Abstract

Edible insects represent an emerging and sustainable alternative in human nutrition, characterized by their high protein and fiber content, along with a lipid profile rich in unsaturated fatty acids. This study evaluated the technological feasibility and impact of incorporating Acheta domesticus powder (10% and 20% as a substitution of pork meat) into patties, assessing their proximate composition, physicochemical properties, texture profile (TPA), cooking characteristics, and sensory acceptance. Cricket powder (ADP) increased protein and fiber in the meat product, improved texture and reduced cooking losses. Reformulation with 20% substitution led to significant changes in composition, physicochemical properties, and texture and decreased sensory acceptance, while 10% substitution achieved higher sensory ratings with improved nutritional benefits. In conclusion, optimizing the color of these products is essential to enhance consumer acceptance and promote the development of novel formulations based on insect-derived alternative proteins.

Keywords:

Acheta domesticus; edible insect; powder; patty; meat substitution; sustainable; novel food; protein 1. Introduction

The increasing demand for sustainable, nutritious, and functional food sources has brought alternative proteins, such as edible insects, to the forefront of scientific and technological interest [1]. This emerging resource offers great potential for responding to the challenges associated with global population growth and the progressive limitation of traditional cattle farming resources in the future. Several studies suggest that, in the coming decades, food sovereignty will face severe pressure due to the sustained increase in demand for animal protein. The world’s population is expected to continue growing over the coming 50 or 60 years, reaching a peak of around 10.3 billion people in the mid-2080s, up from 8.2 billion in 2024, which will intensify pressure on resources and food systems. This rising demand, coupled with factors like climate change and urbanization, requires a global shift towards sustainable food production to meet the needs of a population potentially reaching nearly 10 billion by 2050 [2]. To meet the increasing food needs of a rising global population, various alternative protein sources have emerged as potential replacements for traditional meat proteins. These include plant-based meats [3], lab-grown or cultured meats [4], protein derived from microorganisms [5], and edible insects [1].

Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 of the European Parliament and of the Council includes whole insects and their parts within the definition of ‘novel food’ [6]. Likewise, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) also published a scientific opinion on their consumption, identifying several species with high potential for use as food for both humans and animals [7]. In the field of food technology, this emerging resource has gained prominence, driving new research and the development of innovative products, either in hybrid formulations or in those in which insect powders are used to enrich the nutritional profile or partially replace ingredients in similar products. Nutritionally, edible insects are a food source of high nutritional value, characterized by their significant contribution of protein as the main component, fat, vitamins, fiber, and minerals, respectively [8]. However, their nutritional composition can be subject to considerable variations depending on the insect species, stage of development, type of diet, geographical area of origin, and analytical methods used [9].

Among all edible insects, the house cricket (Acheta domesticus) has emerged as one of the most promising alternatives for the food industry due to its high protein content (60–70% on a dry-weight basis) and substantial contribution of unsaturated fatty acids, particularly polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) such as omega-6, which predominate over omega-3 [10]. In addition, cricket powder is rich in linoleic (C18:2) and oleic (C18:1) fatty acids. It also provides a significant amount of total dietary fiber [6], micronutrients and essential amino acids, such as iron, zinc, calcium, biotin, riboflavin and pantothenic acid [11,12,13]. In addition, its cultivation is highly efficient in terms of feed conversion and requires less water, land, and energy compared to conventional livestock farming, which reinforces its value as a sustainable ingredient [8,13,14].

To minimize consumer aversion to eating insects (entomophobia) while retaining their nutritional benefits, they can be integrated into various food products-such as meat products or analogues, in the form of finely ground powder, making their presence less apparent. Therefore, products such as patties are an ideal food matrix for evaluating the impact of cricket powder on nutritional, physical–chemical, and sensory properties, as well as for exploring its acceptance by consumers. This field of research presents benefits and challenges. However, it has been shown that adding cricket powder to meat products, either as a substitute for animal proteins or as an enrichment, provides various technological benefits, as it improves gelation and emulsification capacity [15].

The synergy of its nutritional and technological benefits, together with the intrinsic sustainability of its production, improves the development of meat products with a healthier profile and a lower environmental impact than their traditional equivalents. In this context, the present study aims to evaluate the technological, physico-chemical, and sensory feasibility of incorporating common cricket powder (Acheta domesticus) into the reformulation of patties. The objective is to determine its potential as a fortifying ingredient in a meat product widely accepted by consumers, assessing its impact on nutritional composition, technological properties, and organoleptic characteristics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

Acheta domesticus powder (ADP: A. domesticus dried and milled) was supplied by Origen Farms, S.L. (Albacete, Spain), an authorized supplier of edible insects. According to the nutritional label, the ADP contains 69.41% protein, 19.49% fat, 9.36% carbohydrates, and 6.09% total dietary fiber (TDF). Meat ingredients (pork lean meat and pork backfat) were provided by a local butchery (Orihuela, Spain) and transferred to the food pilot plant at the Institute of Agri-Food and Agri-Environmental Research and Innovation of the Miguel Hernández University (CIAGRO-UMH, Orihuela, Alicante, Spain) and stored in refrigeration until use (4 ± 2 °C). Salt and black pepper were supplied by Rivers S.L.U. (Orihuela, Alicante, Spain).

2.2. Formulation and Manufacturing of Pork Patties with Cricket Powder

Three different batches were produced. Regular formulation containing 70% lean meat and 30% fat meat was used as control (CT). The other two batches were formulated with the replacement of 10% and 20% of lean meat by Acheta domesticus powder (ADP) and were called ADP10% and ADP20%, respectively. The formulation of each batch is shown in Table 1 (only meat ingredients and the insect powder add up to 100%; the amounts of the other non-meat ingredients and spices are related to the total meat content).

Table 1.

Formulation of pork patties [control and with partial lean pork meat replacement (10% and 20%) by Acheta domesticus powder (ADP)].

The patties were prepared in the food pilot plant at the CIAGRO-UMH. ADP, salt, and pepper were weighed for each formulation. Meat raw materials were removed from refrigeration (4 ± 1 °C), weighed individually, and conditioned by adding cold water. This step facilitates protein solubilization and maintains the temperature of the meat, thereby minimizing smearing caused by frictional heating. Salt, cricket powder (excluded in the control batch), and pepper were sequentially incorporated, followed by constant mixing for 5 min until complete homogenization. The homogenized mixture from each batch was divided into 30 ± 2 g portions and shaped into circular patties (7 cm diameter) using a patty former. Patties were placed in individual zip-lock bags, labeled, and stored under refrigeration (4 ± 1 °C) until analysis. The whole process was repeated three times on different days.

For cooked patties analyses, samples were cooked on an electric griddle until reaching an internal temperature > 72 °C, according to the procedure established by the American Meat Science Association [16].

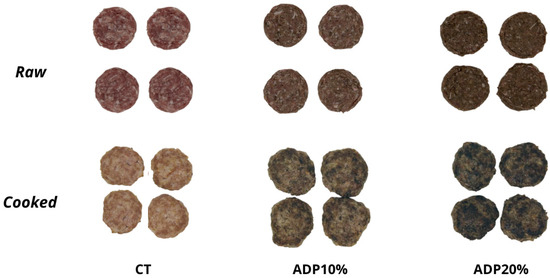

Figure 1 shows the pork patties [control and with partial lean pork meat replacement (10% and 20%) by Acheta domesticus powder (ADP)], both raw and cooked.

Figure 1.

Visual appearance of pork patties (raw and cooked) made with ADP as a partial lean pork meat replacement. CT: control patties with traditional formulation; ADP10%: patties with 10% cricket powder; ADP20%: patties with 20% cricket powder.

2.3. Analysis of Acheta domesticus Powder

2.3.1. Techno-Functional Properties

The techno-functional properties, water-holding capacity (WHC), swelling capacity (SWC), oil-holding capacity (OHC), gelling capacity (GC), emulsion ability (EA), and emulsion stability (ES) were assessed, following the methodology described by Lucas-González et al. [17]. All these measurements were done in triplicate at each sampling (n = 3).

2.3.2. pH

The pH was measured in a water solution (solid: liquid ratio 1:10 g/mL) after 20 min of magnetic stirring with a pH meter (Model 507, Crison Instruments SA, Barcelona, Spain). The instrument was calibrated prior to each measurement series using pH 4.01 and 7.00 standard solutions. The pH measurements were done in triplicate at each sampling (n = 3).

