Chemical Composition and Biological Activity of Extracts from the Aerial Parts of Epilobium parviflorum Schreb.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Experimental Design and Workflow

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Solid–Liquid Extraction

2.2.2. Biphasic System Extraction

2.2.3. UPLC-DAD Analyses

2.2.4. LC-HRMS Analyses

2.2.5. POP Inhibition Assay

2.2.6. FAP Inhibition Assay

2.2.7. Molecular Docking

2.2.8. Antioxidant Potential

- Ac—absorbance of control solution of the corresponding ROS in methanol (or other solvent).

- As—absorbance of the solution containing both ROS and the extract in a given concentration.

DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay (DPPH●)

Scavenging of Superoxide Anion Radical (O2•−) (NBT Test)

ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity (ABTS+●)

2.2.9. Cells Culturing

2.2.10. Flow Cytometric Analysis of the Cell Cycle

2.2.11. Flow Cytometric Analysis of Apoptosis

2.2.12. Alkaline Comet Assay

2.2.13. Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Extractions and UPLC-DAD Analyses

3.2. Chemical Composition of the Extracts

3.2.1. Hydroxybenzoic Acids and Derivatives

3.2.2. Ellagic Acid and Derivatives

3.2.3. Hydroxycinnamic Acids and Derivatives

3.2.4. Hydrolyzable Gallotannins

3.2.5. Hydrolyzable Ellagitannins

3.2.6. Coumarins

3.2.7. Flavonoids and Derivatives

3.2.8. Sesquiterpenoids

3.2.9. Pentacyclic Triterpenoid Derivatives

3.2.10. Fatty Acids

3.2.11. Polyalcohol

3.2.12. Other Compounds

3.2.13. Nitrogen-Containing Compounds

3.3. Enzymes Inhibition Assays

3.4. Ligand-Protein Docking

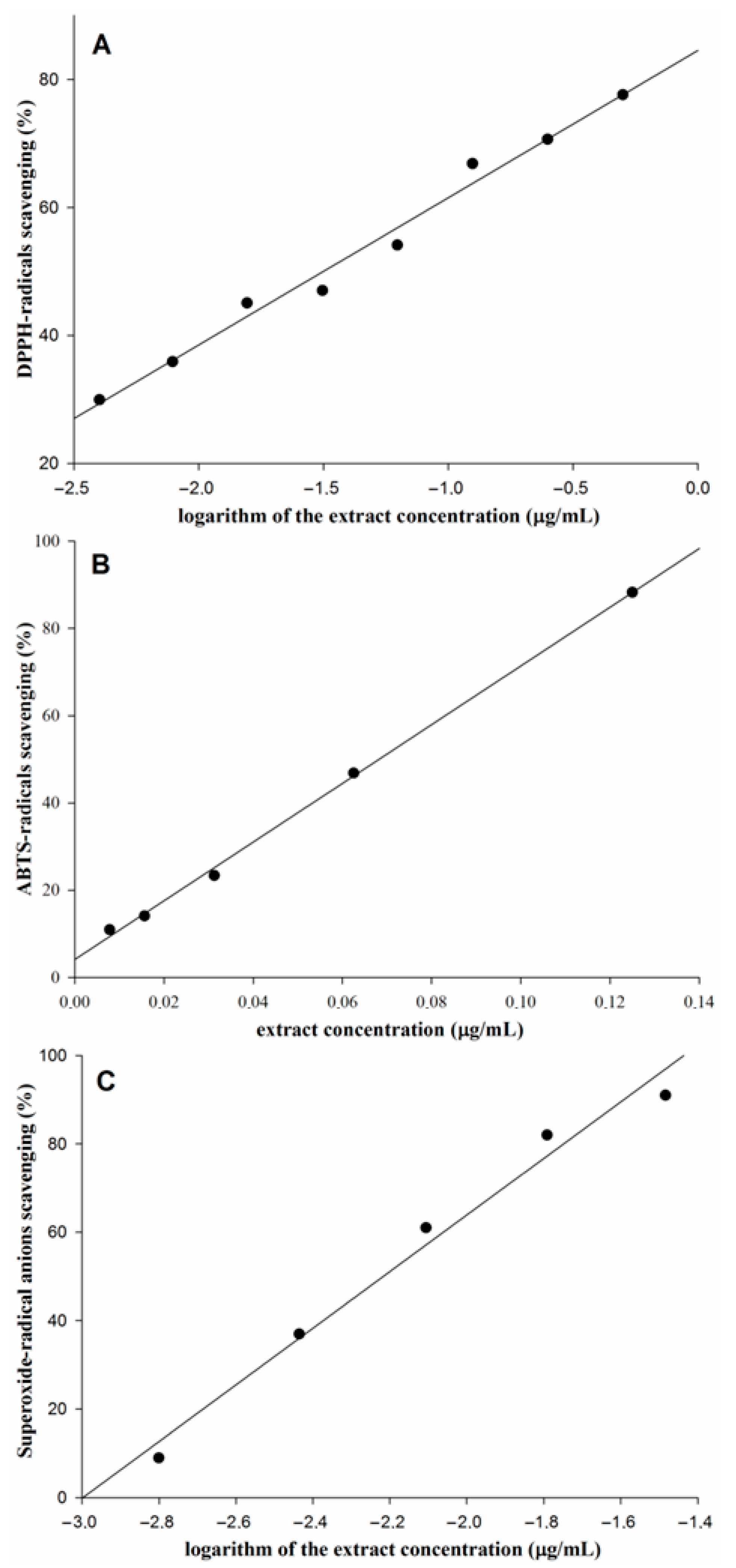

3.5. Antioxidant Activity of the 80% Ethanol Extract

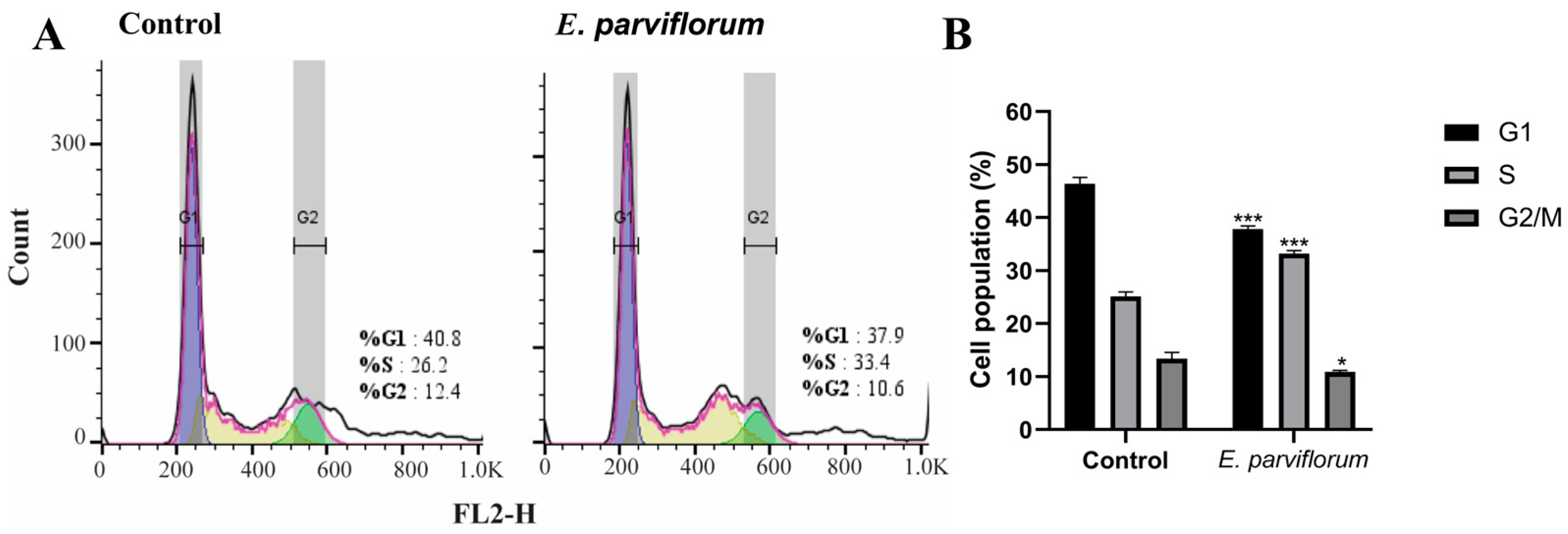

3.6. Cell Cycle Analysis

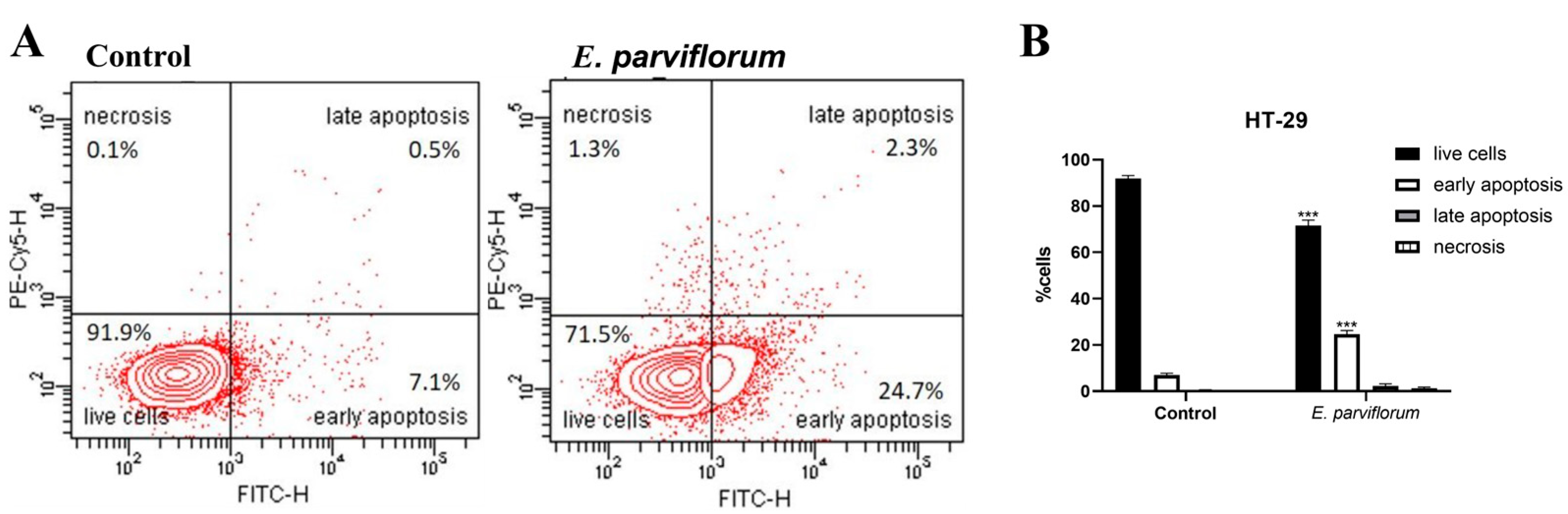

3.7. Apoptosis Assay

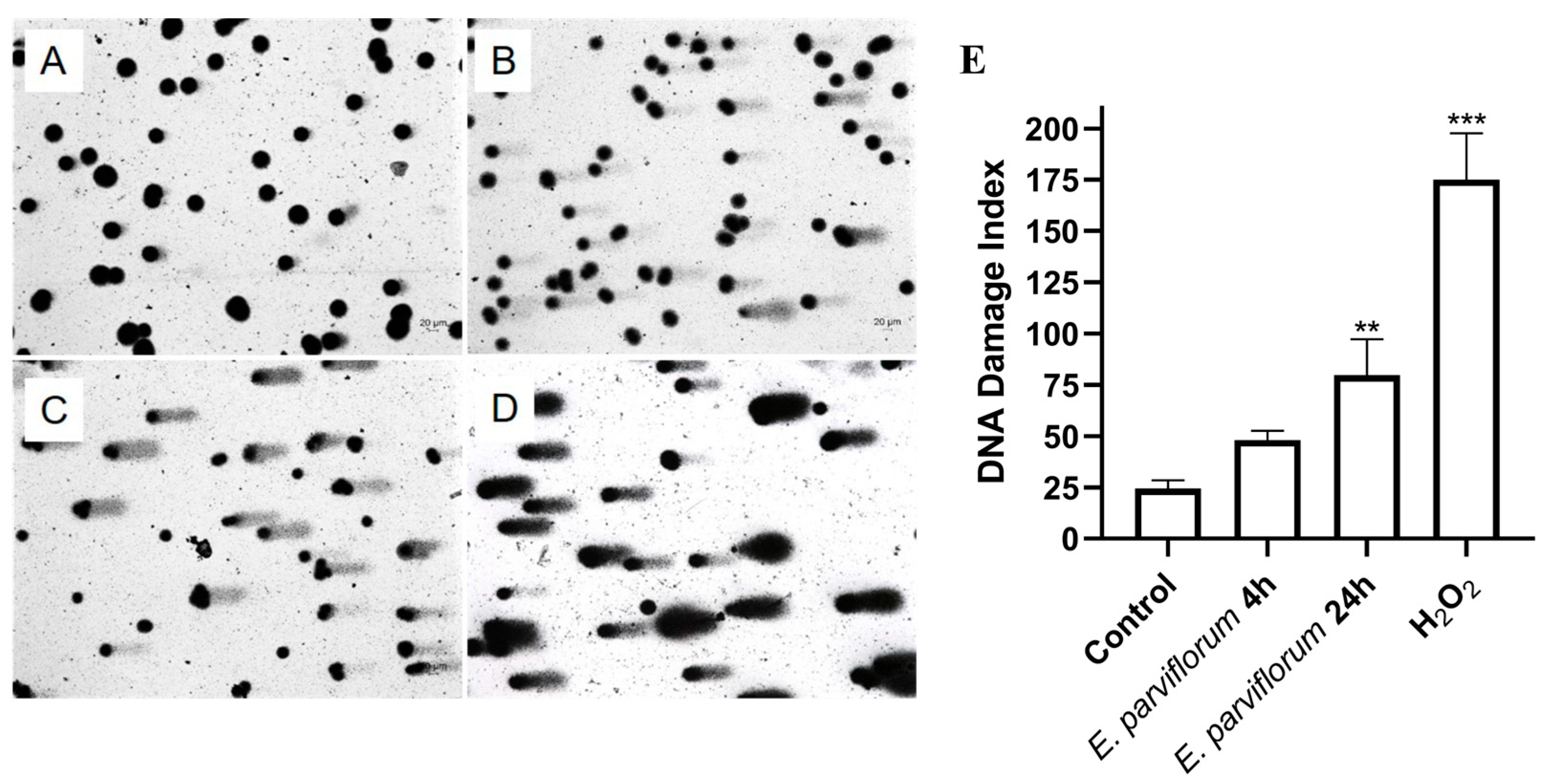

3.8. Comet Assay of DNA Damage Detection

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABTS | 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| AMC | 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin |

| DPPH• | 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| EDTA | ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| ESI | Electrospray Ionization |

