Abstract

Cookies are widely consumed bakery products valued for their pleasant taste and texture; however, their high fat content contributes significantly to their caloric density and cardiovascular diseases. Therefore, the development of alternatives for replacement of saturated and trans fatty acids in bakery goods has attracted considerable scientific interest. In this study, the potential application of structured emulsion supplemented with blackcurrant pomace (EBP) as saturated fat (margarine) replacer in shortbread cookies was investigated by employing black currant pomace/rapeseed oil/water (15/30/55 w/w/w) emulsion to replace margarine in cookies at 50 and 70% substitution; full-fat cookies were also tested as a control. With increasing EBP substitution level, the cookie diameter decreased, thickness and hardness increased, and a lower color lightness was noted. Meanwhile, total phenolic content was greater for the EBP-fortified cookies than the control. Nevertheless, the 50% margarine substituted cookie received acceptable ratings for odor, flavor, hardness, fragility, and overall acceptability by sensory evaluation. This indicates that the use of EBP as substitute of solid fats in cookies offers the advantage of producing healthier and more acceptable products depending on the degree of fat replacement.

1. Introduction

Cookies are widely consumed bakery products appreciated for their palatable taste and convenient shelf-stable format. However, their high fat content, particularly from solid fats like margarine or butter, contributes significantly to energy density and the intake of saturated and trans fatty acids. These compounds are associated with adverse health outcomes, including elevated cardiovascular disease risk [1,2]. Excessive intake of saturated fats continues to be a major dietary challenge in Europe, highlighting the importance of aligning fat consumption with established nutritional guidelines [3]. With growing global attention on reducing dietary intake of saturated fats, research efforts in recent years have increasingly focused on developing alternative strategies to replace saturated and trans fatty acids in bakery formulations [4]. According to the European Food Safety Authority, the intake of saturated and trans fatty acids should be minimized as much as possible within a nutritionally balanced diet, since these compounds increase LDL cholesterol levels and thereby elevate cardiovascular disease risk [3]. There is growing scientific and industrial interest in the development of healthier bakery formulations that maintain sensory quality while improving nutritional profiles [4].

When solid fats in cookies are replaced with liquid or semi-solid fat systems, the products may exhibit increased perceived greasiness, reduced crispness, and decreased oxidative stability [5]. Therefore, in recent years, increasing attention has been given to identifying new methods for replacing traditional solid baking fats (such as margarine or butter), saturated fatty acids, and trans fats with healthier fat sources or alternative ingredients offering an improved fatty acid profile with favorable sensory properties [6].

Among emerging strategies, partial or complete replacement of solid fats with plant-based structured emulsions has gained interest [6,7]. Oil-in-water (O/W) emulsions stabilized with natural fiber-rich by-products present a promising alternative [8,9]. In particular, fruit and berry pomace—by-products of juice production—offer functional components such as pectin, polyphenols, and dietary fiber [10,11]. These components can contribute to emulsion stabilization, improve rheological behavior, and enhance the nutritional and antioxidant profile of the final product [12,13]. The main insoluble fibers of fruit and berry pomace are cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, while the majority of soluble viscous fibers consist of pectins, which can be used in various food products as a gelling agent, emulsifier, and thickener—for example, in bakery, confectionery, jellies, yogurts, and beverages [14]. Pomace and dietary additives can be incorporated into conventional or Pickering-type, structured emulsions to improve their rheological properties and stability [8]. Apple pomace-based emulsions have also been explored as alternatives to saturated fats in biscuit formulations, demonstrating the potential to enhance nutritional value while preserving desirable technological and sensory properties [14].

Black currant (Ribes nigrum) pomace, a rich source of insoluble and soluble dietary fibers, vitamins, polyphenols, and anthocyanins, has shown potential as a natural structuring and functionalizing agent in food formulations [15,16,17] as berry and fruit pomaces are no longer seen as a by-product and is further processed as a value-added food ingredient [18]. Therefore, blackcurrant pomace can be utilized as a functional ingredient in conventional or Pickering-type emulsions, where it enhances the rheological behavior and improves the overall stability of the dispersed systems.

Recent advances in emulsion technologies, including the development of Pickering-type emulsions stabilized by solid particles, have enabled novel fat-replacement systems in baked goods. Such systems may help mitigate the technological drawbacks commonly associated with fat reduction, such as increased hardness, loss of spread, and reduced oxidative stability [8,19,20]. Pomace-stabilized emulsions differ from conventional emulsifier-based systems by providing greater resistance to droplet coalescence and enabling the encapsulation and controlled release of bioactive compounds [21]. Moreover, polyphenol-rich matrices such as black currant pomace may impart antioxidant benefits and increase the biofunctional value of the final product enriching it by soluble and insoluble dietary fiber. Blackcurrant pomace is a rich source of dietary fiber, primarily in its insoluble form [22], which supports digestive function, while the soluble fraction helps regulate blood glucose and cholesterol levels, promotes gut microbiota balance, and enhances the texture of food products [10]. The World Health Organization and the European Food Safety Authority recommend a daily dietary fiber intake of approximately 25 g per person; however, actual intake levels in many populations remain considerably lower than this guideline [23,24].

Thus, by utilizing black currant pomace to structure the emulsion (EBP), its incorporation into shortbread cookie formulations enables the development of fiber-enriched products with reduced saturated fat content through the partial replacement of conventional fats. This novel approach may serve as a clean-label alternative with the potential to improve product stability and maintain desirable sensory properties, thereby addressing the texture challenges commonly observed in fat-reduced cookies. Nevertheless, although several studies have investigated conventional fat replacers, there is a lack of information on pomace-stabilized emulsions, particularly those based on blackcurrant pomace [25,26].

