Abstract

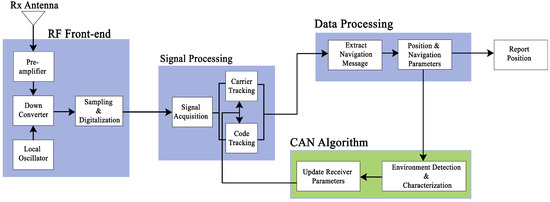

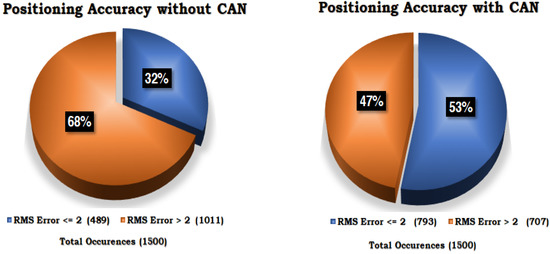

Accurate, ubiquitous and reliable navigation can make transportation systems (road, rail, air and marine) more efficient, safer and more sustainable by enabling path planning, route optimization and fuel economy optimization. However, accurate navigation in urban contexts has always been a challenging task due to significant chances of signal blockage and multipath and non-line-of-sight (NLOS) signal reception. This paper presents a detailed study on environmental context detection using GNSS signals and its utilization in mitigating multipath effects by devising a context-aware navigation (CAN) algorithm that detects and characterizes the working environment of a GNSS receiver and applies the desired mitigation strategy accordingly. The CAN algorithm utilizes GNSS measurement variables to categorize the environment into standard, degraded and highly degraded classes and then updates the receiver’s tracking-loop parameters based on the inferred environment. This allows the receiver to adaptively mitigate the effects of multipath/NLOS, which inherently depend upon the type of environment. To validate the functionality and potential of the proposed CAN algorithm, a detailed study on the performance of a multi-GNSS receiver in the quad-constellation mode, i.e., GPS, BeiDou, Galileo and GLONASS, is conducted in this research by traversing an instrumented vehicle around an urban city and acquiring respective GNSS signals in different environments. The performance of a CAN-enabled GNSS receiver is compared with a standard receiver using fundamental quality indicators of GNSS. The experimental results show that the proposed CAN algorithm is a good contributor for improving GNSS performance by anticipating the potential degradation and initiating an adaptive mitigation strategy. The CAN-enabled GNSS receiver achieved a lane-level accuracy of less than 2 m for 53% of the total experimental time-slot in a highly degraded environment, which was previously only 32% when not using the proposed CAN.

1. Introduction

The availability and accuracy of Positioning, Navigation and Timing (PNT) services can play a significant role in making transportation (road, rail, air and marine) more efficient, safer and sustainable by enabling route optimization and fuel economy planning [1,2,3,4]. Real-world applications, such as precision agriculture, real-time tracking, asset management, emergency response services, disaster management and autonomous driving, rely heavily on accurate positioning and time estimations [5,6,7,8,9] for proper functioning.

In addition, positioning and navigation technologies have recently played pivotal roles in the war against the COVID-19 pandemic by enabling the real-time tracking, tracing and locating of virus hot-spots by deploying geo-fencing [10,11,12] to monitor and control the spread of COVID-19. Among the various available solutions for precise positioning and navigation [13,14,15,16], the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) has established itself as a globally dominant and cost effective navigation technology [14,17].

Positioning and navigation in urban canyons has always been a challenging task [18,19,20] as GNSS receivers encounter areas with an insufficient availability of satellites due to multipath (MP) and/or non-line-of-sight (NLOS) signal reception. This remains a potential vulnerability of satellite-based navigation systems due to biased range measurements and inaccurate positioning estimates [21,22].

In [23], an initial study was performed on the characteristics of GNSS signals in highly obstructed environments by detecting and analyzing the possible deviations due to MP and NLOS reception. The quality of GNSS signals was analyzed and compared under different environments (i.e., LOS and NLOS) through field experiments. The results of these experiments showed that MP/NLOS could significantly affect the GNSS signal in terms of degraded tracking performance and frequent loss of lock.

At present, there are four independent global satellite constellations (GPS, GLONASS, Galileo and BeiDou) with more than 100 units in orbit that are transmitting signals at several frequency bands to increase the satellite density [24]. This helps to improve the positioning availability and accuracy in constrained and highly degraded multipath environments. This was also demonstrated in [25] where it was shown that, when combining four constellations (GPS, GLONASS, Galileo and BeiDou), more than 35 satellites could be accessed and tracked at a given location.

Similarly, researchers at Taoglas Inc. USA demonstrated a noticeable improvement in the positioning accuracy when using dual constellations (GPS and GLONASS) compared to single constellations [26]. The European GNSS Agency (ESA) and Networks Inc. performed several performance assessment tests in real-world environments and demonstrated that Galileo, when combined with GPS, provided more accurate positioning estimates compared to the GPS-only configuration [27].

In [28], researchers demonstrated that the performance of a tri-constellation navigation system in an obstructed environment (e.g., medium-height buildings) matched the performance of a GPS-only system in a clear open-sky environment when using only those satellites with elevation angles greater than 32 degrees. This implies that the impact of obstructions below 32 degrees can be mitigated by using an increased number of constellations.