| ESI/MS | Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry |

| FAP | Fibroblast Activation Protein alpha |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| HCD | Higher Energy Collision Dissociation |

| HHDPA | Hexahydroxydiphenic acid |

| HRMS-ESI | High Resolution Mass Spectrometry with Electrospray Ionization |

| IC50 | Fifty Percent Inhibitory Concentration |

| LC | Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry |

| MS | Mass Spectrometry |

| NBT | nitro blue tetrazolium chloride |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered Saline |

| POP | Prolyl Oligopeptidase |

| PPSPs | Post-Proline Specific Peptidases |

| RDA | Retro-Diels-Alder |

| rhFAP | Recombinant Human Fibroblast Activation Protein α |

| rhPOP | Recombinant Human Prolyl Oligopeptidase |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RP | Reverse-phase |

| RP-UPLC | Reverse-phase Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| RT | Retention Time |

| SC50 | Concentration of Extract that Scavenged 50% of the Concentration of the Radicals |

| TIC | Total Ion Current |

| UPLC-DAD | Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography Diode Array Detection |

| UV | Ultra Violet |

| Z-Gly-Pro-AMC | Benzyloxycarbonyl-glycyl-prolyl-4-methylcoumarin-7-amide |

References

- Thomson Healthcare. PDR for Herbal Medicines, 3rd ed.; Thomson PDR: Montvale, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Granica, S.; Piwowarski, J.P.; Czerwińska, M.E.; Kiss, A.K. Phytochemistry, pharmacology and traditional uses of different Epilobium species (Onagraceae): A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 156, 316–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevesi, B.T.; Houghton, P.J.; Habtemariam, S.; Kéry, Á. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Epilobium parviflorum Schreb. Phytother. Res. 2009, 23, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevesi Tóth, T.; Blazics, B.; Kéry, Á. Polyphenol Composition and Antioxidant Capacity of Epilobium Species. