Abstract

Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) are recognized hotspots for the convergence and dissemination of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria (ARB) and antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) into the environment. Among ARB, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CR-E) and extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae (ESBL-Ec/Kp) are of particular concern due to their clinical relevance. We characterized 30 CR-E and 176 ESBL-Ec/Kp isolates (two of them were both ESBL-producing and carbapenem-resistant) recovered from influent, intermediate, effluent, sludge, and downstream river samples collected from two WWTPs in northern Spain. Isolates were evaluated for resistance phenotypes against 12 antimicrobials, and β-lactamase-encoding genes were assessed by PCR and sequencing. Notably, among CR-E isolates, blaKPC-2 was the most prevalent (93%), followed by blaOXA-48-like, detected in two isolates from non-treated and pasteurized sludge; both isolates also carried blaCTX-M-15, a finding not previously reported specifically in sludge samples. Among ESBL-Ec/Kp, a broad diversity of ESBL genes was identified, including blaCTX-M group 1 (variants 1, 3, 15, 32, 55), blaCTX-M group 9 (variants 14, 27, 65, 97), blaSHV-12 and blaTEM-169. The most prevalent ESBL gene was blaCTX-M-15 (48.3%), followed by blaCTX-M-14, blaCTX-M-32, and blaSHV-12, detected in 10.8%, 8.5%, and 6.8% of isolates, respectively. CR-E and ESBL-Ec/Kp were found in all sample types and were still detectable at terminal stages, indicating persistence throughout treatment. These findings support the need to improve and optimize current wastewater treatment methods and underscore the importance of integrating culture-based and molecular methods into routine WWTP monitoring for early detection of microbiological hazards, although further research is still needed.

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is currently a silent pandemic that has become a global concern and represents a serious public health problem [1,2]. Antimicrobial resistant bacteria (ARB) have been detected not only in human and animal clinical settings, but also in the environment [3], a less studied aspect that plays a key role in the spread of this problem [4,5,6]. Aquatic environments, especially wastewater from anthropogenic activities, are important reservoirs for the convergence and spread of ARB and antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) into the environment, as well as for selection of resistance. In this context, wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) play a crucial role as hotspots, underscoring the need for surveillance and increased awareness of clinically relevant ARB [7,8].

Among all ARB, Enterobacterales are particularly concerning. These Gram-negative bacteria are commensals of the intestinal microbiota but can also act as opportunistic pathogens capable of acquiring clinically relevant ARGs, such as those encoding Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases (ESBL) and carbapenemases, which confer resistance to third-generation cephalosporins and carbapenems [9,10].

According to the latest World Health Organization (WHO) Bacterial Priority Pathogens List (BPPL), carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CR-E) and third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacterales are included in the Critical Group as ARB pathogens that pose the highest threat to public health due to limited treatment options [11]. The latest report of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control [12] also highlights the CR-E situation in Europe, pointing out that the epidemiological situation in the EU/EEA is deteriorating.

Wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) is needed to better understand the mechanisms involved and to establish more effective control strategies to prevent the emergence and spread of relevant ARB from the One Health perspective, as is the case of CR-E and ESBL-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates (ESBL-Ec/Kp). The presence of CR-E and ESBL-Ec/Kp in WWTPs has crucial implications for public health, and for the control of ARB infections and environmental contamination.

Wastewater entering WWTPs originates from multiple sources, such as hospitals, industries, and households, among others. Therefore, the presence of ARB in the influent is a clear indicator that they are circulating within the population and also enables the identification of different variants of their ARGs. In some cases, they can even be detected earlier in WWTP influent than in the original sources, making this approach a valuable tool for early detection.

On the other hand, their detection in the effluent provides information on the efficiency of wastewater treatment in eliminating or reducing the load of these ARB. Their release into receiving water facilitates their spread in the environment. This environmental impact can be monitored in the river downstream of the WWTP discharge point [8,13].

Another important point to consider is the use of sewage sludge generated, as it may contain these ARB, which can be introduced into agricultural fields if not properly stabilized when the sludge is applied as a fertilizer (organic amendment or compost).

Among the strategies for WBE, in the last decade, due to the significant development of molecular techniques, studies on bacterial diversity in complex ecosystems such as wastewater and sewage sludge have primarily relied on the use of culture-independent methods. These methods provide a more comprehensive analysis of bacterial diversity at the phylum, class, and genus levels due to their high accuracy and efficiency.

However, culture-dependent studies also remain fundamental, as they allow for the detection, characterization, and viability assessment of ARB. This approach is of great importance and indispensable, especially for informing on the potential microbiological hazards and public health impact associated with the presence of antimicrobial resistant culturable bacteria, particularly those relevant in human clinical settings. Both approaches, with their advantages and limitations, are not mutually exclusive but complementary, and their combination can enhance the surveillance and control of the spread of AMR in aquatic ecosystems [4,14].

Our research group previously conducted a surveillance study on AMR at two WWTPs associated with different anthropogenic activities in northern Spain, using culture-dependent methodologies [4]. This approach enabled the recovery of CR-E and ESBL-Ec/Kp isolates at various stages of wastewater treatment and sludge stabilization, recovered in chromogenic selective media and identified by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-Of-Flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). The present work aimed to further characterize these CR-E and ESBL-Ec/Kp isolates recovered from the environment of the two WWTPs, determining their antibiotic resistance phenotypes and characterizing the variants of β-lactamases (both carbapenemases and ESBLs) and their distribution in the types/origins of samples of the WWTP providing key information on their viability, resistance, and potential dissemination in the environment.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Workflow Methodology