Jing Guo et al. [5] demonstrated that, in degraded environments (e.g., farms surrounded with dense trees), the availability and accuracy of positioning decreased significantly for the GPS-only system; however, limited impacts were observed for the multi-constellation GNSS case due to a greater number of visible satellites. This was experimentally validated in [25], where the impacts of using multiple constellations compared to a single constellation system in three distinct environments (i.e., open sky, partially obstructed and highly obstructed environments) were investigated.

The results of our previous work on multi-constellation GNSS suggested that the positioning performance of a GNSS receiver may vary significantly with the type of operating environment. It has been established that the use of multiple constellations can enhance the availability and reliability of GNSS in constrained environments; however, this cannot guarantee improved positioning accuracy as debated in [5,25,26,27,28].

The positioning accuracy of satellites is usually determined by the availability, geometry and the quality of the received signals, and these factors are highly influenced by the dynamics and the structure of the urban canyon. At first, the obstructions in urban areas may result in blockages of the line-of-sight (LOS) of satellites, and this eventually distorts their geometric distribution [21]. However, this can be compensated for by using a multi-constellation GNSS configuration.

Secondly, the flat surface reflectors give rise to multipath (MP) or non-line-of-sight (NLOS) phenomena, which further degrade the quality of signals by introducing biases in the range measurements. There exists substantial research for improving the GNSS performance by minimizing the impact of MP and/or NLOS reception. This includes techniques to detect, model and mitigate the NLOS/multipath effects at various aspects, including the antenna, receiver and measurement [21,29,30].

Furthermore, there is another class of multipath/NLOS mitigation techniques that works at the discriminator level, such as the maximum likelihood techniques based on the multipath estimating delay locked loop (MEDLL) [31,32,33], the coupled amplitude DLL (CADLL) [30] and the multipath insensitive DLL (MIDLL) [34]. However, these mitigation approaches require an increased number of correlators, which results in increased system complexity and computational load.

Recently, the mitigation techniques at the receiver and measurement levels (i.e., detecting, de-weighting and rejecting the affected range measurements) has received significant attention because they do not require major hardware modifications [29]. These mitigation models/techniques, however, work effectively only in some contexts and not in all operating environments.

Similarly, the correlator-based techniques (i.e., MEDLL or its variants) cannot detect short-delay multipath environments and may introduce bias into the measurements due to their modifications inside the tracking channels of a correlator [30,35]. Typically, the detection and exclusion of faulty measurements (i.e., signals affected by MP/NLOS) help to improve the positioning accuracy; however, this leads to outages in dense urban environments due to the deficiency of redundant range measurements [25].

Practically, GNSS receivers operate in the wide range of environmental contexts, which significantly influences the signal reception conditions and severity of multipath/NLOS reception. Similarly, most of the multipath mitigation methods are not capable of effectively suppressing the NLOS/multipath effects in all contexts. Hence, in order to operate accurately and effectively in a wide range of environments, a GNSS receiver is required to adopt an optimal mitigation technique/method based on the detected context. Utilizing an inappropriate method may result in less effective reduction of multipath effects while consuming more power with a greater computational load.

There exist several methods for environmental context detection and characterization using the GNSS parameters, i.e., satellite availability, DOP, residuals and signal strength or its variants [36,37,38,39,40,41,42], to detect and identify the type of environmental context.

Most of the previous work focused on the development of context-detection models using single and dual constellations with little to no consideration to how these models can be utilized at the at receiver level to improve the availability and accuracy of navigation services [36,37,38,39,40,41,42].

In almost all of the previous work on context detection, signal strength or its variants were used as fundamental environment recognition parameters; however, this may not result in accurate context detection in the case of multi-constellation GNSS because: (1) the strength of the received signal is highly affected by NLOS and/or multipath; however, the severity of effects varies by frequency [43]; (2) the signal strength is majorly influenced by the elevation angle and can also be affected by the receiver efficiency or antenna design; and (3) a combination of multiple navigation systems in multi-constellation GNSS mode results in increased satellite density, and therefore monitoring the strength of each satellite can lead to a huge processing load.

This paper presents a detailed study on environmental context detection using multi-frequency and multi-constellation GNSS signals. A new context-aware navigation (CAN) method is proposed with context detection and characterization capabilities to mitigate the multipath effects in constrained environments by using adaptive GNSS receiver design in the multi-constellation mode.

The ultimate aim of work is to improve the navigation accuracy by detecting the operating environments and then adjusting the mitigation strategy accordingly. The CAN method utilizes a handful of GNSS parameters to categorize the environment into standard, degraded and highly degraded classes and then updates the receiver tracking loop based on the inferred environment to suppress the degradation effects.

The main difference between the proposed CAN and other methods is that it does not use the signal strength or its variants as key parameters for environment detection, instead it utilizes the globally and equally distributed property of GNSS, i.e., satellite availability and a new feature named the change factor (CF) for environment categorization. Additionally, the efficient design of proposed CAN, which includes selection of the optimal GNSS parameters along with context definitions for environment characterization makes it more practically realizable as compared to complex methods that would become practically impossible to implement in receivers.

