Abstract

As a result of welding processes in boron-alloyed martensitic armor steels, unfavorable microstructural changes occur, leading to a significant reduction in the mechanical properties of both the weld metal and the base material. The dendritic structure of the weld metal and the partial tempering in the heat-affected zone contribute to the decreased durability of structural components, thereby deteriorating their performance. This issue is particularly important since such steels are widely used not only in the defense industry but also in the mining, construction, transportation, and metallurgical sectors, where they operate under conditions of intensive abrasive wear. For this reason, the authors attempted to improve the mechanical properties of welded joints of boron-alloyed martensitic armor steel (with a nominal hardness of 500 HBW) through post-weld heat treatment. The welded joint was evaluated based on metallographic examinations using light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy, as well as abrasive wear tests carried out on a T-07 tribotester. The conducted investigations demonstrated that, under loose abrasive conditions (using electrofused alumina), heat treatment increased the wear resistance of the joints by 55% compared to the as-welded condition. The obtained results were compared with selected grades of Hardox steel commonly used in industrial applications.

1. Introduction

Armor steels represent a key group of engineering materials primarily applied in defense and ballistic protection, as well as in areas where high mechanical strength must be combined with increased resistance to abrasive wear. Their predominantly martensitic microstructure provides high strength while maintaining acceptable ductility. These properties make armor steels attractive not only for military purposes but also for civilian applications, including components of machinery operating under severe abrasive conditions.

One of the key technological challenges associated with the use of armor steels is the ability to produce their welded joints. Although welding enables the fabrication of complex structures, it is accompanied by localized thermal effects that lead to the formation of a heat-affected zone (HAZ) and a weld metal region, both exhibiting properties distinct from those of the base material. In the case of high-strength martensitic steels, to which armored steels belong, this issue becomes particularly critical. Welding of high-strength martensitic steels invariably results in a reduction in mechanical properties, both within the weld metal and across the extensive HAZ strength properties. For instance, the tensile strength (Rm) of Armox 440T steel is approximately 1250 MPa, while for Armox 500T it reaches about 1400 MPa. Even higher mechanical parameters are reported for Armox 600T, where Rm exceeds 2000 MPa. According to data provided by manufacturers of welding consumables, the maximum achievable strength of commercially available filler metals does not exceed 1000 MPa. This leads to the conclusion that welding martensitic steels—even those with the lowest strength levels—inevitably results in a reduction in tensile strength in the weld metal by nearly 30% compared to the base material. Moreover, as the strength grade of the joined material increases, this difference becomes progressively more pronounced.

Previous research has focused on developing methods to mitigate the adverse effects of welding high-strength martensitic steels. These approaches include optimizing technological parameters, selecting appropriate filler materials, and applying post-weld heat treatment (PWHT). Particular attention has been given to restoring a favorable microstructure within the weld metal and reducing residual stresses, which can significantly enhance the durability of components operating under dynamic loading and abrasive wear conditions. For example, welding trials on Hardox 400 and Hardox 500 steels have shown that a properly selected filler material and welding parameters can yield welded joints with tensile strengths (Rm) of 615 MPa and 663 MPa, respectively—representing approximately 50% and 43% of the base material strength [1]. In the case of Hardox 450 steel, TIG (Tungsten Inert Gas) welding using Filler Rod E 7018 wire and a powder additive enriched with tungsten and cobalt resulted in a maximum tensile strength of 775 MPa [2], whereas submerged arc welding (using flux OK Autrod 13.43 + OK Flux 10.62) produced joints with an Rm value of 677 MPa [3]. Considering the tensile strength of the base material (Rm = 1434 MPa) [4], the mechanical property reduction in the welded region exceeds 50%. Similar observations were reported by Zuo et al. [5], where the tensile strength of Hardox 500 welded joints did not exceed 900 MPa, as well as by Teker et al. and Gupta et al. in studies [6,7]. The detrimental impact of microstructural alterations on mechanical properties can be effectively minimized only through laser welding technologies [8,9] or PWHT. The latter enables achieving tensile strengths of 1810 MPa for Hardox 600 and 1831 MPa for Hardox Extreme, corresponding to approximately 85% of the nominal base material strength [10,11]. Comparable conclusions were also drawn by other researchers [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20], who consistently emphasized the necessity of implementing PWHT to restore desirable mechanical performance.

The pronounced reduction in mechanical properties within specific regions of a welded joint—resulting from adverse phase transformations induced by overheating and the consequent tempering of the base material, as well as the dendritic structure of the weld metal—also leads to a deterioration in the functional performance of these materials, including their resistance to abrasive wear. According to available literature data, within martensitic microstructures operating under dry (loose) abrasive conditions, hardness exerts the dominant influence on wear behavior [21]. However, this relationship must be interpreted with caution when selecting materials for structural components intended to operate in environments with higher frictional resistance [22,23,24]. Additional requirements imposed on martensitic steels to maintain a high level of resistance to abrasive wear include: (1) a fine-lath martensitic microstructure [25,26], (2) the ability to undergo surface work hardening during operation [27,28,29,30], and (3) a favorable distribution and morphology of secondary phase precipitates [31]. These factors may lead to distinct tribological behaviors even among materials with the same nominal hardness in the as-delivered condition [22,32,33]. Given the loss of key mechanical properties in martensitic steels as a consequence of welding processes, the present study aimed to assess the potential for improving the abrasive wear resistance of welded joints of a selected armor steel grade with a nominal hardness of 500 HBW through the application of PWHT. This steel is classified as weldable and bendable, which significantly broadens its field of application [34]. In terms of performance, it may outperform Hardox Extreme steel, 38GSA steel (used for agricultural plowshares) [35], and carburized 20MnCr5 steel [36]. Beyond their use in defense and protective applications, materials of this type are also employed in cultivator coulters, crusher and feeder lining plates, as well as hammers used in recycling processes [34]. The combination of high abrasive wear resistance and good weldability makes the investigated steel a promising alternative to conventional materials used under conditions of severe abrasive wear.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to evaluate the abrasive wear resistance of welded joints in boron-alloyed martensitic armor steel and to identify possibilities for its improvement through the application of optimized PWHT parameters. The results obtained may provide a significant contribution to the advancement of welding technologies for armor steels, which are widely used in both military and civilian sectors.

2. Materials and Methods

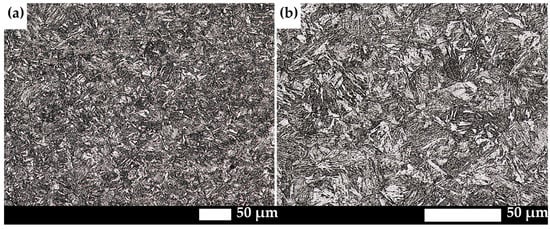

The chemical composition was determined using a Leco GDS500A glow-discharge optical emission spectrometer (LECO Corporation, St. Joseph, MI, USA). The measurements were performed at a discharge voltage of 1250 V and a current of 45 mA, with high-purity argon (99.999%) supplied as the working gas. Each result represents the average of a minimum of five separate analyses to ensure measurement reliability. According to the obtained data (Table 1 and Table 2), the examined armor-grade steel belongs to the group of medium-carbon alloys (C = 0.29%). Its hardenability is mainly influenced by the presence of manganese, chromium, nickel, and molybdenum. Nickel additionally contributes to lowering the ductile-to-brittle transition temperature, while molybdenum counteracts temper embrittlement. The very low levels of phosphorus and sulfur are beneficial, as they help maintain favorable mechanical performance. Aluminum and titanium act as grain refiners, supporting the formation of a fine lath-type microstructure, whereas the small boron addition (approximately 0.008%) markedly improves hardenability. The carbon equivalent value (CEV) of 0.69 and the equivalent carbon content (CET) of 0.47 indicate reduced weldability of the material, increasing the risk of cold cracking and typically implying the need for preheating prior to welding. The microstructure of the analyzed armor steel, shown in Figure 1, consists predominantly of tempered fine-lath martensite with a small fraction of fresh martensite regions.

