Abstract

Porphyra umbilicalis is a red macroalga belonging to the genus Porphyra and the family Bangiaceae. Porphyra umbilicalis distinguishes itself among macroalgae due to its remarkable biochemical composition and nutritional value. It contains a broad spectrum of bioactive compounds, including macronutrients and micronutrients. Among the macronutrients, carbohydrates, proteins, and essential fatty acids are particularly abundant, with protein levels reaching up to 40% dw (dry weight). Its high protein content makes Porphyra umbilicalis a promising alternative and sustainable protein source, particularly for plant-based diets. Its micronutrients, including vitamins (C, E, and B-group), pigments, and mineral components, contribute to antioxidant protection, metabolic regulation, and maintenance of overall nutritional balance. What makes P. umbilicalis particularly distinctive is its content of unique bioactives such as porphyran, phycobiliproteins, and mycosporine-like amino acids. Preliminary evidence from animal and in vitro studies indicates that these unique bioactive compounds contribute to the anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects of P. umbilicalis. However, more systematic research into its chemical composition is needed due to variability related to harvest location, environmental factors, and inconsistencies in the existing literature. Detailed data on the full chemical profile and bioavailability of specific compounds remain limited, underscoring the need for further investigation. Evidence on the health benefits of P. umbilicalis remains limited, as current studies are restricted to preclinical models and have not been validated through human trials, emphasizing the need for rigorous research to clarify its role in functional foods.

1. Introduction

In the face of climate change and population growth, there is an increasing global need to boost food production. Food demand is expected to rise by up to 60% by 2050 [1]. As a result, the demand for alternative and sustainable food sources is steadily increasing worldwide [2,3]. The most common micronutrient deficiencies include iron, iodine, folic acid, vitamin A, and zinc [4,5]. Such deficiencies contribute to intellectual disability, perinatal complications, and increased morbidity and mortality [4]. In this context, P. umbilicalis is particularly relevant, as it provides several of these critical micronutrients, making it a promising candidate to help address widespread nutritional deficiencies and contribute to sustainable food security. Macroalgae are regarded as promising candidates for developing innovative and sustainable food products that can contribute to global nutritional security. The cultivation of P. umbilicalis does not require agricultural land, fresh water, or pesticides, and it has a low impact on terrestrial ecosystems [6]. As low-trophic organisms with rapid growth rates, macroalgae are well-suited for large-scale cultivation. Macroalgae cultivation contributes significantly to oxygen production [7] and aids in carbon sequestration [8]. Their production is considered one of the most sustainable approaches to addressing global food needs, offering nutrient-rich biomass with low caloric content [9].

Macroalgae are multicellular marine organisms that range in length from a few centimeters to tens of meters. They are naturally abundant and widespread, occurring on all the world’s coastlines. It is estimated that there are approximately 16,000 species of macroalgae [10]. Macroalgae are classified into three main pigment-based groups: Chlorophyta (green, 6851 species), Phaeophyta (brown, 2124 species), and Rhodophyta (red, 7276 species) [10,11].

Porphyra umbilicalis is particularly valuable due to its high content of protein compared with some algae (Palmaria palmata and Chondrus crispus) [12] and plants (wheat, white rice, and corn) [6]. It contains protein levels comparable to legumes up to 30% dw, along with high amounts of polysaccharides (up to 50%), mineral components (Na, Ca, Mg, and Fe), and vitamins (C, A, and B-group). While the presence of these bioactive compounds indicates health benefits, including anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects, further studies are needed to confirm these associations [13]. These properties give P. umbilicalis significant potential as a functional food ingredient. Despite the growing interest in this topic, detailed studies on the bioavailability and health effects of its consumption are still lacking.

Recent studies highlight the biosafety advantages of macroalgae, including P. umbilicalis, compared to both microalgae and cyanobacteria. Santos et al. evaluated the potential toxicity of P. umbilicalis and found no evidence of toxin production [14]. This contrasts with cyanobacteria, which synthesize cyanotoxins such as hepatotoxins, cytotoxins, neurotoxins, and inflammatory or irritant toxins. These metabolites exert significant ecological effects and pose major public health risks, particularly due to drinking water contamination caused by bloom-, scum-, and mat-forming cyanobacteria [15]. Furthermore, the literature indicates that macroalgae, including P. umbilicalis, are generally less prone to accumulating heavy metals from the environment compared to microalgae. This is because microalgae, as unicellular organisms with high specific surface area and abundant functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, carboxyl, carbonyl, and amino), have a stronger capacity to bind metal cations, leading to greater sorption potential [16]. The combination of a relatively low tendency to accumulate heavy metals and the absence of toxin production further supports the biosafety profile of P. umbilicalis as a promising source of secondary metabolites for nutritional and pharmaceutical applications.

This review summarizes current knowledge on P. umbilicalis as a potential source of bioactive compounds for functional foods and nutraceuticals. In contrast to previous publications focusing mainly on edible red algae [17,18,19], this paper specifically investigates the chemical profile of P. umbilicalis, with consideration of environmental variables that may influence its composition. Furthermore, unlike other publications [20,21,22] focusing on P. umbilicalis, this paper provides comprehensive information on the potential uses of P. umbilicalis in the food industry and the risks associated with its regular consumption. It further compares its nutritional and bioactive components with those of selected edible plants and macroalgae. Additionally, the review explores the potential associations between its chemical constituents and reported health-promoting effects, an area that remains underexplored in the existing literature.

2. Materials and Methods

During the preparation of this narrative review, scientific articles published after 2015 were retrieved from PubMed and ScienceDirect. Earlier publications were included only in cases where more recent studies were unavailable on a specific topic. The search included the following terms: “Porphyra umbilicalis”, “Porphyra” in combination with the terms “functional foods”, “bioactive compounds”, “chemical composition”, and “protein” appearing in the title, keywords, or abstract. The search for “Porphyra umbilicalis” combined with “functional foods” yielded 345 results; with “bioactive compounds”—265 results; “chemical composition”—475 results; and “protein”—683 results. Similarly, the search using “Porphyra” with “functional foods” returned 2046 results; “bioactive compounds”—1496 results; “chemical composition”—2795 results; and “protein”—3902 results. The most relevant publications were selected for further analysis. The scope of the analysis was as follows:

The analysis focused on nutritional value and potential health benefits of Porphyra umbilicalis or Porphyra spp., due to the limited number of relevant publications.

In total, 92 articles meeting the above criteria were selected for analysis.

3. Characteristics of Porphyra umbilicalis

Porphyra umbilicalis is an intertidal red alga belonging to the class Bangiophyceae. This species is becoming increasingly widespread and popular worldwide.

3.1. Economic Relevance

The economic value of Porphyra spp. is reflected in the estimated $1.3 billion annual market value for the genus. It should be emphasized that this market estimate pertains to the genus Porphyra as a whole, as species-specific economic data for P. umbilicalis are currently unavailable in the literature [23]. Porphyra is known by various names: purple laver (UK, US, Canada), karengo (New Zealand), nori (Japan), kim (Korea), and zicai (China) [24]. In 2019, the global production of Porphyra macroalgae reached approximately 2.98 million wet tons, accounting for 8.6% of total marine algae production [25].

3.2. Morphology

Porphyra umbilicalis has a smooth, single-layered thallus that can grow up to 25 cm in height. The thallus varies in color from deep red to purple. Phycobilins, namely, phycoerythrin and phycocyanin, are responsible for the coloration of the macroalga and mask the presence of other pigments, such as chlorophyll and β-carotene [13,26].

The microbiota of P. umbilicalis varies depending on geographic location, ocean currents, temperature, and water salinity. The most abundant bacterial phyla in the microbiome of P. umbilicalis are Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes [22]. Cyanobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Planctomycetes have also been identified in the microbiome of Porphyra species [22]. Although the magnitude of the impact of each bacterial group on P. umbilicalis is not well characterized, individual species appear to play important roles in algal development and resilience. For example, cyanobacterial pseudocobalamin can be remodeled by Porphyra into functional vitamin B12, and many Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria can degrade algal cell walls [27].

Aydlett et al. [27] demonstrated that geographic location influences the composition of the P. umbilicalis microbiota. Macroalgae were sampled from Schoodic (Maine), Newport (Rhode Island), Minehead (United Kingdom), and Amorosa (Portugal). While the dominant phyla (Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Cyanobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Planctomycetes) were shared across sites, each population harbored distinctive taxa. For instance, Sulfitobacter was detected only on the Minehead holdfast, whereas Zobellia was present in both the Minehead and Newport samples. Tissue type also contributed to microbial variation, with Cyanobacteria being more abundant in the holdfasts than in the blades. Together, these findings indicate that the P. umbilicalis microbiota is jointly shaped by environmental conditions and algal morphology [22,27].

The life cycle of Porphyra species involves a heteromorphic alternation of generations, with a microscopic sporophyte and a macroscopic gametophyte. The gametophyte features a large, leaf-like thallus (the “blade” phase), alternating with a small, filamentous sporophyte (the “conchocelis” phase) [28].

