Featured Application

In this study, a traveling nutrient analyzer was designed for real-time, in situ monitoring of nutrients in seawater from moving vessels or fixed observation stations. It is a reliable tool for oceanographic surveys, marine environmental protection, and ecological research, enabling high-frequency data acquisition that is essential for understanding dynamic marine biogeochemical processes.

Abstract

Continuous monitoring of seawater nutrients is crucial for marine resource research and conservation, yet it faces challenges due to the constraints of offshore working conditions. We developed a multi-analyte sensor based on flow analysis technology, which integrates wet-chemical colorimetry/fluorometry for the simultaneous in situ determination of nitrite, nitrate, ammonium, silicate, and phosphate in seawater. To mitigate bubble interference, an integrated gas-trapping cavity was designed, and a data-cleaning algorithm based on the interquartile range method was implemented. In June 2025, a sea trial was conducted at two stations in the northern South China Sea, the results of which showed high consistency with laboratory standard methods: the maximum absolute relative errors were 1.79% for nitrite, 5.01% for nitrate, 1.42% for ammonium, 5.93% for phosphate, and 2.95% for silicate. The performance under real marine conditions is demonstrated by relative errors below 6% and linear correlation coefficients exceeding 0.999 for all parameters. This research demonstrates a practical approach for in situ marine observation.

1. Introduction

Nutrients serve as key regulators of marine primary productivity and play a central role in marine biogeochemical cycles [1,2]. Although various inorganic ions in seawater possess certain nutritional functions, in the context of chemical oceanography, the term “nutrients” typically refers specifically to the inorganic forms of nitrogen, phosphorus, and silicon, primarily including nitrate (NO3−), nitrite (NO2−), ammonium (NH4+, i.e., ammonia nitrogen), phosphate (PO43−), and silicate (SiO32−). The concentration distribution and chemical speciation of nutrients directly affect the growth rates and community structure of phytoplankton [3,4,5], thereby regulating energy flow and material cycling within the entire marine ecosystem. Consequently, continuous monitoring of nutrients with high spatiotemporal resolution holds significant scientific value for assessing water eutrophication status [6,7,8], deciphering mechanisms of biogeochemical element cycling [9], and understanding ecosystem response processes [10].

Traditional nutrient analysis primarily relies on the collection, preservation, and laboratory-based measurement of discrete water samples [11]. This method is not only time-consuming and labor-intensive but is also susceptible to biological or chemical reactions during sample storage and transportation, often resulting in measurements that fail to accurately reflect the in situ status and dynamic processes [12,13,14,15,16]. To overcome these limitations, various rapid nutrient detection technologies have been developed. For instance, sensors based on ultraviolet spectroscopy [17,18], such as the ISUS (In Situ Ultraviolet Spectrophotometer), enable rapid, reagent-free nitrate measurement [19], but lack sensitivity and selectivity for detecting other nutrient parameters [17]. Although ion-selective electrode (ISE) methods can be used for continuous monitoring of ammonium and nitrate [20], they suffer from severe interference from high-concentration background ions in the complex seawater matrix, alongside issues such as signal drift and poor long-term stability, making them inadequate for long-term monitoring requirements [21]. Wet-chemical analysis coupled with flow analysis technology has emerged as a mainstream approach for marine nutrient detection due to its high sensitivity, high selectivity, and capability for multi-parameter integration [22,23,24]. In previous studies, several analyzers based on this technology have been developed [25], such as nitrate and nitrite analyzers employing vanadium chloride reduction and the Griess method [26], multi-parameter nutrient analyzers based on phosphomolybdenum blue and silicomolybdenum blue methods [22]. For instance, Fang et al. developed a custom-built autonomous analyzer and demonstrated the real-time, underway mapping of five nutrients in a dynamic estuary, addressing the challenge of high-frequency monitoring [27]. However, existing systems still commonly face challenges including insufficient capability for synchronous multi-parameter detection, weak resistance to environmental interference, and difficulties in adaptation to underway observation.

To address the above issues, this study aims to develop an underway multi-parameter nutrient analyzer based on wet-chemical–flow analysis technology for the synchronous and continuous detection of five key seawater nutrients: nitrite, nitrate, ammonium, phosphate, and silicate. The system integrates the Griess method, ortho-phthaldialdehyde (OPA) fluorescence method, and molybdenum blue method, achieving quantitative analysis by establishing linear calibration models between absorbance/fluorescence intensity and concentration. To mitigate interference from bubbles generated during reactions, an integrated gas-trapping device was designed within the flow path to physically reduce bubble formation. This was combined with an interquartile range (IQR) statistical method for outlier removal and data cleaning of the acquired optical signals, significantly enhancing measurement reliability and accuracy. This paper will elaborate on the design principles, system composition, and performance verification of the instrument, and evaluate its application effectiveness in real marine environments through laboratory and sea trials.

2. Methods

2.1. Instrument Measurement Principle

The measurement of nitrite, nitrate, reactive phosphate, and reactive silicate in seawater was conducted using spectrophotometry [28,29,30], while ammonium was measured by fluorometry [31]. The specific analytical methods and corresponding detection wavelengths are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Analytical methods and wavelength parameters for various nutrients.

