Featured Application

Fruit extracts are rich sources of bioactive compounds, including vitamins, minerals, and polyphenols, with functional properties such as antioxidant capacity. Their incorporation into gummies presents a compelling strategy for nutritional fortification. This process involves the extraction of these valuable compounds, followed by their stabilization. This approach not only enhances the nutritional profile of gummy candies but also utilizes natural ingredients, aligning with consumer demand for healthier food options.

Abstract

Gummy candies can be improved with some beneficial health properties by adding healthier ingredients such as fruit extracts rich in bioactive compounds. In this study, gummy candies were fortified with orange peel extract at 7.5% (GC7.5) and 15% (GC15), obtained using ultrasonic-assisted extraction. Hesperidin (53.83 and 122.80 µg/g) and narirutin (9.32 and 20.98 µg/g) were found in higher concentration in gummy candies. After in vitro gastrointestinal digestion (GID), the bioaccessibility of hesperidin was 100.3% and 83.4% for GC7.5 and GC15, respectively, while for narirutin it was 99.15% and 80.58% for GC7.5 and GC15, respectively. In reference to antioxidant activity measure with 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl scavenger assay, the GID increased this capacity by 29.90% and 6.1% for GC7.5 and GC15, respectively, whilst for ferric reducing activity power assay, the GID reduced the antioxidant capacity by 6.46% and 9.97% for GC7.5 and GC15, respectively. With regard to chemical composition, GC7.5 and GC15 reduce the moisture (2.49% and 5.74%) and protein content (5.84% and 10.23%) compared to control. The extract acts as a coloring agent, while the pH and water activity were not affected by orange peel addition in both GC7.5 and GC15. Consequently, these findings suggest that orange peel is a valuable source of bioactive compounds, making it a promising ingredient for developing natural food ingredients with antioxidant benefits.

1. Introduction

The global food scenery is undergoing a significant transformation, driven by a growing consumer demand for products that offer health benefits beyond basic nutrition [1]. This change has given rise to the functional food market, which aims to integrate health-beneficial bioactive compounds into everyday consumables. Among the most popular and versatile foods that can be used as carriers of bioactive compounds is gummy candy [2]. Traditionally a simple confection, its widespread appeal, particularly to children and those with a sweet tooth, makes it an ideal matrix for the delivery of health-promoting ingredients [3]. Due to the palatability and simple composition of gummy candy, this product makes the ideal candidate for the bioactive compound addition. Furthermore, the sweet taste and pleasant, chewy texture effectively mask the often-unpleasant flavors, aromas, and textures of many bioactive compounds, such as the bitterness of certain vitamins or polyphenolic compounds [4]. This masking capability is particularly crucial for reaching demographics that might otherwise be unwilling to consume health supplements in tablet or liquid form [5]. Unlike other complex matrices, its low water activity and ambient shelf stability make it a suitable host for a range of sensitive ingredients. The production process, which involves a cooking step followed by cooling and setting, can also be adapted to minimize degradation of heat-sensitive compounds. On the other hand, gummy candies have a sugar content that normally exceeds 50% and also contain artificial colors and flavors. These factors can cause consumer rejection, as they have been linked to an increase in childhood obesity and the appearance of certain allergic reactions, as mentioned by Gallo et al. [6].

To avoid these undesirable health effects of gummy candy consumption, a vast group of bioactive compounds may be incorporated into gummies for their functionalization. Beyond essential nutrients such as vitamins, proteins, and minerals, phytochemicals such as flavonoids, carotenoids, and phenolic acids derived from fruits, vegetables, and herbs are highly sought after for their functional properties [7]. In this sense, several studies reported the addition of fruit, vegetable, and herb extracts into gummy candies. Thus, Al-Jaloudi et al. [7] carried out a study to produce a functional gummy candy with high antioxidant capacity by replacing table sugar and glucose syrup with honey and blueberry concentrate. Similarly, de Oliveira Nishiyama-Hortense et al. [8] conducted a work to elaborate a gummy candy fortified with grape juice which had a high anthocyanins content. More recently, Younesi et al. [9] elaborated a gummy candy fortified with microencapsulated roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa) extract. These candies showed high antioxidant activity and a high content of anthocyanins.

Among the fruits that show a high content of bioactive compounds in their composition are oranges, and Spain is one of the main orange producers in Europe. A part of this production is used to obtain juice, which generates a large amount of co-products formed mainly in the peel. The orange peel is rich in phytochemicals, mainly vitamin C and flavonoids, including hesperidin, narirutin, and diosmin, among others [10]. This fact makes this co-product a potential ingredient for food fortification, as long as extracts can be obtained in a fast, easy, and environmentally sustainable way.

In this sense, the extracts may be obtained through new extraction technologies that are more environmentally friendly. Therefore, the industry is continually exploring new technologies, among which ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) stands out. UAE allows for more effective and faster extraction, with lower solvent consumption and less degradation of sensitive compounds [11]. In this context, the extraction of bioactive compounds from plant material, using UAE, is widely established in food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries [12,13,14].

Despite these advances, a critical scientific gap remains in understanding how the incorporation of plant-based bioactives into confectionery matrices affects their stability, bioaccessibility, and functionality after digestion. Many studies focus on the enrichment and antioxidant potential of fortified gummies before consumption [7,8,9]; but few have evaluated the fate of these compounds during gastrointestinal digestion [15,16]. For all the reasons mentioned above, the aim of this study was to determine the polyphenolic compound content and the antioxidant properties of gummy candies fortified with orange peel extracts, as well as to study their antioxidant activity and the release after undergoing the in vitro gastrointestinal digestion process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Reagents

Orange fruits (Citrus × sinensis) var. navel lane late were collected at the experimental field station of Miguel Hernandez University in Orihuela, Spain, at the commercial ripening stage. The harvest of the samples was performed in February of 2025. The fruits were transported to the IPOA research group’s laboratory and brushed under running tap water for 2 min. Then, the peel was manually separated from the pulp and blended for 30 s using a vertical cutter. After that, the samples were lyophilized in a Christ Alpha 2–4 lyophilizer (B. Braun Biotech., Melsungen, Germany) for 36 h. A grinder mill and sieves were used to process the dehydrated peel into flour with a particle size of less than 210 µm.

Ethanol (1.00986), methanol (1.06018), calcium chloride (1.02378), sodium hydroxide solution 1 N (1.09137), hydrochloric acid solution 1 M (1.09057), and formic acid (5.33002) were acquired from Supelco (Bellefonte, PA, USA); Bile bovine (B3883) was purchased from Millipore (Burlington, MA, USA); porcine pepsin solution (2000 U/mL; P7012), pancreatin solution (100 U trypsin/mL; P7545, 8× USP specifications), and acetonitrile HPLC grade (34851) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany). Fructose was obtained from Santiveri S.L. (Barcelona, Spain); glucose (48647) was obtained from Sosa Ingredients (Barcelona, Spain). Royal Professional Gelatin from animal origin with 240 bloom was supplied by Mondelez S.L. (Madrid, Spain).

2.2. Production of Orange Peel Extract

The polyphenol-rich orange extract was obtained from lyophilized orange peel using sonotrode-assisted ultrasonic extraction with the Ultrasonicator UP400St (Hielscher Ultrasonics, Teltow, Germany), operating at 400 W and 24 kHz, coupled to the S24d14D probe (99 µm). Briefly, 5 g of lyophilized orange peel was mixed with 500 mL of 80% (v/v) hydroalcoholic ethanol, maintaining a solid-to-solvent ratio of 1:100. Before sonication, the mixture was stirred magnetically for 1 min at 750 rpm. After calibrating the equipment, ultrasonic energy of 43 J/mL was applied at 80% amplitude. Following sonication, the sample was centrifuged at 7000× g for 5 min, vacuum filtered, and rotary evaporated to concentrate the extract to 50 mL. The extract was vacuum filtered once more and stored frozen at −20 °C.