2.3.3. Color Properties

Color was evaluated using a Minolta CM-700 spectrophotocolorimeter (Minolta Camera Co., Osaka, Japan) under the following conditions: 10° observer angle, D65 illuminant, 11 mm illumination aperture, and 8 mm measurement aperture. The instrument was calibrated prior to measurements following the manufacturer’s instructions using a calibration plate (ID 70016895) with white (L*: 99.41 a*: −0.10 b*: −0.07) and black (L*: 0.03 a*: 0.00 b*: −0.03) standards. Color was recorded in the CIELAB space, obtaining lightness (L*), redness (a*), and yellowness (b*) coordinates. From these values, additional color parameters were calculated: chroma or saturation index [C* = (a*2 + b*2)1/2] and hue angle [H* = arctan(b*/a*)] according to Reyes-García et al. [18]. Six measurements for each sample (n = 3) were performed. Furthermore, reflectance spectra were recorded for each sample at 10 nm intervals between 360 and 740 nm.

2.4. Analysis of Pork Patties with Cricket Powder

2.4.1. Proximate Composition

Moisture content was assessed using the oven air-drying method, ash content by muffle furnace incineration, protein content through the Kjeldahl procedure, total dietary fiber content by the enzymatic–gravimetric method, and fat content by Soxhlet extraction, all these according to AOAC Official Methods [19]. Each determination was carried out in triplicate for each sample (n = 3).

2.4.2. Physico-Chemical Properties

Water activity (aw) was measured at 25 °C using a NOVASINA TH200 digital hygrometer (Novasina; Axair Ltd., Pfaeffikon, Switzerland). Each determination was carried out in triplicate for each sample (n = 3).

The pH of the meat patties was directly measured using a puncture electrode (Hach 5233, Hach-Lange S.L.U., Vésenaz, Switzerland) connected to a pH meter with automatic temperature compensation (SensION™ + pH 3, Model 510, Crison Instruments S.A., Barcelona, Spain). The instrument was calibrated prior to each measurement series using pH 4.01 and 7.00 standard solutions. Each determination was carried out in triplicate for each sample (n = 3).

The color of the meat patties was assessed as the same protocol described in Section 2.4.3. Furthermore, additional color parameters were calculated such as color differences [ΔE* = (ΔL*2 + Δa*2 + Δb*2)1/2] with respect to the control patty, and redness index (RI), according to American Meat Science Association guidelines [16].

2.4.3. Texture Properties

Texture Profile Analysis (TPA) of cooked patties was performed using a TA-XT2i texture analyzer (Stable Micro Systems, Godalming, UK). Portions of approx. 2 × 2 × 1 cm were compressed twice to 75% deformation at a constant speed of 1 mm/s at room temperature, and hardness (N), elasticity (mm), cohesiveness, gumminess (g), and chewiness (N × mm) were determined [20]. Each determination was carried out in triplicate for each sample (n = 3).

2.4.4. Cooking Properties

Cooking quality of the patties was assessed through three parameters: cooking loss, which quantifies the loss of liquids during cooking and shrinkage, which evaluates the reduction in diameter after cooking. The formulas for these properties are presented in Equations (1) and (2), respectively [21]. Results are expressed as percentages based on three replicates for each independent sample (n = 3) per treatment. The cooking process was standardized across all formulations: raw patties were cooked for three minutes on each side on a preheated grill until reaching an internal temperature of 72 °C. Samples were then allowed to rest at room temperature for 15 min prior to analysis.

2.4.5. Sensory Analysis

A hedonic sensory test was carried out with 50 untrained panelists (67% male, 33% female), primarily students and some faculty members. The evaluation was conducted at the Sensory Analysis Laboratory of CIAGRO-UMH (Orihuela, Spain), following international standards. This study received approval from the Responsible Research Office at Miguel Hernández University (OIR-Reg. 231129141204, UMH, Elche, Alicante, Spain). Attributes assessed included overall appearance, color, hardness, juiciness, crumbliness, overall flavor, and bitterness, using a 9-point hedonic scale (1 = dislike extremely; 9 = like extremely). Demographic information, consumption frequency, general opinion, and preference for most and least liked samples were also recorded.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and post hoc comparisons were performed using Tukey’s test at a 95% confidence level, employing SPSS software (version 24.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Means and standard deviations are presented in the respective tables and figures.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Properties of Acheta domesticus Powder

3.1.1. Techno-Functional Properties

The techno-functional properties, such as water-holding capacity, oil-holding capacity, swelling capacity, emulsifying ability, gelling capacity, and emulsion stability, are critical indicators for assessing whether a new ingredient can be effectively used in food formulations. The evaluation of these attributes provides valuable insights into the expected behavior of the ingredient within the food matrix and its potential interactions with major structural components such as water, lipids, carbohydrates, and fibers [22,23]. WHC and OHC are related to the ability to take up water and oil, respectively. SWC, in particular, is defined as the ability of ingredients, particularly those containing polysaccharides or fibers, to absorb water and expand in volume until reaching a stable equilibrium [24,25]. This characteristic reflects how fibers interact with water and the material’s porosity, which in turn influences important aspects of the food product such as texture, viscosity, and satiety [26]. On the other hand, GC, EA, and ES are especially important when evaluating insect-based powders, as they indicate the protein’s capacity to create structural networks, stabilize oil–water mixtures, and preserve the integrity of emulsions over time [27].

Table 2 shows the results for the techno-functional properties of ADP. In this case, WHC was higher than OHC. Nevertheless, both of them showed similar values according to other studies for edible insect powders (WHC: 1.8–3.8 g/g; OHC: 1.6–2.2 g/g) [28,29].

Table 2.

Techno-functional properties (water -holding capacity-WHC, swelling capacity-SWC, oil-holding capacity-OHC, gelling capacity-GC, emulsion ability-EA, and emulsion stability-ES) of Acheta domesticus powder (ADP).

Lucas-González et al. [29] evaluated the influence of the drying process on the techno-functional properties of Acheta domesticus powder, comparing freeze-dried and thermally dried samples. Their findings showed that freeze-dried powder exhibited significantly higher values across the evaluated properties compared to thermally treated samples (p < 0.05). While the WHC of the heat-treated powder was similar to the values shown in Table 2, the remaining techno-functional attributes of ADP were notably lower. This variation may stem from several factors, including changes in protein structure [30], differences in surface hydrophobicity or lipophilicity, protein amphiphilic behavior [31], and the specific type of thermal processing used [32]. In particular, the heat-induced unfolding of proteins may expose hydrophobic amino acid residues that are normally hidden, increasing hydrophobic interactions and altering protein performance at the air–water interface [29]. Nevertheless, the results shown in Table 2 are also consistent with those reported by Ndiritu et al. [33], who investigated how extraction methods influence the techno-functional traits of cricket protein concentrate, reporting a slightly lower WHC of 2.03 ± 0.32 g water/g sample. In contrast, the OHC observed in the current study was higher than that reported for thermally dried Acheta domesticus powder by Lucas-González et al. [29], and aligns closely with the results observed by Kim et al. [34]. Furthermore, when compared to other edible insects, the OHC of ADP remains higher than values reported for adult grasshoppers (Zonocerous variegatus) and Westwood larvae powder (Cirina forda) [35].

The swelling capacity observed in this study was lower than the values previously reported by Lucas-González et al. [29], as well as those documented for various processing conditions applied to Acheta domesticus powders, including fresh freeze-dried, partially defatted, blanched–pressed–dried, and non-defatted samples [26]. In agreement with those findings, SWC generally increases following specific processing treatments that enhance both water- and oil-binding capacities, thereby contributing to improve texture and reduce fat loss in different food matrices [24,26,36]. The lower SWC values reported in Table 2, in comparison to samples processed under alternative conditions, may be attributed to the pronounced influence of protein content and structural characteristics, such as the balance between hydrophilic and hydrophobic regions, spatial conformation, and the state of the protein (native vs. denatured) [22,37].

On the other hand, gelation capacity, emulsifying activity, and emulsion stability are key functional properties of insect-derived powders directly linked to textural quality, water and fat retention and, overall technological performance in food systems [38]. In the present study, ADP exhibited a GC of 56.67%, which exceeds values reported for mixed vegetable–insect protein systems [38]. This improved gelation performance can be attributed to the exclusive use of ADP, without dilution from other protein sources. However, previous studies involving insect powders from Gryllodes sigillatus and Tenebrio molitor subjected to high hydrostatic pressure reported no measurable gelation capacity [39]. Nonetheless, other studies reported that applying these types of technologies not only improves the microbiological quality of the product, extending its shelf life [40], but may also improve technological properties, specifically by increasing gelation capacity and reducing syneresis in final products. In terms of emulsifying capacity, ADP reached a value of 66.67%, which is slightly higher than that of freeze-dried cricket powder reported by Lucas-González et al. [29], and notably higher than the values observed for edible cricket protein concentrates by Ndiritu et al. [33] (26.83%), and Kim et al. [34] (39.2-45%). Furthermore, ADP exhibited the highest emulsion stability (77.47%; Table 2) when compared with these previous studies. These differences in the techno-functional properties may be attributed to the specific protein composition of ADP (soluble/insoluble protein) as well as to conformational changes induced by processing, which enhance interfacial activity and network formation [29,31]. Additionally, other components such as carbohydrates may contribute to emulsion stabilization by increasing the viscosity of the system [31]. Thermal treatment may also play a role, as it can expose previously buried amino acid residues, enhancing surface activity and hydrophobic interactions, thereby improving both emulsion formation and stability [32].

