induced energy, to our knowledge, systematic research on harvesting vibration energy induced by liquid sloshing in on-vehicle containers remains largely unexplored. Specifically, when real trucks travel at normal highway speeds (60–100 km/h), the vehicle body generates low-frequency vibrations of 0.9–5.8 Hz due to road irregularities [24]. In addition, low-frequency vibrations also occur when the vehicle is turning at low speeds, braking, or when the liquid filling rate in the container is relatively low [25,26,27]. These low-frequency vibration frequencies generated in various actual operating scenarios of the vehicle are valuable energy sources that should also be effectively utilised. By coupling the time-varying fluid pressure induced by liquid sloshing with the lateral vibration of piezoelectric cantilever beams and leveraging the multi-order vibration modes inherently generated by liquid sloshing, this work is expected to realise energy harvesting over a broader operating frequency range.

In this paper, we design a cantilever beam piezoelectric energy harvesting system based on the sloshing of a liquid-filled container and establish its fluid–structure interaction model. Experimental tests are conducted to investigate the resonance and energy output characteristics of this PEH, and systematically analyse the effects of liquid depth, container width, cantilever beam thickness and width on its energy conversion performance.

2. Theoretical Method and Experimental Test

2.1. Description of the PEH Model

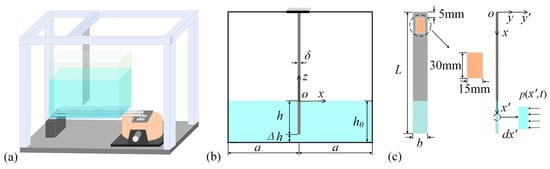

When a vehicle is running over an uneven road, the front and rear ends of a liquid-filled container, move up and down successively, causing the liquid inside the container to slosh, thereby generating usable vibration energy. Based on this, a cantilever PEH based on the liquid-filled container sloshing is presented, as shown in Figure 1a. One end of the container is connected to a fixed support via a hinge, while the other end is connected to a vibration exciter, which drives the container up and down to produce liquid sloshing. A cantilever beam is installed at the centre of the container with the free end immersed in the liquid, with its free end forced to vibrate under the excitation of the sloshing liquid, and the piezoelectric element attached to the beam converts mechanical energy into electrical energy.

Figure 1.

The cantilever PEH based on liquid-filled container sloshing: (a) schematic diagram of the experimental setup; (b) the liquid-filled container with PEH; (c) the cantilever-based PEH.

The key dimensions and relative positions of the container and PEH are shown in Figure 1b,c. In the reference model, the container has a width of and a thickness of . The distance between the free end of the beam and the container bottom is , and the immersion depth of the beam is . The PEH consists of a cantilever beam and a piezoelectric ceramic (PZT-5H), where the piezoelectric ceramic has dimensions of . The cantilever beam has a length , width , and thickness . The cantilever beam is made of aluminium, with a density of , and an elastic modulus of . The container is filled with water, which has a density of . The ambient temperature is set to 30 °C based on the average room temperature during the experiment, with the dynamic viscosity of water corresponding to .

2.2. Theoretical Analysis

- (1)

- Natural Sloshing Frequency of the Liquid in the Container

The natural frequency of the liquid sloshing is a key foundation for the design of the fluid–structure interaction (FSI) energy harvester. When the excitation frequency approaches the liquid natural sloshing frequency, this induces intense sloshing within the container, which exerts a significant excitation force on the cantilever beam, enabling the PEH to produce a notable voltage output.

It is assumed that the liquid in the container sloshes in two dimensions, and the container walls are treated as rigid bodies. In the coordinate system shown in Figure 1b, the velocity potential function of the sloshing liquid can be expressed as [28]:

The boundary conditions on the left and right sides, as well as the bottom of the container, can be expressed, respectively, as [29]:

Meanwhile, the kinematic and dynamic boundary conditions at the liquid’s free surface can be expressed as [28]:

It is assumed that the velocity potential function has a solution of the following form:

where is the imaginary unit, and represents the liquid natural sloshing frequency. By applying the separation of variables method, the -th natural sloshing frequency of the liquid can be obtained as [30]:

When is an odd number, corresponds to the natural sloshing frequency of the antisymmetric mode, while when is an even number, corresponds to the natural sloshing frequency of the symmetric mode.

- (2)

- Fluid Structure Interaction (FSI) Model of Cantilever Beam

The natural frequency of the partially immersed cantilever beam also affects the output of the PEH. When a rectangular-section cantilever beam vibrates transversely in the fluid, the surrounding fluid motion is analogous to that around a circular-section beam [31], and the hydrodynamic force can be calculated by solving the Navier–Stokes (N-S) equation of the surrounding fluid. When an infinite cylinder with a diameter b moves harmonically in the fluid as , the fluid force acting on the cylinder per unit length can be written as [32]:

where w is the frequency of the harmonic motion, and w0 denotes the amplitude. The term represents the fluid mass displaced by the cylinder per unit length, namely the added mass. H denotes a hydrodynamic function with its complete expression given by a complex Bessel function. When the kinematic Reynolds number of the beam motion is sufficiently large, H can be approximated as [33]:

where Re denotes the kinematic Reynolds number, and ,

The fluid force on the structure is customarily expressed as a function of acceleration and velocity, which correspond to added mass and added damping, respectively.

where represents the added mass, and represents the added damping.

