Abstract

Cloud liquid water content (CLWC) based on microwave radiometer data was investigated in this study. First, its consistency with radiosonde-based CLWC was established. Integrated CLWC was also checked against the liquid water path. CLWC performance in four weather types was considered: dense fog, clouds in spring, rainstorms, and typhoons. CLWC provides new insights into weather events. In particular, it could be useful for nowcasting low visibility associated with sea fog. It was also found to be inversely proportional to visibility in two cases of low visibility in Hong Kong. In springtime, low-level clouds and liquid water were found to exist extensively inside clouds. In rainstorm cases, supercooled cloud liquid water was absent during heavy rain but may exist within clouds when rain stops or light rain occurs. Similar observations were made in typhoon cases, namely during the direct impact of Typhoon Wipha on Hong Kong. Supercooled cloud liquid was present when outer rainbands of the typhoon affected Hong Kong with a smaller amount of rainfall. However, when Hong Kong was hit by a typhoon’s eyewall, rain was heavier, and supercooled liquid water was absent. These features are consistent with the radiosonde-based CLWC profiles. Radiometer-based CLWC is pseudocontinuous and provides additional insight into liquid water distribution in clouds under various weather conditions.

1. Introduction

Cloud liquid water with integrated values and vertical profiling is an area of active research. Previous studies have used remote sensing techniques utilising meteorological satellite data [1,2,3,4,5] to derive cloud liquid water. Aircraft measurements to determine the parameters related to liquid water in clouds have also been conducted, as reported in the literature [6]. Recently, the use of ground-based microwave radiometer measurements to determine aerosol optical depth has become more common [7]. Studies have also been conducted to compare observations from microwave radiometer and radiosonde readings in densely populated urban areas in Houston, Texas, United States of America [8].

The Hong Kong Observatory (HKO) operates two ground-based multichannel microwave radiometers to continuously measure the vertical profiles of temperature and humidity [9]. One is located at King’s Park, near the city centre while another is located at Chek Lap Kok, near the Hong Kong International Airport. Moreover, the radiosonde station, located at King’s Park, launches upper-air soundings two times a day regularly at 00Z and 12Z, with additional soundings at 06Z once every week [10]. These instruments provide important information on water vapour in the troposphere. However, there have been no vertical profiling measurements of liquid water.

The Humidity And Temperature PROfiler (HATPRO) microwave radiometer has been used at HKO and provides cloud liquid water profiles using a proprietary algorithm from field measurement campaigns [11]. In the past, no direct measurements have been conducted in the Hong Kong International Airport to verify the derived profiles. For aviation applications, the measurement of supercooled liquid water requires the establishment of local technology to measure cloud liquid water. With the deployment of a microwave radiometer at the upper air sounding station at King’s Park, measurements from microwave radiometer and radiosonde, both available at the same location, can be compared and verified. Amaireh et al. [12] developed a machine learning methodology to retrieve the liquid water profile based on radiosonde and radiometer data from Hong Kong, but the training dataset is limited to only six months. In this study, the training dataset was extended to cover three years for a more robust algorithm covering different weather situations across the year.

This paper aims to perform a systematic comparison of the radiosonde-based and radiometer-based cloud liquid profiles to validate the operational applicability of their derived cloud liquid water information. Radiometer measurements have a much higher frequency and can give more rapid assessment of cloud liquid water content (CLWC) as compared with radiosonde. The applicability of CLWC derived from radiometer measurements was also analysed and discussed based on selected weather events in 2024 and 2025, which include two dense fog cases: one liquid water cloud case and one supercooled liquid water case. The outcomes discussed in the paper are essential for understanding the applicability of cloud liquid water content derived from radiometer measurements in Hong Kong via comparison with the radiosonde measurements. This will help in the better utilisation of microwave radiometer in Hong Kong in operational forecasting of weather events like fog, rain, or showers.

2. Methodology

Cloud liquid water content (CLWC) profiles were generated using a machine learning framework, as described by Amaireh et al. [13], trained on the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecast (ECMWF) re-analysis v5 data for the Hong Kong region. Technical details of the methodology can be found in Amaireh et al. [12].

An expanded dataset spanning from 2021 to 2023, which included pressure (hPa), temperature (K), relative humidity (%), and specific humidity (kg/kg), along with temporal features, such as year, month, day, and hour, was utilised to re-train the machine learning model. Approximately 6.73 million samples were used.

To ensure data quality, a hybrid metaheuristic optimisation algorithm, combining Antlion and Grasshopper Optimisation techniques, was used to identify the optimal data cleaning parameters. This involved percentile-based outlier detection, interpolation (e.g., linear and nearest), and smoothing methods (e.g., Gaussian and moving median), all aimed at reducing noise and improving the input–output relationship.

A bagged ensemble of decision trees was selected as the final model due to its superior performance over the other tested methods [3]. The model was trained using 80% of the dataset, validated using 5-fold cross-validation, and tested on the remaining 20%. Evaluation metrics, including root-mean-square error, mean absolute error, and correlation coefficient squared (R2), confirmed the accuracy and robustness of the model.

Meteorological parameters can serve as inputs for the trained model and the model gives CLWC values in kg/m3 for 21 pressure levels ranging from 1000 to 250 hPa, with 25 hPa level intervals between 1000 hPa and 750 hPa and 50 hPa level intervals between 750 hPa and 250 hPa. The algorithm was implemented for operational use and enabled the rapid generation of consistent CLWC profiles based solely on the model trained on the ECMWF reanalysis v5 data.

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Comparison of Radiosonde- and Radiometer-Based CLWC

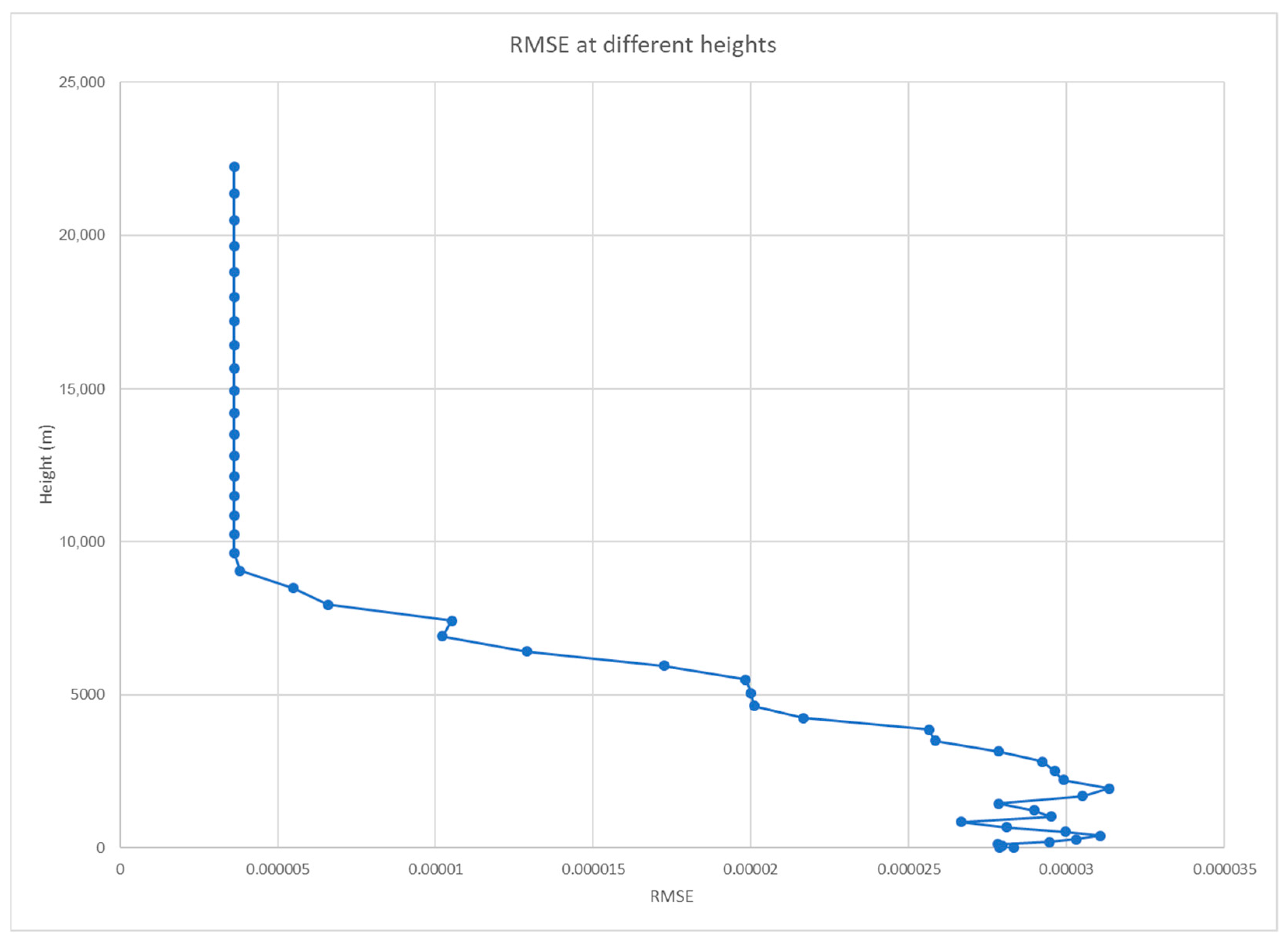

Cloud liquid water content (CLWC) derived from radiosonde and radiometer measurements based on the method described in Section 2 are compared and analysed in this section. The verification timeframe is January to March 2025. The root-mean-square difference between the radiometer- and radiosonde-based CLWC at various altitudes is shown in Figure 1. In the first 3 km or so above ground, the difference is 0.00003 kg/m3. As for higher altitudes about 3 to 9 km, the root-mean-square difference show a decreasing trend. Above 9 km, the difference is the smallest at 0.000004 kg/m3. Although there are differences in the radiometer- and radiosonde-based CLWC, the difference is small, and the variability against height is insignificant as compared with the absolute values of CLWC.

Figure 1.

Root-mean-square error (RMSE) of radiometer-based CLWC with respect to radiosonde-based CLWC as a function of height (m) based on data from Hong Kong between January to March 2025.

Although no other independent measurements are available to confirm the accuracy of the derived CLWC, the two datasets are considered internally consistent and may be used to study liquid water profiles under various weather conditions.

3.2. Comparison of Liquid Water Path

The training dataset did not include January to March 2025; therefore, the latter study period served as an independent sample to test the performance of the radiometer-based CLWC. Liquid water path (LWP) based on the ECMWF reanalysis v5 (ERA5) at a grid point close to King’s Park, Hong Kong, was used to evaluate the performance of the radiometer-based LWP, which was calculated from the vertical integral of the CLWC over various heights:

where is the thickness between levels i and i + 1 (in metres) [14].

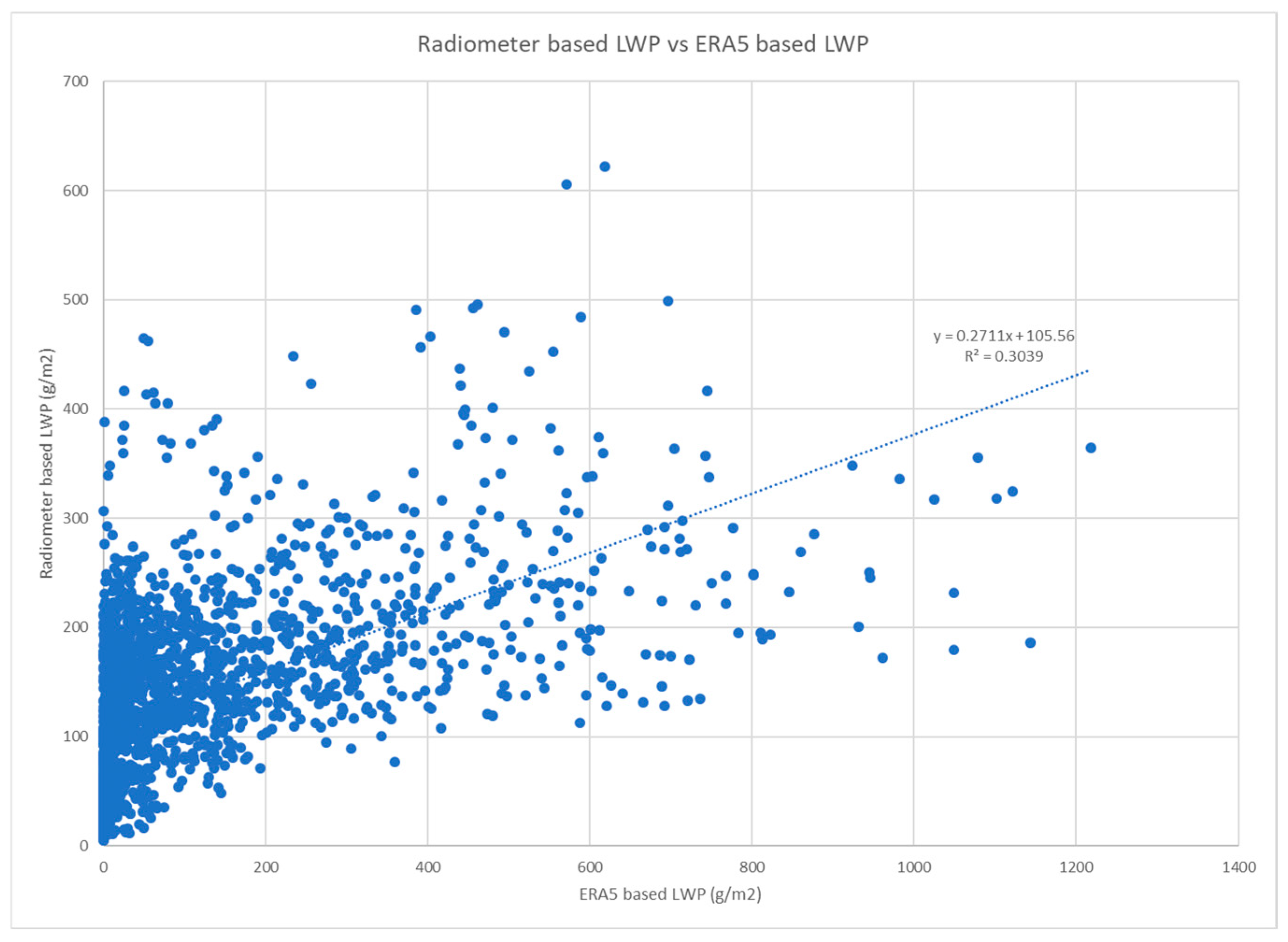

A comparison of ERA5 LWP and radiometer-based LWP is shown in Figure 2 for the period January to March 2025. The two datasets are closely correlated; the correlation coefficient R2 is approximately 0.3.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot of ERA5-based LWP and radiometer-based LWP for January to March 2025.

