Featured Application

This research paper examines the enrichment of wheat–oat bread with beetroot-based additives. The novelty of this study lies in the practical application of various beetroot-based products (including a by-product of juice production, i.e., pomace), which can potentially increase the content of bioactive components in the bread. The results provide insight into the impact of the type of beetroot-based additive on the technological and quality aspects of wheat–oat bread.

Abstract

Beetroot-based additives are interesting for enriching bread in terms of bioactive compounds. The objective of this study was to determine the effect of the following beetroot-based additives: a beetroot lyophilizate powder (wheat–oat baking mix flour was replaced in proportions of 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, 10%), a beetroot juice (water was replaced with juice in proportions of 25, 50, 75, 100%) and a by-product of beetroot juice production, i.e., pomace (wheat–oat baking mix flour was replaced in proportions of 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, 10%) on the quality of wheat–oat bread and the content of bioactive components in this type of bread. The properties of the dough were also assessed. The type and percentage level of partially replacing wheat–oat baking mix flour or water with beetroot-based additives had a significant impact on water absorption, dough development, and stability time of the tested dough. The beetroot juice (BJ) and powder (BLP) had the most significant impact on the rheological properties of the dough, whereas the pomace (BP) had the smallest effect. Beetroot-based additives, especially powder and juice, reduced the volume of bread (from 199 to 148 cm3/100 g of bread) but did not change oven loss [%] and bread crumb porosity index. Breads with these additives showed higher increased values for dough yield [%] and bread yield [%] (for beetroot powder—by 10% compared to the control sample (133.37% and 113.83%)). Tested additives had an impact on the crust and crumb color of the tested wheat–oat breads. The proposed additives significantly increased the antioxidant activity, total phenolic content, and betalain content in the bread samples. The above results showed that, from a technological point of view, replacing water or flour in the wheat–oat bread recipe with beetroot-based additives with a maximum concentration of 5% for BP or BLP and 50% for BJ allows for obtaining a product of good quality.

1. Introduction

Among cereal products, bread has a special place in the human daily diet. The modern consumer, who is aware of the nutritional value of bread, is mainly interested in its health-promoting properties. The quantitative and qualitative profile of bioactive ingredients found in bread is a result of the technological process, and therefore, from the grain to the slice of bread, corresponding to one portion of cereal products in the model of healthy nutrition, is associated with these new properties of bread [1]. The health-promoting value of bread can be improved by using baking mix flours, most often made from a combination of wheat flour with oat and barley flours or gluten-free cereals (corn, rice, millet) and pseudocereals flours (buckwheat, quinoa). Such mixes have high technological functionality due to the content of wheat flour, but also improved nutritional value [2,3,4]. Researchers are also interested in enriching bread with fruit and vegetable raw materials rich in antioxidants and dietary fiber, as well as by-products from juice production. It has been shown that using pomace, e.g., from blackcurrant, pomegranate, apple, or carrot, to enrich bread significantly contributes to increasing its nutritional value, without losing its sensory acceptability [5,6,7].

Beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) is a biennial plant whose primary edible part is the storage root. It is considered a health-promoting raw material due to the presence of essential nutrients such as vitamins, minerals, phenols, carotenoids, nitrates, ascorbic acid, and betalains [8]. These compounds act as antioxidants, simultaneously exhibiting anti-wrinkle, antithrombotic, anticancer, and hepatoprotective properties. They also support the treatment of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension, and accelerate wound healing [9,10]. Betalains are highly soluble in water, but they are compounds that require special processing conditions (pH and temperature) in order to preserve their health-promoting properties. Therefore, prolonged heat treatment should be avoided for foods rich in betalains. The use of acetic or lactic acid fermentation in the processing of beetroot roots is particularly beneficial for betalain protection [11,12,13]. This creates an opportunity to use beetroot and beetroot-based products with their health-promoting properties as an additive to other food products [14,15], for example, in baking technology to improve the health-promoting value of bread and other baked goods. In recent studies focusing on new food development, authors analyzed the addition of one type of beetroot-based product, for example, juice [16] or freeze-dried powder [17] to wheat bread. Their bread enriched with a beetroot-based additive had better nutritional and antioxidant properties compared to the control bread. These vegetable additives also had a significant impact on the quality parameters of the tested wheat bread.

Currently, the use of pseudocereal products and non-cereal raw materials is becoming increasingly common in bread production. Among cereal products, oat products (Avena sativa L.) are an excellent source of soluble dietary fiber, β-glucans, and polysaccharides, making them an ideal material for bread production, particularly from a nutritional perspective. Oat products are also a good source of minerals, B vitamins, tocochromanols, and other antioxidants [18]. Therefore, it would be interesting to investigate the effect of replacing wheat flour with oat flour in a bread recipe and its ability to produce good-quality bread.

However, no study has assessed the possible applications of three types of beetroot-based additives (powder, juice, and a by-product of juice production, i.e., pomace) in another type of bread, for example, wheat–oat bread. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the effect of beetroot-based additives in three forms: a beetroot lyophilizate powder, a beetroot juice, and a by-product of beetroot juice production, i.e., pomace, on the quality and the content of bioactive components in wheat–oat bread.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The research material included wheat–oat breads made from wheat–oat baking mix flour (in a preliminary experimentally determined combination 4:1 ratio) made from wheat flour (type 650, producer: Gdańskie Młyny, Gdansk, Poland) and oat flour (producer: Melvit, Warsaw, Poland) with beetroot-based (Czerwona Kula cultivar) additives: a beetroot lyophilizate powder, a beetroot juice, and a by-product of beetroot juice production, i.e., pomace, in four different percentage levels in the control sample recipe.

The flours included in the baking mix, according to the manufacturers’ information, were characterized by the proximate composition, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Proximate composition of flours included in wheat–oat baking mix (according to the manufacturer’s information on the packaging).

Table 2 presents the calculated content of the proximate composition of the various beetroot-based additives used.

Table 2.

Proximate composition of used beetroot-based additives.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. The Preparation of Beetroot-Based Additives

All used beetroot-based additives were made in the laboratory. The beetroot lyophilizate powder (BLP) was made from freeze-dried and ground beetroot slices using an ALPHA 1-2 LD plus freeze dryer (CHRIST, Osterode am Harz, Germany) (drying temperature: −42 °C; pressure: 0.010 MPa; drying time: 72 h), and a CEMOTEC 1090 laboratory grinder (Foss, Hillerod, Denmark). At one time, 2 kg of fresh slices of beetroot were dried, from which 200 g of powder was obtained. The finished powder was stored at −20 °C for a maximum of 2 months.