2.3. Preparation and Fortification of the Gummy Candies

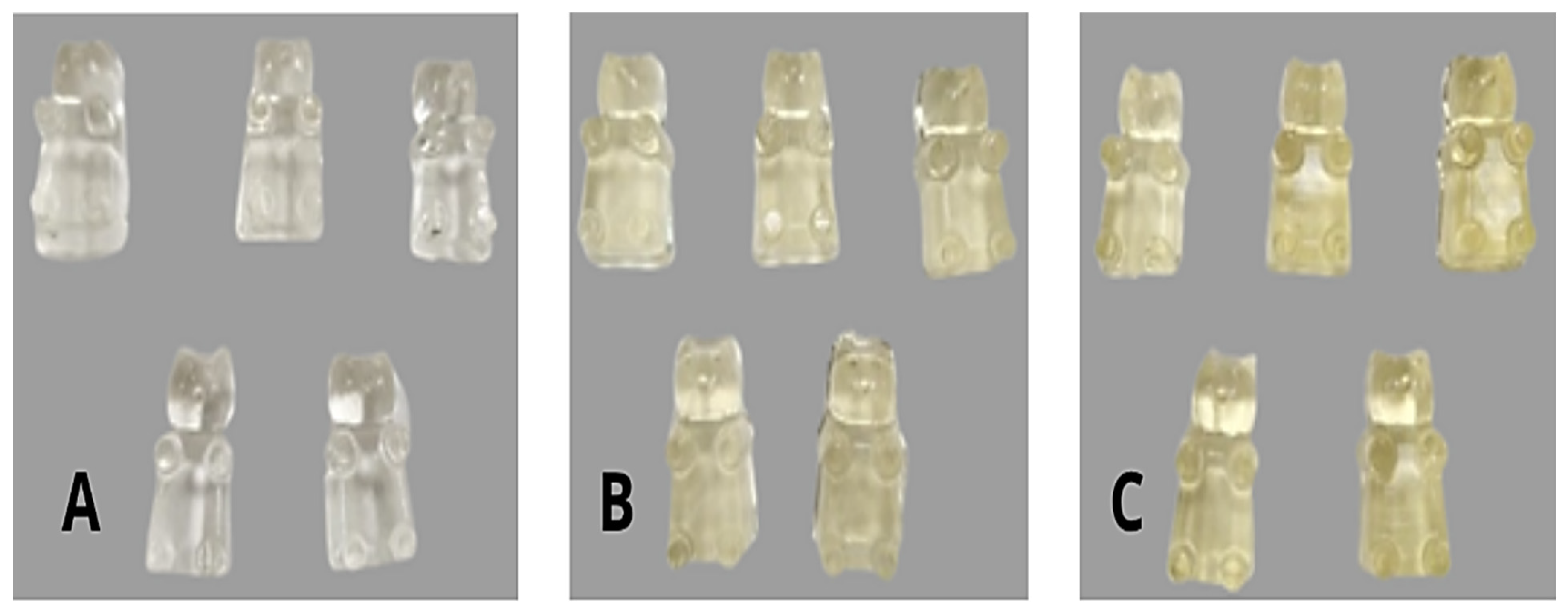

The fortification of gummy candies was performed with orange peel extract at different levels: 7.5% (GC7.5) and 15% (GC15). For the elaboration of the control gummy candy, glucose syrup (15% w/w), fructose powder (45% w/w), and water (5%w/w) were completely mixed and heated at 60 °C for 24 h. Gelatin solution (10% w/w) was prepared by dissolving the gelatin in distilled water (15% w/w) in a beaker at 25 °C and allowing it to swell for 5 min by absorbing water. The beaker was stoppered and placed at 70 °C for 10 min. Finally, the mixture was cooled by stirring on a magnetic stirrer at 50 °C. In the last step, the gelatin solution was added to the previously prepared solution and mixed [17]. When the temperature of the mixture decreased to 40 °C, the orange peel extract was added and gently mixed for 3 min; the mixture was then poured into silicone molds. To elaborate the fortified gummy candies, part of the water was replaced by water extract at the same concentration. All samples were kept at 4 °C for 24 h to ensure the gelation process. Figure 1 shows the control gummy candies (A) and fortified gummy candies containing orange peel extracts at 7.5% (B) and 15% (C).

Figure 1.

(A) control gummy candies; (B) fortified gummy candies containing 7.5% of orange peel extract; (C) fortified gummy candies containing 15% of orange peel extract.

2.4. Proximate Composition of Fortified Gummy Candies

Proximate composition of control and fortified gummy candies containing orange peel extracts was determined using standardized methods recommended by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists [18]. Moisture content was calculated by measuring the weight difference before and after drying the samples in an ED 400 oven (Binder, Tuttlingen, Germany) at 60 °C until a constant weight was achieved. Total ash content was analyzed using a 10-PR/400 muffle furnace (Hobersal, Barcelona, Spain) at 550 °C for 5 h. Crude protein was obtained using the Kjeldahl method in a Kjeltec System 2200 nitrogen distiller (FOSS IBERIA, Barcelona, Spain) with a digestion block (FOSS IBERIA, Barcelona, Spain). Fats were calculated by weight loss after a 6-cycle extraction with petroleum ether in a Soxhlet apparatus. Total carbohydrates were calculated by subtracting moisture, fat, protein, and ash from 100%.

2.5. Physico-Chemical Properties of Fortified Gummy Candies

The pH of the gummy candies was measured using a pH-meter Crison GLP 21 (Crison Instrument S.A., Barcelona, Spain) equipped with puncture electrode probe and automatic temperature compensation feature. Likewise, water activity (aw) was determined using a Novasina Thermoconstanter Sprint TH-500 (Novasina, Pfäffikon, Switzerland) at 25 °C. For that, the gummy candies (20 g) were crushed in a coffee mill (Black + Decker, Tomson, MD, USA) and placed in the capsules for measuring aw. The color properties of the gummy candies were analyzed using a Minolta CM-700d spectrophotocolorimeter (Konica Minolta, Osaka, Japan), equipped with illuminant D65 and 10° standard observer conditions, directly on each sample. Color was measured using the CIEL*a*b* color space where L* is lightness coordinate, a* is the red–green coordinate, and b* is the yellow–blue coordinate. From these coordinates, the color differences were calculated using Equation (1).

The texture profile analysis (TPA) was performed in a TA-XT2i Texture Analyzer (Stable Micro Systems, Surrey, UK). Each gummy candy sample was evaluated by applying a 40% strain at a test speed of 1 mm/s, with a post-test speed of 5 mm/s and an activation threshold of 0.049 N. The parameters determined were hardness (N), springiness (mm), gumminess, chewiness (N × mm), and resilience.

