Integrating Industry 4.0 Technologies into 8D Methodologies: A Case Study in the Automotive Industry

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Analysis of the Component

3.2. Structure of the Case Study

4. The Case Study

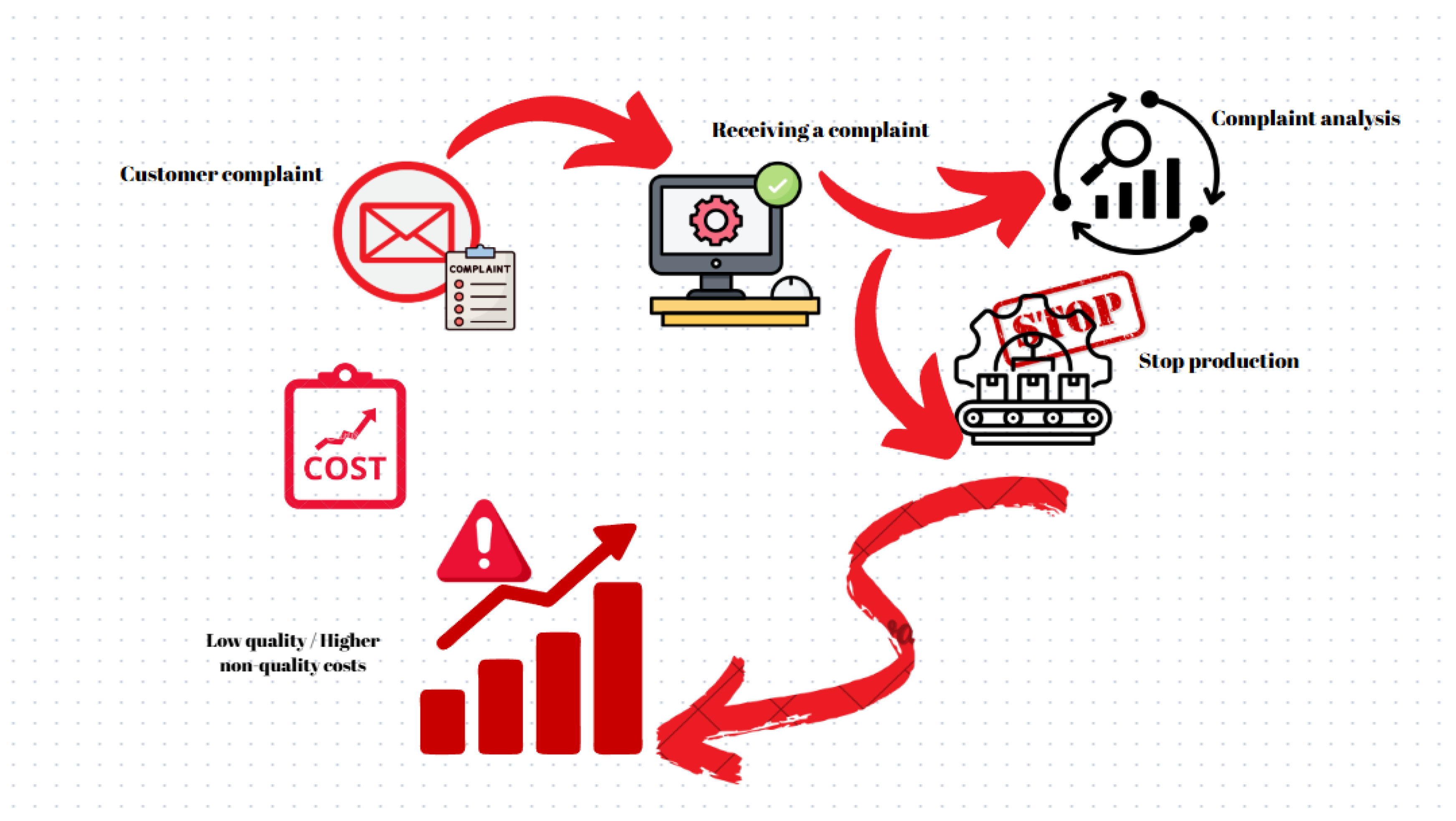

4.1. Presentation of Customer Complaint

4.2. Impact Analysis on Quality Indicators

- PPM—Parts per Million—External Client; maximum allowable value: 50,000 (5%);

- PPM—Parts per Million—Internal Nonconformities; maximum allowable value: 20,000 (2%);

- Non-quality costs.

- January: 450 parts delivered/430 nonconforming parts;

- February: 550 parts delivered/540 nonconforming parts;

- March: 300 parts delivered/300 nonconforming parts.

- January: 450 parts produced/20 nonconforming parts;

- February: 550 parts produced/10 nonconforming parts;

- March: 320 parts produced/20 nonconforming parts.

- CNC = Total non-quality cost;

- CR = Scrap cost (eliminated nonconforming parts);

- CS = Cost of repairs and rework;

- CE = Cost of additional inspections;

- CP = Cost of penalties, complaints, and returns.

- -

- The existence of a digital twin model of the production process.

- -

- Real-time communication with all equipment involved in the production process.

- ➢

- In the manufacturing process, parts in the production flow were sorted, resulting in 300 nonconforming parts;

- ➢

- In warehouse stock, existing parts were analyzed, and 500 nonconforming parts were isolated;

- ➢

- Spare parts are not applicable as they were not involved in this situation.

- ➢

- The inspection tools allow nonconforming parts to pass, as the templates for dimensional verification are incorrectly designed;

- ➢

- The working method used does not ensure repeatability in execution, generating variations in hole positioning;

- ➢

- The work instructions are not sufficiently clear or well-defined, leaving room for interpretation during execution;

- ➢

- The measurement method is not clearly established or standardized, resulting in inconsistency in inspections;

- ➢

- The laser equipment used for measurements is not properly calibrated, affecting measurement accuracy.