Finally, to validate the performance of the proposed CAN algorithm, a detailed study on a multi-constellation GNSS receiver in the quad-constellation mode, i.e., GPS, BeiDou, Galileo and GLONASS, is conducted by driving an instrumented vehicle in and around the city center, and the results are then compared with a standard receiver. The rest of the manuscript is organized as follows: Section 2 discusses the methodology used for GNSS performance evaluation in a multi-constellation mode with field experiments, route dynamics, observation periods and signal-reception characteristics. Section 3 highlights the results of GNSS performance evaluation along with the statistical characteristics of the received signal quality. Section 4 presents the context-aware navigation (CAN) algorithm and its implementation on a real-time GNSS receiver. Finally, Section 5 gives our concluding remarks and recommendations for future extensions.

2. Performance Evaluation of a Standard Multi-Constellation GNSS Receiver

As we increasingly rely on GNSS-based positioning, understanding and mitigating GNSS vulnerabilities has become a critical risk management activity for manufacturers, systems and application providers as well as end-users as this can impact national security and may bring huge economic losses. The rigorous performance assessment under realistic conditions is key to understanding the different types of GNSS vulnerabilities and error contributors. In many studies, the performance of a GNSS receiver has been evaluated and characterized through field experimentation in static mode for long durations [44,45,46,47,48,49] or under controlled environmental conditions/settings [50].

Static tests provide good analysis of GNSS errors and can be used to establish cause and effect relationships; however, they are generally performed on pre-surveyed and known candidate sites. In addition, these tests provide little information regarding inaccuracies in positioning that occur due to movement or dynamics of the environment. On the other hand, on-road/field tests can be performed while navigating through different environmental contexts for more realistic GNSS performance assessment in a dynamic mode.

However, these tests are demanding in nature and require a considerable skill set and amount of subject knowledge to select accurate experimental sites, route trajectories and operational modes/scenarios [24,51,52,53,54].

In this section, dynamic performance assessment of a multi-constellation and multi-frequency standard-mode GNSS receiver is performed using fundamental quality indicators, such as the satellite availability, Position Dilution of Precision (PDOP) and Root Mean Square (RMS) error in congested city center areas. For this assessment, all four global constellations, i.e., GPS, BeiDou (BDS-3), Galileo and GLONASS, are utilized for the first time without using any augmentation or mitigation services.

Although there exist several studies evaluating the on-road performance of GNSS and a detailed comparison of these on-road analyses can be found in Section III of [24]. However, a majority of previous studies have been conducted on dual or triple constellations with GNSS correction services (i.e., Networked RTK, Proprietary) enabled. In order to highlight the pros and cons of using an increased number of constellations for positioning estimation, the next section covers the details of the field experiments performed, route dynamics, observation periods and signal-reception characteristics.

2.1. Experimental Sites/Route for Performance Evaluation

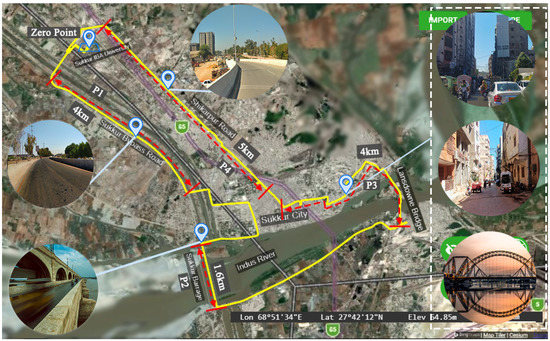

The route used for dynamic performance evaluation is a 30 km long route that covers the center and surroundings of Sukkur city in Pakistan i.e, including residential and industrial areas as well as highways. The route contains a wide range of operating environments, such as clear open-sky at the N-65 highway, semi-urban and dense urban areas with small lane widths, high-rise buildings, flyovers and bridges and thus is a more realistic test-run for urban canyons. For detailed performance assessment, the experimental route is divided into four distinct observation windows labeled as P1, P2, P3 and P4 as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A 30 km long route covering the Sukkur city center and its surroundings used for field experimentation contain various operating environments, such as clear open-sky at the N-65 highway, semi-urban and dense urban areas with small lane widths, high-rise buildings, flyovers and bridges. The total route is divided into four distinct observation windows based on environment characteristics, and these are labeled as P1, P2, P3 and P4.

The observation windows are selected based on the type of environment and obstacles on the vehicle route. The first observation window, P1, in Figure 1 is 4 km long, which is an N-65 highway connecting Sukkur to other cities. The P1 is a two-lane one-way route with mostly clear open-sky views resulting in excellent radio signal reception. The second observation window, P2, is a 1.6 km long bridge on the river Indus known as Lloyd’s Barrage. At P2, there are good chances of signal degradation (reflection or blockage) because of the structure of the bridge as shown in Figure 1.

Then, a 4 km long route at the center of Sukkur city is taken as the third observation window (P3). P3 is a densely populated area with high-rise buildings, congested roads, flyovers and two cantilever bridges (Lansdowne Bridge) each 310 feet long, where there are significant chances of blockage and signal quality degradation due to high multipath/NLOS reception. Finally, a 5 km long route with little or no obstruction is taken as the last observation site and labeled as P4.

This site has similar characteristics compared with those of P1. The route length, observation time and signal-reception characteristics of each of the observation windows are given in Table 1. Furthermore, the details of the field experimentation, which include the equipment used, number of constellation utilized, total time duration of each study and the antenna height, are given in Table 2.

Table 1.

The route length, observation time and signal-reception characteristics of the observation windows P1, P2, P3 and P4.

Table 2.

Equipment, duration, constellations and the antenna height for the two experiments.