2.2. Flow Path Configuration

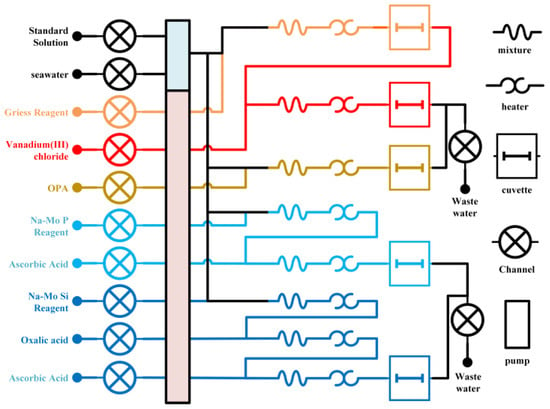

The instrument operates based on the principle of wet-chemical chromogenic reactions, integrating flow analysis technology and spectrophotometry to achieve automated determination of nutrient concentrations in seawater. A high-precision peristaltic pump (DG-12-B, Longer Precision Pump Co., Ltd., Baoding, China) introduces the seawater sample and corresponding chemical reagents into the flow path at predetermined ratios. After thorough mixing and completion of the chromogenic reaction, the resulting product is directed into a flow cell for photometric detection, as illustrated in Figure 1. During detection, light from the source passes through the reacted liquid and is partially absorbed and the transmitted light intensity is converted into an electrical signal by a silicon photodiode integrated within the flow cell. This signal is subsequently transmitted to a host computer system, where it undergoes data processing and calibration algorithms to output the concentration values of the target nutrients.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram of the overall flow path.

This design fully automates the entire process—from sample introduction and reaction control to signal acquisition and data processing—ensuring accurate and stable measurement, as well as suitability for long-term monitoring in marine environments.

2.3. Instrument Workflow

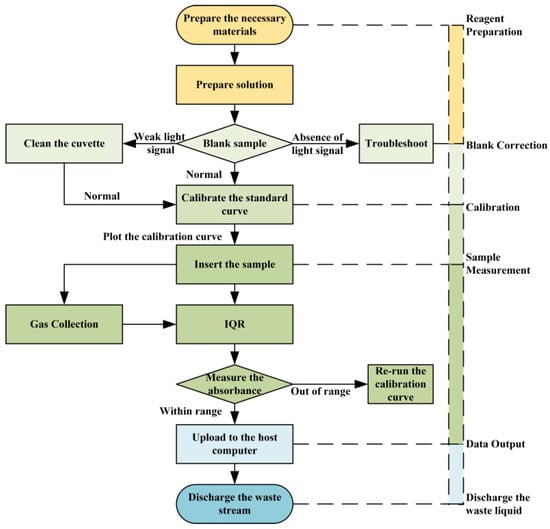

The analytical process begins with system startup and a pre-programmed warm-up period to ensure thermal and optical stability. Subsequently, an automatic cleaning cycle is initiated using an acid wash solution (e.g., 10% HCl) and ultrapure water to eliminate potential carryover contamination from previous analyses. Following system preparation, the instrument executes a calibration procedure by sequentially introducing a series of standard solutions with known concentrations to establish the calibration curve for each nutrient.

For sample measurement, the high-precision peristaltic pump quantitatively aspirates the seawater sample and the specific chromogenic reagents. The sample and reagents are then merged within the mixing module, where they undergo controlled heating to accelerate the chromogenic reaction, forming light-absorbing or fluorescent compounds. The reacted mixture is subsequently transported through a debubbler unit to remove interference from micro-bubbles before entering the flow cell for spectrophotometric or fluorometric detection.

The acquired optical signal is converted into a digital output by a data acquisition module and transmitted in real time to the embedded processing unit or host computer. The concentration of each target nutrient is calculated based on the pre-established calibration model. All data, including raw signals, calculated concentrations, and system status parameters, are automatically logged and can be either stored locally or transmitted remotely via wired or wireless communication interfaces, as illustrated in Figure 2. This integrated workflow ensures fully automated, continuous operation with minimal human intervention, suitable for long-term, in situ nutrient monitoring.

Figure 2.

Workflow.

3. Instrument Configuration and Optimization

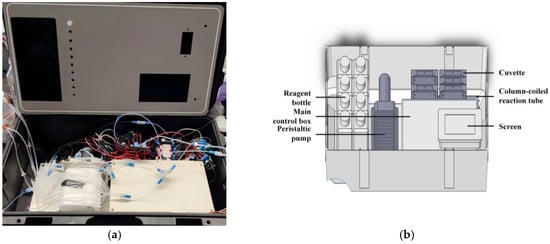

The traveling nutrient analyzer comprises three main functional units: the reagent unit, the chemical reaction and detection unit, and the control and signal processing unit. These units are rationally arranged in space and integrated within a polypropylene trolley case with external dimensions of 56 cm × 35 cm × 24 cm, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Internal schematic diagram: (a) Internal view of the analyzer with the outer panel removed to show the component layout and flow path configuration; (b) design drawing.

The internal control and signal processing unit is housed in a sealed, waterproof aluminum alloy enclosure. All external interfaces have waterproof connectors to prevent short circuits caused by water leakage or splashing during instrument operation. This structural design balances portability and functionality, facilitating deployment on field platforms such as research vessels and ocean observation stations for on-site, real-time detection of seawater nutrient parameters. It is also suitable for conventional laboratory analysis, offering operational flexibility and user convenience.

The analyzer is divided into inner and outer sections by a central partitioned groove plate. Reagents, samples, and waste are transferred between these sections via bulkhead fittings mounted through this partition plate. The reagent unit is placed in the dedicated recessed area on the outer side of the partition plate, while the other units are located internally. During normal operation, only periodic replacement of the reagent bottles is required.

3.1. Reagent Unit

The reagent unit functions as the system’s reagent storage and supply module. It consists of multiple independently detachable reagent bottles and their supporting structure. Prepared reagents are injected into the dedicated bottles via a syringe. These bottles are suspended on a rack within the reagent chamber and are connected to the respective reagent inlets of the main system via polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) tubing. This design allows the entire reagent chamber to be detached as a whole, facilitating convenient reagent replacement and maintenance either onshore or aboard a vessel.

