Abstract

Background and Objectives: To assess the impact of the February 2023 earthquake in Turkey on asthma patients’ clinical outcomes and healthcare use. Materials and Methods: This retrospective, single-center study included 280 asthma patients followed at an outpatient clinic between January 2022 and December 2023. Clinical assessments included physical examinations, pulmonary function tests (PFTs), chest X-rays, and, when indicated, skin prick tests (SPTs) for aeroallergen sensitivity. Results: Following the earthquake, outpatient visits for asthma significantly increased from 82 to 198 patients (p < 0.001), and hospitalizations due to asthma attacks rose markedly (p < 0.001). While respiratory function parameters did not differ significantly between periods, there was a significant increase in the number of patients requiring advanced treatment (p = 0.037). Concurrently, air quality deteriorated, with substantial increases in particulate matter (PM10) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) levels recorded post-earthquake. Conclusions: The earthquake was associated with a significant rise in asthma exacerbations and healthcare utilization, likely driven by environmental pollution, poor living conditions, and disruptions in healthcare services. Disaster preparedness is key to protecting respiratory health after major earthquakes.

1. Introduction

The February 2023 earthquake in Turkey was one of the most devastating disasters in recent history, leaving profound impacts on both infrastructure and public health. The destructive effects of the earthquake were amplified by the combined influence of its high magnitude (Mwg 7.7 Pazarcık, Kahramanmaraş earthquake), shallow depth, and severe winter conditions [1,2]. These factors not only caused large-scale destruction but also intensified the humanitarian crisis by creating widespread displacement, collapse of essential services, and heightened health risks. This catastrophic event once again emphasized the indispensable role of disaster preparedness and the necessity of establishing resilient healthcare response systems to mitigate adverse outcomes in vulnerable populations.

In the aftermath of large-scale disasters, infectious disease outbreaks are a major concern. Overcrowded shelters, insufficient access to potable water, inadequate sanitation, and the interruption of healthcare services collectively create ideal conditions for the spread of respiratory infections, gastrointestinal diseases, and even vector-borne illnesses. Moreover, the collapse of thousands of buildings released hazardous airborne particles into the environment, including asbestos, silica, and mold spores, all of which pose long-term risks to respiratory health [3]. The health effects of these exposures can persist for months or years, particularly in individuals with pre-existing chronic respiratory diseases such as asthma or allergic rhinitis, who are especially vulnerable to environmental triggers.

Beyond the initial collapse, the scale of structural damage was staggering. A damage assessment conducted by the Malatya Governor’s Office reported that approximately 106,000 houses were either destroyed or rendered uninhabitable [4]. While controlled demolition efforts were undertaken, insufficient precautions to minimize dust dispersion resulted in significant environmental pollution. In some cases, heavily damaged multi-story buildings were demolished using explosives, generating massive dust clouds visible from long distances and substantial enough to impede traffic flow. This extensive particulate matter exposure likely contributed to worsening air quality, which represents a recognized risk factor for exacerbations of asthma and allergic diseases.

At the same time, damage to major highways and transport infrastructure severely disrupted medical logistics during the acute phase of the disaster. Patients with chronic illnesses, particularly those dependent on the uninterrupted supply of biological agents or blood products requiring cold-chain storage, experienced substantial treatment delays. Interruptions in access to medications not only compromised disease management but also increased the risk of severe exacerbations and hospitalizations among patients with respiratory conditions.

Given these circumstances, populations with asthma and allergic rhinitis warrant special attention, as they are disproportionately affected by environmental and healthcare disruptions following natural disasters. Asthma, in particular, is highly sensitive to changes in air quality, exposure to aeroallergens, and psychosocial stressors, all of which are likely to be exacerbated in the context of a large-scale earthquake. Allergic rhinitis, often comorbid with asthma, also contributes to impaired respiratory health and reduced quality of life under these challenging conditions.

Therefore, investigating the acute and chronic effects of the February 2023 earthquake on patients with asthma and allergic rhinitis is of paramount importance; this study aims to investigate changes in healthcare visits, clinical symptom severity, and treatment patterns among asthma patients following the 2023 Malatya earthquake, ultimately evaluating clinical outcomes, treatment challenges, and environmental factors to inform disaster preparedness strategies and guide future healthcare interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Participant Selection, and Data Collection

A retrospective evaluation was conducted on 280 asthma patients who were regularly followed in the outpatient clinic between 1 January 2022 and 31 December 2023. Eligible patients were those with a confirmed diagnosis of asthma according to GINA criteria, while individuals with incomplete records or alternative chronic lung diseases were excluded. The respiratory system findings were assessed by physical examination, pulmonary function tests (PFTs), and chest X-rays when clinically indicated. All chest X-rays and PFTs were interpreted by an experienced hospital pulmonologist. Spirometric measurements were evaluated according to reference values adjusted for age, height, gender, and race. Demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and medications were retrospectively obtained from patient files.

