Abstract

In the initial stages of Connected and Autonomous Vehicles (CAVs) development, the deployment of dedicated lanes for autonomous driving is an important measure to improve traffic efficiency and safety. To study the impact of considering acceleration lane length on the design of highway merging areas in mixed traffic flow environments, as well as its correlation with road safety and traffic efficiency, two design schemes for acceleration lane length in highway merging areas with different positions of dedicated lanes were investigated: setting the dedicated lane on the innermost or outermost part of the main highway. By designing different road traffic volumes and market penetration rates of CAVs, SUMO simulation was used to analyze the impact of acceleration lane length in highway merging areas on road traffic from both a traffic efficiency and safety perspective under different CAV penetration rate conditions. The results show that although increasing acceleration lane length can improve average vehicle speed and reduce delay, its effect is not very significant. When the dedicated lane is set on the innermost part of the mainline, both average vehicle delay and speed performance are better than when it is designed on the outermost part. Increasing lane length leads to an upward trend in average speed but with limited growth rates—maximum growth ranges from 0.28% to 2% during off-peak periods and from 0.52% to 1.52% during peak periods. At the same time, increasing lane length reduces average delay by a range between 0.39 s to 1.74 s. Additionally, vehicle conflict occurrences decrease with increasing lane length during off-peak periods but show no significant change during peak periods.

1. Introduction

Transportation is a key driving force behind urban development, with expressways serving as critical links between cities and as vital arteries of economic growth [1]. While traffic flow on basic segments of expressways is generally unaffected by external disturbances, merging areas at entrance ramps are prone to increased vehicle conflicts due to the mandatory merging behavior of ramp vehicles and discretionary lane changes by vehicles on the mainline upstream [2]. This results in traffic turbulence, reduced average speeds, and increased delays, thereby forming bottleneck sections.

With policy support in China for building a strong transportation nation, the development and deployment of Connected and Autonomous Vehicles (CAVs) have accelerated [3]. However, as an emerging multidisciplinary technology [4], the intelligent connected transportation is a complex endeavor, and road traffic will remain in a mixed state where CAVs and Human-driven Vehicles (HVs) coexist for an extended period [5]. The resulting complexity of mixed traffic flow presents challenges for both theoretical research and traffic management.

As intelligent vehicle technologies advance, some scholars have explored the feasibility of implementing dedicated CAV lanes on expressways to alleviate congestion and enhance safety [6]. Studies have shown this is an effective traffic management measure, as separating CAVs and HVs not only maximizes the operational efficiency of CAVs but also simplifies traffic flow organization—facilitating both theoretical modeling and practical improvements in traffic efficiency and safety.

Several researchers have investigated dedicated CAV lanes from strategic and network perspectives. For example, Abdel-Aty et al. [7] examined suitable penetration rates for connected vehicles by simulating traffic performance under varying flow conditions and safety levels. Talebpour et al. [8] analyzed the impact of three different CAV lane management strategies on traffic congestion. Li [9] conducted a simulation-based analysis and found that when the CAV penetration rate reaches 40%, establishing a dedicated lane can significantly improve transportation efficiency compared to scenarios with 20% penetration. Wang [10] carried out a sensitivity analysis considering lane construction costs, CAV penetration, traffic demand, and lane capacity. From a policy and control angle, Zhang et al. [11] proposed a novel dynamic lane-level tolling method for CAV-dedicated lane sharing, while Qin et al. [12] explored dynamic control methods for CAV lanes in multi-lane mixed traffic environments. Han et al. [13] developed a connected CAV lane network design model to ensure CAV trips could be completed entirely via exclusive lanes. Furthermore, system-level evaluations, such as that by Long et al. [14], provide a macroscopic assessment of autonomous vehicle lane deployment strategies under mixed traffic flow.

Concurrently, significant research efforts have focused on the microscopic behaviors and control of CAVs, which are foundational to understanding traffic flow operations. This includes the development of advanced car-following models that consider risk assessment [15], vehicle-vehicle and vehicle-road interactions [16], stability under information uncertainties [17], cooperative platoon control [18], and energy optimization [19]. Studies have also begun to differentiate between the risk factors in car-following behaviors of automated and human-driven vehicles [20] and to analyze how equipping partial human-driven vehicles with V2V technology can improve overall capacity [21]. The stability and fundamental diagram of mixed traffic flow, considering factors like platoon intensity and multi-class time delay, have also been extensively modeled [22]. These microscopic studies are crucial as they determine how CAVs will ultimately interact in complex scenarios like highway merging.

The existing research on dedicated CAV lanes primarily focuses on expressway mainlines and microscopic control algorithms, while studies specifically addressing the geometric design of merging areas, particularly the critical parameter of acceleration lane length, remain limited. Although some pilot projects—such as Beijing–Xiong’an Expressway in China, I-94 in Chicago, and the EVRA project in France—have deployed real-world CAV lanes, they are mostly located on the innermost lanes. However, placing CAV lanes on the outermost side allows vehicles to enter or exit the highway without multiple lane changes, potentially simplifying merging operations [23]. This notion is supported by research into CAV behavior in diverging areas [24] and dynamic control methods for CAV-shared lanes at intersections [25], which highlight the importance of lane position on vehicle trajectories and control complexity.