3.1.2. pH and Color Properties

Table 3 shows the pH and color properties of ADP. The pH value is particularly noteworthy, as it closely aligns with the typical pH range of meat, which generally falls between 5.8 and 6.1 [41]. The fact that ADP displays a pH similar to that of meat is of particular relevance, as it suggests that its incorporation into the meat matrix is feasible without shifting the isoelectric point of muscle proteins (pI = 4.5) [42]. Additionally, the results obtained are consistent with those observed by Mokaya et al. [43], who found similar pH ranges (5.70-6.88) in protein hydrolysates derived from edible insects, such as caterpillars (Gynanisa maja and Gonimbrasia belina) and crickets (Gryllus bimaculatus), which ranged from 5.70–6.88.

Table 3.

pH and color properties of A. domesticus powder (ADP).

With regard to its colorimetric properties (CIEL*a*b*), particular attention should be given to the low lightness and the hue shift towards orange tones. These characteristics may potentially induce noticeable pigmentation changes when the powder is incorporated into meat matrices [44]. Moreover, the chromatic properties of the powder are significantly influenced by its particle size, which is itself dependent on the processing method applied. Previous studies have demonstrated that the application of thermal treatments leads to a reduction in particle size post-milling. Nonetheless, both freeze-drying and convective drying processes likewise contribute to further particle size diminution [45]. Ando et al. [46] investigated structural variations between hot air–dried and freeze-dried two-spotted crickets (Gryllus bimaculatus), house crickets (Acheta domesticus), and silkworm (Bombyx mori), and their subsequent effects on powder properties after grinding. Their findings revealed that, in the case of cricket powders, the drying method exerted a greater influence on color properties than did particle size, when tested at two levels (2 mm and 0.7 mm). Freeze-dried cricket powders, including those from Acheta domesticus, exhibited superior color quality, characterized by higher L* and b* values and lower a* values, resulting in more orange-like hues [47]. These enhancements in color parameters were particularly evident in powders ground to finer particle sizes (0.7 mm). This effect has been attributed to the presence of fibrous tissues in crickets, which, through Van der Waals interactions during grinding, facilitate the formation of finer particles and increase the total surface area available for light reflection, thereby influencing visual appearance.

3.2. Characterization of Pork Patties with Cricket Powder

3.2.1. Proximate Composition of Patties

Table 4 shows the proximate composition of cooked patties (control and ADP added). The incorporation of ADP into patties induced significant differences in their proximate composition, with the exception of fat content (p > 0.05). Although the fat content was not modified by the addition of ADP, it could be expected that its lipid profile was improved. It is true that in this case, the lipid profile of the ADP was not determined, but based on other studies, the lipid profile of A. domesticus shows more unsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids than saturated [48,49].

Table 4.

Proximate composition of cooked patties (control and ADP added).

Specifically, in a recent study of our research group about the characterization of several insect powders, common cricket powder (Acheta domesticus) was highlighted by its lipid profile in which polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) predominated over monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), with linoleic acid (C18:2) and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) representing more than 95% of the PUFA fraction, and oleic acid (C18:1 cis) accounting for over 90% of the MUFA fraction.

The addition of ADP at inclusion levels of 10% (ADP10%) and 20% (ADP20%) resulted in a statistically significant increase in protein content (p < 0.05) relative to the control formulation. This increase can be directly attributed to the high protein concentration of the powder itself (69.41 g protein per 100 g of product). However, the total protein content of ADP10% and ADP20% remained relatively similar. Although the proportion of ADP increased by 10% between these formulations (Table 1), the proportion of lean meat simultaneously decreased, thereby partially replacing animal-derived protein with protein of alternative origin.

The development of hybrid meat products is typically achieved by incorporating proteins from plant-based or other alternative sources. However, the inclusion of plant-based raw materials in general resulted in substantially lower protein values than the inclusion of insect-derived raw materials [50]. Carvalheiro et al. [51] developed a Frankfurt-type sausage incorporating relatively low inclusion levels of cricket powder (2.5%, 5%, and 7.5%). The total protein content in these formulations reached up to 17.8. The patties analyzed in the current study exhibited higher protein levels, as protein content was directly proportional to the proportion of ADP incorporated. Accordingly, formulations containing 10% and 20% ADP yielded protein values close to 20% (Table 4). By contrast, the control formulation (without ADP added) displayed a protein content of approximately 18%, derived exclusively from pork meat. These results are consistent with previous findings, where protein enrichment was shown to be directly proportional to the proportion of lean meat replaced [34]. Accordingly, higher substitution levels led to increased overall protein concentrations. Notably, the ADP20% formulation reported here demonstrated higher protein levels than those previously described by both Carvalheiro et al. [51] and Kim et al. [34], attributable to the 20% replacement of lean meat with ADP. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that variability in protein content may arise due to factors such as insect species, developmental stage (larva or adult), climatic conditions, and geographic origin [52], all of which influence the protein composition of the reformulated products.

Regarding moisture content, significant differences (p < 0.5) were observed between patties containing ADP and the control formulation. During processing, the baseline water addition was set at 7.5% (Table 1)—slightly higher than the 5% typically used in patties—to facilitate the integration of ADP into the meat matrix (Figure 1). This adjustment was also applied to the control samples to avoid the introduction of confounding variables. The reduced final moisture content in ADP-containing patties is attributable to the substitution of lean meat, which has a naturally high-water content.

With respect to ash content, significant differences (p < 0.05) were detected across all formulations, directly influenced by the proportion of powder incorporated and the amount of lean meat replaced. Higher inclusion levels of ADP yielded progressively greater ash contents, with the highest values corresponding to the ADP20% samples. Similar increases were reported by Carvalheiro et al. [51], who attributed this trend to the intrinsic mineral fraction of the powder. In contrast, Kim et al. [34] reported ash contents of approximately 2% when 10% of lean meat was substituted with cricket powder. Their findings further indicated that ash content reached its highest level (5%) when both lean meat and fat were simultaneously replaced, underscoring the significant impact of the substitution strategy on the mineral profile of meat-based products.

Regarding total dietary fiber (TDF), statistically significant differences were observed between the formulations (p < 0.05), with patties containing 20% Acheta domesticus powder (ADP20%) exhibiting higher TDF levels compared to those formulated with 10% ADP (ADP10%). As can be observed in Section 2.1, ADP contains 6.09 g of fiber per 100 g, a value that exceeds that of other edible insect powders such as Tenebrio molitor (5.1 g/100 g), which has previously been utilized to enhance the fiber content of bakery products [53]. The addition of ADP into patties led to a concentration-dependent increase in TDF, a notable outcome considering that conventional patties (CT) contain no dietary fiber. Although the inclusion levels used in this study were insufficient to meet the regulatory thresholds required to label the patties as a “source of fiber” or “high in fiber” [54], the enrichment with ADP still contributes meaningfully to dietary fiber intake, potentially improving the overall nutritional quality of the product.

3.2.2. Physico-Chemical Properties of Patties

Table 5 shows the physico-chemical properties of both raw and cooked patties. Significant differences in pH (p < 0.05) were observed only in CT of both raw and cooked patties. No significant differences (p > 0.05) were detected among the patties supplemented with ADP. However, when compared to the control, the ADP-added samples consistently exhibited lower pH values. These findings align with those reported by Kim et al. [34], who evaluated the impact of cricket powder addition in sausages. As shown in Table 5, the partial replacement of lean meat with ADP resulted in only minor pH variations in both raw and cooked patties. This outcome can be attributed to the comparable pH values of commercial cricket powders (5.99 ± 0.01; Table 3) [43] and meat [41].

Table 5.

Physico-chemical properties of patties (raw and cooked).

Water activity (Aw) was measured exclusively in raw patties, as it is a key parameter associated with microbial stability and shelf life. No significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed across formulations, indicating that the replacement of lean meat with ADP did not substantially affect this property. In any case, further studies to evaluate whether the addition of ADP would affect the shelf-life of the patties should be addressed.

With respect to colorimetric parameters, significant differences were observed in all of them, in both raw and cooked patties, as a result of ADP addition. For the lightness value (L*), the control patties exhibited higher values compared to those containing ADP, regardless of cooking status. This indicates that ADP incorporation contributes to a darker appearance in the final product.

