Abstract

Although the elitist genetic algorithm (EGA) is an approach for the optimal design of pixelated metasurfaces, it is necessary to convert a two-dimensional (2D) metasurface to a one-dimensional array. This ignores the effects of the mutation on neighboring data in 2D metasurfaces, and hinders the rapid convergence of the algorithms. Therefore, we propose the 2D mutation-based EGA (2DM-EGA) to optimally design the linear-to-circular (LTC) polarization conversion metasurface (PCM). Compared with EGA, 2DM-EGA can significantly improve the convergence rate. Furthermore, combined with the proposed intuitive reward-based fitness function and circular polarization discrimination pertaining to an ellipticity angle β, 2DM-EGA, programmed in Python (2023 version), is used to accomplish optimal targets. Finally, the simulated operating band of the optimized metasurface varies from 8.16 GHz to 11.5 GHz with a reduced ellipticity angle β/π ≥ 0.15 and a relative bandwidth of 33.5%, which suggests that the optimized metasurface realizes the broadband LTC polarization conversion. The measured results are in excellent accord with the simulations validating 2DM-EGA for the optimal design of transmission-type wideband LTC PCMs. Additionally, the physical mechanism of the design is expounded.

1. Introduction

Because of its significant advantages, such as immunity to Faraday effect, anti-multipath fading, strong signal stability, and ionosphere penetration [1], the circularly polarized wave is widely used in satellite communication, mobile communication, remote sensing, and so on [2,3]. Then, the linear-to-circular (LTC) polarization converter draws considerable attention, which is traditionally realized by natural anisotropic materials or liquid crystals [4,5]. This causes the device to suffer from bulky size and high loss. Recently, the metasurface characterized by compact profiles, ease of fabrication, and low loss provides an alternative to tailor LTC polarization conversions [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Furthermore, compared with reflected metasurfaces, transmissive metasurfaces avoid information self-interference and feeder radiation occlusion, which attracts extensive focus [12,13,14]. However, up to now, the retrieved transmissive LTC polarization conversion metasurfaces (PCMs) are designed by conventional manual means, inevitably relying on professional design experience and consuming significant human resources, which hinders their wide application in various fields.

On the other hand, in the last few years, computer software-based optimization algorithms involving particle swarm optimization [15,16,17], simulated annealing [18,19,20], and genetic algorithm (GA) [21,22,23] have been used to facilitate the electromagnetic designs. By contrast, the traditional GA and elitist genetic algorithm (EGA) are applicable to more complex combinatorial optimization problems and have been proved to be an approach for the optimal design of metasurfaces [24,25]. Nevertheless, it is necessary to convert the two-dimensional (2D) metasurface to a one-dimensional (1D) array in these two optimization algorithms. This means that the mutation operation of GA or EGA only pertains to individual data in a 1D array and ignores the effects of the mutation on neighboring data in 2D metasurfaces, which is unfavorable for the rapid convergence of the algorithms.

Based on what is mentioned earlier, we propose the 2D mutation-based EGA (2DM-EGA). In this algorithm, the circular polarization discrimination is related to an ellipticity angle β [25], which can be used to optimally design the transmissive LTC PCM. We introduce a reward-based fitness function (RFF) to intuitively assess the operating bandwidth and transmission efficiency η. Compared with EGA, 2DM-EGA has a much faster convergence rate. Moreover, Python programs supplemented by CST simulation software (2020 version) and pixelated metasurfaces are used to accomplish optimal targets. Finally, the operating band of the optimized metasurface varies from 8.16 GHz to 11.5 GHz with reduced ellipticity angle β/π ≥ 0.15 and η ≥ 0.6, which is in excellent accord with the measurements. It validates the 2DM-EGA for the optimal design of transmissive LTC PCMs. Additionally, the mechanism of the design is expounded. In brief, this contribution not only proposes 2DM-EGA and RFF, but also progresses the design of LTC PCMs from manual towards automatic means.

