Abstract

High-pressure pipelines in nuclear power plants (NPPs) are prone to structural failures, and the study of their failure behavior is essential to analyze and minimize damage to the surrounding structures and components. The prediction of the extent of damage is also a key parameter when designing the surrounding structures. This prediction holds significant importance, since a substantial number of NPPs globally are approaching the 60-year mark in their operational lifespan. Consequently, it becomes imperative to formulate sophisticated methodologies for assessing damage behavior of structures and components under dynamic loading conditions with a more realistic representation of the behavior. This study investigates the damage response resulting from the pipe whip phenomenon in high-pressure pipelines of nuclear power plants through numerical simulations that incorporate damage models for both concrete and steel. The proposed modeling approach was also verified with the results of a ballistics impact study. The finite element modeling (FEM) of the pipe-on-wall-impact (POWI) scenario using ABAQUS helps to implement the damage models of Johnson–Cook (J–C) and Cowper–Symonds (C–S) to steel and the Concrete Damaged Plasticity (CDP) model to concrete using a damage-based approach to determine the extent of damage and failure possibilities. The maximum stresses of the pipe attained 450 MPa for the C–S model and 387 MPa for the J–C model, with the C–S model predicting higher stresses due to its high strain rate sensitivity at extreme loads. By incorporating the damage parameters for the POWI model, a better understanding of the mechanical behavior under impact conditions can be attained.

1. Introduction

Analyzing and studying the pipe whip phenomenon in NPPs is critical owing to its catastrophic consequences from high-energy pipe breaks (HEPBs). In accordance with the recommendations of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the pipe whip effect due to the pipe break must be considered in the safety assessment, and the necessary mitigatory strategies should be followed in the design and maintenance of NPPs [1]. Pipe whipping effect due to a guillotine rupture, causing high-energy displacement, poses a high threat to surrounding structures and the adjacent walls [2]. A thorough understanding of this failure phenomenon is necessary to avoid further damage to the NPP’s internal structural components and develop the reliability of the plant operations.

Several experimental tests were carried out in the past to predict the failure mechanisms and the effect of the failure on the surrounding structures [3,4]. However, in recent years, due to the complexity of the NPP design and the addition of several parameters in the experimental setup, computational techniques were developed and sought after for determining the effect of failure on the system and the surroundings owing to their feasibility and costs [2,5].

Numerous computational models were employed over time to predict the extent of damage from pipe whip impacts and to evaluate the structural response. Kulak & Narvydas [6] validated the NEPTUNE code for pipe whip analysis by utilizing two different models made of pipe elements and plate/shell elements with an economic modeling approach without compromising the accuracy of the behavior. Dundulis et al. [2] evaluated the impact of pipe whip on neighboring walls and group distribution headers (GDHs) due to stress corrosion cracks with transient analysis under conservative loading conditions to prevent failure associated with pipe ruptures. Reid et al. [7] presented the 2D and 3D pipe whip phenomenon of failed high-energy pipe segments to estimate the hazardous zones of pipelines to prevent plant failures and enhance safety. Zaccari [8] studied the impact of pressurized pipe on vertical reinforced concrete columns due to pipe rupture failure in ANSYS v15 using the Johnson–Cook model for the steel and the RHT concrete model for the concrete column. Luo et al. [9] investigated the whipping effect of high-energy pipes based on postulated pipe ruptures with a three-dimensional FE model using the LS-DYNA module of ANSYS to analyze the behavior of restraints and validation with theoretical calculations to justify the application of numerical methods to complex structural and hydrodynamic problems.

Potapov & Galon [5] employed two distinct numerical models (simplified model and a mixed 1D/3D model) using the EUROPLEXUS-2005 fast dynamic software and investigated the pipe whipping phenomenon and validated against the Aquitaine II experimental tests, offering insights into the Fluid–Structure Interactions (FSIs) during high-energy pipe failures. Daude et al. [10] evaluated the accuracy and efficiency of their 1D/3D coupled modeling approach using FSI under fast transient conditions, utilizing the laws of conservation at the 1D and 3D domains and validating their proposed model with analytical methods. Solomon & Dundulis [11] compared the solid 3D FE model against the proposed coupled 1D/3D modeling technique incorporating the FSI approach in ANSYS for studying the pipe whip effect on the adjacent walls of NPPs to decrease the computational time and the finite elements per model using a conservative material modeling approach and validated it with the various available experimental and numerical data. Pate et al. [12] utilized the fluid blowdown pressure data from the experimental tests and formulated a 1D/3D coupling modeling approach using LS-DYNA to efficiently model the pipe whip behavior impacting an adjacent wall and focusing much on the deformation of the steel pipe under large-displacement conditions.

This study presents a validated, damage-based finite element assessment to investigate the structural response of high-pressure pipes and containment walls in nuclear power plants under pipe whip failure events. Unlike prior studies that often rely on simplified wall models or single-material constitutive laws, the present work integrates Johnson–Cook and Cowper–Symonds damage models for steel with the Concrete Damaged Plasticity model for reinforced concrete, enabling realistic prediction of localized damage and stress distribution in the impacted walls. Furthermore, the study provides a comparative assessment of strain-rate-dependent damage models, illustrating their influence on peak pipe stresses, impact force with local damage progression. By incorporating reinforcement and wall damage parameters, this numerical framework delivers engineering-relevant insights for the design, assessment, and safety evaluation of nuclear containment structures, particularly for aging reactors approaching extended operational lifetimes.

2. Methodology

2.1. Benchmark Impact Simulation for Model Verification

To ensure reliability, the ABAQUS/Explicit model was benchmarked against a published LS-DYNA impact simulation using multiple concrete constitutive laws. This validated framework was subsequently used for the Pipe-on-Wall-Impact analyses. The evaluation of the FEM code under impact conditions was performed by simulating a ballistic impact test in ABAQUS in which a rigid cylinder impacts a reinforced concrete slab, as presented through a numerical validation by Sangi & May [13] using LS-DYNA, which was validated from the multiple experimental impact tests conducted at Heriot-Watt University by Izatt et al. [14]. These experimental tests were intended to provide maximum input data for the validation of numerical models for concrete impact. While the availability of comparable experimental datasets for full-scale pipe whip events is limited, the present validation is considered sufficient to demonstrate the reliability of the modeling approach for assessing localized damage in containment structures.

2.1.1. Concrete Constitutive Models

The material models for concrete slabs, which were used in the LS-DYNA validation, were the Winfrith model and the Concrete Damage Rel. 3 model. These models can be used relatively easily in comparison with the existing poorly documented models. Owing to the capability of generating default material input parameters from the primitive material parameters like Poisson’s ratio, compressive strength, etc., these material models find it relatively feasible while modeling dynamic concrete impact simulations [13,15].

Concrete Damage Rel3 Model

The Concrete Damage Rel3 or the Mat 72R3, also referred to as “Karagozian & Case (K&C) Concrete Model”, developed by Malvar et al. [16], is a plasticity-based material model for concrete used in LS-DYNA for simulating the dynamic behavior by incorporating the laws of plasticity and damage mechanics. This model was researched on and developed over time by [17,18,19] to be used in LS-DYNA for dynamic analysis. A total of 49 parameters is needed as input for the full version of this model. However, this model eases the modeling complexity by providing the function of automatically generating the parameters based on the uniaxial unconfined compressive strength of concrete without further characterization of material properties.