Preparation of the beetroot juice (BJ) included initial grinding of beetroot into pulp using a hydraulic fruit and vegetable press (Norwalk, Mount Vernon, NY, USA) and then squeezing the juice from it using a Hurom HG-SBE11 slow juicer (Hurom, Seoul, Republic of Korea). Beetroots were processed into juice with the peel after washing and preliminary selection of the raw material, where only damaged, deformed, or rotten parts were removed. A total of 10 kg of roots were used to prepare one batch of juice, from which, depending on the dry matter content, an average of 4.5 L of juice was obtained.

The by-product obtained after squeezing the juice from beetroots was another type of additive, i.e., pomace (BP). An average of 6 kg of pomace was obtained from a batch of 10 kg of roots.

2.2.2. Farinographic Analysis of Wheat–Oat Baking Mix Flour and Dough

Farinographic analysis was performed using a farinograph-E (Brabender, Duisburg, Germany) according to the Standard ICC nr 115/1 [20]. The following parameters of flour and dough were measured at consistency 500 FU: water absorption (%) of the flour, dough development time (min), dough stability time (min), softening (FU) of dough, and farinographic quality number. As part of this analysis, dough samples with beetroot-based additives were prepared, replacing wheat–oat flour with lyophilizate powder (BLP) or pomace (BP) (2.5, 5.0, 7.5, 10% by weight of the flour) and replacing water with beetroot juice (BJ) (25, 50, 75, 100% by amount of water). The control sample consisted of wheat–oat baking mix flour dough.

2.2.3. Laboratory Baking Test of Bread

The bread dough was prepared using a single-phase method according to Jakubczyk and Haber [21]. The dough of the control sample (CS) was made from 320.0 g wheat–oat baking mix flour, 9.60 g of baker’s yeast (Lallemand, Józefów, Poland), 4.80 g of salt, and 203.0 mL water (up to a consistency of 350 FU) using a laboratory mixer (Mesko-AGD, Skarżysko-Kamienna, Poland). The tested samples with beetroot-based additives contained the following:

- Beetroot lyophilizate powder (BLP): 2.5 (BLP2.5), 5.0 (BLP5.0), 7.5 (BLP7.5), 10% (BLP10) of flour weight in the control sample recipe.

- Beetroot juice (BJ): 25% (BJ25), 50% (BJ50), 75% (BJ75), 100% (BJ100) of the amount of water in the control sample recipe.

- By-product of beetroot juice production, i.e., pomace (BP): 2.5 (BP2.5), 5.0 (BP5.0), 7.5 (BP7.5), 10% (BP10) of flour weight in the control sample recipe.

The total dough fermentation time in the fermentation chamber (Sveba Dahlen, Fristad, Sweden) (temp.: 30 °C; humidity: 85%) was 60 min. After 30 min, the dough was mixed for 1 min. After the fermentation was completed, 250 g dough pieces were formed, then placed in molds and placed in the fermentation chamber for optimal proofing (to double the original volume of the dough piece). Baking was conducted at 230 °C for 30 min in a baking chamber of a Classic electric oven (Sveba Dahlen, Fristad, Sweden). Afterward, the bread loaves were weighed and left to cool.

2.2.4. Quality Parameters of Bread

Twenty-four hours after baking, the tested breads were weighed. Then, the parameters of the laboratory baking process were calculated, such as dough yield (%), oven loss (%), and bread yield (%), described by Jakubczyk and Haber [21]. The loaf volume (cm3) was analyzed using millet seeds, according to AACC Method No. 10-05.01 [22]. Additionally, the crumb moisture content was analyzed according to AACC Method No. 44-15.02 [23], and crumb porosity was determined using the Dallman scale [24]. The bread crust and crumb color parameters were determined in the CIE L*a*b* model using an UltraScan VIS colorimeter (HunterLab, Reston, VA, USA) [25,26]. As part of this analysis, the L* parameter defining the lightness, a* (red/green color saturation), and b* (yellow/blue color saturation) were measured. Additionally, the bread crust and crumb total color difference (ΔE) was calculated [27]. The ΔE parameter was calculated according to the mathematical relationship:

The determinations and calculations were performed in triplicate. The color of all breads (crust and crumb) was measured 24 h after baking. An average of three measurements for L*, a*, and b* values was recorded. Mean values of at least 3 breads were taken for statistical purposes.

All analyses were performed in triplicate for all varieties of bread from each production batch.

2.2.5. Total Phenolic Content, Antioxidant Activity, and Betalain Content of Breads

Extract Preparation

Samples of the crust and crumb of the tested breads were frozen, freeze-dried, and ground separately. The extracts were prepared for the bread crust and crumb separately. Then, 1 g of the powdered material was extracted with 5 mL of 50% methanol solution using an ultrasound bath (Sonic 10, Polsonic, Warsaw, Poland) at 30 °C for 20 min. Next, mixtures were centrifuged (7000 rpm) using a laboratory centrifuge (Centrifuge 5430, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) for 10 min. The collected supernatants were used for further analysis.

Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity

The total content of phenolic compounds (TPC) was assessed according to Gao et al. (2000) [28]. The results were expressed in mg of gallic acid (GAE) per 100 g of fresh mass of bread crust or crumb. The tests were performed in triplicate.

ABTS+ radical scavenging activity assay (ABTS) was assessed according to Re et al. (1999) [29]. The results were expressed in µmol Trolox (µmol TE) per 100 g of fresh mass of bread crust or crumb. The tests were performed in triplicate.

Betalains Content

The content of betalain pigments was determined using the spectrophotometric method according to Ruiz-Gutiérrez et al. (2015) [30] and Nilsson (1970) [31]. The contents of betacyanin and betaxanthin were determined. The results were expressed in mg per 100 g of fresh mass of bread crust or crumb. The tests were performed in triplicate.