3.3. Applicability of CLWC to Weather Events

3.3.1. Fog Case of 6 March 2024

In Hong Kong, fog mostly occurs during spring. Some typical fog cases have been reported by Chan and Li [15]. Although numerical weather prediction models are capable of capturing the chance of fog occurrence in southern China, the onset of dense fog and the minimum visibility that may be reached still depend on the nowcasting approach. In this paper, two dense fog cases in Hong Kong are documented to determine whether radiometer-based CLWC could be useful in this regard.

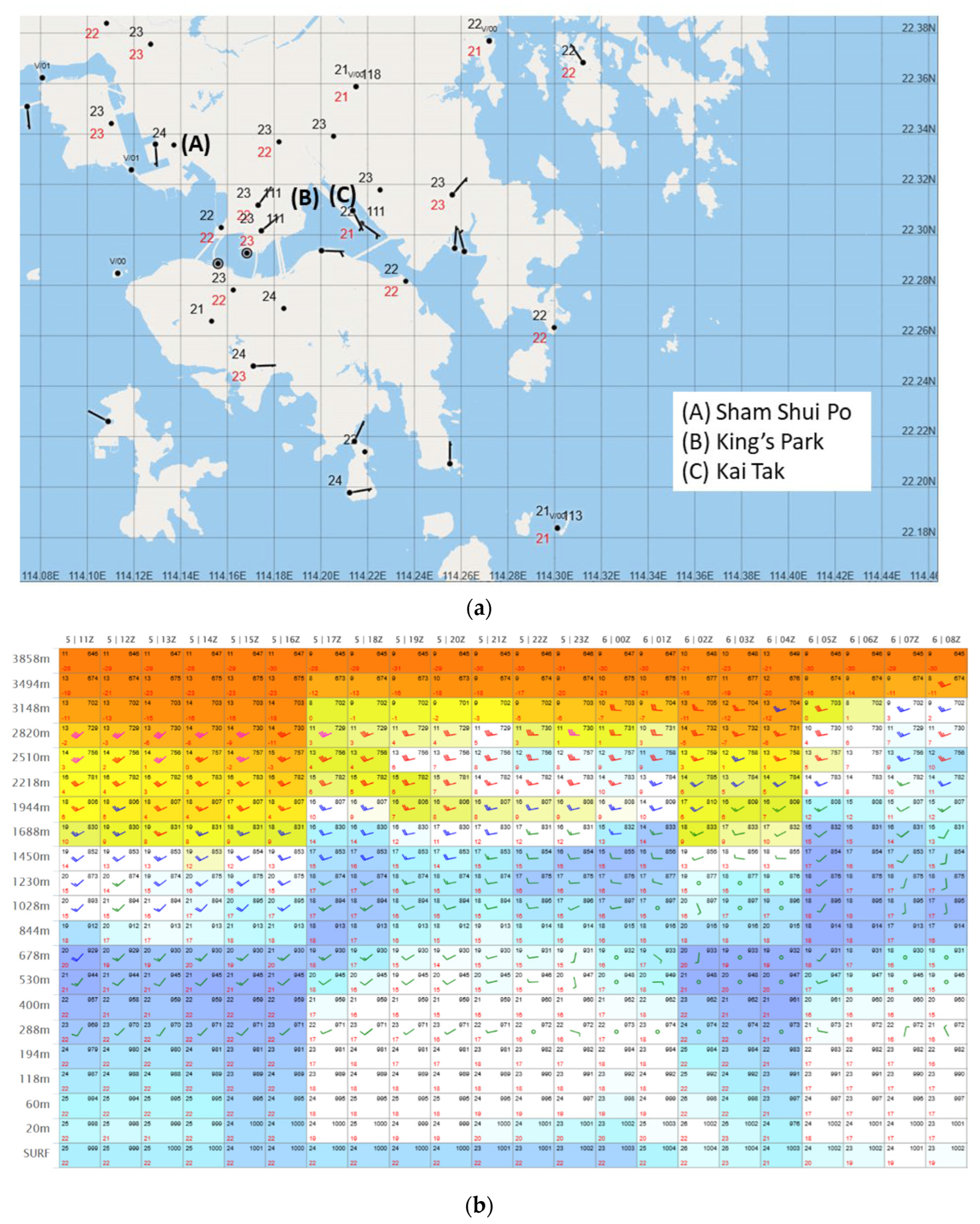

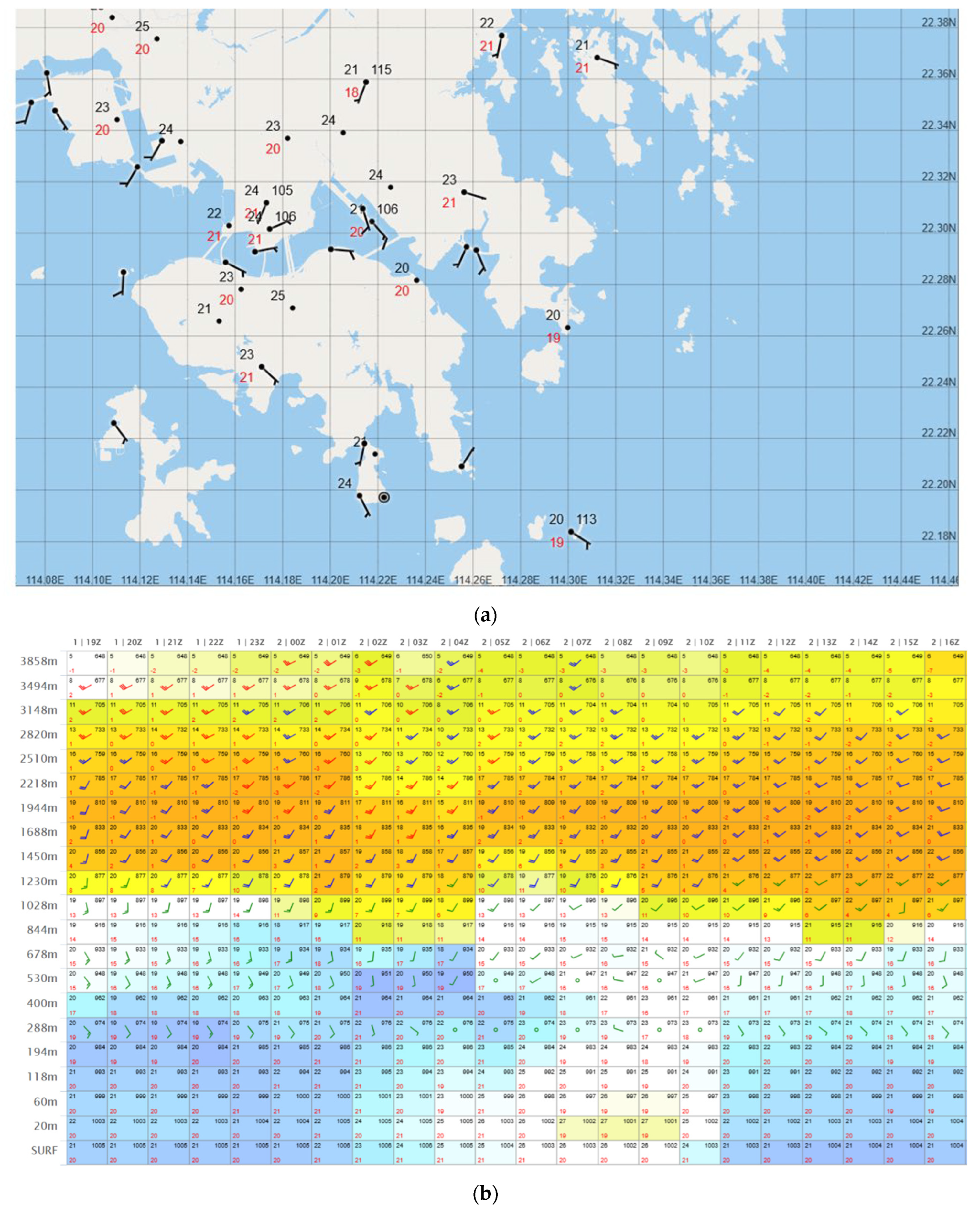

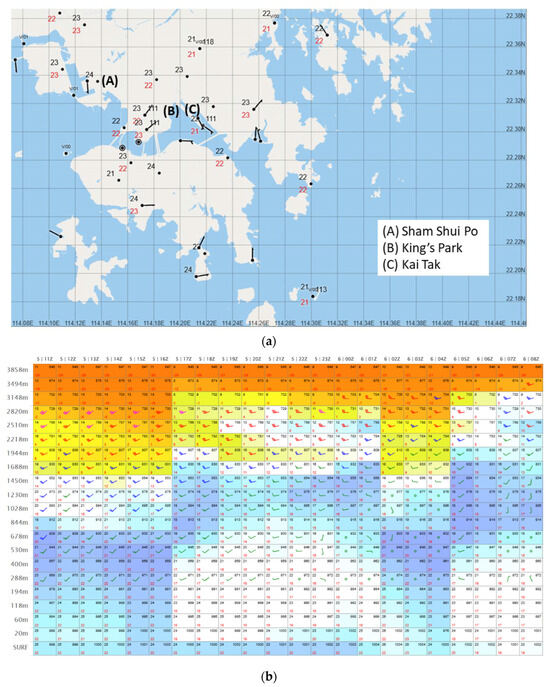

Hong Kong was affected by dense fog on 6 March 2024. In the eastern part of Hong Kong, the foggiest region, elevator malfunctions were reported in very humid situations, causing major inconvenience to high-rise apartment residents [16]. Although it is normal to have foggy weather in spring in Hong Kong, such widespread high-humidity weather conditions are not common. Surface observations at the time of the event are shown in Figure 3a. Light southeasterly winds prevailed over eastern Hong Kong, which is a common foggy weather pattern. At various weather stations, temperatures and dew points were similar. Wind profiler measurements of wind, temperature, and humidity from the radiometer placed in the urban areas of Hong Kong are shown in Figure 3b. The time in that figure is given in UTC, and Hong Kong time (UTC + 8 h). Our findings show a shallow layer of higher-humidity air, up to ~20 m above the ground, but this information alone may not indicate dense fog.

Figure 3.

(a) Surface data in Hong Kong at 00:00 UTC on 6 March 2025, showing a 10 min mean wind direction and wind speed (wind barb), temperature (black), and dew point (red). (b) Radiometer temperature, relative humidity (colour-shaded, with moist/dry represented as cool/warm colours), and vertical wind profile are from the radar wind profiler at Sham Shui Po. Time is in UTC.

