Abstract

Currently, there is no cost-effective drying approach for apricots that effectively preserves color and prevents browning. Using a psychrometric chamber to simulate environmental conditions in Malatya, Turkey, apricots were dried, with freeze-dried samples serving as a control. The samples were analyzed for their water and nutritional contents as well as chemical and structural evaluation. The Agricycle® passive solar drier was tested for its ability to dry apricots while reducing browning. Freeze-dried samples appeared whiter (bleached), whereas passive solar-dried apricots retained their natural color. The results showed that passive solar drying successfully reduced the water content to below 20% (11.92%) and limited browning, based on visual inspection and colorimetry. Nutritionally, passive solar-dried apricots had comparable total phenolics to freeze-dried samples (2.72 vs. 4.06 GAE/g dry mass), but higher vitamin C (1.86 vs. 1.11 mg/g dry mass) and lower dissolved solids (45.36 vs. 73.02 °Brix). The microstructural analysis revealed notable differences between drying methods. Overall, the Agricycle® passive solar drier offers a simple, cost-effective solution for fruit drying.

1. Introduction

Apricots (Prunus armeniaca L.), which originated in China, quickly spread throughout Central Asia and are now considered the third most economically important stone fruit worldwide, following peaches and plums [1,2]. Apricots possess a delicious taste, pleasant aroma, and vibrant coloration, accompanied by high levels of vitamin C, carotenoids, and total phenolic compounds [3]. Specifically, apricots are a rich source of dissolved solids (soluble sugars) and vitamins such as vitamin C [4]. Additionally, phenolic compounds are an important antioxidant present in apricots [5]. Because fruits are highly perishable, the drying of apricots is of particular interest, as it effectively reduces their moisture content and extends their shelf life [6]. Turkey is the world leader in apricot production, and Malatya accounts for 50% of the country’s apricots, with 90% being used for drying [7,8]. Hence, in this study, the average temperature of Malatya, Turkey during summer (26–27 °C) was used for drying [9,10].

The most common method of apricot drying in Turkey is traditional sun-drying [11]. In this process, apricots are placed on trays, racks, or cloths and are exposed to sunlight for an extended period of time [12]. Sun-drying is relatively inexpensive; however, uncontrollable factors—such as weather—lead to fruit batches that are not uniform. Direct exposure to sunlight may result in loss of the nutritional value of the apricots [13]. Additionally, prolonged exposure to elevated temperatures, in the presence of oxygen, triggers oxidation reactions that darken apricots to an unappealing brown color (Figure 1) [14]. This is a major issue, as the visual appearance of food influences consumer perception and acceptance [15].

One way to overcome the color change associated with drying apricots is sulfur treatment (Figure 1) [16]. In some individuals, certain thresholds of sulfur have been shown to cause symptoms such as throat and gastric burning, headache, and vomiting [17]. Asthmatics, in particular, are prone to respiratory issues from sulfur treatment [18]. The most common method of sulfur treatment is fumigation, which is typically performed before drying. During this process, sulfur dioxide is formed through a combustion reaction and fills a chamber where the fruit is placed. For apricots, the treatment lasts around 8–10 h. Improper desulfitation in these areas may cause harm to workers [19].

Figure 1.

Photo of commercial dried apricot products: left: sulfur-treated; and right: non sulfur-treated.

Other drying methods include freeze-drying, hot air drying, microwave vacuum drying, and infrared drying [20,21]. Freeze-drying removes moisture through sublimation, effectively preventing spoilage. Qiaonan Yang et al. compared various drying methods and observed that vacuum freeze-drying resulted in the highest-quality dried apricots [21]. However, freeze-drying involves long drying times and high energy consumption; the associated costs make large-scale implementation challenging [22]. Hot air-drying involves passing heated air over the fruit product. Ihsan Karabulut et al. investigated the hot air-drying of apricots and found that hot air-drying required less drying time resulting in greater nutritional quality than solar drying [23]. Although this process is faster than traditional sun drying, it exhibits poor energy efficiency, and the wasted heat can negatively impact the environment [24]. Microwave vacuum-drying converts electromagnetic energy into heat, resulting in a rapid yet complex process. Jian-Rui Gao et al. reported that microwave vacuum-drying exhibited the fastest drying rate among all drying approaches investigated [20]. However, uneven electromagnetic field distribution can cause localized overheating, leading to scorching of the dried product [25]. Infrared drying offers several advantages, including high energy and heat transfer efficiency and short drying times. Seda Kayran et al. concluded that infrared drying led to more efficient drying compared to traditional convective and solar methods with a higher diffusivity measure [26]. Nevertheless, process control can be challenging, as infrared radiation can cause surface overheating and has limited penetration depth [11,27]. Among these methods, there is currently no single option that combines simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and high product quality.

An Agricycle© passive solar drier has previously been validated using a psychrometric chamber for temperature and relative humidity control using apples and pineapples [28,29]. The passive solar drier was initially designed to combat food loss, especially in regions like Sub-Saharan Africa. The tray, designed in black to maximize solar energy absorption, is heated by solar radiation (particularly the infrared portion) when exposed to the sun, thereby producing hot air. Then, the fruit is dried by the hot air in the tray via convection; the heated trays also enable drying via conduction. Water from the fruit is removed by the hot air and released through the holes in the tray [28,29]. The results from previous studies indicate that passive solar drying meets the appropriate acceptable limits for parameters such as water content. Nutritional testing results were also comparable to those from the freeze-dried samples. Additionally, there was no significant color change during the drying process. Compared to current drying methods, the Agricycle© passive solar drier is cost-effective, has a simple set-up and operation, all the while producing a high-quality product. Considering the system’s effectiveness and positive socioeconomic impacts, it is beneficial to explore more of its applications in fruit drying.