Asthma treatment steps were arranged according to the Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention (GINA) 2024 guidelines [5]. If patients presented with allergic complaints, a skin prick test (SPT) was performed following standardized international protocols to evaluate aeroallergen sensitivity. SPT was performed using a standard allergen extract panel (Lofarma, Milan, Italy), with histamine serving as the positive control and a 50% glycerinated solution as the negative control. Tested aeroallergens included Cladosporium, Alternaria, Aspergillus, Blattella germanica (German cockroach), Mountain Cedar, Platanus, Betula (birch), Dermatophagoides farinae, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Phleum pratense (timothy grass), Lolium perenne, Chenopodium album, Plantago, Artemisia vulgaris (mugwort), Ambrosia, and Parietaria (wall pellitory). The pricks were applied to the volar surface of the forearm with sterile lancets at a depth of 1 mm, and reactions were evaluated after 20 min. A wheal with a mean diameter of ≥3 mm compared to the negative control was considered positive.

To investigate the potential association between asthma exacerbations and environmental exposures, air quality data for Malatya province were collected from the Turkish National Air Quality Monitoring Network. The Air Quality Index (AQI) was calculated based on the highest values recorded for monitored pollutants (PM10, SO2, and other parameters), providing an indicator of daily pollution levels and forecasted air quality conditions [6].

2.2. Ethics Committee Approval

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of İnönü University (İnönü University, GO 2024/6170 Date: 16 July 2024), and it adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and graphical illustrations were generated in Python version 3.10. Categorical variables were summarized as numbers (n) and percentages (%). The normality of numerical variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Normally distributed variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, whereas non-normally distributed variables were presented as median (minimum–maximum).

Comparisons between categorical variables were performed using the Pearson chi-square test or Yates’ corrected chi-square test when appropriate. For numerical variables, comparisons between two independent groups were carried out using the independent samples t-test if normality assumptions were satisfied. For comparisons across more than two independent groups, the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied. In cases where the Kruskal–Wallis test revealed statistical significance, post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni-adjusted Mann–Whitney U test. Effect sizes were reported using eta-squared (η2). A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

A total of 280 asthma patients, including 196 females and 84 males, were included in the study. The mean age of the female participants was 43.20 ± 15.21 years, while that of the male participants was 43.05 ± 14.35 years.

Before the earthquake, 82 (29.29%) patients visited the outpatient clinic for asthma; after the earthquake, this number increased to 198 (70.71%) (p < 0.001).

Among the patients who visited the outpatient clinic before the earthquake, 51 (62.2%) were female and 31 (37.8%) were male, with an average age of 45.76 ± 15.44 years. After the earthquake, 145 (73.2%) females and 53 (26.8%) males sought medical attention, with an average age of 42.08 ± 14.62 years. When comparing hospital visits before and after the earthquake based on gender and average age, no statistically significant differences were found (p = 0.067 and p = 0.061, respectively).

However, a significant relationship was observed between smoking habits and the earthquake. While 9 patients who visited the clinic before the earthquake were active smokers, this number increased to 24 after the earthquake (p = 0.48). The smoking history of patients who smoked before the earthquake was 21, 1 ± 18, 8 packs/year, compared to 8.2 ± 7.3 packs/year after the earthquake (p = 0.02). Additionally, thirteen asthma patients reported starting to smoke after the earthquake. When smoking rates (packs/year) were examined by gender, no statistically significant difference was found (p = 0.769).

In respiratory function tests, patients examined before the earthquake had a mean FEV1/FVC ratio (%) of 76.23 ± 8.48, a mean FEV1 ratio (%) of 85.53 ± 18.40, and a mean FVC ratio of 94.56 ± 15.54%. In patients examined after the earthquake, the corresponding values were 76.83 ± 8.29%, 87.96 ± 18.73%, and 96.35 ± 17.23%. No statistically significant differences were found between the pre- and post-earthquake respiratory function test parameters (p = 0.601, 0.342, and 0.442, respectively).