2.6. Simulated In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion

Simulated in vitro gastrointestinal digestion was performed following the INFOGEST harmonized protocol version 2.0 by Brodkorb et al. [19]. Prior to digestion, simulated oral, gastric, and intestinal stock solutions were prepared. Briefly, approximately 15 g of samples were ground using a coffee grinder until homogeneous pieces of about 0.2 × 0.2 × 0.2 cm were obtained. Then, 2.5 g of the ground sample was mixed with 2.5 mL of simulated oral solution (consisting of 2 mL oral stock solution, 12.5 µL CaCl2, and 487.5 µL distilled water) and incubated in a rotary mixer (ELMI Intelli-Mixer™ RM-2S; ELMI; Riga, Latvia) at 37 °C and 60 rpm for 2 min. Following the oral phase, the pH was adjusted by adding 100 µL of 1 M HCl and 4 mL of gastric stock solution. The simulated gastric solution was then completed by adding 2.5 µL CaCl2, 0.25 mL porcine pepsin solution, and distilled water to a final volume of 10 mL. Samples were incubated under the same conditions as the oral phase for 2 h. For the intestinal phase, the pH was immediately raised to 7.0 using 1 M NaOH after the gastric digestion. Then, 4.25 mL of intestinal stock solution, 20 µL CaCl2 (3 M), 1.25 mL bile bovine, and 2.5 mL pancreatin solution were added. The samples were incubated under the same conditions as the gastric phase. After the intestinal phase, samples were immediately centrifuged at 7000× g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were cleaned using C18 cartridges, eluted with acidified methanol, and transferred to amber HPLC vials, which were then stored frozen (−20 °C) until further analysis. The release of polyphenolic compounds was analyzed by determining the bioaccessibility index (Equation (2)) [20].

where BCSi is each individual polyphenolic compound in soluble fraction after intestinal phase and BCPs is each individual polyphenolic compound in undigested sample.

The determination of polyphenolic compounds was achieved as mentioned in Section 2.7.

2.7. Polyphenolic Profile Analysis

2.7.1. Extraction of Polyphenolic Compounds

For the extraction of polyphenolic compounds from fortified gummy candies containing orange peel extracts before and after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion, the methodology described by Lucas-González et al. [21] was used. For that, the samples (2 g) were submitted to two extraction steps in sequence; first with methanol–water (80:20 v/v) and then with acetone–water (70:30 v/v). In each extraction process, samples were sonicated (12 min in ultrasonic bath) and centrifugated (2300× g, 8 min and 4 °C). Both collected supernatants were combined and then evaporated under vacuum. The dry extract was resuspended in water and then purified with a C-18 Sep-Pak cartridge. The polyphenolic compounds were collected in methanol–formic acid (0.99:0.01 v:v).

2.7.2. HPLC Analysis

A Hewlett-Packard HPLC series 1200 instrument (Woldbronn, Germany) equipped with ultravisible–visible diode array detector and a Teknokroma Mediterranean sea18 column (C18; 250 × 0.04 mm, 5 μm particle size; Teknokroma, Barcelona, Spain) was used. The mobile phases were water–formic acid (99:1, v/v) as solvent A and acetonitrile as solvent B. The working conditions were gradient elution at 1 mL/min, 20 μL of injected volume, and temperature of column 35 °C. Three wavelengths including 280, 320, and 360 nm were used for the detection of polyphenolic compounds. The identification of compounds was conducted by comparison of their retention time and absorbance spectrum with pure standards. When standards were not available, the tentative identification was realized consulting the literature available [22,23].

2.8. Antioxidant Properties

The antioxidant properties of undigested and digested extracts obtained from fortified gummy candies containing orange peel extracts were analyzed using two different spectrophotometric assays, namely DPPH radical scavenging assay and Ferric ion reducing antioxidant power (FRAP). The DPPH assay was carried out following the recommendations of Brand Williams et al. [24], while the FRAP was analyzed using the potassium ferricyanide ferric chloride method as described by Benzie and Strain [25]. The results for both methods were expressed as µg Trolox Equivalent/g sample.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

The full process (orange peel extract production and gummy candy manufacture) was replicated three times (three independent batches with 40 gummy candies per batch and treatment). Each replication was performed on a different production day, and each batch was analyzed in triplicate. The results were reported as average ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were performed using the Infostat v.2020 statistical software package linked to the R program version 4.4.1 [26]. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) test at p < 0.05 was performed for all the experimental variables using a generalized linear mixed model, with concentration of extract added as fixed factor. If differences were found between treatments, a mean comparison was made using Tukey’s test.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Proximate Composition of Gummy Candies

Table 1 shows the proximal composition of control and fortified gummy candies containing orange peel extracts at 7.5 and 15%. Control gummy candy showed the highest values (p < 0.05) for moisture and protein content. The addition of orange peel extracts produced a reduction in these two parameters. The greater the addition of extract, the greater the reduction, at least with the two concentrations tested. Consequently, the GC15 had the lowest (p < 0.05) values for moisture and protein. On the other hand, the carbohydrate content followed an inverse behavior to that observed for moisture and proteins. Thus, GCC had the lowest (p < 0.05) value, while GC15 was the sample that showed the highest (p < 0.05) carbohydrate content. It is important to notice that in all analyzed samples (GCC, GC7.5 and GC15), no fat and ash were found. The moisture content obtained in this work was higher than reported in several studies where fruit extracts were added to fortified gummy candies [27,28].

Table 1.

Proximate composition of control and fortified gummy candies containing orange peel extracts at 7.5% and 15%.

3.2. Physico-Chemical Properties of Gummy Candies

The physico-chemical properties of control and fortified gummy candies containing orange peel extracts at 7.5 and 15% are shown in Table 2. For pH, the values ranged between 5.23 and 5.28 with no statistical differences (p > 0.05) between samples. The pH values were higher than reported for this type of product, varying between 3 and 5 [29]. For water activity, no statistical differences (p > 0.05) were found between the control sample and the samples fortified with orange peel extract at both concentrations. The results obtained were higher than expected for this type of product, which fall between 0.45 and 0.75 and are considered products with intermediate water activity as reported by Efe [30].

Table 2.

Physico-chemical properties of control and fortified gummy candies containing orange peel extracts at 7.5% and 15%.

This probably resulted from the somewhat higher moisture content of samples which may be due to the use of high concentrations of sugars such as fructose and glucose syrup, which are highly hygroscopic and retain moisture in the matrix. At the same time, a high concentration of gelatin was used, which may have provided a firmer three-dimensional matrix that prevented the release of water during the gelling and drying processes. With the values obtained in this study for pH and water activity, oxidative, microbiological, and enzymatic processes are possible.

The visual characteristics of confectionery products, particularly their color, are a primary determinant of consumer acceptance. The chromatic attributes of a food item significantly influence gustatory perception, affecting taste thresholds and shaping the expected palatability and hedonic response upon consumption [31]. This phenomenon underscores the critical role of color as a sensory cue that preconditions the consumer’s experience and overall evaluation of the product [4]. Table 2 shows the color results obtained for the control and fortified gummy candies containing orange peel extracts at 7.5 and 15%. The control gummy candy, with a clear and opaque coloration, showed the highest (p < 0.05) lightness (L*) values. The addition of orange peel extracts reduced the values for this coordinate without statistical differences (p > 0.05) between GC7.5% and GC15%. Several studies reported that the addition of fruit extracts in gummy candies produced a reduction in L* values. Therefore, Heidari et al. [32] reported that gummy candies fortified with grape extract had lower L* values than control sample. Similarly, Ozcan et al. [27] reported a reduction in lightness values of gelatin-based jelly candies containing purple basil leaf anthocyanin-rich extract. For the redness (a*) coordinate, the addition of orange peel extract increased (p < 0.05) the values in a concentration-dependent manner. Also, both samples, GC7.5% and GC15%, had higher b* values (p < 0.05) compared to control, and as a result, their color tended to be yellow. This is due to the orange-yellow color of the orange peel extract. Regarding color differences (ΔE*), no statistical differences (p > 0.05) were found between GC7.5% and GC15% samples. It is important to highlight that in both samples, the color differences were higher than 5 units, which means that the human eye could identify them as having a different color [33].

In reference to texture profile analysis (Table 3), the samples showed significant differences (p < 0.05) for all texture parameters except for springiness. The control sample showed the lowest (p < 0.05) values for hardness, adhesiveness, gumminess, and chewiness, while it had the highest value for resilience. It is important to notice that, for all textural parameters, no statistical differences (p > 0.05) were found between the samples fortified with orange peel extract at 7.5 and 15%. As regards hardness, this behavior is similar to that reported by Cedeño-Pinos et al. [34] in gummy candies fortified with rosemary extracts and de Moura et al. [35] in jelly candies fortified with anthocyanin extract from Hibiscus sabdariffa.