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2009, 49, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiermann, A.; Juan, H.; Sametz, W. Influence of Epilobium Extracts on Prostaglandin Biosynthesis and Carrageenin-Induced Oedema of the Rat Paw. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1986, 17, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatefi, K.B.; Kazemi, N.S.; Vaezi, K.M.R. The extracts of Epilobium parviflorum inhibit MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Iran. J. Toxicol. 2021, 15, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakou, S.; Tragkola, V.; Paraskevaidis, I.; Plioukas, M.; Trafalis, D.T.; Franco, R.; Pappa, A.; Panayiotidis, M.I. Chemical characterization and biological evaluation of Epilobium parviflorum extracts in an in vitro model of human malignant melanoma. Plants 2023, 12, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbudak, M.A.; Sut, T.; Eruygur, N.; Akinci, E. Antiproliferative effect of Epilobium parviflorum extracts on colorectal cancer cell line HT-29. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2021, 26, 3120–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulikovska, I.; Ivanova, E.; Ivanov, I.; Tasheva, D.; Dimitrova, M.; Nikolova, B.; Iliev, I. Study on the phototoxicity and antitumor activity of plant extracts from Tanacetum vulgare L., Epilobium parviflorum Schreb., and Geranium sanguineum L. Int. J. Bioautom. 2023, 27, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remmel, I.; Raal, A.; Püssa, T.; Sõukand, R. Phenolic Compounds in Five Epilobium Species Collected from Estonia. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2012, 7, 1323–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlase, A.-M.; Deliu, I.; Bodoki, E.; Fritea, L.; Gheldiu, A.-M.; Săplăcan, R.; Toiu, A.; Tămaș, M.; Benedec, D. Epilobium Species: From Optimization of the Extraction Process to Evaluation of Biological Properties. Plants 2022, 12, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazargani, M.M.; Falahati-Anbaran, M.; Rohloff, J. Comparative analysis of phytochemical variation within and between congeneric species of willow herb Epilobium hirsutum and E. parviflorum: Contribution of environmental factors. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 595190. [Google Scholar]