Table 1.

Chemical composition and carbon equivalent values of the analyzed armor steel. #—plate thickness; CEV—carbon equivalent according to IIW; CET—carbon equivalent according to SS-EN 1011-2 [37].

Table 2.

Chemical composition of the analyzed armor steel. #—plate thickness.

Figure 1.

Microstructure of the investigated armor steel: (a) 200×, (b) 500×. Predominantly tempered fine-lath martensite with a few areas of fresh martensite. Light microscopy, etched with 3% HNO3.

The welded joints were produced using the Metal Active Gas (MAG) process with filler materials intended for high-strength, low-alloy steels. Although several advanced welding technologies could potentially be considered for joining high-strength armor steels, the MAG/MIG process was selected in this study due to its dominant industrial relevance, high process efficiency, availability of consumables, and suitability for producing multi-pass welds in thick plates. These advantages make MAG/MIG welding the most practical and widely applicable technique for both experimental work and real manufacturing conditions. Based on our previous research experience, alternative methods were also tested; however, MAG/MIG and, to a lesser extent, SAW proved to offer the most reliable process stability and compatibility with the subsequent heat treatment route developed in this work. Welding was performed with an ESAB A2 Mini Trac system equipped with an ESAB LAE 800 power source. The steel plates were joined with a double-sided butt weld. The selected welding parameters ensured full penetration and proper fusion of the joint. The process was conducted in the PA (flat) position with a 1.0 mm electrode wire. The arc voltage and current settings for the first and second passes were 15 V/90 A and 28.2 V/170 A, respectively. Direct current with electrode positive polarity (DC+) was used, while the wire feed speed was maintained at 9 m/min. The consumable wire was OK AristoRod 89 (Mn4Ni2CrMo, [38]). The OK AristoRod™ 89 filler wire was selected based on technological, metallurgical, and application-oriented criteria relevant to the PWHT strategy adopted in this study. Unlike the majority of published approaches to welding low-alloy high-strength steels, the present work intentionally assumed that all welded joints would undergo PWHT. Consequently, the choice of filler material could not rely solely on manufacturer-provided mechanical data, which typically refer to the as-welded condition without subsequent thermal processing. The filler material was therefore chosen according to the following requirements: (1) the ability to produce defect-free welds with low susceptibility to cold or delayed cracking, (2) suitability for multi-pass welding without loss of structural integrity, (3) a high propensity for hardening during PWHT, enabling the formation of a fully martensitic microstructure, (4) a chemical composition closely matching that of the base material, ensuring microstructural compatibility and minimizing heterogeneity within the welded joint. These criteria considerably narrow the range of commercially available welding consumables suitable for the adopted PWHT approach. OK AristoRod™ 89 met all of the above requirements and has been previously used by the authors in related research. This provided an additional advantage, as prior experience with this filler material allowed for precise optimization of welding parameters and ensured the reproducibility and reliability of the welded joints produced in the present study. No preheating was applied, and the interpass temperature was kept below 80 °C. The plates were welded without edge beveling. A schematic representation of the welded configuration is provided in Figure 2.

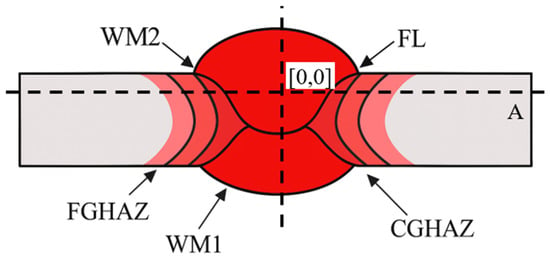

Figure 2.

General schematic of the welded joints of analyzed steel. A—line of hardness distribution measurements, CGHAZ—coarse-grained heat-affected zone; FGHAZ—fine-grained heat-affected zone, FL—fusion line, WM1/WM2—individual weld layers in the order they were made.

Welding operations were carried out using OK AristoRod™ 89 welding wire (Table 3). This is a solid, copper-free wire designed for MAG welding of very high-strength steels (Re < 900 MPa). OK AristoRod™ 89 is mainly used for welding structures such as lifting equipment, construction machinery, trucks, handling devices, and containers.

Table 3.

Properties of the filler used to create the welded joint [39].

All heat treatment operations were performed in gas-tight chamber furnaces (FCF 12SHM/R) manufactured by Czylok (Czylok, Jastrzębie-Zdrój, Poland), using a protective atmosphere of 99.95% argon. The quenching medium consisted of deoxidized water at a temperature not exceeding 30 °C. The heat treatment was performed according to the following parameters:

- Double normalization: 900 °C, 2 × 30 min, air cooling;

- Quenching: 930 °C, 20 min, water;

- Tempering: 100 °C, 5 h, air cooling.

The selection of heat treatment parameters was based on the chemical composition of both the base material and the weld metal, as well as on extensive preliminary experimental studies. Due to the significant microstructural alterations observed within HAZ of high-strength, low-alloy armor steels, a post-weld normalizing treatment was introduced as an essential step prior to quenching and tempering. The normalizing treatment was performed twice due to the substantial heat input generated during welding with the MAG process, which resulted in austenite grain growth, while a single-stage annealing treatment proved insufficient to eliminate the unfavorable microstructural changes. The normalizing temperature was selected experimentally to ensure the effective homogenization of the HAZ and weld metal. Austenitizing parameters were determined on the basis of the carbon content of the base steel and the weld metal, considering the need to achieve sufficient undercooling to obtain a fully martensitic microstructure across the entire joint. The selected quenching medium provided the required cooling rate to promote martensite formation through the full thickness of the welded plates. Tempering was carried out to relieve internal stresses generated during quenching. The selected parameters reflect the authors’ earlier experience with the heat treatment of high-strength armor steels and welded joints, confirming their suitability for the present investigation.

Hardness measurements on cross-sections of welded joints were performed using the Rockwell method (HRA) in accordance with [40], employing a universal hardness tester with a 60 kgf (588.399 N) load (ZwickRoell, Ulm, Geramny). The obtained hardness values were converted to the Vickers scale according to [41]. Measurements were carried out on cross-sections of specimens in the as-welded condition and after PWHT. Hardness profiles were measured using three independent traverses. The locations of the hardness profiles are schematically indicated by line A in Figure 2.

Microstructural observations were performed using a Nikon Eclipse MA200 light microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Prior to imaging, the specimens were etched in a 3% nitric acid solution following the ASTM E407 standard [42]. Examinations of the worn surfaces after abrasive testing were carried out with a Phenom XL (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) scanning electron microscope SEM). The analyses were conducted using a secondary electron (SE) imaging, with the accelerating voltage set to 15 keV.

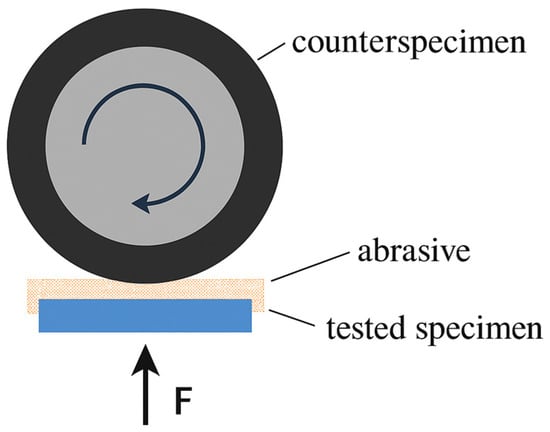

Abrasion resistance was evaluated using a T-07 tribological (Łukasiewicz—Institute for Sustainable Technologies, Radom, Poland) tester operating with loose abrasive (Figure 3), following the procedure specified in [43]. The tests were conducted under a constant load of F = 44 N (±0.25 N). The hardness of the rubber lining the wheel ranged between 78 and 85 ShA. Test specimens with dimensions 30 × 30 × 10 mm were used. Each test condition was evaluated on six independent specimens per condition, ensuring statistical repeatability of the results. Electrofused alumina grade No. 90, compliant with [44], served as the abrasive medium. The duration of each test was adjusted to the hardness of the examined steel and set at 1800 wheel revolutions (corresponding to 30 min). Mass loss was determined using a precision laboratory balance with a resolution of 0.0001 g. The purpose of the experiment was to calculate the relative abrasion resistance coefficient (kb) with respect to a reference material—C45 steel in the normalized condition. The coefficient kb was determined using Equation (1):

where

Figure 3.