2. Proposed 2DM-EGA and RFF

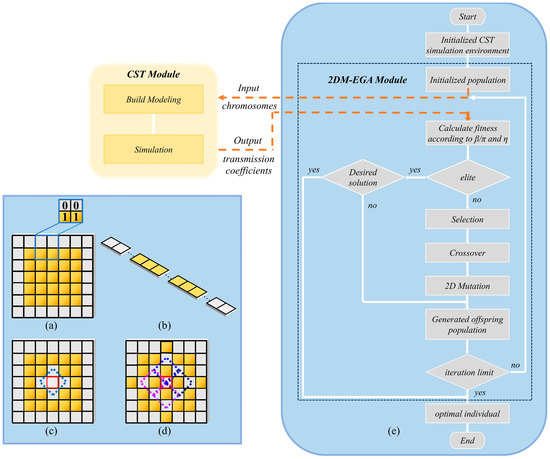

In general, as shown in Figure 1a, a 2D pixelated metasurface cell is divided into n × n square pixels indicated by 0s and 1s, in which 0 is the encoding of the dielectric pixel (light gray) and 1 is the encoding of the metal film pixel (yellow). On the basis of the pixelated cell, 2DM-EGA and RFF are proposed to optimally design the transmissive LTC PCM.

Figure 1.

Schemata of (a) 2D pixelated metasurface cell, (b) 1D array, (c) 2D mutation-I, (d) 2D mutation-II. (e) Flowchart of Python-controlled 2DM-EGA.2.2. RFF with a reward fitness value.

2.1. 2DM-EGA

For EGA, a 2D pixelated metasurface is first converted to a 1D array comprising 0 s or 1 s, shown in Figure 1b, and then selection, crossover, and mutation are performed. In particular, the mutation of EGA is realized by randomly changing pixel codes in the 1D array to mimic genetic mutation in biology. Obviously, although the mutation of EGA follows a random mode, it does not take into account the influence of mutated pixels on neighboring pixels in 2D space. Hence, we present 2DM-EGA involving the impact of mutated pixels on neighboring pixels, whose mutation is implemented in the 2D pixelated metasurface. The difference between 2DM-EGA and EGA is that 2DM-EGA in this work employs the 2D mutation mechanism.

As illustrated in Figure 1c,d, the 2D mutation includes two categories, in which the pixel bounded by the red quadrangle is located at the mutation center. In detail, in Figure 1c, when the center pixel is randomly selected and mutated, four neighboring pixels are influenced by it and then mutated. Obviously, the five mutated pixels enclosed by the blue dashed line form a small diamond shape, which is described in terms of 2D mutation-I. Moreover, in Figure 1d, after the center pixel is randomly selected, four diamonds bounded by the blue, pink, black, and purple dashed lines combine into a big diamond and the relevant nine vertices are all mutated, which is referred to as 2D mutation-II. The flowchart of the 2DM-EGA optimal design is shown in Figure 1e, which is described in Reference 25.

2.2. RFF with a Reward Fitness Value

When we apply proposed 2DM-EGA to optimally design transmissive LTC PCMs, the fitness value derived from fitness function is necessary to select elites and better individuals and assess the performances of optimized LTC PCMs. Considering the circular polarization of the transmitted wave determined by β within the optimized bandwidth, and the transmission efficiency being a key factor of transmissive PCMs, RFF hence is written as Equation (1).

In Equation (1), a and b are, respectively, the leftmost and the rightmost sampling points in the frequency range from fa to fb, i.e., the frequency range of the metasurface to be designed; N is the number of sampling points between the maximum frequency fN and minimum frequency f1, and both are configured at the beginning of the optimal program and cover the band range from fa to fb; ηc is the configured transmission efficiency; R, 2R, and 3R are reward fitness values with R = |β/π|max Nηmax; the reduced ellipticity angle is

where, for an x-polarized incident wave traveling in the −z direction, txx and tyx are amplitudes of co-polarization and cross-polarization transmission coefficients, respectively; φxx and φyx are the corresponding phases, and phase difference ∆φ = φxx − φyx; β/π ∈ [−0.25, 0.25]. Moreover, it can be deduced from the axial ratio (i.e., AR = −10lg|tanβ| less than 3dB that β/π ≥ 0.15 or β/π ≤ −0.15; β/π ≥ 0.15 suggests that the transmitted beam is a right-hand circularly polarized wave, and β/π ≤ −0.15 a left-hand circularly polarized wave. The transmission efficiency is

in which rxx and ryx are amplitudes of co-polarization and cross-polarization reflection coefficients. Clearly, |β/π|max = 0.25 and ηmax = 1 can further derive R = 0.25N.

