1. Introduction

Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) is a non-destructive testing technology widely employed for the inspection and evaluation of asphalt pavement structures [

1,

2]. Its operational principle is primarily based on the propagation velocity and reflection characteristics of electromagnetic waves in materials with different dielectric properties [

3,

4,

5]. The dielectric properties of asphalt pavement structural materials refer to their polarization behavior under electromagnetic fields, which directly governs the propagation of electromagnetic waves, including reflection, transmission, scattering, energy attenuation, and wave speed [

6,

7]. These properties consequently influence the performance of GPR systems in terms of detection depth and resolution [

8,

9].

Different types of asphalt pavement structural layers, such as asphalt mixture surface courses, cement-stabilized aggregate base layers, and soil subgrades, exhibit distinct dielectric characteristics [

10]. These differences enable the identification of layer boundaries and internal defects by analyzing variations in the intensity and timing of GPR reflected signals [

11]. In particular, when concealed distresses such as moisture accumulation, internal cracks, or loosening occur within the pavement structure, the dielectric properties undergo significant changes. These anomalies cause abnormal reflection or attenuation of GPR electromagnetic waves, resulting in distinctive signal features in the radar image [

12]. For instance, moisture infiltration increases the dielectric constant of the material, enhancing the reflection signal intensity in the corresponding region of the GPR profile [

13]. Conversely, internal cracks or voids form distinct low-permittivity zones, generating strong reflection or diffraction patterns. By comparing the dielectric properties across different structural layers and incorporating advanced target detection algorithms and models, it becomes possible to accurately locate structural damage and assess the health condition of the pavement [

14]. Therefore, the variation in dielectric properties among asphalt pavement structural materials leads to differences in electromagnetic wave reflection behavior, forming the fundamental basis for the effective application of GPR in evaluating construction quality and identifying concealed distress. In-depth research on these dielectric properties is of significant importance for improving the accuracy and reliability of GPR-based pavement inspection.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the dielectric properties of asphalt pavement layer materials are closely related to the dielectric characteristics and volume fractions of their components, as well as other factors such as electromagnetic wave frequency, moisture content, and environmental temperature [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Dielectric mixing models have been established as an effective approach for characterizing these properties, providing a theoretical bridge between the overall dielectric behavior of the mixture and the volumetric proportions of its constituents. Such models aim to interpret and predict the dielectric properties of asphalt pavement layers under varying environmental conditions [

20,

21,

22].

Research on asphalt surface layers has shown that the relative permittivity of asphalt mixtures exhibits a positive correlation with both air void content and moisture content. Based on data obtained from field cores or laboratory specimens, including asphalt content, bulk specific gravity, air voids, moisture content, and dielectric constant, several empirical models have been developed via regression analysis. These include univariate linear [

23,

24], multivariate linear [

25], cubic polynomial [

26], and exponential [

27] relationships that link the relative permittivity of asphalt mixture to factors such as air void content, degree of compaction, asphalt content, or moisture content. Furthermore, advanced computational methods such as extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) combined with genetic algorithms have been employed to rapidly estimate and evaluate the compaction quality of asphalt layers using component volume fractions and their dielectric parameters as inputs [

28].

Dielectric mixing formulas commonly used in composite materials and electrochemistry, such as the Complex Refractive Index, Rayleigh, and Böttcher models, have been extended to describe the multi-phase discrete system of asphalt pavement layers [

29]. These classical dielectric mixing models establish a relationship between the overall dielectric properties of asphalt mixtures and those of their constituent phases, effectively characterizing the quantitative correlation between the bulk dielectric behavior and the phase components. They have also been applied to predict volumetric properties such as the compaction degree of asphalt pavements [

30,

31,

32].

The Complex Refractive Index Dielectric Mixing Model, derived from the L–R equation with a polarization parameter of 0.5, states that the square root of the overall dielectric constant of the asphalt mixture equals the sum of the products of the volume fraction and the square root of the dielectric constant of each constituent phase [

33]. The Rayleigh and Böttcher dielectric models, both rooted in electromagnetic mixing theory, treat the asphalt mixture as a composite of a background medium and scatterers [

34]. The Rayleigh model assumes that the scatterers are spherical and much smaller than the wavelength of the electromagnetic wave, and it neglects mutual polarization between scatterers, making it suitable for describing small spherical particles dispersed in a uniform medium. The Böttcher model extends the Rayleigh approach by incorporating a fixed polarization interaction term among scatterers.

In reality, the scatterers in asphalt mixtures are not spherical. To account for variations in scatterer shape, the CP [

35] and ALL [

33] dielectric mixing models were developed by introducing optimized shape parameters into the original Rayleigh or Böttcher frameworks. Since asphalt pavement layers are relatively dense and the scatterers are interlocked in a complex manner, the polarization interaction coefficient is likely to vary across different structural layers. Accordingly, further refinements to the Böttcher model have been made by optimizing the polarization coefficient for scatterers [

36].

A variety of methods are available for measuring the dielectric properties of asphalt pavements, including the capacitance method and GPR electromagnetic wave technique, each with distinct testing conditions and characteristics constrained by laboratory or field environments. While statistical regression models linking dielectric properties to volumetric indicators have been proposed, they are typically based on limited and specific sample data, resulting in non-generalizable and highly variable functional forms. In contrast, dielectric mixing theoretical models incorporate both the dielectric and volumetric parameters of each component into explicit mathematical expressions, offering stronger applicability. Nevertheless, the assumptions regarding scatterer properties in these theoretical models still deviate significantly from the actual conditions in compacted asphalt mixtures. Moreover, a systematic integration of environmental and compositional factors into a unified predictive framework is still lacking.

To address these gaps, this paper aims to systematically investigate the environmental impacts and compositional elements affecting dielectric characteristics of asphalt mixtures. The primary objectives are to critically analyze the key determinants of dielectric behavior, develop a more robust characterization framework that integrates both environmental and compositional factors, and bridge the gap between theoretical predictions and practical measurements. The following sections detail the materials and methods employed in this study, present the results of the dielectric measurements under different scenarios, and discuss the implications of the findings for pavement evaluation using GPR technology.