3.3. Cultivation

The structure of P. umbilicalis has important implications for its cultivation and harvesting. Its delicate monolayer is highly sensitive to mechanical damage and environmental fluctuations such as salinity or temperature changes, complicating cultivation and harvesting. In addition, the complex life cycle requires specific culture conditions for efficient reproduction and biomass acquisition [28]. Porphyra has been shown to exhibit increased growth rates at lower temperatures and higher ammonia concentrations. Optimal growth occurs at 10–15 °C, with a photoperiod of at least 12 h and light intensity above 110 μmol photons m−2s−1. Under these conditions, maximum growth rates (>9% per day) can be achieved. Extending the photoperiod and harvesting every 3–4 weeks can help maintain high biomass productivity [29].

However, detailed information on ecological activities such as intertidal adaptation, desiccation tolerance, and roles in coastal ecosystems is currently lacking in the literature, highlighting the need for further research in this area.

4. Chemical Composition

Porphyra umbilicalis, a macroalga of high nutritional value, is a rich source of bioactive components, including proteins, carbohydrates, mineral components, essential fatty acids, vitamins, and phenolic compounds [30,31]. A wide range of environmental and physical factors, such as habitat characteristics, light availability, substrate type, temperature, salinity, humidity, water movement (including tides and currents), and pollution, can significantly influence the chemical composition of macroalgae [32]. Table 1 provides a summary of the chemical composition of P. umbilicalis.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of Porphyra umbilicalis, based on [12,32].

4.1. Protein Content and Amino Acid Profile

Porphyra umbilicalis is characterized by its high protein content, which can account for up to 40% of its dw. This distinguishes it from many other red algal species [12]. Moreover, P. umbilicalis contains significant amounts of essential amino acids (EAAs), particularly leucine, threonine, and valine, which together can constitute up to 50% of its total amino acid content. Amino acids are involved in various physiological processes, including the regulation of food intake, gene expression, post-translational modification, and cell signaling. They also act as precursors for the synthesis of hormones and low-molecular-weight nitrogenous compounds, all of which have biological significance [33]. Therefore, the amino acid profile of P. umbilicalis is important both nutritionally and functionally, especially in assessing dietary protein quality and EAA content [34].

According to Machado et al. [35], P. umbilicalis contains significant levels of leucine, valine, and threonine. Leucine is essential for muscle protein synthesis and plays a key role in maintaining muscle mass; valine contributes to energy production and supports muscle metabolism; and threonine is important for protein balance and for the synthesis of collagen and elastin. These findings are consistent with studies by Fernández-Segovia et al. [36] and Astorga-España et al. [37]. Machado et al. [29] also reported that the most abundant endogenous amino acids are aspartic acid, glutamic acid, and alanine. The main free amino acids (not bound in peptides or proteins) also include glutamic acid (3.15–4.77 mg/g dw), aspartic acid (1.44–3.53 mg/g dw), and alanine (3.70–5.01 mg/g dw). These free amino acids are largely responsible for the characteristic umami flavor of seaweed [35]. Table 2 provides a summary of the total amino acid content of P. umbilicalis.

Table 2.

Total amino acid composition expressed in mg/g dw of Porphyra umbilicalis, based on [29,30,31].

4.1.1. Bioactive Compounds: Mycosporine-like Amino Acids and Photosynthetic Pigments

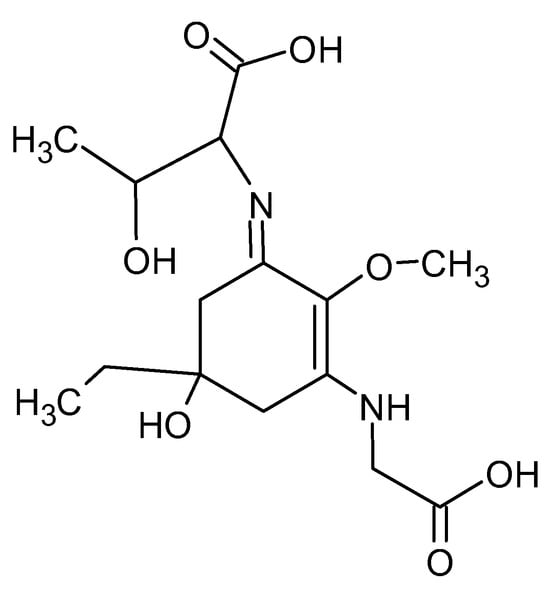

In addition to proteins, macroalgae such as P. umbilicalis contain mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs), including mycosporine and porphyra-334. Mycosporine-like amino acids are water-soluble secondary metabolites with a cyclohexenone or cyclohexenimine chromophore conjugated to an amino acid nitrogen group (Figure 1). These compounds are synthesized by marine organisms exposed to intense sunlight and absorb ultraviolet (UV) radiation in the 310–360 nm range. Their strong UV absorption, high molar extinction coefficients (ε = 28,100–50,000), and photostability in both distilled water and seawater suggest a photoprotective role [38].

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of the porphyra-334-mycosporine-like amino acid, drawn by the authors using ChemSketch based on [39].

Furthermore, porphyra-334 exhibits antioxidant properties. For example, it effectively inhibits linoleic acid oxidation induced by the alkyl radical 2,2′-azobis (2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH) at concentrations up to 200 mM [34]. These findings indicate that porphyra-334 may function not only as a UV filter but also as a stabilizing antioxidant, potentially enhancing the shelf life of P. umbilicalis biomass during storage [39].

Red macroalgae also contain high concentrations of pigment proteins known as phycobiliproteins, including R-phycocyanin, R-phycoerythrin, and allophycocyanin. They play a key role in photosynthetic processes by increasing the efficiency of light capture [21].

In addition to phycobiliproteins, P. umbilicalis contains ferredoxin, a low-molecular-weight iron–sulfur protein (2Fe–2S), which is involved in electron transport during photosynthesis. Although not directly classified as a health-promoting compound, the presence of ferredoxin reflects the high metabolic activity of P. umbilicalis and may suggest its potential as a source of bioavailable non-heme iron [40,41].

4.1.2. Nutritional Value and Digestibility of Algal Proteins

Due to its high protein content, comparable to that of legumes such as soybeans, faba beans, peas, and green beans (20–40% of dry matter), P. umbilicalis may serve as an alternative protein source [42]. This is particularly relevant for individuals adhering to plant-based diets, including vegetarians and vegans. Furthermore, P. umbilicalis contains more protein than many other species of red macroalgae [12]. The protein content of selected algae and legumes per 100 g dw is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of protein content in Porphyra umbilicalis with selected red macroalgae and legumes.

The nutritional value of dietary protein depends not only on its amino acid composition but also on its digestibility and bioavailability. In the case of macroalgae, protein digestibility is influenced by multiple factors, including macronutrient composition, the presence of anti-nutritional compounds, enzyme specificity, and dietary fiber content [44]. Compared to animal proteins, algal proteins exhibit lower digestibility, likely due to their high fiber content, which can hinder enzymatic access to protein substrates [30].

Kazir et al. [45] investigated the digestibility of protein concentrates extracted from Gracilaria (a red macroalga) and reported protein content ranging from 70% to 86%. Simulated gastrointestinal digestion showed that nearly 100% of the Gracilaria protein was hydrolyzed during the intestinal phase, suggesting high bioavailability. In contrast, species with higher soluble fiber content exhibited significantly reduced protein digestibility, ranging from 30% to 89% [45,46].

While these findings are promising, further studies are needed to evaluate the digestibility and bioavailability of proteins derived specifically from P. umbilicalis. Current evidence suggests that P. umbilicalis is a source of high-quality protein, providing a complete profile of essential amino acids in accordance with standards established by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) [35]. Nevertheless, the structural and functional properties of proteins from Porphyra species remain incompletely understood and warrant further investigation [44].

4.2. Carbohydrates

Porphyra umbilicalis is notable for its high carbohydrate content, accounting for up to 50% of its dw, and includes compounds such as carrageenan, cellulose, and porphyran—a polysaccharide unique to this genus [19,47]. Polysaccharides, in particular, are associated with the biological and pharmacological activities of macroalgae [39]. In macroalgae, carbohydrates serve two principal functions: they provide structural integrity to cell walls and act as intracellular energy reserves, supporting metabolic processes and enabling short-term survival in the absence of light [32]. Additionally, polysaccharides play an important role in maintaining homeostasis by modulating immune responses, supporting digestion, and facilitating toxin elimination [23]

4.2.1. Porphyran: Structure and Biological Functions

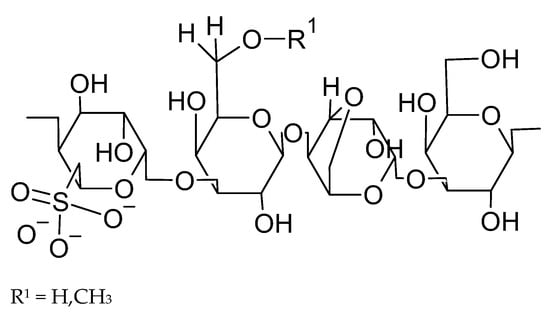

Porphyran is a water-soluble, sulfated polysaccharide composed of repeating units of galactose and 3,6-anhydrogalactose. The chemical structure of porphyran is presented in Figure 2. These monomers are linked by alternating α-1,4 and β-1,3 glycosidic bonds [23].

