Crunchiness of Osmotically Dehydrated Freeze-Dried Strawberries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Osmotically Dehydrated and Freeze-Dried Strawberries

2.2. Dry Matter, Water Activity, and Density

2.3. Acoustic and Mechanical Properties

2.4. Determination of Bioactive Substances Content

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Dry Matter Content, Water Activity, and Density Results

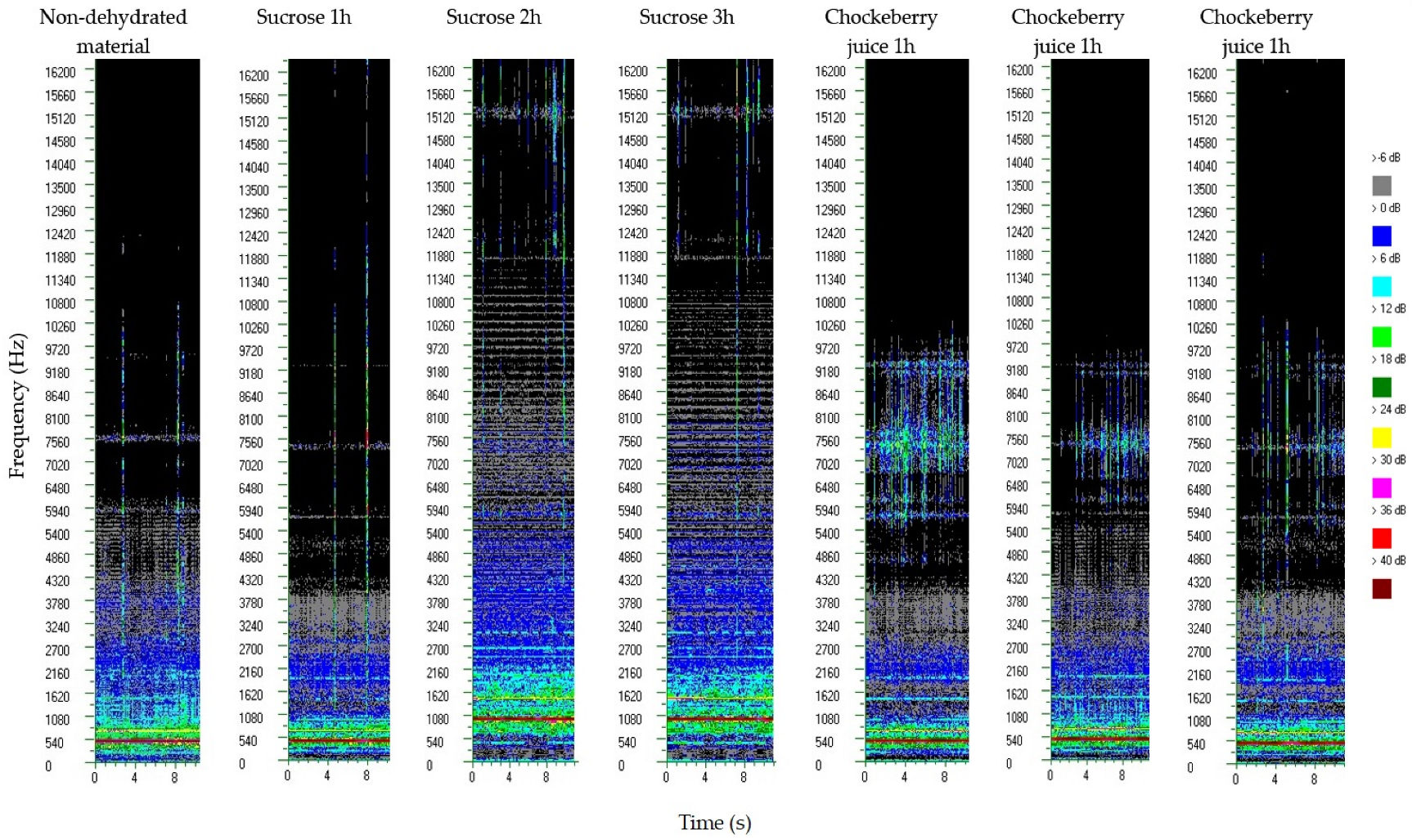

3.2. Crunchiness of Freeze-Dried Strawberries

3.3. Content of Bioactive Substances

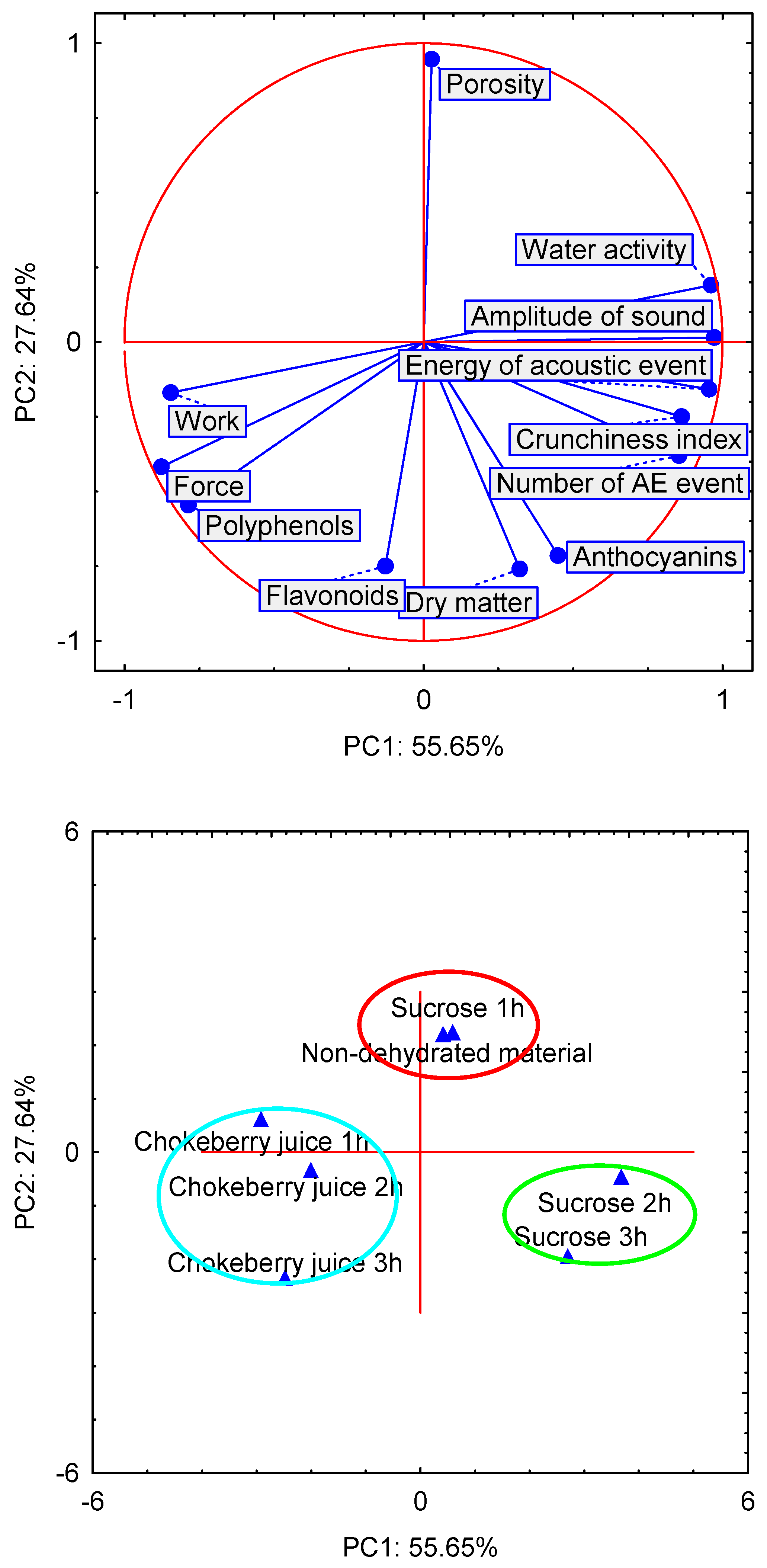

3.4. The Relationship Between Texture Properties and Content of Bioactive Compounds of Freeze-Dried Strawberries

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pellegrino, R.; Luckett, C.R. Aversive textures and their role in food rejection. J. Texture Stud. 2020, 51, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surmacka-Szcześniak, A. Texture is a sensory property. Food Qual. Prefer. 2002, 13, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Njehia, N.S.; Katsuno, N.; Nishizu, T. An acoustic study on the texture of cellular brittle foods. Rev. Agric. Sci. 2020, 8, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillion, L.; Kilcast, D. Consumer perception of crispness and crunchiness in fruits and vegetables. Food Qual. Prefer. 2002, 13, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyten, A.; Pluter, J.J.; Vliet, T. Crispy/crunchy crusts of cellular solid foods: A literature review with discussion. J. Texture Stud. 2004, 35, 445–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, M.A.; Younce, F.; Ross, C.; Swansons, B. Standard scales for crispness, crackliness and crunchiness in dry and wet foods: Relationship with acoustical determinations. J. Texture Stud. 2008, 39, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabella, P.; Farina, A.; Leporati, A. Methodology of Chewing’s sound acquisition by different detectors for dry food in terms of crispness and crunchiness. Appl. Acoust. 2024, 218, 109889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, Z.M.; Bourne, M.C. A psychoacoustic theory of crispness. J. Food Sci. 1976, 41, 1158–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duizer, L. A review of acoustic research for studying the sensory perception of crisp, crunchy and crackly textures. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2001, 12, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeleaw, M.; Schleining, G. A review: Crispness in dry foods and quality measurements based on acoustic–mechanical destructive techniques. J. Food Eng. 2011, 105, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreani, P.; de Moraes, J.O.; Murta, B.H.P.; Link, J.V.; Tribuzi, G.; Laurindo, J.B.; Paul, S.; Carciofi, B.A.M. Spectrum