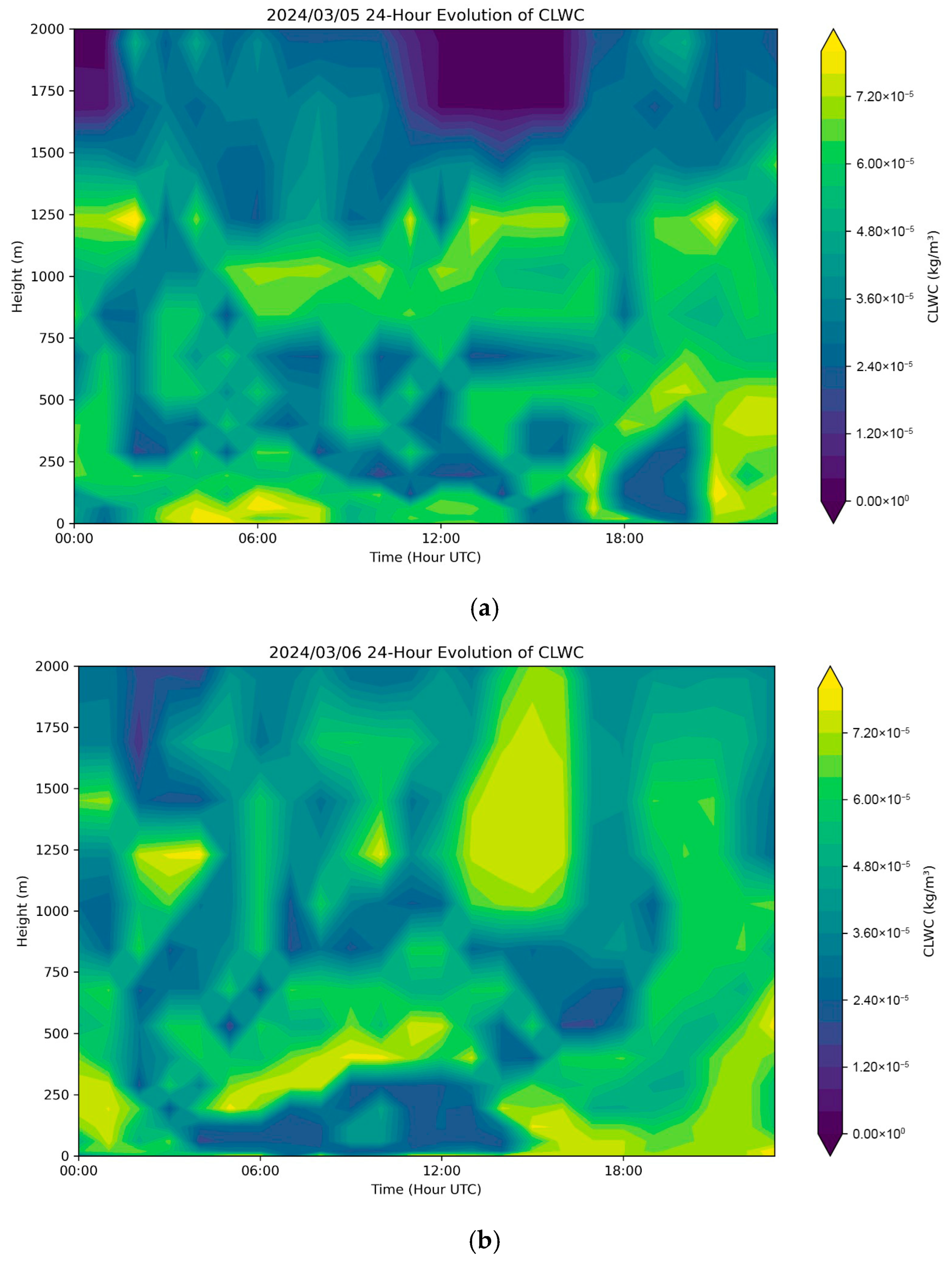

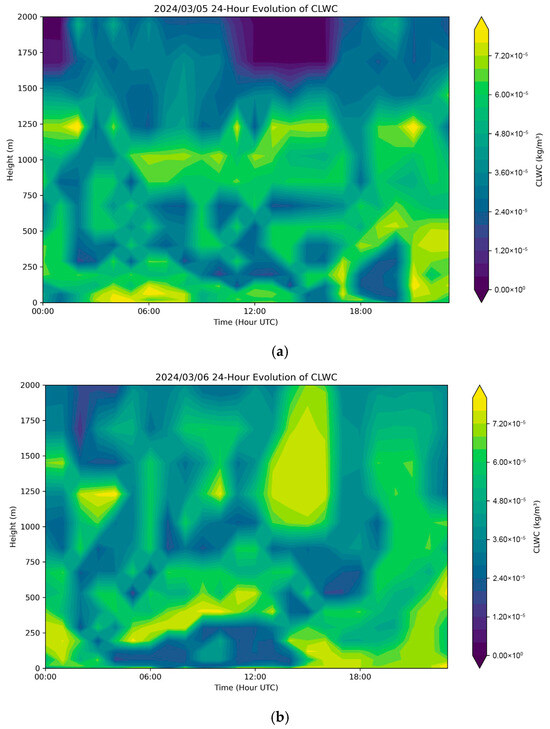

The radiometer-based CLWC data in the atmospheric boundary layer on 5–6 March 2024 are shown in Figure 4a,b, respectively. The event time is the crossover from 5 to 6 March at UTC, i.e., around 00 UTC on 6 March 2024. Starting at approximately 21 UTC on 5 March 2024, a layer of higher CLWC developed, extending up to ~500 m above-ground. This layer persisted up to about 02 UTC on 6 March 2024. The presence of this near-ground layer of higher CLWC values is consistent with foggy weather. From 03 UTC 6 March 2024 onwards, the higher CLWC layer was gradually “uplifted”, resulting in a lower CLWC value of <300 m. The higher CLWC layer “returned” to the ground near 15 UTC on 6 March 2024. These details are consistent with the conceptual model, in which the fog layer is uplifted during the day and subsequently returns at night. The continuous availability of radiometer-based CLWC enables the visualisation of liquid water evolution associated with the fog layer, which is not evident in the vertical water vapour profiles shown in Figure 3b.

Figure 4.

Time–height plot of radiometer-based CLWC for 5 March 2025 (a) and 6 March 2025 (b). Time is in UTC.

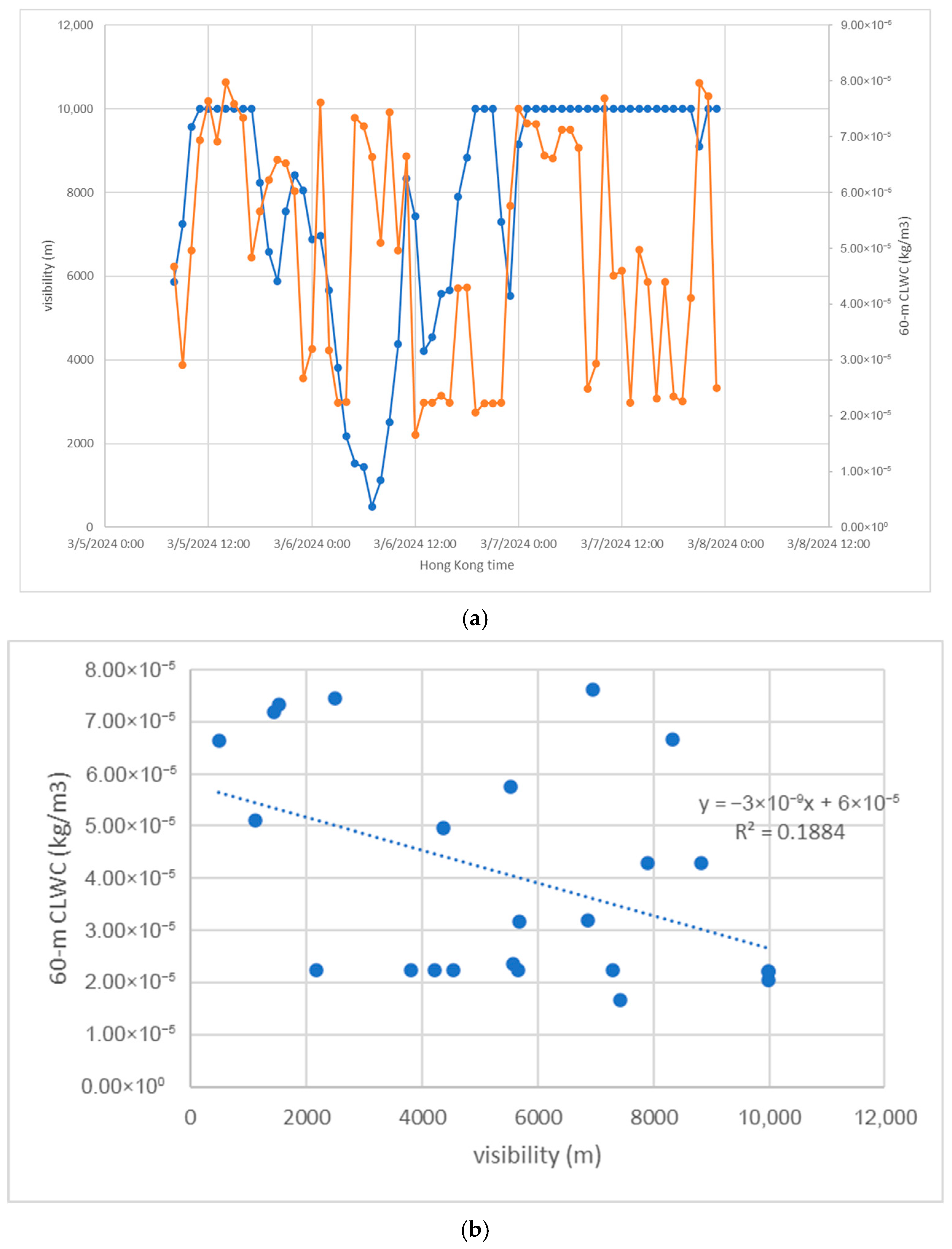

A visibility sensor was installed at Kai Tak (location shown in Figure 3a, and the visibility time series and CLWC at 60 m are shown in Figure 5a). On the evening of 5 March 2024, the visibility of Kai Tak decreased gradually, eventually reaching a minimum of ~200 m. As the visibility started to decrease, CLWC at 60 m measured by radiometer increased rapidly up to ~0.00008 kg/m3 around midnight on 6 March 2024. Although there were some CLWC fluctuations, they remained generally high. CLWC data may be useful for nowcasting the occurrence of fog-associated low visibility.

Figure 5.

(a) Time series of visibility at Kai Tak (blue curve, left-hand y-axis) and 60 m CLWC for King’s Park radiometer (orange, right-hand y-axis). Time is in HKT, which is UTC + 8. (b) Scatter plot of visibility (x-axis) and CLWC (y-axis), with best-fit straight line and squared correlation coefficient (R2).

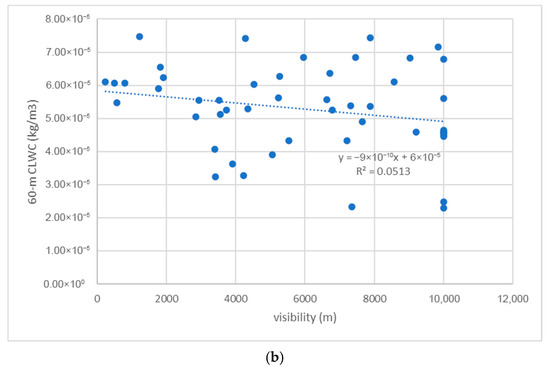

A quantitative study was made by plotting the visibility of Kai Tak against CLWC at 60 m for the entire day of 6 March 2024 local time, the period of fog-associated low-visibility (Figure 5b). The two quantities were observed to be inversely related, with a correlation coefficient of ~0.43. Given that the radiometer and visibility sensor were not collocated, this correlation coefficient was considered significant.

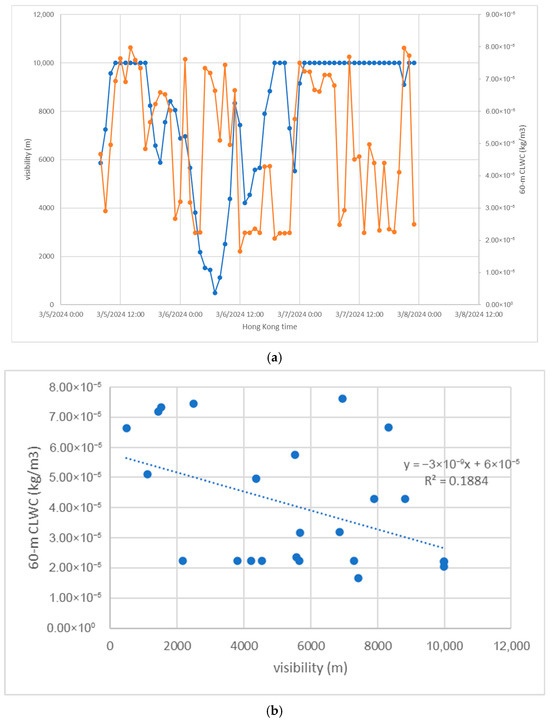

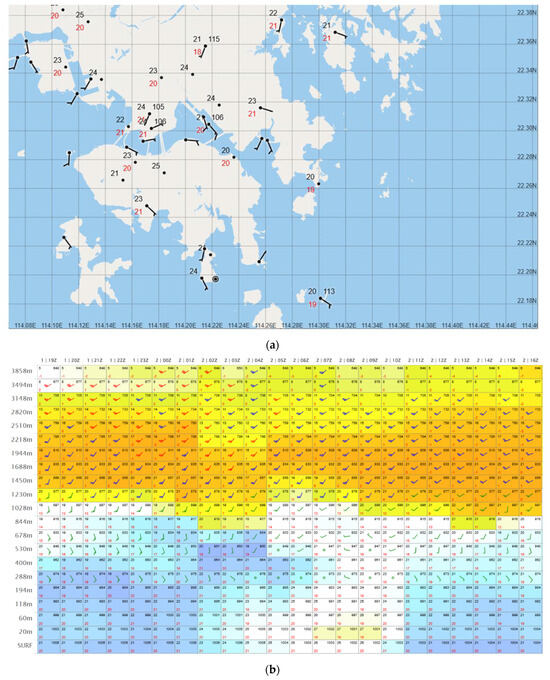

3.3.2. Fog Case of 2 March 2025

Another dense fog event occurred on the evening of 2 March 2025; such a dense fog event is rare in Hong Kong. Surface observations at the time of the event are shown in Figure 6a. Moderate southeasterly winds were recorded at Kai Tak, which facilitated the advection of sea fog into the coastal area. The change in wind direction from westerly to southeasterly also appears in the wind profiler data shown in Figure 6b. Following the change in wind direction, the lower atmosphere (below ~400 m) became moistened.

