Abstract

This paper discusses the Internet of Things (IoT) and the security challenges associated with it. IoT is a network of interconnected devices that share information. However, the low power and resources of IoT devices make them vulnerable to attacks. Using heavy protocols like HTTP for IoT devices can prove costly and using popular lightweight protocols like CoAP can invite attacks such as DoS (Denial-of-Service). While security models such as DTLS and LSPWSN can secure IoT against such attacks, they also have limitations. To overcome this problem, this paper proposes a machine learning model that detects DoS amplification attacks against CoAP with 99% accuracy. To the best of our knowledge, this research is the first to use the multi-classification process to detect and classify the different types of the DoS amplification techniques that attack CoAP client use against victim CoAP clients.

1. Introduction

The Internet of Things is a new technology in networking that consists of tiny devices connected either to a local network or to the internet [1]. These devices can interact with each other with or without human interference. This connectivity is enabled using sensors that are installed upon devices like temperature sensors, smoke detector sensors, and security cameras. Researchers expect the growing number of IoT devices to reach a total of 75 billion IoT devices by 2025 [2]. Therefore, IoT networks will have a significant role in different domains such as smart cities and healthcare [3]. The IoT network consists of three basic layers, namely, the perception layer, the network layer, and the application layer. The perception layer takes the role of sensing the environment, whereas the network layer is responsible for exchanging the data between the IoT devices. As for the application layer, it helps in creating smart environments and a hybrid metaheuristic algorithm that facilitates the problem of feature selection for classification problems based on a lucid and efficient algorithm geared towards optimizing and striking a balance between the number of features selected and accuracy [4]. There are a lot of protocols that are used in IoT network communications. This paper focuses on one particular application layer protocol, the CoAP (Constrained Application Protocol). The CoAP has a significant role in the IoT network due to its lightness, simplicity, mobility, and portability for low-power and low-resource devices as compared to other protocols such as Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) and Advanced Message Queuing Protocol (AMQP) [5]. However, this also makes the CoAP a preferred target for Denial-of-Service attacks. The Denial-of-Service attack aims to overwhelm the target victim with a massive number of messages or requests and thereby make it unavailable for legitimate users. One major type of the Denial-of-Service attack is the amplification attack. In this attack, the attacker spoofs the IP address of the victim client and requests large messages from the server. Several existing techniques can be used to secure the CoAP against DoS attacks such as employing the DTLS protocol. However, DTLS is a heavy protocol since it relies on the TCP three-way handshake that can consume the IoT energy; moreover, DTLS is not designed for lower resource and constrained devices [5]. So, this study aims to clarify the different categories of amplification attacks that target the CoAP protocol. For this purpose, a dataset is generated using simulated attacks on CoAP. The lower levels of communication protocols such as the UDP are out of the scope of this study, and the focus remains on the application layer where the CoAP operates. The motivation for building the detection system on the application layer is rooted in the assumption that it is beneficial to build the detection system near the victim, whereas the defending system should be near the attacker [6]. Finally, we build a machine learning model that can classify each category of the amplification attacks (simple amplification, observe amplification, and multicast amplification). The generated dataset contains around 120,000 CoAP packets, and, of which, half are benign, and half are malware (one-third for each category). The proposed model is capable of detecting and classifying the attacks with an accuracy of 99% using the Gradient Boosting algorithm. To sum it up, the main contribution and the research objectives are as follows:

RO 1: Identify and simulate the DoS amplification attacks that target CoAP;

RO 2: Generate a categorized dataset of the DoS amplification attacks that target CoAP;

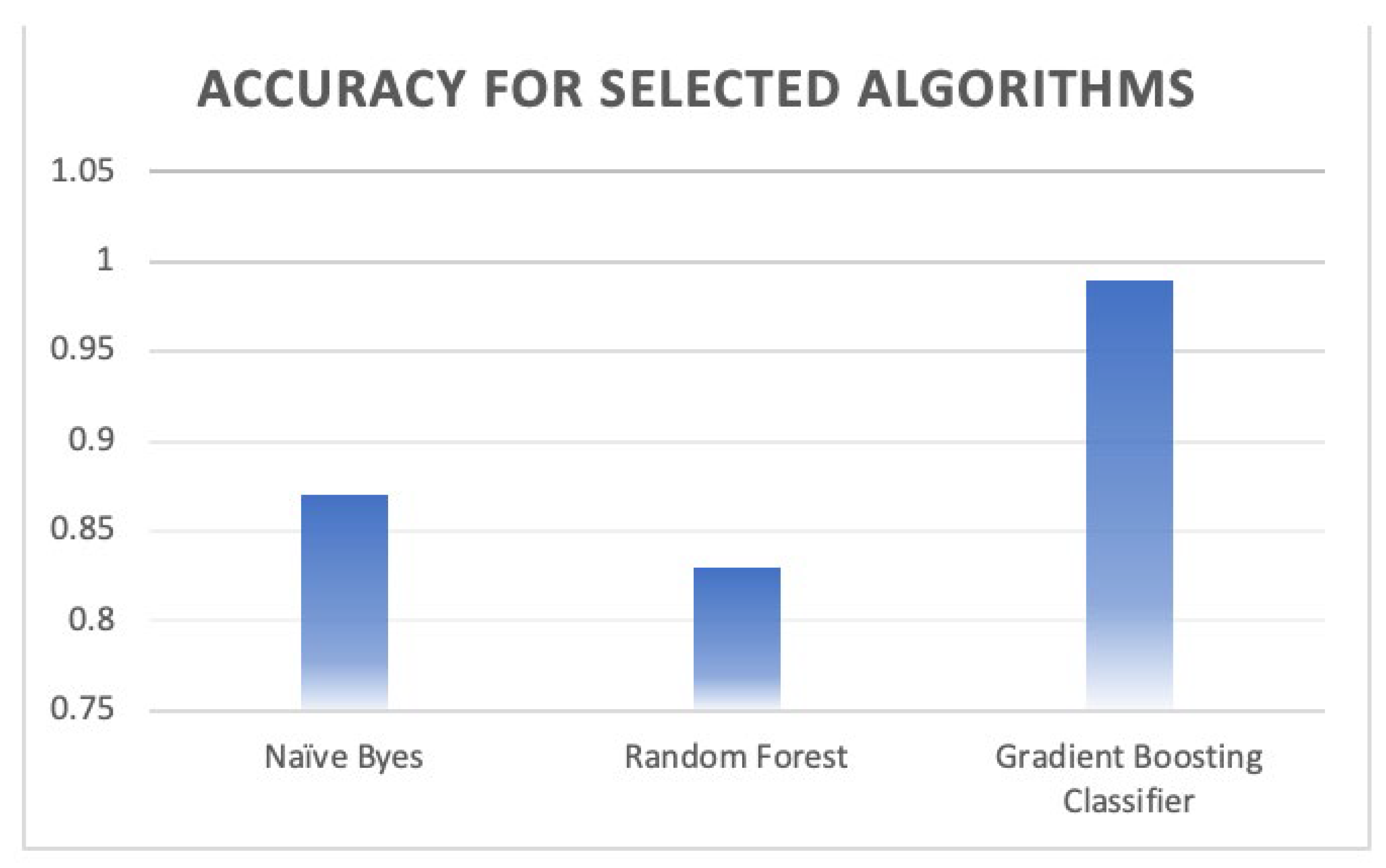

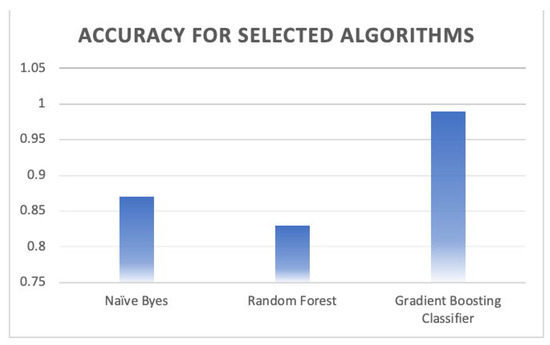

RO 3: Test three machine learning classifiers (Naïve Byes, Random Forest, and Gradient Boosting) to perform multi-classification for the amplification attacks.

To the best of our knowledge, this paper is the first to conduct multi-classification of DoS amplification attacks on CoAP. This paper is structured as follows. Section 1 presents the CoAP protocol overview and the CoAP security overview, Section 2 reviews existing literature, Section 3 demonstrates the methods that have been employed, Section 4 illustrates the results, and finally, Section 5 presents the conclusion and recommendations for future research.

1.1. IoT-CoAP Overview

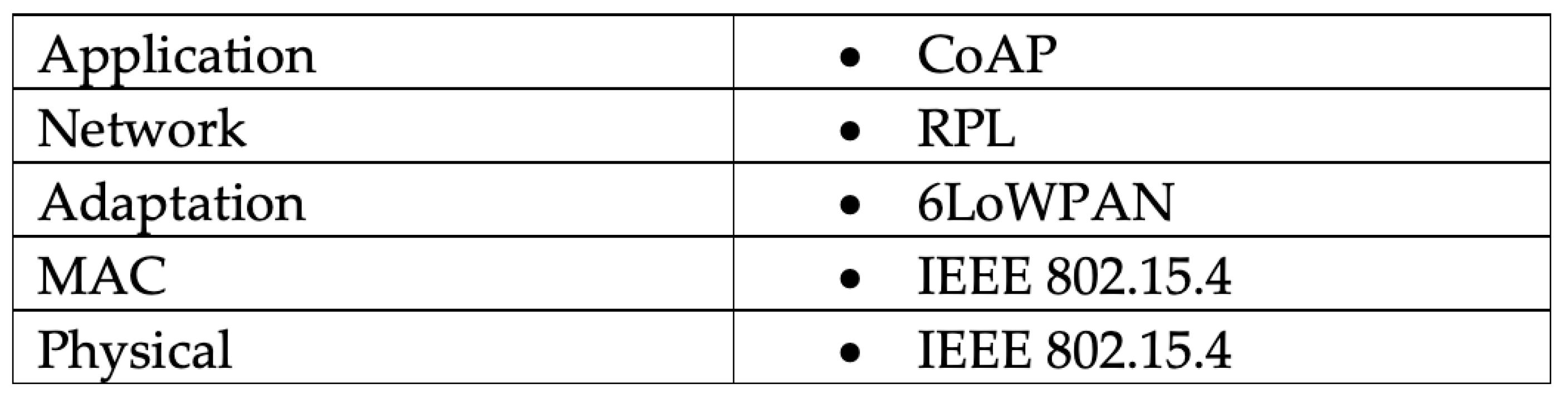

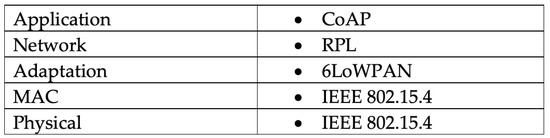

The Constrained Application Protocol (CoAP) is a web transfer protocol that follows Representational State Transfer (REST) to receive and deliver messages as most of the web services (web APIs) on the internet depend on the REST architecture [7]. The CoAP protocol operates over the application layer in the IoT network as depicted in Figure 1, and it is becoming increasingly important for the CoAP to meet the requirements for designing a generic web protocol that fits the low-resource and low-energy devices and machine-to-machine (M2M) applications such as smart city [7].

Figure 1.

Layers and protocols of IoT network.

1.2. CoAP Architecture

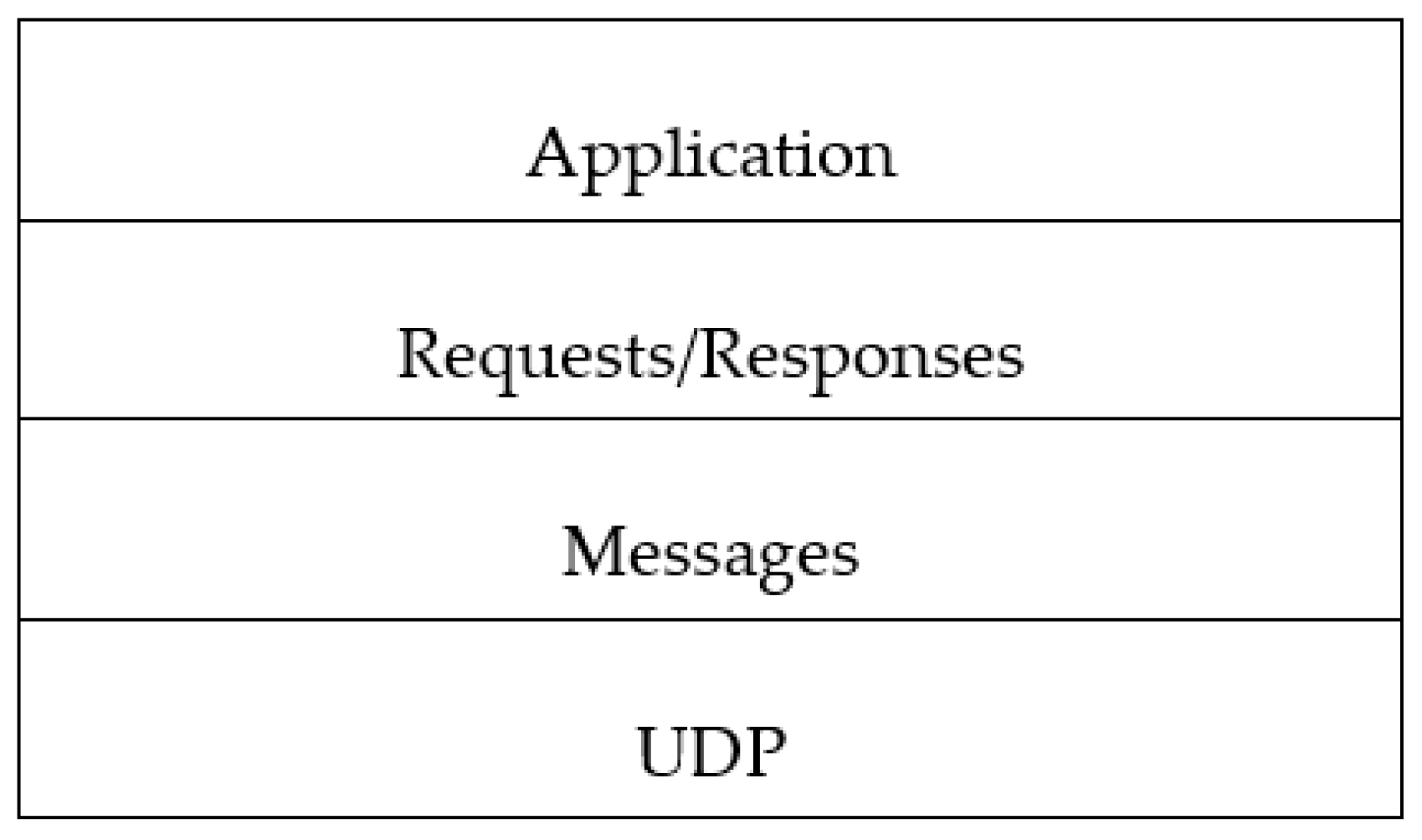

CoAP consists of four layers with the first from bottom being the user datagram protocol (UDP). The second layer is the request/response layer, and the third layer is messaging layer that offers optional reliability of messages (confirmable, non-confirmable). Those layers are depicted in Figure 2, and each layer has a role in exchanging messages between the two endpoints. The topmost layer is the application layer where the CoAP protocol operates.

Figure 2.

CoAP architecture [7].

1.3. CoAP Security Overview

The DTLS is a security protocol that is used to secure the CoAP protocol. DTLS is a heavy protocol since it uses the three-way handshake process like the TCP protocol to authenticate the messages and as such is not a good fit for IoT devices [2]. CoAP defines four-security mode which are as follows:

- A.

- NoSec Mode: The DTLS is not deployed in this mode assuming that the lower layers will take the role of securing the messages. This paper assumes that the CoAP is in the NoSec mode while trying to find an alternative way to secure the CoAP clients against the CoAP amplification attacks instead of using the DTLS protocol. This paper’s target is to secure the CoAP in its vicinity, and the NoSec mode is the default mode for this work.

- B.

- PresharedKey Mode: In this mode, the DTLS is deployed, and for each key, there is a list of nodes that appear to engage in communication. So, every endpoint has its own key, and if it is within a group of nodes, it is authenticated within that group using pre-shared keys.

- C.

- RawPublicKey Mode: The DTLS is also deployed in this mode. If an endpoint requires authentication, a symmetric key is generated for all endpoints to avoid the need for a certificate.

- D.

- Certificate Mode: In this mode, the DTLS is deployed, and a symmetric key pair is generated for each endpoint. The certificate authority is responsible for ensuring the validity of each endpoint.