It is evident that the location of a CAV lane alters the lane-changing demands of vehicles in the acceleration lane and reshapes traffic organization in merging areas. As a result, the influence of acceleration lane length on traffic operations may vary depending on the positioning of the CAV lane. While advanced control methods for CAVs in weaving segments [26] and cooperative decision-making from the opinion dynamics perspective [27] are being developed, their effectiveness is inherently constrained by the physical road geometry, such as the length provided for merging maneuvers. Similarly, two-stage adaptive CAV control methods for congestion mitigation [28] and assessments of CAV environmental benefits [29] operate within the framework defined by the infrastructure. Therefore, each lane placement strategy has its advantages and disadvantages, and it is worthwhile to study the impacts of acceleration lane length in merging zones under different CAV lane configurations.

The primary objective of this study is to investigate the layout of highway merging areas under mixed traffic flow conditions, considering different CAV lane placements, and to explore the relationship between acceleration lane length and traffic safety and efficiency. Through simulation experiments, this paper analyzes the impact of acceleration lane length on merging performance from the perspectives of traffic efficiency and safety under two CAV lane positioning strategies. The contributions of this study are threefold:

First, this study introduces the lateral position of the dedicated CAV lane as an essential geometric design factor in merging areas. Prior studies have focused mainly on dedicated lanes along basic freeway segments, whereas this research reveals how lane placement fundamentally reshapes lane-changing demand and merging interaction patterns.

Second, a comparative evaluation framework is established for two representative deployment schemes—placing the CAV lane on the innermost versus outermost side of the mainline. By combining different acceleration lane lengths, traffic demand levels, and CAV penetration rates, the framework provides a comprehensive assessment of efficiency and safety performance in mixed traffic conditions.

Third, the study quantitatively demonstrates that extending acceleration lane length offers only limited marginal improvements and that, under low CAV penetration, excessive extension may even increase delays. These findings highlight that dedicated lane placement exerts a far greater influence on merging-area performance than simple geometric expansion, offering practical guidance for CAV-ready expressway planning where roadway resources are constrained.

2. Methodology: Design of Research Schemes Considering the Position of Dedicated CAV Lanes

Existing studies on dedicated lanes for autonomous driving mostly assume the lanes are located on the innermost side of the roadway. However, placing the dedicated lane on the outermost side can facilitate smoother entry and exit of Connected and Autonomous Vehicles (CAVs) on expressways. Therefore, this study proposes two design schemes for expressway merging areas, based on different positions of the dedicated CAV lane: (a) Innermost Dedicated Lane Scheme: The dedicated CAV lane is positioned on the innermost side of the mainline (adjacent to the median). This configuration follows conventional dedicated lane placement and allows CAVs to maintain higher speeds in the inner lanes, which typically experience less lane-changing activity. (b) Outermost Dedicated Lane Scheme: The dedicated CAV lane is positioned on the outermost side of the mainline (adjacent to the shoulder). This configuration facilitates easier access for CAVs entering from on-ramps and exiting to off-ramps, reducing the need for multiple lane changes and potentially improving merging efficiency.

To simplify the research process, the following assumptions are made in this study:

- Human-driven Vehicles (HVs) are not allowed to enter the dedicated CAV lane;

- All CAVs in this study switch to manual driving mode before executing lane changes.

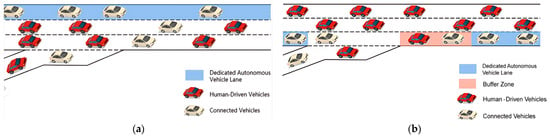

Figure 1 illustrates the design schemes for expressway merging areas considering two different CAV lane positions.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the design of highway merging areas at different autonomous driving lane locations. (a) Dedicated autonomous vehicle lanes are set up on the innermost lanes of the highway mainline. (b) Dedicated autonomous vehicle lanes are set up on the outermost lanes of the highway mainline.

As shown in Figure 1a, the innermost lane (Lane 3) of the expressway mainline is designated as a dedicated CAV lane, while the outermost lane (Lane 1) and the middle lane (Lane 2) are general-purpose lanes. Vehicles entering the mainline from the on-ramp accelerate along the acceleration lane and wait for a suitable merging gap to change lanes into the outermost lane. HVs are free to choose between Lane 1 and 2, whereas CAVs are required to change lanes to Lane 3 as soon as possible and switch to autonomous driving mode.

As shown in Figure 1b, the outermost lane of the expressway mainline is designated as the CAV lane, while the middle and innermost lanes are general-purpose lanes. A buffer zone that allows mixed traffic is set up in the merging area to enable HVs to exit Lane 1 as early as possible. Ramp vehicles accelerate along the acceleration lane and merge into the outermost lane when a suitable gap becomes available. CAVs remain in Lane 1 and switch to autonomous driving mode.