Figure 6.

(a) Surface data in Hong Kong at 10:00 UTC on 2 March 2025, showing a 10 min mean wind direction and wind speed (wind barb), temperature (black), and dew point (red). (b) Radiometer temperature, relative humidity (colour-shaded, with moist/dry represented as cool/warm colours), and vertical wind profile are from the radar wind profiler at Sham Shui Po. Time is in UTC.

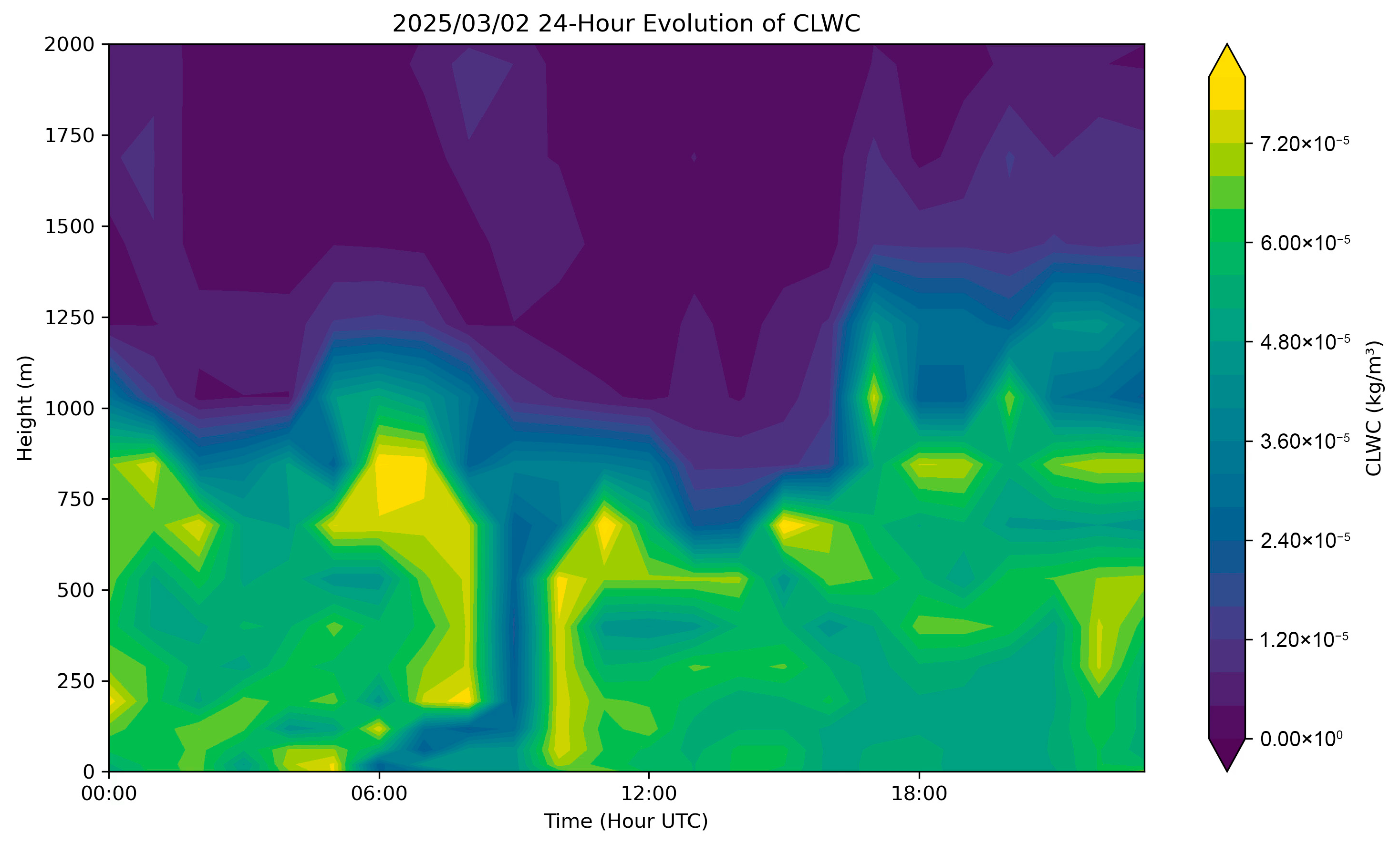

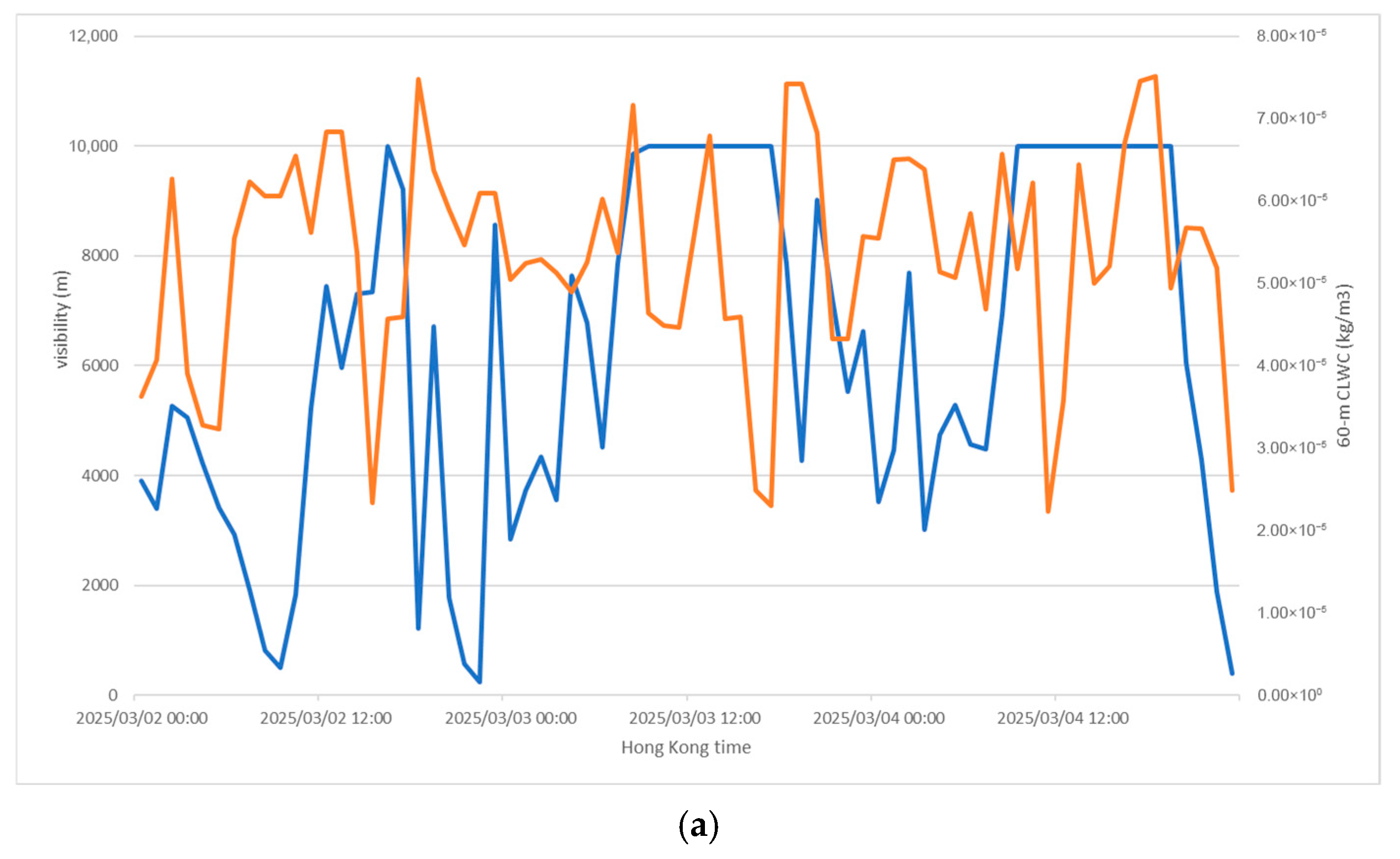

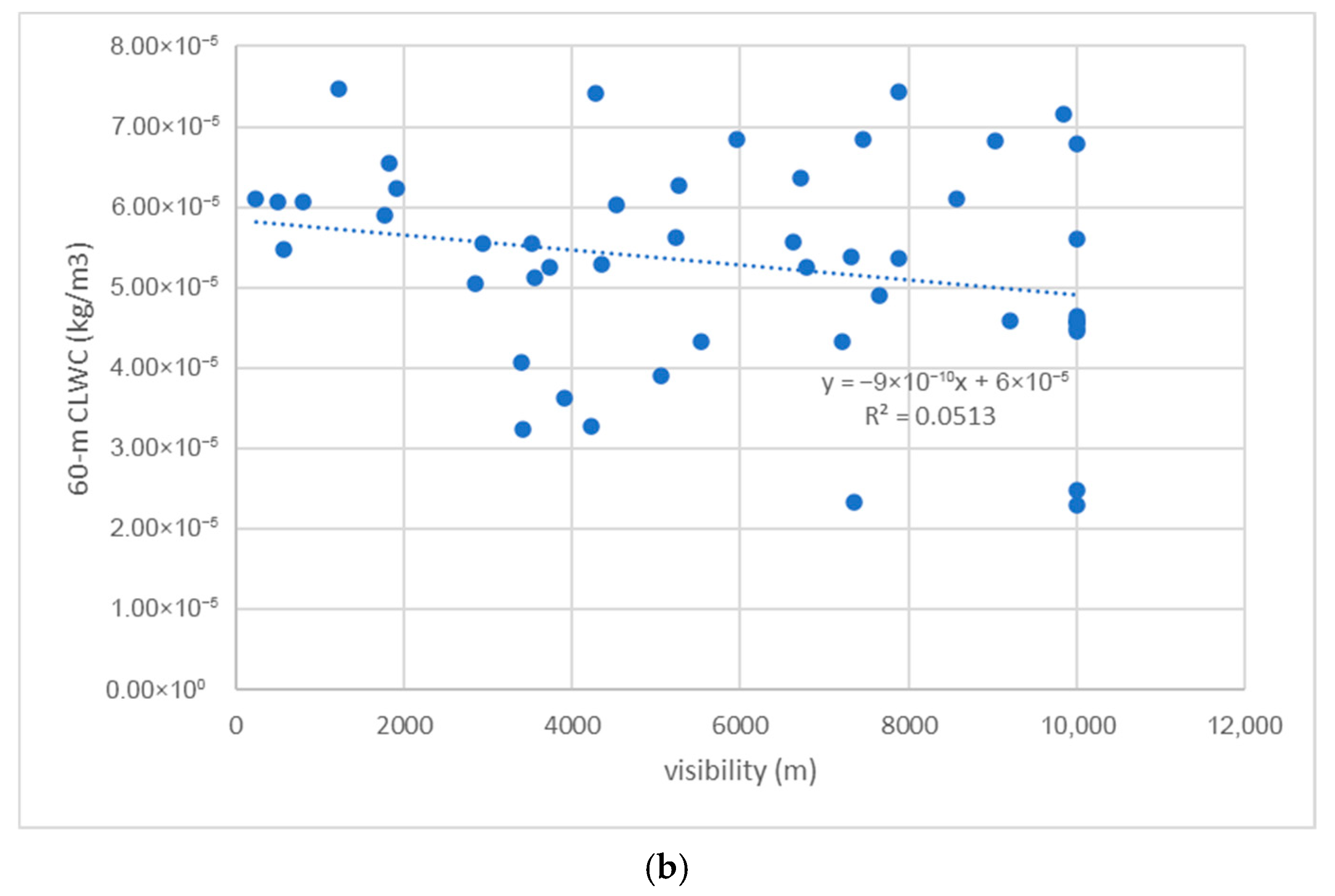

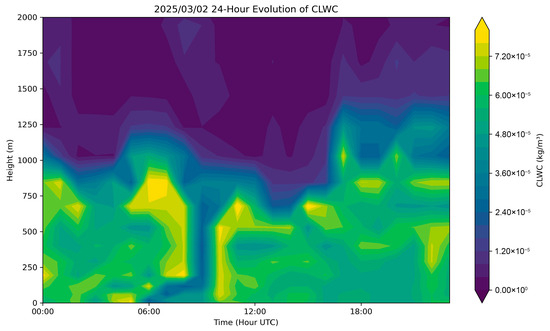

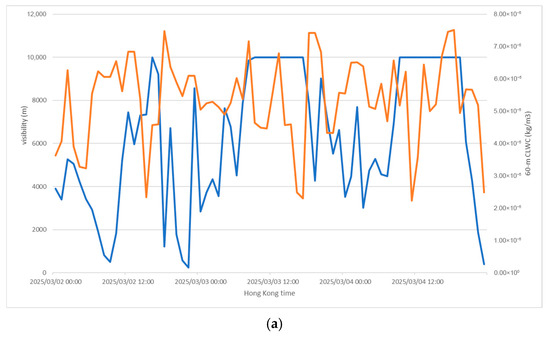

The occurrence of a higher CLWC of up to ~750 m at ~10 UTC on 2 March 2025 is shown in Figure 7. From the time series of CLWC at ~60 m, a rapid rise was observed between 16:00 and 18:00 local time on 2 March 2025 (Figure 8a), which may serve as a nowcast of the setting-in of dense fog. The Kai Tak visibility in this case dropped to a minimum of ~100 m (Figure 8a). The visibility for the entire event (2–3 March 2025) was plotted against the CLWC at 60 m (Figure 8b), revealing an inverse relationship between the two values. The correlation coefficient was 0.23, which is considered significant, given that the radiometer and visibility sensor are not collocated.

