Abstract

This study develops a discrete element model incorporating the water–ice phase transition volume effect to simulate frost damage in saturated granite. The model investigates the damage evolution and mechanical degradation under freeze–thaw cycles. The results show that during freeze–thaw cycles, the model’s temperature field exhibits non-uniform distribution characteristics and geometric dependency, with lower maximum temperature differences in Brazilian disk models versus uniaxial compression specimens. Frost heave damage progresses through three distinct stages: localized bond fractures (1~5 cycles); accelerated crack interconnection and branching (15~20 cycles); and fully interconnected damage zones (25~30 cycles). As the number of freeze–thaw cycles increases, the crack network significantly influences the mechanical behavior of the model under load. The failure mode of the loaded model undergoes a transformation from brittle penetration to ductile fragmentation. Freeze–thaw cycles cause more significant degradation in the tensile strength of granite compared to compressive strength. After 30 freeze–thaw cycles, the uniaxial compressive strength and Brazilian tensile strength decrease by 47.5% and 93.8%, respectively. These findings provide theoretical support for assessing frost heave damage in geotechnical engineering in cold regions.

1. Introduction

The stability of cold-region engineering projects such as slopes, foundations, and tunnels is severely threatened by the deterioration of rock mechanical properties under freeze–thaw (F-T) cycles [1,2,3]. There is evidence indicating that the stability of rock masses in cold regions after open-pit mining significantly decreases due to the F-T cycle [4,5]. Intact rocks undergo significant degradation in their physical and mechanical properties after F-T cycles. Extensive laboratory tests demonstrate that the uniaxial compressive strength (UCS), Brazilian tensile strength (BTS), and elastic modulus of granite exhibit a nonlinear decreasing trend with increasing F-T cycles, with strength losses exceeding 50% [6,7]. This deterioration originates from the frost heave pressure generated by water–ice phase transition within rocks, with theoretical values reaching 200 MPa, which triggers the initiation and propagation of microcracks [8]. Especially when the rock is in a fully saturated state, the freezing and expansion of the pore water within the rock lead to a significant deterioration in the physical and mechanical properties of the rock [9]. Gao et al. [10] systematically confirmed through experiments that the degradation rates of UCS and BTS in granite follow an exponential relationship with F-T cycles, and tensile strength exhibits higher sensitivity to damage. J. Kodama et al. [11] investigated the effects of water content, temperature, and loading rate on the mechanical strength and failure modes of rocks in alpine regions. Li et al. [12] analyzed changes in mechanical parameters of granite specimens after F-T cycles and uniaxial compression tests, elucidated the F-T degradation mechanisms, and applied their findings to slope stability analysis in open-pit mines. Walbert et al. [13] investigated the frost weathering and thermal behavior of three types of rocks during the freeze–thaw cycle, as well as their different physical and mechanical properties. Meanwhile, Bayram [7] conducted freeze–thaw cycle tests on rock samples and established a statistical model for predicting the percentage loss of uniaxial compressive strength. Jin et al. [14] conducted triaxial compression tests on sandstone after F-T cycles, revealing the combined effects of F-T cycles and confining pressure on mechanical properties and permeability.

To uncover the microscopic mechanisms of F-T damage, the Discrete Element Method (DEM) has emerged as a vital tool due to its ability to visually characterize particle fracture processes. In current research on damage in DEM, the Parallel Bond Model (PBM) fracture is commonly used to quantify the degree of damage when the local stress exceeds the model’s strength threshold [15]. Existing models of F-T cycles primarily simulate frost heave effects using “equivalent expansion forces” or “phase-change particles” [16,17]. However, damage evolution and crack propagation paths under varying F-T cycles remain insufficiently characterized [18], and the physical realism of ice–water phase-change volume effects requires enhancement [19]. Acoustic emission (AE) technology serves as an effective means for monitoring frost heave damage evolution in rocks. AE events, elastic wave signals released during microcrack propagation, reflect internal damage states [20]. F-T cycles significantly alter AE characteristics: cumulative event counts increase, b-values decrease, and energy release occurs earlier [21]. Wang et al. [22] demonstrated a strong correlation between AE energy and strength loss rates in post-F-T rocks. Nevertheless, current research lacks AE quantitative models based on microscopic fracture mechanisms, hindering the establishment of physical links between AE parameters and crack generation mechanisms [23,24].

In summary, this study employs the DEM to establish a frost damage model for saturated granite that accounts for the volume effect of water–ice phase transition. The objectives are to reveal the influence of F-T cycles on the degradation laws of UCS and BTS in granite. And by referring to the visualization effect of the AE technology, the spatiotemporal evolution law of crack propagation caused by frost heave damage is analyzed based on the interparticle bond fractures.

2. Numerical Model Construction and Parameter Calibration

2.1. Simulation Mechanism of Frost Heave Damage

The DEM solves the dynamic behavior of particle systems based on Newton’s laws of motion. By simulating contact forces and displacements between particles, it reproduces the continuous process from microscopic damage to macroscopic failure in rocks [25]. Some scholars [26,27,28] have already conducted research using the DEM, where water (ice) particles are used to represent the pore water, to study the phenomenon of damage occurring in the pore medium due to the expansion and contraction of pore water. Shen et al. [27] quantified the error between the rock strength damage situation obtained from indoor experiments after different freeze–thaw cycles and the numerical simulation results. They verified the rationality of the discrete element simulation of pore medium expansion and contraction damage under the condition of high bonding strength between water particles and matrix particles.

Therefore, based on the aforementioned related studies, this article uses the PFC5.0 discrete element software to establish a numerical model for the freeze–thaw damage of granite. The core building units of the model are rock particles and water (ice) particles. In this investigation, the thermal module in PFC5.0 is used to simulate the temperature field, and the water particles that enter the phase change temperature range are given a thermal expansion coefficient. After the water particles exit the phase change temperature range, they undergo a 9% volume expansion and then transform into ice particles. Due to the increase in the size of the ice particles, it inevitably leads to an increase in the original contact force between the surrounding rock particles. Thus, the thermal and mechanical coupling of the DEM is achieved. To ensure the simulation effect of freeze–thaw damage, all particles are connected through the Parallel Bond Model (PBM) [26]. The PBM between rock particles is to simulate the cohesion characteristics of the rock, and the PBM between water particles is to ensure the effective transmission of the above freeze–thaw force. Since the subsequent single-axis compression, Brazilian splitting, and other simulations are all carried out in the model after deleting the water particles, the high adhesion strength between the water particles and the rock particles will not have an impact on this result. The PBM defines the stiffness, strength, and effective range of bonds between particles. Its fracture behavior directly characterizes the initiation of microcracks, serving as the physical carrier for frost damage evolution.

2.2. Construction of the Uniaxial Compression Model

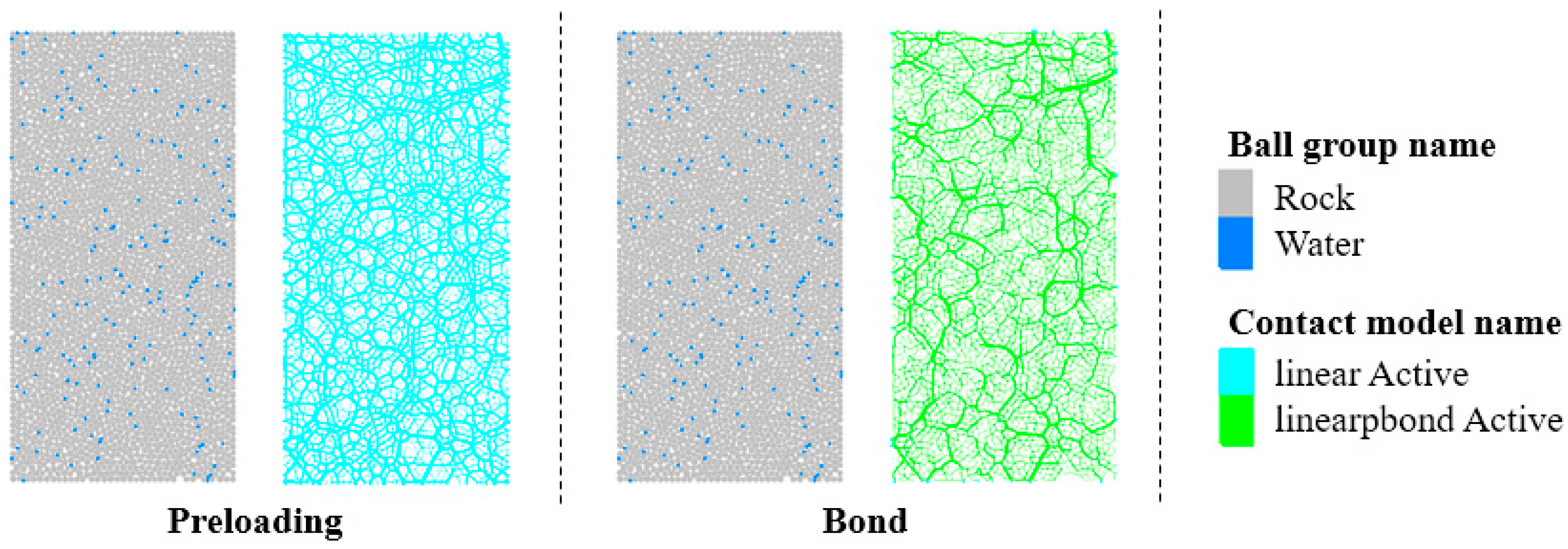

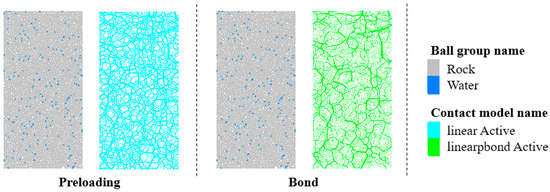

The uniaxial compression model was designed according to the standard dimensions recommended by the International Society for Rock Mechanics (ISRM): cylinder radius 25 mm, height 100 mm. The model was generated using rock particles (radius 0.58~0.78 mm) and water particles (radius 0.38 mm). The volumetric fraction of water particles was controlled at 2%, with the remaining 98% comprising rock particles and interparticle pores. The initial porosity was set to 15%. After model generation, preloading and application of PBM bonds at particle contacts were sequentially performed, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Construction workflow of the uniaxial compression model.

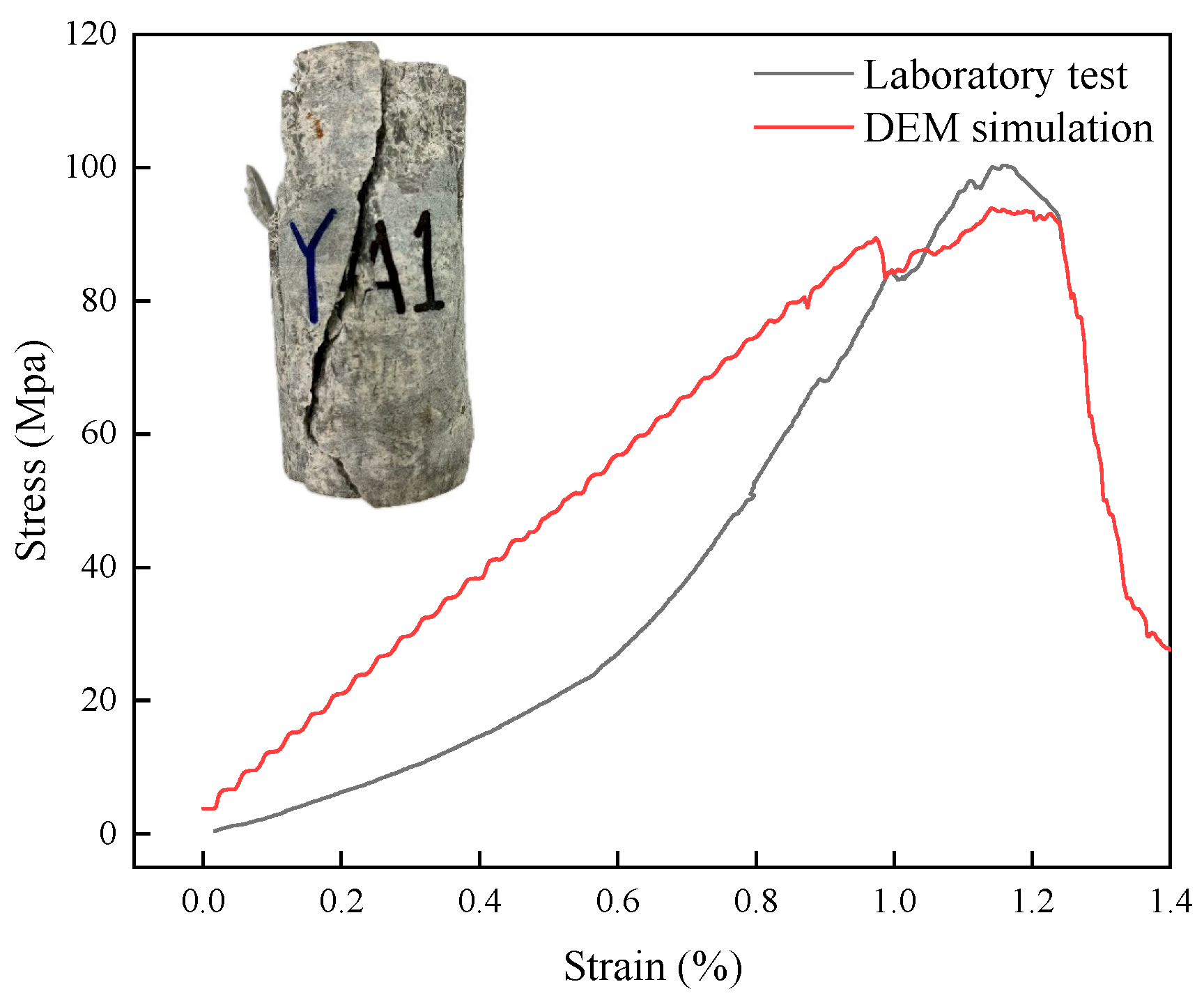

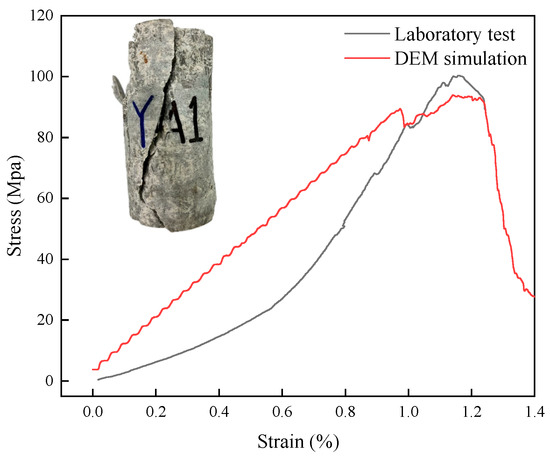

Based on relevant literature on sensitivity analysis of discrete element parameters [29,30], the parameters were calibrated by repeatedly modifying them through the “trial-and-error method”, so that the curve results of the numerical simulation continuously approached the experimental curves. The results of the uniaxial compression test of granite used for parameter calibration are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Stress–strain curve of granite under uniaxial compression.