Layout of the T-07 tribotester.

- kb—relative abrasion resistance coefficient;

- Zw—weight loss of reference samples in [g];

- Zb—weight loss of the tested material in [g];

- Nw—number of roller revolutions during testing of the reference sample;

- Nb—number of roller revolutions during testing of the sample;

- ρw, ρb—density of the reference sample material and the tested material [g/cm3].

Surface topography of the specimens was examined using a HITACHI TM-3000 scanning electron microscope (Hitachi, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) equipped with dedicated 3D Viewer Version 2.1.0 software, which enabled visualization and quantitative assessment of height variations along the Z-axis. Prior to the measurements, each sample was cleaned with a dry stream of compressed air, visually inspected to exclude mechanically damaged regions, and marked at three predetermined locations selected for detailed surface characterization. All surface examinations were performed at a constant magnification and an accelerating voltage of 15 kV, with the evaluation length set to ten times the elementary segment lr = 198.03 μm, giving a total analyzed distance of approximately 1980 μm. Before commencing the measurements, the microscope was calibrated for working distance (WD) using a certified roughness reference specimen with a known profile.

3. Results

3.1. Metallographic Analysis

The chemical composition of the weld metal is characterized by a low carbon content of 0.12 wt.% (Table 4 and Table 5). The presence of manganese (0.83 wt.%) and chromium (0.36 wt.%) contributes to increased hardenability. Notably high concentrations of nickel (2.02 wt.%) and molybdenum (0.56 wt.%) were recorded; these elements not only enhance the strength properties of the steel but also promote ductility, allowing tempering to be carried out with a reduced risk of temper embrittlement. Furthermore, the weld metal exhibits very low phosphorus and sulfur contents (0.008 wt.% and 0.002 wt.%, respectively) and contains a microaddition of boron (0.0014 wt.%), which significantly increases its hardenability.

Table 4.

Chemical composition and carbon equivalent values of the weld metal. CEV—carbon equivalent according to IIW; CET—carbon equivalent according to [37].

Table 5.

Chemical composition of the weld metal.

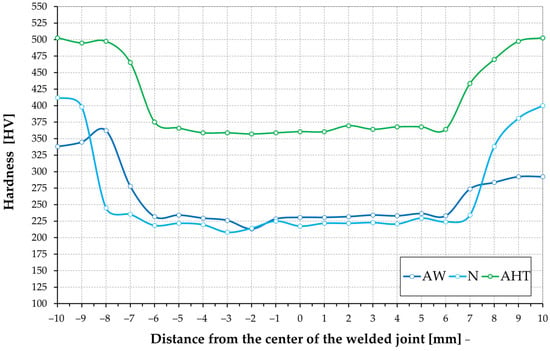

The average hardness of the base material is 503 HV (measured at points −10.0 and 10.0 mm, highlighted by the green curve “AHT”) (Figure 4). Welding processes lead to a reduction in hardness within the weld metal, reaching values between 210 and 240 HV, which corresponds to approximately 45% of the base material hardness (blue color, labeled “AW”, range from −5.0 to +5.0 mm in Figure 4). It should be noted that, in all analyzed conditions, the hardness of the base material remains higher than that of the weld metal, even in specimens subjected to normalizing. Under this heat treatment condition, the weld metal hardness is approximately 217 HV, whereas the base material reaches around 410 HV, indicating increased hardenability due to higher carbon and chromium content.

Figure 4.

Hardness distribution of the analyzed welded joint along line A marked in Figure 2, AW—joint after welding, AHT—heat-treated, N—as-normalized.

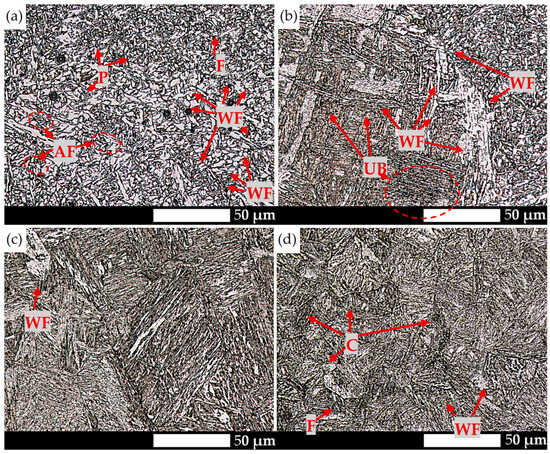

The presence of adverse microstructural changes within the welded joint region is confirmed by the micrographs of all characteristic zones (Figure 5). Their morphology differs markedly from the initial condition due to heating of the material both above and below the austenitizing temperature. As a result, diffusion-controlled transformations occurred, leading to the formation of a tempered martensitic microstructure. As shown in Figure 5a, the microstructure of the weld metal consists predominantly of acicular (Widmanstätten) ferrite, where the growth of individual ferrite needles proceeds parallel to a limited number of habit planes of the matrix. Consequently, within a single prior austenite grain, the ferrite plates exhibit a parallel orientation with respect to each other. The presence of intragranular acicular ferrite is also observed; it nucleates independently within the grains on oxides, sulfides, or silicates, and its plates are randomly oriented. Additionally, allotriomorphic ferrite is found along the former austenite grain boundaries, while finely dispersed pearlite occurs in minor quantities. Along the fusion line, the microstructure remains characteristic of the weld metal; however, the ferrite exhibits an elongated morphology, resulting from its solidification in the direction of the maximum thermal gradient (Figure 5b). The coarse-grained heat-affected zone (CGHAZ) is composed mainly of upper bainite and lower bainite or tempered martensite (Figure 5c). Locally, the presence of Widmanstätten ferrite and finely dispersed pearlite is also observed, particularly in the region adjacent to the fusion line (Figure 5b). In the fine-grained heat-affected zone (FGHAZ), the microstructure consists primarily of tempered martensite, characterized by a distinct carbide network along the former austenite grain boundaries, with small fractions of upper bainite and/or Widmanstätten ferrite (Figure 5d).

Figure 5.

Microstructure of the analyzed welded joint; designation according to Figure 2: (a) weld material (WM), (b) fusion line (FL); (c) coarse-grained heat-affected zone (CGHAZ), (d) fine-grained heat-affected zone (FGHAZ). P—pearlite, AF—acicular ferrite, F—allotriomorphic ferrite, C—carbides, UB—upper bainite, WF—Widmanstätten ferrite, Light microscopy, etched with 3% HNO3.

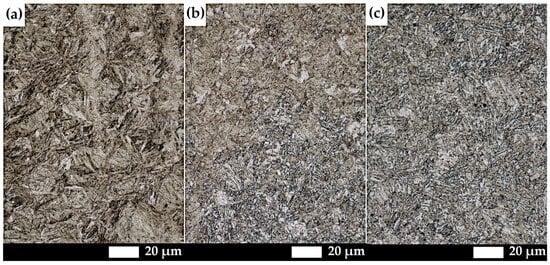

The microstructure of the base material in the as-normalized condition consists mainly of martensite or lower bainite, confirming the high hardenability of the investigated steel (Figure 6a). At the same time, the presence of banding and distinct carbide precipitates along the former austenite grain boundaries can be observed, resulting from slower cooling rates after soaking. Locally, small amounts of ferrite are also present. A distinct change in microstructural morphology is evident in the fusion line region (Figure 6b). The weld metal exhibits heterogeneous microstructures, including globular bainite, upper bainite, and Widmanstätten ferrite (Figure 6c). Application of PWHT results in the formation of a uniform martensitic microstructure across all characteristic zones of the welded joint. In the weld metal region, the presence of fresh martensite is observed, which arises from the lower carbon content of the filler material and the limited potential for carbide precipitation in the interblock regions of martensite (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Microstructure of the analyzed material in the as-normalized condition; (a) base material; (b) fusion line; (c) weld material. Light microscopy, etched with 3% HNO3.