When respiratory function parameters were examined according to treatment steps, the mean FEV1/FVC ratio, mean FEV1 ratio, and mean FVC ratio were statistically lower in the difficult/severe asthma patient group compared to other groups (p <0.001 for all). Although there was no significant difference in treatment steps before and after the earthquake, a significant difference was observed in overall PFTs, with an increase particularly in patients with moderate and severe/difficult asthma (p = 0.037).

Before the earthquake, 7 patients used omalizumab, 2 used mepolizumab and 1 used benralizumab. After the earthquake, 8 patients used omalizumab, 13 used mepolizumab, and 6 used benralizumab.

The characteristics of the patients including their comorbidities, respiratory function parameters, and asthma severity are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The Characteristics of the Patients According to Their Accompanying Diseases, Respiratory Function Parameters, and Severity of Asthma.

When patients were categorized by age, the difficult/severe asthma group was significantly more common in those over 30 years of age (p < 0.001), while mild asthma was more prevalent in the 18–30 age range. No statistically significant difference in gender distribution was found with respect to treatment steps (p = 0.456).

Out of the total patients, 150 (73.9%) had rhinitis, 5 (2.5%) had nasal polyps, 19 (9.4%) had NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease (NERD), 14 (6.9%) had Asthma–COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS), 5 (2.5%) had bronchiectasis, 7 (3.4%) had obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), 2 (1.0%) had allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), and 1 (0.5%) had tuberculosis. Rhinitis was present in 37 patients before the earthquake and in 113 patients after the earthquake—a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001). Similarly, the increase in ACOS cases after the earthquake was statistically significant (p < 0.001). Although the number of NERD patients increased from 4 to 15, this change was not statistically significant.

SPT was performed on 111 female patients (63.8%) and 63 male patients (36.2%), with a mean age of 41.44 ± 14.26 years among those tested. Among the indoor allergens, sensitivity was detected as follows: Dermatophagoides farinae: 66.1%, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus: 58.6%, Blattella germanica: 49.4%, Aspergillus: 43.1%. The distribution of allergens in the skin prick test is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Distribution of Allergens in the Skin Prick Test.

In addition, eleven patients who visited the outpatient clinic before the earthquake and 27 patients after the earthquake were hospitalized due to asthma attacks. When combining hospitalizations from both the emergency department and the outpatient clinic, 21 patients were hospitalized before the earthquake, compared to 67 after the earthquake (p < 0.001). However, the mean duration of hospital stays did not differ significantly between the periods (p = 0.885).