- Larrinaga, G.; Perez, I.; Blanco, L.; Sanz, B.; Errarte, P.; Beitia, M.; Etxezarraga, M.C.; Loizate, A.; Gil, J.; Irazusta, J.; et al. Prolyl endopeptidase activity is correlated with colorectal cancer prognosis. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 11, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, K.W.; Christiansen, V.J.; Yadav, V.R.; Silasi-Mansat, R.; Lupu, F.; Awasthi, V.; Zhang, R.R.; McKee, P.A. Suppression of tumor growth in mice by rationally designed pseudopeptide inhibitors of fibroblast activation protein and prolyl oligopeptidase. Neoplasia 2015, 17, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dicrassin Ltd. and Bilkolechenie.bg. Available online: https://bilkolechenie.bg/ (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- HBH (Bulgaria). Alin® Brand. Available online: https://alinbg.com/ (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Ivanov, I.; Vasileva, A.; Tasheva, D.; Dimitrova, M. Isolation and characterization of natural inhibitors of post-proline specific peptidases from the leaves of Cotinus coggygria Scop. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 314, 116508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aertgeerts, K.; Levin, I.; Shi, L.; Snell, G.P.; Jennings, A.; Prasad, G.S.; Zhang, Y.; Kraus, M.L.; Salakian, S.; Sridhar, V.; et al. Structural and kinetic analysis of the substrate specificity of human fibroblast activation protein α. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 19441–19444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffner, C.D.; Diaz, C.J.; Miller, A.B.; Reid, R.A.; Madauss, K.P.; Hassell, A.; Hanlon, M.H.; Porter, D.J.; Becherer, J.D.; Carter, L.H. Pyrrolidinyl pyridone and pyrazinone analogues as potent inhibitors of prolyl oligopeptidase (POP). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 4360–4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcule Online Platform. Mcule Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA. Available online: https://mcule.com (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock 4 and AutoDock Tools 4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient opti-mization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer. Available online: https://discover.3ds.com/discovery-studio-visualizer-download (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. Lebensm. Wiss. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, C.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: Improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 1971, 44, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raynova, Y.; Marchev, A.; Doumanova, L.; Pavlov, A.; Idakieva, K. Antioxidant activity of Helix aspersa maxima (gastro-pod) hemocyanin. Acta Microbiol. Bulg. 2015, 31, 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, K.D.; Kato, T.A. Alkaline Comet Assay to Detect DNA Damage. In Chromosome Analysis; Gotoh, E., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Volume 2519, pp. 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Nadin, S.B.; Vargas-Roig, L.M.; Ciocca, D.R. A silver staining method for single-cell gel assay. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2001, 49, 1183–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noroozi, M.; Angerson, W.J.; Lean, M.E.J. Effects of flavonoids and Vitamin C on oxidative DNA damage to human lymphocytes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 67, 1210–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batten, J.; Cock, I.E. Antibacterial Activity and Toxicity Profiles of Epilobium parviflorum (Schreb.) Schreb. Extracts and Conventional Antibiotics against Bacterial Triggers of Some Autoimmune Diseases. Pharm. Commun. 2023, 13, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şachir, E.E.; Raftu, G.; Badea, F.C.; Caraiane, A.; Badea, V. Local Toxicity of Dry Vegetable Extract from the Epilobium parviflorum Schreb. Tested on Extracted Tooth Socket of Albino Wistar Rat. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2020, 24, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Oreopoulou, A.; Tsimogiannis, D.; Oreopoulou, V. Extraction of polyphenols from aromatic and medicinal plants: An overview of the methods and the effect of extraction parameters. In Polyphenols in Plants: Isolation, Purification and Extract Preparation, 2nd ed.; Watson, R.R., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2019; pp. 243–259. [Google Scholar]

- Yisimayili, Z.; Guo, X.; Liu, H.; Xu, Z.; Abdulla, R.; Aisa, H.A.; Huang, C. Metabolic profiling analysis of corilagin in vivo and in vitro using high-performance liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 165, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaniya, A. Spectrum VF-NPL-QEHF012271 Presented in MassBank of North America. Available online: https://mona.fiehnlab.ucdavis.edu/spectra/display/VF-NPL-QEHF012271 (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Wang, J.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Lin, R. Analysis of chemical constituents of melastoma do-decandrum lour. By uplc-esi-q-exactive focus-ms/ms. Molecules 2017, 22, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espín, S.; Gonzalez-Manzano, S.; Taco, V.; Poveda, C.; Ayuda-Durán, B.; Gonzalez-Paramas, A.M.; Santos-Buelga, C. Phenolic composition and antioxidant capacity of yellow and purple-red Ecuadorian cultivars of tree tomato (Solanum betaceum Cav.). Food Chem. 2016, 194, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.M.; Fu, Y.; Yu, W.J.; Chen, C.; Di, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhai, Y.J.; Chu, Z.Y.; Kang, T.G.; Chen, H.B. Identification of Polar Constituents in the Decoction of Juglans mandshurica and in the Medicated Egg Prepared with the Decoction by HPLC-Q-TOF MS2. Molecules 2017, 22, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granica, S.; Bazylko, A.; Kiss, A.K. Determination of macrocyclic ellagitannin oenothein B in plant materials by HPLC-DAD-MS: Method development and validation. Phytochem. Anal. 2012, 23, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarczyk, M.; Naruszewicz, M.; Kiss, A.K. Extracts from Epilobium sp. herbs induce apoptosis in human hor-mone-dependent prostate cancer cells by activating the mitochondrial pathway. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2013, 65, 1044–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnieszka, G.; Mariola, D.; Anna, P.; Piotr, K.; Natalia, W.; Aneta, S.; Marcin, O.; Bogna, O.; Zdzisław, Ł.; Aurelia, P.; et al. Qualitative and quantitative analyses of bioactive compounds from ex vitro Chamaenerion angustifolium (L.) (Epilobium augustifolium) herb in different harvest times. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 123, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablajan, K.; Abliz, Z.; Shang, X.Y.; He, J.M.; Zhang, R.P.; Shi, J.G. Structural characterization of flavonol 3,7-di-O-glycosides and determination of the glycosylation position by using negative ion electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 2006, 41, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.L.; Xu, F.; Guo, X.Y.; Zhang, J.; Ly, Y.; Wang, P.P.; Wang, S.Q.; Min, J.G.; et al. Chemical profiling of Sanjin tablets and exploration of their effective substances and mechanism in the treatment of urinary tract infections. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1179956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levison, B.S.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Z.; Fu, X.; DiDonato, J.A.; Hazen, S.L. Quantification of fatty acid oxidation products using online high-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 59, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludovici, M.; Ialongo, C.; Reverberi, M.; Beccaccioli, M.; Scarpari, M.; Scala, V. Quantitative profiling of oxylipins through comprehensive LC-MS/MS analysis of Fusarium verticillioides and maize kernels. Food Addit. Contam. 2014, 31, 2026–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noleto-Dias, C.; Picoli, E.A.D.T.; Porzel, A.; Wessjohann, L.A.; Tavares, J.F.; Farag, M.A. Metabolomics characterizes early metabolic changes and markers of tolerant Eucalyptus ssp. clones against drought stress. Phytochemistry 2023, 212, 113715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.C.; Deng, L.Q.; Guo, X.; Xiao, G.J.; Jiang, Y.B.; Wang, G.W.; Liao, Z.H.; Chen, M. Angustifoline A, A New Alkaloid from Epilobium angustifolium. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2021, 57, 903–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landzhev, I. Encyclopedia of Medicinal Plants in Bulgaria; Publishing House Trud: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2010. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar]

