Abstract

Awareness of cosmetic product safety has grown in recent years. Certain ingredients and impurities, including heavy metals, may pose health risks to consumers. Heavy metals can be present in cosmetics as either intentional ingredients or contaminants, making strict monitoring of these substances essential. This review assesses the toxicological implications of heavy metals in cosmetics, with a focus on advancements in analytical quantification methods, health risk assessment, and emerging non-animal-based approaches for evaluating toxicological profiles. Recent studies have detected traces of toxic metals, some exceeding permissible levels, in various cosmetic products, highlighting the need for ongoing monitoring programs to address heavy metal contamination. Additionally, the review emphasizes the importance of reliable and validated exposure assessment models and non-animal methodologies for determining systemic toxicity.

1. Introduction

Cosmetic products have been used since ancient times, with every historical era featuring its own particularities. During the 20th and 21st centuries, the beauty and personal care products industry has flourished, introducing new and innovative items. As a result, the cosmetics market today comprises various products, including lipsticks, mascara, eye shadows, face powders, hair products, and mainly skin care products [1]. With the mass production of cosmetics and increased demand, concerns about product safety has emerged. Several incidents associated with harmful ingredients from cosmetics ultimately prompted President Franklin D. Roosevelt to introduce the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 [2].

Cosmetics usually contain a long list of ingredients (organic and inorganic compounds, herbal extracts, oils), so human safety is a significant concern, especially for products applied daily or on large surfaces or products designed for infants. The issue of personal care products becoming a source of exposure to heavy metals has gained attention over the past two decades [1,3]. Risk assessment for human cosmetics is based on the toxicological profile of the ingredients used and their exposure level. The current cosmetic legislation lists the permitted colorants, preservatives, and UV filters in the annexes, as well as the prohibited and restricted compounds [4].

This review aims to synthesize current knowledge on the toxicological impact of heavy metals in cosmetics. Metals such as cadmium (Cd), arsenic (As), lead (Pb), mercury (Hg), chromium (Cr), nickel (Ni), and cobalt (Co) are recognized for their toxic potential. Multiple studies have documented the presence of these metals in beauty and self-care products (skin-whitening creams, lotions, foundations, lip-care products, eye makeup) [5]. Even essential metals like iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), and copper (Cu) can have a negative impact on human health, in excess [6]. Significant progress has been made in recent years. Regulatory authorities in the USA, the EU, and other regions have imposed restrictive limits to ensure product safety and quality. Public awareness regarding these issues has also increased. Nevertheless, recent studies continue to report the presence of heavy metal contaminants in cosmetic products [7,8,9]. These contaminants can pose serious health risks if they accumulate in the body. They can cause neurological, cardiovascular, renal, hematological, and skin disorders and also exhibit carcinogenic effects. Some are also identified as endocrine disruptors and may cause reproductive disorders [10,11].

Related to cosmetics, safety evaluation is a complex process that consists of several steps, namely hazard identification (identifying the target of toxicity), the evaluation of the dose–adverse effect relationship, exposure assessment, and, finally, using combined data to characterize the risk for a human population. The 21st century has brought significant changes in European legislation regarding the safety assessment of cosmetic products. Various replacement alternatives have been developed and validated in the context of banning animal testing for cosmetic ingredients and products [4]. Moreover, the safety assessment of cosmetics presents significant challenges because numerous variables influence exposure risk. These include factors that affect dermal penetration, such as cosmetic formulation characteristics, particle size, and the properties of the exposed skin area [11].

Therefore, given the widespread use of cosmetics, the potential adverse health effects, and the complexity of related issues, research in this field is essential.

2. Methodology

A comprehensive literature search was performed across multiple electronic databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar, utilizing keywords such as “heavy metals”, “cosmetics”, “risk assessment”, “skin sensitization”, “carcinogenic risk”, “NAMs”, “cytotoxicity”, and “genotoxicity”. Original articles, reviews, and book chapters published from 1990 to the present were included.

3. Heavy Metals in Cosmetics

Several studies have identified heavy metals in various cosmetic or personal hygiene products intended for daily use. Metals in cosmetics may originate from primary ingredients, color additives, or the use of metal-coated equipment during the manufacturing process. Some of these elements are contaminants, while others are added intentionally. For example, aluminum salts are used in antiperspirant products, and the proportion of zinc oxide in mineral powders or sunscreen formulations is significant [12]. In cosmetics, zinc is typically incorporated as salts, zinc oxide, or complexes due to its sunscreen, anti-acne, astringent, and antiseptic properties [13]. Certain metals, such as Zn, are incorporated in the form of nanoparticles, which present a greater potential health risk because their small size enables them to penetrate the skin barrier more readily [11]. In other skin-care products, metal composites can be introduced for their ability to target melanogenesis and whiten the skin [14]. Furthermore, using raw herbal material from polluted areas can increase metal contamination [1]. Nevertheless, pigments and mineral solid fillers remain the primary source of heavy metal contamination in cosmetic products. Therefore, eye shadows, as highly pigmented cosmetics, tend to contain more heavy metal contaminants. Some studies have established a connection between the color of the product and the concentration of heavy metals [15,16,17]. Mercury has been detected in two forms, inorganic and organic, in cosmetic products, such as skin whitening soaps and creams. Organic mercury compounds (phenylmercuric compounds) can serve as preservatives in products such as eye makeup removers and mascaras [18].

All categories of cosmetic products have been screened regarding their heavy metal content. Kohl is a popular eye cosmetic, especially in the Middle East, documented since Ancient Egyptian times. Several studies have confirmed the presence of high lead concentrations in most of these traditional products, which are associated with significant risks for human health. These hazardous products are available worldwide, including in Europe and the USA [19,20]. Mokashi et al. [21] pointed out that the use of traditional kohl (eyeliner) products among immigrant populations presents a high risk of lead poisoning, with some samples showing lead concentrations up to 800,000 parts per million (ppm) [21]. Moreover, in these cultures, children are frequently exposed to kohl or similar products, which can determine hematological toxicity, neurological damage, and alteration of kidney function [22]. Bruyneel et al. [23] reported a case of lead poisoning associated with prolonged exposure to lead sulfide from kohl [23].

The literature search revealed that most articles analyzed a relatively low number of samples. Still, there are also extensive studies that provide valuable and statistically significant information not only to regulatory authorities and policymakers but also to regular consumers.

Piccinini et al. [3] investigated the lead content in 223 lip products, purchased in 15 EU member states [3]. The FDA (Food and Drug Administration) conducted surveys between 2010 and 2013, evaluating the lead content in lip products (over 400 samples) and externally applied cosmetics (120 samples) [24,25]. The US Agency also conducted surveys focusing on other types of cosmetics (eye shadows, blushes, face paints, lotions, mascaras, foundations, powders, shaving creams), analyzing the heavy metal content (As, Cd, Cr, Co, Pb, Hg, and Ni) in 150 cosmetic products of 12 types [26]. Hamann et al. [27] analyzed the mercury content in 549 skin-lightening products using a portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometer. 6.0% of the products presented a mercury level above 1000 ppm [27]. Al-Ashban et al. [20] examined 107 kohl samples in Saudi Arabia and found high levels of lead, which correlated with high lead blood concentrations [20]. Iwegbue et al. [28] assessed the concentration of heavy metals in 160 samples of facial cosmetics from Nigeria (lip products, eye shadows and pencils, mascaras, blushes, and face powders). Also, they calculated the Margin of Safety (MoS) for human risk assessment. They concluded that products produced in Asian countries exhibited higher levels of heavy metals compared to those from Europe and the USA. Still, in most cases, the MoS indicated a low consumer risk [28].

Corazza et al. [29] investigated the levels of heavy metals (nickel, cobalt, and chromium) in toy makeup products. Chromium exceeded the maximum limit (5 ppm) in 53.8% of the samples, with higher levels found in powdery products. Cobalt and nickel were also present in the samples investigated. Given that children are more prone to sensitization reactions, which can compromise the integrity of the skin barrier and increase systemic exposure, special attention must be given to the quality requirements of these products [29].

Face paint cosmetics represent a category of products used by stage performers and other individuals who require a distinctive appearance. Frequent use and the large amount of product applied to the skin increase the risk for cumulative harmful effects [30]. Wang et al. [31] found significant levels of heavy metals in this type of product, with over 25% of the tested samples associated with a carcinogenic risk that exceeded the maximum acceptable limit. Chromium was identified as the primary contributor to this high risk [31]. Studies performed with artificial sweat extracts of face paint revealed the potential toxicity of these products, which decreased cell viability in a 3D skin model and produced changes in the gene expression profiles, most of which were inflammation-relevant genes (e.g., TNF and IL-17 gene) [30].