Before we proceed any further, for clarity, we will state in detail the fitness function in Equation (1), which involves five cases as follows:

- 1.

- The first formula means that the obtained metasurface has no LTC polarization conversion performance in the entire band; the metasurface should further be phased out in the next generation, and its fitness is therefore set to 0.

- 2.

- If the frequency range of some sampling points is greater than or equal to f1 and less than fa, and also greater than fb and less than or equal to fN, and |β| ≥ 0.15π is met, then the fitness value is computed by using the second formula; this case indicates that although the optimized metasurface may operate out of the designed band, it still has the potential to realize the target; the fitness value is therefore set to greater than 0, but it does not consider a reward.

- 3.

- If not all sampling points but some points in the frequency range varying from fa to fb satisfy |β| ≥ 0.15π, the fitness value is computed by using the third formula; compared with previous cases, this case is more likely to achieve the optimal target, and the minimum reward fitness value R is then set.

- 4.

- The fourth formula implies that the optimized metasurface operating bandwidth is fb − fa with a transmission efficiency less than ηc; therefore, the second-largest reward fitness value 2R is fixed.

- 5.

- If b − a + 1 sampling points in the frequency range varying from fa to fb satisfy |β| ≥ 0.15π and η ≥ ηc, the fitness value is computed by using the fifth formula; in this case, the operating bandwidth and high transmission efficiency are evaluated comprehensively for the target performance; hence, the maximum reward fitness value 3R is given.

It is evident from Equation (1) that the closer the transmitted wave polarization is to an ideal circular polarization (i.e., β = 0.25π), or the larger the transmission efficiency, the larger the fitness value is.

3. Optimal Results and Analysis

Given that n = 16, N = 1000 (i.e., R = 250), f1 = 8 GHz, fN = 12 GHz, fa = 8.5 GHz, fb = 11.5 GHz, and ηc = 60%, therefore a = 126, and b = 874; the initial population includes 20 pixelated metasurface cells. In addition, it is worth noting that the design uses wire grid on the back side to broaden the operating band [26].

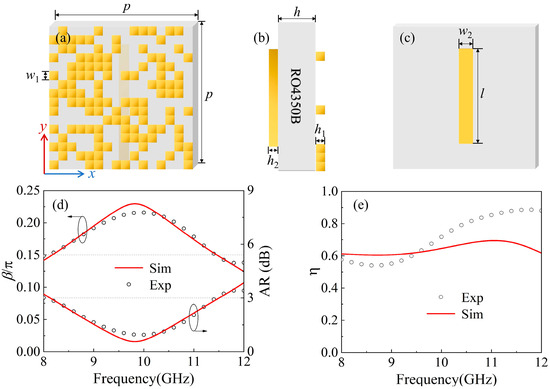

Here, we exploit Python-programmed 2DM-EGA supplemented by CST simulation software to optimally design transmissive LTC PCMs; in CST simulation, both x and y directions are truncated by periodic boundary conditions, z direction is set to the Floquet port, and meshing uses adaptive grids; the number of iterations of the Python program is 50, and the probabilities of both the 2D mutation-I and 2D mutation-II are 0.5. Then, the optimized transmissive LTC PCM cell is illustrated in Figure 2a, whose side and back views are shown in Figure 2b,c. The metals of the top and back layers are gold with a conductivity of 4.561e + 007 S/m; the relative permittivity of the middle dielectric RO4350B is 3.55; the gold wire grid on the back is located at the center of the cell. The optimized cell dimensions are shown in Table 1.

Figure 2.