3.2. Chemical Reaction and Detection Unit

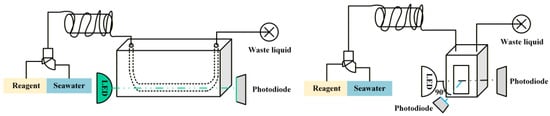

The chemical reaction and detection unit is the core component of the traveling nutrient analyzer. It primarily consists of a high-precision micro peristaltic pump, light sources, flow cells, lenses, optical filters, and photodetectors. The system employs five independent light source driver circuits and five independent photodetector circuits operating simultaneously to achieve multi-channel concurrent nutrient measurement. Light signals of stable wavelength and power, emitted by five LEDs, irradiate their respective flow cells and the transmitted output light signals are then relayed to the signal processing unit. All modules utilize quick-connect fittings for easy maintenance and replacement. A schematic diagram of the structure and principles of the chemical reaction and detection unit are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Photodetection schematic diagram: on the left is the spectrophotometer, and on the right is the fluorescence photometer.

For ammonium detection, a 20 mm optical path fluorescent flow cell is utilized to measure fluorescence intensity, while nitrite, nitrate, phosphate, and silicate are measured via absorbance using a 50 mm optical path U-shaped spectrophotometric flow cell. The U-shaped design allows liquid to enter the detection chamber from the bottom upward, thereby effectively preventing bubbles from interfering with the detection process. To ensure sufficient reaction between the seawater sample and reagents, a heating and mixing device is installed prior to the flow cell. This device consists of a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) tube coiled around a constant-temperature heating rod, ensuring consistent and stable reaction conditions.

The complete measurement cycle for all five nutrients takes only 20 min. The reagent consumption for each measurement is approximately 2–3 mL, and a single stored reagent volume is sufficient for 100 measurements.

The analyzer has a standby power consumption of 8 W, and its operational power does not exceed 80 W. The specified operational power of 80 W represents a transient peak during the initial heating phase. The average power consumption over a full measurement cycle is considerably lower, making the system suitable for battery-powered deployment. The light sources employ LEDs, which offer a fast response, stable light intensity, and low power consumption. The detection wavelengths for each nutrient are listed in Table 1. Light emitted by the LEDs is filtered through optical filters, and the transmitted light intensity is detected by silicon photodiodes, enabling high-precision optical detection.

3.3. Control and Signal Processing Unit

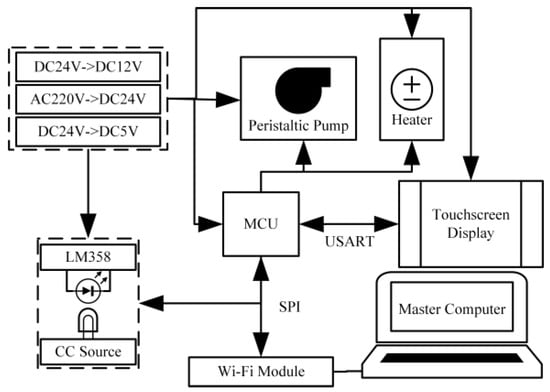

The control system is built around an STM32 microcontroller. As shown in Figure 5, it primarily consists of a data acquisition circuit and a constant-current driver circuit, and is powered by a 220 V AC power supply. An internal power management module converts the 220 V AC to 24 V DC, which is then further stepped down by voltage regulator chips to various other levels required by different circuits.

Figure 5.

Control system schematic diagram.

The core of the microcontroller minimal system is an STM32F407 series MCU (STM32F407, STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland), which operates at a maximum frequency of 168 MHz. This microcontroller is responsible for communicating with the host computer and TF card to enable data transmission and local storage, and controlling the operation of the LED light sources, multi-channel peristaltic pump, and heater to execute the predefined analytical sequence. A schematic diagram of the overall system design is presented in Figure 5.

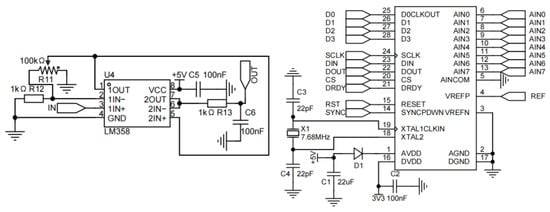

In the data acquisition circuit, the output voltage signal from the detector in the photoelectric detection module is conditioned by an LM358 operational amplifier. The conditioned analog signal is then converted into a digital signal by an ADS1256 chip and subsequently transmitted to the microcontroller unit, as illustrated in Figure 6. The constant-current drive circuit is designed to supply a stable current to the LEDs serving as light sources, ensuring consistent luminous intensity and long-term stability.

Figure 6.

Signal amplification and conversion circuit.

In terms of signal processing, the system employs a concentration–absorbance response model established using standard solutions. Combined with the interquartile range method, it eliminates outlier data caused by bubble interference, thereby enhancing measurement accuracy and anti-interference capability. The entire analyzer adopts an embedded system architecture with programmable sampling functions, enabling full automation of the entire process—including sample injection, reaction, detection, and data processing—while supporting local storage of measurement data. Data can be output via a serial port or retrieved through Wi-Fi, facilitating subsequent analysis and archiving.

The control and signal processing unit is housed within an internal control box. A serial touch screen (DaCai DC10600KM070_1111_0C, Guangzhou Dacai Optoelectronic Technology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China) displaying the real-time measurement status is externally connected to the control box. This 7.0-inch display features a resolution of 1024 × 600, is powered by a 400 MHz SOC processor, supports Lua script programming and global multi-language switching, and is characterized by low power consumption and high reliability. During operation, the screen receives measurement data in real time and can send commands to the MCU to control pump speed and heating status.