Due to their high toxicity, lead, mercury, arsenic, and cadmium are heavy metals causing a significant public health threat. In contrast, other elements are essential minerals in small quantities, involved in specific processes in the human body (cobalt, copper, manganese, chromium) [32].

Lead is a highly toxic metal that adversely affects hematopoiesis, impairs renal function, and induces neurological disorders. Children, due to their greater absorption capacity, and pregnant women are particularly susceptible to lead exposure. Lead inhibits heme synthesis, disrupts the balance of oxidant and antioxidant systems, and triggers oxidative stress, as well as inflammatory responses [18,33].

Mercury induces neurotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, and hepatotoxicity. Inorganic mercury compounds present a lower toxicity compared to organic compounds. Inorganic mercury accumulates in the kidneys, resulting in renal injury. In contrast, organic mercury, due to its greater lipophilicity, crosses the blood–brain barrier and exhibits higher neurotoxicity than inorganic forms. Mercury binds to thiol groups, inactivates enzymatic systems, and promotes reactive oxygen species production and oxidative stress. Mercury chloride was detected in skin brightening creams, due to its ability to inhibit tyrosinase activity [33].

Cadmium is a highly toxic metal, classified as a carcinogen. It binds to cystein-rich proteins (such as metallothionein) and other metal transporters and decreases the absorption of Zn, Ca, and Cu. Cd causes hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, and painful degenerative bone disease [33,34].

Chromium in the trivalent state is required in trace amounts for lipid and protein metabolism, whereas hexavalent chromium is a group 1 carcinogen. The primary mechanisms of chromium toxicity and carcinogenicity are genomic instability, DNA damage, and oxidative stress [33].

Arsenic can be found in various forms (organic, inorganic, and metalloid). The toxicity of inorganic species is higher compared to organic species, and As3+ is more toxic than As5+ [33]. Arsenic induces epigenetic alterations and DNA damage, thereby increasing cancer risk. Additionally, arsenic exposure is associated with neurotoxicity and skin disorders, including hyperpigmentation [35].

Nickel binds to keratin, accumulates in the stratum corneum, and is associated with allergic reactions. It is also classified as a carcinogenic and causes neurotoxicity [18,36].

Aluminum accumulates in the body following repeated exposure. It deposits in bone tissue, resulting in osteomalacia, and in the brain, where it contributes to the development of Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Al also affects breast tissue morphology [36].

Iron is an essential element present in the structure of cytochromes and oxygen-transport proteins. Excessive iron intake results in unbound iron, which promotes the generation of free radicals and leads to cellular damage [34].

Copper is an essential element that participates in numerous physiological and metabolic processes, including those occurring in the skin. It promotes collagen production and contributes to the synthesis and stabilization of the skin’s extracellular matrix. Consequently, GHK-Cu, a copper tripeptide with the amino acid sequence glycyl-L-histidyl-L-lysine, and copper gluconate are incorporated into skincare formulations for their anti-aging properties [37]. Nevertheless, excessive copper can induce oxidative stress-related tissue damage [38].

Zinc is also an essential element that serves as a cofactor for numerous enzymes. In cosmetics, zinc is typically incorporated as salts, zinc oxide, or complexes due to its sunscreen, anti-acne, astringent, and antiseptic properties [13]. Zn compounds are considered safe in cosmetic formulations, when the maximum concentrations are respected [39]. Water soluble zinc salts are limited to a concentration of 1%, due to their irritative potential [36]. Excessive zinc exposure can cause gastrointestinal disorders and zinc-induced copper deficiency [40].

Table 1 presents the primary health risks associated with heavy metals in cosmetic products. These risks result from systemic absorption of metals following dermal exposure to such products. Prolonged and repeated use of cosmetics increases these risks due to cumulative effects.

Table 1.

Heavy metals in cosmetics—potential health risks after exposure to cosmetics.

4. Heavy Metal Limits in Cosmetic Products

While intact skin functions as a barrier that restricts the penetration of cosmetic product ingredients, trace quantities of heavy metals can nonetheless be absorbed into the body [14]. Heavy metals in cosmetic products can impact human health through direct action on the skin surface after exposure or absorption into the bloodstream, resulting in accumulation and organ-specific toxicity. Skin absorption is typically the primary exposure route for cosmetics, especially when the products are applied to extensive body areas, as with sunscreen. However, in some instances, oral ingestion can become a significant exposure pathway, particularly for lip products or due to hand-to-mouth behaviors in young children [32,53]. Consequently, regulatory authorities worldwide have established maximum permissible limits for heavy metals in cosmetics. However, these limits may differ between countries.

Regulation (EC) No. 1223/2009 in Europe establishes safety and high-quality standards for cosmetic products by defining maximum acceptable concentrations of heavy metals. According to current European legislation on cosmetics, the list of substances prohibited from being used intentionally in the preparation of cosmetic products includes various heavy metals (metallic ions or salts), such as Sb, As, Cd, Hg, and Pb. The maximum permissible concentration for water-soluble zinc salts is 1%. Zinc phenolsulfonate is permitted in deodorants, antiperspirants, and astringent lotions at concentrations up to 6%. Aluminum zirconium chloride hydroxide complexes may be used in antiperspirants, with a maximum concentration of 20%. Iron compounds are authorized as color additives in cosmetics. Mercuric compounds, such as thiomersal and phenylmercuric salts, are permitted as preservatives in eye products, with a maximum admitted Hg concentration of 0.007% [60].

The European country that enforces the lowest guidance limits is Germany: 0.1 mg/kg for Cd and Hg, 0.5 mg/kg for As and Sb, and 2 mg/kg for Pb [61].

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration regulates cosmetic products under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA), enacted in 1938. The Modernization of Cosmetics Regulation Act (MoCRA), introduced in 2022, emended existing legislation to grant the FDA authority to inspect safety records for cosmetic products and to mandate recalls of products that present a public health threat [62]. The established limits are 3 ppm for As, 1 ppm for Hg, 10 ppm for Pb in lip products and externally applied cosmetics, or 20 ppm for lead in color additives [61].

Canada enforces comprehensive safety measures and restrictions regarding heavy metals as impurities in cosmetic products. Lead, arsenic, cadmium, mercury, stibium, and chromium are prohibited as intentional ingredients. The maximum allowable limits are 10 ppm for Pb, 3 ppm for As, 3 ppm for Cd, 1 ppm for Hg, 5 ppm for Sb [63].

The Chinese regulatory maximum heavy metal limits in cosmetic products are 2 mg/kg for As, 5 mg/kg for Cd, 10 mg/kg for Pb, and 1 mg/kg for Hg [61].

5. Analytical Methods to Identify and Quantify Heavy Metals (Hazard Identification)

Atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS), inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES), and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) are analytical techniques often used to quantify the heavy metal content in various samples.

In AAS, samples are converted to ground-state atoms that absorb radiation at specific wavelengths proportional to their concentration. Atomization methods include flame atomic absorption spectroscopy (FAAS) and graphite furnace atomic absorption spectroscopy (GFAAS), which vaporize the sample in a heated graphite tube. FAAS offers a favorable cost-effectiveness ratio, whereas GFAAS achieves lower detection limits (Figure 1) [17]. For mercury analysis, cold-vapor atomization (CV-AAS) serves as an appropriate alternative to FAAS and GFAAS. In this method, the mercury solution is acidified, and ionic mercury is reduced by stannous chloride to ground-state mercury atoms. An inert gas transports these atoms to an absorption cell [64]. Ho et al. [65] used CV-AAS to evaluate mercury contamination in facial lightening creams [65].

Figure 1.

ASS and ICP techniques—characteristics.

ICP-OES and ICP-MS use an inductively coupled argon plasma as an excitation source for the nebulized sample. The main advantages of ICP technology are its capacity for multi-element detection and lower detection limits. ICP-MS can quantify even ultra-trace concentrations of analytes. Furthermore, ICP-MS has the ability to differentiate between isotopes (Figure 1) [17]. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) employs ICP-MS for the quantification of trace heavy metals in finished cosmetic formulations [66].

