From Waste to Resource: Valorization of Yellow Ginkgo Leaves as a Source of Pharmacologically Relevant Biflavonoids

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Instruments

2.2. Leaves Collection and Storage

2.3. Determination of Pigment Content

2.4. Determination of Polyphenolic Compounds

2.4.1. Total Polyphenols

2.4.2. Total Flavonoids

2.4.3. Total Phenolic Acids

2.4.4. Biflavonoid Profiling

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Pigment Content

3.2. Polyphenolic Compounds Content

3.2.1. Total Polyphenols, Flavonoids and Phenolic Acids

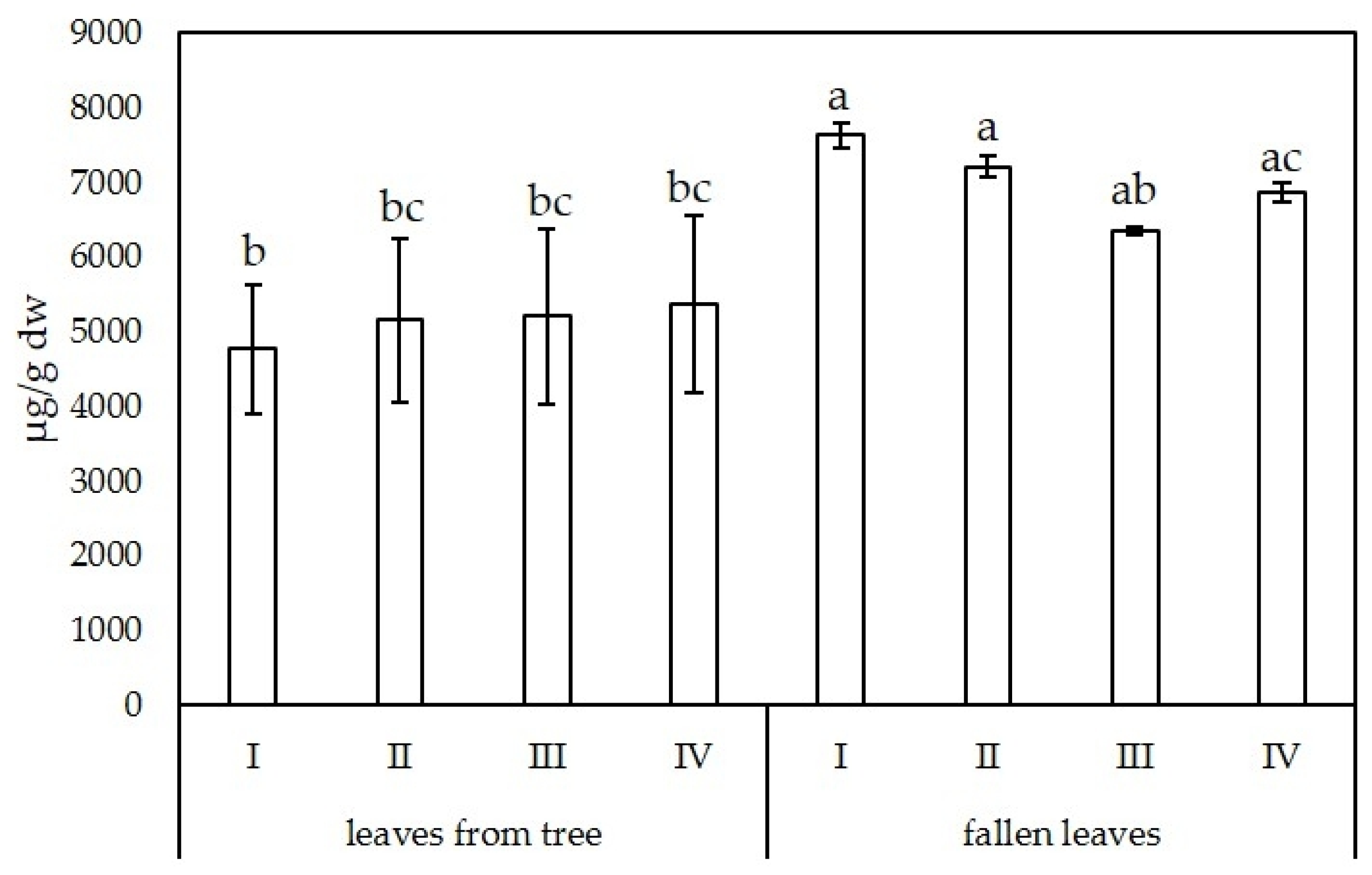

3.2.2. Biflavonoids

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, X.; Yang, F.; Huang, X. Proceedings of Chemistry, Pharmacology, Pharmacokinetics and Synthesis of Biflavonoids. Molecules 2021, 26, 6088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabogal-Guáqueta, A.M.; Carrillo-Hormaza, L.; Osorio, E.; Cardona-Gómez, G.P. Effects of Biflavonoids from Garcinia Madruno on a Triple Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 129, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatlı Çankaya, İ.İ.; Devkota, H.P.; Zengin, G.; Šamec, D. Neuroprotective Potential of Biflavone Ginkgetin: A Review. Life 2023, 13, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, A.; Chi, E.Y. Biflavonoids as Potential Small Molecule Therapeutics for Alzheimer’s Disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2015, 863, 55–77. [Google Scholar]