Figure 7.

Time–height plot of radiometer-based CLWC for 2 March 2025. Time in UTC.

Figure 8.

(a) Time series of visibility at Kai Tak (blue curve, left-hand y-axis) and 60 m CLWC for King’s Park radiometer (orange, right-hand y-axis). Time is in HKT, which is UTC + 8. (b) Scatter plot of visibility (x-axis) and CLWC (y-axis), with best-fit straight line and squared correlation coefficient (R2).

Another microwave radiometer operates in eastern Hong Kong and is frequently affected by low-visibility weather during spring. A visibility sensor is also installed. Prolonged measurements were conducted to determine whether a better correlation could be established between the CLWC at a particular height and visibility values.

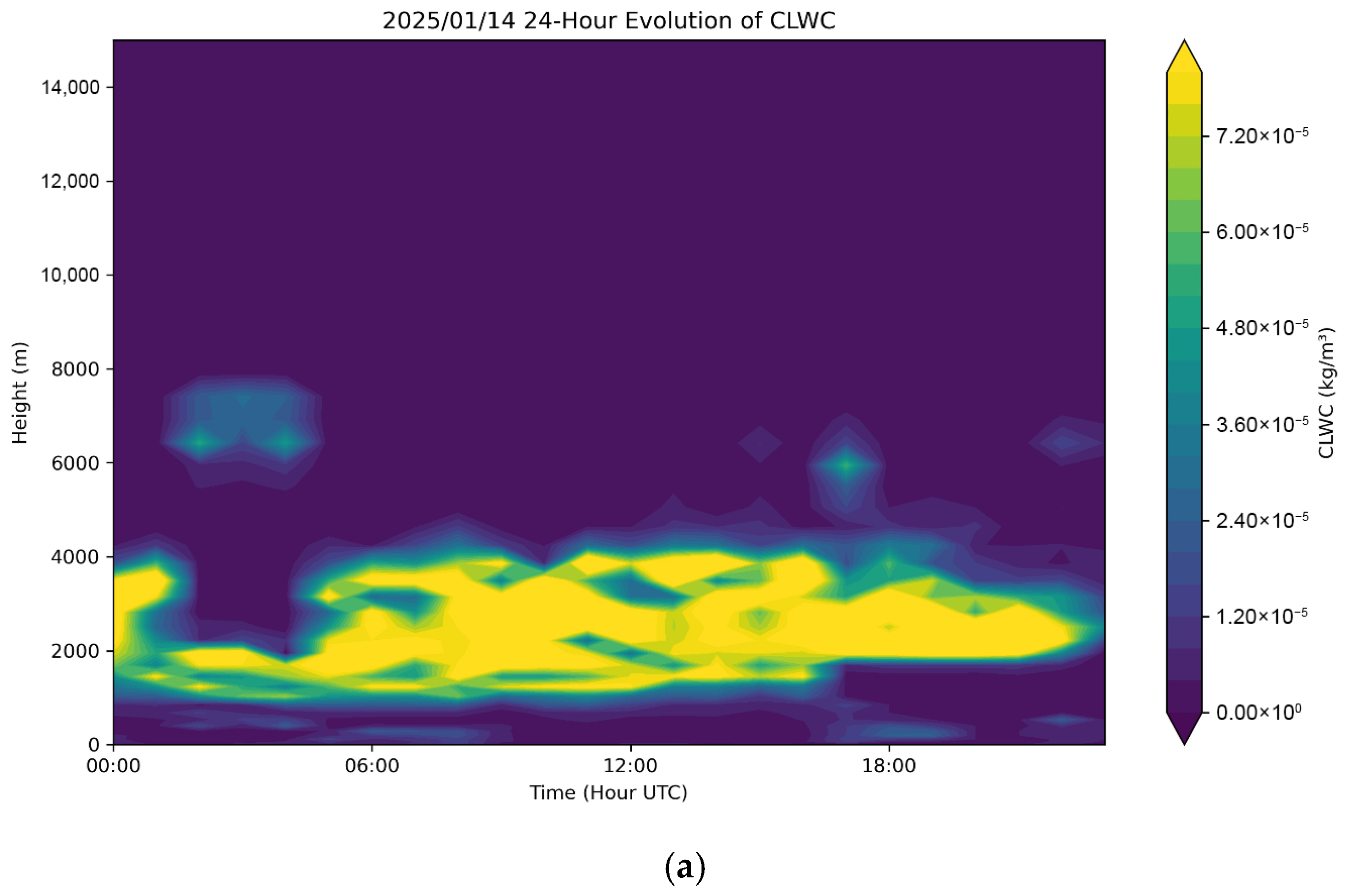

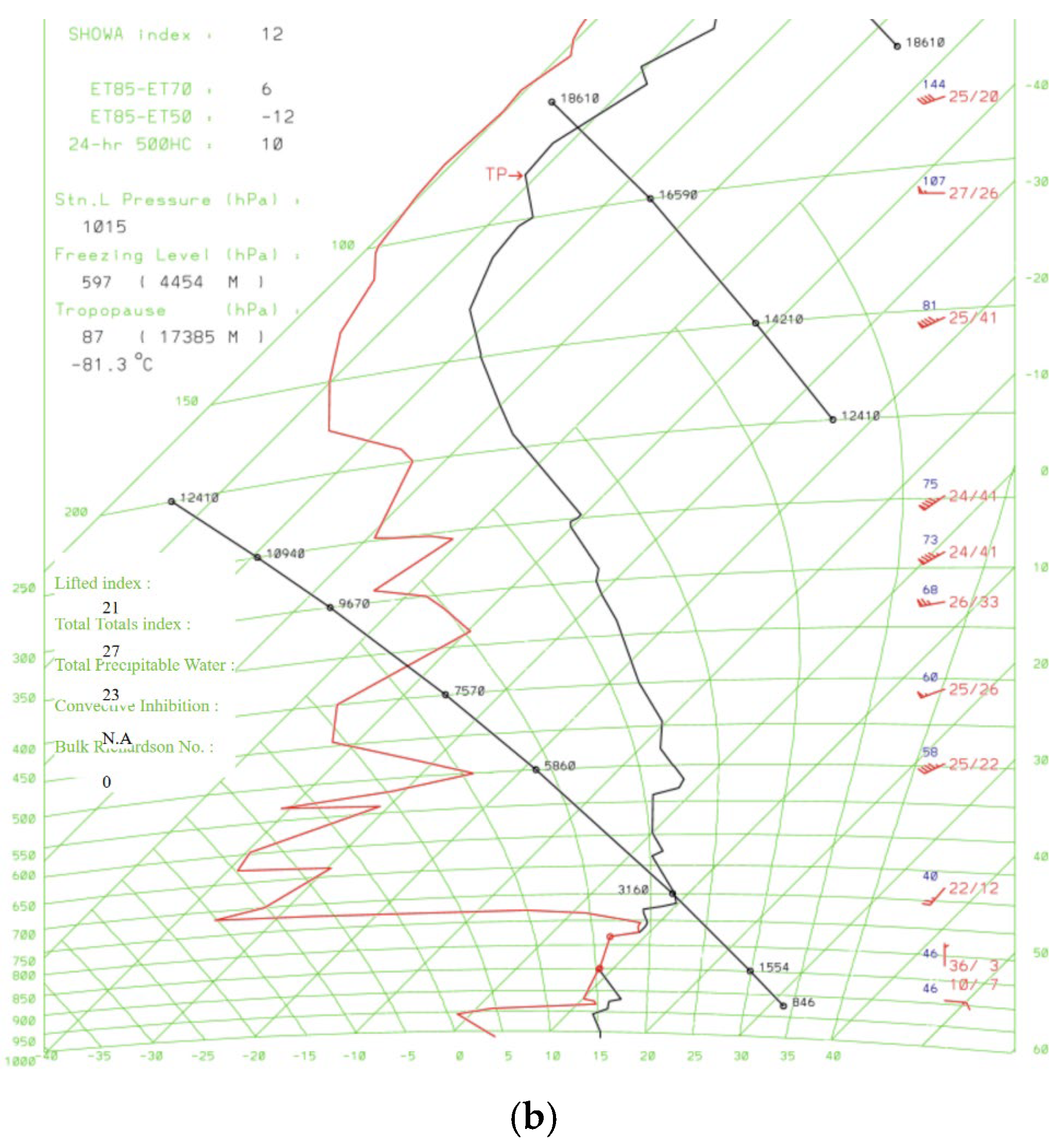

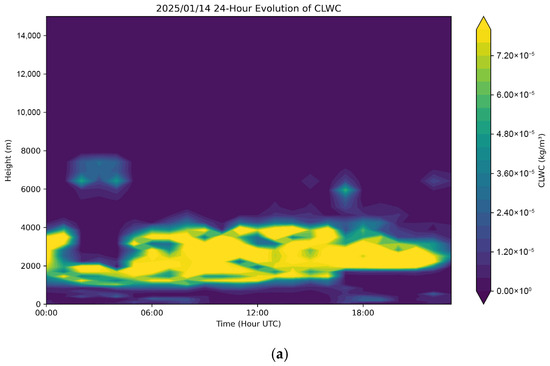

3.3.3. Liquid Water Cloud on 14 January 2025

Apart from the liquid water clouds near the surface, elevated liquid water clouds can exist in the atmospheric boundary layer. One such case was reported on 14 January 2025. There was an elevated layer of liquid water clouds between 1 and 4 km throughout the day. Synoptically, a northeast monsoon prevailed over southern China at the surface, and return flow (southerly flow originating from the northern part of the South China Sea) occurred at 850 hPa. The undercutting of the return flow by cooler air near the surface resulted in the persistence of a liquid water cloud.

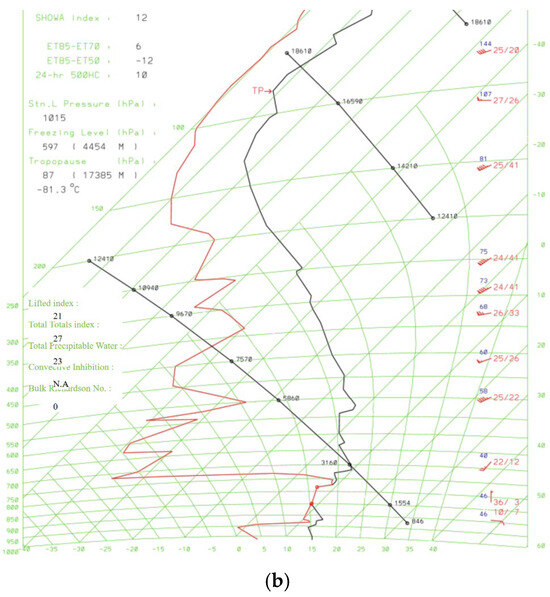

The tephigram for that day (Figure 9b) shows that the cloud layer appears well within the small dew-point depression between 900 and 700 hPa. CLWC profiles provide additional information on the persistence of cloud cover, are useful for monitoring the state of sky, and provide additional insight on short term nowcasting.

Figure 9.

(a) Time–height plot of radiometer-based CLWC, and (b) Tephigram of radiosonde ascent at King’s Park at 00 UTC on 14 January 2025. Time in UTC.