2.2. Experimental Setup and Data Collection

The experimental setup and test vehicle used for the performance evaluation are shown in Figure 2. The high-precision antenna (PolaNt Choke Ring B3/E6) was mounted on the roof of the vehicle and connected to a PolaRx5S multi-frequency, multi-constellation GNSS receiver. The PolaRx5S can acquire and track signals from all four constellations, i.e., GPS, BeiDou, Galileo and GLONASS. The field experiment was performed by driving the vehicle along the route shown in Figure 1. The vehicle started and ended its journey at the Sukkur IBA University with a total observation period of 80 min. The GNSS data was logged at a rate of 1 Hz. The technical specifications of the equipment, i.e., the receiver, antenna and supported frequency bands, are given in Table 3.

Figure 2.

Instrumented test vehicle containing a roof-mounted antenna along with a PolaRx5s multi-frequency and multi-constellation GNSS receiver as used for field experimentation and data acquisition.

Table 3.

Technical specifications of the equipment used.

3. Performance Evaluation

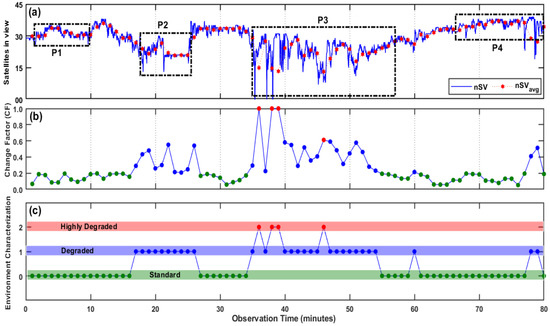

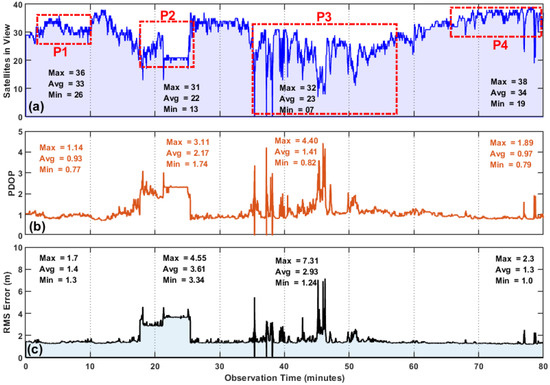

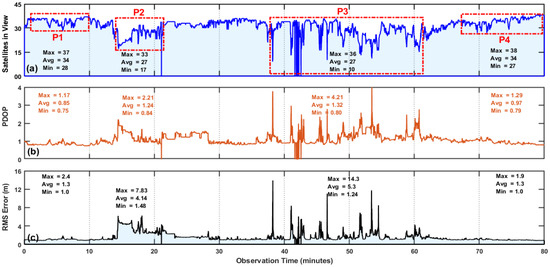

The performance evaluation results of a GNSS receiver in quad-constellation mode in terms of fundamental quality indicators, i.e., the satellite availability, PDOP and RMS error over the entire experimental route of Figure 1 with a complete observation period of 80 min are shown in Figure 3. Figure 3a shows the number of tracked satellites, Figure 3b represents the PDOP, whereas the RMS error is shown in Figure 3c. As already mentioned, the experimental route comprises a real-world driving profile consisting of a clear open-sky, semi-urban and dense urban areas with small lane widths, high-rise buildings, flyovers and bridges.

Figure 3.

The performance evaluation of a standard GNSS receiver in quad-constellation mode in terms of fundamental quality indicators, i.e., (a) the satellite availability, (b) PDOP and (c) RMS error over the entire experimental route containing different operating environments denoted by P1, P2, P3 and P4.

The results in Figure 3 show that significant deviations may occur in the fundamental quality indicators (PDOP, RMS error, satellites in-view and average satellite availability) when navigating across different types of operating contexts. In observation window P1, an average of 34 satellites were locked by the receiver during the 8 min time-slot, and this was expected due to negligible obstruction at the route.

The availability of a large number of satellites ensures more accurate and seamless navigation because redundant measurements can help in selecting satellites with strong signal strengths and thus constitute good satellite geometry. In fact, excellent PDOP values (average PDOP ) were observed during this observation window as shown in Figure 3b. The RMS error in P1 is depicted in Figure 3c.

As expected, with adequate satellites in view and good geometry, the average RMS error was found to be 1.3 m with lower and upper bounds of 1 and 2.4 m, respectively. The results suggest that lane-level accuracy (≤1.5 m) can be achieved at highways or suburban areas with standalone multi-constellation GNSS without any correction services.

As the test vehicle moved closer to the city center and passed through Lloyd’s Barrage (observation window P2), the quality parameters began to deteriorate rapidly due to the surroundings (i.e., the structure of the bridge) resulting in multipath/NLOS environments. The average number of tracked satellites reduced to 27 from 34 (Figure 3a), and the maximum PDOP value increased to 2.21 in Figure 3b. Although the satellite availability was adequate at this point (i.e., a minimum of 17 satellites were acquired), the positioning performance was degraded.

The average and maximum RMS errors in Figure 3c for the P2 observation window were found to be 4.14 and 7.83 m, respectively; however, this level of accuracy is not sufficient in many cases. The degraded positioning performance in P2 was due to the multipath and NLOS signal reception because there was no significant drop in the PDOP value, which was less than 2 most of the time as observed in Figure 3b. The PDOP values indicate the impact of the spatial distribution of the satellites on the final accuracy of the positioning solution, and a scale of 0 to 10 is typically used to compare the severity of this effect.