No significant differences were observed between the ADP10% and ADP20% formulations, indicating that L* was not influenced by the percentage of powder incorporated. For the red-green coordinate (a*), raw patties did not differ significantly among formulations. However, in cooked patties, significant differences were observed between the control and the powder-added samples (ADP10% and ADP20%). Specifically, cooked patties containing ADP exhibited lower a* values than the control, whereas raw patties showed similar values across all formulations. These findings are consistent with Cavalheiro et al. [51], who reported a reduction in a* values with increasing concentrations of cricket powder in Frankfurt sausages. Regarding the yellow-blue coordinate (b*), all formulations differed significantly from one another, in both raw and cooked samples. Incorporation of ADP consistently decreased b* values, with a more pronounced reduction corresponding to increasing powder inclusion levels (p < 0.05). These trends in L* and b* correlates with the total color differences (Table 5) relative to the control sample. Cooked patties exhibited greater overall color differences than raw patties. Color changes in meat products due to cooking are commonly associated with protein denaturation, Maillard reactions, and other thermal-induced modifications. These effects appear to be more pronounced in samples containing cricket powder, likely due to the additional contribution of Strecker degradation during thermal processing. Both Maillard reactions and Strecker degradation generate dark-colored compounds [55], particularly in the final phase of Maillard chemistry, where advanced glycation end products undergo polymerization into high-molecular-weight melanoidins—compounds largely responsible for the post-cooking darkening observed in ADP-enriched patties [56,57]. Chroma (C*) values for both raw and cooked patties followed trends similar to those of the b* coordinate, decreasing with the incorporation of ADP. This reduction was concentration-dependent, with higher ADP levels producing lower C* values. Previous studies have reported similar effects in meat products, where the addition of non-meat ingredients leads to a decrease in color saturation [58]. Hue angle (H*) was also affected by ADP addition. In raw patties, the hue shifted from yellow-orange to red-orange tones, while in cooked patties, red-orange hues were predominant [47]. The redness index (RI) showed statistically significant differences only in the ADP20% formulation, which contained the highest proportion of cricket powder (ADP) and showed the most intense red coloration compared with the control and ADP10% samples.

These results for lightness and total color differences (∆E*) of ADP10% and ADP20% are consistent with findings from Han et al. [59], who studied hybrid sausages formulated with varying levels (1%, 2.5%, and 5%) of cricket powder. Their study reported progressive reductions in both L* and ∆E* values with increasing insect powder concentration, resulting in darker products compared to the control. Such color changes can be attributed to the intrinsic pigmentation of edible insects like Acheta domesticus, which predominantly exhibit dark brown, black, or yellow tones depending on the species. These hues are mainly associated with cuticular proteins containing melanin [60]. Additionally, differences in endogenous pigment composition, such as carotenoids (responsible for red, orange, and yellow hues) and melanin (linked to brown and black coloration), further influence product color. While chitin is not a pigment, its presence may contribute to visual darkening effects [61]. Consequently, even at relatively low levels, insect powder can markedly alter the visual appearance of meat emulsions. These findings underscore the importance of considering color attributes during the formulation of insect-enriched meat products, especially in the context of consumer acceptance.

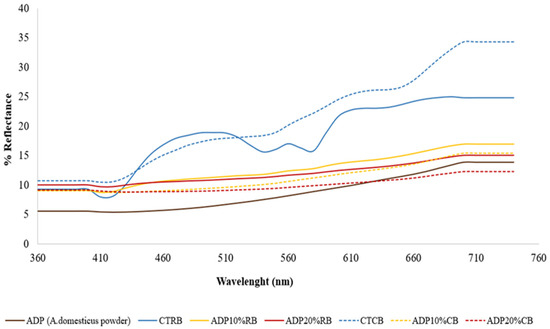

Figure 2 shows the reflectance spectrum of ADP and the formulated patties in both raw and cooked states. The results clearly demonstrate how the incorporation of ADP alters the characteristic meat spectrum observed in the raw control patty, which is primarily associated with the oxymyoglobin spectrum [62]. With ADP addition, the spectral profile increasingly resembles that of ADP itself. Even the spectral changes induced by cooking (such as those observed in the cooked control patty spectrum) are largely masked by the presence of ADP. This masking effect is commonly observed when non-meat ingredients are incorporated into meat products. For instance, the addition of paprika to sausages such as “chorizo” or “sobrasada” similarly modifies the final product’s reflectance spectrum, making it more similar to that of the paprika, rather than of the original meat matrix [63]. These findings underscore the importance of reflectance spectroscopy as a tool for evaluating the visual and compositional changes that occur in meat products due to ingredient substitution. In particular, spectral regions between 520–580 nm and in the red zone (above 650 nm) are highly responsive to thermal processing and formulation changes, as also noted in previous studies on various meat systems [15]. Beyond simple reflectance analysis, spectroscopic techniques have proven effective for detecting the inclusion of insect-derived ingredients in complex food matrices. Differences in absorbance at specific wavelengths can indicate the presence of insect protein, highlighting the potential of such techniques for monitoring formulation changes and supporting quality control in meat-based products containing alternative proteins [64].

Figure 2.

Reflectance spectrum of cricket (A. domesticus) powder (ADP), and patties (raw and cooked). CTRB: control raw patties; ADP10%RB: raw patties with 10% ADP; ADP20%RB: raw patties with 20% ADP; CTBC: cooked control patties; ADP10%CB: cooked patties with 10% ADP; ADP20%CB: cooked patties with 20% ADP.

3.2.3. Texture Profile (TPA) of Patties

Table 6 shows the results obtained for the textural properties in cooked patties (control and with ADP added).

Table 6.

Texture profile (TPA) of cooked patties (control and with cricket powder added).

Regarding hardness, gumminess, and chewiness, no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) were detected among the different formulations. However, the ADP20% formulation exhibited the highest values for hardness, and chewiness, although these differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). This trend can be attributed to the higher proportion of cricket powder incorporated, which increased the solid content of the mixture and, after cooking, resulted in a firmer (harder) texture. Consequently, ADP20% samples required greater chewing effort compared to the control and ADP10% formulations, which contained lower amounts of cricket powder and were therefore easier to disintegrate. According to the texture data, it could be said that the ADP addition did not affect the structural characteristics of the meat product, as a result of the lipid–protein interaction [51]. The results for hardness, gumminess and chewiness were consistent; for food, hardness directly affects both the energy needed to break it down to a suitable swallowing texture (gumminess) and the time require to chew it to the ideal consistency for swallowing (chewiness) [65]. These results are partially consistent with those reported by Kim et al. [34], who evaluated the effect of adding cricket powder (Acheta domesticus) on the physico-chemical and textural properties of meat emulsions. Only for the chewiness, our values (Table 6) were lower than those described in their study. It should be noted, however, that in Kim et al.’s research [34], chewiness increased when both lean meat and fat were simultaneously replaced in equivalent proportions, which may explain the discrepancy with the present findings, where only lean meat was partially substituted. On the other hand, Borges et al. [53] elaborated hybrid patties with Gryllus assimillis powder (CT, F10%, F15%, F20%), and they reported that no significant differences in hardness were found among the hybrid formulations (p > 0.05). However, control samples showed hardness values significantly higher (p < 0.05) than hybrid patties. According to the research of Borges et al. [53], the values obtained for hardness suggested that the higher proportion of muscle tissue in the control favors a more compact and firm structure, whereas the incorporation of cricket powder, by partially altering the meat protein network, tends to reduce the rigidity of the product without producing notable differences among the different substitution levels. The softer texture often observed in hybrid products was associated with the crumbly structure characteristic of this type of formulation, particularly evident in patties with 15% and 20% substitution [53]. In meat emulsions, the addition of cricket powder can exert a divergent effect compared with our results, since some studies have shown harder products with increasing levels of insect incorporation [34,51]. Nevertheless, processing conditions, especially thermal treatment temperatures, play a decisive role in shaping textural properties. In this regard, Scholliers et al. [66] reported that higher cooking temperatures resulted in hybrid systems with weaker textural characteristics, highlighting that cooking methods (e.g., steam oven or grilling) can substantially modify the final hardness of hybrid patties [53].

Additionally, although the ADP20% formulation contained the highest proportion of cricket powder and therefore the greatest solid content, the manufacturing process of patties made with ADP required the addition of 7.5% water (in the form of ice) to facilitate the incorporation of the powder and the solubilization of proteins. As a result, even though the cooked samples became firmer, the higher water addition prevented chewiness from being excessively affected.