Figure 2.

Typical structure of porphyran, drawn by the authors using ChemSketch based on [39].

This specific glycosidic linkage pattern supports porphyran’s biological activities, including immunomodulatory and potential anticancer effects, which have been demonstrated in vitro in AGS gastric cancer cell lines, where porphyran induced apoptosis by decreasing IGF-IR phosphorylation and activating caspase-3 [19]. Oligo-porphyran, a degradation product of porphyran formed by the enzyme porphyranase, consists of shorter chains of galactose and 3,6-anhydrogalactose. This oligomer enhances porphyran’s bioactivity in several biological processes, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer mechanisms [19,23]. Recent studies suggest that a higher sulfate content and lower molecular weight enhance porphyran’s efficacy by stimulating nitric oxide production, phagocytic activity, and cell proliferation as demonstrated in vitro in RAW 264.7 macrophages [48]. These properties underscore the essential role of polysaccharides in maintaining physiological homeostasis.

4.2.2. Carrageenan Types and Applications

Carrageenan is a linear, water-soluble polysaccharide consisting of repeating units of partially sulfated disaccharides. It forms cross-linked gels in the presence of K+ or Ca2+ ions, which makes it useful in food and biomedical applications. There are three main types of carrageenan: kappa (κ), iota (ι), and lambda (λ). They differ in the degree of sulfation and molecular weight, which directly influence their functional properties. Kappa-carrageenan (κ) has the strongest gelling capacity and forms firm, brittle gels [47]. Iota-carrageenan (ι) is used to produce softer gels and is appreciated for its freeze–thaw stability. Lambda-carrageenan (λ), which does not form gels, functions mainly as a thickener, giving products a smooth and creamy consistency [49,50]. Carrageenan is widely used in the food industry as a gelling, thickening, and stabilizing agent in dairy, meat, bakery, and plant-based products. Its use improves water retention, product homogeneity, and texture [49].

4.3. Dietary Fiber

Porphyra umbilicalis is rich in dietary fiber, primarily pectin and cellulose, which may constitute up to 48% of its dw [20,32]. When consumed as nori sheets, macroalgae such as P. umbilicalis provide considerably more fiber than many common fruits; for instance, bananas contain 3.1 g of fiber per 100 g, and P. umbilicalis contains 3.8 g of fiber per 100 g [51]. Dietary fiber plays a vital role in physiological processes, including enhancing intestinal motility and reducing postprandial blood glucose levels. According to Ferreira et al. [20], P. umbilicalis contains approximately 15% soluble fiber based on dw. Soluble fiber retains water and exhibits hydrocolloidal properties, which make it a valuable functional ingredient in food formulations [46]. In addition, the soluble dietary fiber found in red seaweeds has shown potential cardiovascular benefits, including the ability to lower LDL cholesterol levels [16]. However, due to the high fiber content of macroalgae, in vivo studies have reported low to moderate digestibility of their carbohydrates and polysaccharides [46].

4.4. Fats

Although red algae have a relatively low total fat content—typically between 1% and 2% of dw, they contain appreciable amounts of bioactive fatty acids with documented health benefits [17,52].

4.4.1. Fatty Acid Profile of Porphyra umbilicalis

Species of the genus Porphyra are particularly rich in long-chain n–3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC n–3 PUFAs), especially eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, C20:5 n–3), which may constitute up to 48% of the total fatty acid content. They also contain n–6 polyunsaturated fatty acids, including linoleic acid (C18:2) [52]. Linoleic acid is classified as an essential fatty acid (EFA), as the human body cannot synthesize it due to the absence of enzymes that introduce double bonds at the n–6 position of the carbon chain. Furthermore, linoleic acid serves as a metabolic precursor for the synthesis of other n–6 fatty acids, such as arachidonic acid, which is involved in inflammatory pathways [53]. Dietary intake of linoleic acid is therefore essential for maintaining physiological balance.

Maintaining an appropriate n–6/n–3 fatty acid ratio is critical for human physiological homeostasis. This imbalance arises because n–6 and n–3 fatty acids compete for the same enzymatic pathways, desaturases, and elongases. For instance, excessive consumption of n–6 fatty acids inhibits the metabolism of n–3 fatty acids and reduces their bioavailability [53,54]. Current recommendations suggest an n–6/n–3 intake ratio of approximately 5:1 [54]. However, n–6 intake in developed countries often exceeds recommended levels. The n–6/n–3 ratio in the Western diet may be as high as 20:1 [54,55]. Accordingly, an increase in the dietary intake of n–3 polyunsaturated fatty acids is advisable. P. umbilicalis has an n–6/n–3 ratio of 0.11, indicating its potential use in improving the lipid profile of food products by lowering their n–6/n–3 PUFA ratio [52,54,56].

Compared to brown algae such as Undaria pinnatifida (wakame) and Himanthalia elongata (sea spaghetti), P. umbilicalis contains lower amounts of saturated (SFAs) and monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), but a substantially higher proportion of PUFAs. A comparative profile of fatty acids in P. umbilicalis and selected brown algae is presented in Table 4. Moreover, P. umbilicalis demonstrates a PUFA content of approximately 56.4% of total fatty acids, which exceeds that of most marine fish, typically ranging from 20 to 50% [57]. According to Adarshan et al. [7], palmitic acid (C16:0) is the most prevalent saturated fatty acid in P. umbilicalis, while oleic acid (C18:1n–9) is the dominant monounsaturated fatty acid [7,52].

Table 4.

Comparison of the fatty acid profiles of Porphyra umbilicalis with Himanthalia elongata and Undaria pinnatifida [52].

The favorable lipid profile of P. umbilicalis indicates its potential utility in the development of dietary supplements and functional foods. The presence of PUFAs may support cardiovascular health through anti-inflammatory mechanisms. n–3 fatty acids lower triglyceride and VLDL-C (very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol) levels, improve endothelial function, and have anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic properties, thereby reducing the risk of heart attack and stroke. n–6 fatty acids (LA, ARA) lower LDL-C (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol) and improve the TC (total cholesterol) to HDL-C (high-density lipoprotein cholesterol) ratio.

Additionally, their antioxidant activity contributes to cellular protection and may play a role in the prevention of metabolic and degenerative disorders [58].

4.4.2. Bioavailability and Absorption Limitations

The bioavailability of lipids and fatty acids from macroalgae is relatively low, primarily due to limited lipolysis in the human gastrointestinal tract. Most edible seaweeds store lipids intracellularly, primarily as phospholipids and glycolipids associated with cellular membranes. This, combined with the human inability to enzymatically degrade dietary fiber, further limits lipid release and absorption. To increase the bioavailability of lipids and fatty acids from macroalgae, researchers have suggested applying mechanical disruption together with enzymatic treatment using cellulase before lipid extraction [46,59].

4.5. Vitamins

Vitamins are essential organic micronutrients that the human body cannot synthesize in sufficient quantities; therefore, they must be regularly obtained from the diet. P. umbilicalis, a red seaweed, provides significant amounts of various vitamins, including ascorbic acid (vitamin C), tocopherol (vitamin E), thiamine (B1), riboflavin (B2), niacin (B3), pyridoxine (B6), and folate (B9) [17]. The detailed vitamin profile of P. umbilicalis is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Vitamin profile of Porphyra umbilicalis, based on [60].

Among these, Porphyra is notably rich in vitamin C, a potent antioxidant involved in collagen synthesis and immune system modulation. The reported content of vitamin C is approximately 161.06 mg per 100 g of dw, which is comparable to levels found in commonly consumed vegetables such as lettuce and tomatoes [51]. Furthermore, P. umbilicalis contains notable amounts of vitamin B9 (12.53 mg/100 g dw) and vitamin B3 (9.51 mg/100 g dw), making it a potential contributor to dietary folate and niacin intake [60].

Vitamin B12

Vegetarians and vegans are particularly susceptible to vitamin B12 deficiency, as the primary sources of this vitamin are animal-derived foods [61,62]. Vitamin B12 plays a critical role in maintaining hematological homeostasis. A vegetarian and vegan dietary pattern carries a risk of undernutrition, including insufficient intake of vitamin B12. Such deficiencies contribute to the development of neurological and physiological disorders, including osteoporosis, and are associated with an increased risk of bone fractures [61]. Therefore, exploring alternative sources, such as macroalgae, may be essential to ensure adequate vitamin B12 intake in individuals adhering to vegetarian and vegan diets.