Since the cantilever beam is partially immersed in the fluid, a new coordinate system is established. The distributed fluid load on the micro element is considered as a concentrated force at ; thus, the motion equation of the beam can be written as:

where EI denotes the flexural stiffness of the beam, represents the density of the beam material, and is the Dirac function. The transverse motion of the beam can be expressed as:

where is the j-th mode shape of the cantilever, and represents the generalised coordinate corresponding to the j-th mode. Previous studies have shown that sufficient accuracy can be achieved by using the vacuum vibration model [34].

Substituting Equation (11) into Equation (10), multiplying both sides by after differentiation, and integrating over the range (0, L), the motion equation of the beam under the action of the microelement force can be obtained as:

It is assumed that the influence of micro element fluid force on the beam is linearly superposable, and we denote the initial and final position of the liquid immersion as and , respectively. By integrating the equation within the range of , the free vibration equation of the beam partially immersed in fluid can be expressed as:

where and represent the generalised mass and generalised stiffness of the beam, while and denote the added mass and added damping induced by the surrounding fluid, which can be expressed as:

The natural frequency of a cantilever beam partially immersed in fluid and vibrating can be obtained by solving the characteristic equation as follows:

Equation (15) indicates that the fluid mainly affects the immersed natural frequency of the beam through the added mass. The ratio of the immersed natural frequency of the beam to its vacuum natural frequency can be expressed as:

where denotes the dimensionless added mass factor. For the 1st vibration mode of the cantilever beam, the added mass factor per unit length can be written as:

Due to the influence of the piezoelectric ceramic, the actual natural frequency of the beam is different from its theoretical value. Therefore, the immersed natural frequency of the beam can be calculated by measuring the natural frequency in air through Equation (17).

- (3)

- Frequency Analysis

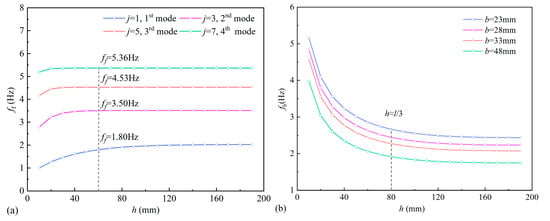

Based on the parameters given in the reference model, the sloshing frequencies of the first four antisymmetric modes of the liquid with varying liquid depth are shown in Figure 2a. When the liquid depth in the container is relatively shallow, the liquid natural sloshing frequency increases gradually as the liquid depth increases, and the higher-order sloshing frequencies change faster. When the immersion depth exceeds 40 mm, the natural sloshing frequencies of liquid above the third order remain relatively stable, and when , the first-order liquid natural sloshing frequency also remains relatively constant.

Figure 2.

Natural frequencies of liquids and beams: (a) the first four orders of antisymmetric modes of liquid; (b) the first-order mode of the beam with different width.

The variation in the first-order natural frequency of the beams with different widths as a function of the immersion depth is shown in Figure 2b. According to Equation (15), the natural frequency of the partially immersed beam depends on the added mass. When the free end of the cantilever is immersed in liquid, the added mass caused by the liquid increases rapidly with increasing immersion depth, resulting in a gradual decrease in the first-order natural frequency of the beam. However, when the immersion depth exceeds 1/3 of the total beam’s length, the increment of the added mass decreases gradually, and the first-order immersed natural frequency remains unchanged.

Therefore, in the subsequent experimental tests, the reference immersion depth of the beam is set to 60 mm. In this case, the first order natural frequencies of both liquid sloshing and beam vibration are still affected by the liquid depth, while liquid sloshing has no significant impact on the beam’s immersion depth. The analysis shows that as the liquid depth increases, the natural frequency of the liquid sloshing and the natural frequency of the partially immersed beam tend to converge. This model provides a theoretical basis for investigating the combined effects of the natural frequencies of the beam and the liquid on the energy harvesting performance, as well as optimising the PEH dimensions under different container specifications.

2.3. Experimental Procedures and Analysis

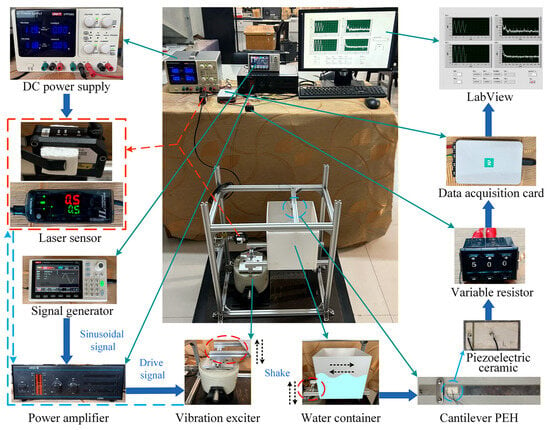

The performances of the PEH are studied through experimental tests, and the test platform established in this paper for the cantilever PEH based on liquid-filled container sloshing is shown in Figure 3. The experimental platform consists of the cantilever PEH, a water container, a DC power supply (UNI-T (Dongguan, China), UTP3303), a laser displacement sensor (UNI-T, UTG932E), a power amplifier (Jiangsu Lianyy Measurement & Control Technology Co., Ltd (Wuxi, China), LY2701), a vibration exciter (SINOCERA (Dongying, China), JZK-10), a laser sensor (KEYENCE (Osaka, Japan), IL-1000), a data acquisition card (NI (Austin, TX, USA), 9929), a variable resistor (BOURNS (Riverside, CA, USA), 3683S-1-105L), and other fixing devices.