In this context, the present study aimed to investigate the potential of EBP as a partial margarine replacer in cookie formulations. The EBPs were evaluated for their thermal and static stability; effects on dough rheology; and impact on cookie quality, including physical, textural, nutritional, and sensory characteristics. This study also assessed the oxidative stability and total phenolic content of the resulting cookies. This research provides insight into the use of food industry by-products in sustainable bakery innovations and offers a pathway for the development of nutritionally improved cookie products.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Black Currants Pomace

Blackcurrant pomace was sourced from a local producer, UAB MV GROUP Production (Vilnius, Lithuania), as a by-product remaining after juice extraction. Before analysis, the pomace was dried at 35–40 °C for 48 h until it reached a moisture content of 7.97%, and subsequently ground in a Retsch ZM200 laboratory cyclone mill (Retsch GmbH, Haan, Germany) to obtain a particle size of 0.2 mm. The composition of the pomace, expressed per 100 g of dry weight, was as follows lipids 12.20 g (of which saturated fatty acids 1.06 g), carbohydrates 65.18 g (of which sugars 2.71 g), dietary fiber 62.10 g in total (6.1 g soluble and 56.0 g insoluble), protein 14.80 g, salt 0.03 g, and minerals 2.70 g.

2.2. Preparation of O/W Structured Emulsions Supplemented with Black Currant Pomace

For O/W structured emulsion preparation, 30 g (dry weight basis) of black currant pomace powder was mixed with 110 g of water preheated to 60 °C and dispersed for 5 min using an IKA T 18 digital ULTRA-TURRAX disperser (IKA-Werke GmbH & Co., KG, Staufen, Germany) at 10,000 rpm. Subsequently, 60 g of refined rapeseed oil (SV Obeliai, Obeliai, Lithuania) was gradually added to the obtained dispersion and further dispersed for 4 min at 10,000 rpm. The emulsion was then cooled in a Metos rapid cooling cabinet (Metos Oy AB, Kerava, Finland) at 3 °C until it reached room temperature. A probe thermometer ETI CaterTemp (ETI Ltd., Worthing, UK) was used for temperature monitoring throughout the process [14].

2.3. Roduction of Shortbread Cookies with the Additives of O/W Structured Emulsion Supplemented with Black Currant Pomace

Shortbread cookies were prepared using a modified procedure based on the method described by Sereti et al. [14]. All main ingredients were purchased from local suppliers: wheat flour 550D from Malsena plius, Ltd. (Malsena Plius, Panevėžys, Lithuania), baking margarine from Lidl Stiftung & Co., (Lidl Stiftung & Co. KG, Neckarsulm, Germany) (composed of palm and coconut fats, drinking water, rapeseed oil, emulsifiers: lecithins, mono- and diglycerides of fatty acids; 0.2% salt, flavoring, citric acid, retinyl palmitate, cholecalciferol, and carotene), powdered sugar (Belbake, Lidl Stiftung & Co., containing corn starch), baking powder (Dr. Oetker Baltic, containing leavening agents, wheat flour, and starch), low-fat cocoa powder (Belbake, Lidl Stiftung & Co., containing potassium carbonate as an acidity regulator), and refined rapeseed oil (SV Obeliai, Lithuania).

For the experimental doughs, 50% and 70% of the baking margarine was replaced with O/W structured emulsion supplemented with black currant pomace (EBP). The control dough was prepared without the structured emulsion. All required quantities of margarine, structured emulsion, powdered sugar, and cocoa were weighed and whipped in a KitchenAid Classic planetary mixer (Whirlpool Corporation, Benton Harbor, MI, USA) for 25 min. Wheat flour, baking powder, and water were then incorporated, and the mixture was mixed until a homogeneous dough was obtained. The shortbread cookie formulations are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The shortbread cookie formulations (%).

Shortbread cookies were shaped manually using a round metal cutter (60 mm diameter), placed on baking trays lined with parchment paper, and baked in an Alto-Shaam convection oven (Alto-Shaam, Inc., Menomonee Falls, WI, USA) at 160 °C for 10 min. After baking, cookies were cooled to ambient temperature prior to quality and sensory assessments.

For texture analysis during storage, cookies were packaged in groups of three in paper bags (22 × 12.5 cm, Aromata, AEC Sp. z o.o., Quezon City, Philippines) and stored at room temperature (~22 °C) ambient relative humidity (45–55%) for 49 days (7 weeks).

2.4. Evaluation of Static and Thermal Stability of O/W Structured Emulsions Supplemented with Black Currant Pomace

To assess structured emulsion stability under static (storage) conditions, immediately after preparation, the emulsion was transferred into graduated test tubes (10 mL each) and stored at 4 °C for 3 weeks, monitoring the volumes of separated serum and the remaining stable emulsion. Emulsion stability was evaluated visually according to the methodology described by Huang et al. [9]. The stability of the emulsion was expressed as the percentage ratio of the stable phase volume to the total sample volume and computed as shown in the following equation:

where VE—volume of the emulsion phase, mL; VB—total sample volume, mL.

ES, % = (VE/VB) × 100

Thermal stability evaluation involved heating the emulsions at 80 °C for 30 min in a water bath, cooling them to ambient temperature, and storing them at 4 °C for 7 weeks. The volumes of both separated serum and the stable emulsion fraction were measured throughout the storage period. Thermal stability was quantified as the percentage of the stable emulsion in relation to the total sample volume (Equation (1)).

2.5. Evaluation of Dough Texture

Dough texture parameters were determined using a TA.XT plus texture analyzer (Stable Micro System, Godalming, UK). Measurements were performed using a glass vessel and an aluminum cylinder with a diameter of 20 mm. A 50 g portion of dough was placed into the vessel and pressed against the walls and bottom to eliminate air gaps. The distance between the vessel and the measuring cylinder was kept constant. The sample was subjected to shear force for several seconds, and dough hardness, consistency, adhesiveness, and cohesiveness were determined.

2.6. Determination of Color Characteristics of Shortbread Cookie

The color of shortbread cookies was measured using a Konica Minolta colorimeter (Tokyo, Japan). Color evaluation was based on the CIE (Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage) Lab* system, where L* represents lightness, a* indicates redness, and b* denotes yellowness. The colorimeter was placed on the cookie sample so that the measurement aperture was in full contact with the sample surface, and the measurement was then taken.