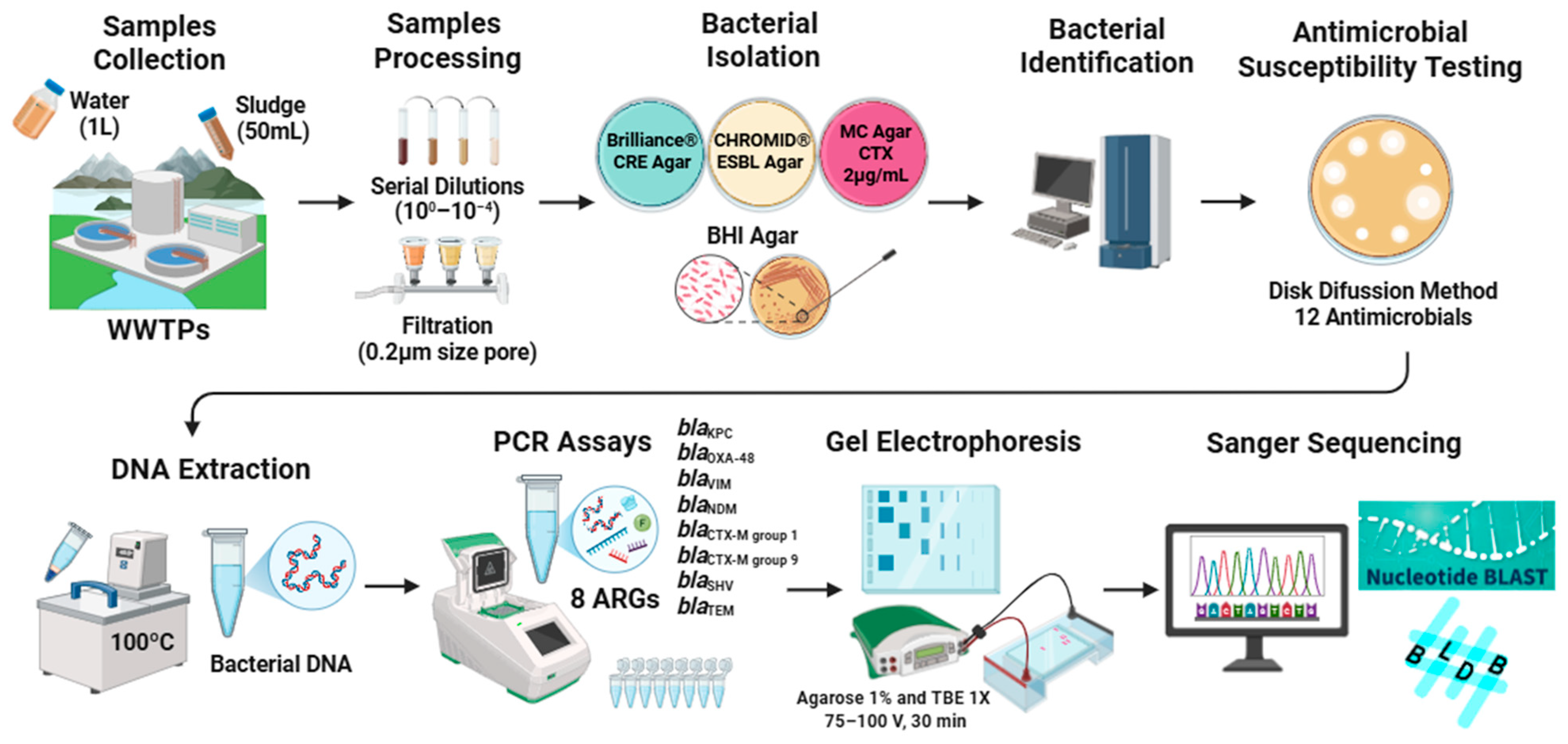

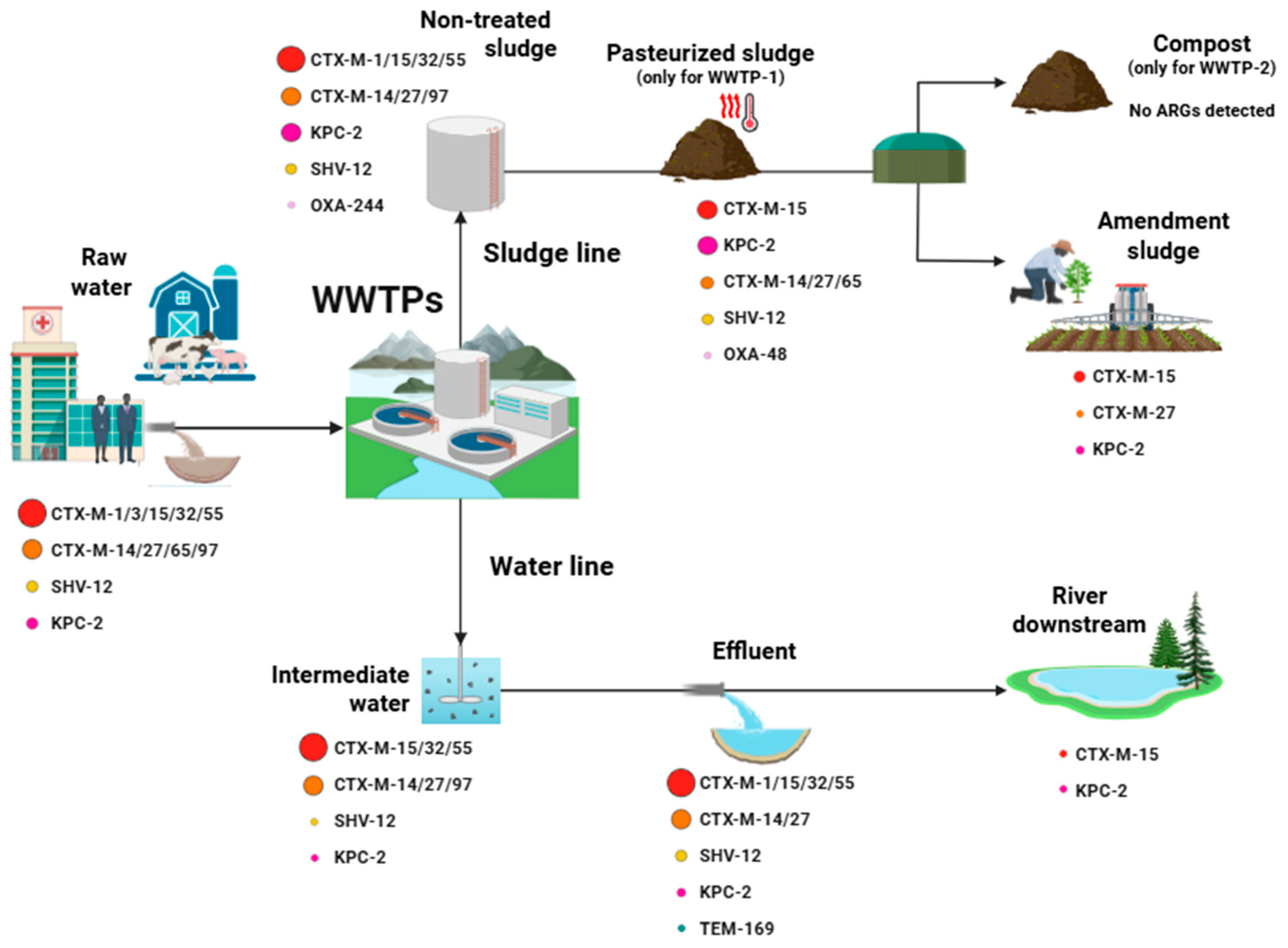

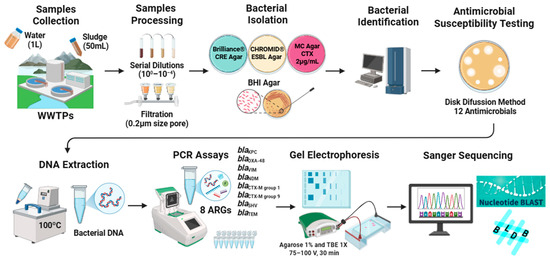

The workflow methodology followed is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Workflow methodology followed.

2.2. Sample Collection, Processing, and Bacterial Isolation and Identification

In a previous study conducted in the La Rioja region (northern Spain) between January 2022 and December 2023, ninety-four samples (48 water/46 sludge) were collected at different treatment stages from two WWTPs (WWTP-1 and WWTP-2) and they were processed for CR-E and ESBL-Ec/Kp recovery [4]: the obtained isolates were characterized in the present study.

As a complement to that study, 2 additional samples were collected 100 m river downstream of the WWTP-1 discharge point and were processed in the present study.

Samples were kept cold on ice (0–4 °C) during transport to the laboratory and processed prior to inoculation as described previously, by preparing serial decimal dilutions (100–10−4) in Milli-Q water or previously filtered through cellulose acetate membranes, pore size 0.22 µm depending on sample type/origin.

Samples were inoculated on different culture media according to the methodology described in our previous study [4]. The chromogenic media Brilliance® CRE Agar (Oxoid, Madrid, Spain) was used for the isolation of CR-E; while CHROMID® ESBL Agar (BioMerieux, Madrid, Spain) and MacConkey Agar supplemented with 2 µg/mL of cefotaxime (Condalab, Madrid, Spain) were both used for the isolation of ESBL-Ec/Kp.

The isolates were identified using Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-Of-Flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF). For this assay, the standard protein extraction protocol recommended by Bruker (Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) was followed (MALDI-TOF Biotyper®, Bruker). The bacterial collection was preserved in Difco™ Skim Milk (Becton, Pont-de-Claix, France) at −80 °C until characterization.

2.3. Isolates Included in the Study

In total, 204 isolates were analyzed, 202 obtained from the previous study [4] and two newly recovered from river samples. The collection comprised 30 CR-E and 176 ESBL-Ec/Kp isolates, including two isolates that were both ESBL-producing and carbapenem-resistant.

2.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility tests were performed for all CR-E and ESBL-Ec/Kp isolates by the disk-diffusion method on Mueller Hinton agar plates to evaluate susceptibility to 12 antimicrobials: ampicillin (AMP), amoxicillin-clavulanate (AMC), cefotaxime (CTX), ceftazidime (CAZ), cefoxitin (FOX), imipenem (IPM), ciprofloxacin (CIP), tetracycline (TET), tobramycin (TOB), gentamicin (GEN), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT) and chloramphenicol (CHL). The breakpoints established by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) were used [15], except for two antibiotics (CTX and TET) for which the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) criteria were applied [16]. Isolates were considered multidrug resistant (MDR) if resistance to at least three antimicrobial drug families was detected.

The double-disk synergy test for evaluating ESBL production was also performed on Mueller–Hinton agar plates, using CTX and CAZ disks placed 30 mm (center to center) from an AMC disk. The test was considered positive when reduced susceptibility to CTX and CAZ was accompanied by a clear extension of the inhibition zone of these antibiotics toward the AMC disk, resulting in the characteristic “keyhole” or “champagne-cork” shape [17].

