Cephalometric Assessment and Long-Term Stability of Anterior Open-Bite Correction with Skeletal Anchorage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources

2.4. Search Strategy

2.5. Selection Process

2.6. Data Collection Process and Data Items

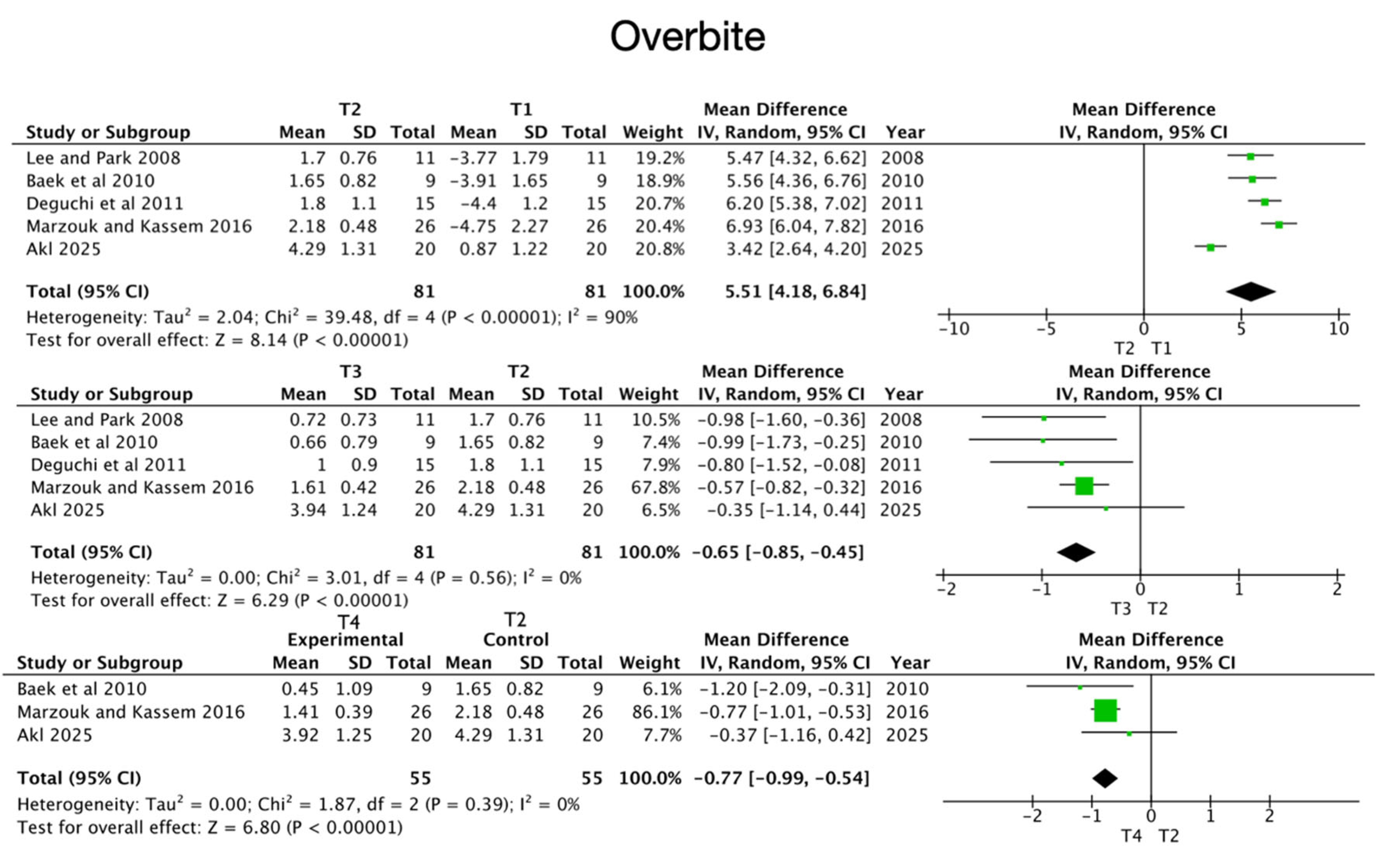

- Overbite;

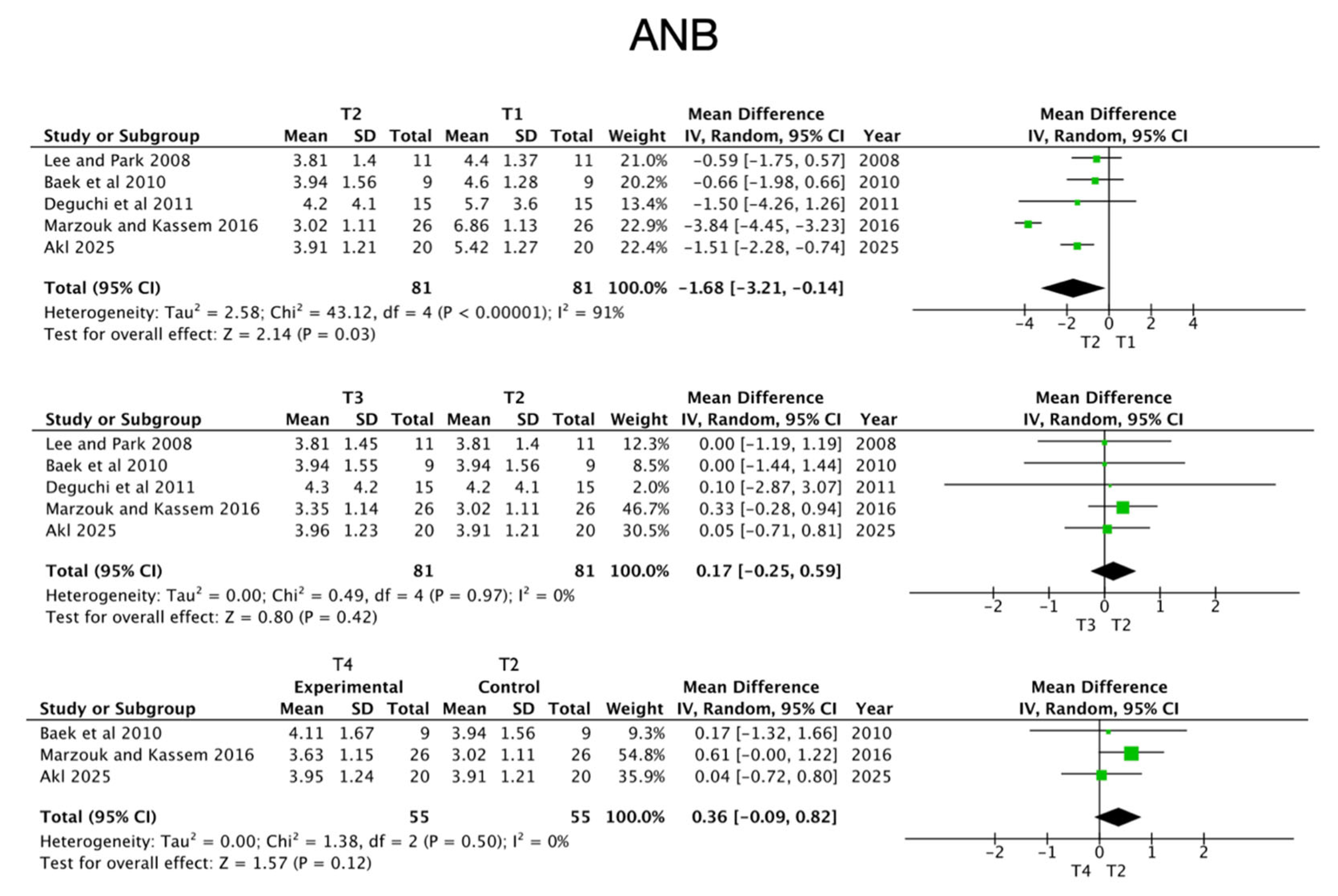

- ANB;

- N-Me;