2.2.6. Statistical Analysis

Mean values of the parameters and standard deviations (±SD) were calculated using Excel 2016 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 13.3 (Tibco Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). The significance of differences between mean values was established using one-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) along with Duncan’s test at the significance level of p ≤ 0.05. All analyses and bread baking were performed in triplicate.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Rheological Properties of Wheat–Oat Baking Mix Flour and Dough

Table 3 presents the results of the analysis of the water absorption of wheat–oat baking mix flour and the ability of the tested baking mix flour to absorb water with the addition of beetroot-based additives, as well as the results of the farinographic parameters of the control dough (tested wheat–oat baking mix flour dough) and doughs with beetroot-based additives (BLP, BJ, BP).

Table 3.

Results of farinographic analyses of tested wheat–oat doughs with beetroot-based additives.

The water absorption (WA) of the tested wheat–oat mix flour differed from all the analyzed variants with BLP, BJ, and BP (Table 3). The water absorption of the control sample (CS) was 58.8%. Doughs with beetroot juice (BJ) showed values 2–3% higher than those obtained for the CS. In turn, beetroot pomace (BP) and lyophilizate powder (BLP) caused a decrease in the WA value in relation to those obtained for the CS. In the case of BP, water absorption ranged from 55.3 to 57.7%, and for the variants with BLP, from 56.0 to 57.6%. Beetroot juice (BJ), powder (BLP), and pomace (BP) differ significantly in dietary fiber content (Table 2). Despite its high content, the powder (BLP) did not significantly affect the water absorption (WA) of the wheat–oat mix flour compared to the control sample (58,8%). A surprising decrease in this parameter was even observed for higher doses of powder (BLP10—56.0%) and pomace (BP10—55.3%). Similar results under the addition of beetroot powder were reported by Ashwath Kumar et al. (2023) [32]. On the other hand, in previous studies [33,34], an increase in water absorption was determined under the influence of the participation of high-fiber products in the baking mix flour. Similar results were obtained for samples with beetroot juice (BJ25-BJ100) (Table 3). As J. Xu et al. (2021) [35] reported, the fiber from additives (e.g., fruit or vegetable powders, juices, pomaces) interacts with water added to flour to make a dough, mainly through hydrogen bonding via the hydroxyl groups on the fiber structure, which leads to an increase in the water absorption of the baking mix flour. The important factors are the chemical structure of the fiber fractions, particle size, porosity, and association between the molecules, which have an influence on the water absorption capacity [36].

The dough development time for the control sample (CS) reached an average value of 12.6 min. In most of the samples with BLP, BJ, and BP, the value of DDT was lower (Table 3), which may indicate a significant effect of beetroot-based additives on the time of combining the dough ingredients from the wheat–oat baking mix flour. The doughs with BJ or BLP achieved the target consistency of 500 FU faster (from 5.1 to 7.2 min), probably due to the introduction of soluble dietary fiber fraction with the BJ or total dietary fiber with the BLP. Only the doughs with BP did not differ significantly from the control dough (CS). Similarly, other authors also noted a reduction in dough development time under the influence of high-fiber additives, which may confirm that similar interactions between the ingredients of additives and gluten proteins occurred in the doughs [37,38]. Stability time [min] for the CS of 16.2 min was recorded (Table 3). The stability of doughs with BJ was significantly shorter, by as much as 9–12 min, compared to the CS. A similar relationship was observed for doughs with the BLP (3.6–6.4 min shorter than CS). The addition of the BP had the smallest effect on the dough stability time. Samples with BP showed stability time from 12.0 to 18.9 min (Table 3). This indicates a significant effect of BJ and BLP additives on a faster loss of elasticity by the gluten formed in the dough, probably due to the interaction of gluten proteins and the ingredients of the beetroot-based additives. Also, especially for BLP addition, this could have been due to the high fiber content, particularly the dough with 10% of beetroot powder (BLP10), which reached the 500 FU consistency faster. These high-fiber and high-polyphenol additives interfered with gluten network formation. Antioxidant phenolic compounds donate electrons to disulfide bonds, thus breaking the bond and creating thiol residues within the gluten protein chain. This results in decreased dough strength and stability [35,39,40]. Similar results were noted by other authors in earlier studies regarding doughs with citrus by-product powder [37]. In our study, the control sample’s (CS) softening was 3 FU (Table 3). Samples with the addition of BP and BLP did not differ in dough softening compared to the CS. In turn, doughs with BJ were characterized by higher softening (31–94 FU). The differences in the softening of the tested wheat–oat doughs could have resulted from the different fiber content in the beetroot-based additives used, which is confirmed by previous studies [38,41] about the significant influence of high fiber additives on the behavior of gluten proteins in wheat dough. The farinographic analysis of wheat–oat doughs was summarized by determining the quality number value (FQN). The FQN for the control sample (CS) was 200, mainly due to the long stability time exceeding the dough development time. Samples with BJ, due to short stability times compared to dough development time and high softening values, obtained an FQN ranging from 73 to 100. Similar values were obtained for samples with BLP (from 78 to 111). On the other hand, the addition of beetroot pomace (BP) produced doughs with quality numbers ranging from 134 to 200, values close to the quality number of the control dough (Table 3).

Based on the farinographic analysis, it was found that the changes in the farinographic parameters of the baking mix flour and the doughs with the beetroot-based additives could depend on the type of additive. The observed changes in dough properties were caused by interactions between gluten proteins, dietary fiber, and β-glucans of the baking mix flour and the components of beetroot juice (BJ), pomace (BP), and freeze-dried powder (BLP) (polyphenols, tannins, dietary fiber) [39,40,42].

3.2. Quality Parameters of Wheat-Oat Breads

Table 4 shows parameters related to the laboratory baking test of wheat-oat breads.

Table 4.

Results of bread baking process and quality parameters of tested wheat–oat breads with beetroot-based additives.

