Abstract

Polymeric optical waveguides represent an essential component in photonic technology thanks to their ability to guide light through controlled structures, enabling applications in telecommunications, sensors, and integrated devices. With the development of new materials and increasingly versatile manufacturing methods, these structures are being integrated into various systems at a rapid pace, while their dimensions are constantly being reduced. This article explores the main fabrication methods for polymeric optical waveguides, such as traditional and maskless photolithography, laser ablation, hot embossing, nanoimprint lithography, the Mosquito method, inkjet printing, aerosol jet printing, and electrohydrodynamic (EHD) printing. The operating principle of each method, the equipment and materials used, and their advantages, limitations, and practical applications are evaluated, in addition to the propagation losses and characterization of the waveguides obtained with each method.

1. Introduction

The development and miniaturization of technologies in the field of optical structures are related to the methods, the manufacturing cost, and the characteristics of the materials used, where the size of essential components such as waveguides, couplers, micromirrors, add/drop multiplexers, etc., is increasingly reduced. With the development of microelectronics and the integration with electro-optical components, all on a single chip, the so-called photonic integrated circuits (PICs) have begun to appear [1,2,3].

Traditionally, silicon, with n ≈ 3.5 at 1550 nm [4], has been used as an optical material together with silicon dioxide for the creation of optical microstructures [5,6]. However, silicon is a rigid material, so developing micrometric and nanometric structures on it requires complex and expensive machinery such as photolithography scanners, steppers, mask aligners, and other machinery, in addition to chemical processes for its engraving like reactive ion etching (RIE) [7] or deep reactive ion etching (DRIE) [8], chemical vapor deposition (CVD) [9], atomic layer deposition (ALD) [10], and others. The development and use of new polymers with very good characteristics, and simple methods to produce them [11,12], increasingly contributes to a reduction in the cost of these systems. These types of polymeric substances are very attractive in terms of manufacturing costs and ease of handling and can be manipulated in a liquid state and cured by heat or exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light.

There are polymeric materials with high transparency, allowing almost all or the entire visible spectrum to be guided through them, as well as the infrared spectrum [13,14]. Once cured, they have mechanical characteristics that can be exploited for the development of polymeric optical waveguides. Some polymers do not harden completely, but form flexible structures, making them ideal for use as waveguides in optical interconnects [15] and flexible optical sensors [16,17]. Another positive feature of these materials is their compatibility with other substances of a similar organic nature, favoring their adhesion, and allowing the creation of fully polymeric core and cladding structures.

With the miniaturization of optical components, the development of waveguides and other smaller structures is becoming increasingly necessary. To this end, methods and techniques have been developed that allow very small, even submicron, dimensions, with very good results in terms of homogeneity, substrate adhesion, repeatability, etc.

The purpose of this review is to provide a unified framework for comparing the different techniques employed for manufacturing polymeric optical waveguides, considering both more conventional techniques (subtractive and replication methods) and recently developed additive techniques. It is shown how the choice in the fabrication method affects waveguide geometry, propagation losses, scalability or cost, and the trade-offs of each technique are also explained, thus helping to decide which is the best method for some given requirements or for a certain application. For each method, its operating principle, materials used, techniques employed, and parameters attained (dimensions and shape of the waveguide, propagation losses, etc.) are described, indicating the potential applications for each case. The methods discussed are listed below:

- ➢

- Photolithography

- ➢

- Laser ablation

- ➢

- Hot embossing and nanoimprint lithography

- ➢

- Mosquito method

- ➢

- Inkjet printing

- ➢

- Aerosol jet printing and flexographic printing

- ➢

- Electrohydrodynamic (EHD) jet printing

Photolithography and laser ablation are subtractive methods [18,19,20], while hot embossing and nanoimprint lithography are replication fabrication processes [21,22]. The remaining listed methods are additive manufacturing techniques [18,19,20]. We will cover these methods in the review, following the above order. Each section contains a table (Table 1 for subtractive methods, Table 2 for replication methods, and Table 3 for additive methods) that includes the main characteristics of the polymeric waveguides manufactured with the corresponding techniques. The information in the tables is ordered in columns that detail the fabrication method that has been employed for the waveguide, the materials that have been used for the core and the lower and upper claddings, the core dimensions, if the waveguide is single mode or multimode, and the propagations losses (specifying the wavelength). When some fields are empty, it means it was not possible to recover this information from the original work. At the end of the work, a summary will be provided outlining the similarities and differences between each method.

2. Subtractive Methods

2.1. Photolithography

Photolithography is a process used to transfer a pattern onto a substrate by employing ultraviolet light-sensitive substances [23,24,25,26]. For many years, this has been the most widely employed method for the fabrication of silicon-based PIC devices, and it is also utilized in the development of microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) [27]. This is due to the high resolutions that can be achieved using different types of photolithography [28,29,30,31].

2.1.1. Mask Photolithography

Classical types of this method use a photomask to transfer patterns onto a device layer on a substrate [32,33], divided into contact or proximity lithography [34,35], and projection lithography [36,37], where the resolution that can be achieved depends on the wavelength used and the optical diffraction of the light source. Other types of photolithography include immersion photolithography, which can reach a resolution of 7 nm [38,39], or extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUVL) [40], which can attain a resolution of 5 nm [41,42,43].

Photolithography has several advantages over other waveguide manufacturing processes, as it can achieve high production scale and produce a large number of devices simultaneously on a single substrate, depending on the complexity of the machinery and the sophistication of the employed techniques [44,45].

With the development of integrated photonics, photocurable polymeric substances are also being used for manufacturing optical structures [46]. For the fabrication of polymeric waveguides, negative photoresists with different physical, chemical, and optical properties are generally employed.

One of these photoresists is SU-8, which is used due to its mechanical and chemical stability, high transparency and low absorption. SU-8 also has a high cross-linking density, which enables it to achieve high resolutions and high aspect ratios with photolithography, but also leads to brittleness, limiting its use with other manufacturing methods [47]. In [48], single mode SU-8 waveguides with 4 × 2 µm dimensions are fabricated on a Si-SiO2 substrate by photolithography, with NOA61 as the upper cladding. The propagation losses are 0.62 dB/cm and 1.25 dB/cm at a wavelength of λ = 1.31 µm and λ = 1.55 µm, respectively. Wider multimode waveguides (up to 12 µm) are also manufactured. SU-8 waveguides on a Si-SiO2 substrate are also fabricated in [49], but in this case there is no upper cladding (air is the upper cladding). In this work, digital ultraviolet lithography (DUL) is the technique employed. DUL uses a digital micro-mirror device with many pixels that can be individually controlled as a virtual mask [50,51]. Single mode operation is achieved for 2.4 × 2.1 µm waveguides, with propagation losses of 2.38 dB/cm and a bending loss of 0.1 dB per 90° at λ = 1.55 µm. Furthermore, a 1 × 2 multimode interference power splitter, a 1 × 2 Y-branch power splitter, and a microring resonator are also demonstrated with this platform [49].

NOAs (Northland Optical Adhesives) are also photoresists, and NOA61 (which acts as the upper cladding in [48]) is employed as the waveguide core in [52], while NOA71 is used here as the cladding. Contact photolithography is the utilized technique, and the propagation losses are 0.85 dB/cm and 1.83 dB/cm at λ = 1.3 µm and λ = 1.55 µm, respectively, for a single mode waveguide with a cross section of 6 × 5 µm.

Another polymer that is used for manufacturing waveguides by means of photolithography is BCB (benzocyclobutene) [53]. Different formulations of BCB are employed as core and cladding to manufacture 8.7 × 6.8 µm single mode waveguides in [54], with propagation losses of 0.81 dB/cm at λ = 1.3 µm. BCB has also been used to fabricate waveguides on SiO2, with epoxy OPTOCAST 3553 (Electronic Materials Inc., Breckenridge, CO, USA) as the upper cladding [55,56], obtaining propagation losses higher than 1.5 dB/cm at λ = 1.55 µm.

Traditional optical mask lithography provides an efficient way to rapidly fabricate polymeric waveguides but requires complex and expensive machinery and equipment, as mentioned above. Many researchers are opting for other technologies that do not require the use of a mask in the process (also called maskless photolithography), which are also cheaper in terms of equipment and manufacturing process. These technologies include direct laser writing (DLW) [57] and electron beam lithography (EBL) [58,59].

The characteristics of the polymeric waveguides fabricated by mask photolithography described in this subsection, as well as by other subtractive methods that will be explained in the following subsections, are summarized in Table 1. In the materials column, the lower and the upper cladding can be made of the same or different materials. In the SM/MM column, ‘SM’ means that the corresponding waveguide is single mode for those conditions (materials employed for the core and the cladding, core dimensions, and operating wavelength), and ‘MM’ if it is multimode. Finally, for the propagation losses, the term ‘PDL’, which appears in some works, corresponds to the polarization dependent loss, that is, the difference in the propagation losses for the TE (transverse electric) and TM (transverse magnetic) polarizations.

2.1.2. Maskless Photolithography

Direct Laser Writing (DLW)

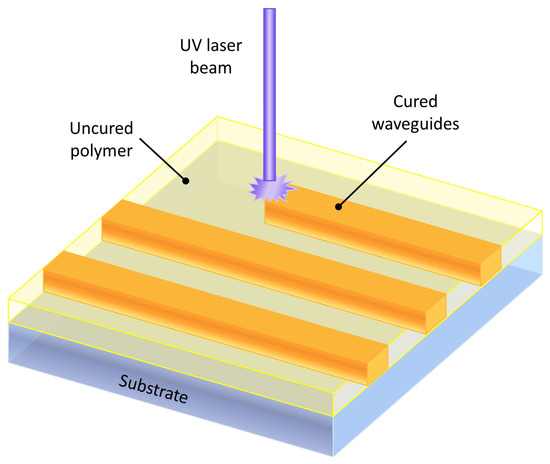

Direct laser writing uses a head assembly with a coordinate system to form the patterns to be drawn. A laser is mounted on the head at the wavelength required to photo cure the deposited material, allowing for the formation of patterns [57,60,61]—see Figure 1. With this method, point diameters of 50 nm have been manufactured using the polymer IP-dip [62].