Figure 3.

The experimental platform for the cantilever PEH utilising liquid sloshing.

In the experiment, the signal generator produces a sinusoidal signal, which is converted into a driving signal by the power amplifier. The driving signal is then transmitted to the vibration exciter, driving it to oscillate at the desired frequency and amplitude. The displacement of the vibration exciter is captured by the laser displacement sensor (red-arrow marked in the figure) and transmitted to the computer to ensure the accuracy of the excitation frequency and amplitude. An acrylic (PMMA) tank is adopted as the liquid-filled container, as its transparency enables visual observation of liquid sloshing. Uniform stiffness satisfies the “rigid body” assumption in the theoretical model, and its low damping characteristic aligns with practical on-vehicle plastic reservoirs, ensuring engineering relevance. The container is filled with a specified depth of water. One end of the container moves up and down, driven by the vibration exciter, which causes the water to slosh, and the resulting fluid load excites the cantilever beam to vibrate. Due to the direct piezoelectric effect inherent in piezoelectric materials, a piezoelectric ceramic (PZT-5H) is bonded with epoxy resin to the fixed end of the cantilever beam—where strain is maximal—to form the PEH. The variable resistor is connected to the piezoelectric element, and the electrical output is measured by the data acquisition card. The collected data is then transmitted to the computer and recorded using LabVIEW.

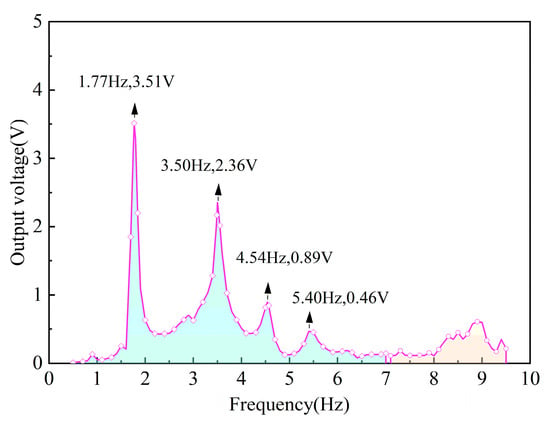

A frequency sweep test is performed to study the output characteristics of the PEH. The maximum effective stroke range of the vibration exciter used in the experiment is ± 10 mm. In the test, the vibration exciter performs sinusoidal motion at a given frequency with an amplitude of 10 mm. This ensures the test accuracy of the PEH’s response characteristics operating within the frequency range of 0.5–9 Hz. The root mean square (RMS) open-circuit voltage varying with the excitation frequency is shown in Figure 4. It clearly shows that when the excitation frequency is relatively low, the PEH produces virtually no voltage or energy output. However, as the excitation frequency increases, the PEH maintains a continuous voltage output. Within the frequency range of 1–7 Hz, there are four resonance peaks, and the RMS open-circuit voltages are 3.51 V, 2.36 V, 0.89 V and 0.46 V, respectively. Beyond 7 Hz, the PEH exhibits irregular voltage output, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The variation in the RMS open-circuit output voltage of the PEH with excitation frequency.

Among the four resonant peaks mentioned above, the excitation frequencies are 1.77 Hz, 3.50 Hz, 4.54 Hz and 5.40 Hz, which are almost the same as the frequencies of the first four antisymmetric liquid sloshing modes. In other words, the output of the PEH is mainly affected by the antisymmetric sloshing modes of the liquid, and when the liquid is sloshing, the cantilever beam undergoes forced vibration with the same frequency as the liquid sloshing.

Interestingly, the natural frequency of the cantilever beam also has an impact on the output of the PEH. Since the effect of the liquid sloshing force is mainly concentrated near the free end of the beam, this suggests that the forced motion mode of the beam is similar to its first-order vibration mode. The first-order natural frequency of the partially immersed beam is close to the second-order natural sloshing frequency of the liquid, so there is a small upward trend in the voltage output, but the value is much smaller than the voltage outputs of the adjacent antisymmetric sloshing modes.

The PEH converts mechanical energy into electrical energy based on the direct piezoelectric effect. An external resistor acting as a load directly influences energy dissipation and power output in the circuit. The relationship between output power and load resistance is nonlinear, increasing initially and then decreasing as load resistance increases. When the external resistance reaches a specific value, the circuit’s energy dissipation is minimised. An optimal load resistance test is conducted for the aforementioned four resonance frequencies. When the liquid sloshes in the 1st and 3rd sloshing modes, the optimal resistance is approximately 550 kΩ, whereas for the 5th and 7th sloshing modes, the optimal resistance is about 450 kΩ. in other words, due to the beam exhibiting the same vibration mode, the power output of the PEH exhibits a similar variation with load resistance, and the optimal resistance remains essentially unchanged. Therefore, in the subsequent studies, the resistance is set to 500 kΩ.