Table 3.

Textural properties of control and fortified gummy candies containing orange peel extracts at 7.5% and 15%.

In reference to chewiness and gumminess (Table 3), which are defined as the energy required to masticate a solid or semi-solid food to a state ready for swallowing, the obtained results were similar to those reported by Ozcan et al. [27] in gelatin-based jelly candies containing purple basil leaf anthocyanin-rich extract. This phenomenon could be due to interaction between orange extracts components such as pectic and gummy matrix. As mentioned by Gunes et al. [31] the texture profile of gummy candies is influenced by several aspects, such as the elaboration process, water content, concentration and hydrocolloid type use, sugar type, air content, as well as the presence of other compounds.

3.3. Polyphenolic Profile of Orange Peel Extracts and Fortified Gummy Candies

The polyphenolic profile of orange peel extracts is shown in Table 4. In orange peel extracts, twenty-nine polyphenolic compounds were identified, eleven hydroxycinnamic acid, twelve derivatives flavones, and six flavanones, with main compounds being hesperidin and narirutin (p < 0.05). These results agree with Lin et al. [23] and Niglio et al. [22], who reported between 11 and 16 hydroxycinnamates and between 11 and 25 flavonoids, mainly flavones and flavanones. Moreover, in the peel of three Indonesian orange varieties, Anggela et al. [36] detected nine flavones, such as diosmin, orientin, and nobiletin, and seven flavanones including hesperidin. Despite orange peel showing high diversity of phenolic acids and flavones, the highest amounts were reported by flavanone compounds (Table 4), which are the principal polyphenolic compounds in orange peel. Araujo León et al. [37] reported that the main flavonoid found in orange peel is hesperidin with a concentration of 2.51 mg/g, followed by naringin, while Ramírez-Sucre et al. [38] mentioned that hesperidin was found at highest concentration in orange peel extract with values of 6.42 mg/g. Niglio et al. [22], reported that narirutin and hesperidin were the predominant flavanones in peel orange extract obtained after a non-thermal and solvent-free extraction process, with values of 129.35 and 95.98 µg/mL, respectively. These values were lower than those reported in this study. This fact can be due to different extractions methods and the presence of ethanol as extractant, which improves polyphenol permeability from cell to extractant.

Table 4.

Polyphenolic profile of orange peel extract.

Table 5 shows the polyphenolic compounds found in undigested gummy candies containing orange peel extract at different concentrations. In control gummy candies, as expected, no polyphenolic compounds were found, while in gummy candies fortified with orange peel extracts at different concentrations, six flavanones detected on the orange peel extract, four flavones and one hydroxycinnamic acid derivative were found.

Table 5.

Polyphenolic profile of fortified gummy candies containing orange peel extracts at 7.5% and 15% before in vitro gastrointestinal digestion.

At both concentrations, the main component found (p < 0.05) was hesperidin, followed by narirutin. It is important to highlight that although sample GC15 had twice as much added extract as sample GC7.5, the concentration of all polyphenolic compounds in this sample was more than twice as high as that of sample GC7.5. In this sense, the polyphenol amount quantified in each enriched gummy candy was not in agreement with the theoretical prediction, showing a lower amount than expected (Supplementary Table S1). The highest recovery was shown by flavanones, with 62.14% and 71.39% for the gummy candy fortified with orange peel extract at 7.5% and 15%, respectively, while the total polyphenol recovery was lower than 45% on both fortified gummy candies. This might be because the thermal process used in making gummy candies might affect these compounds causing their degradation. It is also possible that the several polyphenolic compounds present in the orange peel extract have bound to the proteins present in the gelatin, which would prevent their extraction with the solvents used. These results are in line with those reported by de Oliveira Nishiyama-Hortense et al. [8], who reported that jelly candies enriched with violeta grape juice have lower anthocyanin concentration than both grape and grape juice. Similarly, Enache et al. [39] reported that cornelian cherry fruit extracts obtained using ultrasound assisted extraction process had a higher concentration of bioactive compounds (phenolic acids, flavonoids, and Vitamin C) than the jelly candies enriched with this extract.

Hesperidin and narirutin are bioactive flavonoids recognized for their significant health-promoting effects. Both compounds exhibit potent antioxidant properties, reducing oxidative stress and protecting cells from free radical damage [40]. Studies suggest that hesperidin improves vascular function by enhancing endothelial activity and lowering blood pressure, contributing to cardiovascular health [41]. Narirutin has demonstrated anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects, potentially beneficial in preventing neurodegenerative disorders [42]. Furthermore, both flavonoids modulate lipid metabolism and glucose regulation, supporting metabolic balance [43]. Their synergistic activity enhances overall physiological resilience, making them promising candidates for functional foods and nutraceutical applications targeting chronic disease prevention.

3.4. Polyphenolic Profile of Fortified Gummy Candies After In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion

In vitro gastrointestinal digestion models are essential tools in nutritional science for studying the fate of food components during digestion. These models, which simulate the physiological conditions of the mouth, stomach, and small intestine, provide a controlled and reproducible environment to analyze the release and bioaccessibility of bioactive compounds [44]. Unlike in vivo studies, in vitro models are cost-effective, high-throughput, and do not require ethical approval. While they cannot fully replicate the complexity of the human gut environment, including the gut microbiome and host metabolism, they serve as a fundamental first step in understanding and screening the bioavailability of bioactive compounds [45]. Additionally, this process enables the determination of bioaccessibility, defined as the fraction of a compound that is released from the food matrix and becomes available for absorption in the small intestine [46].

The polyphenolic profile of control gummy and fortified gummy candies containing orange peel extracts at 7.5 and 15% after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion is shown on Table 6. Again, in control gummy candies, no polyphenolic compounds were detected after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion, whilst in fortified gummy candies (GC7.5 and GC15) all polyphenols identified in the undigested fortified gummy candies were detected again, with the exception of apigenin-6,8-di-C-glycoside and naringin, which were not observed. In both GC7.5 and GC15 (Table 5), the principal compounds identified were hesperidin and narirutin (p < 0.05). In the case of GC7.5, the in vitro gastrointestinal digestion elicited a significant decrease in apigenin-6,8-di-C-glycoside and diosmetin glycoside. On the other hand, for GC15, apigenin-6,8-di-C-glycoside, diosmetin glycoside, naringenin triglycoside, and hesperitin triglycoside were drastically reduced after the in vitro digestion process (p < 0.05). These values were in agreement with those reported by Ozcan et al. [27], who reported that, in gelatin-based jelly candies fortified with purple basil leaf anthocyanins, the concentration of anthocyanins in intestinal phase decreased y baround 34%, and Liu et al. [47], who reported that the anthocyanin content in gelatin and gellan gum gummies fortified with blueberry extracts decreases from 42.4% of the initial amount to 30.1% after the intestinal phase. The reduction in concentration can be attributed to the digestive process and its different phases. During the digestion process, phenolic acids and flavonoids may be released, degraded, and transformed because of their susceptibility. Thus, usually glycosidic bonds of sugar moieties are cut during digestion. In addition, there might be interactions with macromolecules like carbohydrates, peptides, or enzymes present in the solution [48].

Table 6.

Polyphenolic profile of fortified gummy candies fortified with orange peel extracts at 7.5 and 15% after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion process.