Calibration targets included particle and bond model parameters. Key parameters of the PBM include bond elastic modulus, tensile strength, and cohesion. Parameters were adjusted iteratively until the simulated peak strength, failure pattern, and post-peak softening behavior closely matched the experimental curves. The final calibrated parameters for uniaxial compression are listed in Table 1. After parameter calibration, the water particles were removed, and a uniaxial compression simulation under drying conditions was conducted. The comparison results between the simulated curve and the test curve are shown in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Calibrated parameters for the uniaxial compression model.

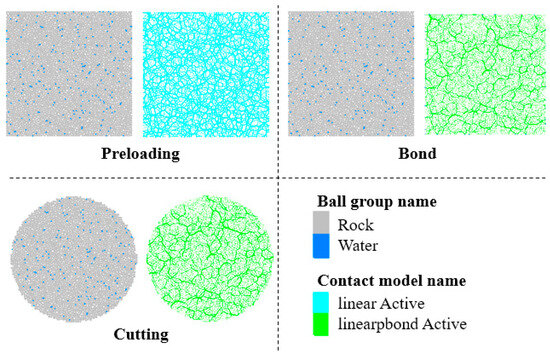

2.3. Construction of the Brazilian Splitting Model

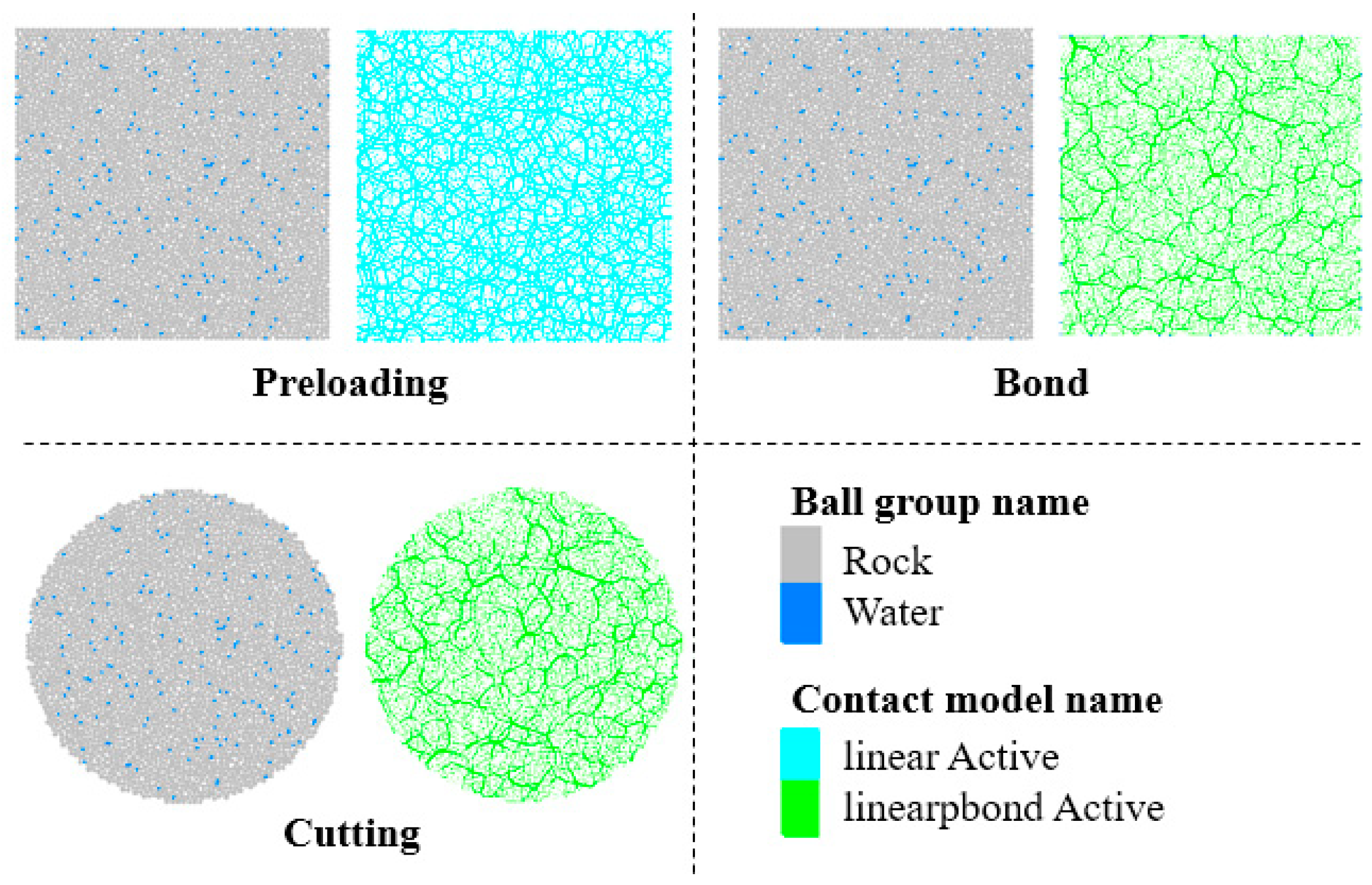

The Brazilian splitting specimen was an ISRM-standard disk. A 2D DEM model with a radius of 25 mm was established in PFC5.0. The generation logic for rock and water particles followed the uniaxial model, but particle radii were refined for accuracy due to a smaller model volume: rock particles were 0.36~0.48 mm, and water particles were 0.24 mm. After preloading and PBM bond application, the generated specimen was cut. The construction process of the Brazilian splitting model is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Construction workflow of the Brazilian disk model.

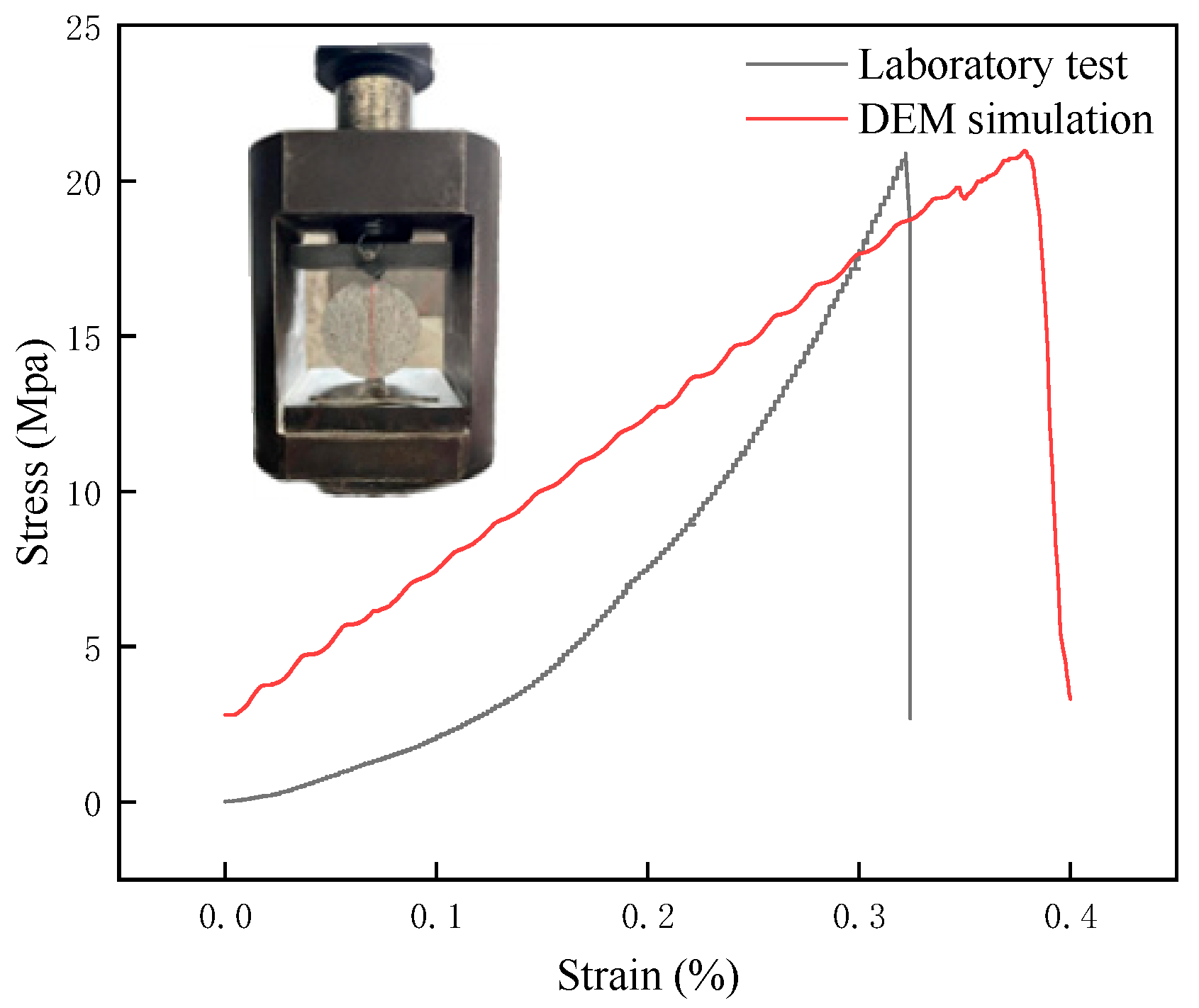

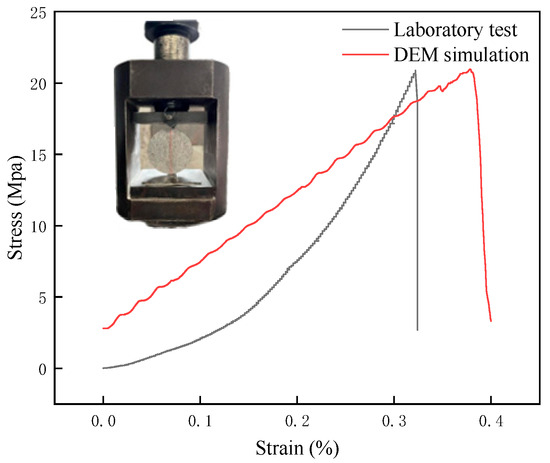

The calibration method for the uniaxial compression model is the same. It is based on the relevant literature, such as the sensitivity analysis of discrete element parameters [29,30]. The parameters are calibrated by repeatedly modifying them through the “trial-and-error method”, so that the curve results of the numerical simulation continuously approach the experimental curves. Parameters were calibrated against laboratory Brazilian splitting test results. The final calibrated parameters are listed in Table 2. After parameter calibration, the water particles were removed, and a uniaxial compression simulation under drying conditions was conducted. The comparison results between the simulated curve and the test curve are shown in Figure 4.

Table 2.

Calibrated parameters for the Brazilian splitting model.

Figure 4.

Stress–strain curve of granite under Brazilian splitting.

3. Discrete Element Simulation of the Temperature Field in F-T Cycles

3.1. Determination of Thermal Parameters

During F-T cycles, water particles undergo phase transition to ice below 0 °C with a 9% volume expansion. The resulting frost heave force is transmitted to the PBM at particle contacts. When local stress exceeds the bond strength threshold, bond fracture occurs, physically simulating frost heave damage. Establishing an accurate temperature field is essential for reliable frost damage simulation. Thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity were determined through laboratory tests, and these parameters were incorporated into the numerical model developed in Section 2.

Thermal conductivity is a critical thermal property of rocks. According to the second law of thermodynamics, heat flows continuously from high-temperature to low-temperature regions within a material until thermal equilibrium is achieved. For a plane of area A with unidirectional temperature variation, the heat flux Q through A is proportional to the temperature gradient dT/dx and time dt:

where k denotes thermal conductivity, defined as the heat energy transferred per unit area per unit time when dT and dx equal 1.

Three 10 mm thick specimens were extracted from a 50 mm diameter granite porphyry core. Thermal conductivity was measured using a DRL-III thermal conductivity tester (Figure 5). Specimen dimensions were recorded before testing to calculate the effective area A. Results are summarized in Table 3. The average thermal conductivity from three tests was 3.602 W/(m·K).

Figure 5.

DRL-III thermal conductivity tester.

Table 3.

Thermal conductivity test of granite porphyry.

Specific heat capacity was measured using a Hot Disk thermal constant analyzer (Figure 6). This instrument employs a nickel-based planar sensor acting as both a heat source and a temperature detector. The working principle assumes the sample is infinite relative to the sensor, or heat flows radially within the sample during testing.

Figure 6.

Hot Disk Thermal constant analyzer.

Two flat sample pieces sandwiched the sensor. By regulating power and duration, transient temperature rise, and the characteristic time ratio and residuals were recorded. Thermal parameters were derived via mathematical fitting. Results in Table 4 show elevated thermal conductivity in oversaturated samples due to metallic minerals in the cross-section.

Table 4.

Summary of the results of granite porphyry transient measurement of thermal parameters.