The objective of this project is to utilize passive solar drying for preserving apricots, particularly to prevent browning during drying, based on promising results from our previous studies, discussed above [28,29]. The previous studies focused on validating the passive solar dehydration system by utilizing a psychrometric chamber to simulate specific environmental conditions. This study demonstrates the high potential of utilizing a passive solar drying system, particularly in remote regions, for drying apricots. In summary, the novelties of this work include: (1) Regarding the drying approach, passive solar drying is investigated, which is simple, cost-effective, and capable of use in remote regions; (2) Unlike other drying studies, this work integrates a controlled psychrometric chamber that mimics Malatya’s climatic conditions and compares the results against freeze-dried apricots as a benchmark for post-drying quality assessment, in addition to using frozen (fresh) apricots as a control; (3).Compared to our previous studies, this work focuses on the application of a passive solar drying system rather than its validation; and (4) Regarding data analysis, by normalizing all results to a dry-mass basis, this study enables direct and standardized comparison across the different drying methods, highlighting the system’s potential as a sustainable alternative for high-quality fruit preservation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Fresh apricots of a similar size, color, and ripeness were purchased on the day of experimentation from a local Fresh Thyme store. Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (F9252), gallic acid (G7384), potassium permanganate (KMnO4; 223468), oxalic acid (O0376), and sodium borohydride (NaBH4; 80637300) were obtained from MilliporeSigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) and were used as received.

2.2. Process of Passive Solar Drying and Freeze-Drying of Apricots

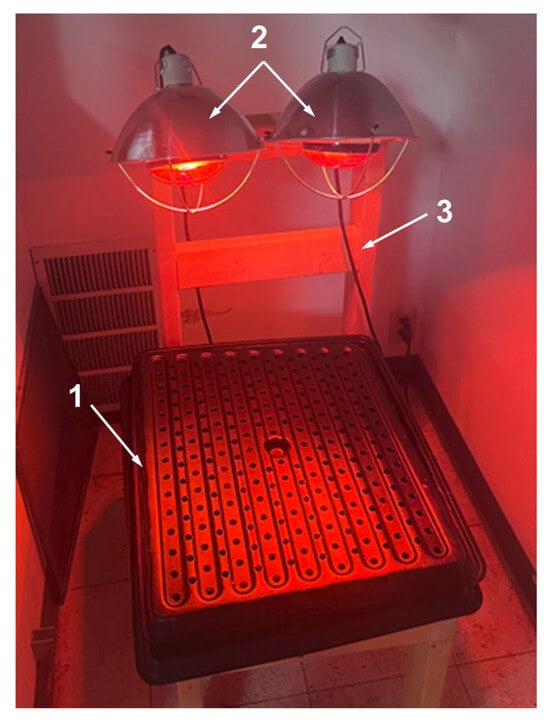

An Agricycle© (Milwaukee, WI, USA) solar drier, consisting of stacked polyvinyl ether trays and an infrared heat lamp, was set up in a psychrometric chamber to solar dry the apricots in the desired climate. To conduct freeze-drying, a HarvestRight™ freeze drier (Salt Lake City, UT, USA) was used with the corresponding drying trays. Fresh apricots were sliced, creating thin wedges of 3.53 ± 0.76 mm in thickness and 2.41 ± 0.30 g in mass each before drying. Each of the sample masses were recorded prior to their respective treatment, which would eventually be used to determine the water content. The slices were divided into three groups: passive solar-dried, freeze-dried, and frozen (control). For passive solar drying, slices were evenly placed inside the top tray and enclosed. The trays containing the sliced apricots were placed under two infrared lamps, with approximately 0.5 m separating the lamps from the tray surface. Two 375-watt 125-volt R40 infrared heat lamps (catalog #03689-SU; Sunlite Manufacturing, Brooklyn, NY, USA) were used to mimic natural sunlight. The solar dehydration system (trays) was placed in a psychrometric chamber where temperature (26–27 °C) was maintained and recorded over a 16 h period (Figure 2). The trays were designed to facilitate heat and mass transfer to improve drying outcomes compared to traditional open sun drying. The material selection of the tray enhances conductive heat transfer, leading to moisture from the fruit’s interior migrating to the surface where it can evaporate. The demographics of holes in the tray enable the moisture to escape and not be reabsorbed. These aspects of the trays lead to a very uniform and efficient drying profile. The psychrometric chamber has functionality allowing control over temperature via a blower and humidity via sprayers, as well as sensors that show live, real-time readings of different temperature and humidity values. The 16 h drying time was determined in our previous studies and confirmed to be optimal, as the apricots reached approximately 10% water content consistently (significantly lower than 20%) [28,29]. If the drying time is too short (less than 14 h), the water content remains higher than 20%. On the other hand, extending the drying time further leads to a decrease in nutritional value. The procedure for determining water content is discussed in Section 2.3. Similarly, slices were evenly distributed on the tray for freeze-drying using the default settings, the freeze drier had settings that automated progression through the stages of freeze-drying. Frozen samples were sealed in mylar bags and placed in the −20 °C freezer for comparison. All dried samples were then collected and sealed in mylar bags for further analysis. Regarding the “fresh sample” control, slices from the same batches were frozen at −20 °C to prevent further ripening and potential deterioration—especially after slicing—during the waiting period for their counterparts to be dried.