To verify the reliability of experimental data and the validity of the theoretical model, three independent repeated tests are conducted under the conditions of a 500 kΩ load and the reference model parameters. Table 1 summarises the statistical characteristics (population mean and population standard deviation) of the frequency from FFT analysis and peak voltage. Meanwhile, the first four orders of antisymmetric modes of liquid calculated based on FSI theory are presented, and the agreement between the mean FFT peak frequency and the theoretical antisymmetric sloshing frequency is evaluated using the relative error. The population mean is the arithmetic average of the three measured values.

Table 1.

Summary Table of Peak Voltage/FFT Frequency Statistical Characteristics and Theoretical-FFT Frequency Relative Error Across Four Modes.

The population standard deviation is calculated using the following formula:

where denotes the i-th test value and represents the mean value.

The relative error is calculated as follows:

From the statistical results, the standard deviations of both the peak RMS voltage and FFT peak frequency are less than 0.1, indicating excellent repeatability for the three independent tests. The effect of random errors on the experimental results is negligible, thus fully verifying the accuracy of the test data. Further analysis of the relative error shows that the deviation between the FFT peak frequency and the theoretically calculated antisymmetric liquid sloshing frequencies is less than 5%. This result clarifies that the resonance frequency of the PEH is mainly determined by the antisymmetric liquid sloshing frequency and simultaneously validates the established fluid–structure interaction theoretical model for predicting the PEH’s frequency characteristics.

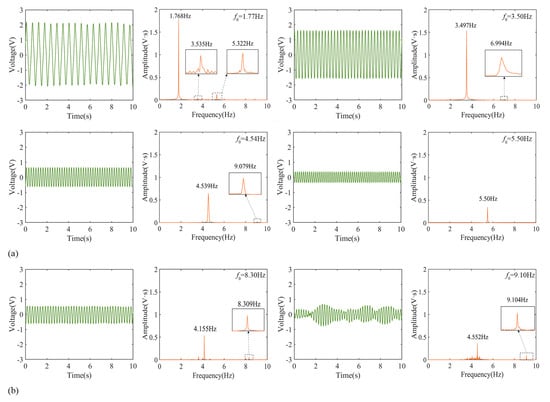

To further analyse the resonant characteristics of the PEH within this frequency band, Figure 5 presents the time-domain curve and frequency-domain characteristics of the voltage output of the PEH at the resonant peak frequency in a single load test.

Figure 5.

The voltage output of the PEH in both the time and frequency domains: (a) resonance frequencies; (b) three-dimensional sloshing mode.

It is observed that when the excitation frequency is lower than 7.5 Hz, the vibration of the beam and the output of the PEH are relatively stable, and the vibration frequency is mainly the liquid sloshing resonance frequency. When the excitation frequency exceeds 7.5 Hz, the liquid in the container exhibits a three-dimensional sloshing mode, and the longitudinal sloshing frequency of the liquid, acting as the PEH’s resonance frequency, is approximately half of the driving frequency. The liquid in the container always maintains large-amplitude sloshing and drives the PEH to generate a large voltage and energy output. Additionally, the figure shows that when the liquid undergoes three-dimensional sloshing, the vibration of the beam is unstable. Therefore, in the subsequent analysis of this paper, we mainly focus on the liquid two-dimensional sloshing and only test the frequencies within 7 Hz.

3. Results and Discussion

The output of the PEH is affected by the liquid sloshing and the resulting fluid load, both of which depend on the geometric parameters of the liquid and the cantilever beam. Therefore, experimental tests are performed to study the effects of geometric parameters of the liquid and the beam on the resonance and output characteristics of the PEH.

3.1. Liquid Geometric Parameters

- (1)

- Effect of the Immersion Depth

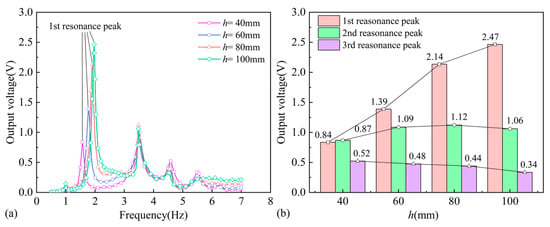

The variation in the immersion depth affects the liquid sloshing and the added mass of the beam, thereby altering the output of the PEH. The voltage output of the PEH with different immersion depths is shown in Figure 6a. When h = 40 mm, there are five obvious resonance peaks within the test frequency range, while when the immersion depth exceeds 80 mm, only three distinct peaks can be identified. Additionally, the magnitude of each resonance peak decreases gradually, and this attenuation becomes more pronounced as the immersion depth increases.

Figure 6.

Effects of the immersion depth on the PEH: (a) the voltage output; (b) the resonance peak values.