2. Testing Equipment for the Dielectric Property of Asphalt Mixture

The GSSI air-coupled ground penetrating radar (GPR) system consists of data acquisition software on a laptop, an SIR-20 control unit, and a 2 GHz center frequency air-coupled antenna, as shown in

Figure 1a. The acquisition parameters are set to an 8 ns time window, a scanning rate of 100 scans per second, 512 samples per scan, a pulse repetition frequency of 400 KHz, and a continuous measurement mode triggered by time. Gain adjustments are uniformly made to ensure that the single-channel reflected waveform does not experience clipping.

The dimensions of the laboratory-fabricated slab specimens (300 × 300 × 50 mm) were determined to be sufficient for reliable GPR measurements using the 2 GHz center-frequency air-coupled antenna. The planar extent exceeds the antenna footprint and near-field influence zone, while the thickness provides adequate wave propagation distance for stable dielectric constant determination without significant boundary effects.

The GPR antenna is rigidly mounted at a fixed height of 20 cm above the asphalt mixture (AC-13) slab specimen, with the test specimen positioned on a metal plate. The metal plate enhances the amplitude of the reflection signal from the bottom of the specimen, making it easier to accurately determine the two-way travel time of the bottom reflections, as shown in

Figure 2. In the GPR grayscale image of the asphalt mixture slab specimen (as illustrated in the rightmost subplot of

Figure 3), distinct horizontal high-amplitude coherent axes are observed, corresponding to: (1) the direct wave between transmitting/receiving antennas, (2) reflections from the specimen’s top and bottom surfaces, and (3) multiples generated by the metal plate. From these, the two-way travel times corresponding to the reflection waves from the specimen’s top and bottom surfaces, denoted as

t0 and

t1 respectively, as well as the amplitude value at the top surface of the specimen, are systematically extracted for the following analysis.

The relative permittivity (

εAC) of the asphalt mixture specimen is determined through both approaches: (i) the reflection coefficient method (RCM, Equation (1)) based on amplitude analysis of electromagnetic wave reflections at the air-specimen interface, and (ii) the thickness inversion algorithm (TIA, Equation (2)) derived from precise two-way travel time measurements between the top (air-specimen) and bottom (specimen-metal plate) interfaces in the GPR trace.

where

εAC represents the relative permittivity of the asphalt mixture (dimensionless).

Aₚ is the incident wave amplitude under total reflection (V/m), obtained by directing the GPR antenna toward a metal plate in free space, as shown in

Figure 2b.

A0 denotes the reflected wave amplitude from the top surface of the asphalt mixture slab specimen (V/m).

v and

c0 are the propagation velocities of the electromagnetic wave in the asphalt mixture specimen and vacuum (m/ns), respectively, with

c0 taken as 0.3 (m/ns). Δ

t is the two-way travel time difference (

t1 −

t0) of the electromagnetic wave traveling through the specimen (ns).

d is the thickness of asphalt mixture slab specimen (m).

3. Basic Properties of Raw Materials for Asphalt Mixture

The aggregates and filler used in the asphalt mixtures were derived from limestone, with fundamental properties of coarse aggregate, fine aggregate, and mineral filler detailed in

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3. All tested parameters strictly complied with specification requirements: the coarse aggregate exhibited excellent mechanical properties with crushing value (18.3%), Los Angeles abrasion loss (16.5%), and flakiness and elongation index (8.2%) all below specification limits, ensuring enhanced particle interlocking and long-term resistance to mechanical degradation. The fine aggregate demonstrated superior surface characteristics with sand equivalent (63.8%) and angularity (34 s) exceeding minimum requirements, indicating low clay content and favorable internal friction properties. The mineral filler showed optimal physicochemical performance with water content (0.11%) and hydrophilic coefficient (0.72) below threshold values, preventing moisture damage and ensuring compatibility with asphalt binder.

The 90# base asphalt was used throughout the study, with key performance indicators summarized in

Table 4. The binder met all specification requirements, exhibiting a penetration of 87 dmm at 25 °C, softening point of 46.0 °C, ductility greater than 100 cm at 15 °C, and relative density of 1.011. These properties collectively ensure appropriate stiffness-temperature susceptibility, high-temperature stability, flexibility under stress, and material consistency. The conformity of all material parameters guarantees structural integrity, moisture resistance, workability during compaction, and long-term durability under thermal and traffic loading conditions.

The aggregate gradation for the asphalt mixture was designed in accordance with the median values of the AC-13 grading range specified in the applicable technical specifications. The resulting gradation curve is presented in

Figure 3. Through Marshall mix design methodology, the optimum asphalt content was determined to be 4.49%.

The selection of the median AC-13 gradation plays a critical role in achieving a dense and well-interlocked aggregate skeleton, which enhances the mixture’s resistance to permanent deformation and improves overall stability. Meanwhile, the optimum asphalt content ensures adequate coating of aggregates while providing sufficient bonding strength and durability. This carefully calibrated combination of gradation and asphalt content guarantees optimal performance characteristics, including balanced stiffness-flexibility properties, improved fatigue resistance, and enhanced moisture damage resistance, ultimately contributing to the long-term service life of the asphalt pavement under varying traffic and environmental conditions.

4. Environmental Factors on the Dielectric Property of Asphalt Mixture

4.1. Dry Asphalt Mixture

AC-13 asphalt mixture slab specimens (mold inner dimensions: 300 × 300 × 50 mm) were fabricated using a roller compaction method. Five distinct compaction levels were achieved by varying the number of roller passes. For each compaction level, three parallel specimens were prepared.

Table 5 summarizes the volumetric parameters (bulk specific gravity, air void content) and GPR measured parameters (two-way travel time, reflection amplitude) for each group. To enhance data reliability, the average value of the three specimens under the same compaction effort (number of roller passes) was adopted as the final representative value for that compaction level.