Most analytical methods require sample solubilization before the analysis. Digestion is achieved with a mixture of strong inorganic acids and oxidant agents, and the process can be microwave-assisted for improved results [67]. Sample preparation can be challenging and time-consuming, increasing the risks of contamination and analyte loss. Sample dilution can reduce the sensitivity. Furthermore, the process typically involves using acids and aggressive reagents, which disagree with environmentally friendly protocols. Several experimental factors can influence the outcome (the sample weight, the mixture of acids, and temperature). The HR CS GF AAS (High-Resolution Continuum Source Graphite Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectrometry) technique allows direct sample analysis from different matrices (biological materials, foods, environmental samples). This may require a pretreatment step (e.g., drying), especially for biological materials. However, the method development process (e.g., calibration, minimization of matrix effects) can be complicated in some cases [68]. Compared to other AAS methods, HR CS GF AAS offers improved signal stability and superior background correction (due to the possibility of scanning across the analytical wavelength), requiring only one radiation source for all elements. Another essential advantage of this technique is that multielemental analysis can be performed for metals with nearly adjacent absorption lines, which are within the spectral interval of the CCD (Charge-Coupled Device) detector [69,70,71,72]. Several elements, including Co, Cr, Fe, and Ni, exhibit rich in atomic lines in the UV-VIS region, making it feasible to determine them simultaneously. Pasias et al. [72] reviewed publications from 2000 to 2020 concerning the simultaneous multi-elemental analysis using HR-CS-GFAAS. They concluded that most studies were limited to the determination of two elements. This limitation represents the primary drawback of the technique, compared to ICP technology [72]. The method was used to assess heavy metal contents in sunscreen products (lead and chromium) [69] and in lipstick samples (lead) with accurate results, comparable with those obtained using the acid digestion procedure [73].

Another technology that can be successfully applied for elemental analysis and quantification of heavy metals in cosmetic products is X-ray fluorescence (XRF) [74]. The main issue with this technology is identifying suitable reference materials, similar to the samples’ matrix [67]. Bairi et al. [75] developed a rapid and cost-effective method to quantify Zn and Ti in sunscreen samples using a portable X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy analyzer. The results were compared to those obtained using ICP-MS, with good correlation [75].

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) represents the process in which energy is transferred nonradiatively between a donor excited fluorophore and a nearby acceptor fluorophore. FRET-based assays can be employed for monitoring heavy metals in complex matrices, allowing the simultaneous assessment of multiple contaminants. These assays involve three types of systems: small-organic-molecule-based systems, nanomaterial-based systems, and fluorescent-protein-based systems [76]. FRET-based sensors are engineered to interact with target compounds, resulting in altered distances between donor and acceptor molecules, which correspond to changes in the fluorescence intensity of the acceptor [77].

FRET-based chemosensors have been used to detect lead rapidly. Ghosh et al. [78] developed a chemosensor based on rhodamine (RNPC) (Rhodamine-Naphthalimide Conjugate) and used it to estimate Pb2+ content in lipstick samples by measuring the fluorescence of the complex RNPC-Pb2+. Chemosensors have the advantage of being both sensitive and selective [78].

Radwan et al. [79] prepared optical chemosensors specific for Cd2+ and Co2+ in cosmetic products and used spectrophotometric and digital image-based colorimetric analysis for detection and quantification. They attached the specific chromophores to mesoporous silica nanospheres [79]. Chemosensors were also developed to monitor mercury in cosmetics [80,81].

The search for better techniques that are cost-effective, but also user- and environment-friendly, has led to the development of quantitative instrument-free detection devices. One example is distance-based paper microfluidic devices (DμPADs). They combine the characteristics of the two technologies. Developing microfluidic paper-based analytical devices involves creating hydrophobic barriers on the sheet of hydrophilic paper to create capillary channels and define fluidic pathways. At the same time, distance-based detection relies on the measurement of the zone where a color change occurs, the length of this zone being proportional to the analyte concentration [82,83]. Manmana et al. [84] developed an ion-exchange DμPADs to quantify heavy metals in herbal supplements and cosmetics, using 2-(5-bromo-2-pyridylazo)-5-[N-npropyl-N-(3-sulfopropyl)amino]phenol (5-Br-PAPS) as the anionic metallochromic reagent [84].

Paper-based microfluidic platforms have also been developed for the detection of other heavy metals and demonstrate significant potential for application in the analysis of cosmetic products [85,86,87,88].

Table 2 presents a selection of studies that examine the heavy metal content in cosmetics using various analytical methods.

Table 2.

Selection of studies evaluating the heavy metal content in cosmetic products.

6. Exposure Assessment for Heavy Metals in Cosmetics

As presented above, the quantitative and qualitative evaluation of heavy metals in cosmetic products has represented a popular research subject. However, developing robust and reliable tools and mathematical models to quantify systemic exposure and risk assessment parameters is equally essential. Clinical evidence of systemic heavy metal toxicity following cosmetic use further underscores this necessity [36,125,126,127,128].

For example, Guillard et al. [126] reported a clinical case of hyperaluminemia in a woman after four years of antiperspirant use containing aluminum chlorohydrate [126]. Elevated urinary mercury concentrations and a high prevalence of symptoms indicative of mercury poisoning among women who used beauty creams containing mercury [125,129]. High mercury levels associated with skin cream use were also reported in the case of a pregnant woman, with high risks for the developing fetus [130]. These cases demonstrate that dermal uptake from prolonged application of cosmetics can present significant health risks.

U.S. EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency) offers tools for conducting exposure assessments and risk characterization that are suitable for various scenarios [131]. The SHEDS (Stochastic Human Exposure and Dose Simulation) models serve as probabilistic tools for estimating human exposure to chemicals encountered during routine activities. These models offer predictions of aggregate and cumulative exposures over specified time periods. SHEDS-HT (SHEDS-High throughput) provides a comprehensive platform for screening exposures associated with a wide range of products, including cosmetics [132].

Furthermore, there are commercially available models to estimate the exposure to various chemical compounds (including cosmetic ingredients). The Creme Global company has created one that uses Monte Carlo simulations [133].

The determination of toxicokinetic parameters for cosmetic products is essential for a correct evaluation of the health hazard. Dermal absorption is a crucial factor in assessing the safety of cosmetics. Dermal exposure is the primary route for cosmetics and personal care products, except for lipsticks and dental products [134]. Currently, validated non-animal alternatives are available to characterize this process. The OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) has established in vitro protocols for studying the capacity of chemicals to penetrate the skin barrier. Skin Absorption: In Vitro Method (OECD TG 428) evaluates dermal absorption using a diffusion cell with two compartments separated by a skin sample (from human or animal sources), with the tested substance applied to the skin sample. The system comprises a diffusion cell with two chambers, designated as the donor and receptor, separated by a skin sample excised from a mammalian species, either human or animal. The chemical under investigation is applied to the surface of the skin following assessment of the stratum corneum’s integrity, which serves as the primary diffusion barrier. This diffusion chamber enables the determination of the chemical’s absorption profile over time and the quantification of the substance associated with the skin and deposited within distinct layers [135]. Metals such as chromium and nickel are electrophilic, which accounts for their protein reactivity and their tendency to form depots in the stratum corneum [136]. Assessing the capacity to accumulate in the skin is essential for sensitizing metals, nickel, cobalt, and chromium, which can activate local immune responses [137,138].

In silico Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship (QSAR) models (e.g., ten Berge and Potts and Guy) can be used to estimate dermal absorption [134]. IH SkinPerm allows absorption evaluation after three exposure scenarios simulated (instantaneous deposition, deposition occurring over time due to repeated or continuous emission, and skin absorption consequent to airborne vapors. These scenarios were designed for occupational skin exposure assessment, but can also be adapted to cosmetic products [139].

Well-designed studies are needed to assess and understand how various factors influence the dermal absorption of heavy metals from cosmetics. The physicochemical properties of substances, such as ionization capacity, molecular mass, and lipophilicity, significantly influence the ability of metallic compounds to penetrate the skin. For example, Hostýnek [125] evaluated the diffusion of two nickel compounds, nickel chloride and nickel dioctanoate, and determined that the markedly lower diffusion rate of nickel dioctanoate was attributable to its higher molecular mass, which outweighed the influence of molecular polarity [140].

Besides heavy metal concentrations, contact frequency and duration, several other factors can influence absorption, including the composition of the cosmetic product (such as heavy metal levels and surfactants that enhance skin penetration), the characteristics of the application site, and the amount of product applied [107,141,142]. Moreover, if the compounds are water-soluble, their use on moist skin can enhance cutaneous absorption. Furthermore, nanosized particles can also penetrate the skin barrier easily [107,143]. Heavy metals can also enter the body via the transfollicular pathway, bypassing the epidermis [11].