The dough yield of tested samples differed significantly, which was influenced by the type and percentage level of BLP, BJ, or BP additives (Table 4). A significant increase in the value of this parameter was noted for samples with beetroot powder (BLP). The dough yield for breads with BLP was 2–12% higher than the control sample (CS), 133.37%. In the case of oven loss, a significant factor differentiating the samples was the percentage level of beetroot-based additive in the bread. The type of beetroot-based additive did not significantly affect the values of this parameter. The control bread (CS) achieved an oven loss of 9.11%. The samples with BLP, BJ, or BP had increasing values of this parameter with the increase in the percentage level of the tested additives (Table 4). In turn, Minarovičová et al. (2018) [43] reported a decrease in oven loss value (from 10.12% for the control sample to 8.37% for the sample with 5% of pumpkin powder) for wheat baked rolls with the addition of pumpkin powder. In our study (Table 4), the breads with added juice (BJ25-BJ100) had a similar bread yield to the control sample (CS—113.83%), while the addition of powder (BLP) or pomace (BP) significantly increased the values of this parameter. Additionally, Cacak-Pietrzak et al. (2023) [44] noted an increase in the bread yield value for wheat breads with dandelion flower powder. Although the tested type of beetroot-based additive did not have a significant effect on oven loss, it caused a loss of bread mass after cooling and, therefore, bread yield (Table 4).

The bread loaf weight of the tested breads ranged from 210.38 g to 218.00 g (Table 4). It was only significantly different depending on the type of beetroot-based additive. The bread volume of the tested breads (Table 4) showed a significant effect of the type of beetroot-based additive and its percentage level in the bread. Most of the tested breads with BJ, BP, or BLP were of smaller volume, up to 50 cm3/100 g of bread (BLP10), than the CS value (199 cm3/100 g of bread). Probably, the reason for this decrease was the influence of fiber from the beetroot-based additives disrupting the gluten network in the tested dough piece and thus reducing the ability to retain gas produced during fermentation. A similar relationship under the addition of high-fiber products to bread (mainly powder) was reported by Cacak-Pietrzak et al. (2023) [44] and Ashwath Kumar et al. (2023) [32]. On the contrary, Odunlade et al. (2017) [45] obtained a bread with fruit and vegetable powders with a greater volume than that recorded in our discussed research (Table 4). On the other hand, the control bread (CS) volume (Table 4) was similar to the wheat–oat bread volume obtained by Angioloni and Collar (2013) [46]. This similarity proves that the wheat–oat baking mix flour used can be a good matrix for enriching with beetroot-based additives. The crumb moisture content of the tested breads (Table 4) was significantly differentiated depending on the type of beetroot-based additive and its percentage level in the bread. The highest values were shown by the samples with BP, from 0.6 to 1.5% higher than the crumb moisture of CS (45.07%). Breads with BJ or BLP had lower crumb moisture (on average by 1–2%) than the control bread (CS). These differences in crumb moisture content could be mainly caused by different levels of dietary fiber in the beetroot-based additives used in bread production (Table 2). This dietary fiber was responsible for the differences in dough water retention during baking, included as oven loss (Table 4), as well as moisture content in the crumb of the finished product (Table 4). Similar crumb moisture values to those obtained in our discussed studies (Table 4) were noted by Baiano et al. (2015) [47] and Kawka and Górecka (2010) [48]. The lowest Dallman’s crumb porosity index (80) was shown by samples BJ100 and BL10 (Table 4). The crumb of the CS and the other tested variants obtained a Dallman’s crumb porosity index of 90.

Study results of quality parameters of tested breads (Table 4) were related to the results of the farinographic analysis (Table 3), especially values of water absorption of the flour mix and dough stability time, and softening of the dough. Lower values of water absorption of the flour mix and parameters of the dough caused lower bread volume. The used beetroot-based additives also had an influence on gas retention in the gluten network during dough fermentation. This could be especially visible in the smaller bread volume (Table 4), which was different depending on the type and percentage level in bread with beetroot-based additives.

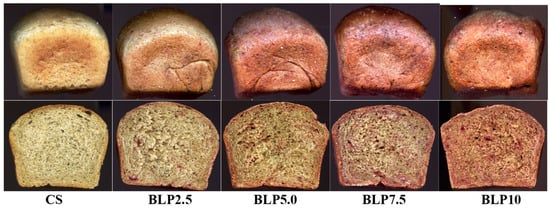

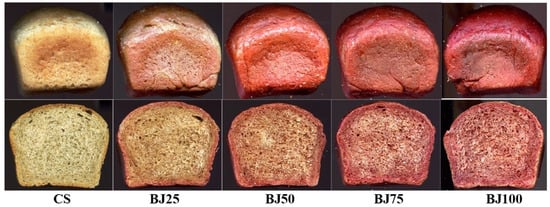

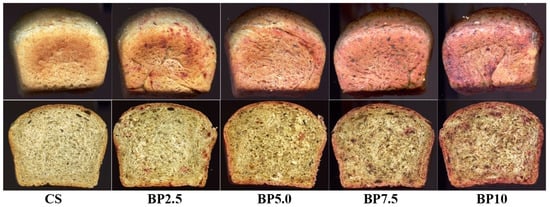

A significant factor in determining bread quality and consumer acceptance is the product’s color. Table 5 presents the results of tests and calculations regarding the color of the tested wheat–oat breads with beetroot-based additives. The appearance of the bread is presented in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Table 5.

Color parameters of tested wheat–oat breads with beetroot-based additives.

Figure 1.

The external appearance of the loaves and their crumbs of the tested wheat–oat breads with beetroot lyophilizate powder: CS—control sample; BLP2.5–BLP10—bread with 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, and 10% of beetroot lyophilizate powder.

Figure 2.

The external appearance of the loaves and their crumbs of the tested wheat–oat breads with beetroot juice: CS—control sample; BJ25–BJ100—bread with 25, 50, 75, and 100% of beetroot juice.

Figure 3.

The external appearance of the loaves and their crumbs of the tested wheat–oat breads with beetroot pomace: CS—control sample; BP2.5–BP10—bread with 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, and 10% of beetroot pomace.