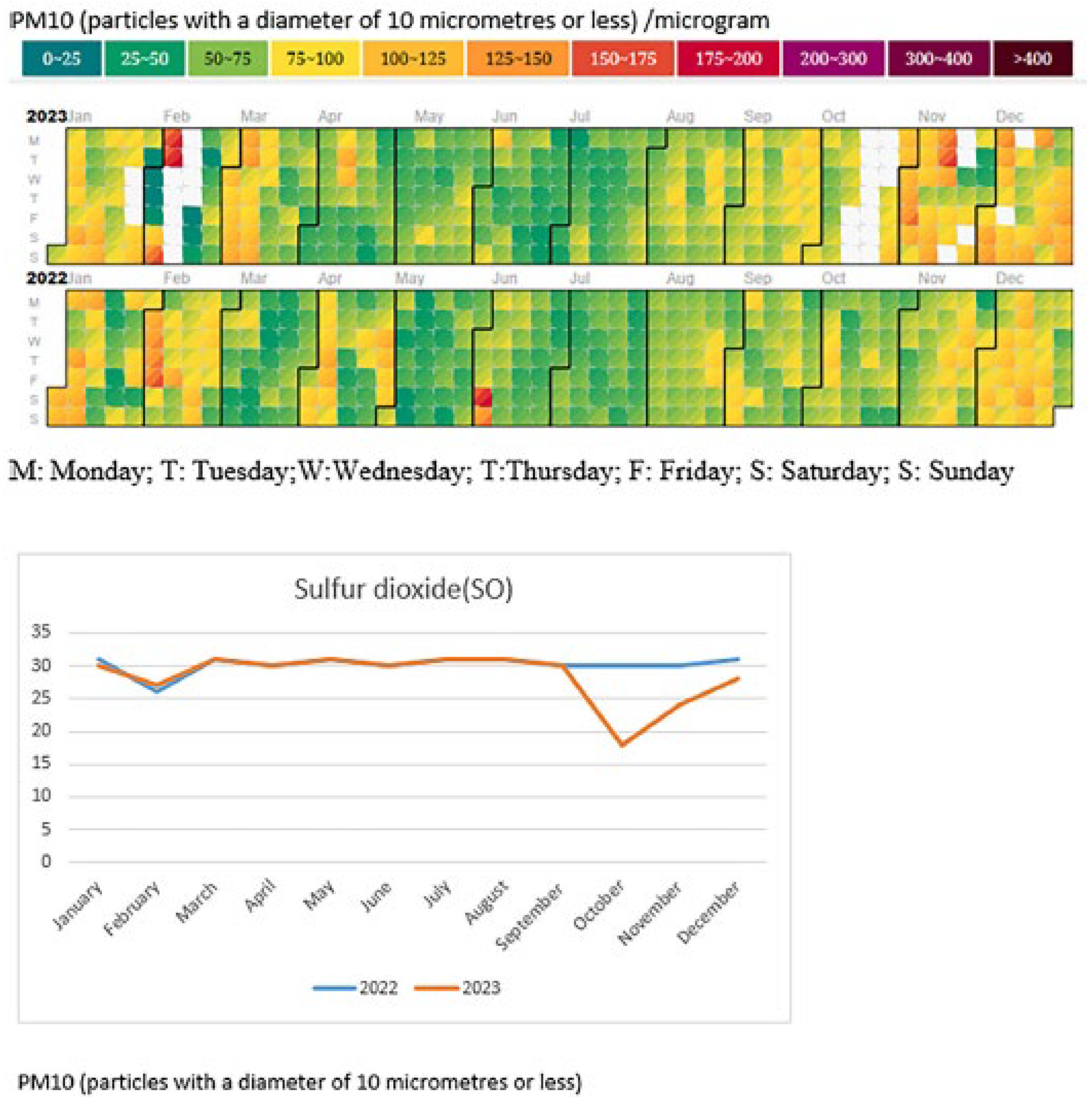

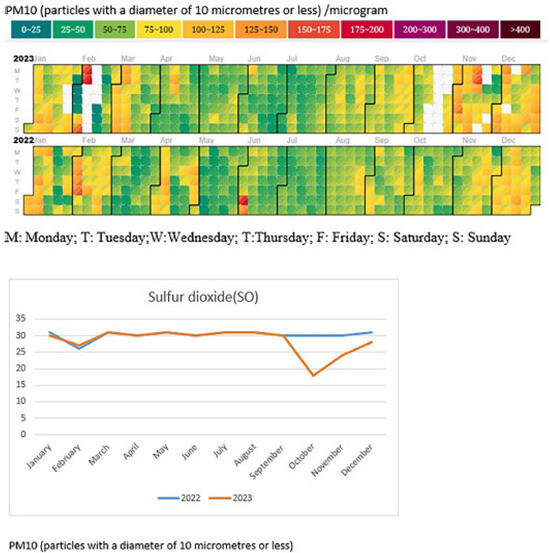

The air quality (Air Quality Index) in the center of Malatya province between 2022 and 2024 is shown in Figure 1. A comparison between 2022 and 2023 reveals a significant deterioration in air quality in 2023, particularly in PM10 and SO2 levels. Median values (and quartiles) of particles less than 10 µm in diameter (PM10) and SO2 by month, along with statistical evaluations, are presented in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Air quality index (PM10 and SO2) of Malatya center between 2022–2023.

Table 3.

Monthly Variations of PM10 and SO2 Concentrations with Statistical Analysis.

Figure 1 illustrates the monthly distribution of particulate matter less than 10 µm in diameter (PM10) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) concentrations. When compared to 2022, a notable deterioration in air quality was observed in 2023, particularly characterized by elevated PM10 levels and fluctuations in SO2 values during the autumn and winter months. These findings underscore the adverse changes in air quality following the earthquake, while detailed median values and statistical comparisons are provided in Table 3.

As shown in Table 3, monthly variations in PM10 and SO2 concentrations were statistically significant throughout the study period (PM10: H = 485.927, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.433; SO2: H = 335.972, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.300). The large effect sizes indicate that both pollutants displayed substantial temporal variability. For PM10, the highest median levels were observed in December 2023, November 2023, and February 2023, while similarly elevated values were recorded in January 2023 and December 2022, reflecting a distinct winter peak. In contrast, the lowest concentrations occurred during the summer months, particularly in July and June 2023.

SO2 followed a somewhat different seasonal trend, with higher concentrations in January 2022, August 2022, December 2022, and January 2023. Conversely, the lowest median values were recorded in November and December 2023, as well as in late spring and early summer months such as May 2022. Overall, these findings (Table 3) demonstrate that PM10 consistently peaked during late autumn and winter, whereas SO2 exhibited episodic increases, with elevated levels in both winter and selected summer months. Comparison of 2022 and 2023 further revealed significantly higher PM10 and SO2 concentrations in 2023, suggesting that post-earthquake conditions, including debris and urban destruction, may have contributed to increased air pollution.