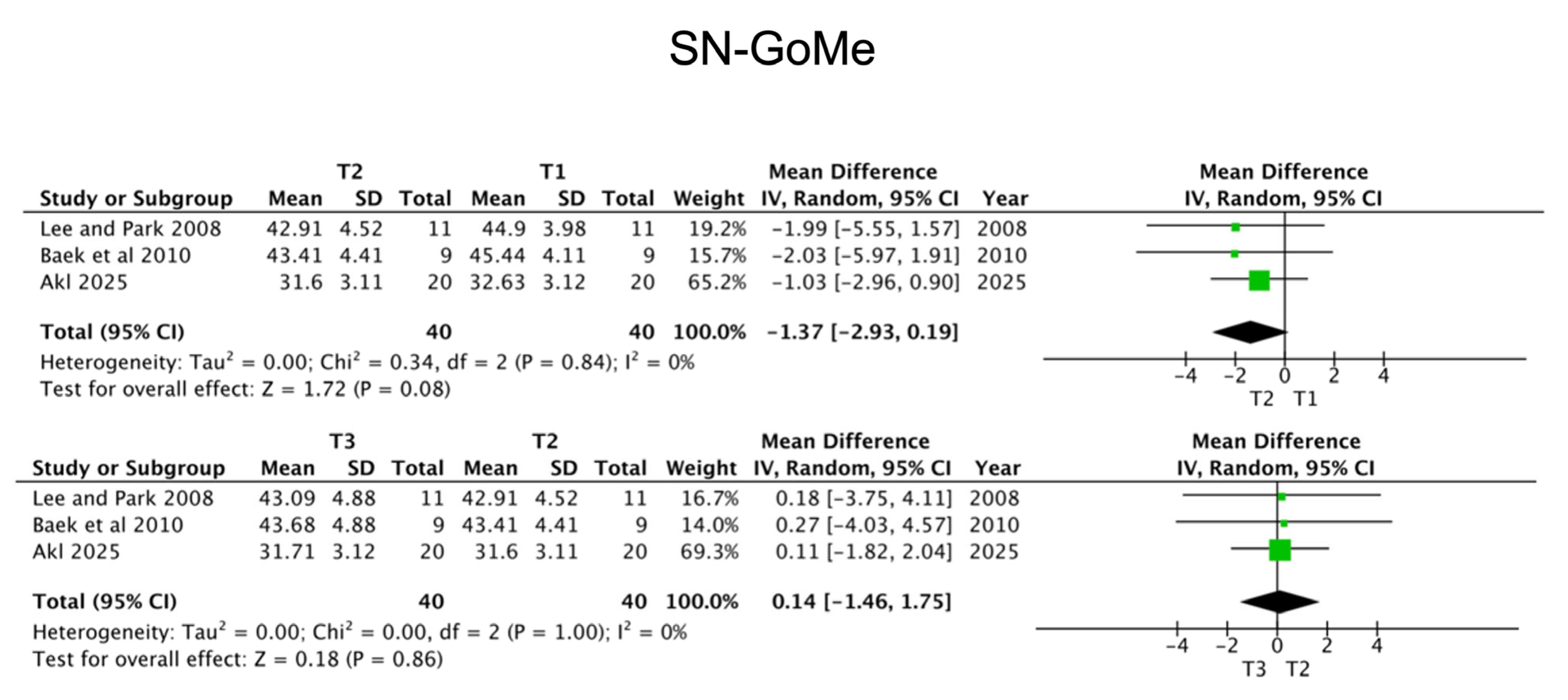

- SN-GoMe;

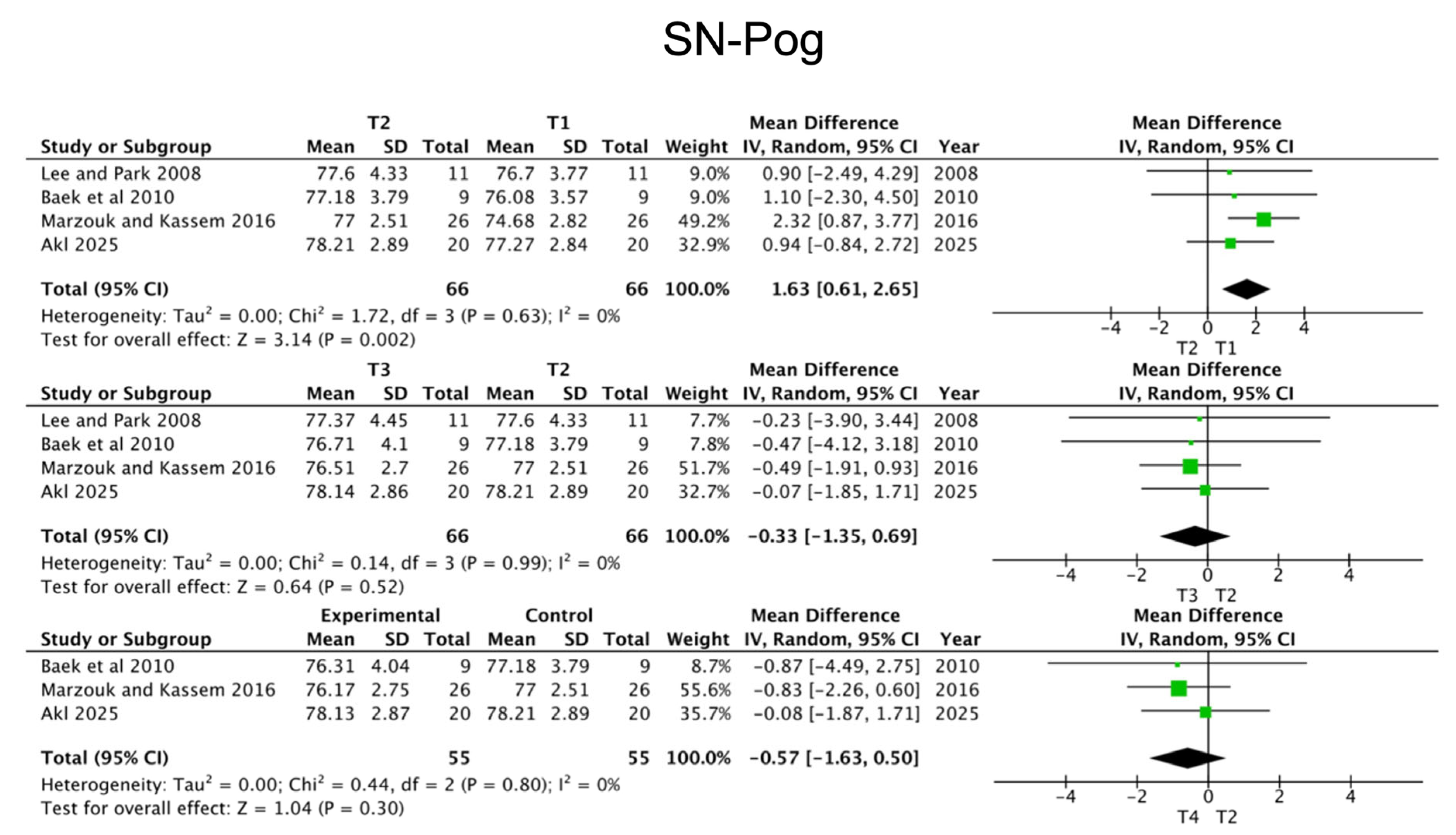

- SN-Pog;

- FMA.

2.7. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

2.8. Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of the Studies

3.3. Temporary Anchorage Devices—TADs

3.4. Assessment of Clinical Outcomes

3.5. Follow-Up Period

3.6. Cephalometric Outcomes

3.6.1. Sagittal Measurements

- SNA Angle: The angle between the Sella-Nasion (SN) plane and the Nasion-A point (NA) line, used to evaluate the anteroposterior position of the maxilla.

- SNB Angle: The angle between the SN plane and the Nasion-B point (NB) line, used to determine the sagittal position of the mandible.

- ANB Angle: Calculated as the difference between SNA and SNB angles; it is a key indicator of the skeletal sagittal relationship between the maxilla and the mandible.

3.6.2. Vertical Measurements

- Overbite: The vertical linear distance between the incisal edges of the lower central incisor (L1) and the upper central incisor (U1).

- SN-GoGn: The angle between the SN plane and the Gonion-Gnathion (GoGn) plane, used to assess mandibular plane inclination.

- SN-GoMe: The angle between the SN plane and the Gonion-Menton (GoMe) plane, another indicator of mandibular plane steepness.