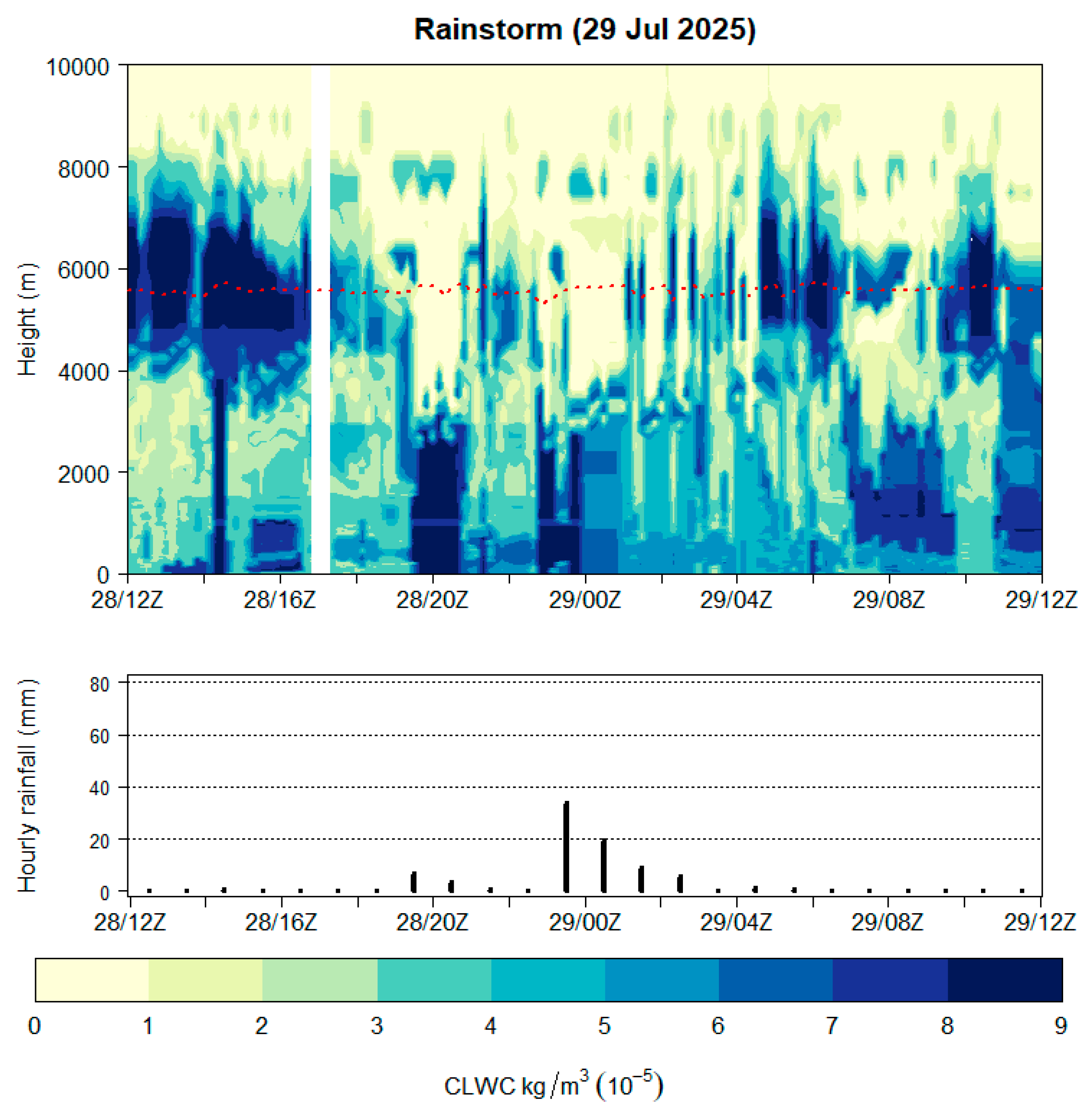

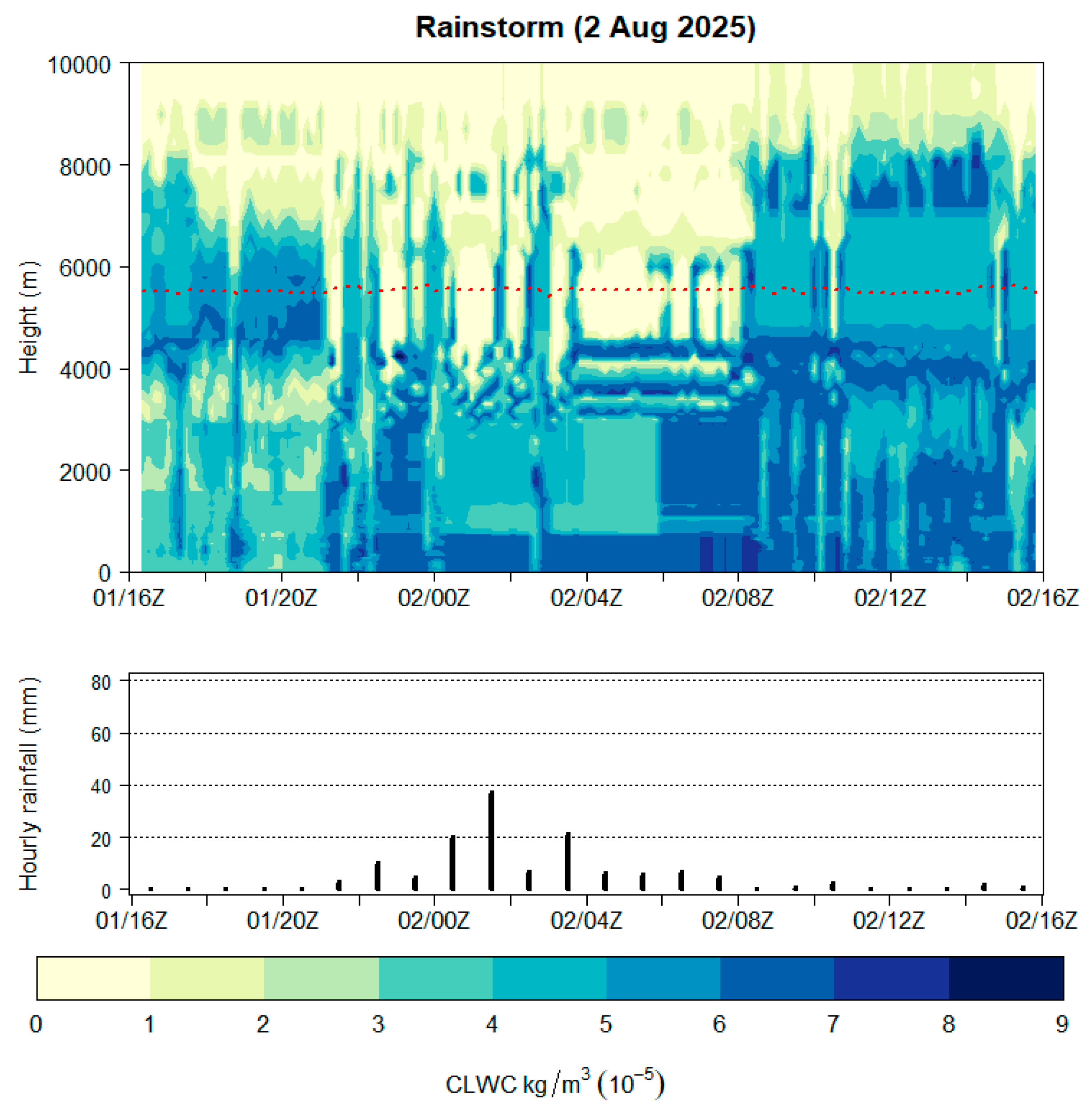

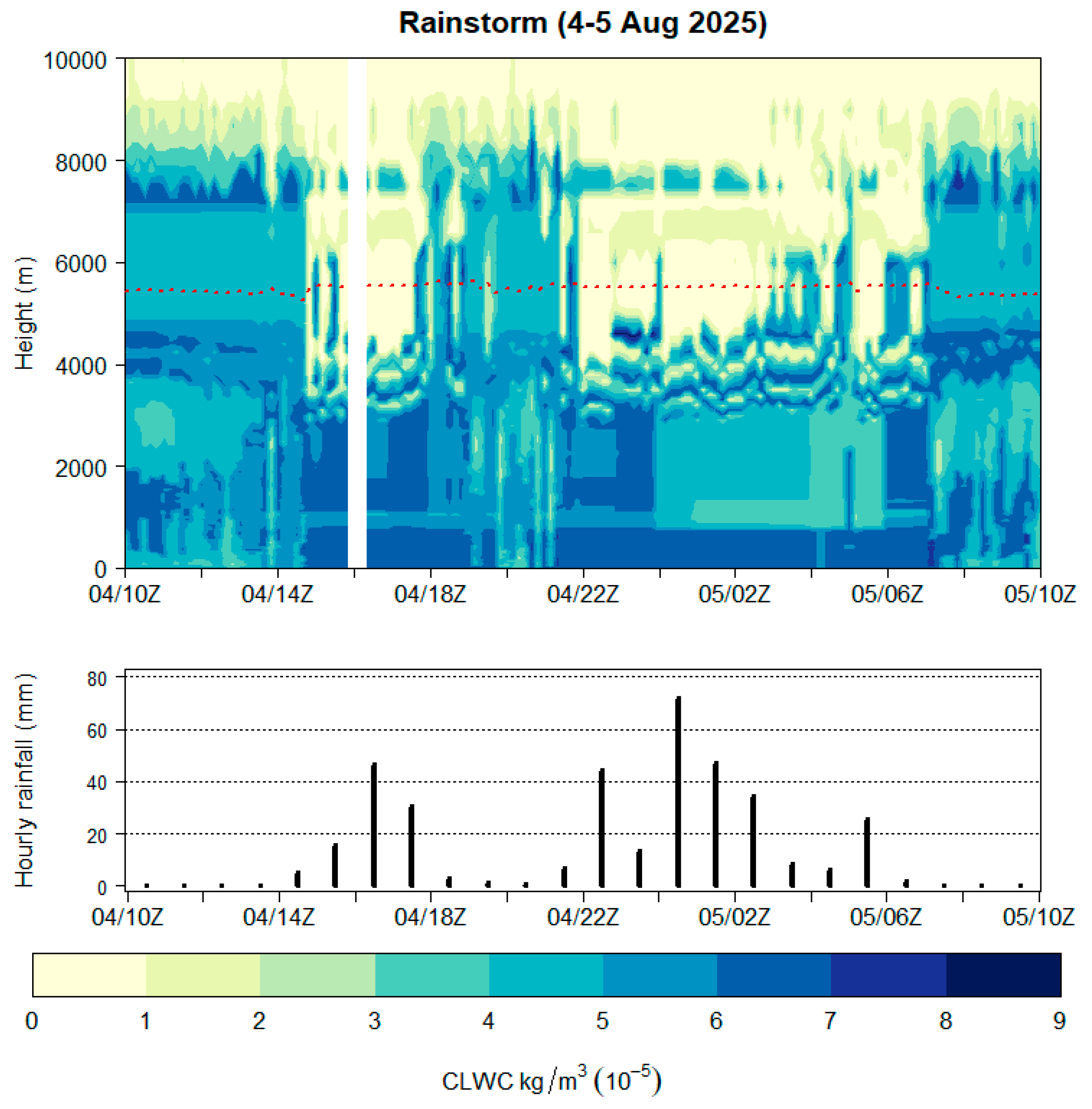

3.3.4. Supercooled Liquid Water in Rainstorms in July to August 2025

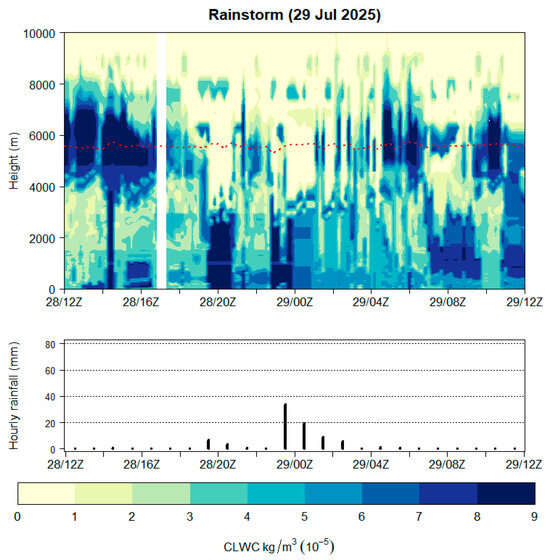

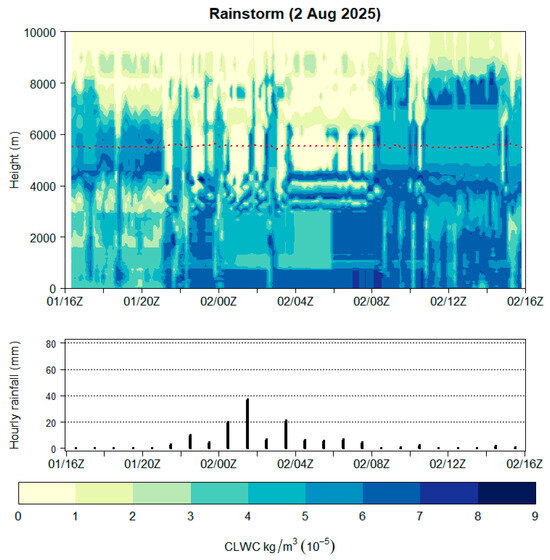

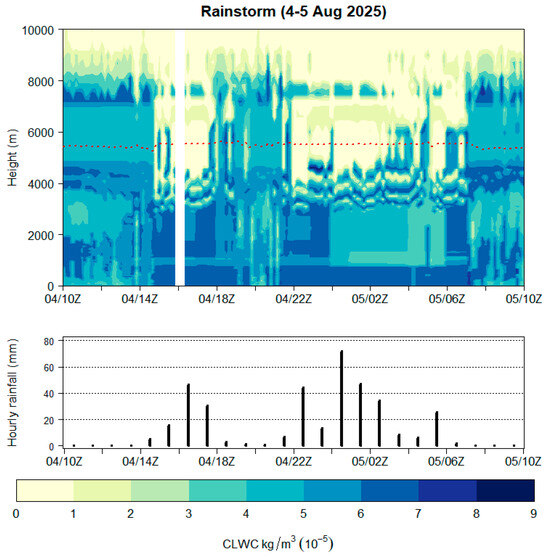

Several rainstorms occurred in Hong Kong in late July–August 2025, in which HKO issued the highest rainstorm warning signal, Black, defined by the widespread occurrence and persistence of hourly rainfall exceeding 70 mm across the territory. Radiometer-based CLWC offers a unique perspective on liquid water profiles during rainstorms.