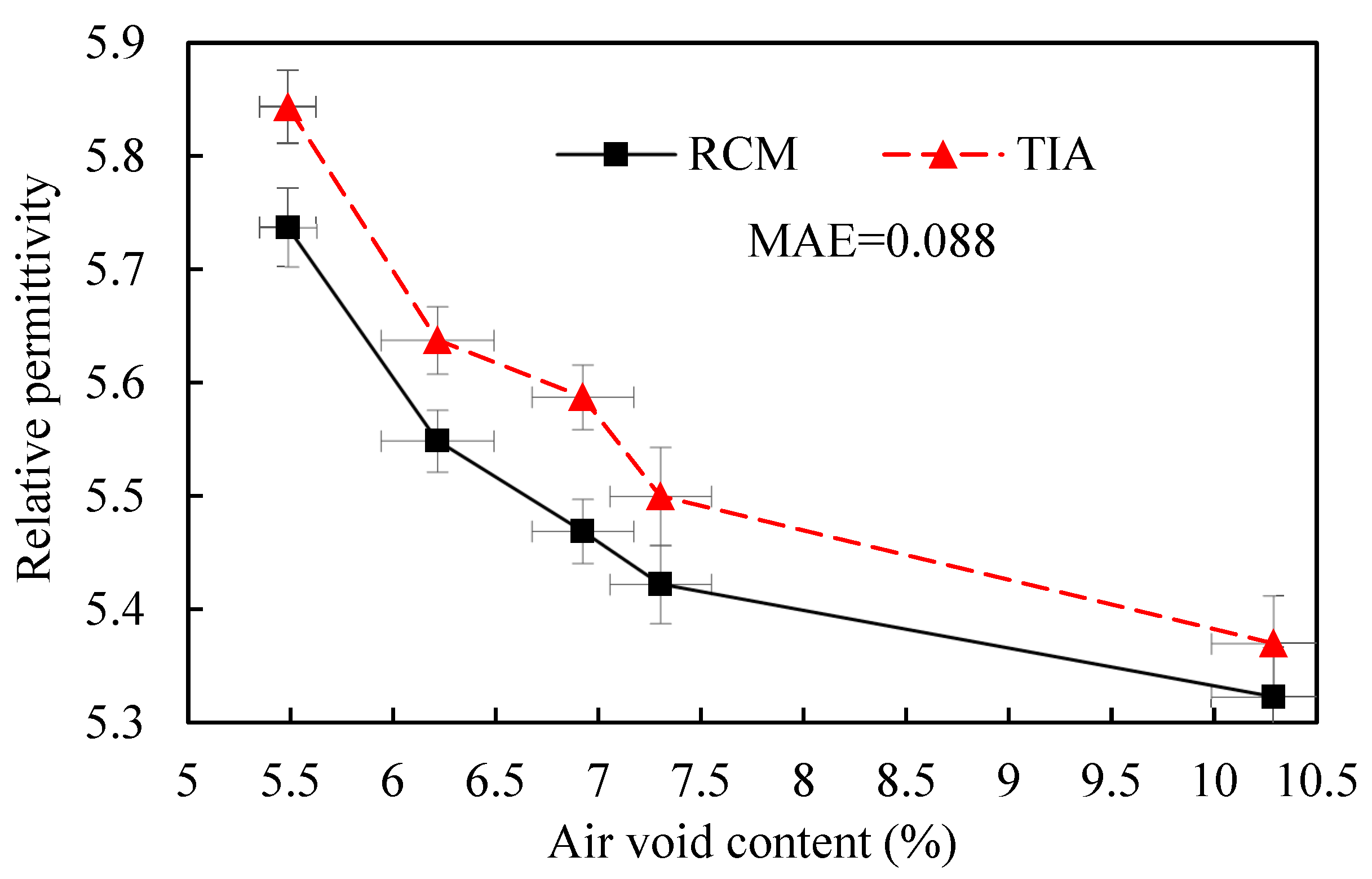

As shown in

Figure 4, the relative permittivity of the dry asphalt mixture exhibits a significant negative correlation with air void content. Compared to the thickness inversion algorithm (TIA), the reflection coefficient method (RCM) yields slightly lower relative permittivity values. However, the mean absolute error (MAE = 0.088) is less than 0.1, indicating that the reflection coefficient method can still accurately determine the relative permittivity of dry asphalt mixtures. Furthermore, a positive correlation is observed between the relative permittivity of the AC-13 slab specimens and the reflection amplitude (

A0) at the slab surface; higher permittivity corresponds to greater reflected wave energy at the material interface.

The experimental data demonstrate a clear positive correlation between the relative permittivity of AC-13 asphalt mixture and its bulk specific gravity. This relationship can be attributed to the increased density of the aggregate-asphalt interface and reduced porosity with higher compaction, which enhances the polarization capability of the mixture. This coupling between dielectric and volumetric parameters provides a theoretical basis for non-destructive compaction assessment using GPR. Subsequent analysis will focus on quantifying the functional relationship between relative permittivity and air void content.

To ensure comparability, all subsequent tests were conducted on asphalt concrete slabs compacted with a fixed number of roller passes (16), thereby eliminating variability in fabrication technology affecting the dielectric test results.

4.2. Asphalt Mixture with Surface Water and Ice

Uniform water volumes of 50, 100, 150, and 200 mL were sprayed onto the surface of the asphalt mixture slab, as illustrated in

Figure 5a. This process progressively transformed the surface condition from moist to ponded, with corresponding average water film thicknesses of 0.56, 1.11, 1.67, and 2.22 mm. It should be noted that at higher spray volumes, non-uniform water film distribution was observed. This experimental setup approximates field conditions during roller compaction of loose asphalt mixtures, where water sprayed onto roller wheels can lead to varying surface wetness or localized ponding on the pavement.

Figure 6 illustrates the relationship between the relative permittivity of the asphalt mixture, calculated using both the reflection coefficient method (RCM) and thickness inversion algorithm (TIA), and the average water film thickness. Both methods show an increase in relative permittivity with increasing water film thickness, with the RCM exhibiting a more pronounced response. This behavior is attributed to the high relative permittivity of water (

ε ≈ 81 at 20 °C), which significantly exceeds that of dry asphalt mixtures. The presence of a surface water film amplifies the dielectric contrast at the air-slab interface, thereby enhancing the reflected wave amplitude (

A0).

Despite the increasing water film thickness, the maximum average thickness remained below 2.3 mm, resulting in a negligible increase in the overall slab thickness (including the water film). However, the high-permittivity water film considerably prolongs the wave propagation time from the water film surface to the slab bottom compared to the low-permittivity asphalt mixture. Consequently, the TIA-derived relative permittivity increases only gradually with spray volume, as this method primarily relies on travel time differences and is less sensitive to surface dielectric changes than the amplitude-based RCM.