3. Simulation Experiment Design

This study investigates the impact of acceleration lane length (L) in highway merging areas under different traffic flow conditions and market penetration rates of connected and autonomous vehicles (CAVs), with respect to two CAV lane placement schemes. Two traffic demand levels are considered: off-peak and peak periods. During the off-peak period, the traffic volume on the mainline is 2000 pcu/h, and the ramp inflow is 200 pcu/h. During the peak period, the mainline traffic volume reaches 4500 pcu/h, with a ramp inflow of 450 pcu/h. Accordingly, the simulation experiments are conducted under four CAV penetration levels: 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40% [30].

According to the Design Specification for Highway Alignment [31], when the acceleration lane is a single lane, the recommended lengths are as follows: 230 m for a mainline design speed of 120 km/h, 200 m for 100 km/h, and 180 m for 80 km/h. In this simulation study, the acceleration lane lengths are set to 180 m, 200 m, 220 m, and 240 m. As summarized in Table 1, a total of 16 simulation scenarios are designed, and each scenario is tested under different CAV penetration rates through randomized experiments.

Table 1.

Simulation protocol design.

4. Microscopic Traffic Simulation Model Parameter Settings

This study utilizes the microscopic traffic simulation software SUMO to build a one-way three-lane highway environment with a dedicated lane for autonomous vehicles, using its built-in car-following and lane-changing models.

4.1. Car-Following Model Parameter Settings

This subsection introduces the parameter settings for the car-following models used in the microscopic traffic simulation. Both human-driven vehicles (HDVs) and connected and autonomous vehicles (CAVs) are modeled based on widely adopted driving behavior models. The following parts describe the model structures and corresponding parameter values in detail.

4.1.1. Human-Driven Vehicles

Currently, commonly used car-following models from a traffic engineering perspective [32] include the General Motors (GM) model [33] and the safe distance model [34]. From the perspective of statistical physics, typical models include the Intelligent Driver Model (IDM) [35] and the cellular automaton model [36].

Although the IDM model lacks stochasticity—meaning that a given input always produces a fixed output, which does not fully reflect real-world driving behavior—it is still chosen in this study as the base model for human-driven vehicles car-following behavior. This is because the IDM model is well-suited for use in dedicated autonomous driving lanes, where both leading and following vehicles are automated, and randomness is not required. Moreover, the IDM model is widely recognized for its simplicity, intuitive parameters, and ability to uniformly represent traffic states ranging from free flow to full congestion. The IDM model formula used in this study is as follows [37]:

where am is the maximum acceleration of the vehicle (m·s−2); v is the current speed of the following vehicle (m·s−1); v0 is the desired speed or free-flow speed of the vehicle (m·s−1); s is the longitudinal gap between the vehicle and its leader (m); s0 is the minimum standstill distance (m); T is the safe time headway (s); ∆v is the speed difference between the vehicle and the preceding vehicle (m·s−1); b is the comfortable (acceptable) deceleration rate for human drivers (m·s−2).

According to reference [37], the corresponding parameter values used in this model are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

IDM model parameters.

4.1.2. Connected and Autonomous Vehicles

In this study, the Cooperative Adaptive Cruise Control (CACC) model is selected as the fundamental model for describing the car-following behavior of CAVs. The model is defined by the following equation [38]:

where ek is the gap error of the k-th consecutive vehicle (m); xk−1 is the current position of the previous vehicle (m); xk is the current position of the target vehicle (in meters); thw is the gap time (s); vk is the speed of the target vehicle (m·s−1).

The formula for the vehicle speed in the k-th control cycle is:

where vkp is the speed of the target vehicle in the previous iteration (m·s−1); kp and kd are the coefficients for adjusting the time error relative to the preceding vehicle, with values of 0.45 and 0.25, respectively; dek is the derivative of ek.

4.2. Lane-Changing Model Parameter Settings

As shown in Figure 1, this study assumes that all CAVs switch to manual driving mode before executing a lane-changing maneuver, with the operation carried out manually by the driver. Since the road is an intelligent connected road, real-time information on both the vehicles and road conditions can be obtained, meeting the real-time information requirements of the LC2013 model. Moreover, the LC2013 model takes into account various factors such as vehicle speed, the speed of the following vehicle, and the traffic flow on the target lane. It also features simple parameter calibration and strong applicability. Therefore, in this study, both CAVs and HVs adopt the LC2013 lane-changing model.

To clarify, in this study, the statement that “autonomous vehicles switch to manual mode before changing lanes” does not imply a literal change of control from automation to a human driver. Instead, it refers to the use of human-like lane-changing parameters within SUMO to reflect more conservative behavior under mixed traffic conditions, as fully autonomous CAV lane-change models are not yet implemented in the LC2013 framework. This simplification is commonly used in CAV simulation studies to approximate transitional control behavior.

The main parameters of the LC2013 model are shown in Table 3. In the LC2013 model used in this study, human-driven vehicles (HVs) are not permitted to travel on the dedicated autonomous driving lane. Therefore, when the dedicated lane is positioned on the outermost side of the mainline, HVs merging from the ramp must exit the first lane as soon as possible within the buffer area. As a result, the lcStrategic parameter for HVs is set to 2, indicating that HVs aim to complete strategic lane changes early before reaching the dedicated lane. To prevent HVs from failing to change lanes in time and causing prolonged stops and traffic congestion, the lcCooperative parameter is set to 1, meaning HVs are willing to engage in cooperative lane-changing to avoid blockages due to long dwell times. Additionally, setting the lcSpeedGain parameter too high may lead to excessive lane-changing behavior, potentially reducing traffic efficiency. Therefore, the lcSpeedGain parameter for HVs is kept at the default value of 1.