2.7. Determination of Shape and Textural Properties of Shortbread Cookie

Analysis of cookie quality parameters was carried out 3–4 h after baking as previously described by Pradhan et al. [27]. The diameter and height of the cookies were determined with a ruler, and the spread ratio (SRA) was computed according to the following formula:

where WAv is the average width of cookies, and TAv is the average thickness of the cookies.

SRA = WAv/TAv

The textural properties of the cookies were evaluated following the method described by Gutiérrez-Luna et al. [28] with slight modifications, the texture of the cookies was analyzed using a TA.XT Plus texture analyzer (Stable Micro Systems, Godalming, UK) with the three-point bending test. During the test, the cookies were bent at a constant speed of 1.0 mm/s until breakage, and texture parameters such as hardness and distance to break were recorded [14]. Texture measurements were conducted after 1, 3, 5, and 7 weeks of storage at room temperature to assess variations in texture parameters during the storage period.

2.8. Evaluation of Sensory Analysis of Shortbread Cookie

A panel of 27 evaluators aged between 20 and 50 years participated in the sensory evaluation of cookies and overall acceptability assessment according to ISO 6658 [29]. Sensory evaluation was conducted 3–4 h after baking, when the cookies had cooled to room temperature. The appearance, overall aroma, hardness, crispness, overall taste, sweetness, additive flavor acceptability, and overall acceptability of the baked products were evaluated using a 7-point hedonic scale, where 1 corresponded to “dislike extremely” and 7 to “like extremely”.

2.9. Calculation of the Nutritional Composition of Shortbread Cookies

The amount of a nutrient supplied by a raw material per 100 g of product was calculated by multiplying the quantity of the raw material in 100 g of product by the nutrient content of the raw material (%) and dividing by 100% [30].

The energy value (kcal/100 g of product) was calculated by multiplying the nutrient content of the raw material (%) by the conversion factor K (proteins—4, fats—9, carbohydrates—4, dietary fiber—2). The energy value in kJ was obtained by multiplying the resulting sum by 4.19, the equivalent of 1 kcal.

2.10. Determination of Oxidative Stability of Fats in Shortbread Cookies

The effect of black currant pomace-stabilized O/W structured emulsions on the oxidative stability of cookie lipids was evaluated using the Oxipres method with an ML Oxipres apparatus (Mikrolab Aarhus A/S, Aarhus, Denmark), which determines the induction period (IP) [31]. For this purpose, 22–35 g of cookie sample (weighed to an accuracy of 0.001 g) was placed in the reaction cell. Oxidation was assessed at a temperature of 120 °C under an oxygen pressure of 0.5 MPa (5 bar). The oxidation of the sample is graphically recorded and IP is defined as the time elapsed from the test start to a decrease in oxygen pressure.

2.11. Determination of Phenolic Compound Content in Shortbread Cookies

Total phenolic content (TPC) was determined in black currant pomace and cookies according to Singleton et al. [32] with slight modification and expressed in milligrams of Gallic acid equivalents per gram of sample (mg GAE/g).

10 g of the ground sample was weighed into test tubes with an accuracy of 0.01 g and extracted with solvent (50% MeOH/HCl) at a ratio of 1:3 (30 mL) for cookies and 1:4 (40 mL) for pomace. The mixtures were vortexed and then placed in an orbital shaker–incubator for shaking at 250 rpm for 30 min at 45 °C. After shaking, the samples were centrifuged for 30 min at 4 °C at 5000 rpm.

For cookie extracts, 250 µL of the obtained extract was combined with 1.25 mL of working Folin–Ciocalteu’s reagent and 1 mL of Na2CO3 solution. In the case of pomace samples, 1 mL of extract was first diluted with 300 mL of 50% MeOH/HCl solvent; subsequently, 250 µL or 125 µL of this mixture was added to 1.25 mL of Folin–Ciocalteu’s reagent and 1 mL of Na2CO3. Control samples were prepared in parallel by mixing 1 mL of Na2CO3 with 0.25 mL of the solvent (50% MeOH/HCl). All tubes were incubated in the dark for 30 min.

From each glass test tube, 2 mL of cookie or pomace mixture was transferred into capped plastic tubes and centrifuged for 5 min at 14,000 rpm. Absorbance values of the test and control samples were measured with spectrophotometer (Thermo Electron LED GmbH, Langenselbold, Germany) at a wavelength of 765 nm.

The calibration curve was prepared using standard solutions of gallic acid at different concentrations (0.010, 0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.35 mg/mL).

2.12. Statistical Analyses

All experimental measurements were performed in triplicate. The results were expressed as mean values with standard deviations, calculated using Microsoft Excel 2019 (Microsoft Corp., Albuquerque, NM, USA). Statistical analysis was carried out using Statgraphics Centurion 19 software. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to determine differences among sample groups, and Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) post hoc test was applied to identify statistically significant differences at a confidence level of p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Static and Thermal Stability of Structured Emulsions Supplemented with Black Currant Pomace