The metasurface cell optimized by IEGA and its performances. (a) Top view; (b) Side view; (c) Back view; (d) Reduced ellipticity angle and AR; (e) Transmission efficiency.

Table 1.

Dimensions of optimal metasurface cell (unit: mm).

It should be pointed out that the incident beam is x-polarized, and that by traveling in the −z direction it impinges normally on the top layer. The simulated performances of the optimal transmissive LTC PCM tagged with Sim are illustrated in Figure 2d,e. It can be seen from the red line that in the frequency range of 8.16 GHz to 11.5 GHz, β/π ≥ 0.15, the relative bandwidth is 33.5%, and η is greater than 0.6, which suggests that the optimized metasurface effectively achieves the LTC polarization conversion in the frequency range covering the designed operating band, which is also verified by the simulated AR ≤ 3 dB.

To better illustrate the advantages of this work, Table 2 presents a comparison between our proposed transmissive LTC PCM and several previously reported transmissive ones. Here, CF is the center working frequency, RB is the relative bandwidth, and NL is the number of substrate layers. As is evident from Table 2, the designed LTC PCM integrates multiple key advantages. Specifically, it exhibits a broadband operating response, adopts a low-profile structural design with a small overall size, and allows for simple and scalable fabrication processes.

Table 2.

Performance comparison of transmissive LTC PCMs.

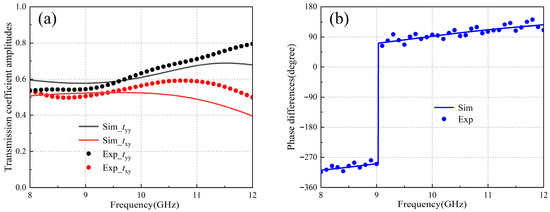

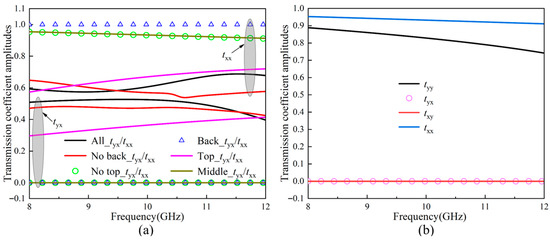

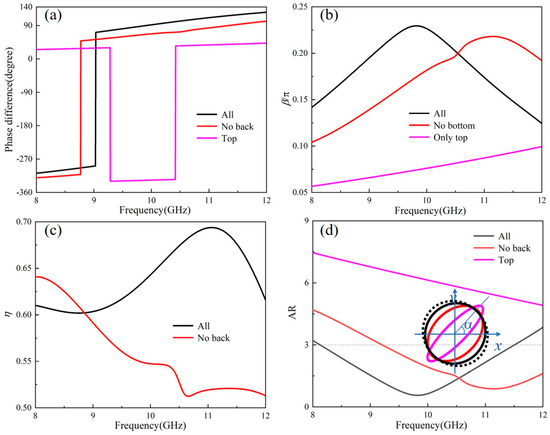

In addition, to further illustrate the inapplicability of the traditional amplitude–phase discrimination method in optimization design, the simulated amplitudes and phase differences of transmission coefficients are plotted in Figure 3. Evidently, as shown in the solid lines, tyx ≈ txx and ∆φ is approximately −270° or 90° varying from 8.16 GHz to 11.5 GHz, which suggests that the transmitted beam is right-handed circularly polarized. However, one cannot neglect that the phase difference is discontinuous in the operating band, which visually explains its inapplicability to programmable optimization designs. In contrast, β is continuous and then used to discriminate the circular polarization, which is emphasized again here. Parenthetically, although the axial ratio is also continuous, it may be the potential infinite value and not applicable for the optimal design of LTC PCMs.

Figure 3.

Transmission coefficients. (a) Amplitudes; (b) Phase differences.