Figure 7.

Microstructure of the analyzed welded joint after complex heat treatment: (a) fusion line; (b) weld material. Light microscopy, etched with 3% HNO3.

3.2. Abrasive Wear Resistance Tests

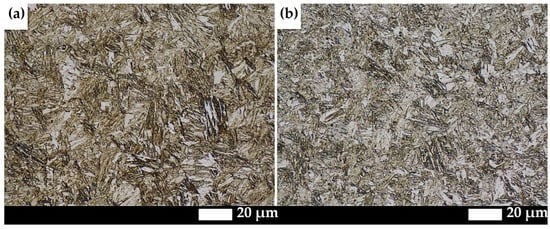

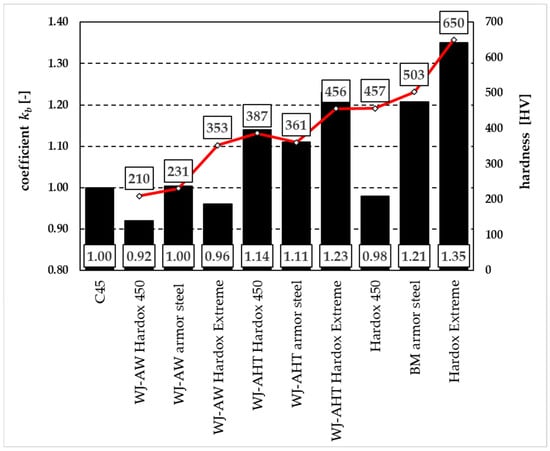

Figure 8 presents the values of the relative abrasive wear resistance coefficient (kb) of the welded joint in various heat treatment conditions, along with the corresponding hardness values (HV). The hardness of the weld metal was determined at a point located +3.00 mm from the weld axis, as indicated in Figure 4. The tribological tests revealed that the welded joint in the as-welded condition exhibited the lowest kb value (kb = 0.98 ± 0.01), whereas the base material of the armor steel demonstrated the highest resistance, with kb = 1.18 ± 0.02. The application of post-weld heat treatment led to an increase in the abrasive wear resistance of the welded joint, reaching kb = 1.08 ± 0.01. For the normalized base material and normalized weld metal, the respective values were 1.10 ± 0.02 and 1.00 ± 0.02. It should be emphasized that hardness correlates strongly with the measured abrasive wear resistance indicators. The only deviation from this trend is observed in the normalized condition, where—despite a hardness decrease of 9 HV units—the welded joint exhibits a 0.02 higher kb value compared to the as-welded state. This phenomenon can be attributed to the beneficial effect of normalization, which promotes microstructural refinement. Furthermore, the low standard deviations of the obtained results indicate their high reproducibility and uniformity.

Figure 8.

Relative abrasion resistance coefficients of analyzed armor steel and welded joint. C45—steel with a hardness of 220 HBW in the as-normalized condition; WJ-AW—welded joint in the as-welded condition, WJ-N—welded joint in the normalized condition, BM-N—base material in the normalized condition, WJ-AHT—welded joint in the post-heat-treated condition, BM—base material. Average values with standard deviation.

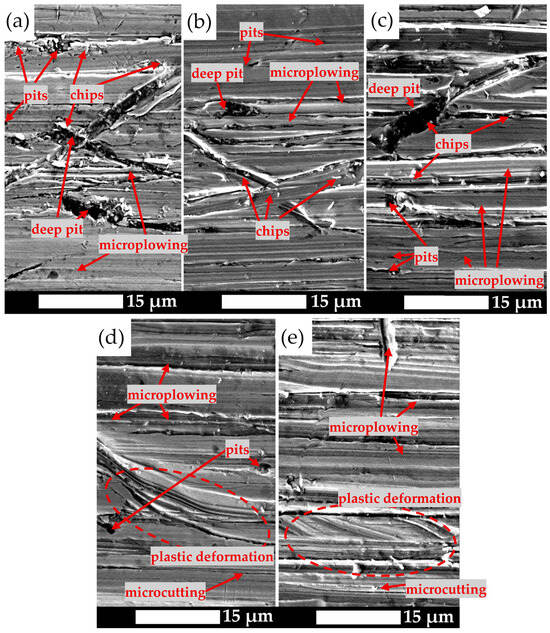

Figure 9 presents the surfaces of the specimens after abrasive wear testing. Examination of the microphotographic documentation indicates that the width of the grooves and pits formed is the greatest for the welded joint specimens in the as-welded condition. The wear tracks exhibit significant misalignment relative to the abrasive motion direction, and numerous chips are visible along their edges (Figure 9a–c). In the as-welded condition, in addition to deep pits resulting from the penetration of hard abrasive grains into the relatively soft matrix, the presence of cavities, wide grooves, and scratches arranged partially perpendicular to the abrasive movement direction is observed. Their proportion decreases markedly in the weld metal and base material after normalization, where the dominant wear mechanisms are microplowing and microscratching, accompanied by the formation of characteristic chips (Figure 9b). Distinct areas of abrasive particle penetration into the material are also visible, leading to the detachment of matrix fragments near the wider ends of the grooves. This phenomenon is associated with repeated local plastic deformation, followed by the removal of material fragments.

Figure 9.

Worn surfaces of the analyzed welded joint; (a) WJ-AW—welded joint in the as-welded condition, (b) WJ-N—welded joint in the normalized condition, (c) BM-N—base material in the normalized condition, (d) WJ-AHT—welded joint in the post-heat-treated condition, (e) BM—base material. SEM, unetched.

The application of PWHT results in a noticeable improvement in the surface quality of the tested specimens. The scratches are mostly parallel to the abrasive motion direction, and their local misorientation occurs only sporadically. In both the weld metal and base material, plastic deformation, the presence of grooves, and a few chips are mainly observed. Wear mechanisms related to microcutting play a marginal role in this case, and the few pits that appear are relatively shallow. Therefore, it can be concluded that the dominant wear mechanisms in the analyzed material, regardless of the applied heat treatment variant, are primarily associated with microplowing and microscratching, while the contribution of microcutting wear remains minor in all analyzed cases.

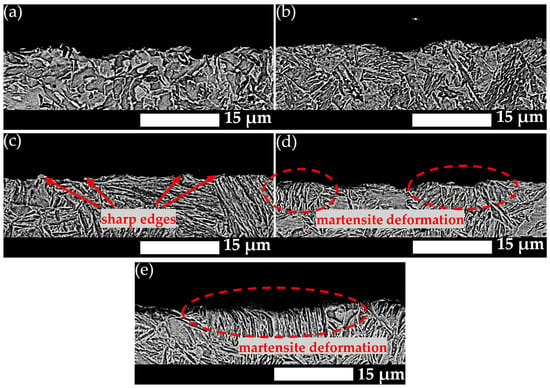

On the cross-sections of the specimens after abrasive wear testing, distinct wear traces in the form of grooves, pits, and local cavities are visible (Figure 10). For the welded joint in the as-welded, normalized, and heat-treated conditions, the material elevations exhibit a smooth and elongated morphology. Local plastic deformation leads to the rounding of some asperities, giving the edges a gentle, wavy appearance. However, in the normalized base material, sharp asperity tips were observed, indicating non-uniform wear of the individual microstructural phases. In the as-delivered condition, more pronounced deformation of the martensitic microstructure is observed, which indicates relatively high ductility of the material and its ability to absorb the impact energy of the abrasive particles through local deformation rather than by intensive fragmentation.