3.4. Optimization of Reaction Reagents

To ensure stable and accurate detection results from the traveling nutrient analyzer in complex marine environments, this study optimized the detection reagents for each parameter. The optimization efforts focused on key objectives: improving reaction sensitivity and selectivity, enhancing reagent stability, and increasing resistance to interference from the seawater matrix.

The detection of nitrite and nitrate is based on the Griess reaction, with vanadium chloride selected as the reducing agent for nitrate instead of a cadmium column. This alternative performs comparably to the traditional cadmium column method while significantly simplifying maintenance. For ammonium detection, the ortho-phthaldialdehyde (OPA) fluorometry method was employed, achieving a detection sensitivity far superior to that of the indophenol blue method.

For phosphate and silicate, the molybdenum blue method was optimized mainly by enhancing anti-interference capability and stability. Phosphate detection utilizes a catalytic system comprising sodium molybdate and potassium antimony tartrate in a sulfuric acid medium, while silicate detection employs a weakly acidic sodium molybdate solution with the addition of oxalic acid to eliminate phosphate interference. To improve the stability of the molybdenum blue colloid in both assays, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) was added to the shared ascorbic acid reductant.

Reagents and the sample were introduced through a 12-channel peristaltic pump, with all 12 channels operating at the same speed (10 rpm). Reagents were transported through tubing with an internal diameter of 0.5 mm, while the sample was transported via tubing with a 3 mm internal diameter. The mixture subsequently passed through a mixing unit and a heating bath before entering the flow cell for photometric measurement. Using a one-variable-at-a-time experimental design, the influence of reagent compositions on the assay was investigated and optimized using standard solutions at the highest end of the target concentration range, as shown in Figure 7. This strategy was adopted to verify that the reagent concentrations were sufficient to drive the chemical reactions to completion across the entire working range, thereby ensuring robustness and accuracy at higher analyte loads.

Figure 7.

All influencing factors: (a) The effects of NEDD and vanadium chloride; (b–d) Indicating the influence of the concentrations of different components in the mixture on the results; (e) The influence of sulfuric acid dosage on the detection results of silicate; (f) The influence of sulfuric acid dosage on the detection results of phosphate salts.

For the determination of nitrite and nitrate, the commonly used formulation of sulfanilamide and N-(1-naphthyl)ethylenediamine dihydrochloride (NEDD) at a mass–volume ratio of 10:1 was adopted without modification. The optimization efforts primarily focused on the vanadium chloride concentration. For the OPA mixed reagent, the optimal concentration was determined by comparatively testing each individual chemical component.

The efficiency of phosphate and silicate detection is predominantly influenced by the H+ concentration. In an acidic medium, phosphate and silicate in the sample react with molybdate to form heteropoly acid complexes, which are subsequently reduced by ascorbic acid to produce an intensely blue-colored complex. Since the sodium molybdate, ascorbic acid, and oxalic acid are generally used in excess, the process was optimized primarily through targeting the concentration of sulfuric acid in the solution.

All reagents were prepared according to the formulations listed in Table 2. Milli-Q ultrapure water and chemical reagents of appropriate purity grades (primarily analytical grade) were used. The purity of all reagents was confirmed to be suitable for their intended use in this study, ensuring the stability of the reaction system and accurate detection results. The manufacturers of the reagents are indicated in the Appendix A. The reagent formulations for the detection of each nutrient are as follows:

Table 2.

Optimized reagent formulations for nutrient detection.

3.5. Handling of Interference Factors in the Instrument

3.5.1. Impact of Bubbles During Solution Heating and Countermeasures

When using flow analysis for colorimetric analysis, the presence of bubbles constitutes a non-negligible source of interference. Bubbles can significantly alter the light path and absorbance measurements, leading to data inaccuracies and potential result misinterpretation. Although degassing pre-treatment can eliminate bubbles from the reagents, bubble formation during the internal heating process remains inevitable.

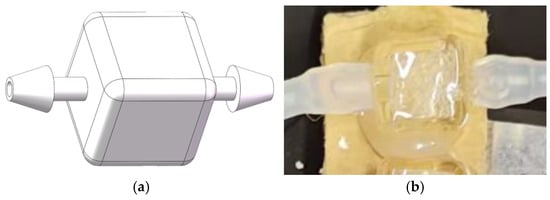

To address this issue, a gas-trapping cavity was incorporated at the inlet of the flow cell. This cavity is not designed to prevent all bubbles from entering the flow cell, but rather to collect and coalesce small bubbles generated during heating into larger ones. When the air pressure inside the cavity reaches a certain threshold, the large bubble generated displaces the liquid forward into the flow cell and is subsequently expelled rapidly by the incoming liquid flow. This process also helps to remove any small bubbles that may be present inside the flow cell, providing a certain cleaning effect, as illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

A schematic diagram of the gas collection cavity function: (a) Flow Path with Small Bubbles: The reacted liquid stream, containing small bubbles generated during the heating process, enters the cavity; (b) Bubble Coalescence: Small bubbles are captured and coalesce into a larger bubble within the expanded volume of the cavity; (c) Bubble Expulsion: Once the accumulated bubble reaches a critical size, it is propelled forward by the liquid pressure, displacing the liquid in the flow cell; (d) Flow Restoration: The large bubble is swiftly flushed out through the outlet, clearing the optical path and restoring stable flow for detection. This mechanism provides a physical cleaning effect for the flow cell.