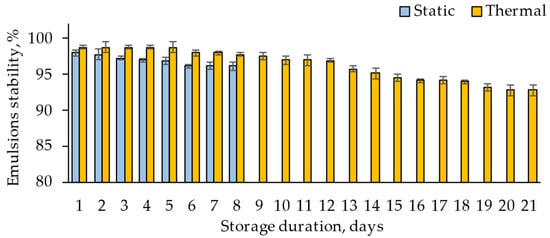

The results of the static and thermal stability evaluation of EBP are presented in Figure 1. Evaluation of the stability of EBP revealed that thermal treatment at 80 °C had a significant effect on serum separation and overall structured emulsion stability during storage. Emulsions that were not thermally treated demonstrated lower stability compared to those subjected to heat treatment. Although the stability of non-thermally treated emulsions remained above 96% on day 8 of the study, mold growth was observed in these samples on day 9. Consequently, stability assessment for these samples was discontinued. Such conditions are favorable for the proliferation of metabolically active vegetative cells [33]. In contrast, thermally treated emulsions exhibited greater stability throughout the storage period, maintaining approximately 92.75% stability by the end of the experiment (after 21 day of storage). In contrast to traditional emulsion gels, Pickering-type systems are stabilized through the irreversible adsorption of solid particles at the oil–water interface, where they decrease interfacial energy and create a rigid barrier that contributes to improved emulsion stability [34]. Pomace constituents, including insoluble and soluble dietary fiber, proteins, play a role in determining emulsion stability [35]. Furthermore, pectin present in black currant pomace between 2 and 15% [11,36,37] may contribute to thickening of these O/W dispersion systems due to interactions involving hydrophobic groups [38]. The stability of berry pomace-based emulsions is attributed to two mechanisms: (i) adsorption of fine insoluble particles at the O/W interface, where they form a protective layer around droplets, and (ii) increased viscosity of the continuous phase resulting from interactions between the insoluble fraction and soluble components, especially endogenous proteins, which reduces droplet mobility and improves stability [35].

Figure 1.

Effect of storage duration on static and thermal stability of structured emulsions.

3.2. Effect of Structured Emulsions Supplemented with Black Currant Pomace on Dough Texture of Shortbread Cookies

The obtained results describing the influence of EBP on the texture parameters of cookie dough are presented in Table 2. The results of dough texture analysis showed that the control cookie dough prepared with margarine exhibited significantly higher hardness (p < 0.05) than the EBP-containing samples. In contrast, the dough in which 70% of margarine was replaced with EBP demonstrated significantly lower hardness (p < 0.05), along with the highest values of consistency, adhesiveness, and cohesiveness compared to the other samples. These trends are consistent with observations reported in other studies on O/W emulsions [14]. In a study on apple pomace, the authors reported that the dietary fiber present in the pomace can compete with wheat gluten for water, thereby limiting the development of the gluten network. These fibers may also dilute or disrupt the formation of the wheat protein matrix, leading to a firmer and denser dough [14,39]. Consistent with these findings, Xie et al. [40] observed a decrease in hardness in a study where O/W emulsions were stabilized by cellulose. The reduction in dough hardness can be attributed to the hydration and swelling properties of dietary fibers, resulting in a softer and more workable biscuit dough [41]. In addition, the emulsion may interact with flour proteins to facilitate gluten network formation, further contributing to the development of an elastic and soft dough structure [42].

Table 2.

Texture characteristics of shortbread cookies dough containing EBP.

3.3. Effect of Structured Emulsions Supplemented with Black Currant Pomace on Color, Shape Properties of Shortbread Cookies

The visual appearance of cookies containing EBP are provided in Figure 2. These images clearly show that the color of the control cookies differed significantly from those containing the EBP. As the amount of EBP increased, the color of the cookies became progressively darker. The visually observed differences in cookie color were confirmed by instrumental color measurements, the results of which are presented in Table 3.

Figure 2.

Appearance of shortbread cookies after baking with EBP: SKK—control sample; SK50EBP—50% of margarine was replaced with EBP; SK70EBP—70% of margarine was replaced with EBP.

Table 3.

Effect of EBP on color parameters, shape and textural properties of shortbread cookie.

The color measurement results indicated that the EBP additive decreased the lightness (L*) and yellowness (b*) of the cookies while increasing the redness (a*) values. Sereti et al. [14] investigated the effect of an emulsion additive stabilized with apple pomace on color characteristics and found that the lightness of cookies enriched with apple pomace significantly decreased with increasing additive concentration. Meanwhile, the redness (a*) values increased, whereas the yellowness (b*) values decreased, indicating more intense browning in the cookies containing apple pomace. This effect can be attributed not only to the intrinsic color of the raw material—which differs from conventional confectionery flour—but also to the presence of glucose and fructose in the pomace, which participate in caramelization and Maillard reactions. These reactions are well known to promote browning in baked products through the formation of melanoidins and other reaction compounds. Alongi et al. [43] and Patel et al. [44] also reported that the use of apple pomace in the development of functional cookies reduced lightness values, resulting in darker final products. Temperature and water activity are considered the main factors influencing browning during cookie baking [45,46]. Increased dietary fiber such as cellulose content enhanced hydration via hydrogen bonding, thereby partially suppressing the Maillard reaction [41,47].

Baking trial results showed that the EBP additive had a significant effect on cookie shape—specifically, it reduced the diameter of the baked products (Table 3). Sereti et al. [14], in their study on the impact of apple pomace-stabilized emulsion additives on cookie quality, found that replacing margarine with an apple pomace-stabilized O/W emulsion primarily affected cookie diameter, with the control cookies exhibiting the largest values. Solid fat replacers (O/W emulsions) significantly reduced the diameter and spread ratio, but had little effect on cookie height. A lower concentration of solid fats combined with a higher water content increased the mobility of dough components, resulting in dough that was less compact and cohesive. As a result, the dough spread less during baking, thereby reducing the spread ratio. Spread ratio of cookies may have decreased as a result of reduced fluidity [48]. These findings are consistent with the results of Elgindy’s study [4], which showed that using dried apple pomace as a fat replacer reduced cookie diameter. Similarly, Erinc et al. [49] demonstrated that replacing fat with wheat bran fiber also influenced cookie shape by reducing the spread ratio.