Skin health and anatomical differences across age groups, including the incomplete barrier function in infants and increased transepidermal water loss in older adults, affect metal absorption. The site of cosmetic application is also relevant. Metals from eye cosmetics may be absorbed through the thin epidermis of the eyelids, the conjunctiva, or during tear production [36].

Franken et al. [144] reviewed human skin permeation studies that used the in vitro diffusion cell method and summarized the permeability order (Cu > Pb > Cr > Ni > Co > Hg). They noted that skin permeation and absorption are influenced by several factors. Penetration depends on the oxidation of metals to ionic forms, making the pH of the skin and sweat significant. Bioavailability is also affected by the metal’s valence state. Additionally, diffusion decreases when metals have a high affinity for skin tissues [144].

Midander et al. [137] investigated the kinetics of skin permeation for Co, Ni, and Cr under single and combined metals exposure scenarios, utilizing a diffusion cell and full-thickness piglet skin as the barrier. Measurements were performed continuously using ICP-MS. The findings demonstrated that the presence of multiple metals can modify skin permeation rates. Nickel exhibited faster absorption in the single-exposure scenario. In contrast, the absorption of cobalt and chromium was marginally higher during co-exposure; however, this difference was minimal and did not indicate a significant effect [137].

ZnO is a commonly found compound in cosmetic products (e.g., sunscreen formulations), especially in the form of nanoparticles. Their ability to penetrate the skin barrier and cause systemic toxicity has been studied using in vitro and in vivo approaches [145,146].

The absorption of aluminum compounds, including aluminum chloride, aluminum chlorohydrate, and aluminum zirconium chlorohydrate glycine complexes, commonly found in antiperspirants, is affected by the skin condition. The application of cosmetic products immediately after shaving increases absorption due to irritation, skin abrasions, and removal of the stratum corneum [42]. Pineau et al. [147] employed the Franz™ diffusion cell to assess aluminum percutaneous penetration and demonstrated increased absorption in the stripped skin, which serves as a model for post-shaving conditions [147].

Mixture formulations influence dermal permeation through multiple mechanisms. In cosmetic applications, co-solvents, terpenes, and surfactants frequently enhance the flux of chemicals across the skin relative to aqueous solutions, primarily due to thermodynamic modifications or disruption of the skin’s inherent permeability [148]. Cosmetic formulations significantly affect the skin penetration of metals. Musazzi et al. [142] studied iron oxide nanoparticles in both water suspensions and various semisolid formulations (carbopol gel, hydroxyethyl cellulose gel, carboxymethylcellulose gel, cetomacrogol cream, and cold cream). Using TEM (Transmission Electron Microscopy) imaging, they found that all semisolid formulations, except for the hydroxyethyl cellulose gel, increased the skin penetration of nanoparticles. Cetomacrogol cream formulation showed the highest permeation and the lowest retained amount for iron oxide nanoparticles [142]. Santini et al. [149] also demonstrated that applying iron oxide nanoparticles in a water-in-oil cream formulation accelerated permeation, reducing both penetration and diffusion times [149]. Therefore, creams and semisolid formulations may pose a higher risk in the event of metal contamination.

The assessment of heavy metal exposure can be challenging due to the multiple variables influencing the process, including substance characteristics, skin features (sensitivity, acne, injury), usage patterns (amount of product per use, frequency, body surface area, method of application), and demographic variables (age, gender). Furthermore, some cosmetics are used daily, while others are used only seasonally (e.g., sunscreen products) [150,151].

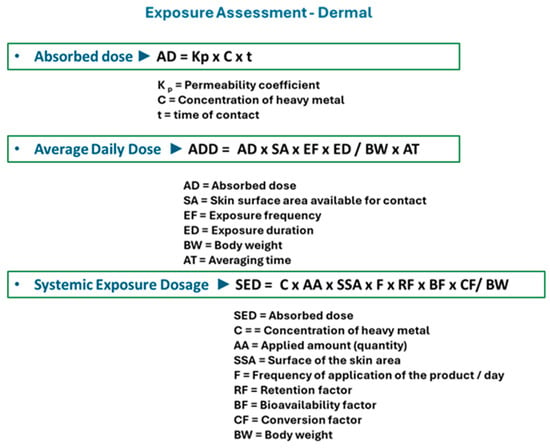

Several equations have been used to assess the exposure risk associated with the application of cosmetics (Figure 2). The values of some of the parameters used in calculation equations are standard and were established by the Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS). The retention factor is a key parameter that estimates the fraction of the product that remains on the skin and can be absorbed after use. The retention factor distinguishes between rinse-off and leave-on products (a retention factor of 0.01 is considered for shampoos and shower gels, and a retention factor of 1 is considered for creams and foundations) [14].

Figure 2.

Equations used to calculate parameters of dermal exposure to heavy metals in cosmetics. (Absorbed dose, Average daily dose, Systemic exposure dosage).

The SCCS does not differentiate between male and female consumers or among various age categories regarding the estimated daily amount of cosmetic product applied, the calculated relative daily exposure values, the surface area for application, and the frequency of application (Table 3) [134]. However, this approach may lack accuracy, as studies have demonstrated significant differences in exposure across various demographic groups [150,152,153,154]. These differences can alter heavy metal systemic exposure calculations and affect risk assessments.

Table 3.

Daily exposure levels for different cosmetics according to the SCCS.

The SED (systemic exposure dosage) parameter calculates systemic exposure to heavy metals in skin care products. Its value is influenced by the metal concentration in the tested sample, body weight, and other standard parameters, whose values are established by the SCCS, namely the quantity of product applied on the skin, the application frequency, and the body surface area (Table 3). The NOAEL (No-observed-adverse-effect level) parameter can be calculated for each heavy metal, reflecting the exposure level with no toxic effects associated. This value is directly influenced by the dermal reference doses (RfDs) established for each metal. The Hazard quotient (HQ) for each metal investigated, and the Hazard index (HI—the sum of individual HQ values) are used to evaluate health risks determined by heavy metals in cosmetics [14].

Meng et al. [150] quantified heavy metals in various cosmetics (hydrating, whitening, anti-acne) using ICP-MS. They then estimated the dermal absorption dose (DAD) (mg/kg/day) (Figure 3) based on the usage patterns of 570 consumers from different age groups, professions, and regions in China. The average DADs of Cd were the lowest for all skin care products, whereas those of Zn and Al were the highest. The usage patterns varied across the groups, which also influenced DAD results. Colder and drier climates, as well as the economic development of the region, can influence the frequency of applications and the DAD values [150].

Figure 3.

Equations used to calculate parameters of dermal exposure to heavy metals in cosmetics (dermally absorbed dose).

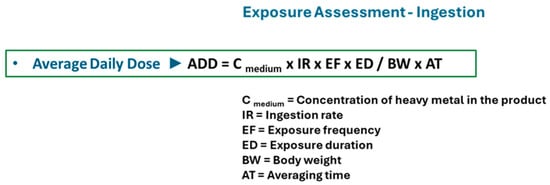

Ingestion can be regarded as the main pathway of exposure to the trace metals in lipsticks and is also a significant route for infants (hand- or object-to-mouth contact). Consequently, there are some differences in calculating systemic exposure. The average daily dose (ADD) of heavy metals is used, and the health risk is computed using ADD values (Figure 4) [109,111].

Figure 4.

Equation used to calculate oral exposure to heavy metals in cosmetics.

Estimating human exposure to harmful compounds such as heavy metals in cosmetic products remains challenging due to the numerous variables involved. However, substantial evidence indicates that metals deposited on the skin are capable of permeating the surface and reaching systemic circulation [155,156,157].

7. Health-Risk Assessment

The assessment of carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic health risks follows a structured process. The initial stages include hazard identification and exposure assessment, which are followed by the estimation of health risks [158].

The assessment of human health risk is a complex process designed to estimate the likelihood of adverse effects following exposure to a specific chemical entity. Risk is determined by the concentration of the substance, the extent of exposure, and its inherent toxicity. The primary objective is to evaluate whether a particular contaminant is present at concentrations that may pose significant risks to human health. Quantitative descriptors such as the no-observed-adverse-effect level (NOAEL), no-observed-effect level (NOEL), and cancer potency factors are used to characterize the hazard potential of a chemical. These metrics are involved in the calculation of guidance values, including the tolerable daily intake (TDI) and acceptable daily intake (ADI) [134].