Figure 2.

Passive solar-drying setup within a psychrometric chamber: (1) trays made of polyvinyl ether; (2) infrared heat lamps; and (3) a wooden stand holding the trays and lamps.

2.3. Water Content Testing

Approximately 4.5 g of passive solar-dried and freeze-dried apricots, and 20 g of frozen apricots, were weighed into separate dishes and placed in an oven (Fisher Scientific™, Isotemp™, Waltham, MA, USA) at 105 °C to determine the water content. The masses of each sample were recorded every 15 min until a negligible change was observed. Water content was then determined using Equation (1) [28,29]. By comparing the mass before baking in the oven and after baking, the mass of water lost during baking was determined. This information helped to calculate the water content achieved following the drying treatments being studied:

2.4. Color Measurement and Analysis

Colorimetry testing was performed on all three apricot groups using a colorimeter (WR10QC Port-able colorimeter; iWave Optoelectronics Technology Co., Ltd.; Shenzhen, Guangdong, China). The colorimeter was blanked using a white piece of paper. Color measurements of lightness (L*; white+/black−), redness (a*; red+/green−), and yellowness (b*; yellow+/blue−), were obtained from the same three relative locations on each slice for each sample type. Three separate batches were analyzed. The readings were averaged for all three batches and the total color difference (ΔE) was calculated using Equation (2) [28,30]. The frozen samples were used as standard values (i.e., ):

2.5. Vitamin C, Phenolic Compounds, and Dissolved Solids Contents Testing

Five grams of each apricot group were blended in 50 mL of deionized (DI) water to obtain apricot extract. Each extract was centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 min to obtain the supernatant for analyses. Quantifying phenolic compounds is important due to the effect on taste of the product. Phenolics contribute to bitterness and astringency, the color of the fruit, and in juices impact their turbidity and sedimentation. Phenolic compounds offer health benefits such as antioxidants, anti-microbials, and anti-inflammatory agents [31]. Additionally, phenols serve as a substrate for polyphenol oxidase (PPO) oxidation; thus, major decreases in concentration can be an indication of darkening [32,33]. Total phenolic contents were measured using the Folin–Ciocalteu method. Each supernatant was added to a mixture of 1.58 mL DI water and 100 µL Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. The mixture was vortexed for 10 min after 300 µL of 20% Na2CO3 solution was added. After 2 h of incubation in the dark, absorbance readings were taken at 765 nm using a UV–Vis Spectrophotometer (Genesys 150, Thermo Scientific; Waltham, MA, USA). The concentrations were then calculated using a standard curve created by different concentrations of gallic acid (y (abs) = 0.9834x (concentration); R2 = 0.9988).

Retention of vitamin C is an important metric because it is essential for tissue growth and repair, protects cells from oxidative damage by reactive oxygen species, and minimizes inflammation [34]. Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) testing was measured using the supernatant. Briefly, a standard curve was created by using various concentrations of ascorbic acid in a 0.5% (w/v) oxalic acid (C2H2O4) solution. After adding 0.1 mL of KMnO4 solution to each 1 mL aliquot and incubating for 5 min, the absorbance at 530 nm was measured using a UV–Vis Spectrophotometer [28,35]. The standard curve was then generated using Microsoft Excel (y (abs) = –0.0169x (concentration) + 0.0687; R2 = 0.9774). For the apricot samples, supernatant was used instead of the ascorbic acid standard solutions.

Dissolved solids contents were analyzed using an AiChose (Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, China) portable refractometer using the supernatant. Readings were taken against a blank of DI water. After blanking, the desired sample was introduced into the apparatus, and the measurement was manually read and recorded [28]. This procedure was repeated for each prepared sample supernatant.

2.6. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopic Analysis

Spectral readings were taken for chemical analysis using attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR; Nicolet iS50, ThermoFisher Scientific; Waltham, MA, USA) spectroscopy in the range of 4000–650 at room temperature using the transmission mode. Each sample was placed in direct contact with the ATR crystal; the same slice region (center) was used for different samples without any special preparation. Background data were collected at the beginning and between samples [28]. The spectra were graphed and analyzed using OriginLab® (Northampton, MA, USA) to assess chemical changes associated with drying.

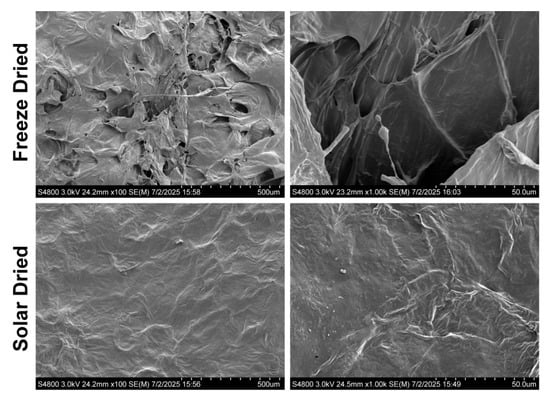

2.7. Microstructure Analysis

Scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, Hitachi S-4800 ultra-high resolution cold cathode field emission scanning electron microscope, Kefeld, Germany) was used to analyze the surface microstructure of the passive solar-dried and freeze-dried samples. The two dried samples were mounted onto an aluminum stub and vacuum-coated with a 4 nm layer of iridium before imaging to increase conductivity. Similar center regions of different samples were examined and imaged at different magnifications (an accelerating voltage of 3 kV) [28].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Each of the tests was conducted in triplicate. For the vitamin C, phenolic compounds, and dissolved solids tests, data were normalized to account for the varying water content among the samples using Equation (3) [28]. Normalization allows for the contents of each sample to be compared “fairly”, with differences in water content appropriately taken into consideration. ANNOVA and t tests were utilized for statistical analysis using Microsoft Excel, with p < 0.05 indicating significant difference.