Schwer et al. [15] compared their model based on Equations-of-State (EOS) parameters with the laboratory material with only a known parameter (uniaxial unconfined compressive strength of 45 MPa) with a single 8-node solid element utilizing a single-point integration method, and it agreed well with the experimental behavior under isotropic compression, triaxial compression, and uniaxial strain.

Concrete, considered as an isotropic material and under proportional loading conditions, exhibits a direct relationship between the stress and strain and is defined by a failure criterion with three individual stress invariants I1, I2, and I3.

The Concrete Damage Rel3 model utilizes these stress invariants and decomposes the general stress tensor into the deviatoric stress tensor component and the hydrostatic stress tensor component . This model then utilizes these stress invariants to define a yield surface that distinguishes between the elastic and the plastic behavior of the material [20].

Markovich et al. [21] presented an improved model based on the experimental triaxial test data by calibrating a wide range of concretes. This model is suitable for the dynamic behavior in higher strain rates under compression, tension, and typically under impact loading conditions. This model also utilizes the erosion controls to determine the damage under dynamic-high-rate loading conditions and the multi-yield surface approach to determine the material strength based on damage accumulation [15,22].

Winfrith Model

The Winfrith concrete model, or Mat084, is primarily a plasticity model in LS-DYNA for simulating the dynamic behavior of concrete and was originally developed for the nuclear industry to predict the local and global responses to extreme impact loading conditions [23]. This model is based on the four-parameter failure criterion involving all three stress invariants defining the shear failure surface with its response to the different stress states developed by Ottosen [24]. The yield function is given below, where the four parameters, , , , and , are functions of the ratio of the unconfined tensile to the unconfined compressive strength of the concrete. The other parameters of the calculation are explained by Zhu et al. [25].

The Winfrith model, developed in the 1980s, was validated several times over impact and blast loadings to determine the response of the containment structures. The theoretical nature of this model includes a smeared crack (pseudo crack) model with an 8-node continuum element and a single integration point. This model provides strain softening in tension with the effects of strain rate and a tensile cracking up to three orthogonal crack planes [23,26].

The Winfrith model effectively simulates the cracking and the post-failure behavior by incorporating a detailed illustration of crack propagation and damage. The study of the post-failure behavior of concrete is essential to understand its structural response under extreme loading conditions. Wu et al. [27] reviewed and compared the Winfrith model with the K&C model and the Continuous Surface Cap (CSC) model and presented that the Winfrith model includes the effects of strain rate and allows up to three orthogonal crack planes. However, the predictions of the confinement effect of the reinforcements will not be accurate since the shear dilation in this model is not provided.

Concrete Damaged Plasticity (CDP) Model

The Concrete Damaged Plasticity model is a versatile plasticity-based continuum model in ABAQUS, incorporating the laws of damage mechanics by assuming the two major failure characteristics-cracking in tension and crushing in compression [28]. The plastic nature of this model is theoretically presented using the rate-independent inelasticity and through the concepts of continuum damage mechanics based on fracture energy and stiffness degradation [29,30]. The CDP model is the only available constitutive model in ABAQUS that can characterize the brittleness of the concrete along with its cracking and crushing behavior. The damage variables can be incorporated in this model along with the capability to analyze the deterioration progressively, thereby representing the post-failure behavior [28,31,32].

The yield surface function of the built-in CDP model in ABAQUS is represented by a modified Drucker-Prager cone and Rankine tension cutoff, and the yield function is given by,

where are the compressive and tensile cohesive stresses; , effective von Mises and effective hydrostatic stresses; and the effective maximum principal stress, .

where is a material parameter and is obtained through experimental tests and is a parameter describing the yield surface dependency on the ratio of the deviatoric stress in tension and compression.

The CDP model effectively simulates both unconfined and reinforced concrete and allows for the integration of the reinforcements by accurately modeling the interaction between them. The calibration of the model characteristics, such as elasticity, plasticity, and damage, can be controlled based on the predicted behavior of the material under certain load conditions. It also has the capability to represent the dynamic behavior under impact loadings at higher strain rates, where the element deletion algorithm is independent of the element size of the model and dependent on the constitutive parameters of the model (angle of dilation) [33]. The Dynamic Increase Factor (DIF) is a substantial parameter during the dynamic impact loading conditions to represent the strain rate effects dependent on the compressive strength of the concrete, and it can be manipulated accordingly without major changes to the other material parameters [34,35]. Cotsovos et al. [36] compared the non-linear behavior of RC in LS-DYNA, ANSYS, and ABAQUS under monotonic loading at various loading rates and presented that the ABAQUS models predicted good results for brittle and ductile problems with considerations for recalibration based on experimental data.

2.1.2. Description of the FE Model for Verification

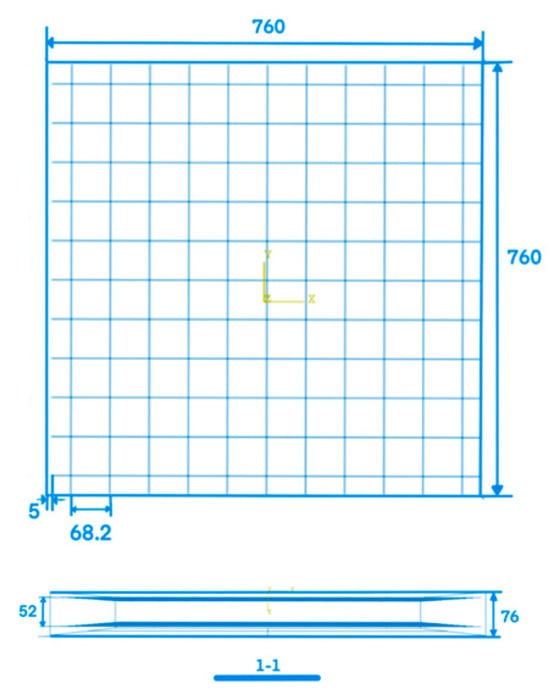

The concrete slab was modeled as a square block of 760 mm length and a thickness of 76 mm with 8-noded hexahedron elements of 10 mm in LS-DYNA. The total cross-sectional area of the RC bar is 181.7 mm2 with a radius of 7.6 mm, and was modeled as beam elements of 10 mm. Further details of the concrete slab with reinforcements are given in Figure 1. The impactor was modeled as a rigid body where both the slab and the impactor were modeled using a single-point Gauss integration method with viscous hourglass controls, and its representation is shown in Figure 2. The LS-DYNA models were solved for Concrete Damage rel3 and Winfrith material modeling for the concrete with *MAT_PLASTIC_KINEMATIC for the reinforcements.

Figure 1.

Details of the concrete slab with reinforcement for the benchmark test.

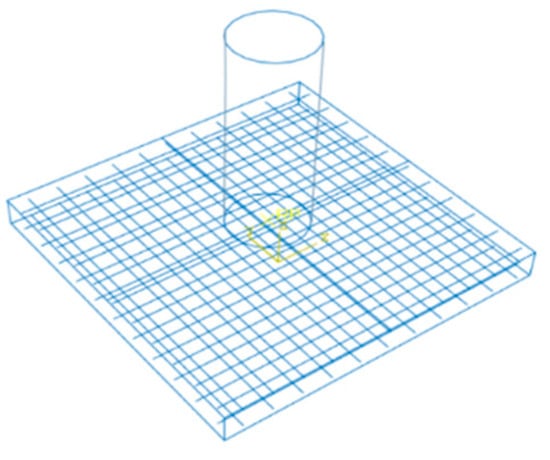

Figure 2.