A PDOP value of less than 2 indicates excellent satellite geometry, a value between 2 and 4 is acceptable, and PDOP values of greater than 4 refer to a poor geometrical distribution of satellites. Based on the PDOP values, it can be concluded that multi-constellation GNSS enhances the probability of better satellite geometry and lower PDOP values; however, the effects of multipath and NLOS signal reception lead to increased RMS errors in the positioning solution as can be seen in Figure 3c in the P2 observation window. This shows that the PDOP alone is not a good indicator for evaluating the GNSS performance.

In Figure 3, the third observation window, i.e, P3, highlights the GNSS performance in the dense urban areas with congested roads, high-rise buildings, towers and a cantilever bridge. Among all the observation windows, P3 showed greater deterioration in the number of tracked satellites, PDOP values and the RMS error.

Since the vehicle was continuously navigating and the GNSS antenna was experiencing surroundings with different obstruction levels, on average, 27 satellites were being tracked by the receiver, and this varied between 10 and 36 based on the obstruction level and multipath/NLOS signal reception during the entire P3 window as can be seen in Figure 3a. The average PDOP value in P3 was found to be 1.24 with rapid variations between 0.80 and 4.21. In Figure 3c, the maximum and average RMS errors were 14.3 and 5.3 m, respectively, which are large and may be problematic for the receiver to correctly navigate in many applications.

The last case, i.e., the P4 observation window, exhibited similar characteristics to P1 in terms of locked satellites, DOP and RMS errors due to similar environmental dynamics. It should be noted that, in this study, GNSS was used in standalone mode without any correction services or augmentation system. The results of the field experiments for the observation windows P1, P2, P3 and P4 for different types of environments are given in Table 4, which gives a summarized overview of how the GNSS fundamental quality indicators can be affected while navigating through different environments encountering blockages, multipath environments and NLOS signal reception.

Table 4.

Comparison of quad-constellation GNSS receiver performance under different types of environments denoted by the P1, P2, P3 and P4 observation windows.

The performance evaluation results of a multi-constellation multi-frequency GNSS receiver in Figure 3 show that the urban canyon imposes greater challenges to positioning and navigation systems, and special measures need to be adopted to improve the GNSS availability and accuracy. The quality of the received signals and the statistical characteristics may vary in changing environmental contexts, and these variations can easily be observed in the received signal power, range measurements (i.e., the path delay and phase difference) and frequency because these factors are the major contributors to the correlation curve between the received signal and receiver-generated replica.

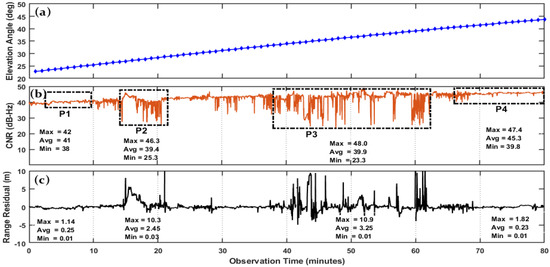

In this paper, the quality of the received signals is analyzed by the Carrier-to-Noise Ratio (CNR) and range residuals along with the elevation angle of satellites. The signal quality assessment tests performed for the aforementioned observation windows, i.e., P1, P2, P3 and P4, are shown in Figure 4. Figure 4a shows the elevation angles of satellites over the entire observation period of 80 min, Figure 4b represents the CNR, and Figure 4c shows the range residuals.

Figure 4.

The satellite signal quality assessment of GNSS set to quad-constellation mode in different types of environments denoted by P1, P2, P3 and P4 in Sukkur city. (a) Elevation angle, (b) Carrier-to-Noise Ratio (CNR) and (c) Range Residuals.

Typically, CNR is influenced by the elevation angle, and therefore PRN: 13 was selected here for quality assessment with increasing elevation angle trends during the observation periods. The signal characteristics in each observation window (i.e., P1, P2, P3 and P4) are highly correlated with the variations in fundamental quality indicators shown in Figure 3.

Both the GNSS fundamental quality indicators and quality of signal are equally influenced by the type of environment. In the P1 and P4 observation windows, the excellent signal strength (i.e., CNR) with great constancy and minimal range residuals corresponds with better GNSS performance, i.e., adequate satellite availability, better DOP values and smaller RMS error due to open-sky views.

Similarly, the signal quality in the P3 and P4 windows exhibited similar characteristics, i.e., significant variations in the signal strength, and higher values of range residuals were highly correlated with variations in the GNSS fundamental quality indicators as shown in Figure 3.

During the observation windows P1 and P4 in Figure 4b, the CNR values showed great constancy due to open-sky views with mostly direct LOS reception. The average CNR values during the P1 and P4 observation windows were found to be 41 and 45.3 dB, respectively. The range residuals for P1 and P4 were almost zero confirming the fact that the environmental context in which the receiver was operating in P1 and P4 was suitable for navigation. In the second observation window, i.e., P2, the signal quality degraded somewhat compared to P1 and P4.

The CNR values deviated between 25.3 and 46.3 dB. These variations show a significant correlation with the range residuals, as the average and maximum range residuals were found to be 2.45 and 10.3 m, respectively, in Figure 4c. On comparing the range residuals for the observation window P2 with those of P1 and P4, we concluded that these values of range residuals can lead to significant errors in the positioning solution.