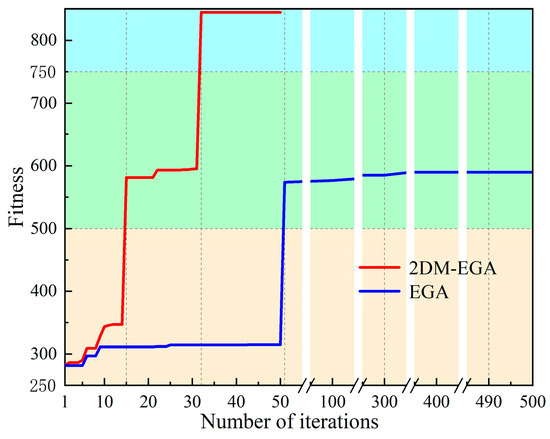

Next, consider the fitness of the designed metasurface and the 2DM-EGA convergence, which is shown in Figure 4. Firstly, for 2DM-EGA, when the number of iterations changes from 1 to 14, from 15 to 31, and from 32 to 50, the optimal individual fitness satisfies the third, fourth, and fifth formulas of Equation (1), respectively. Clearly, the fitness derived from RFF can be used to intuitively determine whether the metasurface performance meets the target. Secondly, when the fitness value is greater than 817 derived from the fifth formula, the obtained metasurface can realize the target performance. Obviously, for 2DM-EGA, after 32 iterations, the fitness value reaches 844.5, meeting the fitness requirements. However, for EGA, the fitness value has always been calculated by using the third and fourth formulas, which signifies that the EGA-based optimal design is still a failure even at the 500th iteration. In other words, the corresponding metasurface can work in the designed band but with a low transmission efficiency, i.e., the optimization algorithm falls into a local optimum. Briefly, compared to EGA experiencing a slower convergence, 2DM-EGA exhibits a much faster convergence, which validates the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm and RFF.

Figure 4.

Optimal individual fitness relating to the number of iterations.

4. Mechanism Analysis

Firstly, consider six cases stated in Table 3. Case I, consisting of the top, middle, and back layers of the optimized cell, is tagged with All in the figures; Case II, tagged with No back, includes the top and middle layers; Case III, tagged with No top, includes the middle and back layers; Cases IV, V, and VI are tagged with Back, Top, and Middle and include the back layer, top layer, and middle layer, respectively. The simulated transmission coefficient amplitudes in the six cases are shown in Figure 5.

Table 3.

Six cases and corresponding compositions and identifications.

Figure 5.

The simulated results. (a) Transmission coefficient amplitudes relating to x-polarized incident waves in six cases. (b) Transmission coefficient amplitudes relating to x/y-polarized incident waves in Case III.

It asserts from Figure 5a,b that for Case III, the cross-polarization component amplitudes are zero, and the co-polarization component amplitudes are approximately one, which state that the transmitted beams passing through this case have no cross-polarization components; likewise, no cross-polarization wave is transmitted for the cases of IV and VI; for Case V, tyx significantly approaches to txx. Consequently, we can draw a conclusion from Figure 5a,b that the cross-polarization transmission coefficient is attributed to the anisotropy of the top layer. In other words, the top layer plays the key role to realize the LTC polarization conversion.

For Case II, the electromagnetic wave is incident on three layers of media, i.e., gold, RO4350B, and vacuum, with different constitutive parameters, which results in multiple reflections. Specifically speaking, within RO4350B, parts of waves bounce back and forth between the two bounding surfaces, with some penetrating into the top layer and the vacuum; the top layer then reflects the waves from the interface between the top and middle layers as the incident wave impinging on it, and the following wave is transmitted into the vacuum, and so on. The total transmitted wave in the vacuum is, in fact, the resultant of the initial transmitted component and the transmitted wave contributed by an infinite sequence of multiple reflections. Hence, in comparison with Case V, the transmitted co-polarization and cross-polarization components are changed. Concretely, as shown by the red lines in Figure 5a and Figure 6a, tyx is much closer to txx; the phase difference ∆φ between transmitted cross- and co-polarization phases gets closer to −270° or 90°. Moreover, as illustrated in Figure 6b, in this case, the reduced ellipticity angle (red line) is greater than or equal to 0.15 from 9.26 GHz to 12 GHz, which demonstrates that the relative bandwidth of the case is 25.8%. However, the transmission efficiency (red line) shown in Figure 6c is less than 0.6. To this end, Case I, consisting of the back layer, is further explored.