Table 3.

The meaning and scope of the main parameters of LC2013 model.

CAVs, on the other hand, can travel on both dedicated and general-purpose lanes, and thus have a lower demand for strategic lane changes. Consequently, the lcStrategic parameter is set to the default value of 1. Since CAVs can access information about surrounding vehicles’ speeds, accelerations, and lane-changing intentions via vehicle-to-vehicle communication and onboard perception systems, they are capable of performing cooperative lane changes. Therefore, the lcCooperative parameter is set to 1. CAVs can maintain a relatively high average speed on the dedicated lane, so the lcSpeedGain parameter is set to 1.5, indicating that CAVs actively change lanes to enter the dedicated lane to achieve higher travel speeds.

In summary, the lane-changing model parameter settings for HVs and CAVs are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Model parameter setting for HV and CAV in LC2013.

5. Analysis and Discussion of Simulation Results

In this simulation, the total length of the highway is 1700 m, and the entrance ramp is located on the far-left lane in the direction of vehicle travel, Lane 1. Each simulation experiment runs for 6000 s with a simulation step length of 1 s. The first 600 s of each simulation are considered a warm-up period.

This study analyzes simulation results from both efficiency and safety perspectives to investigate the impact of acceleration lane length under different merging area configurations. Traffic efficiency is evaluated using two indicators: average vehicle speed and average delay. Traffic safety is assessed based on the number of conflicts, using TTC (Time to Collision) as the criterion for identifying traffic conflicts.

For human-driven vehicles (HVs), driver reaction time must be considered, as factors such as age, gender, and visual distraction [13] can affect the length of the reaction time. For connected and autonomous vehicles (CAVs), driver response is replaced by computer systems, with communication time substituting for human reaction time. Since communication time is typically shorter than human reaction time, the TTC threshold is set to 1.5 s for HVs and 0.5 s for CAVs.

First, the conclusions of this study align with the overall objectives of References [7,8], which seek to enhance road safety and efficiency through the implementation of dedicated lanes. However, our research reveals the complexity of this general principle at the critical node of merging areas. While studies such as [7,23] predominantly focus on basic segments of highways and generally recommend placing dedicated lanes in the innermost lane to maximize the benefits of continuous flow and high speed, our findings indicate that when dedicated lanes are set on the outer lane, a unique traffic phenomenon emerges in merging areas during peak hours—delays increase rather than decrease when acceleration lanes exceed 220 m in length. This contradicts expectations derived from studies on main roads, suggesting that the logic applied to main road configurations may not be directly applicable to merging areas. The reason lies in the fact that while outer dedicated lanes facilitate access, under high traffic demand, they become a “bottleneck area” where main road traffic and ramp traffic compete. Excessively long acceleration lanes may exacerbate the duration and scope of weaving conflicts, resonating profoundly with the emphasis on the importance of entrance area design highlighted in Reference [39].

Second, this study provides empirical support for the refined management and control advocated in References [13,19]. Reference [19] proposes management methods for dedicated lanes in mixed traffic flows, while Reference [13] approaches design from a network perspective. Our results demonstrate that in merging areas, relying solely on static, traditional traffic engineering optimization measures, such as “lengthening acceleration lanes,” yields limited and unstable benefits. This strongly argues that future optimization efforts should, as directed by Reference [19], shift toward dynamic and intelligent collaborative control strategies. For example, integrating vehicle-infrastructure coordination technologies to collaboratively guide vehicles in both dedicated and mixed lanes, rather than merely relying on the expansion of physical infrastructure.

Finally, this study clearly identifies the placement of dedicated lanes as a key moderating variable, representing an important supplement to existing research. As shown in References [9,10,23], existing discussions often recommend placing dedicated lanes on the inner side. However, by comparing inner and outer placement scenarios, our study reveals significant differences in their performance within merging areas. This confirms the foresight of Sun Ling et al. [23,39], who began to focus on placement issues, and deepens the discussion from “whether to implement” to “where to place and how to design accordingly.” Our conclusion asserts that, under constraints of limited road resources, especially in merging areas, decision-makers should not blindly adopt simplified solutions derived from main road studies (such as inner placement) or simply increase acceleration lane length. Instead, they must comprehensively consider traffic flow characteristics and the specific placement of dedicated lanes.