3.2. Simulation and Analysis of Temperature Field

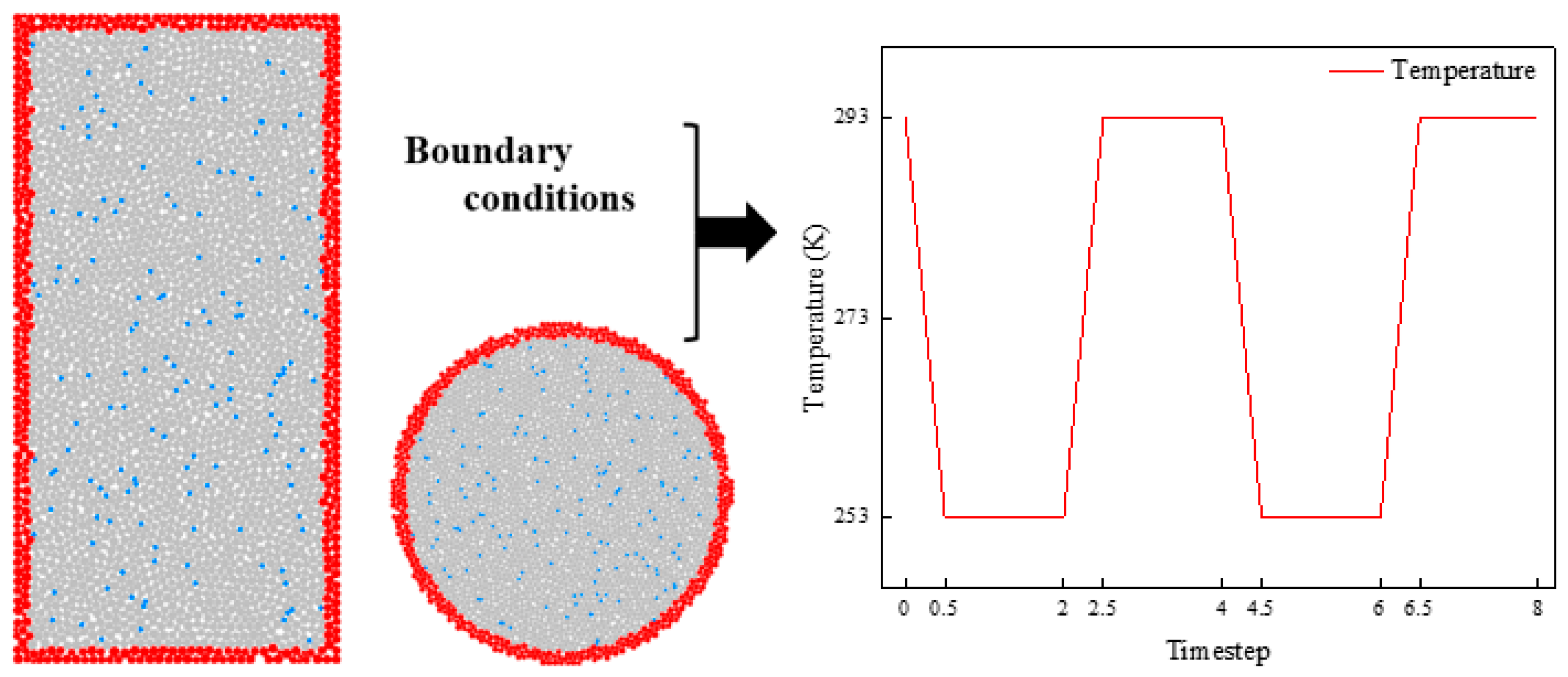

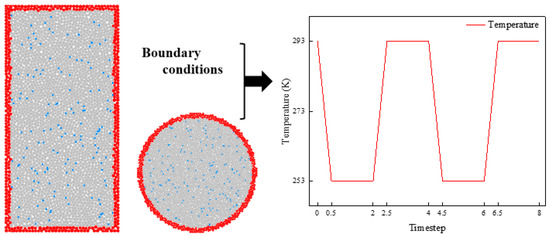

F-T cycle simulation was implemented by controlling temperature field variations to achieve phase-change expansion and contraction of water particles. Temperature gradients were applied to boundary particles via the thermal conduction module in PFC5.0 and progressively transmitted inward. Boundary conditions and temperature settings are shown in Figure 7. The red particles are those with the boundary conditions added. Heat transfer strictly adhered to Fourier’s law, with parameters including thermal conductivity, thermal resistance, and specific heat capacity calibrated based on laboratory test results. Both uniaxial compression and Brazilian splitting models employed identical thermal cycling settings: each cycle comprised 4 timesteps, with a cooling phase of 0.5 timesteps (linear decrease from 293 K to 253 K), a freezing phase of 1.5 timesteps (maintained at 253 K until full particle stabilization), a heating phase of 0.5 timesteps (linear increase from 253 K to 293 K), and a thawing phase of 1.5 timesteps (maintained at 293 K until equilibrium). Temperature distributions at key timesteps clearly demonstrate the spatiotemporal evolution and geometric dependence of the temperature field.

Figure 7.

Boundary condition settings.

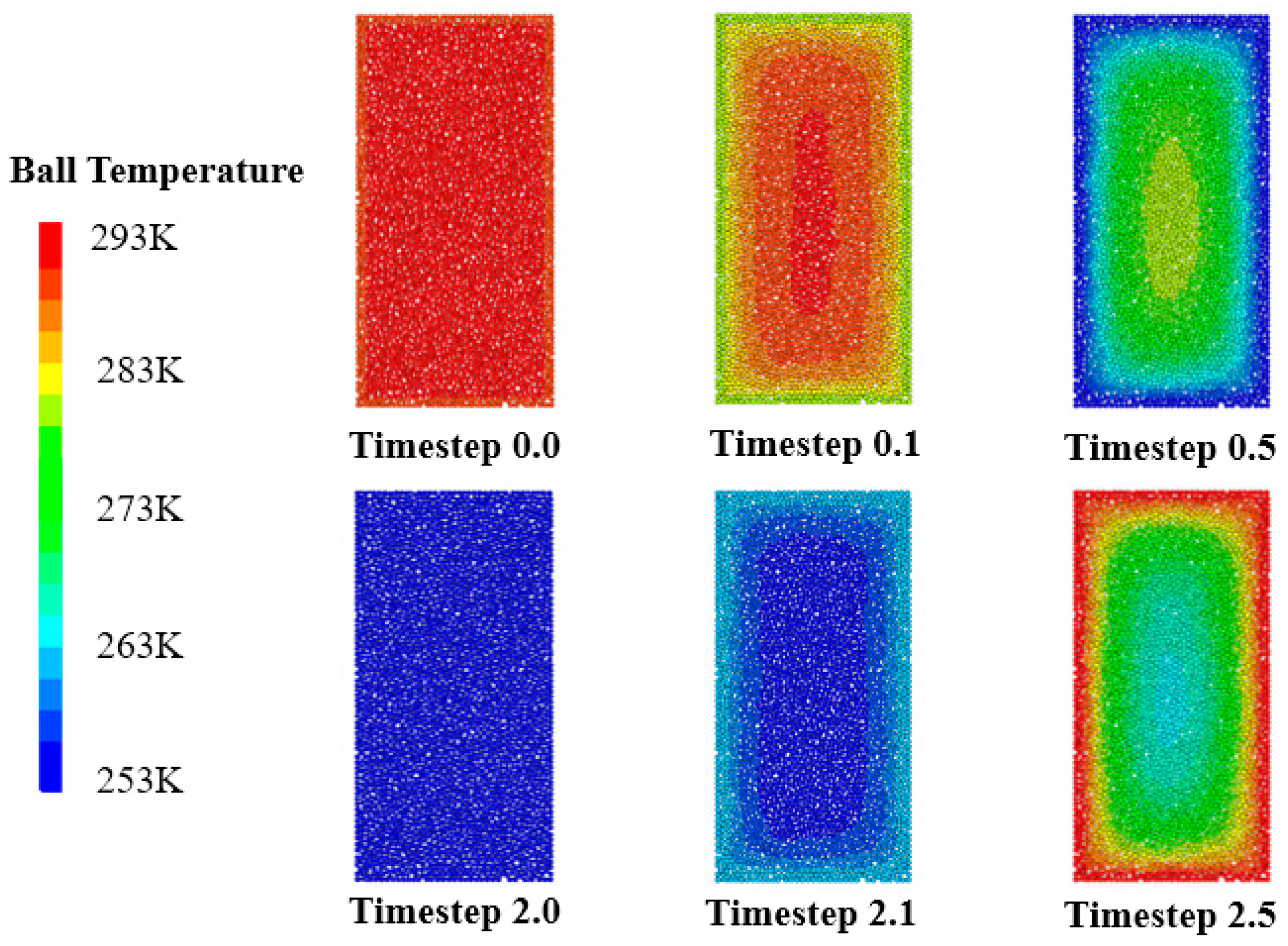

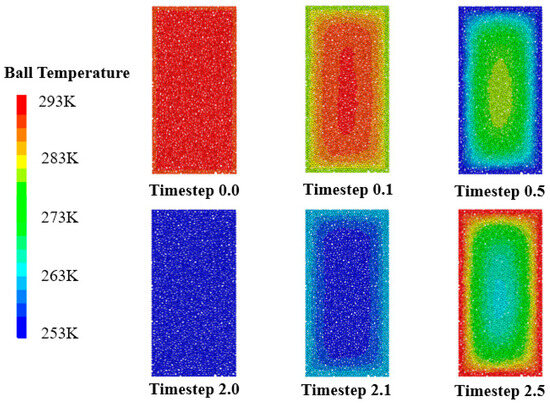

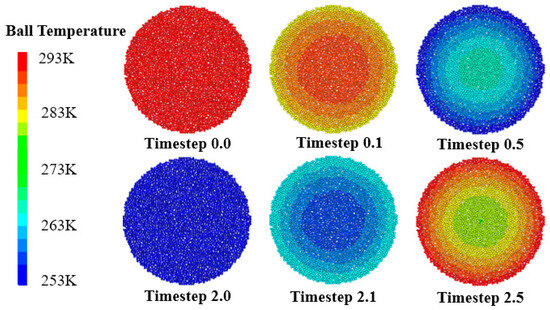

As shown in Figure 8, the uniaxial model exhibited significant axial temperature gradients. In the initial state (Timestep 0.0), the specimen displayed a uniform temperature distribution (293 K, red), indicating stable thermal equilibrium. During early cooling (Timestep 0.1), boundary particles cooled first under the cold source, forming an axial gradient from cooler edges of 288 K to the warmer center of 293 K. Heat flow perpendicular to the specimen’s long axis maintained higher central temperatures due to thermal inertia. At cooling completion (Timestep 0.5), boundary temperatures dropped to 253 K, while the center retained a narrow high-temperature zone (ΔT = 30 K), highlighting axial hysteresis in the rectangular specimen. By freezing completion (Timestep 2.0), the specimen uniformly reached 253 K after thermal equilibrium, with all water particles completing phase change and volumetric expansion. During early heating (Timestep 2.1), boundaries warmed preferentially, while the center remained at 253 K, establishing a reversed gradient. At heating completion (Timestep 2.5), boundaries returned to 293 K, but a residual central cold zone persisted, confirming slower thermal conduction rates in the core region.

Figure 8.

Temperature field distribution in the uniaxial compression model.

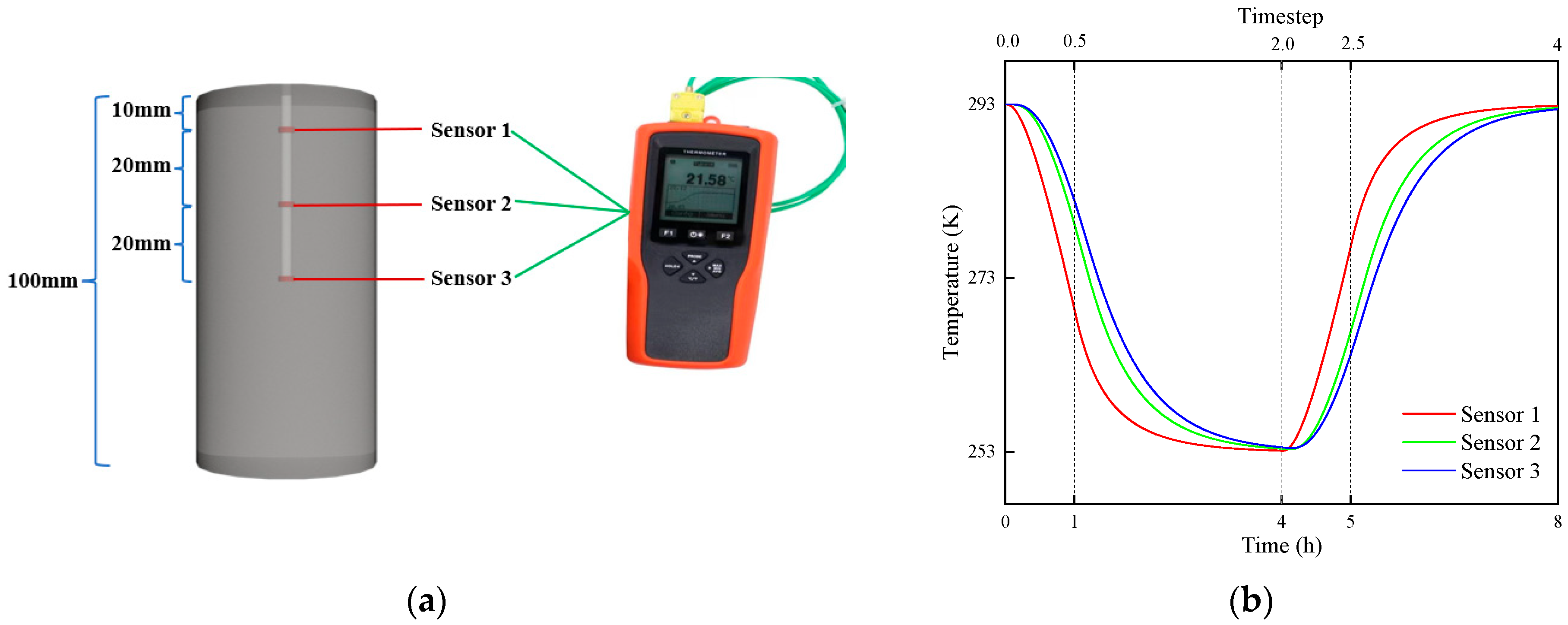

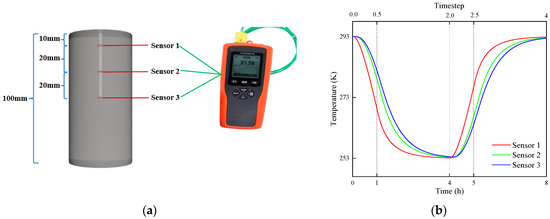

To verify the accuracy of the above-mentioned discrete element simulation of the temperature field, laboratory tests were conducted for comparison. As shown in Figure 9a, a cylindrical sample with a hole from the upper surface to the center was processed, and three T-type thermocouple sensors were arranged at 10 mm, 30 mm, and 50 mm intervals from the upper surface downward. To prevent excessive water from entering the holes and causing measurement errors, granite debris of the same nature as the sample was completely filled in the holes. Finally, the sample was saturated with water, sealed, and placed in the freeze–thaw test chamber. The freeze–thaw parameters were consistent with the boundary conditions of the numerical simulation, and the actual test time of 1 h corresponded to a 0.5 timestep of the numerical simulation. Based on the temperature change curves of different positions during the F-T process obtained from the thermocouple temperature measurement test in Figure 9b, it can be found that it has a high degree of correspondence with the temperature field simulation results of the uniaxial compression model (Figure 8). The laboratory test results and the temperature field curves of the discrete element simulation show a high degree of consistency in trend, numerical values, and depth dependence, fully verifying the accuracy of this simulation method in predicting the F-T cycle temperature field. Especially for the prediction of temperature distribution at different depths and lag effects, it provides reliable temperature field input for subsequent research on rock frost heave damage under F-T cycles, and indicates that this simulation method can be used for further analysis of F-T damage.