2.5. DNA Extraction

Bacterial DNA was extracted using the boiling-method for all CR-E and ESBL-Ec/Kp isolates. A single colony from an overnight culture was suspended in 1 mL Milli-Q water (Merck, Barcelona, Spain) and vortexed. The cell wall was lysed by boiling for 8 min and the precipitate was removed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 2 min. Then the supernatant was used as the source of template for PCRs [18]. The DNA concentration of each bacterial sample was measured in the range of 300 to 500 ng/µL using a NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Madrid, Spain).

2.6. Molecular Detection of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes (ARGs)

The presence of eight different β-lactamase genes related with carbapenemases and ESBL was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in a Multi Block PCR Thermal Cycler (Analytik, Jena, Germany): blaKPC (F-GTATCGCCGTCTAGTTCTGC, R-GGTCGTGTTTCCCTTTAGCC, amplicon size 638 bp); blaOXA-48 (F-TTGGTGGCATCGATTATCGG, R-GAGCACTTCTTTTGTGATGGC, amplicon size 744 bp); blaVIM (F-GATGGTGTTTGGTCGCATA, R-CGAATGCGCAGCACCAG, amplicon size 390 bp); blaNDM (F-GGTTTGGCGATCTGGTTTTC, R-CGGAATGGCTCATCACGATC, amplicon size 621 bp), and blaCTX-M group 1 (F-GTTACAATGTGTGAGAAGCAG, R-CCGTTTCCGCTATTACAAAC, amplicon size 1041 bp); and blaCTX-M group 9 (F-GTGACAAAGAGAGTGCAACGG, R-ATGATTCTCGCCGCTGAAGCC, amplicon size 857 bp), blaSHV (F-CACTCAAGGATGTATTGTG, R-TTAGCGTTGCCAGTGCTCG, amplicon size 885 bp) and blaTEM (F-ATTCTTGAAGACGAAAGGGC, R-ACGCTCAGTGGAACGAAAAC, amplicon size 1150 bp). All PCR assays included positive and negative controls from the strain collection of the University of La Rioja. PCR conditions for detection of all ARGs analyzed are shown in Table S1 [19,20,21,22,23].

To visualize the PCR amplicons, a 1% agarose gel in 1× TBE (Tris/Borate/EDTA) was run at 75–100 V for 30 min. This allowed the separation of the amplified bacterial DNA fragments by size. Bands at the same height as the positive control indicated the presence of ARGs. The bands were visualized using a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

All positive PCR amplicons were subjected to Sanger sequencing (Genewiz, Leipzig, Germany) to determine the variants of the β-lactamase genes, The resulting sequences were analyzed using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST+ 2.17.0) [24], which compares query sequences against reference genetic databases. This analysis allowed the validation of gene identification and confirmed whether the studied strains carried the respective ARGs.

Subsequently, the Beta-Lactamase Database (BLDB) [25] was consulted to verify whether the identified alleles were associated with an ESBL phenotype, as only some blaSHV and blaTEM variants confer it.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the Bacterial Collection

Thirty imipenem-resistant (IPMR) isolates were recovered, representing five genera and 13 species as follows (number of isolates): Citrobacter (11), Enterobacter (10), Klebsiella (5), Escherichia (2) and Raoultella (2). Of the total 30 CR-E isolates, 13.3% (n = 4) were obtained from raw water, 3.3% (n = 1) at intermediate treatment steps, 16.7% (n = 5) in the effluent, and 3.3% (n = 1) in river downstream samples. Regarding sludge stabilization, 23.3% (n = 7) of the CR-E were recovered from non-treated sludge, 26.7% (n = 8) from pasteurized sludge (intermediate) and 13.3% (n = 4) in the amendment sludge samples.

Among the 176 ESBL-Ec/Kp isolates, 93.2% (n = 164) were E. coli and 6.8% (n = 12) K. pneumoniae. of the total, 45.5% (n = 80) were recovered from raw water, 7.4% (n = 13) at intermediate treatment steps, 22.2% (n = 39) in the effluent, and 0.6% (n = 1) in river downstream samples. While 15.9% (n = 28) were isolated from non-treated sludge, 6.8% (n = 12) were from pasteurized sludge (intermediate) and 1.7% (n = 3) in the amendment sludge samples.

The characterization of the phenotypes and genotypes of resistance of the bacterial collection is shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Phenotypes and genotypes of resistance of the 30 CR-E isolates according to their origin.

Table 2.

Phenotypes and genotypes of resistance of the 176 ESBL-Ec/Kp isolates according to their origin.

3.2. Antimicrobial Resistance Phenotypes

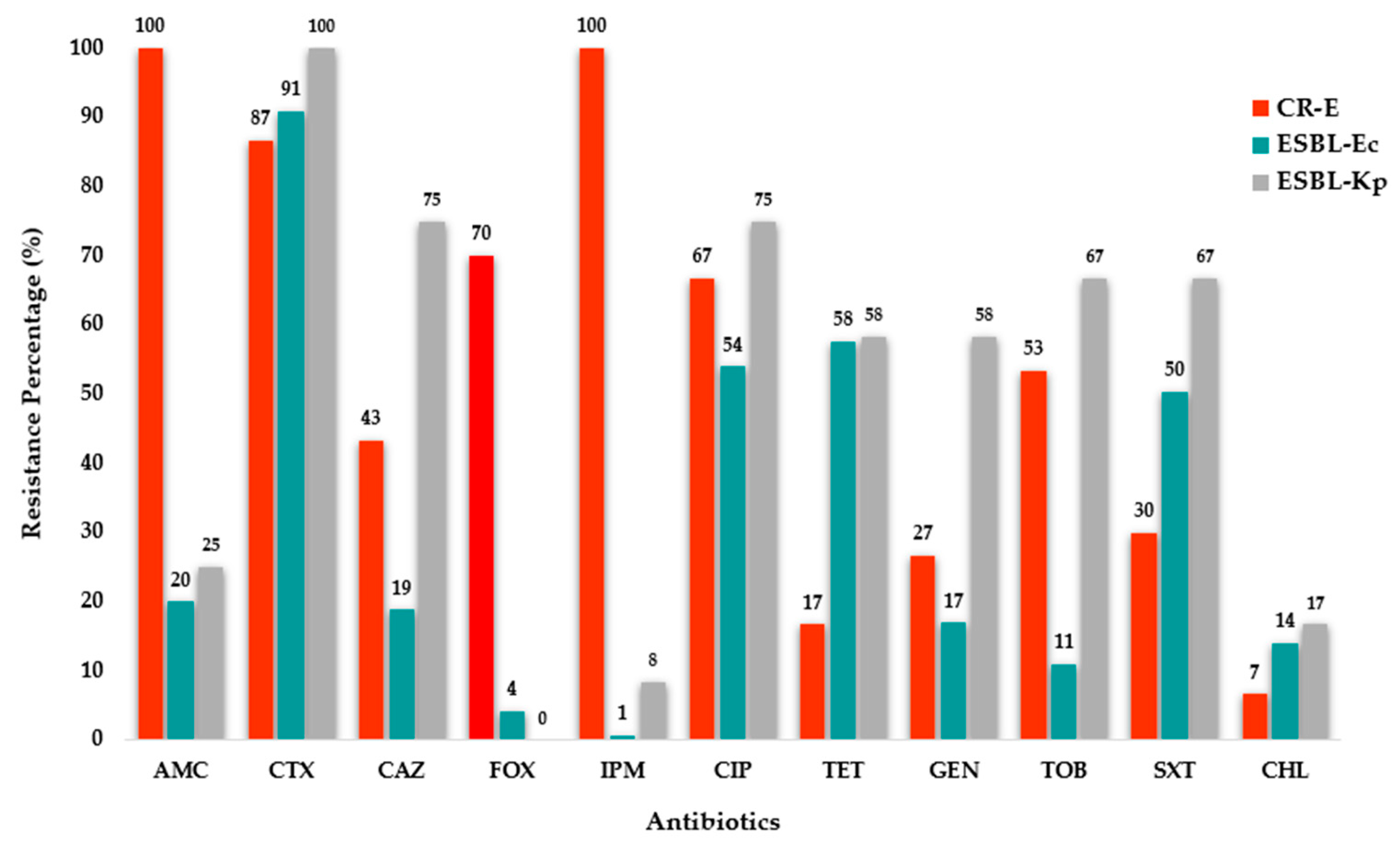

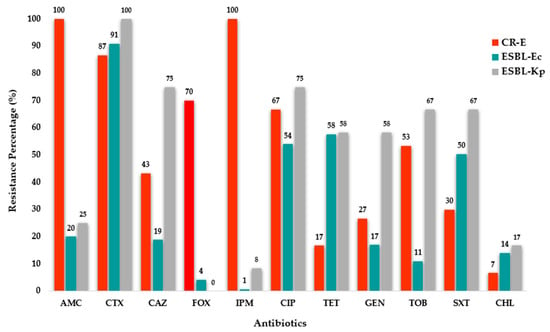

Antimicrobial susceptibility tests of the 30 CR-E isolates showed that 87% were resistant to cefotaxime, 70% to cefoxitin and 67% to ciprofloxacin. Meanwhile 53% of the CR-E isolates were resistant to tobramycin, 43% to ceftazidime, 30% to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, 27% of them were resistant to gentamicin and 17% to tetracycline. In addition, 7% of the isolates were resistant to chloramphenicol (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Antimicrobial resistance percentages among the 30 Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales, 164 ESBL-producing E. coli and 12 ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates. Antibiotics: AMC—amoxicillin-clavulanate, CTX—cefotaxime; CAZ—ceftazidime; FOX—cefoxitin; IPM—imipenem; CIP—ciprofloxacin; TET—tetracycline; GEN—gentamicin; TOB—tobramycin; SXT—trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and CHL—chloramphenicol.