5.1. Impact of Acceleration Lane Length on Highway Efficiency Uner Different Merging Area Configurations

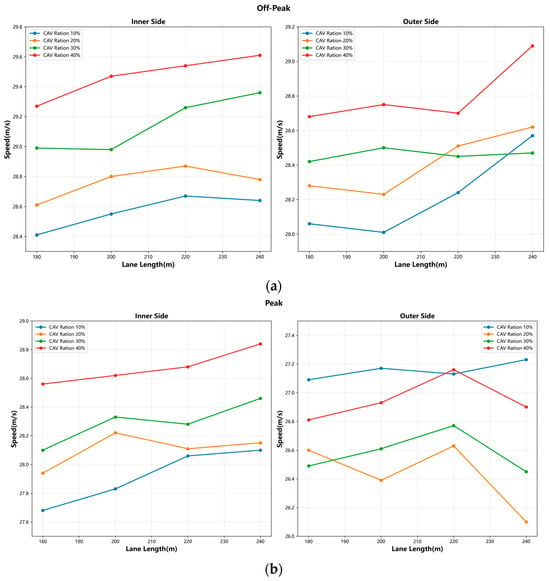

Figure 2 illustrates the impact of acceleration lane length on the average speed of vehicles within the highway system under various merging area configurations. Figure 2a illustrates the relationship between acceleration lane length and average vehicle speed during the off-peak period, when the dedicated lane is located on either the innermost or outermost side of the mainline, and the CAV penetration rates are 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40%. Figure 2b presents the corresponding scenarios during the peak period.

Figure 2.

Influence of acceleration lane length on average speed under different merging area schemes. (a) During Off-Peak Hours. (b) During Peak Hours.

From Figure 2, it can be observed that when the dedicated autonomous driving lane is located on the innermost side of the highway mainline, the average vehicle speed generally increases with the length of the acceleration lane under the same CAV penetration rate. However, the magnitude of this change is relatively small, and the average speed remains stable. During off-peak periods, the average speed ranges from approximately 28 m/s to 30 m/s, and during peak periods, it ranges from about 27 m/s to 29 m/s. For example, at a 30% CAV penetration rate during off-peak hours, increasing the acceleration lane length from 180 m to 240 m raises the average speed from 28.99 m/s to 29.36 m/s, an increase of only 1.28%. In peak periods, with more vehicles and increased traffic interference, the average speed is generally lower than during off-peak hours. At a 10% penetration rate where speed fluctuations are more pronounced across the four acceleration lane lengths, the average speed increases from 27.68 m/s to 28.10 m/s, a growth of only 1.52%. Therefore, when the dedicated lane is on the innermost side of the mainline, the acceleration lane length has little impact on average vehicle speed, with the maximum increase in average vehicle speed being only 1.52%.

When the dedicated lane is located on the outermost side of the mainline, the average vehicle speed under the same penetration rate generally shows an upward trend with increasing acceleration lane length. However, in some cases, such as with a 30% penetration rate during peak hours, the average speed fluctuates within the range of 26.45 m/s to 26.77 m/s as the acceleration lane length increases. Again, the average speed remains relatively stable, with only slight variations not exceeding 0.32 m/s.

Overall, the average vehicle speed tends to increase with the length of the acceleration lane in the highway merging area, but the impact is not significant. When the dedicated lane is on the outermost side, and the CAV penetration rate is relatively low, more HVs downstream of the ramp are forced to change lanes from Lane 1 (dedicated lane) to other lanes, negatively affecting overall traffic efficiency. In such cases, extending the acceleration lane length has limited effect. During off-peak periods, the maximum difference in average speed under the same penetration rate ranges from 0.28% to 2%, while during peak periods, it ranges from 0.52% to 1.52%.

There are several possible reasons why the impact of increasing the acceleration lane length is not significant. Firstly, autonomous vehicles generally possess more efficient acceleration and deceleration capabilities, allowing them to adapt more quickly to speed changes and thereby reduce the time spent on the acceleration lane. As a result, even with shorter acceleration lanes, autonomous vehicles can still effectively merge onto the mainline.

Secondly, highway traffic flow and speed distribution are also key factors influencing the effectiveness of acceleration lane length. In high-traffic conditions or when there are large speed differentials, extending the acceleration lane may help reduce vehicle interference and improve traffic smoothness. However, on dedicated autonomous driving lanes, enhanced communication and coordination capabilities among vehicles allow for smoother adjustments in speed and trajectory, reducing reliance on longer acceleration lanes.

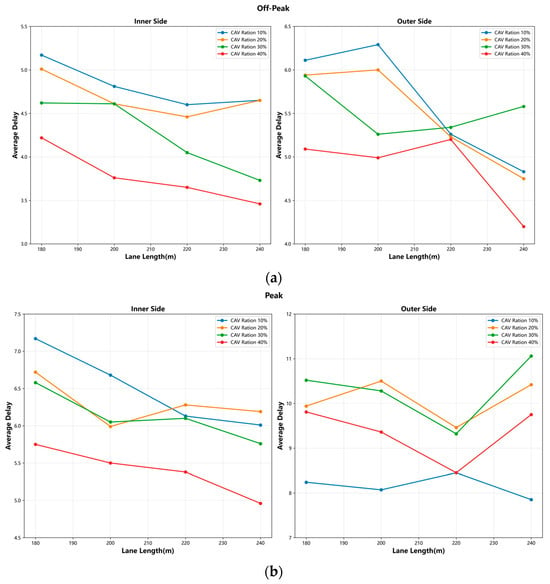

Figure 3 shows the impact of acceleration lane length on average vehicle delay on the highway under different merging area configurations. Figure 3a illustrates the relationship between acceleration lane length and average vehicle delay during the off-peak period, when the dedicated lane is located on either the innermost or outermost side of the mainline, and the CAV penetration rates are 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40%. Figure 3b presents the corresponding scenarios during the peak period.