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of direct laser writing.

As in the case of mask lithography, SU-8 can also be employed to manufacture waveguides by means of direct laser writing [63]. Here, both single mode (0.6 × 0.6 µm) and multimode (1.7 × 0.6 µm) SU-8 waveguides are fabricated on a Si-SiO2 substrate with a 405 nm laser, with propagation losses of 4.38 dB/cm and 6.4 dB/cm at λ = 633 nm, respectively. On the other hand, it is also worth mentioning some optical structures made with IP-dip using direct laser writing [64,65]. A polymeric micro-resonator consisting of a micro-cylinder coupled with a Mach–Zehnder interferometer for refractive index sensing is presented in [64], while a microring resonator for ultrasound detection is developed in [65].

Electron Beam Lithography (EBL)

For electron beam lithography (EBL) writing, a focused electron beam of extremely short wavelengths is used to act directly on the surface of an electron-sensitive photoresist and form a micro- or nanostructure matching the designed pattern [58,59]. EBL systems have the advantages of ultra-high resolution [66,67], with limiting resolutions between 1 and 3 nm with materials such as PMMA (polymethyl methacrylate) resist [68,69], and flexibility in the design, as they do not require a mask to transfer the pattern, like direct laser writing. Electron beams are essentially charged particles that are accelerated by a high potential and focused on a given point. The higher the acceleration voltage of the electron beam, the shorter its wavelength, being the basis of its high resolution.

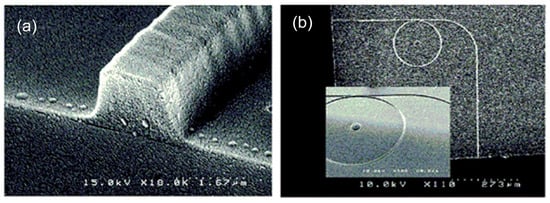

Previously mentioned polymers, such as SU-8 or NOAs, are also used to manufacture waveguides with electron beam lithography. A single mode SU-8 waveguide is fabricated on a Si-SiO2 substrate in [70], with a cross section of 1.38 × 4.8 µm and propagation losses of 1.03 dB/cm at λ = 1.3 µm. The same material, but with the use of epoxy UV15 and epoxy Epo-Tek OG-125 (Epoxy Technology, Billerica, MA, USA) as the lower and upper claddings, respectively, is employed to manufacture single mode waveguides (2 × 2 µm) in [71]—see Figure 2a. Microring resonators and Mach–Zehnder interferometers are developed based on this platform—see Figure 2b [71].

Figure 2.

(a) SEM image of the end-facet of the SU-8 waveguide. (b) SEM image of an SU-8 microring resonator. Reprinted with permission from [71]. Copyright 2004 American Chemical Society.

NOA61, utilized with mask photolithography in [48,52], is used with EBL in [72]. In this work, single mode waveguides of epoxy Novolak resin (ENR) are made, with NOA61 as the lower cladding. The widths are in the 4–8 µm range, with a height of 1.8 µm. When employing NOA61 as the upper cladding, the propagation losses are 0.22 dB/cm and 0.48 dB/cm at λ = 1.31 μm and λ = 1.55 μm, respectively, while without upper cladding, they are higher, especially at λ = 1.31 μm. Another material, polymer mr-L 6000, is employed to fabricate 6 × 1 μm single mode waveguides by means of EBL in [73], with polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon®, Dupont, DE, USA) as the cladding.

With the different types of photolithography, structures with very high resolution and well-defined geometries can be obtained, making it ideal for the development of high-quality optical waveguides. However, while some techniques offer considerable flexibility due to the absence of a mask, they are typically less efficient in production time due to their inherent single-point scanning nature. Furthermore, expensive equipment is required, which, while cheaper in the case of maskless lithography, is still expensive, and needs highly skilled handling. Another aspect worth noting is that these methods are subtractive in nature, resulting in considerable material waste each time these structures are manufactured.

For this reason, many researchers are opting for alternative methods for manufacturing optical waveguides using cheaper techniques. With the development of automated CNC (computer numerical control) systems and new types of lasers, optical waveguides have begun to be developed, using ablation as the manufacturing method. This allows for the production of small optical waveguides in a wide variety of shapes, depending on the needs and capabilities of the machines used.

2.2. Laser Ablation

Unlike photolithography, which requires advanced and expensive equipment to form the designed patterns, laser ablation is a procedure used to remove material from the surface of a solid or liquid by irradiating it with a computer-controlled laser beam, that is, the patterns to be printed can be easily controlled, and the equipment is simpler and more compact. When the laser radiation flux is low, the surface of the material heats up by absorbing the energy of the photons of the beam and sublimates. In this case, the amount of absorbed energy can be controlled, and thus the amount of material that can be removed by the application of a single pulse. This depends on both the optical and thermodynamic properties of the material, as well as the power and wavelength of the laser. The process is carried out by controlling the duration of the laser pulses, which can vary from a few milliseconds to a few femtoseconds, and the intensity of the flow. This precise control makes this technique highly valuable for both research and industry [74,75,76]. Laser ablation is employed with a wide range of polymers, including polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) or polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), among others [77].

This method is subtractive, like photolithography, so spin coating is generally used to deposit layers of the desired material for subsequent removal by ablation. Depending on the type of waveguide desired, a layer of the cladding material is deposited first, followed by the core material. Both layers are then polymerized using UV light, and once they are cured, a laser is applied to remove the unwanted material. Subsequently, if an upper cladding is required, another layer of the cladding material is applied—see Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the laser ablation process. (a) Deposition of the lower cladding and core layers on the substrate. (b) Material removal by laser ablation to form the waveguides. (c) Deposition of the upper cladding (if required).

Regarding waveguide manufacturing, multimode waveguides with a cross section of 65 × 55 µm are fabricated with a KrF excimer laser (operating wavelength λ = 248 nm) in [78], using Truemode (an acrylate polymer) as the waveguide material. The propagation losses are 0.13 dB/cm, 0.035 dB/cm, and 0.17 dB/cm at λ = 850 nm, λ = 980 nm, and λ = 1.31 µm, respectively. The same waveguide material is utilized in [79], on a substrate made of FR4, and with polysiloxane as the material for the cladding. Different lasers are explored in this work, including a CO2 laser (λ = 10.6 µm), an UV Nd:YAG laser (two different laser models, λ = 355 nm), and a KrF excimer laser (λ = 248 nm). 45 × 45 µm and 35 × 70 µm waveguides are fabricated with each UV Nd:YAG laser, respectively, while 50 × 35 µm ones are obtained with the KrF excimer laser. Laser ablation with the CO2 laser is also successful, but the dimensions of the manufactured waveguides are not provided. These results show that laser ablation of polymers can be achieved at several different wavelengths with different lasers.

It is also worth mentioning the fabrication of waveguides by laser ablation on materials other than polymers, such as aluminum oxide (AL2O3) [80]. Rib waveguides with a cross section of 10 × 0.75 µm are manufactured on a SiO2 substrate, using a Yb fiber laser (λ = 1030 nm), and obtaining propagation losses of 3.8 dB/cm at λ = 632.8 nm.

One of the disadvantages of laser ablation is that it is a subtractive method, like photolithography, which means that material is wasted with each print. As opposed to this, hot embossing and nanoimprint lithography enable the manufacturing of optical structures with a high degree of replication, more quickly and economically.

Table 1.

Polymeric optical waveguides fabricated by subtractive methods.

Table 1.

Polymeric optical waveguides fabricated by subtractive methods.

| Fabrication Method | Material (Lower Cladding/Core/ Upper Cladding) | Core Dimensions (µm) | SM/MM | Propagation Losses (dB/cm) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photolithography | SiO2/SU-8/NOA61 | 4 × 2 | SM | 0.25, PDL: 0.03 (λ = 800 nm) 0.62, PDL: 0.15 (λ = 1.31 µm) 1.25, PDL: 0.46 (λ = 1.55 µm) | [48] |

| 6–12 × 2 | MM | ||||

| Digital UV lithography | SiO2/SU-8/Air | 2.4 × 2.1 | SM | 2.38 (λ = 1.55 µm) | [49] |

| Contact photolithography | NOA71/NOA61/NOA71 | 6 × 5 | SM | 0.85 (λ = 1.3 µm) 1.83 (λ = 1.55 μm) | [52] |

| Photolithography | BCB/BCB/BCB (different formulations) | 8.7 × 6.8 | SM | 0.81 (λ = 1.3 µm) | [54] |

| Photolithography | SiO2/BCB/OPTOCAST 3553 | 4 × 2.8 | SM | 1.8, PDL: 0.15 (λ = 1.55 μm) | [55] |

| Photolithography | SiO2/BCB/OPTOCAST 3553 | 5 × 2 | SM | 1.6, PDL: 0.4 (λ = 1.55 μm) | [56] |

| Direct laser writing | SiO2/SU-8/Air | 0.6 × 0.6 | SM | 4.38 ± 0.55 (λ = 633 nm) | [63] |

| 1.7 × 0.6 | MM | 6.4 ± 0.3 (λ = 633 nm) | |||

| Electron beam lithography | SiO2/SU-8/Air | 1.38 × 4.8 | SM | 1.03 ± 0.19 (λ = 1.3 μm) | [70] |

| Electron beam lithography | UV15/SU-8/Epo-Tek OG-125 | 2 × 2 | SM | - | [71] |

| Electron beam lithography | NOA61/ENR/NOA61 | (4–8) × 1.8 | SM | 0.22 (λ = 1.31 μm), 0.48 (λ = 1.55 μm) | [72] |

| NOA61/ENR/Air | 0.41 (λ = 1.31 μm), 0.49 (λ = 1.55 μm) | ||||

| Electron beam lithography | Teflon/mr-L 6000/Teflon | 6 × 1 | SM | - | [73] |

| Laser ablation | Truemode (core), cladding not specified | 65 × 55 | MM | 0.13 (λ = 850 nm), 0.035 (λ = 980 nm), 0.17 (λ = 1.31 μm) | [78] |

| Laser ablation | Polysiloxane/Truemode/Polysiloxane | 45 × 45, 35 × 70, 50 × 35 | MM | - | [79] |