4. Discussion

Turkey experienced a devastating earthquake in the early morning hours of Tuesday, 6 February 2023, in the southern part of the country. The earthquake resulted in 53,537 fatalities and more than 107,000 injuries, leaving the nation to face numerous expected and unexpected challenges [7].

During the acute phase, serious problems arose, including shelter shortages, difficulty accessing food, water, and fuel, and subzero temperatures due to winter conditions, which led to an increase in lower respiratory tract infections. In the days following the earthquake, issues such as collapsed buildings and power outages compounded the struggles of asthma patients. Many patients living in tents had no access to their medications, resulting in significant challenges in disease management.

In this study, patients using biological agents for asthma experienced problems related to cold chain logistics and drug delivery after the earthquake. Due to difficulties in supplying biological agents, systemic steroid use increased, further complicating disease control in patients with severe asthma. Early intervention and continuity of care measures, including timely medical evaluations, uninterrupted access to medications, and proactive disease monitoring, are essential to mitigate these complications.

Air pollution is a major factor contributing to the rise in respiratory and other inflammatory diseases, causing approximately 7 million deaths each year. In the subacute and chronic phases following the earthquake, various challenges emerged in treating patients with chronic lung diseases such as asthma [8]. Similarly, research on wildfire events—such as the 2018 California wildfires—has demonstrated that acute exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and other combustion-related air pollutants is strongly associated with increased rates of asthma-related emergency department visits and hospitalizations. These studies highlight the shared pathophysiological impact of various disaster-related airborne exposures, which can trigger airway inflammation, hyperresponsiveness, and symptom exacerbation in individuals with asthma. Taken together, this evidence supports the hypothesis that air pollution resulting from natural disasters—whether due to wildfires, earthquakes, or other sources—can exert significant and immediate adverse effects on respiratory health, especially in those with underlying chronic respiratory conditions [9].

Air pollution damages epithelial barriers, an essential part of the innate immune system, leading to the release of numerous cytokines and allergens that cause airway inflammation. Particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) has significant inflammatory and tissue-destructive effects on the respiratory system; for example, PM10 can impair alveolar epithelial cells by reducing occludin levels and causing dissociation of ZO-1 [10].

During the acute phase of the earthquake, PM10 levels peaked at 175 µg/m3 over 24 h, far exceeding the Ministry of Environment, Urbanization, and Climate Change’s threshold of 40 µg/m3. This increase was particularly notable between September and December, when the demolition of severely damaged buildings intensified. It was observed that 72% of patients who visited the outpatient clinic after the earthquake did so during these months, which may be associated with increased air pollution. Damage to the airway epithelial barrier, especially in patients with severe and difficult-to-treat asthma, exacerbated their conditions.

Although the deterioration in air quality following the earthquake is well-documented in this study, establishing a direct temporal relationship between pollutant exposure and asthma-related clinical outcomes is inherently limited by the retrospective design and post-disaster disruptions in healthcare services. For instance, in February 2023—the month the earthquake struck—outpatient clinics were completely shut down, with hospitals focusing solely on emergency, inpatient, and intensive care services. Consequently, no outpatient visits were recorded during that month. Outpatient services resumed gradually, with routine appointments becoming feasible only by June 2023. Notably, the number of asthma patients seen in the outpatient clinic increased from 8 in June to 9 in July, rising significantly to 36 in August. This temporal increase in patient visits coincided with the commencement of large-scale demolition of heavily damaged buildings starting in August and continuing for several months thereafter. Environmental monitoring data revealed a concurrent rise in PM10 levels beginning in August, peaking in December 2023—a month which also recorded the highest number of asthma outpatient visits (n = 48) during the entire 24-month study period. This co-occurrence between demolition-driven air pollution and increased asthma-related healthcare utilization strongly suggests a potential environmental impact on respiratory health. Implementation of health education programs for patients and caregivers, as well as preventive and mitigation strategies at the community level, can support resilience and reduce risk during post-disaster recovery. Damage to the airway epithelial barrier, especially in patients with severe and difficult-to-treat asthma, has been linked to worsening clinical conditions. In this study, both the number of asthma patients seeking care and hospitalizations due to asthma significantly increased following the earthquake, potentially associated with disruptions in drug supply and deteriorating air quality. Notably, an increased need for biological agents was observed, possibly reflecting challenges in asthma control in the post-disaster period.