- Jurčević Šangut, I.; Šarkanj, B.; Karalija, E.; Šamec, D. A Comparative Analysis of Radical Scavenging, Antifungal and Enzyme Inhibition Activity of 3′-8″-Biflavones and Their Monomeric Subunits. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, F.; Zhang, S.; Chen, D.; Tan, J.; Kuang, M.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, G.; Xu, K.; Zou, Z.; Tan, G. Biflavonoids from Selaginella Doederleinii as Potential Antitumor Agents for Intervention of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Molecules 2021, 26, 5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napoli, E.; Siracusa, L.; Ruberto, G.; Carrubba, A.; Lazzara, S.; Speciale, A.; Cimino, F.; Saija, A.; Cristani, M. Phytochemical Profiles, Phototoxic and Antioxidant Properties of Eleven Hypericum Species—A Comparative Study. Phytochemistry 2018, 152, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvedec, B.; Jurčević Šangut, I.; Macanović, A.; Karalija, E.; Šamec, D. Biflavonoid Profiling of Juniperus Species: The Influence of Plant Part and Growing Location. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovač Tomas, M.; Jurčević, I.; Šamec, D. Tissue-Specific Profiling of Biflavonoids in Ginkgo (Ginkgo Biloba L.). Plants 2022, 12, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.-G.; Lu, X.; Gao, W.; Li, P.; Yang, H. Structure, Synthesis, Biosynthesis, and Activity of the Characteristic Compounds from Ginkgo Biloba L. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2022, 39, 474–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva Pinto, M.; Kwon, Y.-I.; Apostolidis, E.; Lajolo, F.M.; Genovese, M.I.; Shetty, K. Potential of Ginkgo Biloba L. Leaves in the Management of Hyperglycemia and Hypertension Using in Vitro Models. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 6599–6609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobus-Cisowska, J.; Dziedziński, M.; Szczepaniak, O.; Kusek, W.; Kmiecik, D.; Ligaj, M.; Telichowska, A.; Byczkiewicz, S.; Szulc, P.; Szwajgier, D. Phytocomponents and Evaluation of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibition by Ginkgo Biloba L. Leaves Extract Depending on Vegetation Period. CyTA-J. Food 2020, 18, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurčević Šangut, I.; Šola, I.; Šamec, D. Neuroprotective, Anti-Hyperpigmentation, and Anti-Diabetic Effects and Bioaccessibility of Flavonoids in Ginkgo Leaf Infusions from Green and Yellow Leaves. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-J.; Kim, M.-M. Flavonoids in Ginkgo Biloba Fallen Leaves Induce Apoptosis through Modulation of P53 Activation in Melanoma Cells. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 33, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Liu, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M. Supercritical CO2 Fluid Extraction, Physicochemical Properties, Antioxidant Activities and Hypoglycemic Activity of Polysaccharides Derived from Fallen Ginkgo Leaves. Food Biosci. 2021, 42, 101153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurčević Šangut, I.; Šamec, D. Seasonal Variation of Polyphenols and Pigments in Ginkgo (Ginkgo Biloba L.) Leaves: Focus on 3′,8″-Biflavones. Plants 2024, 13, 3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horbowicz, M.; Wiczkowski, W.; Góraj-Koniarska, J.; Miyamoto, K.; Ueda, J.; Saniewski, M. Effect of Methyl Jasmonate on the Terpene Trilactones, Flavonoids, and Phenolic Acids in Ginkgo Biloba L. Leaves: Relevance to Leaf Senescence. Molecules 2021, 26, 4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-E.; Park, J.; Chung, J. Adsorption of Pb(II) and Cu(II) by Ginkgo-Leaf-Derived Biochar Produced under Various Carbonization Temperatures and Times. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S. Advances in the Chemical Constituents and Chemical Analysis of Ginkgo Biloba Leaf, Extract, and Phytopharmaceuticals. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2021, 193, 113704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Buschmann, C. Chlorophylls and Carotenoids: Measurement and Characterization by UV-VIS Spectroscopy. Curr. Protoc. Food Anal. Chem. 2001, 1, F4.3.1–F4.3.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhishen, J.; Mengcheng, T.; Jianming, W. The Determination of Flavonoid Contents in Mulberry and Their Scavenging Effects on Superoxide Radicals. Food Chem. 1999, 64, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Rao, B.; Tare, A.B. Comparative Analysis of the Spectrophotometry Based Total Phenolic Acid Estimation Methods. J. Anal. Chem. 2017, 72, 972–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. Past: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.S.; Chen, G.X.; Yuan, Z.Y. Photosynthetic Decline in Ginkgo Leaves during Natural Senescence. Pakistan J. Bot. 2013, 45, 1537–1540. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Guo, J.; Wang, T.; Cao, F.; Wang, G. Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analyses of Mutant Yellow Leaves Provide Insights into Pigment Synthesis and Metabolism in Ginkgo Biloba. BMC Genomics 2020, 21, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Okazawa, A.; Itoh, Y.; Fukusaki, E.I.; Kobayashi, A. Expression of Chlorophyllase Is Not Induced during Autumnal Yellowing in Ginkgo Biloba. Z. Naturforsch.—Sect. C J. Biosci. 2004, 59, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, P.; Song, M.; Li, D.; Sheng, Q.; Cao, F.; Zhu, Z. Leaf Color Changes and Photosynthetic Characteristics of Five Superior Late-Deciduous Ginkgo Biloba Cultivars. HortScience 2021, 56, 1416–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, L.; He, Z.; Lu, Z.; Cui, J.; Xu, N.; Jin, B.; Wang, L. Physiological and Transcriptomic Changes During Autumn Coloration and Senescence in Ginkgo Biloba Leaves. Hortic. Plant J. 2020, 6, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Hu, Y.; Jing, W.; Wang, Y.; Gao, X.; Guo, Q. Cytological, Physiological and Genotyping-by-Sequencing Analysis Revealing Dynamic Variation of Leaf Color in Ginkgo Biloba L. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Bai, P.-P.; Gu, K.-J.; Yang, S.-Z.; Lin, H.-Y.; Shi, C.-G.; Zhao, Y.-P. Dynamic Transcriptome and Network-Based Analysis of Yellow Leaf Mutant Ginkgo Biloba. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohn, T.; Bonet, M.L.; Borel, P.; Keijer, J.; Landrier, J.-F.; Milisav, I.; Ribot, J.; Riso, P.; Winklhofer-Roob, B.; Sharoni, Y.; et al. Mechanistic Aspects of Carotenoid Health Benefits—Where Are We Now? Nutr. Res. Rev. 2021, 34, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.-X.; Tao, Y.; Wang, Q.-H.; Xu, M.-Q.; Zhang, F.-L.; Xie, Y.-K.; Xiao, H.-W. Postharvest Ripening-Induced Modification of Cell Wall Polysaccharide Affects Plum Phenolic Bioavailability. Food Chem. 2025, 479, 143780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.; Yao, J.; Miao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Gao, Y.; Sun, C.; Li, R.; Xiao, H.; Feng, Q.; Qin, G.; et al. Pharmacological Activities and Effective Substances of the Component-Based Chinese Medicine of Ginkgo Biloba Leaves Based on Serum Pharmacochemistry, Metabonomics and Network Pharmacology. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1151447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Zhang, M.-X.; Wang, X.-Y.; Yang, Y.-L.; Gong, X.; Wang, C.-C.; Xu, J.-F.; Li, M.-H. Assessment of Components of Gingko Biloba Leaves Collected from Different Regions of China That Contribute to Its Antioxidant Effects for Improved Quality Monitoring. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 41, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šamec, D.; Karalija, E.; Dahija, S.; Hassan, S.T.S. Biflavonoids: Important Contributions to the Health Benefits of Ginkgo (Ginkgo Biloba L.). Plants 2022, 11, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Evans, P.C.; Strijdom, H.; Xu, S. Isoginkgetin, a Natural Biflavonoid from Ginkgo Biloba, Inhibits Inflammatory Response in Endothelial Cells via Suppressing NF-ΚB Activation. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-T.; Huang, H.; Chang, Y.-H.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Wang, J.-D.; Cai, Z.-H.; Efferth, T.; Fu, Y.-J. Biflavonoids from Ginkgo Biloba Leaves as a Novel Anti-Atherosclerotic Candidate: Inhibition Potency and Mechanistic Analysis. Phytomedicine 2022, 102, 154053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosto, N. In Silico Molecular Docking and ADMET Prediction of Ginkgo Biloba Biflavonoids as Dual Inhibitors of Human HMG-CoA Reductase and α-Amylase. J. Serbian Chem. Soc. 2025, 90, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-T.; Fan, X.-H.; Jian, Y.; Dong, M.-Z.; Yang, Q.; Meng, D.; Fu, Y.-J. A Sensitive and Selective Multiple Reaction Monitoring Mass Spectrometry Method for Simultaneous Quantification of Flavonol Glycoside, Terpene Lactones, and Biflavonoids in Ginkgo Biloba Leaves. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 170, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Zhang, C. Metabolic Interaction between Biflavonoids in Ginkgo Biloba Leaves and Tacrolimus. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2023, 44, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurčević Šangut, I.; Pavličević, L.; Šamec, D. Influence of Air Drying, Freeze Drying and Oven Drying on the Biflavone Content in Yellow Ginkgo (Ginkgo Biloba L.) Leaves. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Jiang, Y.; Luo, X.; Zheng, Y.; Zhu, L.; Sun, C.; Linghu, L.; Qin, C.; Gang, W. Ultrasonic-Assisted Ionic Liquid Extraction of Four Biflavonoids from Ginkgo Biloba L. ChemistrySelect 2021, 6, 3297–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhong, W.; Shu, C.; Yang, H.; Li, E. Comparative Analysis of Chemical Constituents and Bioactivities of the Extracts from Leaves, Seed Coats and Embryoids of Ginkgo Biloba L. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 5498–5501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Chaudhary, A.; Singh, B. Gopichand Simultaneous Quantification of Flavonoids and Biflavonoids in Ginkgo Biloba Using RP-HPTLC Densitometry Method. J. Planar Chromatogr.—Mod. TLC 2011, 24, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, N.; Liu, Y.; Cui, Y.; Xin, H. Large-Scale Targetedly Isolation of Biflavonoids with High Purity from Industrial Waste Ginkgo Biloba Exocarp Using Two-Dimensional Chromatography Coupled with Macroporous Adsorption Resin Enrichment. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 175, 114264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šalić, A.; Šepić, L.; Turkalj, I.; Zelić, B.; Šamec, D. Comparative Analysis of Enzyme-, Ultrasound-, Mechanical-, and Chemical-Assisted Extraction of Biflavonoids from Ginkgo Leaves. Processes 2024, 12, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šalić, A.; Bajo, M.; Cvjetko Bubalo, M.; Radović, M.; Jurinjak Tušek, A.; Zelić, B.; Šamec, D. Extraction of Polyphenolic Compounds from Ginkgo Leaves Using Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Potential Solution for the Sustainable and Environmentally Friendly Isolation of Biflavonoids. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 219, 119068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Shi, R.; Hu, H.; Hu, L.; Wei, Q.; Guan, Y.; Chang, J.; Li, C. Medicinal Values and Potential Risks Evaluation of Ginkgo Biloba Leaf Extract (GBE) Drinks Made from the Leaves in Autumn as Dietary Supplements. Molecules 2022, 27, 7479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Leaves from Trees | Fallen Leaves | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | 3 October 2022 | 24 October 2022 |