- Dunaevsky, Y.E.; Tereshchenkova, V.F.; Oppert, B.; Belozersky, M.A.; Filippova, I.Y.; Elpidina, E.N. Human proline specific peptidases: A comprehensive analysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2020, 1864, 129636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharin, A.; Ting, T.Y.; Goh, H.H. Post-proline cleaving enzymes (PPCEs): Classification, structure, molecular proper-ties, and applications. Plants 2022, 11, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plescia, J.; Hédou, D.; Pousse, M.E.; Labarre, A.; Dufresne, C.; Mittermaier, A.; Moitessier, N. Modulating the selectivity of inhibitors for prolyl oligopeptidase inhibitors and fibroblast activation protein-α for different indications. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 240, 114543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Jun, M.; Choi, J.Y.; Yang, E.J.; Hur, J.M.; Bae, K.; Seong, Y.H.; Huh, T.L.; Song, K.S. Plant phenolics as prolyl endopeptidase inhibitors. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2007, 30, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fülöp, V.; Böcskei, Z.; Polgár, L. Prolyl oligopeptidase: An unusual β-propeller domain regulates proteolysis. Cell 1998, 94, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirigotaki, A.; Elzen, R.V.; Veken, P.V.D.; Lambeir, A.M.; Economou, A. Dynamics and ligand-induced conformational changes in human prolyl oligopeptidase analyzed by hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niazi, S.K.; Mariam, Z. Computer-aided drug design and drug discovery: A prospective analysis. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adelusi, T.I.; Oyedele, A.Q.; Boyenle, I.D.; Ogunlana, A.T.; Adeyemi, R.O.; Ukachi, C.D.; Idris, M.O.; Olaoba, O.T.; Adedotun, I.O.; Kolawole, O.E.; et al. Molecular modeling in drug discovery. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2022, 29, 100880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, V.; Karonen, M. Partition coefficients (logP) of hydrolysable tannins. Molecules 2020, 25, 3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Boiti, A.; Vallone, D.; Foulkes, N.S. Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling and Oxidative Stress: Transcriptional Regulation and Evolution. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziech, D.; Franco, R.; Pappa, A.; Panayiotidis, M.I. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)—Induced genetic and epigenetic alterations in human carcinogenesis. Mutat. Res. Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2011, 711, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudrapal, M.; Khairnar, S.J.; Khan, J.; Dukhyil, A.B.; Ansari, M.A.; Alomary, M.N.; Alshabrmi, F.M.; Palai, S.; Deb, P.K.; Devi, R. Dietary Polyphenols and Their Role in Oxidative Stress-Induced Human Diseases: Insights Into Protective Effects, Antioxidant Potentials and Mechanism(s) of Action. Front Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 806470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiss, A.K.; Bazylko, A.; Filipek, A.; Granica, S.; Jaszewska, E.; Kiarszys, U.; Kośmider, A.; Piwowarski, J. Oenothein B’s contribution to the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity of Epilobium sp. Phytomedicine 2011, 18, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulcin, İ.; Alwasel, S.H. DPPH radical scavenging assay. Processes 2023, 11, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyasov, I.R.; Beloborodov, V.L.; Selivanova, I.A. Three ABTS•+ radical cation-based approaches for the evaluation of antioxidant activity: Fast-and slow-reacting antioxidant behavior. Chem. Pap. 2018, 72, 1917–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulikovska, I.; Georgieva, A.; Djeliova, V.; Todorova, K.; Vasileva, A.; Ivanov, I.; Dimitrova, M. Anticancer Activity of Ethyl Acetate/Water Fraction from Tanacetum vulgare L. Leaf and Flower Extract. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitalone, A.; Allkanjari, O. Epilobium spp.: Pharmacology and Phytochemistry. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 1229–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.; Xiao, J.; Wei, G.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, F.; Xiong, Z.; Lu, L.; Wang, X.; Pang, G.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Oenothein B inhibits human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cell proliferation by ROS-mediated PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2019, 25, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Step | Extract/Sample | Method/Assay | Purpose/Objective |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aerial parts from two Bulgarian regions | Preparation of extracts: 80% methanol, 80% ethanol, 85% isopropanol, 80% acetonitrile, ethyl acetate/water, 3-pentanone/water | Generate diverse extracts for yield evaluation |

| 2 | 80% ethanol extracts from two regions | UPLC-DAD | Compare chromatographic profiles from different geographic origins |

| 3 | Selected extracts (80% ethanol and ethyl acetate/water) | LC-HRMS (negative ionization) | Identify phytochemical compounds (nonvolatile compounds) |

| 4 | All extracts | MS and MS/MS data analyses | Identify all the registered compounds |

| 5 | 80% ethanol and ethyl acetate/water extracts | Enzyme inhibition assays | Evaluate inhibition of post-proline-specific peptidases (POP, FAP) |

| 5 | Oenothein B (from extract) | Molecular docking | Predict binding to POP and FAP enzymes |

| 6 | 80% ethanol extract (selected) | Antioxidant assays: ABTS, DPPH, NBT | Assess antioxidant potential |

| 7 | 80% ethanol extract | Cell-based assays in HT-29 cells: cell cycle distribution, apoptosis, genotoxicity | Investigate mechanisms underlying antitumor activity |