- SN-Pog: The angle formed by the SN plane and the facial plane (Nasion-Pogonion), evaluating chin projection in relation to the cranial base.

- N-Me: The linear distance between Nasion (N) and Menton (Me), representing total anterior facial height.

- LAFH (Lower Anterior Facial Height): Linear measurement from Anterior Nasal Spine (ANS) to Menton (Me), representing the vertical dimension of the lower face.

3.6.3. Additional Measurements

- MMA (Maxillo-Mandibular Angle): The angle between the maxillary plane and the mandibular plane, indicating vertical skeletal divergence.

- FMA (Frankfort-Mandibular Plane Angle): The angle between the Frankfort horizontal plane and the mandibular plane (Go-Me), used as an indicator of facial growth direction.

3.7. Qualitative Assessment

3.8. Quantitative Synthesis

3.8.1. Short-Term Outcomes (T2–T1)

3.8.2. Medium-Term Outcomes (T3–T2)

3.8.3. Long-Term Outcomes (T4–T2)

3.9. Stability

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Molar Intrusion with TADs

4.2. Treatment Stability and Relapse Risk

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOB | Anterior Open Bite |

| AFH | Anterior Facial Height |

| LAFH | Lower Anterior Facial Height |

| TAFH | Total Anterior Facial Height |

| TAD | Temporary Anchorage Device |

| MSI | Miniscrew Implant |

| CBCT | Cone Beam Computed Tomography |

| FMA | Frankfort–Mandibular Plane Angle |

| SN-GoMe | Sella–Nasion to Gonion–Menton Angle |

| SN-GoGn | Sella–Nasion to Gonion–Gnathion Angle |

| SN-Pog | Sella–Nasion to Pogonion Angle |

| SNA | Sella–Nasion to Point A Angle |

| SNB | Sella–Nasion to Point B Angle |

| ANB | Point A–Nasion–Point B Angle |

| N-Me | Nasion to Menton (Total Anterior Facial Height) |

| MMA | Maxillo–Mandibular Angle |

| MP/FH | Mandibular Plane to Frankfort Horizontal Angle |

| IMPA | Incisor–Mandibular Plane Angle |

| U6–PP | Upper First Molar to Palatal Plane Distance |

| L6–MP | Lower First Molar to Mandibular Plane Distance |

| PFH | Posterior Facial Height |

| OP | Occlusal Plane |

| MPA | Mandibular Plane Angle |

| RPE | Rapid Palatal Expander |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| OSF | Open Science Framework |

| MINORS | Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| MD | Mean Difference |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| NR | Not Reported |

Appendix A

| Database | Search Query (Date Last Search: July 2025) | Results |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | “Open Bite” [Mesh] OR “anterior open bite” OR “openbite” OR “AOB” AND “Temporary Anchorage Devices” OR “skeletal anchorage” OR “TAD*” OR “miniscrew*” OR “mini-implant*” OR “miniplate*”AND “Cephalometry” [Mesh] OR cephalometric OR skeletal OR dentoalveolar OR “molar intrusion” OR “treatment stability” OR “follow-up” | 129 |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY((“anterior open bite” OR “openbite” OR “AOB”) AND (“Temporary Anchorage Devices” OR “skeletal anchorage” OR “TAD*” OR “miniscrew*” OR “mini-implant*” OR “miniplate*”) AND (cephalometric OR skeletal OR dentoalveolar OR “molar intrusion” OR “treatment stability” OR “follow-up”)) | 162 |

| Web of Science | TS = (“anterior open bite” OR “openbite” OR “AOB”) AND TS = (“Temporary Anchorage Devices” OR “skeletal anchorage” OR “TAD*” OR “miniscrew*” OR “mini-implant*” OR “miniplate*”) AND TS = (cephalometric OR skeletal OR dentoalveolar OR “molar intrusion” OR “treatment stability” OR “follow-up”) | 218 |

| Embase | (‘anterior open bite’/exp OR ‘openbite’ OR ‘AOB’) AND (‘temporary anchorage device’/exp OR ‘skeletal anchorage’ OR ‘TAD*’ OR ‘miniscrew*’ OR ‘mini-implant*’ OR ‘miniplate*’) AND (‘cephalometry’/exp OR cephalometric OR skeletal OR dentoalveolar OR ‘molar intrusion’ OR ‘treatment stability’ OR ‘follow-up’) | 543 |

| Cochrane | (“anterior open bite” OR “openbite” OR “AOB”) AND (“Temporary Anchorage Devices” OR “skeletal anchorage” OR “TAD*” OR “miniscrew*” OR “mini-implant*” OR “miniplate*”) AND (cephalometric OR skeletal OR dentoalveolar OR “molar intrusion” OR “treatment stability” OR “follow-up”) | 8 |

| LILACS | (“anterior open bite” OR “openbite” OR “AOB”) AND (“Temporary Anchorage Devices” OR “skeletal anchorage” OR “TAD*” OR “miniscrew*” OR “mini-implant*” OR “miniplate*”) AND (cephalometric OR skeletal OR dentoalveolar OR “molar intrusion” OR “treatment stability” OR “follow-up”) | 15 |

| Scielo | (“anterior open bite” OR “openbite” OR “AOB”) AND (“Temporary Anchorage Devices” OR “skeletal anchorage” OR “TAD*” OR “miniscrew*” OR “mini-implant*” OR “miniplate*”) AND (cephalometric OR skeletal OR dentoalveolar OR “molar intrusion” OR “treatment stability” OR “follow-up”) | 5 |

| Epistemonikos | (“anterior open bite” OR “openbite” OR “AOB”) AND (“Temporary Anchorage Devices” OR “skeletal anchorage” OR “TAD*” OR “miniscrew*” OR “mini-implant*” OR “miniplate*”) AND (cephalometric OR skeletal OR dentoalveolar OR “molar intrusion” OR “treatment stability” OR “follow-up”) | 80 |

| ScienceDirect | (“anterior open bite” OR “openbite” OR “AOB”) AND (“Temporary Anchorage Devices” OR “skeletal anchorage” OR “TAD*” OR “miniscrew*” OR “mini-implant*” OR “miniplate*”) AND (cephalometric OR skeletal OR dentoalveolar OR “molar intrusion” OR “treatment stability” OR “follow-up”) | 419 |

| Google Scholar | allintitle: “anterior open bite” “skeletal anchorage” cephalometric stability | 310 |

| Methodological Items for Non-Randomized Studies | Score * |

|---|---|

| ⋅ A clearly stated aim: the question addressed should be precise and relevant in the light of available literature ⋅ Inclusion of consecutive patients: all patients potentially fit for inclusion (satisfying the criteria for inclusion) have been included in the study during the study period (no exclusion or details about the reasons for exclusion). ⋅ Prospective collection of data: data were collected according to a protocol established before the beginning of the study ⋅ Endpoints appropriate to the aim of the study: unambiguous explanation of the criteria used to evaluate the main outcome, which should be in accordance with the question addressed by the study. Also, the endpoints should be assessed on an intention-to-treat basis. ⋅ Unbiased assessment of the study endpoint: blind evaluation of objective endpoints and double-blind evaluation of subjective endpoints. Otherwise, the reasons for not blinding should be stated. ⋅ Follow-up period appropriate to the aim of the study: the follow-up should be sufficiently long to allow the assessment of the main endpoint and possible adverse events. ⋅ Loss to follow up less than 5%: all patients should be included in the follow up. Otherwise, the proportion lost to follow up should not exceed the proportion experiencing the major endpoint. ⋅ Prospective calculation of the study size: information of the size of detectable difference in interest, with a calculation of 95% confidence interval, according to the expected incidence of the outcome event, and information about the level for statistical significance and estimates of power when comparing the outcomes. | |

| Additional criteria in the case of comparative study | |

| ⋅ An adequate control group: having a gold standard diagnostic test or therapeutic intervention recognized as the optimal intervention according to the available published data. ⋅ Contemporary groups: control and studied group should be managed during the same period (no historical comparison). ⋅ Baseline equivalence of groups: the groups should be similar regarding the criteria other than the studied endpoints. Absence of confounding factors that could bias the interpretation of the results. ⋅ Adequate statistical analyses: whether the statistics were in accordance with the type of study with calculation of confidence intervals or relative risk. |