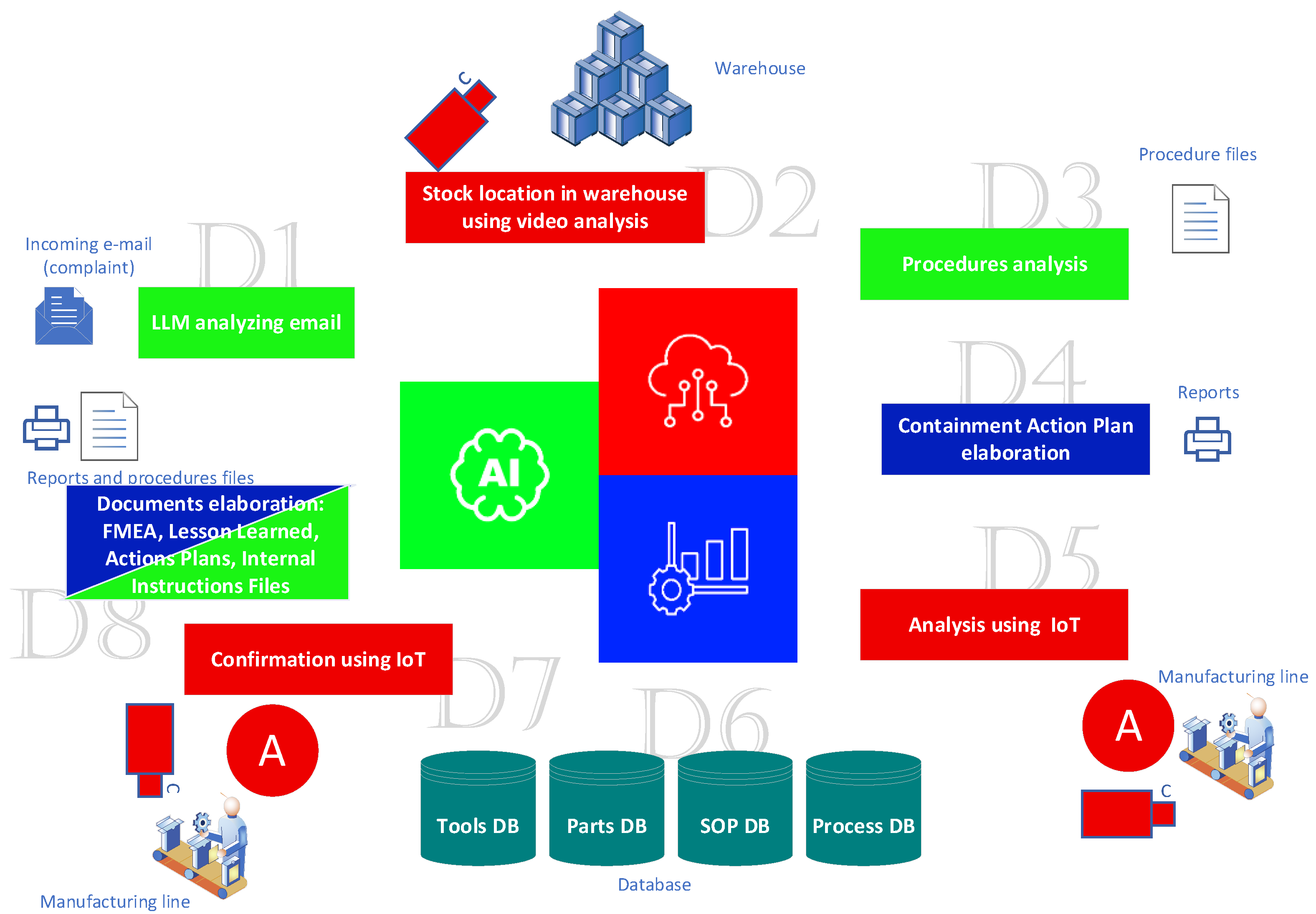

4.3. Presentation of the Solution

- -

- As equipment for detecting containers storing parts in the warehouse. The camera is positioned so that it can detect the labels on the storage containers of finished parts in the warehouse. In this way, the camera can continuously send images from the warehouse to the video analysis module. Here, the labels are extracted from these images, and the containers are identified. This allows the video analysis module to provide the location of the container with the parts of interest—enabling quick localization.

- -

- As equipment that captures images from the production process. These images are also sent to the video analysis module. Here, an operation is performed to identify the position of the holes and the shape of the part. The analysis extracts this data and stores it for defect identification or for identifying the corrections applied by the action plan.

4.4. Implementation of Corrective Actions

4.4.1. Analysis of Nonconforming Parts—Measured Results

- dx—direction along X;

- dz—direction along Z;

- dx/S or D—direction along X, left or right;

- dz/S or D—direction along Z, left or right.