Figure 6.

The performance comparisons. (a) Phase differences. (b) Reduced ellipticity angle. (c) Transmission efficiency. (d) Axial ratio and circular/elliptical polarizations of the transmitted waves at 10 GHz (the dotted line describes an ideal circularly polarized wave; α ≈ 45° is the tilt angle).

As depicted by the black lines in Figure 5a and Figure 6a, the transmission coefficients of Case I are varied in contrast to those of Case II, which broaden the operating bandwidth in the designed target frequency range and improve the transmission efficiency shown in Figure 6b,c. Furthermore, the transmitted axial ratios and the circular/elliptical polarizations of Case I, Case II, and Case V at 10 GHz are sketched in Figure 6d. By comparison, the transmitted wave of Case I operates within the design frequency range and basically coincides with the ideal circularly polarized one (dotted line) at 10 GHz, which suggests that the design achieves the efficient LTC polarization conversion.

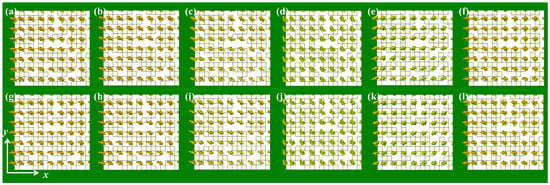

From another point of view, at 10 GHz, the electric field distributions of the optimized LTC PCM at various time phases (ωt) are demonstrated in Figure 7, which indicates that Et rotates at a uniform rate with an angular velocity ω in a clockwise direction. When the fingers of the right hand follow the direction of the rotation of Et, the thumb points to the direction of propagation of the transmitted wave, i.e., −z direction. Thus, the transmitted wave is a right-hand circularly polarized wave. Likewise, the design converts a linearly polarized wave into a right-hand circularly polarized wave in the frequency range from 8.16 GHz to 11.5 GHz.

Figure 7.

(a–l) Electric field distributions with time phases varying from 0° to 330° (30° step) at 10 GHz, where the arrows indicate the direction of the electric field.

5. Experimental Results

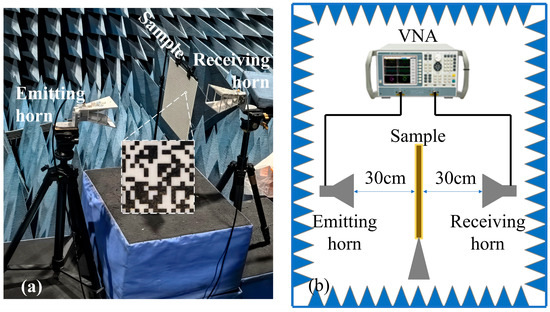

To verify the proposed algorithm and the LTC polarization conversion performance of the optimized metasurface, a sample with a size of 240 mm × 240 mm, composed of 30 × 30 cells, is fabricated, as shown in Figure 8a. The measurement setup in the anechoic chamber is presented in Figure 8a,b, which involves the emitting and receiving horns connected by the vector network analyzer to measure the co-polarization and cross-polarization transmission coefficients. In the measurement, the sample is illuminated by the emitting horn, and the transmitted waves are received by the receiving horn. The two horns are 30 cm away from the metasurface sample to be measured. The horn can transmit or receive x- or y-polarized waves by rotating the horn by 90°.

Figure 8.

Measurement setup. (a) Measured scenarios. (b) Link schematic diagrams.

Then, the measured amplitudes (discrete dots) and phase differences (discrete dots) of co-polarization and cross-polarization transmitted coefficients are given in Figure 3; β/π, axial ratio, and η are further derived and tagged with Exp in Figure 2d,e, which suggest that the measured results are basically identical to the simulated ones tagged with Sim, showing excellent LTC polarization performance in the operating frequency range. It should be noted that the simulated metasurface is an infinitely extended periodic structure, while the measured metasurface is a finite-sized structure, which inevitably introduces errors. In addition, errors may also be introduced during measurement. The results validate the proposed 2DM-EGA method of designing transmissive LTC PCMs.