3. Replication Methods

Hot Embossing and Nanoimprint Lithography (NIL)

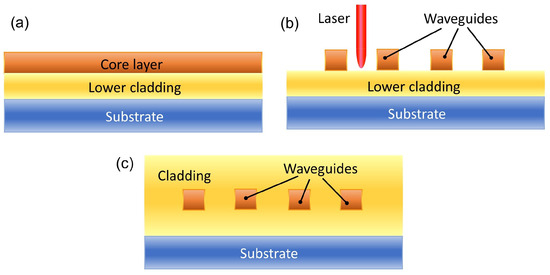

Unlike photolithography and laser ablation, hot embossing and nanoimprint lithography are flexible and cost-effective manufacturing technologies with very high replication rates. Hot embossing consists of heating a thermoplastic polymer (a polymer that softens through heating) above its glass transition temperature and applying pressure with a mold to form a microstructure—see Figure 4a [81,82,83]. Many structures can be manufactured in a single mold, allowing for large-scale manufacturing and cost-effectiveness, making it a very attractive technique. If the pattern is imprinted by using rollers or a roller and a plate, the terms roll-to-roll (R2R) or roll-to-plate (R2P) hot embossing are employed [84,85].

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of (a) hot embossing, (b) thermal nanoimprint lithography (thermal NIL), and (c) ultraviolet nanoimprint lithography (UV NIL).

Thermal nanoimprint lithography (thermal NIL) is similar to hot embossing, but the term hot embossing is used when the mold is applied to a polymeric substrate, while in thermal nanoimprint the mold is applied to a polymeric film or imprint resist on a substrate—see Figure 4b [86,87,88]. In thermal nanoimprint, as opposed to hot embossing, it is required to remove the residual resist, for instance, by etching [86]. Furthermore, roll-to-roll and roll-to-plate techniques can also be employed in the case of NIL [89]. Another type of nanoimprint lithography is UV NIL, where the mold is applied to a polymeric photoresist and cured with UV light, avoiding the heating and high pressure of thermal NIL—see Figure 4c [86,89,90]. In hot embossing and NIL, the mold can be made of silicon, quartz, metals, or high-resolution plastics [86,89]. A master mold, for instance, one made of silicon, is sometimes used to produce a stamp made of a polymeric material, which is the one that will be used to manufacture the desired structure. The type of technique used for a certain polymer will depend on its characteristics.

Regarding waveguide fabrication, hot embossing is employed to mold the lower cladding, which then has to be filled with the core material and covered by the upper cladding. On the contrary, NIL enables the direct fabrication of the waveguide on the substrate that acts as the lower cladding; then, the core will be covered by an upper cladding layer, if necessary, although variations can exist. One of their advantages is that several parallel waveguides can be fabricated at the same time with a single mold.

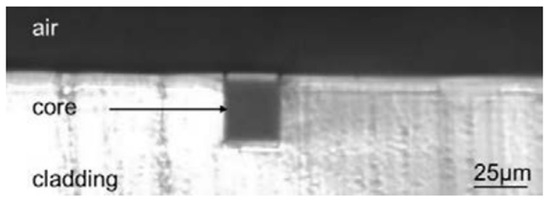

A PMMA lower cladding is fabricated by hot embossing in [91] and then filled with an epoxy resin and covered with a PMMA layer to form the core and the cladding, respectively. PMMA is a thermoplastic [92], which explains its use as lower cladding in many waveguides fabricated by hot embossing. Waveguides with 100 × 100 µm, 300 × 300 µm, and 500 × 500 µm cross sections are manufactured, measuring propagation losses of 0.3 dB/cm, 0.22 dB/cm, and 0.19 dB/cm at λ = 650 nm, respectively. In the last case, the propagation losses have been improved to 0.13 dB/cm by additional smoothing of the surface of the lower cladding. PMMA lower claddings manufactured by hot embossing are also utilized in [93] for producing 25 × 28 µm multimode waveguides—see Figure 5. Different polymeric materials are explored for the core (NOA68, OG198-54 and OG142), obtaining the lowest propagation losses at λ = 633 nm for NOA68 (0.74 dB/cm), and at λ = 850 nm for OG198-54 (0.3 dB/cm).

Figure 5.

Cross section of a waveguide with a PMMA lower cladding fabricated by hot embossing and NOA68 as the core material. Reproduced under the terms of CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License [93]. Copyright 2016, The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

A polymeric multimode waveguide (42 × 43 µm cross section) is fabricated by hot embossing in [94], using a UV-curable material as the core and PMMA as the cladding. Here, the most relevant result is that the propagation losses of the waveguides at λ = 850 nm can be lowered from 0.7 dB/cm to 0.1 dB/cm by reducing the sidewall roughness of the silicon master mold that is employed to produce the PMMA lower cladding. Similar waveguides are obtained in [95] (60 × 60 µm waveguides with 0.12 dB/cm propagation losses at λ = 850 nm), but here two different methods are used: hot embossing and microcontact printing [96] (technique that shares some characteristics with UV NIL). Other polymers studied for manufacturing waveguides by hot embossing include SB40, Epotek 301, Epotek 310-M2, Polytec EP601, and Polytec EP610 [97]. In this work, SB40 waveguides with a 100 × 60 µm cross section are fabricated but their propagation losses are very high (6.4 dB/cm at λ = 850 nm).

Regarding single mode waveguides manufactured by hot embossing, ZP1010M and ZP2145M are employed for the core and the cladding, respectively, in [98], obtaining 7 × 7 µm waveguides with a propagation loss of 0.67 dB/cm at λ = 1.55 µm. Single mode waveguides with a 7 × 7 µm cross section are also fabricated in [99], using in this case polymer WIR30-106 for the core and PMMA and ZPU12-450 for the lower and the upper claddings, respectively. The propagation losses are slightly higher than in the previous work (0.83 dB/cm at λ = 1.55 µm). Multimode waveguides are also manufactured in [99], with a UV-curable resin as the core and PMMA as the cladding. In this work [99], polymeric waveguides are investigated for use in optical structures such as a parallel optical interconnection module or a multichannel variable optical attenuator.

With respect to thermal NIL, single mode Teflon waveguides are fabricated on a silicon substrate in [73], having a 0.4 × 0.245 µm cross section and with polystyrene (PS) as the upper cladding. Thermal NIL has also been employed to manufacture polymeric optical structures such as grating couplers [100,101] or microring resonators [101]. In the case of UV NIL, multimode waveguides made of polymers mr-L6000 and NOA81 are fabricated on a Si-SiO2 substrate in [102], using PMMA as the upper cladding, and with widths in the 60–100 µm range and a height of 80 µm. The propagation losses for the mr-L6000 waveguides are 1.6 dB/cm at λ = 1.31 µm.

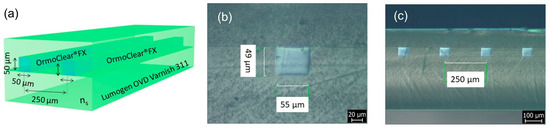

On the other hand, R2P UV NIL is the utilized method in [103]. First, a PDMS stamp is produced from a nickel master mold. Then, a lower cladding made of polymer Lumogen OVD Varnish 311 (BASF, Charlotte, NC, USA) is fabricated on a glass plate by using the PDMS stamp on the cylinder of a R2P machine and UV light for curing. Subsequently, the channels are filled with polymer OrmoClear by doctor blading [104] to form the waveguides. Finally, an upper cladding of Lumogen OVD Varnish 311 is deposited and cured. This way, 12 channels with a 50 × 50 µm cross section and a 250 µm pitch are simultaneously obtained—see Figure 6. The waveguides are characterized at several wavelengths between λ = 532 nm (propagation losses of 0.63 dB/cm), and λ = 1.55 μm (1.34 dB/cm). Other polymers that have been employed for manufacturing waveguides by NIL include BCB, PMMA, NOA72, and OPTOCAST 3505 [53].

Figure 6.

(a) Schematic diagram of the OrmoClear waveguides in a cladding made of Lumogen OVD Varnish 311, with a cross section of 50 × 50 µm and a pitch of 250 µm. (b) Cross section view of one of the manufactured waveguides. (c) Cross section view of four waveguides. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license [103]. Copyright 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland.

The properties of the polymeric waveguides manufactured by replication methods that have been listed in this section are summarized in Table 2. In refs. [91,97] it is not indicated if the waveguides are single mode or multimode because the original works do not mention it, but considering their dimensions, the refractive index contrast between the core and the cladding, and the operating wavelength, it is reasonable to assume they are multimode.

In summary, replication methods have the advantage of not requiring expensive equipment to manufacture optical waveguides, and many can be fabricated at once, depending on the mold dimensions and the channel spacing. However, they have the disadvantage that the channel dimensions depend exclusively on the mold, so a new mold must be produced each time the design is changed. Many researchers have therefore turned their attention to additive methods that do not require significant resources or advanced equipment. With the development of 3D printing and more precise automated CNC systems, printed optical waveguides have begun to be developed using different printing variants such as the Mosquito method, inkjet printing, aerosol jet printing, or EHD jet printing. These methods allow for the production of small optical waveguides in a wide variety of shapes, depending on the needs and capabilities of the machines used.