Macroalgae cannot synthesize vitamin B12 (cobalamin) autonomously due to the absence of genes encoding the enzymes necessary for the cobalamin biosynthesis pathway, a process exclusive to prokaryotes such as bacteria and archaea. It is hypothesized that red algae acquire vitamin B12 through symbiotic relationships with cobalamin-producing bacteria. The literature indicates that these bacteria may belong to the genus Halomonas [63].

Recent studies have identified vitamin B12 in Porphyra species in forms that may be bioavailable [39,64]. A clinical trial conducted by Qian-Ni Huang et al. [62] suggested that P. umbilicalis may be a plant-derived source of bioavailable vitamin B12. However, the study did not confirm the specific chemical forms of cobalamin present.

In contrast, other studies report that Porphyra contains active forms of vitamin B12, including methylcobalamin and 5′-deoxyadenosylcobalamin [24], which are bioavailable to humans. However, some evidence indicates that P. umbilicalis also contains B12 analogs that are structurally similar but not bioactive in humans [30].

Given these discrepancies, further research is necessary to assess the bioavailability and physiological effects of vitamin B12 from P. umbilicalis. Future studies should incorporate validated biochemical markers—including serum or plasma B12, holotranscobalamin (holoTC), homocysteine (Hcy), and methylmalonic acid (MMA)—to evaluate the efficacy of Porphyra as a sustainable source of vitamin B12 in plant-based diets [62].

4.6. Mineral Components

The mineral composition of P. umbilicalis varies significantly depending on several factors, including the duration of marine exposure, geographic origin, wave intensity, seasonality, environmental conditions, and post-harvest processing methods [32]. Table 6 presents the mineral content of P. umbilicalis.

Porphyra umbilicalis seems to be a rich source of essential elements, such as potassium, sodium, magnesium, calcium, iron, manganese, and zinc [32,60]. Sodium content in P. umbilicalis depends on the location of harvest and ranges from 940 mg/100 g dw to 1256 mg/100 g dw. These levels are substantially higher than those typically found in terrestrial plants. For instance, raw carrots contain approximately 707 mg of sodium/100 g dw, raw russet potatoes (without skin) contain about 14 mg/100 g dw, and raw cucumbers (with peel) contain 48 mg/100 g dw of sodium [65,66].

Potassium levels in Porphyra species range from 1428 to 2030 mg/100 g dw. For comparison, potassium content is approximately 1800 mg/100 g dw in soybeans, 135 mg/100 g dw in enriched wheat flour, and 75 mg/100 g dw in white rice flour [6]. Importantly, Porphyra macroalgae exhibit a favorable sodium-to-potassium (Na/K) ratio, ranging from 0.62 to 0.65. A Na/K ratio below 1 is considered nutritionally beneficial, while values exceeding 2.5 are associated with increased risk of hypertension and cardiovascular disease [67].

Porphyra umbilicalis contains high levels of magnesium, ranging from 379 to 714 mg/100 g dw [30,32]. Magnesium is among the most frequently deficient minerals in the general human population [52]. It is vital for maintaining the electrical potential across nerve and muscle cell membranes, supporting protein synthesis, and playing a key role in regulating heart rhythm. The magnesium content of P. umbilicalis exceeds that of commonly recognized magnesium-rich foods such as sunflower seeds (588.7 mg/100 g dw), almonds (449.5 mg/100 g dw), and hazelnuts (274.2 mg/100 g dw) [30,66].

According to the literature, the iron content of Porphyra species varies considerably, ranging from 5.3 to 278 mg/100 g dw, depending on harvest location and environmental conditions [30,68,69]. For example, macroalgae from Venezuela contain 15.5 mg of iron/100 g dw [68], while macroalgae from Bangladesh contain 253.6 mg of iron/100 g dw [30]. According to a study by Bito [24], the bioavailability of iron from raw Porphyra is approximately 6.4% when 10 g of seaweed is consumed. Another study suggests that iron absorption improves with increased intake and heat treatment, indicating that both the amount consumed and the preparation method influence bioavailability [24,68].

Porphyra umbilicalis appears to be a promising source of essential minerals and contributes to mineral fortification strategies, though further investigation is warranted to substantiate its nutritional benefits.

Table 6.

Mineral components in Porphyra umbilicalis [30,32,68,69].

Table 6.

Mineral components in Porphyra umbilicalis [30,32,68,69].

| Mineral Components | Amount [mg/100 g dw] |

|---|---|

| Sodium (Na) | 940–1256 |

| Calcium (Ca) | 313–330 |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 379–714 |

| Zinc (Zn) | 6 |

| Potassium (K) | 1428–2030 |

| Iodine (I) | 17 |

| Iron (Fe) | 5.8–278 |

4.7. Phenolic Compounds

Conclusive data on the phenolic compound profile of P. umbilicalis are currently lacking in the scientific literature. Nevertheless, due to its taxonomic and phylogenetic relatedness to other Porphyra species, such as P. dentata, P. tenera, and P. yezoensis, P. umbilicalis is likely to contain phenolic compounds with similar chemical structures and biological activities [23,24].

Several phenolic compounds, including catechin, rutin, and hesperidin, have been identified in P. dentata. Extracts from this species have demonstrated anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced nitric oxide (NO) production [70].

Similarly, extracts from P. tenera exhibit immunomodulatory properties in vitro. These include activation of the NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) signaling pathway, stimulation of cytokine production, and enhancement of macrophage phagocytic activity [23,71]. However, this information remains a hypothesis that requires experimental verification through targeted studies on P. umbilicalis.

Overall, phenolic compounds found in Porphyra species have been shown to exert antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and photoprotective effects [70]. Nevertheless, further research is required to confirm the presence, concentration, and precise structural characterization of phenolic compounds specifically in P. umbilicalis.

4.8. Change in Chemical Composition Depending on Environmental Conditions

The chemical composition of P. umbilicalis varies depending on several factors, including its developmental stage, environmental conditions such as temperature, light intensity, and photoperiod (i.e., the number of daylight hours in a 24 h cycle) [72], and the availability of nutrients, particularly nitrogen in the form of ammonium [73].

According to Lindsay et al. [29], macroalgae exhibit the highest growth rates and elevated accumulation of proteins and pigments when exposed to temperatures between 10 and 15 °C, a photoperiod of at least 12 h, and light intensities exceeding 110 μmol photons m−2s−1. The authors also reported pronounced seasonal variation in protein and pigment concentrations. During winter, when photoperiod and temperature are reduced, growth slows, while the concentration of certain bioactive compounds-such as phycobilins and proteins-increases. In contrast, during summer, longer daylight and higher irradiance promote more rapid biomass accumulation, often accompanied by a dilution effect that lowers the relative concentration of these compounds in the tissues.

Elevated ammonia concentrations (up to 300 μM) have also been associated with enhanced accumulation of proteins and pigments [73]. Furthermore, the developmental stage of P. umbilicalis affects its chemical profile. For instance, the conchocelis phase contains a higher proportion of essential amino acids (EAAs) compared to the blade phase, indicating a potentially higher nutritional value during this stage of development [35].

Environmental and physiological conditions also influence the mineral composition of macroalgae. These variations contribute to seasonal, geographical, and taxonomic differences in mineral content, making it difficult to generalize about the overall nutritional value of seaweeds [32]. For example, research by Wells et al. [31] indicates that macroalgae harvested in warm equatorial regions typically have lower mineral content than those collected from higher latitudes. Differences in the content of mineral components in P. umbilicalis are presented in Table 6.

Porphyra spp. samples originating from the Bay of Bengal (Bangladesh) are characterized by elevated concentrations of sodium, magnesium, and iron [30], which may be related to the inflow of river water into the bay, increased mineral sediment load, and reduced salinity typical of this aquatic environment. In contrast, Porphyra spp. samples from the Caribbean Sea (Venezuela) show significantly lower iron content, highlighting the strong influence of local environmental conditions on the mineral profile of marine macroalgae [68].

5. Pharmacological Properties of Porphyra umbilicalis

Limited data suggest that Porphyra species exhibit biological activities such as antioxidant, photoprotective, and anti-inflammatory effects [39]. However, confirmatory studies are still needed. Current pharmacological research on Porphyra primarily focuses on analyzing its purified bioactive fractions, including polysaccharides, proteins, and MAAs [24].

Macroalgae contain carotenoids and phycobiliproteins, both of which exhibit strong antioxidant properties [21]. Another important group of compounds is sulfated polysaccharides, which demonstrate antioxidant, anticancer, and immunomodulatory activities. Among them, porphyran stands out as the most studied polysaccharide and is considered a key contributor to the health-promoting potential of these seaweeds [23,74,75,76]. Additionally, P. umbilicalis is characterized by a high concentration of MAAs, particularly shinorine and porphyra-334, which exhibit UV-absorbing, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory effects [77]. According to Cofrades et al. [52], P. umbilicalis can be classified as a functional food due to its substantial health benefits. Table 7 summarizes the main bioactive compounds isolated from Porphyra and their associated pharmacological effects.

Table 7.

Pharmacological effects of bioactive compounds from the seaweed Porphyra.