3.4. Effect of Structured Emulsions Stabilized with Black Currant Pomace on Textural Properties of Shortbread Cookie

The effect of the EBP additive on shortbread textural properties is presented in Table 4. It was found that the EBP additive significantly increased (p < 0.05) the hardness of the shortbread cookies compared to the margarine-containing product. Studies by Sereti et al. [14] demonstrated that increasing the amount of apple pomace-stabilized emulsion (replacing 70%, 90%, and 100% of margarine) resulted in cookies that were harder and more resistant to deformation and breakage compared to the control. In contrast, formulations with lower amounts of the O/W emulsion, higher solid fat content, and greater concentrations of saturated fatty acids produced cookies with a softer and more brittle texture. Similar trends were reported by Yashini et al. [50] who used tomato seed flour as a fat replacer in cookie production. According to Goswami et al. [51] the use of carbohydrate-based hydrocolloids as fat replacers increases water absorption in the dough and strengthens the gluten network, leading to firmer cookies. The observed texture modifications in hydrocolloid-enriched cookies are associated with changes in moisture retention and differences in solid fat content, which influence the development and plasticization of the composite gluten–starch network. The lower fracture strength observed in margarine-rich shortbread cookies may be explained by the impact of fat on gluten network formation during mixing. These textural findings are consistent with the diameter and spreadability results, where the largest diameter and highest spread ratio were observed in the control cookies containing margarine, supporting the conclusion that reduced fat content and emulsion addition led to denser and structurally firmer cookies.

Table 4.

Effect of EBP on the texture parameters of shortbread cookies during storage.

The results of the study on the effect of the structured emulsion additive on changes in shortbread cookie texture parameters during storage are presented in Table 4. The hardness of both the control cookies and those with EBP significantly (p < 0.05) increased over the 7-week storage period. The additives of EBP intensified these hardness changes. Over the 7-week period, the hardness of the control cookies with margarine increased by 4.99 N (51.28%), while the cookies in which 50% and 70% of margarine was replaced by the emulsion showed an increase of 25.22 N (78.91%) and 68.45 N (79.65%), respectively. These results suggest that, to maintain a texture acceptable to consumers, the shelf life of cookies formulated with EBP should not exceed two months.

According to the scientific literature, cookies typically exhibit a long shelf life due to their low water activity. Nevertheless, texture changes may occur during storage as a result of moisture migration, redistribution, and interactions among ingredients. Components within the cookie matrix can exist in different physical states depending on water content and distribution, which in turn affects molecular mobility and physical behavior. Flour-based confectionery products are generally hygroscopic and can readily absorb or lose moisture depending on ambient humidity. The primary quality factor associated with staling in such products is the loss of crispness caused by moisture uptake from the surrounding environment [14].

3.5. Effect of Structured Emulsions Stabilized with Black Currant Pomace on Sensory Attributes of Shortbread Cookies

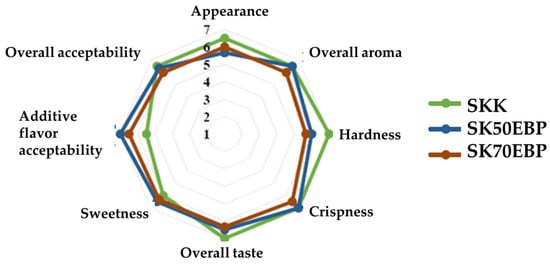

The sensory properties and overall acceptability of the shortbread cookies as affected by EBP addition are shown in Figure 3. The sensory evaluation results indicated that the most preferred samples were the control cookies with margarine and those in which 50% of the margarine was replaced with EBP. Panelists particularly appreciated the hardness, crispiness, and overall flavor of the cookies without EBP replacer (control sample), and the crispiness and overall aroma of the additive in the cookies which 50% of margarine was replaced with structured emulsion. The least acceptable were the cookies in which 70% of the margarine was replaced by the EBP. Previous research has also shown that cookies made with emulsions achieved favorable sensory ratings for texture and overall acceptability, although butter-based controls remained the most preferred [28,52].

Figure 3.

Sensory properties and overall acceptability of shortbread cookies: SKK—control sample; SK50EBP—50% of margarine was replaced with EBP; SK70EBP—70% of margarine was replaced with EBP.

3.6. The Nutritional Composition of Shortbread Cookies

The calculated nutritional composition of shortbread cookies is presented in Table 5. The results of the nutritional calculations showed that replacing margarine in the shortbread cookies with an EBP reduced the energy value, fat content, saturated fatty acids, and salt, while increasing the amounts of carbohydrates, sugars, dietary fiber, and proteins. Compared to the control cookies with margarine, the fat content in cookies where 50% of margarine was replaced with EBP was reduced by 6.02 g/100 g of product (26.72%), and the saturated fatty acid content by 4.16 g/100 g (45.02%). In the cookies with 70% margarine replacement, fat and saturated fatty acids decreased by 8.43 g/100 g (37.42%) and 5.83 g/100 g (63.06%), respectively. The margarine replacement by EBP increased content of dietary fiber and protein.

Table 5.

Nutritional composition of shortbread cookies in which 50% and 70% of margarine was replaced with EBP.

The calculations indicated that cookies in which more than 50% of margarine was replaced with EBP could be labeled with the nutrition claim “Reduced in saturated fat,” in accordance with Regulation (EC) No. 1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council on nutrition and health claims made on foods [53], since their saturated fatty acid content was reduced by more than 30% compared to the control cookies. This reduction is particularly relevant considering that excessive intake of saturated and trans fatty acids from solid fats such as margarine and butter has been associated with adverse health effects, including increased cardiovascular disease risk [1,2,54]. High consumption of saturated fats remains a major dietary concern in Europe, emphasizing the importance of reformulating bakery products to align with nutritional recommendations and reduce overall saturated fat intake [3]. Therefore, the substitution of margarine with blackcurrant pomace–stabilized emulsion represents a promising approach to developing clean-label bakery products with improved nutritional profiles and reduced health risks. Moreover, all ingredients used in the emulsion are food-grade and generally recognized as safe (GRAS), ensuring that this fat replacement strategy poses no concerns regarding consumer safety.