RC bar representation in the ABAQUS model.

The ABAQUS model features the CDP constitutive model for the concrete slab, with the reinforcements being modeled as a 3D deformable truss with Johnson–Cook damage properties. The impactor was modeled as a rigid body with a mass of 98.7 kg and a velocity up to 6.5 m/s, and a timestep of 0.035s. The concrete slab is discretized into 10 mm linear hexahedral elements of type C3D8R with 53,361 nodes and 46,203 elements. The truss is modeled with 7 mm linear deformable line elements of type B31with 2321 nodes and 2420 elements. The required parameters for the CDP model are presented in Table 1 based on the previous documented research [33,34,35,36,37,38].

Table 1.

ABAQUS CDP model parameters.

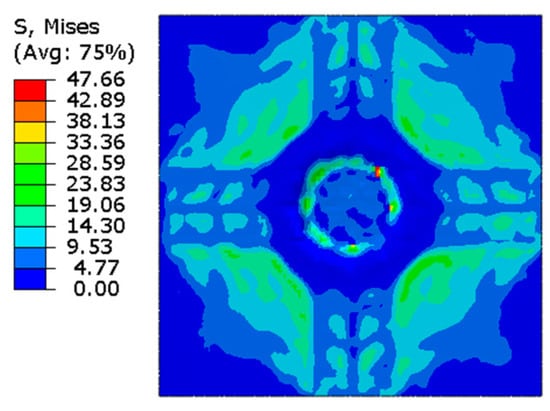

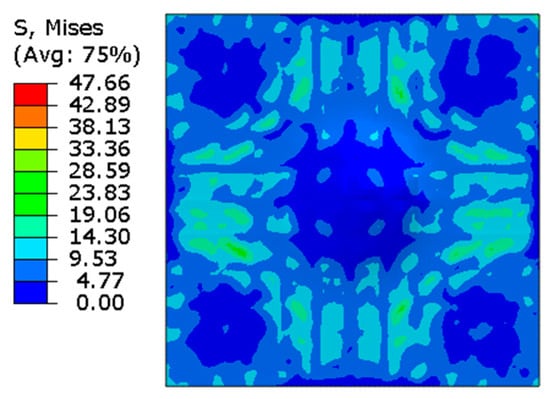

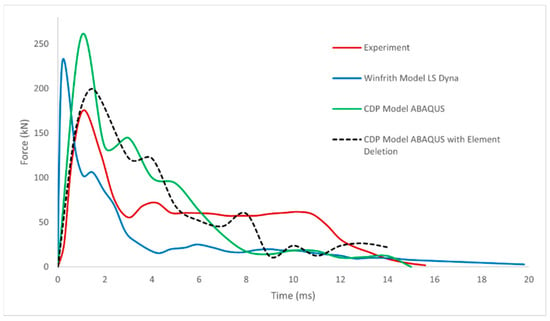

The damage representation of the ABAQUS CDP model (Figure 3 and Figure 4) with the Concrete Damage Rel3 model of LS-DYNA and the experimental results [13] are in good agreement, and therefore, this modeling qualification justifies the accuracy of the CDP model in ABAQUS/CAE 2020 when applied to impact simulations.

Figure 3.

Damage representation in the impact face using ABAQUS CDP.

Figure 4.

Damage representation at the bottom face using ABAQUS CDP.

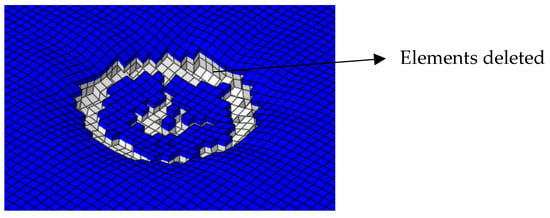

2.1.3. Incorporating Erosion Controls in ABAQUS

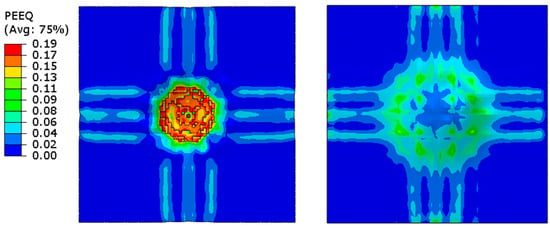

The element deletion/erosion is a methodology of removing the finite elements during an FE simulation in the event of a material failure or damage. The element deletion controls are implemented by presenting a failure criterion before the simulation, and it is applied predominantly to impact scenarios. The selection of this failure criterion plays an important role in determining the outcome of the solution, particularly during an impact test scenario. The element deletion is based on the stress or strain thresholds, where the element is removed when the maximum value of the stress, strain, or any other damage parameter is attained. The plastic strain failure criterion is applied in this simulation to remove the elements once the threshold has been reached, and this approach validates with the experimental data. The plastic strain contour of the top and bottom faces of the concrete slab is presented in Figure 5, and the zoomed-in view of the impact area in Figure 6 shows how the impact affects the surface around the proximity.

Figure 5.

Plastic strain contour in the front and bottom face of the slab considering element deletion.

Figure 6.

Front face of the slab during element deletion.

The presented results in Figure 7 indicate that the numerical simulation results exhibited the closest agreement with the experimental data when the CDP Model with element deletion/erosion was used. The localized effects using erosion controls justify the spalling phase with the ejection of material at the proximity of impact, as seen in Figure 6. Hence, this approach can be applied to the pipe whip impact simulations to determine the damage assessment of the concrete slab when subjected to impact.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the impact force for different models.

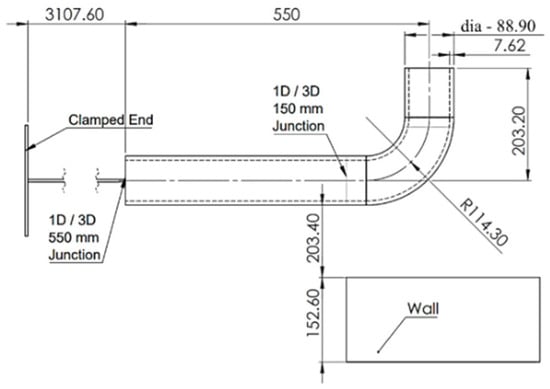

3. Pipe-on-Wall-Impact Modeling and Simulation

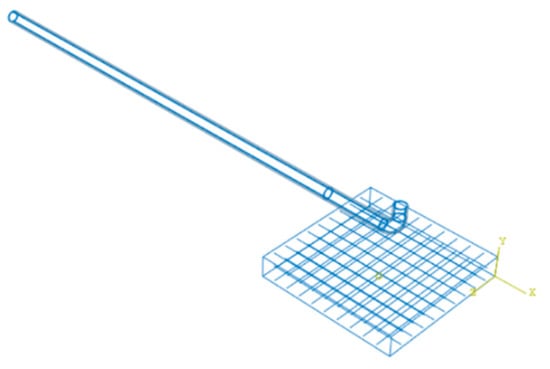

This pipe-on-wall-impact (POWI) model (Figure 8) is an extended work of Pate et al. [12] model by incorporating the damage mechanism to determine damage assessment of concrete structures due to the pipe whip phenomenon. This research extends the previous work by incorporating the damage models of Johnson–Cook and Cowper–Symonds into the reinforcements and a plasticity-based damage model for concrete slab (ABAQUS CDP).

Figure 8.

POWI model dimensions.