The addition of ADP reduced the cohesiveness of the patties (p < 0.05), independently of the amount of ADP added. Meat fibers are notably reduced in size in these type of meat products, generating cohesive interactions between meat fibers and non-meat ingredients contribute to the final texture. Cohesiveness represents the degree to which the food is compressed between the teeth before breaking, and a lot of studies have reported that the addition of non-meat ingredients is one of the factors that significantly reduces its value [65]. For example, Kim et al. [34] reported that higher substitution levels of lean meat by cricket powder resulted in decreased cohesiveness, with the control samples exhibiting the highest values. However, these findings do not fully align with those of Acosta-Estrada et al. [67], who reported that the addition of insect powder tends to increase cohesiveness and chewiness. Nevertheless, when comparing only the cricket powder formulations, no significant differences in cohesiveness were found.

Regarding elasticity, formulations containing 10% ADP showed significantly higher values compared with both the control and ADP20% samples. The incorporation of insect powder appears to enhance this attribute in alternative meat products, as previously reported by Acosta-Estrada et al. [67]. This effect could be attributed to the improvement in WHC, since ADP contributes to a greater retention of water within the protein matrix. Furthermore, the differences in textural behavior align with the role of WHC and OHC, which are considered key protein-related properties for enhancing structure but also for improving the overall quality of the product, due to their ability to bind both water and fat [68,69]. As the TPA was carried out on cooked samples, this property is also related to the water and fat retention after cooking.

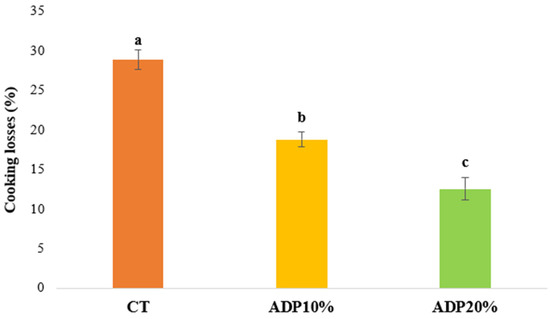

3.2.4. Cooking Properties of Patties

Figure 3 and Figure 4 show the cooking losses and size variations (shrinkage), respectively, of the patties after cooking. The incorporation of ADP significantly reduced cooking losses, with the magnitude of the reduction being dependent on the concentration of ADP added. These losses are primarily attributed to the release of water and fat during heating, resulting from protein denaturation and the melting of lipids present in the patties [70].

Figure 3.

Cooking losses of patties (control and with cricked powder added). For each parameter, results followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey’s post hoc HSD test (p > 0.05). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). CT: control patties with traditional formulation; ADP10%: patties with 10% cricket powder; ADP20%: patties with 20% cricket powder.

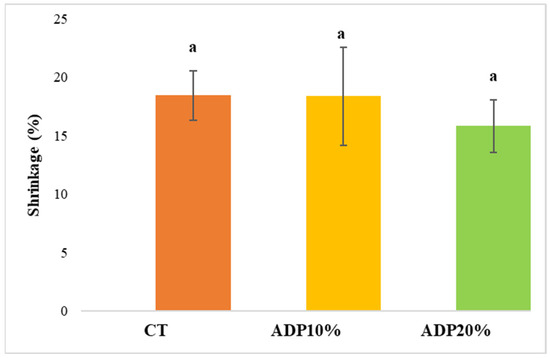

Figure 4.

Shrinkage of patties (control and with cricked powder added). For each parameter, results followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey’s post hoc HSD test (p > 0.05). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). CT: control patties with traditional formulation; ADP10%: patties with 10% cricket powder; ADP20%: patties with 20% cricket powder.

In this study, the moisture content of the samples after cooking was determined, yielding values of 58.67%, 55.37%, and 52.86% for the control, ADP10%, and ADP20%, respectively. A significant reduction (p < 0.05) in moisture content was observed with the incorporation of ADP. When comparing moisture content between raw and cooked samples, the decrease was approximately 19% for control and ADP10%, whereas ADP20% exhibited a slightly higher loss, around 21% (p < 0.05).

Regarding fat content, an increase was observed after cooking, which can be attributed to the aforementioned water losses. This increase was approximately 6% for the control and ADP20% samples, and 8% for ADP10%, reaching at the end a similar fat content in all samples (p > 0.05; Table 4)

A progressive reduction in cooking losses with increasing levels of ADP can be observed in Figure 3, suggesting that this ingredient could be primarily responsible for the observed effect. The water- and oil-holding capacity of ADP helps retain these components within the meat matrix, thereby minimizing their loss during cooking. This aspect is particularly relevant in meat products, as reduced cooking losses directly contribute to higher product yield. In line with this, Borges et al. [53] also evaluated the cooking losses and shrinkage induced by Gryllus assimilis powder in hybrid patties. Their results similarly showed a progressive reduction as the level of powder increased, with the 15% inclusion proving to be the most effective concentration for both parameters evaluated. The beneficial effects observed in these technological properties of beef patties, especially moisture retention, shrinkage, and cooking loss, may be attributed to the high solubility and strong binding capacity of cricket powder, as well as to the functional interactions established between insect and meat proteins, which can also influence shrinkage behavior [53]. Kim et al. [34] reported that the solubility of cricket proteins increases at a pH of approximately 6.8 and in the presence of NaCl concentrations up to 1.75 M. Furthermore, Santiago et al. [71] demonstrated that thermal treatment under saline conditions reduced the α-helix content and surface hydrophobicity of black cricket proteins. According to the authors, the combined effects of salt and heat, together with the increased protein solubility, may help explain the mechanisms underlying the higher water retention observed in meat matrices containing insect powder. Recently, Alburquerque et al. [72] also evaluated the effects of adding cricket powder (Gryllus assimilis) and soy protein to beef patties. Regarding cooking losses, their results are consistent with our results, because they also reported that cooking losses were significantly lower (p > 0.05) in beef patties with the highest addition of cricket powder. These authors reported that the low cooking losses in patties with cricket powder could be related to their pHs values. High pH values (pH = 6.03) influence the degree of repulsion between protein molecules, affecting the water inside the matrix and consequently, the cooking loss because of the isoelectric point of insect powders (pH = 4) according to Kim et al. [34]. So, when the matrix has a basic pH, the repulsion between proteins tends to be higher, increasing their interactions with water molecules and decreasing cooking losses depending on the concentration added to the meat matrix [69]. The same trend was observed by Choi et al. [73]. In their study, adding silkworm pupae (B. mori) and transglutaminase in meat batters showed lower cooking loss values than in the control group, due to the ability of insect protein to hold more water. Also, its moisture content influenced this parameter, suggesting that proteins from insects have higher hydrophilicity than meat protein, holding more water and lowering cooking losses. In industrial settings, similar effects are often achieved using additives such as sodium caseinate or starch to stabilize the meat emulsion and decrease cooking losses [15].

Regarding size variations in food products, these are typically associated with the contraction of muscle fibers during thermal treatment, generally resulting in a reduction in diameter and an increase in thickness [34,44]. In this research, no significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed in shrinkage among the different formulations, indicating that the incorporation of ADP does not negatively impact the dimensional changes of the patties during the cooking process.

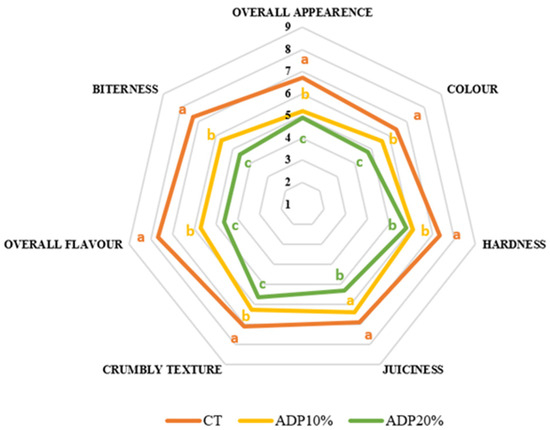

3.2.5. Sensory Analysis

Figure 5 shows the results of the sensory analysis in control patties and patties with added ADP. In general, the incorporation of ADP led to a reduction in the scores assigned to all sensory attributes: the higher the concentration of ADP added, the greater the reduction in the score (p < 0.05). Only juiciness received comparable scores (p > 0.05) between the control formulation (CT) and ADP10%, and hardness between both ADP-added patties (ADP10% and ADP20%).

Figure 5.

Overall acceptability of patties. The vertical axis represents a 9-point scale (1 = Extremely Dislike, 9 = Extremely Like). For each attribute, results followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey’s post hoc HSD test (p > 0.05). CT: control patties with traditional formulation; ADP10%: patties with 10% cricket powder; ADP20%: patties with 20% cricket powder.