The values of crust color parameters of the tested breads (Table 5) were significantly differentiated depending on the type of beetroot-based additive and the percentage level of the additive in the bread. The crust lightness (L) of the control sample (CS) was 56.24 (Table 5). The values of this parameter of the samples with BLP, BJ, or BP decreased with the gradual increase in the percentage level of each type of beetroot-based additive tested (maximum up to 33.30 for the BJ100). The chromaticity parameters of the crust for the CS were a* = 13.56 and b* = 32.08. It indicates the dominance of the yellow color component over the red in the crust color. On the other hand, in the samples with BLP, BJ, or BP, the share of the red color component increased with a slight decrease in the yellow color, depending on the type of beetroot-based additive and its percentage level in the bread (Table 5). The total color difference (ΔE) increased with a gradual increase in the percentage level of the used additive in the bread. In addition, according to the criterion established by the International Commission on Illumination (CIE), a total color difference (ΔE) between 0 and 2 is unrecognizable to an experienced observer, a color difference between 2 and 5 is recognizable, while a total color difference greater than 5 is significant and recognizable even by an inexperienced observer [27]. The ΔE values calculated for all tested bread crusts with additives (BJ, BP, BLP) showed a value of over 5, which is recognizable by an inexperienced observer (Table 5). The crumb color of the tested bread was significantly dependent on the type of beetroot-based additive and its percentage level in the bread (Table 5). Due to the introduction of chemical compounds with the tested beetroot-based additives to the bread recipe, and after their transformations during bread production (dough fermentation processes, baking bread), the crumb color of the finished products was darkened compared to the crumb of the CS (67.93). Additionally, these transformations were different in the crumb than in the crust of the tested bread with BLP, BJ, and BP, where Maillard reactions also occurred, leading to the formation of bioactive components. In the crumb color, a gradual increase in the values of the a* parameter was noted (by a maximum of 21 units for the BJ100) for all tested samples with beetroot-based additives and a decrease in the b* parameter value (by a maximum of 2 units) only for samples with juice (BJ) and powder (BLP) (Table 5). The increase in the percentage level of beetroot-based additives also caused a gradual change in the color of the bread crumb from light yellow to pink, red (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). Betalains introduced with beetroot-based additives may have been responsible for these changes in crumb color. These compounds have varying resistance to the temperature range used in production [8,49,50]. The lower temperature inside the crumb (approx. 100 °C) during baking allows for the preservation of betaxanthin (yellow betalains) in the finished product, while closer to the bread crust (temperature around 220 °C) preserves only betacyanin (purple betalains) (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). Also, the beetroot-based additives used differed in betalain content (Table 2), which also influenced the color of the crust and crumb of bread. In the samples with BP, a significant increase in the b* parameter value was noted, which indicated a higher share of the yellow color component in the color of the crumb. The crumb total color difference (ΔE) value from 9.54 to 36.96 was noted (Table 5). Parafati et al. (2020) [51] and Kohajdova et al. (2018) [52] noted similar parameters of the bread crust and crumb color for wheat bread with beetroot powder to disused results of our study (Table 5).

3.3. Total Phenolic Content, Antioxidant Activity, and Betalain Content of Wheat-Oat Breads

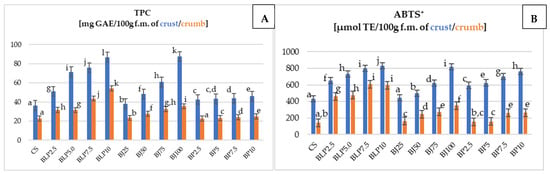

Beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) storage root is rich in bioactive compounds, including polyphenols. The results of the total phenolics content (TPC) assay and the antioxidant activity of wheat–oat breads with beetroot additives using the ABTS+ method are detailed in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The total phenolic content (TPC) (A) and antioxidant activity ABTS+ (B) of crust and crumb of tested wheat–oat breads with beetroot-based additives. Mean values from three repetitions ± SD. Values followed by the same superscript letters do not significantly differ at a significance level of 0.05, separately for the crumb and crust. Abbreviations: CS—control sample; BLP2.5–BLP10—bread with 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, and 10% of beetroot lyophilizate powder; BJ25–BJ100—bread with 25, 50, 75, and 100% of beetroot juice; BP2.5–BP10—bread with 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, and 10% of beetroot pomace; GAE—gallic acid equivalent; ABTS+—method of measuring antioxidant activity; TE—Trolox Equivalent; f.m.—fresh mass.

The TPC value of the crust (Figure 4A) was significantly different depending on the type of beetroot-based additive and its percentage level in the bread. Each type of beetroot-based additive increased the TPC of the bread crust with its increase in the percentage level in the bread. The TPC for the crust samples with BJ was higher by 2–51 mg GAE/100 g f.m., for the samples with BP by 6–10 mg GAE/100 g f.m., respectively, while for the samples with BLP, by 15–51 mg GAE/100 g f.m. compared to the CS crust (36.39 mg GAE/100 g f.m.). The TPC of the crumb (Figure 4A) varied significantly depending on the type of beetroot-based additive and its percentage level in the bread. Within each type of beetroot-based additive, increasing its percentage level in bread resulted in an increase in the content of biologically active substances in the bread crumb. For the crumb samples, the TPC value was higher by 0.13 (BP2.5—22.8 mg GAE/100 g f.m.) to 31.4 mg GAE in 100 g of fresh mass (BLP10—54.07 mg GAE/100 g f.m.) of the crumb compared to the control sample (22.67 mg GAE/100 g f.m.). The reason for this increase in TPC value was the transformations of these substances during bread production (dough fermentation processes, baking bread). Additionally, these transformations were different in the crumb than in the crust of the tested bread with BLP, BJ, and BP, where Maillard reactions also occurred, leading to the formation of bioactive components. This could have been the reason for the higher TPC values in the crust than in the crumb of the tested breads (Figure 4A). Cui et al. (2022) [53], Pekmez et al. (2018) [54], and Chhikara et al. (2019) [55] noted higher values of TPC compared to this research (Figure 4A). These authors examined steamed breads with beetroot powder, pita breads with black carrot pomace powder, and pasta with beetroot powder.

The antioxidant activity (Figure 4B) measured by the ABTS+ method of the crust of the tested bread differed on average by 100 µmol TE/100 g f.m., and for the crumb by 10 to even 100 µmol TE/100 g f.m. compared to the control sample (for crust—433.75, for crumb—141.41 µmol TE/100 g f.m.). Higher values for ABTS+ compared to our own research (Figure 4B) were noted by Cui et al. (2022) [53] in studies of steamed bread with beetroot powder and by Pekmez et al. (2018) [54] in studies of pita bread with black carrot pomace powder.