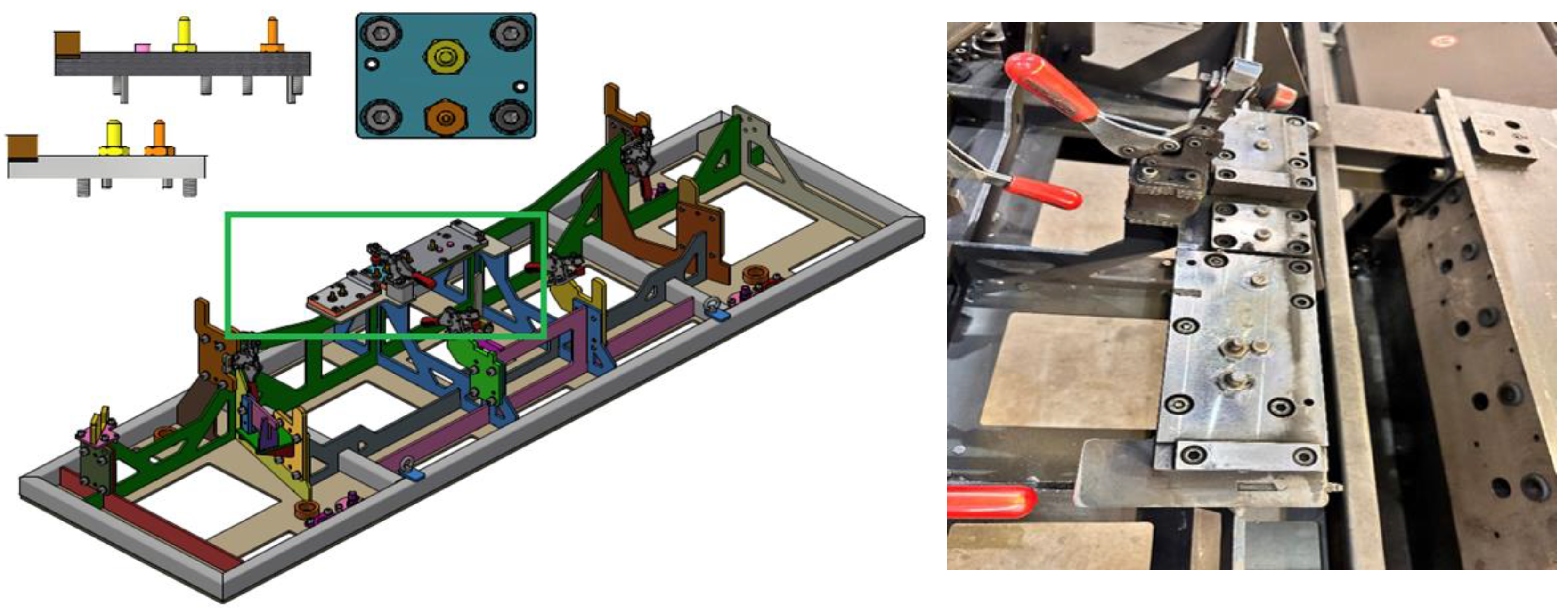

4.4.2. Manufacturing and Integration of Machined Blocks to Ensure Repeatability of Positioning on the X and Z Axis

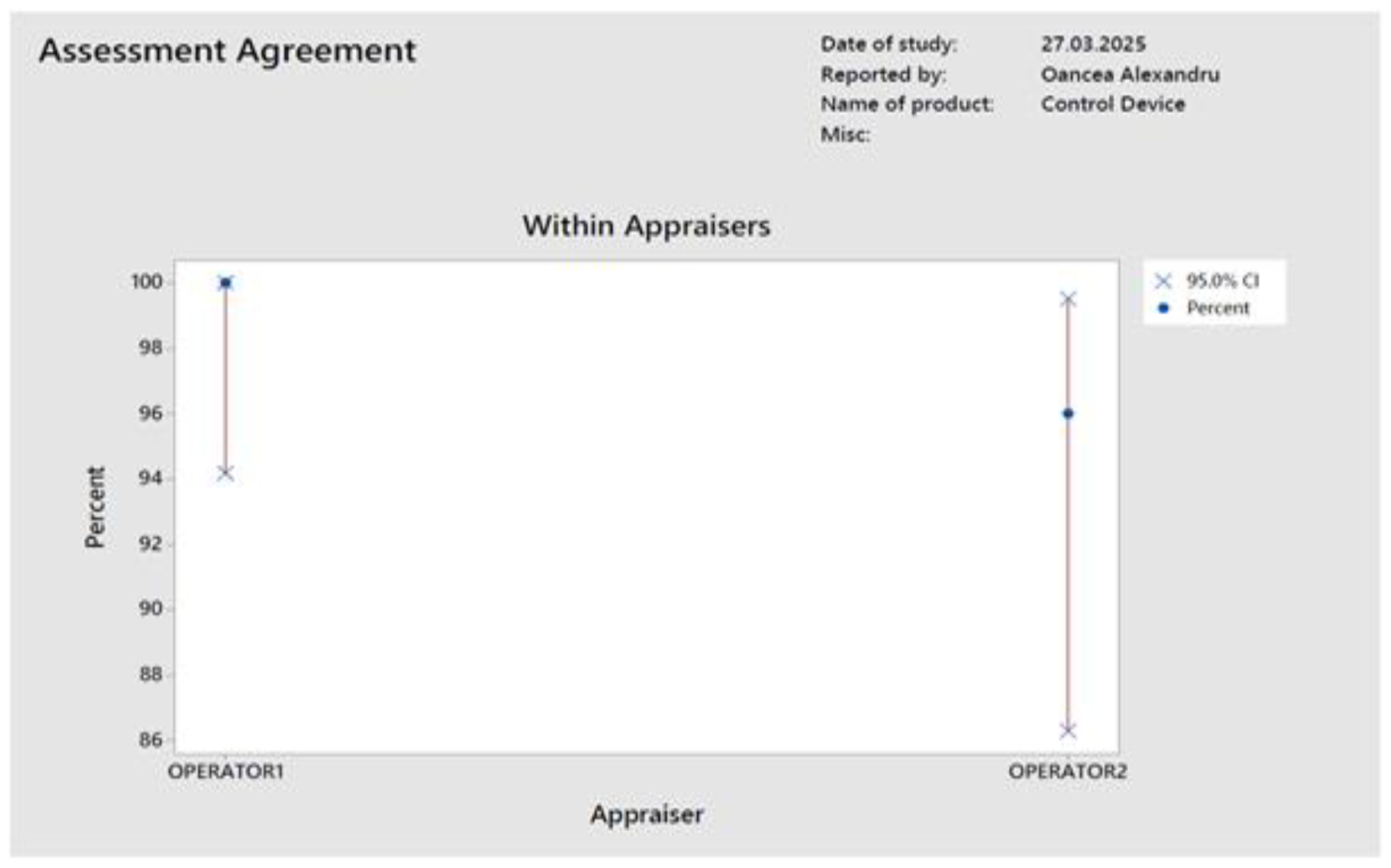

4.4.3. Calibration and Verification of the Fixture for Dimensional Inspection

4.4.4. Verification of Part Conformity

- CpK (Process Capability Index)

- ➢

- Minimum acceptable: Cpk ≥ 1.33

- ➢

- USL = Upper Specification Limit.

- ➢

- LSL = Lower Specification Limit.

- ➢

- X = Process mean.

- ➢

- σ = Short-term standard deviation (calculated from grouped data, e.g., samples of 5 parts, multiple sets).

- 2

- PpK (Process Performance Index)

- ➢

- Minimum acceptable: PpK > 1.50

- ➢

- s = Overall standard deviation of the process (long-term variation).

4.4.5. Verification of Actions Implementation and FMEA

5. Results

- March: 400 parts delivered/0 nonconforming parts delivered.

- April: 600 parts delivered/0 nonconforming parts delivered.

- March: 400 parts produced/0 nonconforming parts produced.