References

- Rodriguez-Huaringa, J.E.; Vargas-Mori, G.X.J.; Arriola-Guillén, L.E. Influence of Anterior Open Bite on Oral Health-Related Quality of Life. A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2025, 17, e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprioglio, A.; Fastuca, R. Etiology and Treatment Options of Anterior Open Bite in Growing Patients: A Narrative Review. Orthod. Fr. 2016, 87, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Gavito, G.; Wallen, T.R.; Little, R.M.; Joondeph, D.R. Anterior Open-Bite Malocclusion: A Longitudinal 10-Year Postretention Evaluation of Orthodontically Treated Patients. Am. J. Orthod. 1985, 87, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestrini-Biavati, A.; Salamone, S.; Silvestrini-Biavati, F.; Agostino, P.; Ugolini, A. Anterior Open-Bite and Sucking Habits in Italian Preschool Children. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2016, 17, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Pisani, L.; Bonaccorso, L.; Fastuca, R.; Spena, R.; Lombardo, L.; Caprioglio, A. Systematic Review for Orthodontic and Orthopedic Treatments for Anterior Open Bite in the Mixed Dentition. Prog. Orthod. 2016, 17, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González Espinosa, D.; de Oliveira Moreira, P.E.; da Sousa, A.S.; Flores-Mir, C.; Normando, D. Stability of Anterior Open Bite Treatment with Molar Intrusion Using Skeletal Anchorage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Prog. Orthod. 2020, 21, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodoridou, M.Z.; Zarkadi, A.E.; Zymperdikas, V.F.; Papadopoulos, M.A. Long-Term Effectiveness of Non-Surgical Open-Bite Treatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Prog. Orthod. 2023, 24, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrillo, M.; Nucci, L.; Gallo, V.; Bruni, A.; Montrella, R.; Fortunato, L.; Giudice, A.; Perillo, L. Temporary Anchorage Devices in Orthodontics: A Bibliometric Analysis of the 50 Most-Cited Articles from 2012 to 2022. Angle Orthod. 2023, 93, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, H.; Numazaki, K.; Oyanagi, T.; Seiryu, M.; Ito, A.; Noguchi, T.; Ohori, F.; Yoshida, M.; Fukunaga, T.; Kitaura, H.; et al. Three-Dimensional Evaluation of Treatment Effects and Post-Treatment Stability of Maxillary Molar Intrusion Using Temporary Anchorage Devices in Open Bite Malocclusion. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Lancero, P.; Ibor-Miguel, M.; Marqués-Martínez, L.; Boo-Gordillo, P.; García-Miralles, E.; Guinot-Barona, C. Correction of Anterior Open Bite Using Temporary Anchorage Devices: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J.; Suh, H.; Park, J.J.; Park, J.H. Anterior Open Bite Correction via Molar Intrusion: Diagnosis, Advantages, and Complications. J. World Fed. Orthod. 2024, 13, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkkahraman, H.; Sarioglu, M. Are Temporary Anchorage Devices Truly Effective in the Treatment of Skeletal Open Bites? Eur. J. Dent. 2016, 10, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malara, P.; Bierbaum, S.; Malara, B. Outcomes and Stability of Anterior Open Bite Treatment with Skeletal Anchorage in Non-Growing Patients and Adults Compared to the Results of Orthognathic Surgery Procedures: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aifa, A.; Sorel, O.; Gebeile-Chauty, S. L’infraclusie Chez l’hyperdivergent: Impaction de Le Fort I versus Ingression Molaire Maxillaire Par Ancrage Osseux. Une Revue de La Littérature. Orthod. Fr. 2021, 92, 215–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, S.; Sakai, Y.; Tamamura, N.; Deguchi, T.; Takano-Yamamoto, T. Treatment of Severe Anterior Open Bite with Skeletal Anchorage in Adults: Comparison with Orthognathic Surgery Outcomes. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2007, 132, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, F.A.; Oltramari, P.V.P.; De Almeida, M.R.; De Conti, A.C.C.F.; De Almeida, R.R.; Fernandes, T.M.F. Stability of Early Anterior Open Bite Treatment: A 2-Year Follow-up Randomized Clinical Trial. Braz. Dent. J. 2021, 32, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunta, O.; Filip, I.; Garba, C.; Colceriu-Simon, I.M.; Olteanu, C.; Festila, D.; Ghergie, M. Tongue Behavior in Anterior Open Bite—A Narrative Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, P.; Petrisor, B.A.; Farrokhyar, F.; Bhandari, M. Research Questions, Hypotheses and Objectives. Can. J. Surg. 2010, 53, 278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Slim, K.; Nini, E.; Forestier, D.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Panis, Y.; Chipponi, J. Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (Minors): Development and Validation of a New Instrument. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, J.; Baik, U.; Umemori, M.; Takahashi, I.; Nagasaka, H.; Kawamura, H.; Mitani, H. Treatment and Posttreatment Changes Following Intrusion of Mandibular Molars with Application of a Skeletal Anchorage System (SAS) for Open Bite Correction. Int. J. Adult Orthodon Orthognath. Surg. 2002, 17, 243–253. [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood, K.H.; Burch, J.G.; Thompson, W.J. Closing Anterior Open Bites by Intruding Molars with Titanium Miniplate Anchorage. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2002, 122, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erverdi, N.; Keles, A.; Nanda, R. The Use of Skeletal Anchorage in Open Bite Treatment: A Cephalometric Evaluation. Angle Orthod. 2004, 74, 381–390. [Google Scholar]