Figure 6b shows a comparison of the first three resonance peak voltages of the PEH. The peak voltages of different resonance orders exhibit different variations with the immersion depth. The frequency and the output voltage corresponding to the first resonance peak increase with the immersion depth, but the rates of increase for both the resonance frequency and peak voltage gradually decrease as the immersion depth increases. When the liquid sloshes in antisymmetric modes above the third order, the resonance frequencies remain basically the same at different immersion depths. The voltage of the second resonance peak is about the same when h > 60 mm. The third resonance peak voltage decreases gradually as the immersion depth increases, with no significant variation.

- (2)

- Effect of the Liquid Width

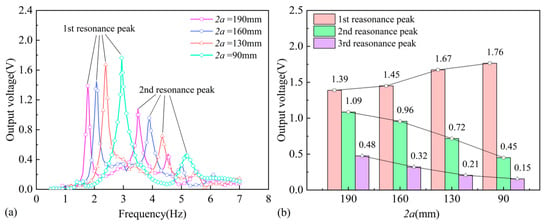

The natural frequency and the modal shape of liquid sloshing are also affected by the width of the container. In the experiment, the cantilever beam remained fixed at the midpoint of the liquid width. All other parameters are identical to the reference model, with only foam boards of varying thicknesses placed on the left or right side within the container to alter the liquid width. This setup is used to test the effect of liquid width upon the resonance characteristics of the PEH.

When the foam is placed at the excitation side of the container, the container exhibits the same motion pattern as the reference model. The voltage output and the resonance peak voltages of the PEH with different liquid widths are shown in Figure 7. Combined with Equation (6), it is observed that the resonance frequencies and bandwidth ranges of each order increase as the liquid width decreases. The voltage output at the first resonance peak increases as the liquid width decreases, while the voltages at the second and third resonance peaks both decrease.

Figure 7.

Effects of the liquid width with foam at the excitation side: (a) the voltage output; (b) the resonance peak values.

When the foam is installed at the hinge side of the container, the maximum excitation received by the container is identical to that of the reference model. The voltage output and the resonance peak voltages of the PEH are shown in Figure 8. The resonance frequencies with different liquid widths are consistent with those when the foam is placed on the excitation side of the container, and the variation in the resonance peak voltages with the liquid width is also essentially consistent. In other words, the effect on the resonance characteristics of the PEH is the same when the foam is located on either the hinge side or the excitation side of the container. In addition, when the foam is positioned on the hinge side of the container, the excitation received by the liquid is relatively larger, leading to slightly higher resonance peak voltages.

Figure 8.

Effects of the liquid width with foam at the hinge side: (a) the voltage output; (b) the resonance peak values.

Furthermore, through experimental observation, it is found that the longitudinal position of the beam has no significant effect on the PEH’s output. In fact, under different liquid widths and depths, there are at least two resonance peaks with relatively high voltage outputs, which can serve as a power source for small sensors. Among them, the immersion depth has a greater impact on the PEH’s peak output voltage. When the immersion depth is 100 mm, the maximum root mean square voltage reaches 2.46 V.

3.2. Dimensions of the Beam

- (1)

- Effect of the Beam Thickness

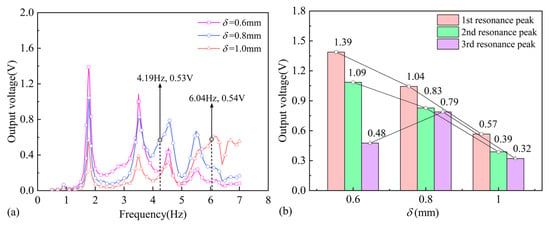

The generalised mass and stiffness of the beam vary with its thickness, thereby influencing how the liquid affects the resonance characteristics. The voltage output and the resonance peak voltages of the PEH with different beam thicknesses are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Effects of the beam thickness: (a) the voltage output; (b) the resonance peak values.

It is observed that the varied beam thickness does not alter the resonance frequencies of the PEH, which are determined by the liquid sloshing frequencies, but the variation in the resonance peak voltages follows a different pattern. As the beam becomes thicker, the impact of the fluid force diminishes, resulting in a gradual decrease in the voltage output of the first two resonance peaks. However, when the thickness of the beam is 0.8 mm, its first-order immersed natural frequency is close to the third-order antisymmetric natural sloshing frequency of the liquid, leading to a notable enhancement in the third and fourth resonance peak voltages. When d = 1.0 mm, the first-order immersed natural frequency of the beam is close to the fourth-order antisymmetric natural sloshing frequency of the liquid, resulting in a rapid increase in the fourth to sixth resonance peak voltages, which even exceed those of the first resonance peak.