- April: 600 parts produced/0 nonconforming parts produced.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| RE Analysis | Root Cause Evaluation Analysis |

| PDCA | Plan-Do-Check-Act |

| VSM | Value Stream Mapping |

| FMEA | Failure Mode and Effects Analysis |

| PPM | Parts Per Millon—here regarding fault rate |

References

- Mahmood, K. Solving Manufacturing Problems with 8D Methodology: A Case Study of Leakage Current in a Production. Company. J. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2023, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pauliková, A. Visualization Concept of Automotive Quality Management System Standard. Standards 2022, 2, 226–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IATF 16949 GM Customer Specific Requirements—Effective 1 March 2025. Available online: https://www.iatfglobaloversight.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/IATF-16949-GM-Customer-Specific-Requirements-October-2025.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Ford Motor Company Customer Specific Requirements for IATF 16949:2016—Effective 23 June 2025. Available online: https://www.iatfglobaloversight.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Ford-IATF-CSR_June-2025-Release-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Lestyánszka Škůrková, K.; Fidlerová, H.; Niciejewska, M.; Idzikowski, A. Quality Improvement of the Forging Process Using Pareto Analysis and 8D Methodology in Automotive Manufacturing: A Case Study. Standards 2023, 3, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phanden, R.K.; Sheokand, A.; Goyal, K.K.; Gahlot, P.; Demir, H.I. 8Ds method of problem solving within automotive industry: Tools used and comparison with DMAIC. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 65, 3266–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enache, I.-C.; Chivu, O.R.; Rugescu, A.-M.; Ionita, E.; Radu, I.V. Reducing the Scrap Rate on a Production Process Using Lean Six Sigma Methodology. Processes 2023, 11, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.S.; Chen, J.C.M.; Shen, B.M.; Chen, G.Y.H. Implementation of Ford 8D in Improving Efficiencies of Wafer Testers: A Case Study. Eng. Manag. J. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barosani, S.; Bhalwankar, N.; Deshmukh, V.; Kokane, S.; Kulkarni, P.R. A review on 8D problem solving process. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2017, 4, 529–535. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Verma, M.; Dubey, D. Reducing the defects and improving the quality of manufacturing product (CT wheel/crain part) using 8D problem solving tool. Indian. J. Sci. Res. 2023, 3, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kempel, M.; Richter, R.; Deuse, J.; Schmid, S.; Schulte, L. Knowledge Graph-Based Approach for Interactive Problem Solving with the 8D Method. In Proceedings of the Smart Systems Integration Conference and Exhibition (SSI), Brugge, Belgium, 28–30 March 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Divanoğlu, S.U.; Taş, Ü. Application of 8D methodology: An approach to reduce failures in automotive industry. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 134, 106019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huszák, C.; Pinke, P.; Kovács, T.A. Tools for a Root Cause Analysis for Safety–Critical Components Areview. In The Impact of the Energy Dependency on Critical Infrastructure Protection, Proceedings of the ICCECIP 2024, Budapest, Hungary, 7–8 November 2024; Kovács, T.A., Stadler, R.G., Daruka, N., Eds.; Advanced Sciences and Technologies for Security Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ichimov, M.A.M.; Popescu, M.V.; Negoita, O.D.; Costea-Marcu, I.C.; Moiceanu, G. Proposal for software management solution to prevent potential issues. U.P.B. Sci. Bull. Ser. C 2025, 87, 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, L.; Huang, H.; Chen, S.H. Product quality detection through manufacturing process based on sequential patterns considering deep semantic learning and process rules. Processes 2020, 8, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozyiğit, F.; Doğan, O.; Kılınç, D. Categorization of customer complaints in food industry using machine learning approaches. J. Intell. Syst. Theory Appl. 2022, 5, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Yao, X. Smart logistics warehouse moving-object tracking based on YOLOv5 and DeepSORT. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmatov, N.; Paul, A.; Saeed, F.; Hong, W.H.; Seo, H.; Kim, J. Machine learning–based automated image processing for quality management in industrial Internet of Things. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2019, 15, 1550147719883551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.; Alvelos, H.; Rosa, M.J. Quality 4.0: Results from a systematic literature review. TQM J. 2025, 37, 379–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, D.; Potra, S.; Pugna, A. Enhancement of Customer Complaints: Digitalization of Synchronous Model for Problem-Solving of Manufacturing Complaints. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 242, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietsch, D.; Matthes, M.; Wieland, U.; Ihlenfeldt, S.; Munkelt, T. Root cause analysis in industrial manufacturing: A scoping review of current research, challenges and the promises of AI-driven approaches. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, M.; Bücker, I.; Otto, B. Industrie 4.0 process transformation: Findings from a case study in automotive logistics. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2020, 31, 935–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Realyvásquez-Vargas, A.; Arredondo-Soto, K.C.; García-Alcaraz, J.L.; Macías, E.J. Improving a Manufacturing Process Using the 8Ds Method. A Case Study in a Manufacturing Company. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, R.; Reddy, M.C.G.; Narayana, A.L.; Narayana, U.L.; Rahman, M.S. Investigation and implementation of 8D methodology in a manufacturing system. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 50, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oancea, A.-V.; Rontescu, C.; Bogatu, A.-M.; Cicic, D.-T. Using the Ishikawa diagram for problem analysis in the laser cutting process. J. Res. Innov. Sustain. Soc. (JRISS) 2024, 6, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PDCA | Steps | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Plan | D1. Issue details | The working team must define the problem very clearly and precisely. The root cause of the problem is found by using quality tools like the 5W & 2H (What, Where When, Why, Who & How, How Many) Affinity Diagram [9]. |

| D2. Immediate checking actions | This stage aims to initiate immediate verification actions to assess whether the reported defect is also present in other similar products or within the same family of parts. The existing stock of similar products is analyzed to detect other products with the same nonconformity risk. | |

| D3. Initial analysis | This step is used to identify the causes of the failure to detect the problem: In what place should the nonconformity be detected? Why wasn’t the nonconformity detected? | |

| D4. Immediate action plans | In this stage, immediate action plans are defined and implemented to protect internal and external customers from the problem until permanent corrective actions can be put in place. | |

| Do | D5. Final analysis | The aim of this step is to obtain a real and complete of the situation to identify the root causes and to decide the optimum actions required for the treatment of the causes. |

| D6. Final action plan | The purpose of this step is to develop an action plan to eliminate the root causes identified in steps 3 and 5. Permanent actions are analyzed and implemented to prevent the recurrence of the problem. | |

| Check | D7. Action plan confirmation. | Step 7 of the 8D methodology is very important because it allows for the closing of the action plans. The effectiveness of the final action plans is verified. This is a key step aimed at preventing the recurrence of the quality problem. |

| Act | D8. Prevention problem recurrence | This step involves modifying specifications, updating training, reviewing workflows and improving practices and procedures. These changes are necessary to prevent recurrence and similar problems in the future. |