6. Conclusions

This paper centers on the development of the optimal design for transmissive LTC PCMs. In particular, compared with EGA, the proposed 2DM-EGA is implemented in a 2D pixelated metasurface, involving the impact of mutated pixels on neighboring pixels, and has a faster convergence. Moreover, working together with the designed RFF pertaining to an ellipticity angle β and transmission efficiency η, Python-based 2DM-EGA is utilized to automatically obtain the pixelated metasurface that attains optimal targets. Then, the optimized transmissive metasurface operates in the frequency range of 8.16 GHz to 11.5 GHz with a reduced ellipticity angle β/π ≥ 0.15 and a relative bandwidth of 33.5%, and the measurements are basically identical to the simulations, which exhibit an excellent LTC polarization conversion performance and validate the proposed optimization design method. Moreover, the LTC polarization conversion’s physical mechanisms are discussed. For the optimal design of metasurfaces with different functions, the 2DM-EGA design method remains applicable as long as the fitness function is modified according to the specific function.

Author Contributions

J.W.: Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—Review and Editing, Funding acquisition. W.X.: Software, Validation. H.Z.: Validation. C.X.: Formal analysis, Investigation. Y.J.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Province (grant number 2025GXNSFAA069595), National Natural Science Foundation of China (62371147, 62561016), and Project of Guangxi Wireless Broadband Communication and Signal Processing Key Laboratory (AD25069102).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Chao Xu was employed by the company 22nd Research Institute of China Electronics Technology Group Corporation. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Kossel, M.A.; Kung, R.; Benedickter, H.; Biichtokd, W. An active tagging system using circular-polarization modulation. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 1999, 47, 2242–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, S.M.A.M.H.; Behdad, N. Wideband linear-to-circular polarization converters based on miniaturized-element frequency selective surfaces. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2016, 64, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Wang, Y.; He, J.; Hao, H.; Ma, X.; Huang, X. Broadband and high-efficient reflective linear-to-circular polarizer with Wi-Fi shaped metasurface. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2022, 55, 325002. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesauer, K.; Jördens, C. Recent advances in birefringence studies at THz frequencies. J. Infrared Millim. Terahz Waves 2013, 34, 663–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Pu, H.; Xu, J.; Xu, R.; Yuan, L. Controlling the abrupt autofocusing of circular airy vortex beam via uniaxial crystal. Photonics 2022, 9, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Yu, X.; Cao, W.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, X. Ultra-wideband circular-polarization converter with micro-split Jerusalem-cross metasurfaces. Chin. Phys. B 2016, 25, 28102. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, Y.; Shi, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, G.; Liang, J. Ultra-wideband linear-to-circular polarization converter with ellipse-shaped metasurfaces. Opt. Commun. 2019, 451, 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Cheng, Y. Single-layer dual-band linear-to-circular polarization converter with wide axial ratio bandwidth and different polarization modes. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2019, 67, 4296–4301. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Chen, M.; Liu, H.; Teng, C.; Deng, H.; Yuan, L. Wideband circular polarization converter based on graphene metasurface at terahertz frequencies. Opt. Eng. 2019, 58, 043106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, A.K.; Ruan, C.; Chen, K. Dual-wide-band dual polarization terahertz linear to circular polarization converters based on bi-layered transmissive metasurfaces. Electronics 2019, 8, 869. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, H.; Song, W.; Wang, X. A broadband and wide-angle linear-to-circular polarization converter for mobile microwave wireless power transmission. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2024, 23, 1734–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, P.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, P.; Kanaujia, B.K.; Birwal, A. Design of a new metasurface and its application for linear to circular polarization conversion. Int. J. Electron. 2021, 108, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Li, S.; Cao, X.; Han, J.; Jidi, L.; Li, Y. Dual-band transmissive metasurface with linear to dual-circular polarization conversion simultaneously. AIP Adv. 2020, 10, 125025. [Google Scholar]