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram and results of temperature measurement in laboratory tests: (a) schematic diagram of temperature measurement; (b) laboratory test results.

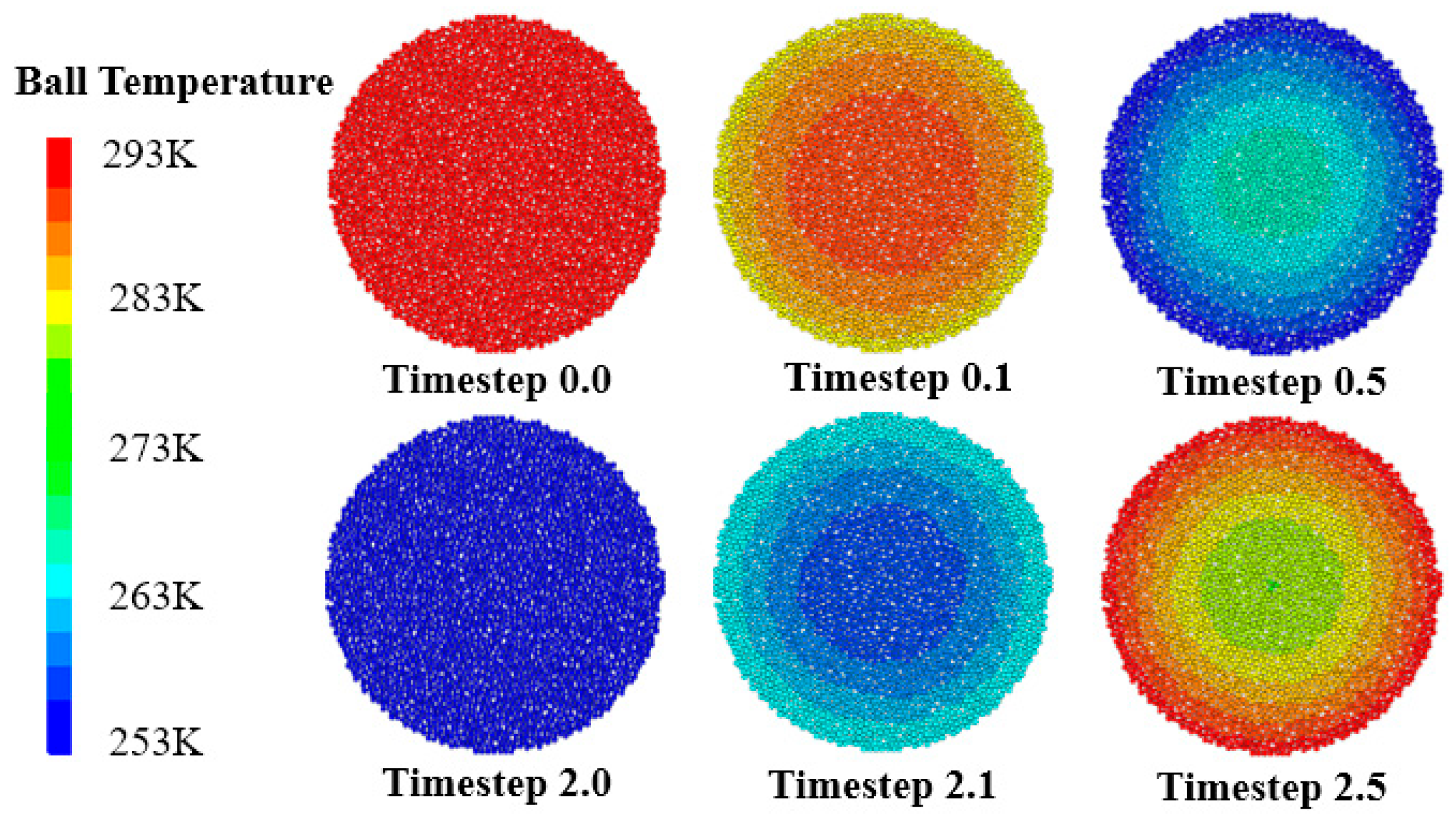

As shown in Figure 10, the Brazilian disk model demonstrated radially symmetric diffusion. Initially uniform at 293 K, early cooling (Timestep 0.1) formed an annular cooling band at the periphery while the center remained above 290 K, with radial inward heat flow. By Timestep 0.5, the outer ring expanded into a 253 K low-temperature zone, contracting the center to a warmer core (max ΔT lower than in the uniaxial model), indicating weaker radial hysteresis. Freezing completion (Timestep 2.0) achieved a uniform 253 K with completed phase change. During heating (Timestep 2.1~2.5), a warming ring advanced from the boundary, leaving a residual cold core at the center due to geometric heat accumulation effects.

Figure 10.

Temperature field distribution in the Brazilian disk model.

4. Frost Heave Damage Patterns in Granite After Different F-T Cycles

4.1. Frost Heave Damage Patterns in the Initial Stage of F-T Cycles

This article visualizes the tracking of contact fractures and crack data monitoring in the rock mass model by writing the Fish function [31,32]. Firstly, the particle pointers and positions of the two ends where the fracture contact occurs are obtained. Then, the corresponding contact state and normal force are searched based on the pointers. If the contact state (mode) = 1, the fracture is determined as tensile failure; if the contact state (mode) = 2, the fracture is determined as shear failure. In the shear failure state, the fracture stress is further viewed. If the fracture stress is less than the cohesion, it is determined as shear–tensile failure; otherwise, it is determined as shear–compressive failure.

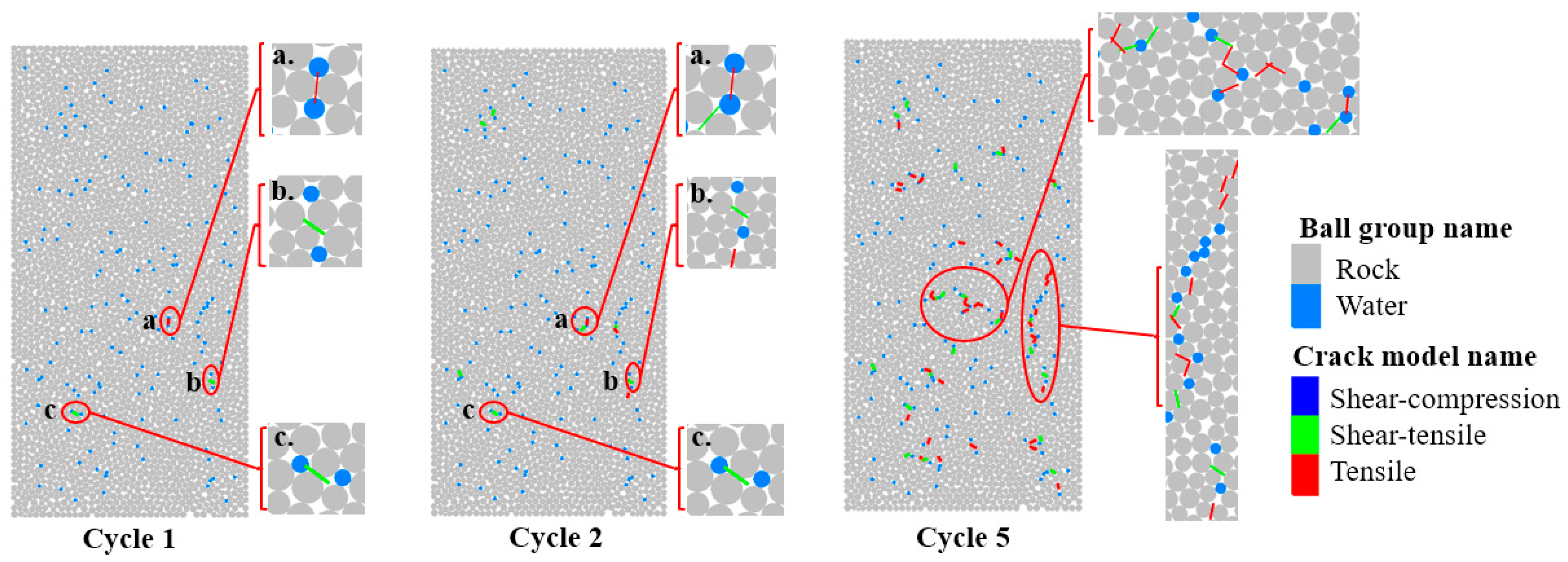

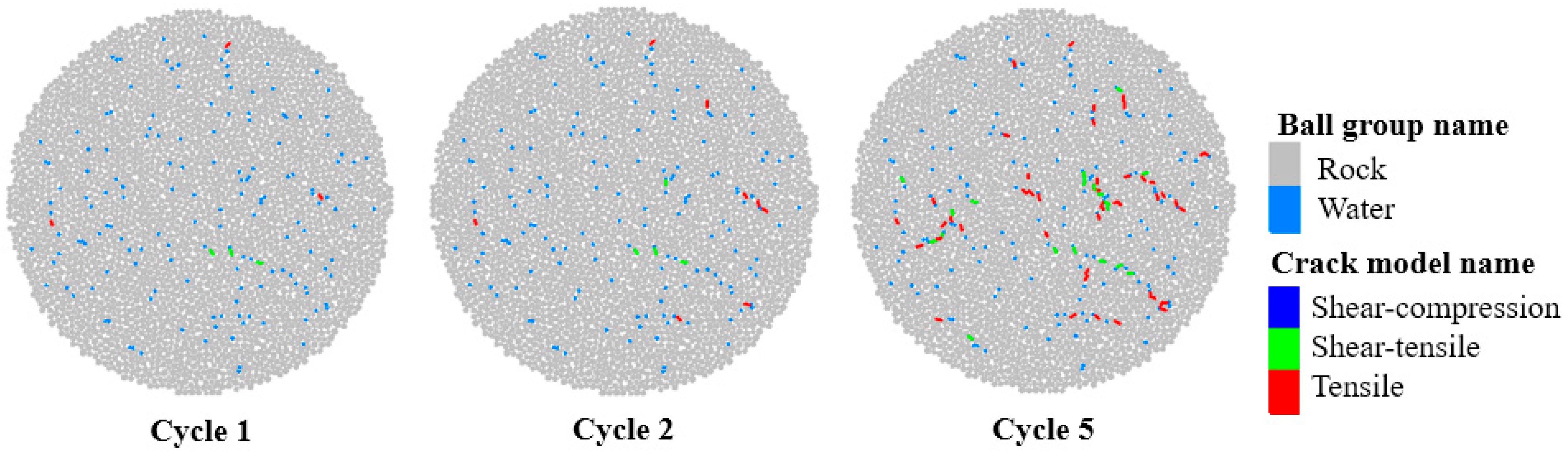

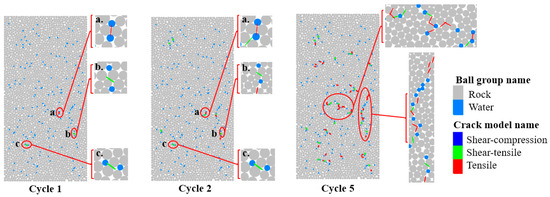

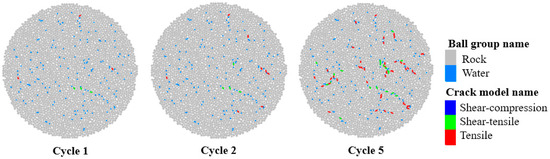

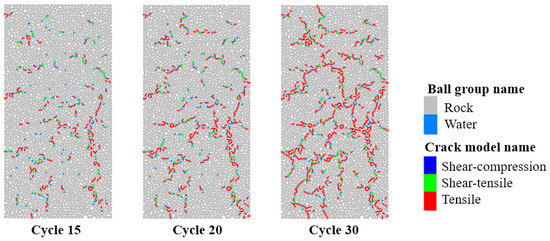

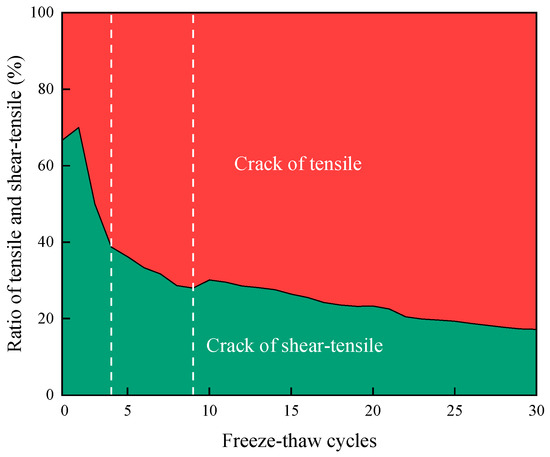

The essence of frost heave damage in the DEM is the cumulative process of bond fractures between rock particles driven by the expansion force generated during the phase transition of water particles. The evolution of this damage can be quantitatively characterized by the spatial distribution characteristics of cracks and the proportion of fractured bonds. Figure 11 and Figure 12 illustrate the crack distributions in the granite DEM model after 1, 2, and 5 F-T cycles, where red represents tensile cracks, green represents shear–tensile composite cracks, and blue represents shear–compression cracks, depicting the evolution process of damage microcracks from initiation to propagation.

Figure 11.

Crack distribution in the uniaxial compression model during the initial F-T cycles.

Figure 12.

Crack distribution in the Brazilian disk model during the initial F-T cycles.