| Material: S235JRH | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C [%] | Si [%] | Mn [%] | P [%] | S [%] | Al [%] | Ni [%] | Mo [%] | Cu [%] | V [%] | Ti [%] |

| 0.064 | 0.017 | 0.34 | 0.012 | 0.01 | 0.039 | 0.02 | 0.002 | 0.02 | 0.003 | 0.001 |

| Costs | ||

| January | February | March |

| CNC = 10,285 Euro | CNC = 12,916 Euro | CNC = 7176 Euro |

| CR = 10,285 Euro | CR = 12,916 Euro | CR = 7176 Euro |

| CS = 0 | CS = 0 | CS = 0 |

| CE = 0 | CE = 0 | CE = 0 |

| CP = 0 | CP = 0 | CP = 0 |

| D1. Issue Details | Date Alert: 20 March 2025 | |||

| Report Nr: | 1 | |||

| Customer: | X | Affected Quantity | 300 parts | |

| Problem Description: | Positioning deviations of the holes in relation to the X and Z axes compared to the nominal values specified in the technical documentation | |||

| Repetitive problem: | YES | NO | ||

| D2. Immediate Checking Action | |||

| Are There Other Similar Products Involved? | |||

| Can this Defect Also Appear on Other Similar Parts? | |||

| YES | NO | Comments | |

| Other parts | X | ||

| Products from the same family | X | Stocks of similar references were analyzed, and it was found that the problem also occurs in these. | |

| Left/Right | X | ||

| Symmetrical products | X | ||

| Front/Rear | X | ||

| Others | X | ||

| D3. Initial Analysis | ||

| At What Stage of the Manufacturing Process Should the Nonconformity Have Been Detected? | YES | NO |

| During the manufacturing process | x | |

| On the finished product (e.g., Control Plan) | x | |

| Before delivery | x | |

| What are the reasons why it was not detected? | ||

| Verification means allowing nonconforming parts to pass. | ||

| D4. Immediate Action Plan | |||

| What actions have been taken to prevent the delivery of nonconforming products to the customer? | |||

| Actions | Conforming quantity | Nonconforming quantity | |

| In the manufacturing process | Stock sorting | 300 | |

| Warehouse stock | Stock sorting | 500 | |

| Spare parts | Not applicable | 0 | |

| How are the conforming products identified? | |||

| By verification using 3D control. | |||

| Delivery date | Not delivered/production stopped. | ||

| Remarks | Not delivered/production stopped. | ||

| D5. Final Analysis | Analysis Date: | 25 March 2025 |

Indicate the real causes across the process:

| ||

| Causes | Responsible | Department |

| Verification means allowing nonconforming parts to pass. The dimensional inspection gauges/checking jigs are incorrectly designed. | Method Specialist | Technical |

| The work procedure used does not guarantee process repeatability. | Method Specialist | Technical |

| Contamination of the positioning device supports residues. | Production Responsible | Production |

| The measurement method is not clearly defined. | Quality Analyst | Quality |

| The laser system shows nonconforming calibration with the specified operational parameters. | Method Specialist | Technical |

| The laser system’s clamping devices do not ensure effective immobilization of the part during the cutting process along the X and Z axes. | Method Specialist | Technical |

| The operator does not have the necessary qualifications and has not received adequate training for proper equipment operation. | Training Responsible | Training |

| Improper positioning of the parts in the clamping device, caused by the lack of experience and skill of the new operator. | Training Responsible | Training |

| The locking elements related to the X and Z axes show deformations in the upper area. | Method Specialist | Technical |

| D6. Final Action Plan | Application Date: | 26 March 2025 | ||

| What actions have been implemented to prevent the future manufacturing of nonconforming products? (securing, Poka Yoke, process control, …) | ||||

| Action | Responsible | Department | Planned Date | Completion Date |

| Creation of a jig for checking hole positions (attributive) | Method Specialist | Technical | W13 | W13 |

| Manufacturing and integration of machined blocks to ensure limitation and repeatability of positioning along the Z axis | Method Specialist | Technical | W13 | W13 |

| Calibration and verification of the dimensional inspection device. | Quality Analyst | Quality | W13 | W13 |

| D7. Action Plan Confirmation | Date: | 31 March 2025 | |

| Have the actions taken been confirmed as effective? | Yes | No | |

| x | |||

| How? | |||

| 8D Audit | |||

| Attach evidence such as dimensional reports, capability results, attribute inspection reports, … to this document. | |||

| Date: 31 March 2025 Prepared by: Alexandru OANCEA Department: Quality | Nonconformity: Positioning Deviations of the Holes in Relation to the X and Z Axes Compared to the Nominal Values Specified in the Technical Documentation | |||

| Subject: 8D Follow-up Audit Status Following CUSTOMER/INTERNAL Complaint | ||||

| Expected: Validation of the action plan with due date as of the 8D audit. | ||||

| No. | Action | Completion Percentage (%) | Closing Date | Responsible |

| 1 | Creation of a jig for checking hole positions (attributive) | 100% | Week 13 | Technical |

| 2 | Manufacturing and integration of machined blocks to ensure limitation and repeatability of positioning along the Z axis | 100% | Week 13 | Technical |

| 3 | Calibration and verification of the dimensional inspection device | 100% | Week 13 | Quality |

| D8. Prevention of Problem Recurrence | Closing Date | 31 March 2025 | ||

| Yes/No | Responsible | Department | Deadline | |

| Internal training sheets | Yes | Method Specialist | Technical | W14 |

| Manufacturing ranges | Yes | Method Specialist | Technical | W14 |

| Control plans, control charts | Yes | Quality Engineer | Quality | W15 |

| FMEA/AMDEC | Yes | Pilot FMEA | Quality | W16 |

| Lesson learned | No | |||

| Plans | No | |||

| Inspection tools, gauges | Yes | Method Specialist | Technical | W15 |

| Others | No | |||

| Supplier follow-up | No | |||

| Axis | Nominal | Lower Tolerance | Upper Tolerance | Measured Part 1 | Measured Part 2 | Measured Part 3 | Maximum Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dx | 1722.1 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 1720.479 | 1720.89 | 1720.973 | −1.621 |

| dz | 136.335 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 136.335 | 136.358 | 136.346 | −0.165 |

| dx | 1624.4 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 1622.794 | 1623.159 | 1623.285 | −1.606 |