- Erverdi, N.; Usumez, S.; Solak, A.; Koldas, T. Noncompliance Open-Bite Treatment with Zygomatic Anchorage. Angle Orthod. 2007, 77, 986–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xun, C.; Zeng, X.; Wang, X. Microscrew Anchorage in Skeletal Anterior Open-Bite Treatment. Angle Orthod. 2007, 77, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.A.; Park, Y.C. Treatment and Posttreatment Changes Following Intrusion of Maxillary Posterior Teeth with Miniscrew Implants for Open Bite Correction. Korean J. Orthod. 2008, 38, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seres, L.; Kocsis, A. Closure of Severe Skeletal Anterior Open Bite with Zygomatic Anchorage. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2009, 20, 478–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, M.S.; Choi, Y.J.; Yu, H.S.; Lee, K.J.; Kwak, J.; Park, Y.C. Long-Term Stability of Anterior Open-Bite Treatment by Intrusion of Maxillary Posterior Teeth. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2010, 138, 396.e1–396.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschang, P.H.; Carrillo, R.; Rossouw, P.E. Orthopedic Correction of Growing Hyperdivergent, Retrognathic Patients with Miniscrew Implants. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 69, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deguchi, T.; Kurosaka, H.; Oikawa, H.; Kuroda, S.; Takahashi, I.; Yamashiro, T.; Takano-Yamamoto, T. Comparison of Orthodontic Treatment Outcomes in Adults with Skeletal Open Bite between Conventional Edgewise Treatment and Implant-Anchored Orthodontics. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2011, 139, S60–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akan, S.; Kocadereli, I.; Aktas, A.; Tasar, F. Effects of Maxillary Molar Intrusion with Zygomatic Anchorage on the Stomatognathic System in Anterior Open Bite Patients. Eur. J. Orthod. 2013, 35, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffler, N.R.; Proffit, W.R.; Phillips, C. Outcomes and Stability in Patients with Anterior Open Bite and Long Anterior Face Height Treated with Temporary Anchorage Devices and a Maxillary Intrusion Splint. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2014, 146, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foot, R.; Dalci, O.; Gonzales, C.; Tarraf, N.E.; Darendeliler, M.A. The Short-Term Skeleto-Dental Effects of a New Spring for the Intrusion of Maxillary Posterior Teeth in Open Bite Patients. Stat. Pap. 2014, 15, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, T.F.M.; Nakao, C.Y.; Gonçalves, J.R.; Santos-Pinto, A. Maxillary Molar Intrusion with Zygomatic Anchorage in Open Bite Treatment: Lateral and Oblique Cephalometric Evaluation. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 19, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, T.R.; Cousley, R.R.J.; Fishman, L.S.; Tallents, R.H. Dentoskeletal Changes Following Mini-Implant Molar Intrusion in Anterior Open Bite Patients. Angle Orthod. 2015, 85, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzouk, E.S.; Abdallah, E.M.; El-Kenany, W.A. Molar Intrusion in Open-Bite Adults Using Zygomatic Miniplates. Int. J. Orthod. Milwaukee 2015, 26, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Marzouk, E.S.; Kassem, H.E. Evaluation of Long-Term Stability of Skeletal Anterior Open Bite Correction in Adults Treated with Maxillary Posterior Segment Intrusion Using Zygomatic Miniplates. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2016, 150, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akl, H.E.; Abouelezz, A.M.; El Sharaby, F.A.; El-Beialy, A.R.; El-Ghafour, M.A. Force Magnitude as a Variable in Maxillary Buccal Segment Intrusion in Adult Patients with Skeletal Open Bite: A Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Angle Orthod. 2020, 90, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbaydogan, L.C.; Akin, M. Cephalometric Evaluation of Intrusion of Maxillary Posterior Teeth by Miniscrews in the Treatment of Open Bite. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2022, 161, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akl, H.E.; Abouelezz, A.M.; El Sharaby, F.A.; Abd-El-Ghafour, M.; El-Beialy, A.R. Is Mandibular Posterior Dento-Alveolar Intrusion Essential in Treatment of Skeletal Open Bite in Adult Patients? A Single Center Randomized Clinical Trial. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamberland, S.; Nataf, N. Noninvasive Conservative Management of Anterior Open Bite Treated with TADs versus Clear Aligner Therapy. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenlee, G.M.; Huang, G.J.; Chen, S.S.H.; Chen, J.; Koepsell, T.; Hujoel, P. Stability of Treatment for Anterior Open-Bite Malocclusion: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2011, 139, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaghlouth, B.; Almubarak, A.; Almaghlouth, I.; Alkhalifah, R.; Alsadah, A.; Hassan, A. Orthodontic Intrusion Using Temporary Anchorage Devices Compared to Other Orthodontic Intrusion Methods: A Systematic Review. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2021, 13, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, H.O.; Gharechahi, M.; Ghanbarzadeh, M.; Nikkhaah Raankoohi, A.; Dastmalchi, P. Evaluation of Periodontal Condition in Intruded Molars Using Miniscrews. J. Dent. Mater. Tech. 2015, 4, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayani, S.; Heravi, F.; Radvar, M.; Anbiaee, N.; Madani, A.S. Periodontal Changes Following Molar Intrusion with Miniscrews. Dent. Res. J. 2015, 12, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | − Studies including patients aged ≥12 years with permanent dentition (The age limit ≥18 years, was chosen for the quantitative analysis to minimize residual growth effects that could confound cephalometric changes). − Studies involving a homogeneous group of patients with anterior open bite | − In vitro studies − Animal studies − Studies involving patients with cleft lip/palate or other craniofacial anomalies − Studies including patients with systemic diseases or craniofacial syndromes |

| Intervention | − Anterior open bite treated with skeletal anchorage devices | − Studies not specifying the type of anchorage device − Studies with less than 6 months of post-retention follow-up |

| Comparison | − Studies assessing pre- and post-treatment outcomes | |

| Outcomes | − Cephalometric changes related to anterior open-bite correction | − Studies without cephalometric evaluation |

| Type of included Studies | − Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) − Non-randomized studies: prospective or retrospective (Given the limited number of randomized controlled trials in this field, both prospective and retrospective designs were included to capture the full scope of available clinical evidence). | − Case reports − Reviews and meta-analyses − Non-English articles − Letters to the editor or commentaries |

| Author and Year of Publication | Study Design | Comparison | Sample Size | Age | Gender Distribution | Treatment Time | Method of Measurement | Devices Used | Force Applied | Maxillary or Mandibular Application of Devices | Follow Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sugawara et al. (2002) [20] | Retrospective Study | T0 (Pre-treatment) T1 (Treated with miniplates) | 9 patients | 13.3 to 28.9 years (Mean 21.1) | 2 males 7 females | 9 to 22 months (Average 14.9 months) | Dental cast analysis Panoramic analysis Lateral cephalometric analysis | L-shaped Miniplates | Not available | Mandibular | 12 months |

| Sherwood et al. (2002) [21] | Retrospective Study | T0 (Pre-treatment) T1 (Treated with miniplates) | 4 adult patients | NR * | 2 men 2 women | 5.5 months (Mean) | Lateral cephalometric analysis Panoramic radiographs | Miniplates | Not available | Maxillary and mandibular | NR * |

| Erverdi et al. (2004) [22] | Prospective Study | T0 (Pre-treatment) T1 (Treated with miniplates) | 10 patients | 17–23 years | 5.1 months | PA radiograph analysis Lateral cephalometric analysis | I-shaped-miniplates Sectional wire in upper posterior segment | Not available | Maxillary | NR * | |

| Erverdi et al. (2007) [23] | Prospective Longitudinal Study | T0 (Pre-treatment) T1 (Treated with miniplate and acrylic plates) | 11 patients | 19.5 years (mean) | 5 males 6 females | 9.6 months | Lateral cephalometric analysis | I-shaped miniplates in upper posterior segment | 400 g per side | Maxillary | NR * |

| Xun et al. (2007) [24] | Retrospective Study | T0 (Pre-treatment) T1 (Treated with miniscrews) | 12 patients | 18.7 years (mean) | 6.8 months | Lateral cephalometric analysis | Midpalatal miniscrew in upper arch Buccal miniscrews in lower molars | 150 g per side | Maxillary and mandibular | NR * | |

| Kuroda et al. (2007) [15] | Prospective Clinical Trial | Comparison of two groups G1: treated with miniplates or miniscrews G2: Treated with orthognathic surgery | 10 patients (G1) 13 patients (G2) | 16–46 years 21.6 years (Mean) | 4 males 9 females | G1: 19–36 months (27.6 months average) G2: 20–44 months (33.5 months average) | Lateral cephalometric analysis | G1: TADs sectional wire in upper and lower posterior segment G2: LeFort 1 osteotomy and intraoral vertical ramus osteotomy or sagittal split ramus osteotomy | G1: 150 g G2: Not declared | Maxillary and mandibular | NR * |

| Lee HA, and Park YC (2008) [25] | Prospective Longitudinal study | Pre-treatment group and post-treatment group treated with miniscrews | 11 patients | 18.2–31.1 years 23.3 years (mean) | 1 male 10 females | 5.4 months | Lateral cephalometric analysis | Miniscrews placed buccally in the upper jaw with a splint to prevent molar tipping and a sectional wire in upper posterior segment | Not available | Maxillary | 17.4 months |

| Seres and Kocsis (2009) [26] | Retrospective study | Pre-treatment group and post-treatment group treated with miniplates only | 7 patients | 15–29 years (mean 21) | 3 males 4 females | 6 months (Mean) | Lateral cephalometric analysis Posteroanterior cephalometric analysis Orthopantomograms Periapical radiographs | Miniplates Coil Springs | 100–120 g per side | Maxillary | NR * |

| Baek et al. (2010) [27] | Retrospective Study | Pre-treatment group and post-treatment group treated with miniscrew implants only | 9 patients | 18.3–31.1 years (Mean 23.7 years) | 8 women 1 man | Mean treatment time 5.4 months Mean retention period 41 months (range 36–51 months) | Lateral cephalometric analysis | Miniscrew implants Elastomeric chains Rigid transpalatal arches | NA | Maxillary | 3 years |

| Buschang et al. (2011) [28] | Prospective study | Pre-treatment group and post-treatment group treated with miniscrews | 9 patients | 13.2 years (mean) | 1 male 8 females | 1.4 to 2.5 years (average 1.9 years) | Lateral cephalometric analysis | MSIs miniscrews implants in upper molars associated with RPE MSI in lower molars | 150 g per side | Maxillary and mandibular | NR * |

| Deguchi et al. (2011) [29] | Retrospective Longitudinal Clinical Trial | Comparison of two groups: G1 (non-implant) treated with anterior elastics, high-pull headgear, and MEAW G2 (implant) treated with skeletal anchorage | G1: 15 patients G2: 15 patients | G1: 22.9 ± 0.9 years G2: 25.7 ± 6.4 years | 15 females G1 15 females G2 | G1: 1–3 years G2: 1–3 years | Cast analysis PAR and DI scores Lateral cephalometric analysis | G1: High-pull headgear; MEAW; Elastics G2: Mini-implants | Not available | 24 months | |