Figure 3.

Influence of acceleration lane length on average vehicle delay under different confluence area schemes. (a) During Off-Peak Hours. (b) During Peak Hours.

From Figure 3, it is evident that average vehicle delay is significantly affected by traffic volume—delays are lower during off-peak periods and higher during peak periods. When the dedicated autonomous driving lane is on the innermost side of the mainline, under the same CAV penetration rate, average vehicle delay generally decreases as the acceleration lane length increases. However, during off-peak periods and with 10% or 20% penetration, average delay increases once the acceleration lane length exceeds 220 m. In these conditions, the minimum delay during off-peak periods is reduced by 0.55 s to 0.89 s compared to the maximum delay, and during peak periods, it is reduced by 0.73 s to 1.16 s.

When the dedicated lane is positioned on the outermost side of the highway, vehicles entering from the ramp must merge directly into the dedicated CAV lane. Human-driven vehicles then need to perform mandatory lane changes to exit the dedicated lane within the buffer zone. This creates a cascade of discretionary lane changes as downstream human drivers react to vehicles changing lanes ahead of them. Additionally, the outermost lane experiences higher interaction frequency with ramp vehicles and is closer to roadside obstacles and edge effects, creating more speed heterogeneity in the traffic stream. These behavioral dynamics explain the higher conflict rates and lower operational efficiency observed in the outermost dedicated lane configuration. Additionally, due to the randomness of traffic, the trend in average delay becomes more erratic. Particularly during peak periods, the average delay is significantly higher than during off-peak hours. In these conditions, the minimum delay during off-peak periods is reduced by 0.67 s to 1.46 s compared to the maximum delay, and during peak periods, the reduction ranges from 0.39 s to 1.74 s.

In summary, variations in the length of the acceleration lane in the merging area of the highway have a noticeable impact on average vehicle delay, with the range of change in delay being 0.39 s to 1.74 s as the acceleration lane length increases.

According to the analysis above, at the same CAV penetration rate, both average vehicle speed and average delay generally show improving trends as acceleration lane length increases. However, when the CAV penetration rate is 10% or 20% and the dedicated lane is on the inner side of the mainline, increasing the acceleration lane length beyond 220 m does not lead to further improvement in average speed and even results in higher delays during off-peak periods. This may be due to the fact that, under low penetration rates, extending the acceleration lane invites more human-driven vehicles to engage in lane-changing maneuvers, which increases delays while failing to significantly boost vehicle speeds.

5.2. Impact of Acceleration Lane Length on the Safety of Dedicated Lane Highways Under Different Merging Area Configurations

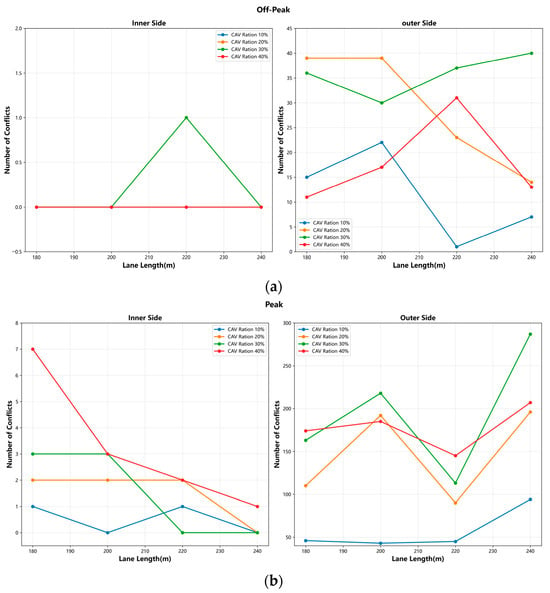

Figure 4 illustrates the impact of acceleration lane length on the number of vehicle conflicts on highways under different merging area configurations. Specifically, Figure 4a illustrates the relationship between acceleration lane length and the number of conflicts during the off-peak period, when the dedicated lane is located on either the innermost or outermost side of the mainline, and the CAV penetration rates are 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40%. Figure 4b presents the corresponding scenarios during the peak period.

Figure 4.

Influence of acceleration lane length on average vehicle conflicts under different confluence area schemes. (a) During Off-Peak Hours. (b) During Peak Hours.

From Figure 4, it can be observed that during off-peak periods, when the autonomous driving dedicated lane is positioned on the innermost side of the highway, the number of vehicle conflicts ranges from 0 to 1. When the dedicated lane is on the outermost side, the number of conflicts ranges from 0 to 7. During peak periods, conflicts increase significantly: the number of conflicts ranges from 1 to 40 when the dedicated lane is on the innermost side, and from 43 to 287 when it is on the outermost side. The surge in conflicts during peak periods can be attributed to increased traffic interference and greater randomness in traffic flow.

When the autonomous driving dedicated lane is on the innermost side of the highway, the probability of traffic conflicts is very low—almost no conflicts occur during off-peak hours, and during peak hours, conflicts remain within 0 to 7. Moreover, with CAV penetration rates of 20%, 30%, and 40%, the number of vehicle conflicts decreases as the acceleration lane length increases.