Figure 10.

Microstructure of subsurface regions subjected to abrasive wear tests: (a) WJ-AW—welded joint in the as-welded condition, (b) WJ-N—welded joint in the normalized condition, (c) BM-N—base material in the normalized condition, (d) WJ-AHT—welded joint in the post-heat-treated condition, (e) BM—base material. SEM, etched with 3% HNO3.

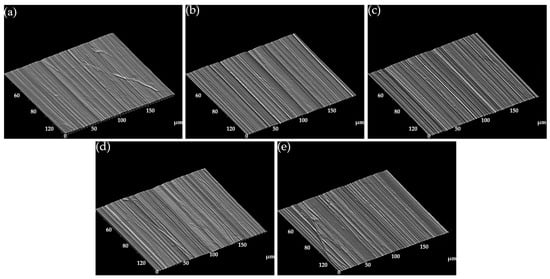

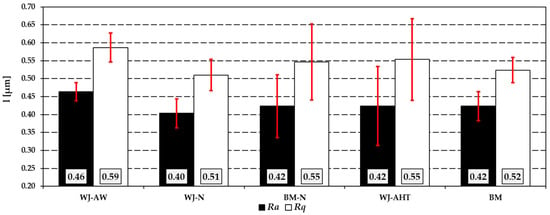

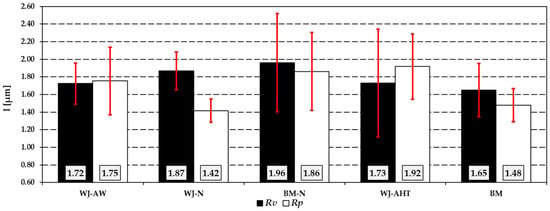

The surface topography reconstruction and roughness parameter evaluation after abrasive wear testing (Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13) complement the qualitative observations, enabling a precise characterization of the differentiated response of the investigated material conditions to abrasive interaction. For the welded joint in the as-welded condition (WJ-AW), the highest roughness parameter values were recorded (Ra = 0.46 µm, Rq = 0.59 µm, Rp = 1.75 µm, and Rv = 1.72 µm). Such high surface amplitude values result from the formation of deep pits, grooves, and material detachments, which arise due to the intensive penetration of hard abrasive particles into the relatively soft microstructure of the weld metal. A similar character of microdamage was also observed in the normalized condition; however, the roughness parameters were lower in this case (Ra = 0.40 µm, Rq = 0.51 µm, Rp = 1.87 µm, and Rv = 1.42 µm). This behavior can be associated with microstructural refinement and homogenization, which reduced the intensity of local surface defects. After the application of comprehensive heat treatment, a slight increase in roughness parameter values was noted compared to the normalized condition (Ra = 0.42 µm, Rq = 0.55 µm, Rp = 1.73 µm, and Rv = 1.92 µm). Nevertheless, the surface topography reveals predominantly parallel, relatively shallow scratches and grooves, indicating a change in the dominant micromechanism of wear.

Figure 11.

Three-dimensional images of sample surfaces subjected to wear testing along the longitudinal direction of abrasive movement; (a) WJ-AW—welded joint in the as-welded condition, (b) WJ-N—welded joint in the normalized condition, (c) BM-N—base material in the normalized condition, (d) WJ-AHT—welded joint in the post-heat-treated condition, (e) BM—base material.

Figure 12.

Roughness parameters Ra and Rq of the analyzed welded joint under different heat treatment conditions subjected to abrasive wear testing. Average values with standard deviation.

Figure 13.

Roughness parameters Rv and Rp of the analyzed welded joint under different heat treatment conditions subjected to abrasive wear testing. Average values with standard deviation.

It should also be emphasized that depth-related parameters Rv and Rp are particularly significant in assessing wear resistance, as they reflect the presence of deep surface defects that constitute the primary factor reducing abrasive wear resistance based on mass loss. In the as-welded condition, the Rp and Rv values are similar (1.75 µm and 1.72 µm, respectively), yielding an Rv/Rp ratio of 0.98. This indicates that the depths of the valleys and the heights of the peaks are comparable, suggesting intense abrasive interaction that leads both to the formation of grooves and pits and to the buildup of raised material around them. In the normalized condition, a distinct increase in the depth of valleys relative to peaks is observed (Rv = 1.87 µm, Rp = 1.42 µm, Rv/Rp = 1.32). This indicates the dominance of mechanisms associated with the formation of deep pits and scratches, with a limited contribution from elevations that arise either from plastic deformation of the material or from the detachment of previously raised fragments following rapid strain hardening. A similar relationship was observed for the normalized base material, where Rv and Rp values are close (1.96 µm and 1.86 µm, respectively), and the Rv/Rp ratio of 1.05 suggests a balance between valleys and peaks [45]. However, the higher absolute values of these parameters indicate a greater susceptibility of the material in this condition to microdamage induced by abrasive particles. Different results were obtained for samples subjected to comprehensive post-weld heat treatment. In this condition, the Rp value (1.92 µm) exceeds Rv (1.73 µm), and the Rv/Rp ratio decreases to 0.90. This relationship suggests a reduced intensity of deep pit formation and a predominance of microplowing and scratching mechanisms over material chipping. In contrast, the base material in the as-received condition (BM) is characterized by Rp = 1.48 µm and Rv = 1.65 µm (Rv/Rp = 1.11), indicating a slight predominance of depressions over elevations.

4. Discussion

The study presents the results of research on the abrasive wear resistance of welded joints of martensitic armor steel with a microaddition of boron. It was shown that the application of heat treatment allows for an improvement in the mechanical properties of the weld material, which, consequently, may contribute to increased durability of components operating under severe abrasive conditions.

The potential for improving the mechanical properties of the weld metal is primarily limited by the carbon content of commercially available welding consumables. Based on this, it can be stated that when welding steel with a hardness of 500 HBW, due to the carbon difference of 0.17% between the weld metal and the base material, achieving similar mechanical and tribological properties in the welded joint is significantly challenging. In the case analyzed, the mass loss of the heat-treated weld metal was greater than that of the base material. However, compared to the weld material in the as-welded condition, the obtained values are 55% more favorable. Similarly, for steel with a hardness of 466 HBW, it was shown that the weld made using the MAG method and subjected to heat treatment exhibits a kb value lower by 0.03 compared to the base material. It should be emphasized, however, that such a small difference—three times smaller than in the present study—is due to the limited chemical composition of the base material, whose hardenability is primarily associated with the microaddition of boron. These observations are consistent with results reported for welded joints of Hardox Extreme steel, which in all analyzed cases show lower abrasive wear resistance than the base material [46].

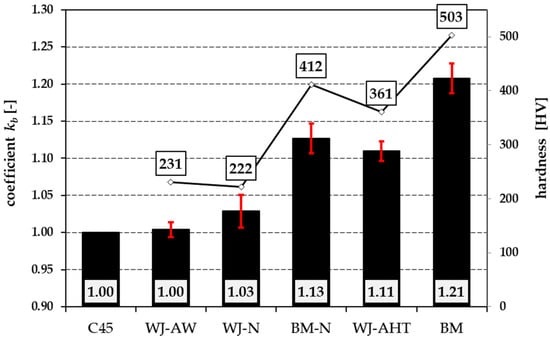

Figure 14 presents the results of abrasive wear resistance tests of welded joints of the analyzed armor steel, compared—based on available literature data—with the results obtained for Hardox 500 steel, as well as the base material and welded joints of Hardox 450 and Hardox Extreme steels [46]. To ensure the methodological consistency of the abrasion resistance comparison presented in Figure 14, all kb values were referenced to the same measurement framework. Specifically, the data shown in the figure were obtained under identical testing conditions, i.e., using the GOST 23.208-79 standard [43], electrofused alumina No. 90 as the loose abrasive, and comparable loading and test duration parameters. All studies included in the comparison were conducted on the T-07 tester where the kb coefficient is defined in an equivalent manner.