Different indicators can be used for human health risk analysis (Figure 5). One of them is the Margin of safety (MoS). MoS depends on the NOAEL value of the compound and the predicted amount of substance that enters the body (the systemic exposure dosage—SED). The SED value is determined by multiple factors, including metal concentration, application site area, frequency of application, retention factor, body weight, and bioaccessibility factor. A value over 100 for MoS signifies that the tested chemical is safe [11,12].

Figure 5.

Equations for human risk assessment.

The Hazard Quotient (HQ) is another parameter used to evaluate the potential non-cancer health risks associated with heavy metal exposure. The Hazard Quotient is a typical indicator that compares estimated exposure levels to reference doses considered safe for human health. An HQ below 1 is associated with minimal or no risk for human health. Further investigation is required for values higher than 1, as an HQ over 1 indicates a potential hazard. The Hazard Index (HI) is a metric used for the comprehensive assessment of human health risks resulting from exposure to multiple chemicals. A HI value less than 1 indicates that non-cancer health effects are unlikely. Values greater than 1 suggest the possibility of adverse effects, and the risks increase as the HI values rise [11,74].

The carcinogenic risk (LCR) refers to the probability of developing cancer as a result of exposure to chemicals identified or suspected as carcinogens. LCR can be calculated by multiplying the Systemic Exposure Dosage by a coefficient of the slope of carcinogenicity (e.g., 0.5 mg kg−1 day−1 for Cr and 0.91 mg/kg day−1 for Ni). Values over 10−4 are linked to a significant cancer risk [74].

Table 4 summarizes key findings from the assessment of potential non-carcinogenic health risks linked to various cosmetic products. The referenced studies quantified heavy metal concentrations in these products using the analytical techniques detailed in Table 2 and subsequently calculated the potential health risks based on the equations shown in Figure 5.

Table 4.

Potential non-carcinogenic health risks associated with cosmetic products.

Health risk assessment presents significant challenges due to the numerous factors influencing the effects of chemicals on humans. These complexities hinder the extrapolation of data and limit the accuracy of predictions for the general population. Uncertainty factors arise in evaluating both risk exposure and the quantity of chemical reaching systemic circulation. In the context of cosmetics, the primary exposure route is dermal, although oral exposure may also occur. Chemical form, product formulation, and usage patterns (such as whether products are rinsed off or remain on the skin for extended periods) influence bioavailability. Additionally, intraspecies variability can render certain individuals more susceptible to adverse health effects.

8. New Approach Methods (NAMs) for Cosmetics Safety Assessment

New approach methodologies (NAMs) have been developed for the assessment of cosmetic ingredients and finished products to provide ethical and practical alternatives that maintain biological relevance comparable to animal-based methods [159].

Toxicological analysis of cosmetic products should address multiple aspects, including systemic adverse effects after skin penetration, irritative potential, sensitization risk, reproductive toxicity, genotoxicity, and carcinogenic risk.

Cytotoxicity assessment of heavy metals in cosmetics involves several key endpoints, including cell viability, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and quantification of proteins involved in specific cellular mechanisms. Carcinogenicity and genotoxicity are primary toxicological endpoints of concern for specific heavy metals such as arsenic, cadmium, chromium (VI), and nickel, which are classified as known or probable human carcinogens [160]. Although general cytotoxicity and organ damage are common consequences of heavy metal exposure, these particular metals pose additional cancer risks.

8.1. Cytotoxicity

The mechanisms underlying heavy metal toxicity are multifaceted. Heavy metals disrupt cellular organelles, compromise cell membrane integrity, and alter the activities of enzymes essential for metabolism, detoxification, and damage repair. Metal ions interact with cellular components, including DNA and nuclear proteins, resulting in DNA damage that can induce carcinogenesis or apoptosis [35].

There are several factors that influence the cytotoxicity of metallic compounds, including electronegativity, oxidation state, chemical form, and particle size. For example, inorganic trivalent arsenite exhibits greater toxicity than pentavalent arsenate due to its capacity to interact with protein sulfhydryl groups and inactivate essential enzymatic systems. Chromium (VI) compounds are potent oxidizing agents and readily traverse cell membranes, unlike chromium (III), inducing cytotoxic and genotoxic effects. Organometallic species are typically more toxic due to their increased lipophilicity [35]; however, this is of little importance in the case of cosmetic products, where metals are most likely present as inorganic compounds.

Kar et al. [161] employed periodic table-based descriptors, such as electronegativity and metal cation charge, to develop a quantitative structure-toxicity relationship (QSTR) model for predicting the cytotoxicity of metal oxide nanoparticles using an Escherichia coli bacterial assay Since the induction of intracellular oxidative stress is a central component of heavy metal toxicity mechanisms, both electronegativity and cation charge are important variables influencing cytotoxicity, which is closely associated with the reductive properties of the compound [161]. Electron detachment from metal oxides can initiate the formation of ROS and subsequent oxidative stress. The cytotoxicity of ZnO and CuO was higher compared to Fe2O3 and Al2O3 [162].

Although two-dimensional cell culture systems have limited capacity to replicate in vivo conditions and accurately model skin properties and functions, in vitro assays using human skin cell lines offer practical approaches for assessing the cytotoxicity of cosmetic ingredients. Cell viability is commonly measured with colorimetric assays, such as the MTT or NRU assays. Microscopic analysis facilitates the examination of cellular morphological changes following exposure to xenobiotics, with observed alterations linked to cytotoxic effects. Excessive production of reactive oxygen species and depletion of glutathione are common mechanisms underlying the cytotoxicity of heavy metals. These processes lead to oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, membrane damage, and DNA fragmentation. Genotoxic potential is typically evaluated using the Micronucleus and Comet assays [163,164]. Toxicogenomics provides an additional approach for investigating toxicity by enabling the analysis of gene expression changes in response to heavy metal exposure [164,165].

Table 5 presents selected studies conducted using two-dimensional skin cell culture systems to evaluate the cytotoxic potential of heavy metals.

Table 5.

Selection of studies that assess heavy metals cytotoxicity on skin cell lines.

Although these simple-design experiments provide valuable insights into heavy metal toxicity mechanisms, they present notable limitations. Beyond their restricted capacity to replicate in vivo conditions, there is considerable uncertainty about whether the exposure concentrations used are relevant to real-world scenarios.

8.2. Genotoxicity and Carcinogenicity

The safety of cosmetics is a mandatory requirement for all products available on the market. A special concern is directed towards potential long-term effects, as self-care products are often used over a significant portion of the human lifespan. In this context, the assessment of genotoxicity and carcinogenicity is a critical aspect ensuring human safety, as it helps to identify and mitigate risks associated with the prolonged use of cosmetic products [134].

Due to the fact that animal testing for cosmetic products is completely banned in Europe and in other countries around the world, alternative methods for evaluating the carcinogenic risk are needed [184]. The Scientific Committee for Consumer Safety recommends the use of in silico analysis for the toxicological evaluation of products in the cosmetic industry [134].

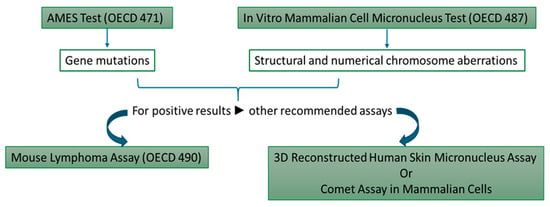

For genotoxicity investigation, the SCCS recommends two tests extracted from the battery of in vitro protocols elaborated by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (Figure 6) [134,184].

Figure 6.

In vitro genotoxicity assessment tools recommended for cosmetic ingredients.

The Ames test (the Bacterial Reverse Mutation Test) was developed at the beginning of the 20th century and, since then, has been widely used to investigate the mutagenic potential [185]. In 1981, Gocke et al. [186] used this assay to evaluate 31 cosmetic ingredients that were approved at the time. Fifteen compounds exhibited positive results in the Ames test; for some of them, genotoxicity was also confirmed by other assays [186].

The development of highly specific mutagenicity/genotoxicity assays is vital for cosmetic ingredients and products, because, in the absence of animal testing, there are limited possibilities to verify and confirm false negative and positive results [187].

However, there is substantial evidence that heavy metal accumulation can cause genotoxic effects [163,188,189]. Therefore, cosmetic products containing significant levels of heavy metals can be linked to genotoxicity and mutagenicity risks.