Appearance-related attributes, particularly color and overall aspect, were influenced by the addition of ADP. These findings are consistent with the instrumental color analysis (Table 5), where significant differences in all color parameters among control and ADP-added patties were also detected. Regarding textural attributes such as hardness, juiciness, and crumbliness, the control sample once again received the highest scores; only in the case of juiciness, control samples received the same score as ADP10%. Hardness and crumbliness are closely related parameters, as increasing the proportion of cricket powder also raises the solid content of the reformulated patties. This results in a firmer structure, which simultaneously makes it more difficult to break the product into smaller pieces. The TPA analysis reported higher hardness values when ADP was added (Table 6), although these were not statistically significant. Regarding juiciness, the higher scores obtained for the control and ADP10% samples can be attributed to the excellent water-holding capacity and, to a lesser extent, the oil-holding capacity of ADP. These properties improve the retention of bound water within the matrix. Consequently, such techno-functional characteristics provide the foundation for the reformulation of novel meat products incorporating insect powders [53]. With respect to flavor-related attributes, including overall flavor and bitterness, the patties formulated with ADP were rated less favorably than the control samples, with ADP20% samples receiving the lowest scores.

Similar to meat proteins, insect proteins exhibit comparable behavior in terms of texture and flavor once the reformulated patties are cooked [74]. However, bitterness and overall flavor were the least favored attributes in the ADP10% and ADP20% formulations. Therefore, to enhance consumer acceptance of the final product, it is advisable to implement strategies aimed at improving the sensory profile by incorporating traditional ingredients that can reinforce the characteristic taste and aroma while mitigating the bitter notes associated with the addition of ADP, particularly noticeable in the ADP20% formulation [75].

Although research on the use of edible insects in the development of novel products still requires further exploration, some studies provide justification for the occasionally contradictory results reported so far. The variability largely depends on the specific insect species employed [76]; however, Borges et al. [53] also reported that textural properties can be influenced by the manner in which the insect powder is incorporated into the meat product (e.g., defatted or hydrolyzed), which in turn affects the overall composition of the hybrid product and the functionality of insect proteins [66].

An alternative strategy to enhance sensory quality and consumer acceptance would be to reduce the proportion of cricket powder (ADP) incorporated into the formulations. Likewise, another experimental study using a maximum inclusion level of 6% reported beneficial effects on both texture and appearance. The improvement in texture was attributed to the higher amount of bound water, which contributed to reducing product hardness, while the visual attributes improved due to the lower concentration of cuticular melanin proteins [77] and endogenous pigments associated with darker hues [61], resulting in patties with a lighter and more appealing appearance.

Flavor and aroma are key determinants in the development and consumer acceptance of novel food products. Edible insects have been reported to impart sensory notes ranging from fish-like to bread-like flavors [10]. Species such as Tenebrio molitor, Locusta migratoria and Gryllus assimilis generally exhibit a rather neutral taste. Nevertheless, sensory attributes related to odor and flavor have been associated with nut-like profiles (e.g., walnuts, almonds), as well as with meat and dairy products, although each edible insect species displays its own distinctive aromatic profile [78]. Additionally, Maillard reactions are responsible for the characteristic flavor generated during the cooking of meat due to the fact that the aromatic profile is modified by this processing, affecting the aromatic compounds naturally present in food [57]. Maillard reactions occur as an effect of heat treatment, producing sensory active compounds such as furanones, pyranones, furfural oxygen compounds, nitrogen compounds, and sulphur compounds, which can either have a negative or positive impact on quality attributes, such as odor [79,80]. For example, Acheta domesticus and Gryllus assimilis have a lower content of volatile compounds when they are blanched than when they are treated by a drying process, according to [55]. Meanwhile, other researchers observed an increase in volatile compounds such as hexanal and 2-pentylfuran in Ruspolia differens after blanching [57]. The flavor perceived by consumers is influenced not only by the insect species under study but also by its developmental stage and the thermal processing applied. In this regard, a wide range of sensory notes has been described, including umami, sweet, fruity, bitter, fatty, herbaceous, and buttery notes, largely attributed to active odorants such as 2- and 3-methylbutanal, diacetyl, and/or ocimene [74]. Furthermore, processing methods have a marked effect: steaming or blanching tend to enhance herbaceous and nutty aromas, whereas dry-heating methods promote more meaty notes reminiscent of bacon or mushrooms, mainly due to Maillard reactions [74,81].

4. Conclusions

Acheta domesticus powder demonstrates considerable potential as a functional ingredient due to its protein content and favorable techno-functional properties, particularly water-holding capacity, oil-holding capacity, emulsifying ability, and emulsion stability. These characteristics support its application in the reformulation of products such as patties, with the purpose of reducing pork meat content and generating more sustainable hybrid food alternatives. Its incorporation reduced cooking losses and enhanced the overall protein content of the product. However, the addition of Acheta domesticus powder also induced significant changes in color and sensory attributes, which negatively affected consumer acceptance, particularly at higher inclusion levels (20%). Therefore, the successful development of insect-enriched hybrid products should focus on strategies to minimize or mask these sensory modifications. This could be achieved through the use of complementary ingredients such as spices or natural colorants or by applying targeted processing treatments to the insect powder itself to reduce its sensory impact.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F.-L. and R.L.-G.; methodology, J.R.-P. and C.M.B.-M.; validation, M.V.-M., J.Á.P.-Á. and E.M.S.; formal analysis, J.R.-P. and C.M.B.-M.; investigation, J.R.-P., R.L.-G., J.F.-L. and M.V.-M.; resources, J.Á.P.-Á. and M.V.-M.; data curation, J.Á.P.-Á. and R.L.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.R.-P.; writing—review and editing, R.L.-G. and J.F.-L.; visualization, J.Á.P.-Á. and E.M.S.; supervision, J.F.-L. and R.L.-G.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the UMH Research Project “Insects as new ingredients in processed foods”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research was carried out following the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received prior approval from the Responsible Research Office at Miguel Hernández University (OIR-Reg. 231129141204, UMH, Elche, Alicante, Spain).