Figure 14.

Relative abrasion resistance indices of the analyzed martensitic steels and welded joints. C45—normalized C45 steel (hardness 220 HBW); WJ-AW—welded joint in the as-welded condition; WJ-AHT—welded joint after heat treatment; BM—base material.

For this reason, the comparison was normalized with respect to the same reference material—normalized C45 steel—which serves as the baseline for calculating the abrasion resistance coefficient. The use of a common reference ensures that the kb values reported in this work and in the cited literature are directly comparable. In all analyzed cases, the joints in the as-welded condition exhibited higher mass loss than C45 steel in the normalized state (hardness 220 HBW). It should be emphasized, however, that the application of heat treatment in all variants leads to a significant increase in abrasive wear resistance, providing performance exceeding that of steels with a declared hardness of 450 HBW. For welded joints produced using the submerged arc welding technique, the obtained abrasive wear resistance is comparable to that of steel with a declared hardness of 500 HBW—the kb coefficient for the welded joint of Hardox 450 steel and the base material of Hardox 500 steel is 1.14.

It should also be noted that the tribological resistance of the analyzed armor steel differs from that of Hardox 500, indicating that despite similar properties, the wear mechanisms and interaction characteristics with the abrasive material are not identical. Hardox 500 steel exhibits a carbon content comparable to that of the analyzed armor steel (C = 0.29%), as well as similar levels of manganese and chromium. A significant difference, however, lies in the higher nickel and molybdenum content. The microstructure of both the analyzed armor steel and as-delivered Hardox steel consists of fine-lath tempered martensite with occasional regions of fresh martensite. The hardness of Hardox 500 steel is 512 HV, which is only 9 HV units higher than that of the tested armor steel [46]. In this case, however, the steel with a 0.97% higher nickel content exhibits a more favorable wear resistance—the kb coefficient for Hardox 500 steel is lower by 0.04 compared to the analyzed armor steel. The presence of nickel promotes increased ductility and impact toughness, allowing for more effective dissipation of mechanical energy in the contact zone with abrasive particles. This facilitates initial wear through microplowing, followed—through repeated plastic deformation and resulting strain hardening—by wear via microfatigue or microcutting. Similar conclusions were presented in [47], where a heat-treated welded joint of Hardox 450 steel, produced by submerged arc welding, exhibited lower mass loss compared to the base material. The tests were conducted using both loose abrasive and soil mass presenting higher resistance. In this case, the nickel content in the weld material was 0.81% higher, while the carbon content was 0.04% lower than in the base material.

The proposed technology provides a significant improvement compared to the results reported in the available literature. In [48], the effect of welding processes on abrasive wear was analyzed for a low-carbon, manganese shipbuilding steel with a distinctly banded ferritic–pearlitic microstructure. Although the weld metal exhibited higher hardness, greater mass loss was observed compared to the base material. This phenomenon was attributed to the lower carbon content, the presence of residual stresses, and the differing microstructure. For Armox 500T steel—characterized by properties similar to high-strength martensitic steels—it was found that the wear processes within the welded joint occur with an intensity three to four times higher than in the base material [49]. In [49], it was shown that XAR 400 steel exhibits the highest wear rate in the heat-affected zone, which gradually decreases with increasing distance from the weld axis, i.e., towards regions of the material less affected by heat. It should be emphasized that within the weld metal itself, only slight differences in wear rate were observed between its lower and upper portions, approximately half of those recorded in the HAZ. Such minor variation within the weld indicates the homogeneity of its microstructure compared to the HAZ, where intensive thermal exposure promotes more pronounced microstructural heterogeneities and, consequently, greater variability in wear resistance. For welded joints made of low-alloy martensitic steel containing 0.28% carbon, abrasive wear intensifies as the measurement location approaches the weld centerline [50]. Preliminary observations for joints fabricated by laser welding—where the energy is highly concentrated and the resulting heat-affected zone remains very narrow—have also been published [51]. Despite the advantages associated with this welding technique, the abrasion-resistant steels examined (with tensile strengths of 1407 MPa and 1603 MPa) showed the highest friction coefficients within the weld metal region.

It should be highlighted that the previously referenced works did not investigate welded joints in a heat-treated state. Although the study presented in [52] yielded encouraging outcomes, the examined joint exhibited limited resistance under dynamic loading conditions. Moreover, the observations reported in [53] indicate that, for both rail welds and the parent rail material, the volume of impact wear increases with the number of impact cycles and the level of applied normal force. Despite this, the welded joint displays better resistance to plastic deformation than the base material. As the number of impacts and load intensity rise, the dominant wear mechanisms evolve: in the rail steel from adhesive to fatigue wear, and in the welded joint from peeling to fatigue wear. Under more severe loading and higher impact frequencies, fatigue wear ultimately becomes the principal degradation mode in the weld joint.

In the normalized condition, the welded joint exhibits a kb value comparable to that obtained in the as-welded state, despite its lower hardness. This effect results from the heat treatment, which promotes the formation of a fine-grained microstructure free of residual stresses. It is worth noting that the abrasive wear resistance of the base material in the normalized state also remains comparable to that of the heat-treated welded joint. Despite the base material exhibiting a hardness higher by 51 HV, the difference in the kb coefficient between these two conditions is only 0.02. This behavior can be attributed to the elevated carbon content and the presence of alloying elements that enhance hardenability—such as boron, nickel, vanadium, manganese, and molybdenum (the latter exerting the strongest effect according to Grossman). As a result, the microstructure of the normalized base material is dominated by martensite, whose mechanical properties are superior to those of the martensite present in the weld metal. However, this phase is more susceptible to chipping and wear through micro-cutting. Moreover, the abrasion process progresses unevenly across the constituent phases. Hard carbide precipitates, located primarily along the prior austenite grain boundaries, exhibit significantly greater resistance to wear compared to the softer martensitic–bainitic–ferritic matrix. Consequently, phases containing coherent carbide precipitates play a particularly important role in enhancing local wear resistance. This phenomenon, when wear resistance is evaluated solely based on mass loss, results in a lower kb value. The high plasticity of materials with increased nickel content has already been discussed in this paper in the context of differences between the wear behavior of the investigated armor steel and Hardox 500 steel. However, a similar relationship can also be observed when comparing the normalized base material of the analyzed boron steel with the more ductile weld metal.