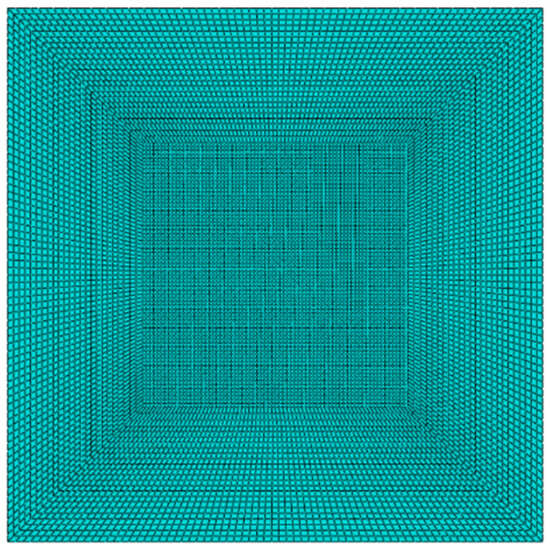

Figure 9 depicts the POWI model setup in ABAQUS, designed separately as three individual parts: the concrete wall, reinforcements, and the steel pipe. The reinforcements are modeled in ABAQUS as a 3D deformable wire and are assembled as trusses and then further embedded with the concrete wall with the help of the constraint manager. In the discretization process, the pipe is partitioned into individual cells along its longitudinal length in such a way that a series of smooth hexahedral linear elements are created along the length of the pipe. A 7 mm C3D8R (a continuum three-dimensional 8-noded linear brick) with reduced integration technique and hourglass controls was assigned to the pipe, and a similar discretization method was followed while modeling the wall with a 15 mm element size. Based on the guidelines proposed by Ding et al. [39], a mesh size of about D/10 (Where D is the breadth of the concrete wall) was employed for the concrete wall to ensure adequate accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency. The selection of a 7 mm element size for the pipe is based on the documented results from Pate et al. [12]. Figure 10 depicts the visual representation of the selected mesh size on the POWI model. The reduced integration technique offers a reduction in the computational time due to the single-point integration per element. Due to the single-point integration, some numerical accuracy arises, which is balanced by the automatic hourglass stiffness offered by ABAQUS [40]. The C3D8R elements in ABAQUS provide an efficiency-accuracy balance during impact computations. These element types are widely used for solving dynamic problems and where the failure criterion is to be determined [41,42,43,44]. The reinforcements were modeled independently with T3D2 truss (2-noded linear 3D truss) elements of 7 mm element size. The T3D2 is a 2-noded three-dimensional truss element commonly used to model reinforcements, where it effectively transfers the axial load to the structures [45,46,47]. The contact between the slab and the reinforcements assumes perfect bonding with an automatic contact algorithm in ABAQUS, and hence, the ease of computation can be enhanced [48].

Figure 9.

POWI model representation in ABAQUS.

Figure 10.

ABAQUS FE model.

The wall has restraints in the horizontal and vertical directions along its bottom edges. The pipe is subjected to a variable amplitude loading with an internal pressure based on the fluidic effects as presented in [11], with a fixed boundary condition at the left end. The total duration of the simulation is 0.02 s and is solved in an explicit solver. The contact between the pipe and the wall is set to a tangential frictionless contact (TFC).

3.1. Material Modeling for POWI

It is desired to realistically predict the structural behavior of NPP components during an impact caused due to the pipe whipping phenomenon. Incorporating a non-linear constitutive model for the pipe, reinforcements, and the concrete slab with a failure criterion will help us to understand the structural responses credibly. Dundulis et al. [2] utilized an elastoplastic material model to capture the effects of steel and reinforced concrete in the event of a guillotine pipe break, with failure mechanisms including gross transverse failure using three-dimensional pipe elements to predict large displacements. Solomon & Dundulis [11] and Pate et al. [12] employed non-linear material properties for the steel pipe to model the plastic behavior under impact, while maintaining a conservative modeling approach for the concrete slab under impact.

The CDP damage model for the concrete slab in ABAQUS is used as the material model and was explained in the previous section. The Johnson–Cook (J–C) and the Cowper–Symonds (C–S) damage models in ABAQUS are both used to describe the strain rate-dependent mechanical behavior of materials, but they vary significantly in their analytical functions and methodologies. Both the J–C and C–S damage models, which were used for the pipe and reinforcements, are described below.

3.1.1. The Johnson–Cook Constitutive Model

The Johnson–Cook (J–C) model [49] is a widely used constitutive plasticity model suited for high strain rate applications owing to its simplicity with the least number of material constants. The J–C model is a function of the von Mises flow stress depending on the plastic strain hardening, plastic strain rate, and thermal softening. The J–C model is expressed in Equation (10) below,

where A is the yield stress, B is the strain hardening constant, C is the strengthening coefficient of strain rate, and m is the coefficient of thermal softening with as the temperature. is the equivalent plastic strain, is the plastic strain rate, and is the reference strain rate. and are the reference temperature and the melting temperature. Some of these material constants are estimated through experimental tests under diverse control environments. The material constants A, B, and n can be obtained with the help of torsion and tension tests, while the Split Hopkinson Pressure Bar (SHPB) test is used to calculate the thermal softening coefficient m at different elevated temperatures [49,50]. The Johnson–Cook material parameters are presented in Table 2 and Table 3 based on the suggestions from previously published relevant research [49,50,51,52,53].

Table 2.

Johnson–Cook model parameters.

Table 3.

Johnson–Cook damage parameters.

The damage law of the Johnson–Cook model [54] is given by

is the effective plastic strain, as the mean stress, and as the effective plastic strain rate with as the failure strain. The parameters , and are the material constants.

3.1.2. The Cowper–Symonds Constitutive Model

The Cowper–Symonds (C–S) model [55] is a widely used efficient elasto-plastic constitutive model to describe the effects of strain rate under plastic deformations for isotropic and kinematic hardening. The C–S model differs from the J–C model by neglecting the effects of temperature and primarily focusing on the effects of strain rate sensitivity. The C–S model is typically used to capture the mechanical responses of the material at higher strain rates with a configuration of strain rate-dependent models where the yield stress is characterized by certain constant parameters [25,56,57,58,59]. The yield stress of the C–S model is expressed by Equation (14) below,

where the strain rate is given by with C being the strain rate constant and p being the strain rate exponent, are the C–S strain rate parameters calculated through analytical methods or derived from literature [60], is the initial yield stress and is the effective plastic strain. is the plastic strain modulus, which is expressed in terms of elastic modulus and tangent modulus . The strain hardening coefficient can be modified from 0 to 1 to describe the kinematic or isotropic hardening.

The steel and concrete material properties are directly taken from [11,12]. The material properties of steel with relevance to typical A106 Grade B steel are considered with a density of 7844 kg/m3, Young’s modulus and the Poisson ratio of 207 GPa and 0.3, with a yield stress and ultimate stress of 220.6 MPa and 461 MPa, respectively. The Johnson–Cook hardening parameters and the damage constants are evaluated based on the available literature [51,53,61,62], which are input in ABAQUS are presented in Table 2 and Table 3. The Cowper–Symonds damage model in ABAQUS follows a hardening-power law where the parameters C (taken as 400 s−1) and p (taken as 0.2) are evaluated based on the available literature [60,63,64].