The impact of UV light on the mutagenic potential of metallic compounds found in sunscreen products, such as zinc oxide (ZnO), has been examined. Studies utilizing human keratinocyte NCTC2544 cells (ICLC HL97002, National Institute for Cancer Research, Italy) assessed the phototoxic and pseudophotoclastogenic properties of these compounds. At elevated concentrations, ZnO demonstrated weak photogenotoxicity and induced micronuclei formation in both irradiated and non-irradiated cells [190]. Additionally, Demir et al. [191] reported an antagonist effect on genotoxicity when ZnO nanoparticles were combined with UV light exposure [191].

Predictive toxicology is now popular in risk assessment. Predictive toxicology methods use data from past studies on similar compounds. Machine learning helps identify relationships between chemical structures and their corresponding activities. QSAR models quickly identify structural alerts, which are chemical features linked to toxic potential. They predict the toxicity risks of cosmetic ingredients [184]. The Monte Carlo simulation is a probabilistic risk-assessment method with reliable results. The probabilistic analysis returns a range of outcomes, an interval for the estimated health risk, and not a single value, like the deterministic analysis [111,192]. QSAR analyses are part of the risk assessment toolbox and are very useful in screening a large number of chemical compounds and grouping them into risk categories [4].

The International Agency for Research on Cancer classifies As, Cr, Ni, and Cd as carcinogenic metals [160]. As non-biodegradable substances, they rapidly accumulate within the body, disrupting vital cellular functions and mechanisms. This accumulation increases the risk of cancer-related diseases by inducing oxidative stress, DNA damage, and cell death [121].

Li et al. [111] investigated the carcinogenic risk of heavy metals present in lip cosmetics found on the Chinese market using the two approaches—the probabilistic and deterministic methods. Differences appeared—the deterministic analysis established that the carcinogenic risks associated with heavy metal traces in lip products were within the acceptable range established by USEPA, while the probabilistic analysis suggests that approximately 10% of integrated risks are above the acceptable range for LCR, which is from 1 × 10−6 to 1 × 10−4 [111].

Currently, carcinogenic risk assessments for cosmetic products are primarily conducted using mathematical models to calculate parameters, such as Carcinogenic health-risk assessment and Overall carcinogenic risk assessment. Table 6 summarizes studies that used analytical methods to measure heavy metal concentrations, as shown in Table 2, and calculated carcinogenic and overall carcinogenic risks using the equations in Figure 5.

Table 6.

Estimation of carcinogenic risk associated with heavy metals in cosmetic products.

8.3. Irritation, Corrosivity, and Skin Sensitization

The use of topical products can affect the integrity of the skin tissues, causing irritation or even corrosion if the exposure concentration is high. The eyes are extremely sensitive and vulnerable to irritants; the application of cosmetic products near the ocular area can have a negative impact [193].

One heavy metal known to display irritant potential is mercury. The WHO states that inorganic mercury salts are corrosive chemicals [194], which can cause skin irritation and contact dermatitis [195]. These compounds were identified in skin-lightening products [55,196,197].

To investigate the irritation potential and corrosivity of chemicals, in vitro toxicity assessment on reconstructed human tissue models is usually preferred. EpiSkinTM (EpiSkin Research Institute, Lyon, France) represents a 3D model of reconstructed epidermis, obtained by culturing human keratinocytes, with multiple layers (basal, spinous, and granular layers), displaying a histology and cytoarchitecture that mimics in vivo skin structure. Corrosive substances penetrate the stratum corneum and decrease the cells’ viability in the underlying layers [198]. Cell viability is evaluated using the MTT method, and the quantity of formazan produced by enzymatic reduction is typically determined photometrically by measuring the optical density. This determination can be affected in the case of colored tested chemicals; however, one alternative to overcome this limitation is to measure formazan levels using HPLC/UPLC systems. EpiSkinTM was used to assess the irritation potential and corrosivity of some cosmetic ingredients, including zinc oxide and copper (II) sulfate. Copper (II) sulfate was included in the UN Globally Harmonized System Category 2, while zinc oxide was not classified [199].

EpiDermTM (MatTech Co., Ashland, MA, USA) is another alternative 3D skin model commercially available, which Kim et al. [200] used to investigate the corrosion and irritation potential of metallic nanoparticles (e.g., aluminum, iron, titanium). The tested nanoparticles reduced cell viability to some extent but were classified as non-corrosive and non-irritant after skin contact [200].

Skin sensitization is another significant risk associated with the use of cosmetic products. Nickel is recognized as one of the most prevalent allergens in cosmetic products. Concentrations exceeding 5 ppm are associated with the development of contact dermatitis. Another metal that may act as a hapten and contribute to the development of contact dermatitis is chromium (Cr III and Cr VI) [119].

In chemico assays represent an additional category of alternative methods for predicting skin sensitization. The Amino Acid Derivative Reactivity Assay (ADRA) and Direct Peptide Reactivity Assay (DPRA) evaluate the capacity of xenobiotics to bind to synthetic peptides, thereby simulating the initial event in the skin sensitization cascade: the attachment of haptens to self-proteins [201,202,203]. These assays are not suitable for metal compounds, which interact with proteins through mechanisms other than covalent bonding [204]. However, the SH test, an alternative method that also assesses the ability of chemicals to bind to proteins by measuring the reduction in free thiol groups on cell surface proteins, was successfully applied by Imai et al. [205] to evaluate metal compounds, such as nickel sulfate [205].

Various reconstructed human epidermis (RHE) models are available to assess skin sensitization hazards. The SensCeeTox assay uses EpiDermTM (MatTech Co., Ashland, MA, USA) to measure gene expression and protein reactivity in keratinocytes. Sens-IS also evaluates gene expression to predict skin sensitizing potential, while the RHE-IL18 assay assesses cell viability using the MTT assay and quantifies IL-18 levels in models such as EpiDermTM or EpiCS (CellSystems® Biotechnologie, Troisdorf, Germany) [206]. The RHE-IL-18 assay proved to be inadequate for evaluating the sensitizing potential of heavy metals [207], profiling, and 3D reconstructed human epidermis to assess skin sensitization by analyzing the changes in gene expression. Sensitizers upregulate genes involved in cytokine and chemokine activity, growth factor activity, metalloendopeptidase activity, and several other markers of inflammation and oxidative stress [208,209]. Potassium Dichromate was assessed using this method and included in category 1A [209].

Keratinocyte activation in the presence of skin sensitizers can be assessed using two in vitro ARE-Nrf2 luciferase test methods (as described in OECD TG 442D). The activation of the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway by sensitizing chemicals in keratinocytes that express a luciferase reporter gene is determined by measuring luminescence intensity [210]. The ARE-Nrf2 Luciferase KeratinoSensTM assay (Givaudan Suisse SA, Vernier, Switzerland) was used to evaluate metal oxide nanoparticles (copper, cobalt, nickel, titanium, cerium, iron, and zinc) and demonstrated potential as a reliable assessment method [211,212].

Activation of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) is a key event in the skin sensitization pathway, resulting in the secretion of proinflammatory molecules and the upregulation of markers such as CD54 and CD86 [201]. Dendritic cell activation can be measured using various methods. OECD TG 442E describes the following: Human Cell Line Activation test (h-CLAT), U937 cell line activation Test (U-SENS™), Interleukin-8 Reporter Gene Assay (IL-8 Luc assay), and Genomic Allergen Rapid Detection (GARD™) [213]. Hölken et al. [214] integrated immature dendritic cells into a full-thickness 3D human skin model, thereby establishing an immune competent model that serves as a potential alternative to human ex vivo skin explants. This model was used to identify sensitizers, including NiSO4 [214].

The Genomic Allergen Rapid Detection (GARD™skin) assay was used to evaluate the sensitization potential of metal compounds. Results demonstrated 92% accuracy and 100% sensitivity in predicting skin sensitizing hazards [215].

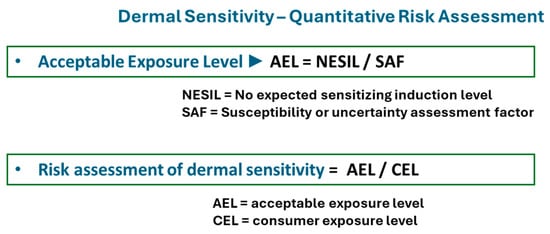

QRA (Quantitative Risk Assessment) models can also be used to estimate dermal sensitization, as shown in the equations in Figure 7. This method was applied to several sensitizing heavy metals (Ni, Co, Cu, and Hg). In all cases, the values of the ratios were above 1. When the AEL exceeds the CEL, the exposure is considered safe for consumers [112].