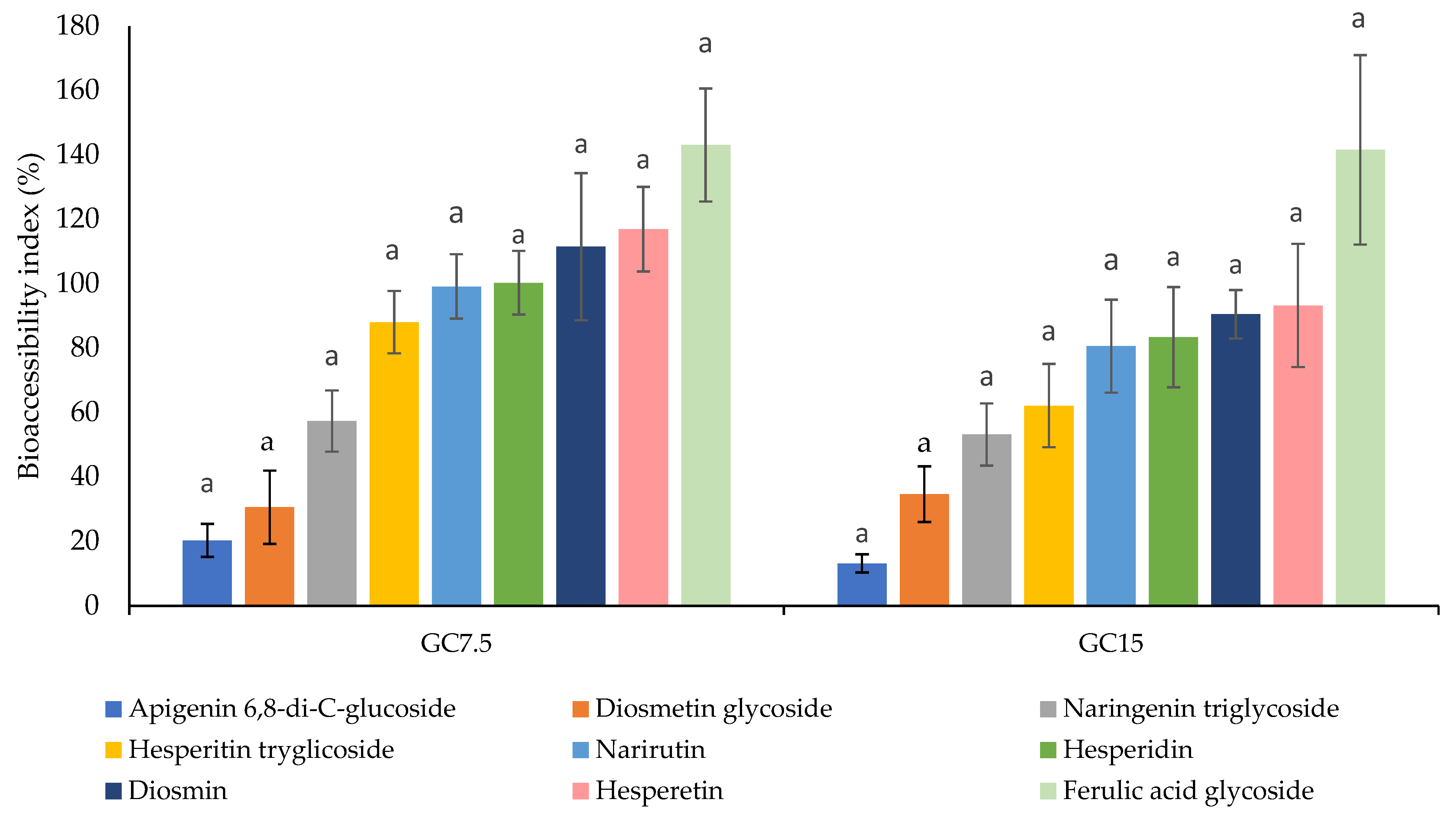

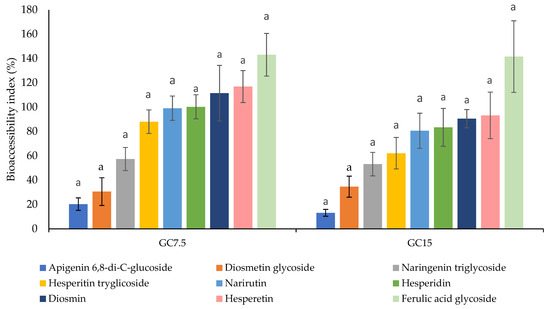

To exert their bioactivity, bioactive compounds must first to be bioaccessible, i.e., released from the food matrix and solubilized. The bioaccessibility index of polyphenolic compounds found in fortified gummy candies containing orange peel extracts at 7.5 and 15% after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion is reported in Figure 2. In this work, results have shown that, for GC7.5, the bioaccessibility for ferulic acid glycoside, hesperetin, and diosmin is higher than 100% with values of 143.06%, 116.92%, and 111.48%.

Figure 2.

Bioaccessibility index of polyphenolic compounds present in fortified gummy candies containing orange peel extracts at 7.5 and 15% after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion. GC7.5: gummy candy fortified with orange peel extract at 7.5%; GC15: gummy candy fortified with orange peel extract at 15%. For the same compound, histograms with different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s multiple range test.

On the other hand, for GC15, only ferulic acid glycoside had a bioaccessibility higher than 100% (141.57%). This may be due to the fact that during the gummy candies’ formation process, when orange peel extract is added, ferulic acid glycoside and other polyphenolic compounds such as hesperidin and diosmin can bound to gelatin proteins, preventing their release. However, the simulated digestion process does release these compounds and allows their detection. The rest of the phenolic compounds identified have a bioaccessibility lower than 100%, which indicates that during the digestion process, these compounds have been degraded or lost. This fact might be caused by several factors including variations in pH value, concentration of enzymes and bile salts, as well as for the temperature during the gastrointestinal digestion progression [49]. In addition, throughout the digestion process, flavonoids may have interactions with different food matrix components such as proteins and carbohydrates [50], which causes a reduction in their bioaccessibility in the last stage of digestion. Except for apigenin 6,8-di-C-glucoside and diosmetin glycoside, which exhibited bioaccessibility indices below 50% in both fortified gummy formulations, all other compounds demonstrated high bioaccessibility. Accordingly, the total polyphenol bioaccessibility was 97.02% and 80.30% for GC7.5 and GC15, respectively.