In contrast, when the dedicated lane is on the outermost side, more HVs merging from the on-ramp need to perform mandatory lane changes, increasing the randomness of the mixed traffic flow. This may be due to the fact that the outer lane is typically closer to the road edge and entrances/exits, which raises the risk of conflict with other vehicles or obstacles. When autonomous vehicles need to merge into or exit the mainline, they may have to adjust their trajectory and speed more frequently, thereby increasing the likelihood of conflicts with other vehicles.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the impact of acceleration lane length on traffic efficiency and safety in highway merging areas, considering two different positions for dedicated Connected and Autonomous Vehicle (CAV) lanes (innermost vs. outermost). Through a comprehensive simulation analysis using SUMO under various traffic volumes and CAV penetration rates, the following key conclusions can be drawn:

- (1)

- Limited Impact on Traffic Efficiency: Increasing the length of the acceleration lane in highway merging areas has a limited effect on improving overall traffic efficiency. While a general trend of increasing average speed and decreasing average delay was observed with longer acceleration lanes, the magnitude of these improvements was marginal. The maximum increase in average speed ranged from only 0.28% to 2% during off-peak periods and 0.52% to 1.52% during peak periods. Similarly, the reduction in average delay was confined to a range of 0.39 s to 1.74 s.

- (2)

- Superiority of Innermost Lane Placement: The positioning of the dedicated CAV lane has a more pronounced effect on traffic performance than the acceleration lane length. Setting the dedicated lane on the innermost side of the mainline consistently resulted in better traffic efficiency (higher average speeds and lower delays) and significantly enhanced safety (fewer vehicle conflicts) compared to the outermost placement. The outermost lane configuration induced more mandatory lane-changing maneuvers for human-driven vehicles, leading to increased traffic turbulence and conflict points, especially during peak periods.

- (3)

- Distinct Safety Outcomes: From a safety perspective, the innermost dedicated lane configuration demonstrated a clear advantage, maintaining a low number of vehicle conflicts (0–7 during peak hours) that decreased with longer acceleration lanes at higher CAV penetration rates. In contrast, the outermost lane configuration led to a substantially higher number of conflicts (43–287 during peak hours), as it placed merging and lane-changing activities in a more complex and high-interaction zone.