3. Results and Discussion

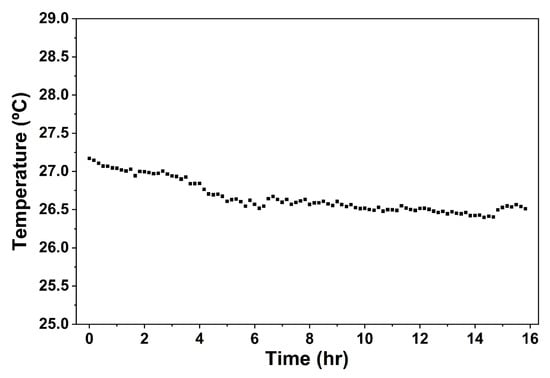

3.1. Simulation of Malatya Climate

The summer months (June, July, and August) of Malatya, Turkey, have an average temperature between 26 and 27 °C [9]. During the process, the passive solar drier (trays) was placed in the psychrometric chamber; the infrared bulbs were used to simulate solar energy. The psychrometric chamber was able to maintain the temperature between 26.4 and 27.4 °C, as shown in Figure 3. Previous studies have shown the effectiveness of the psychrometric chamber to maintain the target temperature [28,29]. Maintaining this target temperature is essential, as it enables the set-up to be reproducible, scalable, and practical for drying operators in Malatya, Turkey.

Figure 3.

Temperature changes with time within the psychrometric chamber during the 16 h drying period.

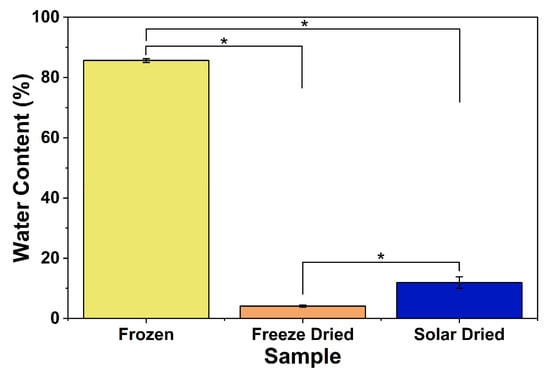

3.2. Water Content Post Drying

To ensure the quality and safety of dried fruits, the water content must be adequately low, due to the correlation between water content and microbial growth. Alternatively, drying allows for easier packaging, transportation, and storage [36]. Standard values for dried apricots vary. The United Nations World Health Organization (UN/WHO) requires less than 25% water content for dried apricot pieces (without preservatives), while the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) requires less than 20% water content [37,38]. The passive solar-dried apricots were found to have water content below the standard value, 11.92 ± 1.93%, indicating that this is an effective drying method while slowing microbial activity. The water content values for frozen apricots and freeze-dried apricots were 86% and ~4%, respectively. There was a statistical significance between each apricot group treatment (Figure 4). Hence, the 16 h drying period is sufficient to dry the apricots, consistent with field use of the system (typically 1–2 days). This drying time is also consistent with previous studies using apples and pineapples, possibly showing that the passive solar drying trays can be used effectively for a variety of fruit applications [28,29].

Figure 4.

Water content of different apricot samples. * indicates significant difference (p < 0.05).

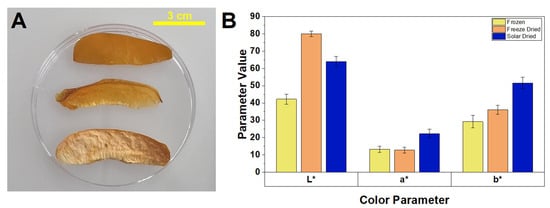

3.3. Color Post Drying

Color changes to food can result in a dramatic impact on the expectations and experience of the consumer. In apricots, polyphenol oxidase (PPO) is the enzyme responsible for the darkening of tissue and is induced by cell membrane damage. The mechanism for activating the PPO zymogen in plants is unknown, but the browning pathway is. PPOs act by oxidizing phenols into quinones, which are capable of polymerizing into brown pigments that aggregate to the surface of the fruit. Approximately 50% of fruits are wasted each year due to this enzymatic spoilage; therefore, finding a drying method that effectively reduces browning will have high value [32]. The passive solar-dried samples had the highest a* and b* values, indicating the highest redness and yellowness. Increases in a* (redness) may be attributed to changes to anthocyanin-related compounds during heating treatments. Leucocyanidin is oxidized to a quinone methine intermediate that can be converted to red cyanidin through a conjugated anhydrobase pathway. Increases in b* (yellowness) may be attributed to the biosynthesis and accumulation of yellow pigments, such as naringenin, which are produced in response to tissue stress, with one contributing factor being mechanical stress caused by the physical cutting of fruit and high heat [39]. The freeze-dried samples had the highest L* value, exhibiting the greatest lightness (Figure 5). The b* values correlate with consumer preference, as decreases are associated with natural discoloration of the fruit [40]. In a study conducted by Yang et al., four different methods of apricot drying were tested; vacuum freeze-drying (VFD) was found to have the lowest browning degree. Their a*, b*, and L* measurements were comparable to the values found in this study. The disadvantage of VFD, however, is that the energy requirement is relatively high compared to passive solar drying, which requires no electricity [21]. The overall color difference (ΔE) was 32.6 for passive solar-dried and 38.4 for freeze-dried when compared to the frozen sample. This difference indicates that the color of the passive solar-dried sample was overall closer to the frozen samples. Compared to traditional sun drying, passive solar drying most likely leads to reduced browning due to shorter drying times, the absence of exposure to UV light, and reduced enzymatic browning from PPO. Hence, this approach helped to prevent browning of the apricots.