3.5. Antioxidant Properties of Gummy Candies After and Before In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion

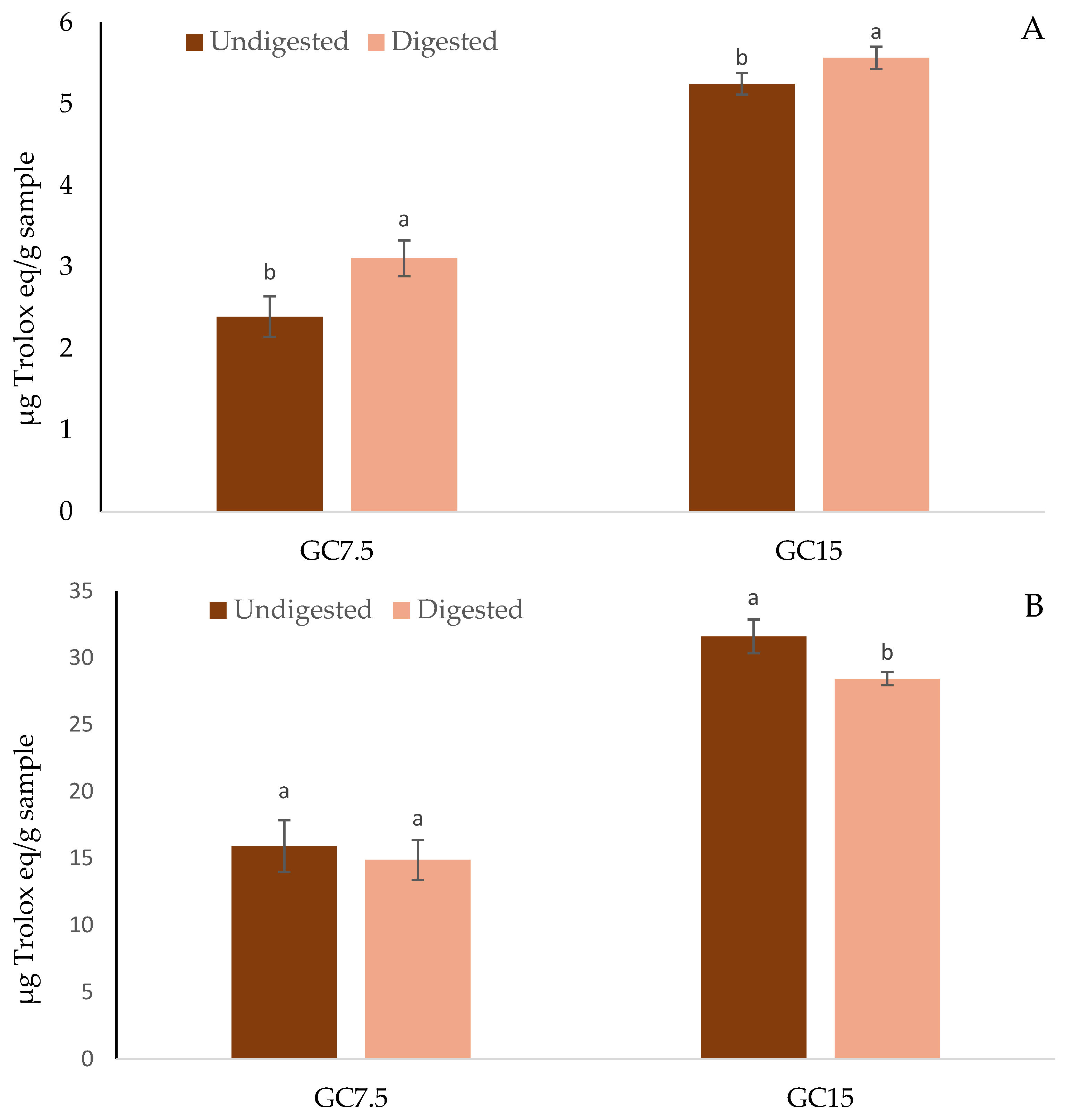

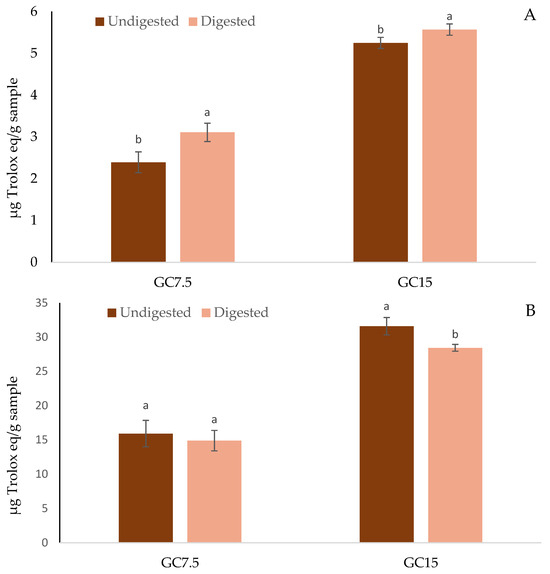

An analysis of antioxidant capacity is helpful for assessing how bioactive compounds can protect the body from the damaging effects of free radicals and other oxidizing molecules [51]. The antioxidant capacity of gummy candies fortified with orange peel extracts at different concentrations and in vitro digested gummy candies, determined with DPPH and FRAP assays, is shown in Figure 3. The gummy candies fortified with orange peel extracts showed antioxidant properties measured by both methods, as orange peel extracts are characterized by powerful antioxidant activity [52,53]. Thus, it should be considered that the addition of peel extract contributed to the antioxidant activity of the gummy candies. In this work, the scavenging potential of polyphenolic compounds present in GC7.5 and GC15 towards DPPH radicals (Figure 3A), before and after in vitro digestion, was determined. With regard to undigested samples, GC7.5 showed an antioxidant capacity, measured with the DPPH assay and FRAP assay, of 2.39 and 15.92 µg Trolox equivalent (TE)/g sample, while in GC15, as expected, this antioxidant capacity was higher, with values of 5.25 and 31.60 µg TE/g sample, for the DPPH and FRAP assays, respectively. The antioxidant activity of gummy candy fortified with fruit or herbal extracts which have a huge content of bioactive compounds, is widely analyzed. Thus, Jasmine and Surya [54] informed that the antioxidant capacity of jelly candy fortified with orange peel extract at 3% produces an inhibition of DPPH radical of 82.36%. Similarly, Abinaya et al. [55] reported that the fortification of gummy candies with red onion peel extracts at 25% resulted in a DPPH radical scavenging activity of 29.75%, while in ABTS, radical scavenging activity the antioxidant capacity was 12.74%. In a similar study, Teixeira-Lemos et al. [56] found that the antioxidant capacity, measured with the DPPH assay, of gummy candies fortified with red fruit puree (54.5%) or orange juice (86.2%) was 83.7 and 50.4 mg Trolox equivalent/100 g of sample, respectively.

Figure 3.

Antioxidant capacity of gummy candies containing orange peel extracts at 7.5 and 15% before and after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion. Mean ± standard deviation (n = 9). (A) Measured with DPPH assay. (B) Measured with FRAP assay. For the same assay and the same sample (GC7.5 and GC15), histograms with different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s multiple range test.

In reference to the antioxidant capacity of gummy candies after in vitro digestion process, measured with the DPPH assay (Figure 3A), for GC7.5, digestion processes significantly increased (29.90%) the antioxidant activity showing statistical differences (p < 0.05) between undigested and digested samples. In the same way, for GC15, the antioxidant activity was higher (p < 0.05) in digested than in undigested samples, with an increase in antioxidant activity of 6.1%. In the FRAP assay, the results obtained (Figure 3B) showed that no statistical differences (p > 0.05) were found between undigested and digested gummy candies containing orange peel extracts at 7.5%. Nevertheless, for gummy candies containing orange peel extracts at 15%, undigested samples had higher values (p < 0.05) for the reducing power (+9.97%) compared to digested GC15%. The antioxidant activity of fortified gummies, following the in vitro digestion process, depends on the method used to measure them. Thus, DPPH indicates moderate antioxidant activity that increases after digestion, while FRAP shows lower antioxidant activity that decreases after the digestive process. This is related to the bioactive compounds released from the matrix, which have a greater capacity to scavenge free radicals than to reduce metals. In the scientific literature, the antioxidant capacity of gummy candies, subject to a gastrointestinal digestion process, has also been determined. Thus, Gorjanović et al. [15] reported that gummy candies fortified with apple or beetroot pomace flour increased the antioxidant capacity after the digestion process from 2.05 and 1.85 mmol TE/g to 2.72 and 3.03 mmol TE/g, respectively, measured with the FRAP assay; whilst for the DPPH assay, apple and beetroot gummy candies increased the antioxidant capacity from 2.20 and 2.40 mmol TE/g to 2.99 and 3.42 mmol TE/g, respectively. Rivero et al. [16] found that the antioxidant capacity value obtained for the soluble faction of in vitro digestion of gummy jelly containing honey and propolis was 3.33 mmol TE/kg, representing around 40% retention of the product’s antioxidant capacity.