Table 2.

Polymeric optical waveguides fabricated by replication methods.

Table 2.

Polymeric optical waveguides fabricated by replication methods.

| Fabrication Method | Material (Lower Cladding/Core/ Upper Cladding) | Core Dimensions (µm) | SM/MM | Propagation Losses (dB/cm) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot embossing | PMMA/Epoxy resin/PMMA | 100 × 100 | - | 0.30 (λ = 650 nm) | [91] |

| 300 × 300 | 0.22 (λ = 650 nm) | ||||

| 500 × 500 | 0.13–0.19 (λ = 650 nm) | ||||

| Hot embossing | PMMA/OG198-54/Air | 25 × 28 | MM | 0.97 (λ = 633 nm), 0.30 (λ = 850 nm) | [93] |

| PMMA/OG142/Air | 2.56 (λ = 633 nm), 1.05 (λ = 850 nm) | ||||

| PMMA/NOA68/Air | 0.74 (λ = 633 nm), 0.81 (λ = 850 nm) | ||||

| Hot embossing | PMMA/UV-curable material/PMMA | 42 × 43 | MM | 0.1 (λ = 850 nm) | [94] |

| Hot embossing and microcontact printing | PMMA/UV-curable epoxy/PMMA | 60 × 60 | MM | 0.12 (λ = 850 nm) | [95] |

| Hot embossing | PMMA/SB40/PMMA | 100 × 60 | - | 6.4 (λ = 850 nm) | [97] |

| Hot embossing | ZP2145M/ZP1010M/ZP2145M | 7 × 7 | SM | 0.67 (λ = 1.55 μm) | [98] |

| Hot embossing | PMMA/WIR30-106/ZPU12-450 | 7 × 7 | SM | 0.83 (λ = 1.55 μm) | [99] |

| PMMA/UV-curable resin/PMMA | 43 × 43 | MM | 0.2 (λ = 850 nm) | ||

| Thermal NIL | Si/Teflon/PS | 0.4 × 0.245 | SM | - | [73] |

| UV NIL | SiO2/mr-L6000/PMMA | (60–100) × 80 | MM | 1.6 (λ = 1.31 μm) | [102] |

| SiO2/NOA81/PMMA | - | ||||

| R2P UV NIL | Lumogen OVD Varnish 311/OrmoClear/Lumogen OVD Varnish 311 | 50 × 50 | MM | 0.63 (λ = 532 nm), 0.54 (λ = 650 nm), 0.43 (λ = 850 nm), 0.56 (λ = 1.31 μm), 1.34 (λ = 1.55 μm) | [103] |

4. Additive Methods

4.1. Mosquito Method

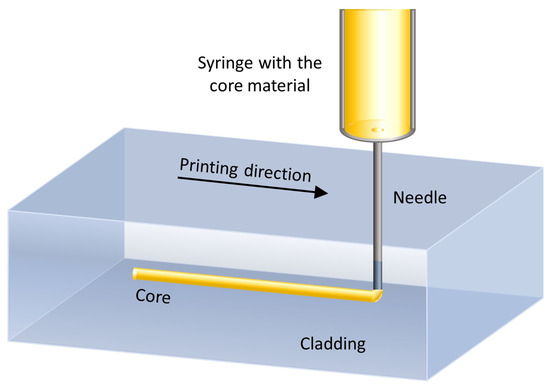

The Mosquito method is an additive technique that uses a micro dispenser (usually pneumatic) to insert a material into another material [105,106,107]. The viscous core material is pulled into the cladding material from a fine syringe needle connected to a dispenser—see Figure 7. The system moves the needle horizontally, resulting in the formation of a circular waveguide structure within the cladding material, both in the liquid phase (called the wet-in-wet approach [108]). The cladding material can be deposited by spin coating to establish its thickness, or can be confined in a cavity or channel, where the needle will subsequently be inserted to deposit the core [109].

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the Mosquito method.

The polymers employed for the core and the cladding are very similar in nature (they are miscible with each other), and when they are in contact in the liquid phase, they mix slightly, so the interface between them is not clearly defined and a concentration distribution is established towards the core. Subsequently, the assembly is exposed to UV light and to an additional post-baking depending on the material, obtaining one or several waveguides embedded within a block of cladding material. The diameter of the waveguides depends on parameters such as the printing speed, the diameter of the needle, and the pressure of the material pushing onto the needle [109].

The Mosquito method was initially introduced in [105], in which 12 parallel multimode waveguides were fabricated with a core diameter (∅) of 40 µm and a 250 µm pitch. The employed polymers were FXW712 and FX-W713 (for the core and the cladding, respectively), and the obtained waveguides had a good performance (0.033 dB/cm at λ = 850 nm, and −50 dB of crosstalk). Subsequently, single mode waveguides at 1.31 µm/1.55 µm were obtained in [110], using in this case the polymers NP-005 and NP-211 SUNCONNECT® (Nissan Chemical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) for the core and the cladding, respectively, and with ∅ = 7.9 µm. The propagation losses were 0.29 dB/cm and 0.45 dB/cm at 1.31 µm and 1.55 µm, respectively. It was later explored how to fabricate these waveguides in a 3D crossover structure [111]. This consists of several waveguides that cross over each other by varying their height within the structure, thus requiring both horizontal and vertical bends.

Other materials that have been utilized for fabricating waveguides with the Mosquito Method are Ormocore (core) and polymer J + S (Jänecke+Schneemann Druckfarben GmbH) (cladding) [109]. Here, the effect of the pneumatic pressure applied to the dispensing system (0.3 bar and 0.4 bar) and the printing speed (varied from 1 mm/s to 7 mm/s) on the core diameter is assessed, obtaining values between 12 µm and 44 µm, where the smallest diameters correspond to the lowest pressure and the highest printing speeds.

The Mosquito method has also been used for manufacturing more complex optical structures with polymers, including a fan-in/out waveguide for a multicore fiber [112], a spot size converter based on a tapered waveguide [113], and a Y-branch waveguide [114].

In summary, this additive technique is a very attractive option for the manufacture of low-cost optical waveguides, as it does not require complex machinery. Furthermore, the depth at which the waveguide is deposited can be controlled [115]. This enables the creation of 3D patterns, permitting the printing of curved waveguides and increasing their density per unit volume [111,116].

However, since the core material is completely embedded within the cladding, these waveguides are limited to applications related to information transmission and cannot be employed in sensors, in which part of the core must be exposed for interaction with external substances. Due to this limitation, other additive and low-cost methods have been developed, allowing for the production of waveguides without upper cladding (thus the core is exposed), such as inkjet printing.

4.2. Inkjet Printing

Inkjet printing allows tiny drops of ink to be projected in a controlled manner onto a substrate [117,118,119,120,121]. It is a technology widely used by commercial multifunction printers. It consists of projecting the drops sequentially, one after the other, so that a thin row of drops is formed according to the shape to be printed. This means the process has an additive nature in terms of the material used, thus reducing the waste of material, in comparison with subtractive methods [119,122].

Inkjet printing utilizes a print head system, or a tiny needle (mounted on a syringe), to deposit droplets with a volume between 1 and 1000 pL from a position above the substrate. This is one of the main advantages of the technique: defined deposition, but without contact between the nozzle and the substrate. Furthermore, the process has high geometric flexibility, since new print patterns can be created on the substrate without intermediate steps [119,123].

As the waveguides are printed on a surface (a substrate or a previously deposited lower cladding), the shape of the waveguide tends to be parabolic or semicircular, unlike waveguides obtained by previous methods. Depending on the application, an upper cladding can also be printed on the waveguide.

The choice and formulation of the injectable material is crucial, since its properties, such as viscosity and surface tension, affect its injection efficiency. The employed materials must have a low viscosity, as they can clog the print head otherwise. Furthermore, the interaction of the deposited material with the substrate determines their adhesion and subsequently the aspect ratio of the structure and its stability [124]. In order to achieve the adhesion of different materials to a substrate, treatments such as corona [125] or plasma [126] are often used.

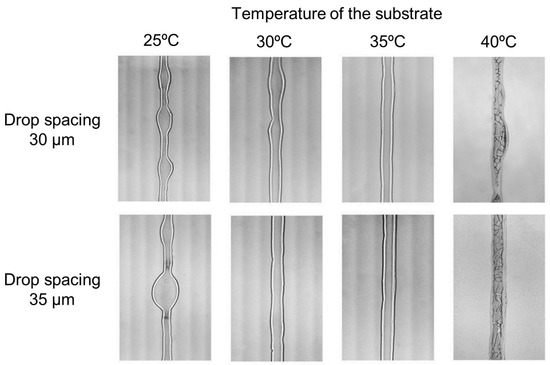

Regarding waveguide fabrication, 145 × 20 µm parabolic-shaped waveguides are manufactured using inkjet printing in [127] on a PMMA substrate, with propagation losses of 1.4 dB/cm at λ = 785 nm. The employed polymers are Syntholux (an acrylate base resin) and EGDMA (ethylene glycol dimethacrylate) for both the core (50%/50% mix) and the upper cladding (30%/70% mix). Although they do not employ polymers, it must be highlighted that single mode waveguides at λ = 1.55 µm are achieved in [128], but the propagation losses reach 3.52 dB/cm. The waveguides are made of titania ink on a quartz substrate (no upper cladding), with widths in the 30–60 µm range and heights in the 120–250 nm range (between 1 and 4 printed layers). Here, the effect of the temperature of the substrate and the drop spacing on the uniformity of the waveguides is assessed—see Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Effect of the temperature of the substrate (25–40 °C) and the drop spacing (30–35 µm) on the uniformity of waveguides made of titania ink on a quartz substrate. Adapted from [128]. Copyright© 2017, American Chemical Society.