The fundamental data of concrete, such as density, Young’s modulus, and the Poisson ratio, are 2400 kg/m3, 27 GPa, and 0.2, respectively. The other non-linear and damage parameters of concrete for the Concrete Damaged Plasticity model are the same as that which was presented in Table 1. An equivalent plastic strain parameter is chosen as the element deletion criterion and assigned a value of 0.076 with a multiplier of 1.2 for the damage initiation. The J–C and C–S parameters used in this study were obtained from experimental datasets reported in the literature for steel and concrete grades representative of nuclear power plant piping and containment materials. These constants were derived through dynamic testing methods such as the split Hopkinson pressure bar and ballistic impact experiments in the literature.

The straight end of the pipe is assigned restraints in the horizontal and vertical directions, and a variable amplitude loading is applied on the bent end of the pipe, taken from [12]. A tangential frictionless contact is assigned between the pipe and the slab and solved in an explicit solver for a timestep of 0.02 s [11,12].

4. Results

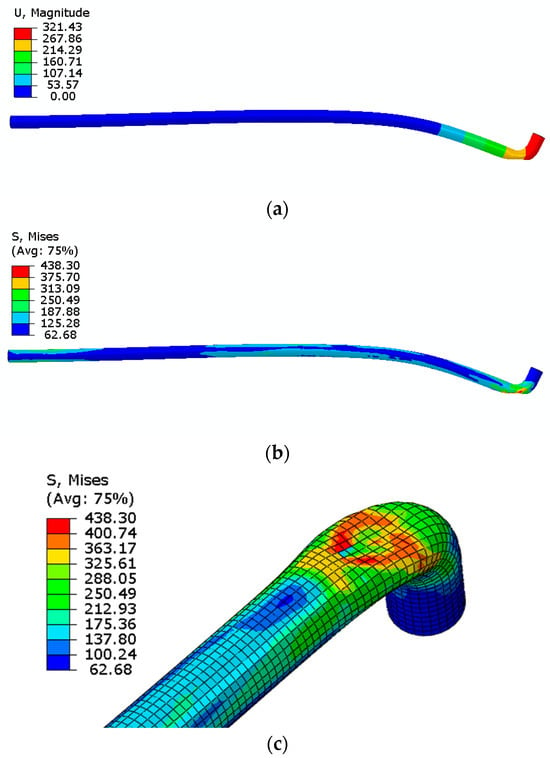

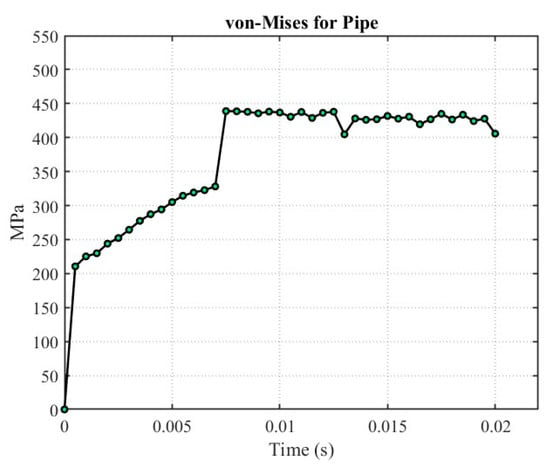

Figure 11a–c shows the structural deformation and the stress contours of the pipe depicting its behavior in the event of a pipe whip phenomenon. The structural behavior and the plastic deformation validate well with the results documented by [12]. The maximum von Mises stresses in the pipe attain 438 MPa in the bent region at the impact location, thereby crushing the pipe, and the behavior agrees well with the previously documented models estimating the pipe behavior under whipping conditions [3,5,10,11,12].

Figure 11.

Contours of displacement (a) and stress contour on the impact face (b,c) of the whipping pipe for non-linear properties of steel.

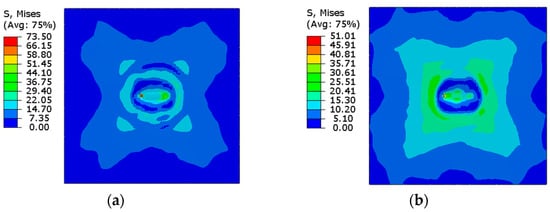

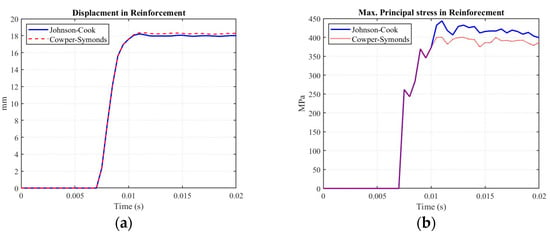

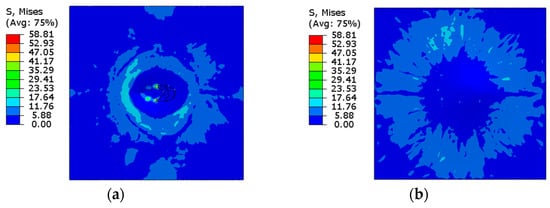

This research provides considerable insights into the structural behavior of the concrete walls of NPPs under pipe whipping conditions, and Figure 12 presents the stresses in the concrete wall due to pipe impact. The J–C and C–S damage models were used for reinforcements, and the ABAQUS CDP model for the concrete to predict the mechanical behavior of reinforced concrete under impact conditions. The results show that the impact region estimates maximum von Mises stresses after the impact and further extends the stresses around the impact region with a sharp peak at the corners. The maximum principal stresses in the reinforcements for the J–C and C–S damage models at the impact are presented in Figure 13, and Figure 14 gives the overall stress response plot over time with the overall response plot is presented in Figure 15b. The J–C model gives a higher principal stress value of 413 MPa when compared to the C–S model of 399 MPa, but the displacement behavior, as shown in Figure 15a, is coherent under the given time-period of 0.02 s. The difference in reinforcement stress between the J–C (413 MPa) and C–S (399 MPa) cases is attributed to the C–S model’s greater strain rate sensitivity, which led to higher stiffness and lower strain transfer into the reinforcement zone under transient dynamic loads.

Figure 12.

Impact face of the concrete wall using (a) Johnson–Cook, (b) Cowper–Symonds.

Figure 13.

Max. Principal stresses in reinforcement using (a) Johnson–Cook, (b) Cowper–Symonds.

Figure 14.

Von Mises stress plot of the pipe with non-linear material properties for steel.

Figure 15.

Displacement plot (a) and the Max. Principal stress plot (b) of the reinforcements incorporating the damage models.

A Complete Damage-Based Model

A complete damage-based model incorporating damage parameters in all the pipe, concrete slab, and reinforcement structures, including a finely discretized concrete slab (Figure 16), utilizing the erosion controls for a more realistic prediction of the dynamic behavior under the pipe whip conditions, is carried out. The response curves of these models are then compared with the previous versions, where the coherence is observed with a better understanding of the impact. The inclusion of the damage properties to the entire model tends to decrease the total stress obtained in the model, and the mechanical behavior can be precisely analyzed.

Figure 16.

Finely discretized concrete wall.