Finally, the third observation window (i.e., P3) had the greatest effect on the quality of the received signals, which can be easily identified in Figure 4b,c in terms of the CNR and range residuals, respectively. Although the elevation angle for the P3 window is mostly above 30, there are rapid random fluctuations in the CNR with a minimum observed value of 23 dB and a maximum value of 48 dB leading to an average range residual of 3.25 m, which is significant when lane-level accuracy is required.

The field experimentation and performance evaluation of multi-constellation and multi-frequency GNSS indicates that, despite remarkable advancements in GNSS-based navigation technologies, standard GNSS services still cannot achieve the required navigation performance across all kinds of environmental contexts. In fact, it is evident from the performance evaluation results that the GNSS receiver experienced severe inaccuracies when navigating from open-sky views to dense urban areas.

Hence, the deployment of additional mechanisms to minimize the inaccuracies is inevitable in order to meet the required navigation performance in such environments. Although there has been substantial research into improving GNSS performance in urban environments by detecting, modeling, de-weighting and mitigating the NLOS/multipath effects at various levels, such as the antenna, receiver and measurement or position levels. These techniques work fairly well in certain environments but are of limited effectiveness in others as discussed in detail in Section 1.

Hence, after the performance evaluation of a GNSS receiver in the different environments above, we concluded that, in order to operate reliably and effectively in a wide range of environments, a GNSS receiver is required to adopt different mitigation techniques according to the detected environmental context. This requires the design and implementation of a model that is adaptive in nature, can accurately detect and identify working environments and can then adjust the mitigation strategy accordingly.

Keeping this in mind, in the next section, a new context-aware navigation (CAN) model is presented that works on an adaptive mitigation strategy based on the detected environment. The proposed method is validated through field experimentation in the subsequent sections.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

The GNSS signal characteristics provide advantages in identifying and characterizing the environmental context to improve the positioning accuracy. This paper reinforced the fact that multi-constellation GNSS performance varies greatly with the environmental context and is highly likely to deteriorate in dense urban environments surrounded by high-rise buildings, congested roads, flyovers and under-passes. A performance evaluation field study in these complex environmental scenarios revealed that a multi-constellation GNSS receiver, even after using four constellations, lacked consistency in maintaining the required accuracy thresholds across all kinds of environments.

The significant deviations in the number of tracked satellites, geometric distribution of satellites (PDOP) and quality of the navigation signal in the degraded and highly degraded environments due to signal obstructions and NLOS/multipath effects resulted in erroneous, inconsistent and unreliable positioning solutions. To increase the capability of a multi-constellation GNSS receiver, the context-aware navigation (CAN) method effectively utilized the multi-constellation GNSS receiver measurement parameters to first identify the type of working environment and then initiated a mitigation strategy accordingly for optimal receiver performance.

This was achieved by CAN through classifying the environment into three distinct categories: standard, degraded and highly degraded, based on two estimated features. After environment detection and characterization, CAN initiated the mitigation strategy by updating the CNR masking level in the case of a degraded environment or by changing the receiver tracking-loop parameters in the case of a highly degraded environment. The advantage of using CAN is its simplicity in terms of the implementation design, as it can be integrated in a GNSS receiver without great modifications.

The efficacy of CAN was validated in this paper through field experimentation on the same route and similar environment dynamics as used for a GNSS receiver without using CAN in a quad-constellation mode. The real-time implementation of CAN navigating through the different types of environmental contexts showed that this algorithm reduced the signal degradation effects in degraded and highly degraded environments by improving the lane level accuracy, which was achieved 53% of the time when using a CAN-based GNSS receiver and was achieved only 32% of the time when not using CAN.

In upcoming work, this study will be extended to larger context ranges, higher analysis windows, complex physical multipathways and concentrated quad-constellation conditions. Moreover, a more robust CAN algorithm using Deep-Markov inference will be designed to not only detect and classify an appropriate context but also to make autonomous variational decisions over the available set of GNSS signals. Furthermore, comparative analysis will be made between the offline and online compensation techniques for benchmark parameters, settings and configurations of the receiver under distinct dynamic environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H., A.A. and M.A.S.; methodology, A.H. and M.A.S.; software, A.H. and A.A.; validation, A.H., M.A.S. and S.K.; formal analysis, S.K.; investigation, A.H.; resources, M.A.S. and L.S.; data curation, A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H.; writing—review and editing, A.H., L.S. and H.M.; visualization, S.K., L.S. and H.M.; supervision, A.A.; project administration, M.A.S.; funding acquisition, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors wish to acknowledge the HEC (Higher Education Commission) of Pakistan for providing the financial support under National Research Program for Universities (NRPU) grant 6250/Sindh/NRPU/R&D/HEC/2016 for this research work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Skog, I.; Handel, P. In-car positioning and navigation technologies—A survey. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2009, 10, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, K.N.; Abdullah, A.H. A survey on intelligent transportation systems. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2013, 15, 629–642. [Google Scholar]

- Stallo, C.; Neri, A.; Salvatori, P.; Coluccia, A.; Capua, R.; Olivieri, G.; Gattuso, L.; Bonenberg, L.; Moore, T.; Rispoli, F. GNSS-based location determination system architecture for railway performance assessment in presence of local effects. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/ION Position, Location and Navigation Symposium (PLANS), IEEE, Monterey, CA, USA, 23–26 April 2018; pp. 374–381. [Google Scholar]