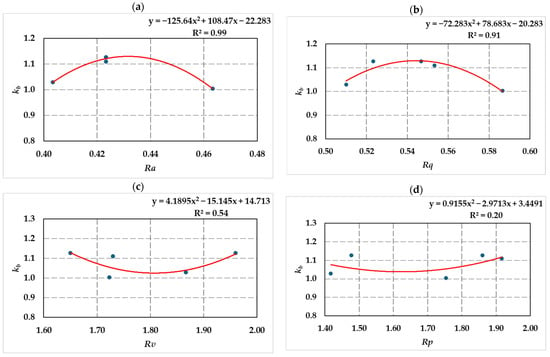

An interesting issue is the relationship between surface roughness parameters and abrasive wear resistance, expressed by the kb coefficient (Figure 15). Since the roughness measurements were carried out after the abrasive wear tests, the correlations reflect the combined effect of microstructural state, hardness distribution, and wear mechanisms on the resulting surface topography. Due to the limited number of experimental conditions, originating from the discrete PWHT variants, the polynomial fits should be interpreted as descriptive tools illustrating tendencies rather than as predictive statistical models. For small datasets of this type, low-order second-degree polynomial fitting is commonly used to visualize non-linear trends without introducing artificial overfitting. It should be emphasized that the objective of the fitting was not to produce a statistically model, but rather to support a qualitative interpretation of the observed relationships. The results revealed that, beyond a certain threshold, an increase in the roughness parameters Ra and Rq leads to a pronounced decrease in the kb value. The obtained relationships were approximated by a second-degree polynomial, with a coefficient of determination R2 ranging from 0.91 to 0.99. This indicates that, once a critical roughness level is exceeded, more pronounced surface irregularities after testing correspond to more intensive wear processes within the material. For the depth-related parameters (Rv, Rp), no such clear dependencies were observed. The relatively low determination coefficients (R2 = 0.20 for Rp and R2 = 0.54 for Rv) suggest that the occurrence of individual deep surface defects is not a sufficient quantitative criterion of tribological resistance. This result implies that the amplitude parameters Ra and Rq, which represent the averaged surface topography, provide a more reliable measure of wear behavior. These parameters better reflect the overall effect of the abrasive medium, encompassing scratches, grooves, and small pits. This can be attributed to the fact that isolated pits or cavities may occur randomly and do not necessarily represent the general degree of surface degradation. It can therefore be concluded that Ra and Rq act as diagnostic indicators more closely correlated with macroscopic wear resistance, while Rv and Rp play an auxiliary role and do not determine the material’s overall response under abrasive conditions. Nevertheless, minimizing local surface damage through appropriately selected heat treatment is important and can be achieved via microstructural modifications leading to increased hardness. A comparison between the armor steel in the as-delivered and normalized conditions and its welded joints showed that this material is characterized by relatively low roughness values, with microplowing and microscratching identified as the dominant wear mechanisms. This corresponds to favorable kb values, confirming that a homogeneous and fine-grained microstructure contributes to minimizing material loss under abrasive conditions. The obtained results are consistent with previous observations indicating that PWHT reduces surface roughness and the number of deep surface defects, which directly translates into improved resistance to abrasive wear compared to the as-welded condition.

Figure 15.

Relationship between the relative abrasion resistance coefficient (kb) and selected surface roughness parameters: (a) kb(Ra), (b) kb(Rq), (c) kb(Rv), (d) kb(Rp).

5. Conclusions

Based on the presented results, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- The welded joint in the as-welded condition is characterized by a dendritic microstructure dominated by Widmanstätten ferrite, acicular ferrite, and allotriomorphic ferrite, with bainite and pearlite occurring only locally. The hardness of the weld metal ranges from 210 to 240 HV, corresponding to approximately 45% of the base material hardness (503 HV), which results in the lowest abrasive wear resistance (kb = 0.98 ± 0.01).

- In the normalized condition, the microstructure is refined and consists mainly of bainite and tempered martensite with carbide precipitates along the prior austenite grain boundaries. The hardness of the weld metal is approximately 217 HV, and that of the base material is about 410 HV. Despite the lower hardness compared to the as-welded state, the abrasive wear resistance increased (kb = 1.00 ± 0.02 for the weld metal and 1.10 ± 0.02 for the base material), which can be attributed to the microstructural homogenization achieved through normalization.

- After the application of comprehensive post-weld heat treatment, a uniform martensitic microstructure was obtained throughout all zones of the joint, with fresh martensite observed in the weld metal. The hardness of the weld metal increased to 370–390 HV, while the base material retained its original hardness of 503 HV. The abrasive wear resistance coefficient reached kb = 1.08 ± 0.01, representing an improvement of approximately 55% compared to the as-welded state.

- Surface examinations after abrasive wear testing revealed that, in the as-welded and normalized states, deep grooves, pits, and local material detachments predominated. Following the post-weld heat treatment, the surface was characterized by shallow, parallel scratches and traces of plastic deformation, indicating a shift in the dominant wear mechanisms towards microscratching and microplowing.

- The roughness parameter analysis confirmed a distinct differentiation of surface topography depending on the applied heat treatment condition. The highest values of all evaluated parameters were recorded for the as-welded joint, resulting from the presence of deep cavities and pits caused by the intensive penetration of abrasive particles. The application of post-weld heat treatment led to a clear surface smoothing effect, as reflected by the reduction in the ratio of depth-related parameters. Among the analyzed parameters, Ra and Rq demonstrated the strongest correlation with abrasive wear resistance, indicating their high prognostic relevance.