It is also worth mentioning the fabrication of multimode polymeric waveguides in [129] by direct ink writing, a technique that shares similarities with inkjet printing but produces continuous filaments instead of droplets [130,131]. In [129], rectangular 175 × 55 µm PMMA waveguides with a PDMS cladding are fabricated, and propagation losses of 0.21 dB/cm, 0.42 dB/cm, and 1.08 dB/cm are measured at λ = 980 nm, λ = 1.31 µm, and λ = 1.55 µm, respectively.

Other polymeric materials utilized for manufacturing waveguides by inkjet printing include Truemode [122], SU-8 and NOA65 [132], InkEpo and InkOrmo [123], and Genomer resins [133]. Truemode waveguides (with a cladding made of cured Truemode, which has a lower refractive index) are fabricated in [122], with widths in the 50–75 µm range and a maximum height of 7 µm, although obtaining waveguides with an even width is challenging. As the waveguides are formed by a set of small circular drops joined through the surface tension among the drops and with the substrate, irregularities in the edges of the waveguide can appear if the distance between drops and the alignment between them is not accurately controlled.

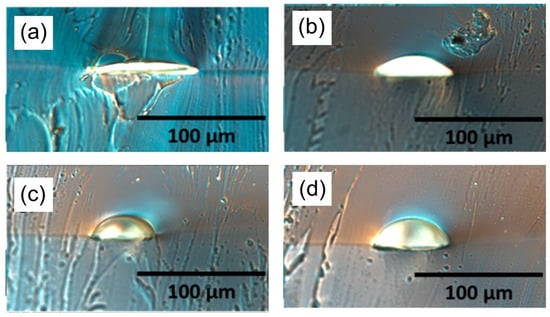

In [132], an SU-8 waveguide, with NOA65 as the cladding, is manufactured with good uniformity, but with a very low aspect ratio (35 × 1.58 µm). InkEpo and InkOrmo are used in [123] for the core and the cladding, respectively, obtaining parabolic-shaped multimode waveguides with a higher aspect ratio of 10 µm/100 µm (height/width) for those with cladding, and a 20 µm/100 µm aspect ratio for those without cladding. An even higher aspect ratio of 0.4 is achieved in [133], fabricating 80 µm-wide waveguides made of resins of the Genomer series on a PDMS substrate and reaching a contact angle of around 85°—see Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Cross section of waveguides made of resins of the Genomer series for (a) the baseline, (b) the baseline + one layer, (c) the baseline + two layers, (d) the baseline + three layers. The contact angle and the aspect ratio increases with the number of layers. Adapted from [133]. Copyright© 2017, American Chemical Society.

Therefore, some of the challenges of inkjet printing are the uniformity of the waveguides and obtaining higher aspect ratios, similar to those achieved with other methods. One alternative that has been explored to manufacture waveguides with the most uniform edges and geometry possible consists of combining aerosol jet printing and flexographic printing [134,135].

4.3. Aerosol Jet Printing and Flexographic Printing

Aerosol jet printing consists of using a directed aerosol stream to form a pattern on a substrate, achieving resolutions of 10 µm [136,137]. The aerosol is generated by ultrasonic or pneumatic atomization of inks, and then it is transferred to the deposition head by a carrier gas flow. In the deposition head, a sheath gas surrounds the carrier gas, collimating the beam. The aerosol then passes through the nozzle, that focuses it and directs the droplets towards the substrate, separated from the nozzle between 1 and 5 mm [136,138].

There are several parameters that must be controlled in aerosol jet printing. The atomizer power and the ink temperature impact on the viscosity, which affects the droplet size distribution and the aerosol density. On the other hand, the printing speed is related to the print thickness, and the substrate temperature can affect the film uniformity [136]. It is also relevant to control the process to avoid overspray, that is, the deposition of small satellite droplets at the edges [138].

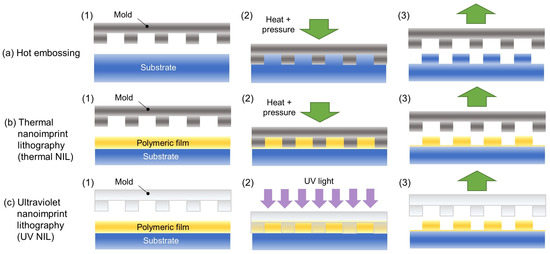

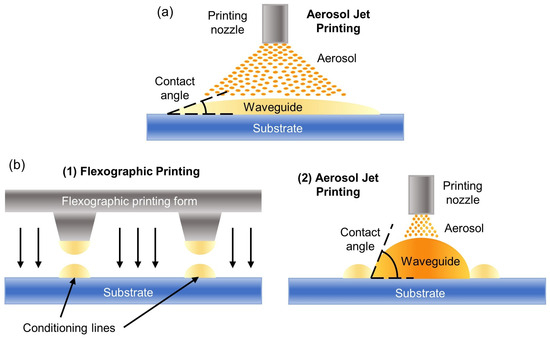

The main drawback for manufacturing waveguides by aerosol jet printing is obtaining a high aspect ratio (see Figure 10a) as it has been already observed in the case of inkjet printing. For instance, parabolic-shaped waveguides are printed with different polymeric inks on several substrates by aerosol jet printing in [139], obtaining aspect ratios of 1/151 (455 × 3 µm cross section), 1/30 (228 × 7.6 µm), and 1/13 (191 × 14.4 µm) for substrates made of polycarbonate, polyimide, and glass, respectively.

Figure 10.

(a) Schematic diagram of aerosol jet printing. (b) Schematic diagram of flexographic printing of the conditioning lines (1), and aerosol jet printing of the waveguide (2) (known as the OPTAVER process). The use of conditioning lines enables us to increase the contact angle and the aspect ratio of the waveguides.

The proposed solution consists of printing the waveguide between two previously printed lines of a different material, named conditioning lines and manufactured by flexographic printing—see Figure 10b. The whole method (aerosol jet printing and flexographic printing) is also named OPTAVER process because it was introduced by the OPTAVER research group [134,140,141]. Flexographic printing, employed for the conditioning lines, is a type of roll-to-plate process, in which a series of rollers with different functions are used for printing, utilizing a liquid polymer or ink [134,142].

Multimode waveguides made of polymer J + S 390119 are fabricated in [143] by aerosol jet printing after producing two conditioning lines made of ACTEGA G8/372L (a silicone containing varnish). The average propagation losses are 0.55 dB/cm, achieving 0.22 dB/cm for the best case at λ = 850 nm, and the waveguides have been successfully tested for data transmission at 10 Gbit/s. Here, the contact angle is 61.4° and the aspect ratio has been improved to 0.15 (200 × 30 µm parabolic cross section). Similar J + S 390119 waveguides (460 × 114.5 cross section, thus 0.25 aspect ratio, with a contact angle of 50°) have been employed in [144] to manufacture an asymmetrical coupler. Other polymers that have been explored for this manufacturing process include Ormocore [135]. It is also worth mentioning that flexographic printing has also been tested on its own to manufacture polymeric waveguides [123].

In conclusion, by means of the OPTAVER process, fairly uniform waveguides can be achieved quickly and easily, and they do not require complex and expensive equipment for their manufacture. The main disadvantages are that it requires two different processes, extending manufacturing time and making it more complex. Furthermore, the patterns engraved on the printing roller cannot be modified. Therefore, other more flexible techniques have also been explored, such as electrohydrodynamic (EHD) jet printing.

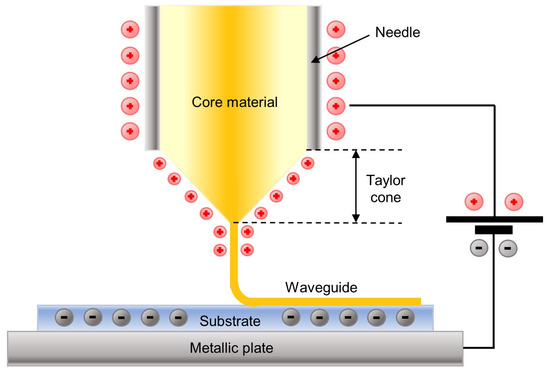

4.4. Electrohydrodynamic (EHD) Jet Printing

Electrohydrodynamic (EHD) jet printing, also known as e-jet printing or EHD jet printing, is a variant of inkjet printing in which a high electrical potential (DC or pulsed) is applied between the printing nozzle (usually a needle mounted on a syringe) and the substrate. The potential deforms the drop that exits the extruder tip depending on the force of gravity, the surface tension and the generated electric field. This deformation narrows the drop, forming the Taylor cone, and pulls it, forming small drops or fine threads of material that are printed onto the substrate [145], see Figure 11. This technique enables combining different printing modes depending on the characteristics of the material and the applied voltage, such as printing a continuous single thread or pulsing in small drops, or electrospinning and electrospraying. EHD jet printing has become a viable method for the micro/nanometric scale fabrication of photonic devices [146,147,148].

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of electrohydrodynamic (EHD) jet printing.

As it happens in inkjet printing or aerosol jet printing, in EHD jet printing the material to be printed is deposited in liquid phase on a substrate, thereby obtaining semicircular or parabolic cross sections. One of the factors that affects the shape is material viscosity, having a higher aspect ratio with a higher viscosity [149].