| II. | 18 October 2022 | 2 November 2022 |

| III. | 2 November 2022 | 7 November 2022 |

| IV. | 7 November 2022 | 21 November 2022 |

| Leaves from Trees | ||||

| Chl a (µg/g dw) | Chl b (µg/g dw) | Total Chls (µg/g dw) | Total Car (µg/g dw) | |

| I | 611.87 ± 19.43 a | 105.42 ± 8.75 a | 717.29 ± 28.03 a | 66.70 ± 4.63 d |

| II | 232.96 ± 9.03 b | 52.67 ± 6.72 a | 285.62 ± 11.19 b | 63.77 ± 7.79 d |

| III | 98.95 ± 12.15 cd | 87.92 ± 20.70 a | 186.87 ± 32.84 cd | 90.95 ± 0.78 c |

| IV | 126.09 ± 4.41 c | 91.94 ± 5.37 a | 218.03 ± 9.37 bc | 105.48 ± 1.38 b |

| Fallen leaves | ||||

| Chl a (µg/g dw) | Chl b (µg/g dw) | Total Chls (µg/g dw) | Total Car (µg/g dw) | |

| I | 57.25 ± 7.57 de | 63.20 ± 10.14 a | 120.44 ± 17.70 d | 110.61 ± 1.56 b |

| II | 56.63 ± 10.18 e | 87.22 ± 16.45 a | 143.85 ± 26.54 cd | 143.47 ± 2.08 a |

| III | 63.88 ± 13.41 de | 93.49 ± 29.70 a | 157.37 ± 43.00 cd | 73.27 ± 0.85 d |

| IV | 68.86 ± 14.28 de | 69.61 ± 20.97 a | 138.47 ± 35.26 cd | 153.26 ± 1.08 a |

| Leaves from Trees | |||

| TP (µg GAE/mg dw) | TF (µg CE/mg dw) | TPA (µg CAE/mg dw) | |

| I | 33.52 ± 0.50 g | 4.10 ± 0.26 d | 0.95 ± 0.01 c |

| II | 45.91 ± 0.32 d | 5.26 ± 0.17 c | 1.00 ± 0.04 c |

| III | 41.85 ± 0.40 e | 5.01 ± 0.17 cd | 1.07 ± 0.13 bc |

| IV | 38.60 ± 0.23 e | 4.74 ± 0.10 cd | 1.19 ± 0.04 bc |

| Fallen leaves | |||

| TP (µg GAE/mg dw) | TF (µg CE/mg dw) | TPA (µg CAE/mg dw) | |

| I | 62.52 ± 2.41 a | 62.52 ± 2.41 a | 62.52 ± 2.41 a |

| II | 58.80 ± 1.01 b | 58.80 ± 1.01 b | 58.80 ± 1.01 b |

| III | 38.28 ± 0.16 f | 38.28 ± 0.16 f | 38.28 ± 0.16 f |

| IV | 49.49 ± 0.81 c | 49.49 ± 0.81 c | 49.49 ± 0.81 c |

| Leaves from Trees | ||||

| I | II | III | IV | |

| Amentoflavone | 48.82 ± 14.22 b | 49.94 ± 13.25 b | 57.69 ± 22.85 bd | 55.43 ± 17.67 b |

| Bilobetin | 469.77 ± 124.24 b | 494.59 ± 151.56 b | 526.82 ± 220.06 b | 519.16 ± 179.52 b |

| Ginkgetin | 1022.66 ± 177.51 b | 1133.47 ± 235.31 b | 1091.05 ± 452.31 b | 1170.72 ± 229.13 b |

| Isoginkgetin | 1172.25 ± 280.80 bd | 1234.57 ± 340.23 bcd | 1137.08 ± 697.23 b | 1278.48 ± 392.13 a |

| Sciadopitysin | 2060.55 ± 278.71 b | 2242.87 ± 360.21 bc | 2394.96 ± 465.57 a | 2346.62 ± 392.29 bc |

| Fallen leaves | ||||

| I | II | III | IV | |

| Amentoflavone | 88.20 ± 1.86 acd | 102.20 ± 16.38 a | 67.11 ± 0.47 bc | 92.29 ± 1.07 ac |

| Bilobetin | 870.99 ± 19.99 a | 915.22 ± 28.89 a | 656.23 ± 3.39 b | 851.95 ± 17.32 a |

| Ginkgetin | 1675.26 ± 35.86 a | 1497.30 ± 57.26 ab | 1350.85 ± 11.13 ab | 1324.33 ± 20.35 ab |

| Isoginkgetin | 2006.11 ± 42.25 a | 1962.37 ± 26.58 ac | 1599.52 ± 11.69 a | 1896.62 ± 39.60 ad |

| Sciadopitysin | 2994.26 ± 60.67 a | 2738.20 ± 32.41 ac | 2685.81 ± 23.45 ac | 2707.69 ± 42.57 ac |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jurčević Šangut, I.; Šamec, D. From Waste to Resource: Valorization of Yellow Ginkgo Leaves as a Source of Pharmacologically Relevant Biflavonoids. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11436. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111436

Jurčević Šangut I, Šamec D. From Waste to Resource: Valorization of Yellow Ginkgo Leaves as a Source of Pharmacologically Relevant Biflavonoids. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11436. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111436

Chicago/Turabian StyleJurčević Šangut, Iva, and Dunja Šamec. 2025. "From Waste to Resource: Valorization of Yellow Ginkgo Leaves as a Source of Pharmacologically Relevant Biflavonoids" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11436. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111436

APA StyleJurčević Šangut, I., & Šamec, D. (2025). From Waste to Resource: Valorization of Yellow Ginkgo Leaves as a Source of Pharmacologically Relevant Biflavonoids. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11436. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111436