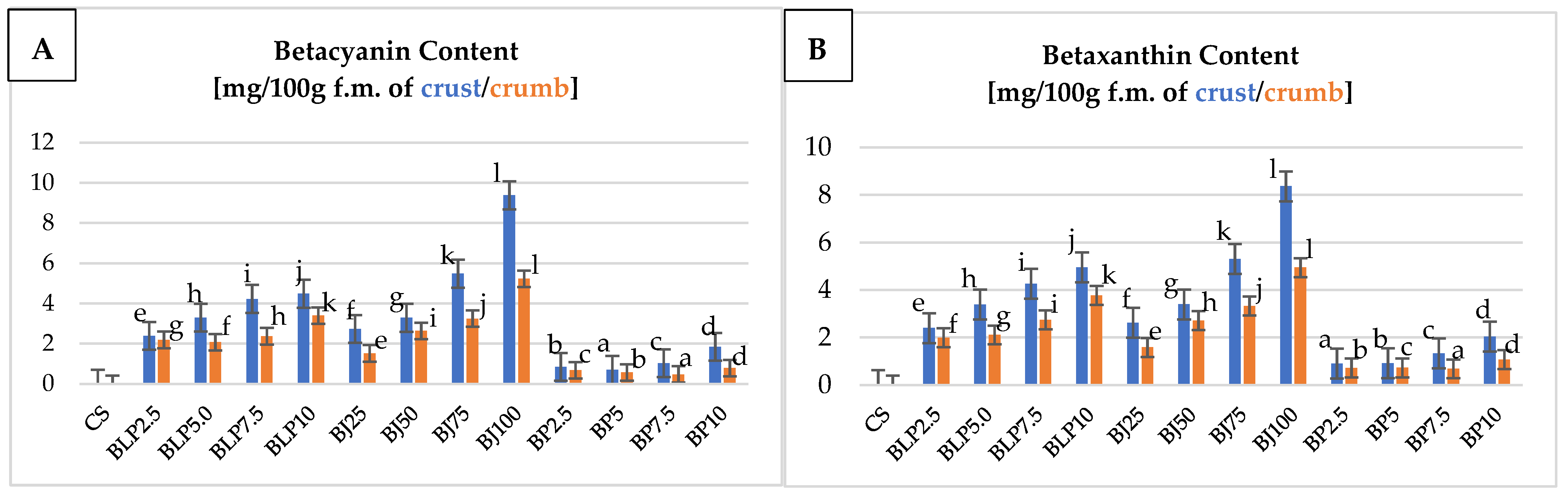

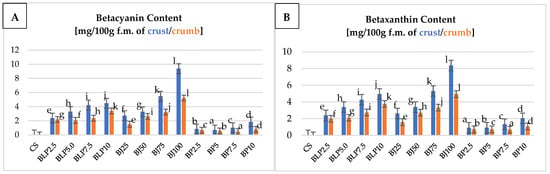

Betalains (betacyanin and betaxanthin) are bioactive compounds that give beetroot anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties [8,10]. The results of these compounds of wheat–oat breads with beetroot additives are detailed in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The content of betacyanin (A) and betaxanthin (B) of the crust and crumb of tested wheat–oat breads with beetroot-based additives. Mean values from three repetitions ± SD. Values followed by the same superscript letters do not significantly differ at a significance level of 0.05, separately for the crumb and crust. Abbreviations: CS—control sample; BLP2.5–BLP10—bread with 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, and 10% of beetroot lyophilizate powder; BJ25–BJ100—bread with 25, 50, 75, and 100% of beetroot juice; BP2.5–BP10—bread with 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, and 10% of beetroot pomace; f.m.—fresh mass.

The content of betacyanin and betaxanthin in the crust of the tested wheat–oat breads was significantly varied in terms of the type of beetroot-based additive used and its percentage level in the bread (Figure 5A,B). In the crust of the tested bread, betacyanin dominated for most variants (Figure 5A). The exception was breads with BP, where a higher content of betaxanthin was found (on average by 0.2 mg/100 g of f.m.) (Figure 5B). The highest content of betacyanin and betaxanthin was found in the crust of samples BJ75, BJ100, and BLP7.5, BLP10. For these samples, values from 4.225 to 9384 mg/100 g f.m. of crust were recorded. The content of betacyanin and betaxanthin in the crumb of the tested wheat–oat breads was significantly differentiated in terms of the type of beetroot-based additive used and its percentage level in the bread (Figure 5A,B). The crumb of the bread with BJ was characterized by a higher concentration of betacyanin than betaxanthin; it has a maximum of 1.5 mg higher content in 100 g of fresh mass of crumb than for the other tested beetroot-based additives (BP, BLP). On the other hand, in the crumbs of bread with BP and BLP, an inverse relationship was found. It was also confirmed by the results of the color of the tested breads (Table 5 and Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). The crumb of the bread with juice (BJ) was more pink/red (higher value of betacyanin content), while the crumb of bread with pomace (BP) or powder (BLP) was more yellow (higher value of betaxanthin content). The highest content of betacyanin and betaxanthin was found in the crumb of samples BJ75, BJ100, and BLP7.5, BLP10. The crumbs of these bread variants had more than 3 mg/100 g f.m. A higher content of betalain than that recorded in our own studies (Figure 5A,B) was obtained by Cui et al. (2022) [53] in their studies of traditional Chinese steamed breads with beetroot powder. These authors noted a betanin content (belonging to betacyanin) of 31 mg/100 g d.m. in the finished product with 10% beetroot powder. Similarly, Bouazizi et al. (2020) [56] noted the content of betacyanin at an average of 29 mg/100 g d.m. and betaxanthin at 20 mg/100 g d.m. in cookies containing opuntia fruit powder. These values were more than half as high as those obtained in our own studies (Figure 5A,B).

4. Conclusions

This research article concerned the enrichment of wheat–oat bread with beetroot-based additives. The novelty of this study is the practical application of various beetroot-based products (lyophilizate powder, juice) and their by-product (pomace), which could potentially improve the content of bioactive components in the bread. Each of the types of tested beetroot-based additives used had variations in their composition and physicochemical properties. The statistical analysis of the study results provides much information on the differences in the impact of beetroot-based additives on the bread’s quality. The changes in the water absorption of the baking mix flour and the quality parameters of the tested doughs with beetroot additives were confirmed by the farinographic analysis. The beetroot juice (BJ) and powder (BLP) had the most significant impact on the rheological properties of the dough, whereas the pomace (BP) had the smallest effect. Also, the results of the bread quality analysis, particularly the volume of the bread and the color of the crust and crumb, were dependent on the type of beetroot-based additives. Nevertheless, the tested additives, especially lyophilizate beetroot powder (BPL), improved the content of bioactive components in bread.