5.1. Anti-Inflammatory Properties

Macroalgae of the Porphyra genus contain several bioactive compounds that have been suggested to possess anti-inflammatory properties. These include phycobiliproteins, sulfated polysaccharides, and MAAs [39].

A study by Sakai et al. [78] reported that phycobiliproteins, particularly phycoerythrin (PE), exhibited anti-inflammatory effects in vivo by inhibiting mast cell degranulation, a key process in immune responses and inflammatory conditions. Regulation of mast cell activity may attenuate inflammatory responses and represents a potential therapeutic target [39].

Another proposed mechanism involves the modulation of inflammatory signaling in macrophages. Tarasuntisuk et al. [80] demonstrated that MAAs such as shinorine and porphyra-334 reduced nitric oxide (NO) production in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages, indicating potential anti-inflammatory activity.

Similarly, Isak et al. [68] reported that sulfated polysaccharides extracted from P. yezoensis decreased both NO levels and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells in a dose-dependent manner. Nitric oxide (NO) levels were assessed indirectly by measuring nitrite concentrations in the supernatants of RAW 264.7 cell cultures using the Griess assay. These effects appear to be mediated by inhibition of the NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) signaling pathway [19,81].

Nitric oxide (NO), a free radical gas, is involved in key physiological processes such as vasodilation, neurotransmission, immune regulation, and apoptosis. However, excessive NO production-particularly via iNOS in activated macrophages, has been implicated in several inflammatory pathologies, such as sepsis and rheumatoid arthritis. Therefore, limiting NO synthesis is considered a relevant target in anti-inflammatory strategies [75].

Due to phylogenetic and chemical similarity with other Porphyra species, P. umbilicalis may exhibit comparable anti-inflammatory mechanisms. However, experimental data confirming such mechanisms in P. umbilicalis remain limited, and further studies are required to identify its specific bioactive compounds, elucidate their molecular targets, and assess efficacy in vivo and in human models. Moreover, the results are mainly based on cell-based assays, and their translation to human health outcomes has not been confirmed, requiring further clinical studies.

5.2. Antioxidant Properties

Porphyra umbilicalis contains multiple bioactive compounds with antioxidant potential, including porphyran, polyphenols, and MAAs. These compounds exhibit radical-scavenging activity, particularly against hydroxyl (•OH) and superoxide (O2•–) radicals, contributing to the macroalga’s ability to counteract oxidative stress [74].

López-López et al. [82] assessed the antioxidant activity of P. umbilicalis extracts using several assays, including the ABTS+ radical scavenging assay, the hydroxyl radical assay, and the nitric oxide radical (•NO) assay. The extracts were tested in a concentration-dependent manner, and radical-scavenging activity was quantified via absorbance measurements. The results indicated that P. umbilicalis exhibits significant antioxidant activity in vitro. In the same study, López et al. [82] also demonstrated that incorporating P. umbilicalis into processed meat products improved their nutritional quality and enhanced their antioxidant capacity. This points to the potential use of P. umbilicalis as a functional ingredient in food systems aimed at oxidative stability and health promotion.

A study by Ferreira et al. [77] also demonstrated antioxidant activity of P. umbilicalis, with aqueous extracts being more effective against ABTS+ radicals, while hydroethanolic extracts showed higher activity against hydroxyl radicals.

These results suggest that antioxidant activity depends on the extraction method and solvent polarity.

Vega et al. [79] evaluated seaweed extracts, including those from P. umbilicalis, for their antioxidant and photoprotective potential in cosmetic applications. Both aqueous and hydroethanolic extracts exhibited substantial radical-scavenging activity, primarily attributed to porphyran, polyphenols, MAAs, and pigments such as carotenoids and phycobiliproteins. The extracts also conferred protection against UV-induced oxidative damage, supporting their application in photoprotective skincare products.

These findings are largely derived from cell-based assays, and it remains unclear whether they translate to human health outcomes, highlighting the need for further clinical research.

5.3. Anti-Cancer Properties

Preliminary in vitro studies indicate that bioactive compounds present in P. umbilicalis may exhibit antiproliferative activity, primarily by inducing apoptosis and inhibiting cell cycle progression [39].

In vitro studies by João Ferreira et al. [77] demonstrated dose- and time-dependent cytotoxicity of P. umbilicalis extracts on the murine macrophage cell line RAW 264.7. The cells were treated with aqueous and hydroethanolic extracts at concentrations ranging from 0.05 to 0.75 mg/mL for 24 or 48 h. Aqueous extracts exhibited stronger cytotoxic activity than hydroethanolic extracts, with the highest efficacy recorded for P. umbilicalis extract (IC50 = 0.43 mg/mL).

5.3.1. Chemopreventive Effects in Animal Models

An in vivo study by Santos et al. [14] investigated the chemopreventive potential of P. umbilicalis in a transgenic mouse model genetically predisposed to developing HPV16-induced precancerous and malignant skin lesions. Mice were fed either a standard diet or a diet enriched with 10% P. umbilicalis. After histopathological analysis, a significant reduction in dysplastic lesions was observed in the P. umbilicalis-supplemented group, including complete lesion elimination in thoracic skin, without signs of toxicity or genotoxicity. These results indicate a possible antigenotoxic effect of P. umbilicalis under in vivo conditions [14]. Although direct molecular studies on P. umbilicalis are limited, mechanistic evidence from related species provides insight into possible anticancer pathways. For instance, Bito et al. [24] showed that porphyran, a compound isolated from P. tenera, exerted chemopreventive effects in a rat model of liver carcinogenesis. In vitro, porphyran inhibited IGF-1R phosphorylation and induced caspase-3 activation, triggering apoptosis in human gastric cancer cells. Due to the close taxonomic relationship between P. umbilicalis and P. tenera, similar biological mechanisms may be present; however, experimental verification in P. umbilicalis is still lacking.

5.3.2. Apoptotic Pathway Modulation by Porphyran

Kwon et al. [76] investigated the effects of porphyran, a sulfated polysaccharide derived from Porphyra spp., on apoptosis in gastric carcinoma AGS cells. The study showed that porphyran upregulated pro-apoptotic markers, such as Bax and caspase-3, while downregulating the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2. Additionally, porphyran suppressed IGF-I receptor phosphorylation and Akt pathway activation, both of which are involved in cell survival signaling. These results indicate that porphyran exerts antiproliferative activity against gastric cancer cells via apoptosis induction [76].

Despite these encouraging initial results, the anticancer properties of P. umbilicalis remain insufficiently characterized due to the limited availability of direct studies. Further research is needed to confirm the presence and bioactivity of specific antitumor compounds in P. umbilicalis and to establish effective and safe dosage ranges. Additionally, studies should elucidate the molecular mechanisms responsible for apoptosis induction and tumor growth suppression. Furthermore, most of the presented results come from cell-based studies, and their relevance to human health has yet to be established, necessitating additional clinical investigation.

6. Applications in the Food Industry

Porphyra yezoensis and P. tenera are the primary species used in the production of nori, a staple ingredient in traditional Japanese cuisine, particularly in dishes such as sushi. Although P. umbilicalis is not commonly used in Japanese nori, it is a closely related species found in the North Atlantic and increasingly explored for culinary applications. The popularity of Porphyra species as food is largely attributed to their distinctive umami flavor and favorable nutritional composition, including high protein content, essential amino acids, and bioactive compounds. Recent studies have explored the potential of P. umbilicalis as a functional ingredient in a variety of food products beyond its traditional culinary uses [23]. Blouin et al. [83] demonstrated that crushed P. umbilicalis is characterized by high sensory acceptability, comparable to that of P. yezoensis, which is more commonly used in the industry. These findings support the potential use of P. umbilicalis in Western-style food applications, including snacks and garnish products, particularly in regions where seaweed consumption has traditionally been low.

The availability of the sequenced genome of P. umbilicalis, along with the potential for genetic manipulation, opens new avenues for proteomic and metabolomic studies. This facilitates a deeper understanding of its biochemical composition and nutritional potential [26].

6.1. Nutritional Enrichment of Meat and Bakery Products

Fortification of processed meat products, such as sausages, patties, and restructured meats, with P. umbilicalis has been shown to improve their nutritional composition. The addition of this macroalga increases the content of dietary fiber, polyphenols, vitamins, and essential unsaturated fatty acids, while simultaneously reducing sodium, total fat, and saturated fat levels [84,85]. Of particular note is the macroalga’s high content of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), reported at 36.31 g/100 g of total fatty acids [44]. This makes it a strong candidate for use in meat and bakery products aimed at improving lipid composition and extending shelf life, due to the presence of antioxidants such as vitamin C and porphyran [83]. Furthermore, incorporating P. umbilicalis into the human diet may reduce trans fats and improve the n–6 to n–3 fatty acid ratio, contributing to cardiovascular health. Experimental studies by Cofrades et al. on Wistar rats have demonstrated that P. umbilicalis supplementation may mitigate the adverse effects of hypercholesterolemic diets, including reductions in atherogenic lipoprotein levels [85].