In

Figure 6, an exponential curve fit was applied to the relationship between the relative permittivity (

y) of asphalt mixture measured by the RCM and the water film thickness (

x). The resulting exponential relationship is expressed as:

y = 5.1988 e

0.9526x, with a coefficient of determination

R2 = 0.9993. When extrapolating to zero water film thickness (x = 0), the fitted model predicts a dry-state relative permittivity of 5.1988, which deviates from the measured dry-state value of 5.55 by 0.3512. Thus, this exponential relationship can be preliminarily used to estimate the true relative permittivity of dry asphalt pavement, or conversely, to infer the thickness of the surface water film based on the measured permittivity.

Surface water conditions significantly influence dielectric measurements, particularly for methods based on interface reflection amplitudes. These findings highlight the importance of accounting for surface moisture conditions in non-destructive pavement evaluation using GPR, especially when applying amplitude-dependent analysis methods. The experimental results provide critical insights for distinguishing moisture effects from material properties in field GPR data interpretation.

Controlled volumes of water (50, 100, 150, and 200 mL) were uniformly sprayed onto the asphalt mixture slab surface and rapidly frozen to form ice films, as shown in

Figure 5b. The resulting average ice film thicknesses were 0.56, 1.11, 1.67, and 2.22 mm, respectively. At higher spray volumes, uneven ice film formation was observed, realistically simulating the inhomogeneous ice layer formation on pavement surfaces under winter weather conditions.

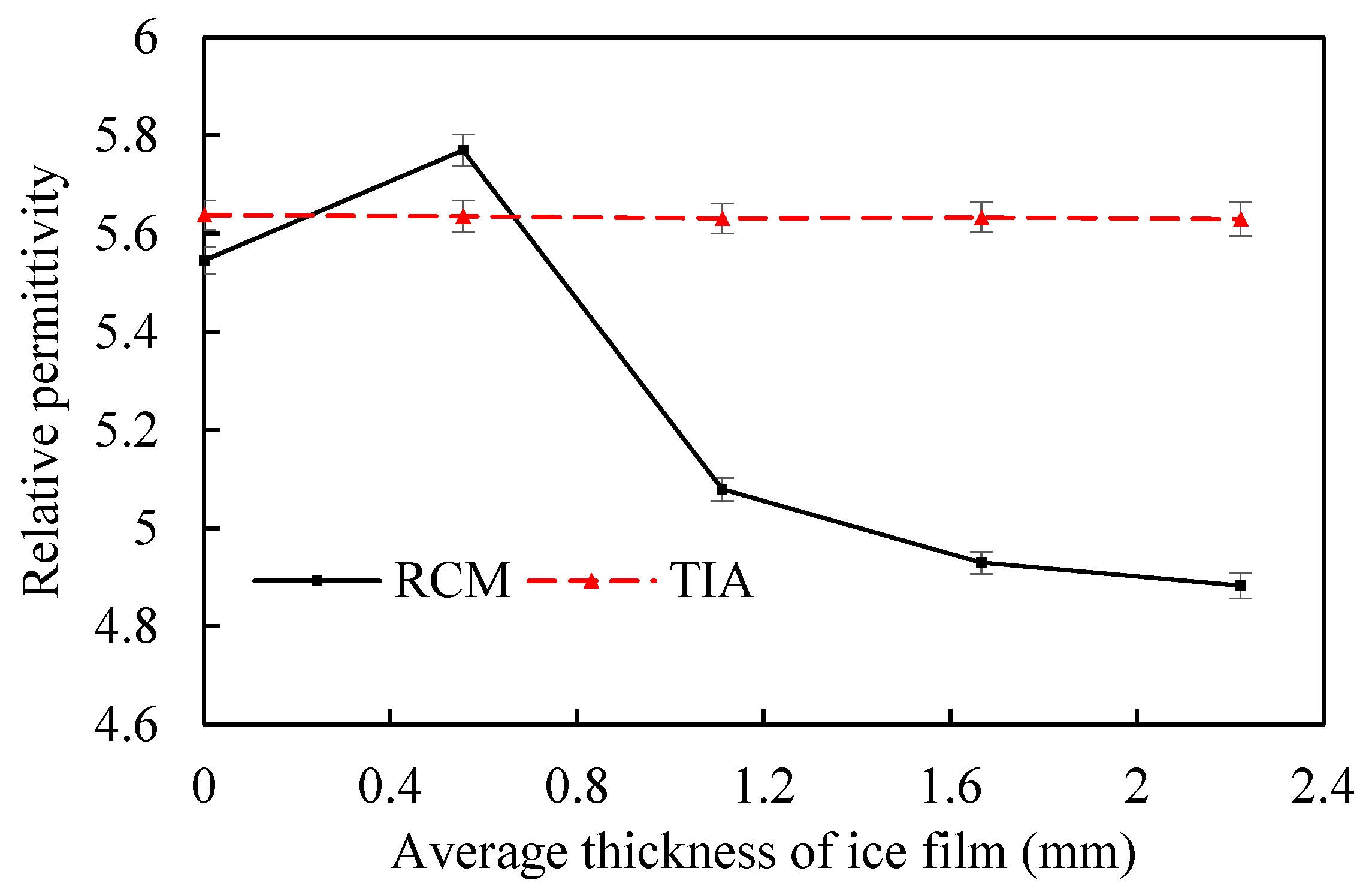

Figure 7 presents the relationship between the relative permittivity of the asphalt mixture, determined by both the reflection coefficient method (RCM) and thickness inversion algorithm (TIA), and the average ice film thickness. The RCM-derived relative permittivity initially increases then decreases with increasing ice film thickness. This nonlinear behavior can be attributed to two competing mechanisms: initial wave superposition between reflections from the ice surface and slab surface enhances the composite reflection amplitude, while subsequently, the low permittivity of ice (ε ≈ 2~3) reduces the dielectric contrast at the air-ice interface, thereby diminishing reflection amplitude.