| Akan et al. (2013) [30] | Prospective study | Pre-treatment group and post-treatment group treated with miniplates and acrylic plates | 19 patients | 17.7 years (mean) | 6 males 13 females | 6.8 months | PA Radiograph EMG and EVG recording Lateral cephalometric analysis | Miniplates in upper molars | 400 g per side | Maxillary | NR * |

| Scheffler et al. (2014) [31] | Retrospective Longitudinal study | Pre-treatment group and post-treatment group treated with miniplates and miniscrews and acrylic plates | 30 patients | 12.7 to 48.1 years 24.1 years (mean) | 11 males 19 females | 3.6–9.6 months for intrusion 6–33 months total treatment time | Lateral cephalometric analysis | Miniscrews (16 patients) Miniplates (14 patients) Acrylic plates | 150 g per side | Maxillary | More than 2 years |

| Foot et al. (2014) [32] | Prospective study | Pre-treatment group and post-treatment group treated with miniscrews and acrylic plates | 16 patients | 12.2 to 14.3 years 13.1 (Mean) | 4 males 12 females | 2.5 to 7.7 months (average 4.91 months) | Cone beam Lateral cephalometric analysis | Sydney intrusion spring in upper posterior segment | 500 g per side | Maxillary | NR * |

| De Oliveira et al. (2014) [33] | Prospective study | Pre-treatment group and post-treatment group treated with miniplates | 9 patients | 18.7 ± 5.1 years (Mean) | 6 females 3 males | 6 months approximately | Lateral and oblique cephalometric analysis | Miniplates and transpalatal arches | 450–500 g per side on each molar | Maxillary | NR * |

| Hart et al. (2015) [34] | Retrospective study | Pre-treatment group and post-treatment group treated with palatal miniscrews | 31 patients: 21 adolescents 10 adult patients | 12.6 to 55.5 years 20.7 years (mean) | 10 males 21 females | 1.3 years | Lateral cephalometric analysis | Bilateral perimolar palatal miniscrew (25p) and midpalatal mini-implants (6) in upper arch | Not declared | Maxillary | NR * |

| Marzouk et al. (2015) [35] | Prospective study | Pre-treatment group and post-treatment group treated with miniplates | 13 patients | 16 years 2 months–22 years 9 months (mean age 18 years, 8 months ± 2 years, 2 months) | 9 females 4 males | 9 months ± 2.5 months | Lateral and postero-anterior cephalometric analysis | Miniplates in association with a double TPA and NiTi coil springs | 450 g per side | Maxillary | NR * |

| Marzouk and Kassem (2016) [36] | Prospective study | Pre-treatment group and post-treatment group treated with miniplates only | 26 patients | 19 years 4 months –26 years 11 months (22 years 5 months mean) | 15 women 11 men | 24–28 months (mean 26.2 months) | Lateral cephalometric analysis | Miniplates | 150 g per molar 75 g per premolar per side | Maxillary | 4 years |

| Turkkahra man and Sarioglu (2016) [12] | Prospective study Controlled trial | Treatment group with miniplates and control group | Treatment group (TG): 20 patients Control group (CG): 20 patients | TG: 16.68 ± 2.8 years CG: 16.63 ± 2.83 years | TG: 14 females 6 males CG: 11 females 9 males | TG: 1 ± 0.31 years CG: 0.95 ± 0.14 years | Lateral cephalometric analysis Dental cast analysis Total and local structural superimposition method of Björk and Skieller | Miniplates and a rigid hyrax appliance NiTi coil springs | 200 g on the posterior teeth | Maxillary | NR * |

| Akl et al. (2020) [37] | Randomized controlled trial | Treatment group with 400 g force application and control group with 200 g force application | Treatment group (TG): 11 patients Control group (CG): 11 patients | Control 19.22 ± 1.45 years Intervention 18.95 ± 1.77 years | NA | 6 months | CBCT | Miniscrews Closed Ni-Ti Coil Spring | 200 g for the comparator group 400 g for the intervention group | Maxillary | NR * |

| Akbaydogan and Akin (2021) [38] | Prospective study | Pre-treatment group and post- treatment group treated with miniscrews and maxillary occlusal splints | 20 patients | 14.71 ± 1.77 years | 14 females 6 males | 8 months | Lateral cephalometric analysis | Palatal miniscrews Elastic chains Acylic plates | 250 g per side | Maxillary | NR * |

| Akl et al. (2025)[39] | Randomized controlled clinical trial | Two groups: G1 treated with 400 g force application vs. G2 treated with 200 g force application | G1: 20 patients—G2: 20 patients | Mean 19.8 ± 2.4 years | 27 females, 13 males | 3 years post-treatment | Lateral cephalometric radiographs before treatment, after intrusion, and at 6-month follow-up | Titanium miniscrews with intrusion mechanics | 200 g or 400 g per side | Maxillary posterior teeth | 6 months post-treatment |

| Author and Year of Publication | Reduction in Open Bite | Effect on Mandibular Autorotation | Effect on Cephalometric Variables | Outcomes Assessed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sugawara et al. (2002) [20] | Increase in overbite by 4.9 mm | Counterclockwise rotation of the mandible Reduction in FH/MP by 1.3° | Reduction in ALFH Reduction in interlabial gap Improvement of AP jaw relations Stable profile after 1 year SNA reduction SNB increase ANB reduction | Overbite MP/FH LAFH U6-PP L6-MP SNA SNB ANB |

| Sherwood et al. (2002) [21] | Overbite increased by 3–4.5 mm (3.62 mm mean) | Counterclockwise rotation of the mandible SN-MP reduction SN-OP reduction N-S-Gn reduction | N-Me reduction Reduction in AFH Increase in SNB Reduction in N-S-Gn | Overbite SN-MP SN-OP N-S-Gn N-Me SNB |

| Erverdi et al. (2004) [22] | Increase in overbite by 3.7 mm | Reduction in Go Gn/SN by 1.7° Counterclockwise rotation of the mandible | Reduction in AFH Increase in glabella- SN-Pog Improvement of smile and profile SNA increase SNB increase ANB reduction | Overbite GoGn/SN U6-PP L6-MP SNA SNB ANB |

| Erverdi et al. (2007) [23] | Increase in overbite by 5.1 mm | Reduction in Go Gn/SN by 3° Counterclockwise rotation of the mandible | Reduction in LAFH Increase in SNA Increase in SNB Reduction in ANB | Overbite GoGn/SN LAFH U6-PP SNA SNB ANB |

| Xun et al. (2007) [24] | Increase in overbite by 4.2 mm | Reduction in Me Go/SN by 2.3° Counterclockwise rotation of the mandible | Reduction in AFH Reduction in LAFH Reduction in Ns-Sn-Pos Improvement of convex profile SNA Reduction SNB Increase ANB Reduction | Overbite MeGo/SN LAFH U6-PP L6-MP SNA SNB ANB |

| Kuroda et al. (2007) [15] | G1: Increase in overbite by 6.8 mm G2: Increase in overbite by 7 mm | G1: Counterclockwise rotation of the mandible Reduction in FH/MP by 3.3° G2: Counterclockwise rotation of the mandible Reduction in FH/MP by 0.3° | G1: Reduction in TAFH and LAFH Overall better facial improvement than with surgery G2: Reduction in TAFH LAFH unchanged | Overbite MP/FH LAFH U6-PP L6-MP SNA SNB ANB |

| Lee HA, and Park YC (2008) [25] | Increase in overbite by 5.47 mm | Counterclockwise rotation of the mandible Reduction in Me Go/SN by 1.99° Increase of by 0.9° | Reduction in AFH Forward shift in pogonion by 2.17 mm Esthetic improvement of overall facial appearance Increase in AFH by 0.38 mm after 17.4 month of retention Increase in SNB Reduction in ANB | Overbite MeGo/SN SN-Pog MP/FH AFH U6-PP SNB ANB FMA |

| Seres and Kocsis (2009) [26] | Complete correction | Autorotoation of the mandible The mandibular plane closed by an average of 3.1° Point B rotated anteriorly and upwards | AFH decreased Facial profile improved significantly | AFH Facial profile Mandible rotation Mandibular plane angle Point B position |