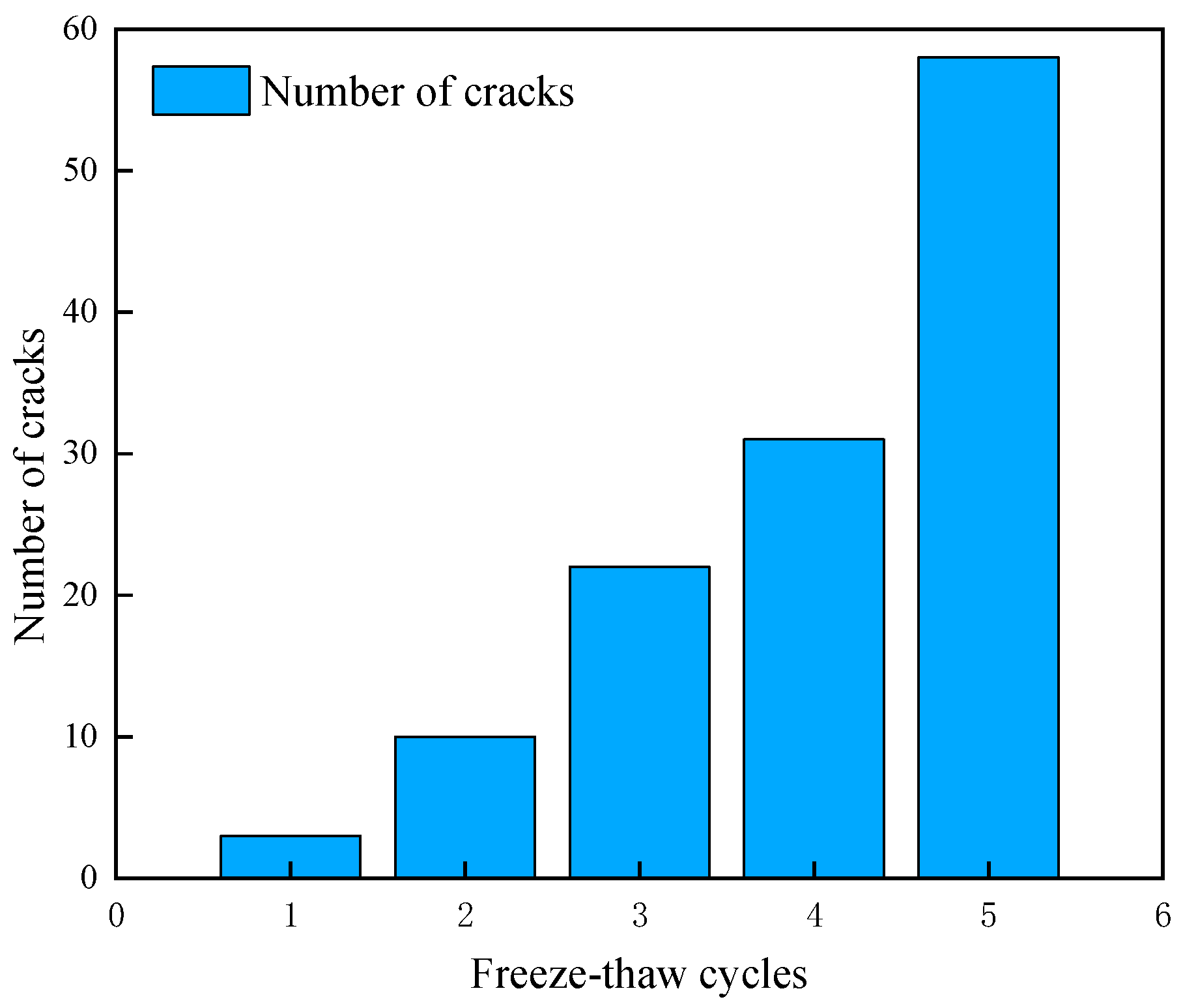

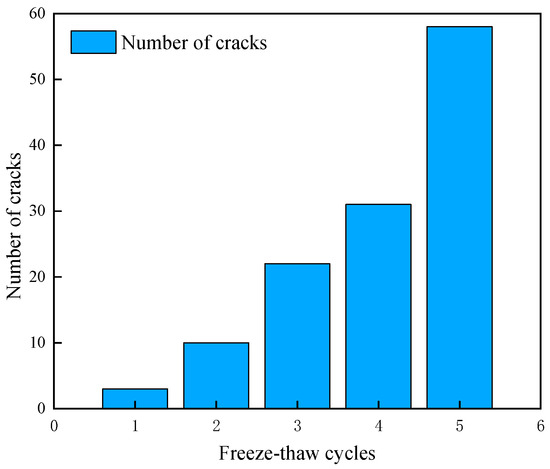

The crack distribution and the trend of crack quantity change were essentially consistent between the uniaxial compression model and the Brazilian disk model. The crack counts from both models were averaged and summarized in Figure 13. During the first F-T cycle, frost heave damage primarily initiated in the vicinity of the interfaces between water particles and rock particles. When water particles underwent phase transition and expansion, they exerted radial tensile forces on the surrounding rock particles. When the local tensile stress exceeded the normal strength of the bonds, the PBM fractured, forming tensile cracks or shear–tensile composite cracks. At this stage, cracks existed only as discrete point sources, randomly distributed around some water particles, without forming continuous paths. The proportion of fractured bonds was merely 0.10%, indicating damage was in a negligible initial state. The damage mechanism was dominated by local tensile failure induced by water particle expansion, with no significant cumulative effect.

Figure 13.

Variation in crack number within the DEM model during the initial F-T cycles.

After the second cycle, cracks not only initiated around individual water particles but also connected to form shorter continuous fracture paths through further bond fractures between rock particles. The accumulated frost heave forces promoted the propagation of discrete cracks along the existing weak fracture paths formed earlier. The discrete cracks from the first cycle became stress concentration zones in subsequent cycles, allowing frost heave forces to propagate along these paths. The proportion of fractured bonds increased to 0.33%. After 5 F-T cycles, the cracks had evolved from point-line patterns into localized damage networks. Cracks surrounding water particles are interconnected, forming multiple penetrating damage bands, still dominated by tensile cracks with no shear–compression cracks present. The proportion of fractured bonds reached 1.93%. Although the damage remained relatively minor, it laid the foundation for accelerated damage in subsequent cycles, marking the entry into the incipient damage stage.

The crack distribution observed in the initial F-T cycles reflects the spatial heterogeneity and temporal accumulation of frost heave damage. It can be concluded that the core driving factor of frost heave damage is the radial tensile force generated by the phase-change expansion of water particles. Its evolution conforms to a cumulative pattern: initial discrete initiation, path extension in subsequent cycles, and network formation after multiple cycles. Throughout this stage, tensile cracks remained predominant, followed by shear–tensile composite cracks, with no shear–compression cracks observed. This indicates that frost heave damage is predominantly governed by a tensile failure mechanism. The proportion of fractured bonds exhibited exponential growth with increasing cycle number, demonstrating the cumulative effect of damage. The damage morphology showed a trend evolving from a discrete point-source pattern towards a macroscopic network pattern, with cracks progressively interconnecting.

4.2. Frost Heave Damage Patterns in the Middle-Late Stage of F-T Cycles

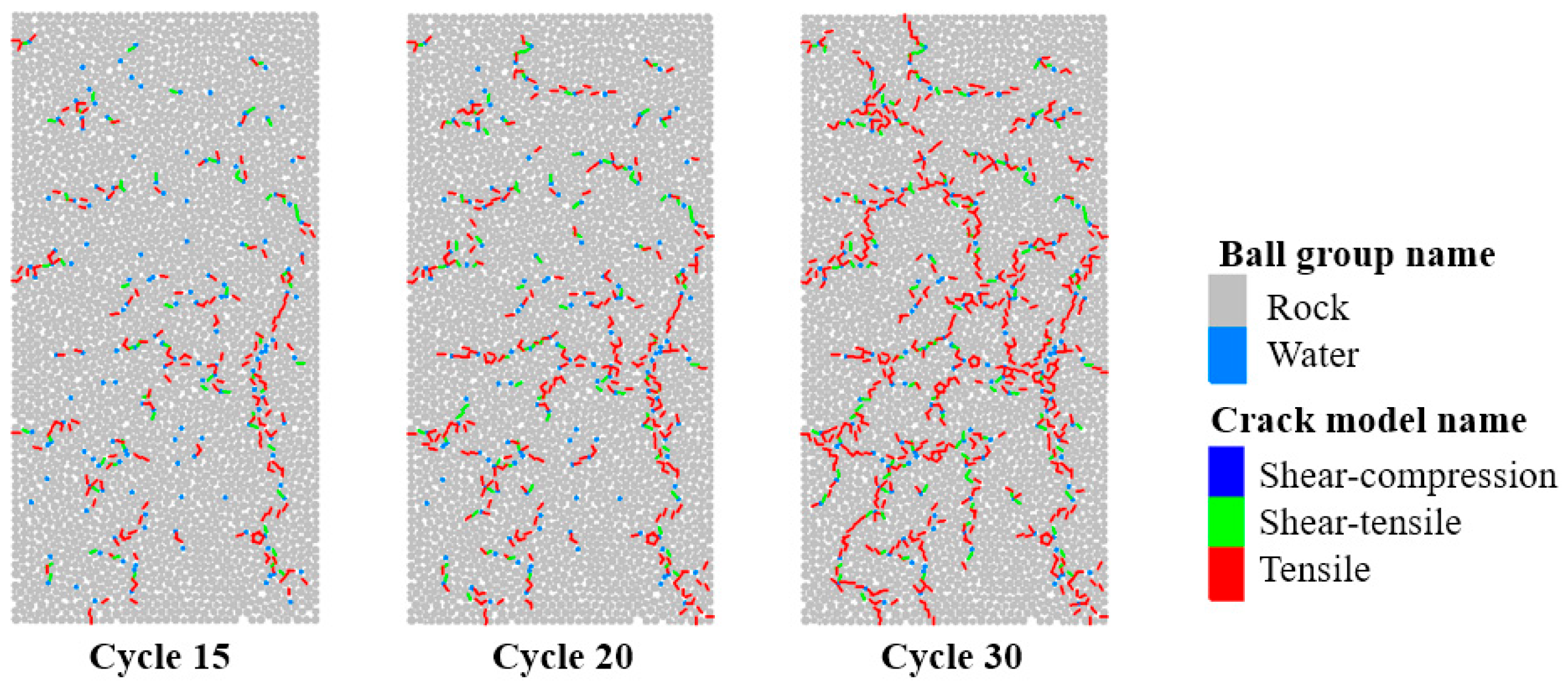

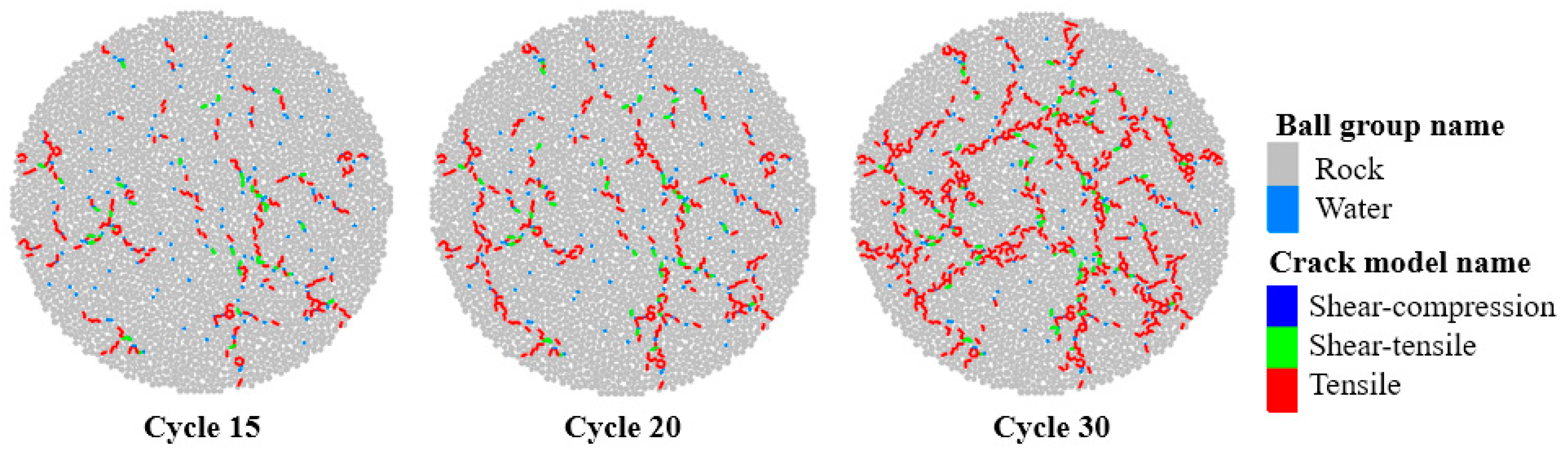

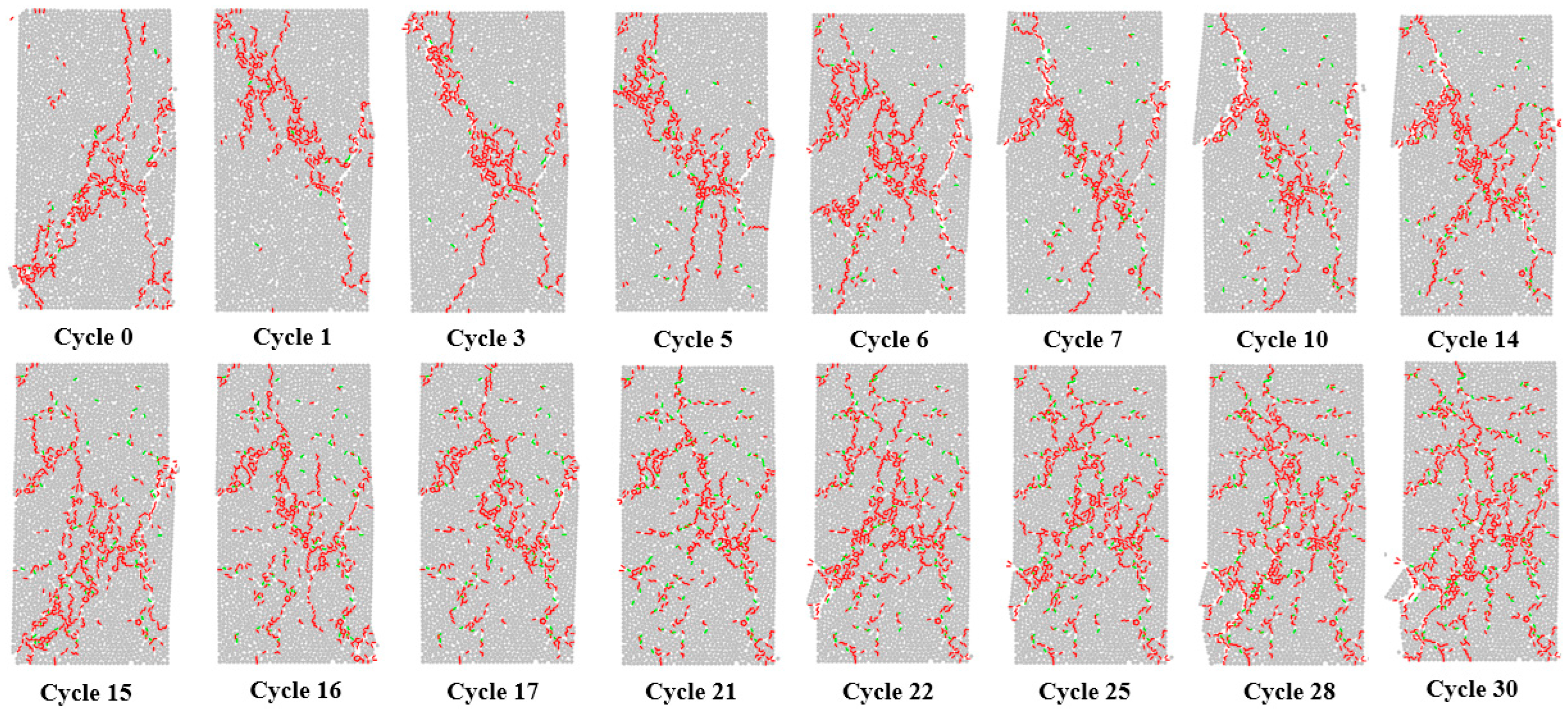

The middle-late stage of F-T cycles, encompassing cycles 15 to 30, represents the critical evolution phase where damage transitions from localized connectivity to macroscopic penetration. Changes in crack distribution and fracture mechanisms directly reflect the cumulative effects of frost heave forces and temperature gradients. Figure 14 and Figure 15 show the crack distribution in the DEM model during the middle-late F-T cycles, revealing a three-stage evolution in crack propagation: branch network formation, accelerated local interconnection, and finally fully interconnected failure.