| Extract | Extraction Solvent | Temperature (°C) | Yield | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (g) | (%) | |||

| M | 80% methanol | r.t. | 0.475 ± 0.015 | 9.5 ± 0.3 a |

| E | 80% ethanol | r.t. | 0.706 ± 0.026 | 14.1 ± 0.35 b |

| Ea a | 80% ethanol | r.t. | 0.625 ± 0.015 | 12.5 ± 0.2 c |

| I | 85% isopropanol | r.t. | 0.421 ± 0.022 | 8.4 ± 0.4 d |

| N | 80% acetonitrile | r.t. | 0.852 ± 0.031 | 17.0 ± 0.5 e |

| AW | Ethyl acetate/water | r.t. | 0.158 ± 0.008 | 3.2 ± 0.1 f |

| PW | 3-pentanone/water | 60 | 0.110 ± 0.005 | 2.2 ± 0.05 g |

| Peak | RT (min) | Experimental m/z Error (ppm) | Molecular Formula | MS/MS Fragments m/z, (R.I., %) | Proposed Compound | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.64 | 181.0709 (−4.37) | C6H14O6 | - | Hexan-1,2,3,4,5,6-hexol | AW, E, I, M, N, PW |

| 2 | 0.80 | 331.0674 (1.12) | C13H16O10 | 211.0244 (9), 169.0129 (85), 151.0026 (5), 125.0232 (100), 124.0154 (32), 123.0075 (16) | O-Galloylglucose | E, Ea, I, M, N |

| 3 | 1.18 | 169.0132 (−6.01) | C7H6O5 | 125.0232 (100), 124.0154 (33), 123.0075 (30) | Gallic acid | AW, E, Ea, I, M, N, PW |

| 4 | 1.61 | 633.0740 (1.11) | C27H22O18 | 300.9992 (100.00), 275.0201 (56), 257.0094 (7), 249.0405 (24), 247.0251 (5), 231.0295 (14), 229.0137 (5), 203.0344 (6), 169.0132 (18), 125.0230 (8), 123.0074 (5) | Galloyl-HHDP-glucose | E, I |

| 5 | 2.36 | 153.0182 (−7.07) | C7H6O4 | - | Dihydroxybenzoic acid (isomer I) | PW |

| 6 | 2.95 | 137.0232 (−8.96) | C7H6O3 | - | Hydroxybenzoic acid (isomer I) | AW |

| 7 | 3.57 | 285.0618 (0.73) | C12H14O8 | 153.0180 (100) | Dihydroxybenzoyl pentose | E, Ea, I, M, N |

| 8 | 3.64 | 183.0291 (−4.63) | C8H8O5 | 181.0136 (20), 169.0135 (15), 153.0183 (33), 139.0026 (32), 125.0240 (18), 124.0155 (100), 123.0075 (91) | 3,4-Dihydroxy-5-methoxybenzoic acid (3-O-Methylgallic acid) | AW |

| 9 | 3.77 | 137.0232 (−8.96) | C7H6O3 | - | Hydroxybenzoic acid (isomer II) | PW |

| 10 | 4.41 | 153.0182 (−7.07) | C7H6O4 | - | Dihydroxybenzoic acid (isomer II) | PW |

| 11 | 5.27 | 179.0341 (−4.81) | C9H8O4 | 135.0440 (100), 134.0361 (64), 133.0283 (43), 117.0336 (27) | Caffeic acid | AW |

| 12 | 5.43 | 295.0460 (0.27) | C13H12O8 | 163.0390 (22), 161.0234 (9), 133.0283 (3), 119.0489 (100), 117.0333 (12) | p-Coumaroyltartaric acid (coutaric acid) | E, I, M |

| 13 | 5.70 | 1567.1446 (−0.02) 783.0701 [M-2H]2− | C68H48O44 | 765.0568 (7), 613.0427 (5), 597.0533 (6), 472.9778 (5), 450.9950 (16), 445.0413 (6), 427.0304 (8), 425.0150 (5), 399.0354 (5), 300.9989 (100), 299.9906 (17), 298.9835 (20), 275.0199 (67), 273.0045 (33), 247.0249 (45), 245.0091 (11), 231.0295 (30), 229.0139 (15), 169.0132 (32), 125.0230 (13), 123.0074 (16) | Oenothein B | AW, E, Ea, I, M, N |

| 14 | 5.79 | 177.0184 (−5.16) | C9H6O4 | 149.0233 (21), 148.0153 (80), 133.0283 (100), 132.0204 (19), 121.0285 (5) | 6,7-Dihydroxycoumarin (Aesculetin, Esculetin) | PW |

| 15 | 6.26 | 179.0341 (−4.81) | C9H8O4 | 177.0184 (11), 151.0386 (6), 150.0350 (7), 149.0230 (12), 135.0440 (62), 134.0360 (49), 133.0283 (100.00), 132.0206 (18), 125.0234 (45), 121.0283 (13) | 6,7-dihydroxy-3,4-dihydrocoumarin | PW |

| 16 | 6.48 | 1567.1445 (−0.02) 783.0701 [M-2H]2− | C68H48O44 | 765.0568 (6), 613.0427 (5), 597.0533 (5), 472.9778 (5), 450.9950 (14), 445.0413 (5), 427.0308 (7), 425.0150 (5), 399.0354 (5), 300.9989 (100), 299.9906 (19), 298.9835 (20), 275.0199 (66), 273.0045 (33), 247.0249 (44), 245.0091 (10), 231.0295 (32), 229.0139 (15), 169.0132 (36), 125.0230 (11), 123.0074 (10) | Oenothein B (isomer I) | E, Ea, I, M, N |

| 17 | 325.0567 (0.69) | C14H14O9 | 193.0498 (45), 191.0343 (43), 189.0185 (32), 163.0392 (20), 149.0590 (5), 135.0425 (7), 134.0360 (100 ), 133.0282 (14) | Feruloyltartaric acid (fertaric acid) | E, Ea, I, M | |

| 18 | 7.64 | 1567.1445 (−0.02) 783.0701 [M-2H]2− | C68H48O44 | 765.0567 (5), 613.0428 (5), 597.0527 (5), 472.9776 (5), 450.9950 (18), 445.0414 (5), 427.0311 (8), 425.0150 (5), 399.0353 (5), 300.9989 (100), 299.9905 (18), 298.9836 (20), 275.0199 (67), 273.0045 (33), 247.0249 (42), 245.0091 (11), 231.0295 (28), 229.0139 (15), 169.0132 (40), 125.0230 (5), 123.0074 (5) | Oenothein B (isomer II) | E, Ea, I, M |