Figure 5.

(A) photo of different apricots samples post drying. From top to bottom: frozen, passive solar-dried, freeze-dried; and (B) comparison of color parameters for apricots post drying.

3.4. Vitamin C, Phenolic Compounds, and Dissolved Solids Contents Post-Drying

Dissolved solids, vitamin C, and phenolic compounds were the three nutritional components that were tested in the various apricot samples. For each of the tests, to account for differing levels of water content following preservation, the data were normalized by dividing by the per dry sample mass, as described in the Materials and Methods.

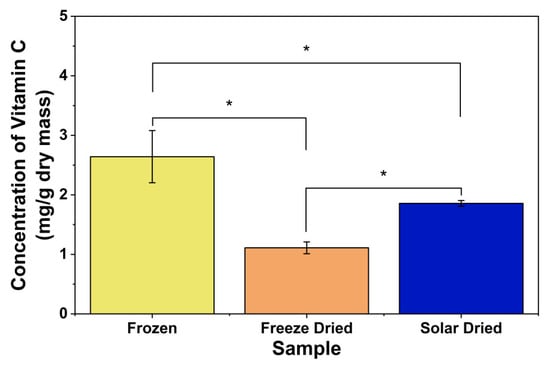

As shown in Figure 5, there were significant differences in vitamin C (ascorbic acid) content among the different samples. Frozen apricots had the highest vitamin C levels per dried mass, followed by passive solar-dried apricots, while freeze-dried apricots had the lowest levels. When conducting the experiment, default settings were used for freeze-drying. If shelf temperature was lowered and the freeze-drying parameters were optimized, vitamin C content would be higher than the solar-dried group. However, these optimization processes may not be cost-effective and process optimization was not the main focus of this article. These findings are consistent with those of Gao et al., as ascorbic acid loss is expected, especially due to oxidation, thermal treatment, and drying [20,34]. Given that vitamin C is water-soluble and that passive solar dehydration uses heat during drying, the loss of water and heat input most likely contributed to the loss of vitamin C. As shown in Figure 6, the freeze-dried apricots had significantly lower vitamin C levels compared to passive solar-dried apricots. Freeze-drying parameters, such as drying temperature, pressure, and time, as well as the type of fruit, can impact vitamin C retention [28,41]. Higher freeze-drying temperatures lead to increased vitamin C degradation, while lower pressure and shorter time increase retention [42].

Figure 6.

Vitamin C concentrations of different apricot samples. * indicates significant difference (p < 0.05).

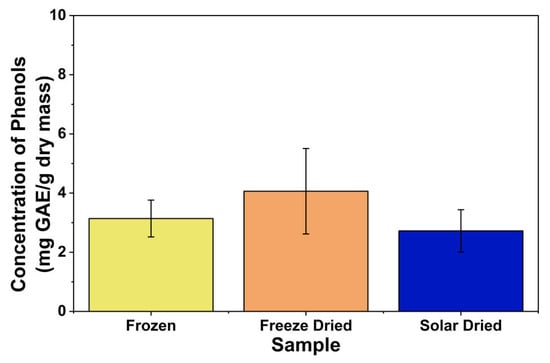

Figure 7 shows the results of the phenolic compounds test. On average, freeze-dried apricots had the highest phenolic compound concentration per dry mass, followed by frozen apricots, and passive solar-dried apricots. However, no significant difference was found between the preservation methods. There are two main forms of phenolic compounds in plant tissues: free (extractable) phenolics and bound phenolics, which are chemically bound to cell wall components. The observed reduction in total phenolic content after drying may be related to changes in the bound phenolic fraction, as heat and oxygen are two of the main factors that contribute to the breakdown of phenolic compounds. Previous studies have reported that, in fresh samples, the majority of total phenolics are attributable to bound phenolics; however, after solar drying, the proportion of total phenolics contributed by bound forms decreases markedly [43]. This suggests that solar drying may alter the integrity of cell wall–phenolic linkages, weakening or cleaving these bonds. Under solar-drying conditions, such structural changes may facilitate the release of bound phenolics, making them relatively more available for PPO to use as a substrate, thereby leading to the overall reduction in measured phenolic content. These findings are consistent with Wani et al. [44], who reported that drying of apricots resulted in the lowest phenolic compound concentration due to the activity of PPO. A statistically significant difference was observed between the dried apricots and the frozen and canned apricots in their study; however, the drying process was conducted at a higher temperature, which further increased PPO activity [44].

Figure 7.

Phenolic compound contents of different apricot samples.