Denial-of-Service Attacks against CoAP

The CoAP like many other protocols is a potential target of Denial-of-Service attacks. This attack aims to cause a downtime in the service and make the service unavailable for legitimate use. One of the Denial-of-Service attacks that target the CoAP is the so-called CoAP amplification. The amplification attack sends unwanted messages to a target victim by spoofing its IP. These messages are large and, therefore, are called amplification. Most of the state-of-the-art techniques used to secure the CoAP protocol aim to secure the server side. This research, however, focusses on the amplification that comes from the CoAP client against another CoAP victim client. The amplification attack can be DoS (Denial-of-Service) or DDoS (Distributed Denial-of-Service) based on the source of the attack. In the case of DoS, only a single endpoint is used to initiate massive requests or responses to the target victim that causes heavy processing to overwhelm the resources of the victim and make it unavailable for legitimate users. On the other hand, DDoS is launched from multiple sources instead of a single endpoint. The amplification factor for the amplification attacks can be calculated based on the ratio between the data generated by the attacker and the actual data sent to the victim [8]. So, the attacks described below are based on two scenarios: single or massive requests sent by the attacker and single or massive responses received by the victim. In a DoS attack scenario, the CoAP server is forced to send a massive amount of data. However, the amplification attacks are initiated side by side with the IP address spoofing of the victim. Consequently, the attacker becomes capable of generating more requests from multiple sources to the victim and multiplying the traffic that results in a DDoS amplification attack. The CoAP NoSec mode is vulnerable to IP address spoofing. The amplification attacks can be classified as follows:

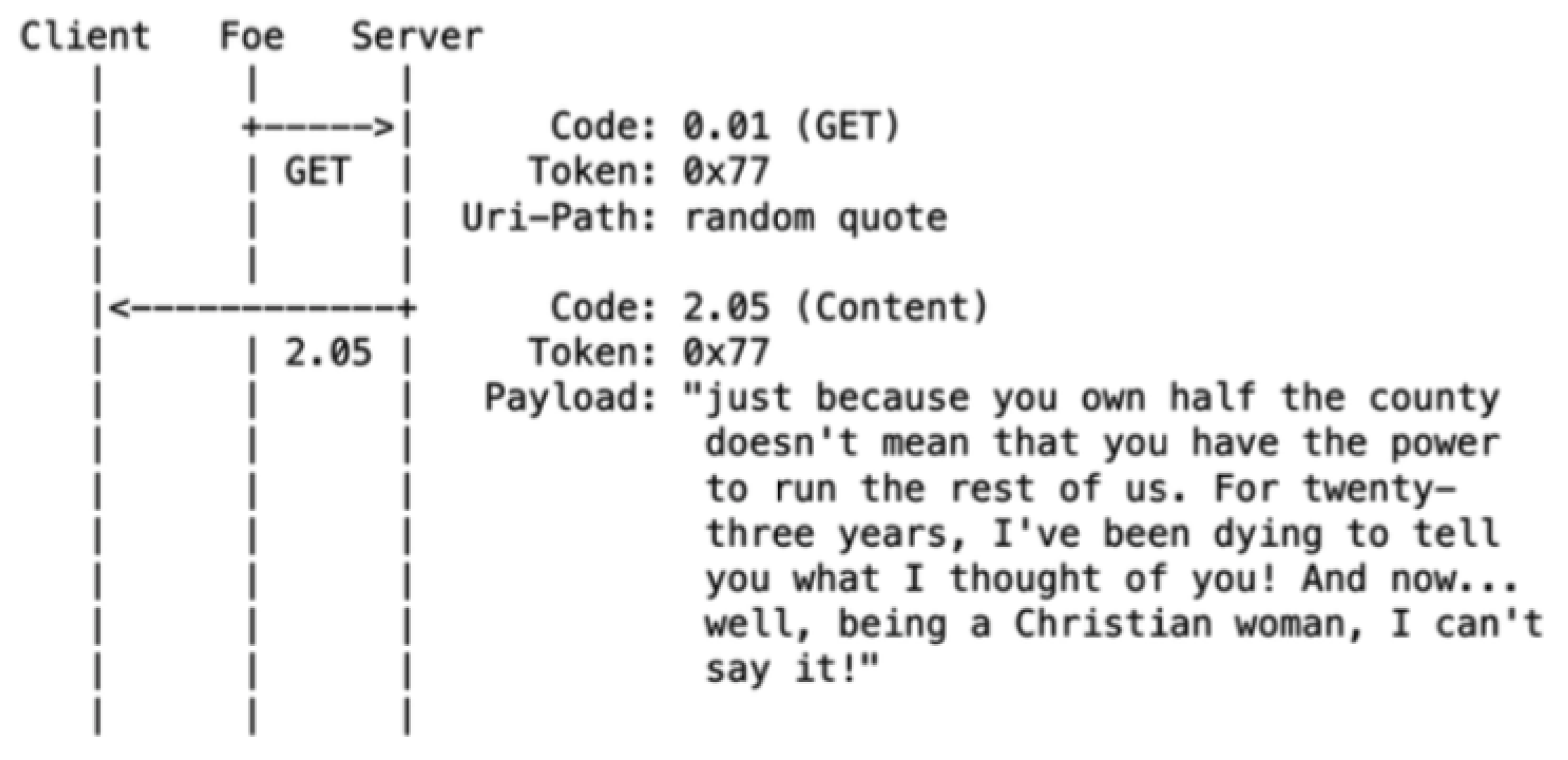

- 1. Simple Amplification Attack

In this scenario, the attacker is forcing the CoAP server to respond x times to a single request. If the responses are x times larger than the request, so:

By default, CoAP can handle up to 1024 bytes for every request [7]. So, the attacker sends a message that exceeds 1024 bytes. Figure 3 illustrates the amplification attack using a single response. This attack can only succeed if the victim CoAP client’s IP is successfully spoofed.

Figure 3.

Simple amplification against the CoAP.

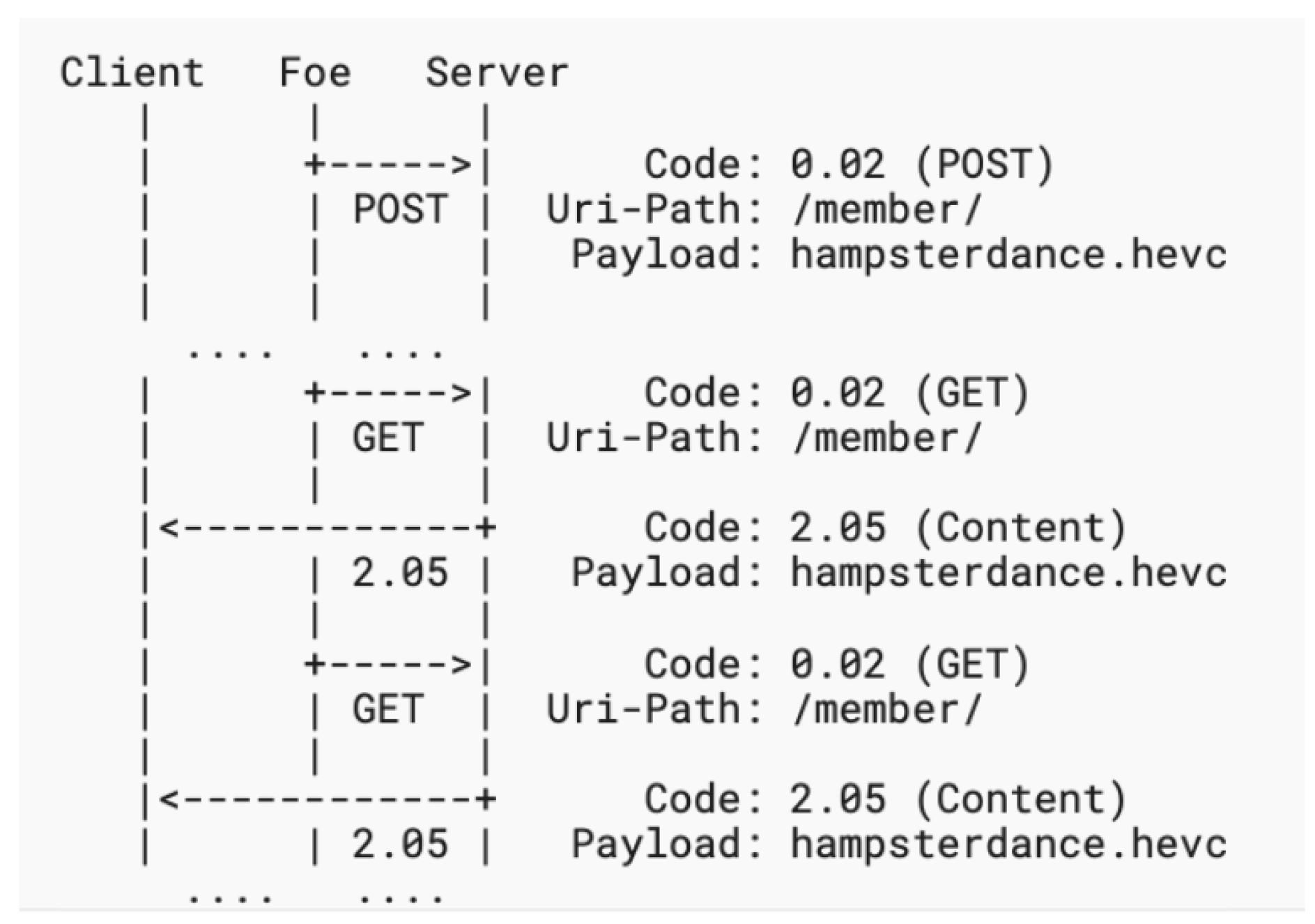

The attacker can customize the amplification factor to a fixed number by increasing the GET requests to the target victim. This can be done by updating the resources used in the attack. Figure 4 illustrates this scenario.

Figure 4.

Amplification Attack using multiple requests and customized amplification factor.

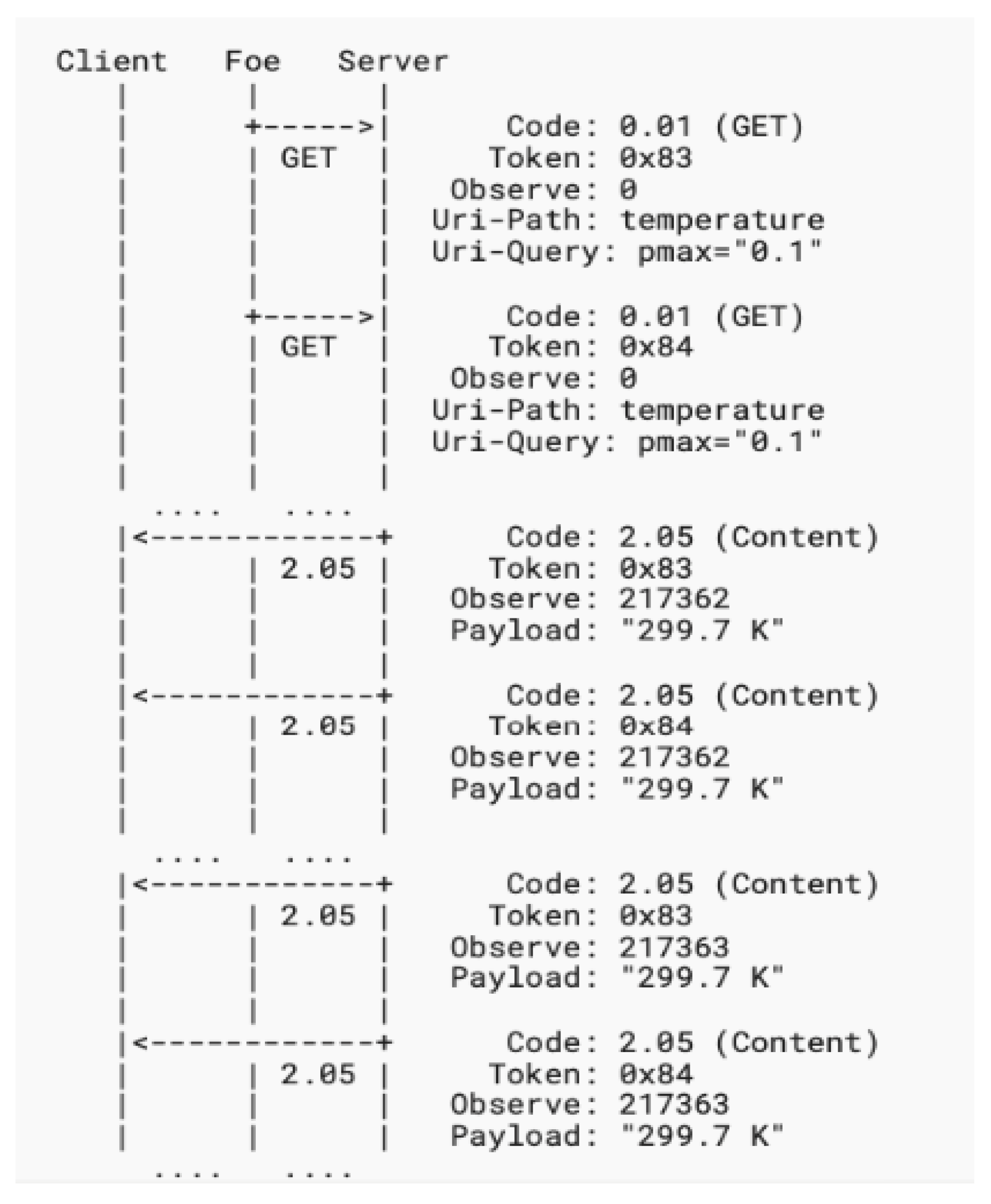

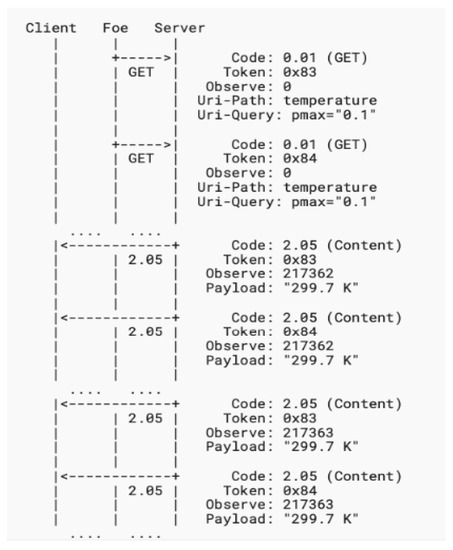

- 2. Amplification Attack Using Observe

This attack implementation is based on a single request that seeks multiple responses from different servers. For instance, a single request can have 10 times the number of responses from multiple servers as depicted in Figure 5. The amplification factor of this scenario is much worse than the amplification using a single response. The limitation of this attack is that if different CoAP servers have the same filtering method of the packets, it will not be able to get the same responses from multiple CoAP servers. Assuming that a dedicated request x is responded to by the server with response y, so the amplification factor can be calculated as:

Figure 5.

Amplification Attack using observe.

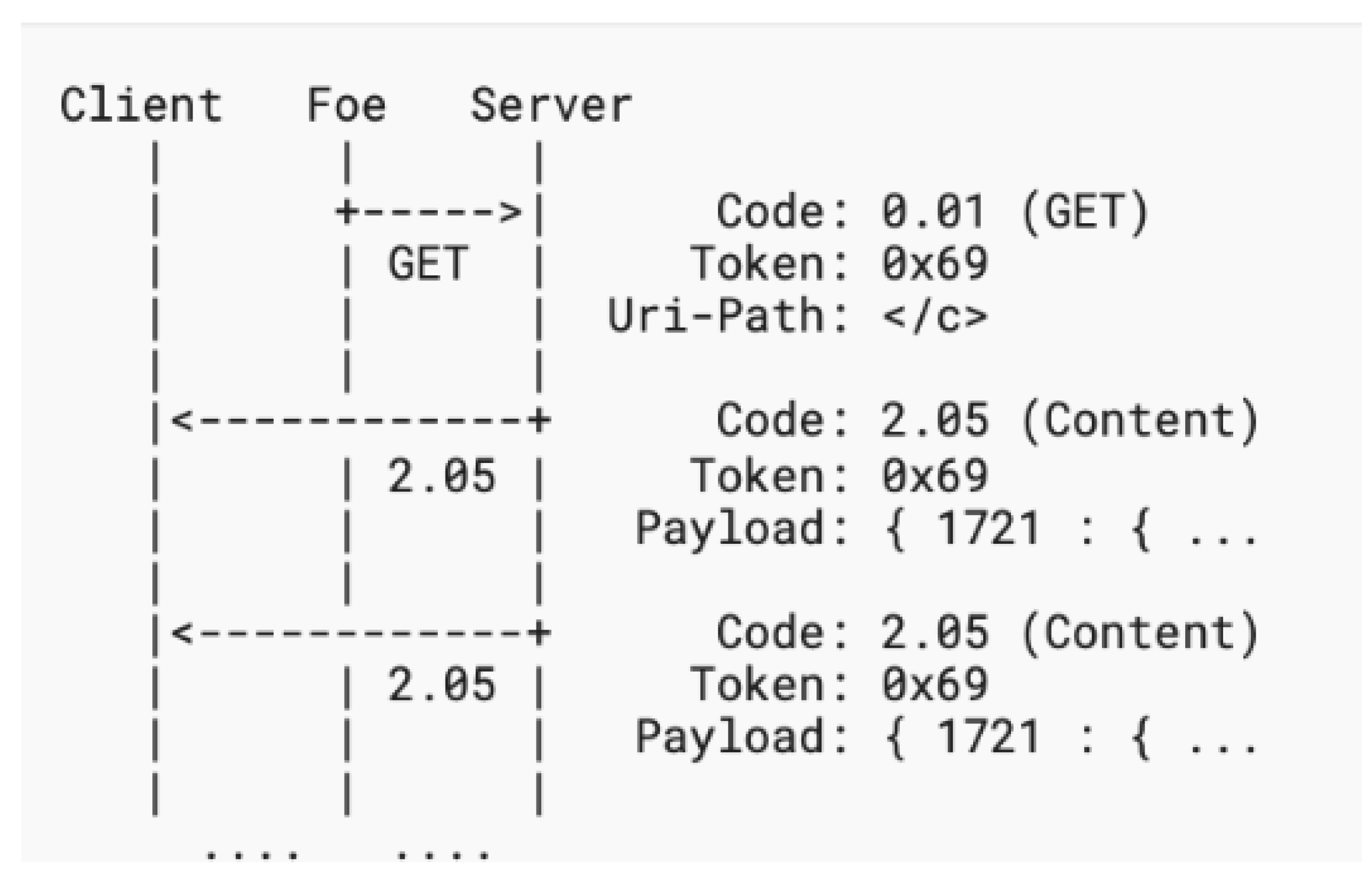

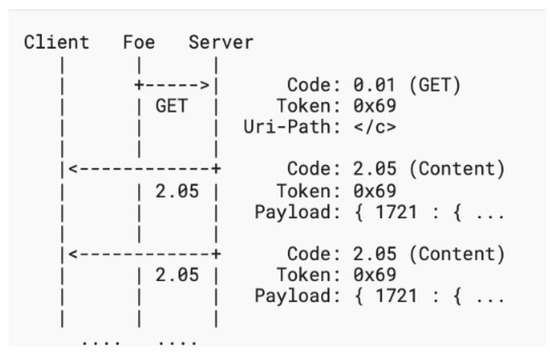

- 3. Amplification Attack Using Multicast

Multicast amplification is defined as a group of requests that are sent to multiple servers using multicast or broadcast where each request x results in y responses coming from multiple z servers. This attack is meant to incapacitate the CoAP victim clients. The number of CoAP victim clients in this attack is unknown and so is the number of servers that respond to fake requests. The amplification factor of this attack can be calculated as:

The attack is worsened since the number of z servers is not determined. Figure 6 demonstrates this attack scenario.