In summary, the findings of this study suggest that under mixed traffic flow conditions with dedicated CAV lanes, the strategic placement of the dedicated lane is a more critical factor than the extension of the acceleration lane length. Specifically, an innermost dedicated lane configuration yields superior overall performance. Therefore, within the constraints of limited roadway resources, investing in longer acceleration lanes is not a recommended strategy for significantly enhancing traffic efficiency or safety. The resources required for such extensions could be more effectively allocated to optimizing the lateral position of dedicated lanes and implementing supportive intelligent systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and L.L.; methodology, J.L. and L.L.; software, J.L.; validation, J.L., H.W. and X.Q.; formal analysis, J.L. and P.M.; investigation, J.L. and Y.G.; resources, X.Q.; data curation, Y.G. and P.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, L.L., Y.G. and H.W.; visualization, Y.G. and X.Q.; supervision, L.L.; project administration, L.L.; funding acquisition, L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Shandong Provincial Key Research and Development Program (SPKR&DP) [2020CXGC010118] (received from the government of Shandong Province), and Science and Technology Program Project of Shandong Provincial Department of Transportation [2020BZ01-05, 2020BZ01-06] (received from Shandong Hi-Speed Group).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Although the study received funding from Shandong Hi-Speed Group, and the funder was involved in the topic selection, the company had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Ma, S.-H.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Yue, M.; Yang, L.; Yang, T. Theoretical Study and Practical Exploration of Modernization of Expressway Construction Management. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. 2022, 39, 239–246. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.-Q.; Wang, L.; Wang, W. Empirical Highway Capacity Model of On-Ramp Junction. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2004, 4, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.-S.; Hao, H.-J.; Yao, Z. Stability Analysis and Fundamental Diagram Analysis of Road Sections of Heterogeneous Traffic Flow Mixed with Connected Automated Vehicles. Ind. Eng. 2022, 25, 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Z.; Tian, C.; Guo, Y.; Wang, X. The Key Technology and Development of Intelligent and Connected Transportation System. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2020, 42, 2–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, R.; Fan, H.; Zhao, X.; Yuan, S. Research and Simulation of Vehicle Cooperative Guidance Strategy on Connected and Signalized Intersections under Mixed Traffic Environment. Automob. Technol. 2021, 553, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rad, S.R.; Farah, H.; Taale, H.; van Arem, B.; Hoogendoorn, S.P. Design and Operation of Dedicated Lanes for Connected and Automated Vehicles on Motorways: A Conceptual Framework and Research Agenda. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 117, 102664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aty, M.; Wu, Y.; Saad, M.; Rahman, S. Safety and Operational Impact of Connected Vehicles’ Lane Configuration on Freeway Facilities with Managed Lanes. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 144, 105616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebpour, A.; Mahmassani, H.S.; Elfar, A. Investigating the Effects of Reserved Lanes for Autonomous Vehicles on Congestion and Travel Time Reliability. Transp. Res. Rec. 2017, 2622, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R. Study on Traffic Management of Autonomous Vehicles. Ph.D. Thesis, People’s Public Security University of China, Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. Research on System Control Strategy of CAV in Mixed Traffic Flow under Network Connected Environment. Ph.D. Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Ding, H.; Ding, H.; Di, Y.; Liu, J. CAV-dedicated lane sharing strategy of expressway in mixed traffic environment: A novel dynamic lane-level tolling method. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2025, 199, 104567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Luo, Q.; He, Z. Management and Control Method of Dedicated Lanes for Mixed Traffic Flows with Connected and Automated Vehicles. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2023, 23, 221–231. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.; Zhang, X.; Shi, H. The Connected Autonomous Vehicle Dedicated Lane Network Design. J. Chongqing Norm. Univ. Nat. Sci. 2023, 40, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Long, W.; Wang, W.; Jin, K. System-Level Evaluation of Autonomous Vehicle Lane Deployment Strategies Under Mixed Traffic Flow. Systems 2025, 13, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Li, L.; Shi, H.; Rui, Y.; Ngoduy, D.; Ran, B. Integrated driving risk surrogate model and car-following behavior for freeway risk assessment. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 201, 107571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zeng, Y.; Gao, Y.; Rong, J.; Xiao, Y. Modeling of car-following behavior at signalized intersection considering vehicle-vehicle and vehicle-road interactions. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2025, 678, 130970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhou, B.; Xu, M. Analysis and improvement of car-following stability for connected automated vehicles with multiple information uncertainties. Appl. Math. Modell. 2023, 123, 790–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zheng, N.; Wang, H. Cooperative control method for connected and automated vehicle platoon based on arbitrary time headway switched system. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2025, 180, 105353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Liu, M.; Hao, W. Energy-optimal car-following model for connected automated vehicles considering traffic flow stability. Energy 2024, 298, 131333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Yang, X.; Mu, C.; Zhu, S. Influence Factors and Model Selection for Conflict Risk in Different Car-Following Behaviors: Insights from Automated and Human-Driven Vehicles. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2026, 224, 108286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Luo, Z.; Wang, H. Capacity improvement for mixed traffic flow by installing vehicle-to-vehicle devices on partial human-driven vehicles to serve connected automated vehicles. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2025, 2025, 130763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenju, D.; Zhekai, H.; Shukai, L.; Jiangang, Z. Fundamental diagram and stability analysis of mixed traffic flow considering platoon intensity and multiclass time delay. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2025, 2025, 130847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Song, X.; Yang, F.; Li, Y. Setting Position of Automatic Driving Lane on Six-Lane Expressway. Highway 2022, 67, 261–267. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Song, X.; Liu, B.; Liu, J.; Gao, H.; Liang, Y. A dynamic lane-changing driving strategy for CAV in diverging areas based on MPC system. Sensor 2023, 23, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, M.; Jiang, X. Dynamic Control Method for CAV-Shared Lanes at Intersections in Mixed Traffic Flow. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Yu, B.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Dai, Z.; Gao, K. Meta-MSCC: A foundation model for adaptive CAV control in highway weaving segments. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2025, 181, 105397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hang, P.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J. A cooperative decision-making method for CAVs from the perspective of opinion dynamics. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2026, 182, 105412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Shangguan, W.; Chen, J.; Peng, C.; Arman, M.A.; Cai, B.; Tampére, C.M. Two-stage adaptive CAV control for mitigating congestion in mixed traffic environments using front-tracking method. Expert Syst. Appl. 2026, 296, 129013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Xiao, D.; Tu, R.; Ma, W.; Zheng, N. Assessing the impact of passenger compliance behavior in CAVs on environmental benefits. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 133, 104278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Yamamoto, T. Impact of Dedicated Lanes for Connected and Autonomous Vehicles on Traffic Flow Throughput. Physica A 2018, 512, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. Design Specification for Highway Alignment: JTG D20-2017; China Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Jin, S. Review and Outlook of Modeling of Car Following Behavior. China J. Highw. Transp. 2012, 25, 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Gazis, D.C.; Herman, R.; Rothery, R.W. Nonlinear Follow-the-Leader Models of Traffic Flow. Oper. Res. 1961, 9, 545–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kometa, N.; Sasaki, T. Dynamic Behavior of Traffic with a Nonlinear Spacing-Speed Relationship. In Dynamic Behavior of Traffic; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 1959; pp. 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Treiber, M.; Hennecke, A.; Helbing, D. Congested Traffic States in Empirical Observations and Microscopic Simulations. Phys. Rev. E 2000, 62, 1805–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfram, S. A New Kind of Science; Wolfram Media: Champaign, IL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.; Wang, H.; Ran, B. Car-Following Modeling for CACC Vehicles and Mixed Traffic Flow Analysis. J. Transp. Syst. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2018, 18, 6–14. [Google Scholar]

- Milanés, V.; Shladover, S.E. Modeling Cooperative and Autonomous Adaptive Cruise Control Dynamic Responses Using Experimental Data. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2014, 48, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, A. Design of Entrance Area of Automatic Driving Special Lane in Vehicle-Infrastructure Collaborative Environment. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. 2020, 37, 122–129. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).