| dz | 206.8 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 206.669 | 206.363 | 206.692 | −0.164 |

| dx | 199.6 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 198.222 | 198.594 | 198.733 | −1.378 |

| dz | 206.8 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 206.8 | 206.621 | 206.668 | −0.179 |

| dx | 101.9 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 100.567 | 100.914 | 101.062 | −1.333 |

| dz | 136.5 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 136.41 | 136.306 | 136.362 | −0.986 |

| dx | 11 | −1 | +1 | 11.23 | 11.228 | 11.237 | 0.237 |

| dx | 13 | −1 | +1 | 13.324 | 13.281 | 13.296 | 0.296 |

| dz/S | 7 | −1 | +1 | 7.257 | 7.177 | 7.221 | 0.257 |

| dx/D | 7 | −1 | +1 | 7.234 | 7.286 | 7.179 | 0.286 |

| dz | 103.4 | −1 | +1 | 103.09 | 103.09 | 103.196 | −0.310 |

| dx | 110.2 | −1 | +1 | 109.874 | 109.86 | 109.919 | −0.340 |

| dz | 42.6 | −1 | +1 | 41.711 | 41.668 | 41.818 | −0.932 |

| dx | 55.8 | −1 | +1 | 56.882 | 55.902 | 56.96 | 1.160 |

| 45 | −1 | +1 | 45.119 | 45.15 | 45.221 | 0.221 | |

| 15 | −1 | +1 | 14.658 | 14.554 | 14.612 | −0.342 | |

| 15 | −1 | +1 | 15.338 | 15.252 | 15.224 | 0.224 | |

| 45 | −1 | +1 | 45.19 | 45.321 | 45.37 | 0.370 | |

| 0 | 0 | +2 | 0.744 | 0.834 | 0.646 | 0.834 | |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.118 | 0.083 | 0.176 | 0.176 | |

| dx | 877 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 876.425 | 876.772 | 876.989 | −0.575 |

| dx | 70 | −0.5 | +0.5 | 69.997 | 69.973 | 70.283 | 0.283 |

| dz | 37 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 36.887 | 37.129 | 37.333 | 0.333 |

| dx | 1824 | −1.5 | +2.5 | 1823.097 | 1824.587 | 1823.494 | −0.913 |

| dx | 40.4 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 39.951 | 40.418 | 40.535 | −0.449 |

| dz | 19 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 19.467 | 19.229 | 19.32 | 0.467 |

| dx | 89.7 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 89.269 | 89.658 | 89.714 | −0.431 |

| dz | 104.3 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 104.782 | 104.895 | 104.776 | 0.595 |

| dx | 170.3 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 169.688 | 170.099 | 170 | −0.612 |

| dz | 199 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 198.841 | 198.91 | 199.08 | −0.159 |

| dx | 229.3 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 228.905 | 229.189 | 229.337 | −0.395 |

| dz | 214.8 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 214.353 | 214.773 | 214.947 | −0.447 |

| dx | 339.634 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 339.634 | 340.078 | 340.191 | −0.766 |

| dz | 244.184 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 244.5 | 244.376 | 244.462 | −0.316 |

| dx | 517.4 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 516.882 | 517.358 | 517.437 | −0.518 |

| dz | 292 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 291.347 | 219.367 | 291.349 | −0.653 |

| dx | 567.9 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 567.457 | 567.756 | 568.157 | −0.443 |

| dz | 305.5 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 304.678 | 304.645 | 304.965 | −0.822 |

| dx | 712 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 711.431 | 711.958 | 712.035 | −0.569 |

| dz | 321.8 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 320.9 | 321.184 | 321.135 | −0.900 |

| dx | 712 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 711.431 | 711.958 | 712.035 | −0.569 |

| dz | 321.8 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 320.9 | 321.184 | 321.135 | −0.9 |

| dx | 833.6 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 833.172 | 833.874 | 833.455 | −0.145 |

| dz | 350 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 324.232 | 324.466 | 323.994 | −1.006 |

| dx | 990.4 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 990.148 | 990.599 | 990.817 | 0.199 |

| dz | 325 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 324.475 | 323.96 | 323.994 | −1.006 |

| dx | 1653.3 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 1652.786 | 1635.18 | 1653.135 | −0.12 |

| dz | 199 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 198.503 | 197.575 | 197.714 | −0.1425 |

| dx | 1594.7 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 1594.29 | 1594.422 | 1594.6 | −0.278 |

| dz | 214.8 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 213.884 | 213.343 | 213.447 | −1.366 |

| dx | 1483.7 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 1482.973 | 1483.437 | 1483.506 | −0.263 |

| dz | 244.5 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 243.876 | 243.165 | 243.345 | −1.335 |

| dx | 1306.6 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 1306.053 | 1306.6 | 1306.418 | −0.182 |

| dz | 292 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 291.238 | 290.91 | 290.82 | −1.18 |

| dx | 1112 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 1111.483 | 1111.75 | 1111.871 | −0.25 |

| dz | 321 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 321.003 | 320.492 | 320.678 | −1.35 |

| dx | 1256.1 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 1255.515 | 1256.06 | 1256.009 | −0.04 |

| dz | 305 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 304.813 | 304.342 | 304.453 | −1.258 |

| dz/S | 345 | −1 | +1 | 344.312 | 344.504 | 344.89 | −0.498 |

| dz/D | 345 | −1 | +1 | 344.026 | 344.248 | 344.08 | −0.92 |

| dz | 5 | −1 | +1 | 4.922 | 4.815 | 4.852 | −0.185 |

| dz | 5 | −1 | +1 | 5.107 | 5.047 | 5.029 | 0.047 |

| dz | 12 | −1 | +1 | 11.613 | 11.704 | 11.623 | −0.387 |

| dz | 12 | −1 | +1 | 11.691 | 11.759 | 11.722 | −0.309 |

| dz | 17.1 | −1 | +1 | 16.838 | 17.207 | 17.302 | −0.262 |

| dz | 17.1 | −1 | +1 | 17.196 | 18.167 | 16.989 | 1.067 |

| Nominal Dimension | Lower Tolerance | Upper Tolerance | Measured Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| 344 | −0.050 | +0.050 | 343.988 |