The increase in patients receiving biological therapies such as Mepolizumab and Benralizumab, though not statistically significant (p = 0.085), may reflect a shift towards managing more severe asthma cases post-earthquake. This could be attributed to worsening disease severity due to environmental and psychosocial stressors. The increased demand for advanced biological treatments underscores the impact of the earthquake on asthma control and highlights the need for strategies ensuring continuity of care, preventive health measures, and public health preparedness in disaster-affected populations.

Previous studies on the Hanshin-Awaji and Chuetsu earthquakes found no asthma exacerbations in patients using regular inhaled corticosteroids [11,12]. However, similar to our findings, the incidence of pneumonia and asthma exacerbations increased within one month after the Great Hanshin-Awaji earthquake [13], and changes in the incidence of asthma and other allergic diseases were observed following the Great East Japan earthquake [14].

In our study, the increase in outpatient visits for asthma was linked to disruptions in regular inhaler use, potentially associated with drug shortages and deteriorating living conditions. Additionally, the demolition of severely damaged buildings in Malatya province without necessary precautions was associated with increased PM10 levels and significant deterioration in air quality, which may have contributed to poor asthma control and a rise in asthma attacks [15]. Early intervention, preventive measures, and health education can help mitigate these risks, ensuring patients maintain disease management even during disaster recovery.

Several studies have examined changes in smoking behavior after disasters. A telephone survey following the 11 September terrorist attacks found an increase in smoking rates [16]. Similarly, research after the New Zealand earthquake reported increased smoking prevalence and nicotine dependence [17], and a study six years after the 1999 Marmara earthquake in Turkey noted that some victims who began smoking developed a cigarette addiction [18]. In our study, an increase in smoking rates among asthma patients was observed after the earthquake; regrettably, those who started smoking remain active smokers, suggesting a possible association between disaster-related stress and smoking behavior.

Additionally, several comorbid conditions, including rhinitis and asthma–COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS), showed a statistically significant increase after the earthquake (p < 0.001). However, given the retrospective nature of this study and the use of an existing patient cohort, it is unlikely that the true prevalence of these chronic conditions changed during the study period. Instead, this finding probably reflects a change in the case-mix of patients presenting for care after the earthquake, where patients with more severe symptoms or multiple comorbidities were more likely to seek medical attention. Therefore, these results should be interpreted as an increase in healthcare utilization by more complex cases rather than a true rise in the incidence of these conditions.

During an earthquake, damage to infrastructure such as water pipes and sewer systems can lead to damp and poorly ventilated living conditions, especially in temporary shelters and overcrowded housing. These environments are conducive to fungal proliferation and increased levels of indoor allergens, including house dust mites (HDMs) and molds like Aspergillus. Exposure to such allergens is well-documented to exacerbate allergic asthma and allergic rhinitis, contributing to increased respiratory morbidity in vulnerable populations [19,20,21]. Mold allergies, which affect between 2% and 18% of the general population, are particularly associated with higher asthma prevalence in damp environments. In our study, Aspergillus sensitization was identified in 43.1% of patients, a notably high rate that likely reflects increased fungal exposure due to the post-earthquake environmental conditions.

Additionally, the sensitivity to house dust mites was found to be 66% in our cohort, significantly higher than the 15.9% prevalence reported in a large-scale German study involving approximately 11 million adults [22]. This marked increase may be attributed to the increased exposure to HDMs in damaged and poorly maintained dwellings, where cleaning and allergen control are challenging. These findings suggest that the post-earthquake living conditions—characterized by dampness, dust, overcrowding, and disrupted sanitation—likely played a substantial role in worsening asthma control and increasing allergic sensitization among patients.

Although our study did not include direct environmental sampling of allergen levels in homes or shelters, the high rates of sensitization observed support the hypothesis that increased allergen exposure is an important factor in post-disaster asthma exacerbations. Future prospective studies incorporating environmental allergen measurements would be valuable to confirm this link. Nonetheless, our data highlight the critical need for early intervention, health education, continuity of care, and broader public health preparedness measures, including preventive and mitigation strategies, to reduce respiratory morbidity following disasters.

The German Severe Asthma Registry (GAN) reported an average age of 38 years for severe early onset asthma. In our study, the incidence of severe asthma was higher in patients over 30 years of age [23], indicating that older asthma patients were more affected by the earthquake.