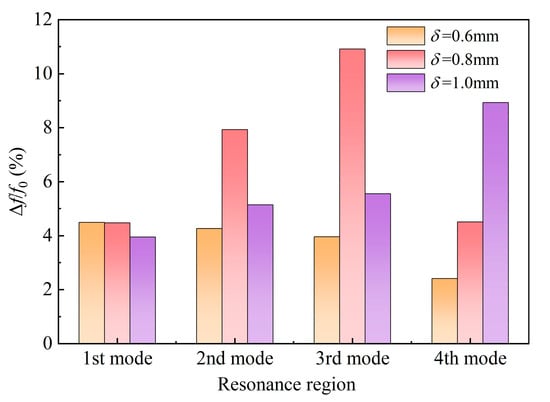

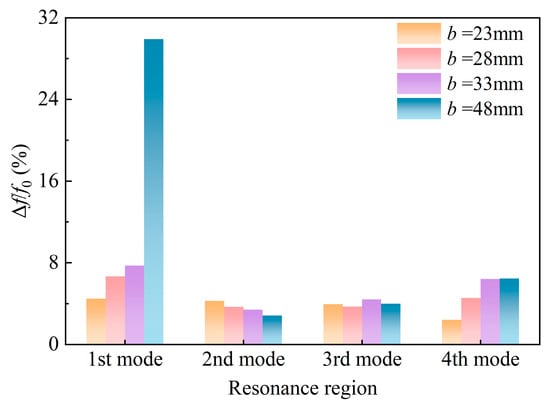

To further clarify the phenomenon that “the bandwidth increases significantly when the natural frequency of the partially immersed beam is close to the liquid natural sloshing frequency”, Figure 10 quantifies this effect using the bandwidth coefficient (i.e., Δf/f0) across different resonance regions. The bandwidth coefficient is defined as the ratio of the effective bandwidth Δf to the central frequency f0, where the central frequency f0 is the peak excitation frequency, corresponding to the maximum voltage output amplitude Vmax; the effective bandwidth Δf is determined using the half-power bandwidth method. Specifically, two characteristic frequency points on both sides of the central frequency f0 are identified at which the voltage amplitude decays to Vmax/(≈0.707Vₘₐₓ), and the interval between these two frequency points is defined as the effective bandwidth Δf.

Figure 10.

Bandwidth coefficient of beams of varying thicknesses in the resonance region.

As shown in Figure 10, when the first-order immersed natural frequency of the 0.8 mm thick beam is close to the third-order antisymmetric natural sloshing frequency, its bandwidth coefficient is nearly twice that of other resonance peaks, reaching a maximum of approximately 11%. When the first-order immersion natural frequency of the beam with a thickness of 1 mm is close to the fourth-order antisymmetric natural sloshing frequency, its bandwidth coefficient is more than three times higher than that at its first-order resonance peak, reaching 8.93%.

- (2)

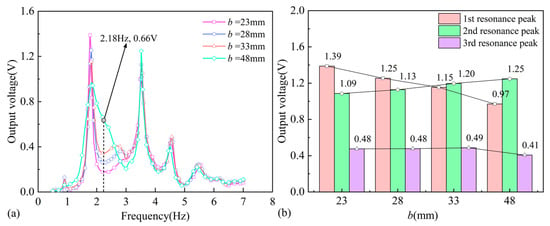

- Effect of Beam Width

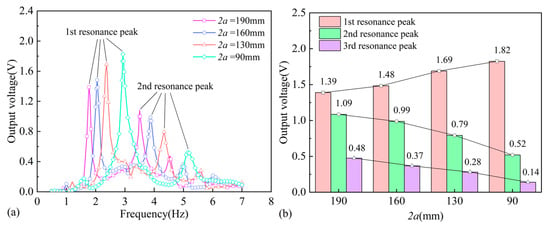

The width of the beam does not change its natural frequency in vacuum, but according to Equation (17), it affects the added mass acting on the beam, thereby changing its immersion natural frequency.

The voltage output variation and the resonance peak voltages of the PEH with different beam widths are shown in Figure 11. As shown in Figure 11a, when the width of the beam varies, the voltage outputs of the PEH show the same variation trend with the excitation frequency, with no change in the resonance frequencies. The voltage output of the first resonance peak decreases as the beam becomes wider, while the second resonance peak voltage increases gradually. As the beam becomes wider, the added mass produced by the liquid increases, causing the first-order immersed natural frequency of the beam to decrease. Consequently, the small peak between the first and second resonance frequencies shifts forward, and its voltage output also increases gradually.

Figure 11.

Effects of the beam width: (a) the voltage output; (b) the resonance peak values.

When the beam width is 48 mm, the first-order immersed natural frequency of the beam is close to the first-order liquid natural sloshing frequency, which significantly increases the bandwidth near the first resonance peak. Furthermore, the beam width has a negligible effect on the third-order and higher resonance peaks, and the voltage output curves are basically coincident.

As shown in Figure 12, the bandwidth coefficient of the first-order resonance peak for the 48 mm-wide beam is nearly four times as high as that corresponding to other resonance peaks, reaching 29.89%. Therefore, an optimal beam parameter can be tailored to the sloshing frequency of the liquid, thereby enhancing the resonance bandwidth and peak voltage of the PEH.

Figure 12.

Bandwidth coefficient of beams of different widths in the resonance region.

4. Conclusions and Prospect

This paper proposes a cantilever beam piezoelectric energy harvesting system based on the sloshing motion of a liquid-filled container. The system simulates the low-frequency vibrations generated by vehicles during driving through unilateral base excitation and harnesses the sloshing motion of the liquid within the container to harvest energy.