| 344 | −0.050 | +0.050 | 344.356 |

| 344 | −0.050 | +0.050 | 344.349 |

| 344 | −0.050 | +0.050 | 343.847 |

| 1825.3 | −0.1 | +0.1 | 1826.603 |

| 1827.66 | −0.1 | +0.1 | 1828.980 |

| Nominal Dimension | Lower Tolerance | Upper Tolerance | Measured Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| 344 | −0.050 | +0.050 | 343.988 |

| 344 | −0.050 | +0.050 | 343.997 |

| 344 | −0.050 | +0.050 | 344.0.47 |

| 344 | −0.050 | +0.050 | 344.039 |

| 1825.3 | −0.1 | +0.1 | 1825.314 |

| 1827.66 | −0.1 | +0.1 | 1827.569 |

| Nominal Dimension | Lower Tolerance | Upper Tolerance | Minimum Measured Value | Average Value | Maximum Measured Value | CpK | PpK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1722.1 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 1721.6 | 1722.023 | 1722.28 | 1.62 | 1.64 |

| 136.335 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 136.134 | 136.719 | 136.4 | 1.71 | 1.77 |

| 1624.4 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 1624.21 | 1624.468 | 1624.78 | 2.14 | 2.07 |

| 206.8 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 206.568 | 206.864 | 207.219 | 1.59 | 1.54 |

| 199.6 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 199.234 | 199.591 | 199.94 | 1.77 | 1.72 |

| 101.9 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 101.675 | 101.916 | 102.227 | 1.94 | 1.87 |

| 136.5 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 136.067 | 136.513 | 136.956 | 1.48 | 1.58 |

| 11 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 10.773 | 11.013 | 11.232 | 2.41 | 2.15 |

| 13 | −1 | +1 | 12.635 | 13.009 | 13.488 | 1.46 | 1.55 |

| 7 | −1 | +1 | 6.662 | 6.971 | 7.428 | 1.63 | 1.74 |

| 7 | −1 | +1 | 6.620 | 6.965 | 7.378 | 1.79 | 1.73 |

| 104.3 | −1 | +1 | 103.7 | 104.272 | 104.678 | 1.39 | 1.52 |

| 110.2 | −1 | +1 | 109.739 | 110.198 | 110.59 | 1.85 | 1.89 |

| 42.6 | −1 | +1 | 42.378 | 42.663 | 43.110 | 1.51 | 1.59 |

| 55.8 | −1 | +1 | 55.435 | 55.808 | 56.154 | 1.61 | 1.69 |

| 45 | −1 | +1 | 44.468 | 45.001 | 45.403 | 1.73 | 1.66 |

| 15 | −1 | +1 | 14.622 | 15.002 | 15.461 | 1.55 | 1.63 |

| 15 | −1 | +1 | 14.590 | 14.996 | 15.459 | 1.71 | 1.62 |

| 0 | 0 | +1 | 0.231 | 0.770 | 0.509 | 1.56 | 1.68 |

| 0 | 0 | +2 | 0.475 | 0.992 | 1.542 | 1.51 | 1.51 |

| 877 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 876.34 | 876.948 | 877.305 | 1.55 | 1.53 |

| 70 | −0.5 | +0.5 | 69.685 | 69/963 | 70.297 | 1.92 | 1.86 |

| 37 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 36.579 | 37.002 | 37.251 | 1.77 | 1.89 |

| 1824 | −1.5 | +2.5 | 1823.41 | 1823.932 | 1824.56 | 1.76 | 1.69 |

| 40.4 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 40.0571 | 40.772 | 40.3722 | 1.68 | 1.78 |

| 19 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 18.643 | 18.990 | 19.292 | 1.69 | 1.69 |

| 89.7 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 89.379 | 89.722 | 90.005 | 1.86 | 1.74 |

| 104.3 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 103.964 | 104.291 | 104.675 | 1.96 | 1.84 |

| 170.3 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 169.985 | 170.598 | 170.263 | 1.76 | 1.70 |

| 199 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 198.571 | 198.997 | 199.311 | 1.62 | 1.69 |

| 229.3 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 228.983 | 229.320 | 229.850 | 1.55 | 1.50 |

| 214.8 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 214.417 | 214.809 | 215.272 | 1.57 | 1.64 |

| 339.634 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 339.313 | 339.658 | 339.998 | 1.50 | 1.55 |

| 244.184 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 243.898 | 244.214 | 244.554 | 1.78 | 1.82 |

| 517.4 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 516.071 | 517.325 | 517.635 | 1.45 | 1.52 |

| 292 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 291.587 | 292.004 | 292.587 | 1.60 | 1.65 |

| 567.9 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 567.479 | 567.901 | 568.421 | 1.47 | 1.53 |

| 305.5 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 305.109 | 305.485 | 305.996 | 1.92 | 1.83 |

| 712 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 711.54 | 712.978 | 712.342 | 1.85 | 1.62 |

| 321.8 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 321.524 | 321.786 | 322.149 | 2.22 | 1.94 |

| 833.6 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 833.310 | 833.582 | 834.926 | 1.76 | 1.85 |

| 350 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 349.678 | 350.014 | 350.373 | 1.75 | 1.84 |

| 990.4 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 990.075 | 990.417 | 990.758 | 1.54 | 1.60 |

| 325 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 324.760 | 325.051 | 325.386 | 2.00 | 1.93 |

| 1653.3 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 1652.910 | 1653.318 | 1653.700 | 1.51 | 1.50 |

| 199 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 198.719 | 199.024 | 199.358 | 1.57 | 1.57 |

| 1594.124 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 1593.840 | 1594.092 | 1594.390 | 1.96 | 1.90 |

| 214.8 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 214.421 | 215.026 | 214.802 | 1.92 | 2.10 |

| 1483.7 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 1483.42 | 1483.695 | 1484.060 | 1.72 | 1.80 |

| 244.5 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 244.281 | 244.512 | 244.893 | 2.01 | 2.03 |

| 1306.6 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 1306.310 | 1306.621 | 1307.160 | 1.56 | 1.64 |

| 292 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 291.843 | 291.981 | 292.149 | 3.60 | 3.47 |

| 1112 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 1111.79 | 1112.002 | 1112.130 | 3.55 | 3.79 |

| 321 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 320.659 | 321.014 | 321.308 | 1.44 | 1.50 |

| 1256.1 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 1255.72 | 1256.079 | 1256.480 | 1.51 | 1.57 |