Figure 6.

Amplification attack using multicast.

2. Related Work

Securing the CoAP against DoS and DDoS has been extensively researched. Some research is based on the DTLS and enhanced DTLS for the CoAP security [9,10,11,12]. However, DTLS was originally designed to protect web applications and is considered a heavy protocol that does not work well with IoT devices [10]. Software Defined Networking (SDN) has also been used to detect DDoS attacks against CoAP [9]. The authors provided two modules for the detection phase: the first module is to monitor the system and realize the anomalies between packets, and the second is to apply a machine learning algorithm to determine the DDoS packets. In [13], the authors compare different classifiers to detect the CoAP DDoS attacks and state that the support vector machine (SVM) algorithm outperformed Naïve Byes, decision tree, and Random Forest with an accuracy of 99.88%. This paper only discussed the binary classification but not the multi-classification of the DDoS CoAP attacks. The anomaly detection of DDoS CoAP attacks was presented in [14]. This work claims an accuracy of 93% for classifying the malware. This research was confined to the attacks that target the CoAP server and did not cover attacks launched by CoAP clients against each other. The following section reviews the research that discussed DDoS attacks against IoT network.

2.1. Proposed Defense Mechanisms for IoT Network

Several defense mechanisms have been proposed to protect IoT networks from DDoS attacks. These mechanisms can be categorized into Software-Defined Networking (SDN) methods and machine learning-based detection. In this section, some of these proposed mechanisms will be discussed in detail.

2.1.1. SDN Platform for IoT Network Security

Some researchers have deployed SDN as a platform to secure IoT networks. SDN is a new networking paradigm that brings different benefits such as ubiquitous accessibility, managing resources dynamically, flexible programmed interfaces, and extreme authority for the controller, which introduces the second generation of networking [15]. SDN consists of a separate control plane and a data plane. The basic operations and control of the network are centralized in the controller or distributed controllers. So, the SDN design has enhanced network security because all major network operations are visible to the controllers; thus, controllers have the authority to resolve any conflict. Mert Ozcelik et al. (2017) proposed to exploit the extreme functionalities and authorities of the SDN controller in the edge IoT networks such as traffic monitoring and dynamic rule updates to detect and mitigate IoT-based DDoS attacks [16]. The proposed method builds rules in the switches based on the discovered attack packets to blacklist and delete the attacks. The authors tested their system in a real-time environment, and the results indicate extreme effort in detecting Mirai attacks. Similarly, Yin et al. (2018) proposed a framework for IoT-based SDN that has distributed controller pool [17]. The system named SD-IoT uses cosine similarity of the vectors of the incoming packet and based on that it decides if a DDoS attack is triggered or not. This work employs a threshold-based cosine similarity, and if the threshold is exceeded, the system blocks the source of the attack. However, this work is susceptible to large amounts of traffic. Edge computing is also employed to defend IoT against DDoS attacks. Bhardwaj et al. (2018) developed a proactive defense while rendering the edge as the first line to counter DDoS attacks [6]. It is a cloud-based platform that uses ShadowNet employed at the edge nodes of the cloud architecture. Edge nodes will send the incoming packets for check purposes to the ShadowNet web service to assess whether the packet is benign or a DDoS attack packet. However, this approach is focused on speed and ignores accuracy because there is no way to differentiate between the attack and the Flash crowd. Stateful SDN architecture is used to develop an entropy-based solution to detect and mitigate IoT-DDoS attacks (Galeano-Brajones et al., 2020) [18]. The authors claim their results demonstrate the significant role of calculating the correlation of the entropy values for different extracted features in identifying the attacks. Furthermore, SDN is employed for mitigation by easily updating the switches’ flow tables with new entries. However, this system considers only limited types of DDoS attacks. Yang et al. (2019) claim that using the controller to defend the network against DDoS attacks is time-consuming and a waste of resources [19]. Alternatively, they consider the IoT traffic features and exploit the benefits of the concept of edge computing by putting the detection and mitigation system into the Open Flow (OF) switches of IoT. This results in a distribution of anomaly detection and avoids overloading the controller. They employ machine learning in the OF switches and gain around 99% precision. The demerit of this work is the lack of handling sophisticated DDoS attacks such as the Crossfire attack.

2.1.2. Machine Learning and Deep Learning for IoT Network Security

Several research have employed machine learning or deep learning methods to detect and mitigate IoT-DDoS attacks. Median Y. et al. (2018) developed an anomaly-based detection method for the IoT network [20]. The authors extracted the behavior for every benign traffic independently and used the deep autoencoders to capture the benign behavior of the IoT traffic. Then, the autoencoder attempted to compress snapshots, and if it failed to reconstruct the snapshot, it was considered an indication of anomalous behavior. They evaluated their method by injecting some IoT devices in the lab with popular malicious botnets (Mirai and BASHTILE) and demonstrated that their method can accurately and instantly detect the attacks launched from infected IoT devices. Ivan et al. (2019) proposed an anomaly-based DDoS attacks detection framework [21]. They classified the IoT devices and traffic into different classes. These classes helped analyze if traffic generated from a class is deviating from normal or expected behavior. These classes categorize the IoT devices, and the traffic generated from one class does not deviate from other traffic streams generated from the same class. To classify new IoT devices, Logistic Regression is employed to affiliate it to a dedicated class. Then, the Adaboost machine learning algorithm is used to measure the deviation of any traffic from normal behavior. Ultimately, all traffic behavior that deviated from the corresponding class were considered a DDoS attack. Hussain et al. (2019) claimed that recent IoT detection models are degraded due to model aging and the outdated dataset used for training [3]. In their work, they converted the network traffic into an image form, and then, they trained the state-of-the-art Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model named ResNet with the new form. The authors evaluated their work using the CICD2019 dataset that contains 11 types of DDoS attacks and gains an accuracy of 99.99% for the binary classification technique. A honeypot-based detection was also used to detect Zero-day attacks. According to Vishwakarma et al. (2019), a honeypot can help to detect new variants of IoT-DDoS attacks [22]. In their work, they lured the attacker by allowing him to invade the protection wall. Thereafter, the honeypot came into the picture and recorded the manipulations that the invader tends to do as log files. These log files were then transformed into a tabular format that made them work as a dataset. Then, they trained the machine learning on these log files after being formatted to get useful information about the attack. However, this work was not tested in a real-world environment. Soe Y. et al. (2019) employed Artificial Neural Network (ANN) to detect IoT-DDoS attacks [23]. The authors used the newly released dataset named Bot-IoT dataset. Due to the imbalance in the dataset that contains 1.9 million attack packets and 477 benign packets, they applied a technique called SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) to generate several benign packets equal to the number of DDoS packets. The detection system showed 100% accuracy. Dao N. et al. (2019) proposed MECshield, a framework, that employed mobile edge computing to protect the Heterogeneous IoT environment [24]. The framework used multiple intelligent filters and put them at the edge of the attack resource/destination. A centralized controller supervised the interactions of the smart filters and propagated the corresponding features of the attack to the smart filters. The authors tested their mechanism using three different datasets (CAIDA, NSL-KDD, and DARPA). The experiment showed impressive results in the detection accuracy, and the dilemma of the bottleneck, which was a crucial issue in DDoS attacks, was resolved by distributing the filters at multiple mobile edge points. Yizhen et al. (2020) proposed a detection system named FlowGuard that operated at the edge servers close to the IoT network [25]. FlowGuard vetted all packets passing through the edge server using a flow filter. They evaluated their work with CICDDoS2019 and other self-generated datasets and attained an accuracy of 98.8%.

2.1.3. Cloud Platform for IoT Network Security

Different works have also deployed cloud computing platforms to secure IoT networks. Due to the lack of protection of the IoT network from an insider attack on the SDN platform, cloud-based approaches have emerged. In SDN, edge and gateway routers are exploited for the deployment of the detection system and, thus, cannot handle attacks coming from a single device during the M2M communication (Conti et al., 2018) [15]. Weiqi et al. (2018) discuss the infrastructure-as-a-service (IaaS) that offers the network as a service, storage, and CPU for tenants, and then, the tenants outsource their infrastructure to, for example, Amazon and Microsoft Azure [26]. These outsourced infrastructures consist of virtual machines and are allocated to a certain tenant called Tenant Network (TN). The cloud administrator has full privileges on the TN but has no control over the physical infrastructure. For this reason, the authors proposed a TNGuard platform that restricts the administrator authorities. This results in degraded privileges for the administrator and should result in a secured tenant IoT network. The authors evaluate their work using: (1) the time the system requires to boot, (2) the average time for response, and (3) the rate of the cross-zone communication. All metrics show TNGuard is sufficient for most of the applications. However, this work lacks dynamic integrity verification. Djouani et al. (2018) proposed a framework to integrate SDN and cloud computing to secure IoT networks [27]. They separated the control plane and the data plane by putting the SDN controllers in the cloud and putting the data plane over the nodes and the gateways. The lack of resources in IoT was compensated by delegating the security mechanism to the cloud. This method was not tested in a real environment. Moreover, Fog computing integrated with SDN and blockchain were proposed by Muthanna et al. (2019) to secure IoT networks [28]. The authors leveraged the benefits of Fog computing such as minimizing latency in communication and helping with data offloading. Moreover, Fog computing renders new services more efficient. So, the authors came up with a layer of distributed edge computing-based Fog nodes, and it was located in the middle between IoT central cloud and different IoT nodes. They evaluated their work and claimed that their method is efficient in terms of computing resource utilization and latency. Table 1 summarizes the IoT defense mechanisms for DDoS attacks.

Table 1.

Proposed Defense Mechanisms for IoT Network.

In terms of dataset uniquity, there are different datasets available for DDoS CoAP attacks. The Bot-IoT [29] has a variety of attacks including DoS attacks; however, it does not include DoS CoAP amplification attacks. A NetFlow dataset was generated from UNSW-NB15, BoT-IoT, ToN-IoT, and CSE-CIC-IDS2018 due to the lack of related features for malware detection [30]. The authors claimed that most Network Intrusion Detection Systems (NIDS) datasets do not contain sufficient security events. For this purpose, they generated a new dataset from the NIDS datasets and included the security events for research purposes. This dataset does not have specific amplification malware for the DoS CoAP attacks. The IoT-Flock dataset [31] was generated for the IoT network attacks. However, this dataset was dedicated to healthcare applications. It can be safely assumed that no dataset has been generated by any researcher so far for simulating the DoS CoAP amplification attacks that contain simple, observe, and multicast amplification.

3. Materials and Methods

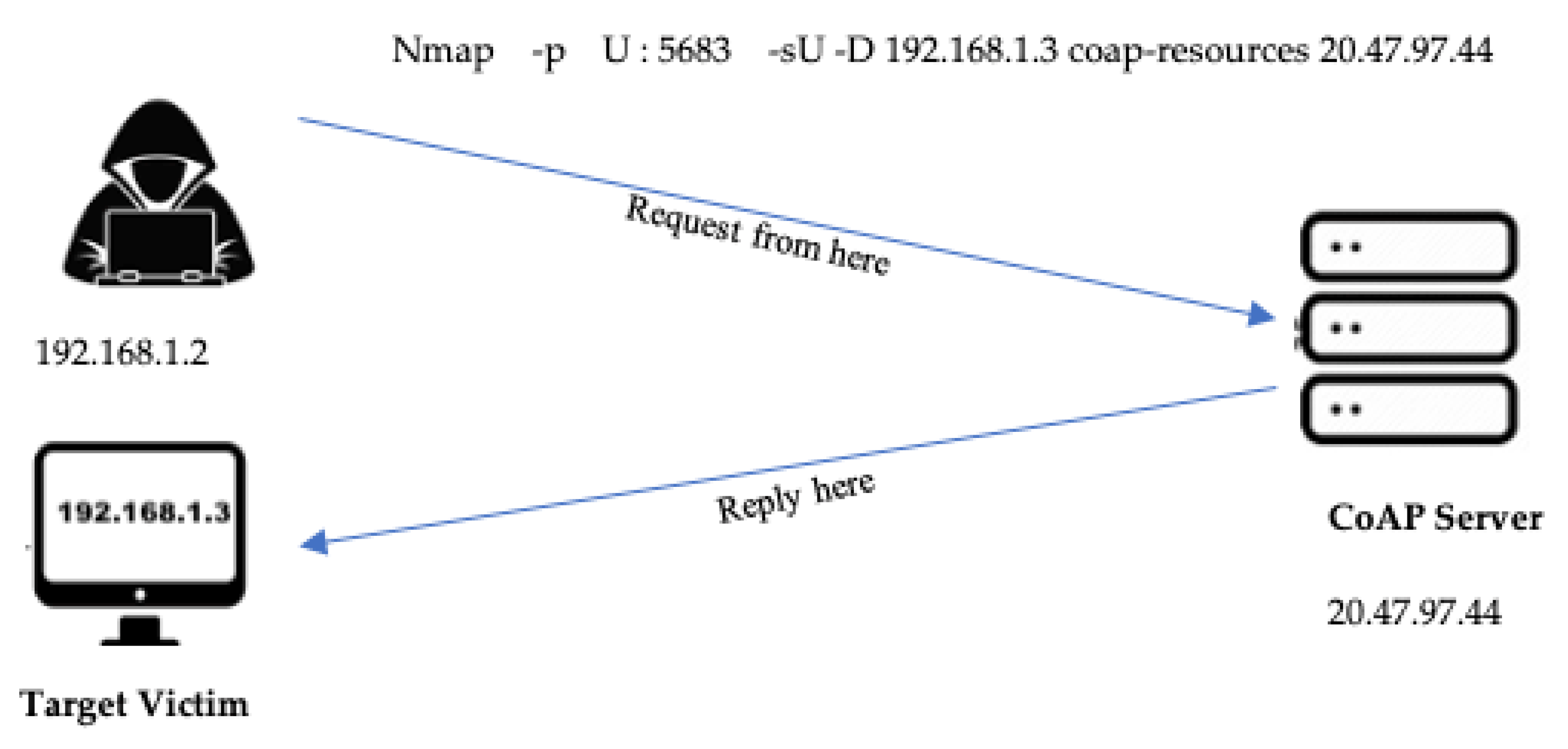

3.1. Dataset Creation

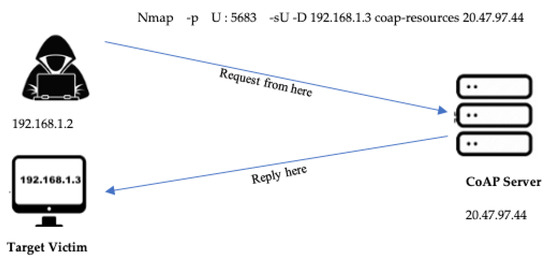

To create a balanced DoS CoAP amplification dataset, the Libcoap project [32] was used to differentiate between the benign and the attack packets. This project provides a C implementation for the CoAP client and the CoAP server, which run over the Contiki operating system (the lightweight OS for IoT devices). The benign packet only requests the available resources from the CoAP server (mostly requested as/well-known/core), while the attack packet requests the same resources, but spoofs the IP address of the target victim, consequently, an amplification is acting. To spoof the IP address of the target victim, we use the well-known Nmap tool that performs the spoofing on a CoAP client [33]. This tool needs only the IP of the target victim and any response from the CoAP server that is directed towards the target victim. Figure 7 illustrates the spoofing technique that causes the CoAP amplification. There are available CoAP servers online that we can be used for experimentation. For example, Shodan.io [34] provides a list of CoAP servers available online, and many of them allow to perform the attack scenarios. This research uses the Californium CoAP server available online and gains authorization from the owners to simulate the attacks [35].

Figure 7.

Lab experiment for simulating the simple amplification attack.