Meanwhile, the antimicrobial susceptibility test of the 164 ESBL-E. coli isolates showed that 91% were resistant to cefotaxime, 20% to amoxicillin-clavulanate, 19% to ceftazidime and 4% to cefoxitin. Additionally, 58% of them were resistant to tetracycline, 54% to ciprofloxacin and 50% to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Resistance rates for the remaining antibiotics were ≤17% (Figure 2).

Regarding the 12 ESBL-K. pneumoniae isolates, the antimicrobial susceptibility test showed that 100% were resistant to cefotaxime, 75% to both ceftazidime and ciprofloxacin, and 25% to amoxicillin-clavulanate. Out of the total, 67% were resistant both to tobramycin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; meanwhile, 58% were resistant to tetracycline and gentamicin. Resistance rates for the remaining antibiotics were ≤18% (Figure 2).

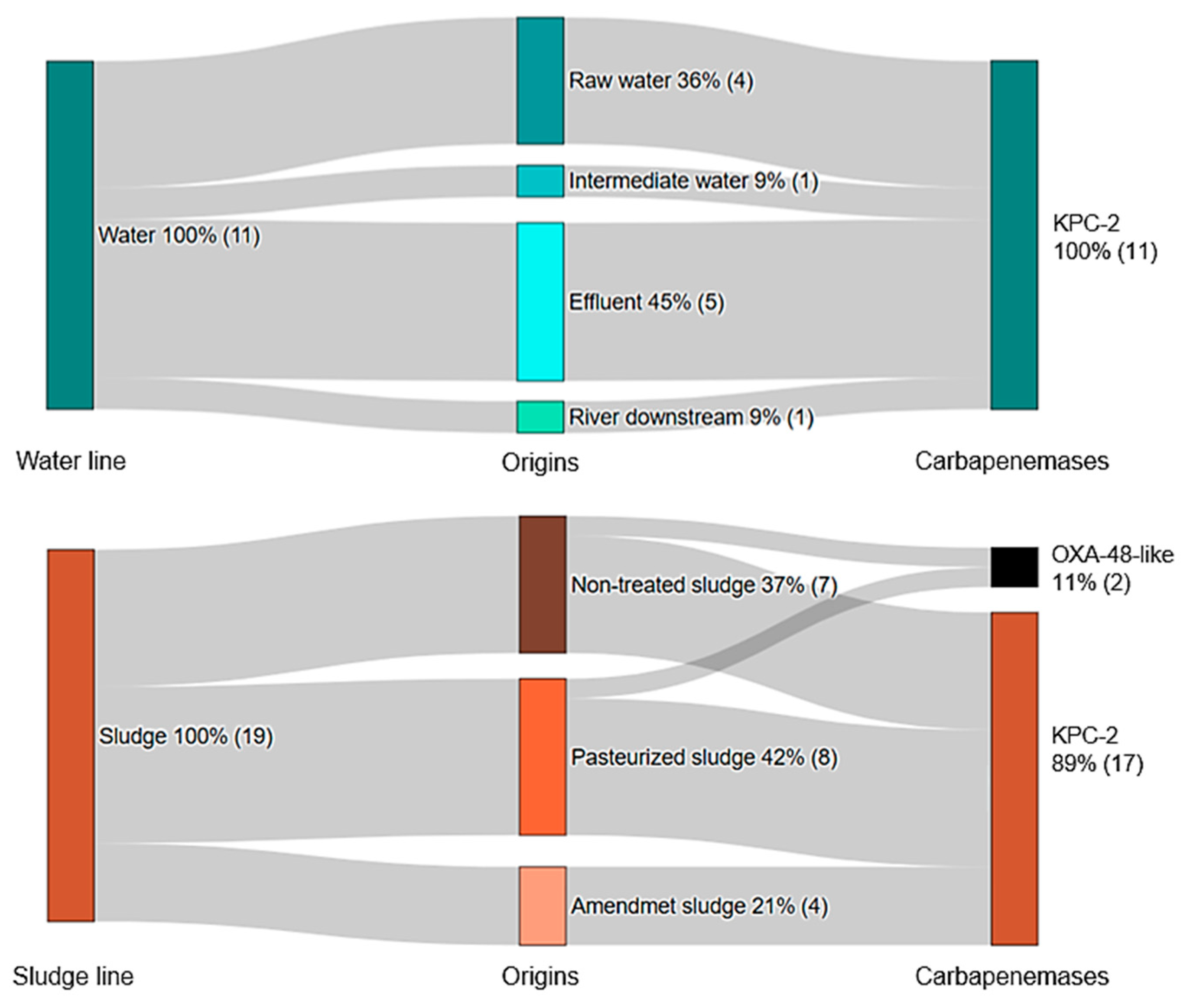

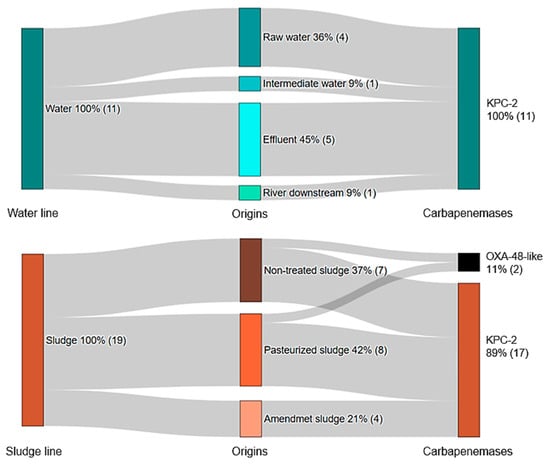

3.3. Carbapenemase Genes Detection Among the 30 CR-E Isolates

The carbapenemase genes detected by origins among the 30 CR-E isolates are shown in Figure 3 and Table 1, respectively. For more detailed information see Table S2.

Figure 3.

Percentage distribution of carbapenemase genes detected among the 30 CR-E according to the sample origin. The number of isolates is indicated in parentheses.

Of the total CR-E isolates, 93% (n = 28) were found to carry the blaKPC-2 gene, which was the most frequently detected carbapenemase gene, followed by blaOXA-48-like detected in two isolates (one K. pneumoniae and one E. coli) recovered from non-treated sludge and pasteurized sludge samples. Both blaOXA-48-like positive strains also co-harbored blaCTX-M-15 (Table 1). Nevertheless, no ESBL genes were detected in any of the strains carrying blaKPC-2.

Five CR-E isolates carrying blaKPC-2 were detected in effluent samples, representing four species (number of isolates): C. braakii (1), C. freundii (1), E. asburiae (1) and E. kobei (1). One CR-C. freundii isolate carrying the blaKPC-2 gene was found in downstream river samples (Figure 3 and Table 1). Regarding sludge stabilization (sludge line), IPMR C. freundii (1), C. farmeri (1) and E. kobei (2), carrying blaKPC-2 were recovered from amendment sludge samples, while two IPMR R. ornithinolytica isolates carrying blaKPC-2 variant were detected in non-treated and pasteurized sludge samples (Table 1). Genes encoding the metallo β-lactamases VIM and NDM were not detected in any of the CR-E isolates.