This integrated gas capture chamber is a key component for reducing bubble interference. It is made from a solid glass block through precise processing, with a shape of a simple cube with an internal volume of 1.5 milliliters, as shown in Figure 9. Its design features a simple horizontal flow path, with the liquid inlet and outlet located at the exact center of the two faces on the left and right sides of the cube. The internal structure is a simple cube without any additional features, forming clear corners that facilitate the collision and merging of micro-bubbles during the liquid flow process. The size of the cube was optimized through experiments to provide sufficient residence time for bubble merging at the operating flow rate, while ensuring that the merged bubbles can be promptly discharged.

Figure 9.

The design and implementation of the integrated gas-trapping cavity: (a) A schematic model of the cubic glass cavity, showing the horizontal flow path between the inlet (left) and outlet (right). The cubic internal volume measures 1.5 mL. (b) Photograph of the fabricated cavity integrated into the flow system.

3.5.2. Impact of Bubbles on Silicon Photodiode Detection and the Corresponding Data Processing Method

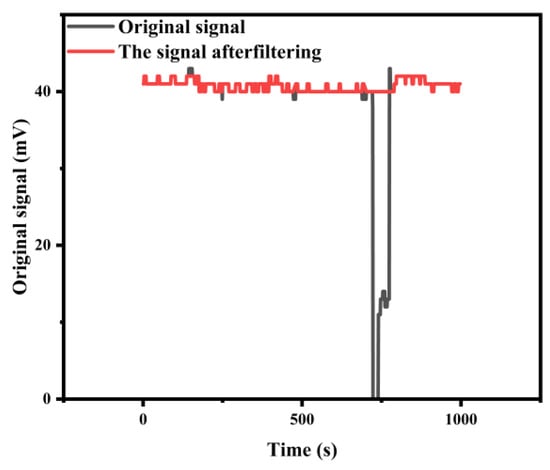

The interference caused by bubbles in light transmission within the flow cell is highly significant, often resulting in abnormally low light intensity values detected by the silicon photodiode. However, owing to the function of the aforementioned gas-trapping cavity, such anomalous values occur only transiently. From the perspective of continuous measurement, these outliers are short-lived and can therefore be effectively identified and removed using the IQR method [32]. The IQR is a robust statistical technique used to measure data dispersion and identify outliers.

The acquired data series were processed using the Interquartile Range (IQR) method, a non-parametric technique selected for its robustness in identifying outliers within non-normally distributed data, such as the transient, negative spikes caused by bubbles. The processing was implemented on a rolling data window as follows: the series was sorted to determine the first quartile (Q1) and the third quartile (Q3). The IQR was calculated as IQR = Q3 − Q1. The outlier detection bounds were then set to Q1 − A × IQR and Q3 + A × IQR. Any datum falling outside these bounds was classified as an outlier and removed. The resulting gaps in the time-series data were subsequently filled using linear interpolation to maintain temporal continuity.

The scaling factor A critically determines the stringency of outlier detection. Although a value of 1.5 is conventional for identifying “mild outliers” in general datasets, we optimized this parameter based on the specific characteristics of our optical signal. The primary interference from bubbles manifests exclusively as large, negative-going spikes, while the valid signal from a stable standard or sample is highly consistent, resembling a steady baseline. This asymmetry meant that the conventional symmetric bounds were unnecessarily lenient for our application. Consequently, we focused the optimization on the lower bound (Q1 − A × IQR).

We systematically evaluated the performance of different A values (ranging from 0.5 to 2.0) using high-frequency absorbance data from stable standard solutions. The evaluation criterion was the ability to correctly identify visually confirmed bubble events while preserving the integrity of the valid signal. A value that was too large (e.g., A = 2.0) failed to capture subtle bubble artifacts, whereas a value that was too small (e.g., A = 0.5) began to incorrectly flag natural signal noise as outliers. Through this analysis, we determined that a value of A = 1.0 provided the optimal balance for our system. This more sensitive threshold reliably captured over 99% of the transient bubble-induced outliers without over-filtering, thereby maximizing data quality and the reliability of subsequent concentration calculations. While Figure 10 demonstrates the successful application of this algorithm to a nitrite standard, the method’s efficacy was validated across all five analytes, where it consistently ensured high data fidelity by eliminating transient bubble interference.

Figure 10.

Comparison before and after processing.

Figure 10 demonstrates the application of this method for a 1000 s absorbance dataset acquired for a nitrite standard solution. An extremely low outlier, lasting approximately 30 s and caused by the pumping of a bubble, is observed around the 700 s mark. This artifact was successfully identified and removed by the IQR-based processing.

4. Discussion

4.1. Instrument Performance Testing

4.1.1. Linear Range and Detection Limit

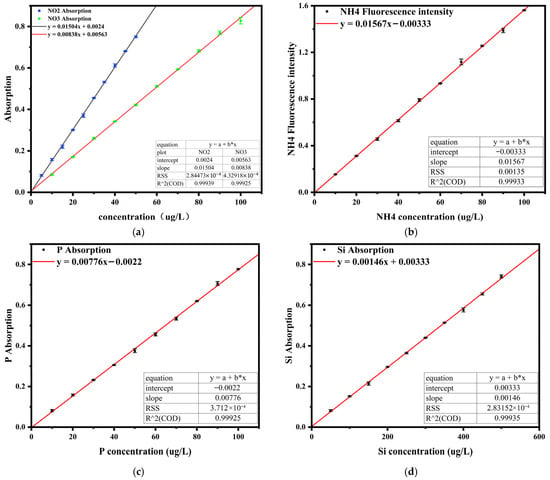

Standard calibration solutions for nitrite, nitrate, ammonium, phosphate, and silicate were prepared separately according to the practical measurement requirements. Standard curves were established by plotting the concentration of each nutrient as the abscissa and the corresponding absorbance or fluorescence intensity as the ordinate. Excellent linear relationships were obtained, as shown in Figure 11. The correlation coefficients (R2) of all standard curves reached or exceeded 0.999, meeting the minimum requirement stipulated in the “The specification for marine monitoring Part 2: Data processing and quality control of analysis” (GB 17378.2-2007) [33].