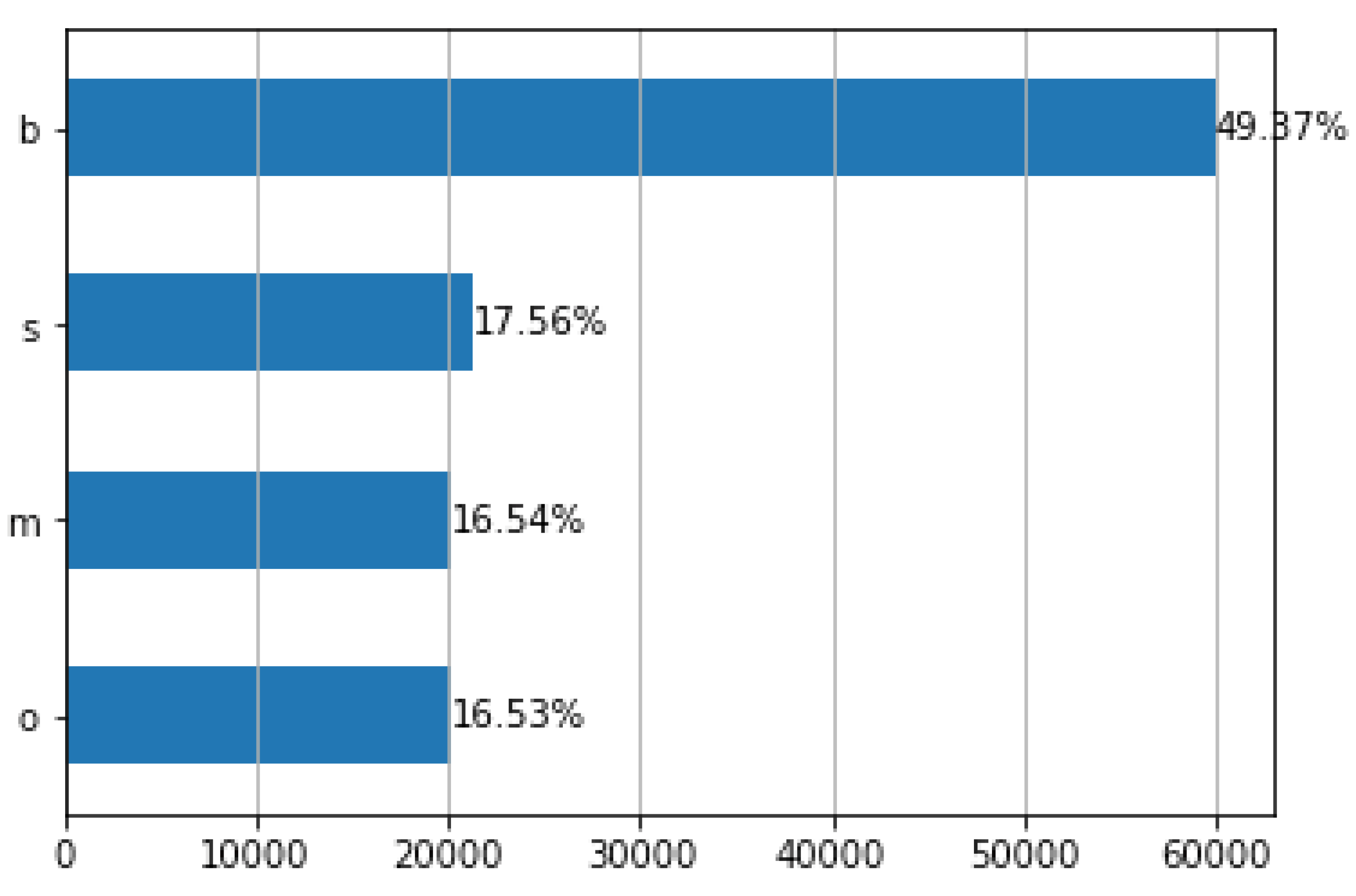

For the rest of the attacks, experiments are conducted to simulate the CoAP amplification using observe and the amplification using multicast. The experiment was conducted on a Linux machine with Ubuntu 22.04 as the OS. The RAM was 8 Gigabytes with a Core i7 CPU. While running the simulated attack, Wireshark captured each coming and outgoing packet. The collected packets are only CoAP-level packets as mentioned in Section 1.1. To create a balanced dataset, a total of 120,000 samples were collected, and out of which 60,000 are benign packets, and the rest are malware. Around 20,000 were used for the simple amplification attack, around 20,000 for the observe amplification attack, and roughly the same for the multicast amplification attack. Figure 8. illustrates the distribution of samples into benign and malware packets. The generated dataset is available at (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/salmeghlef/dos-amplification-attacks-against-coap (accessed on 5 May 2023)).

Figure 8.

Dataset distribution (b: benign, s: simple attack, o: observe attack, and m: multicast attack).

3.2. Data Preprocessing

For the CoAP packet, 86 features can be extracted from the pcap file [36] as described in Table 2, and most of which are optional features that may or may not be used in communication. In this work, we only consider the non-optional features to make sure we have the value for each feature.

Table 2.

CoAP Non-Optional Features [36].

Some of the collected features have numerical values, and others have non-numerical values, and for the machine learning classifiers, we need to convert these data to numerical values. So, we convert the non-numerical values to numerical values such as (0, 1) for Boolean features and the one-hot-encoding technique for some of the features that have different categories. For the labels, we have four labels, and we convert them to numerical values: 0 for benign, 1 for simple amplification, 2 for observe, and 3 for multicast. As a result, the entire dataset contains only numerical values. Some features have higher values, and to simplify these values for the computation of the algorithm, we normalize these values using the normalization Formula (4) to get the values between 0 and 1.

where zi is the rounded value, xi represents the actual value for a data point, and min(x) and max(x) are the minimum and maximum values in the same column.

3.3. Feature Selection

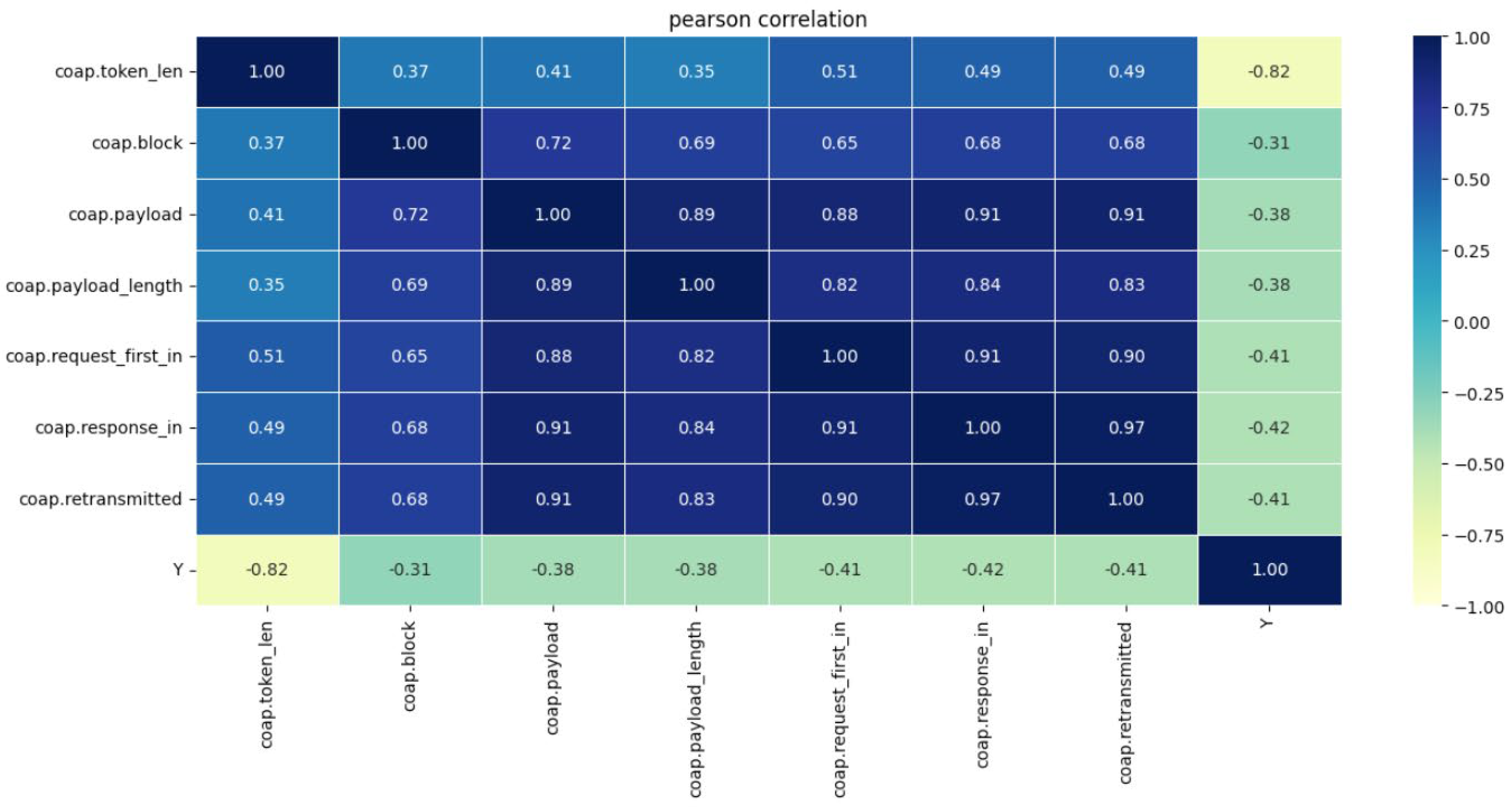

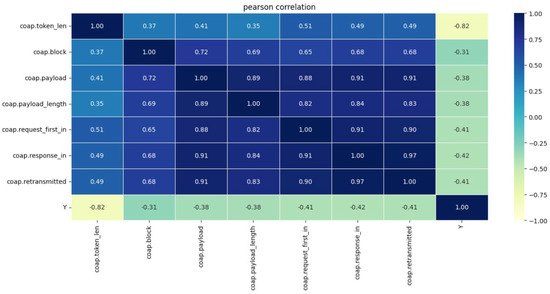

To train the classifiers for the multi-classification process, we need to get the most relevant features that lead to the correct label. This paper performs filtering using the Pearson Correlation method to find the most relevant features and grid of irrelevant features. It is assumed that any feature that has a ± 0.30 correlation with the label is relevant. To remove the redundancy in the features, we use Variance Inflation Factor (VIF).

VIF technique is to remove the collinearity features calculated from Formula (5). Using the Pearson Correlation in Formula (6), it is found that coap.block, coap.block.count, coap.block.error, coap.block.multiple_tails, coap.block.overlap, coap.block.overlap.conflicts, coap.block.reassembled.in, and coap.block.reassembled features are highly correlated with r = 1, so only one feature is retained coap.block, and the rest are dropped. Figure 9 shows the Pearson correlation between the features and in-between each feature and the label after removing the redundancy in the features.

Figure 9.

Pearson correlation for the features and the labels.

Here VIFj refers to the Variance Inflation Factor for the jth predictor, and R2 is calculated by regressing the jth.

where is the Pearson correlation between two features , n represents the total number of samples, are the individual sample points indexed with i, is the sample mean, and the same for .