5. Limitations

The most important limitations of this study are its retrospective design and the limited reproducibility of the findings. Since the study was conducted at a single center, the results may not be generalizable to all populations affected by the earthquake. Additionally, the retrospective nature of data collection may have introduced information bias, as some patient records were incomplete or lacked detailed clinical information.

Another limitation is that environmental exposure data, such as particulate matter (PM10) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) levels, were obtained from regional monitoring stations rather than from direct individual-level measurements. As a result, these values may not accurately reflect each patient’s actual exposure.

Moreover, heterogeneity in patients’ baseline disease severity, medication adherence, and psychosocial stress levels could not be fully controlled. Psychological trauma caused by the earthquake is a well-established trigger associated with asthma exacerbations, and may have significantly influenced clinical outcomes. This study lacked control for such psychosocial stressors, which likely acted as important confounding variables. Therefore, the observed effects are probably the result of multiple interacting factors, including air pollution, poor living conditions, medication disruptions, and psychological stress, making it impossible to disentangle their individual contributions within the scope of this analysis.

Finally, although this study identifies significant associations between earthquake-related conditions and asthma exacerbations, causality cannot be established due to the observational nature of the design. Future prospective, multi-center studies involving larger cohorts and incorporating detailed individual-level exposure assessments and psychosocial evaluations are warranted to confirm and expand upon these findings.

6. Conclusions

Although the existing literature supports a relationship between earthquakes and increased respiratory health risks, further research is needed to better understand this connection. Factors such as age, pre-existing respiratory conditions, socioeconomic status, and access to healthcare may influence the severity and duration of respiratory pathologies following an earthquake. Gaining insight into these factors will help tailor interventions and support services to those most in need.

We therefore recommend that home healthcare services be immediately increased after an earthquake, alongside the rapid establishment of chronic medication supply chains to ensure uninterrupted treatment for patients with asthma and other chronic respiratory diseases. Early intervention strategies and continuity of care should be emphasized to prevent exacerbations and ensure effective long-term management. Early discharge programs should be developed to assist in managing chronic conditions on-site, reducing hospital burden while maintaining continuity of care.

Additionally, distributing personal protective equipment such as N95 masks or portable air purifiers to high-risk asthmatics in heavily affected zones could mitigate the adverse effects of elevated particulate matter and dust exposure following disaster-related demolition and reconstruction activities. Health education initiatives for patients and caregivers, focusing on disease management, environmental triggers, and emergency preparedness, can further enhance outcomes.