6.2. Clean Label and Functional Food Development

The bioactive compounds present in P. umbilicalis, particularly those with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, may enable a reduction in the use of synthetic preservatives when applied as a food ingredient. This aligns with the clean label trend, promoting transparency and natural formulation in food manufacturing. Therefore, the incorporation of P. umbilicalis as a functional ingredient supports the development of nutrient-enriched foods with health-promoting potential, providing both technological functionality and nutritional value in the context of sustainable product innovation [23,86].

7. Potential Risks Associated with Porphyra umbilicalis

The presence of heavy metals in edible seaweeds is a significant food safety concern, as macroalgae have a high capacity to bioaccumulate elements from their environment. The extent of this accumulation is influenced by various environmental factors, including salinity, temperature, pH, light exposure, nutrient availability, and oxygen levels [84].

A study by Besada et al. [87] analyzed heavy metal concentrations in 52 samples of different marine algae species, including P. umbilicalis. The results indicated that P. umbilicalis may contain elevated levels of certain metals, particularly cadmium (0.253–3.10 mg/kg dw), copper (5.50–14.1 mg/kg dw), and zinc (39.5–73.8 mg/kg dw). While these concentrations raise concern, it is important to note that the bioavailability of these metals to humans during digestion remains unclear. To date, it has not been definitively established whether the potentially hazardous heavy metals present in P. umbilicalis are effectively absorbed in the human gastrointestinal tract [31].

Another toxicological concern is the presence of arsenic, particularly in species of the Porphyra genus. Arsenic is a well-known toxic and carcinogenic element. Inorganic arsenic species, such as arsenite (As3+) and arsenate (As5+), are highly toxic to humans, whereas most organic arsenic forms are considered non-toxic [88]. According to the scientific literature, the total arsenic content in dried and roasted nori products ranges from 2.1 to 21.6 mg/kg dw, with approximately 0.1 mg/kg dw representing inorganic arsenic [88]. It has also been demonstrated that heat processing can increase the bioavailable fraction of arsenic, including its inorganic forms. This may lead to increased absorption of arsenic compounds in the human gastrointestinal system, potentially amplifying health risks [24].

Despite the bioaccumulation potential of arsenic in macroalgae, maximum levels for total or inorganic arsenic in seaweeds are not established in Europe for food. EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) and the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) have not issued specific regulations. Existing EFSA limits (total As 40 mg kg−1) apply only to seaweed meal and feed materials derived from seaweed [89,90]. The WHO (World Health Organization) provides guidance only for arsenic in drinking water (10 µg/L), not for seaweeds [91].

Studies by Stévant et al. [92] indicate that soaking macroalgae in warm water reduces both contaminants and bioactive compounds. Soaking in warm freshwater (32 °C) reduced iodine content, while immersing the seaweed in saline solution (2.0 M NaCl) reduced the relative cadmium content. The results of this study also highlight the difficulties in selectively reducing the level of toxic compounds from seaweed biomass without significantly affecting the nutrient content of the products. Moreover, this method requires further research to determine the optimal soaking conditions (i.e., time, water temperature, salinity).

Given these concerns, further research is warranted to assess the bioavailability of heavy metals and arsenic in P. umbilicalis, determine safe consumption limits, and evaluate potential health risks associated with chronic intake. Establishing clearer regulatory thresholds and refining analytical methods for assessing speciation and absorption will be crucial to ensure the safe use of P. umbilicalis as a dietary and functional food ingredient.

However, it should be noted that the toxicity of P. umbilicalis depends on the dose, form, and bioavailability of contaminants, with most available data indicating a moderate rather than acute risk.

8. Conclusions

Porphyra umbilicalis is a marine macroalga with significant potential as a functional food ingredient due to its rich nutritional composition and diverse biological activities. It contains high levels of sulfated polysaccharides, essential fatty acids, polyphenols, proteins, and vitamins, which contribute to its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties. These attributes suggest that P. umbilicalis could play a valuable role in promoting health and preventing chronic diseases, particularly when incorporated into modern diets as part of clean-label or plant-based food formulations. In addition, it may serve as a sustainable, alternative source of high-quality protein, offering nutritional benefits in vegetarian and vegan diets.

Despite promising results from in vitro and in vivo studies, current evidence remains limited, and many biological effects require further confirmation. The precise mechanisms of action for its anti-inflammatory and anticancer effects are not yet fully understood, and the bioactivity of specific compounds, especially proteins and polysaccharides, warrants detailed investigation. Additionally, the bioavailability of key nutrients, including vitamin B12, must be established to validate its role as a reliable dietary source, particularly for individuals following vegetarian or vegan diets.

Attention must also be paid to potential risks associated with heavy metal accumulation in P. umbilicalis. Environmental factors can influence the levels of toxic elements such as arsenic or cadmium, and although their bioavailability remains uncertain, further research is needed to assess potential health risks and ensure food safety standards are met. Moreover, strategies to mitigate these risks, including optimized processing techniques, require systematic evaluation.

In conclusion, P. umbilicalis shows considerable potential as a health-promoting dietary component. However, unlocking its full value requires comprehensive research aimed at confirming its efficacy, elucidating the molecular mechanisms of action, and ensuring consumer safety through proper environmental and toxicological assessments. Future research priorities should include clinical trials to validate the health effects on humans, studies on nutrient bioavailability, and the development of optimized extraction and processing methods that maximize beneficial compounds and minimize potential contaminants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.; writing—review and editing, A.K. and M.G.; supervision, M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Van Esse, G.W. The Quest for Optimal Plant Architecture. Science 2022, 376, 133–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, C.N.; de Evan, T.; Molina-Alcaide, E.; Novoa-Garrido, M.; Weisbjerg, M.R.; Carro, M.D. Preserving Saccharina Latissima and Porphyra Umbilicalis in Multinutrient Blocks: An In Vitro Evaluation. Agriculture 2023, 13, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, D.; Jaeger, S.R. Consumer Acceptance of Novel Sustainable Food Technologies: A Multi-Country Survey. J Clean Prod 2023, 408, 137119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, S.O.; Abrantes, L.C.S.; Azevedo, F.M.; Morais, N.d.S.d.; Morais, D.d.C.; Gonçalves, V.S.S.; Fontes, E.A.F.; Franceschini, S.d.C.C.; Priore, S.E. Food Insecurity and Micronutrient Deficiency in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.L.; West, K.P.; Black, R.E. The Epidemiology of Global Micronutrient Deficiencies. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 66, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, C.J.; Douglas, K.J.; Kang, K.; Kolarik, A.L.; Malinovski, R.; Torres-Tiji, Y.; Molino, J.V.; Badary, A.; Mayfield, S.P. Developing Algae as a Sustainable Food Source. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1029841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adarshan, S.; Sree, V.S.S.; Muthuramalingam, P.; Nambiar, K.S.; Sevanan, M.; Satish, L.; Venkidasamy, B.; Jeelani, P.G.; Shin, H. Understanding Macroalgae: A Comprehensive Exploration of Nutraceutical, Pharmaceutical, and Omics Dimensions. Plants 2024, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Sudhakar, K.; Mamat, R. Macroalgae Farming for Sustainable Future: Navigating Opportunities and Driving Innovation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigueros, E.; Amaro, F.; de Pinho, P.G.; Oliveira, A.P. Comprehensive Analysis of Dehydrated Edible Macroalgae: Volatile Compounds, Chemical Profiles, Biological Activities, and Cytotoxicity. J. Appl. Phycol. 2025, 37, 597–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghidoni, A.; Vosmer, T. Boats and Ships of the Arabian Gulf and the Sea of Oman Within an Archaeological, Historical and Ethnographic Context; Springer Nature: Berlin, Germany, 2021; ISBN 9783030515065. [Google Scholar]