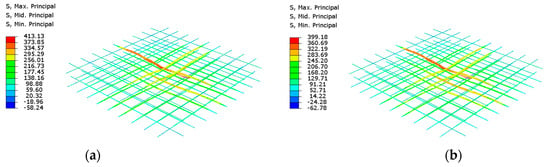

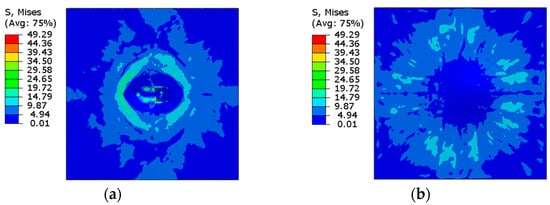

The J–C and C–S damage parameters are added to the material properties of steel and assigned to the pipe and reinforcements with the ABAQUS CDP for concrete, and solved under the exact dynamic conditions by including the erosion controls. The research is dedicated to describing the behavior of the reinforced-concrete wall against the impact of a whipping pipe, and Figure 17 and Figure 18 present the stress distribution on the concrete slab while utilizing a complete and comprehensive damage model. The stress distribution is seen to be steady and radial when compared to the previous version, owing to the inclusion of the element deletion criteria.

Figure 17.

Johnson–Cook and ABAQUS CDP utilized stress contours of the top (a) and bottom (b) face of the concrete wall incorporating erosion controls.

Figure 18.

Cowper–Symonds and ABAQUS CDP utilized stress contours of the top (a) and bottom (b) face of the concrete wall incorporating erosion controls.

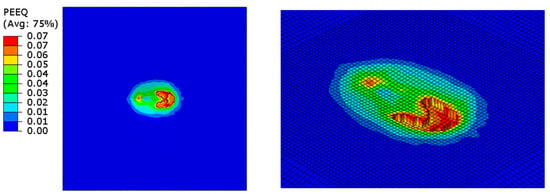

Figure 19 shows the equivalent plastic strain on the concrete where the elements get eroded when it attains an adjusted plastic strain of 0.076 with a multiplier of 1.2. Erosion is seen to be progressively steady at the point of impact on the proximal surface of the concrete wall, and this behavior can be validated from the spalling failure mode, where the material is ejected at the point of contact at the proximal face of the target [65].

Figure 19.

Equivalent plastic strain of the concrete under erosion controls.

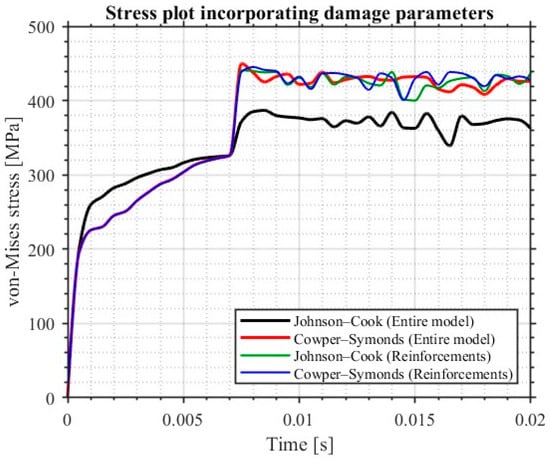

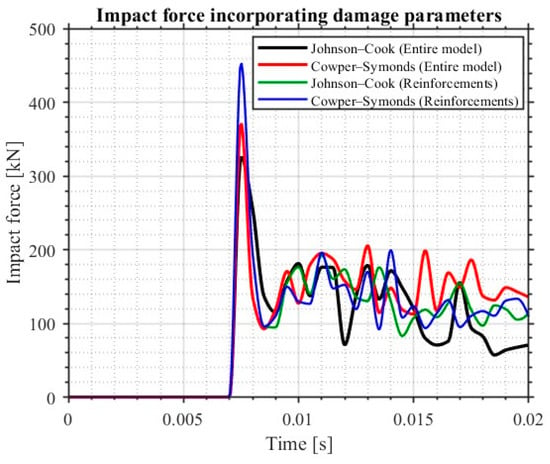

The pipe response and the impact force plot with and without the damage properties for the pipe are presented in Figure 20 and Figure 21. The stress response curves of the pipe without the damage properties behave almost identically to each other, whereas when different damage models are included for the pipe, the response curves tend to differ in their characteristics without deviating much from the actual mechanical behavior. Here, the observed von Mises stress response in the C–S model is greater than that of the J–C model. The observed differences in peak von Mises stress between model combinations are attributable primarily to the strain rate formulations and their interaction with damage evolution. When the C–S model is applied to the entire pipe (including reinforcements), the peak pipe stress rises to 450 MPa, compared with 387 MPa for the J–C formulation. This increase is consistent with the stronger rate-dependent hardening imparted by the C–S relation under the high local strain rates at the impact zone, which delays plastic flow and softening and thus allows higher stress accumulation before damage-mediated relief. This observation can be justified by the C–S model’s extensive sensitivity to the strain rate of the material under dynamic conditions. The C–S model presents faster strain rate hardening, and hence it can yield faster since this model depends on the fundamental parameters of yield stress, which is a function of the strain rate as recorded in the previous research [52,66,67]. By contrast, when only the reinforcement constitutive model is varied while the pipe material model remains unchanged, pipe peak stresses are nearly identical (C–S for reinforcements is 445 and J–C for reinforcements is 441 MPa). This indicates that the pipe’s constitutive characteristics govern the pipe peak stress.

Figure 20.

Von Mises stress plot of the pipe with erosion controls.

Figure 21.

Impact force plot under erosion controls.

The C–S model explicitly incorporates strain rate hardening through the empirical relation, which significantly increases the dynamic yield strength at high strain rates encountered during impact. In contrast, the J–C model includes a logarithmic strain rate term, producing a more moderate hardening response under similar conditions. This difference leads to the higher von Mises stress observed in the C–S model predictions.

The C–S model also predicts a slightly higher impact force than the J–C model, and the response after the impact differs in its characteristics; the damage models produce lower impact force values than the non-damage models. Peak impact forces are primarily governed by the pipe constitutive model and damage evolution. Applying the C–S model to the entire pipe and reinforcements results in a stiffer, rate-sensitive response, producing a higher peak force of 373 kN than the J–C model (326 kN). When the reinforcement model is varied, the pipe dominates the force transmission, yielding nearly identical peaks (455 kN). Lower peaks in the full-damage cases arise from energy dissipation through plasticity and progressive element erosion, with model-dependent timing accounting for the observed differences. The element removal criterion includes a progressive degradation of the material stiffness and hence transmits reduced forces to the adjoining elements, leading to lower stress concentrations.

5. Conclusions

This study presented a detailed numerical investigation of the pipe-on-wall-impact (POWI) scenario in nuclear power plants (NPPs) using ABAQUS with advanced damage models for both steel and concrete. Prior to examining the pipe whip effects, the ABAQUS framework was qualified for impact simulations by benchmarking against published experimental and numerical results, showing strong correlation and reliability.

The Johnson–Cook (J–C) and Cowper–Symonds (C–S) damage models were implemented to simulate the steel pipe and reinforcement behavior, while the Concrete Damaged Plasticity (CDP) model was applied to the reinforced concrete wall. The results demonstrated good agreement with previous studies, with the maximum stress on the impacting pipe reaching approximately 438 MPa. The impact force and stress distribution differed from earlier literature due to the incorporation of damage parameters and reinforcement details in the wall model, providing a more realistic prediction of localized damage.

Comparison of the J–C and C–S models revealed that the C–S model exhibited higher von Mises stresses, reflecting its greater strain rate sensitivity under extreme dynamic loads. Inclusion of progressive erosion controls led to lower peak impact forces and reproduced the spalling failure mode observed experimentally in high-energy impact conditions.