If fine thread printing is employed, polymeric patterns with thicknesses in the order of 100 µm to 100 nm can be achieved [146,150,151,152]. Thicknesses of the order of tens of microns have been attained in the fields of microelectronics and nanotechnology [153,154,155]. In order to achieve small dimensions, printing nozzles or tips with very small diameters and material flow rates are used, so that the material is deposited very uniformly and at a constant speed. Furthermore, the technique is flexible in terms of the shape of the patterns that can be printed, since the movement of the extruder nozzle is controlled by computer.

A large number of materials can be printed, including metallic inks (e.g., Ag-based inks), polymers, and biological materials [152,153,156,157]. As this method uses an electrical voltage to stretch the thread to be printed, it performs better with inks of a conductive nature. Therefore, many of the applications where it is used involve sensor devices with some electrical component or sensors with materials that change their properties in response to an electrical current [158,159,160,161,162,163].

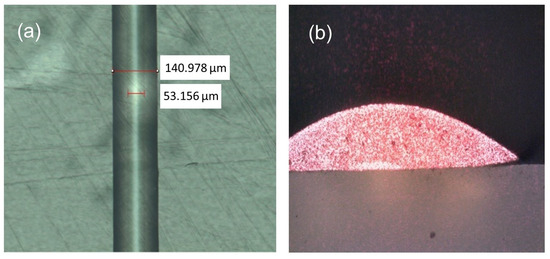

However, standard EHD jet printing cannot produce waveguides with an upper cladding in a single step. If an upper cladding is required, one option is coating the already printed waveguides with the same or other method. For instance, we have printed a parabolic EpoCore10 waveguide on a PFA (perfluoroalcoxi) substrate by EHD jet printing, and then an EpoClad10 cladding has been printed on top of it by direct ink writing. The dimensions of the core are 50 × 10 µm, while the whole cross section (with the cladding) is 140 × 20 µm, see Figure 12a. Light transmission was successfully tested both in the visible (λ = 635 nm), see Figure 12b, and in the infrared (λ = 1310 nm) via butt coupling.

Figure 12.

(a) Waveguide manufactured by EHD jet printing (EpoCore10 core) and direct ink writing (EpoClad10 cladding). (b) Illuminated cross section of the waveguide (a) when transmitting light at λ = 635 nm.

On the other hand, 7 µm-wide waveguides were fabricated by EHD jet printing in [164], using polymers NOA164 and NOA1375 (for the core and the cladding, respectively) on a silicon substrate coated with gold and treated with plasma to improve adhesion. The core is printed and cured with UV light, and then the cladding is printed on top and cured. In this work [164], other optical structures, such as a microlens array and a diffraction grating, were also fabricated by EHD jet printing. In fact, EHD jet printing is considered an interesting technique to fabricate microlenses or microlens arrays [165,166,167].

A second possibility to obtain waveguides with an upper cladding by EHD jet printing is to use a coaxial needle, so the core and cladding materials are printed simultaneously, which is known as coaxial EHD jet printing. This way, the core material is completely wrapped in the cladding material [168,169,170]. In case the materials are miscible, they will mix slightly and a concentration distribution will be established towards the core, as in the Mosquito method.

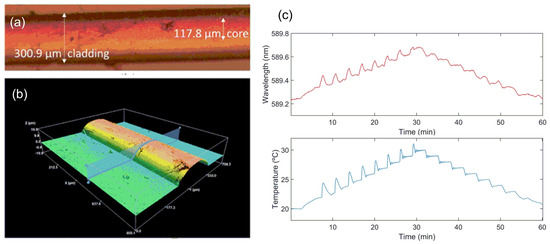

This method is employed to develop a temperature sensor in [171]. A waveguide is manufactured by coaxial EHD jet printing, using different formulations containing PAA (polyacrylic acid) and water for both the core and the cladding on a flexible flat acetate substrate—see Figure 13a,b. The core material is also doped with rhodamine B, a fluorescent material that is sensitive to temperature. A green laser (λ = 520 nm) is placed above the polymeric waveguide and a fiber is coupled to one of its ends, measuring the fluorescence peak at λ = 589 nm. The sensitivity in the 20–30 °C range is approximately −46.15 AU/°C and 0.044 nm/°C for the fluorescence peak intensity and the wavelength, respectively—see Figure 13c for the wavelength-based temperature sensing.

Figure 13.

(a) Waveguide manufactured by coaxial EHD jet printing with a PAA cladding and a PAA core doped with rhodamine B. (b) Thickness measurement of the waveguide (a) by confocal microscopy. (c) Temperature sensing based on the fluorescence peak wavelength shift.

In conclusion, EHD jet printing is a promising technique for manufacturing polymeric optical waveguides, as it can print complex patterns on many different substrates and reduces the time between design and manufacturing of the first prototype in comparison with more complex conventional techniques. However, further research is required to manufacture and fully characterize optical waveguides, as well as achieving dimensions in the order of the few microns.

The characteristics of the polymeric waveguides fabricated by the additive methods described in this section are summarized in Table 3. It must be noted that the waveguides manufactured by the Mosquito method have a circular cross section, while those fabricated with inkjet printing, aerosol jet printing, or EHD jet printing have a parabolic or semicircular cross section. In several works, it is not specified if the waveguides are single mode or multimode but, considering their dimensions, the refractive index contrast between the core and the cladding, and the operating wavelength, they are probably multimode, except maybe for [164], although we do not know the height of the waveguides in this case. The propagation losses have likewise not been characterized in a significant number of works.

Table 3.

Polymeric optical waveguides fabricated by additive methods.

Table 3.

Polymeric optical waveguides fabricated by additive methods.

| Fabrication Method | Material (Lower Cladding/Core/ Upper Cladding) | Core Dimensions (µm) | SM/MM | Propagation Losses (dB/cm) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mosquito method | FX-W713/FXW712/FX-W713 | ∅ 40 | MM | 0.033 (λ = 850 nm), 0.34 (λ = 1.31 μm), 1.25 (λ = 1.55 μm) | [105] |

| Mosquito method | NP-211/NP-005/NP-211 | ∅ 7.9 | SM | 0.29 (λ = 1.31 μm), 0.45 (λ = 1.55 μm) | [110] |

| Mosquito method | Polymer J + S/Ormocore/Polymer J + S | ∅ 12–44 | - | - | [109] |

| Inkjet printing | PMMA/Syntholux+ EGDMA/Syntholux+ EGDMA | 145 × 20 | - | 1.4 ± 0.4 (λ = 785 nm) | [127] |

| Inkjet printing | Truemode (cured)/Truemode/Truemode (cured) | 50–75 × 7 | - | - | [122] |

| Inkjet printing | NOA65/SU-8/NOA65 | 35 × 1.58 | - | - | [132] |

| Inkjet printing | InkOrmo/InkEpo/InkOrmo | 100 × 10 | MM | - | [123] |

| PVC/InkEpo/Air | 100 × 20 | ||||

| Inkjet printing | PDMS/Genomer resin/PDMS | 80 × 32 | - | - | [133] |

| Direct ink writing | PDMS/PMMA/PDMS | 175 × 55 | MM | 0.21 (λ = 980 nm), 0.42 (λ = 1.31 μm), 1.08 (λ = 1.55 μm) | [129] |

| Aerosol jet + flexographic | PMMA/J + S 390119/Air | 200 × 30 | MM | 0.2 (best case), 0.55 (average) (λ = 850 nm) | [143] |

| EHD jet printing | Au-coated Si/NOA164/NOA1375 | 7 × ? | - | - | [164] |

| Coaxial EHD jet printing | Acetate/PAA + water doped with RhB/PAA + water | 118 × 18 | - | - | [171] |

5. Conclusions and Future Outlook

This review summarizes several fabrication techniques whose purpose is to manufacture polymeric optical waveguides with high transparency and stability in the visible and infrared spectral ranges for their use in photonic integrated circuits. They rely on advanced polymeric materials such as SU-8, NOAs, etc., selected for their ability to be molded or cured using UV light or heat, as well as for their specific optical properties.

These methods can be classified primarily as subtractive, replication, and additive techniques, each with distinct operating principles but geared towards meeting the precision, scalability, and cost requirements of various optical applications. The main similarities and differences among the methods are indicated in Table 4. Aspects such as the process approach, the resolution, the waveguide width range of the manufactured waveguides, the cost and complexity of the equipment used, the flexibility in the design to be printed, the production speeds that can be achieved, and the material waste in the manufacturing process are compared.

Table 4.

Comparison of the methods presented in the work.

Subtractive methods, especially mask lithography, are the most consolidated and established techniques, and they achieve high resolution and well-defined geometries, allowing them to fabricate single mode polymeric waveguides. However, they suffer from high cost, material waste, and limited flexibility in design iteration. This makes them ideal for high-volume, high-performance PICs and telecommunication applications, but less practical for rapid prototyping or flexible devices. On the other hand, laser ablation is more compact and versatile than photolithography, but it generally cannot reach the same resolution.

In the case of replication methods, their strength is their scalability and cost-efficiency, as several waveguides can be manufactured simultaneously with a single mold. They enable the fabrication of single mode waveguides (although they do not reach dimensions in the order of the few microns as easily as lithography), but they are more economical than subtractive techniques. Nevertheless, they are limited by mold design: once a mold is fabricated, channel dimensions are fixed, limiting flexibility for iterative design optimization. For mass-market devices such as connectors or parallel optical interconnects, replication methods provide the best balance between cost and acceptable performance. However, surface roughness of the mold directly impacts propagation losses, which can restrict performance in high-density integration applications.

Finally, additive techniques allow for rapid design iteration, three-dimensional structures, and lower material waste. Despite their advantages, they face limitations in aspect ratio, edge roughness, and uniformity, which usually lead to higher propagation losses compared to subtractive methods. Moreover, they rarely achieve single mode operation or dimensions in the order of the microns, and they are not usually as well characterized as waveguides fabricated by other methods, so further research is required into these techniques. Therefore, they are best suited for low-cost, flexible, and application-specific devices (optical interconnects, disposable biosensors, or wearable photonic devices), rather than ultra-low-loss PICs.