It is important to mention that after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion, the concentration of most polyphenolic compounds in CG7.5 decreases, with the exception of ferulic acid glycoside, hesperetin, and diosmin. However, the antioxidant activity measured with DPPH increases, suggesting that this activity could be associated with these compounds. This behavior is also observed in the case of CG15, where only ferulic acid glycoside increases after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion, which is reflected in a smaller increase in antioxidant activity.

In the case of FRAP, antioxidant activity decreases after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion, coinciding with the reduction in the release of polyphenolic compounds, which establishes a clear relationship between polyphenol release and the ferric ion reduction capacity.

4. Conclusions

Orange peel extract can play a role of natural additive in the development of healthier gummy candies because it helps to improve the color and provides bioactive compounds, mostly polyphenols, which provide antioxidant properties to gummy candies. In addition, these antioxidant properties are maintained after the in vitro digestion process of the gummies, in addition to showing important bioaccessibility of most of the polyphenolic compounds.

For all the reasons mentioned above, orange peel extract can be considered a cheap, sustainable, and viable alternative for the functionalization of gummies, making this product healthier.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152111795/s1, Table S1: Polyphenols recovery of fortified gummy candies containing orange peel extracts at 7.5 and 15%.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V.-M. and R.L.-G.; methodology, A.A.-B. and R.L.-G.; validation, R.L.-G. and J.F.-L.; formal analysis, M.V.-M.; investigation, M.V.-M. and R.L.-G.; resources, J.Á.P.-Á.; data curation, J.F.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.-B. and R.L.-G.; writing—review and editing, M.V.-M. and J.F.-L.; visualization, J.Á.P.-Á. and J.F.-L.; supervision, J.Á.P.-Á. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by the Program SPRINT-UMH-FAPESP 2025–2026 through the Research Project “Strategies for the valorization of jotobá and citric co-products”. Ref 11-131-4-2025-0089-N.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Javier Andreu for the donations in kind of the orange samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fekete, M.; Lehoczki, A.; Kryczyk-Poprawa, A.; Zábó, V.; Varga, J.T.; Bálint, M.; Fazekas-Pongor, V.; Csípő, T.; Rząsa-Duran, E.; Varga, P. Functional Foods in Modern Nutrition Science: Mechanisms, Evidence, and Public Health Implications. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiné, R.P.F.; Correia, P.M.R.; Reis, C.; Florença, S.G. Evaluation of texture in jelly gums incorporating berries and aromatic plants. Open Agric. 2020, 5, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipini da Silveira, M.; Priscilla Efraim, P.; Viscondi Silva, M.J.; das Neves de Aro, J.; Fadini, A.L.; de Castilho Queiroz, G.; Martins Montenegro, F.; Bonifácio Queiroz, M. Improving the nutritional profile of jelly candies. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebin, A.V.; Bunić, M.; Mandura Jarić, A.; Šeremet, D.; Komes, D. Physicochemical and Sensory Stability Evaluation of Gummy Candies Fortified with Mountain Germander Extract and Prebiotics. Polymers 2024, 16, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Kawamoto, S.; Kashiwagura, Y.; Hakamata, A.; Odagiri, K.; Okura, T.; Inui, N.; Watanabe, H.; Namiki, N.; Uchida, S. Improved Palatability of Gummy Drugs of Epinastine Hydrochloride Using Organoleptic Taste-Masking Methods. BPB Rep. 2023, 6, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, M.; Ferrara, L.; Calogero, A.; Montesano, D.; Naviglio, D. Relationships between food and diseases: What to know to ensure food safety. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jaloudi, R.; Al-Refaie, D.; Shahein, M.; Hamad, H.J.; Al-Dabbas, M.M.; Shehadeh, N.; AlBtoosh, J.; Al-Nawasrah, B.A.; Alkhderat, R.; Ababneh, S.K. Development of Functional Jelly Gums Using Blueberry Concentrate and Honey: Physicochemical and Sensory Analysis. Processes 2025, 13, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Nishiyama-Hortense, Y.P.; de Paula Rossi, M.J.; Shimizu-Marin, V.D.; Soares Janzantti, N.; Gómez-Alonso, S.; Da-Silva, R.; Silva Lago-Vanzela, E. Jelly candy enriched with BRS Violeta grape juice: Anthocyanin retention and sensory evaluation. Future Foods 2022, 6, 100179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younesi, M.; Peighambardoust, S.H.; Sarabandi, K.; Akbarmehr, A.; Ahaninjan, M.; Soltanzadeh, M. Application of structurally modified WPC in combination with maltodextrin for microencapsulation of Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa) extract as a natural colorant source for gummy candy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 124903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, G.; Fernández-López, J.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.A.; Peñalver, R.; Ros-Berruezo, G.; Viuda-Martos, M. Valorization of Citrus Co-Products: Recovery of Bioactive Compounds and Application in Meat and Meat Products. Plants 2021, 10, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Wang, L.; Wang, G.; Zhang, A.; Wang, X.; Jiang, L. Ultrasonication Effects on Physicochemical and Emulsifying Properties of Cyperus esculentus Seed (Tiger Nut) Proteins. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 142, 110979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-C.; Chiang, Y.-C.; Chen, M.-H.; Chiang, P.-Y. Micronization Combined Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Enhances the Sustainability of Polyphenols from Pineapple and Lemon Peels Utilizing Acidified Ethanol. Foods 2025, 14, 2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Zamora, L.; Bueso, M.C.; Kessler, M.; Zapata, R.; Gómez, P.A.; Artés-Hernández, F. Optimization of Extraction Parameters for Phenolics Recovery from Avocado Peels Using Ultrasound and Microwave Technologies. Foods 2025, 14, 2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drăghici-Popa, A.-M.; Pârvulescu, O.C.; Stan, R.; Brezoiu, A.-M. Optimization of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Romanian Blackthorn (Prunus spinosa L.) Fruits. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorjanović, S.; Zlatanović, S.; Laličić-Petronijević, J.; Dodevska, M.; Micić, D.; Stevanović, M.; Pastor, F. Enhancing composition and functionality of jelly candies through apple and beetroot pomace flour addition. npj Sci. Food 2024, 8, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero, R.; Archaina, D.; Sosa, N.; Leiva, G.; Baldi Coronel, B.; Schebor, C. Development of healthy gummy jellies containing honey and propolis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoen, R.; Savedboworn, W.; Phuditcharnchnakun, S.; Khuntaweetap, T. Development of antioxidant gummy jelly candy supplemented with Psidium guajava leaf extract. App. Sci. Engin. Prog. 2015, 8, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International. Association of Official Analytical Chemists, 17th ed.; AOAC: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brodkorb, A.; Egger, L.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Assunção, R.; Balance, S.; Recio, I. INFOGEST static in vitro simulation of gastrointestinal food digestion. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 991–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minekus, M.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Balance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu, C.; Brodkorb, A. A standardized static in vitro digestion method suitable for food—An international consensus. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas-González, R.; Pérez-Alvarez, J.Á.; Viuda-Martos, M.; Fernández-López, J. Pork liver pâté enriched with persimmon coproducts: Effect of in vitro gastrointestinal digestion on its fatty acid and polyphenol profile stability. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niglio, S.; Razola-Díaz, M.C.; Waegeman, H.; Verardo, V. Food grade pilot scale strategy for non-thermal extraction and recovery of phenolic compounds from orange peels. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 205, 116538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.Z.; Harnly, J.M. A Screening Method for the Identification of Glycosylated Flavonoids and Other Phenolic Compounds Using a Standard Analytical Approach for All Plant Materials. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 1084–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a Free Radical Method to Evaluate Antioxidant Activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Rienzo, J.A.