The time–height contours of CLWC for the events of 29 July, 2 August, and 4–5 August 2025 are shown in Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12, respectively, together with the hourly rainfall recorded at the same station (the upper air ascent station of King’s Park in Hong Kong). From this limited number of rainstorm cases, it appears that the higher liquid water content mostly occurs in the lower to middle troposphere (below 3000–4000 m) during heavier rain. At other times, when Hong Kong is generally under cloud cover and the rainfall amount is much lower, higher liquid water content occurs mostly in the middle to upper troposphere (~4000–8000 m), although sometimes it may occur in the lower to middle troposphere at the same time. In such situations, supercooled liquid water (liquid water content below 0 °C) may occur. The red broken line in the figures denotes 0 °C, with generally subzero temperatures at higher altitudes. The occurrence of supercooled liquid water is an important observation for aviation applications, as it may lead to icing when aircraft fly over Hong Kong in enroute cruising phases.

Figure 10.

Time–height contour of radiometer-based CLWC at King’s Park during the rainstorm on 29 July 2025 (upper panel) and the hourly rainfall at King’s Park (lower panel). The red broken line in the upper panel represents the 0 °C isotherm.

Figure 11.

Time–height contour of radiometer-based CLWC at King’s Park during the rainstorm on 2 August 2025 (upper panel) and the hourly rainfall at King’s Park (lower panel). The red broken line in the upper panel represents the 0 °C isotherm.

Figure 12.

Time–height contour of radiometer-based CLWC at King’s Park during the rainstorms on 4–5 August 2025 (upper panel) and the hourly rainfall at King’s Park (lower panel). The red broken line in the upper panel represents the 0 °C isotherm.

A limitation that should be noted is the contamination of microwave signals from radiometers during heavy rain situations [17]. Although some advanced modules in radiometers can help improve the retrievals, it may inevitably affect the derivation of CLWC in the middle troposphere. Nonetheless, the existence of supercooled liquid water between heavy rain episodes was well observed in these rainstorm cases.

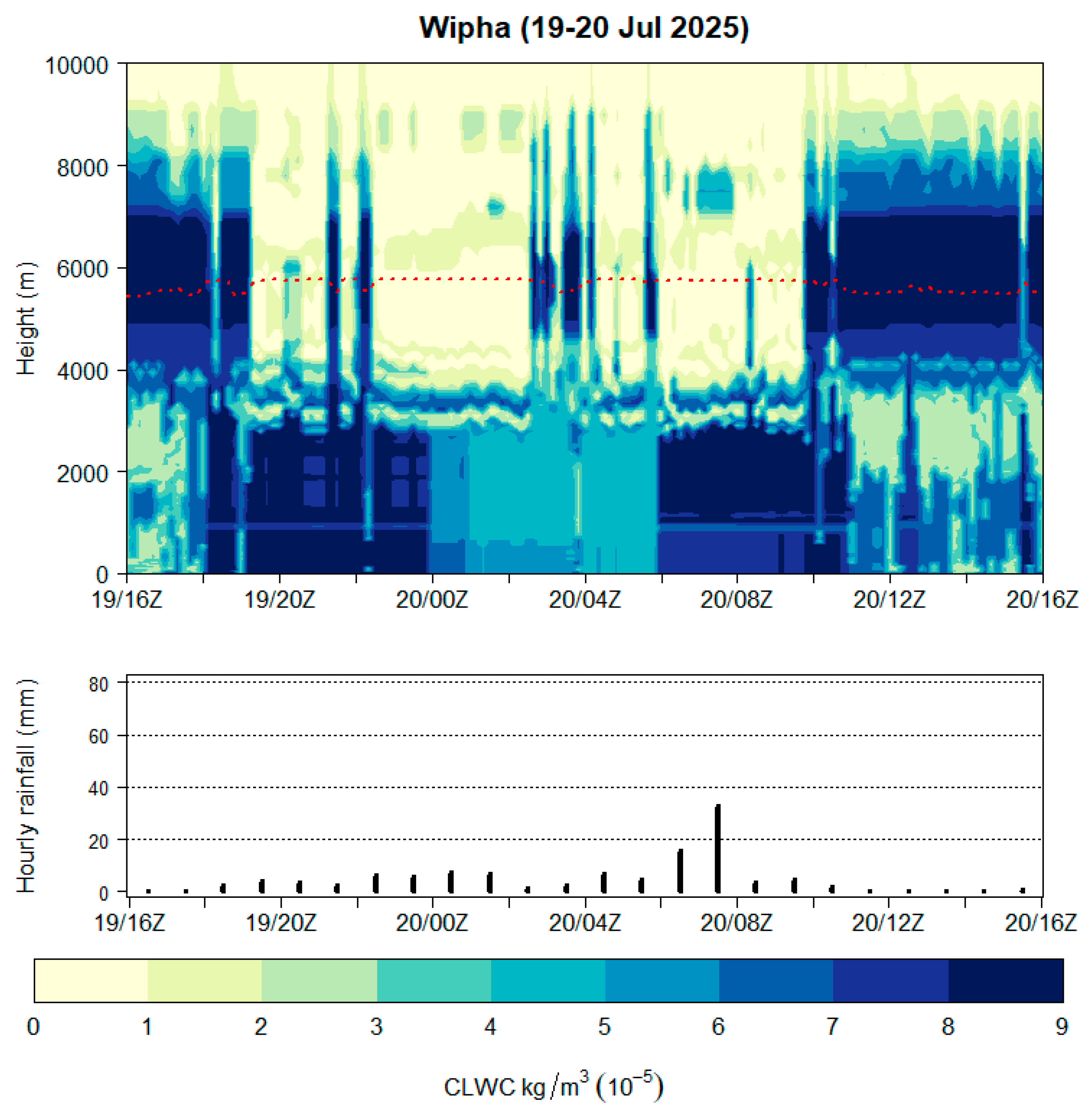

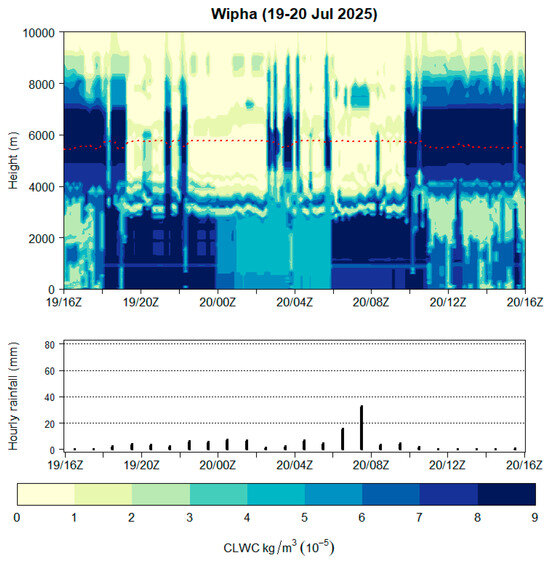

3.3.5. Observations for Typhoon Wipha in July 2025

From 19 to 20 July 2025, Typhoon Wipha directly affected Hong Kong [18]. Microwave radiosonde-based CLWC offers, for the first time, the ability to observe liquid water profiles during a typhoon. The CLWC time–height contour is shown in Figure 13, along with the hourly rainfall at King’s Park. Observations similar to the rainstorm cases described above were similar to when Hong Kong was affected by the outer rainband of Wipha. Under lighter rainfall, supercooled liquid water may have been present in the middle to upper troposphere. When rainfall was heavier—for example, when Hong Kong was affected by the eyewall and major rainbands of Wipha—supercooled liquid water in the middle to upper troposphere generally did not occur, with water mainly existing in a liquid state in the lower to middle troposphere. This observation is consistent with Wang’s analysis [19] of Typhoon Matmo over East China in 2014, where, in the updraft region of heavy rainfall associated with tropical cyclones, the process that dominates is the warm-rain process of auto conversion, accretion, and coalescence in the lower to middle troposphere. A limitation that should be noted is the contamination of microwave signals from radiometer during heavy rain situations [17], so further comparison with in situ radiosonde-based CLWC is pursued.

Figure 13.

Time–height contour of radiometer-based CLWC at King’s Park during typhoon Wipha from 19 to 20 July 2025 (upper panel) and the hourly rainfall at King’s Park (lower panel). The red broken line in the upper panel represents the 0 °C isotherm.