The TIA-calculated relative permittivity remains essentially constant across all ice film thicknesses. This stability results from multiple factors: the limited ice film thickness (<2.3 mm) causes negligible change in overall slab thickness, while the similar electromagnetic wave velocities in ice and air minimize alterations in two-way travel time (variations < 10−5 ns). Furthermore, the time resolution of the 2 GHz center-frequency GPR system is insufficient to detect such minute travel time differences.

The distinct responses of the two methods underscore fundamental differences in their underlying physical principles. The amplitude-based RCM proves sensitive to interfacial dielectric variations caused by ice films, whereas the travel-time-based TIA remains ineffective for detecting thin ice layers due to equipment resolution constraints. These findings highlight the critical importance of selecting appropriate GPR analysis methods for winter pavement condition assessment.

4.3. Asphalt Mixture Saturated with Water and Ice

The asphalt mixture slab (with an air void content of 6.21%) was immersed in water for 24 h to achieve full saturation. GPR measurements were first performed on the saturated surface-dry specimen to determine its relative permittivity. The saturated slab was then rapidly frozen, and measurements were repeated after complete ice formation. The results are summarized in

Figure 8, which compares the relative permittivity values obtained by the reflection coefficient method (RCM) and thickness inversion algorithm (TIA) for three physical states: dry, water-saturated, and ice-saturated.

Compared to the dry condition, the relative permittivity of the water-saturated slab increased by 0.43 (RCM) and 0.66 (TIA). This rise is attributed to the replacement of air voids (ε ≈ 1) with water (ε ≈ 81 at 20 °C), which enhances the overall polarization capability of the mixture. Although the saturated surface-dry specimen exhibited a thin water film on its surface, the average film thickness was less than 0.56 mm (the thickness achieved by spraying 50 mL of water). Consequently, the increase in reflected wave amplitude, and thus the RCM-derived permittivity, was smaller than that observed under the 50 mL spray condition.

For the ice-saturated slab, both TIA and RCM yielded permittivity values slightly higher than those in the dry state, with increases of 0.15 and 0.13, respectively. Since ice (ε ≈ 2~3) partially replaces air in the voids, the overall permittivity rises modestly, significantly lower than under water saturation but slightly above dry conditions. Additionally, the average ice film thickness on the surface of the ice-saturated slab was less than 0.56 mm (the thickness from spraying 50 mL water followed by freezing). Thus, the RCM-derived permittivity was lower than that measured under the 50 mL spray-and-freeze condition.

The dielectric responses under different saturation states reflect the composite effect of pore-filling media (air, water, or ice) and surface films. Water saturation causes the most significant permittivity increase due to its high polarizability, while ice saturation leads to a moderate rise. The thinner surface films in saturation-based experiments result in smaller interface effects compared to external spray conditions. These findings highlight the distinct detection sensitivities of RCM and TIA to internal versus surface moisture conditions.

4.4. Dielectric Behavior of Asphalt Mixture Under Various Conditions

Based on the foregoing analysis, the relative permittivity values of dry asphalt mixtures obtained by the GPR reflection coefficient method (RCM) and thickness inversion algorithm (TIA) are in close agreement, with a deviation of less than 0.1. The dielectric properties of asphalt mixtures exhibit a strong correlation with air void content, while environmental factors such as water or ice significantly influence the measured dielectric responses.

The presence of surface water films markedly increases the RCM-derived relative permittivity. Consequently, when using air-coupled GPR to monitor the compaction status of asphalt layers during pavement construction, it is essential to correct for the effect of water films, resulting from roller spray, on the surface reflection amplitude (A0). Without such corrections, the inferred compaction degree may be overestimated.

While the systematic overestimation of permittivity by RCM under surface water conditions is clearly demonstrated in

Figure 6, the current dataset with five discrete water film thickness levels (0, 0.56, 1.11, 1.67, and 2.22 mm) provides insufficient data points for developing a statistically reliable empirical correction formula. Future research should incorporate a more granular variation in water film thickness (e.g., 0.1 mm intervals) across multiple mixture types to establish robust correction equations with validated coefficients. Such correction models would significantly enhance the field applicability of RCM for quality control during pavement construction where surface water is present.

For large-scale pavement thickness surveys based on TIA, it is advisable to conduct GPR measurements during continuous dry weather when the pavement surface is thoroughly dry. However, if the RCM is employed, surveys can also be performed under specific conditions, such as after brief rainfall, provided the surface shows no obvious ponding or excessive moisture.

Surface ice or ice-filled mixtures have a minimal effect on TIA-calculated permittivity values. Therefore, GPR thickness detection remains feasible in cold regions during winter, even when thin snow or ice covers the pavement surface, since the travel-time-based algorithm is less sensitive to icy surface layers.

The dielectric properties of asphalt mixtures are primarily governed by air void content but are susceptible to modification by external moisture. The selection of an appropriate GPR analysis method, RCM or TIA, should consider prevailing environmental conditions. For accurate compaction assessment, water film effects must be accounted for, while thickness evaluation can be performed under a wider range of conditions, provided method-specific limitations are respected.

5. Compositional Elements Affecting the Dielectric Property of Asphalt Mixture

5.1. Dielectric Mixing Model for Asphalt Mixture

The electromagnetic mixing model, grounded in the self-consistent theory of effective permittivity for scatterer-containing composites, establishes a theoretical relationship between the macroscopic physical quantity (effective permittivity) and microscopic physical quantities, such as the number of scatterers per unit volume and their polarizability. This relationship is explicitly formulated as the Maxwell-Garnett mixing rule [

37] in Equation (3).

where

εeff denotes the effective permittivity of the multiphase composite material,

N represents the number of material phases, while

Vi and

εi correspond to the volume fraction and permittivity of the

i-th phase. Within this formulation, phase k (where 1 ≤

k ≤

N) serves as the host medium, with other phases uniformly distributed as scatterers within it. The shape factor

u characterizes the geometry of the scatterers, while the interaction coefficient

v quantifies the electromagnetic coupling between adjacent scatterers. These parameters depend on the geometric arrangement and packing state of the components and are determined from statistical analysis of the dielectric test results, where

v can be any non-negative real number.