In summary, from a technological perspective, replacing water or flour in the recipe with beetroot-based additives at a maximum concentration of 5% for BP or BLP and 50% for BJ allows for obtaining a good quality product with the prospect of further improvement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.P.-S. and J.K.; methodology, Z.P.-S., J.K., I.T.K. and G.J.; software, Z.P.-S., J.K., I.T.K. and G.J.; validation, Z.P.-S., J.K., I.T.K. and G.J.; formal analysis, Z.P.-S., J.K., I.T.K. and G.J.; investigation, Z.P.-S., J.K., I.T.K. and G.J.; resources, Z.P.-S., J.K., I.T.K. and G.J.; data curation, Z.P.-S., J.K., I.T.K. and G.J.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.P.-S., J.K., I.T.K. and G.J.; writing—review and editing, Z.P.-S., J.K., I.T.K. and G.J.; visualization, Z.P.-S., J.K., I.T.K. and G.J.; supervision, J.K., I.T.K. and G.J.; project administration, Z.P.-S.; funding acquisition, J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Szawara-Nowak, G. Bioactive Components of Breads. Pol. J. Com. Sci. 2013, 3, 103–115. [Google Scholar]

- Kawka, A. Present trends in bakery production—Use of oats and barley as non-bread cereals. Food. Sci. Technol. Qual. 2010, 70, 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Czubaszek, A.; Karolini-Skaradzinska, Z.; Fujarczuk, M. Effect of added oat products on baking characteristics of rye-oat blends. Food. Sci. Technol. Qual. 2011, 78, 150–162. [Google Scholar]

- Gawęcki, J.; Obuchowski, W. (Eds.) Cereal Products. Technology and Role in Human Nutrition; UP: Poznań, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Filipcev, B.; Levic, L.; Bodroza-Solarov, M.; Misljenovic, N.; Koprivica, G. Quality characteristics and antioxidant properties of breads supplemented with sugar beet molasses-based ingredients. Int. J. Food Prop. 2010, 13, 1035–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivam, A.S.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Perera, C.O.; Waterhouse, G.I.N. Exploring the interactions between blackcurrant polyphenols, pectin and wheat biopolymers in model breads; a FTIR and HPLC investigation. Food Chem. 2012, 131, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunkaya, A.; Hedegaard, R.V.; Brimer, L.; Gokmen, V.; Skibsted, L.H. Antioxidant capacity versus chemical safety of wheat bread enriched with pomegranate peel powder. Food Funct. 2013, 4, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhikara, N.; Kushwaha, K.; Sharma, P.; Gat, Y.; Panghal, A. Bioactive compounds of beetroot and utilization in food processing industry: A critical review. Food Chem. 2019, 272, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavov, A.; Karagyozov, V.; Denev, P.; Kratchanova, M.; Kratchanov, C. Antioxidant activity of red beet juices obtained after microwave and thermal pretreatments. Czech J. Food Sci. 2013, 31, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, H.; de Joode, M.E.J.R.; Hossein, I.J.; Henckens, N.F.T.; Guggeis, M.A.; Berends, J.E.; de Kok, T.M.C.M.; van Breda, S.G.J. The benefits and risks of beetroot juice consumption: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 788–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyżowska, A.; Klewicka, E.; Libudzisz, Z. The influence of lactic acid fermentation process of red beet juice on the stability of biologically active colorants. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2006, 223, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakin MVukasinovis, A.; Siler-Marinkovic, S.; Maksimovic, M. Contribution of lactic acid fermentation to improved nutritive quality vegetable juices enriched with brewer’s yeast autolysate. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 599–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betoret, E.; Rosell, C.M. Enrichment of bread with fruits and vegetables: Trends and strategies to increase functionality. Cereal Chem. 2020, 97, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudgal, D.; Singh, S.; Singh, B.R. Nutritional composition and value added products of beetroot: A review. J. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Punia Bangar, S.; Singh, A.; Chaudhary, V.; Sharma, N.; Lorenzo, J.M. Beetroot as a novel ingredient for its versatile food applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 63, 8403–8427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raczyk, M.; Kruszewski, B.; Zachariasz, E. Effect of Tomato, Beetroot and Carrot Juice Addition on Physicochemical, Antioxidant and Texture Properties of Wheat Bread. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranawana, V.; Raikos, V.; Campbell, F.; Bestwick, C.; Nicol, P.; Milne, L.; Duthie, G. Breads Fortified with Freeze-Dried Vegetables: Quality and Nutritional Attributes. Part 1: Breads Containing Oil as an Ingredient. Foods 2016, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, E. Oats Products as Functional Food. Food Sci. Technol. Qual. 2010, 3, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunachowicz, H.; Przygoda, B.; Nadolna, I.; Iwanow, K. Tables of Composition and Nutritional Value of Food; PZWL Wydawnictwo Lekarskie: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Standard No. 115/1; Method for Using the Brabender Farinograph. International Association for Cereal Science and Technology: Vienna, Austria, 2003.

- Jakubczyk, T.; Haber, T. (Eds.) The Analysis of Cereals and Cereal Products; SGGW-AR: Warsaw, Poland, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Cereal Chemists International. Approved Methods of Analysis. Method 10-05.01. Guidelines for Measurement of Volume by Rapeseed Displacement, 11th ed.; AACC International: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Cereal Chemists International. Approved Methods of Analysis. Method No. 44-15.02. Guidelines for Measurement of Moisture Content—Air Oven Methods, 11th ed.; AACC International: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dallmann, H. Porentabelle; Schäfer: Neunkirchen, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Pycia, K.; Pawłowska, A.M.; Kaszuba, J.; Żurek, N. Walnut Male Flowers (Juglans regia L.) as a Functional Addition to Wheat Bread. Foods 2022, 11, 3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pycia, K.; Pawłowska, A.M.; Kaszuba, J. Assessment of the Application Possibilities of Dried Walnut Leaves (Juglans regia L.) in the Production of Wheat Bread. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clydesdale, F.M. Color perception and food quality. J. Food Qual. 1991, 14, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Ohlander, M.; Jeppsson, N.; Björk, L.; Trajkovski, V. Changes in Antioxidant Effects and Their Relationship to Phytonutrients in Fruits of Sea Buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) during Maturation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 1485–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Gutierrez, M.G.; Amaya-Guerra, C.A.; Quintero-Ramos, A.; Perez-Carillo, E.; Ruiz-Anchondo, T.D.J.; Báez-González, J.G.; Meléndez-Pizarro, C.O. Effect of extrusion cooking on bioactive compounds in encapsulated red cactus pear powder. Molecules 2015, 20, 8875–8892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, T. Studies into the pigments in beetroot (Beta vulgaris L. ssp. vulgaris var. rubra L.). Lantbrukshogskolans Ann. 1970, 36, 179–219. [Google Scholar]