To investigate the combined effects of the natural frequencies of the liquid and the partially submerged beam on energy harvesting, a fluid–structure interaction (FSI) model is established. A comparison of calculated frequencies from the FSI model with experimentally measured frequencies using FFT analysis indicates that the resonant characteristics of the piezoelectric energy harvester are predominantly determined by the liquid’s antisymmetric sloshing modes.

The study investigated the effect of liquid geometric parameters (depth/width), container configuration, and cantilever beam position. Findings revealed that under various liquid depth and width conditions, the PEH achieved relatively high voltage outputs at no fewer than two resonance peaks, demonstrating potential for powering small sensors across a broad frequency range. In addition, beam placement had a negligible impact on output characteristics, further highlighting the structural design’s flexibility.

When the immersed natural frequency of the beam approaches a liquid natural sloshing frequency, both the peak voltage and effective bandwidth of the PEH significantly increase. Experimental results indicate that for a 0.8 mm thick beam, when its first-order immersed natural frequency nears the third-order antisymmetric natural sloshing frequency of the liquid, the bandwidth coefficient is nearly doubled compared with that of other resonance peaks, reaching approximately 11%; for a 1 mm thick beam, when its first-order immersed natural frequency approaches the fourth-order antisymmetric natural sloshing frequency of the liquid, the bandwidth coefficient is more than tripled compared with that at its first-order resonance peak, reaching 8.93%; for a 48 mm wide beam, the first-order peak bandwidth coefficient increases nearly fourfold compared with that corresponding to other peaks, reaching 29.89%. Based on this mechanism, immersed beams with natural frequencies matched to different liquid sloshing conditions can be designed. This enables energy harvesters to achieve multi-condition continuous power generation, thereby enhancing the overall output performance of the system.