The simulation results predicted localized damage (possible spalling failure) within the walls of the NPP structure in the event of a pipe whip; however, the structural integrity will not be compromised. Spalling failure inside the containment walls does not affect the NPP at a greater cost, but the extent of the damage must be predicted to analyze the surrounding structures adequately. While the results confirm the robustness of the proposed modeling framework, the study is limited by using literature-based material parameters and a single benchmark validation case. Future work will aim to include experimental validation and fracture-based failure analysis to further enhance the predictive accuracy of the model. This numerical approach, by incorporating damage modeling, proved to be acceptable in determining such localized damage in NPP’s internal structures and walls.

The numerical predictions of localized wall damage, peak pipe stresses, and impact force histories presented in this study have direct implications for the safety assessment and design of aging NPPs. By quantifying the extent of damage during potential pipe whip events, the results can guide containment wall design, structural reinforcement strategies, and evaluation of surrounding components to minimize risk. Furthermore, the comparative performance of the Johnson–Cook and Cowper–Symonds damage models provides insight into material behavior under extreme dynamic loading, enabling more accurate simulations for safety analysis. These findings support mitigation planning, code validation, and operational decision-making in existing and long-term NPP operations, particularly for facilities approaching or exceeding 60 years of service life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.D. and R.L.F.; methodology, I.S.; software, I.S. and K.G.; validation, K.G., G.D., and R.L.F.; formal analysis, I.S.; investigation, I.S.; resources, I.S., K.G., G.D., and R.L.F.; writing—original draft preparation, I.S.; writing—review and editing, I.S.; visualization, G.D. and R.L.F.; supervision, G.D. and R.L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been partially supported by the ENEN2plus project (HORIZON-EURATOM-2021-NRT-01-13 101061677), funded by the European Union.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NPP | Nuclear Power Plant |

| POWI | Pipe-on-Wall-Impact |

| CDP | Concrete Damaged Plasticity |

| J–C | Johnson–Cook |

| C–S | Cowper–Symonds |

References

- International Atomic Energy Agency. Protection Against Internal and External Hazards in the Operation of Nuclear Power Plants; IAEA Safety Standards Series No. SSG-77; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dundulis, G.; Uspuras, E.; Kulak, R.F.; Marchertas, A. Evaluation of Pipe Whip Impacts on Neighboring Piping and Walls of the Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2007, 237, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.C.; Kuo, A.Y.; Tang, H.T. Nonlinear Analysis of Pipe Whip. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Structural Mechanics in Reactor Technology (SMiRT 8), F1 4/6. Brussels, Belgium, 19–23 August 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki, N.; Ueda, S.; Isozaki, T.; Kurihara, R.; Yano, T.; Kato, R.; Miyazono, S. Experimental and Analytical Studies of Four-Inch Pipe Whip Tests under PWR LOCA Conditions. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 1984, 15, 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapov, S.; Galon, P. Modelling of Aquitaine II Pipe Whipping Test with the EUROPLEXUS Fast Dynamics Code. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2005, 235, 2045–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulak, R.F.; Narvydas, E. Verification of the NEPTUNE Computer Code for Pipe Whip Analysis. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Structural Mechanics in Reactor Technology (SMiRT 16), Washington, DC, USA, 12–17 August 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, S.R.; Wang, B.; Aleyaasin, M. Structural Modelling and Testing of Failed High Energy Pipe Runs: 2D and 3D Pipe Whip. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2011, 88, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccari, N. High Energy Pipe Break Analysis for the Pipelines of a Nuclear Power Plant: No Standard Case. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2015, 56, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, W. Analysis of Whipping Effect on High Energy Pipe in a Nuclear Power Plant. Fusion Eng. Des. 2020, 150, 111359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daude, F.; Galon, P.; Douillet-Grellier, T. 1D/3D Finite-Volume Coupling in Conjunction with Beam/Shell Elements Coupling for Fast Transients in Pipelines with Fluid–Structure Interaction. J. Fluids Struct. 2021, 101, 103219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, I.; Dundulis, G. Modeling of Pipe Whip Phenomenon Induced by Fast Transients Based on Fluid–Structure Interaction Method Using a Coupled 1D/3D Modeling Approach. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pate, S.B.; Solomon, I.S.M.; Dundulis, G.; Griskevicius, P. Applications of the FEM to Pipe Whip Analysis Using Coupled Modelling Technique. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2024, 418, 112941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangi, A.J.; May, I.M. High-Mass, Low-Velocity Impacts on Reinforced Concrete Slabs. In Proceedings of the 7th European LS-DYNA Conference, Salzburg, Austria, 14–15 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Izatt, C.; May, I.M.; Lyle, J.; Chen, Y.; Algaard, W. Perforation Owing to Impacts on Reinforced Concrete Slabs. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Struct. Build. 2009, 162, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwer, L.E.; Malvar, L.J. Simplified Concrete Modeling with* MAT_CONCRETE_DAMAGE_REL3. In Proceedings of the 4th German LS-DYNA Forum, Bamberg, Germany, 14–15 October 2005; pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Malvar, L.J.; Crawford, J.E.; Wesevich, J.W.; Simons, D. A Plasticity Concrete Material Model for DYNA3D. Int. J. Impact Eng. 1997, 19, 847–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvar, J.; Crawford, J.; Wesevich, J.; Simons, D. A New Concrete Material Model for DYNA3D. In Proceedings of the Engineering Mechanics, Boulder, CO, USA, 21–24 May 1995; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 1995; pp. 142–146. [Google Scholar]

- Malvar, L.J.; Crawford, J.E.; Wesevich, J.W.; Simons, D. A New Concrete Material Model for DYNA3D Release II: Shear Dilation and Directional Rate Enhancements. In A Report to Defense Nuclear Agency under Contract No DNA001-91-C-0059; Defense Nuclear Agency: Alexandria, VA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Malvar, L.J.; Crawford, J.E.; Morrill, K.B. K&C Concrete Material Model Release III-Automated Generation of Material Model Input. In Karagozian and Case Structural Engineers; Technical Report TR-99-24.3; Defense Nuclear Agency: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Abedini, M.; Zhang, C. Performance Assessment of Concrete and Steel Material Models in LS-DYNA for Enhanced Numerical Simulation, A State of the Art Review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2021, 28, 2921–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovich, N.; Kochavi, E.; Ben-Dor, G. An Improved Calibration of the Concrete Damage Model. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 2011, 47, 1280–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Kong, X.; Qu, Y.; Zhao, Q. Numerical Simulation of Cracked Reinforced Concrete Slabs Subjected to Blast Loading. Civ. Eng. J. 2018, 4, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadhouse, B. The Winfrith Concrete Model in Ls-Dyna3d; Report SPD/D(95)363; AEA Technology: Carlsbad, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ottosen, N.S. Failure and Elasticity of Concrete; Danish Atomic Energy Commission: Roskilde, Denmark, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Li, J.; Lin, G.; Pan, R.; Li, L. Sensitivity Analysis of Steel-Plate Concrete Containment against a Large Commercial Aircraft. Energies 2021, 14, 2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwer, L.E. An Introduction to the Winfrith Concrete Model; Schwer Engineering & Consulting Services: Windsor, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Crawford, J.E.; Magallanes, J.M. Performance of LS-DYNA Concrete Constitutive Models. In Proceedings of the 12th International LS-DYNA Users Conference, Dearborn, MI, USA, 3–5 June 2012; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M. ABAQUS/Standard User’s Manual, Version 6.9; Dassault Systèmes Simulia Corp.: Waltham, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lubliner, J.; Oliver, J.; Oller, S.; Oñate, E. A Plastic-Damage Model for Concrete. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1989, 25, 299–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Fenves, G.L. Plastic-Damage Model for Cyclic Loading of Concrete Structures. J. Eng. Mech. 1998, 124, 892–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakeh, M.; Jawdhari, A.; Fam, A. Calibration of ABAQUS Concrete Damage Plasticity (CDP) Model for UHPC Material. In Proceedings of the Third International Interactive Symposium on Ultra-High Performance Concrete, Wilmington, DE, USA, 4–7 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Le Thanh, C.; Minh, H.-L.; Sang-To, T. A Nonlinear Concrete Damaged Plasticity Model for Simulation Reinforced Concrete Structures Using ABAQUS. Frat. Integr. Strutt. 2021, 16, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedoroff, A.; Calonius, K. Using the Abaqus CDP Model in Impact Simulations. Raken. Mek. 2020, 53, 180–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concrete, I. Fib Model Code for Concrete Structures 2010; Ernst Sohn Publ.: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Le Minh, H.; Khatir, S.; Abdel Wahab, M.; Cuong-Le, T. A Concrete Damage Plasticity Model for Predicting the Effects of Compressive High-Strength Concrete under Static and Dynamic Loads. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 103239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotsovos, D.M.; Zeris, C.A.; Abbas, A.A. Finite Element Modelling of Structural Concrete. In Proceedings of the ECCOMAS Thematic Conference on Computational Methods in Structural Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering, Rhodes, Greece, 15–18 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- FIB-Federation Internationale du Beton. Fib Model Code for Concrete Structures 2010; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 9783433030615. [Google Scholar]