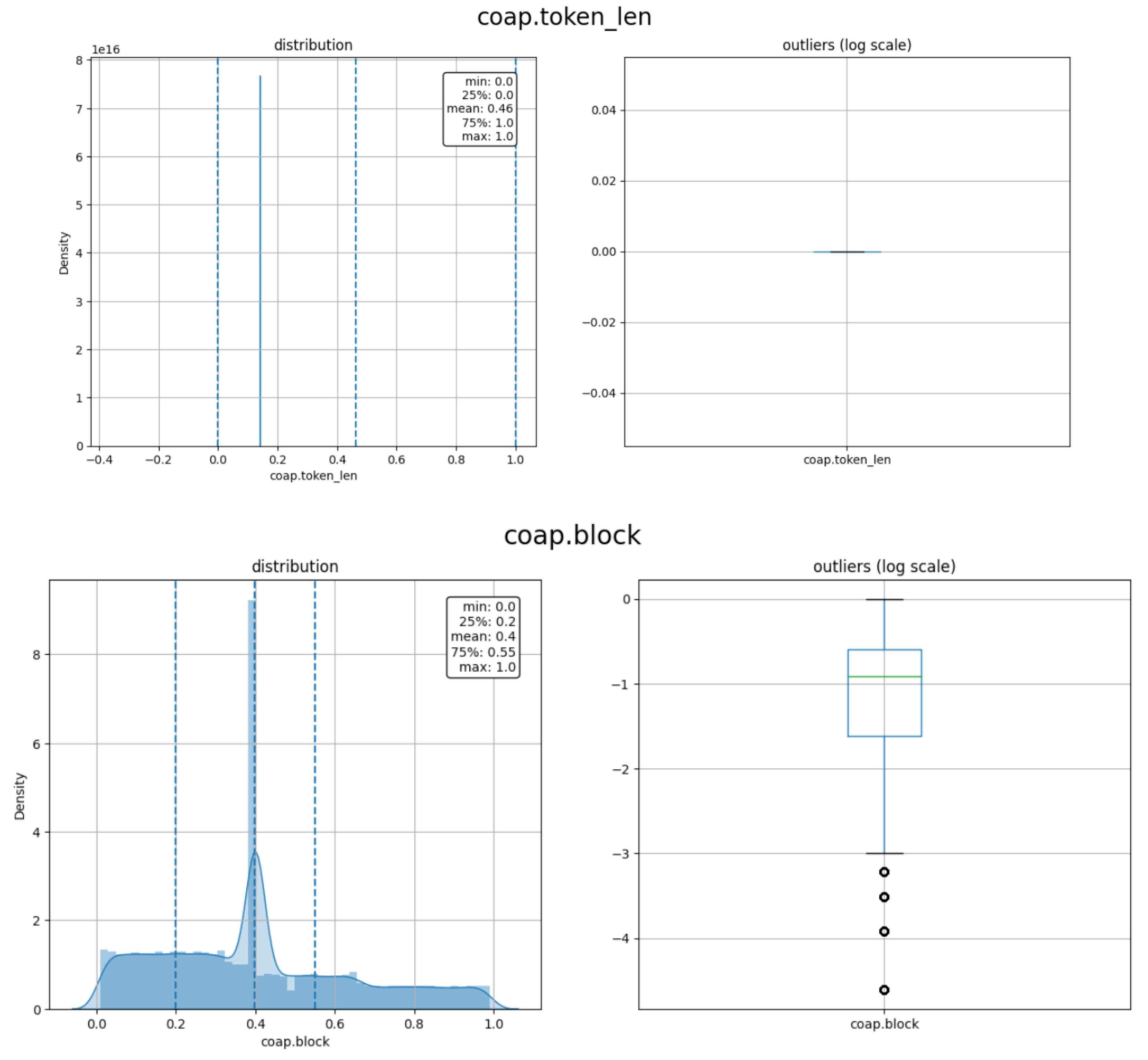

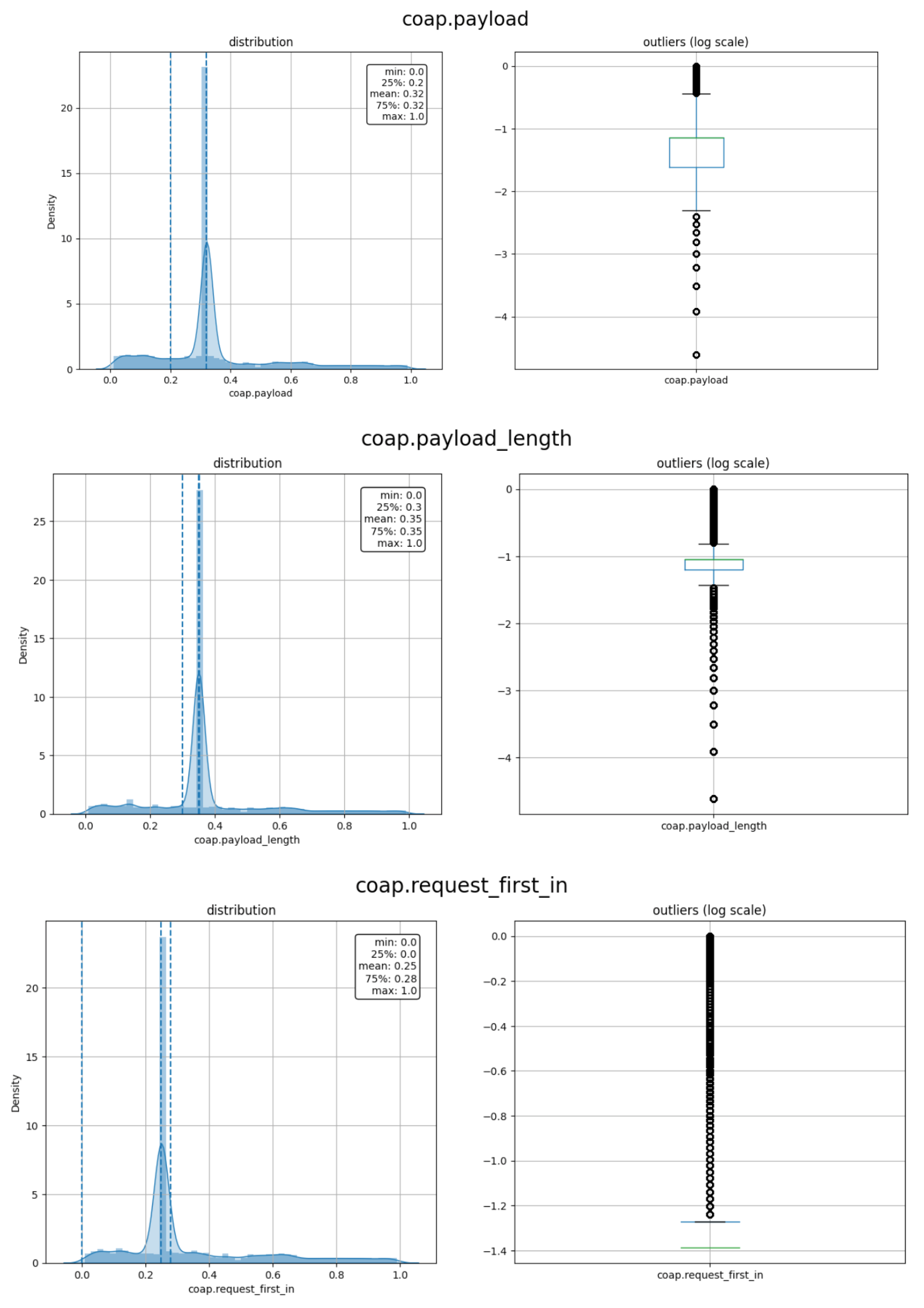

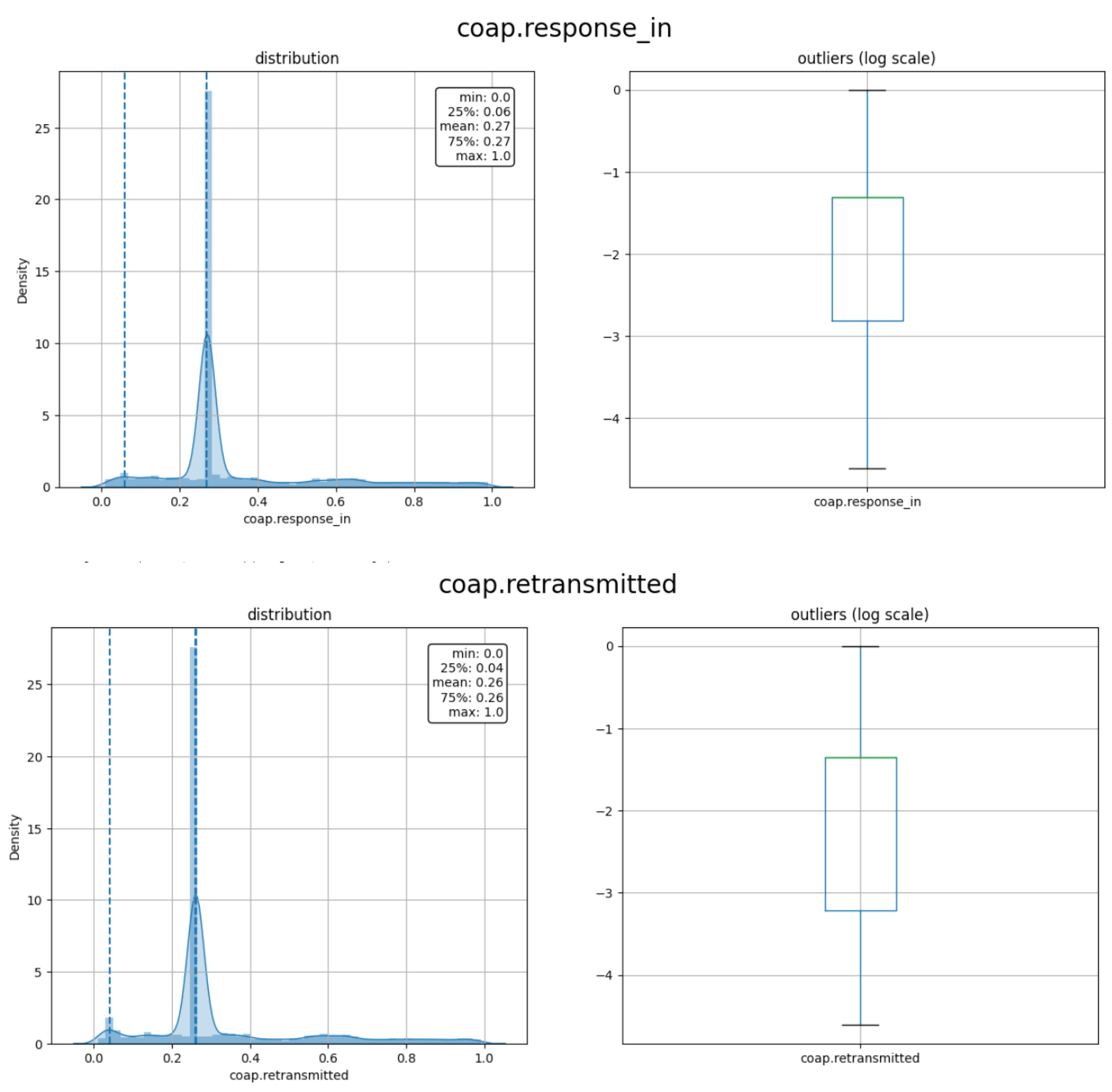

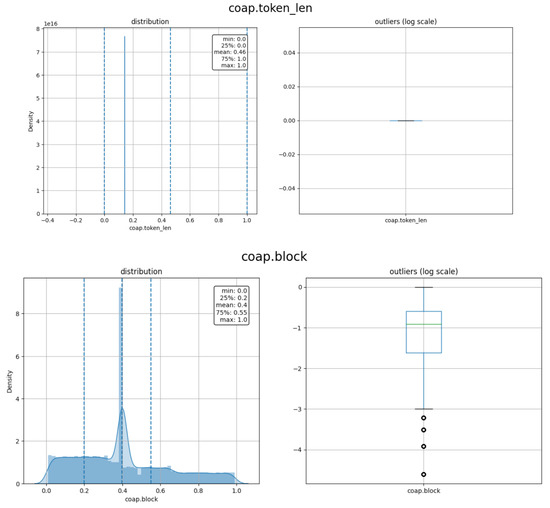

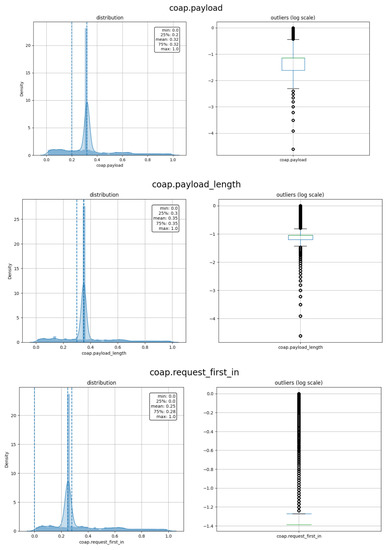

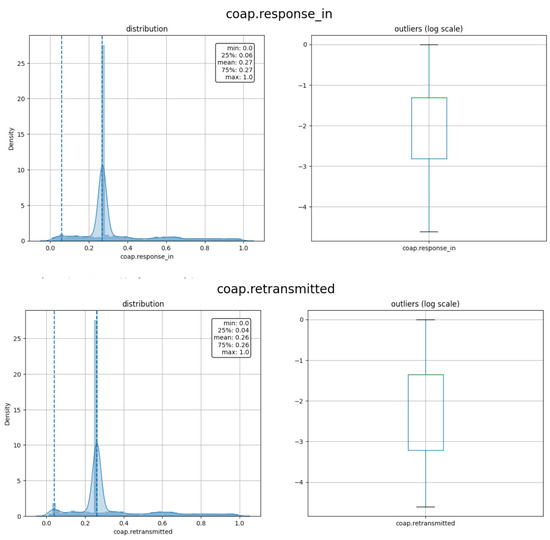

As shown in Figure 9, only seven features are considered highly correlated to the label namely: coap.token_len, coap.block, coap.payload, coap.payload_length, coap.request_first_in, coap.response_in, and coap.retransmitted after removing the irrelevant features and grid of the redundant features. The feature coap.token_len is highly correlated to the label with a negative correlation of r = −0.82. The feature coap.block is the less relevant feature with r = 0.31 with the label. As mentioned above, the threshold for the relevant feature is ±0.30 or above. The density of the selected features is depicted in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Density and outliers for the selected features.

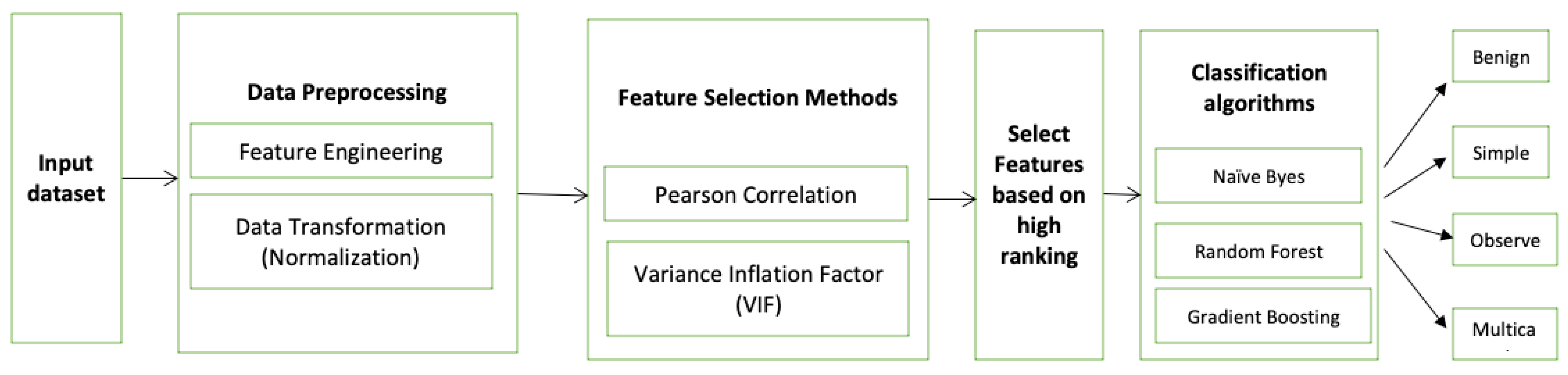

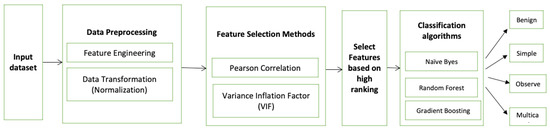

3.4. Model Training

For purposes of this study, three machine learning classifiers are selected (Naïve Byes, Random Forest, and Gradient Boosting algorithms) and compared in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score after defining each measurement with their formulae. The model is depicted in Figure 11. Based on the literature, Naïve Byes and Random Forest perform well for classifying benign and malware packets [37]. However, this study concludes that the advanced algorithm (Gradient Boosting Classifier) outperforms the Naïve Byes and the Random Forest algorithm. In the first phase, the data is split into 70% for training and 30% for testing. Then, the accuracy for each algorithm is calculated. The accuracy of the training is tested against the accuracy of the testing data to check for overfitting and underfitting. If there is no significant deviation between them, it means the model will perform well on the training data as well as generalize in the production. In the second phase, the research is validated using a cross-validation technique to check for biases in the data. We consider the fold = 5 to train the model for the four portions of the data and test on the hidden portion. After 5 iterations, the average accuracy is calculated. In the third phase, the confusion matrix of each algorithm is shown. Then, the confusion matrices for the algorithms are calculated and compared. The next section illustrates the findings in detail.

Figure 11.

The proposed model.

4. Results and Discussions

After performing the model training and testing, the following measurements are applied to compare the three-machine learning techniques using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score.

Accuracy: In the attack detection, it can be said that accuracy is the most correctly classified sample among all the classified samples.

where TP refers to the True Positive, TN refers to the True Negative, False Positive for FP, and False Negative for FN.

Precision: The proportion of the correctly classified positive samples to the overall positive samples. It can be defined mathematically as:

Recall: Is to measure all the positive elements in the dataset. It can be calculated as:

F1-score: is the mean for precision and recall of the model.

Following are the results for each model:

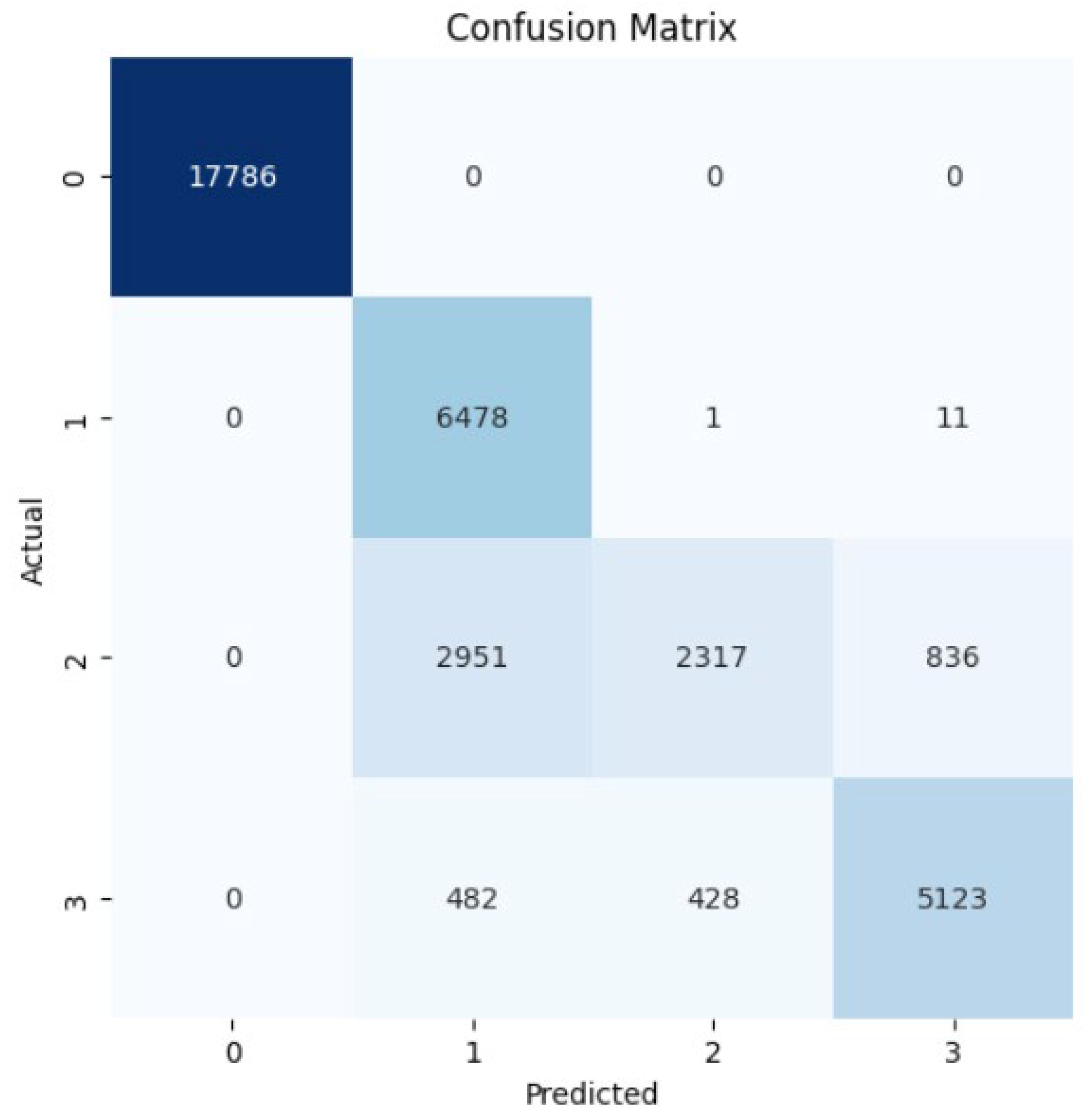

4.1. Naïve Byes

Naïve Byes (NB) comes from the statistical methods based on Byes Theorem. It is a machine learning classifier that is fit for classification problems. It is fast, accurate, and performs well with large datasets. As the name implies, NB does not obtain the relations between the features, assuming that each feature has an independent impact on the decision. The learning process is based on calculating the prior probability of a class label, and then, the likelihood for each feature for each class is calculated. The result is fed to the Byes formula to find the posterior probability. Naïve Byes shows a decent overall accuracy of 87% on this study’s data. Since this study is based on a multi-classification process, the macro average and weighted average have also been calculated. The macro average represents the mean for all the metrics of the classes while giving the same weight for all the classes, whereas the weighted average is calculated using the average of the binary metrics weighted by the number of samples for each class. As shown in Table 3, the macro average is 0.83 for precision, 0.81 for recall, and 0.79 for the F1 score. The weighted average gives better results with 0.89 for precision, 0.87 for recall, and 0.86 for F1-score.

Table 3.

Metric for Naïve Byes Algorithm.

From the confusion matrix in Figure 12, it can be inferred that the observe technique is wrongly misclassified as simple or multicast amplification. Since Naïve Byes does not consider the relations between the features, it shows worse overlapping in the multiclassification process. As mentioned in Section 3.1, the benign, simple, observe, and multicast packets are converted to 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

Figure 12.

Confusion Matrix for Naïve Byes Algorithm.