crispness sensory scale correlation with instrumental acoustic high-sampling rate and mechanical analyses. Food Res. Int. 2020, 129, 108886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohyama, K. Food texture–sensory evaluation and instrumental measurement. In Textural Characteristics of World Foods, 1st ed.; Nishinari, K., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Marzec, A.; Kowalska, H.; Zadrożna, M. Analysis of instrumental and sensory texture attributes of microwave–convective dried apples. J. Texture Stud. 2010, 41, 417–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk, E.; Gondek, E.; Tryzno, E. Application of novel acoustic measurement techniques for texture analysis of co-extruded snacks. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 75, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Faceto, L.S.; Salvador, A.; Conti-Silva, A.C. Acoustic settings combination as a sensory crispness indicator of dry crispy food. J. Texture Stud. 2020, 51, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewicki, P.P.; Marzec, A.; Ranachowski, Z. Acoustic properties of foods. In Food Properties Handbook, 2nd ed.; Shafiur Rahman, M., Ed.; CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA; London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009; Chapter 24; pp. 811–841. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubczyk, E.; Kamińska-Dwórznicka, A.; Ostrowska-Ligęza, E. The effect of composition, pre-treatment on the mechanical and acoustic properties of apple gels and freeze-dried materials. Gels 2022, 8, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zdunek, A.; Konopacka, D.; Jesionkowska, K. Crispness and crunchiness judgment of apples based on contact acoustic emission. J. Texture Stud. 2010, 41, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniwaki, M.; Kohyama, K. Mechanical and acoustic evaluation of potato chip crispness using a versatile texture analyzer. J. Food Eng. 2012, 112, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, H.; Xiang, K.; Li, D.; Liu, C.; Wang, H.; Pang, W.; Niu, l.; Yu, R.; Sun, X. Factors affecting chemical and textural properties of dried tuber, fruit and vegetable. J. Food Eng. 2024, 365, 111828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunachowicz, H.; Przygoda, B.; Nadolna, I.; Iwanow, K. Tabele Składu i Wartości Odżywczej Żywności; PZWL Wydawnictwo Lekarskie: Warszawa, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Diamanti, J.; Capocasa, F.; Denoyes, B.; Petit, A.; Chartier, P.; Faedi, W.; Maltoni, M.L.; Battino, M.; Mezzetti, B. Standardized method for evaluation of strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) germplasm collections as a genetic resource for fruit nutritional compounds. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2012, 28, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani, R.; Razavi, F.; Mortazavi, S.N.; Gohari, G.; Juárez-Maldonado, A. Evaluation of Proline-Coated Chitosan Nanoparticles on Decay Control and Quality Preservation of Strawberry Fruit (cv. Camarosa) during Cold Storage. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Orbea, G.; García-Villalba, R.; Bernal, M.; Hernández, A.; Tomás-Barberán, F.; Sánchez-Siles, L. Stability of phenolic compounds in apple and strawberry: Effect of different processing techniques in industrial set up. Food Chem. 2023, 401, 134099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, H.E.; Xiaobo, Z.; Jiyong, S.; Mahunu, G.K.; Zhai, X.; Mariod, A.A. Quality and postharvest-shelf life of cold-stored strawberry fruit as affected by gum arabic (Acacia senegal) edible coating. J. Food Biochem. 2018, 42, e12527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, L.L.; Corrêa, J.G.; da Silva Araújo, C.; Cardoso, W.S. Use of Ethanol to Improve Convective Drying and Quality Preservation of Fresh and Sucrose and Coconut Sugar-impregnated Strawberries. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2023, 16, 2257–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojdyło, A.; Figiel, A.; Oszmiański, J. Effect of drying methods with the application of vacuum microwaves on the bioactive compounds, color, and antioxidant activity of strawberry fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, D.; Jakubczyk, E. The freeze-drying of foods-the characteristic of the process course and the effect of its parameters on the physical properties of food materials. Foods 2020, 9, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk, E.; Tryzno-Gendek, E.; Kot, A.; Kamińska-Dwórznicka, A.; Nowak, D. Pre-Treatment Impact on Freeze-Drying Process and Properties of Dried Blueberries. Processes 2025, 13, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, D.; Kostyra, E.; Grzegory, P. Influence of drying methods on the structure. mechanical and sensory properties of strawberries. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 1859–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemzer, B.; Vargas, L.; Xia, X.; Sintara, M.; Feng, H. Phytochemical and physical properties of blueberries, tart cherries, strawberries, and cranberries as affected by different drying methods. Food Chem. 2018, 262, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, B.; Lv, W.; Xiao, H. Optimizing crispness and nutrient retention in carrot snacks: Multi-stage drying via microwave-infrared and negative pressure puffing with moisture-dependent transition. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2025, 105, 104171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, M.; Mujumdar, A. Berry drying: Mechanism, pretreatment, drying technology, nutrient preservation, and mathematical models. Food Eng. Rev. 2019, 11, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElGamal, R.; Song, C.; Rayan, A.M.; Liu, C.; Al-Rejaie, S.; ElMasry, G. Thermal Degradation of Bioactive Compounds during Drying Process of Horticultural and Agronomic Products: A Comprehensive Overview. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Chen, J.; Tiliwa, S.E.; Yan, W.; Roknul Azam, S.; Yuan, J.; Wei, B.; Zhou, C.; Ma, H. Effect of multi-mode dual-frequency ultrasound pretreatment on the vacuum freeze-drying process and quality attributes of the strawberry slices. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 78, 105714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacka, B.; Dziki, D.; Rudy, S.; Krzykowski, A.; Polak, R.; Dziki, L. Influence of Pretreatments and Freeze-Drying Conditions of Strawberries on Drying Kinetics and Physicochemical Properties. Processes 2022, 10, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalczyk, M.; Macura, R.; Matuszak, I. The effect of air-drying, freeze-drying and storage on the quality and antioxidant activity of some selected berries. J. Food Proces. Preserv. 2009, 33, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masztalerz, K.; Lech, K.; Wojdyło, A.; Nowicka, P.; Michalska-Ciechanowska, A.; Figiel, A. The impact of the osmotic dehydration process and its parameters on the mass transfer and quality of dried apples. Dry. Technol. 2020, 39, 1074–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacka, M.; Matys, A.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D. Innovative Technologies for Improving the Sustainability of the Food Drying Industry. Curr. Food Sci Technol. Rep. 2024, 2, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabi, K.P.; Fadeyibi, A.; Adebayo, K.R.; Gabriel, L.O. Effects of Osmotic Dehydration-Assisted Freezing at Different Pressure Rates on Mass Transfer and Quality of Fresh-Cut Apple. J. Food Process Eng. 2025, 48, e70133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylewicz, U.; Oliveira, G.; Alminger, M.; Nohynek, L.; Dalla Rosa, M.; Romani, S. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of Organic Fruits Subjected to PEF-Assisted Osmotic Dehydration. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 62, 102341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.; Tylewicz, U.; Suliburska, J.; Świeca, M.; Wojdyło, A.; Gramza-Michałowska, A. Vacuum and Ultrasound-Assisted Impregnation of Gala Apples with Sea Buckthorn Juice and Calcium Lactate: Functional Properties. Antioxidant Profile. and Activity of Polyphenol Oxidase and Peroxidase of Freeze-Dried Products. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2025, 75, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciurzyńska, A.; Lenart, A.; Siemiątkowska, M. Wpływ odwadniania osmotycznego na barwę i właściwości mechaniczne liofilizowanych truskawek. Acta Agroph. 2011, 17, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wrolstad, R.E.; Skrede, G.; Lea, P.; Enersen, G. Influence of sugar on anthocyanin pigment stability in frozen strawberries. J. Food Sci. 1990, 55, 1064–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, H.; Marzec, A.; Kowalska, J.; Ciurzyńska, A.; Czajkowska, K.; Cichowska, J.; Rybak, K.; Lenart, A. Osmotic dehydration of Honeoye strawberries in solutions enriched with natural bioactive molecules. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 85 Pt B, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, J.; Roszkowska, S.; Kowalska, H. The influence of chokeberry juice and inulin as osmotic-enriching agents in pre-treatment on polyphenols content and sensory quality of dried strawberries. Agric. Food Sci. 2019, 28, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasawa, M.M.G.; Mohan, C. Fruits as Prospective Reserves of Bioactive Compounds: A Review. Nat. Prod. Biopros. 2018, 8, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loayza-Salazar, S.; Siche, R.; Vegas, C.; Chávez-Llerena, R.T.; Encina-Zelada, C.R.; Calla-Florez, M.; Comettant-Rabanal, R. Novel Technologies in the Freezing Process and Their Impact on the Quality of Fruits and Vegetables. Food Eng. Rev. 2024, 16, 371–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, D.L.; Silveira, A.S.; Ronzoni, A.F.; Hermes, C.J.L. Effect of freezing rate on the quality of frozen strawberries (Fragaria x ananassa). Int. J. Refrig. 2022, 144, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, A.; Gill, P.P.S.; Singh, N.; Jawandha, S.K.; Arora, R.; Singh, A. Composite coating of xanthan gum with sodium nitroprusside alleviates quality deterioration in strawberry fruit. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 155, 110208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonzo-Macías, M.; Montejano-Gaitán, G.; Allaf, K. Texture Measurement of Dried Strawberry Slices. J. Texture Stud. 2014, 45, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacremont, C. Spectral composition of eating sounds generated by crispy, crunchy and crackly foods. J. Texture Stud. 1995, 26, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Hu, X.; Jia, X.; Ji, Z.; Wang, Z.; Shen, W. Correlation between acoustic characteristics and sensory evaluation of puffed-grain food based on energy analysis. J. Texture Stud. 2024, 55, e12832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akcicek, A.; Avci, E.; Tekin-Cakmak, Z.H.; Kasapoglu, M.Z.; Sagdic, O.; Karasu, S. Influence of Different Drying Techniques on the Drying Kinetics, Total Bioactive Compounds, Anthocyanin Profile, Color, and Microstructural Properties of Blueberry Fruit. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 41603–41611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samoticha, J.; Wojdyło, A.; Lech, K. The influence of different the drying methods on chemical composition and antioxidant activity in chokeberries. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 66, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelova, A.; Mendel, Ľ.; Solgajová, M.; Kolesárová, A.; Mareček, J.; Zeleňáková, L. Comparison of the influence of different fruit drying methods on the content of selected bioactive substances. J. Microbiol. Biotech. Food Sci. 2022, 12, e9223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lech, K.; Michalska, A.; Wojdyło, A.; Nowicka, P.; Figiel, A. The Influence of the Osmotic Dehydration Process on Physicochemical Properties of Osmotic Solution. Molecules 2017, 22, 2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, M.J.; Varo, M.; Mérida, J.; Serratosa, M.P. Influence of drying processes on anthocyanin profiles, total phenolic compounds and antioxidant activities of blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum). LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 120, 108931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.; Shun Ah-Hen, K.; Vega-Gálvez, A.; Morales, A.; García-Segovia, P.; Uribe, E. Effects of drying methods on quality attributes of murta (Ugni molinae turcz) berries: Bioactivity, nutritional aspects, texture profile, microstructure and functional properties. J. Food Proces. Eng. 2017, 40, e12511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojarska, J.E.; Czaplicki, S.; Zarecka, K.; Zadernowski, R. Phenolic compounds of selected varieties of strawberry. ŻYW Nauka. Technol. Jakość Supl. 2006, 2, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sarpong, F.; Yu, X.; Zhou, C.; Amenorfe, L.P.; Bai, J.; Wu, B.; Ma, H. The kinetics and thermodynamics study of bioactive compounds and antioxidant degradation of dried banana (Musa ssp.) slices using controlled humidity convective air drying. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2018, 12, 1935–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Bi, J.; Yi, J.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Ma, Y. Cell wall polysaccharides and mono-/disaccharides as chemical determinants for the texture and hygroscopicity of freeze-dried fruit and vegetable cubes. Food Chem. 2022, 395, 133574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code of Samples | Dry Matter Content (g/100 g) | Water Activity (-) | Particle Density (g/cm3) | Apparent Density (g/cm3) | Porosity (-) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-dehydrated | 87.20 ± 0.15 a | 0.275 ± 0.013 b | 0.163± 0.001 a | 1.228 ± 0.117 a | 0.87 ± 0.01 c |