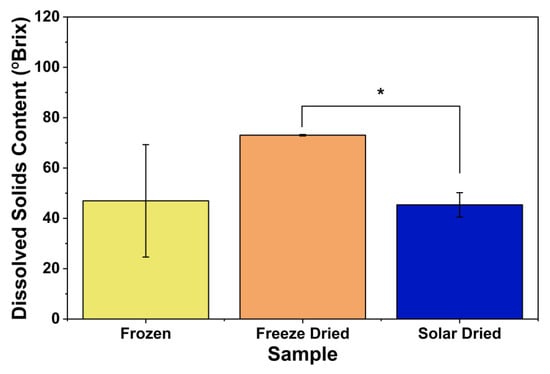

Dissolved solids are a broad class that includes carbohydrates, organic acids, proteins and fats, as well as minerals. Higher dissolved solids correspond to lower acidity and a sweeter taste [45]. Mature fruits contain more sugars, contributing to a more desirable taste [46]. The freeze-dried apricot samples had the highest level of dissolved solids, while the passive solar-dried had the lowest levels (Figure 8); the difference was statistically significant. Studies in the literature suggest that, as temperature increases, the amount of dissolved solids decreases. The most likely explanation for this phenomenon is that, at higher temperatures, fruit exhibits a higher rate of respiration, which consumes sugars as reactants. Therefore, increasing the temperature leads to a decrease in dissolved solids [47]. These findings are consistent with previous studies using pineapple [28].

Figure 8.

Dissolved solids content of different apricot samples. * indicates significant difference (p < 0.05).

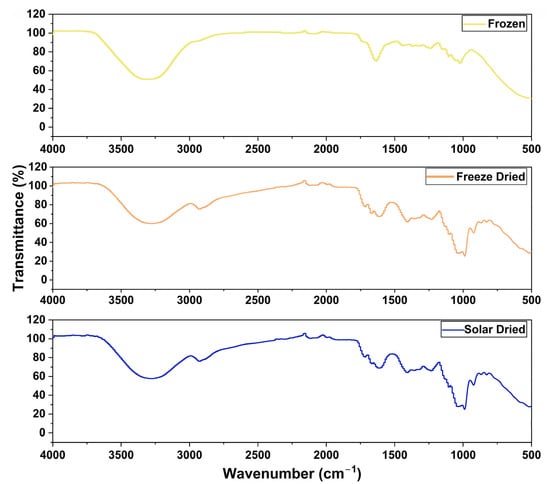

ATR-FTIR was used to acquire an infrared spectrum for each apricot sample. These spectra reveal chemical properties such as functional groups [48]. As shown in Figure 9, the IR spectrum of the frozen sample appears to have a broader peak around 3300 cm−1. This wavenumber is characteristic for O-H stretching, including phenolics, and, in the frozen sample, was mostly contributed by water [28,49]. There also was a peak around 1635 cm−1 for the frozen apricot sample, where O-H bonds are expected to bend [28]. Given the significantly higher water content of frozen apricot samples (Figure 4), these results were expected. The passive solar-dried and freeze-dried samples also had a peak at approximately 985 cm−1. This region represents the nutritional contents such as sugars and organic acids [49]. In the solar and freeze-dried samples, the lower water content concentrates the nutrients. Therefore, a peak is expected when compared to the frozen samples. The freeze-dried and passive solar-dried IR spectra were, overall, very similar, indicating a similar chemical composition.

Figure 9.

Infrared spectra of different apricot samples.

3.5. Microstructure Post Drying

Microstructure plays an important role in the multisensory perception of flavor. SEM imaging was used to examine the respective microstructures of solar and freeze-dried apricots (Figure 10). Frozen apricots were excluded due to their high water content. The freeze-dried apricots were observed to be very brittle and fractured readily, which is connected to their high porosity, as observed in the SEM images [28]. The porous structure is most likely a result of sublimation during freeze-drying [21]. The passive solar-dried apricots were observed to contain a smoother surface. The results were similar to the previous study using pineapple.

Figure 10.

Scanning electron microscope images of dried apricot samples.

4. Conclusions

The Agricycle® passive solar drier successfully dried the apricots to a final water content of less than 20% water content (~12%) within 16 h. Importantly, the effectiveness of passive solar drying for reducing the browning of apricots was successfully demonstrated during this study. With regard to the microstructure of the passive solar-dried apricots, they were very different from the freeze-dried group. Moreover, vitamin C, total phenolic compounds, and dissolved solids testing indicated the passive solar drier does not cause significant losses compared to freeze-drying. Vitamin C content for the passive solar-dried apricots was higher, while phenolic compounds and dissolved solids were lower compared to those of the freeze-dried apricots. Future directions include investigating the enzymatic rate of PPO and the enzyme’s temperature dependence, as well as redesigning the drying trays for optimal arrangement. In addition, durability and wear testing of the trays can be conducted. Overall, the results indicate that passive solar drying is an effective approach for apricot drying and color preservation, and can also be applied for other fruit-drying applications as a cost-effective tool.