Figure 14.

Crack distribution in the uniaxial compression model during the middle-late F-T cycles.

Figure 15.

Crack distribution in the Brazilian disk model during the middle-late F-T cycles.

After 15 F-T cycles, cracks had connected the short-range paths from the earlier stage into multi-branch networks. Red tensile cracks still predominated, mainly distributed in water-particle-dense zones and the transition bands from the specimen edges to the center. The proportion of green shear–tensile composite cracks continued to decrease; these cracks mostly formed at crack branches or turning points. This occurs because as frost heave forces propagate along existing cracks, the stress fields of adjacent cracks superimpose, leading to combined shear and tensile stresses. This causes the PBM to experience simultaneous shear and tensile failure. The proportion of fractured bonds was approximately 7.54% at this stage. Although no fully penetrating cracks had yet appeared, a synergistic effect between pore water and the existing crack network had developed. The expansion forces from water particles were transmitted through cracks to more distant regions, driving new bond fractures. Damage entered a stable propagation stage.

After 20 cycles, the crack network became denser, and locally interconnected damage bands began to form. The proportion of fractured bonds increased to 11.70%, and the specimen stiffness decreased significantly. This is because stress was concentrated on the intact rock bridges after crack interconnection. The tensile stress borne by these rock bridges far exceeded their strength threshold, leading to accelerated bond fracture. By 30 cycles, existing cracks had fully penetrated the specimen. Due to the substantial increase in the area of macroscopic damage zones, the number of intact PBM bonds was significantly reduced, and the crack propagation rate began to slow down.

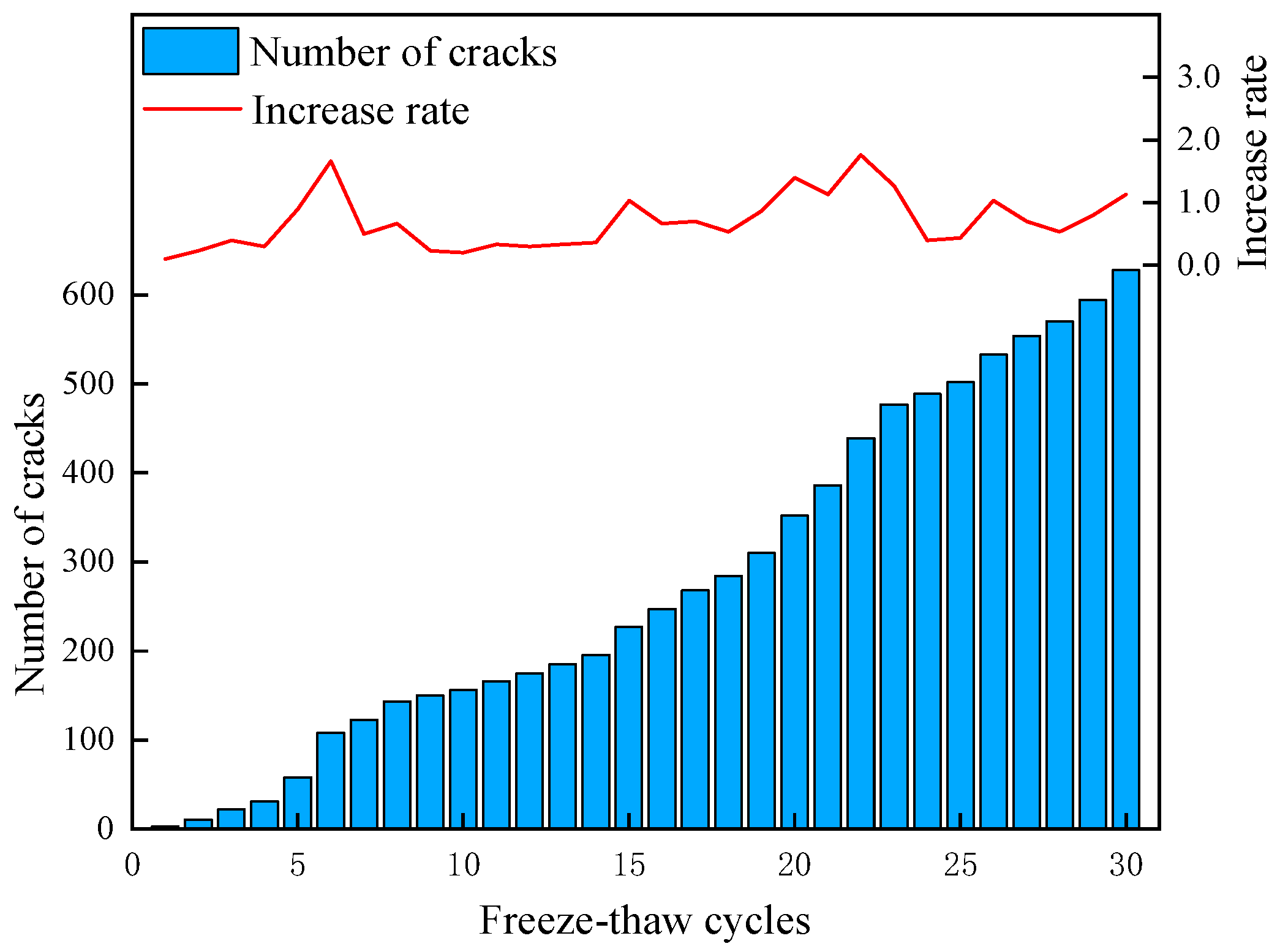

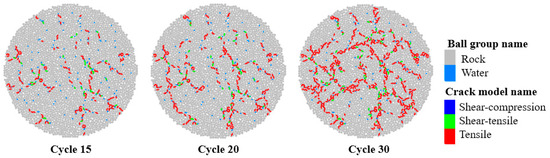

The average crack number and bond fracture growth rate for the uniaxial compression and Brazilian disk models are shown in Figure 16. With increasing cycle numbers, the crack count increased monotonically and cumulatively, while the bond fracture growth rate exhibited a fluctuating trend. The growth rate was significantly higher during the 5th cycle and the 15th to 20th cycles, marking periods of accelerated crack propagation. According to the crack count histogram, the total number of cracks increased from an initial state of 0 to 628 after 30 F-T cycles, demonstrating an irreversible cumulative characteristic, indicating the continuous destruction of the PBM by F-T action. The bond fracture growth rate curve shows that the crack propagation rate was not constant. The growth rate was relatively low during cycles 0~5. After the fifth cycle, the first significant peak in growth rate occurred. The rate then declined during cycles 10~15, before peaking again during cycles 15~20.

Figure 16.

Variation in crack number and bond fracture growth rate within the DEM model.

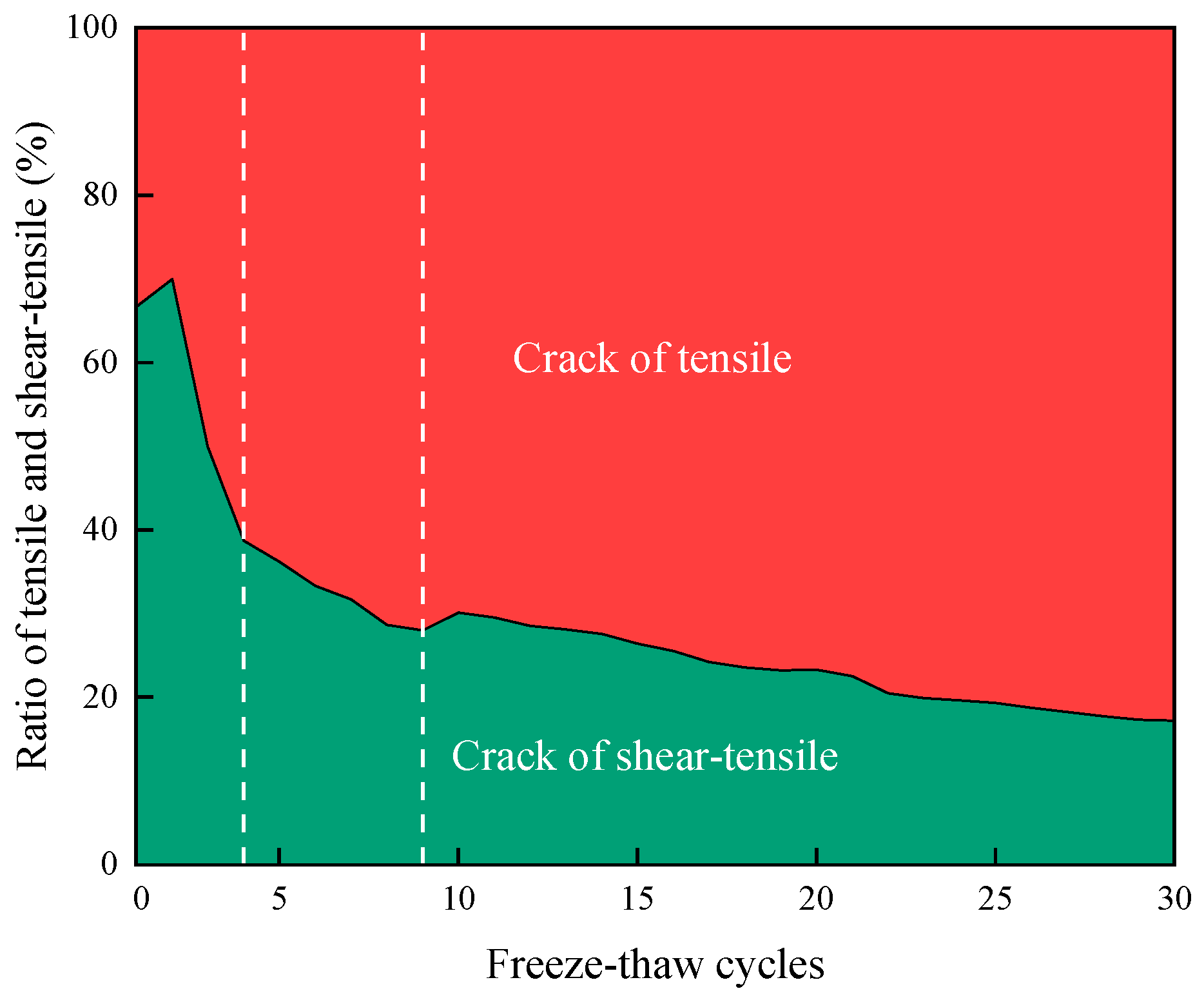

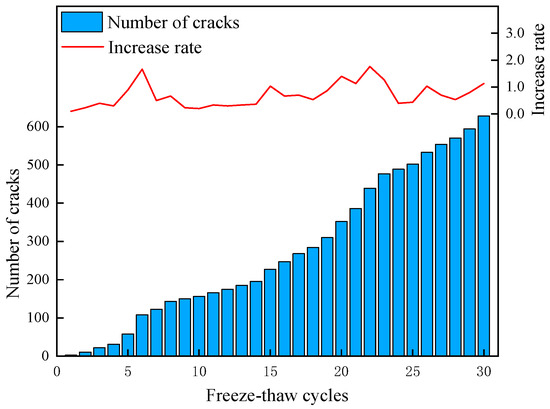

Figure 17 shows the average proportions of different crack types in the two models, where the red area represents tensile cracks and the green area represents shear–tensile composite cracks. The core evolutionary characteristic of their proportions with increasing F-T cycles is as follows: the proportion of tensile cracks showed an overall increasing trend with a gradually slowing growth rate, while the proportion of shear–tensile composite cracks decreased overall with a gradually slowing decline rate. Ultimately, tensile cracks became the overwhelmingly dominant failure mechanism. In the initial stage of F-T cycles, composite cracks accounted for a higher proportion (approximately 75%), while tensile cracks had a lower proportion. As the number of cycles increased, the proportion of tensile cracks gradually expanded. During cycles 5~10, the proportion of tensile cracks rose to approximately 75%, and the proportion of shear–tensile composite cracks decreased to approximately 25%, establishing tensile cracks as the absolutely dominant failure mechanism. Based on the rate of change in crack type proportions, the evolution process can be divided into three stages: initial stage dominated by shear–tensile composite cracks, middle stage with accelerated increase in tensile cracks, and late stage dominated by tensile cracks.

Figure 17.

Proportion of tensile cracks and shear–tensile composite cracks in the DEM model.

5. Degradation Law of Granite Strength After Different F-T Cycles

5.1. Evolution of Uniaxial Compression Failure Modes After Different F-T Cycles

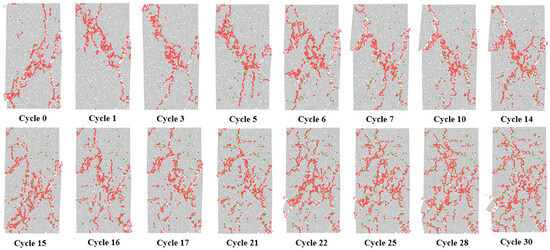

The degradation of the mechanical strength of granite after F-T cycles is a macroscopic manifestation of the cumulative frost heave damage within the rock. Using the PFC5.0 platform, codes for uniaxial compression and Brazilian splitting were developed. Models with established frost heave damage from Section 4 were subjected to loading to test their UCS and BTS. Figure 17 shows the uniaxial compression failure models after F-T cycles. Due to space limitations, specimens exhibiting similar failure patterns were omitted.

As shown in Figure 18, the specimen in its natural state (without F-T cycles) failed along a path from the upper-right to lower-left, maintaining relatively high integrity after being crushed, splitting into three parts under the control of inherent fissures. Microcracks generated after just one F-T cycle significantly altered the failure path from “upper-right to lower-left” to “upper-left to lower-right”. Correlating with the frost heave damage results in Figure 10, this change was induced by two shear–tensile composite cracks generated by frost heave on the upper-left side of the model, which guided crack propagation under uniaxial compression. Before 15 F-T cycles, the failure path remained similar. However, starting from the third F-T cycle, some non-interconnected cracks formed by frost heave damage extended under the influence of uniaxial compression, leading to an increase in the number of penetrating cracks at failure, and the specimen fragmented into five pieces.