Figure 11.

Standard curves for five nutrient salts: (a) Standard curve graph of nitrate and nitrite; (b) Standard curve of ammonium salts; (c) Standard curve of phosphate; (d) Standard curve of silicate.

For the determination of the limit of detection (LOD), deionized water was used as the blank sample and 11 replicate measurements were performed. The obtained signal values were converted into equivalent concentration values, and their standard deviation (SD) was calculated. The instrumental detection limit for each parameter was then determined using the formula LOD = 3 × SD. The specific LOD values for each nutrient are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Experimental parameters.

4.1.2. Accuracy and Precision

To evaluate the instrument’s measurement performance for the five nutrients, two actual samples with known concentrations were selected for each nutrient. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate, and the average of the three measurement results was used as the final value.

Accuracy was assessed using the relative error (δ) as the metric, calculated using the following formula:

where Δ is the difference between the measured value and the true value, and L is the true value.

δ = (Δ/L) × 100%

Precision was evaluated by calculating the relative standard deviation (RSD) of the triplicate measurements for each group. The relevant experimental results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

The measurement results and errors obtained using this equipment in the laboratory with standard solutions.

The experimental results indicate that the relative errors (δ) for nitrite, nitrate, and silicate were all within ±4%, while those for phosphate and ammonium remained within ±6%. In terms of precision, the relative standard deviations (RSDs) for nitrite, nitrate, phosphate, and silicate were all below 3%, and the RSD for ammonium was within 4%. The demonstrated precision (RSDs ≤ 3.19%) not only meets the requirements for shipboard analysis but also exceeds the performance (e.g., 7.4–8.9% RSD for key nutrients) reported in recent studies on automated systems [22], underscoring the analytical robustness of our method.

To further contextualize the performance of our analyzer, a comparative analysis with other recently reported sensing technologies is presented in Table 5. This comparison reveals several distinct advantages of our system. Firstly, it achieves markedly lower detection limits (LODs) for most parameters compared to other wet-chemical analyzers [22,26,28]. For instance, our LODs for nitrite (2.34 μg/L), nitrate (4.65 μg/L), and phosphate (3.46 μg/L) are substantially lower, enhancing the instrument’s capability for detecting trace-level nutrients. Secondly, while the ultraviolet spectroscopy method [17] offers a rapid response, it is limited to nitrate detection and exhibits a much higher LOD, rendering it unsuitable for the multi-parameter, low-concentration monitoring required in most marine studies. Crucially, our analyzer is the only one in this comparison that integrates the simultaneous determination of all five key nutrient parameters within a single, compact platform and a relatively short analysis time (20 min).

Table 5.

A comparative analysis of the developed analyzer with other reported sensing systems for the determination of nutrients in seawater.

These results collectively demonstrate that the analyzer provides satisfactory accuracy, precision, and sensitivity for the simultaneous determination of the five major nutrients in seawater, positioning it as a highly competitive tool for high-frequency, in situ monitoring.

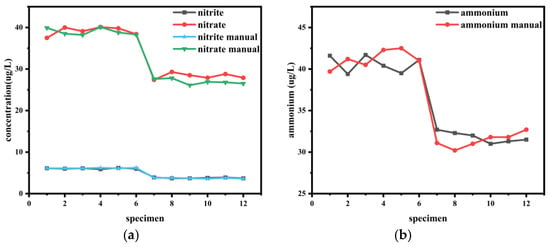

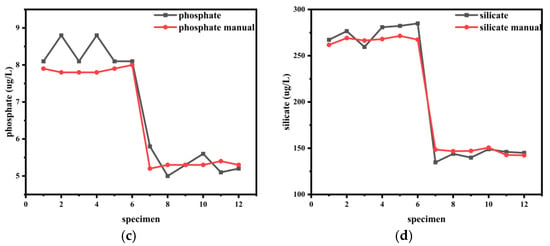

4.2. Comparison Between Manual Laboratory Analysis and Instrumental Measurements

A sea trial was conducted in the northern South China Sea in June 2025, during which seawater samples were collected using a shipboard CTD system. The samples were immediately filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane filter on-site, and subsequently analyzed in situ by the analyzer. Concurrently, a subset of the water samples was preserved immediately after collection, frozen at −20 °C, and transported to the laboratory for subsequent comparative analysis against the on-site instrumental measurements.

Seawater samples were collected from two stations located approximately 200 km apart to represent distinct hydrological environments. Compared to Station 1, which was situated in the coastal, high-nutrient waters, Station 2 was located further offshore in the low-nutrient waters. Samples were taken at a depth of 10 m for this comparative study. Six replications were performed for each station: samples 1–6 correspond to Station 1, and samples 7–12 correspond to Station 2. “manual” indicates the measurement results obtained after the sample was transported back to the laboratory at −20 °C and then thawed for measurement, as illustrated in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

A comparison of nutrient concentrations obtained by the on-board analyzer and standard laboratory methods (“manual”). The “Manual” reference measurements were conducted in the laboratory using established protocols after sample preservation and transport. The x-axis “Sample Number” represents the sequence of individual seawater samples collected from two stations (Samples 1–6: Station 1; Samples 7–12: Station 2). Each sample was analyzed once by each method. The subplots show the results for (a) nitrite and nitrate, (b) ammonium, (c) phosphate, and (d) silicate.

The performance of the field-based instrument was validated against standard laboratory analyses, with the close agreement in results confirming its accuracy and reliability, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Comparison between on-board measurements and laboratory measurements at two stations.