| 19 | 8.04 | 163.0390 (−6.00) | C9H8O3 | 145.0282 (7), 135.0440 (11), 119.0489 (100) | p-Coumaric acid | AW |

| 20 | 8.19 | 392.0387 [M-H]•− (0.56) | C17H14O11 | 223.0243 (5), 211.0237 (9), 193.0134 (8), 169.0132 (100), 151.0025 (8), 125.0231 (81), 123.0074 (36) | 3-Galloyloxy-2-oxopropyl gallate (1,3-Digalloyoxyacetone) | E, Ea, I |

| 21 | 8.74 | 225.1129 (−1.25) | C12H18O4 | 159.0442 (37), 151.0384 (49), 149.0233 (100), 147.0804 (54), 133.0648 (29) | 2-[hydroxypentenyl]-3-oxo-cyclopentyl]acetic acid | PW |

| 22 | 9.14 | 163.0390 (−6.00) | C9H8O3 | 119.0489 (100) | Hydroxycinnamic acid | PW |

| 23 | 10.01 | 631.0947 (−1.04) | C28H24O17 | 479.0838 (5), 317.0280 (28), 316.0226 (100), 287.0199 (7), 275.0198 (9), 271.02526 (14), 270.0173 (5), 247.0250 (5), 178.99751 (5), 169.0132 (12), 151.0024 (5), 125.0230 (5) | Myricetin-3-O-(O-galloyl)-glucopyranoside | AW, E, Ea, I, M, N, PW |

| 24 | 10.90 | 479.0832 (0.22) | C21H20O13 | 317.0274 (11), 316.0226 (46), 287.0201 (65), 271.0251 (100), 270.0173 (15), 259.0248 (18), 242.0218 (15), 214.0267 (17), 178.9974 (6), 151.0022 (10), 137.0232 (5) | Myricetin-3-O-glucoside | AW, E, Ea, I, M, N, PW |

| 25 | 12.04 | 433.0413 (0.16) | C19H14O12 | 300.9991 (100), 299.9917 (74), 283.9965 (8), 282.9889 (7), 273.0041 (7), 257.0088 (5), 245.0092 (6), 229.0136 (10), 228.0064 (7), 216.0061 (9), 200.0108 (6) | Ellagic acid pentoside | E, Ea, I, M, N |

| 26 | 313.1297 (1.45) | C15H22O7 | 229.0141 (100), 173.0235 (26), 157.0283 (11), 149.0596 (24) | Unidentified | E, I, M | |

| 27 | 12.26 | 497.3344 (0.10) | C25H46N4O6 | 451.3308 (10), 433.3195 (14), 333.2305 (38), 324.2669 (18), 265.1482 (39), 242.1874 (27), 225.1607 (68), 224.1767 (100), 207.1500 (65) | Unidentified | AW, E, Ea, I, M, N, PW |

| 28 | 12.66 | 300.9991 (0.30) | C14H6O8 | 283.9966 (21), 257.0098 (6), 245.0089 (13). 244.0009 (12), 229.0136 (14), 228.0059 (19), 217.0130 (17), 216.0060 (36), 201.0175 (23), 200.0107 (74), 199.0030 (35), 189.0187 (26), 185.0239 (17), 173.0232 (32), 172.0157 (63), 171.0078 (28), 163.0391 (30), 161.0234 (53), 160.0155 (41), 145.0283 (100.00), 144.0204 (30), 133.0283 (50), 132.0204 (42), 129.0333 (15) | Ellagic acid | AW, E, Ea, I, M, AW, E, |

| 29 | 463.0886 (0.91) | C21H20O12 | 317.0278 (14), 316.0228 (55), 287.0200 (65), 271.0251 (100), 270.0172 (14), 259,0250 (20), 243.0293 (10), 242.0219 (15), 214.0267 (18), 178.9970 (7), 151.0024 (12), 137.0232 (5) | Myricetin-3-O-rhamnoside (Myricitrin) | Ea, I, M, N, PW, N, PW | |

| 30 | 12.82 | 297.1346 (0.84) | C15H22O6 | 189.0185 (51), 177.0186 (17), 175.0395 (15), 161.0235 (100), 149.0229 (12), 133.0285 (94), 129.0332 (31) | Unidentified | E, I, M, N |

| 31 | 13.73 | 297.1346 (0.84) | C15H22O6 | 177.0183 (30), 175.0392 (51), 149.0233 (36), 133.0282 (100) | Unidentified | E, I, M, N |

| 32 | 13.92 | 297.1345 (0.63) | C15H22O6 | 177.0183 (14), 175.0392 (15), 161.0235 (100), 133.0281 (46) | Unidentified | E, I, M, N |

| 33 | 14.46 | 187.0968 (−4.07) | C9H16O4 | 141.0909 (100), 125.0959 (38), 123.0801 (17) | Nonanedioic acid (Azelaic acid) | AW, E, Ea, I, PW |

| 34 | 313.1297 (1.45) | C15H22O7 | 255.0300 (100), 227.0347 (86), 149.0596 (15) | Unidentified | E, I, M | |

| 35 | 15.20 | 297.1345 (0.63) | C15H22O6 | 177.0183 (34), 175.0393 (35), 149.0231 (19), 121.0282 (100) | Unidentified | E, I, M, N |

| 36 | 15.31 | 447.0935 (0.50) | C21H20O11 | 301.0336 (13), 300.0280 (29), 271.0254 (100), 255.0300 (48), 243.0299 (22), 227.0346 (10), 178.9980 (5), 163.0027 (6), 151.0025 (15) | Quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside (Quercitrin) | AW, E, Ea, I, N, PW |

| 37 | 16.17 | 317.0302 (−0.25) | C15H10O8 | 287.0189 (8), 271.0249 (26), 287.0208 (8), 259.0236 (5), 255.0296 (18), 243.0296 (8), 227.0345 (8), 178.9978 (16), 169.0134 (18), 151.0025 (72), 137.0232 (100), 123.0075 (6), 121.0284 (6) | Myricetin | AW, PW |

| 38 | 16.53 | 359.0775 (0.67) | C18H16O8 | 197.0447 (5), 179.0343 (8), 161.02345 (34), 135.0440 (69), 133.0284 (100), 132.0205 (31), 123.0439 (8) | Rosmarinic acid | AW, PW |