- Carpena, M.; Pereira, C.S.G.P.; Silva, A.; Barciela, P.; Jorge, A.O.S.; Perez-Vazquez, A.; Pereira, A.G.; Barreira, J.C.M.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P.; Prieto, M.A. Metabolite Profiling of Macroalgae: Biosynthesis and Beneficial Biological Properties of Active Compounds. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Santamarina, A.; Cardelle-Cobas, A.; Mondragón Portocarrero, A.d.C.; Cepeda Sáez, A.; Miranda, J.M. Modulatory Effects of Red Seaweeds (Palmaria palmata, Porphyra umbilicalis and Chondrus crispus) on the Human Gut Microbiota via an in Vitro Model. Food Chem. 2025, 476, 143437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blouin, N.A.; Brodie, J.A.; Grossman, A.C.; Xu, P.; Brawley, S.H. Porphyra: A Marine Crop Shaped by Stress. Trends Plant Sci. 2011, 16, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.; Ferreira, T.; Almeida, J.; Pires, M.J.; Colaço, A.; Lemos, S.; Da Costa, R.M.G.; Medeiros, R.; Bastos, M.M.S.M.; Neuparth, M.J.; et al. Dietary Supplementation with the Red Seaweed Porphyra umbilicalis Protects against DNA Damage and Pre-Malignant Dysplastic Skin Lesions in HPV-Transgenic Mice. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codd, G.A.; Testai, E.; Funari, E.; Svirčev, Z. Cyanobacteria, Cyanotoxins, and Human Health; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 37–68. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, A.; Mahmoudnia, F. Biological Treatment of Heavy Metals with Algae. In Heavy Metals-Recent Advances; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.M.; Alotaibi, B.S.; EL-Sheekh, M.M. Therapeutic Uses of Red Macroalgae. Molecules 2020, 25, 4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanshin, N.; Kushnareva, A.; Lemesheva, V.; Birkemeyer, C.; Tarakhovskaya, E. Chemical Composition and Potential Practical Application of 15 Red Algal Species from the White Sea Coast (The Arctic Ocean). Molecules 2021, 26, 2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Fu, L.; Ci, F.; Mao, X. Porphyran and Oligo-Porphyran Originating from Red Algae Porphyra: Preparation, Biological Activities, and Potential Applications. Food Chem. 2021, 349, 129209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.; Trigo, M.; Aubourg, S.P.; Prego, R.; Ferreira, L.M.M.; Pacheco, M.; Silva, A.M.; Gaivão, I. Nutritional Profiling of Red Seaweeds Grateloupia turuturu and Porphyra umbilicalis: Literature-Based Insights into Their Potential for Novel Applications and Partial Replacement of Conventional Agricultural Crops. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2025, 251, 1643–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, C.; Sapatinha, M.; Mendes, R.; Bandarra, N.M.; Gonçalves, A. Dehydration, Rehydration and Thermal Treatment: Effect on Bioactive Compounds of Red Seaweeds Porphyra umbilicalis and Porphyra Linearis. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, C.T.C.; Morrison, H.G.; Mendonça, I.R.; Brawley, S.H. A Common Garden Experiment with Porphyra umbilicalis (Rhodophyta) Evaluates Methods to Study Spatial Differences in the Macroalgal Microbiome. J. Phycol. 2018, 54, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Kaushik, D.; Bansal, V.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, M. Unrevealing the Potential of Macroalgae porphyra Sp. (Nori) in Food, Pharmaceutics and Health Sector. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e70110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bito, T.; Teng, F.; Watanabe, F. Bioactive Compounds of Edible Purple Laver porphyra Sp. (Nori). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 10685–10692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J. Seaweeds and Microalgae: An Overview for Unlocking Their Potential in Global Aquaculture Development; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2021; Volume 1229, ISBN 9789251347102. [Google Scholar]

- Brawley, S.H.; Blouin, N.A.; Ficko-Blean, E.; Wheeler, G.L.; Lohr, M.; Goodson, H.V.; Jenkins, J.W.; Blaby-Haas, C.E.; Helliwell, K.E.; Chan, C.X.; et al. Insights into the Red Algae and Eukaryotic Evolution from the Genome of Porphyra umbilicalis (Bangiophyceae, Rhodophyta). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E6361–E6370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydlett, M. Examining the Microbiome of Porphyra umbilicalis in the North Atlantic. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Maine, Orono, ME, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gantt, E.; Berg, G.M.; Bhattacharya, D.; Blouin, N.A.; Brodie, J.A.; Chan, C.X.; Collén, J.; Cunningham, F.X.; Gross, J.; Grossman, A.R.; et al. Porphyra: Complex Life Histories in a Harsh Environment: P. Umbilicalis, an Intertidal Red Alga for Genomic Analysis; Springer Nature: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L.A.; Neefus, C.D. Effects of Temperature, Light Level, and Photoperiod on the Physiology of Porphyra umbilicalis Kützing from the Northwest Atlantic, a Candidate for Aquaculture. J. Appl. Phycol. 2016, 28, 1815–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T. Determination of Nutritional Composition of Potential Red Seaweed (Porphyra umbilicalis). Master’s Thesis, Chattogram Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Chattogram, Bangladesh, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, M.L.; Potin, P.; Craigie, J.S.; Raven, J.A.; Merchant, S.S.; Helliwell, K.E.; Smith, A.G.; Camire, M.E.; Brawley, S.H. Algae as Nutritional and Functional Food Sources: Revisiting Our Understanding. J. Appl. Phycol. 2017, 29, 949–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh Kumar, K.; Kumari, S.; Singh, K.; Kushwaha, P. Influence of Seasonal Variation on Chemical Composition and Nutritional Profiles of Macro-and Microalgae; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; ISBN 9781119542650. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G. Amino Acids Amino Acids; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003; Volume 96, ISBN 9781439861905. [Google Scholar]

- Cherry, P.; O’hara, C.; Magee, P.J.; Mcsorley, E.M.; Allsopp, P.J. Risks and Benefits of Consuming Edible Seaweeds. Nutr. Rev. 2019, 77, 307–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, M.; Machado, S.; Pimentel, F.B.; Freitas, V.; Alves, R.C.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Amino Acid Profile and Protein Quality Assessment of Macroalgae Produced in an Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture System. Foods 2020, 9, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Segovia, I.; Lerma-García, M.J.; Fuentes, A.; Barat, J.M. Characterization of Spanish Powdered Seaweeds: Composition, Antioxidant Capacity and Technological Properties. Food Res. Int. 2018, 111, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astorga-España, M.S.; Rodríguez-Galdón, B.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, E.M.; Díaz-Romero, C. Amino Acid Content in Seaweeds from the Magellan Straits (Chile). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2016, 53, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, K.H.M.; Guaratini, T.; Barros, M.P.; Falcão, V.R.; Tonon, A.P.; Lopes, N.P.; Campos, S.; Torres, M.A.; Souza, A.O.; Colepicolo, P.; et al. Metabolites from Algae with Economical Impact. Comp. Biochem. Physiol.-C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2007, 146, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Xu, X. Porphyra Species: A Mini-Review of Its Pharmacological and Nutritional Properties. J. Med. Food 2016, 19, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotsaert, F.A.J.; Pikus, J.D.; Fox, B.G.; Markley, J.L.; Sanders-Loehr, J. N-Isotope Effects on the Raman Spectra of Fe2S2 Ferredoxin and Rieske Ferredoxin: Evidence for Structural Rigidity of Metal Sites. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 8, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrew, P.W.; Rogers, L.J.; Boulter, D.; Haslett, B.G. Ferredoxin from a Red Alga, Porphyra umbilicalis. Eur. J. Biochem. 1976, 69, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klupšaitė, D.; Juodeikienė, G. Legume: Composition, Protein Extraction and Functional Properties. A Review. Chem. Technol. 2015, 66, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbersdobler, H.F.; Barth, C.A.; Jahreis, G. Legumes in Human Nutrition Nutrient Content and Protein Quality of Pulses. Ernahr. Umsch. 2017, 64, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, K.L.; Mehta, A. Health Benefits and Pharmacological Effects of Porphyra Species. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2019, 74, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazir, M.; Abuhassira, Y.; Robin, A.; Nahor, O.; Luo, J.; Israel, A.; Golberg, A.; Livney, Y.D. Extraction of Proteins from Two Marine Macroalgae, Ulva Sp. and Gracilaria Sp., for Food Application, and Evaluating Digestibility, Amino Acid Composition and Antioxidant Properties of the Protein Concentrates. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 87, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demarco, M.; Oliveira de Moraes, J.; Matos, Â.P.; Derner, R.B.; de Farias Neves, F.; Tribuzi, G. Digestibility, Bioaccessibility and Bioactivity of Compounds from Algae. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 121, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlström, N.; Harrysson, H.; Undeland, I.; Edlund, U. A Strategy for the Sequential Recovery of Biomacromolecules from Red Macroalgae Porphyra umbilicalis Kützing. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.F.; Li, Y.T.; Xia, W.; Wang, C.; Xie, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.B.; Zhou, T.; Fu, L.L. Degraded Polysaccharides from Porphyra haitanensis: Purification, Physico-Chemical Properties, Antioxidant and Immunomodulatory Activities. Glycoconj. J. 2021, 38, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotchkiss, S.; Brooks, M.; Campbell, R.; Philp, K.; Trius, A. The Use of Carrageenan in Food. In Carrageenans; Pereira, L., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 47–75. [Google Scholar]