Informed Consent Statement

Before starting the sensory analyses, all participants were informed about the unique characteristics of the product they would be tasting, as well as the details of the analysis. They also provided their written informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work was (partially) supported by Programa Iberoamericano de Ciencia y Tecnología para el Desarrollo (CYTED) (through Red AlProSos 125RT0165).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rodríguez-Párraga, J.; Lucas-González, R.; Viuda-Martos, M.; Muñoz-Bas, C.; Barba, F.J.; Pérez-Alvarez, J.A.; Fernández-López, J. Exploring the Suitability of Tenebrio Molitor Powder (Whole and Defatted by Supercritical CO2) as a Partial Fat Replacement in Bologna-Type Sausages. Meat Sci. 2025, 228, 109890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. World Population Prospects 2024. Summary of Results. UN DESA/POP/2024/TR/NO. 9; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, W.; Pan, Q.; He, J.; Liu, J. Plant-Based Meat: The Influence on Texture by Protein-Polysaccharide Interactions and Processing Techniques. Food Res. Int. 2025, 202, 115673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhsh, A.; Kim, B.; Ishamri, I.; Choi, S.; Li, X.; Li, Q.; Hur, S.J.; Park, S. Cell-Based Meat Safety and Regulatory Approaches: A Comprehensive Review. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2025, 45, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muazzam, A.; Samad, A.; Alam, A.N.; Hwang, Y.-H.; Joo, S.-T. Microbial Proteins: A Green Approach Towards Zero Hunger. Foods 2025, 14, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) of the European Parliamient and of the Council of 25 November 2015 on Novel Foods. 2015. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2015/2283/2021-03-27 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- EFSA Scientific Committee. Opinion on a Risk Profile Related to Production and Consumption of Insects as Food and Feed. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Huis, A. Nutrition and Health of Edible Insects. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2020, 23, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-López, J.; Lucas-González, R.; Viuda-Martos, M.; Sayas-Barberá, E.; Navarro, C.; Haros, C.M.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.A. Chia (Salvia hispanica L.) Products as Ingredients for Reformulating Frankfurters: Effects on Quality Properties and Shelf-Life. Meat Sci. 2019, 156, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Elorduy, J.; Moreno, J.M.P.; Prado, E.E.; Perez, M.A.; Otero, J.L.; de Guevara, O.L. Nutritional Value of Edible Insects from the State of Oaxaca, Mexico. J. Food Compos. Anal. 1997, 10, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravel, A.; Doyen, A. The Use of Edible Insect Proteins in Food: Challenges and Issues Related to Their Functional Properties. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 59, 102272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantzen da Silva Lucas, A.; Menegon de Oliveira, L.; da Rocha, M.; Prentice, C. Edible Insects: An Alternative of Nutritional, Functional and Bioactive Compounds. Food Chem. 2020, 311, 126022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. The Contribution of Insects to Food Security, Livelihoods and the Environment; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013; Volume 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M.-X.; Zhu, C.-X.; Smetana, S.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, H.-B.; Zhang, F.; Du, Y.-Z. Minerals in Edible Insects: Review of Content and Potential for Sustainable Sourcing. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2023, 13, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishyna, M.; Keppler, J.K.; Chen, J. Techno-Functional Properties of Edible Insect Proteins and Effects of Processing. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 56, 101508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Meat Science Association (AMSA). Meat Color Measurement Guidelines; American Meat Science Association: Champaign, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas-González, R.; Viuda-Martos, M.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.Á.; Fernández-López, J. Evaluation of Particle Size Influence on Proximate Composition, Physicochemical, Techno-Functional and Physio-Functional Properties of Flours Obtained from Persimmon (Diospyros kaki Trumb.) Coproducts. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2017, 72, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-García, V.; Botella-Martínez, C.; Juárez-Trujillo, N.; Viuda-Martos, M. Pitahaya (Hylocereus ocamponis) Peel Flour as New Ingredient in the Development of Beef Burgers: Impact on the Quality Parameters. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 2375–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 18th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Gaithersburgs, MD, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Claus, J.R. Methods for the Objective Measurement of Meat Product Texture. Recipr. Meat Conf. Proc. 1995, 48, 96–101. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas-González, R.; Viuda-Martos, M.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.Á.; Chaves-López, C.; Shkembi, B.; Moscaritolo, S.; Fernández-López, J.; Sacchetti, G. Persimmon Flours as Functional Ingredients in Spaghetti: Chemical, Physico-Chemical and Cooking Quality. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2020, 14, 1634–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Marcos, M.C.; Bailina, C.; Viuda-Martos, M.; Pérez-Alvarez, J.A.; Fernández-López, J. Properties of Dietary Fibers from Agroindustrial Coproducts as Source for Fiber-Enriched Foods. Food Bioprocess Tech. 2015, 8, 2400–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Fajardo, M.; Bean, S.R.; Ioerger, B.; Tilley, M.; Dogan, H. Characterization of Commercial Cricket Protein Powder and Impact of Cricket Protein Powder Replacement on Wheat Dough Protein Composition. Cereal Chem. 2023, 100, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisambira, A.; Muyonga, J.H.; Byaruhanga, Y.B.; Tukamuhabwa, P.; Tumwegamire, S.; Grüneberg, W.J. Composition and Functional Properties of Yam Bean (Pachyrhizus Spp.) Seed Flour. Food Nutr. Sci. 2015, 6, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jousse, M.; Jayakumar, J.; Fernández-Arteaga, A.; de Lamo-Castellví, S.; Ferrando, M.; Güell, C. Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) Protein Concentrates as a Sustainable Source to Stabilize O/W Emulsions Produced by a Low-Energy High-Throughput Emulsification Technology. Foods 2021, 10, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karoui, R.; Hentati, F.; Romdhana, H.; Mezdour, S. Physicochemical, Nutritional and Structural Properties of Mealworm Powders Manufactured by Using Different Technological Processes. Food Res. Int. 2025, 214, 116565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, K.N.; Kinsella, J.E. Emulsifying Properties of Proteins: Evaluation of a Turbidimetric Technique. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1978, 26, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brena-Melendez, A.; Garcia-Amezquita, L.E.; Liceaga, A.; Pascacio-Villafán, C.; Tejada-Ortigoza, V. Novel Food Ingredients: Evaluation of Commercial Processing Conditions on Nutritional and Technological Properties of Edible Cricket (Acheta domesticus) and Its Derived Parts. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 92, 103589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas-González, R.; Fernández-López, J.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.A.; Viuda-Martos, M. Effect of Drying Processes in the Chemical, Physico-Chemical, Techno-Functional and Antioxidant Properties of Flours Obtained from House Cricket (Acheta domesticus). Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 1451–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Wang, L.; Wei, F.; Xie, B.; Huang, F.; Huang, W.; Shi, J.; Huang, Q.; Tian, B.; Xue, S. Functional Properties of Protein Isolates, Globulin and Albumin Extracted from Ginkgo Biloba Seeds. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 1458–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, E.; Karaś, M.; Baraniak, B. Comparison of Functional Properties of Edible Insects and Protein Preparations Thereof. LWT 2018, 91, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Murphy, P.A.; Johnson, L.A. Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Soy Protein Substrates Modified by Low Levels of Protease Hydrolysis. J. Food Sci. 2005, 70, C180–C187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiritu, A.K.; Kinyuru, J.N.; Kenji, G.M.; Gichuhi, P.N. Extraction Technique Influences the Physico-Chemical Characteristics and Functional Properties of Edible Crickets (Acheta domesticus) Protein Concentrate. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2017, 11, 2013–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Setyabrata, D.; Lee, Y.; Jones, O.G.; Kim, Y.H.B. Effect of House Cricket (Acheta domesticus) Flour Addition on Physicochemical and Textural Properties of Meat Emulsion Under Various Formulations. J. Food Sci. 2017, 82, 2787–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotoso, O.T. Nutritional Quality, Functional Properties and Anti-Nutrient Compositions of the Larva of Cirina forda (Westwood) (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae). J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2006, 7, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravel, A.; Marciniak, A.; Couture, M.; Doyen, A. Effects of Hexane on Protein Profile, Solubility and Foaming Properties of Defatted Proteins Extracted from Tenebrio Molitor Larvae. Molecules 2021, 26, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, R.S.H.; Nickerson, M.T. Food Proteins: A Review on Their Emulsifying Properties Using a Structure–Function Approach. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 975–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bresciani, A.; Cardone, G.; Jucker, C.; Savoldelli, S.; Marti, A. Technological Performance of Cricket Powder (Acheta domesticus L.) in Wheat-Based Formulations. Insects 2022, 13, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion-Poulin, A.; Laroche, M.; Doyen, A.; Turgeon, S.L. Functionality of Cricket and Mealworm Hydrolysates Generated after Pretreatment of Meals with High Hydrostatic Pressures. Molecules 2020, 25, 5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahein, M.; Albawarshi, Y.; Al-khamaiseh, A.; El-Eswed, B.; Kanaan, O.; Majdalawi, M. Non-Thermal Shelf-Life Extension of Fresh Hummus by High Hydrostatic Pressure and Refrigerated Storage. Discov. Food 2025, 5, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella-Martínez, C.; Viuda-Martos, M.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.A.; Fernández-López, J. Total and Partial Fat Replacement by Gelled Emulsion (Hemp Oil and Buckwheat Flour) and Its Impact on the Chemical, Technological and Sensory Properties of Frankfurters. Foods 2021, 10, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-López, S.O.; Escalona-Buendía, H.B.; Martinez-Arellano, I.; Domínguez-Soberanes, J.; Alvarez-Cisneros, Y.M. Physicochemical and Techno-Functional Characterization of Soluble Proteins Extracted by Ultrasound from the Cricket Acheta domesticus. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokaya, H.O.; Mudalungu, C.M.; Tchouassi, D.P.; Tanga, C.M. Techno-Functional and Antioxidant Properties of Extracted Protein from Edible Insects. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 1130–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, A.; Fernández-López, J.; Zimoch-Korzycka, A. Insect Protein as a Component of Meat Analogue Burger. Foods 2024, 13, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purschke, B.; Brüggen, H.; Scheibelberger, R.; Jäger, H. Effect of Pre-Treatment and Drying Method on Physico-Chemical Properties and Dry Fractionation Behaviour of Mealworm Larvae (Tenebrio molitor L.). Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 244, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Orikasa, T.; Tomita, S. Structural Differences Between Hot Air-Dried and Freeze-Dried Two-Spotted Cricket (Gryllus bimaculatus), House Cricket (Acheta domesticus), and Silkworm (Bombyx mori) Larvae and Their Effect on Powder Properties After Grinding. Food Bioproc. Tech. 2024, 17, 1958–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto de Racionalización y Normalización (IRANOR). Nomenclatura Cromática Española; Instituto de Racionalización y Normalización: Madrid, Spain, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Ayllón-Parra, N.; Castellari, M.; Gou, P.; Ribas-Agustí, A. Cricket Powder (Acheta domesticus) Nutritional and Techno-Functional Properties and Effects of Solid-State Fermentation with Pleurotus ostreatus and Rhizopus oligosporus. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2025, 104, 104066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilco-Romero, G.; Chisaguano-Tonato, A.M.; Herrera-Fontana, M.E.; Chimbo-Gándara, L.F.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Giampieri, F.; Battino, M.; Vernaza, M.G.; Álvarez-Suárez, J.M. House Cricket (Acheta domesticus): A Review Based on Its Nutritional Composition, Quality, and Potential Uses in the Food Industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 142, 104226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtan, N.K.; Makki, H.M.M.; Mohamed, H.A.-M.; Alnemr, T.M.M.; Al-Senaien, W.A.; Al-Ali, S.A.M.; Ahmed, A.R. The Potential of Using Bisr Date Powder as a Novel Ingredient in Beef Burgers: The Effect on Chemical Composition, Cooking Properties, Microbial Analysis, and Organoleptic Properties. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalheiro, C.P.; Ruiz-Capillas, C.; Herrero, A.M.; Pintado, T.; Cruz, T.d.M.P.; da Silva, M.C.A. Cricket (Acheta domesticus) Flour as Meat Replacer in Frankfurters: Nutritional, Technological, Structural, and Sensory Characteristics. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 83, 103245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Barrientos, J.M.; Rodríguez-Miranda, J.; Peña-Marín, E.S.; Chareo-Benítez, B.; Alcántar-Vázquez, J.P.; Ramírez-Rivera, E.d.J.; Aparicio-Saguilán, A.; da Cruz, A.G. Chemical Composition, Thermal Profile and Functional Properties of Grasshopper (Sphenarium purpurascens Ch.), Cockroach (Nauphoeta cinerea) Flours and Their Mixtures. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 5829–5836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, M.M.; da Costa, D.V.; Trombete, F.M.; Câmara, A.K.F.I. Edible Insects as a Sustainable Alternative to Food Products: An Insight into Quality Aspects of Reformulated Bakery and Meat Products. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 46, 100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BOE-A-2009-17652; Real Decreto 1669/2009, de 6 de Noviembre, por el que se Modifica la Norma de Etiquetado Sobre Propiedades Nutritivas de Los Productos Alimenticios. Spain Government: Madrid, Spain, 2009. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2009/11/06/1669 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Khatun, H.; Claes, J.; Smets, R.; De Winne, A.; Akhtaruzzaman, M.; Van Der Borght, M. Characterization of Freeze-Dried, Oven-Dried and Blanched House Crickets (Acheta domesticus) and Jamaican Field Crickets (Gryllus assimilis) by Means of Their Physicochemical Properties and Volatile Compounds. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 1291–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, E.; El Boustany, P.; Faulds, C.B.; Berdagué, J.-L. The Maillard Reaction in Food: An Introduction. In Reference Module in Food Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Silva Barbosa Correia, B.; Drud-Heydary Nielsen, S.; Jorkowski, J.; Arildsen Jakobsen, L.M.; Zacherl, C.; Bertram, H.C. Maillard Reaction Products and Metabolite Profile of Plant-Based Meat Burgers Compared with Traditional Meat Burgers and Cooking-Induced Alterations. Food Chem. 2024, 445, 138705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ospina, J.; Martuscelli, M.; Grande-Tovar, C.D.; Lucas-González, R.; Molina-Hernandez, J.B.; Viuda-Martos, M.; Fernández-López, J.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.Á.; Chaves-López, C. Cacao Pod Husk Flour as an Ingredient for Reformulating Frankfurters: Effects on Quality Properties. Foods 2021, 10, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Li, B.; Puolanne, E.; Heinonen, M. Hybrid Sausages Using Pork and Cricket Flour: Texture and Oxidative Storage Stability. Foods 2023, 12, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittkopp, P.J.; Beldade, P. Development and Evolution of Insect Pigmentation: Genetic Mechanisms and the Potential Consequences of Pleiotropy. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2009, 20, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omuse, E.R.; Tonnang, H.E.Z.; Yusuf, A.A.; Machekano, H.; Egonyu, J.P.; Kimathi, E.; Mohamed, S.F.; Kassie, M.; Subramanian, S.; Onditi, J.; et al. The Global Atlas of Edible Insects: Analysis of Diversity and Commonality Contributing to Food Systems and Sustainability. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández–López, J.; Pérez–Alvarez, J.A.; Aranda–Catalá, V. Effect of Mincing Degree on Colour Properties in Pork Meat. Color Res. Appl. 2000, 25, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-López, J.; Pérez-Alvarez, J.A.; Sayas-Barberá, E.; López-Santoveña, F. Effect of Paprika (Capsicum annum) on Color of Spanish-type Sausages During the Resting Stage. J. Food Sci. 2002, 67, 2410–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagappan, S.; Ma, S.; Nastasi, J.R.; Hoffman, L.C.; Cozzolino, D. Evaluating the Use of Vibrational Spectroscopy to Detect the Level of Adulteration of Cricket Powder in Plant Flours: The Effect of the Matrix. Sensors 2024, 24, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, N.P.d.; Vinhal Borges, Í.G.A.; de Castro, J.S.; Nascimento, C.P.d.; Bitu, L.A.; de Sousa, P.H.M.; da Silva, E.M.C. Enhancing the Quality and Antioxidant Properties of Beef Burgers with Dried Hibiscus sabdariffa L. Leaves: Characterization and Sensory Evaluation. Food Biosci. 2024, 57, 103568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholliers, J.; Steen, L.; Fraeye, I. Partial Replacement of Meat by Superworm (Zophobas morio Larvae) in Cooked Sausages: Effect of Heating Temperature and Insect:Meat Ratio on Structure and Physical Stability. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 66, 102535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Estrada, B.A.; Reyes, A.; Rosell, C.M.; Rodrigo, D.; Ibarra-Herrera, C.C. Benefits and Challenges in the Incorporation of Insects in Food Products. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 687712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannozzi, C.; Foligni, R.; Mozzon, M.; Aquilanti, L.; Cesaro, C.; Isidoro, N.; Osimani, A. Nonthermal Technologies Affecting Techno-Functional Properties of Edible Insect-Derived Proteins, Lipids, and Chitin: A Literature Review. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 88, 103453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.K.; Greis, M.; Lu, J.; Nolden, A.A.; McClements, D.J.; Kinchla, A.J. Functional Performance of Plant Proteins. Foods 2022, 11, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathare, P.B.; Roskilly, A.P. Quality and Energy Evaluation in Meat Cooking. Food Eng. Rev. 2016, 8, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, L.A.; Fadel, O.M.; Tavares, G.M. How Does the Thermal-Aggregation Behavior of Black Cricket Protein Isolate Affect Its Foaming and Gelling Properties? Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 110, 106169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Albuquerque, R.S.; Bernardo, Y.A.d.A.; dos Santos, J.F.; Santos, D.d.S.e.; Monteiro, M.L.G.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Simplex-Centroid Design to Evaluate the Effects of Adding Cricket Flour (Gryllus assimilis) and Soy Protein to Beef Burgers. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e70284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, N.; Park, S.; Park, Y.; Park, G.; Oh, S.; Kim, Y.; Lim, Y.; Jang, S.; Kim, Y.; Ahn, K.-S.; et al. Effects of Edible Insect Powders as Meat Partial Substitute on Physicochemical Properties and Storage Stability of Pork Patties. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2024, 44, 817–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ianiţchi, D.; Pătraşcu, L.; Cercel, F.; Dragomir, N.; Vlad, I.; Maftei, M. The Effect of Protein Derivatives and Starch Addition on Some Quality Characteristics of Beef Emulsions and Gels. Agriculture 2023, 13, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockley, M.; Dossey, A.T. Insects for Human Consumption. In Mass Production of Beneficial Organisms; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 617–652. [Google Scholar]