| Baek et al. (2010) [27] | 5.56 ± 1.94 mm | Counterclockwise rotation of the mandible SN-GoMe reduction by 2.03° SN-Pog Increase by 1.1° | AFH reduction ANB reduction FMA reduction Forward and upward movement of point B and Po | SN-GoMe SN-Pog FMA AFH Overbite IMPA U6-PP ANB |

| Buschang et al. (2011) [28] | Not declared | Reduction in MPA by 3.9° Counterclockwise rotation of the mandible | Chin moved forward by 2.4 mm Increase in SNB Reduction in facial convexity | MPA SNB |

| Deguchi et al. (2011) [29] | G1: Increase in overbite by 6.5 mm G2: Increase of overbite by 6.2 mm | G1: Increase in MP/SN by 2.7° Clockwise rotation of the mandible G2: Reduction in MP/SN by 3.6° Counterclockwise rotation of the mandible | G1: Increase in AFH and reduction in facial convexity and lips protrusion G2: Reduction in AFH reduction in facial convexity (more than G1) and reduction in lips protursion Disappearance of incompetent lips | Overbite MeGo/SN LAFH U6-PP L6-MP SNA SNB ANB |

| Akan et al. (2013) [30] | Increase in overbite by 4.79 mm | Reduction in Go Gn/SN by 3.79° Counterclockwise rotation of the mandible | Increase in SNB Reduction in LAFH Reduction in AFH Reduction in facial convexity Increase in upper lip/E plane SNA Reduction SNB Increase ANB Reduction | Overbite MP/FH GoGn/SN LAFH U6-HL L6-MP SNA SNB ANB |

| Scheffler et al. (2014) [31] | Increase in overbite by 2.2 mm | Reduction in Go Gn/SN by 1.2° Counterclockwise rotation of the mandible | Reduction in LAFH | Overbite GoGn/SN |

| Foot et al. (2014) [32] | Overbite increase by 3 mm | Reduction in MP/SN by 1.2° Counterclockwise rotation of the mandible | Reduction in LAFH Reduction in G′SnPo′ Increase in SNA Increase in SNB Reduction in ANB | Overbite MP/FH MMA GoGn/SN LAFH U6-PP L6-MP SNA SNB ANB |

| De Oliveira et al. (2014) [33] | NA | Counterclockwise rotation of the mandible (1.57°) The occlusal plane showed a clockwise rotation of 4.27° SN-GoMe reduction by 1.57° | N-Me reduction PFH unchanged SN^ANS-PNS reduction SN-GoMe reduction SN^McUIi increase | N-Me SN^GoMe OcPl angle |

| Hart et al. (2015) [34] | Increase in overbite by 3.8 mm | Reduction in FH/MP by 1.1° Counterclockwise rotation of the mandible | Reduction in LAFH Reduction in AFH Reduction in PFH Reduction in SNA Increase in SNB Reduction in ANB | Overbite MP/FH LAFH U6-PP U6-BaH L6-MP SNA SNB ANB |

| Marzouk et al. (2015) [35] | 6.55 ± 1.83 mm | Counterclockwise rotation of the mandible MP-SN decrease by 1.6° SN-Pog increase by 1.6° Increase in L1-FHP angle by 1.4° Increase in interincisal angle by 3.7° | SNB increase ANB decrease N-S-Gn decrease N-A-Pog decrease N-Me reduction ANS-Me reduction SN-OP increase N′-Sn-Pog′ reduction Interincisal angle increase Improvement in facial soft tissue convexity Overjet reduction Forward and upward displacement of B point and pogonion Reduction in mandibular plane angle | N-Me ANS-Me MP-SN angle SN-Pog N-S-Gn angle U6 to PP OP-SN Overbite Interincisal angle Soft tissue facial convexity N′-Sn-Pog′ angle SNB ANB |

| Marzouk and Kassem (2016) [36] | 6.93 mm SD1.99 mm | Counterclockwise rotation of the mandible SN-MP Reduction SN-Pog Increase N-S-Gn Reduction | AFH reduction SNA reduction SNB increase ANB reduction MMA reduction Forward and upward movement of point B and Po Reduction in facial convexity Improvement in the patient’s appearance | Overbite AFH LAFH Convexity angle SN-Mp SN-Pog N-S-Gn U6-PP L6-MP N′-Sn-Pog′ SNA SNB ANB |

| Turkkahra man and Sarioglu (2016) [12] | 4.82 ± 1.53 mm | Counteclockwise rotation of the mandible Posterior rotation of the occlusal plane Reduction in SN/GoGn by 2.25° Increase in SN/OccP by 3.42° | TAFH Reduction LAFH Reduction Upward and forward movement of the chin Improvement of maxillary-mandibular discrepancy Anterior rotation of the mandible Increase in intermolar width Increase in interpremolar width | SN/GoGn Overbite SN/OccP N-Me S-Go/N-Me |

| Akl et al. (2020) [37] | Treatment group 5.75 ± 1.87 mm Comparator group 5.01 ± 0.93 mm | Counterclockwise rotation of posterior segment | UR4/FH-UR4/MSP UR5/FH-UR5/MSP UR6/FH-UR6/MSP UR7/FH-UR7/MSP UL4/FH-UL4/MSP UL5/FH-UL5/MSP UL6/FH-UL6/MSP UL7/FH-UL7/MSP UR/FH-UR/MSP UL/FH-UL/MSP LR4 center-MP LR5 center-MP LR6 fur-MP LR7 fur-MP LL4 center-MP LL5 center-MP LL6 fur-MP LL7 fur-MP | |

| Akbaydogan and Akin (2021) [38] | Overbite increased by 5.81 ± 0.97 mm | Counterclockwise rotation SN/GoGn decreased by 2.7° | AFH reduction LAFH reduction Midfacial height reduction Convexity angle reduction SNA Reduction SNB Increase ANB Reduction | Overbite AFH LAFH Midfacial height Convexity Angle SNA SNB ANB |

| Akl et al. (2025) [39] | Significant overbite increase in both groups, greater with 400 g | Counterclockwise mandibular rotation in both groups | Significant changes in SNA, SNB, ANB, MP/SN, LAFH; greater effects with higher force magnitude | Overbite correction, mandibular rotation, skeletal and dental positional changes, stability |

| Author and Year of Publication | 1. A Clear Stated Aim | 2. Inclusion of Consecutive Patients | 3. Prospective Collection of Data | 4. Endpoints Appropriate to the Aim of the Study | 5. Unbiased Assessment of the Study Endpoint | 6. Follow-Up Period Appropriate | 7. Loss to Follow-Up Less Than 5% | 8. Prospective Calculation of the Study Size | 9. An Adequate Control Group | 10. Contemporary Groups | 11. Baseline Equivalence of Group | 12. Adequate Statistical Analysis | Total Score | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sugawara et al. (2002) [20] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 11 | Average |

| Sherwood et al. (2002) [21] | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | Low |

| Erverdi et al. (2004) [22] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | Low |

| Erverdi et al. (2007) [23] | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | Low |

| Xun et al. (2007) [24] | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | Low |

| Kuroda et al. (2007) [15] | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 12 | Average |

| Lee HA, and Park YC (2008) [25] | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 10 | Low |

| Seres and Kocsis (2009) [26] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | Low |

| Baek et al. (2010) [27] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 12 | Average |

| Buschang et al. (2011) [28] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | Low |

| Deguchi et al. (2011) [29] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 18 | High |

| Akan et al. (2013) [30] | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7 | Low |

| Scheffler et al. (2014) [31] | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 9 | Low |

| Foot et al. (2014) [32] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 9 | Low |

| De Oliveira et al. (2014) [33] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 | Low |

| Hart et al. (2015) [34] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 | Low |

| Marzouk et al. (2015) [35] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 11 | Average |

| Marzouk and Kassem (2016) [36] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 14 | Average |

| Turkkahra man and Sarioglu (2016) [12] | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 15 | Average |

| Akl et al. (2020) [37] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 18 | High |

| Akbaydogan and Akin (2021) [38] | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 13 | Average |

| Akl et al. (2025) [39] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 24 | Very high |