- El-Mowafy, A.; Kubo, N.; Kealy, A. Reliable positioning and journey planning for intelligent transport systems. In Intelligent and Efficient Transport Systems-Design, Modelling, Control and Simulation; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Hu, L.; Yang, G.; Zhao, C.; Fairbairn, D.; Watson, D.; Ge, M. Multi-GNSS precise point positioning for precision agriculture. Precis. Agric. 2018, 19, 895–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.F.G.; Fernandes, D.M.A.; Catarino, A.P.; Monteiro, J.L. Localization and positioning systems for emergency responders: A survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2017, 19, 2836–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, M.; Pirjanian, P.; Romanov, N.; Chiu, L.; Di Bernardo, E.; Stout, M.; Brisson, G. Application of Localization, Positioning and Navigation Systems for Robotic Enabled Mobile Products. U.S. Patent 8,452,450, 28 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, T.Q.; Becker, R.C.; Bauhahn, P.E. Portable Positioning and Navigation System. U.S. Patent 7,584,048, 1 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- GSA. GNSS User Technology Report; European GNSS Agency: Holesovice, Czech Republic, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Luccio, M. Using contact tracing and GPS to fight spread of COVID-19. GSP Word, 3 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Suryaatmadja, S.; Maulani, N. Contributions of Space Technology To Global Health in the Context of COVID-19. J. Adm. Kesehat. Indones. 2020, 8, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.B.; Hung, R.W.; Hsu, C.Y.; Chen, J.S. A GNSS-Based Crowd-Sensing Strategy for Specific Geographical Areas. Sensors 2020, 20, 4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, P.D. Principles of GNSS, inertial, and multisensor integrated navigation systems, [Book review]. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2015, 30, 26–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, N.; Nam, H.; Al-Naffouri, T.Y.; Alouini, M. A State-of-the-Art Survey on Multidimensional Scaling-Based Localization Techniques. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 3565–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardari, D.; Luise, M.; Falletti, E. Satellite and Terrestrial Radio Positioning Techniques: A Signal Processing Perspective; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi, V.; Napier, M. Modern navigation and positioning techniques. In Oceanology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 1986; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Petrovski, I.G. Standalone positioning with GNSS. In GPS, GLONASS, Galileo, and BeiDou for Mobile Devices: From Instant to Precise Positioning; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 88–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Pan, S.; Meng, X.; Gao, W.; Ye, F.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, X. Anomaly Detection for Urban Vehicle GNSS Observation with a Hybrid Machine Learning System. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, N.; Kobayashi, K.; Furukawa, R. GNSS Multipath Detection Using Continuous Time-Series C/N0. Sensors 2020, 20, 4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, H.F.; Zhang, G.; Luo, Y.; Hsu, L.T. Urban positioning: 3D mapping-aided GNSS using dual-frequency pseudorange measurements from smartphones. Navigation 2021, 68, 727–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidan, J.; Adegoke, E.I.; Kampert, E.; Birrell, S.A.; Ford, C.R.; Higgins, M.D. GNSS Vulnerabilities and Existing Solutions: A Review of the Literature. IEEE Access 2020, 9, 153960–153976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Diggelen, F.; Khider, M. Android Raw GNSS measurement datasets for precise positioning. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS+2020), St. Louis, MO, USA, 21–25 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, A.; Akhtar, F.; Khand, Z.H.; Rajput, A.; Shaukat, Z. Complexity and Limitations of GNSS Signal Reception in Highly Obstructed Enviroments. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2021, 11, 6864–6868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubert, N.; Reid, T.G.; Noble, F. Developments in Modern GNSS and Its Impact on Autonomous Vehicle Architectures. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.00339. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, A.; Ahmed, A.; Magsi, H.; Tiwari, R. Adaptive GNSS Receiver Design for Highly Dynamic Multipath Environments. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 172481–172497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, D. Real-world drive tests declare a verdict on GPS/GLONASS. ElectronicDesigns, 1 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Calini, G.G. The Results are In: Galileo Increases the Accuracy of Location Based Services. Available online: https://www.gsc-europa.eu/news/the-results-are-in-galileo-increases-the-accuracy-of-location-based-services-3 (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Heng, L.; Walter, T.; Enge, P.; Gao, G.X. GNSS multipath and jamming mitigation using high-mask-angle antennas and multiple constellations. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2014, 16, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirsiavash, A.; Broumandan, A.; Lachapelle, G.; O’Keefe, K. GNSS code multipath mitigation by cascading measurement monitoring techniques. Sensors 2018, 18, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Dovis, F.; Peng, S.; Morton, Y. Comparative Studies of GPS Multipath Mitigation Methods Performance. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2013, 49, 1555–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nee, R.D.J.; Siereveld, J.; Fenton, P.C.; Townsend, B.R. The multipath estimating delay lock loop: Approaching Theoretical accuracy limits. In Proceedings of the 1994 IEEE Position, Location and Navigation Symposium—PLANS’94, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 11–15 April 1994; pp. 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahmoudi, M.; Amin, M.G. Fast Iterative Maximum-Likelihood Algorithm (FIMLA) for multipath mitigation in next generation of GNSS receivers. In Proceedings of the 2006 Fortieth Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems and Computers, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 29 October–1 November 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Delgado, N.; Nunes, F.D. Multipath Estimation in Multicorrelator GNSS Receivers using the Maximum Likelihood Principle. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2012, 48, 3222–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardak, N.; Vervisch-Picois, A.; Samama, N. Multipath Insensitive Delay Lock Loop in GNSS Receivers. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2011, 47, 2590–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rougerie, S.; Carrié, G.; Vincent, F.; Ries, L.; Monnerat, M. A New Multipath Mitigation Method for GNSS Receivers Based on an Antenna Array. Int. J. Navig. Obs. 2012, 2012, 804732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, P.D.; Martin, H.; Voutsis, K.; Walter, D.; Wang, L. Context detection, categorization and connectivity for advanced adaptive integrated navigation. In Proceedings of the 26th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation, Nashville, TN, USA, 16–20 September 2013; The Institute of Navigation: Nashville, TN, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Groves, P.D. Context determination for adaptive navigation using multiple sensors on a smartphone. In Proceedings of the 29th International Technical Meeting of The Satellite Division of the Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS+ 2016), Portland, OR, USA, 12–16 September 2016; pp. 742–756. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, L.T.; Gu, Y.; Kamijo, S. Intelligent viaduct recognition and driving altitude determination using GPS data. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2017, 2, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokhandan, N.; Ziedan, N.; Broumandan, A.; Lachapelle, G. Context-aware adaptive multipath compensation based on channel pattern recognition for GNSS receivers. J. Navig. 2017, 70, 944–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Groves, P.D. Environmental context detection for adaptive navigation using GNSS measurements from a smartphone. Navig. J. Inst. Navig. 2018, 65, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, P.; Liu, Q.; Adeel, M.; Qian, J.; Jin, X.; Ying, R. Urban environment recognition based on the GNSS signal characteristics. Navigation 2019, 66, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Groves, P.D. Improving environment detection by behavior association for context-adaptive navigation. Navigation 2020, 67, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Pan, S.; Gao, W.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, Y. Real-time single-frequency GPS/BDS code multipath mitigation method based on C/N0 normalization. Measurement 2020, 164, 108075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNAVCO. UNAVCO Campaign GPS/GNSS Handbook; UNAVCO: Boulder, CO, USA, 2018; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Abdi, N.; Ardalan, A.A.; Karimi, R.; Rezvani, M.H. Performance assessment of multi-GNSS real-time PPP over Iran. Adv. Space Res. 2017, 59, 2870–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, D.; Dwivedi, R.; Dikshit, O.; Singh, A. GPS Furthermore, Glonass Combined Static Precise Point Positioning (PPP). Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote. Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2016, 41, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szot, T.; Specht, C.; Specht, M.; Dabrowski, P.S. Comparative analysis of positioning accuracy of Samsung Galaxy smartphones in stationary measurements. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrisano, A.; Dardanelli, G.; Innac, A.; Pisciotta, A.; Pipitone, C.; Gaglione, S. Performance Assessment of PPP Surveys with Open Source Software Using the GNSS GPS–GLONASS–Galileo Constellations. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldaner, L.F.; Canata, T.F.; Dias, C.T.d.S.; Molin, J.P. A statistical approach to static and dynamic tests for Global Navigation Satellite Systems receivers used in agricultural operations. Sci. Agric. 2021, 78, e20190252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, N.; Minetto, A.; Linty, N.; Dovis, F. A controlled-environment quality assessment of android GNSS raw measurements. Electronics 2019, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitelman, A.; Normark, P.L.; Reidevall, M.; Strickland, S. Apples to apples: A standardized testing methodology for high sensitivity gnss receivers. In Proceedings of the 20th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS 2007), Fort Worth, TX, USA, 25–28 September 2007; pp. 1370–1379. [Google Scholar]