While the described techniques present different strategies for fabricating polymeric optical waveguides, future progress relies on addressing several challenges. In the first place, a major trend is the development of hybrid fabrication methods, exploiting the strengths of each of them, such as combining the resolution of subtractive methods with the design freedom of additive techniques, although other combinations are also possible [172,173,174]. These approaches can reduce costs and accelerate the transition from the lab to the market.

Another promising direction is the application of machine learning and artificial intelligence in process optimization. Fabrication of polymeric waveguides involves several interdependent parameters (viscosity, curing time, and printing speed, among others) that strongly affect geometry and optical performance, and which could be optimized with artificial intelligence. For instance, physics-informed machine learning is proposed for additive methods in [175], while a convolutional neural network is employed in [176] to predict the losses due to waveguide curvature for flexographically printed polymeric waveguides.

Finally, another challenge is the development of novel functional polymers. Beyond transparency and low loss, next-generation polymers may incorporate properties such as tunable refractive indices, nonlinear responses, or biocompatibility. Fluorinated polymers, for example, offer very low propagation losses, making them excellent candidates for integrated optics, and they are combined in [177] with SiO2 nanoparticles and MgF2 to achieve a low thermo-optic coefficient, a useful property for manufacturing optical waveguides. Similarly, inorganic–organic hybrid polymers (Ormocore is an example of these materials) are very attractive, as many of their physical properties (density, thermal stability, refractive index, optical losses) can be tailored by controlling their composition [178].