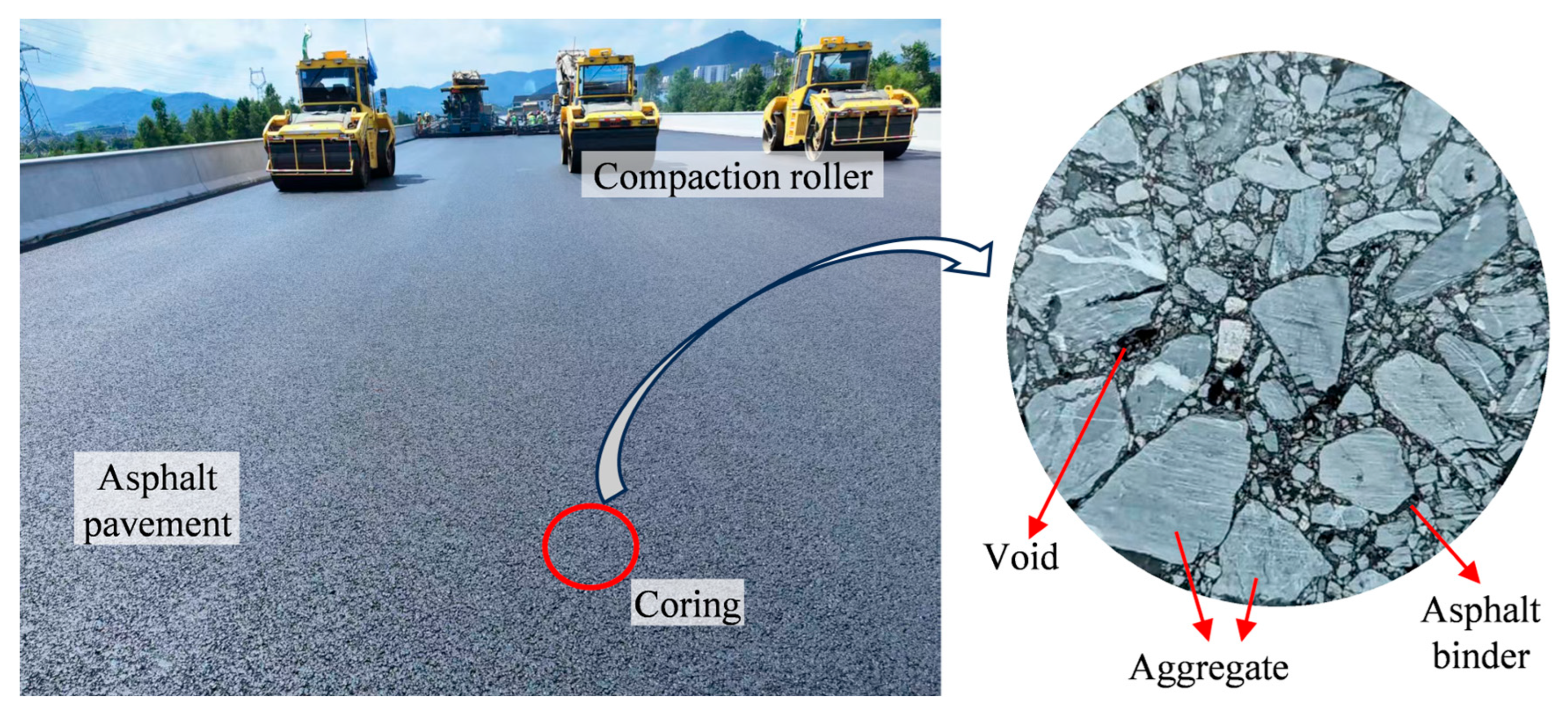

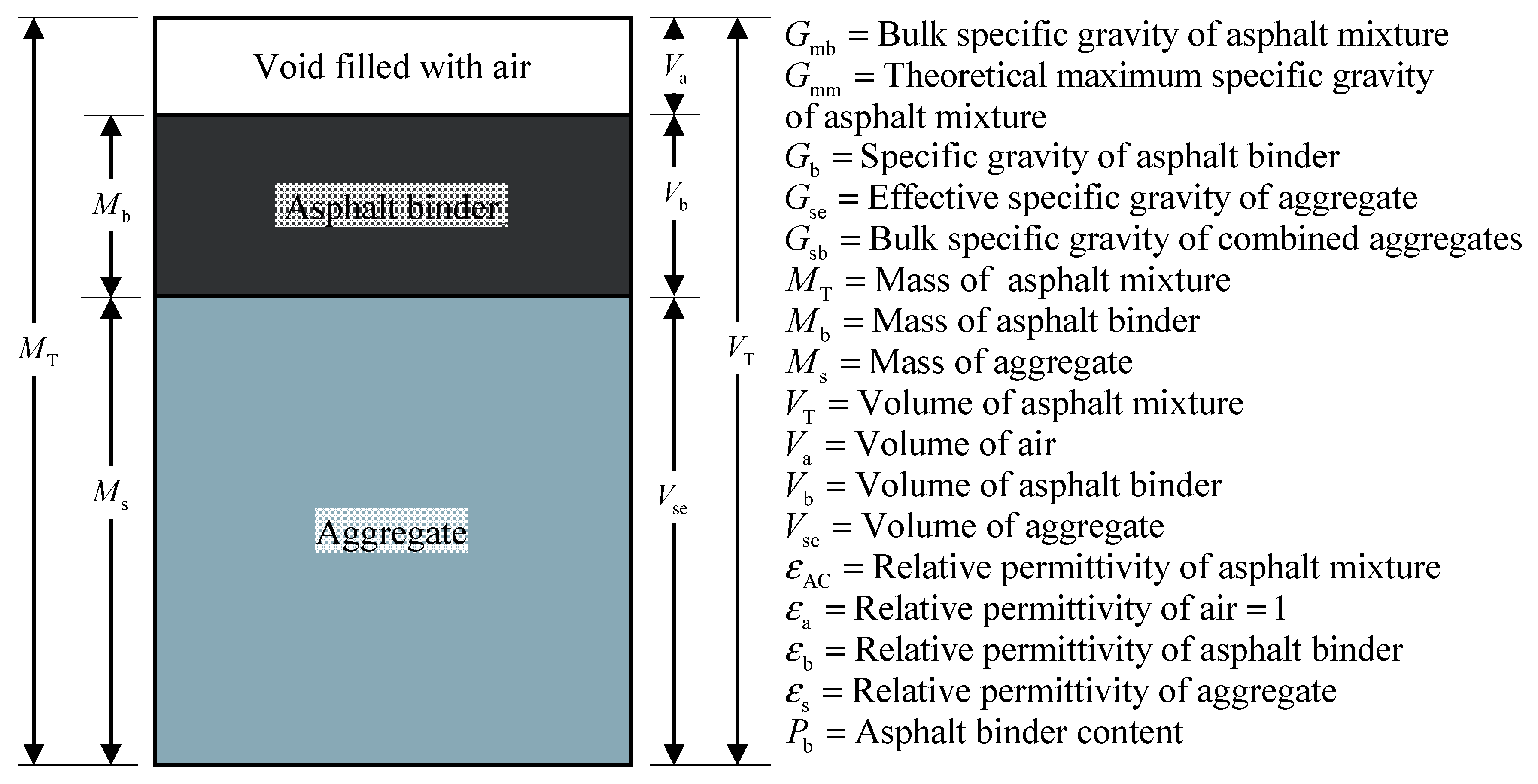

Dry, compacted asphalt mixture consists of three primary components: asphalt binder, mineral aggregates, and air voids. The mass and volumetric composition of these constituents are detailed in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, respectively. Based on the Maxwell-Garnett mixing rule given in Equation (3), a dielectric mixing model for the dry asphalt mixture is established by treating the continuous asphalt phase as the host medium, with discrete scatterers (mineral aggregates and air voids) uniformly distributed within it. This leads to the theoretical model expressed in Equation (4).

The volume fractions of air voids, asphalt binder, and mineral aggregates, represented by Equations (5), (6), and (7), respectively, are illustrated in

Figure 11. Given that the relative permittivity of air is generally taken as 1, substituting Equations (5) and (7) into Equation (4) yields Equation (8).

In previous research [

38], the authors utilized experimental dielectric data from various types of asphalt mixtures and applied the Levenberg–Marquardt method combined with a universal global optimization algorithm to determine key parameters. The optimized scatterer shape factor was found to be

u = –4.5, and the inter-scatterer influence coefficient was

v = 5.1. This leads to the ISO (Influence coefficient and Shape factor Optimization) dielectric mixing model for asphalt mixtures, formulated as Equation (9). Correspondingly, the ISO model for predicting the bulk specific gravity is given by Equation (10).

5.2. Unified Model of Dielectric Property and Volumetric Parameter for Asphalt Mixture

Key volumetric parameters in asphalt mixture design include the bulk specific gravity of the specimen (Gmb), air void content (), voids in mineral aggregate (), and voids filled with asphalt (). These parameters directly determine the optimum asphalt content and significantly influence the pavement performance of the asphalt mixture. Based on the ISO model for asphalt mixture density prediction given in Equation (10), predictive models for , , and are derived as Equations (11)–(13), respectively.

From the above, the theoretical relationship between any volumetric parameter

and the dielectric properties of the asphalt mixture can be expressed by the unified model in Equation (14). In this model, the volumetric parameters, asphalt content (

Pb), theoretical maximum specific gravity (

Gmm), effective specific gravity of aggregate (

Gse), bulk specific gravity of aggregate (

Gsb), and asphalt specific gravity (

Gb), can be obtained from mixture design records and remain relatively constant. The dielectric parameter of the aggregate (

εs) is related to its mineral composition, while the dielectric parameter of asphalt (

εb) exhibits minimal variation, typically around a value of 3.