| 39 | 17.63 | 431.0985 (0.60) | C21H20O10 | 285.0401 (17), 284.0333 (17), 255.0300 (100), 227.0348 (84), 229.0510 (11) | Kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside | AW, PW |

| 40 | 18.16 | 711.3970 (−0.68) | C37H60O13 | 503.3386 (100), 485.3278 (19), 473.3263 (5), 453.3015 (10), 441.3412 (5), 421.3123 (5), 409.3109 (7) | 19-α-Hydroxyasiatic acid derivative (I) | AW, Ea, PW |

| 41 | 19.23 | 287.0565 (1.21) | C15H12O6 | 151.0390 (7), 151.0026 (16), 135.0440 (100) | Eriodictyol | AW, I, PW |

| 42 | 19.40 | 711.3970 (−0.68) | C37H60O13 | 503.3389 (100), 485.3277 (24), 459.3482 (5), 441.3412 (5) | 19-α-Hydroxyasiatic acid derivative (II) | AW, Ea, I, PW |

| 43 | 20.33 | 637.1782 (1.27) | C29H34O16 | 283.0613 (100), 268.0380 (49) | Acacetin-O-heptosylglucoside | E, I, M, N |

| 44 | 20.48 | 301.0355 (0.58) | C15H10O7 | 271.0259 (98), 255.0307 (19), 243.0299 (5), 227.0357 (5), 178.9984 (6), 151.0025 (100), 121.0282 (90) | Quercetin | AW |

| 45 | 20.58 | 285.0407 (0.87) | C15H10O6 | 227. 0356 (5), 175.0391 (8), 151.0026 (15), 145.0282 (9), 133.0283 (100), 132.0204 (45), 121.0282 (14) | Luteolin | AW |

| 46 | 24.25 | 327.2179 (0.71) | C18H32O5 | 239.1287 (6), 229.1448 (34), 221.1177 (12), 211.1337 (51), 209.1187 (10), 193.1225 (5), 185.1169, (8), 183.1387 (9), 181.1234 (5), 171.1018 (100), 165.1277 (47), 137.0962 (24), 135.0804 (12), 127.0752 (11) | 9,12,13-trihydroxyoctadeca-10,15-dienoic acid | AW, E, Ea, I, PW |

| 47 | 24.96 | 695.4022 (−0.37) | C38H56N4O8 | 487.3440 (100), 469.3331 (24) | Unidentified | AW, Ea, PW |

| 48 | 25.56 | 695.4022 (−0.37) | C38H56N4O8 | 487.3441 (100), 473.3286 (8) | Unidentified | AW, Ea, PW |

| 49 | 26.37 | 329.2337 (1.07) | C18H34O5 | 229.1449 (62), 211.1342 (100), 209.1181 (10), 183.1383 (17), 171.1022 (70), 165.1279 (51), 139.1116 (33), 137.0958 (10), 127.0752 (11) | 9,12,13-trihydroxyoctadec-10-enoic acid (isomer I) | AW, E, Ea, I, PW |

| 50 | 26.69 | 329.2336 (0.80) | C18H34O5 | 229.1458 (7), 211.1341 (27), 201.1125 (22), 171.1019 (100), 165.1276 (34), 155.1064 (28), 139.1114 (56) | 9,10,13- trihydroxyoctadec-11-enoic acid (isomer II) | AW, E, Ea, I, PW AW, E, Ea, I, PW |

| 51 | 343.0461 (0.49) | C17H12O8 | 328.0231 (5), 313.0000 (14), 297.9756 (34), 285.0038 (6), 269.9809 (100.00), 241.9856 (24), 213.9904 (33), 197.9950 (30), 185.9949 (45), 173.9950 (5), 169.9998 (7), 157.9997 (22), 145.9997 (5), 142.0048 (8), 130.0047 (11) | 2,3,8-Tri-O-methylellagic acid | ||

| 52 | 27.30 | 416.1618 (0.60) | C24H23N3O4 | 346.1571 (5), 319.1455 (6), 263.0829 (8), 249.0671 (80), 237.0668 (10), 222.0557 (5), 221.0716 (5), 220.0771 (5), 219.0557 (14), 196.0397 (20), 194.0603 (100) | Unidentified | AW |

| 53 | 27.71 | 287.2230 (0.76) | C16H32O4 | 201.1120 (31), 171.1019 (65), 155.1065 (16), 153.0908 (19), 137.0961 (22), 135.0804 (19), 125.0958 (100) | 9,10-Dihydroxyhexadecanoic acid | AW, PW |

| 54 | 28.54 | 213.0552 (−2.38) | C13H10O3 | 169.0654 (48), 135.0075 (100) | Unidentified | AW, PW |

| Extract | IC50 (μg/mL) | |

|---|---|---|

| POP | FAP | |

| 80% ethanol | 1.72 ± 0.02 | NI a |

| Ethyl acetate/water | NI b | NI a |

| Materials | SC50 µg/mL | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH | ABTS | NBT | |

| E. parviflorum extract | 27.7 ± 1.71 | 68.8 ± 2.69 | 5.7 ± 0.26 |

| Trolox | 12.11 ± 0.64 | 9.67 ± 1.15 | 23.21 ± 0.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dimitrova, M.; Sulikovska, I.; Tsvetanova, E.; Djeliova, V.; Vasileva, A.; Ivanov, I. Chemical Composition and Biological Activity of Extracts from the Aerial Parts of Epilobium parviflorum Schreb. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12109. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212109

Dimitrova M, Sulikovska I, Tsvetanova E, Djeliova V, Vasileva A, Ivanov I. Chemical Composition and Biological Activity of Extracts from the Aerial Parts of Epilobium parviflorum Schreb. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(22):12109. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212109

Chicago/Turabian StyleDimitrova, Mashenka, Inna Sulikovska, Elina Tsvetanova, Vera Djeliova, Anelia Vasileva, and Ivaylo Ivanov. 2025. "Chemical Composition and Biological Activity of Extracts from the Aerial Parts of Epilobium parviflorum Schreb." Applied Sciences 15, no. 22: 12109. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212109

APA StyleDimitrova, M., Sulikovska, I., Tsvetanova, E., Djeliova, V., Vasileva, A., & Ivanov, I. (2025). Chemical Composition and Biological Activity of Extracts from the Aerial Parts of Epilobium parviflorum Schreb. Applied Sciences, 15(22), 12109. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212109