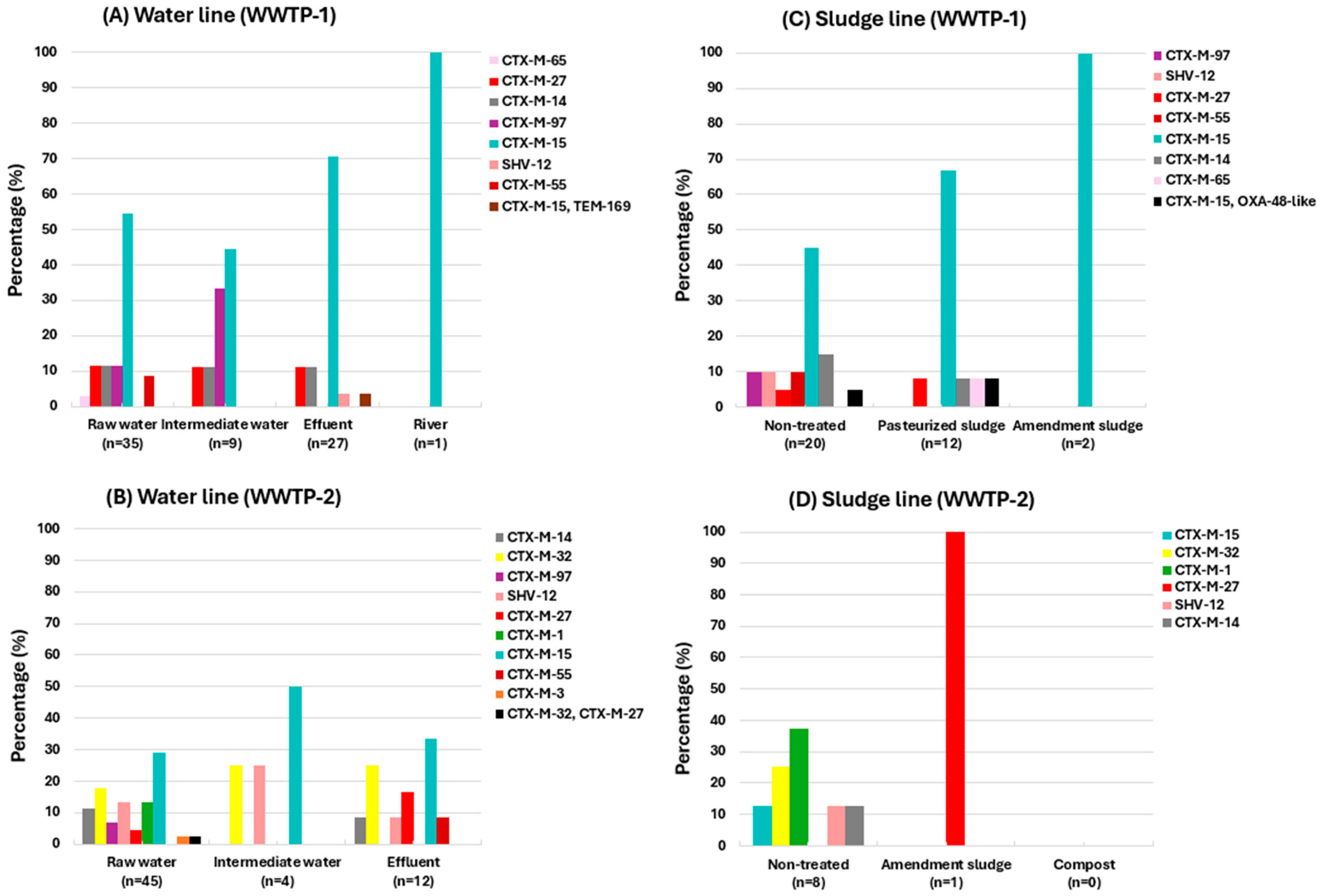

3.4. ESBL Genes Detection Among the 176 ESBL-Producing E. coli/K. pneumoniae Isolates

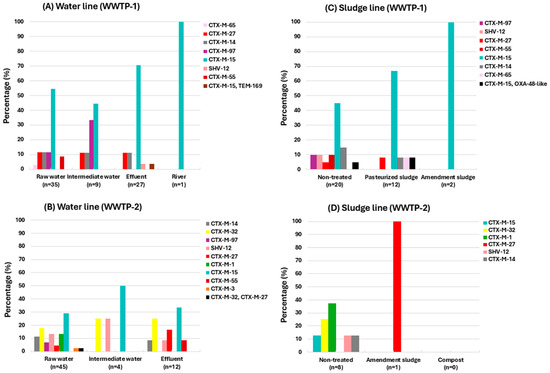

The percentages of ESBL genes detected by origins and the molecular characterization of the 176 ESBL-Ec/Kp isolates are shown in Figure 4 and Table 2, respectively. For more detailed information see Table S3.

Figure 4.

Percentage of ESBL variants detected among ESBL-Ec/Kp isolates according to the sample origin at each WWTP. (A) water line in WWTP-1; (B) water line in WWTP-2; (C) sludge line in WWTP-1; (D) sludge line in WWTP-2.

As shown in Figure 4, there is a greater diversity of ESBL genes in the influent of WWTP-2 (Figure 4B) compared to WWTP-1 (Figure 4A), which may be due to the fact that, as mentioned earlier, WWTP-2 also receives water from rural areas, including slaughterhouses.

The following ESBL gene variants were identified: blaCTX-M group 1 (variants 1/3/15/32/55), blaCTX-M group 9 (variants 14/27/65/97), blaSHV-12 and blaTEM-169. Among these isolates, the most prevalent was blaCTX-M-15, detected in 46.5% (n = 82) of the ESBL-Ec/Kp isolates, followed by blaCTX-M-14 (10.8%; n = 19), blaCTX-M-27 (8.5%; n = 15), blaCTX-M-32 (7.9%; n = 14) and blaSHV-12 (6.8%; n = 12).

Other β-lactamase genes, but not conferring an ESBL-phenotype, were also identified (blaTEM-1/35 and blaSHV-1/11/27/28, see Table 2).

Of the total ESBL-Ec/Kp isolates, 45.5% (n = 80) were recovered from raw water samples carrying blaCTX-M (variants 1/3/14/15/27/32/55/65/97) and blaSHV-12 (Figure 4A,B).

Otherwise, 22.2% (n = 39) were recovered from effluent samples carrying blaCTX-M (variants 14/15/27/32/55), blaSHV-12 and blaTEM-169. Among them, one E. coli was detected co-harboring blaCTX-M-15 and blaTEM-169 in WWTP1. Furthermore, one E. coli isolate carrying blaCTX-M-15 was recovered from downstream river samples (Figure 4A).

Regarding the sludge samples, 15.9% (n = 28) of the ESBL-Ec/Kp isolates were recovered from non-treated sludge samples, carrying blaCTX-M (variants 1/14/15/27/32/55/97) and blaSHV-12. Among these isolates, an E. coli co-harboring blaCTX-M-15 and blaOXA-244, as well as a K. pneumoniae co-harboring blaOXA-48 and blaCTX-M-15, were recovered from non-treated and pasteurized sludge samples, respectively.

In the amendment sludge samples, 1.7% (n = 3) of the isolates were detected carrying blaCTX-M-15/27. Non ESBL-Ec/Kp strains were recovered from compost samples (Figure 4C,D).

The frequency of detection of all ESBL and carbapenemase genes identified across the different stages of wastewater treatment and sludge stabilization is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

ESBL and carbapenemase variants detected by origin. The size/color of the dots represent the detection frequency and the type of ESBL or carbapenemase.

4. Discussion

The presence of ARB in aquatic environments facilitates their spread into the environment and represents a public health concern [26]. The development of techniques to monitor AMR in wastewater has progressed significantly in recent years. An increasing number of publications are using advanced molecular techniques, such as metagenomics, which allow one to analyze the complexity of microbial communities, the dynamics of resistance, and the transfer of mobile genetic elements associated with the spread of ARGs [27].

However, despite advances in molecular techniques, the surveillance of ESBL-producing- or carbapenem-resistant strains still relies on culture-based methodologies. These methods are essential to accurately identify viable strains, conduct susceptibility tests, and perform subsequent whole-genome sequencing (WGS) analyses for comparison.

There is abundant research confirming the presence of carbapenemase and ESBL genes in wastewater from various sources, particularly in hospital effluents and WWTPs, but also in domestic and industrial wastewaters, as well as receiving rivers. This is highlighted in a recently published review [28]. However, culture-based studies conducted in Spain and included in this aforementioned review are scarce [29,30]. Following the review and to the best of our knowledge, only a few studies have been published [31,32,33] including our own [4].