- Gurdian, C.E.; Torrico, D.D.; Li, B.; Prinyawiwatkul, W. Effects of Tasting and Ingredient Information Statement on Acceptability, Elicited Emotions, and Willingness to Purchase: A Case of Pita Chips Containing Edible Cricket Protein. Foods 2022, 11, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkowiak, K.; Łukasz Kowalczewski, P.; Kubiak, P.; Maria Baranowska, H. Effect ff Cricket Powder Addition on 1h NMR Mobility and Texture of Pork Pâté. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2019, 9, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, N.T.; Franco Olivas, J.; Mäde, D.; Kern, D.; González-Aguilar, D. Descriptive Sensorial Testings of Heat-Treated Edible Insects by Laymen and Experts. Berl. Münch. Tieärztl. Wochenschr. 2019, 132, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Sun, H.; Ma, G.; Zhang, T.; Wang, L.; Pei, H.; Li, X.; Gao, L. Insights into Flavor and Key Influencing Factors of Maillard Reaction Products: A Recent Update. Front Nutr. 2022, 9, 973677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, T.; Xie, J.; Xiao, Q.; Du, W.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Wang, S. Meat Flavor Generation from Different Composition Patterns of Initial Maillard Stage Intermediates Formed in Heated Cysteine-Xylose-Glycine Reaction Systems. Food Chem. 2019, 274, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, A.B.; Evans, J.; Jonas-Levi, A.; Benjamin, O.; Martinez, I.; Dahle, B.; Roos, N.; Lecocq, A.; Foley, K. Standard Methods for Apis Mellifera Brood as Human Food. J. Apic. Res. 2019, 58, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]