Mental health support should also be integrated into post-disaster asthma management protocols, as psychological stress can exacerbate respiratory symptoms and negatively impact disease control. High-magnitude earthquakes may indirectly exacerbate respiratory problems by increasing environmental pollution through dust, particulate matter, and other airborne contaminants released during the destruction and reconstruction activities. These changes in air quality can have both acute and long-term impacts on human health and the environment. Therefore, integrating air quality monitoring and control measures into disaster management plans is essential. By addressing environmental and human health factors simultaneously, disaster response strategies can provide a more comprehensive framework to reduce both the immediate and long-term burden of respiratory diseases following natural disasters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B.K.; methodology, S.B.K. and I.B.C.; formal analysis, I.B.C. and Z.K.; resources, S.B.K., I.B.C. and Z.K.; data curation S.B.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B.K., I.B.C. and Z.K.; writing—review and editing, S.B.K., I.B.C. and Z.K.; visualization, I.B.C. and Z.K.; supervision, S.B.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There are no financial supports.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Inonu University (Inonu University, GO 2024/6170 Date: 16 July 2024) and it adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Access to the dataset requires permission and can be obtained by contacting Saltuk B. Kaya (saltukbugrakaya@gmail.com) with appropriate justification for data use.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Das, R.; Sharma, M.L.; Wason, H.R.; Choudhury, D.; Gonzalez, G. A seismic moment magnitude scale (Mwg). Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2019, 109, 1542–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R. Limitations of Mw and M Scales: Compelling Evidence Advocating for the Das Magnitude Scale (Mwg)—A Critical Review and Analysis. 2025. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/129060418/Limitations_of_M_w_and_M_Scales_Compelling_Evidence_Advocating_for_the_Das_Magnitude_Scale_M_wg_A_Critical_Review_and_Analysis (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Bayram, H.; Rastgeldi Dogan, T.; Şahin, Ü.A.; Akdis, C.A. Environmental and health hazards by massive earthquakes. Allergy 2023, 78, 2081–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Republic of Turkey; Malatya Governorate. Deprem Durum Çizelgesi. Available online: http://www.malatya.gov.tr/08052023-deprem-durum-cizelgesi (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). 2024 GINA Main Report. Available online: http://www.ginasthma.org (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Republic of Turkey; Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change. Air Quality Data Bank (2022–2024): Air Pollution and AQI Data. Available online: https://sim.csb.gov.tr/STN/STN_Report/StationDataDownloadNew (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Mavrouli, M.; Mavroulis, S.; Lekkas, E.; Tsakris, A. The Impact of Earthquakes on Public Health: A Narrative Review of Infectious Diseases in the Post-Disaster Period Aiming to Disaster Risk Reduction. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomita, K.; Hasegawa, Y.; Watanabe, M.; Sano, H.; Hitsuda, Y.; Shimizu, E. The Totton-Ken Seibu earthquake and exacerbation of asthma in adults. J. Med. Investig. 2005, 52, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, J.A.; Kioumourtzoglou, M.-A.; Elser, H.; Walker, D.; Taylor, S.; Adams, S.; Aguilera, R.; Benmarhnia, T.; Catalano, R. Wildfire particulate matter in Shasta County, California and respiratory and circulatory disease-related emergency department visits and mortality, 2013–2018. Environ. Epidemiol. 2020, 5, e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caraballo, J.C.; Yshii, C.; Westphal, W.; Moninger, T.; Comellas, A.P. Ambient particulate matter affects occludin distribution and increases alveolar transepithelial electrical conductance. Respirology 2011, 16, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodama, A.; Horikawa, T.; Suzuki, T.; Ajiki, W.; Takashima, T.; Harada, S.; Ichihashi, M. Effect of stress on atopic dermatitis: Investigation in patients after the great hanshin earthquake. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1999, 104, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Iguchi, S.; Ota, K.; Sakagami, T.; Gejyo, F.; Suzuki, E. The impact of the Chuetsu earthquake on asthma control. Allergol. Int. Off. J. Jpn. Soc. Allergol. 2007, 56, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takakura, R.; Himeno, S.; Kanayama, Y.; Sonoda, T.; Kiriyama, K.; Furubayashi, T.; Yabu, M.; Yoshida, S.; Nagasawa, Y.; Inoue, S.; et al. Follow-up after the Hanshin-Awaji earthquake: Diverse influences on pneumonia, bronchial asthma, peptic ulcer and diabetes mellitus. Intern. Med. 1997, 36, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagashima, H.; Fujimura, I.; Nakamura, Y.; Utsumi, Y.; Yamauchi, K.; Takikawa, Y.; Yokoyama, Y.; Sakata, K.; Kobayashi, S.; Ogawa, A. Changes in pulmonary function of residents in Sanriku Seacoast following the tsunami disaster from the Great East Japan Earthquake. Respir. Investig. 2018, 56, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manisalidis, I.; Stavropoulou, E.; Stavropoulos, A.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Environmental and Health Impacts of Air Pollution: A Review. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlahov, D.; Galea, S.; Ahern, J.; Resnick, H.; Boscarino, J.A.; Gold, J.; Bucuvalas, M.; Kilpatrick, D. Consumption of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana among New York City residents six months after the September 11 terrorist attacks. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2004, 30, 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erskine, N.; Daley, V.; Stevenson, S.; Rhodes, B.; Beckert, L. Smoking prevalence increases following Canterbury earthquakes. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 596957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceyhan, E.; Ceyhan, A.A. Earthquake survivors’ quality of life and academic achievement six years after the earthquakes in Marmara, Turkey. Disasters 2007, 31, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Kreiss, K.; Cox-Ganser, J.M. Rhinosinusitis and mold as risk factors for asthma symptoms in occupants of a water-damaged building. Indoor Air 2012, 22, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpe, R.A.; Bearman, N.; Thornton, C.R.; Husk, K.; Osborne, N.J. Indoor fungal diversity and asthma: A meta-analysis and systematic review of risk factors. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 135, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanchongkittiphon, W.; Mendell, M.J.; Gaffin, J.M.; Wang, G.; Phipatanakul, W. Indoor environmental exposures and exacerbation of asthma: An update to the 2000 review by the Institute of Medicine. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 123, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, K.-C. Frequency of sensitizations and allergies to house dust mites. Allergo J. Int. 2022, 31, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lommatzsch, M.; Taube, C.; Hamelmann, E.; Milger-Kneidinger, K.; Skowasch, D.; Jandl, M.; Schmitz, F.; Koerner-Rettberg, C.; Idzko, M.; Buhl, R. Type 2 biomarker expression according to age of asthma onset: An analysis of the German severe asthma registry (GAN). Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60, 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).