Figure 18.

Failure modes of the uniaxial compression model after different F-T cycles.

After 15 F-T cycles, short-range paths had connected into multi-branch networks. Tensile cracks from frost heave were distributed in water-particle-dense zones and transition bands from the specimen edges to the center, while shear–tensile composite cracks were located at crack branches or turning points. The synergistic effect between inherent pores and the frost heave crack network had formed, resulting in significantly reduced integrity during uniaxial compression failure. After 25 F-T cycles, the uniaxial compression failure mode manifested as numerous fragmented pieces, with no distinct failure path. Furthermore, as the number of F-T cycles increased, the specimen integrity upon failure continued to decrease, albeit at a gradually slowing rate.

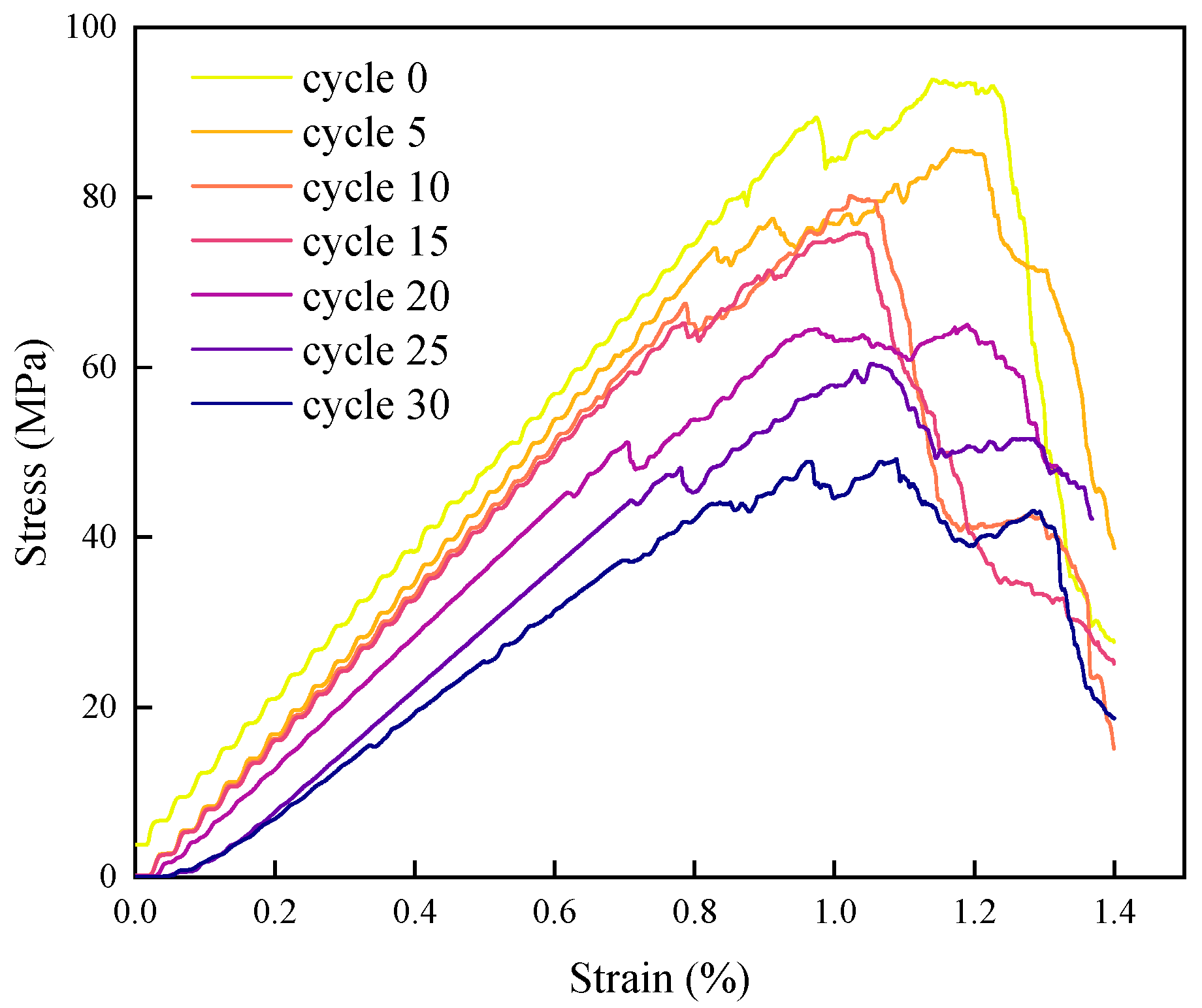

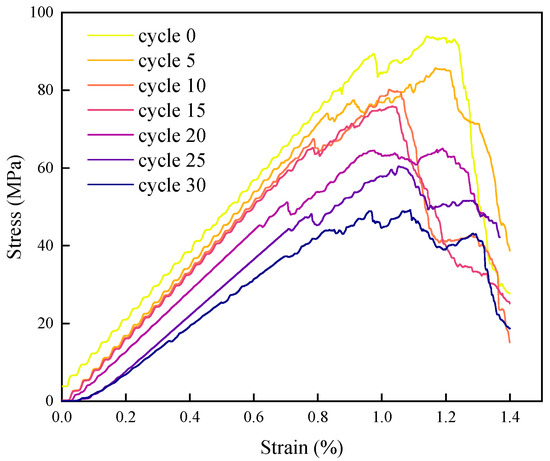

5.2. Degradation Law of Uniaxial Compressive Strength After Different F-T Cycles

To quantitatively characterize the strength degradation law, the partially simulated uniaxial compression stress–strain curves are compiled in Figure 19. It can be observed that the overall curve morphology gradually transitions from the steep, brittle characteristics of the natural state to a flatter, more ductile form, reflecting the progressive weakening of granite’s mechanical properties due to frost heave damage. The specimen in the natural state, unaffected by F-T, exhibited the steepest slope in the elastic stage and a sharp post-peak stress drop. It fractured rapidly upon reaching peak stress, with the failure process almost instantaneous, displaying typical brittle failure. With increasing F-T cycles, the curve morphology changed significantly: the slope of the elastic stage gradually decreased, indicating a continuous reduction in rock stiffness and diminishing resistance to deformation.

Figure 19.

Stress–strain curves of uniaxial compression after different F-T cycles.

The change in peak stress under uniaxial compression more clearly reflects strength degradation. The peak stress in the natural state was as high as 93.7 MPa. After 5, 10, 20, and 30 F-T cycles, the peak stresses gradually decreased to 85.7 MPa, 80.2 MPa, 65.0 MPa, and 49.2 MPa, respectively, with the degradation magnitude increasing. The degradation pattern of peak stress with F-T cycles highly aligns with the cumulative law of bond fracture proportion described in Section 4, directly controlled by the formation of the crack network. Under uniaxial compression, stress concentrates more easily on intact rock bridge regions. When the tensile stress borne by these rock bridges exceeds their strength threshold, the PBM fractures, ultimately leading to macroscopic rock failure and stress curve drop. The evolution of peak strain reflects changes in the rock’s deformation capacity. The natural state had a low peak strain, with negligible plastic deformation before failure. As F-T cycles increased, peak strain gradually increased. This occurs because the crack network disperses stress concentration, preventing rapid propagation along a single path, thereby prolonging the rock’s deformation time. For instance, after 20 F-T cycles, a dense internal crack network had formed. Uniaxial compression caused cracks to propagate and connect slowly, ultimately fragmenting the specimen into numerous small pieces. The failure process shifted from sudden fracture to progressive fragmentation, accompanied by a significant increase in peak strain. Regarding post-peak behavior, the natural specimen exhibited a steep post-peak curve, indicating almost instantaneous loss of load-bearing capacity upon failure. With increasing F-T cycles, the post-peak curve gradually flattened, signifying that the rock could still sustain some load after initial failure. This ductile transition stems from the buffering effect of the crack network. Sections of the specimen partitioned by cracks bear loads independently, avoiding concentrated stress release and thus prolonging the failure process.

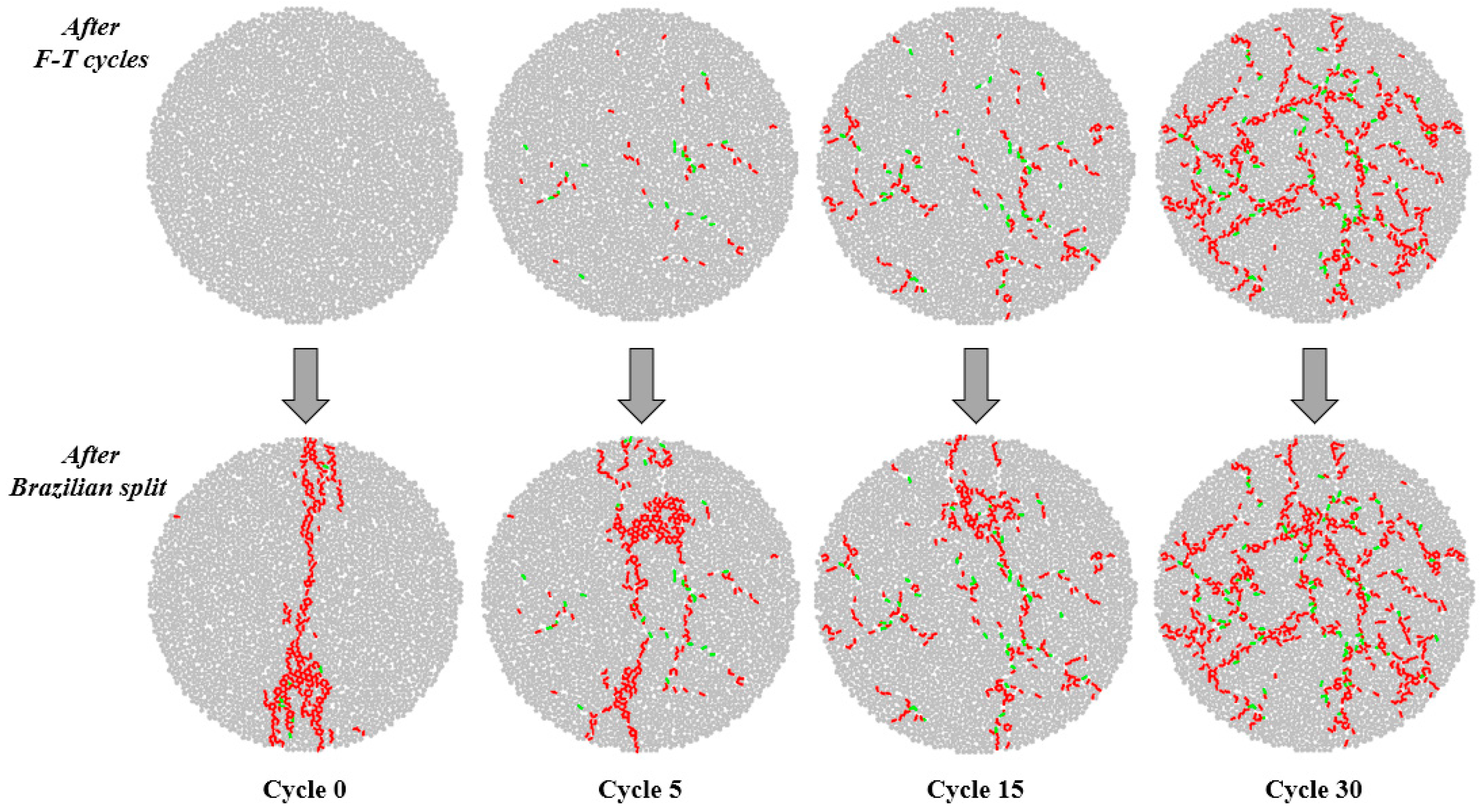

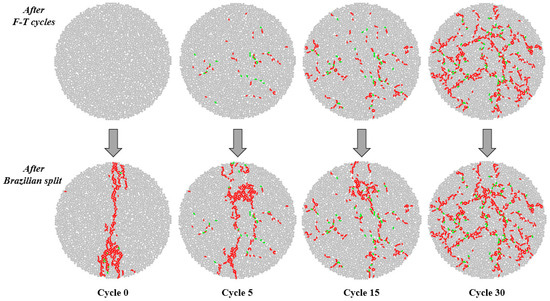

5.3. Evolution of Brazilian Splitting Failure Modes After Different F-T Cycles

To investigate the macro–micro correlation between freeze–thaw damage and the tensile failure behavior of granite, Brazilian disk models and their splitting failure modes after different F-T cycles are compiled in Figure 20. In the natural state, the disk model contained only initial interparticle pores, with no F-T-induced microcracks. Its splitting failure exhibited a typical single dominant crack penetrating along the loading diameter, neatly splitting the specimen into two halves with high post-failure integrity. After five F-T cycles, localized tensile damage caused by frost heave forces led to the formation of discrete point-source cracks, which acted as stress concentration points during Brazilian splitting loading. Although failure was still dominated by a single main crack, its path exhibited slight deflection, and a few secondary cracks were induced at its tip and flanks, increasing the number of fragments. This indicates that initial frost heave damage had begun to interfere with the internal stress field, guiding changes in the failure path.

Figure 20.

Brazilian disk models and splitting failure modes after different F-T cycles.

After 15 F-T cycles, the microscopic damage within the model underwent a qualitative change. Discrete cracks propagated and connected to form a short-range continuous fracture network. Consequently, during splitting loading, the propagation of the main crack was constantly guided by the pre-existing F-T crack network, generating numerous secondary branch cracks. This ultimately divided the specimen into more than five fragments. Correspondingly, the macroscopic failure mode of the Brazilian splitting test changed significantly, transitioning from single dominant crack failure to a multi-crack, net-like composite failure. After 30 F-T cycles, microcracks had completely interconnected into a dense network, saturating the specimen with tensile cracks, severely weakening interparticle bond integrity. Splitting loading could no longer form a dominant penetrating main crack. Failure transitioned to concurrent propagation and interconnection of multiple cracks controlled by the F-T crack network, resulting in the specimen being completely shattered.

Under the action of F-T cycles, frost heave damage continuously intensifies the internal microcrack network, altering the failure mode of granite under tensile stress. This transition progresses from a singular, concentrated brittle fracture to a diffuse, fragmented composite failure. It is also notable that even when internal damage from F-T is severe, the primary crack propagation region remains concentrated near the loading diameter. This indicates that the tensile stress concentration induced by external loading remains the direct driving force triggering the ultimate failure of the rock.