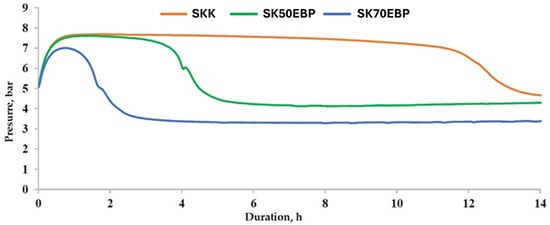

3.7. Effect of Emulsions Stabilized with Black Currant Pomace on the Oxidative Stability of the Fats in the Shortbread Cookies

The reduction in saturated fatty acids due to partial replacement of margarine with a EBP also influenced the oxidative stability of the fats in the shortbread cookies. The effect of the structured emulsion additive on the induction period (IP) of cookie fats is presented in Figure 4. The results of the Oxipres test showed that the control cookies with margarine had the highest IP. A higher IP value indicates greater oxidative stability, meaning these cookies are more resistant to oxidation and have a longer shelf life. This could be attributed to the use of baking margarine in the control samples, which has higher oxidative stability compared to liquid oils [55]. As the proportion of rapeseed oil increased and margarine content decreased in the formulations, the IP and oxidative stability of the cookie fats declined.

Figure 4.

Effect of EBP on the induction period (IP) of shortbread cookie fats: SKK—control sample (IP = 11.93 ± 0.02); SK50EBP—50% of margarine was replaced with EBP (IP = 4.14 ± 0.08); SK70EBP—70% of margarine was replaced with EBP (IP = 1.34 ± 0.01).

3.8. Effect of Structured Emulsions Stabilized with Black Currant Pomace on the Content of Total Phenolic Compounds in Shortbread Cookies

EBP addition significantly affected the total phenolic content (TPC) of the cookies (Table 6). Compared to the control samples, the TPC in cookies with 50% and 70% margarine replaced by EBP increased by 38% and 43%, respectively. According to findings from studies using apple pomace in baked products, the high phenolic content in cookies may be attributed not only to the naturally high concentration of phenolic compounds in the fruit pomace, but also to the formation of new compounds during baking—namely, Maillard reaction products—which can enhance the cookies’ radical-scavenging and antioxidant activity [14]. The TPC in black currant pomace determined in this study was higher than values reported in other studies. For instance, Blejan et al. [56] and Basegmez et al. [57] reported 26.2 and 24.34 mg GAE/g d.m., respectively, while seedless black currant pomace was found to contain 18.55–22.41 mg GAE/g [58]. The characteristics of the pomace, including its total phenolic content, can vary depending on the berry cultivar, growing conditions such as climate and soil, and the processing techniques used [15].

Table 6.

Effect of EBP on the TPC in shortbread cookies.

4. Conclusions

Thermal treatment at 80 °C significantly affected the stability of the oil-in-water (O/W) structured emulsion stabilized with blackcurrant pomace during storage, with greater thermal than static stability observed. The addition of the structured emulsion reduced dough hardness, strengthened consistency, and increased cohesiveness and binding capacity. In cookies, the emulsion influenced shape, color, and texture—reducing diameter and lightness (L*) while increasing hardness. These effects became more pronounced at higher emulsion inclusion levels.

In sensory evaluation, panelists preferred the control cookies with margarine and those with 50% margarine replacement. The addition of the structured emulsion reduced total fat by 27–37% and saturated fatty acids by 45–63%, while increasing total phenolic compounds by 38–43% compared to the control. According to Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006, such cookies may be labeled “Reduced in saturated fat.”

During storage at room temperature, all cookies exhibited staling and increased hardness, which was accelerated by the structured emulsion. After 7 weeks, hardness increased by over 50% in control cookies and by about 80% in those with 50% and 70% margarine replacement. To ensure acceptable texture, the shelf life of cookies with emulsion addition should therefore be limited. Overall, the use of blackcurrant pomace-stabilized structured emulsion offers a clean-label and nutritionally improved alternative for partial fat replacement in shortbread cookies.

Overall, this study demonstrates that incorporating blackcurrant pomace-stabilized structured emulsion as a partial fat replacer offers a promising clean-label approach that improves the nutritional profile and aligns with sustainable food production goals, while maintaining acceptable technological and sensory quality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.B. and D.Č.; methodology, J.J. and D.Č.; software, J.J. and R.M.; validation, J.J. and R.M.; formal analysis, J.J., R.M., D.Č. and L.B.; investigation, R.M.; resources, L.B.; data curation, L.B. and D.Č.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M., J.J. and D.Č.; writing—review and editing, L.B., D.Č. and J.J.; visualization, J.J. and D.Č.; supervision, L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EBP | Emulsion supplemented with black currant pomace |