| OVERBITE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Author (Year) | Patient Sample | Mean Difference (After-Before) (mm) | SD of Differences |

| Lee HA, and Park YC (2008) [25] | 11 | 5.47 | 1.28 |

| Baek et al. (2010) [27] | 9 | 5.56 | 1.235 |

| Deguchi et al. (2011) [29] | 15 | 6.2 | 1.15 |

| Marzouk and Kassem (2016) [36] | 26 | 6.93 | 1.375 |

| Akl et al. (2025) [39] | 20 | 3.42 | 1.79 |

| ANB | |||

| Author (Year) | Patient Sample | Mean Difference (After-Before) (°) | SD of Differences |

| Lee HA, and Park YC (2008) [25] | 11 | −0.59 | 1.39 |

| Baek et al. (2010) [27] | 9 | −0.66 | 1.42 |

| Deguchi et al. (2011) [29] | 15 | −1.5 | 3.85 |

| Marzouk and Kassem (2016) [36] | 26 | −3.84 | 1.12 |

| Akl et al. (2025) [39] | 20 | 0.05 | 1.74 |

| N-Me | |||

| Author (Year) | Patient Sample | Mean Difference (After-Before) (mm) | SD of Differences |

| Lee HA, and Park YC (2008) [25] | 11 | −2.64 | 5.61 |

| Baek et al. (2010) [27] | 9 | −2.54 | 5.825 |

| Deguchi et al. (2011) [29] | 15 | −3.6 | 6.7 |

| Marzouk and Kassem (2016) [36] | 26 | −3.63 | 5.915 |

| Akl et al. (2025) [39] | 20 | −1.99 | 4.47 |

| FMA | |||

| Author (Year) | Patient Sample | Mean Difference (After-Before) (°) | SD of Differences |

| Lee HA, and Park YC (2008) [25] | 11 | −2.9 | 3.41 |

| Baek et al. (2010) [27] | 9 | −3.15 | 3.665 |

| Akl et al. (2025) [39] | 20 | −1.38 | 4.34 |

| SN-GoMe | |||

| Author (Year) | Patient Sample | Mean Difference (After-Before) (°) | SD of Differences |

| Lee HA, and Park YC (2008) [25] | 11 | −1.99 | 4.25 |

| Baek et al. (2010) [27] | 9 | −2.03 | 4.26 |

| Akl et al. (2025) [39] | 20 | −1.03 | 4.43 |

| SN-Pog | |||

| Author (Year) | Patient Sample | Mean Difference (After-Before) (°) | SD of Differences |

| Lee HA, and Park YC (2008) [25] | 11 | −0.23 | 4.39 |

| Baek et al. (2010) [27] | 9 | −0.47 | 3.945 |

| Marzouk and Kassem (2016) [36] | 26 | −0.49 | 2.605 |

| Akl et al. (2025) [39] | 20 | −0.07 | 4.07 |

| OVERBITE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Author (Year) | Patient Sample | Mean Difference (After-Before) (mm) | SD of Differences |

| Lee HA, and Park YC (2008) [25] | 11 | −0.98 | 0.745 |

| Baek et al. (2010) [27] | 9 | −0.99 | 0.805 |

| Deguchi et al. (2011) [29] | 15 | −0.8 | 0.1 |

| Marzouk and Kassem (2016) [36] | 26 | −0.57 | 0.45 |

| Akl et al. (2025) [39] | 20 | −0.35 | 1.79 |

| ANB | |||

| Author (Year) | Patient Sample | Mean Difference (After-Before) (°) | SD of Differences |

| Lee HA, and Park YC (2008) [25] | 11 | 0 | 1.425 |

| Baek et al. (2010) [27] | 9 | 0 | 1.555 |

| Deguchi et al. (2011) [29] | 15 | 0.1 | 0.05 |

| Marzouk and Kassem (2016) [36] | 26 | 0.33 | 1.125 |

| Akl et al. (2025) [39] | 20 | 0.05 | 1.74 |

| N-Me | |||

| Author (Year) | Patient Sample | Mean Difference (After-Before) (mm) | SD of Differences |

| Lee HA, and Park YC (2008) [25] | 11 | 0.38 | 5.59 |

| Baek et al. (2010) [27] | 9 | 0.45 | 5.82 |

| Deguchi et al. (2011) [29] | 15 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Marzouk and Kassem (2016) [36] | 26 | 0.56 | 5.725 |

| Akl et al. (2025) [39] | 20 | 0.19 | 4.56 |

| FMA | |||

| Author (Year) | Patient Sample | Mean Difference (After-Before) (°) | SD of Differences |

| Lee HA, and Park YC (2008) [25] | 11 | 0.91 | 3.755 |

| Baek et al. (2010) [27] | 9 | 0.63 | 3.995 |

| Akl et al. (2025) [39] | 20 | 0.10 | 4.83 |

| SN-GoMe | |||

| Author (Year) | Patient Sample | Mean Difference (After-Before) (°) | SD of Differences |

| Lee HA, and Park YC (2008) [25] | 11 | 0.18 | 4.7 |

| Baek et al. (2010) [27] | 9 | 0.27 | 4.645 |

| Akl et al. (2025) [39] | 20 | 0.11 | 4.43 |

| SN-Pog | |||

| Author (Year) | Patient Sample | Mean Difference (After-Before) (°) | SD of Differences |

| Lee HA, and Park YC (2008) [25] | 11 | 0.9 | 4.05 |

| Baek et al. (2010) [27] | 9 | 1.1 | 3.68 |

| Marzouk and Kassem (2016) [36] | 26 | 2.32 | 2.665 |

| Akl et al. (2025) [39] | 20 | 0.94 | 4.07 |

| OVERBITE | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Author (Year) | Patient Sample | Mean Difference (After-Before) (mm) | SD of Differences |

| Baek et al. (2010)) [27] | 9 | −1.2 | 0.955 |

| Marzouk and Kassem (2016) [36] | 26 | −0.77 | 0.435 |

| Akl et al. (2025) [39] | 20 | −0.37 | 1.79 |

| ANB | |||

| Author (Year) | Patient Sample | Mean Difference (After-Before) (°) | SD of Differences |

| Baek et al. (2010) [27] | 9 | 0.17 | 1.615 |

| Marzouk and Kassem (2016) [36] | 26 | 0.61 | 1.13 |

| Akl et al. (2025) [39] | 20 | 0.04 | 1.74 |

| N-Me | |||

| Author (Year) | Patient Sample | Mean Difference (After-Before) (mm) | SD of Differences |

| Baek et al. (2010) [27] | 9 | 0.91 | 5.985 |

| Marzouk and Kassem (2016) [36] | 26 | 1.06 | 5.725 |

| Akl et al. (2025) [39] | 20 | 0.23 | 4.56 |

| SN-Pog | |||

| Author (Year) | Patient Sample | Mean Difference (After-Before) (°) | SD of Differences |

| Baek et al. (2010) [27] | 9 | −0.87 | 3.915 |

| Marzouk and Kassem (2016) [36] | 26 | −0.83 | 2.63 |

| Akl et al. (2025) [39] | 20 | −0.08 | 4.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ugolini, A.; Donelli, M.; Bruni, A.; Cirulli, N.; Berlen, M.; Abate, A.; Lanteri, V. Cephalometric Assessment and Long-Term Stability of Anterior Open-Bite Correction with Skeletal Anchorage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11415. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111415

Ugolini A, Donelli M, Bruni A, Cirulli N, Berlen M, Abate A, Lanteri V. Cephalometric Assessment and Long-Term Stability of Anterior Open-Bite Correction with Skeletal Anchorage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11415. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111415

Chicago/Turabian StyleUgolini, Alessandro, Margherita Donelli, Alessandro Bruni, Nunzio Cirulli, Massimo Berlen, Andrea Abate, and Valentina Lanteri. 2025. "Cephalometric Assessment and Long-Term Stability of Anterior Open-Bite Correction with Skeletal Anchorage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11415. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111415

APA StyleUgolini, A., Donelli, M., Bruni, A., Cirulli, N., Berlen, M., Abate, A., & Lanteri, V. (2025). Cephalometric Assessment and Long-Term Stability of Anterior Open-Bite Correction with Skeletal Anchorage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11415. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111415