Figure 7.

Equations for dermal sensitivity risk assessment.

Assessment of ocular irritative and corrosive potential represents another critical phase in the development of cosmetic products. Following the prohibition of animal testing for cosmetics, ocular corrosives and irritants are now identified using non-animal methods, including the Bovine Corneal Opacity and Permeability (BCOP) test (OECD TG 437) [216] and the Reconstructed Human Cornea-like Epithelium test (OECD TG 492) [217]. Kolle et al. [218] utilized the EpiOcularTM tissue model (MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA 01721, USA) and BCOP eye irritation testing to evaluate metal nanoparticles, including TiO2 and ZnO. Their findings indicate that this combination of in vitro assays provides a valid alternative to in vivo testing [218].

Over the past decade, advancements in in vitro testing for skin and ocular irritation and sensitization assessment have enabled the development of comprehensive strategies to identify irritant and sensitizing compounds.

9. Conclusions

The cosmetics market comprises a diverse array of products. Consumer safety is a critical concern, given the frequent and prolonged use of many cosmetic items. Adverse effects associated with cosmetic use have been documented since ancient times. The evaluation of heavy metals in cosmetic products has become a prominent research focus. Numerous quantification techniques have been developed to provide rapid and accurate results using environmentally sustainable protocols. Although regulatory laws in various countries limit metal content, recent studies have detected traces of toxic metals, some exceeding permissible levels, in numerous cosmetic products. These findings underscore the need for continuous monitoring programs to address heavy metal adulteration in cosmetics. Prolonged use of cosmetics may lead to chronic toxicity due to sustained exposure to low concentrations of heavy metals, particularly when products are applied to large surface areas or regions with thin epithelial linings.

The prohibition of animal testing in 2009 accelerated the advancement of alternative in vitro toxicity assessment methods. A range of assays are now available, enabling researchers to examine multiple dimensions of health risks related to heavy metals in cosmetics. In the safety assessment of cosmetic products, hazard identification can be effectively accomplished using the current array of alternative non-animal tests. However, risk characterization remains challenging in the absence of in vivo testing. Consequently, future research should prioritize the improvement, refinement, and validation of exposure assessment models and non-animal approaches to determine systemic toxicity following repeated exposure. Furthermore, an important consideration for regulatory authorities during health risk assessment is that demographic parameters influence cosmetics usage patterns, which can impact the accuracy of estimated exposure doses, hazard quotients, and hazard indices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J. and A.T.; methodology, I.M.; investigation, I.M. and A.J.; writing—original draft preparation, A.J. and I.-C.C.; writing—review and editing, A.T. and L.A.; visualization, I.-C.C.; supervision, L.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 5-Br-PAPS | 2-(5-bromo-2-pyridylazo)-5-[N-npropyl-N-(3-sulfopropyl)amino]phenol |

| 8-OHdG | 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine |

| AAS | Atomic absorption spectrometry |

| AD | Absorbed dose |

| ADD | Average Daily Dose |

| ADRA | Amino Acid Derivative Reactivity Assay |

| AEL | Acceptable Exposure Level |

| AP-1 | Activator Protein 1 |

| APC | Activation of antigen-presenting cell |

| ARE | Antioxidant Response Element |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CCD | Charge-Coupled Device |

| CCK-8 | Cell Counting Kit-8 |

| CD | Dendritic Cells Maturation Marker |

| CDI | Chronic Daily Intake of Carcinogens |

| CEL | Consumer Exposure Level |

| CHOP | C/EBP Homologous Protein |

| CR | Carcinogenic risk |

| CV-AAS | Cold-vapor atomization atomic absorption spectroscopy |

| DCFH-DA | Dichlorofluorescin diacetate |

| DL | Detection limit |

| DPRA | Direct Peptide Reactivity Assay |

| DμPAD | Distance-based paper microfluidic device |

| EC50 | Half-maximal Effective Concentration |

| ET AAS | Electrothermal Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy |

| F AAS | Flame atomic absorption spectroscopy |

| FASL | Fas ligand |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FDCA | Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act |

| FOSL1 | FOS-like 1 |

| FRET | Fluorescence resonance energy transfer |

| GF AAS | Graphite furnace atomic absorption spectroscopy |

| GHK-Cu | Glycyl-L-histidyl-L-lysine copper complex |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| HI | Hazard index |

| HQ | Hazard quotient |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| HR CS GF AAS | High-Resolution Continuum Source Graphite Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectrometry |

| HSP27 | Heat shock protein 27 |

| HSPA1A | Gene that encodes Heat shock 70 kDa protein 1 |

| ICP-MS | Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry |

| ICP-OES | Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy |

| IL | Interleukin |

| ISO | The International Organization for Standardization |

| Keap1 | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 |

| LCR | Lifetime Cancer Risk |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| LIBS | Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| LOQ | Limit of quantification |

| mBBr | Monobromobimane |

| MDL | Minimum detectable limit |

| MMP | Metalloproteinase |

| MoCRA | Modernization of Cosmetics Regulation Act |

| MoS | Margin of Safety |

| MT | Metallothionein |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| NAM | New Approach Methodologies |

| NESIL | No Expected Sensitization Induction Level |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NOAEL | No-observed-adverse-effect level |

| NP | Nanoparticle |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear Factor, erythroid 2-related factor |

| NRU | Neutral Red Uptake |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| QRA | Quantitative Risk Assessment |

| QSAR | Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship |

| RfD | Dermal Reference Dose |

| RHE | Reconstructed Human Epidermis |

| RNPC | Rhodamine-Naphthalimide Conjugate |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SCCS | Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety |

| SED | Systemic Exposure Dosage |

| SHEDS | Stochastic Human Exposure and Dose Simulation |

| SHEDS-HT | SHEDS-High throughput |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| TDI | Tolerable daily intake |

| TNF | Tumor Necrosis Factor |

| UPLC | Ultra-performance liquid chromatography |

| USEPA | U.S. Environmental Protection Agency |

| WST | Water-Soluble Tetrazolium salt |

| XRF | X-ray fluorescence |

References

- Zahra, M.; Riaz, L.; Kalsoom, S.; Saleem, A.R.; Taneez, M. Assessment and computational bioevaluation of heavy metals from selected cosmetic products. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swafford, S. Cosmetics. In An Overview of FDA Regulated Products; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 257–279. [Google Scholar]

- Piccinini, P.; Piecha, M.; Torrent, S.F. European survey on the content of lead in lip products. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2013, 76, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauwels, M.; Rogiers, V. Human health safety evaluation of cosmetics in the EU: A legally imposed challenge to science. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2010, 243, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, T.; Taneez, M.; Kalsoom, S.; Irfan, T.; Shafique, M.A. Experimental calculations of metals content in skin-whitening creams and theoretical investigation for their biological effect against tyrosinase enzyme. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2021, 199, 3562–3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Makova, M.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Rhodes, C.J.; Valko, M. Essential metals in health and disease. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2022, 367, 110173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerdoun, M.A.; Zergui, A.; Adjaine, O.E.-k.; Mekhloufi, S. Determination of Lead (Pb) in Kohl cosmetics sold in the south of Algeria. J. Trace Elem. Miner. 2024, 9, 100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhussaini, H.M.A.; Hossain, M.A.; Arputhanantham, S.S. Determination of toxic heavy metal content in a whitening creams by using inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry. Arab. J. Geosci. 2022, 15, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.N.; Ashraf, U.-e.-K.; Anjum, M.N.; Kiran, S.; Abrar, S.; Farid, M.F. Identification and quantification of selected heavy metals by ICP-OES in skin whitening creams marketed in Pakistan. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massadeh, A.; El-Khateeb, M.; Ibrahim, S. Evaluation of Cd, Cr, Cu, Ni, and Pb in selected cosmetic products from Jordanian, Sudanese, and Syrian markets. Public Health 2017, 149, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kicińska, A.; Kowalczyk, M. Health risks from heavy metals in cosmetic products available in the online consumer market. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, H.; Mehmood, M.Z.; Shah, M.H.; Abbasi, A.M. Evaluation of heavy metals in cosmetic products and their health risk assessment. Saudi Pharm. J. 2020, 28, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abendrot, M.; Kalinowska-Lis, U. Zinc-containing compounds for personal care applications. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2018, 40, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Shafeeq, A.; Siddiq, U.; Bashir, F.; Ahmad, T.; Athar, M.; Butt, M.T.; Ullah, S.; Mukhtar, A.; Hussien, M. A mechanistic approach for toxicity and risk assessment of heavy metals, hydroquinone and microorganisms in cosmetic creams. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 433, 128806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, Z.; Ziarati, P.; Shariatdoost, A. Determination and safety assessment of lead and cadmium in eye shadows purchased in local market in Tehran. J. Environ. Anal. Toxicol. 2013, 3, 1000193. [Google Scholar]