Author Contributions

Author contributions: M.D. (Mason Dopirak), M.D. (Matus Dopirak), A.G., M.N., M.S., A.T. and W.Z. performed the experiments, while M.D. (Mason Dopirak), M.D. (Matus Dopirak) and W.Z. performed data analysis. M.D. (Mason Dopirak), M.D. (Matus Dopirak) and W.Z. took the lead in writing. W.Z., M.S. and Q.C. supervised the project. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge De’Jorra Valentin for her technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wani, A.A.; Zargar, S.A.; Malik, A.H.; Kashtwari, M.; Nazir, M.; Khuroo, A.A.; Ahmad, F.; Dar, T.A. Assessment of variability in morphological characters of apricot germplasm of Kashmir, India. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 225, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhone, M.A.; Bains, A.; Tosif, M.M.; Chawla, P.; Fogarasi, M.; Fogarasi, S. Apricot Kernel: Bioactivity, Characterization, Applications, and Health Attributes. Foods 2022, 11, 2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatas, N. Evaluation of Nutritional Content in Wild Apricot Fruits for Sustainable Apricot Production. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Sun, J.; Pu, X.; Shi, X.; Cheng, W.; Wang, B. Volatile Compounds Analysis and Biomarkers Identification of Four Native Apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) Cultivars Grown in Xinjiang Region of China. Foods 2022, 11, 2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafkaletou, M.; Velliou, A.; Christopoulos, M.; Ouzounidou, G.; Tsantili, E. Impact of Cold Storage Temperature and Shelf Life on Ripening Physiology, Quality Attributes, and Nutritional Value in Apricots—Implication of Cultivar. Plants 2023, 12, 2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Hu, C.; Li, J.; Xiao, H.; Jia, W.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Tang, Z.; Chen, B.; Yi, X.; et al. Effects of Different Natural Drying Methods on Drying Characteristics and Quality of Diaogan apricots. Agriculture 2024, 14, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyraz, S.; Gul, M. The Development of Apricot Prodcution and Foreign Trade in the World and in Turkey. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2022, 22, 601–616. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Soufi, M.H.; Alshwyeh, H.A.; Alqahtani, H.; Al-Zuwaid, S.K.; Al-Ahmed, F.O.; Al-Abdulaziz, F.T.; Raed, D.; Hellal, K.; Mohd Nani, N.H.; Zubaidi, S.N.; et al. A Review with Updated Perspectives on Nutritional and Therapeutic Benefits of Apricot and the Industrial Application of Its Underutilized Parts. Molecules 2022, 27, 5016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Data. Available online: https://en.climate-data.org/asia/turkey/malatya/malatya-281/ (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Uzundumlu, A.; Karabacak, T.; Ali, A. Apricot Production Forecast of the Leading Countries in The Period of 2018–2025. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2021, 33, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulvahitoglu, A.; Abdulvahitoglu, A.; Cengiz, N. A Comprehensive Analysis of Apricot Drying Methods via Multi-Criteria Decision Making Techniques. J. Food Process Eng. 2024, 47, e14759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, R.; Uğur, Y.; Levent, Y.; Erdoğan, S.; Hatterman-Valenti, H.; Kaya, O. Sun-Drying and Melatonin Treatment Effects on Apricot Color, Phytochemical, and Antioxidant Properties. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inyang, U.; Oboh, I.; Etuk, B. Drying and the Different Techniques. Int. J. Food Nutr. Saf. 2017, 8, 45–72. [Google Scholar]