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Compositional Factors on Dielectric Property of Asphalt Mixture

The dielectric mixing model for dry asphalt mixtures, as given in Equation (4), is transformed into a standard cubic equation (Equation (15)) with respect to the relative permittivity of the mixture. The corresponding coefficients

a,

b,

c, and

d in this equation are defined by Equations (16)–(19), respectively. Applying the Cardano formula method [

39], a positive real root of the equation can be derived, which is expressed as Equation (20). As a result, the overall relative permittivity of the asphalt mixture is represented as an explicit function of the volumetric and dielectric property parameters of its constituent components.

Furthermore, by substituting the specific values

v = 5.1 and

u = −4.5 into Equation (4), the general model reduces to the ISO dielectric mixing model for asphalt mixtures, presented as Equation (9). This specialized form provides a calibrated relationship tailored to the electromagnetic characteristics of typical asphalt-aggregate systems, enhancing its applicability for practical pavement evaluation.

The relative permittivity of 12 sets of AC-13 asphalt mixture Marshall specimens and their components (asphalt binder and mineral aggregates) was measured using a Percometer dielectric constant instrument [

38]. The

εAC of asphalt mixture, along with

Gmm,

Gsb,

Gse, as well as the

εs of aggregate and

Pb,

εb,

Gb of asphalt binder can be obtained through actual measurements or design data. These parameters should then be substituted into calculation Equations (11)–(13) to determine the air void content (

), voids in mineral aggregate (

), and voids filled with asphalt (

) in

Table 6. The measured volumetric and dielectric parameters of the AC-13 asphalt mixture specimens are summarized in

Table 6. The measured relative permittivity values of the mineral aggregates and asphalt binder were

εs = 7.7 and

εb = 2.7, respectively, while the relative permittivity of air was taken as

εa = 1, and the specific gravity of asphalt was

Gb = 1.011.

Taking Specimen #6 from

Table 6 as an example, the following volumetric and dielectric parameters of Specimen #6 were measured:

Gmb = 2.435,

εAC = 6.4,

Pb = 4.49%,

Gmm = 2.557,

Gsb = 2.738,

Gse = 2.755,

εs = 7.7,

εb = 2.7, and

Gb = 1.011. Step 1: Substituting the above parameters into Equation (11) yields the calculated air void content of Specimen #6 (

= 4.77%). Step 2: Substituting the same set of parameters into Equation (12) gives the calculated voids in mineral aggregate (

= 15.06%). Step 3: Substituting the same parameters into Equation (13) results in the calculated voids filled with asphalt (

= 68.31%). The calculated values are consistent with those reported for Specimen #6 in

Table 6. The volumetric parameters for the other specimens in

Table 6 can be obtained following the same procedure, ensuring the reproducibility and reliability of the unified model.