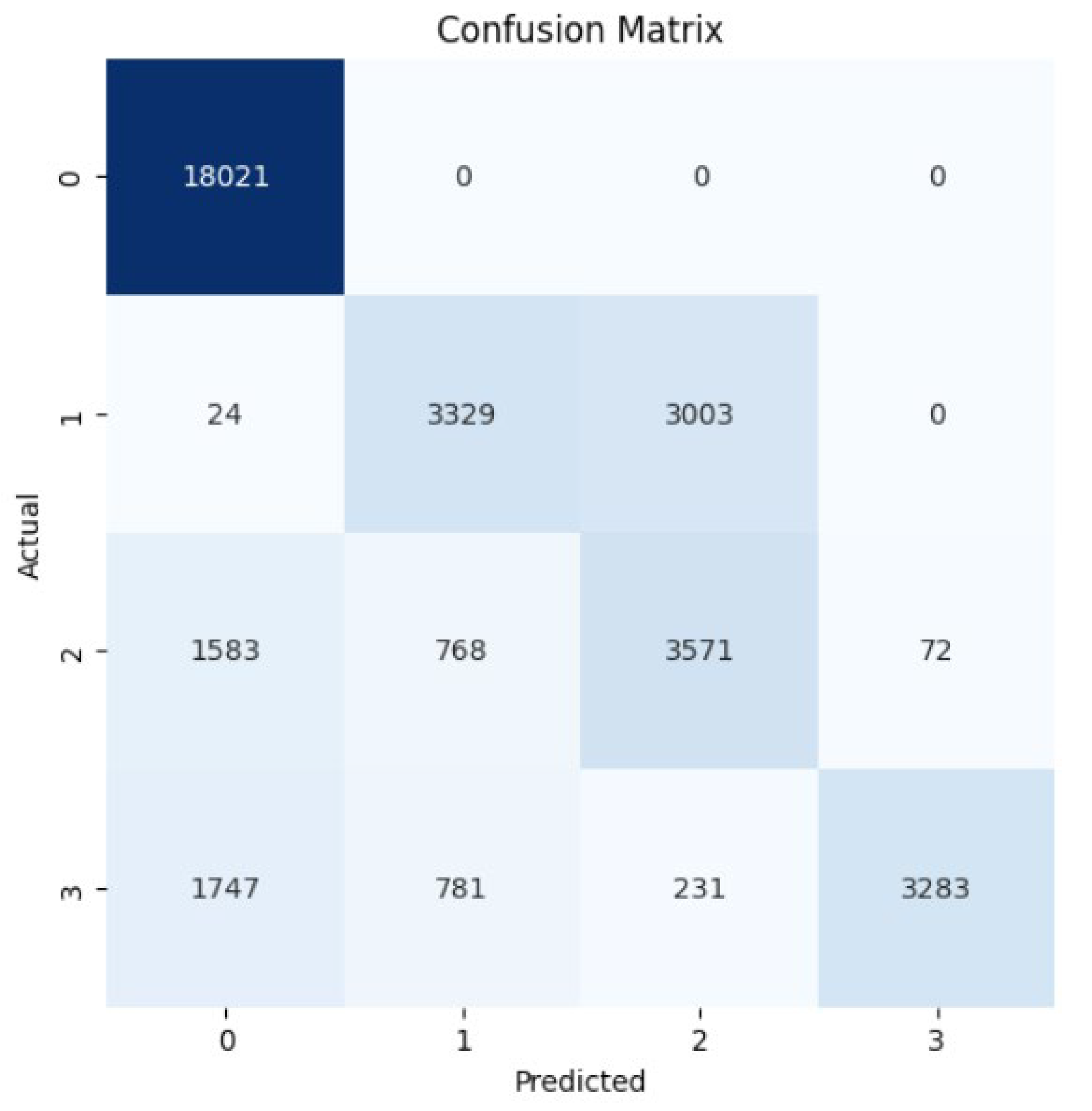

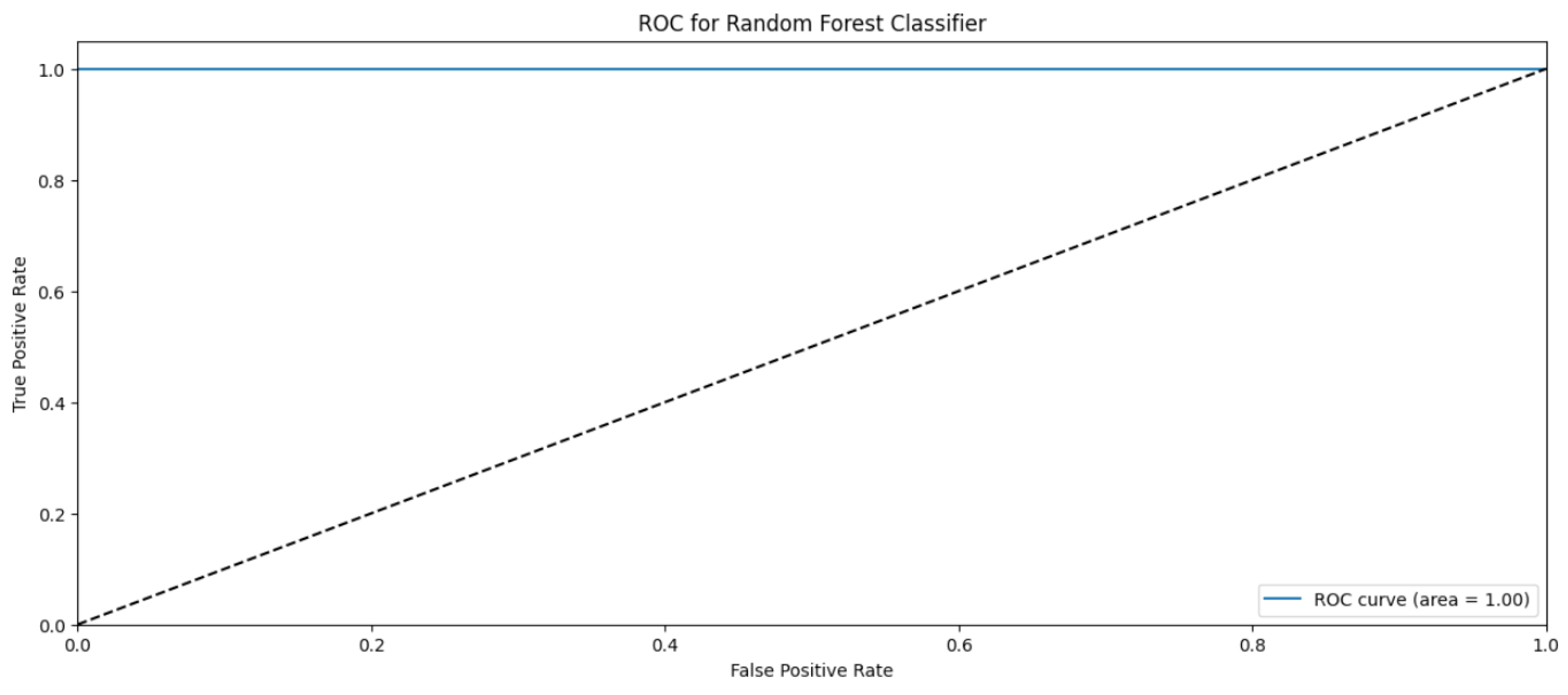

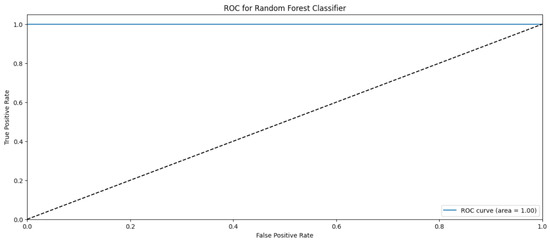

4.2. Random Forest

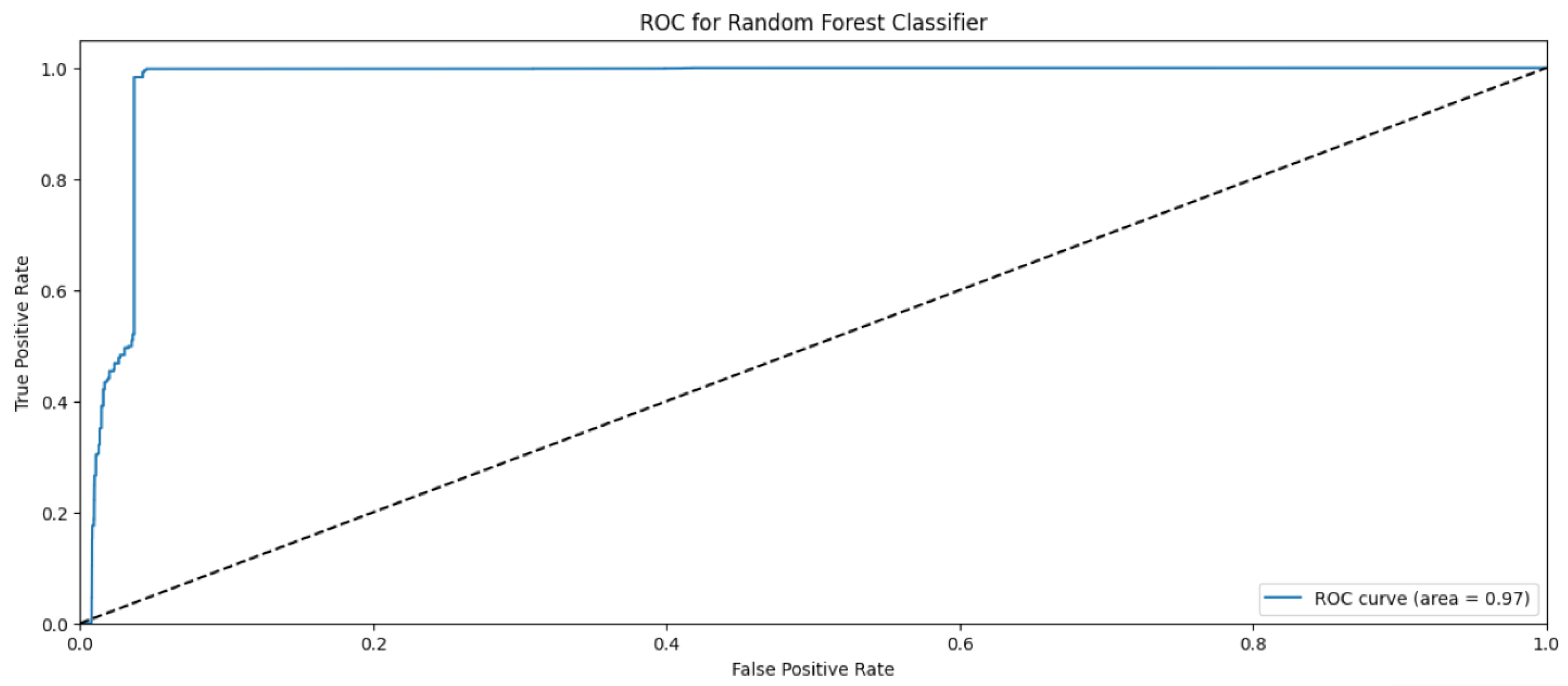

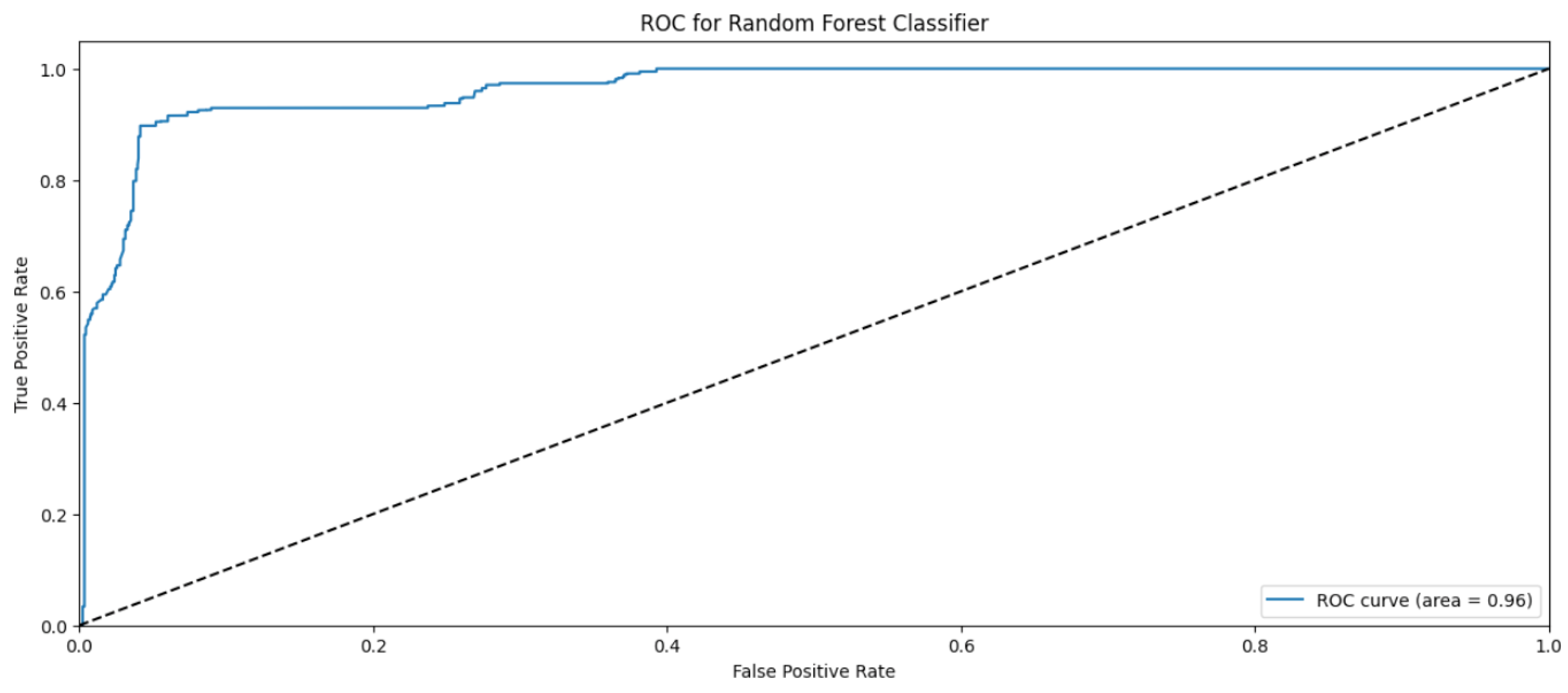

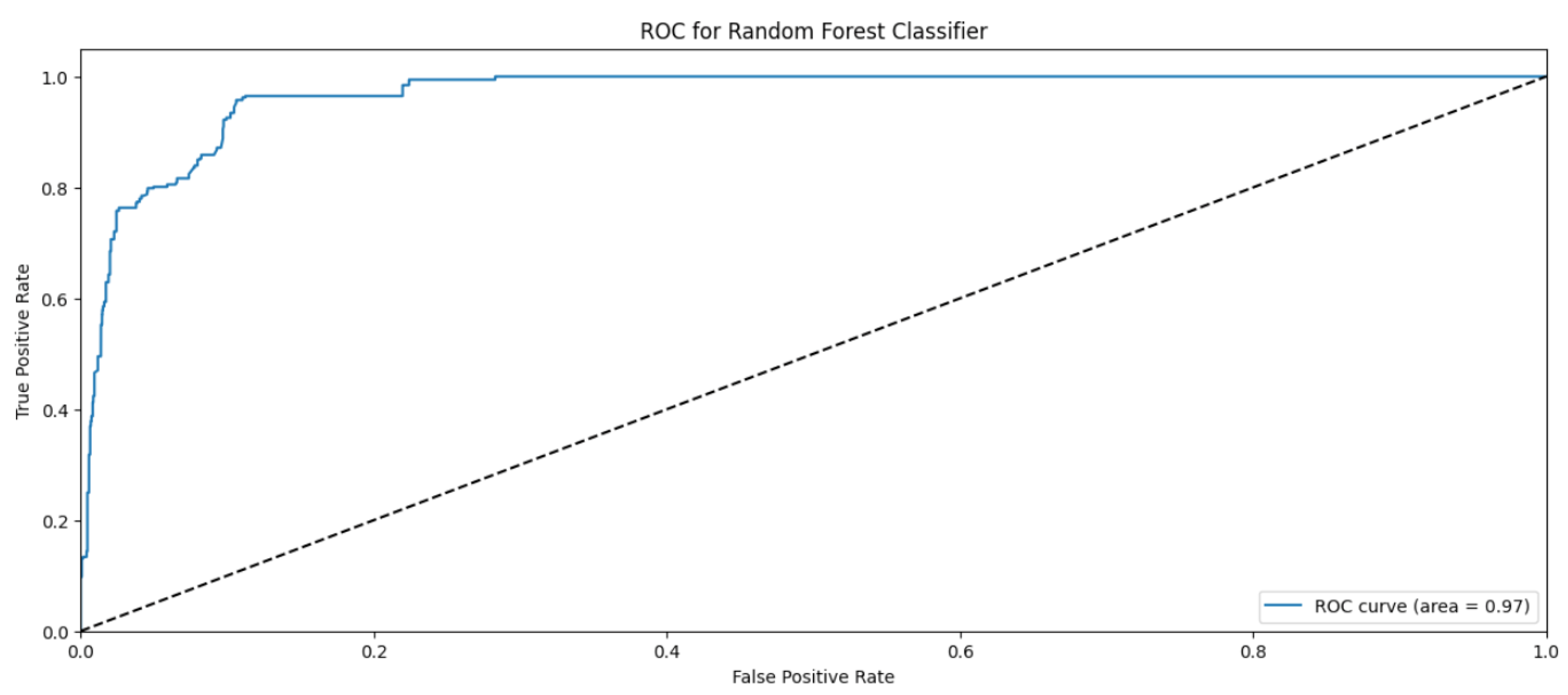

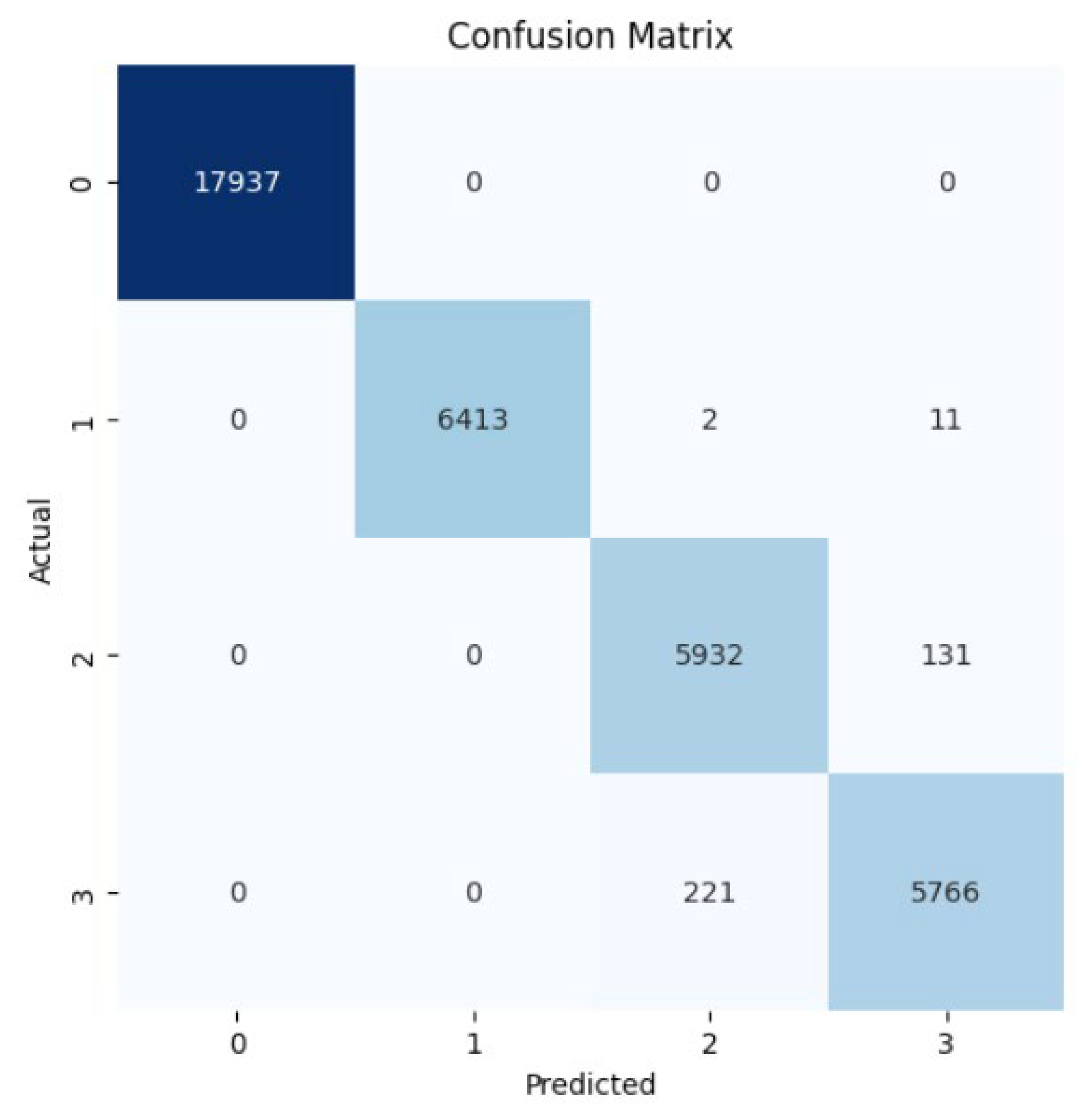

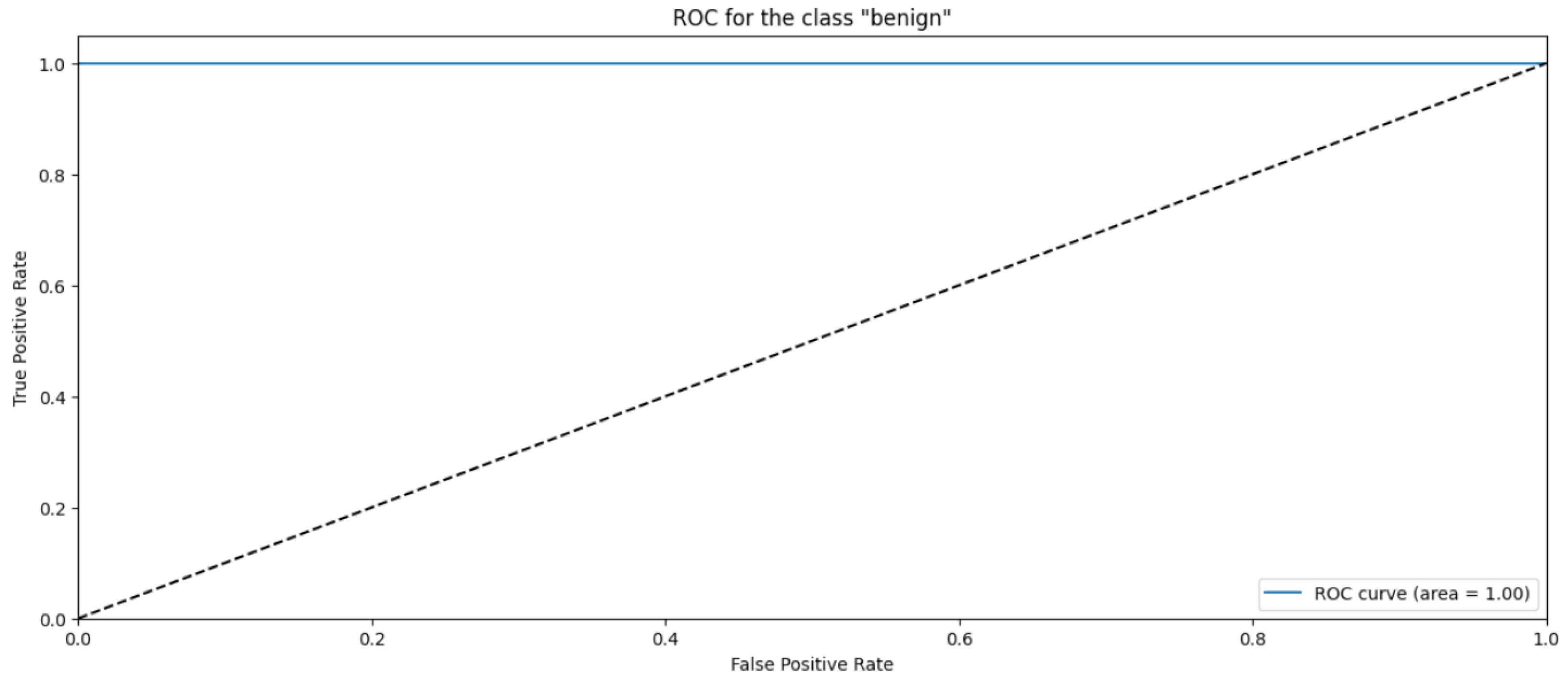

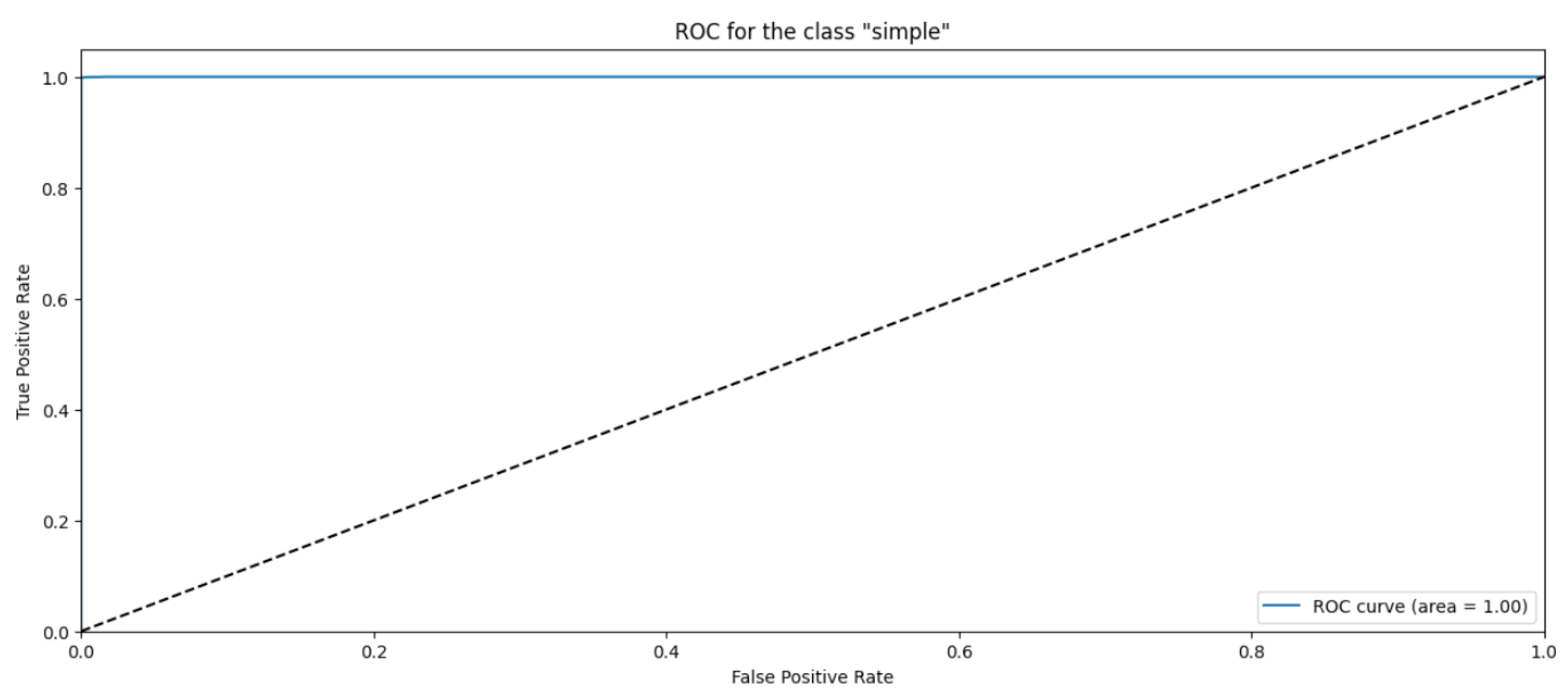

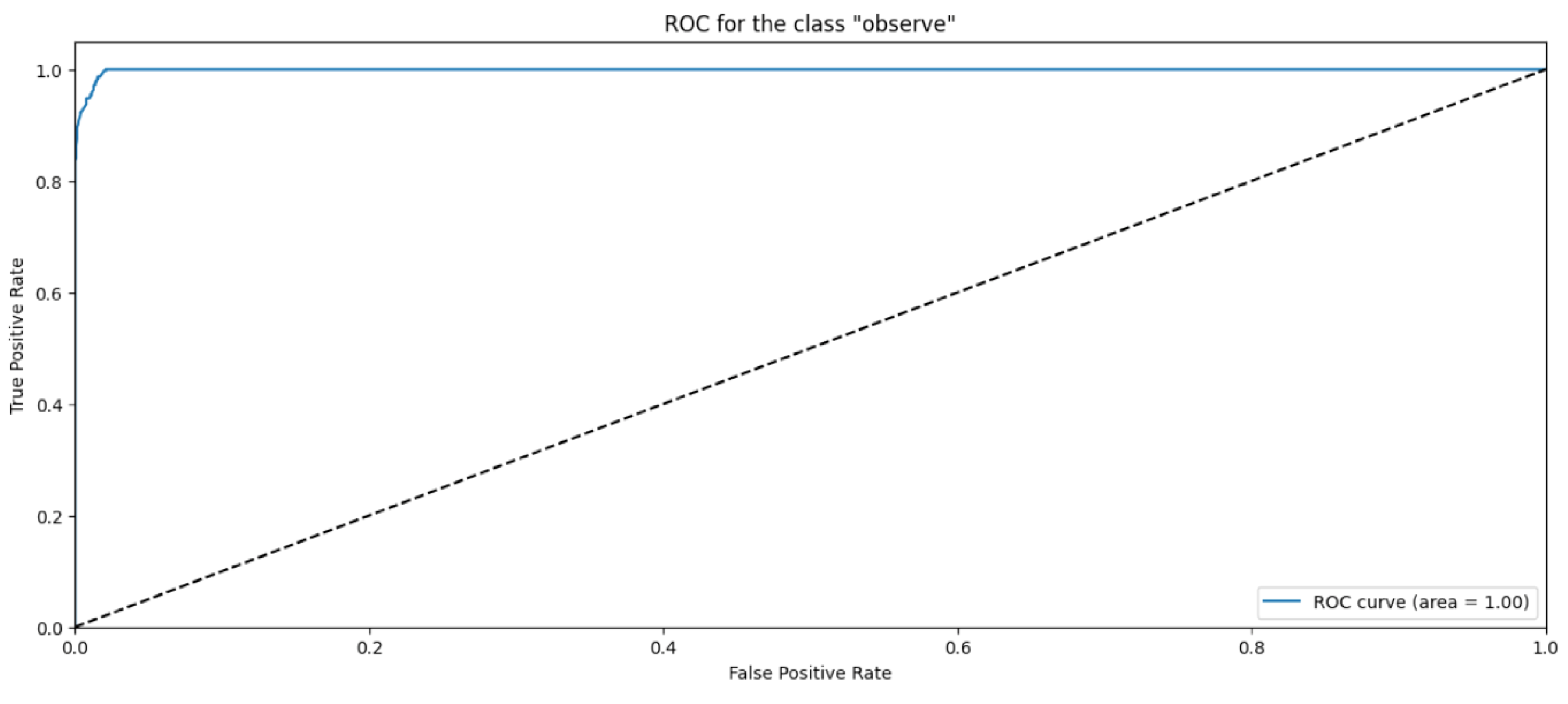

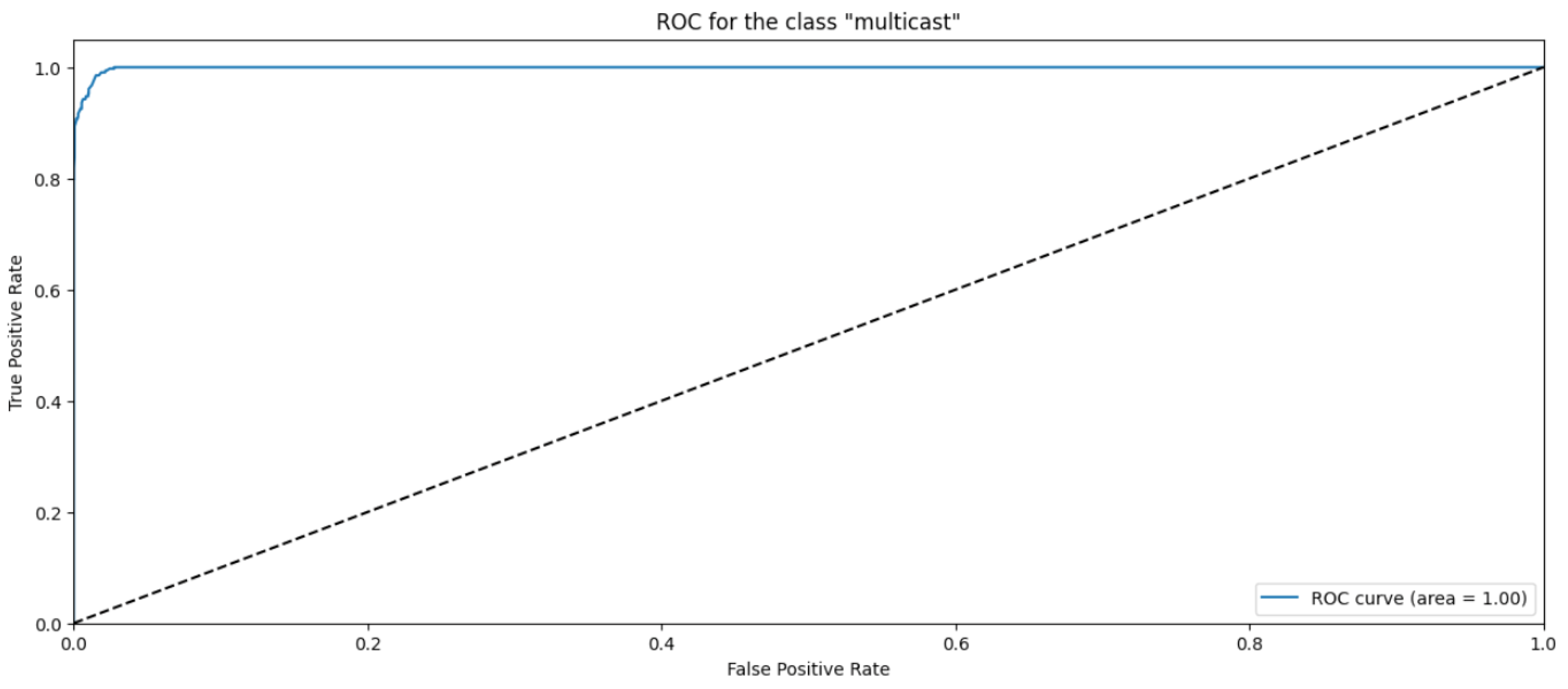

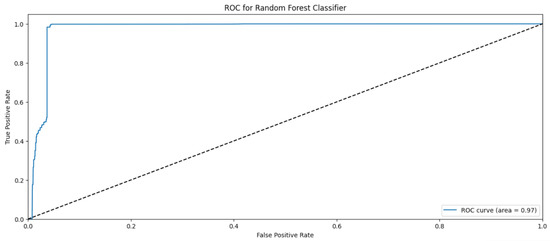

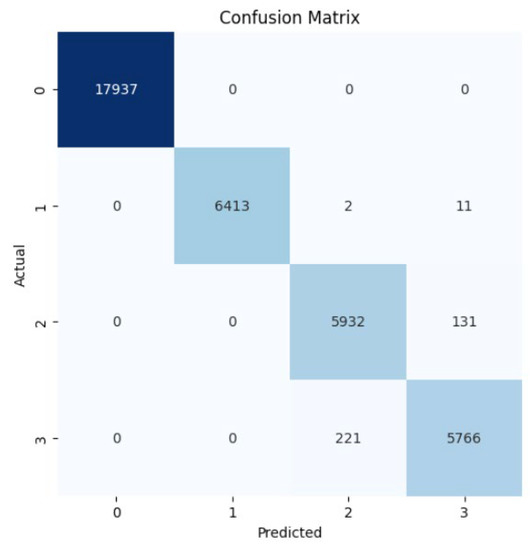

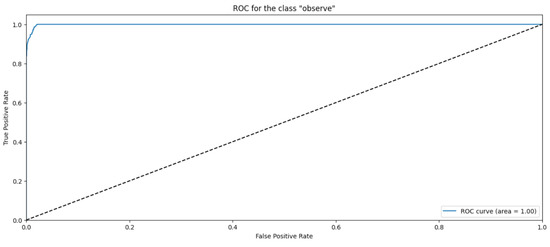

Random Forest Classifier (FR) belongs to the decision tree algorithms family that rely on ensemble methods to avoid overfitting and underfitting that is common in traditional decision tree algorithms. The bagging methods are used to train RF by splitting the training data into sets, applying the decision tree for these sets, and then accumulating the results. Randomness and repetition of samples in RF is common, meaning a single instance may be used more than once due to recurrent sampling. In this research, the Random Forest algorithm performs worse than the Naïve Byes. The overall accuracy is 83%. The weighted precision, recall, and F1-score is 0.85, 0.83, and 0.81, respectively. Table 4 shows the metrics for Random Forest Algorithm. The confusion matrix (Figure 13) shows a significant misclassification for the simple amplification class as the model labeled around half of the simple amplification samples as benign. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve has been used to figure out the Random Forest performance at all classification thresholds. The ROC curve plots the true positive rate versus the false positive rate. As depicted in Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17, it appears that the rate of false positive is much worse in the “simple” and “multicast” classes than in the “benign” and “observe” classes.

Table 4.

Metrics for the Random Forest Algorithm.

Figure 13.

Confusion matrix for the Random Forest algorithm.

Figure 14.

ROC curve for the “benign” class using RF algorithm.

Figure 15.

ROC curve for the “simple” class using RF algorithm.

Figure 16.

ROC curve for the “observe” class using RF algorithm.

Figure 17.

ROC curve for the “multicast” class using RF algorithm.

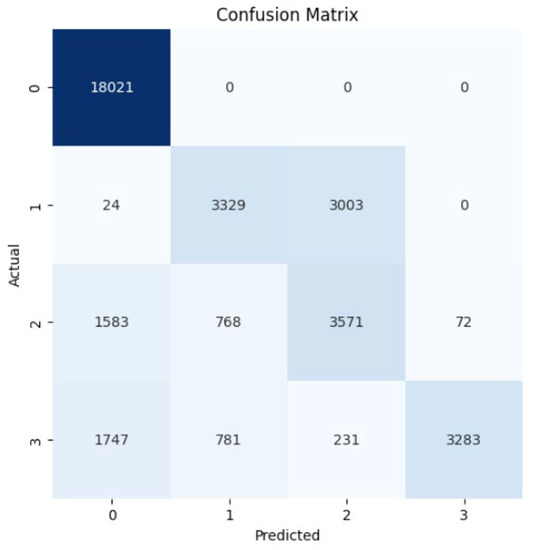

4.3. Gradient Boosting Classifier

The Gradient Boosting (GB) algorithm is a machine learning technique that is similar to the decision trees in terms of the prediction model that relies on an ensemble of weak prediction. Basically, it is like the Random Forest except that it fits the error in the tree concurrently. The GB algorithm performs well with an accuracy of 99%. The weighted average for precision, recall, and F1-score is 99% for all of them. Table 5 summarizes the performance of the Gradient Boosting Classifier. The confusion matrix (Figure 18) shows two samples of the simple amplification that are wrongly misclassified as observe and 126 samples wrongly misclassified as multicast. In terms of the ROC curve, the ROC shows a less false positive rate for almost all the classes except 235 samples are wrongly misclassified as observe class instead of multicast class as depicted in Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21 and Figure 22. Overall, this model performs well in classifying the amplification attacks against the CoAP protocol as depicted in Figure 23.

Table 5.

Metrics for the Gradient Boosting Classifier.

Figure 18.

Confusion matrix for the Gradient Boosting Classifier.

Figure 19.

ROC curve for the “benign” class using GB algorithm.

Figure 20.

ROC curve for the “simple” class using GB algorithm.

Figure 21.

ROC curve for the “observe” class using GB algorithm.

Figure 22.

ROC curve for the “multicast” class using GB algorithm.

Figure 23.

Comparison of the accuracy performance between the classifiers.

5. Discussion

Compared to the related methods in the literature, this work focuses only on the CoAP-level features, while recent methods rely on the lower layers to vet the CoAP messages. For example, Median et al. [20] proposed an anomaly-based method to vet the CoAP messages while collecting features from different layers of the IoT network architecture such as transport layer (UDP packet features). The motivation behind this research was to secure the CoAP in its vicinity based on the assumption that it is better to build the detection system near to the source [6]. Moreover, this research discusses the DoS amplification attacks that are launched from and against CoAP victim clients, which is contrary to the proposed methods for securing CoAP server from DoS and DDoS attacks. For instance, Yizhen et al. [25] built a detection system that operates over the edge servers that are closest to the IoT network. The datasets used in the related works [9,10,11] and [12] do not contain the DoS amplification attacks derived from CoAP client attacking another victim CoAP client. In addition, new methods for securing CoAP in its perimeter are promising and facilitates accommodating the detection system near the source as in [38]. Moreover, new technologies such as Blockchain can help to detect the IoT threats [39].

6. Conclusions