- Karaman, B.; Tamer, C.; Ozcan Sinir, G.; Suna, S.; Çopur, Ö.U. Impact of different drying parameters on color, β-carotene, antioxidant activity and minerals of apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.). Ciência Tecnol. Aliment. 2016, 36, 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Nanjundappa, N.; Umadevi, B.; Jayasimha, R.; Thennarasu, K. The influence of color on taste perception. Natl. J. Physiol. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2023, 13, 1945–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, F.; Ozgen, M.; Asma, B.M.; Aksoy, U. Quality and nutritional property changes in stored dried apricots fumigated by sulfur dioxide. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2015, 56, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otlu, O.; Gul, M.; Onal, Y.; Kıran, T.; Colak, C.; Karabulut, A. Does the high sulfur content in apricots affect oxidative stress? Running title: Effect of sulfur amount on oxidative stress. Med. Sci. 2022, 11, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asma, B.M. Malatya: World’s Capital of Apricot Culture. Chron. Hortic. 2007, 47, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Rustamova, R.; Mamatsabirov, F.; Sulaymanova, S.; Rakhmatov, A.; Babayev, A.; Allenova, I.; Isomiddinova, H. Study on sulfitation of fruits and berries: Methods of sulfitation and desulfitation. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 497, 03020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.-R.; Li, M.-Y.; Cheng, Z.-Y.; Liu, X.-Y.; Yang, H.; Li, M.-T.; He, R.-Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, X.-H. Effects of Different Drying Methods on Drying Characteristics and Quality of Small White Apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.). Agriculture 2024, 14, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Yi, X.; Xiao, H.; Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Tang, Z.; Hu, C.; Li, X. Effects of Different Drying Methods on Drying Characteristics, Microstructure, Quality, and Energy Consumption of Apricot Slices. Foods 2024, 13, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Sylvain Tiliwa, E.; Yan, W.; Roknul Azam, S.M.; Wei, B.; Zhou, C.; Ma, H.; Bhandari, B. Recent development in high quality drying of fruits and vegetables assisted by ultrasound: A review. Food Res. Int. 2022, 152, 110744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karabulut, I.; Bilenler, T.; Sislioglu, K.; Gokbulut, I.; Ozdemir, I.S.; Seyhan, F.; Ozturk, K. Chemical composition of apricots affected by fruit size and drying methods. Dry. Technol. 2018, 36, 1937–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Zhu, L.; Geng, Z.; Liu, X.; Cheng, Z.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, X. Sea Buckthorn Pretreatment, Drying, and Processing of High-Quality Products: Current Status and Trends. Foods 2023, 12, 4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadivambal, R.; Jayas, D.S. Changes in quality of microwave-treated agricultural products—A review. Biosyst. Eng. 2007, 98, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayran, S.; Doymaz, İ. Infrared Drying and Effective Moisture Diffusivity of Apricot Halves: Influence of Pretreatment and Infrared Power. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, e12827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, F. Recent Applications and Potential of Infrared Dryer Systems for Drying Various Agricultural Products: A Review. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2020, 20, 586–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, K.; Strnad, C.; Bowman, P.; Young, K.; Kroll, E.; DeBruine, A.; Knudson, I.; Navin, M.; Cheng, Q.; Swedish, M.; et al. Validation of a Passive Solar Drying System Using Pineapple. Foods 2024, 13, 3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingham, J.; Kanungo, M.; Beauchamp, B.; Korbut, M.; Swedish, M.; Navin, M.; Zhang, W. Validation of Solar Dehydrator for Food Drying Applications: A Granny Smith Apple Study. J. Chem. Eng. Res. Updates 2022, 9, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lv, M.; Du, H.; Deng, H.; Zhou, L.; Li, P.; Li, X.; Li, B. Effect of Preliminary Treatment by Pulsed Electric Fields and Blanching on the Quality of Fried Sweet Potato Chips. Foods 2023, 12, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardini, M. Phenolic Compounds in Food: Characterization and Health Benefits. Molecules 2022, 27, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, X.; Meng, Z.; Dong, T.; Fan, X.; Wang, Q. Enzymatic browning and polyphenol oxidase control strategies. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2023, 81, 102921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. Recent Advances of Polyphenol Oxidases in Plants. Molecules 2023, 28, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakourou, M.C.; Taoukis, P.S. Effect of Alternative Preservation Steps and Storage on Vitamin C Stability in Fruit and Vegetable Products: Critical Review and Kinetic Modelling Approaches. Foods 2021, 10, 2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgailani, I.E.H.; Elkareem, M.A.M.G.; Noh, E.A.A.; Adam, O.E.A.; Alghamdi, A.M.A. Comparison of Two Methods for The Determination of Vitamin C (Ascorbic Acid) in Some Fruits. Am. J. Chem. 2017, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calín-Sánchez, Á.; Lipan, L.; Cano-Lamadrid, M.; Kharaghani, A.; Masztalerz, K.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A.; Figiel, A. Comparison of Traditional and Novel Drying Techniques and Its Effect on Quality of Fruits, Vegetables and Aromatic Herbs. Foods 2020, 9, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture. Commodity Specification for Dried Fruit. Available online: https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/CommoditySpecificationDriedFruitAugust%202019.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Health Organization. General Standard for Dried Fruits. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/hu/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCXS%2B360-2020%252FCXS_360e.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Wang, H.; Iqbal, A.; Murtaza, A.; Xu, X.; Pan, S.; Hu, W. A Review of Discoloration in Fruits and Vegetables: Formation Mechanisms and Inhibition. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 6478–6499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, R.; Nawaz, R.; Nasreen, R.; Fatima, N.; Siddique, R.; ur Raheem, M.I.; Hassan, M. Postharvest Management and Chemical Treatments for Apricot Preservation in Pakistan. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2023, 4, 1116–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, K.; Horie, A.; Nakabayashi, M.; Nishimura, K.; Yasunobu, T. Influence of processing conditions of atmospheric freeze-drying/low-temperature drying on the drying kinetics of sliced fruits and their vitamin C retention. J. Agric. Food Res. 2021, 6, 100231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkun, N.; Sarıtaş, S.; Jaouhari, Y.; Bordiga, M.; Karav, S. The Impact of Freeze Drying on Bioactivity and Physical Properties of Food Products. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, H.M.; Ozkan, K.; Ozturkcan, A.; Sagdic, O.; Gunes, E.; Karadag, A. Effect of drying methods on free and bound phenolic compounds, antioxidant capacities, and bioaccessibility of Cornelian cherry. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 2461–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.M.; Masoodi, F.A.; Haq, E.; Ahmad, M.; Ganai, S.A. Influence of processing methods and storage on phenolic compounds and carotenoids of apricots. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 132, 109846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yara North America. Available online: https://www.yara.us/crop-nutrition/citrus/managing-total-soluble-solids/ (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Valero, D.; Serrano, M. Growth and ripening stage at harvest modulates postharvest quality and bioactive compounds with antioxidant activity. Stewart Postharvest Rev. 2013, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, C.M. Effect of Temperature on Soluble Solids Content in Strawberry in Queensland, Australia. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béjar-Grimalt, J.; Pérez-Guaita, D.; Sánchez-Illana, Á.; García-Contreras, R.; Kataria, R.; Bureau, S.; de la Guardia, M.; Cadet, F. Classification of Apricot Varieties by Infrared Spectroscopy and Machine Learning. ACS Agric. Sci. Technol. 2025, 5, 1373–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhter, N.; Majid, D.; Rather, J.A.; Makroo, H.A.; Dar, B.N.; Manzoor, N. Development of functional apricot pulp powder: A sustainable approach to prevent post-harvest loss. Food Humanit. 2025, 5, 100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).