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M.G.; Gonzalez, L.; Tablada, M.; Robledo, C.W. InfoStat Versión. Centro de Transferencia InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Argentina. 2020. Available online: http://www.infostat.com.ar (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Ozcan, B.E.; Karakas, C.Y.; Karadag, A. Application of purple basil leaf anthocyanins-loaded alginate-carrageenan emulgel beads in gelatin-based jelly candies. Int. J. Biolog. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarabandi, K.; Akbarbaglu, Z.; Peighambardoust, S.H.; Ayaseh, A.; Jafari, S.M. Biological stabilization of natural pigment-phytochemical from poppy-pollen (Papaver bracteatum) extract: Functional food formulation. Food Chem. 2023, 429, 136885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burey, P.; Bhandari, B.R.; Rutgers, R.P.G.; Halley, P.J.; Torley, P.J. Confectionery gels: A Review on Formulation, Rheological and Structural Aspects. Int. J. Food Prop. 2009, 12, 176–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efe, N.; Dawson, P. A Review: Sugar-based Confectionery and the Importance of Ingredients. Eur. J. Agric. Food Sci. 2022, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunes, R.; Palabiyik, I.; Konar, N.; Toker, O.S. Soft Confectionery Products: Quality Parameters, Interactions with Processing and Ingredients. Food Chem. 2022, 385, 132735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, M.; Pezeshki, A.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Hamishehkar, H.; Azar, F.A.N.; Mohammadi, M.; Ghorbani, M. Microencapsulation of Vitis vinifera grape pulp phenolic extract using maltodextrin and its application in gummy candy enrichment. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 3405–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasi, V.; Huber, E.; Goldoni, T.S.H.; de Melo, A.P.Z.; Hoff, R.B.; Verruck, S.; Barreto, P.L.M. Goldenberry flour as a natural antioxidant in Bologna-type mortadella during refrigerated storage and in vitro digestion. Meat Sci. 2023, 196, 109041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedeño-Pinos, C.; Martínez-Tomé, M.; Murcia, M.A.; Jordán, M.J.; Bañón, S. Assessment of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) Extract as Antioxidant in Jelly Candies Made with Fructan Fibres and Stevia. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Moura, S.C.S.R.; Berling, C.L.; Garcia, A.O.; Queiroz, M.B.; Alvim, I.D.; Hubinger, M.D. Release of anthocyanins from the hibiscus extract encapsulated by ionic gelation and application of microparticles in jelly candy. Food Res. Int. 2019, 121, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anggela, R.H.; Setyaningsih, W.; Irawadi, T.T.; Karomah, A.H.; Rafi, M. LC−MS/MS−based metabolite profiling and antioxidant evaluation of three Indonesian orange varieties. Food Humanit. 2024, 3, 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo-León, J.A.; Segura-Campos, M.R.; Ortiz-Andrade, R.; Vazquez-Garcia, P.; Carvajal-Sánchez, D.; Cabañas-Wuan, Á.; González-Sánchez, A.A.; Uuh-Narvaez, J.; Sánchez-Salgado, J.C.; Fuentes-Noriega, I.; et al. Hypoglycemic and Antihyperglycemic Potential of Flavonoid Fraction from Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck in Normoglycemic and Diabetic Rats. Sci. Pharm. 2023, 91, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Sucre, M.O.; Avilés-Betanzos, K.A.; López-Martínez, A.; Rodríguez-Buenfil, I.M. Evaluation of Polyphenol Profile from Citrus Peel Obtained by Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent/Ultrasound Extraction. Processes 2024, 12, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enache, I.M.; Benito-Román, Ó.; Coman, G.; Vizireanu, C.; Stănciuc, N.; Andronoiu, D.G.; Mihalcea, L.; Sanz, M.T. Extraction optimization and valorization of the cornelian cherry fruits extracts: Evidence on antioxidant activity and food applications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, T.; Bian, C.; Ma, Z. In vitro and in silico perspectives on the activation of antioxidant responsive element by citrus derived flavonoids. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1257172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperatrice, M.; Cuijpers, I.; Troost, F.J.; Sthijns, M.M.J.P.E. Hesperidin Functions as an Ergogenic Aid by Increasing Endothelial Function and Decreasing Exercise-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammation, Thereby Contributing to Improved Exercise Performance. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, Z.; Jing, L.; Jie, C.; Zhijie, Z.; Liwen, D.; Zhijun, H.; Jun, Z.; Linghui, Z.; Jianping, J. Narirutin attenuates LPS-induced neuroinflammatory responses in both microglial cells and wild-type mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 159, 114954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kwon, D.; Yun, C.; Kimc, J.H.; Kimd, K.M.; Baed, G.Y.; Yang, M.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Jung, Y.S. Anti-Obesity Effects of Narirutin and Hesperidin in Immature Citrus Reticulata Extract via AMPK Activation in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice. Food Sci. Hum. Well. 2025, 15, 9250649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas-González, R.; Viuda-Martos, M.; Pérez-Alvarez, J.A.; Fernández-López, J. In vitro digestion models suitable for foods: Opportunities for new fields of application and challenges. Food Res. Int. 2018, 107, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ośko, J.; Nasierowska, K.; Grembecka, M. Application of in vitro digestion models in the evaluation of dietary supplements. Foods 2024, 13, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duque-Soto, C.; Quirantes-Piné, R.; Borrás-Linares, I.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Lozano-Sánchez, J. Characterization and influence of static in vitro digestion on bioaccessibility of bioactive polyphenols from an olive leaf extract. Foods 2022, 11, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, D.; Song, X.; Guo, M.; Wang, Z.; Geng, F.; Zhou, X.; Nie, S. Compound hydrogels derived from gelatin and gellan gum regulates the release of anthocyanins in simulated digestion. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 127, 107487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtolo, M.; Gerrano, A.; Mellem, J. Effect of simulated gastrointestinal digestion on the phenolic compound content and in vitro antioxidant capacity of processed Cowpea (V. unguiculata) cultivars. CyTA J. Food. 2017, 15, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa De León, D.; Méndez-López, L.F.; González-Martínez, B.E.; López-Cabanillas Lomelí, M.; López-Hernández, A.A.; Luna-Vital, D.A.; Néder-Suárez, D.; Vázquez-Rodríguez, J.A. Bioaccessibility and potential bioactivity of fresh and mature fava bean flavonoids. Appl. Food Res. 2024, 4, 100523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, T.; Carriere, F.; Day, L.; Deglaire, A.; Egger, L.; Freitas, D.; Golding, M.; Le Feunteun, S.; Macierzanka, A.; Menard, O.; et al. Correlation between in vitro and in vivo data on food digestion. What can we predict with static in vitro digestion models? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 2239–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, İ. Antioxidants: A comprehensive review. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 1893–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Beltagi, H.S.; Eshak, N.S.; Mohamed, H.I.; Bendary, E.S.A.; Danial, A.W. Physical Characteristics, mineral content, and antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Punica granatum or Citrus sinensis peel extracts and their applications to improve cake quality. Plants 2022, 11, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.; Huang, M.; Xiong, Q.; Liang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J. Green and efficient approach to extract bioactive flavonoids with antioxidant, antibacterial, antiglycation, and enzyme inhibitory activities from navel orange peel. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 38, 101479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasmine, N.; Surya, R. Effect of adding mulberry juice and orange peel extract on the antioxidant activity and vitamin C content of jelly candy. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2025, 1488, 012100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abinaya, K.; Sharmila, K.; Priya, S.; Ponmozhi, M.; Linekha, R. Valorization of surplus onion for the development and characterization of antioxidant-rich gummies. Food Hydrocol. Health 2023, 3, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira-Lemos, E.; Almeida, A.R.; Vouga, B.; Morais, C.; Correia, I.; Pereira, P.; Guiné, R.P.F. Development and characterization of healthy gummy jellies containing natural fruits. Open Agric. 2021, 6, 466–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).