This research defines the amplification attacks that target the CoAP protocol. The main contribution of this work is to extend the state-of-the-art techniques for securing the CoAP against DDoS attacks that are based on a binary classification and focus only on the attacks launched from the CoAP client side to the CoAP server side. Moreover, this research also carries out a multi-classification process for the DoS CoAP amplification attacks. We consider the attacks that happened between a CoAP client against another victim client(s). After categorizing and implementing each of the DoS CoAP amplification attacks, a dataset is created by simulating the attacks to overcome the lack of datasets that contain the DoS CoAP amplification attacks. Then, three machine learning models were tested for detecting and classifying each attack. The proposed model shows an impressive result in detecting and classifying the malware with an accuracy of 99% using the Gradient Boosting Classifier. In the future, implement the man-in-the-middle attack (MITM) spoofing technique is introduced to focus only on the CoAP level packets, while MITM uses the lower layers to initiate the DoS amplification against the CoAP in the application layer level. Moreover, implementing the model in a real environment is recommended to test its efficiency. Extending the dataset and combining it with other DoS attacks that target the CoAP will result in a comprehensive dataset for the research community for practicing and experimenting with different models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.A. and A.A.-M.A.-G.; methodology, M.S.R. and M.R.; software, S.M.A.; validation, S.M.A., A.A.-M.A.-G., and M.S.R.; formal analysis, S.M.A.; investigation, A.A.-M.A.-G., M.S.R., and M.R.; resources, S.M.A.; data curation, S.M.A., A.A.-M.A.-G., and M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.A.; writing—review and editing, S.M.A. and M.R.; visualization; S.M.A.; funding acquisition, S.M.A.; supervision, A.A.-M.A.-G.; project administration, S.M.A. and M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Technical and Vocational Training Corporation (TVTC) for their support in performing this research. Furthermore, we thank the supervisors for all the support and direction provided by them to produce this research. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the Faculty of Computing and Information Technology (FCIT), King Abdulaziz University (KAU), Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| CoAP | Constrained Application Protocol |

| UDP | User Datagram Protocol |

| TCP | Transmission Control Protocol |

| DTLS | Datagram Transport Layer Security |

| NoSec | No Security mode |

| RPL | Routing Protocol |

| 6LoWPAN | IPv6 over Low-power Wireless Personal Area Networks |

| LLN | Low-Power and Lossy Networks |

| LSPWSN | Lightweight and Secure Protocol for Wireless Sensor Networks |

| MQTT | Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| DoS | Denial-of-Service |

| DDoS | Distributed Denial-of-Service |

| SDN | Software Defined Networking |

| Nmap | Network Mapping |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

References

- Vishwakarma, R.; Jain, A.K. A survey of DDoS attacking techniques and defense mechanisms in the IoT network. Telecommun. Syst. 2020, 73, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, N.F. IoT-MQTT Based Denial of Service Attack Modelling and Detection. 2020. Available online: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/2303 (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Hussain, F.; Abbas, S.G.; Husnain, M.; Fayyaz, U.U.; Shahzad, F.; Shah, G.A. IoT DoS and DDoS attack detection using ResNet. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 23rd International Multitopic Conference (IN-MIC), Bahawalpur, Pakistan, 5–7 November 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ragab, M. Hybrid firefly particle swarm optimization algorithm for feature selection problems. Expert Syst. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Alhaidari, F.A.; Alqahtani, E.J. Securing communication between fog computing and IoT using constrained application protocol (coap): A survey. J. Commun. 2020, 15, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, K.; Miranda, J.C.; Gavrilovska, A. Towards IoT-DDoS prevention using edge computing. In Proceedings of the {USENIX} Workshop on Hot Topics in Edge Computing (HotEdge 18), Boston, MA, USA, 9 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shelby, Z.; Hartke, K.; Bormann, C. RFC 7252: The Constrained Application Protocol (CoAP); ACM, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amplification Attacks Using the Constrained Application Protocol (CoAP). (n.d.). IETF Datatracker. Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/draft-irtf-t2trg-amplification-attacks/ (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Capossele, A.; Cervo, V.; De Cicco, G.; Petrioli, C. Security as a CoAP resource: An op-timized DTLS implementation for the IoT. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE international conference on communications (ICC), London, UK, 8–12 June 2015; pp. 549–554. [Google Scholar]

- Maleh, Y.; Ezzati, A.; Belaissaoui, M. An enhanced DTLS protocol for Internet of Things applications. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Wireless Networks and Mobile Communications (WINCOM), Fez, Morocco, 26–29 October 2016; pp. 168–173. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.M.; Gandhi, U.D. Enhanced DTLS with CoAP-based authentication scheme for the internet of things in healthcare application. J. Supercomput. 2020, 76, 3963–3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjya, A.; Zhong, X.; Wang, J.; Li, X. CoAP—Application layer connection-less lightweight protocol for the Internet of Things (IoT) and CoAP-IPSEC Security with DTLS Supporting CoAP. In Digital Twin Technologies and Smart Cities; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 151–175. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, J.; Chatterjee, P.; Banik, S. CoAP-DoS: An IoT Network Intrusion Data Set. In Proceedings of the 2022 6th International Conference on Cryptography Security and Privacy (CSP), Tianjin, China, 14–16 January 2022; pp. 91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Granjal, J.; Silva, J.M.; Lourenço, N. Intrusion detection and prevention in CoAP wireless sensor networks using anomaly detection. Sensors 2018, 18, 2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, M.; Kaliyar, P.; Lal, C. Censor: Cloud-enabled secure IoT architecture over SDN paradigm. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2019, 31, e4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özçelik, M.; Chalabianloo, N.; Gür, G. Software-defined edge defense against IoT-based DDoS. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (CIT), Helsinki, Finland, 21–23 August 2017; pp. 308–313. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, D.; Zhang, L.; Yang, K. A DDoS attack detection and mitigation with software-defined internet of things framework. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 24694–24705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeano-Brajones, J.; Carmona-Murillo, J.; Valenzuela-Valdés, J.F.; Luna-Valero, F. Detection and mitigation of dos and DDoS attacks in IoT-based stateful Sdn: An experimental approach. Sensors 2020, 20, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhai, B.; Liu, J. IoT-based DDoS attack detection and mitigation using the edge of sdn. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Cyberspace Safety and Security, Guangzhou, China, 1–3 December 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Meidan, Y.; Bohadana, M.; Mathov, Y.; Mirsky, Y.; Shabtai, A.; Breitenbacher, D.; Elovici, Y. N-baIoT—Network-based detection of IoT botnet attacks using deep autoencoders. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2018, 17, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvitić, I.; Peraković, D.; Periša, M.; Botica, M. Novel approach for detection of IoT generated DDoS traffic. Wirel. Netw. 2021, 27, 1573–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, R.; Jain, A.K. A honeypot with machine learning-based detection framework for defending IoT based botnet DDoS attacks. In Proceedings of the 2019 3rd International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics (ICOEI), Tirunelveli, India, 23–25 April 2019; pp. 1019–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Soe, Y.N.; Santosa, P.I.; Hartanto, R. DDoS attack detection based on simple ann with smote for IoT environment. In Proceedings of the 2019 Fourth International Conference on Informatics and Computing (ICIC), Semarang, Indonesia, 16–17 October 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Dao, N.-N.; Phan, T.V.; Kim, J.; Bauschert, T.; Cho, S. Securing heterogeneous IoT with intelligent DDoS attack behavior learning. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.06041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Zhong, F.; Alrawais, A.; Gong, B.; Cheng, X. Flowguard: An intelligent edge defense mechanism against IoT DDoS attacks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 9552–9562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Wan, P.; Qiang, W.; Yang, L.T.; Zou, D.; Jin, H.; Xu, S.; Huang, Z. Tnguard: Securing IoT oriented tenant networks based on sdn. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 1411–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djouani, R.; Djouani, K.; Boutekkouk, F.; Sahbi, R. A security proposal for IoT integrated with sdn and cloud. In Proceedings of the 2018 6th International Conference on Wireless Networks and Mobile Communications (WINCOM), Marrakesh, Morocco, 16–19 October 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Muthanna, A.; A Ateya, A.; Khakimov, A.; Gudkova, I.; Abuarqoub, A.; Samouylov, K.; Koucheryavy, A. Secure and reliable IoT networks using fog computing with software-defined networking and blockchain. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2019, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroniotis, N.; Moustafa, N.; Sitnikova, E.; Turnbull, B. Towards the development of realistic botnet dataset in the internet of things for network forensic analytics: Bot-iot dataset. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 100, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhan, M.; Layeghy, S.; Moustafa, N.; Portmann, M. Netflow datasets for machine learn-ing-based network intrusion detection systems. In Big Data Technologies and Applications: 10th EAI International Conference, BDTA 2020, and 13th EAI International Conference on Wireless Internet, WiCON 2020, Virtual Event, December 11, 2020, Proceedings 10; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazanfar, S.; Hussain, F.; Rehman, A.U.; Fayyaz, U.U.; Shahzad, F.; Shah, G.A. March. Iot-flock: An open-source framework for iot traffic generation. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Smart Technologies (ICETST), Karachi, Pakistan, 26–27 March 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- O. (n.d.). GitHub-Obgm/Libcoap: A CoAP (RFC 7252) Implementation in C. GitHub. Available online: https://github.com/obgm/libcoap (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Coap-Resources NSE Script—Nmap Scripting Engine Documentation. (n.d.). Available online: https://nmap.org/nsedoc/scripts/coap-resources.html (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Explore. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.shodan.io/explore (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- (n.d.-a). GitHub-Eclipse-Californium/Californium: CoAP/DTLS Java Implementation. GitHub. Available online: https://github.com/eclipse-californium/californium (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Wireshark Display Filter Reference: Constrained Application Protocol. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.wireshark.org/docs/dfref/c/coap.html (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Shafiq, M.; Tian, Z.; Sun, Y.; Du, X.; Guizani, M. Selection of effective machine learning algorithm and Bot-IoT attacks traffic identification for internet of things in smart city. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 107, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeghlef, S.M.; AL-Ghamdi, A.A.-M.; Ramzan, M.S.; Ragab, M. Application Layer-Based Denial-of-Service Attacks Detection against IoT-CoAP. Electronics 2023, 12, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katib, I.; Ragab, M. Blockchain-Assisted Hybrid Harris Hawks Optimization Based Deep DDoS Attack Detection in the IoT Environment. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).