The significant differences in nutrient concentrations between Station 1 and Station 2, as summarized in Table 6, are consistent with their distinct geographical locations and hydrological settings. Station 1, being closer to the coast, is subject to greater influence from terrestrial runoff and potential anthropogenic discharges, which explains the consistently higher concentrations of all investigated analytes. In contrast, Station 2 is located approximately 200 km offshore in the open waters of the northern South China Sea. Here, the dilution by nutrient-poor oceanic waters, combined with consumption by phytoplankton, leads to markedly lower nutrient levels.

The field measurements for most nutrient parameters demonstrated good agreement with the laboratory analyses, with the relative deviation for the vast majority of comparisons falling within 10%. This meets the fundamental accuracy requirements for marine survey data. It is noteworthy that larger relative deviations were observed for specific parameters, such as phosphate at Station 1. The concentration at this station was close to the method’s limit of quantification, where the relative uncertainty is inherently higher. Despite this, the sensor response was significantly above the blank signal, confirming the reliability of the detection, albeit with a higher quantitative uncertainty. Other minor deviations across the dataset may be attributed to a combination of factors, including the ship’s motion during the sea trial.

This successful comparison verified the stability and reliability of the instrument’s operation in an authentic and complex marine environment. It demonstrates that the instrument is capable of broader application in routine oceanographic surveys.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a traveling nutrient analyzer based on wet-chemical methodology and flow analysis technology was developed for the in situ, continuous, and automated detection of nitrite, nitrate, ammonium, phosphate, and silicate in seawater. Through an optimized flow path design, integrated gas-trapping cavities, and a quartile-based algorithm for outlier rejection, the instrument effectively suppressed bubble interference, enhancing data stability and measurement precision. Laboratory evaluations confirmed wide linear dynamic ranges and low detection limits of 2.34 μg/L (NO2−), 4.65 μg/L (NO3−), 2.94 μg/L (NH4+), 3.46 μg/L (PO43−), and 9.40 μg/L (SiO32−), with all linear correlation coefficients greater than 0.999. Accuracy and precision tests showed relative standard deviations below 4%, indicating high stability and repeatability.

The analyzer is well-suited for application in coastal waters, estuaries, and eutrophic environments, as validated during sea trials in the northern South China Sea. The comparative results between the on-board analyzer and standard laboratory methods for seawater samples from two stations demonstrated satisfactory measurement capabilities under field conditions, with a maximum relative error of 5.93% for phosphate.

The current 20 min measurement cycle, primarily governed by reaction kinetics, presents a limitation for capturing very rapid biogeochemical transients. Future work will focus on overcoming this by transitioning to a miniaturized microfluidic chip architecture to reduce reagent consumption and analysis time. For enhanced sensitivity in oligotrophic waters, the integration of liquid waveguide capillary cells (LWCC) will be pursued. These improvements aim to expand the instrument’s applicability to open-ocean research and enhance its capability for high-frequency dynamic monitoring.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W. and H.W.; methodology, J.W. and H.W.; software, J.W.; validation, J.W., Y.W. and J.Z.; formal analysis, J.W.; investigation, S.W.; resources, H.W.; data curation, J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W.; writing—review and editing, H.W. and S.W.; visualization, J.W.; supervision, H.W.; project administration, Y.W.; funding acquisition, H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant numbers: 2021YFC2801705 and 2022YFC2803801) and the Key R&D Program of Shandong Province, China (grant number: 2024CXGC010916).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

To facilitate reference, the manufacturers and catalog numbers of the reagents and equipment used in this study are summarized in Table A1.

Table A1.

Details of the materials used.

Table A1.

Details of the materials used.

| Designation in Text | Item Number | Producer |

|---|---|---|

| Sulfanilamide | S108473 | Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China |

| HCl | H399657 | Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China |

| NEDD | N105071 | Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China |

| Vanadium Chloride | V498277 | Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China |

| Sodium Tetraborate | S112463 | Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China |

| Sodium Sulfite | S112300 | Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China |

| o-Phthaldialdehyde | P108633 | Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China |

| Ethanol | E329897 | Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China |

| Sodium Molybdate | S104867 | Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China |

| Potassium Antimony Tartrate | P191240 | Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China |

| Sulfuric Acid | S399848 | Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China |

| Ascorbic Acid | A103533 | Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate | S108347 | Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China |

| Oxalic Acid | O107180 | Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China |