In conclusion, this review aims to serve as a guide for selecting the most appropriate method for fabricating polymeric optical waveguides depending on the specific requirements of the application. By analyzing the trade-offs, such as high precision versus cost, or scalability versus design flexibility, this analysis provides a comprehensive framework to help researchers identify the most suitable method for different applications of polymeric waveguides, from low-loss PICs to low-cost sensors. Finally, it also suggests that adopting hybrid fabrication techniques, the use of artificial intelligence, and the development of new polymeric materials will contribute to improving the quality and functionality of manufactured waveguides.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M.A., J.M.C. and I.R.M.; Methodology, I.R.M. and J.J.I.; Software, A.O.; Validation, J.M.C., I.R.M. and C.E.; Formal Analysis, J.J.I. and A.O.; Investigation, F.M.A., J.J.I. and J.M.C.; Resources, F.M.A. and C.E.; Data Curation, A.O. and F.M.A.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, F.M.A., I.R.M. and J.J.I.; Writing—Review And Editing, J.J.I., I.R.M., C.E. and J.M.C.; Visualization, A.O. and F.M.A.; Supervision, I.R.M. and C.E.; Project Administration, J.M.C.; Funding Acquisition, I.R.M., J.M.C. and C.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by Agencia Estatal de Investigación (PID2022-137437OB-I00, PREP2022-000767) and Gobierno de Navarra (PC24-DEPLOC-012-002-015 DEPLOC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Osgood, R.; Meng, X. Principles of Photonic Integrated Circuits; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifante, G. Integrated Photonics: Fundamentals; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wosinski, L.; Thylén, L. Integrated Photonics in the 21st Century. Photonics Res. 2014, 2, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.H. Refractive Index of Silicon and Germanium and Its Wavelength and Temperature Derivatives. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1980, 9, 561–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, S.Y.; Li, B.; Gao, F.; Zheng, H.Y.; Zhang, W.; Guo, P.; Xie, S.W.; Song, A.; Dong, B.; Luo, L.W.; et al. Review of Silicon Photonics Technology and Platform Development. J. Light. Technol. 2021, 39, 4374–4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazanskiy, N.L.; Khonina, S.N.; Butt, M.A. Advancement in Silicon Integrated Photonics Technologies for Sensing Applications in Near-Infrared and Mid-Infrared Region: A Review. Photonics 2022, 9, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Ranade, R.; Swami Mathad, G.; Karouta, F. A Practical Approach to Reactive Ion Etching. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2014, 47, 233501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.Q.; Colli, A.; Fasoli, A.; Luo, J.K.; Flewitt, A.J.; Ferrari, A.C.; Milne, W.I. Deep Reactive Ion Etching as a Tool for Nanostructure Fabrication. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B Microelectron. Nanometer Struct. Process. Meas. Phenom. 2009, 27, 1520–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, J.O.; Martin, P.M. Chemical Vapor Deposition. In Handbook of Deposition Technologies for Films and Coatings: Science, Applications and Technology; William Andrew: Norwich, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 314–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.M. Atomic Layer Deposition: An Overview. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldada, L.; Shacklette, L.W. Advances in Polymer Integrated Optics. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2000, 6, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M. Low-Loss Polymeric Materials for Passive Waveguide Components in Fiber Optical Telecommunication. Opt. Eng. 2002, 41, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Bilotti, E.; Bastiaansen, C.W.M.; Peijs, T. Transparent Semi-Crystalline Polymeric Materials and Their Nanocomposites: A Review. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2020, 60, 2351–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Bai, T.; Liu, W.; Li, M.; Zang, Q.; Ye, C.; Sun, J.Z.; Shi, Y.; Ling, J.; Qin, A.; et al. All-Organic Polymeric Materials with High Refractive Index and Excellent Transparency. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangel, R.; Horst, F.; Jubin, D.; Meier, N.; Weiss, J.; Offrein, B.J.; Swatowski, B.W.; Amb, C.M.; Deshazer, D.J.; Weidner, W.K. Development of Versatile Polymer Waveguide Flex Technology for Use in Optical Interconnects. J. Light. Technol. 2013, 31, 3915–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Lu, R.; Yang, Q.; Song, E.; Jiang, H.; Ran, Y.; Guan, B.O. Flexible Wearable Optical Sensor Based on Optical Microfiber Bragg Grating. J. Light. Technol. 2023, 41, 1858–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Tong, L. Finger-Skin-Inspired Flexible Optical Sensor for Force Sensing and Slip Detection in Robotic Grasping. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2021, 6, 2100285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathish, K.; Kumar, S.S.; Magal, R.T.; Selvaraj, V.; Narasimharaj, V.; Karthikeyan, R.; Sabarinathan, G.; Tiwari, M.; Kassa, A.E. A Comparative Study on Subtractive Manufacturing and Additive Manufacturing. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 6892641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, S.T.; Zhu, Z.; Dhokia, V.; Shokrani, A. Process Planning for Additive and Subtractive Manufacturing Technologies. CIRP Ann. 2015, 64, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzesik, W. Hybrid Additive and Subtractive Manufacturing Processes and Systems: A Review. J. Mach. Eng. 2018, 18, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, H.N.; Hocken, R.J.; Tosello, G. Replication of Micro and Nano Surface Geometries. CIRP Ann. 2011, 60, 695–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, V.; Chester, S.A.; Ames, N.M.; Anand, L. A Thermo-Mechanically-Coupled Large-Deformation Theory for Amorphous Polymers in a Temperature Range Which Spans Their Glass Transition. Int. J. Plast. 2010, 26, 1138–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, E.; Rathi, R.; Misharwal, J.; Sinhmar, B.; Kumari, S.; Dalal, J.; Kumar, A. Evolution in Lithography Techniques: Microlithography to Nanolithography. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pease, R.F.; Chou, S.Y. Lithography and Other Patterning Techniques for Future Electronics. Proc. IEEE 2008, 96, 248–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, B.D.; Xu, Q.; Stewart, M.; Ryan, D.; Willson, C.G.; Whitesides, G.M. New Approaches to Nanofabrication: Molding, Printing, and Other Techniques. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 1171–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, D.P. Advances in Patterning Materials for 193 nm Immersion Lithography. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 321–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, W.H. Trends and Frontiers of MEMS. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2007, 136, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Zhang, X.; Sutherland, D.; Bochenkov, V.; Deng, S. Nanofabrication of Nanostructure Lattices: From High-Quality Large Patterns to Precise Hybrid Units. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2024, 6, 062004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Okazaki, S. Pushing the Limits of Lithography. Nature 2000, 406, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, C.A. The New, New Limits of Optical Lithography. In Proceedings of the SPIE, Volume 5374, Emerging Lithographic Technologies VIII, Santa Clara, CA, USA, 22–27 February 2004; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, S. Resolution Limits of Optical Lithography. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B Microelectron. Nanometer Struct. Process. Meas. Phenom. 1991, 9, 2829–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, Y.; Yano, K.; Itoh, M.; Ito, M. Chapter 13 Photolithography. In Flat Panel Display Manufacturing; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 287–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Xia, Y.; Black, A.J.; Whitesides, G.M. Photolithography with Transparent Reflective Photomasks. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B Microelectron. Nanometer Struct. Process. Meas. Phenom. 1998, 16, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.Y.; Hsieh, H.; Lee, Y.C. Contact Photolithography at Sub-Micrometer Scale Using a Soft Photomask. Micromachines 2019, 10, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, K.; Willson, C.G.; Lin, B.J. Ultrafast High-Resolution Contact Lithography with Excimer Lasers. IBM J. Res. Dev. 1982, 26, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawata, H.; Carter, J.M.; Yen, A.; Smith, H.I. Optical Projection Lithography Using Lenses with Numerical Apertures Greater than Unity. Microelectron. Eng. 1989, 9, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, M. Projection Optical Lithography. Mater. Today 2005, 8, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doise, J.; Bekaert, J.; Chan, B.T.; Hori, M.; Gronheid, R. Via Patterning in the 7-nm Node Using Immersion Lithography and Graphoepitaxy Directed Self-Assembly. J. Micro/Nanolithography MEMS MOEMS 2017, 16, 023506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.J. Making Lithography Work for the 7-nm Node and beyond in Overlay Accuracy, Resolution, Defect, and Cost. Microelectron. Eng. 2015, 143, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Kumar, A. Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography: A Review. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B Microelectron. Nanometer Struct. Process. Meas. Phenom. 2007, 25, 1743–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirati, A.; Peeters, R.; Smith, D.; Lok, S.; Martijn, V.N.; Noordenburg, M.; Roderik, V.E.; Verhoeven, E.; Meijer, H.; Minnaert, A.; et al. EUV Lithography Performance for Manufacturing: Status and Outlook. In Proceedings of the SPIE Volume 9776, Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) Lithography VII, San Jose, CA, USA, 21–25 February 2016; pp. 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y. A Photolithography Process Design for 5 nm Logic Process Flow. J. Microelectron. Manuf. 2019, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Suzuki, K. Microlithography: Science and Technology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781315219554. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.; Kim, T.; Lee, D.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, W.; Kim, E.; Jin, Y.; Lee, T.E. Practical Reinforcement Learning for Adaptive Photolithography Scheduler in Mass Production. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2024, 37, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, A.; Azzouz, R.; Laipple, G.; Kabak, K.E.; Heavey, C. Optimizing Capacity Allocation in Semiconductor Manufacturing Photolithography Area–Case Study: Robert Bosch. J. Manuf. Syst. 2020, 54, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Barrio, J.; Sánchez-Somolinos, C. Light to Shape the Future: From Photolithography to 4D Printing. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2019, 7, 1900598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Campo, A.; Greiner, C. SU-8: A Photoresist for High-Aspect-Ratio and 3D Submicron Lithography. J. Micromechanics Microengineering 2007, 17, R81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, K.K.; Wong, W.H.; Pun, E.Y.B. Polymeric Optical Waveguides Using Direct Ultraviolet Photolithography Process. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process 2005, 80, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, T.; Ouyang, X.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, A.P. Fabrication of Polymer Optical Waveguides by Digital Ultraviolet Lithography. J. Light. Technol. 2022, 40, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Zhang, K.; Wu, J.; Wong, D.S.H.; Feng, Q.; Bian, L.; Zhang, A.P. Optical Μ-Printing of Cellular-Scale Microscaffold Arrays for 3D Cell Culture. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, T.; Kim, C.S.; Kim, K.; Choi, J.-r. Emerging Applications of Digital Micromirror Devices in Biophotonic Fields. Opt. Laser Technol. 2018, 104, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.H.; Kang, J.W.; Kim, J.J. Direct Pattering of Polymer Optical Waveguide Using Liquid State UV-Curable Polymer. Macromol. Res. 2006, 14, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, K.S. Development of Optical Polymer Waveguide Devices. In Proceedings of the SPIE Volume 7605, Optoelectronic Integrated Circuits XII, San Jose, CA, USA, 23–28 January 2010; pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, C.F.; Krchnavek, R.R. Benzocyclobutene Optical Waveguides. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 1995, 7, 535–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, K.S.; Lor, K.P.; Liu, Q.; Chan, H.P. UV-Written Buried Waveguides in Benzocyclobutene. In Proceedings of the SPIE Volume 6351, Passive Components and Fiber-based Devices III, Gwangju, Republic of Korea, 3–7 September 2006; pp. 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lor, K.P.; Chiang, K.-S.; Liu, Q.; Chan, H.P. Ultraviolet Writing of Buried Waveguide Devices in Epoxy-Coated Benzocyclobutene. Opt. Eng. 2009, 48, 044601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Shen, Y. Laser Direct Writing System and Its Lithography Properties. In Proceedings of the SPIE Volume 3550, Laser Processing of Materials and Industrial Applications II, Beijing, China, 16–19 September 1998; pp. 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pease, R.F.W. Electron Beam Ilthography. Contemp. Phys. 1981, 22, 265–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altissimo, M. E-Beam Lithography for Micro-/Nanofabrication. Biomicrofluidics 2010, 4, 026503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anscombe, N. Direct Laser Writing. Nat. Photonics 2010, 4, 22–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.L.; Qi, Y.N.; Yin, X.J.; Yang, X.; Chen, C.M.; Yu, J.Y.; Yu, J.C.; Lin, Y.M.; Hui, F.; Liu, P.L.; et al. Polymer-Based Device Fabrication and Applications Using Direct Laser Writing Technology. Polymers 2019, 11, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, M.; Wegener, M.; Mueller, P. 3D Direct Laser Writing Using a 405 nm Diode Laser. Opt. Lett. 2014, 39, 6847–6850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, J.C.; Schianti, J.N.; Almeida, M.G.; Pavani, A.; Panepucci, R.R.; Hernandez-figueroa, H.E.; Gabrielli, L.H.; Melikyan, A.; Alloatti, L.; Muslija, A.; et al. Low-Loss Modified SU-8 Waveguides by Direct Laser Writing at 405 nm. Opt. Mater. Express 2017, 7, 2651–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Krishnaswamy, S. Direct Laser Writing Polymer Micro-Resonators for Refractive Index Sensors. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2016, 28, 2819–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnaswamy, S.; Wei, H. Polymer Micro-Ring Resonator Integrated with a Fiber Ring Laser for Ultrasound Detection. Opt. Lett. 2017, 42, 2655–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broers, A.N.; Hoole Andrew, A.C.F.; Ryan, J.M. Electron Beam Lithography—Resolution Limits. Microelectron. Eng. 1996, 32, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broers, A.N. Resolution Limits for Electron-Beam Lithography. IBM J. Res. Dev. 1988, 32, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, D.R.S.; Thoms, S.; Beaumont, S.P.; Weaver, J.M.R. Fabrication of 3 nm Wires Using 100 KeV Electron Beam Lithography and Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) Resist. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1996, 68, 322–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manheller, M.; Trellenkamp, S.; Waser, R.; Karthäuser, S. Reliable Fabrication of 3 nm Gaps between Nanoelectrodes by Electron-Beam Lithography. Nanotechnology 2012, 23, 125302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Pandraud, G.; Zhang, Y.; French, P. Single-Mode Tapered Vertical SU-8 Waveguide Fabricated by E-Beam Lithography for Analyte Sensing. Sensors 2019, 19, 3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Paloczi, G.T.; Yariv, A.; Zhang, C.; Dalton, L.R. Fabrication and Replication of Polymer Integrated Optical Devices Using Electron-Beam Lithography and Soft Lithography. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 8606–8613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.H.; Zhou, J.; Pun, E.Y.B. Low-Loss Polymeric Optical Waveguides Using Electron-Beam Direct Writing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2001, 78, 2110–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehagias, N.; Zankovych, S.; Goldschmidt, A.; Kian, R.; Zelsmann, M.; Torres, C.M.S.; Pfeiffer, K.; Ahrens, G.; Gruetzner, G. Embedded Polymer Waveguides: Design and Fabrication Approaches. Superlattices Microstruct. 2004, 36, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, R.E.; Mao, X.L.; Yoo, J.; Gonzalez, J.J. Laser Ablation. In Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 41–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafe, M.; Marcu, A.; Puscas, N.N. Pulsed Laser Ablation of Solids; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Darwish, S.; Alahmari, A.M. Laser Ablation and Laser-Hybrid Ablation Processes: A Review. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2016, 31, 1121–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi-Kumar, S.; Lies, B.; Lyu, H.; Qin, H. Laser Ablation of Polymers: A Review. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 34, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Steenberge, G.; Hendrickx, N.; Bosman, E.; Van Erps, J.; Thienpont, H.; Van Daele, P. Laser Ablation of Parallel Optical Interconnect Waveguides. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2006, 18, 1106–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakariyah, S.S.; Conway, P.P.; Hutt, D.A.; Selviah, D.R.; Wang, K.; Baghsiahi, H.; Rygate, J.; Calver, J.; Kandulski, W. Polymer Optical Waveguide Fabrication Using Laser Ablation. In Proceedings of the 11th Electronic Packaging Technology Conference EPTC, Singapore, 9–11 December 2009; pp. 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizarraga-Medina, E.G.; Castillo, G.R.; Jurado, J.A.; Caballero-Espitia, D.L.; Camacho-Lopez, S.; Contreras, O.; Santillan, R.; Marquez, H.; Tiznado, H. Optical Waveguides Fabricated in Atomic Layer Deposited Al2O3 by Ultrafast Laser Ablation. Results Opt. 2021, 2, 100060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, S.S.; Goswami, A. Hot Embossing of Polymers—A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 26, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, S.S.; Goswami, A. Recent Developments in Hot Embossing—A Review. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2021, 36, 501–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckele, M.; Bacher, W.; Müller, K.D. Hot Embossing—The Molding Technique for Plastic Microstructures. Microsyst. Technol. 1998, 4, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velten, T.; Bauerfeld, F.; Schuck, H.; Scherbaum, S.; Landesberger, C.; Bock, K. Roll-to-Roll Hot Embossing of Microstructures. Microsyst. Technol. 2011, 17, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Wu, H.; Shu, Y.; Yi, P.; Deng, Y.; Lai, X. Roll-to-Roll Hot Embossing System with Shape Preserving Mechanism for the Large-Area Fabrication of Microstructures. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2016, 87, 105120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y. Applications of Nanoimprint Lithography/Hot Embossing: A Review. Appl. Phys. A 2015, 121, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unno, N.; Mäkelä, T. Thermal Nanoimprint Lithography—A Review of the Process, Mold Fabrication, and Material. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.Y.; Krauss, P.R.; Renstrom, P.J. Imprint of Sub-25 nm Vias and Trenches in Polymers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1995, 67, 3114–3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooy, N.; Mohamed, K.; Pin, L.T.; Guan, O.S. A Review of Roll-to-Roll Nanoimprint Lithography. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]