| 305 | −0.8 | +0.8 | 304.640 | 305.025 | 305.372 | 1.46 | 1.58 |

| 345 | −1 | +1 | 344.606 | 344.954 | 345.372 | 1.76 | 1.70 |

| 345 | −1 | +1 | 344.474 | 345.003 | 345.314 | 1.77 | 1.89 |

| 5 | −1 | +1 | 4.615 | 4.992 | 5.49 | 1.54 | 1.62 |

| 5 | −1 | +1 | 4.696 | 5.016 | 5.546 | 1.80 | 1.83 |

| 12 | −1 | +1 | 11.593 | 12.022 | 12.465 | 1.58 | 1.65 |

| 12 | −1 | +1 | 11.349 | 11.995 | 12.428 | 1.52 | 1.53 |

| 17.1 | −1 | +1 | 16.809 | 17.106 | 17.520 | 2.22 | 2.13 |

| 17.1 | −1 | +1 | 16.674 | 17.136 | 17.540 | 1.75 | 1.62 |

| Failure Effects (FE) | S | Failure Mode (FM) of Process Step | Failure Cause (FC) of Work Element | Current Prevention Control of FC | O | Current Detection Control of FC & FM | D | AP | Prevention Action | Detection Action | Status | S | O | D | AP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Impossibility of mounting on the customer intern: 5 next customer: 5 final customer: 6 | 6 | Positioning deviations of the holes relative to the X and Z axes compared to the nominal values specified in the technical documentation | The inspection tools promote non-conforming parts; the templates for dimensional inspection of parts are incorrectly designed | General rules for laser tube | 7 | Checking of information on the drawing and OF | 7 | M | Manufacturing and integration of machined blocks to ensure limitation and repeatability of positioning on the X, Z axis. | Creation of a template for checking hole positioning (attribute-based). Three-dimensional control of one piece per batch. Process monitoring through statistical process control. | 100% | 6 | 4 | 5 | L |

| 2 | Impossibility of mounting on the customer intern: 5 next customer: 5 final customer: 6 | 6 | Positioning deviations of the holes relative to the X and Z axes compared to the nominal values specified in the technical documentation | The locking elements related to the X and Z axes show deformations in the upper area | General rules for laser tube | 7 | Frequency self-control rates realized by the operator and quality inspector that is documented on OF; checking of the first part | 6 | M | Manufacturing and integration of machined blocks to ensure limitation and repeatability of positioning on the X, Z axis. | Calibration and verification of dimensional inspection device. | 100% | 6 | 4 | 5 | L |

| 3 | Impossibility of mounting on the next step intern: 8 next customer: 8 final customer: 8 | 8 | Position NC of the hole | Bad set up of the glasses by operator | Checking of the glasses with the caliper after each set up of the machine; FI-RO 780 General rules for laser tube (checking of each start up of the set up the glasses) | 3 | Checking of the first part and Frequency Checking | 3 | L | |||||||

| 4 | Impossibility of mounting on the next step intern: 8 next customer: 8 final customer: 8 | 8 | Position NC of the hole | Gap machine on y | FI-RO-780 Laser tubes general rules the checking of the set up of the machine on y | 3 | Checking of the first part and Frequency Checking | 3 | L | |||||||

| 5 | Impossibility of mounting on the next step intern: 8 next customer: 8 final customer: 8 | 8 | Position NC of the hole | Defect of straighteness of tube | Integration in laser tubes general rules the checking of straighteness of tube | 3 | Checking of the first part and Frequency Checking | 3 | L |

| Component | Specifications | No |

|---|---|---|

| Video camera (simulation using images) | Surveillance camera Imou (Dahua Technology, Hangzhou, China) 5 MP Resolution 2592 × 1458 | 4 |

| Current consumption measurement circuit | Pressac CT Clamp + gateway 60A | 2 |

| Server | Intel Core i9, 2,6 GHz, 14 cores, 40 GB RAM, 1 TB SSD | 1 |

| Communications | Existent infrastructure (cables, routers, switches) | 1 |

| Parameter | Our Solution | Current Solution (Before) |

|---|---|---|

| Complaint analysis and notification of the parties involved in resolution | Less 1 min | 2–5 h |

| Identification of batches in warehouses | Less 1 min | 1–2 h |

| Problem detection through flow analysis | Less 1 min | 5–8 h |

| Preparation of documents: immediate action plan, FMEA, lessons learned, action plan, internal training sheets | Minutes (including printing) | Min 24 h—days |

| Data collection from equipment | Automatic using IoT—real time monitoring for more days | Manually by production engineer and operator—real-time monitoring very limited |

| Entry of data collected as a result of the 8D analysis | Automatically by storing in database | Manually by quality team |

| Component | [16] | [17] | [18] | [19] | [20] | [21] | [22] | Our Solution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLM for complaints | Yes (simple) | Yes (BERT) | No | No | No | No | No | Complete LLM |

| Email connector | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Computer vision in warehouse | No | No | Yes (Yolov5) | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| IoT in data acquisition | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Real time monitoring | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Root cause AI | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Engine report | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Complete 8D cover | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Complete |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oancea, A.-V.; Ionescu, N.; Rontescu, C.; Ionescu, L.-M.; Misztal, A.; Bogatu, A.-M.; Cicic, D.-T.; Pirvu, V. Integrating Industry 4.0 Technologies into 8D Methodologies: A Case Study in the Automotive Industry. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11262. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011262

Oancea A-V, Ionescu N, Rontescu C, Ionescu L-M, Misztal A, Bogatu A-M, Cicic D-T, Pirvu V. Integrating Industry 4.0 Technologies into 8D Methodologies: A Case Study in the Automotive Industry. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(20):11262. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011262

Chicago/Turabian StyleOancea, Alexandru-Vasile, Nadia Ionescu, Corneliu Rontescu, Laurentiu-Mihai Ionescu, Agnieszka Misztal, Ana-Maria Bogatu, Dumitru-Titi Cicic, and Valentin Pirvu. 2025. "Integrating Industry 4.0 Technologies into 8D Methodologies: A Case Study in the Automotive Industry" Applied Sciences 15, no. 20: 11262. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011262

APA StyleOancea, A.-V., Ionescu, N., Rontescu, C., Ionescu, L.-M., Misztal, A., Bogatu, A.-M., Cicic, D.-T., & Pirvu, V. (2025). Integrating Industry 4.0 Technologies into 8D Methodologies: A Case Study in the Automotive Industry. Applied Sciences, 15(20), 11262. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011262

.jpg)