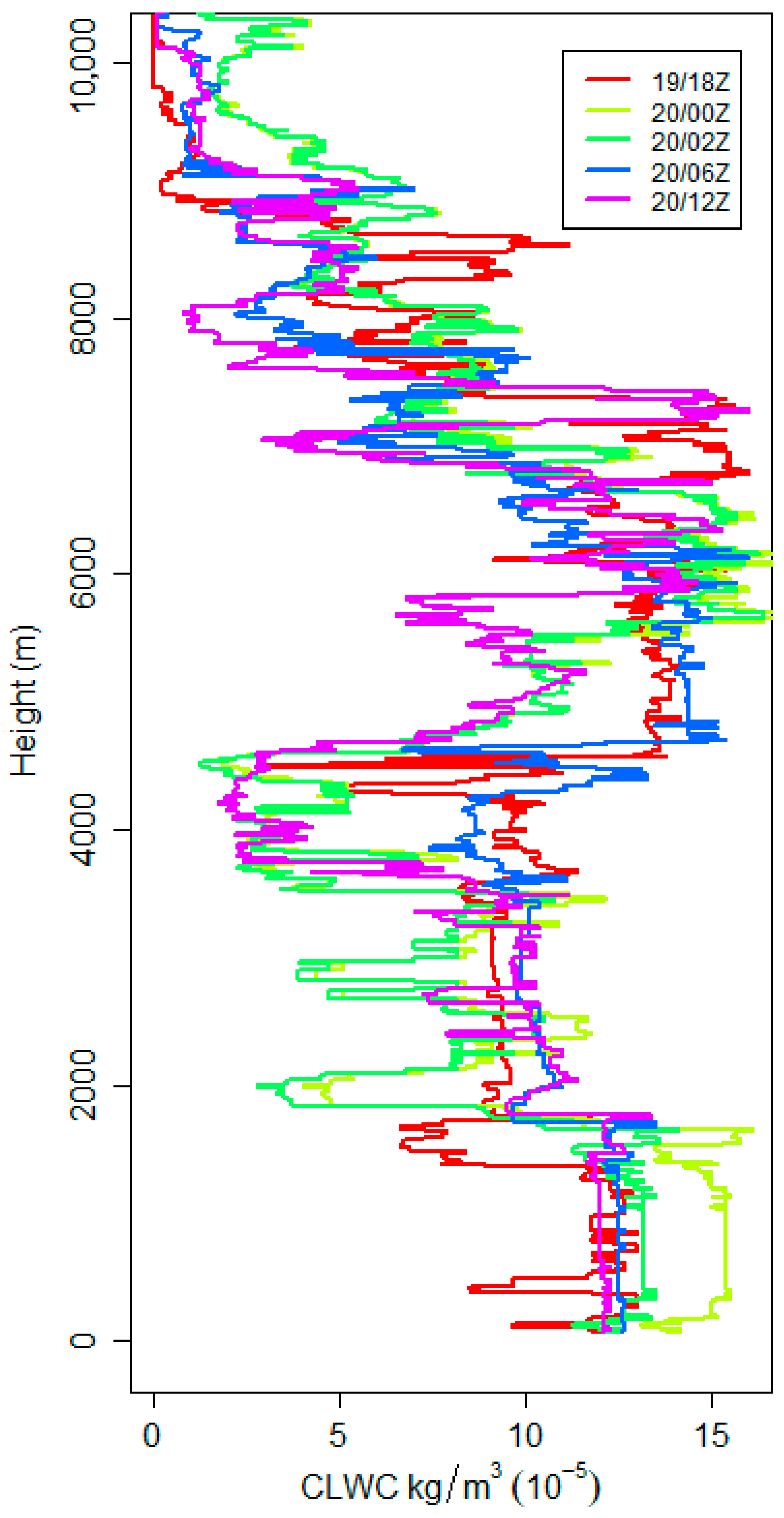

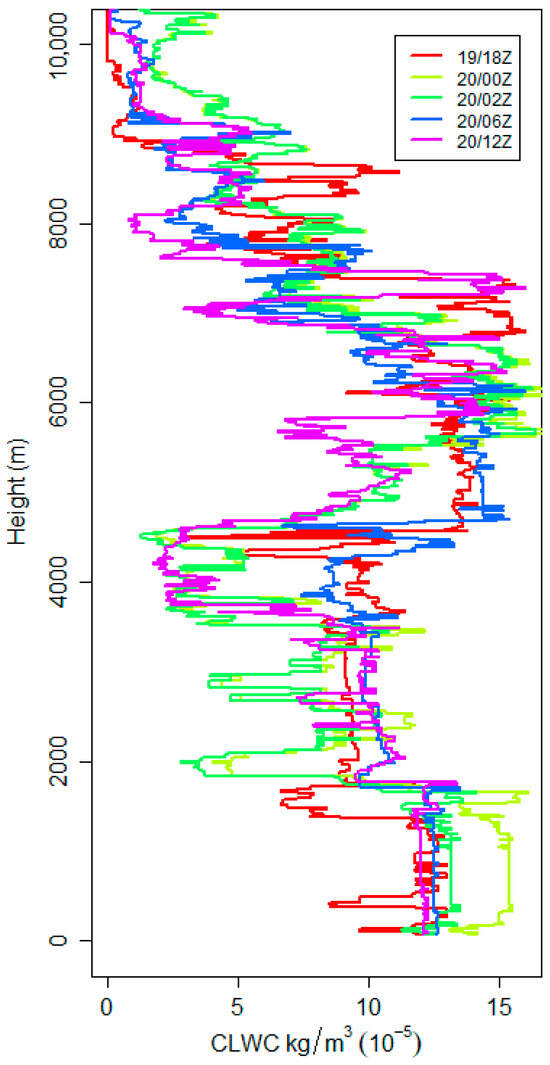

The radiosonde-based CLWC profiles are shown in Figure 14 for the times when radiosondes were launched during Typhoon Wipha. Note that the launch schedule was enhanced due to the passage of Typhoon Wipha. The CLWC derivation using radiosonde data was similar to that of the microwave radiometer based on the machine learning method described in Section 2. Although the radiosonde-based CLWC profiles generally had higher liquid water content in the middle to upper troposphere (in the order of 10 to 15 × 10−5 kg/m3) than the radiometer-based data (in the order of 7 to 9 × 10−5 kg/m3), the trend in CLWC distribution in the lower/middle troposphere and middle/upper troposphere was similar in both datasets. It is noted that the drop of CLWC around 4000 m was evident, showing the warm-rain process described above. However, radiosonde-based CLWC showed the increase in the CLWC from 4500 m to 6000 m, indicating supercooled liquid water may still be present within the 0 °C isotherm slightly below 6000 m.

Figure 14.

Vertical profile of CLWC based on radiosonde data at King’s Park during typhoon Wipha. Times are in UTC.

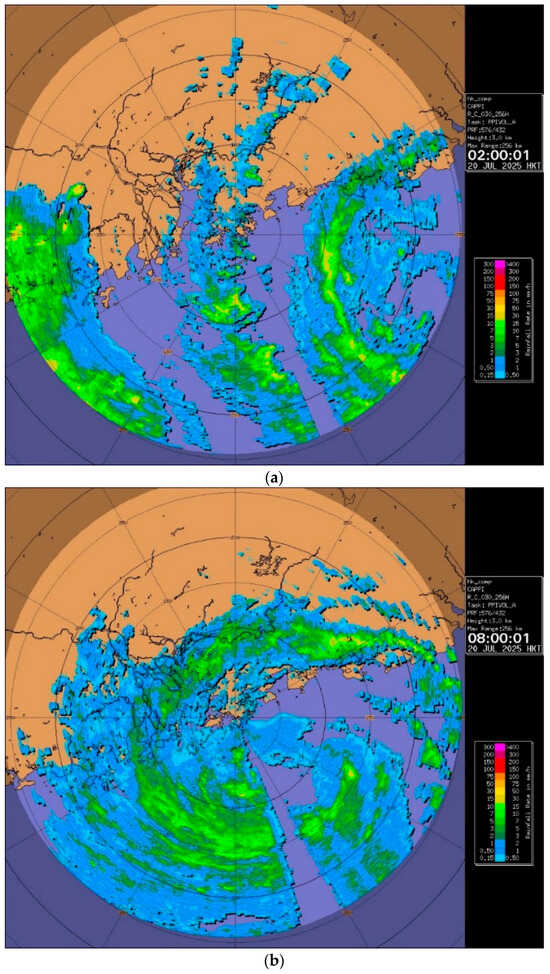

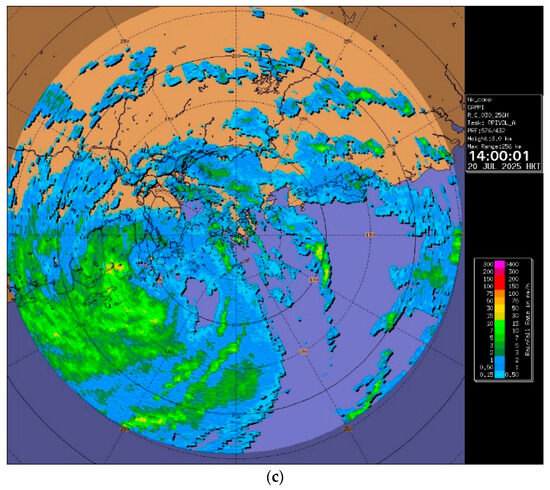

For a better appreciation of the Wipha rainbands affecting Hong Kong at various times, weather radar images at 18 UTC on 19 July 2025, as well as 00 and 06 UTC on 20 July 2025, are shown in Figure 15. Initially, Hong Kong was affected by the outer Wipha rainband, with a lower amount of rainfall. Supercooled liquid water was observed in the middle and upper troposphere (Figure 13). In the latter two instances, Hong Kong was primarily affected by the Wipha eyewall, and supercooled liquid water was not present at these heights (Figure 13).

Figure 15.

Weather radar imagery at 3 km altitude over Hong Kong during typhoon Wipha at (a) 18 UTC, 19 July 2025; (b) 00 UTC, 20 July 2025; and (c) 06 UTC, 20 July 2025.

4. Conclusions

This paper investigated the operational applicability of cloud liquid water content (CLWC) derived from radiometers with various approaches and illustrated its applicability via the investigation of different weather events in Hong Kong. Firstly, radiometer-based CLWC was compared with radiosonde-based CLWC and the two were found to be generally consistent, with a small root-mean-square difference. Secondly, the liquid-water path (LWP) data for January to March 2025 derived from the radiometer data was compared with a LWP based on ERA5, and it was found that the two datasets were closely correlated, with a correlation coefficient of approximately 0.3.

Then, the operational feasibility of radiometer-based CLWC was studied under four weather conditions: two dense fog conditions, liquid water clouds in the lower troposphere, supercooled liquid water in rainstorms, and typhoons. In the fog cases, it was found that visibility and CLWC were inversely related; therefore, increases in CLWC may be useful for the nowcasting of visibility and fog occurrence. Although no independent measurements were available to verify the accuracy of radiometer-based CLWC, the obtained profiles provided additional insight into the weather events, complementing the existing water vapour profiles. CLWC was also observed for the first time during rainstorms and typhoons in Hong Kong. In both weather events, supercooled liquid water was found in the middle to upper troposphere when Hong Kong in between episodes of heavy rain, for example, when the major rain area of a rainstorm was approaching or when the city was affected by the outer rainband of a typhoon. When heavy rain occurred, supercooled liquid water was absent. This may have been due to the limitation of the microwave attenuation of the radiometer during heavy rain episodes. However, further comparison with radiosonde-based CLWC showed that during the warm-rain processes, the supercooled liquid water amount indeed decreased in the middle troposphere, but some supercooled liquid water may still be present higher up in the atmosphere. This illustrates one of the limitations of radiometer-based CLWC.

Radiometer-based CLWC has only recently begun to be used for weather monitoring in HKO. Radiometer-based CLWC derived from machine learning models is found to be consistent with radiosonde-based CLWC but may derive a smaller CLWC and exhibit attenuation issues during heavy rain situations. Nonetheless, its derived trends and rapid updates can enhance the weather monitoring process and improve our understanding of the structure of atmospheric cloud water. Future work will report further observations under a wider range of weather conditions. The findings of the present study may stimulate researchers to further examine cloud water phases during heavy rain and typhoons.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.W.C.; Data curation, P.C. and C.K.H.; Formal analysis, P.W.C. and Y.Y.L.; Resources, P.C.; Software, A.A. and Y.Z.; Visualisation, C.K.H.; Writing—original draft, P.W.C.; Writing—review and editing, Y.Y.L.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alishouse, J.C.; Snider, J.B.; Westwater, E.R.; Swift, C.T.; Ruf, C.S.; Snyder, S.A.; Vongsathorn, J.; Ferraro, R.R. Determination of cloud liquid water content using the SSM/I. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1990, 28, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grody, N. Remote sensing of atmospheric water content from satellites using microwave radiometry. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1976, 24, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, T.J.; Stephens, G.L.; Vonder Haar, T.H.; Jackson, D.L. A physical retrieval of cloud liquid water over the global oceans using Special Sensor Microwave/Imager (SSM/I) observations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1993, 98, 18471–18488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, F.; Grody, N.C. Retrieval of cloud liquid water using the special sensor microwave imager (SSM/I). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1994, 99, 25535–25551. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, F.; Grody, N.C.; Ferraro, R.; Basist, A.; Forsyth, D. Cloud liquid water climatology from the Special Sensor Microwave/Imager. J. Clim. 1997, 10, 1086–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimnuan, P.; Janjai, S.; Nunez, M.; Pratummasoot, N.; Buntoung, S.; Charuchittipan, D.; Chanyatham, T.; Chantraket, P.; Tantiplubthong, N. Determination of effective droplet radius and optical depth of liquid water clouds over a tropical site in northern Thailand using passive microwave soundings, aircraft measurements and spectral irradiance data. J. Atmos. Sol.-Terr. Phys. 2017, 161, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Ma, Y.; Cao, D.; Sun, F.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Q. Application of Ground-Based Microwave Radiometer to Optimize the Estimation Method of Cloud Liquid Water on the Tibetan Plateau. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2025. Available online: http://www.iapjournals.ac.cn/aas/article/doi/10.1007/s00376-025-4416-7 (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Michael, B.; Rahman, K.; Addasi, O.; Ramamurthy, P. On the Applicability of Ground-Based Microwave Radiometers for Urban Boundary Layer Research. Sensors 2024, 24, 2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, P.W. Performance and application of a multi-wavelength, ground-based microwave radiometer in intense convective weather. Meteorol. Z. 2009, 18, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Whereabouts of Radiosondes After Lifting off. Available online: https://www.hko.gov.hk/en/education/meteorological-instruments/automatic-weather-stations/00709-The-whereabouts-of-radiosondes-after-lifting-off.html (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- HATPRO Operational Manual, 2023. Available online: https://www.radiometer-physics.de/products/microwave-remote-sensing-instruments/radiometers/humidity-and-temperature-profilers/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Amaireh, A.; Zhang, Y.; Chan, P.W.; Zrnic, D. A novel approach for improving cloud liquid water content profiling with machine learning. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaireh, A.; Al-Zoubi, A.S.; Dib, N.I. A new hybrid optimization technique based on antlion and grasshopper optimization algorithms. Evol. Intell. 2023, 16, 1383–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Meteorological Society Glossary: Liquid Water Path. Available online: https://glossary.ametsoc.org/wiki/Liquid_water_path (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Chan, P.W.; Li, Q.S. Case studies of springtime fog in Hong Kong. Weather 2019, 74, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- News Report of the Impact of Dense Fog in Hong Kong on 6 March 2025. Available online: https://www.hk01.com/%E7%86%B1%E7%88%86%E8%A9%B1%E9%A1%8C/997661/%E7%9B%B8%E5%B0%8D%E6%BF%95%E5%BA%A6100-%E5%B0%87%E8%BB%8D%E6%BE%B3%E5%8D%97%E8%B1%90%E5%BB%A3%E5%A0%B43%E9%83%A8%F0%A8%8B%A2%E5%85%A8%E6%95%85%E9%9A%9C%E4%BD%8F%E6%88%B6%E5%91%BB%E6%85%98-%E7%89%A9%E6%A5%AD%E7%AE%A1%E7%90%86%E5%92%81%E8%AC%9B (accessed on 8 October 2025). Only available in Chinese.

- Foth, A.; Lochmann, M.; Saavedra Garfias, P.; Kalesse-Los, H. Determination of low-level temperature profiles from microwave radiometer observations during rain. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2024, 17, 7169–7181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Weather of July 2025—A Rainy July with the Strike of Wipha. Available online: https://www.hko.gov.hk/en/wxinfo/pastwx/mws2025/mws202507.htm (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Wang, M.; Zhao, K.; Lee, W.C.; Zhang, F. Microphysical and kinematic structure of convective-scale elements in the inner rainband of Typhoon Matmo (2014) after landfall. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2018, 123, 6549–6564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).