- Fahad, A.K.; Ruan, C.; Ali, S.A.K.M.; Nazir, R.; Ulhaq, T.; Ullah, S.; He, W. Triple-wide-band Ultra-thin Metasheet for transmission polarization conversion. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8810. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, J.; Chang, I.; Lim, J.S.; Woo, H.; Yook, J.G.; Cho, H.H. Flexible metasurface for microwave-infrared compatible camouflage via particle swarm optimization algorithm. Small 2023, 19, 2302848. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J.; Lu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y.; Che, Y.; Qi, K. Fast analysis and optimal design of metasurface for wideband monostatic and multistatic radar stealth. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 120, 205107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Yu, W.; Lin, T.; Deng, Y.; Liu, J. Ultra-wideband RCS reduction based on non-planar coding diffusive metasurface. Materials 2020, 13, 4773. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, C.; Han, L.; Liu, C.; Lu, X.; Sun, Z. Reflection-type 1-bit coding metasurface for radar cross section reduction combined diffusion and reflection. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2020, 53, 445107. [Google Scholar]

- Di, L.; Cao, X.; Tang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, X. A new coding metasurface for wideband RCS reduction. Radioengineering 2018, 27, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cao, X.; Gao, J.; Sun, Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Han, T.; Chen, W. Broadband diffusion metasurface based on a single anisotropic element and optimized by the simulated annealing algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Chen, C.; Wang, H.; Tsai, J.; Ni, W.X. Synthesis design of artificial magnetic metamaterials using a genetic algorithm. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 12806–12818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, S.; Yu, J.; Ma, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Xu, Z.; Qu, S. Ultra-wideband polarization conversion metasurface based on topology optimal design and geometry tailor. Appl. Comput. Electromagn. Soc. J. 2016, 31, 843–846. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, C.; Chen, J.; Li, Z.H.; Chen, L.; Huang, W.; Lu, M.H. Optimal design of broadband acoustic metasurface absorbers. Phys. Scr. 2023, 98, 025705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgese, M.; Costa, F.; Genovesi, S.; Monorchio, A.; Manara, G. Optimal design of miniaturized reflecting metasurfaces for ultra-wideband and angularly stable polarization conversion. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, X.C.; Jiang, Y.N.; Gu, W.Q.; Xu, K.D. Optimal design of broadband linear-to-circular polarization conversion metasurface. Mater. Des. 2024, 242, 113004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jin, C.; Jiang, Y.N.; Chen, Y.J. A terahertz wideband linear-to-circular polarization converter based on meandering-structured metasurface. Opt. Commun. 2023, 548, 129876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofi, M.A.; Saurav, K.; Koul, S.K. Linear-to-circular polarization converter with wide angular stability and near unity ellipticity-application to linearly polarized antenna array. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II 2022, 69, 4779–4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.Q.; Guo, J.X.; Huang, B.G.; Fang, L.B.; Chu, P.; Liu, X.W. Wideband linear-to-circular polarization conversion realized by a transmissive anisotropic metasurface. Chin. Phys. B 2018, 27, 054204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnieri, E.; Greco, F.; Amendola, G. A broadband, wide-angle scanning, linear-to-circular polarization converter based on standard jerusalem cross frequency selective surfaces. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2021, 69, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicandia, F.A.; Genovesi, S. Linear-to-circular polarization transmission converter exploiting meandered metallic slots. Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2022, 21, 2191–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Li, K.X.; Wu, X.B.; Xue, C.H.; Wang, G.F.; Xie, X.M.; Qin, M.M. Ultra-wideband linear-to-circular polarizer realized by bi-layer metasurfaces. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 18392–18401. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.D.; Hu, Y.W.; Zhou, W.Y.; Zhang, T.R. Research on the miniaturization method of the broadband linear-to-circular polarization conversion metasurface based on genetic algorithm. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 49038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Lopez, L.; Rodriguez-Cuevas, J.; Martinez-Lopez, J.I.; Martynyuk, A.E. A multilayer circular polarizer based on bisected split-ring frequency selective surfaces. Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2014, 13, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).