- Arman, M.; Qader, S.A.U. Structural Analysis of Kappa-Carrageenan Isolated from Hypnea musciformis (Red algae) and Evaluation as an Elicitor of Plant Defense Mechanism. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 88, 1264–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, J.; Cardoso, C.; Serralheiro, M.L.; Bandarra, N.M.; Afonso, C. Seaweed Bioactives Potential as Nutraceuticals and Functional Ingredients: A Review. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 133, 106453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofrades, S.; López-Lopez, I.; Bravo, L.; Ruiz-Capillas, C.; Bastida, S.; Larrea, M.T.; Jiménez-Colmenero, F. Nutritional and Antioxidant Properties of Different Brown and Red Spanish Edible Seaweeds. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2010, 16, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, G.; Ecker, J. The Opposing Effects of N-3 and n-6 Fatty Acids. Prog. Lipid Res. 2008, 47, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishehkolaei, M.; Pathak, Y. Influence of Omega N-6/n-3 Ratio on Cardiovascular Disease and Nutritional Interventions. Hum. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 37, 200275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khalaifah, H.S.; Al-Nasser, A.Y. Evaluating the Potential of Marine Algae as Sustainable Ingredients in Poultry Feed. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usturoi, M.G.; Rațu, R.N.; Crivei, I.C.; Veleșcu, I.D.; Usturoi, A.; Stoica, F.; Radu Rusu, R.M. Unlocking the Power of Eggs: Nutritional Insights, Bioactive Compounds, and the Advantages of Omega-3 and Omega-6 Enriched Varieties. Agriculture 2025, 15, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ning, X.; He, X.; Sun, X.; Yu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Yu, R.Q.; Wu, Y. Fatty Acid Composition Analyses of Commercially Important Fish Species from the Pearl River Estuary, China. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matin, M.; Koszarska, M.; Atanasov, A.G.; Król-Szmajda, K.; Jóźwik, A.; Stelmasiak, A.; Hejna, M. Bioactive Potential of Algae and Algae-Derived Compounds: Focus on Anti-Inflammatory, Antimicrobial, and Antioxidant Effects. Molecules 2024, 29, 4695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernaertsa, T.M.M.; Verstrekena, H.; Dejongheb, C.; Gheysenb, L.; Foubert, I.; Grauweta, T.; Loey, A.M.V. Cell Disruption of Nannochloropsis Sp. Improves in Vitro Bioaccessibility of Carotenoids and Ω3-LC-PUFA. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 65, 103770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArtain, P.; Gill, C.I.R.; Brooks, M.; Campbell, R.; Rowland, I.R. Nutritional Value of Edible Seaweeds. Nutr. Rev. 2007, 65, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, S.; Oliveira, L.; Pereira, A.; Costa, M.d.C.; Raposo, A.; Saraiva, A.; Magalhães, B. Exploring Vitamin B12 Supplementation in the Vegan Population: A Scoping Review of the Evidence. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.N.; Watanabe, F.; Koseki, K.; He, R.E.; Lee, H.L.; Chiu, T.H.T. Effect of Roasted Purple laver (Nori) on Vitamin B12 Nutritional Status of Vegetarians: A Dose-Response Trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2024, 63, 3269–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, M.T.; Lawrence, A.D.; Raux-Deery, E.; Warren, M.J.; Smith, A.G. Algae Acquire Vitamin B12 through a Symbiotic Relationship with Bacteria. Nature 2005, 438, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez–Hernández, G.B.; Castillejo, N.; Carrión–Monteagudo, M.d.M.; Artés, F.; Artés-Hernández, F. Nutritional and Bioactive Compounds of Commercialized Algae Powders Used as Food Supplements. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2018, 24, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turck, D.; Castenmiller, J.; de Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Kearney, J.; Knutsen, H.K.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Pelaez, C.; et al. Dietary Reference Values for Sodium. EFSA J. 2019, 17, e05778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Search | USDA FoodData Central. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/food-search?type=Foundation (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Vaudin, A.; Wambogo, E.; Moshfegh, A.J.; Sahyoun, N.R. Sodium and Potassium Intake, the Sodium to Potassium Ratio, and Associated Characteristics in Older Adults, NHANES 2011-2016. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 122, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Casal, M.N.; Pereira, A.C.; Leets, I.; Ramírez, J.; Quiroga, M.F. High Iron Content and Bioavailability in Humans from Four Species of Marine Algae. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 2691–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEVA Porphyra (and Pyropia) Spp.—Nutritional Data Sheet. 2021. Available online: https://www.ceva-algues.com/en/document/nutritional-data-sheets-on-algae/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Kazłowska, K.; Hsu, T.; Hou, C.C.; Yang, W.C.; Tsai, G.J. Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Phenolic Compounds and Crude Extract from Porphyra Dentata. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 128, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.H.; Kang, H.B.; Park, S.H.; Jeong, J.H.; Park, J.; You, Y.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, J.; Kim, E.; Choi, K.C.; et al. Extracts of Porphyra Tenera (Nori Seaweed) Activate the Immune Response in Mouse RAW264.7 Macrophages via NF-ΚB Signaling. J. Med. Food 2017, 20, 1152–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath-Wiley, P.; Neefus, C.D.; Jahnke, L.S. Seasonal Effects of Sun Exposure and Emersion on Intertidal Seaweed Physiology: Fluctuations in Antioxidant Contents, Photosynthetic Pigments and Photosynthetic Efficiency in the Red Alga Porphyra umbilicalis Kützing (Rhodophyta, Bangiales). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2008, 361, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbee, N.; Huovinen, P.; Figueroa, F.L.; Aguilera, J.; Karsten, U. Availability of Ammonium Influences Photosynthesis and the Accumulation of Mycosporine-like Amino Acids in Two Porphyra Species (Bangiales, Rhodophyta). Mar. Biol. 2005, 146, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdala Díaz, R.T.; Casas Arrojo, V.; Arrojo Agudo, M.A.; Cárdenas, C.; Dobretsov, S.; Figueroa, F.L. Immunomodulatory and Antioxidant Activities of Sulfated Polysaccharides from Laminaria Ochroleuca, Porphyra umbilicalis, and Gelidium corneum. Mar. Biotechnol. 2019, 21, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaka, S.; Cho, K.; Nakazono, S.; Abu, R.; Ueno, M.; Kim, D.; Oda, T. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Porphyran Isolated from Discolored Nori (Porphyra yezoensis). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 74, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi-Jin Kwon, T.-J.N. Porphyran Induces Apoptosis Related Signal Pathway in AGS Gastric Cancer Cell Lines. Life Sci. 2006, 79, 1956–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.; Hartmann, A.; Martins-Gomes, C.; Nunes, F.M.; Souto, E.B.; Santos, D.L.; Abreu, H.; Pereira, R.; Pacheco, M.; Gaivão, I.; et al. Red Seaweeds Strengthening the Nexus between Nutrition and Health: Phytochemical Characterization and Bioactive Properties of Grateloupia turuturu and Porphyra umbilicalis Extracts. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021, 33, 3365–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, S.; Komura, Y.; Nishimura, Y.; Sugawara, T.; Hirata, T. Inhibition of Mast Cell Degranulation by Phycoerythrin and Its Pigment Moiety Phycoerythrobilin, Prepared from Porphyra yezoensis. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2011, 17, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, J.; Bonomi-Barufi, J.; Gómez-Pinchetti, J.L.; Figueroa, F.L. Cyanobacteria and Red Macroalgae as Potential Sources of Antioxidants and UV Radiation-Absorbing Compounds for Cosmeceutical Applications. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarasuntisuk, S.; Palaga, T.; Kageyama, H.; Waditee-Sirisattha, R. Mycosporine-2-Glycine Exerts Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Effects in Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-Stimulated RAW 264.7 Macrophages. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2019, 662, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Hama, Y.; Yamaguchi, K.; Oda, T. Inhibitory Effect of Sulphated Polysaccharide Porphyran on Nitric Oxide Production in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated RAW264.7 Macrophages. J. Biochem. 2012, 151, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-López, I.; Bastida, S.; Ruiz-Capillas, C.; Bravo, L.; Larrea, M.T.; Sánchez-Muniz, F.; Cofrades, S.; Jiménez-Colmenero, F. Composition and Antioxidant Capacity of Low-Salt Meat Emulsion Model Systems Containing Edible Seaweeds. Meat Sci. 2009, 83, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blouin, N.; Calder, B.L.; Perkins, B.; Brawley, S.H. Sensory and Fatty Acid Analyses of Two Atlantic Species of Porphyra (Rhodophyta). J. Appl. Phycol. 2006, 18, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.Q.; Azhar, M.A.; Munaim, M.S.A.; Ruslan, N.F.; Ahmad, N.; Noman, A.E. Recent Advances in Edible Seaweeds: Ingredients of Functional Food Products, Potential Applications, and Food Safety Challenges. Food Bioproc. Tech. 2025, 18, 4947–4974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofrades, S.; Benedí, J.; Garcimartin, A.; Sánchez-Muniz, F.J.; Jimenez-Colmenero, F. A Comprehensive Approach to Formulation of Seaweed-Enriched Meat Products: From Technological Development to Assessment of Healthy Properties. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 1084–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılınç, B.; Cirik, S.; Turan, G. Organic Agriculture Towards Sustainability; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besada, V.; Andrade, J.M.; Schultze, F.; González, J.J. Heavy Metals in Edible Seaweeds Commercialised for Human Consumption. J. Mar. Syst. 2009, 75, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Li, W.; Zhang, C.; Van Hulle, M.; Cornelis, R.; Zhang, X. Safety Evaluation of Organoarsenical Species in Edible Porphyra from the China Sea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 5176–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]