These gaps highlight the need for further research and justify the present work, particularly in our region, where data on the presence and dissemination of ARB in WWTPs remain limited. We demonstrate the presence of CR-E and ESBL-Ec/Kp, as well as the types of β-lactamases involved, in two WWTPs located in northern Spain. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first analysis of ARGs conducted at this specific site, complementing our previous research [4].

CR-E were detected at the influent and intermediate stages of treatment in both the water and sludge lines of the two WWTPs analyzed, likely reflecting their circulation within local human and/or animal populations and the activities that discharge into the WWTPs. However, what is most concerning is their persistence at final discharge points of both lines (effluent and amendment sludge), as well as in surface waters (river downstream).

It is important to underline that our study was not designed to assess reduction rates; rather, the findings highlight environmental dissemination and contamination, indicate the presence of a microbiological hazard with potential human health implications, and suggest that conventional biological treatment is insufficient to eliminate microbial loads. qPCR would be required to determine the reduction efficiency. In addition, clonality was not examined; therefore, WGS and Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST) would help to determine clonal relationships and potential links with high-risk clinical clones.

The presence of CR-E in wastewater has been documented in several studies [33,34,35,36,37]. However, research focusing on their presence and persistence in sludge samples remains scarce [33,38,39,40]. The CR-E isolates showed high diversity in both genera and species, with Citrobacter being the most frequent genus, accounting for 36% (11/30) of the isolates. Klebsiella (5/30) and Escherichia (2/30) represented 16.6% and 6.6%, respectively.

The most prevalent type of carbapenemase identified was KPC-2 (28/30); these findings are consistent with those from two recent reports in another regions of Spain [32,33]. Unlike those authors, we did not detect blaVIM in any of the isolates; notably, they did not detect blaNDM either. This discrepancy may be attributed to the epidemiological characteristics of the region where the WWTPs are located, which has a low prevalence of CR-E [41]. Additionally, it is known that blaVIM is more frequently associated with Pseudomonas species [42].

Interestingly, despite the observed global increase in reports of blaOXA-48-like genes [43], particularly in Europe, and described as predominant in Spain [41,44] and even persistent throughout the wastewater treatment processes [28], we only detected two isolates. This may be related to the lower prevalence of blaOXA-48 previously reported in the La Rioja region [41].

In addition, these two isolates co-harbored blaCTX-M-15. These findings are consistent with previous reports in clinical and environmental settings from several countries [32,43,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. Co-carriage of blaOXA-48-like and blaCTX-M-15 in E. coli and K. pneumoniae has been reported either co-located on a single plasmid or located on different plasmids within the same isolate [43,49,50]; or with blaCTX-M-15 integrated into the chromosome and blaOXA-48 remaining plasmid-borne, favoring clonal persistence [51,52]. However, we did not investigate plasmid or chromosomal co-location, which would require WGS analysis.

Future studies including strains recovered from hospital settings would be of great interest, as they would allow for the evaluation and comparison of ARB dissemination between hospital and WWTPs. The inclusion of hospital-origin strains would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between resistance hotspots in healthcare settings and their potential spread into the environment through wastewater [53].

Similarly to CR-E strains, ESBL-producing isolates have been detected at all stages throughout the water and sludge lines of the WWTPs, including the final discharge points. This persistence poses a potential microbiological hazard for environmental dissemination and human exposure. It should be noted that our work included only ESBL-E. coli and K. pneumoniae, with E. coli being the predominant species, accounting for more than 90% (165/176) of the ESBL-Ec/Kp isolates.

A high diversity of ESBL gene variants was detected among our isolates, with blaCTX-M (variants 14/15/32) being the most prevalent. Among these, blaCTX-M-15 was the most abundant. In both WWTPs, a decrease in ESBL gene diversity was observed throughout the treatment process, with higher diversity at the initial stages and lower diversity at the final stages of treatment. These results are consistent with those reported in previous studies [54,55].

A difference was observed between the two WWTPs regarding the types of ESBL detected. This finding could be related to the specific characteristics of the influent wastewater received by each facility. WWTP-1 is located in an urban area, where the wastewater predominantly originates from domestic sources. The possible human origin of the isolated strains could explain the higher prevalence of the blaCTX-M-15 gene [40].

In contrast, WWTP-2 is located in a rural municipality and receives wastewater from a wider range of sources, including agricultural activities and livestock farming. Notably, WWTP-2 also treats effluents from slaughterhouses, which could contribute to the presence of different ESBL types. This may explain the higher ESBL gene diversity observed, as well as the increased prevalence of blaCTX-M-1 and blaCTX-M-32 genes, although this remains a hypothesis since quantitative analysis of influent composition was not performed [56].

These differences in wastewater origin may influence the diversity of ESBL-Ec/Kp strains, as distinct environmental and anthropogenic pressures can drive the selection and dissemination of specific ESBL variants.

We recovered an E. coli isolate co-harboring blaCTX-M-15 and blaTEM-169 in the effluent from WWTP-1. Although TEM-169 is a less frequently reported ESBL, the same co-occurrence has been described in Salmonella spp. [57] and E. cloacae [58] from Iran, and in E. coli from Ghana [59] and Ethiopia [60], all of clinical origin, as well as in E. coli from wastewater in Pakistan [61]. The detection of this co-occurrence in the effluent indicates that WWTPs may release into the environment bacterial reservoirs carrying multiple ESBL determinants.

Furthermore, occupational exposure of workers to ARB in WWTPs, as well as exposure of residents living near these facilities, may constitute a microbiological hazard for colonization or infection with resistant pathogens. This underscores the importance of implementing stringent safety protocols and effective treatment strategies to mitigate the spread of AMR within and beyond WWTPs [62].

5. Conclusions

We confirmed the presence of CR-E and ESBL-Ec/Kp isolates throughout the wastewater treatment process. Their persistence at final discharge points (effluents and organic amendments) and in surface waters highlights the limitations of conventional treatment in fully eliminating ARB, emphasizing the need to optimize current wastewater processes. This also indicates a microbiological hazard for environmental dissemination and human exposure, particularly when inadequately treated sludge is applied as an agricultural amendment, although further risk-assessment studies are required.

Notably, we detected co-harboring OXA-48-like/CTX-M-15 isolates in sludge (a combination that, although previously reported, has not been described in sludge samples to our knowledge), as well as isolates carrying two distinct ESBL genes in effluent, indicating the release of clinically relevant ARB into the environment.

The use of culture-based methods complemented by molecular techniques is essential for assessing bacterial viability, resistance profiles, and performing genetic characterization. This approach is relevant to support surveillance efforts and highlights the need for improvements in wastewater treatment technologies. Region-specific investigations such as the present work provide a necessary basis for future research and for understanding local AMR dynamics.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152111703/s1, Table S1: PCR conditions for detection of carbapenem-resistance and ESBL genes; Table S2: Characteristics of the 30 CR-E isolates recovered in this study, Table S3: Characteristics of the 176 ESBL-Ec/Kp isolates recovered in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.P.-H., R.F.-F., C.L., C.T. and M.Z.; Methodology, M.S.P.-H., R.F.-F., C.L., C.T. and M.Z.; Validation, M.S.P.-H., R.F.-F., C.L., C.T. and M.Z.; Formal Analysis, M.S.P.-H., R.F.-F., C.L., C.T. and M.Z.; Investigation, M.S.P.-H., L.R.-T., I.M.-C., T.Á.-G. and D.J.G.-M.; Resources, C.T. and M.Z.; Data Curation, M.S.P.-H., C.T. and M.Z.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.S.P.-H., C.T. and M.Z.; Writing—Review & Editing, M.S.P.-H., L.R.-T., R.F.-F., I.M.-C., T.Á.-G., D.J.G.-M., C.L., C.T. and M.Z.; Visualization, M.S.P.-H., R.F.-F., C.L., C.T. and M.Z.; Supervision, C.T. and M.Z.; Project Administration, C.T. and M.Z.; Funding Acquisition, C.T. and M.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by project ADER-UR: (2021-I-IDD-00059). Mario Sergio Pino-Hurtado has a Predoctoral Contract FPI from the University of La Rioja (FPI-UR) and Tamara Álvarez-Gómez has a research contract associated with project PID2022-139591OB-I00.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The sampling points were established in collaboration with the responsible staff from the “Consorcio de Aguas y Residuos de La Rioja”, considering the objectives pursued. We extend a special thanks to Pilar Madorrán, Natalia Ruiz, Gabriela Seco, David Moreno and Juan José Gil for the sampling organization.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| ARB | Antimicrobial resistant bacteria |