This study focuses on a regular cubic liquid-filled container, adopting simplified geometric boundaries to perform controllable studies of the PEH’s response characteristics. It should be noted, however, that in practical scenarios, on-vehicle fluid containers often exhibit complex geometries, and fluid motion under actual operating conditions tends to display nonlinear sloshing characteristics. These complex factors were not systematically incorporated in this experiment, potentially limiting the applicability of the findings to irregular boundaries and strongly nonlinear operating conditions, thus requiring further validation. This limitation primarily stems from the introduction of multivariable coupling effects (e.g., boundary friction and nonlinear variations in fluid inertial forces) associated with complex geometries and non-linear sloshing. Incorporating these factors in the initial research phase would significantly increase the complexity of experimental design and the difficulty of variable control, making it harder to focus on verifying the core mechanism. Future studies can be supplemented under complex boundary and nonlinear oscillation conditions by implementing modular upgrades to the experimental apparatus (e.g., replacing non-standard cavity modules) combined with non-linear dynamic modelling approaches. This would address the current research limitations and facilitate the promotion of the practical engineering application of the findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.S.; methodology, M.S.; Software, Y.S.; investigation, X.D.; data curation, X.D.; validation, M.S. and Z.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S. and X.D.; writing—review and editing, M.S. and R.S.; visualisation, Y.S.; formal analysis, R.S.; supervision, Z.Z. and R.S.; project administration, M.S.; resources, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China (Grant no. ZR2022QA058 and ZR2022MA069).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sezer, N.; Koç, M. A comprehensive review on the state-of-the-art of piezoelectric energy harvesting. Nano Energy 2021, 80, 105567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.K.; Baredar, P.V. Analysis on piezoelectric energy harvesting small scale device—A review. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2017, 31, 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, I.; Kwon, D.S.; Yang, S.; Kim, H. Development of low frequency hybrid harvester for vehicle vibration energy harvesting. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Micro and Miniature Power Systems, Self-Powered Sensors and Energy Autonomous Devices (PowerMEMS), Tønsberg, Norway, 18–21 November 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, S.; Tan, M. Dynamic interactions of an integrated vehicle–electromagnetic energy harvester–tire system subject to uneven road excitations. Acta Mech. Sin.-Prc. 2017, 2, 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.S.; Yoo, I.; Yang, S.; Kim, H. Coil vibration type electromagnetic energy harvester for vehicle vibration energy harvesting. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Micro and Miniature Power Systems, Self-Powered Sensors and Energy Autonomous Devices (PowerMEMS), Tønsberg, Norway, 18–21 November 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbonna, V.E.; Popoola, A.P.I.; Popoola, O.M. Piezoelectric ceramic materials on transducer technology for energy harvesting: A review. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 1051081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhong, J.; Lee, C.; Lee, S.W.; Lin, L. A comprehensive review on piezoelectric energy harvesting technology: Materials, mechanisms, and applications. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2018, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clementi, G.; Cottone, F.; Michele, A.D.; Gammaitoni, L.; Mattarelli, M.; Perna, G.; López-Suárez, M.; Baglio, S.; Trigona, C.; Neri, I. Review on innovative piezoelectric materials for mechanical energy harvesting. Energies 2022, 15, 6227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yafeai, D.; Darabseh, T.; Mourad, A.H.I. A state-of-the-art review of car suspension-based piezoelectric energy harvesting systems. Energies 2020, 13, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfrink, R.; Matova, S.; Nooijer, C.; Jambunathan, M.; Goedbloed, M.; Molengraft, J.; Pop, V.; Vullers, R.J.M.; Renaud, M.; Schaijk, R. Shock induced energy harvesting with a MEMS harvester for automotive applications. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM 2011), Washington, DC, USA, 5–7 December 2011; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 29.5.1–29.5.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, I.; Kwon, D.S.; Yang, S.; Kim, H. Development and optimization of a new end-cap tire-strain piezoelectric energy harvester. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 303, 118109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuo, J.; Zheng, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, B.; Qi, W. Design of a quasi-zero stiffness vibration isolation and energy harvesting integrated seat suspension. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2025, 13, 3–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Saad, A.A.; Mazlan, A.Z.A. Design and experimental study of piezoelectric energy harvester from driving motor system of electric vehicle based on high-low excitation frequency profiles. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2025, 31, 3231–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Shi, Y.; Cui, H.; Shi, J. Research on piezoelectric energy harvester based on coupled oscillator model for vehicle vibration utilizing a L-shaped cantilever beam. Smart Mater. Struct. 2020, 29, 075014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlehdar, M.; Kasaeian, A.; Safaei, M.R. Energy harvesting from fluid flow using piezoelectrics: A critical review. Renew. Energy 2019, 143, 1826–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.W.; Burns, J.R.; Kammann, S.M.; Powers, W.B.; Welsh, T.R. The Energy harvesting eel: A small subsurface ocean/river power generator. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2001, 26, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Shan, X.; Lv, F.; Xie, T. A study of vortex-induced energy harvesting from water using PZT piezoelectric cantilever with cylindrical extension. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, S768–S773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutsuda, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Doi, Y.; Moriyama, Y. Application of a flexible device coating with piezoelectric paint for harvesting wave energy. Ocean Eng. 2019, 172, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, J.; Lin, M.; Su, O.; Qin, L. An ultralow frequency, low intensity, and multidirectional piezoelectric vibration energy harvester using liquid as energy-capturing medium. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2020, 117, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabavi, S.F.; Farshidianfar, A.; Afsharfard, A. Novel piezoelectric-based ocean wave energy harvesting from offshore buoys. Appl. Ocean Res. 2018, 76, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, S.; Nili-Ahmadabadi, M.; Tavakoli, M.R.; Tikani, R. Energy harvesting from longitudinal and transverse motions of sea waves particles using a new waterproof piezoelectric waves energy harvester. Renew. Energy 2021, 179, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.K.; Roychowdhury, S.; Arumuru, V. Fluid sloshing augmented parametric excitation for enhanced piezoelectric vibration energy harvesting. Sens. Actuat. A-Phys. 2025, 395, 117061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.J.; Kim, J.; Kim, D. Slosh-induced piezoelectric energy harvesting in a liquid tank. Renew. Energy 2023, 206, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.; Mcmanus, K. Perception of low frequency vibrations by heavy vehicle drivers. J. Low Freq. Noise Vib. Act. Control. 2002, 21, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalili, M.M.; Motavasselolhagh, M.; Fatehi, R.; Sefid, M. Investigation of sloshing effects on lateral stability of tank vehicles during turning maneuver. Mech. Based Des. Struc. 2022, 50, 3180–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Vijayakumar, V.; Naduvilethil, R.T. Numerical analysis of sloshing induced bouncing and pitching motions in a tank-truck during braking conditions. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, Future and Recent Advances in Mechanical Engineering: Frame (2024), Kurukshetra, India, 15–17 October 2024; American Institute of Physics: College Park, MD, USA, 2025; Volume 3330, p. 020017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, X.; Peng, P.; Zhou, Z.; Gao, Z. Experimental Study on the Sloshing of a Rectangular Tank under Pitch Excitations. Water 2024, 16, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzi, E. Hydroelectromechanical modelling of a piezoelectric wave energy converter. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 472, 20160715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celebi, M.S.; Akyildiz, H. Nonlinear modeling of liquid sloshing in a moving rectangular tank. Ocean Eng. 2002, 29, 1527–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Lin, P. Numerical study of ring baffle effects on reducing violent liquid sloshing. Comput. Fluids 2011, 52, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sader, J.E. Frequency response of cantilever beams immersed in viscous fluids with applications to the atomic force microscope. J. Appl. Phys. 1998, 84, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuck, E.O. Calculation of unsteady flows due to small motions of cylinders in a viscous fluid. J. Eng. Math. 1969, 3, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirstein, S.; Mertesdorf, M.; Schönhoff, M. The influence of a viscous fluid on the vibration dynamics of scanning near-field optical microscopy fiber probes and atomic force microscopy cantilevers. J. Appl. Phys. 1998, 84, 1782–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, R.; Hatami, H.; Golzar, F.G.; Tariverdilo, S.; Rezazadeh, G. Coupled vibration of a cantilever micro-beam submerged in a bounded incompressible fluid domain. Acta Mech. 2013, 224, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).