| Sucrose 1 h | 90.96 ± 0.27 b | 0.261 ± 0.013 b | 0.199 ± 0.000 b | 1.368 ± 0.015 b | 0.85 ± 0.01 c |

| Sucrose 2 h | 91.74 ± 3.38 b | 0.298 ± 0.016 b | 0.239 ± 0.000 c | 1.383 ± 0.007 b | 0.82 ± 0.01 b |

| Sucrose 3 h | 94.50 ± 0.36 c | 0.284 ± 0.018 b | 0.329 ± 0.000 g | 1.405 ± 0.008 b | 0.77 ± 0.00 a |

| Chokeberry juice 1 h | 89.03 ± 1.58 b | 0.177 ± 0.005 a | 0.241 ± 0.000 d | 1.378 ± 0.035 b | 0.82 ± 0.00 b |

| Chokeberry juice 2 h | 89.02 ± 1.51 b | 0.185 ± 0.027 a | 0.256 ± 0.001 e | 1.423 ± 0.048 b | 0.82 ± 0.00 b |

| Chokeberry juice 3 h | 94.83 ± 1.43 c | 0.191 ± 0.001 a | 0.319 ± 0.000 f | 1.414 ± 0.008 b | 0.77 ± 0.00 a |

| Code of Samples | Energy of Acoustic Event (j.u.) | Number of AE Event | Amplitude of Sound (μV) | Force (N) | Work (mJ) | Crunchiness Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-dehydrated | 2610.83 ± 581.86 b | 2626 ± 563 b | 497.14 ± 51.66 cd | 70.51 ± 16.44 b | 285.17 ± 73.14 c | 9.21 ± 1.97 bc |

| Sucrose 1 h | 1827.13 ± 182.23 a | 1678 ± 263 ab | 451.75 ± 35.16 bc | 38.58 ± 5.54 ab | 155.28 ± 29.83 ab | 10.80 ± 1.70 c |

| Sucrose 2 h | 3931.55 ± 293.53 c | 8727 ± 695 c | 551.36 ± 21.45 d | 28.88 ± 4.79 a | 120.53 ± 32.91 a | 72.12 ± 5.75 e |

| Sucrose 3 h | 3420.86 ± 628.17 c | 8618 ± 502 c | 542.29 ± 28.90 d | 52.79 ± 20.08 ab | 197.23 ± 54.91 abc | 38.70 ± 15.00 d |

| Chokeberry juice 1 h | 1420.33 ± 150.03 a | 1907 ± 923 ab | 409.75 ± 45.92 ab | 130.02 ± 45.51 c | 475.25 ± 110.23 d | 5.25 ± 2.24 ab |

| Chokeberry juice 2 h | 1599.25 ± 205.42 a | 1759 ± 693 ab | 423.50 ± 47.72 ab | 150.53 ± 24.75 ab | 261.04 ± 108.52 bc | 6.74 ± 2.66 ab |

| Chokeberry juice 3 h | 1514.00 ± 169.23 a | 1471 ± 655 a | 389.89 ± 25.70 a | 187.53 ± 67.19 d | 426.83 ± 156.63 d | 3.44 ± 1.53 a |

| Code of Samples | Total Phenolic (mg Acid GAE/100 g d.m.) | Anthocyanin (mg Cy-3-glu/100 g d.m.) | Flavonoid (mg Quercetin/g d.m.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-dehydrated material | 1975.17 ± 35.32 a | 130.23 ± 14.18 b | 10.03 ± 0.78 a |

| Sucrose 1 h | 2581.30 ± 22.58 ab | 139.00 ± 1 97 b | 8.13 ± 0.18 a |

| Sucrose 2 h | 2669.40 ± 581.94 ab | 173.32 ± 5.71 cd | 16.24 ± 1.20 c |

| Sucrose 3 h | 3076.14 ± 271.14 b | 208.95 ± 2.47 e | 15.91 ± 0.18 c |

| Chokeberry juice 1 h | 4661.58 ± 32.14 c | 74.13 ± 5.47 a | 16.29 ± 0.39 c |

| Chokeberry juice 2 h | 4878.52 ± 287.06 c | 152.06 ± 7.09 bc | 17.03 ± 0.94 c |

| Chokeberry juice 3 h | 5000.80 ± 72.01 c | 200.34 ± 3.35 de | 15.14 ± 0.00 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marzec, A.; Kowalska, J.; Korolczuk, M.; Kowalska, H. Crunchiness of Osmotically Dehydrated Freeze-Dried Strawberries. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11704. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111704

Marzec A, Kowalska J, Korolczuk M, Kowalska H. Crunchiness of Osmotically Dehydrated Freeze-Dried Strawberries. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11704. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111704

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarzec, Agata, Jolanta Kowalska, Marcin Korolczuk, and Hanna Kowalska. 2025. "Crunchiness of Osmotically Dehydrated Freeze-Dried Strawberries" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11704. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111704

APA StyleMarzec, A., Kowalska, J., Korolczuk, M., & Kowalska, H. (2025). Crunchiness of Osmotically Dehydrated Freeze-Dried Strawberries. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11704. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111704