- Cristodaro, C.; Ruotsalainen, L.; Dovis, F. Benefits and limitations of the record and replay approach for GNSS receiver performance assessment in harsh scenarios. Sensors 2018, 18, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyret, F.; Gilliéron, P.Y. SaPPART Guidelines, Performance Assessment of Positioning Terminal; Technical Report; IFSTTAR: Lyon, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Štern, A.; Kos, A. Positioning performance assessment of geodetic, automotive, and smartphone gnss receivers in standardized road scenarios. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 41410–41428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinana-Diaz, C.; Toledo-Moreo, R.; Bétaille, D.; Gomez-Skarmeta, A.F. GPS multipath detection and exclusion with elevation-enhanced maps. In Proceedings of the 2011 14th International IEEE Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Washington, DC, USA, 5–7 October 2011; pp. 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Groves, P.D.; Jiang, Z. Height aiding, C/N0 weighting and consistency checking for GNSS NLOS and multipath mitigation in urban areas. J. Navig. 2013, 66, 653–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.; Tokura, H.; Kubo, N.; Gu, Y.; Kamijo, S. Multiple Faulty GNSS Measurement Exclusion Based on Consistency Check in Urban Canyons. IEEE Sens. J. 2017, 17, 1909–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirsiavash, A.; Broumandan, A.; Lachapelle, G. Characterization of signal quality monitoring techniques for multipath detection in GNSS applications. Sensors 2017, 17, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T. Mobile robot localization with GNSS multipath detection using pseudorange residuals. Adv. Robot. 2019, 33, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolyakov, I.; Rezaee, M.; Langley, R.B. Resilient multipath prediction and detection architecture for low-cost navigation in challenging urban areas. Navig. J. Inst. Navig. 2020, 67, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).