- Sadat, S.I.; Ding, F.-X.; Wang, M.; Lyu, F.; Akhunzada, K.; Xu, H.; Hui, B. Behavior and Reliable Design Methods of Axial Compressed Dune Sand Concrete-Filled Circular Steel Tube Columns. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Cao, Z.; Lyu, F.; Huang, S.; Hu, M.; Lin, Q. Practical Design Equations of the Axial Compressive Capacity of Circular CFST Stub Columns Based on Finite Element Model Analysis Incorporating Constitutive Models for High-Strength Materials. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16, e01115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-S.; Ryu, C.-H.; Kim, H.-S.; Choi, Y.-J. A Study on the Free Drop Impact of a Cask Using Commercial FEA Codes. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2005, 235, 2219–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Niu, B.; Zhou, C.; Chen, Z.; Dong, Z.; Zhou, Y. Optimization of Non-Prestressing Reinforcement around the Equipment Hatch of a Prestressed Concrete Containment Vessel. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2023, 411, 112420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanifehzadeh, M.; Gencturk, B.; Willam, K. Dynamic Structural Response of Reinforced Concrete Dry Storage Casks Subjected to Impact Considering Material Degradation. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2017, 325, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, D.; Li, S.; Jiang, Y. Design and Dynamic Analysis of Transport Cask for SMR Fresh Fuel Assembly. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2024, 423, 113183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, A.K.; Pathak, R.K.; Patel, S. Design and Analysis of Hybrid Composite Panels under Ballistic Impact. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 87, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Wang, X.; Ashour, A.; Sun, T.; Dong, S.; Han, B. Blast-Resistance Characteristics and Design of Steel Wire Reinforced Ultra-High Performance Concrete Slabs. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2024, 193, 105059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.A.; Rajput, A.; Gupta, N.K. Performance of Prestressed Concrete Targets against Projectile Impact. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2017, 110, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xie, P.; Feng, B.; Hong, J.; Fang, Q. A Modified K&C Model for Concrete Subjected to Coupled Effect of High Temperature and High Strain Rate. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2023, 181, 104760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balomenos, G.P.; Pandey, M.D. Probabilistic Finite Element Investigation of Prestressing Loss in Nuclear Containment Wall Segments. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2017, 311, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.R.; Cook, W.H. Fracture Characteristics of Three Metals Subjected to Various Strains, Strain Rates, Temperatures and Pressures. Eng. Fract. Mech. 1985, 21, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, H.S.; Kim, J.S.; Han, J.J.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, Y.J. Ductile Fracture Simulation for A106 Gr.B Carbon Steel under High Strain Rate Loading Condition. In Recent Advances in Structural Integrity Analysis—Proceedings of the International Congress (APCF/SIF-2014); Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gkolfinopoulos, I.; Chijiwa, N. Determination of Johnson–Cook Material and Failure Model Constants for High-Tensile-Strength Tendon Steel in Post-Tensioned Concrete Members. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwer, L. Optional Strain-Rate Forms for the Johnson Cook Constitutive Model and the Role of the Parameter Epsilon_0. In Proceedings of the 6th European LS_DYNA Users’ Conference, Gothenburg, Sweden, 28–29 May 2007; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, H.-S.; Je, J.-H.; Han, J.-J.; Kim, Y.-J. Investigation of Crack Tip Stress and Strain Fields at Crack Initiation of A106 Gr. B Carbon Steels under High Strain Rates. Procedia Mater. Sci. 2014, 3, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lesuer, D. Experimental Investigations of Material Models for Ti-6AL4V and 2024-T3; Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory: Livermore, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Cowper, G.R.; Symonds, P.S. Strain Hardening and Strain Rate Effect in the Impact Loading of Cantilever Beams; Defense Technical Information Center: Fort Belvoir, VA, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Hernandez, C.; Maranon, A.; Ashcroft, I.A.; Casas-Rodriguez, J.P. A Computational Determination of the Cowper–Symonds Parameters from a Single Taylor Test. Appl. Math. Model. 2013, 37, 4698–4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyliene, V.; Ostasevicius, V. Cowper-Symonds Material Deformation Law Application in Material Cutting Process Using LS-DYNA FE Code: Turning and Milling. In Proceedings of the in Proceedings of the 8th European LS-DYNA User’s Conference, Strasbourg, France, 15–17 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marangoni, A.L.; Massaroppi, E. Cowper-Symonds Parameters Estimation for ABS Material Using Design of Experiments with Finite Element Simulation. Polimeros 2017, 27, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Škrlec, A.; Klemenc, J. Estimating the Strain-Rate-Dependent Parameters of the Cowper-Symonds and Johnson-Cook Material Models Using Taguchi Arrays. Stroj. Vestn. J. Mech. Eng. 2016, 62, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N. Structural Impact; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Murugesan, M.; Jung, D. Johnson Cook Material and Failure Model Parameters Estimation of AISI-1045 Medium Carbon Steel for Metal Forming Applications. Materials 2019, 12, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Basaran, C. A Review of Damage, Void Evolution, and Fatigue Life Prediction Models. Metals 2021, 11, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belingardi, G.; Chiandussi, G.; Ibba, A. Identification of Strain-Rate Sensitivity Parameters of Steel Sheet by Genetic Algorithm Optimisation. In Proceedings of the High Performance Structures and Materials III; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 2006; pp. 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Škrlec, A.; Panić, B.; Nagode, M.; Klemenc, J. Estimating the Cowper–Symonds Parameters for High-Strength Steel Using DIC Combined with Integral Measures of Deviation. Metals 2024, 14, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.P. A Review of Procedures for the Analysis and Design of Concrete Structures to Resist Missile Impact Effects. Nucl. Eng. Des. 1976, 37, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selyutina, N.S.; Petrov, Y.V. Comparative Analysis of Dynamic Plasticity Models. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2018, 57, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, E.; Ekstrøm, K.; Alfredsson, B. Experimental Investigation of the Strain Rate Dependence of SS 2506 Gear Steel. Master’s Thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).