- Depth-related parameters, particularly their mutual relationship, can serve as sensitive indicators of the prevailing wear micromechanisms and the tribological response of materials. The analysis of the Rv/Rp ratio revealed that in the normalized state, wear processes are dominated by the formation of deep pits (Rv/Rp > 1), while after the post-weld heat treatment, their occurrence is significantly reduced, with wear mechanisms shifting towards microplowing and microscratching (Rv/Rp < 1).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z. and B.B.; methodology, M.Z., B.B., M.S. and Ł.K.; validation, M.Z., B.B. and Ł.K.; formal analysis, M.Z. and B.B.; investigation, M.Z., B.B. and M.S.; resources, M.Z. and Ł.K.; data curation, M.Z. and B.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z. and B.B.; writing—review and editing, M.Z., B.B. and Ł.K.; visualization, M.Z. and B.B.; supervision, Ł.K.; project administration, M.Z. and B.B.; funding acquisition, M.Z., B.B. and Ł.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Frydman, S.; Konat, Ł.; Pękalski, G. Structure and Hardness Changes in Welded Joints of Hardox Steels. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2008, 8, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskutis, S.; Baskutiene, J.; Dragašius, E.; Kavaliauskiene, L.; Keršiene, N.; Kusyi, Y.; Stupnytskyy, V. Influence of Additives on the Mechanical Characteristics of Hardox 450 Steel Welds. Materials 2023, 16, 5593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konat, Ł.; Zemlik, M.; Jasiński, R.; Grygier, D. Austenite Grain Growth Analysis in a Welded Joint of High-Strength Martensitic Abrasion-Resistant Steel Hardox 450. Materials 2021, 14, 2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białobrzeska, B.; Konat, Ł.; Jasiński, R. The Influence of Austenite Grain Size on the Mechanical Properties of Low-Alloy Steel with Boron. Metals 2017, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Haowei, M.; Yarigarravesh, M.; Assari, A.H.; Tayyebi, M.; Tayebi, M.; Hamawandi, B. Microstructure, Fractography, and Mechanical Properties of Hardox 500 Steel TIG-Welded Joints Using Different Filler Weld Wires. Materials 2022, 15, 8196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teker, T.; Gencdogan, D. Heat Affected Zone and Weld Metal Analysis of HARDOX 450 and Ferritic Stainless Steel Double Sided TIG-Joints. Mater. Test. 2021, 63, 923–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Sharma, V.; Kumar, P.; Thakur, A. Investigating the Effect of Ferritic Filler Materials on the Mechanical and Metallurgical Properties of Hardox 400 Steel Welded Joints. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 39, 1640–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochenka, P.; Janiszewski, J.; Kucewicz, M. Crash Response of Laser-Welded Energy Absorbers Made of Docol 1000DP and Docol 1200M Steels. Materials 2021, 14, 2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turichin, G.; Kuznetsov, M.; Klimova-Korsmik, O.; Sklyar, M.; Zhitenev, A.; Kurakin, A.; Pozdnyakov, A. Laser-Arc Hybrid Welding of Ultra-High Strength Steels: Influence of Weld Metal Composition on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties. Procedia CIRP 2018, 74, 752–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konat, Ł. Structural Aspects of Execution and Thermal Treatment of Welded Joints of Hardox Extreme Steel. Metals 2019, 9, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konat, Ł. Technological, Microstructural and Strength Aspects of Welding and Post-Weld Heat Treatment of Martensitic, Wear-Resistant Hardox 600 Steel. Materials 2021, 14, 4541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtonen, K.; Keltamäki, K.; Kuokkala, V.-T. High-Stress Abrasion of Wear Resistant Steels in the Cutting Edges of Loader Buckets. Tribol. Int. 2018, 119, 707–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, N.; Joseph, T.; Mendez, P.F. Issues Associated with Welding and Surfacing of Large Mobile Mining Equipment for Use in Oil Sands Applications. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2015, 20, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gáspár, M. Effect of Welding Heat Input on Simulated HAZ Areas in S960QL High Strength Steel. Metals 2019, 9, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Yoo, K.J.; Tran, M.T.; Moon, I.Y.; Oh, Y.-S.; Kang, S.-H.; Kim, D.-K. Effect of Quenching-Tempering Post-Weld Heat Treatment on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Laser-Arc Hybrid-Welded Boron Steel. Materials 2019, 12, 2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Peer, A.; Abke, T.; Kimchi, M.; Zhang, W. Subcritical Heat Affected Zone Softening in Hot-Stamped Boron Steel during Resistance Spot Welding. Mater. Des. 2018, 155, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramowicz, M.; Kulesza, S.; Lewalski, P.; Szatkowski, J. Structural Studies of Welds in Wear-Resistant Steels. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2016, 130, 963–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, R.; Słania, J.; Golański, G.; Zieliński, A. Evaluation of the Properties and Microstructure of Thick-Walled Welded Joint of Wear Resistant Materials. Materials 2022, 15, 7009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzunali, U.Y.; Cuvalcı, H.; Atmaca, B.; Demir, S.; Özkaya, S. Mechanical Properties of Quenched and Tempered Steel Welds. Mater. Test. 2022, 64, 1662–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.P.; Węgrzyn, T.; Szymczak, T.; Szczucka-Lasota, B.; Łazarz, B. Hardox 450 Weld in Microstructural and Mechanical Approaches after Welding at Micro-Jet Cooling. Materials 2022, 15, 7118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtonen, K.; Ojala, N.; Haiko, O.; Kuokkala, V.-T. Comparison of Various High-Stress Wear Conditions and Wear Performance of Martensitic Steels. Wear 2019, 426–427, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, J.; Das, K.; Das, S. An Investigation of Mechanical Property and Sliding Wear Behaviour of 400 HV Grade Martensitic Steels. Wear 2020, 458–459, 203436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankauskas, V.; Žunda, A.; Katinas, A.; Tučkutė, S. Wear Study of Bulk Cargo Vehicle Body Materials Used to Transport Dolomite. Coatings 2025, 15, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katinas, E.; Jankauskas, V.; Kazak, N.; Michailov, V. Improving Abrasive Wear Resistance for Steel Hardox 400 by Electro-Spark Deposition. J. Frict. Wear 2019, 40, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haiko, O.; Javaheri, V.; Valtonen, K.; Kaijalainen, A.; Hannula, J.; Kömi, J. Effect of Prior Austenite Grain Size on the Abrasive Wear Resistance of Ultra-High Strength Martensitic Steels. Wear 2020, 454–455, 203336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhamedov, A.A. Strength and Wear Resistance in Relation to the Austenite Grain Size and Fine Structure of the Steel. Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 1968, 10, 526–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojacz, H.; Katsich, C.; Kirchgaßner, M.; Kirchmayer, R.; Badisch, E. Impact-Abrasive Wear of Martensitic Steels and Complex Iron-Based Hardfacing Alloys. Wear 2022, 492–493, 204183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratia, V.; Rojacz, H.; Terva, J.; Valtonen, K.; Badisch, E.; Kuokkala, V.-T. Effect of Multiple Impacts on the Deformation of Wear-Resistant Steels. Tribol. Lett. 2015, 57, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindroos, M.; Valtonen, K.; Kemppainen, A.; Laukkanen, A.; Holmberg, K.; Kuokkala, V.-T. Wear Behavior and Work Hardening of High Strength Steels in High Stress Abrasion. Wear 2015, 322–323, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundström, A.; Rendón, J.; Olsson, M. Wear Behaviour of Some Low Alloyed Steels under Combined Impact/Abrasion Conditions. Wear 2001, 250, 744–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahr, K.-H.Z. Wear by Hard Particles. Tribol. Int. 1998, 31, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, A.; Dehghani, K.; Bahaaddini, K.; Abbasi Hataie, R. Experimental Comparison of Abrasive and Erosive Wear Characteristics of Four Wear-Resistant Steels. Wear 2018, 416–417, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, N.; Valtonen, K.; Heino, V.; Kallio, M.; Aaltonen, J.; Siitonen, P.; Kuokkala, V.-T. Effects of Composition and Microstructure on the Abrasive Wear Performance of Quenched Wear-Resistant Steels. Wear 2014, 317, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SSAB. High-Strength Steel Sheet, Plate, Coil, Tube, Profile; SSAB: Stockholm, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasiuk, W.; Napiórkowski, J.; Ligier, K. Impact of Slip Speed on the Wear Intensity of 38GSA and Hardox 500 Steels. Q. Tribol. 2018, 280, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasiuk, W.; Napiórkowski, J.; Ligier, K.; Krupicz, B. Comparison of the Wear Resistance of Hardox 500 Steel and 20MnCr5. Q. Tribol. 2017, 273, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1011-2:2001; Welding—Recommendations for Welding of Metallic Materials—Part 2: Arc Welding of Ferritic Steels. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2001.

- EN ISO 16834-A:2025; Welding Consumables—Wire Electrodes, Wires, Rods and Deposits for Gas-Shielded Arc Welding of High-Strength Steels—Classification (System Based on Yield Strength + 47 J Impact Energy. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025.

- ESAB. Welding Consumables; ESAB: North Bethesda, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- EN ISO 6508-1:2016; Metallic Materials—Rockwell Hardness Test—Part 1: Test Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- EN ISO 18265:2014; Metallic Materials—Conversion of Hardness Values. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ASTM E407-07(2015)e1; Standard Practice for Microetching Metals and Alloys. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- GOST 23.208-79; Metallic Materials—Methods for Testing Wear Resistance Under Abrasive Conditions. Russian Technical Standard: Moscow, Russia, 1979.

- ISO 8486-2:1998; Abrasive Grains—Testing—Part 2: Determination of Bulk Density. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998.

- Hebda, M.; Wachal, M. Tribology; Scientific and Technical Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zemlik, M.; Konat, Ł.; Białobrzeska, B.; Stachowicz, M.; Hanszke, J. The Influence of Grain Size on the Abrasive Wear Resistance of Hardox 500 Steel. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemlik, M.; Konat, Ł.; Lemecha, M.; Ligier, K.; Napiórkowski, J. Tribological and Mechanical Aspects of the Welding and Post-Weld Heat Treatment of High Strength, Wear-Resistant Martensitic Boron Steel. J. Tribol. 2026, 148, 110271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.N.; Toppo, V.; Basak, A.; Ray, K.K. Wear Behaviour of a Steel Weld-Joint. Wear 2006, 260, 1285–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligier, K.; Bramowicz, M.; Kulesza, S.; Lemecha, M.; Pszczółkowski, B. Use of the Ball-Cratering Method to Assess the Wear Resistance of a Welded Joint of XAR400 Steel. Materials 2023, 16, 4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligier, K.; Napiórkowski, J.; Lemecha, M. Assessment of Changes in Abrasive Wear Resistance of a Welded Joint of Low-Alloy Martensitic Steel Using Microabrasion Test. Materials 2024, 17, 2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, X. Study on Microstructure and Sliding Wear Behavior of Similar and Dissimilar Welded Joints Produced by Laser-Arc Hybrid Welding of Wear-Resistant Steels. Wear 2025, 562–563, 205643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshanghias, A.; Barzegari, M.; Kokabi, A.H.; Mirazizi, M. The Effects of Functionally Graded Material Structure on Wear Resistance and Toughness of Repaired Weldments. Mater. Des. 2011, 32, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.J.; Liu, C.; He, C.G.; Guo, J.; Wang, W.J.; Liu, Q.Y. Investigation on Impact Wear and Damage Mechanism of Railway Rail Weld Joint and Rail Materials. Wear 2017, 376–377, 1938–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).