References

- Tivig, M.; Keller, D.P.; Oschlies, A. Riverine nutrient impact on global ocean nitrogen cycle feedbacks and marine primary production in an Earth system model. Biogeosciences 2024, 21, 4469–4493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, D.A.; Tagliabue, A. Feedbacks between phytoplankton and nutrient cycles in a warming ocean. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoel, P.; Bianchi, D.; Cavanaugh, K.C.; Freider, C.A.; Kessouri, F. Influence of anthropogenic nutrient sources on kelp canopies during a marine heat wave. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 216, 117788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.I.; Franzè, G.; Kling, J.D.; Wilburn, P.; Kremer, C.T.; Deuer, S.M.; Litchman, E.; Hutchins, D.A.; Rynearson, T.A. The interactive effects of temperature and nutrients on a spring phytoplankton community. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2022, 67, 634–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, M.; Liu, K.; Chen, B.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Z.; Xu, Z.; Tan, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, H. Nutrient availability influences the thermal response of marine diatoms. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2024, 69, 2318–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thig, T.R.; Tackett, S.M.T.; Voolstra, C.R.; Ross, C.; Chaffron, S.; Durack, P.J.; Warmuth, L.M.; Sweet, M. Human-induced salinity changes impact marine organisms and ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 4731–4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Zou, R.; Zhang, X.; Liang, Z.; Ye, R.; Liu, Y. Exploring the type and strength of nonlinearity in water quality responses to nutrient loading reduction in shallow eutrophic water bodies: Insights from a large number of numerical simulations. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 313, 115000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; White, J.R. On the calculation of carbon and nutrient transport to the oceans. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, D.S.; Perron, M.M.G.; Bond, T.C.; Bowie, A.R.; Buchholz, R.R.; Guieu, C.; Ito, A.; Maenhaut, W.; Myriokefalitakis, S.; Olgun, N.; et al. Earth, Wind, Fire, and Pollution: Aerosol Nutrient Sources and Impacts on Ocean Biogeochemistry. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2022, 14, 303–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandes, J.A.; Devol, A.H.; Deutsch, C. New Developments in the Marine Nitrogen Cycle. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dian, W.; Jinhui, Z.; Haonan, W.; Guixian, L.; Xiurong, H.; Tiantian, G. Effect of different measurement methods on data quality of nutrients in seawater. Xiamen Daxue Xuebao (Ziran Kexue Ban) 2020, 59, 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Xu, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, T.; Wang, C. Detection methods of ammonia nitrogen in water: A review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 127, 115890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhao, W.; Miao, H.; Han, X. Effects and improvements of different reagents preservation methods on the determination of phosphate in seawater by phosphomolybdenum blue spectrophotometric method. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 139, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Hnelt, A.M.R.; Martin, P.R.; Haderlein, S.B. Limitations of the molybdenum blue method for phosphate quantification in the presence of organophosphonates. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2025, 417, 3103–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Song, Y.; Zhou, B.; Xu, H. Nitrite: From Application to Detection and Development. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, W.; Li, H.; Guo, X.; Chen, J.; Shi, X.; Zhu, Y. Field determination of nitrate in seawater using a novel on-line coppered cadmium column: A comparison study with the vanadium reduction method. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1138734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xu, S.; Jin, H.; Wang, J.; Yan, F. Copper Nanoparticles Confined in a Silica Nanochannel Film for the Electrochemical Detection of Nitrate Ions in Water Samples. Molecules 2023, 28, 7515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Yu, K.; Zhu, X.; Su, J.; Wu, C. An Improved Algorithm for Measuring Nitrate Concentrations in Seawater Based on Deep-Ultraviolet Spectrophotometry: A Case Study of the Aoshan Bay Seawater and Western Pacific Seawater. Sensors 2021, 21, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, C.; Johnson, K.; Coletti, L.; Maurer, T.; Massion, G.; Pennington, J.T.; Plant, J.; Jannasch, H.; Chavez, F. Hourly In Situ Nitrate on a Coastal Mooring: A 15-Year Record and Insights into New Production. Oceanography 2017, 30, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.M.; Oliveri, E.; Kautenburger, R.; Hein, C.; Kickelbick, G.; Beck, H.P. In situ real-time monitoring of ammonium, potassium, chloride and nitrate in small and medium-sized rivers using ion-selective-electrodes—A case study of feasibility. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2025, 4, 1238–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.R.; Weeser, B.R.; Rufino, M.C.; Breuer, L. Diurnal Patterns in Solute Concentrations Measured with In Situ UV-Vis Sensors: Natural Fluctuations or Artefacts? Sensors 2020, 20, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altahan, M.F.; Esposito, M.; Achterberg, E.P. Improvement of On-Site Sensor for Simultaneous Determination of Phosphate, Silicic Acid, Nitrate plus Nitrite in Seawater. Sensors 2022, 22, 3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, J.; Xiang, J.; Lin, D.; Fu, L.; Li, B.; Chen, L. Applications of Microfluidic Technology in Marine Analysis and Monitoring. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 2023, 51, 1545–1556. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Huang, T.; Du, C.; Guo, X. Comparison of different continuous in-situ observation systems in seawater. J. Trop. Oceanogr. 2021, 40, 103–113. [Google Scholar]

- van der Molen, J.; Ruardij, P.; Greenwood, N. Potential environmental impact of tidal energy extraction in the Pentland Firth at large spatial scales: Results of a biogeochemical model. Biogeosciences 2016, 13, 2593–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Li, H.; Bo, G.; Lin, K.; Yuan, D.; Ma, J. On-site detection of nitrate plus nitrite in natural water samples using smartphone-based detection. Microchem. J. 2021, 165, 106117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Bo, G.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, J. Real-Time Underway Mapping of Nutrient Concentrations of Surface Seawater Using an Autonomous Flow Analyzer. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 11307–11314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnikin, A.; Hedjazi, M.; Al-Shwaiyat, M.; Skok, A.; Bazel, Y. Consecutive spectrophotometric determination of phosphate and silicate in a sequential injection lab-at-valve flow system. Anal. Chim. Acta 2023, 1273, 341464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hani, O.E.; Karrat, A.; Digua, K.; Amine, A. Development of a simplified spectrophotometric method for nitrite determination in water samples. Spectrochim. Acta A 2022, 267, 120574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Robledo, E.; Corzo, A.; Papaspyrou, S. A fast and direct spectrophotometric method for the sequential determination of nitrate and nitrite at low concentrations in small volumes. Mar. Chem. 2014, 162, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Chen, J.; Shen, Y.; Li, H.; Zhu, Y. Evolution of the fluorometric method for the measurement of ammonium/ammonia in natural waters: A review. TrAC-Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 171, 117519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyushin, B.B. On Applicability of IQR Method for Filtering of Experimental Data. J. Eng. Thermophys. 2024, 33, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAC. The Specification for Marine Monitoring Part 2: Data Processing and Quality Control of Analysis. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China. 2007. Available online: https://openstd.samr.gov.cn/bzgk/gb/newGbInfo?hcno=2A832569DF947259C8793864F584618F (accessed on 12 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).