When the voids filled with asphalt () is held constant, a smaller voids in mineral aggregate () value indicates a higher volume fraction of aggregates in the asphalt mixture and a lower air void content (), which leads to a significantly higher relative permittivity of the asphalt mixture. Conversely, when is held constant, a higher value implies a greater proportion of asphalt and a smaller proportion of air within the void spaces, resulting in a slight increase in the relative permittivity of the asphalt mixture.

A tornado diagram was employed to analyze the influence of key parameters in the ISO dielectric mixing model for asphalt mixtures on the overall dielectric properties. The key parameters selected for sensitivity analysis included the relative permittivity of mineral aggregates (εs), the relative permittivity of asphalt binder (εb), asphalt content (Pb), and air void content ().

Reasonable variation ranges were assigned to each parameter: relative permittivity of aggregates εs = 7.7 ± 0.3, relative permittivity of asphalt binder εb = 2.7 ± 0.2, asphalt content Pb = 4.49% ± 0.3% (based on allowable deviation from design value), air void content = 4% ± 1% (covering the design range of 3–5% for AC-13 mixtures).

Using the controlled variable method, each parameter was individually set to its maximum, minimum, and mean values while keeping other parameters constant at their mean values. The corresponding results for the relative permittivity of the asphalt mixture (

εAC) were recorded as max, min, and mean, respectively. The sensitivity coefficient, Swing, was then calculated using Equation (21). A larger Swing value indicates a greater influence of the parameter on the result.

The results of the parameter sensitivity analysis for the ISO dielectric mixing model of asphalt mixtures are presented in

Table 7 and

Figure 11. The ranking of parameter influence on the dielectric properties of the asphalt mixture is as follows: relative permittivity of aggregates (

εs) > air void content (

) > relative permittivity of asphalt binder (

εb) > asphalt content (

Pb).

The relative permittivity of aggregates exhibits the most significant influence on the dielectric behavior of the asphalt mixture, underscoring the importance of accurate measurement of the dielectric properties of mineral aggregates. The second most influential parameter is air void content, indicating a strong correlation between the dielectric properties of the asphalt mixture and its void structure. This implies that the overall dielectric characteristics can effectively reflect the compactness of the asphalt mixture. In contrast, asphalt content has the lowest sensitivity coefficient, at only 1.78%, suggesting that minor variations in asphalt content are unlikely to be discernible in the dielectric response of the asphalt mixture.

6. Conclusions

Through comparative analysis of different methods for measuring dielectric properties of asphalt mixtures, systematic investigation of the influences of water, ice, and air voids on these properties has been conducted. Testing methodologies have been established for both laboratory and field conditions, accounting for varying environmental factors. A unified functional relationship has been developed between the dielectric properties of asphalt mixtures and the dielectric-volumetric parameters of their constituents. The principal findings are summarized as follows:

For dry asphalt mixtures, close agreement has been observed between dielectric constant values obtained through the GPR-based reflection coefficient method (RCM) and thickness inversion algorithm (TIA), with deviations remaining below 0.1. A strong correlation has been identified between the dielectric properties and air void content of asphalt mixtures.

Surface water films have been found to significantly increase the relative permittivity calculated by the RCM. Consequently, when air-coupled GPR is employed to monitor compaction during asphalt pavement construction, correction for the influence of water films resulting from roller spray on the surface reflection amplitude (A0) is essential.

Minimal impact on TIA-calculated relative permittivity has been observed from surface ice and ice-filled voids. Therefore, GPR thickness detection remains applicable in cold regions during winter, even with thin snow or ice layers present on the pavement surface.

Water-saturated asphalt mixtures exhibit higher relative permittivity compared to dry conditions. For extensive pavement thickness surveys utilizing TIA, measurements are recommended under continuous dry conditions. Alternatively, the RCM may be applied following brief rainfall events provided no significant surface water accumulation exists.

A unified functional relationship between the dielectric property and volumetric parameter for dry asphalt mixtures has been established. This formulation demonstrates a strong correlation between key volumetric parameters including bulk specific gravity, air void content, voids in mineral aggregate, voids filled with asphalt, and dielectric characteristics.

Sensitivity analysis of the ISO dielectric mixing model for dry asphalt mixtures reveals the following parameter influence hierarchy: relative permittivity of aggregates > air void content > relative permittivity of asphalt binder > asphalt content. These results emphasize the critical importance of accurate determination of aggregate dielectric properties.

Future Work and Limitations

Although the current study employed a 2 GHz center-frequency antenna, consistent with common practice in asphalt pavement assessment, both the Reflection Coefficient Method (RCM) and Thickness Inversion Algorithm (TIA) are fundamentally based on electromagnetic wave theory applicable across a broad frequency range. The RCM relies on amplitude ratios at material interfaces, which remain frequency-independent when properly calibrated, while the TIA depends primarily on wave propagation velocity, a material property invariant with frequency under lossless conditions. Future work will systematically investigate the sensitivity of these methods to antenna frequency, particularly in the 1–2.5 GHz range typically used for pavement evaluation.

Despite efforts to systematically model the environmental impacts and compositional elements affecting dielectric characteristics of asphalt mixtures, several limitations remain and warrant further investigation. The current framework does not fully capture the nonlinear interactions between multiple environmental factors, such as cyclic freeze–thaw actions coupled with varying moisture saturation levels, nor does it adequately address the dielectric behavior of mixtures incorporating non-traditional or recycled materials with inherently variable compositions. Future research should focus on developing more sophisticated multi-physical models that can account for these synergistic effects under realistic, transient environmental conditions. Additionally, there is a need to establish a comprehensive database of dielectric properties for a broader range of mixture designs and material types, which would support the creation of more generalized and reliable predictive models for industry-wide application.

Although temperature variations are known to influence the dielectric properties of asphalt mixtures and consequently affect GPR measurement accuracy, this study primarily investigated the effects of moisture, ice, and material composition. Future research should systematically examine temperature-dependent dielectric behavior across different mixture types and establish corresponding correction methodologies for field applications.

Future research should systematically evaluate the impacts of alternative time-picking methods, antenna frequency selection, and surface conditions (including oscillation amplitude and roughness) on the accuracy of dielectric property assessment under real-world surveying conditions to validate the practical implementation of the proposed methodology.