| ARGs | Antimicrobial resistance genes |

| CR-E | Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales |

| ECDC | European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control |

| ESBL | Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases |

| ESBL-Ec/Kp | Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases-producing E. coli/K. pneumoniae |

| IPMR | Imipenem-resistant |

| MLST | Multi-Locus Sequence Typing |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| WBS | Wastewater-based epidemiology |

| WGS | whole-genome sequencing |

| WWTPs | Wastewater Treatment Plants |

References

- Akram, F.; Imtiaz, M.; ul Haq, I. Emergent crisis of antibiotic resistance: A silent pandemic threat to 21st century. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 174, 105923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Barkhouse, A.; Hackenberger, D.; Wright, G.D. Antibiotic resistance: A key microbial survival mechanism that threatens public health. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martak, D.; Henriot, C.P.; Hocquet, D. Environment, animals, and food as reservoirs of antibiotic-resistant bacteria for humans: One health or more? Infect. Dis. Now 2024, 54, 104895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-Hurtado, M.S.; Fernández-Fernández, R.; Campaña-Burguet, A.; González-Azcona, C.; Lozano, C.; Zarazaga, M.; Torres, C. A Surveillance Study of Culturable and Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacteria in Two Urban WWTPs in Northern Spain. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava, A.R.; Daneshian, L.; Sarma, H. Antibiotic resistant genes in the environment-exploring surveillance methods and sustainable remediation strategies of antibiotics and ARGs. Environ. Res. 2022, 215, 114212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lu, S.; Guo, W.; Xi, B.; Wang, W. Antibiotics in the aquatic environments: A review of lakes, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 627, 1195–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, R.P.; Yousef, A.F.; Alsafar, H.; Hasan, S.W. Surveillance, distribution, and treatment methods of antimicrobial resistance in water: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 890, 164360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambaza, S.S.; Naicker, N. Contribution of wastewater to antimicrobial resistance: A review article. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 34, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piedra-Carrasco, N.; Fàbrega, A.; Calero-Cáceres, W.; Cornejo-Sánchez, T.; Brown-Jaque, M.; Mir-Cros, A.; Muniesa, M.; González-López, J.J. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae recovered from a Spanish river ecosystem. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, R.J. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in different environments (humans, food, animal farms and sewage). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 58, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024: Bacterial Pathogens of Public Health Importance to Guide Research, Development and Strategies to Prevent and Control Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240093461 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Rapid Risk Assessment—Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales—Third Update. ECDC 2025. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/carbapenem-resistant-enterobacterales-rapid-risk-assessment-third-update (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Manaia, C.M. Framework for establishing regulatory guidelines to control antibiotic resistance in treated effluents. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 754–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzeniewska, E.; Harnisz, M. Culture-Dependent and Culture-Independent Methods in Evaluation of Emission of Enterobacteriaceae from Sewage to the Air and Surface Water. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2012, 223, 4039–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters, Version 14.0. 2024. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 34th ed.; CLSI M100-Ed34; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA; Available online: https://www.clsi.org/shop/standards/m100/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Drieux, L.; Brossier, F.; Sougakoff, W.; Jarlier, V. Phenotypic detection of extended-spectrum β-lactamase production in Enterobacteriaceae: Review and bench guide. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2008, 14, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, C.A. Molecular Epidemiology of Escherichia coli from Wildlife: Antimicrobial Resistance, Virulence and Genetic Diversity. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de La Rioja, Logroño, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Poirel, L.; Walsh, T.R.; Cuvillier, V.; Nordmann, P. Multiplex PCR for detection of acquired carbapenemase genes. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2011, 70, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagani, L.; Dell’Amico, E.; Migliavacca, R.; D’Andrea, M.M.; Giacobone, E.; Amicosante, G.; Romero, E.; Rossolini, G.M. Multiple CTX-M-Type Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases in Nosocomial Isolates of Enterobacteriaceae from a Hospital in Northern Italy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 4264–4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coque, T.M.; Oliver, A.; Pérez-Díaz, J.C.; Baquero, F.; Cantón, R. Genes Encoding TEM-4, SHV-2, and CTX-M-10 Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases Are Carried by Multiple Klebsiella pneumoniae Clones in a Single Hospital (Madrid, 1989 to 2000). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitout, J.D.D.; Thomson, K.S.; Hanson, N.D.; Ehrhardt, A.F.; Moland, E.S.; Sanders, C.C. β-Lactamases Responsible for Resistance to Expanded-Spectrum Cephalosporins in Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, and Proteus mirabilis Isolates Recovered in South Africa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998, 42, 1350–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Belaaouaj, A.; Lapoumeroulie, C.; Caniça, M.M.; Vedel, G.; Névot, P.; Krishnamoorthy, R.; Paul, G. Nucleotide sequences of the genes coding for the TEM-like β-lactamases IRT-1 and IRT-2 (formerly called TRI-1 and TRI-2). FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1994, 120, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). BLAST+ Version 2.17.0. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. Available online: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Naas, T.; Oueslati, S.; Bonnin, R.A.; Dabos, M.L.; Zavala, A.; Dortet, L.; Retailleau, P.; Iorga, B.I. Beta-lactamase database (BLDB)—Structure and function. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2017, 32, 917–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marutescu, L.G.; Popa, M.; Gheorghe-Barbu, I.; Barbu, I.C.; Rodríguez-Molina, D.; Berglund, F.; Blaak, H.; Flach, C.-F.; Kemper, M.A.; Spießberger, B.; et al. Wastewater treatment plants, an “escape gate” for ESCAPE pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1193907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, E.; Maile-Moskowitz, A.; Angeles, L.F.; Flach, C.F.; Aga, D.S.; Nambi, I.; Larsson, D.G.J.; Bürgmann, H.; Zhang, T.; Vikesland, P.J.; et al. Metagenomic Profiling of Internationally Sourced Sewage Influents and Effluents Yields Insight into Selecting Targets for Antibiotic Resistance Monitoring. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 16547–16559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waśko, I.; Kozińska, A.; Kotlarska, E.; Baraniak, A. Clinically Relevant β-Lactam Resistance Genes in Wastewater Treatment Plants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojer-Usoz, E.; González, D.; García-Jalón, I.; Vitas, A.I. High dissemination of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in effluents from wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 2014, 56, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, L.; González, D.; Leiva, J.; Vitas, A.I. Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria Isolated from Different Aquatic Environments in the North of Spain and South of France. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Truchado, P.; Cordero-García, R.; Gil, M.I.; Soler, M.A.; Rancaño, A.; García, F.; Álvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Allende, A. Surveillance on ESBL-Escherichia coli and Indicator ARG in Wastewater and Reclaimed Water of Four Regions of Spain: Impact of Different Disinfection Treatments. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monge-Olivares, L.; Peñalva, G.; Pulido, M.R.; Garrudo, L.; Doval, M.A.; Ballesta, S.; Merchante, N.; Rasero Del Real, P.; Cuberos, L.; Carpes, G.; et al. Quantitative Study of ESBL and Carbapenemase Producers in Wastewater Treatment Plants in Seville, Spain: A Culture-Based Detection Analysis of Raw and Treated Water. Water Res. 2025, 281, 123706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasser-Ali, M.; Aja-Macaya, P.; Conde-Pérez, K.; Trigo-Tasende, N.; Rumbo-Feal, S.; Fernández-González, A.; Bou, G.; Poza, M.; Vallejo, J.A. Emergence of Carbapenemase Genes in Gram-Negative Bacteria Isolated from the Wastewater Treatment Plant in A Coruña, Spain. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekizuka, T.; Yatsu, K.; Inamine, Y.; Segawa, T.; Nishio, M.; Kishi, N.; Kuroda, M. Complete Genome Sequence of a blaKPC-Positive Klebsiella pneumoniae Strain Isolated from the Effluent of an Urban Sewage Treatment Plant in Japan. mSphere 2018, 3, e00314-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, A.; Paakkanen, J.; Österblad, M.; Kirveskari, J.; Hendriksen, R.S.; Heikinheimo, A. Wastewater Surveillance Detected Carbapenemase Enzymes in Clinically Relevant Gram-Negative Bacteria in Helsinki, Finland; 2011–2012. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 887888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Almotiri, A.; AlZeyadi, Z.A. Antimicrobial Resistance and β-Lactamase Production in Clinically Significant Gram-Negative Bacteria Isolated from Hospital and Municipal Wastewater. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, S.; Sousa, M.; Tacão, M.; Baraúna, R.A.; Silva, A.; Ramos, R.; Alves, A.; Manaia, C.M.; Henriques, I. Carbapenem-resistant bacteria over a wastewater treatment process: Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in untreated wastewater and intrinsically-resistant bacteria in final effluent. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 782, 146892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, E.A.; Aristizábal-Hoyos, A.M.; Morales-Zapata, S.; Arias, L.; Jiménez, J.N. High frequency of gram-negative bacilli harboring blaKPC-2 in the different stages of wastewater treatment plant: A successful mechanism of resistance to carbapenems outside the hospital settings. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 271, 111046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Berglund, B.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Z.; Gu, C.; Zhao, L.; Meng, C.; Li, X. Emergence of blaNDM-1, blaNDM-5, blaKPC and blaIMP-4 carrying plasmids in Raoultella spp. in the environment. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 306, 119437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, C.; Weaver, L.; Cornelius, A.J.; McGill, E.; Dyet, K.; Pattis, I. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase, AmpC, and carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative wastewater isolates from Aotearoa New Zealand. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2024, 13, e00131-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañada-García, J.E.; Moure, Z.; Sola-Campoy, P.J.; Delgado-Valverde, M.; Cano, M.E.; Gijón, D.; González, M.; Gracia-Ahufinger, I.; Larrosa, N.; Mulet, X.; et al. CARB-ES-19 Multicenter Study of Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli from All Spanish Provinces Reveals Interregional Spread of High-Risk Clones Such as ST307/OXA-48 and ST512/KPC-3. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 918362, Erratum in Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1331657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Barrio-Tofiño, E.; López-Causapé, C.; Oliver, A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa epidemic high-risk clones and their association with horizontally-acquired β-lactamases: 2020 update. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 56, 106196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potron, A.; Nordmann, P.; Rondinaud, E.; Jaureguy, F.; Poirel, L. A mosaic transposon encoding OXA-48 and CTX-M-15: Towards pan-resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013, 68, 476–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahdouh, E.; Gómez-Marcos, L.; Cañada-García, J.E.; de Arellano, E.R.; Sánchez-García, A.; Sánchez-Romero, I.; López-Urrutia, L.; de la Iglesia, P.; Gonzalez-Praetorius, A.; Sotelo, J.; et al. Characterizing carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli isolates from Spain: High genetic heterogeneity and wide geographical spread. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1390966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitout, J.D.D.; Peirano, G.; Kock, M.M.; Strydom, K.-A.; Matsumura, Y. The global ascendency of OXA-48-type carbapenemases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 33, e00102-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay, J.; Perreten, V.; Poirel, L.; Nordmann, P. Molecular analysis of OXA-48-producing Escherichia coli in Switzerland from 2019 to 2020. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2022, 41, 1355–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, S.E.; Holmes, A.; Peck, R.; Livermore, D.M.; Hope, W. OXA-48-like β-lactamases: Global epidemiology, treatment options, and development pipeline. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e00216-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, Y.; Nazareno, P.J.; Nakano, R.; Mondoy, M.; Nakano, A.; Bugayong, M.P.; Bilar, J.; Perez, M.; Medina, E.J.; Saito-Obata, M.; et al. Environmental presence and genetic characteristics of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae from hospital sewage and river water in the Philippines. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e01906-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard-Jones, A.R.; Sandaradura, I.; Robinson, R.; Orde, S.; Iredell, J.; Ginn, A.; van Hal, S.; Branley, J. Multidrug-resistant OXA-48/CTX-M-15 Klebsiella pneumoniae cluster in a COVID-19 intensive care unit: Salient lessons for infection prevention and control during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Hosp. Infect. 2022, 126, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzina, E.S.; Kislichkina, A.A.; Sizova, A.A.; Skryabin, Y.P.; Novikova, T.S.; Ershova, O.N.; Savin, I.A.; Khokhlova, O.E.; Bogun, A.G.; Fursova, N.K. High-molecular-weight plasmids carrying carbapenemase genes blaNDM-1, blaKPC-2, and blaOXA-48 coexisting in clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae strains of ST39. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, E.-J.; Gwon, B.; Liu, C.; Kim, D.; Won, D.; Park, S.G.; Choi, J.R.; Jeong, S.H. Beneficial chromosomal integration of the genes for CTX-M extended-spectrum β-lactamase in Klebsiella pneumoniae for stable propagation. mSystems 2020, 5, e00459-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawa, M.; Furuta, Y.; Mulenga, G.; Mubanga, M.; Mulenga, E.; Zorigt, T.; Kaile, C.; Simbotwe, M.; Paudel, A.; Hang’oMbe, B.; et al. Novel chromosomal insertions of ISEcp1-blaCTX-M-15 and diverse antimicrobial resistance genes in Zambian clinical isolates of Enterobacter cloacae and Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2021, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Lazaro-Perona, F.; Falgenhauer, L.; Valverde, A.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Dominguez, L.; Cantón, R.; Mingorance, J.; Chakraborty, T. Insights into a Novel blaKPC-Encoding IncP-6 Plasmid Reveal Carbapenem-Resistance Circulation in Several Enterobacteriaceae Species from Wastewater and a Hospital Source in Spain. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubeny, J.; Ciesielski, S.; Harnisz, M.; Korzeniewska, E.; Dulski, T.; Jałowiecki, Ł.; Płaza, G. Impact of Hospital Wastewater on the Occurrence and Diversity of Beta-Lactamase Genes During Wastewater Treatment with an Emphasis on Carbapenemase Genes: A Metagenomic Approach. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 738158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, E.A.; Pino, N.J.; Jiménez, J.N. Climatological and Epidemiological Conditions Are Important Factors Related to the Abundance of blaKPC and Other Antibiotic Resistance Genes (ARGs) in Wastewater Treatment Plants and Their Effluents, in an Endemic Country. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 686472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandujano-Hernández, A.; Martínez-Vázquez, A.V.; Paz-González, A.D.; Herrera-Mayorga, V.; Sánchez-Sánchez, M.; Lara-Ramírez, E.E.; Vázquez, K.; de Jesús de Luna-Santillana, E.; Bocanegra-García, V.; Rivera, G. The Global Rise of ESBL-Producing Escherichia coli in the Livestock Sector: A Five-Year Overview. Animals 2024, 14, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjbar, R.; Giammanco, G.M.; Aleo, A.; Plano, M.R.A.; Naghoni, A.; Owlia, P.; Mammina, C. Characterization of the First Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase–Producing Nonty-phoidal Salmonella Strains Isolated in Tehran, Iran. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2010, 7, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peymani, A.; Farivar, T.N.; Sanikhani, R.; Javadi, A.; Najafipour, R. Emergence of TEM, SHV, and CTX-M-Extended Spectrum β-Lactamases and Class 1 Integron Among Enterobacter cloacae Isolates Collected from Hospitals of Tehran and Qazvin, Iran. Microbiol. Drug Resist. 2014, 20, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare Yeboah, E.E.; Agyepong, N.; Mbanga, J.; Amoako, D.G.; Abia, A.L.K.; Ismail, A.; Owusu-Ofori, A.; Essack, S.Y. Genomic characterization of multi drug resistant ESBL-producing Escherichia coli isolates from patients and patient environments in a teaching hospital in Ghana. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolde, D.; Eguale, T.; Alemayehu, H.; Medhin, G.; Haile, A.F.; Pirs, M.; Strašek Smrdel, K.; Avberšek, J.; Kušar, D.; Cerar Kišek, T.; et al. Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Characterization of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli Isolated from Stools of Primary Healthcare Patients in Ethiopia. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, F.; Hu, X.; Saxena, A.; Mou, K.; Shen, H.; Ali, H.; Ghauri, M.A.; Sarwar, Y.; Ali, A.; Li, G. Analyzing Antibiotic Resistance in Bacteria from Wastewater in Pakistan Using Whole-Genome Sequencing. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Molina, D.; Berglund, F.; Blaak, H.; Flach, C.-F.; Kemper, M.; Marutescu, L.; Gradisteanu, G.P.; Popa, M.; Spießberger, B.; Weinmann, T.; et al. Carriage of ESBL-producing Enterobacterales in wastewater treatment plant workers and surrounding residents—The AWARE Study. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).