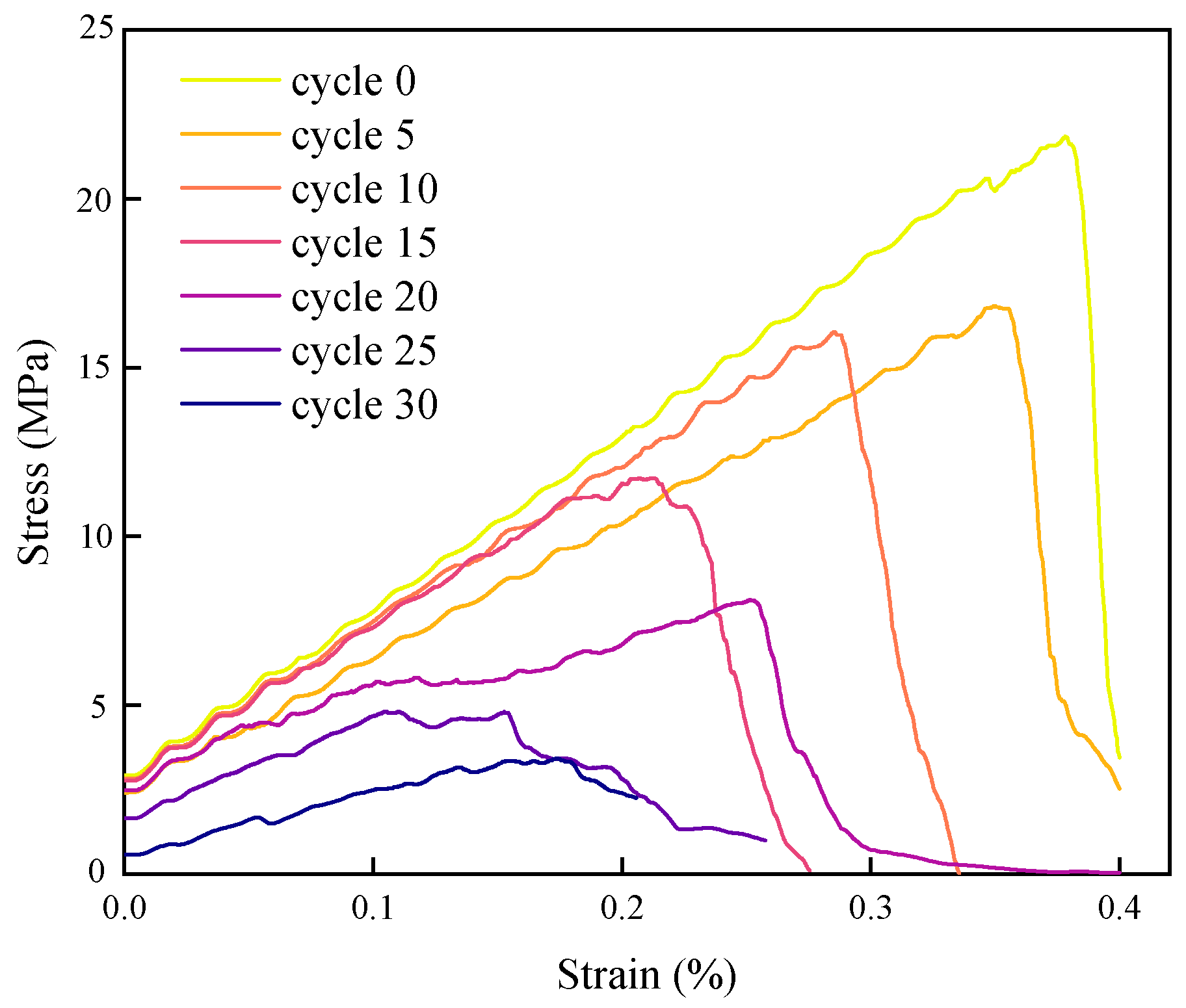

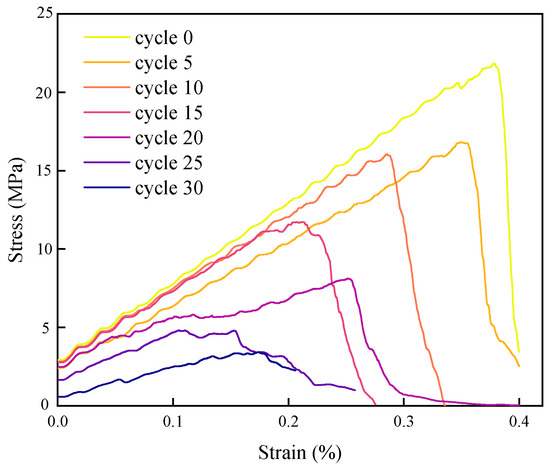

5.4. Degradation Law of Tensile Strength After Different F-T Cycles

Figure 21 shows the stress–strain curves under Brazilian splitting conditions for models subjected to different numbers of F-T cycles. The observed changes correspond to the evolution of failure modes described in Section 5.3. The curve for the natural state exhibits typical brittle tensile characteristics: a steep elastic slope, a high peak stress reaching 22 MPa, and a sharp post-peak drop. This indicates the absence of initial damage within the specimen, intact PBM bonds, and tensile stress concentrating at the center of the loading diameter, causing instantaneous penetration failure via a single main crack. As F-T cycles increased to 15~20, the elastic slope changed little, but peak stress dropped to 12 MPa. The post-peak curve exhibited a degree of ductility. This is attributed to the formed crack network dispersing the tensile stress generated by splitting loading, preventing concentration along a single path. The net-like composite failure resulted in the specimen breaking into more fragments, manifesting as an extended softening phase in the post-peak curve. After 25 F-T cycles, the stress–strain curve morphology underwent a fundamental change: the elastic slope decreased significantly, and peak stress plummeted to less than 5 MPa. At 30 F-T cycles, peak stress was only 1.37 MPa, representing a 93.8% degradation compared to the natural state. The post-peak curve approximated a plateau phase, indicative of shattering failure without a dominant direction.

Figure 21.

Stress–strain curves of Brazilian splitting after different F-T cycles.

The changes in stress–strain curves under Brazilian splitting reveal the degradation law of granite tensile strength due to F-T cycles. As the number of F-T cycles increases, the elastic modulus and peak tensile strength of the rock continuously decrease, while its deformation capacity increases, and the failure mode transitions from brittle to ductile. The essence of these changes lies in the accumulation of frost heave damage. The crack network formed by bond fractures between rock particles, driven by the phase-change expansion of water particles, significantly alters the overall mechanical characteristics of the Brazilian disk model. The mid-stage of F-T cycles (15~20 cycles) is the critical period for strength degradation. During this stage, cracks transition from short-range paths into multi-branch networks, forming a synergistic effect between inherent pores and the frost heave crack network, leading to accelerated loss of rock strength.

6. Conclusions

Based on the Discrete Element Method, this study systematically investigated the damage evolution and mechanical property degradation of granite under F-T cycles by establishing a saturated granite frost damage model that accounts for the volume effect of water–ice phase transition. The main conclusions are as follows:

- Thermodynamic parameters were calibrated through laboratory experiments, ensuring the reliability of the DEM model for effectively simulating heat transfer during F-T cycles. The temperature field simulation results clearly revealed the non-uniform temperature distribution characteristics and geometric dependency of both models during freezing and thawing, laying a reasonable foundation for frost heave damage analysis.

- The damage evolution of granite under F-T cycles exhibits distinct stage characteristics. In the initial stage, damage manifests as localized tensile fracture of bonds surrounding water particles, forming discrete point-like cracks. As the number of cycles increases, cracks gradually propagate and connect to form short-range continuous fracture networks. Ultimately, the damage develops into penetrating damage bands, leading to a significant loss of model integrity. Tensile cracks dominate the crack types, and their proportion continuously increases with the number of F-T cycles, indicating that tensile failure is the dominant mechanism of frost heave damage.

- F-T cycles lead to the degradation of granite’s mechanical properties. Both the UCS and the BTS continuously decrease with increasing F-T cycles. Tensile strength demonstrates higher sensitivity to F-T damage, exhibiting a substantial reduction of up to 93.8% after 30 F-T cycles. The essence of strength degradation lies in the F-T-induced fracture of interparticle bonds and the continuous accumulation of microscopic damage. Macroscopically, this manifests as a transition in mechanical behavior from brittle to ductile, and a shift in failure mode from dominant crack penetration to multi-crack networked failure.

- The statistical method based on the fracture of interparticle contact bonds adopted in this article can characterize the initiation and propagation of micro-cracks in porous media. This Discrete Element Method provides a certain reference for analyzing the spatiotemporal evolution law of frost heave damage. And the specific accuracy still needs to be further verified by combining with the AE technology in laboratory tests.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S. and Y.B.; methodology, J.H.; software, Y.B.; validation, J.H., H.Y. and P.Z.; resources, P.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.S.; visualization, Y.B. and H.Y.; supervision, J.H.; project administration, Y.S.; funding acquisition, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52574106.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yingxiang Sun was employed by the company Zhaojin International Gold Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Yavuz, H.; Altindag, R.; Sarac, S.; Ugur, I.; Sengun, N. Estimating the index properties of deteriorated carbonate rocks due to freeze-thaw and thermal shock weathering. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2006, 43, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Chang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Y. The failure behavior of prefabricated fractured sandstone with different rock bridge inclination angles under freeze-thaw cycles. Unconv. Resour. 2025, 6, 100152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Song, Y.; Wang, X.; Ren, J. Multi-dimensional real-time data-driven identification for progressive fracturing characteristics of sandstone under freeze-thaw cycles and seepage-stress coupling. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 152, 110803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, L.; Tao, Z.; Yang, X.; Du, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Ding, C.; et al. “Excavation-freezing-thawing” failure and crack characteristics of open-pit slope in cold regions: A case study in Baorixile mine, Hulunbeir, China. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2025, 84, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, P.; Tang, L.; Zheng, J.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Jin, L.; Yu, Y.; Duan, X. Experimental investigations on the shear strength and creep properties of soil-rock mixture under freeze-thaw cycles. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2024, 217, 104037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lai, Y.; Zhang, X.; Pu, Y.; Yu, W. Study on the damage propagation of surrounding rock from a cold-region tunnel under freeze-thaw cycle condition. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2004, 19, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, F. Predicting mechanical strength loss of natural stones after freeze-thaw in cold regions. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2012, 83–84, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesa, P.A. Freezing-Induced Strains and Pressures in Wet Porous Materials and Especially in Concrete Mortars. Adv. Cem. Based Mater. 1998, 7, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Jin, X.; He, J.; Li, H. Experimental studies on the pore structure and mechanical properties of anhydrite rock under freeze-thaw cycles. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2022, 14, 781–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Cao, S.; Zhou, K.; Lin, Y.; Zhu, L. Damage characteristics and energy-dissipation mechanism of frozen-thawed sandstone subjected to loading. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2020, 169, 102920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, J.; Goto, T.; Fujii, Y.; Hagan, P. The effects of water content, temperature and loading rate on strength and failure process of frozen rocks. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2013, 62, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, K.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y. Analysis of the effect of freeze-thaw cycles on the degradation of mechanical parameters and slope stability. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2018, 77, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walbert, C.; Eslami, J.; Beaucour, A.L.; Bourges, A.; Noumowe, A. Evolution of the mechanical behaviour of limestone subjected to freeze-thaw cycles. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 6339–6351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Zhou, J.-W.; Cai, Y. Effect of Freeze-Thaw Cycles on Mechanical Properties and Permeability of Red Sandstone under Triaxial Compression. J. Mt. Sci. 2015, 12, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.C.; Liu, C.; Tang, C.; Zhang, X.; Shi, B. Numerical Simulation of Desiccation Cracking in Clayey Soil Using a Multifield Coupling Discrete-Element Model. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2022, 148, 04021183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Du, R.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, X. Experimental study and numerical simulation verification of the macro- and micromechanical properties of the sandstone-concrete interface under freeze-thaw cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 432, 136584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yan, Z.; Wang, F.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, P.; Ben, L. Freeze-thaw damage mechanism of self-compacting concrete with different RAP contents by experiment and DEM simulation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 486, 141967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Chen, W.; Yang, J.; Cao, J. Laboratory investigations on the mechanical properties degradation of granite under freeze-thaw cycles. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2011, 68, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.M.; Meschke, G. A three-phase thermo-hydro-mechanical finite element model for freezing soils. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2013, 37, 3173–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockner, D.A. The role of acoustic emission in the study of rock fracture. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1993, 30, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.P.; Bin, L.I.; Jie-Lin, L.I.; Deng, H.W.; Bin, F. Microscopic damage and dynamic mechanical properties of rock under freeze-thaw environment. Trans. Nonferr. Metal. Soc. 2015, 25, 1254–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; You, R.; Lv, W.; Sui, Q.; Yan, Y.; Zhu, H. Damage Evolution and Acoustic Emission Characteristics of Sandstone under Freeze-Thaw Cycles. ACS. Omega. 2024, 9, 4892–4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnaka, M. The Physics of Rock Failure and Earthquakes; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Chen, T.; He, B.; Li, Y. Study of the Relationship Between the Attenuation Pattern of Acoustic Emissions and Stress Levels After a Blasting Disturbance. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 10085–10103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Zhang, Z.; Li, B.; Li, K. Study on Numerical Simulation of Geometric Elements of Blasting Funnel Based on PFC5.0. Shock Vib. 2021, 2021, 8812964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhu, C.; Ma, Y.; Hewage, S.A. Investigating Mechanical Behaviors of Rocks Under Freeze–Thaw Cycles Using Discrete Element Method. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2022, 55, 7517–7534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Qiu, W.; Xie, K.; Xing, M.; Zhu, H.; Huang, S. A discrete element-based study of freeze–thaw damage in water-filled fractured rock. Comput. Geotech. 2025, 185, 107343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Brian, P.; Yu, S.; Yu, J.; Li, Y.; Gu, P. Numerical Simulation of Freezing-Induced Crack Propagation in Fractured Rock Masses Under Water–Ice Phase Change Using Discrete Element Method. Bulidings 2025, 15, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Dai, B.; Zhao, G.; Chen, Y.; Tian, Y. A Novel Method of Calibrating Micro-Scale Parameters of PFC Model and Experimental Validation. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Filgueira, U.; Alejano, L.R.; Arzúa, J.; Ivars, D.M. Sensitivity Analysis of the Micro-Parameters Used in a PFC Analysis Towards the Mechanical Properties of Rocks. Procedia Eng. 2017, 191, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, H.; Tan-Tan, Z. Experimental and numerical study on the strength and hybrid fracture of sandstone under tension-shear stress. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2018, 200, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaei, C.; Hazzard, J.; Chalaturnyk, R. Discrete Element Modeling of Stick-Slip Instability and Induced Microseismicity. Pure Appl. Geoph. 2016, 173, 775–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).