- Abrar, A.; Nosheen, S.; Perveen, F.; Abbas, M. Evaluation of metals and organic contents in locally available eye shadow products in Lahore, Pakistan. Pak. J. Sci. Ind. Res. Ser. A 2018, 61, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyamfi, O.; Aboko, J.; Ankapong, E.; Marfo, J.T.; Awuah-Boateng, N.Y.; Sarpong, K.; Dartey, E. A systematic review of heavy metals contamination in cosmetics. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 2024, 43, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, M.S.; Moosa, A.A.; Alzuhairi, M.A. Heavy metals in cosmetics and tattoos: A review of historical background, health impact, and regulatory limits. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2024, 13, 100390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filella, M.; Martignier, A.; Turner, A. Kohl containing lead (and other toxic elements) is widely available in Europe. Environ. Res. 2020, 187, 109658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ashban, R.; Aslam, M.; Shah, A. Kohl (surma): A toxic traditional eye cosmetic study in Saudi Arabia. Public Health 2004, 118, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokashi, A.; Fellows, K.M.; Chin, R.J.; Whittaker, S.G.; Simpson, C.D.; Ceballos, D.M. Lead in traditional eyeliners: An investigation into use and sources of exposure in King County, Washington. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2025, 5, e0004643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, J.; Stoff, B. Surma eye cosmetic in Afghanistan: A potential source of lead toxicity in children. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2018, 177, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruyneel, M.; De Caluwé, J.; Des Grottes, J.; Collart, F. Use of kohl and severe lead poisoning in Brussels. Rev. Med. Brux. 2002, 23, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hepp, N.M. Determination of total lead in 400 lipsticks on the US market using a validated microwave-assisted digestion, inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometric method. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2012, 63, 159–176. [Google Scholar]

- Lead in Cosmetic Lip Products and Externally Applied Cosmetics: Recommended Maximum Level Guidance for Industry. US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. 2016. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/draft-guidance-industry-lead-cosmetic-lip-products-and-externally-applied-cosmetics-recommended (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Hepp, N.M.; Mindak, W.R.; Gasper, J.W.; Thompson, C.B.; Barrows, J.N. Survey of cosmetics for arsenic, cadmium, chromium, cobalt, lead, mercury, and nickel content. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2014, 65, 125. [Google Scholar]

- Hamann, C.R.; Boonchai, W.; Wen, L.; Sakanashi, E.N.; Chu, C.-Y.; Hamann, K.; Hamann, C.P.; Sinniah, K.; Hamann, D. Spectrometric analysis of mercury content in 549 skin-lightening products: Is mercury toxicity a hidden global health hazard? J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 70, 281–287.e283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwegbue, C.M.; Bassey, F.I.; Obi, G.; Tesi, G.O.; Martincigh, B.S. Concentrations and exposure risks of some metals in facial cosmetics in Nigeria. Toxicol. Rep. 2016, 3, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corazza, M.; Baldo, F.; Pagnoni, A.; Miscioscia, R.; Virgili, A. Measurement of nickel, cobalt and chromium in toy make-up by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2009, 89, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhang, W.; He, Y.; Wu, B.; Ji, R. Transcriptomics reveals key regulatory pathways and genes associated with skin diseases induced by face paint usage. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 890, 164374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Su, Y.; Tian, L.; Peng, S.; Ji, R. Heavy metals in face paints: Assessment of the health risks to Chinese opera actors. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 724, 138163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A.K. Assessment of metals in cosmetics commonly used in Saudi Arabia. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balali-Mood, M.; Naseri, K.; Tahergorabi, Z.; Khazdair, M.R.; Sadeghi, M. Toxic mechanisms of five heavy metals: Mercury, lead, chromium, cadmium, and arsenic. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 643972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaishankar, M.; Tseten, T.; Anbalagan, N.; Mathew, B.B.; Beeregowda, K.N. Toxicity, mechanism and health effects of some heavy metals. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2014, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Chakraborty, A.J.; Tareq, A.M.; Emran, T.B.; Nainu, F.; Khusro, A.; Idris, A.M.; Khandaker, M.U.; Osman, H.; Alhumaydhi, F.A. Impact of heavy metals on the environment and human health: Novel therapeutic insights to counter the toxicity. J. King Saud. Univ. Sci. 2022, 34, 101865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowska, S.; Brzóska, M.M. Metals in cosmetics: Implications for human health. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2015, 35, 551–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkow, G. Using copper to improve the well-being of the skin. Curr. Chem. Biol. 2014, 8, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaetke, L.M.; Chow-Johnson, H.S.; Chow, C.K. Copper: Toxicological relevance and mechanisms. Arch. Toxicol. 2014, 88, 1929–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.N.; Fiume, M.; Zhu, J.; Bergfeld, W.F.; Belsito, D.V.; Hill, R.A.; Klaassen, C.D.; Liebler, D.C.; Marks, J.G., Jr.; Shank, R.C. Safety Assessment of Zinc Salts as Used in Cosmetics. Int. J. Toxicol. 2024, 43, 5S–69S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoofs, H.; Schmit, J.; Rink, L. Zinc toxicity: Understanding the limits. Molecules 2024, 29, 3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanajou, S.; Şahin, G.; Baydar, T. Aluminium in cosmetics and personal care products. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2021, 41, 1704–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darbre, P.D. Aluminium and the human breast. Morphologie 2016, 100, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, T.; Mohammed, E.; Bascombe, S. The evaluation of total mercury and arsenic in skin bleaching creams commonly used in Trinidad and Tobago and their potential risk to the people of the Caribbean. J. Public Health Res. 2017, 6, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naujokas, M.F.; Anderson, B.; Ahsan, H.; Aposhian, H.V.; Graziano, J.H.; Thompson, C.; Suk, W.A. The broad scope of health effects from chronic arsenic exposure: Update on a worldwide public health problem. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013, 121, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.-Y.; Yu, S.-D.; Hong, Y.-S. Environmental source of arsenic exposure. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2014, 47, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucovic, D.; Kulas, J.; Mirkov, I.; Popovic, D.; Zolotarevski, L.; Despotovic, M.; Kataranovski, M.; Aleksandrov, A.P. Oral cadmium intake enhances contact allergen-induced skin reaction in rats. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2022, 35, 1038–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Raza-Naqvi, S.A.; Idrees, F.; Sherazi, T.A.; Anjum-Shahzad, S.; Ul-Hassan, S.; Ashraf, N. Toxicology of heavy metals used in cosmetics. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2022, 67, 5615–5622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, S.; Malik, S.; Batool, F.; Rehman, K.; Akash, M.S.H. Metabolomics of heavy metal exposure. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2025, 128, 109–154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Toh, P.Z.; Tan, J.Y.; Zin, M.T.; Lee, C.-Y.; Li, B.; Leolukman, M.; Bao, H.; Kang, L. Selected biomarkers revealed potential skin toxicity caused by certain copper compounds. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansdown, A. Iron: A cosmetic constituent but an essential nutrient for healthy skin. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2001, 23, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L.; Oliveira, M.M.; Pessôa, M.T.C.; Barbosa, L.A. Iron overload: Effects on cellular biochemistry. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 504, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Fang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, K.; Jiang, L.; Yang, B.; Yang, Y.; Song, Y.; Liu, C. Trace metal lead exposure in typical lip cosmetics from electronic commercial platform: Investigation, health risk assessment and blood lead level analysis. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 766984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almukainzi, M.; Alotaibi, L.; Abdulwahab, A.; Albukhary, N.; El Mahdy, A.M. Quality and safety investigation of commonly used topical cosmetic preparations. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, G.; Gupta, D.; Tiwari, A. Toxicity of lead: A review with recent updates. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2012, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, H.H.; Sakakibara, M.; Sera, K.; Nurgahayu; Andayanie, E. Mercury exposure and health problems of the students using skin-lightening cosmetic products in Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Cosmetics 2020, 7, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]