| O/W | Oil-in-water emulsion |

| TPC | Total phenolic content |

References

- Effects of Saturated Fatty Acids on Serum Lipids and Lipoproteins: A Systematic Review and Regression Analysis; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/246104 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Nagpal, T.; Sahu, J.K.; Khare, S.K.; Bashir, K.; Jan, K. Trans Fatty Acids in Food: A Review on Dietary Intake, Health Impact, Regulations and Alternatives. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 5159–5174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Castenmiller, J.; de Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Knutsen, H.K.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Naska, A.; et al. Scientific Advice Related to Nutrient Profiling for the Development of Harmonised Mandatory Front-of-pack Nutrition Labelling and the Setting of Nutrient Profiles for Restricting Nutrition and Health Claims on Foods. EFSA J. 2022, 20, e07259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgindy, A. Utilization of Food by Products in Preparing Low-Calorie Biscuits. J. Food Dairy Sci. 2020, 11, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhu, L.; Wu, G.; Jin, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H. Relationship between the Microstructure and Physical Properties of Emulsifier Based Oleogels and Cookies Quality. Food Chem. 2022, 377, 131966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giarnetti, M.; Paradiso, V.M.; Caponio, F.; Summo, C.; Pasqualone, A. Fat Replacement in Shortbread Cookies Using an Emulsion Filled Gel Based on Inulin and Extra Virgin Olive Oil. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 63, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidovich-Pinhas, M.; Barbut, S.; Marangoni, A.G. Development, Characterization, and Utilization of Food-Grade Polymer Oleogels. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 7, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huc-Mathis, D.; Guilbaud, A.; Fayolle, N.; Bosc, V.; Blumenthal, D. Valorizing Apple By-Products as Emulsion Stabilizers: Experimental Design for Modeling the Structure-Texture Relationships. J. Food Eng. 2020, 287, 110115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Liu, J.; Addy, M.; Ding, B.; Cheng, Y.; Peng, P.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, P.; Ruan, R. Physicochemical and Emulsifying Properties of Orange Fibers Stabilized Oil-in-Water Emulsions. LWT 2020, 133, 110054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Sánchez, E.; Quiles, A.; Hernando, I. Use of Berry Pomace to Design Functional Foods. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 3204–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, K.; MacNaughtan, W.; Laws, A.P.; Foster, T.J.; Campbell, G.M.; Kontogiorgos, V. Fractionation and Characterisation of Dietary Fibre from Blackcurrant Pomace. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 81, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, Q.; Dong, H.; Dai, T.; Li, Z.; Liu, C.; Wang, R. The Effects of Pectin Structure on Emulsifying, Rheological, and In Vitro Digestion Properties of Emulsion. Foods 2022, 11, 3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Wani, K.M.; Mujahid, S.M.; Jayan, L.S.; Rajan, S.S. Review on Pectin: Sources, Properties, Health Benefits and Its Applications in Food Industry. J. Future Foods 2026, 6, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereti, V.; Kotsiou, K.; Ciurlă, L.; Patras, A.; Irakli, M.; Lazaridou, A. Valorizing Apple Pomace as Stabilizer of Olive Oil-Water Emulsion Used for Reduction of Saturated Fat in Biscuits. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 151, 109746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, R.E.; Gonzalez de Mejia, E. Blackcurrants (Ribes nigrum): A Review on Chemistry, Processing, and Health Benefits. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 2387–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, P.H.; Hellström, J.; Karhu, S.; Pihlava, J.M.; Veteläinen, M. High Variability in Flavonoid Contents and Composition between Different North-European Currant (Ribes spp.) Varieties. Food Chem. 2016, 204, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, A.; Waliat, S.; Afzaal, M.; Saeed, F.; Ahmad, A.; Din, A.; Ateeq, H.; Asghar, A.; Shah, Y.A.; Rafi, A.; et al. Biological Activities, Therapeutic Potential, and Pharmacological Aspects of Blackcurrants (Ribes nigrum L.): A Comprehensive Review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 5799–5817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohm, H.; Brennan, C.; Turner, C.; Günther, E.; Campbell, G.; Hernando, I.; Struck, S.; Kontogiorgos, V. Adding Value to Fruit Processing Waste: Innovative Ways to Incorporate Fibers from Berry Pomace in Baked and Extruded Cereal-Based Foods—A SUSFOOD Project. Foods 2015, 4, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, M.; Costa, E.; Silva, S.; Cruz Sousa, S.; Maria Gomes, A.; Pus, A.; Elena Tanislav, A.; Mures, E.; Mures, V. Emulgels as Fat-Replacing Systems in Biscuits Developed with Ternary Mixtures of Pea and Soy Protein Isolates and Gums. Gels 2025, 11, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Choi, H.W.; Choe, Y.; Hahn, J.; Choi, Y.J. Development of Emulsion Gels as Animal Fat Analogs: The Impact of Soybean and Coconut Oil Concentration on Rheological and Microstructural Properties. Food Chem. X 2025, 27, 102439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klojdová, I.; Stathopoulos, C. The Potential Application of Pickering Multiple Emulsions in Food. Foods 2022, 11, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kairė, A.; Jagelavičiūtė, J.; Bašinskienė, L.; Syrpas, M.; Čižeikienė, D. Influence of Enzymatic Hydrolysis on Composition and Technological Properties of Black Currant (Ribes nigrum) Pomace. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Faruq, A.; Farahnaky, A.; Torley, P.J.; Buckow, R.; Eri, R.; Majzoobi, M. Sustainable Approaches to Boost Soluble Dietary Fibre in Foods: A Path to Healthier Foods. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 162, 110880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.M. CODEX-Aligned Dietary Fiber Definitions Help to Bridge the ‘Fiber Gap’. Nutr. J. 2014, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Martí, J.; Sanz, T.; Hernando, I.; Quiles, A. Emulsion Gels Structured with Clementine Pomace: A Clean-Label Strategy for Fat Reduction. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 167, 111471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meral, R.; EkiN, M.M.; Ceylan, Z.; Alav, A.; Kına, E. A Novel Solution to Enhance the Oxidative and Physical Properties of Cookies Using Maltodextrin-Based Nano-Sized Oils as a Fat Substitute. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 23111–23120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, A.; Anis, A.; Alam, M.A.; Al-Zahrani, S.M.; Jarzebski, M.; Pal, K. Effect of Soy Wax/Rice Bran Oil Oleogel Replacement on the Properties of Whole Wheat Cookie Dough and Cookies. Foods 2023, 12, 3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Luna, K.; Astiasaran, I.; Ansorena, D. Fat Reduced Cookies Using an Olive Oil-Alginate Gelled Emulsion: Sensory Properties, Storage Stability and in Vitro Digestion. Food Res. Int. 2023, 167, 112714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6658; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—General Guidance. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Regulation-1169/2011-EN-Food Information to Consumers Regulation-EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2011/1169/oj/eng (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Sabolová, M.; Johanidesová, A.; Hasalíková, E.; Fišnar, J.; Doležal, M.; Réblová, Z. Relationship between the Composition of Fats and Oils and Their Oxidative Stability at Different Temperatures, Determined Using the Oxipres Apparatus. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2017, 119, 1600454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. [14] Analysis of Total Phenols and Other Oxidation Substrates and Antioxidants by Means of Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahalagedara, A.S.N.W.; Gkogka, E.; Hammershøj, M. A Review on Spore-Forming Bacteria and Moulds Implicated in the Quality and Safety of Thermally Processed Acid Foods: Focusing on Their Heat Resistance. Food Control 2024, 166, 110716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.; Han, F.; Lv, X.; Zhang, S.; Ma, H.; Liu, B. Formation Mechanism of Pickering Emulsion Gels Stabilized by Proanthocyanidin Particles: Experimental and Molecular Dynamics Studies. Food Chem. 2023, 418, 135904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huc-Mathis, D.; Almeida, G.; Michon, C. Pickering Emulsions Based on Food Byproducts: A Comprehensive Study of Soluble and Insoluble Contents. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 581, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćorović, M.; Petrov Ivanković, A.; Milivojević, A.; Veljković, M.; Simović, M.; López-Revenga, P.; Montilla, A.; Moreno, F.J.; Bezbradica, D. Valorisation of Blackcurrant Pomace by Extraction of Pectin-Rich Fractions: Structural Characterization and Evaluation as Multifunctional Cosmetic Ingredient. Polymers 2024, 16, 2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inthalaeng, N.; Dugmore, T.I.J.; Matharu, A.S. Production of Hydrogels from Microwave-Assisted Hydrothermal Fractionation of Blackcurrant Pomace. Gels 2023, 9, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Deng, L.; Dai, T.; Chen, J.; Liu, W.; Liu, C.; Chen, M.; Liang, R. Emulsifying and Emulsion Stabilization Mechanism of Pectin from Nicandra physaloides (Linn.) Gaertn Seeds: Comparison with Apple and Citrus Pectin. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 130, 107674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, Y.; Ma, C.; Wang, B.; Bian, X.; Zhang, G.; Liu, X.; Song, Z.; Zhang, N. High Freeze-Thaw Stability of Pickering Emulsion Stabilized by SPI-Maltose Particles and Its Effect on Frozen Dough. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 276, 133778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Lei, Y.; Rong, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Liang, H.; Li, Y.; Li, B.; Fang, Z.; et al. Physico-Chemical Properties of Reduced-Fat Biscuits Prepared Using O/W Cellulose-Based Pickering Emulsion. LWT 2021, 148, 111745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolek, S. Olive Stone Powder: A Potential Source of Fiber and Antioxidant and Its Effect on the Rheological Characteristics of Biscuit Dough and Quality. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 64, 102423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, A.; Bettaccini, L.; Cini, E. The Kneading Process: A Systematic Review of the Effects on Dough Rheology and Resulting Bread Characteristics, Including Improvement Strategies. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 104, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alongi, M.; Melchior, S.; Anese, M. Reducing the Glycemic Index of Short Dough Biscuits by Using Apple Pomace as a Functional Ingredient. LWT 2019, 100, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Naik, S.N.; Satya, S.; Ghodki, B.M.; Jana, S.; Sharma, P. Utilization of Industrial Waste of Amla and Apple Pomace for Development of Functional Biscuits: Physical, Microstructural, and Macroscopic Properties. J. Food Process Preserv. 2022, 46, e16835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arepally, D.; Reddy, R.S.; Goswami, T.K.; Datta, A.K. Biscuit Baking: A Review. LWT 2020, 131, 109726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Van Der Fels-Klerx, H.J.; Peters, R.J.B.; Van Boekel, M.A.J.S. Acrylamide and 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural Formation during Baking of Biscuits: Part I: Effects of Sugar Type. Food Chem. 2016, 192, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohajdová, Z.; Karovičová, J.; Kuchtová, V.; Lauková, M. Utilisation of Beetroot Powder for Bakery Applications. Chem. Pap. 2018, 72, 1507–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Guo, L.; Zheng, S.; Du, C. Effect of Black Soybean Flour Particle Size on the Nutritional, Texture and Physicochemical Characteristics of Cookies. LWT 2022, 164, 113649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erinc, H.; Mert, B.; Tekin, A. Different Sized Wheat Bran Fibers as Fat Mimetic in Biscuits: Its Effects on Dough Rheology and Biscuit Quality. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 3960–3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashini, M.; Sahana, S.; Hemanth, S.D.; Sunil, C.K. Partially Defatted Tomato Seed Flour as a Fat Replacer: Effect on Physicochemical and Sensory Characteristics of Millet-Based Cookies. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 4530–4541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, M.; Sharma, B.D.; Mendiratta, S.K.; Pathak, V. Quality Evaluation of Functional Carabeef Cookies Incorporated with Guar Gum (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba) as Fat Replacer. Nutr. Food Sci. 2019, 49, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curti, E.; Federici, E.; Diantom, A.; Carini, E.; Pizzigalli, E.; Wu Symon, V.; Pellegrini, N.; Vittadini, E. Structured Emulsions as Butter Substitutes: Effects on Physicochemical and Sensory Attributes of Shortbread Cookies. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 3836–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EUR-Lex-02006R1924-20141213-EN-EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02006R1924-20141213 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Micha, R.; Mozaffarian, D. Trans Fatty Acids: Effects on Metabolic Syndrome, Heart Disease and Diabetes. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2009, 5, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, J.J.; Fagoaga, C.; Mura, J.; Sempere-Ferre, F.; Castellano, G. Effectiveness of Natural Antioxidants on Oxidative Stability of Margarines. LWT 2024, 214, 116997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blejan, A.M.; Nour, V.; Păcularu-Burada, B.; Popescu, S.M. Wild Bilberry, Blackcurrant, and Blackberry by-Products as a Source of Nutritional and Bioactive Compounds. Int. J. Food Prop. 2023, 26, 1579–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basegmez, H.I.O.; Povilaitis, D.; Kitrytė, V.; Kraujalienė, V.; Šulniūtė, V.; Alasalvar, C.; Venskutonis, P.R. Biorefining of Blackcurrant Pomace into High Value Functional Ingredients Using Supercritical CO2, Pressurized Liquid and Enzyme Assisted Extractions. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2017, 124, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sójka, M.; Król, B. Composition of Industrial Seedless Black Currant Pomace. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2009, 228, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).