- Ashwath Kumar, K.; Vanitha, T.; Sudha, M.L.; Meena Kumari, P.; Vijayanand, P.; Prabhasankar, P. Beta Vulgaris root as a natural food colouring in doughnut: Dough rheological properties and bioactive composition. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualone, A.; Laddomada, B.; Spina, A.; Todaro, A.; Guzmàn, C.; Summo, C.; Mita, G.; Giannone, V. Almond by-products: Extraction and characterization of phenolic compounds and evaluation of their potential use in composite dough with wheat flour. LWT 2018, 89, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubaker, M.; Omri, A.E.; Blecker, C.; Bouzouita, N. Fibre concentrate from artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) stem by-products: Characterization and application as a bakery product ingredient. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2016, 22, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, W. Influence of antioxidant dietary fiber on dough properties and bread qualities: A review. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 80, 104434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironeasa, S.; Luga, M.; Zaharia, D.; Mironeasa, C. Rheological analysis of wheat flour dough as influenced by grape peels of different particle sizes and addition levels. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2019, 12, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, A.G.; AbdEl-Hamied, A.A.; El-Naggar, E.A. Effect of citrus by-products flour incorporation on chemical, rheological and organoleptic characteristics of biscuits. World J. Agric. Sci. 2008, 4, 612–616. [Google Scholar]

- Bachir, B.; Rabetafika, H.N.; Paquot, M.; Blecker, C. Effect of pear, apple and date fibres from cooked fruit by-products on dough performance and bread quality. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2014, 7, 1114–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, A.L.; Awika, J.M. Effects of edible plant polyphenols on gluten protein functionality and potential applications of polyphenol–gluten interactions. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 2164–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Dhital, S.; Zhao, C.; Ye, F.; Chen, J.; Zhao, G. Dietary fiber-gluten protein interaction in wheat flour dough: Analysis, consequences and proposed mechanisms. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 111, 106203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolve, R.; Simonato, B.; Rainero, G.; Bianchi, F.; Rizzi, C.; Cervini, M.; Giuberti, G. Wheat Bread Fortification by Grape Pomace Powder: Nutritional, Technological, Antioxidant and Sensory Properties. Foods 2021, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astiz, V.; Guardianelli, L.M.; Salinas, M.V.; Brites, C.; Puppo, M.C. High β-Glucans oats for healthy wheat breads: Physicochemical properties of dough and breads. Foods 2022, 12, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minarovičová, L.; Lauková, M.; Karovičová, J.; Kohajdová, Z. Utilization of pumpkin powder in baked rolls. Slovak J. Food Sci./Potravin. 2018, 12, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacak-Pietrzak, G.; Dziki, D.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Sułek, A.; Wójcik, M.; Krajewska, A. Dandelion flowers as an additive to wheat bread: Physical properties of dough and bread quality. Appl. Sci. 2022, 13, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odunlade, T.V.; Famuwagun, A.A.; Taiwo, K.A.; Gbadamosi, S.O.; Oyedele, D.J.; Adebooye, O.C. Chemical composition and quality characteristics of wheat bread supplemented with leafy vegetable powders. J. Food Qual. 2017, 2017, 9536716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angioloni, A.; Collar, C. Suitability of oat, millet and sorghum in breadmaking. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 6, 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiano, A.; Viggiani, I.; Terracone, C.; Romaniello, R.; Del Nobile, M.A. Physical and sensory properties of bread enriched with phenolic aqueous extracts from vegetable waste. Czech J. Food Sci. 2015, 33, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawka, A.; Górecka, D. Comparison of chemical composition of wheat-oat and wheat-barley bread with sourdoughs fermented by ‘LV2’ starter. Food. Sci. Technol. Qual. 2010, 70, 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J.P.; Kaur, A.; Shevkani, K.; Singh, N.; Singh, B. Physicochemical characterisation of corn extrudates prepared with varying levels of beetroot (Beta vulgaris) at different extrusion temperatures. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulia, F.; Sunarharum, W.B. Beetroot (Beta vulgaris L. var. rubra L.) flour proportion and oven temperature affect the physicochemical characteristics of beetroot cookies. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 475, 012040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parafati, L.; Restuccia, C.; Palmeri, R.; Fallico, B.; Arena, E. Characterization of prickly pear peel flour as a bioactive and functional ingredient in bread preparation. Foods 2020, 9, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohajdova, Z.; Karovicova, J.; Kuchtova, V.; Laukova, M. Utilisation of beetroot powder for bakery applications. Chem. Papers 2018, 72, 1507–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.; Fei, Y.; Zhu, F. Physicochemical, structural and nutritional properties of steamed bread fortified with red beetroot powder and their changes during breadmaking process. Food Chem. 2022, 383, 132547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekmez, H.; Yilmaz, B.B. Quality and antioxidant properties of black carrot (Daucus carota ssp. sativus var. atrorubens Alef.) fiber fortified flat bread (Gaziantep Pita). J. Agric. Sci. Technol. B 2018, 8, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhikara, N.; Kushwaha, K.; Jaglan, S.; Sharma, P.; Panghal, A. Nutritional, physicochemical, and functional quality of beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) incorporated Asian noodles. Cereal Chem. 2019, 96, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazizi, S.; Montevecchi, G.; Antonelli, A.; Hamdi, M. Effects of prickly pear (Opuntia ficus-indica L.) peel flour as an innovative ingredient in biscuits formulation. LWT 2020, 124, 109155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).